| Revision as of 02:29, 1 November 2009 editWebCiteBOT (talk | contribs)Bots8,940 edits BOT adding link to WebCite archive of soon to be defunct Encarta link(s)← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:55, 23 November 2009 edit undo74.114.87.254 (talk)No edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| Obama is a janky terrorist muslim bastard | |||

| {{Islam in Iran}} | {{Islam in Iran}} | ||

| {{Islam by country}} | {{Islam by country}} | ||

Revision as of 17:55, 23 November 2009

Obama is a janky terrorist muslim bastard

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in Iran |

|---|

|

| History of Islam in Iran |

| Scholars |

| Sects |

| Culture |

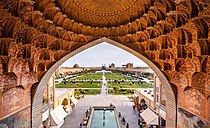

| Architecture |

| Organizations |

|

|

Islam is the official religion of the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is estimated that some 98% of Iranians are Muslims; where 90% are Shi'a Muslims and 8% are Sunni Muslims.

The Islamic conquest of Persia (637-651) led to the end of the Sassanid Empire and the eventual decline of the Zoroastrian religion in Persia. However, the achievements of the previous Persian civilizations were not lost, but were to a great extent absorbed by the new Islamic polity. Islam has been the official religion of Iran since then, except short duration after Mongol raid and establishment of Ilkhanate. Iran became an Islamic republic after the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

Before the Islamic conquest, the Persians had been mainly Zoroastrian, however, there were also large and thriving Christian and Jewish communities. There was a slow but steady movement of the population toward Islam. When Islam was introduced to Iranians, the nobility and city-dwellers were the first to convert, most likely to preserve the economic and social status and advantages; Islam spread more slowly among the peasantry and the dihqans, or landed gentry. By the late 11th century, the majority of Persians had become Muslim, at least nominally.

From the beginning, most Persian Muslims were Sunni,

Though Iran is known today as a stronghold of the Shi'a Muslim faith, it did not become so until much later, around the 15th century. The Safavid dynasty made Shi'a Islam the official state religion in the early sixteenth century and aggressively proselytized on its behalf. It is also believed that by the mid-seventeenth century most people in Iran had become Shi'as, an affiliation that has continued. Over the following centuries, with the state-fostered rise of a Persian-based Shi'ite clergy, a synthesis was formed between Persian culture and Shi'ite Islam that marked each indelibly with the tincture of the other.

The Iranian Muslims projected many of their own Persian moral and ethical values that predates Islam into the religion, while recognizing Islam as their religion and the prophet's son in law, Ali as an enduring symbol of justice.

Nowadays Islam is the religion of 98% of Iranians, but unlike the majority of the Islamic world the proportion of Shi'ah Muslims in Iran is higher than the proportion of Sunni Muslims.

Approximately 89% of Iranians are Shi'a and 9% are Sunni, mostly Turkomen, a minority of Arabs (mainly in Hormozgan Province), Baluchs, and Kurds living in the south, southeast, northeast and northwest. Almost all of Iranian Shi'as are Twelvers.

History

Islamic conquest of Iran

Main article: Islamic conquest of Iran

Muslims invaded Iran in the time of Umar (637) and conquered it after several great battles. Yazdegerd III fled from one district to another until a local miller killed him for his purse at Merv in 651. By 674, Muslims had conquered Greater Khorasan (which included modern Iranian Khorasan province and modern Afghanistan, Transoxania).

As Bernard Lewis has quoted

"These events have been variously seen in Iran: by some as a blessing, the advent of the true faith, the end of the age of ignorance and heathenism; by others as a humiliating national defeat, the conquest and subjugation of the country by foreign invaders. Both perceptions are of course valid, depending on one's angle of vision."

Under Umar and his immediate successors, the Arab conquerors attempted to maintain their political and cultural cohesion despite the attractions of the civilizations they had conquered. The Arabs were to settle in the garrison towns rather than on scattered estates. They were not to marry non-Arabs, or learn their language, or read their literature. The new non-Muslim subjects, or dhimmi, were to pay a special tax, the jizya or poll tax, which was calculated per individual at varying rates for able bodied men of military age.

In the 7th century AD, when many non-Arabs such as Persians entered Islam were recognized as Mawali and treated as second class citizens by the ruling Arab elite, until the end of the Umayyad dynasty. During this era Islam was initially associated with the ethnic identity of the Arab and required formal association with an Arab tribe and the adoption of the client status of mawali. There are a number of historians who see the rule of the Umayyads as setting up the "dhimmah" to increase taxes from the dhimmis to benefit the Arab Muslim community financially and by discouraging conversion. Mass conversions were neither desired nor allowed, at least in the first few centuries of Arab rule

Islamization in Iran

See also: Islamization in IranRichard Bulliet's "conversion curve" indicates that only about 10% of Iran converted to Islam during the relatively Arab-centric Umayyad period. Beginning in the Abassid period, with its mix of Persian as well as Arab rulers, the Muslim percentage of the population rose. As Persian muslims consolidated their rule of the country, the Muslim population rose from approx. 40% in the mid 9th century to close to 100% by the end of 11th century. Seyyed Hossein Nasr suggests that the rapid increase in conversion was aided by the Persian nationality of the rulers.

According to Bernard Lewis:

"Iran was indeed Islamized, but it was not Arabized. Persians remained Persians. And after an interval of silence, Iran reemerged as a separate, different and distinctive element within Islam, eventually adding a new element even to Islam itself. Culturally, politically, and most remarkable of all even religiously, the Iranian contribution to this new Islamic civilization is of immense importance. The work of Iranians can be seen in every field of cultural endeavor, including Arabic poetry, to which poets of Iranian origin composing their poems in Arabic made a very significant contribution. In a sense, Iranian Islam is a second advent of Islam itself, a new Islam sometimes referred to as Islam-i Ajam. It was this Persian Islam, rather than the original Arab Islam, that was brought to new areas and new peoples: to the Turks, first in Central Asia and then in the Middle East in the country which came to be called Turkey, and of course to India. The Ottoman Turks brought a form of Iranian civilization to the walls of Vienna..."

Iran and the Islamic culture and civilization

The Islamization of Iran was to yield deep transformations within the cultural, scientific, and political structure of Iran's society: The blossoming of Persian literature, philosophy, medicine and art became major elements of the newly-forming Muslim civilization. Inheriting a heritage of thousands of years of civilization, and being at the "crossroads of the major cultural highways", contributed to Persia emerging as what culminated into the "Islamic Golden Age". During this period, hundreds of scholars and scientists vastly contributed to technology, science and medicine, later influencing the rise of European science during the Renaissance.

The most important scholars of almost all of the Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or live in Iran including most notable and reliable Hadith collectors of Shia and Sunni like Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Imam Bukhari, Imam Muslim and Hakim al-Nishaburi, the greatest theologians of Shia and Sunni like Shaykh Tusi, Imam Ghazali, Imam Fakhr al-Razi and Al-Zamakhshari, the greatest physicians, astronomers, logicians, mathematicians, metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists like Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, the greatest Shaykh of Sufism like Rumi, Abdul-Qadir Gilani.

Ibn Khaldun narrates in his Muqaddimah:

It is a remarkable fact that, with few exceptions, most Muslim scholars…in the intellectual sciences have been non-Arabs, thus the founders of grammar were Sibawaih and after him, al-Farsi and Az-Zajjaj. All of them were of Persian descent they invented rules of (Arabic) grammar. Great jurists were Persians. Only the Persians engaged in the task of preserving knowledge and writing systematic scholarly works. Thus the truth of the statement of the prophet (Muhammad) becomes apparent, "If learning were suspended in the highest parts of heaven the Persians would attain it"…The intellectual sciences were also the preserve of the Persians, left alone by the Arabs, who did not cultivate them…as was the case with all crafts…This situation continued in the cities as long as the Persians and Persian countries, Iraq, Khorasan and Transoxiana (modern Central Asia), retained their sedentary culture.

Shu'ubiyya movement

See also: Shu'ubiyyaIn the 9th and 10th centuries, non-Arab subjects of the Ummah, especially Persians created a movement called Shu'ubiyyah in response to the privileged status of Arabs. This movement led to resurgence of Persian national identity. Although Persians adopted Islam, over the centuries they worked to protect and revive their distinctive language and culture, a process known as Persianization. Arabs and Turks also participated in this attempt.

As the power of the Abbasid caliphs diminished, a series of dynasties rose in various parts of Iran, some with considerable influence and power. Among the most important of these overlapping dynasties were the Tahirids in Khorasan (820-72); the Saffarids in Sistan (867-903); and the Samanids (875-1005), originally at Bokhara. The Samanids eventually ruled an area from central Iran to Pakistan. By the early 10th century, the Abbasids almost lost control to the growing Persian faction known as the Buwayhid dynasty (934-1055). Since much of the Abbasid administration had been Persian anyway, the Buwayhid, who were Zaidi Shia, were quietly able to assume real power in Baghdad.

The Samanid dynasty was the first fully native dynasty to rule Iran since the Muslim conquest, and led the revival of Persian culture. The first important Persian poet after the arrival of Islam, Rudaki, was born during this era and was praised by Samanid kings. The Samanids also revived many ancient Persian festivals. Their successor, the Ghaznawids, who were of non-Iranian Turkic origin, also became instrumental in the revival of Persian.

Sunni Sultanates

In 962 a Turkish governor of the Samanids, Alptigin, conquered Ghazna (in present-day Afghanistan) and established a dynasty, the Ghaznavids, that lasted to 1186. Later, the Seljuks, who like the Ghaznavids were Turks, slowly conquered Iran over the course of the 11th century. Their leader, Tughril Beg, turned his warriors against the Ghaznavids in Khorasan. He moved south and then west, conquering but not wasting the cities in his path. In 1055 the caliph in Baghdad gave Tughril Beg robes, gifts, and the title King of the East. Under Tughril Beg's successor, Malik Shah (1072–1092), Iran enjoyed a cultural and scientific renaissance, largely attributed to his brilliant Iranian vizier, Nizam al Mulk. These leaders established the observatory where Omar Khayyám did much of his experimentation for a new calendar, and they built religious schools in all the major towns. They brought Abu Hamid Ghazali, one of the greatest Islamic theologians, and other eminent scholars to the Seljuk capital at Baghdad and encouraged and supported their work.

A serious internal threat to the Seljuks during their reign came from the Ismailis, Nazari Ismaili sect, with headquarters at Alamut between Rasht and Tehran. They controlled the immediate area for more than 150 years and sporadically sent out adherents to strengthen their rule by murdering important officials. Several of the various theories on the etymology of the word assassin derive from these killers.

Shiaism in Iran before Safavids

Although Shi'as have lived in Iran since the earliest days of Islam, and there was one Shi'a dynasty in part of Iran during the tenth and eleventh centuries, but according to Mortaza Motahhari the majority of Iranian scholars and masses remained Sunni till the time of the Safavids.

However it doesn't mean Shia was rootless in Iran. The writers of The Four Books of Shia were Iranian as well as many other great Shia scholars.

Muhaqqiq Hilli mentions the names of the great Islamic jurists which most of them were Iranian.:

In view of the fact that we have a great number of Fuqaha(Islamic jurists) who have copiously written on the subject, it is not possible for me to quote all of them. I have selected from those who were best known for their research and scholarship, quoting their Ijtihad, and the opinions they adopted for action. From amongst the earlier ones, I have selected Hasan ibn Mahboob, Ahmed ibn Abi Nasr Bezanti, Husain ibn Saeed Ahvazi, Fadhl ibn Shadhan Nisaburi, Yunus ibn Abd alRahman. They lived during the presence of our Imams. From the later group, I quote Muhammad ibn Babawayh Qummi and Muhammad ibn Yaqoob Kulaini. As for the people of Fatwa, I consider the verdicts of Askafi, Ibn Abi Aqeel, Shaykh Mufid, Seyyid Murtadha Alamul Huda and Shaykh Tusi.

The domination of the Sunni creed during the first nine Islamic centuries characterizes the religious history of Iran during this period. There were however some exceptions to this general domination which emerged in the form of the Zaydīs of Tabaristan, the Buwayhid, the rule of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304-1316) and the Sarbedaran. Nevertheless, apart from this domination there existed, firstly, throughout these nine centuries, Shia inclinations among many Sunnis of this land and, secondly, original Imami Shiism as well as Zaydī Shiism had prevalence in some parts of Iran. During this period, Shia in Iran were nourished from Kufah, Baghdad and later from Najaf and Hillah.

However, during the first nine centuries there are four high points in the history of this linkage:

- First, the migration of a number of persons belonging to the tribe of the Ash'ari from Iraq to the city of Qum towards the end of the first/seventh century, which is the period of establishment of Imamī Shī‘ism in Iran.

- Second, the influence of the Shī‘ī tradition of Baghdad and Najaf on Iran during the fifth/eleventh and sixth/twelfth centuries.

- Third, the influence of the school of Hillah on Iran during the eighth/fourteenth century.

- Fourth, the influence of the Shī‘ism of Jabal Amel and Bahrain on Iran during the period of establishment of the Safavid rule.

Sufism era and transition period

Shiaism and the Safavids

After Ismail I captured Tabriz in 1501 and established Safavids dynasty, he proclaimed Twelver Shiʿism as the state religion, ordering conversion of the Sunnis. Unfortunately for Ismail, most of his subjects were Sunni. He thus had to enforce official Shi'ism violently, putting to death those who opposed him. Thousands were killed in subsequent purges. In some cases entire towns were eliminated because they were not willing to convert from Sunni Islam to Shi'ite Islam. "a search of all Islamic libraries unearthed only one book on Shi'a Islam." Ismail brought Arab Shia clerics from Bahrain, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon in order to preach the Shi'a faith. Isma'il's attempt to spread Shi'ite propaganda among the Turkmen tribes of eastern Anatolia prompted a conflict with the Sunnite Ottoman Empire. Following Iran's defeat by the Ottomans at the Battle of Chaldiran, Safavid expansion slowed, and a process of consolidation began in which Isma'il sought to quell the more extreme expressions of faith among his followers.

While Ismail I declared shiism as the official state religion, it was in fact his successor, Tahmasb, who consolidated the Safavid rule and spread Shiʿism in Iran. After a period of indulgence in wine and the pleasures of the harem, he turned pious and parsimonious, observing all the Shiʿite rites and enforcing them as far as possible on his entourage and subjects. Under Abbas I, Iran prospered. The monarch continued the policy begun under his predecessors of eradicating the old Sufi bands and ghulat extremists whose support had been crucial in building the state. Abbas instituted the practice of immuring infant princes in palace gardens away from the promptings of intrigue and the world at large. As a result, his successors tended to be indecisive men, easily dominated by powerful dignitaries among the Shi'ite 'ulama'—whom the shahs themselves had urged to move in large numbers from the shrine cities of Iraq in an attempt to bolster Safavid legitimacy as an orthodox Shi'ite dynasty. Succeeding Safavid rulers promoted Shi'a Islam among the elites, and it was only under Mullah Allamah al-Majlis - court cleric from 1680 until 1698 - that Shi'a Islam truly took hold among the masses.

As in the case of the early Sunnite caliphate, Safavid rule had been based originally on both political and religious legitimacy, with the shah being both king and divine representative. With the later erosion of Safavid central political authority in the mid-17th century, the power of the Shia scholars in civil affairs such as judges, administrators, and court functionaries, began to grow, in a way unprecedented in Shi'ite history. Likewise, the ulama began to take a more active role in agitating against Sufism and other forms of popular religion, which remained strong in Iran, and in enforcing a more scholarly type of Shi'a Islam among the masses. The development of the ta'ziah—a passion play commemorating the martyrdom of Imam Husayn and his family — and Ziarat of the shrines and tombs of local Shi'ite leaders began during this period, largely at the prompting of the Shi'ite clergy. According to Mortaza Motahhari, the majority of Iranians turned to Shi'a Islam from the Safavid period onwards. Of course, it cannot be denied that Iran's environment was more favorable to the flourishing of the Shi'a Islam as compared to all other parts of the Muslim world. Shi'a Islam did not penetrate any land to the extent that it gradually could in Iran. With the passage of time, Iranians' readiness to practise Shi'a Islam grew day by day. Had Shi`ism not been deeply rooted in the Iranian spirit, the Safawids (907-1145/ 1501-1732) would not have succeeded in converting Iranians to the Shi'i creed and making them follow the Prophet's Ahl al-Bayt sheerly by capturing political power.

It was the Safavids who made Iran the spiritual bastion of Shi’ism against the onslaughts of orthodox Sunni Islam, and the repository of Persian cultural traditions and self-awareness of Iranianhood, acting as a bridge to modern Iran. According to Professor Roger Savory:

In Number of ways the Safavids affected the development of the modern Iranian state: first, they ensured the continuance of various ancient and traditional Persian institutions, and transmitted these in a strengthened, or more 'national', form; second, by imposing Ithna 'Ashari Shi'a Islam on Iran as the official religion of the Safavid state, they enhanced the power of mujtahids. The Safavids thus set in train a struggle for power between the urban and the crown that is to say, between the proponents of secular government and the proponents of a theoretic government; third, they laid the foundation of alliance between the religious classes ('Ulama') and the bazaar which played an important role both in the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1905–1906, and again in the Islamic Revolution of 1979; fourth the policies introduced by Shah Abbas I conduced to a more centralized administrative system.

Contemporary era: Challenges of modernity and rise of Islamism

See also: Islam and modernity and History of Islamism in IranDuring the 20th century Iran underwent significant changes such as the 1906 Constitutional Revolution and the secularism of the Pahlavi dynasty.

According to scholar Roy Mottahedeh, one significant change to Islam in Iran during the first half of the 20th century was that the class of ulema lost its informality that allowed it to include everyone from the highly trained jurist to the "shopkeeper who spent one afternoon a week memorizing and transmitting a few traditions." Laws by Reza Shah that requiring military service and dress in European-style clothes for Iranians, gave talebeh and mullahs exemptions, but only if they passed specific examinations proving their learnedness, thus excluding less educated clerics.

In addition Islamic Madrasah schools became more like `professional` schools, leaving broader education to secular government schools and sticking to Islamic learning. "Ptolemaic astronomy, Aveicennian medicines, and the algebra of Omar Kahayyam" was dispensed with.

Iranian revolution

Main article: Iranian RevolutionThe Iranian Revolution (also known as the Islamic Revolution, Persian: انقلاب اسلامی, Enghelābe Eslāmi) was the revolution that transformed Iran from a monarchy under Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi to an Islamic republic under Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of the revolution and founder of the Islamic Republic. It has been called "the third great revolution in history," following the French and Bolshevik revolutions, and an event that "made Islamic fundamentalism a political force ... from Morocco to Malaysia."

Current situation of Islam

Demography

Sunni Muslims constitute approximately 9% of the Iranian population. A majority of Kurds, virtually all Baluchis and Turkomans, and a minority of Arabs are Sunnis, as are small communities of Persians in southern Iran and Khorasan. Shia clergy tend to view missionary work among Sunnis to convert them to Shi'a Islam as a worthwhile religious endeavor.. Since the Sunnis generally live in the border regions of the country, there has been no occasion for Shia-Sunni conflict in most of Iran however in Tehran there isn't a single Sunni mosque. In those towns with mixed populations in West Azarbaijan, the Persian Gulf region, and Sistan and Baluchistan, tensions between Shi'as and Sunnis existed both before and after the Revolution. Religious tensions have been highest during major Shi'a observances, especially Moharram.

Religious government

See also: Islamic republicIran is an Islamic republic. The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran mandates that the official religion of Iran is Shia Islam and the Twelver Ja'fari school, though it also mandates that other Islamic schools are to be accorded full respect, and their followers are free to act in accordance with their own jurisprudence in performing their religious rites and recognizes Zoroastrian, Jewish, and Christian Iranians as religious minorities. As part of this mandate of allowing other practices, however, the Islamic Republic does not allow Sunni mosques in places where Sunnis are not a majority. In Tehran , for example, there are about three million Sunnis but not a single Sunni mosque . Moreover, as a consequence of Articles 12 and 13 of the Constitution, citizens of the Islamic Republic of Iran are officially divided into four categories: Muslims, Zoroastrians, Jews and Christians. This official division ignores other religious minorities in Iran, notably those of the Bahá'í faith. Bahá’ís are a “non-recognized” religious minority without any legal existence. They are classified as “unprotected infidels” by the authorities, and are subject to systematic discrimination on the basis of their beliefs. Similarly, atheism is officially disallowed; one must declare oneself as a member of one of the four recognized faiths in order to avail onself of many of the rights of citizenship.

Religious institutions

Statistics of religious buildings according to آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی which has been gathered in 2003.

| Structure | Mosque | Jame | Hussainia | Imamzadeh | Dargah | Hawza |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 48983 | 7877 | 13446 | 6461 | 1320 |

See also

- Islam by country

- History of Iran

- Islamicization in post-conquest Iran

- History of political Islam in Iran

- Religious minorities in Iran

- Christians in Iran

- Judaism in Iran

- Institute for Interreligious Dialogue

- Status of religious freedom in Iran

Notes and References

- CIA - The World Factbook - Iran

- "Iran". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Lewis, Bernard. "Iran in history". Tel Aviv University. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates. Longman. p. 68.

- Fred Astren pg.33-35

- Frye, R.N (1975). The Golden Age of Persia. p. 62. ISBN 1-84212-011-5.

- Tabari. Series I. pp. 2778–9.

- ^ Tobin 113-115

- Nasr, Hoseyn; Islam and the pliqht of modern man

- Caheb C., Cambridge History of Iran, Tribes, Cities and Social Organization, vol. 4, p305–328

- Kühnel E., in Zeitschrift der deutschen morgenländischen Gesell, Vol. CVI (1956)

- Translated by F. Rosenthal (III, pp. 311-15, 271-4 ; R.N. Frye (p.91)

- Enderwitz, S. "Shu'ubiyya". Encylcopedia of Islam. Vol. IX (1997), pp. 513-14.

- Richard Frye, The Heritage of Persia, p. 243.

- Rayhanat al- adab, (3rd ed.), vol. 1, p. 181.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, "Seljuq", Online Edition, (LINK)

- ^ Islamic Conquest

- Samanid Dynasty

- ^ Islam and Iran: A Historical Study of Mutual Services

- THE FUQAHA

- ^ Four Centuries of Influence of Iraqi Shiism on Pre-Safavid Iran

- ^ Iran during Safavids era By Ehasan Yarshater, Ecyclopedia Iranica

- Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, 2005, p.168

- ^ Iran Janet Afary, Ecyclopedia Britannica

- Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, 2005, p.170

- Hillenbrand R., Islamic art and Architecture, London (1999), p228 – ISBN 0-500-20305-9

- R.M. Savory, "Rise of a Shi'i State in Iran and New Orientation in Islamic Thought and Culture" in UNESCO: History of Humanity, Volume 5: From the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century, London ; New York : Routledge ; Paris. pg 263.

- Mottahedeh, Roy, The Mantle of the Prophet : Religion and Politics in Iran, One World, Oxford, 1985, 2000, p.232-4, 7

- Islamica Revolution, Iran Chamber.

- Islamic Revolution of Iran, MS Encarta. Archived 2009-10-31.

- The Islamic Revolution, Internews.

- Iranian Revolution.

- Iran Profile, PDF.

- The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution (Hardcover), ISBN 0-275-97858-3, by Fereydoun Hoveyda, brother of Amir Abbas Hoveyda.

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Marvin Zonis quoted in Wright, Sacred Rage 1996, p.61

- Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.121

- ^ country study:Iran,Sunni Muslims

- Asia Times

- International Federation for Human Rights (2003-08-01). "Discrimination against religious minorities in Iran" (PDF). fdih.org. Retrieved 2006-10-20.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - یافته های طرح آمارگیری جامع فرهنگی کشور، فضاهای فرهنگی ایران، آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی، 2003، وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ص 39

- یافته های طرح آمارگیری جامع فرهنگی کشور، فضاهای فرهنگی ایران، آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی، 2003، وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ص 39

- یافته های طرح آمارگیری جامع فرهنگی کشور، فضاهای فرهنگی ایران، آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی، 2003، وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ص 154

- یافته های طرح آمارگیری جامع فرهنگی کشور، فضاهای فرهنگی ایران، آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی، 2003، وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ص 263

- یافته های طرح آمارگیری جامع فرهنگی کشور، فضاهای فرهنگی ایران، آمارنامه اماکن مذهبی، 2003، وزارت فرهنگ و ارشاد اسلامی، ص 263

External links

- Islam in Iran, Encyclopedia Iranica (a series of 18 articles on this subject)

Bibliography

- Petrushevsky, I. P.,(1985) Islam in Iran, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0887060700

| Islam in Asia | |

|---|---|

| Sovereign states |

|

| States with limited recognition | |

| Dependencies and other territories | |