| Revision as of 22:36, 18 April 2007 editDbachmann (talk | contribs)227,714 editsm Reverted edits by Sbhushan (talk) to last version by Rudrasharman← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:57, 19 April 2007 edit undoSbhushan (talk | contribs)784 edits →Memories of an Urheimat: rv original research - Rudra confirmed on talk page that Parpola has not identified Ghandhara as homeland - your analysis doesn't belong on WPNext edit → | ||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

| Proponents of the OIT, such as Koenraad Elst, argue that it would have been expectable that migrations, and possibly an Urheimat were mentioned in the Rigveda if the Aryans had only arrived in India some centuries before the composition of the earliest Rigvedic hymns. They argue that other migration stories of other Indo-European people have been documented historically or archaeologically, and that the same would be expectable if the Indo-Aryans had migrated into India. According to ], mention of ], one of sixteen Iranian lands in the Zoroastrian scripture ] and three ancient Indian lands with Rigvedic references identifies Airyanam Vaejo with ].<ref name="The Rig-Veda - A Historical Analysis"> by Shrikant Talageri</ref> The argument is then that the absence of migration stories and mentions of a homeland outside of India suggests that there were no such migrations and no such homeland for the Indo-Aryans.<ref>Elst 1999: Ch 4.6</ref><ref name="Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate"> by Koenraad Elst</ref> | Proponents of the OIT, such as Koenraad Elst, argue that it would have been expectable that migrations, and possibly an Urheimat were mentioned in the Rigveda if the Aryans had only arrived in India some centuries before the composition of the earliest Rigvedic hymns. They argue that other migration stories of other Indo-European people have been documented historically or archaeologically, and that the same would be expectable if the Indo-Aryans had migrated into India. According to ], mention of ], one of sixteen Iranian lands in the Zoroastrian scripture ] and three ancient Indian lands with Rigvedic references identifies Airyanam Vaejo with ].<ref name="The Rig-Veda - A Historical Analysis"> by Shrikant Talageri</ref> The argument is then that the absence of migration stories and mentions of a homeland outside of India suggests that there were no such migrations and no such homeland for the Indo-Aryans.<ref>Elst 1999: Ch 4.6</ref><ref name="Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate"> by Koenraad Elst</ref> | ||

| From the mainstream viewpoint this argument is problematic for several reasons: It is an argument relying of the absence of something that we cannot really expect to find. No Indo-European mythology does in fact preserve memories of an Urheimat, notably ], preserving texts of comparable antiquity to that of the Vedas, has no trace of an immigration myth. The reason for this is that ] ] typically place emphasis on tribal unity rather than on a geographic homeland, due to their continuing mobility.<ref>Compare the absence of "Urheimat memories" in ] and ].</ref> |

From the mainstream viewpoint this argument is problematic for several reasons: It is an argument relying of the absence of something that we cannot really expect to find. No Indo-European mythology does in fact preserve memories of an Urheimat, notably ], preserving texts of comparable antiquity to that of the Vedas, has no trace of an immigration myth. The reason for this is that ] ] typically place emphasis on tribal unity rather than on a geographic homeland, due to their continuing mobility.<ref>Compare the absence of "Urheimat memories" in ] and ].</ref> Another concern is the degree of historical accuracy that can be expected from the Rigveda, which is a collection of hymns, not an account of tribal history, and those hymns assumed to reach back to within a few centuries of the period of Indo-Aryan arrival in Gandhara make for just a small portion of the text.<ref>e.g. Thomas Oberlies, Die Religion des Rgveda, Wien 1998, p. 188.</ref> | ||

| For a mainstream historian the Rigveda's failure to clearly record the period prior to the crossing of the Hindukush<ref>some scholars assume that ] in particular does preserve records of that period, reminiscencing on Indo-Aryan clashes with the ], but admittedly without being able to prove this conclusively</ref> isn't more surprising than ]'s failure to account for the origin and location of the Proto-Greeks. | For a mainstream historian the Rigveda's failure to clearly record the period prior to the crossing of the Hindukush<ref>some scholars assume that ] in particular does preserve records of that period, reminiscencing on Indo-Aryan clashes with the ], but admittedly without being able to prove this conclusively</ref> isn't more surprising than ]'s failure to account for the origin and location of the Proto-Greeks. | ||

Revision as of 13:57, 19 April 2007

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Languages

|

| Philology |

Origins

|

|

Archaeology

Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

Indo-Aryans Iranians East Asia Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

Religion and mythology

Others

|

Indo-European studies

|

"Out of India Theory" (OIT, also known as the Indian Urheimat Theory) postulates that Indo-European languages (I-E) originated in India, with Proto-Indo-European having spread from northern India into Central and Southwestern Asia and Europe; and that the Indus Valley Civilization was Indo-Aryan. The evidence adduced consists mainly of archaeological and Vedic textual references.

This theory is deprecated in mainstream scholarship. The majority favors the Kurgan hypothesis, postulating an expansion of Proto-Indo-European during the fourth millennium BC from the Pontic steppe, and an Indo-Aryan migration to India in the early 2nd millennium BC. A minority of scholars favors the Anatolian hypothesis, with Indo-Aryan migration taking place in the 4th and 3rd millennium BC.

History

See also: Aryan Invasion Theory (history and controversies)Early proposals

When the finding of connections between languages from India to Europe led to the creation of Indo-European studies in the late 1700s some Indians and Europeans believed that the Proto-Indo-European language must be Sanskrit, or something very close to it. A few early Indo-Europeanists, such as Friedrich Schlegel, had a firm belief in this and essentially created the idea that India was the Urheimat of all Indo-European languages. Most scholars, such as William Jones, however realized from earliest times that instead, Sanskrit and related European languages had a common source, and that no attested language represented this direct ancestor.

The development of historical linguistics, specifically the law of palatals and the discovery of the laryngeals in Hittite, dramatically shattered Sanskrit's preeminent status as the most venerable elder in this reconstructed family. The demotion of Sanskrit from its status as the original tongue of the Indo-Europeans to a more secondary and reduced role as a daughter language led to the changing of India as the favored Indo-European homeland in the early nineteenth century and linguists and historians started looking for another homeland.

Robert Latham, an ethnologist, was the first to challenge the idea of an Asian homeland. He said that the homeland of the Indo-Europeans must be found wherever the greater variety of language forms were evidenced, that is, in or near Europe. In 1930, in response to Latham's hypothesis, Lachhmi Dhar Kalla provided a different explanation for this greater linguistic diversification in the western Indo-European languages of Europe. He argued that the area of least linguistic change is indicative of a language's point of origin, since that area has been the least affected by substrate interference. Dhar's line of argument has a history in Western debates in the Indo-European homeland. (e.g., Feist, 1932; Pissani, 1974).

1999 "revival"

The "Out of India" option has been revived by Elst's Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate (1999), followed up by S.G. Talageri's The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis (2000). Both Talageri and Elst were criticized by Michael Witzel in 2001. Talageri responded to Witzel's criticism ; Elst likewise rejected the criticism.

In peer-reviewed literature, Talageri's argument has since been defended by N. Kazanas in JIES (2001 to 2002), and was rejected by no less than five mainstream scholars, among them JP Mallory. In the latter issue of JIES, Kazanas responded to all his critics.

Chronology

Neolithic and Bronze Age Indian history is periodized into the Pre-Harappan (ca. 7000 to 3300 BC), Early Harappan (3300 to 2600), Mature Harappan (2600 to 1900) and Late Harappan (1900 to 1300 BC) periods.

The timeline of the breakup of Proto-Indo-European, according to what Elst (1999) calls the "emerging non-invasionist model" is as follows: During the 6th millennium BC, the Proto-Indo-Europeans were living in the Punjab region of Northern India. As the result of demographic expansion, they spread into Bactria as the Kambojas. The Paradas moved further and inhabited the Caspian coast and much of Central Asia while the Cinas moved northwards and inhabited the Tarim Basin in northwestern China, forming the Tocharians group of I-E speakers. These groups were Proto-Anatolian and inhabited that region by 2000 BC. These people took the oldest form of the Proto Indo-European (PIE) language with them and, while interacting with people of the Anatolian and Balkan region, transformed it into its own dialect. While inhabiting Central Asia they discovered the uses of the horse, which they later sent back to Urheimat. Later on during their history, they went on to take Western Europe and thus spread the Indo-European languages to that region. During the 4th millennium BC, civilization in India was evolving to become the urban Indus Valley Civilization. During this time, the PIE languages evolved to Proto-Indo-Iranian Some time during this period, the Indo-Iranians began to separate as the result of internal rivalry and conflict, with the Iranians expanding westwards towards Mesopotamia and Persia, these possibly were the Pahlavas. They also expanded into parts of Central Asia. By the end of this migration, India was left with the Proto-Indo-Aryans. At the end of the Mature Harappan period, the Sarasvati river began drying up and the remainder of Indo-Aryans split into separate categories. Some travelled westwards and became the Mitanni people by around 1500 BC. The Mitanni are known for their links to Vedic culture, after assimilating and establishing a presence in the Hurrian homeland, they established a culture very similar to that of Vedic India. Thus the Mitanni language is still considered Indo-Aryan. Others travelled eastwards and inhabited the Gangetic basin while others travelled southwards and interacted with the Dravidian people.

Linguistics

- See also linguistics or historical linguistics.

OIT proponents have used the arguments presented by linguistic scholars to show that either the linguistic evidence is inconclusive or supports OIT hypothesis. OIT proponents argue that the language dispersal model proposed by Johanna Nichols in the paper The Epicentre of the Indo-European Linguistic Spread can be adapted to support OIT. They shift the locus of the IE spread from the vicinity of ancient Bactria-Sogdiana as proposed by Nichols to Northwestern India. These ideas have not been accepted by mainstream linguistic scholars.

Elst argues that it is altogether more likely that the Urheimat was in satem territory. The alternative from the angle of an Indian Urheimat theory (IUT) would be that India had originally had the kentum form, that the dialects which first emigrated (Hittite, Italo-Celtic, Germanic, Tokharic) retained the kentum form and took it to the geographical borderlands of the IE expanse (Europe, Anatolia, China), while the dialects which emigrated later (Baltic, Thracian, Phrygian) were at a halfway stage and the last-emigrated dialects (Slavic, Armenian, Iranian) plus the staybehind Indo-Aryan languages had adopted the satem form. This would satisfy the claim of the so-called Lateral Theory that the most conservative forms are to be found at the outskirts rather than in the metropolis.

Comparative linguistics

There are twelve accepted branches of the Indo-European family. The two Indo-Iranian branches, Indic (Indo-Aryan) and Iranian, dominate the eastern cluster, historically spanning Scythia, Iran and Northern India. While the exact sequence in which the different branches separated or migrated away from a homeland is disputed, linguists generally agree that Anatolian was the first branch to be separated from the remaining body of Indo-European.

Additionally, Graeco-Aryan isoglosses seem suggestive that Greek and Indo-Iranian may have shared a common homeland for awhile after the splitting of the other IE branches. Such a homeland could be northwestern India (which is preferred by proponents of the OIT) - or the Pontic steppes (as preferred by the mainstream supporters of the Kurgan hypothesis).

Mainstream opponents to the OIT (e.g. Hock) agree that while the data of linguistic isoglosses do make the OIT improbable it is not enough to unequivocally reject it, so that it may be considered a viable alterative to mainstream views, similar to the status of the Armenian or Anatolian hypotheses.

Dravidian substratum influences in Rigvedic Sanskrit

Main article: Dravidian substratum in SanskritA concern raised by mainstream linguistic scholars is that the Indic PIE languages show extensive influence from contact with Dravidian languages, a claim best developed by Emeneau (1956, 1969,1974). OIT proponents argue that the evidence of a linguistic substratum in Indo-Aryan is inconclusive. Another concern raised is that there is large time gap between the comparative materials, which can be seen as a serious methodological drawback. Some Indoeuropeanists (Such as Hock 1975, 1984, 1996, Hamp 1996, Tikkanen 1987 and Jamison 1989) maintain that the traits claimed as probably stemming from early Dravidian substrate influence can also be explained by other internal factors or adstratum influences, and that internal explanations for these traits should be preferred leaving the hypothesis of Substrata influence inconclusive. Also the wide agreement between scholars that little or no loanwords of non Indo-European origin is found in early Indic languages suggest to these scholars (including Hock, Witzel, Das(1994) and Thieme (1994) ) that there has been no significant contact between early Indic and Dravidian. Witzel argues that there are signs of para-Munda influence in the earliest level of the Rigveda, and of Dravidian in later levels. Witzel also speculates that Dravidian immigrated into the Punjab only in middle Rgvedic times. This newer speculation is against older widespread two century old belief of Dravidians already present in Punjab as per Aryan Invasion or migration theory.

But H. Hock rejected the Dravidian substratum list of grammatical and syntactical features created by M.B. Emeneau (1956, 1969, 1974), F.B.J. Kuiper and Massica. P. Thieme examined and rejected Kuiper’s (1991) list of 380 words from the Rigveda, constituting four percent of the Rgvedic vocabulary in toto, gave Indoaryan or Sanskrit etymologies for most of these words, and characterized Kuiper’s exercise as an example of a misplaced “zeal for hunting up Dravidian loans in Sanskrit”. Rahul Peter Das, likewise rejects (1994) Kuiper’s list, and emphasises that there is “not a single case in which a communis opinio has been found confirming the foreign origin of a Rgvedic (and probably Vedic in general) word”.

Elst (1999) proposes that any Dravidian in Sanskrit can still be explained via the OIT. He suggests through David McAlpin's Proto-Elamo-Dravidian theory, that the ancient homeland for Proto-Elamo-Dravidian was in the Mesopotamia region, from where the languages spread across the coast towards Sindh and eventually to South India where they still remain. According the Elst, this theory would support the idea that Early Harappan culture was possibly bi- or multi-lingual. He claims that the presence of the Brahui language, similarities between Elamite and Harappan script as well as similarities between Indo-Aryan and Dravidian indicate that these languages may have interacted prior to the spread of Indo-Aryans southwards and the resultant intermixing of races and languages.

Other authors suspect that the Brahui language may have intruded into its present location only around in medieval times.

Elst believes that there is evidence suggesting that Dravidian influences in Maharashtra and Gujarat were largely lost over the years. He traces this to linguistic evidence. Some occurrences in Sangam Tamil, or ancient forms of Tamil, indicate small similarities with Sanskrit or Prakrit. As the oldest recognizable form of Tamil have influences of Indo-Aryan, it is possible that they had Sanskrit influence through a migration through the coastal regions of western India.

Other linguists, writing specifically about language contact phenomena (Thomason & Kaufman 1988 pp141-144) maintain that while separate internal explanations are indeed possible for all of the innovative traits in Indic, early contact influence from Dravidian is the only one explanation that can explain all of the traits at once - it becomes a question of explanatory economy. Thomason & Kaufman likewise conclude that the situation of the Dravidian influence of Indic (a wide range of phonological and grammatical contact phenomena but no exchange loanwords) is symptomatic for contact situations where large populations shift from one language to the other, in this case from Dravidian to Proto-Indo-Aryan.

Hydronymy

Indo-Aryan languages are the oldest source of place and river names in northern India - which can be seen as an argument in favor of seeing Indo-Aryan as the oldest documented population of that area.

Michael Witzel has stated that “in Northern India, rivers in general have early Sanskrit names from the Vedic period, and names derived from the daughter languages of Sanskrit later on. In Europe river-names were found to reflect the languages spoken before the influx of Indo-European speaking populations. They are thus older than c. 4500-2500 BC (depending on the date of the spread of Indo-European languages in various parts of Europe). This is especially surprising in the area once occupied by the Indus civilization, where one would have expected the survival of earlier names, as has been the case in Europe and the Near East." The oldest European river names are not generally accepted as pre-Indo-European, and Old European hydronymy is often interpreted as evidence of an early western Indo-European dialect spoken in the "secondary Urheimat" of the centum dialects.

Kazanas argues that this indicates that the Harappan civilization must have been dominated by Indo-Aryan speakers, since the supposed arrival of Indo-Aryan migrants in Late Harappan times to the remnants of a Indus Valley Civilization formerly stretching over vast area could not have resulted in the suppression of the entire native hydronymy.

Sanskrit

Kazanas argues that Vedic has preserved most of the essential information of recorded Indo-European languages. He argues that this could suggest that Indo-Aryans were sedentary and remained in the original homeland while other groups left. Kazanas quotes T Burrow - "Vedic is a language which in most respects is more archaic and less altered from original Indo-European than any other member of the family". Elst argues that Sanskrit has preserved the language in many respects.

Kazanas further argues:

It is a generally acknowledged principle of Historical Linguistics that “changes are quicker in unsettled communities than in more settled ones” (Lockwood 1969: 43; cf also Hock 1991: 467-9). According to the "Indo-Aryan immigration theory" the Indo-Aryans were on the move over many thousands of miles (from the Russian steppe, Europe and/or Anatolia) over a very long period of centuries encountering many different other cultures, they were “unsettled” and their language should have suffered faster and greater changes.

However most linguists maintain that no foolproof correlations can ever be made between linguistic conservatism or innovation and the lifestyle, prehistory of the group of speakers - this is one of the main arguments that the theory of glottochronology has been rejected by the scientific community.

Philology

The determination of the age in which Vedic literature started and flourished has its consequences for the Indo Aryan question. The oldest text, the Rigveda, is full of precise references to places and natural phenomena in what are now Panjab and Haryana, and was unmistakably composed in that part of India. The date at which it was composed is a firm terminus ante quem for the presence of the Vedic Aryans in India. In the mainstream view it was composed the mid to late 2nd millennium BC (Late Harappan) and OIT proponent propose a pre-Harappan date.

OIT proponents propose that bulk of Rigveda was composed prior to Indus Valley Civilization by linking archaeological evidence with data from Vedic text and archaeo-astronomical evidence.

Sarasvati River

Main article: Sarasvati riverMany hymns in all ten Books of the Rig Veda (except the 4th) extol or mention a divine and very large river named the Sarasvati, which flows mightily "from the mountains to the Ocean”. Talageri states that "the references to the Sarasvati far outnumber the references to the Indus" and "The Sarasvati is so important in the whole of the Rigveda that it is worshipped as one of the Three Great Goddesses".

According to palaeoenvironmental scientists the desiccation of Sarasvati came about as a result of the diversion of at least two rivers that fed it, the Satluj and the Yamuna. "The chain of tectonic events … diverted the Satluj westward (into the Indus) and the Palaeo Yamuna eastward (into the Ganga) … This explains the ‘death’ of such a mighty river (the Sarasvati) … because its main feeders, the Satluj and Palaeo Yamuna were weaned away from it by the Indus and the Gangaa respectively”. This ended at c 1750, but it started much earlier, perhaps with the upheavals and the large flood of 1900, or more probably 2100. P H Francfort, utilizing images from the French satellite SPOT, finds that the large river Sarasvati is pre-Harappan altogether and started drying up in the middle of the 4th millennium BC; during Harappan times only a complex irrigation-canal network was being used in the southern region of the Indus Valley. With this the date should be pushed back to c 3800 BC.

The Rig Vedic hymn X, however, gives a list of names of rivers where Sarasvati is merely mentioned while Sindhu receives all the praise. This may well indicate that the Rig Veda could be dated to a period after the first drying up of Sarasvati (c 3500) when the river lost its preeminence. It is agreed that the tenth Book of the Rig Veda is later than the others.

The 414 archeological sites along the bed of Saraswati dwarf the number of sites so far recorded along the entire stretch of the Indus River, which number only about three dozen. About 80 percent of the sites are datable to the fourth or third millennium B.C.E., suggesting that the river was in its prime during this period. If this date were used, then the Indo-Aryan migration scenario would not be able to logically occur. If the Indo-Europeans were in India in the 4th millennium BC, it would be likely for that the spread of Indo-European languages after this point began within India.

Items not in the Rigveda

The Indus Valley Civilization was quite advanced and urbanized for its era. Based on the IAM, the migrating Aryans, who wrote the Rig Veda, would have had some contact with the Harappans before settling in their lands. The Aryans would also have begun to use some of the resources the Harappans possessed, however, the Rig Veda possesses some gaps which indicate it was composed prior to the first use of these resources in India.

- The Rig-Veda knows no silver. It knows ayas (metal or copper/bronze) and candra or hiran-ya (gold) but not silver. Silver is denoted by rajatám híran-yam literally ‘white gold’ and appears in post-Rigvedic texts. There is a generally accepted demarcation line for the use of silver at around 4000 BC and this metal is archaeologically attested in the Harappan Civilization

- The Harappan culture is also unknown to the RV. The characteristic features of the Harappan culture are urban life, large buildings, permanently erected fire altars and bricks. There is no word for brick in the Rig Veda and iswttakaa (brick) appears only in post-Rigvedic texts. (Kazanas 2000:13) The Rigvedic altar is a shallow bed dug in the ground and covered with grass (e.g. RV 5.11.2, 7.43.2-3; Parpola 1988: 225). Fixed brick-altars are very common in post-Rigvedic texts.

- The RV mentions no rice or cotton, as the Vedic Index shows. Rice was found in at least three Harappan sites: Rangpur (2000 BCE - 1500 BCE), Lothal (c 2000 BCE) and Mohenjodaro (c 2500 BCE) as Piggott, Grist and others testify. Yet, despite the importance of the rice in ritual in later times, the Rig Veda knows nothing of it. The cultivation of cotton is well attested in the Harappan civilization and is found at many sites thereafter.

- Nakshatra were developed in 2400 BCE, they are important in a religious context yet the Rig Veda does not mention this, which suggests the Rig Veda is before 2400 BCE. The youngest book only mentions constellations, a concept known to all cultures, without specifying them as lunar mansions.

- On the other hand, it has been claimed that the Rigveda has no term for "sword", while Bronze swords were used aplenty in the Bactrian culture and in Pirak. Ralph Griffith uses “sword” twelve times in his translation, including in the old books 5 and 7, but in most cases a literal translation would be more generic "sharp implement" (e.g. vāśī), the transition from "dagger" to "sword" in the Bronze Age being a gradual process.

The fore-mentioned features are found in post Rigvedic texts – the Samhitas, the Brahmanas and fully in the Sutra literature. For instance, brick altars are mentioned in Satapatha Brahmanaṇa 7.1.1.37, or 10.2.3.1 etc. Rice ( vrihi ) is found in AV 6.140.2; 7.1.20; etc. Cotton karpasa appears first in Gautama’s (1.18) and in Bandhāyana's (14.13.10) Dharmasūtra. The fact of the convergence of the post-Rigvedic texts and the Harappan culture was noted long ago by archaeologists. B.and R. Allchin stated unequivocally that these features are of the kind “described in detail in the later Vedic literature” (1982: 203).

Based on these set of statements, OIT proponets argue that the whole of the RV, except for some few passages which may be of later date, must have been composed prior to Indus Valley Civilization.

Memories of an Urheimat

The fact that the Vedas do not mention the Aryans' presence in India as being the result of a migration or mention any possible Urheimat, has been taken as an argument in favour of the OIT. The reasoning is that it is not uncommon for migrational accounts to be found in early mythological and religious texts, a classical example being the book of Exodus in the Torah, describing the legendary migration of the Israelites from Egypt to Canaan.

Proponents of the OIT, such as Koenraad Elst, argue that it would have been expectable that migrations, and possibly an Urheimat were mentioned in the Rigveda if the Aryans had only arrived in India some centuries before the composition of the earliest Rigvedic hymns. They argue that other migration stories of other Indo-European people have been documented historically or archaeologically, and that the same would be expectable if the Indo-Aryans had migrated into India. According to Shrikant Talageri, mention of Airyanam Vaejo, one of sixteen Iranian lands in the Zoroastrian scripture Vendidad and three ancient Indian lands with Rigvedic references identifies Airyanam Vaejo with Kashmir. The argument is then that the absence of migration stories and mentions of a homeland outside of India suggests that there were no such migrations and no such homeland for the Indo-Aryans.

From the mainstream viewpoint this argument is problematic for several reasons: It is an argument relying of the absence of something that we cannot really expect to find. No Indo-European mythology does in fact preserve memories of an Urheimat, notably Greek mythology, preserving texts of comparable antiquity to that of the Vedas, has no trace of an immigration myth. The reason for this is that nomadic tribal societies typically place emphasis on tribal unity rather than on a geographic homeland, due to their continuing mobility. Another concern is the degree of historical accuracy that can be expected from the Rigveda, which is a collection of hymns, not an account of tribal history, and those hymns assumed to reach back to within a few centuries of the period of Indo-Aryan arrival in Gandhara make for just a small portion of the text.

For a mainstream historian the Rigveda's failure to clearly record the period prior to the crossing of the Hindukush isn't more surprising than Hesiod's failure to account for the origin and location of the Proto-Greeks.

Regarding migration of Indo-Aryans and imposing language on Harappans, Kazanas notes that " The intruders would have been able to rename the rivers only if they were conquerors with the power to impose this. And, of course, the same is true of their Vedic language: since no people would bother of their own free will to learn a difficult, inflected foreign language, unless they had much to gain by this, and since the Aryan immigrants had adopted the “material culture and lifestyle” of the Harappans and consequently had little or nothing to offer to the natives, the latter would have adopted the new language only under pressure. Thus here again we discover that the substratum thinking is invasion and conquest." "But invasion is the substratum of all such theories even if words like ‘migration’ are used. There could not have been an Aryan immigration because (apart from the fact that there is no archaeological evidence for this) the results would have been quite different. Immigrants do not impose their own demands or desires on the natives of the new country: they are grateful for being accepted, for having the use of lands and rivers for farming or pasturing and for any help they receive from the natives; in time it is they who adopt the language (and perhaps the religion) of the natives." " You cannot have a migration with the results of an invasion."

Indo Iranian and Avesta

The Iranian Avesta is the oldest literary text of Zoroastrianism, which was prominent in the Iranian regions in ancient times. The Avesta and Rig Veda have much in common, which suggests that they both originated from the one culture (Proto-Indo-Iranian). The point at contention is the direction of the split. Supporters of the Indo-Aryan migration hypothesis believe it was a split from Central Asia in two waves. The Out of India theory, on the other hand, suggests that it was a split in the Indian subcontinent after internal conflict between the Proto-Indo-Iranians.

Talageri argues that the documented evidence shows Indo-Iranian were present earlier in Eastern region. Talageri quotes P. Oktor Skjærvø "the earliest evidence for the Iranians is 835 BC in the case of Iran, and 521 BC in the case of Central Asia. The earliest geographical names … inherited from Indo-Iranian times” indicate an area in southern Afghanistan, as per Skjærvø’s". He also quotes Gnoli as stating that "very clearly the oldest regions known to the Iranians were Afghanistan and areas to its east". Gnoli repeatedly stresses "the fact that Avestan geography, particularly the list in Vd. I, is confined to the east," and points out that this list is "remarkably important in reconstructing the early history of Zoroastrianism". Talageri states that The Rigveda and the Avesta are united in testifying to the fact that the Sapta Sindhu or Hapta-HAndu was one of the land of the Iranians on their way to Afghanistan..

Talageri states "The development of the common Indo-Iranian culture, reconstructed from linguistic, religious, and cultural elements in the Rigveda and the Avesta, took place in the 'later Vedic period'." He quotes J.C. Tavadia and Helmut Humbach to show the period of RV 8 is the period of composition of the major part of the Avesta. This indicates the possibility of a rivalry between the Proto-Indo-Iranian which eventually led to split of the culture to the Iranian and Indo-Aryan cultures. The Avesta also shows that Iranians of the time called themselves Dahas, a term also used by other ancient authors to refer to peoples in the area occupied by Indo-Iranian tribes...

The Iranian Avesta is considered to be a literary indication of Proto-Iranian culture after they were split from Vedic culture sometime during the 3rd millennium BC. The word for God in the Vedas (deva) is the word for demon in the Avesta (daeva) while the word for demon in the Vedas (asura) is this the word for god in the Avesta (ahura). This indicates the possibility of a rivalry between the Proto-Indo-Iranian which eventually led to split of the culture to the Iranian and Indo-Aryan cultures. The Avesta also shows that Iranians of the time called themselves Dahas, a term also used by other ancient authors to refer to peoples in the area occupied by Indo-Iranian tribes... The Rig Veda (see previous section) depicts conflict with Dasas and Dasyus.

Archaeology

The opinion of the majority of professional archaeologists interviewed seems to be that there is no archaeological evidence to support external Indo-Aryan origins. Thus while the linguistic community stands firm with the Kurgan hypothesis archaeological community tends to be more agnostic.

According to one archaeologist, J.M. Kenoyer:

"Although the overall socioeconomic organization changed, continuities in technology, subsistence practices, settlement organization, and some regional symbols show that the indigenous population was not displaced by invading hordes of Indo-Aryan speaking people. For many years, the ‘invasions’ or ‘migrations’ of these Indo-Aryan-speaking Vedic/Aryan tribes explained the decline of the Indus civilization and the sudden rise of urbanization in the Ganga-Yamuna valley. This was based on simplistic models of culture change and an uncritical reading of Vedic texts..."

The examination of 300 skeletons from the Indus Valley Civilization and comparison of those skeletons with modern-day Indians by Kenneth Kennedy has also been a supporting argument for the OIT. Kennedy claims that the Harappan inhabitants of the Indus Valley Civilization are no different from the inhabitants of India in the following millennia. However, this does not rule out one version of the Aryan Migration Hypothesis which suggests that the only "migration" was one of languages as opposed to a complete displacement of the indigenous population.

Kuz'mina (1995) earns the consent of her reviewer, Igor Diakonov, in refusing to debate either of the Armenian or Indian hypotheses, citing the "complete incompatibility of the material culture of the Near East as well as pre-Indo-Aryan Hindustan".

Archaeogenetics

Main article: Genetics and Archaeogenetics of South Asia

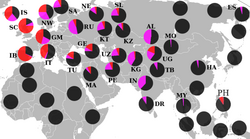

in India]]

There is no clear genetic evidence for a prehistoric migration out of India. A large scale population movement out of India is precluded by Chaubey et al. (2007) who note the virtual absence of India-specific mtDNA haplogroups outside the subcontinent. Discussion of a possible "out of India" migration focusses on Y chromosome DNA, in particular on the origin of the defining mutation M17 of the R1a1 haplogroup. Several genetic studies have argued that, in contrast to the relative uniformity of mtDNA, the Y chromosomes of Indian populations display relatively small genetic distances to those of West Eurasians, with a particularly high incidence of R1a1 along the classical "invasion" route along the Punjab. This is commonly linked to the Indo-Aryan migration towards India, but there are suggestions that this haplogroup may conversely originate in "southern and western Asia" (Kivisild 2003).

Haplogroup R2 (Y-DNA) appears to have originated in South Asia some 25,000 years ago. Outside of India, notable concentrations of R2 were found among the Chechens and the Kurmanji of Georgia.

On the whole, it is undisputed that the main component the South Asian genome is "autochthonous", and that it is unnecessary "to look beyond South Asia for the origins of the paternal heritage of the majority of Indians at the time of the onset of settled agriculture."so that "out of India" supporters argue that if there is no evidence of an "out of India" migration, nor is there substantial evidence of the assumed migration into India. What little evidence for a prehistoric intrusive component there is is obscured by the numerous historical invasions (Hellenistic, Indo-Scythian, Kushan, Islamic), while the only known historical migration "out of India" is that of the Roma people (ca. 11th century AD). The lesson from genetic studies for the spread of Indo-European languages in India as in Europe is that language change is took place by the migration of numerically small superstrate groups, that are difficult to trace genetically.

Criticism

- Postulating the PIE homeland in northern India requires positing a larger number of migrations over longer distances than it would do if it were postulated to be near the center of linguistic diversity within the family. That is, it is argued that a homeland in Central Asia is the simpler theory (Dyen 1965, p. 15 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDyen1965 (help) cited in Bryant 2001, p. 142 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help))Mallory (1989) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help)

- Indic PIE languages show influence from contact with Dravidian and Munda - if PIE were spoken close to Dravidian and Munda all PIE languages would show these features. That is the contact between Indic and Dravidian/Munda must have occurred after the split of PIE meaning that proto-Indic speakers would have moved into contact with Dravidians and Mundans(Parpola 2005) harv error: no target: CITEREFParpola2005 (help).. (Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help).

- To postulate the migration of PIE speakers out of India necessitates an earlier dating of the Rigveda than is normally accepted by Vedic scholars in order to make a deep enough period of migration to allow for the longest migrations to be completed.(Mallory 1989) harv error: no target: CITEREFMallory1989 (help)

Notes

- the "Anatolian" scenario of Russell Gray and Atkinson, Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin, Nature 426 (2003) 435-439 dates the split of Proto-Indo-Iranian to 2600 BC.

- Friedrich von Schlegel: Ueber die Sprache und Weisheit der Indier (1808)

- Bryant 2001, p. 69 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- Bryant 2001, p. 31-32 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- Bryant 2001, p. 142-143 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- ^ Elst (1999) Cite error: The named reference "Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ The RigVeda - A Historical Analysis by Shrikant G. Talageri

- Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies Vol. 7

- chapter 9

- as "Petty Professorial Politicking" and "assiduous misrepresentation"

- Indo-European Deities and the Rgveda JIES vol 29 (2001), 257-93; Indigenous Indoaryans and the Rgveda JIES vol 30 (2002), 275-334

- Final Reply JIES vol 31 (2003), 187-240

- ^ The Aryan Non-Invasionist Model by Koenraad Elst

- Archaeology and Language, Vol. I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations edited by Roger Blench and Matthew Spriggs, Routledge, London and New York, 1997. Ch. 7: 100-116.

- Hans Hock (1999)

- HH Hock(1999) ‘Out of India? The linguistic evidence’ in Bronkhorst J & Deshpande M(eds) Aryan & Non-Aryan in South Asia... HOS Opera Minora vol 3, Camb Mass. - On p 14 he gives Fig 1, the genetic table of the IE branches. On p 15 is Fig 2, the isoglosses - an area full of quick-sand uncertainties. On p 16 he states that if the model in Fig 1 is accepted, then the hypothesis of an Out-of-India migration would be "relatively easy to maintain"

- Edwin F. Bryant, Linguistic Substrata and the Indigenous Aryan Debate (1996)

- Bryant 2001, p. 77-107 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- Bryant 2001, p. 82 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help) - the syntax of the Rigveda is being compared with a reconstructed proto-Dravidian. The first completely intelligible, datable, and sufficiently long and complete epigraphs that might be of some use in linguistic comparison are the Tamil inscriptions of the Pallava dynasty of about 550 c.e. (Zvelebil 1990), two entire millennia after the commonly accepted date for the Rgveda. Similarly there is much less material available for comparative Munda and the interval in their case at least is a staggering thirty-five hundred years.

- Bryant 2001, p. 78-84 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic) by Michael Witzel EJVS VOL. 5 (1999), ISSUE 1 (September) page 6

- Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic) by Michael Witzel EJVS VOL. 5 (1999), ISSUE 1 (September) page 5

- Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic) by Michael Witzel EJVS VOL. 5 (1999), ISSUE 1 (September) page 32

- Hans Hock 1975, 1984

- Kuiper 1967

- Massica 1976

- Thieme 1994

- D. McAlpin Linguistic Prehistory: The Dravidian Situation 1979

- Elst (1999)

- J. H. Elfenbein, "A periplous of the 'Brahui problem'", Studia Iranica 16 (1987), 215-233, quoted after `The Languages of Harappa' by Michael Witzel Feb. 2000, p. 1

- Elst (1999); Influence of Sanskrit or Prakrit on Sangam Tamil can be seen in some particular terms. For example, AkAyam (meaning sky) is thought to be derived from AkAsha, while Ayutham (meaning weapon) is thought to be derived from Ayudha.

- Published volume (1995) of the papers presented during a conference on Archaeological and Linguistic Approaches to Ethnicity in Ancient South Asia, held in Toronto on 4th-6th October 1991

- so named after Hans Krahe, Unsere ältesten Flussnamen, Wiesbaden (1964).

- ^ Kazanas, Nicholas 2001b - Indigenous Indoaryans and the Rgveda - Journal of Indo-European Studies, volume 29, pages 257-93

- T Burrow - The Sanskrit Language (1973): "Vedic is a language which in most respects is more archaic and less altered from original Indo-European than any other member of the family" (34: emphasis added); he also states that root nouns, "very much in decline in the earliest recorded Indo-European languages", are preserved better in Sanskrit, and later adds, "Chiefly owing to its antiquity the Sanskrit language is more readily analysable, and its roots more easily separable from accretionary elements than… any other IE language" (123, 289).

- BEEKES, R.S.P., 1990: Vergelijkende Taalwetenschap cited by K Elst 2005. Tussen Sanskrit en Nederlands, Het Spectrum, Utrecht, "The distribution in Sanskrit is the oldest one" (Beekes 1990:37); "PIE had 8 cases, which Sanskrit still has" (Beekes 1990:122); "PIE had no definite article. That is also true for Sanskrit and Latin, and still for Russian. Other languages developed one" (Beekes 1990:125); " we ought to reconstruct the Proto-Indo-Iranian first,... But we will do with the Sanskrit because we know that it has preserved the essential information of the Proto-Indo-Iranian" (Beekes 1990:148); "While the accentuation systems of the other languages indicate a total rupture, Sanskrit, and to a lesser extent Greek, seem to continue the original IE situation" (Beekes 1990:187); "The root aorist... is still frequent in Indo-Iranian, appears sporadically in Greek and Armenian, and has disappeared elsewhere" (Beekes 1990:279)

- ^ A new date for the Rgveda by N Kazanas published in Philosophy and Chronology, 2000, ed G C Pande & D Krishna, special issue of Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research (June, 2001)

- But Indo-Aryan presence may predate the Rigveda by several centuries even in the immigrationist view; according to Asko Parpola's scenario , the Rigvedic Aryans were not the first wave to reach India; his Indo-Aryan "Indian Dasa" were the bearers of the Cemetery H culture from around 1900 BC; Asko Parpola, 'The formation of the Aryan branch of Indo-European', in Blench and Spriggs (eds), Archaeology and Language III, London and New York (1999).

- BBC India's miracle river

- Rig Veda VII, 95, 2. giríbhya aaZ samudraZat

- Kazanas 2000:4

- Talageri, 2000: Ch 4: The Rigvedic Rivers

- Rao 1991: 77-9

- Feuerstein et al 1995: 87-90

- Elst 1993: 70

- Allchins 1997: 117

- Francfort 1992

- Rig Veda, Hymn X, 75

- Rig Veda, Hymn X, verses 2-4 and 7-9

- (Kazanas 2000:4, 5)

- Bryant 2001, p. 167 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- Allchins 1969: 285

- Rao 1991: 171

- Allchins et. all cited by Kazanas 2000:1

- ^ Rig-Veda is pre-Harappan by N Kazanas Cite error: The named reference "Rig-Veda is pre-Harappan - 2006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Piggott 1961: 259

- Grist 1965

- Rao 1991: 24, 101, 150 etc

- Piggott et. all cited by Kazanas 2000:13

- Elst 1999: Ch 5.3.10

- RV 10:85:2

- Bernard Sergent: Genèse de l’Inde, 1997 p.118 cited by Elst 1999: Ch 5.5) Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate by Koenraad Elst

- Cardona 2002: 33-35; Cardona, George. The Indo-Aryan languages, RoutledgeCurzon; 2002 ISBN 0-7007-1130-9

- ^ The Indo-Iranian Homeland Ch.6 by Shrikant Talageri

- Elst 1999: Ch 4.6

- Compare the absence of "Urheimat memories" in Magyars and Turks.

- e.g. Thomas Oberlies, Die Religion des Rgveda, Wien 1998, p. 188.

- some scholars assume that RV 8 in particular does preserve records of that period, reminiscencing on Indo-Aryan clashes with the BMAC, but admittedly without being able to prove this conclusively

- Allchins 1997: 223

- Witzel 1995: 113

- `The AIT and scholarship' by Kazanas July 2001 Page 2,3

- Talageri, 2000: Ch 6: The Indo-Iranian Homeland

- ibid.,p. 160 pp.166-67 - The earliest mention of Iranians in historical sources is, paradoxically, of those settled on the Iranian plateau, not those still in Central Asia, their ancestral homeland. The Persians are first mentioned in the 9th century BC Assyrian annals. There are no literary sources for Iranians in Central Asia before the Old Persian Behistun inscription

- ibid., p.163

- Gnoli, 1980

- Zoroaster’s Time and Homeland: A Study on the Origins of Mazdeism and Related Problems by Gherardo Gnoli, Instituto Universitario Orientale, Seminario di Studi Asiatici, (Series Minor VII), Naples, 1980., p.45.

- Talageri, 2000: Ch 6: The Indo-Iranian Homeland

- Indo-Iranian Studies: by J.C. Tavadia, Vishva Bharati, Santiniketan, 1950, pp.3-4; mentioning metric relationship between the Rigveda and the Avesta, in particular the special similarity of the Avesta and RV 8

- The Gathas of Zarathushtra and the Other Old Avestan Texts, Part I: Introduction, Texts and Translation by Helmut Humbach (in collaboration with Josef Elfenbein and P.O. Skjærvø), Carl Winter, Universitätsverlag, Heidelberg (Germany), 1991., p.23 - It must be emphasised that the process of polarisation of relations between the Ahuras and the DaEvas is already complete in the GAthAs, whereas, in the Rigveda, the reverse process of polarisation between the Devas and the Asuras, which does not begin before the later parts of the Rigveda, develops as it were before our very eyes, and is not completed until the later Vedic period. Thus, it is not at all likely that the origins of the polarisation are to be sought in the prehistorical, the Proto-Aryan period. More likely, Zarathushtra’s reform was the result of interdependent developments, when Irano-Indian contacts still persisted at the dawn of history. With their Ahura-DaEva ideology, the Mazdayasnians, guided by their prophet, deliberately dissociated themselves from the Deva-Asura concept which was being developed, or had been developed, in India, and probably also in the adjacent Iranian-speaking countries… All this suggests a synchrony between the later Vedic period and ZarathuStra’s reform in Iran.

- Mallory 1989

- e.g., Asko Parpola (1988), Mayrhofer (1986-1996), Benveniste (1973), Lecoq (1990), Windfuhr (1999)

- Mallory 1989

- e.g., Asko Parpola (1988), Mayrhofer (1986-1996), Benveniste (1973), Lecoq (1990), Windfuhr (1999)

- Demise of the Aryan Invasion Theory by Dr. Dinesh Agarwal. So called facts in support of Invasion theory

- Lothal

- Bryant 2001, p. 231 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFBryant2001 (help)

- J. M. Kenoyer: “The Indus Valley Tradition of Pakistan and Western India”, Journal of World Prehistory, 1991/4; cited in Bryant 2001:190

- (Hemphill, Lukacs and Kennedy 1991, see also Kenneth Kennedy 1995)

- G Chaubey; et al. (2007). "Peopling of South Asia: investigating the caste-tribe continuum in India". Bioessays. 29 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - e.g. Wells et al. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 10244–10249.

- Sahoo et al., A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios (2006)

- National Geographic India acquired language, not genes from West, study says Brian Handwork. January 10 2006

- Parpola writes: "...numerous loanwords and even structural borrowings from Dravidian have been identified in Sanskrit texts composed in northwestern India at the end of the second and first half of the first millennium BCE, before any intensive contact between North and South India. External evidence thus suggests that the Harappans most probably spoke a Dravidian language."

- "The most obvious explanation of this situation is that the Dravidian languages once occupied nearly all of the Indian subcontinent and it is the intrusion of Indo-Aryans that engulfed them in north India leaving but a few isolated enclaves." Mallory 1989

Bibliography and References

- Template:Harvard reference

- Template:Harvard reference

- Elst, Koenraad (1999). [[Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate]]. Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-86471-77-4.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Kazanas, Nicholas (2002b). "Indigenous Indo-Aryans and the Rigveda". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 30: 275–334.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - Kazanas, Nicholas (2003). "Final Reply". Journal of Indo-European Studies. 31: 187–240.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Kazanas, Nicholas (June, 2001). "A new date for the Rgveda" (PDF). special issue of Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Kivisild, Toomas et al. 2003b. "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations" Am J Hum Genet 72: 313–332,

- Mallory, JP. 1998. A European Perspective on Indo-Europeans in Asia. In: The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern and Central Asia. Ed. Mair. Washingion DC: Institute for the Study of Man.

- E. E. Kuz'mina, Откуда пришли индоарии? (Whence came the Indo-Aryans), Nauk, Moscow (1994); review: Diakonoff, Journal of the American Oriental Society (1995), 473-477.

- Template:Harvard reference

- Talageri, Shrikant G. (2000). [[The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis]]. Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-010-0.

{{cite book}}: URL–wikilink conflict (help) - Thomason, Sarah and Terrence Kaufman (1988). Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-07893-4.

See also

- Indigenous Aryan Theory

- Aryan Invasion Theory (history and controversies)

- Indo-Aryan migration

- pre-Indo-European

- Proto-Indo-European language

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Urheimat

- Indomania, Indophobia

- In Search of the Cradle of Civilization

External links

- Web Index to AIT versus OIT debate

- Rig-Veda is pre-Harappan by Nicholas Kazanas

- The RV date — a postscript by Nicholas Kazanas

- Linguistic aspects of the Aryan non-invasion theory (Koenraad Elst)

- The Proto-Vedic Continuity Theory of Bharatiya (Indian) Languages (S. Kalyanaraman and M. Kelkar)

- The RigVeda - A Historical Analysis by Shrikant Talageri

- The RigVeda IndexRalph T.H. Griffith, Translator 1896

- The Homeland of Indo-European Languages and Culture: Some Thoughts By B.B. Lal

- Why Perpetuate Myths ? - A Fresh Look at Ancient Indian History By B.B. Lal