| Revision as of 13:17, 30 April 2014 view sourceMaterialscientist (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Autopatrolled, Checkusers, Administrators1,994,296 editsm Reverted edits by Dumbbbumble (talk) to last version by Pinethicket← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:04, 24 November 2024 view source Mukogodo (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,893 edits →Current conservation status | ||

| (833 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Largest species of toothed whale}} | |||

| {{redirect|Cachalot}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Cachalot}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2013}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Kashalot|the Soviet submarine|Kashalot-class submarine}} | |||

| {{About||the 2015 film|Sperm Whale (film){{!}}Sperm Whale (film)}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | {{pp-move-indef}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=August 2021}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Speciesbox | |||

| | fossil_range = {{fossil range|3.6|0|] – Recent|ref=<ref>{{cite web|url=https://paleobiodb.org/classic/checkTaxonInfo?taxon_no=68698 |title=''Physeter macrocephalus'' Linnaeus 1758 (sperm whale)|website=Fossilworks: Gateway to the Paleobiology Database |access-date=17 December 2021}}</ref>}} | |||

| | name = Sperm whale<ref name="msw3">{{MSW3 Cetacea | id=14300131 | page=737}}</ref> | | name = Sperm whale<ref name="msw3">{{MSW3 Cetacea | id=14300131 | page=737}}</ref> | ||

| | status = VU | | status = VU | ||

| | status_system = |

| status_system = IUCN3.1 | ||

| | status_ref = <ref name="iucn">{{cite iucn |author=Taylor, B.L. |author2=Baird, R. |author3=Barlow, J. |author4=Dawson, S.M. |author5=Ford, J. |author6=Mead, J.G. |author7=Notarbartolo di Sciara, G. |author8=Wade, P. |author9=Pitman, R.L. |year=2019 |amends=2008 |title=''Physeter macrocephalus'' |page=e.T41755A160983555 |doi=10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T41755A160983555.en}}</ref> | |||

| | status_ref =<ref name="iucn" /> | |||

| | status2 = CITES_A1 | |||

| | status2_system = CITES | |||

| | status2_ref = <ref name="CITES">{{Cite web|title=Appendices {{!}} CITES|url=https://cites.org/eng/app/appendices.php|access-date=2022-01-14|website=cites.org}}</ref> | |||

| | image = Mother and baby sperm whale.jpg | | image = Mother and baby sperm whale.jpg | ||

| | image_caption = | | image_caption = | ||

| | image2 = Sperm |

| image2 = Sperm-Whale-Scale-Chart-SVG-Steveoc86.svg | ||

| | image2_caption = | | image2_caption = | ||

| | |

| genus = Physeter | ||

| | species = macrocephalus | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | authority = ], ] | |||

| | classis = ]ia | |||

| | |

| synonyms = | ||

| *''Physeter catodon'' {{small|Linnaeus, 1758}} | |||

| | subordo = ] | |||

| *''Physeter microps'' {{small|Linnaeus, 1758}} | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| *''Physeter tursio'' {{small|Linnaeus, 1758}} | |||

| | genus = '''''Physeter''''' | |||

| *''Physeter australasianus'' {{small|], 1822}} | |||

| | genus_authority = Linnaeus, 1758 | |||

| | species = '''''P. macrocephalus''''' | |||

| | binomial = ''Physeter macrocephalus'' | |||

| | binomial_authority = ], ] | |||

| | synonyms = ''Physeter catodon'' <small>Linnaeus, 1758</small><br> | |||

| ''Physeter australasianus'' <small>], 1822</small>re | |||

| | range_map = Sperm whale distribution (Pacific equirectangular).jpg | | range_map = Sperm whale distribution (Pacific equirectangular).jpg | ||

| | range_map_caption= Major sperm whale grounds | | range_map_caption= Major sperm whale grounds | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''sperm whale''' |

The '''sperm whale''' or '''cachalot'''{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|ʃ|ə|l|ɒ|t|,_|ˈ|k|æ|ʃ|ə|l|oʊ}} – {{OED|cachalot}}}} ('''''Physeter macrocephalus''''') is the largest of the ]s and the largest toothed ]. It is the only living member of the ] '']'' and one of three extant ] in the ], along with the ] and ] of the genus '']''. | ||

| The sperm whale is a ] ] with a worldwide range, and will migrate seasonally for feeding and breeding.<ref>{{cite web |title=Sperm Whale|url=http://acsonline.org/fact-sheets/sperm-whale/|website=acsonline.org |access-date=13 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170422154853/http://acsonline.org/fact-sheets/sperm-whale/|archive-date=22 April 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref> Females and young males live together in groups, while mature males (bulls) live solitary lives outside of the mating season. The females cooperate to protect and ] their young. Females give birth every four to twenty years, and care for the calves for more than a decade. A mature, healthy sperm whale has no natural predators, although calves and weakened adults are sometimes killed by ] of ]s (orcas). | |||

| Mature males average at {{convert|16|m|ft}} in length but some may reach {{convert|20.5|m|ft}}, with the head representing up to one-third of the animal's length. The sperm whale feeds primarily on ]. Plunging to {{convert|2250|m|ft}} for prey, it is the second deepest diving mammal, following only the ].<ref name=NatGeoDeepest>{{cite web |title=Elusive Whales Set New Record for Depth and Length of Dives Among Mammals |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140326-cuvier-beaked-whale-record-dive-depth-ocean-animal-science/ |author=Lee, Jane J. |archiveurl= http://www.webcitation.org/6OQPfmHCj |date=2014-03-26 |archivedate=2014-03-29 |publisher=''National Geographic'' }}</ref> The sperm whale's clicking vocalization, a form of ] and communication, may be as loud as 230 ]s (re 1 µPa at 1 m) underwater,<ref name="natgeo">{{cite web | |||

| | url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/11/1103_031103_tvspermwhale.html |work=news.nationalgeographic.com|author=Trivedi, Bijal P. |date=3 November 2003| title=Sperm Whale "Voices" Used to Gauge Whales' Sizes | |||

| }}</ref> making it the loudest sound produced by any animal. It has the largest brain of any animal on Earth, more than five times heavier than a human's. Sperm whales can live for more than 60 years.<ref name=Degratietal2011>{{cite journal|author=Degrati, M., García, NA, Grandi, MF, Leonardi, MS, de Castro, R, Vales, D., Dans, S., Pedraza, SN & Crespo EA|url=http://www.scielo.org.ar/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0327-93832011000200013&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en |year=2011|title=The oldest sperm whale (''Physeter macrocephalus''): new record with notes on age, diet and parasites, and a review of strandings along the continental Argentine coast|journal= Mastozoología Neotropical|volume=18|issue=2}}</ref> | |||

| Mature males average {{convert|16|m|ft}} in length, with the head representing up to one-third of the animal's length. Plunging to {{convert|2250|m|ft|-1}}, it is the third deepest diving mammal, exceeded only by the ] and ].<ref name=plosone-2014/><ref name=Elephantseal/> The sperm whale uses ] and ] with source level as loud as 236 ]s (re 1 μPa m) underwater,<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Møhl |first1=Bertel |last2=Wahlberg |first2=Magnus |last3=Peter T. Madsen |title=The monopulsed nature of sperm whale clicks |journal=The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America |date=2003 |volume=114 |issue=2 |pages=1143–1154 |doi=10.1121/1.1586258 |pmid=12942991 |bibcode=2003ASAJ..114.1143M }}</ref><ref name="natgeo">{{cite web| url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/11/1103_031103_tvspermwhale.html | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031106044251/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/11/1103_031103_tvspermwhale.html | url-status=dead | archive-date=6 November 2003 |work=National Geographic|author=Trivedi, Bijal P. |date=3 November 2003| title=Sperm Whale "Voices" Used to Gauge Whales' Sizes}}</ref> the loudest of any animal.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20160331-the-worlds-loudest-animal-might-surprise-you|title=The world's loudest animal might surprise you|last=Davies|first=Ella|publisher=BBC|language=en|access-date=2020-01-13}}</ref> It has the largest brain on Earth, more than five times heavier than a human's. Sperm whales can live 70 years or more.<ref name="princeton">{{cite book|author1=Shirihai, H.|title=Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World|author2=Jarrett, B.|publisher=Princeton Univ. Press|year=2006|isbn=978-0-691-12757-6|location=Princeton|pages=21–24|name-list-style=amp}}</ref><ref name="audubon" /><ref name="Cetacean Societies">{{cite book|title=Cetacean Societies|chapter=The Sperm Whale|author1=Whitehead, H.|author2=Weilgart, L.|name-list-style=amp|editor=Mann, J.|editor2=Connor, R.|editor3=Tyack, P.|editor4=Whitehead, H.|year=2000|page=|publisher=The University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-50341-7|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/cetaceansocietie0000unse/page/169}}</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale can be found anywhere in the open ocean. Females and young males live together in groups while mature males live solitary lives outside of the mating season. The females cooperate to protect and ] their young. Females give birth every four to twenty years, and care for the calves for more than a decade. A mature sperm whale has few natural predators. Calves and weakened adults are taken by pods of ]. | |||

| Sperm whales' heads are filled with a waxy substance called "]" (sperm oil), from which the whale derives its name. Spermaceti was a prime target of the ] industry and was sought after for use in oil lamps, lubricants, and candles. ], a solid waxy waste product sometimes present in its digestive system, is still highly valued as a ], among other uses. Beachcombers look out for ambergris as ].<ref>{{cite news|last1=Spitznagel|first1=Eric|title=Ambergris, Treasure of the Deep|url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2012-01-12/ambergris-treasure-of-the-deep|access-date=25 May 2017|publisher=Bloomberg L.P.|date=12 January 2012}}</ref> ] was a major industry in the 19th century, depicted in the novel '']''. The species is protected by the ] moratorium, and is listed as ] by the ]. | |||

| == Taxonomy and naming == | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The name ''sperm whale'' is a ] of ''spermaceti whale''. ], originally mistakenly identified as the whales' ], is the semi-liquid, waxy substance found within the whale's head (]).<ref name="WahlbergEtAl2005">{{cite journal |doi=10.1121/1.2126930 |pmid=16419786 |title=Click production during breathing in a sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) |journal=The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America |volume=118 |issue=6 |pages=3404–7 |year=2005 |last1=Wahlberg |first1=Magnus |last2=Frantzis |first2=Alexandros |last3=Alexiadou |first3=Paraskevi |last4=Madsen |first4=Peter T. |last5=Møhl |first5=Bertel |bibcode=2005ASAJ..118.3404W}}</ref> | |||

| === Etymology === | |||

| The sperm whale is also known as the "cachalot", which is thought to derive from the archaic French for "tooth" or "big teeth", as preserved for example in ''cachau'' in the ] dialect (a word of either ]<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| The name "sperm whale" is a clipping of "spermaceti whale". ], originally mistakenly identified as the whales' ], is the semi-liquid, waxy substance found within the whale's head.<ref name="WahlbergEtAl2005">{{cite journal |doi=10.1121/1.2126930 |pmid=16419786 |title=Click production during breathing in a sperm whale (''Physeter macrocephalus'') |journal=The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America |volume=118 |issue=6 |pages=3404–7 |year=2005 |last1=Wahlberg |first1=Magnus |last2=Frantzis |first2=Alexandros |last3=Alexiadou |first3=Paraskevi |last4=Madsen |first4=Peter T. |last5=Møhl |first5=Bertel |bibcode=2005ASAJ..118.3404W}}</ref> | |||

| | author=Haupt, P. | title=Jonah's Whale | year=1907 | |||

| (''See "]" below.'') | |||

| | journal=Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society | volume=46| issue=185 | |||

| | isbn=978-1-4223-7345-3 | page=155 | |||

| The sperm whale is also known as the "cachalot", which is thought to derive from the archaic French for 'tooth' or 'big teeth', as preserved for example in the word {{lang|oc|caishau}} in the ] dialect (a word of either ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Haupt |first1=Paul |title=Jonah's Whale |journal=Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society |date=1907 |volume=46 |issue=185 |pages=151–164 |jstor=983449 }}</ref> | |||

| | url=http://books.google.com/?id=7lgLAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA151 | |||

| or ]<ref>{{cite journal | author=Fеrnandez-Casado, M. | title=El Cachalote (''Physeter macrocephalus'') | year=2000 | journal=Galemys | volume=12 | issue=2 | page=3 | url=http://www.secem.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/G-12-2-1-Fernandez-Casado-3-22.pdf | access-date=27 September 2013 | archive-date=7 August 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200807134359/http://www.secem.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/G-12-2-1-Fernandez-Casado-3-22.pdf | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| }}</ref> or ]<ref>{{cite journal | |||

| origin). | |||

| | author= Fеrnandez-Casado, M. | title=El Cachalote (''Physeter macrocephalus'') | year=2000 | |||

| | journal=Galemys |volume= 12| issue=2| page=3|url=http://www.secem.es/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/G-12-2-1-Fernandez-Casado-3-22.pdf}}</ref> origin). The etymological dictionary of Corominas says the origin is uncertain, but it suggests that it comes from the Vulgar Latin ''cappula'', plural of ''cappulum'', sword hilt.<ref> | |||

| The etymological dictionary of ] says the origin is uncertain, but it suggests that it comes from the ] {{lang|la|cappula}} 'sword hilts'.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | {{cite book | ||

| | title=Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana | | title=Breve diccionario etimológico de la lengua castellana | ||

| | last=Corominas |

| last=Corominas | ||

| | first=Joan | |||

| | isbn |

| isbn=978-84-249-1332-8 | ||

| | year=1987 | | year=1987 | ||

| | publisher=Gredos | | publisher=Gredos | ||

| | location=Madrid | | location=Madrid | ||

| | url=https://archive.org/details/brevediccionario00colo | |||

| }}</ref> According to ], the word ''cachalot'' came to English "via French from Spanish or Portuguese ''cachalote'', perhaps from Galecian/Portuguese ''cachola'', 'big head'". The term is retained in the Russian word for the animal, кашалот (kashalot), as well as in many other languages. | |||

| }}</ref> The word ''cachalot'' came to English via French from Spanish or Portuguese {{wikt-lang|es|cachalote}}, perhaps from ]/Portuguese {{wikt-lang|pt|cachola}} 'big head'.<ref>Encarta Dictionary</ref> | |||

| The term is retained in the Russian word for the animal, {{transliteration|ru|kashalot}} ({{wikt-lang|ru|кашалот}}), as well as in many other languages.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| The scientific genus name ''Physeter'' comes from the ] {{transliteration|grc|physētēr}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|φυσητήρ}}), meaning 'blowpipe, blowhole (of a whale)', or – as a '']'' – 'whale'.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| The specific name ''macrocephalus'' is Latinized from the Greek {{transliteration|grc|makroképhalos}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|μακροκέφαλος}} 'big-headed'), from {{transliteration|grc|makros}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|μακρός}}) + {{transliteration|grc|kephalē}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|κεφαλή}}).{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| Its synonymous specific name ''catodon'' means 'down-tooth', from the Greek elements {{wikt-lang|grc-Latn|cata-|cat(a)-}} ('below') and {{wikt-lang|grc-Latn|ὀδών|odṓn}} ('tooth'); so named because it has visible teeth only in its lower jaw.<ref>{{cite book|last=Crabb|first=George|author-link=George Crabb (writer)|title=Universal Technological Dictionary Or Familiar Explanation of the Terms Used in All Arts and Sciences: Containing Definitions Drawn from the Original Writers : in Two Volumes|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jlZBAAAAcAAJ&pg=PT333|year=1823|publisher=Baldwin, Cradock & Joy|page=333}}</ref> (''See "]" below.'') | |||

| Another synonym ''australasianus'' (']n') was applied to sperm whales in the Southern Hemisphere.<ref>{{cite book|last=Ridgway|first=Sam H.|title=Handbook of Marine Mammals|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IIQXAQAAIAAJ|year=1989|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=978-0-12-588504-1|page=179|quote= The earliest available species-group name for a Southern Hemisphere sperm whale is ''Physeter australasianus'' Desmoulins, 1822.}}</ref> | |||

| === Taxonomy === | |||

| The sperm whale belongs to the ] ],<ref>{{multiref | |||

| |1={{cite journal |title=The phylogeny of Cetartiodactyla: the importance of dense taxon sampling, missing data, and the remarkable promise of cytochrome b to provide reliable species-level phylogenies. |journal=Mol Phylogenet Evol |year=2008 |last1=Agnarsson |first1=I. |last2=May-Collado |first2=LJ. |volume=48 |issue=3 |pages=964–985 |doi=10.1016/j.ympev.2008.05.046 |pmid=18590827|bibcode=2008MolPE..48..964A }} | |||

| |2={{cite journal |title=A complete phylogeny of the whales, dolphins and even-toed hoofed mammals (Cetartiodactyla). |journal=Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc |year=2005 |last1=Price |first1=SA. |last2=Bininda-Emonds |first2=OR. |last3=Gittleman |first3=JL. |volume=80 |issue=3 |pages=445–473 |doi=10.1017/s1464793105006743 |pmid=16094808|s2cid=45056197 }} | |||

| |3={{cite journal |title=Phylogenetic relationships of artiodactyls and cetaceans as deduced from the comparison of cytochrome b and 12S RNA mitochondrial sequences. |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |year=1997 |last1=Montgelard |first1=C. |last2=Catzeflis |first2=FM. |last3=Douzery |first3=E. |volume=14 |pages=550–559 |doi=10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025792 |pmid=9159933 |issue=5 |doi-access=free }} | |||

| |4={{cite journal |title=Relationships of Cetacea (Artiodactyla) Among Mammals: Increased Taxon Sampling Alters Interpretations of Key Fossils and Character Evolution. |journal=PLOS ONE|year=2009 |last1= Spaulding |first1=M. |last2=O'Leary |first2=MA. |last3=Gatesy |first3=J. |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0007062 |pmid=19774069 |pmc=2740860 |volume=4 |issue=9 |pages=e7062|bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.7062S|doi-access=free}} | |||

| |5={{cite web|url=http://www.marinemammalscience.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=758&Itemid=340|title=Society for Marine Mammalogy|work=The Insomniac Society}}}}</ref> the order containing all ] and ]. It is a member of the unranked clade ], with all the whales, dolphins, and porpoises, and further classified into ], containing all the toothed whales and dolphins. It is the sole extant species of its genus, '']'', in the family ]. Two species of the related extant genus '']'', the ] ''Kogia breviceps'' and the ] ''K. sima'', are placed either in this family or in the family ].<ref>{{MSW3 Cetacea|id=14300126}}</ref> In some taxonomic schemes the families ] and ] are combined as the superfamily ] (see the separate entry on the ]).<ref name=Acrophyseter/> | |||

| Swedish ichthyologist ] described it as ''Physeter catodon'' in his 1738 work ''Genera piscium'', from the report of a beached specimen in Orkney in 1693 and two beached in the Netherlands in 1598 and 1601.<ref name="Artedi 1730">{{cite book |last1=Artedi |first1=Peter |title=Genera piscium : in quibus systema totum ichthyologiae proponitur cum classibus, ordinibus, generum characteribus, specierum differentiis, observationibus plurimis : redactis speciebus 242 ad genera 52 : Ichthyologiae pars III. |date=1730 |publisher=Grypeswaldiae : Impensis Ant. Ferdin. Röse |pages=–555 |url=https://archive.org/details/petriartedisueci03arte | language=la}}</ref> The 1598 specimen was near Berkhey.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| The sperm whale is one of the species originally described by ] in his landmark 1758 ]. He recognised four species in the genus ''Physeter''.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last=Linnaeus | first=Carolus | |||

| | author-link=Carl Linnaeus | |||

| | title=Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata. | |||

| | publisher=Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). | |||

| | year=1758 | |||

| | page=824 | |||

| |language=la}}</ref> Experts soon realised that just one such species exists, although there has been debate about whether this should be named ''P. catodon'' or ''P. macrocephalus'', two of the names used by Linnaeus. Both names are still used, although most recent authors now accept ''macrocephalus'' as the valid name, limiting ''catodon''{{'s}} status to a lesser synonym. Until 1974, the species was generally known as ''P. catodon''. In that year, however, Dutch zoologists Antonius M. Husson and ] proposed that the correct name should be ''P. macrocephalus'', the second name in the genus ''Physeter'' published by Linnaeus concurrently with ''P. catodon''. | |||

| This proposition was based on the grounds that the names were synonyms published simultaneously, and, therefore, the ICZN ] should apply. In this instance, it led to the choice of ''P. macrocephalus'' over ''P. catodon'', a view re-stated in Holthuis, 1987.<ref>{{cite journal |author = Holthuis L. B. |year=1987 |title=The scientific name of the sperm whale |journal=Marine Mammal Science |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=87–89 |doi=10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00154.x |bibcode=1987MMamS...3...87H }}</ref> This has been adopted by most subsequent authors, although Schevill (1986<ref>{{cite journal |author=Schevill W.E. |year=1986 |title=The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and a paradigm – the name ''Physeter catodon'' Linnaeus 1758 |journal=Marine Mammal Science |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=153–157 |doi=10.1111/j.1748-7692.1986.tb00036.x |bibcode=1986MMamS...2..153S }}</ref> and 1987<ref>{{cite journal |author=Schevill W.E. |year=1987 |title=Reply to L. B. Holthuis "The scientific name of the sperm whale |journal=Marine Mammal Science |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=89–90 |doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1987.tb00155.x }}</ref>) argued that ''macrocephalus'' was published with an inaccurate description and that therefore only the species ''catodon'' was valid, rendering the principle of "First Reviser" inapplicable. The most recent version of ] has altered its usage from ''P. catodon'' to ''P. macrocephalus'',<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.itis.gov/servlet/SingleRpt/SingleRpt?search_topic=TSN&search_value=180489|title=ITIS Standard Report Page: ''Physeter catodon''|access-date=19 January 2015}}</ref> following L. B. Holthuis and more recent (2008) discussions with relevant experts.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Husson A.M. |author2=Holthuis L.B. |year=1974 |title=''Physeter macrocephalus'' Linnaeus, 1758, the valid name for the sperm whale |url=http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/record/318605 |journal=Zoologische Mededelingen |volume=48 |pages=205–217 }}</ref><ref>], p. 3</ref> Furthermore, The Taxonomy Committee of the ], the largest international association of marine mammal scientists in the world, officially uses ''Physeter macrocephalus'' when publishing their definitive ].<ref>{{cite web|title=List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies|url=https://www.marinemammalscience.org/species-information/list-marine-mammal-species-subspecies/|website=marinemammalscience.org|date=13 November 2016 |access-date=25 May 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ==Biology== | |||

| The scientific genus name ''Physeter'' comes from ] φυσητήρ, ''physētēr'', meaning "blowpipe", "blowhole" (of a whale), or (as a '']'') "whale", while the specific epithet ''macrocephalus'' comes from Greek μακροκέφαλος ''makrokephalos'', meaning "big-headed", from μακρός, ''makros'', "large" + κέφαλος, ''kefalos'', "head". | |||

| ===External appearance=== | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| ===Size=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:2px; margin:10px" | {| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:2px; margin:10px" | ||

| |+ Average sizes<ref name="princeton" /><ref name=Hal2003>{{cite book|author=Hal Whitehead|year=2003|chapter=17 – Society and Culture in the Deep and Open Ocean: The Sperm Whale and Other Cetaceans|title=Animal Society Complex: Intelligence, Culture, and Individualized Societies|editor1=Frans B. M. de Waal|editor2=Peter L. Tyack|page=448|publisher=Harvard University Press|doi=10.4159/harvard.9780674419131.c34|isbn=9780674419131}}</ref> | |||

| |+ Average sizes<ref name="princeton" /> | |||

| ! !! Length !! Weight | ! !! Length !! Weight | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Male | ! Male | ||

| | {{convert|16|m|ft}} || {{convert| |

| {{convert|16|m|ft}} || {{convert|45|t|short ton}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Female | ! Female | ||

| | {{convert|11|m|ft}} || {{convert| |

| {{convert|11|m|ft}} || {{convert|15|t|short ton}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Newborn | ! Newborn | ||

| | {{convert|4|m|ft}} || {{convert| |

| {{convert|4|m|ft}} || {{convert|1|t|short ton}} | ||

| |} | |} | ||

| The sperm whale is the largest toothed whale and is among the most ] of all ]s.<ref name=McClain>{{cite journal |last1=McClain |first1=Craig R. |last2=Balk |first2=Meghan A. |last3=Benfield |first3=Mark C. |last4=Branch |first4=Trevor A. |last5=Chen |first5=Catherine |last6=Cosgrove |first6=James |last7=Dove |first7=Alistair D.M. |last8=Gaskins |first8=Leo |last9=Helm |first9=Rebecca R. |last10=Hochberg |first10=Frederick G. |last11=Lee |first11=Frank B. |last12=Marshall |first12=Andrea |last13=McMurray |first13=Steven E. |last14=Schanche |first14=Caroline |last15=Stone |first15=Shane N. |last16=Thaler |first16=Andrew D. |title=Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna |journal=PeerJ |date=13 January 2015 |volume=3 |pages=e715 |doi=10.7717/peerj.715 |pmc=4304853 |pmid=25649000 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Both sexes are about the same size at birth,<ref name="princeton" /> but mature males are typically 30% to 50% longer and three times as massive as females.<ref name="encyc" /><ref name="Nowak-2003">{{Cite book |last1=Nowak |first1=R.M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=89ybgDBCYKoC&dq=sperm+whale+Nowak&pg=PR3 |title=Walker's marine mammals of the world |last2=Walker |first2=E.P. |publisher=JHU Press |year=2003|isbn=9780801873430 }}</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale is the largest toothed whale, with adult males measuring up to {{convert|20.5|m|ft}} long and weighing up to {{convert|57000|kg|ton}}.<ref name=encyc/><ref name="marinebio">{{cite web | |||

| | url=http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=190 | work=marinebio.org | |||

| | title=''Physeter macrocephalus'', Sperm Whale | |||

| }}</ref> By contrast, the ], ] measures {{convert|12.8|m|ft}} and weighs up to {{convert|15|ST|kg}}.<ref>{{cite book|title=Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World|author=Shirihai, H. and Jarrett, B.|pages=112–115|year=2006|isbn=0-691-12757-3|publisher=Princeton Univ. Press|location=Princeton}}</ref> The ] has a {{convert|5.5|m|ft}}-long jawbone. The museum claims that this individual was {{convert|80|ft|m|disp=flip}} long; the whale that sank the '']'' (one of the incidents behind '']'') was claimed to be {{convert|85|ft|m|disp=flip}}. A similar size is reported from a jawbone from the British ]. A 67-foot specimen is reported from a Soviet whaling fleet near the Kurile Islands in 1950.<ref>{{cite book|title=Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts|author=Maury, M.|page=297|year=1853|publisher=C. Alexander|url=http://books.google.com/?id=DH8TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA313}}</ref><ref name="SpermwhalesDotInfo"/> There is disagreement on the claims of adult males approaching or exceeding {{convert|80|ft|m|disp=flip}} in length.<ref>{{Cite book| last = Ellis| first = Richard|title = The Great Sperm Whale: A Natural History of the Ocean's Most Magnificent and Mysterious Creature| publisher = University Press of Kansas| series = Zoology| volume = 179| location = USA| year = 2011| page = 432| isbn = 978-0-7006-1772-2| zbl = 0945.14001}}</ref> | |||

| Newborn sperm whales are usually between {{convert|3.7|and|4.3|m|ft|sp=us|abbr=}} long.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Ruelas-Inzunza |first1=J |last2=Páez-Osuna |first2=F |title=Distribution of Cd, Cu, Fe, Mn, Pb and Zn in selected tissues of juvenile whales stranded in the SE Gulf of California (Mexico) |journal=Environment International |date=September 2002 |volume=28 |issue=4 |pages=325–329 |doi=10.1016/s0160-4120(02)00041-7 |pmid=12220119 |bibcode=2002EnInt..28..325R }}</ref> Female sperm whales are sexually mature at {{convert|8|to|9|m|abbr=|sp=us|ft}} in length, whilst males are sexually mature at {{convert|11|to|12|m|abbr=|sp=us|ft}}.<ref name="Dufault-1999">{{cite journal |last1=Dufault |first1=S. |last2=Whitehead |first2=H. |last3=Dillon |first3=D. |title=An examination of the current knowledge on the stock structure of sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) worldwide |journal=Journal of Cetacean Research and Management |date=1999 |volume=1 |issue=1 |pages=1–10 |doi=10.47536/jcrm.v1i1.447 |s2cid=256290992 |doi-access=free }}</ref> Female sperm whales are physically mature at about {{convert|10.6|to|11|m|ft|sp=us|abbr=}} in length and generally do not achieve lengths greater than {{convert|12|m|ft|abbr=}}.<ref name=McClain/><ref name="Nowak-2003" /><ref name="Dufault-1999" /> The largest female sperm whale measured up to {{convert|12.3|m|ft|sp=us}} long, and an individual of such size would have weighed about {{convert|17|t|ST}}.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Clarke|first1=R.|last2=Paliza|first2=O.|last3=Van Waerebeek|first3=K.|year=2011|title=Sperm whales of the Southeast Pacific. Part VII. Reproduction and growth in the female|journal=Latin American Journal of Aquatic Mammals|volume=10|issue=1|pages=8–39|doi=10.5597/lajam00172|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last=Omura|first=H.|year=1950|title=On the Body Weight of Sperm and Sei Whales located in the Adjacent Waters of Japan|journal=Scientific Reports of the Whales Research Institute, Tokyo|volume=4|pages=27–113}}</ref> Male sperm whales are physically mature at about {{convert|15|to|16|m|abbr=|sp=us|ft}} in length, and larger males can generally achieve {{convert|18|to|19|m|ft|sp=us}}.<ref name="Dufault-1999" /><ref name="Ellis-2011">{{Cite book|last=Ellis|first=Richard|url=https://archive.org/details/greatspermwhalen0000elli/page/432|title=The Great Sperm Whale: A Natural History of the Ocean's Most Magnificent and Mysterious Creature|publisher=University Press of Kansas|year=2011|isbn=978-0-7006-1772-2|series=Zoology|volume=179|location=USA|page=|zbl=0945.14001}}</ref><ref name="McClain" /> An {{convert|18|m|ft|sp=us}} long male sperm whale is estimated to have weighed {{convert|57|t|ton}}.<ref name=Hal2003/> By contrast, the ] (]) measures up to {{convert|12.8|m|ft|sp=us}} and weighs up to {{convert|14|t|ST}}.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Shirihai, H. |title=Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World |author2=Jarrett, B. |publisher=Princeton Univ. Press |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-691-12757-6 |location=Princeton |pages=112–115 |name-list-style=amp}}</ref> | |||

| Extensive whaling may have decreased their size, as males were highly sought, primarily after ].<ref name="SpermwhalesDotInfo">{{cite web|title=Sperm Whale|url=http://www.spermwhales.info|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20070220113910/http://www.spermwhales.info/ |archivedate=2007-02-20}}</ref> Today, males do not usually exceed {{convert|18.3|m|ft}} in length or {{convert|51000|kg|ton}} in weight.<ref name="princeton" /> Another view holds that exploitation by overwhaling had virtually no effect on the size of the bull sperm whales, and their size may have actually increased in current times on the basis of density dependent effects.<ref>{{Cite journal| last = Kasuya| first = Toshio| title =Density dependent growth in North Pacific sperm whales | journal = Marine Mammal Science| volume = 7| issue = 3| pages = 230–257| publisher = Wiley| location = USA| date = July 1991| doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1991.tb00100.x}}</ref> | |||

| There are occasional reports of individual sperm whales achieving even greater lengths, with some historical claims reaching or exceeding {{convert|80|ft|m|abbr=}}. One example is the whale that sank the '']'' (one of the incidents behind '']''), which was claimed to be {{convert|85|ft|m|abbr=}}. However, there is disagreement as to the accuracy of some of these claims, which are often considered exaggerations or as being measured along the curves of the body.<ref name="Wood">{{cite book |author=Wood, Gerald |url=https://archive.org/details/guinnessbookofan00wood/page/256 |title=The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats |year=1983 |isbn=978-0-85112-235-9 |page= |publisher=Guinness Superlatives |url-access=registration}}</ref><ref name="McClain" /><ref name="Ellis-2011" /> | |||

| It is among the most ] of all ]s. At birth both sexes are about the same size,<ref name="princeton">{{cite book|title=Whales, Dolphins, and Other Marine Mammals of the World|author=Shirihai, H. and Jarrett, B.|pages=21–24|year=2006|isbn=0-691-12757-3|publisher=Princeton Univ. Press|location=Princeton}}</ref> but mature males are typically 30% to 50% longer and three times as massive as females.<ref name="encyc" /> | |||

| An individual measuring {{convert|20.7|m|ft}} was reported from a ] fleet near the ] in 1950 and is cited by some authors as the largest accurately measured.<ref name="McClain" /><ref name="Carwardine">{{Cite book |last=Carwardine, Mark. |title=The Guinness book of Animal records |date=1995 |publisher=Guinness Publishing |isbn=978-0851126586 |location=Enfield |oclc=60244977}}</ref> It has been estimated to weigh {{convert|80|t|ton}}.<ref name="Wood" /> In a review of size variation in marine megafauna, McClain and colleagues noted that the International Whaling Commission's data contained eight individuals larger than {{convert|20.7|m|ft|abbr=}}. The authors supported a {{convert|24|m|ft|abbr=|adj=on}} male from the South Pacific in 1933 as the largest recorded. However, sizes like these are rare, with 95% of recorded sperm whales below 15.85 metres (52.0 ft).<ref name="McClain" /> | |||

| ===Appearance=== | |||

| The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped ] is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left.<ref name="encyc">Whitehead, H. "Sperm whale ''Physeter macrocephalus''", pp. 1165–1172 in ]</ref> This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray. | |||

| In 1853, one sperm whale was reported at {{convert|62|ft|m}} in length, with a head measuring {{convert|20|ft|m}}.<ref>{{cite book |author=Maury, M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DH8TAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA313 |title=Explanations and Sailing Directions to Accompany the Wind and Current Charts |publisher=C. Alexander |year=1853 |page=297}}</ref> Large lower jawbones are held in the British ] and the ], measuring {{convert|5|m|ft|abbr=}} and {{convert|4.7|m|ft|abbr=}}, respectively.<ref name="Wood" /> | |||

| The sperm whale's ] are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible.<ref>Gordon, Jonathan (1998). ''Sperm Whales'', Voyageur Press, p. 14, ISBN 0-89658-398-8</ref> The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive.<ref name="encyc" /> It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a ]. The largest ridge was called the 'hump' by whalers, and can be mistaken for a ] because of its shape and size.<ref name="princeton"/> | |||

| The average size of sperm whales has decreased over the years, probably due to pressure from whaling.<ref name="McClain" /> Another view holds that exploitation by overwhaling had virtually no effect on the size of the bull sperm whales, and their size may have actually increased in current times on the basis of density dependent effects.<ref>{{Cite journal| last = Kasuya| first = Toshio| title =Density dependent growth in North Pacific sperm whales | journal = Marine Mammal Science| volume = 7| issue = 3| pages = 230–257| publisher = Wiley| location = USA| date = July 1991| doi = 10.1111/j.1748-7692.1991.tb00100.x| bibcode = 1991MMamS...7..230K}}</ref> Old males taken at ] were recorded to be extremely large and unusually rich in blubbers.<ref>{{citation |url=http://docs.niwa.co.nz/library/public/NIWAis76.pdf |title=Sperm whaling on the Solanders Grounds and in Fiordland – A maritime historian's perspective |last=Richards |first=Rhys |work=NIWA |series=NIWA Information Series No. 76 }}</ref> | |||

| In contrast to the smooth skin of most large whales, its back skin is usually wrinkly and has been likened to a ] by whale-watching enthusiasts.<ref name="prune">{{cite book | author=Carwardine, Mark | title=On the Trail of the Whale | publisher=Chapter 1. Thunder Bay Publishing Co | year=1994 | isbn=1-899074-00-7}}</ref> ]s have been reported.<ref name="audobon">{{cite book|title=Guide to Marine Mammals of the World|author=Reeves, R., Stewart, B., Clapham, P. & Powell, J.|pages=240–243|year=2003|isbn=0-375-41141-0|publisher=A.A. Knopf|location=New York}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Sperm Whale (''Physeter macrocephalus''): Species Accounts|url=http://animals.jrank.org/pages/3164/Sperm-Whales-Physeteridae-SPERM-WHALE-Physeter-macrocephalus-SPECIES-ACCOUNTS.html|accessdate=2008-10-12}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Offshore Cetacean Species|url=http://www.coreresearch.org/education/offshorespecies.htm|publisher=CORE|accessdate=2008-10-12}}</ref> | |||

| ], the sperm whale's blowhole is highly skewed to the left side of the head.]] | |||

| ===Skeleton=== | |||

| The sperm whale's unique body is unlikely to be confused with any other species. The sperm whale's distinctive shape comes from its very large, block-shaped head, which can be one-quarter to one-third of the animal's length. The S-shaped ] is located very close to the front of the head and shifted to the whale's left.<ref name="encyc">{{cite book|author=Whitehead, H.|year=2002|chapter=Sperm whale ''Physeter macrocephalus''|pages=|editor=Perrin, W.|editor2=Würsig B.|editor3=], J.|title=Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=978-0-12-551340-1|chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofma2002unse/page/1165}}</ref> This gives rise to a distinctive bushy, forward-angled spray.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| |title=Sperm whale skeleton | |||

| |width=60 | |||

| |height=130 | |||

| |lines=0 | |||

| |align=center | |||

| |File:Sperm whale skeleton.jpg|width1=600| | |||

| |File:Sperm whale skeleton front.jpg|width2=140| | |||

| |File:Baltic sperm whale.jpg|width3=200 | |||

| }} | |||

| The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure.<ref>. Oceanservice.noaa.gov (2013-01-11). Retrieved on 2013-03-19.</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale's ] (tail lobes) are triangular and very thick. Proportionally, they are larger than that of any other cetacean, and are very flexible.<ref>Gordon, Jonathan (1998). ''Sperm Whales'', Voyageur Press, p. 14, {{ISBN|0-89658-398-8}}</ref> The whale lifts its flukes high out of the water as it begins a feeding dive.<ref name="encyc" /> It has a series of ridges on the back's caudal third instead of a ]. The largest ridge was called the 'hump' by whalers, and can be mistaken for a dorsal fin because of its shape and size.<ref name="princeton"/> | |||

| As with other ]s, the skull of the sperm whale is asymmetrical so as to aid ]. Sound waves that strike the whale from different directions will not be channeled in the same way.<ref>. Io9.com. Retrieved on 2013-03-19.</ref> Within the basin of the cranium, the openings of the bony narial tubes (from which the nasal passages spring) are skewed towards the left side of the skull. | |||

| In contrast to the smooth skin of most large whales, its back skin is usually wrinkly and has been likened to a ] by whale-watching enthusiasts.<ref name="prune">{{cite book | author=Carwardine, Mark | title=On the Trail of the Whale | publisher=Chapter 1. Thunder Bay Publishing Co | year=1994 | isbn=978-1-899074-00-6 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/ontrailofwhale0000carw }}</ref> ]s have been reported.<ref name="audubon">{{cite book|title=Guide to Marine Mammals of the World|author=Reeves, R.|author2=Stewart, B.|author3=Clapham, P.|author4=Powell, J.|name-list-style=amp|pages=|year=2003|isbn=978-0-375-41141-0|publisher=A.A. Knopf|location=New York|url=https://archive.org/details/guidetomarinemam00folk/page/240}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Offshore Cetacean Species|url=http://www.coreresearch.org/education/offshorespecies.htm|publisher=CORE|access-date=2008-10-12|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080516101558/http://www.coreresearch.org/education/offshorespecies.htm|archive-date=16 May 2008}}</ref> | |||

| ===Jaws and teeth=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung.<ref name="Jefferson">{{cite book|title=Marine Mammals of the World: a comprehensive guide to their identification|author=Jefferson, T.A., Webber, M.A. & Pitman, R.L.|pages=74–78|year=2008|isbn=978-0-12-383853-7|publisher=Elsevier|location=London}}</ref> The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw.<ref name="Jefferson" /> The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to {{convert|1|kg|lb}} each.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://acsonline.org/factpack/spermwhl.htm |archiveurl= http://web.archive.org/web/20100613015956/http://acsonline.org/factpack/spermwhl.htm |archivedate= 2010-06-13 |title=Sper Wale '' Physeter macrocephalus'' |work=American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet }}</ref> The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.whale-images.com/sperm_whale_facts.jsp|title=Sperm Whale Facts|work=whale-images.com}}</ref> Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth.<ref>], p. 4</ref> Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age; analogous to rings in a tree, the teeth build distinct layers of cementum and dentine as they grow.<ref>], p. 8</ref> | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| === |

===Skeleton=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Sperm whales are believed to be able remain submerged for 90 minutes<ref name="encyc"/> and to dive as deep as {{convert|2250|m|ft}}, making them the second deepest diving mammal after ], which has been recorded at {{convert|2992|m|ft}}.<ref name=NatGeoDeepest/> More typical sperm whale dives are around {{convert|400|m|ft}} and 35 minutes in duration.<ref name="encyc" /> At these great depths, sperm whales had sometimes become entangled in ] and drowned<ref>The Southwestern Company (1987): "The Volume Library 1", p. 65, ISBN 0-87197-208-5</ref> until improvements in laying and maintenance techniques were employed.<ref>Carter, L., Burnett, D., Drew, S., Marle, G., Hagadorn, L., Bartlett-McNeil D., & Irvine N. (December 2009). , UNEP-WCMC, p. 31, ISBN 978-0-9563387-2-3</ref> | |||

| The ribs are bound to the spine by flexible cartilage, which allows the ribcage to collapse rather than snap under high pressure.<ref>. Oceanservice.noaa.gov (11 January 2013). Retrieved 2013-03-19.</ref> While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long-term effects. Bones show the same ] that signals ] in humans. Older skeletons showed the most extensive damage, whereas calves showed no damage. This damage may indicate that sperm whales are susceptible to decompression sickness, and sudden surfacing could be lethal to them.<ref name="bends">{{cite journal |vauthors=Moore MJ, Early GA | title=Cumulative sperm whale bone damage and the bends | journal=] | volume=306 | issue=5705 | year=2004 | page=2215 | pmid=15618509 | doi=10.1126/science.1105452| s2cid=39673774 }}</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale has adapted to cope with drastic pressure changes when diving. The flexible ] allows lung collapse, reducing ] intake, and ] can decrease to conserve ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Physiological Basis of Diving to Depth: Birds and Mammals|author=Kooyman, G. L.& Ponganis, P. J.|journal=Annual Review of Physiology|volume=60|issue=1|date=October 1998|pages=19–32|doi=10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.19|pmid=9558452}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Extreme diving of beaked whales|author=Tyack, P., Johnson, M., Aguilar Soto, N., Sturlese, A. & Madsen, P.|journal=Journal of Experimental Biology|volume=209|issue=Pt 21|pages=4238–4253|date=18 October 2006|url=http://jeb.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/209/21/4238|doi=10.1242/jeb.02505|pmid=17050839}}</ref> ], which stores oxygen in muscle tissue, is much more abundant than in terrestrial animals.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Body size and skeletal muscle myoglobin of cetaceans: adaptations for maximizing dive duration|author=Noren, S. R. & Williams, T. M.|journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology – Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology|volume=126|issue=2|date=June 2000|pages=181–191|doi=10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00182-3|pmid=10936758}}</ref> The ] has a high ] density, which contain oxygen-carrying ]. The oxygenated blood can be directed towards only the brain and other essential organs when oxygen levels deplete.<ref>Marshall, C. "Morphology, Functional; Diving Adaptations of the Cardiovascular System", p. 770 in ]</ref><ref name="aquarium">{{cite web|title=Aquarium of the Pacific – Sperm Whale|url=http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/print/sperm_whale/|publisher=Aquarium of the Pacific|accessdate=2008-11-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Scientists conduct first simultaneous tagging study of deep-diving predator, prey|last=Shwartz|first=Mark|publisher=Stanford Report|date=8 March 2007|url=http://news-service.stanford.edu/news/2007/march14/squid-031407.html|accessdate=6 November 2008}}</ref> The spermaceti organ may also play a role by adjusting ] (see ]).<ref name="clarke">{{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0025315400024371|title=Structure and Proportions of the Spermaceti Organ in the Sperm Whale|url=http://sabella.mba.ac.uk/2028/01/Structure_and_proportions_of_the_spermaceti_organ_in_the_sperm_whale.pdf|author=Clarke, M.|journal=Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom|volume=58|pages=1–17|year=1978|accessdate=2008-11-05}}</ref> | |||

| Like that of all cetaceans, the spine of the sperm whale has reduced ]s, of which the remnants are modified and are positioned higher on the vertebral dorsal spinous process, hugging it laterally, to prevent extensive lateral bending and facilitate more dorso-ventral bending. These evolutionary modifications make the spine more flexible but weaker than the spines of terrestrial vertebrates.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XbyxI-d5idcC&q=why+is+a+cetacean+backbone+flexible&pg=PA45|title=An Introduction to Marine Mammal Biology and Conservation|isbn=9780763783440|last1=Parsons|first1=Edward C. M.|last2=Parsons|first2=ECM|last3=Bauer|first3=A.|last4=Simmonds|first4=M. P.|last5=Wright|first5=A. J.|last6=McCafferty|first6=D.|year=2013|publisher=Jones & Bartlett Publishers }}</ref> | |||

| While sperm whales are well adapted to diving, repeated dives to great depths have long term effects. Bones show the same pitting that signals ] in humans. Older skeletons showed the most extensive pitting, whereas calves showed no damage. This damage may indicate that sperm whales are susceptible to decompression sickness, and sudden surfacing could be lethal to them.<ref name="bends">{{cite journal | author=Moore MJ, Early GA | title=Cumulative sperm whale bone damage and the bends | journal=] | volume=306 | issue=5705 | year=2004 | page=2215 | pmid=15618509 | doi=10.1126/science.1105452}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Between dives, the sperm whale surfaces to breathe for about eight minutes before diving again.<ref name="encyc" /> Odontoceti (toothed whales) breathe air at the surface through a single, S-shaped blowhole. Sperm whales spout (breathe) 3–5 times per minute at rest, increasing to 6–7 times per minute after a dive. The blow is a noisy, single stream that rises up to {{convert|2|m|ft}} or more above the surface and points forward and left at a 45° angle.<ref>Cawardine, Mark (2002) ''Sharks and Whales', Five Mile Press, p. 333, ISBN 1-86503-885-7</ref> On average, females and juveniles blow every 12.5 seconds before dives, while large males blow every 17.5 seconds before dives.<ref name="whiteheadforaging">], pp. 156–161</ref> | |||

| Like many cetaceans, the sperm whale has a vestigial pelvis that is not connected to the spine.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| A sperm whale killed {{convert|160|km|abbr=on|-1}} south of Durban, South Africa after a 1 hour, 50-minute dive was found with two dogfish (] sp.), usually found at the ], in its belly.<ref>Ommanney, F. 1971. ''Lost Leviathan''. London.</ref> | |||

| Like that of other ]s, the skull of the sperm whale is asymmetrical so as to aid ]. Sound waves that strike the whale from different directions will not be channeled in the same way.<ref>. Io9.com. Retrieved 2013-03-19.</ref> Within the basin of the cranium, the openings of the bony narial tubes (from which the nasal passages spring) are skewed towards the left side of the skull.{{citation needed|date=March 2022}} | |||

| ===Brain and senses=== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | footer = The sperm whale's brain is the largest in the world, five times heavier than a human's. | |||

| | image1 = Preserved sperm whale brain.jpg | |||

| }} | |||

| The ] is the ] known of any modern or extinct animal, weighing on average about {{convert|7.8|kg|lb}},<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/spermwhale.htm|title=Sperm Whales (''Physeter macrocephalus'')|publisher=U.S. Department of Commerce ] Office of Protected Resources|accessdate=2008-11-07}}</ref><ref name="brain">{{cite journal|title=Cetacean Brain Evolution Multiplication Generates Complexity|author=Marino, L.|journal=International Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=17|pages=3–4|year=2004|url=http://www.dauphinlibre.be/CetaceanBrainEvolutionIJCP.pdf}}</ref> more than five times heavier than a ], and has a volume of about 8,000 cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref>Fields, R. Douglas (2008-01-15) Scientific American.</ref> Although larger brains generally correlate with higher intelligence, it is not the only factor. Elephants and dolphins also have larger brains than humans.<ref name=Whitehead323>], p. 323</ref> The sperm whale has a lower ] than many other whale and ] species, lower than that of non-human ]s, and much lower than ]s'.<ref name="brain"/><ref>{{cite news|title=Intelligence Evolved|newspaper=Scientific American Mind|last=Dicke|first=U.|coauthors=Roth, G.|pages=71–77|date=August–September 2008|doi=10.1038/scientificamericanmind0808-70}}</ref> | |||

| ===Jaws and teeth {{anchor|Teeth}} === | |||

| The sperm whale's cerebrum is the largest in all mammalia, both in absolute and relative terms. The olfactory system is reduced, suggesting that the sperm whale has a poor sense of taste and smell. By contrast, the auditory system is enlarged. The ] is poorly developed, reflecting the reduction of its limbs.<ref name="OelschlagerKemp1999">{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980921)399:2<210::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-3|title=Ontogenesis of the sperm whale brain|year=1998|last1=Oelschläger|first1=Helmut H.A.|last2=Kemp|first2=Birgit|journal=The Journal of Comparative Neurology|volume=399|issue=2|pages=210–28|pmid=9721904|url=http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/%28SICI%291096-9861%2819980921%29399:2%3C210::AID-CNE5%3E3.0.CO;2-3/abstract}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The sperm whale's lower jaw is very narrow and underslung.<ref name="Jefferson">{{cite book|title=Marine Mammals of the World: a comprehensive guide to their identification|author=Jefferson, T.A.|author2=Webber, M.A.|author3=Pitman, R.L.|name-list-style=amp|pages=74–78|year=2008|isbn=978-0-12-383853-7|publisher=Elsevier|location=London}}</ref> The sperm whale has 18 to 26 teeth on each side of its lower jaw which fit into sockets in the upper jaw.<ref name="Jefferson" /> The teeth are cone-shaped and weigh up to {{convert|1|kg|lb}} each.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://acsonline.org/factpack/spermwhl.htm |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100613015956/http://acsonline.org/factpack/spermwhl.htm |archive-date= 2010-06-13 |title=Sperm Wale ''Physeter macrocephalus'' |work=American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet }}</ref> The teeth are functional, but do not appear to be necessary for capturing or eating squid, as well-fed animals have been found without teeth or even with deformed jaws. One hypothesis is that the teeth are used in aggression between males.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.whale-images.com/sperm_whale_facts.jsp|title=Sperm Whale Facts|work=whale-images.com|access-date=27 December 2007|archive-date=15 January 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100115172852/http://www.whale-images.com/sperm_whale_facts.jsp|url-status=dead}}</ref> Mature males often show scars which seem to be caused by the teeth{{citation needed|date=November 2023}}. Rudimentary teeth are also present in the upper jaw, but these rarely emerge into the mouth.<ref>], p. 4</ref> Analyzing the teeth is the preferred method for determining a whale's age. Like the age-rings in a tree, the teeth build distinct layers of ] and ] as they grow.<ref>], p. 8</ref> | |||

| === |

===Brain=== | ||

| ] | |||

| Sperm whales have 21 pairs of chromosomes (]).<ref name="Arnason1981">{{cite doi|10.1111/j.1601-5223.1981.tb01418.x}}</ref> The genome of live whales can be examined by recovering shed skin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.seaswap.info/study/genetics.html |title=SEASWAP: Genetic Sampling |publisher=Seaswap.info|accessdate=2013-07-23}}</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale ] is the ] known of any modern or extinct animal, weighing on average about {{convert|7.8|kg|lb}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/species/mammals/cetaceans/spermwhale.htm|title=Sperm Whales (''Physeter macrocephalus'')|publisher=U.S. Department of Commerce ] Office of Protected Resources|access-date=2008-11-07}}</ref><ref name="brain">{{cite journal|title=Cetacean Brain Evolution Multiplication Generates Complexity|author=Marino, L.|journal=International Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=17|pages=3–4|year=2004|doi=10.46867/IJCP.2004.17.01.06 |url=http://www.dauphinlibre.be/CetaceanBrainEvolutionIJCP.pdf|access-date=10 August 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121120201827/http://www.dauphinlibre.be/CetaceanBrainEvolutionIJCP.pdf|archive-date=20 November 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> (with the smallest known weighing {{convert|6.4|kg|lb}} and the largest known weighing {{convert|9.2|kg|lb}}),<ref name = "Wood"/><ref name=Carwardine/> more than five times heavier than a ], and has a volume of about 8,000 cm<sup>3</sup>.<ref>Fields, R. Douglas (15 January 2008). Scientific American.</ref> Although larger brains generally correlate with higher intelligence, it is not the only factor. Elephants and dolphins also have larger brains than humans.<ref name=Whitehead323>], p. 323</ref> The sperm whale has a lower ] than many other whale and ] species, lower than that of non-human ]s, and much lower than that of humans.<ref name="brain"/><ref>{{cite news|title=Intelligence Evolved|newspaper=Scientific American Mind|last=Dicke|first=U.|author2=Roth, G. |pages=71–77|date=August–September 2008| volume=19 | issue=4 |doi=10.1038/scientificamericanmind0808-70}}</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale's ] is the largest in all mammalia, both in absolute and relative terms. The ] is reduced, suggesting that the sperm whale has a poor sense of taste and smell. By contrast, the auditory system is enlarged. The ] is poorly developed, reflecting the reduction of its limbs.<ref name="OelschlagerKemp1999">{{cite journal|doi=10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19980921)399:2<210::AID-CNE5>3.0.CO;2-3|title=Ontogenesis of the sperm whale brain|year=1998|last1=Oelschläger|first1=Helmut H.A.|last2=Kemp|first2=Birgit|journal=The Journal of Comparative Neurology|volume=399|issue=2|pages=210–28|pmid=9721904|s2cid=23821591 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Digestive tract=== | |||

| The sperm whale has the longest intestinal system in the world,<ref>Inside Natures Giants: The Sperm Whale. Channel 4</ref> exceeding 300 m in larger specimens.<ref name="chip.choate.edu"/><ref>Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988). ''.'' Brill Archive, p. 62, ISBN 0-935848-47-9</ref> | |||

| ===Biological systems=== | |||

| The sperm whale has four stomachs. The first secretes no gastric juices and has very thick muscular walls to crush the food (since whales can't chew) and resist the claw and sucker attacks of swallowed squid. The second stomach is larger and is where digestion proper takes place. Undigested squid beaks accumulate in the second stomach – as many as 18,000 have been found in some dissected specimens.<ref name="chip.choate.edu">{{cite web|url=http://chip.choate.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/Science/rgritzer/webpages/BI465/Student%20project/Fran%20final%20project/whale_digestion.htm |title=Whale Digestion |publisher=Chip.choate.edu |accessdate=2013-07-23}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|author=Name (required) |url=http://nikolaus6.wordpress.com/20000-leagues-under-the-sea-index/20000-leagues-under-the-sea-part2-ch12/ |title="20000 Leagues Under the Sea" Part2 Ch12 | Nikolaus6's Weblog |publisher=Nikolaus6.wordpress.com |accessdate=2013-07-23}}</ref><ref name="youtube1"></ref> | |||

| {{See also|Physiology of underwater diving#Marine mammals}} | |||

| The sperm whale respiratory system has adapted to cope with drastic pressure changes when diving. The flexible ] allows lung collapse, reducing ] intake, and ] can decrease to conserve ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Physiological Basis of Diving to Depth: Birds and Mammals|author1=Kooyman, G. L. |author2=Ponganis, P. J. |name-list-style=amp |journal=Annual Review of Physiology|volume=60|issue=1|date=October 1998|pages=19–32|doi=10.1146/annurev.physiol.60.1.19|pmid=9558452}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|title=Extreme diving of beaked whales|author=Tyack, P.|author2=Johnson, M.|author3=Aguilar Soto, N.|author4=Sturlese, A.|author5=Madsen, P.|name-list-style=amp|journal=Journal of Experimental Biology|volume=209|issue=Pt 21|pages=4238–4253|date=18 October 2006|doi=10.1242/jeb.02505|pmid=17050839|doi-access=free}}</ref> Between dives, the sperm whale surfaces to breathe for about eight minutes before diving again.<ref name="encyc" /> ] (toothed whales) breathe air at the surface through a single, S-shaped blowhole, which is extremely skewed to the left. Sperm whales spout (breathe) 3–5 times per minute at rest, increasing to 6–7 times per minute after a dive. The blow is a noisy, single stream that rises up to {{convert|2|m|ft}} or more above the surface and points forward and left at a 45° angle.<ref>Cawardine, Mark (2002) ''Sharks and Whales'', Five Mile Press, p. 333, {{ISBN|1-86503-885-7}}</ref> On average, females and juveniles blow every 12.5 seconds before dives, while large males blow every 17.5 seconds before dives.<ref name="whiteheadforaging">], pp. 156–161</ref> A sperm whale killed {{convert|160|km|abbr=on|-1}} south of Durban, South Africa, after a 1-hour, 50-minute dive was found with two dogfish (] sp.), usually found at the ], in its belly.<ref>Ommanney, F. 1971. ''Lost Leviathan''. London.</ref> | |||

| The sperm whale has the longest intestinal system in the world,<ref>Inside Natures Giants: The Sperm Whale. Channel 4</ref> exceeding 300 m in larger specimens.<ref name="chip.choate.edu"/><ref>Tinker, Spencer Wilkie (1988). ''.'' Brill Archive, p. 62, {{ISBN|0-935848-47-9}}</ref> The sperm whale has a four-chambered stomach that is similar to ]s. The first secretes no gastric juices and has very thick muscular walls to crush the food (since whales cannot chew) and resist the claw and sucker attacks of swallowed squid. The second chamber is larger and is where digestion takes place. Undigested squid beaks accumulate in the second chamber – as many as 18,000 have been found in some dissected specimens.<ref name="chip.choate.edu">{{cite web|url=http://chip.choate.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/Science/rgritzer/webpages/BI465/Student%20project/Fran%20final%20project/whale_digestion.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131023060152/http://chip.choate.edu/bbcswebdav/institution/Science/rgritzer/webpages/BI465/Student%20project/Fran%20final%20project/whale_digestion.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=2013-10-23 |title=Whale Digestion |publisher=Chip.choate.edu |access-date=2013-07-23}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://nikolaus6.wordpress.com/20000-leagues-under-the-sea-index/20000-leagues-under-the-sea-part2-ch12/ |title=20000 Leagues Under the Sea Part2 Ch12 | Nikolaus6's Weblog |publisher=Nikolaus6.wordpress.com |access-date=2013-07-23|date=18 July 2008 }}</ref><ref name="youtube1">Archived at {{cbignore}} and the {{cbignore}}: {{cite AV media|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ChivtjDjh4|title=Professor Malcolm Clarke – discusses the anatomy of sperm whales|date=25 April 2011|via=YouTube}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Most squid beaks are vomited by the whale, but some occasionally make it to the hindgut. Such beaks precipitate the formation of ].<ref name="youtube1"/> | |||

| Most squid beaks are vomited by the whale, but some occasionally make it to the hindgut. Such beaks precipitate the formation of ambergris.<ref name="youtube1"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Circulatory system=== | |||

| In 1959, the heart of a 22 metric-ton (24 short-ton) male taken by whalers was measured to be {{convert|116|kg|lbs}}, about 0.5% of its total mass.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Race | first1 = George J. | last2 = Edwards | first2 = W. L. Jack | last3 = Halden | first3 = E. R. | last4 = Wilson | first4 = Hugh E. | last5 = Luibel | first5 = Francis J. | year = 1959 | title = A Large Whale Heart | journal = Circulation | volume = 19 | issue = 6| pages = 928–932 | doi=10.1161/01.cir.19.6.928| pmid = 13663185 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The circulatory system has a number of specific adaptations for the aquatic environment. The diameter of the ] increases as it leaves the heart. This bulbous expansion acts as a ], ensuring a steady blood flow as the heart rate slows during diving.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Shadwick RE, Gosline JM |title=Arterial Windkessels in marine mammals |journal=Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology |volume=49 |pages=243–52 |year=1995 |pmid=8571227}}</ref> The arteries that leave the aortic arch are positioned symmetrically. There is no ]. There is no direct connection between the internal carotid artery and the vessels of the brain.<ref name=pmid9329202>{{cite journal |author=Melnikov VV |title=The arterial system of the sperm whale (''Physeter macrocephalus'') |journal=Journal of Morphology |volume=234 |issue=1 |pages=37–50 |date=October 1997 |pmid=9329202 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199710)234:1<37::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-K|s2cid=35438320 }}</ref> Their circulatory system has adapted to dive at great depths, as much as {{convert|2250|m|ft|0}}<ref name=plosone-2014>{{cite journal |author1=Gregory S. Schorr |author2=Erin A. Falcone |author3=David J. Moretti |author4=Russel D. Andrews |year=2014 |title=First long-term behavioral records from Cuvier's beaked whales (''Ziphius cavirostris'') reveal record-breaking dives |journal=] |volume=9 |issue=3 |page=e92633 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0092633 |pmid=24670984 |ref=Schorr |pmc=3966784|bibcode=2014PLoSO...992633S |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=Elephantseal>{{cite web |url= http://www.coml.org/comlfiles/press/CoML_Beyond_Sunlight_11.17.2009_Public.pdf |title= Census of Marine Life – From the Edge of Darkness to the Black Abyss |publisher=Coml.org |access-date=2009-12-15}}</ref><ref name=NatGeoDeepest>{{cite magazine |title=Elusive Whales Set New Record for Depth and Length of Dives Among Mammals |url=http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140326-cuvier-beaked-whale-record-dive-depth-ocean-animal-science/ |author=Lee, Jane J. |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20140329065822/http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/03/140326-cuvier-beaked-whale-record-dive-depth-ocean-animal-science |date=2014-03-26 |archive-date=2014-03-29 |url-status=dead |magazine=National Geographic }}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-science-whale-idINBREA2P24S20140326|title=How low can you go? This whale is the champion of deep diving|first=Will|last=Dunham|newspaper=Reuters|date=26 March 2014|via=www.reuters.com}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.theglobeandmail.com/technology/science/meet-cuviers-beaked-whale-the-deep-diving-champion-of-the-mammal-world/article17691691/|title=The Globe and Mail|website=]|access-date=18 February 2020|archive-date=25 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140625012625/http://www.theglobeandmail.com/technology/science/meet-cuviers-beaked-whale-the-deep-diving-champion-of-the-mammal-world/article17691691/|url-status=dead}}</ref>{{Citation overkill|date=June 2022}} for up to 120 minutes.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qGdLaAcSS-EC&q=sperm+whale+120+minutes&pg=PA274|title=Seals as divers|journal=New Scientist|first=R. J.|last=Harrison|date=10 May 1962|publisher=Reed Business Information|volume=14|number=286}}{{Dead link|date=March 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> More typical dives are around {{convert|400|m|ft|-1}} and 35 minutes in duration.<ref name="encyc" /> ], which stores oxygen in muscle tissue, is much more abundant than in terrestrial animals.<ref>{{cite journal|title=Body size and skeletal muscle myoglobin of cetaceans: adaptations for maximizing dive duration|author1=Noren, S. R. |author2=Williams, T. M. |name-list-style=amp |journal=Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology – Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology|volume=126|issue=2|date=June 2000|pages=181–191|doi=10.1016/S1095-6433(00)00182-3|pmid=10936758}}</ref> The ] has a high density of ]s, which contain oxygen-carrying ]. The oxygenated blood can be directed towards only the brain and other essential organs when oxygen levels deplete.<ref>Marshall, C. "Morphology, Functional; Diving Adaptations of the Cardiovascular System", p. 770 in ]</ref><ref name="aquarium">{{cite web|title=Aquarium of the Pacific – Sperm Whale|url=http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/print/sperm_whale/|publisher=Aquarium of the Pacific|access-date=2008-11-06|archive-date=14 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190314155801/http://www.aquariumofpacific.org/onlinelearningcenter/print/sperm_whale|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Scientists conduct first simultaneous tagging study of deep-diving predator, prey|last=Shwartz|first=Mark|publisher=Stanford Report|date=8 March 2007|url=http://news-service.stanford.edu/news/2007/march14/squid-031407.html|access-date=6 November 2008}}</ref> The ] may also play a role by adjusting ] (see ]).<ref name="clarke">{{cite journal|doi=10.1017/S0025315400024371|title=Structure and Proportions of the Spermaceti Organ in the Sperm Whale|url=http://sabella.mba.ac.uk/2028/01/Structure_and_proportions_of_the_spermaceti_organ_in_the_sperm_whale.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081217073258/http://sabella.mba.ac.uk/2028/01/Structure_and_proportions_of_the_spermaceti_organ_in_the_sperm_whale.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=2008-12-17|author=Clarke, M.|journal=Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom|volume=58|pages=1–17|year=1978|access-date=2008-11-05|issue=1|bibcode=1978JMBUK..58....1C |s2cid=17892285 }}</ref> The arterial ] are extraordinarily well-developed. The complex arterial retia mirabilia of the sperm whale are more extensive and larger than those of any other cetacean.<ref name=pmid9329202/> | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1959, the heart of a 22-tonne male slain by whalers was measured to be 116 kg (255 lbs), about 0.5% of its total mass.<ref>George J. Race, W. L. Jack Edwards, E. R. Halden, Hugh E. Wilson, and Francis J. Luibel, (1959). ''''. ''Circulation'', 1959;19:928–932</ref> | |||

| ===Senses=== | |||

| The circulatory system has a number of specific adaptations for the aquatic environment. The diameter of the ] increases as it leaves the heart. This bulbous expansion acts as a ], ensuring a steady blood flow as the heart rate slows during diving.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Shadwick RE, Gosline JM |title=Arterial Windkessels in marine mammals |journal=Symposia of the Society for Experimental Biology |volume=49 |issue= |pages=243–52 |year=1995 |pmid=8571227}}</ref> The arteries that leave the aortic arch are positioned symmetrically. There is no ]. There is no direct connection between the internal carotid artery and the vessels of the brain.<ref name=pmid9329202>{{cite journal |author=Melnikov VV |title=The arterial system of the sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) |journal=Journal of Morphology |volume=234 |issue=1 |pages=37–50 |date=October 1997 |pmid=9329202 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199710)234:1<37::AID-JMOR4>3.0.CO;2-K}}</ref> | |||

| The arterial ] are extraodinarily well-developed. The complex arterial retia mirabilia of the sperm whale are more extensive and larger than those of any other cetacean.<ref name=pmid9329202/> | |||

| ===Eyes=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The sperm whale's eye does not differ greatly from those of other ]s except in size. It is the largest among the toothed whales, weighing about 170 g. It is overall ellipsoid in shape, compressed along the visual axis, measuring about 7×7×3 cm. The ] is elliptical and the lens is spherical. The ] is very hard and thick, roughly 1 cm anteriorly and 3 cm posteriorly. There are no ]s. The ] is very thick and contains a fibrous '']''. Like other toothed whales, the sperm whale can retract and protrude its eyes thanks to a 2-cm-thick retractor muscle attached around the eye at the equator.<ref name=Bjerager2003>{{cite journal|author=Bjerager, P.; Heegaard, S. and Tougaar, J. |title=Anatomy of the eye of the sperm whale (''Physeter macrocephalus L.'')|doi=10.1578/016754203101024059|year=2003|journal=Aquatic Mammals|volume=29|page=31 }}</ref> | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ===Spermaceti organ and melon=== | ====Spermaceti organ and melon==== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

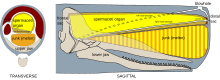

| Atop the whale's skull is positioned a large complex of organs filled with a liquid mixture of fats and waxes called ]. The purpose of this complex is to generate powerful and focused clicking sounds, which |

Atop the whale's skull is positioned a large complex of organs filled with a liquid mixture of fats and waxes called ]. The purpose of this complex is to generate powerful and focused clicking sounds, the existence of which was proven by ] and William Schevill when a recording was produced on a research vessel in May 1959.<ref name="Worthington-1957">{{cite journal |last1=Worthington |first1=L. V. |last2=Schevill |first2=William E. |title=Underwater Sounds heard from Sperm Whales |journal=Nature |date=August 1957 |volume=180 |issue=4580 |pages=291 |doi=10.1038/180291a0 |bibcode=1957Natur.180..291W |s2cid=4173897 |doi-access=free }}</ref> The sperm whale uses these sounds for ] and communication.<ref name="Cranford2000ImpulseSoundSources">{{cite book|author=Cranford, T.W.|year=2000|chapter=In Search of Impulse Sound Sources in Odontocetes|title=Hearing by Whales and Dolphins (Springer Handbook of Auditory Research series)|editor=Au, W.W.L |editor2=Popper, A.N. |editor3=Fay, R.R.|publisher=Springer-Verlag, New York|isbn=978-0-387-94906-2}}</ref><ref name="Norris, K.S. & Harvey, G.W. 1972 397–417">{{cite book|author1=Norris, K.S. |author2=Harvey, G.W. |name-list-style=amp |year=1972|chapter=A theory for the function of the spermaceti organ of the sperm whale|title=Animal orientation and navigation|editor=Galler, S.R |editor2=Schmidt-Koenig, K |editor3=Jacobs, G.J. |editor4=Belleville, R.E.|publisher=NASA, Washington, D.C.|pages=397–417|chapter-url= https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=19720017437 }}</ref><ref name="Cranford, T.W. 1999 1133–1157">{{cite journal| author=Cranford, T.W.| title=The Sperm Whale's Nose: Sexual Selection on a Grand Scale?| journal=Marine Mammal Science | volume=15| issue=4| pages=1133–1157 | year=1999 | doi=10.1111/j.1748-7692.1999.tb00882.x| bibcode=1999MMamS..15.1133C}}</ref><ref name="Madsen, P.T., Payne, R., Kristiansen, N.U., Wahlberg, M., Kerr, I. & Møhl, B. 2002 1899–1906">{{cite journal| author=Madsen, P.T.| author2=Payne, R.| author3=Kristiansen, N.U.| author4=Wahlberg, M.| author5=Kerr, I.| author6=Møhl, B.| name-list-style=amp | title=Sperm whale sound production studied with ultrasound time/depth-recording tags | journal=Journal of Experimental Biology | volume=205| pages=1899–1906 | year=2002| pmid=12077166| issue=Pt 13| doi=10.1242/jeb.205.13.1899}}</ref><ref name="Møhl, B., Wahlberg, M., Madsen, P.T., Miller, L.A. & Surlykke, A. 2000 638–648">{{cite journal| author=Møhl, B.| author2=Wahlberg, M.| author3=Madsen, P.T.| author4=Miller, L.A.| author5=Surlykke, A.| name-list-style=amp | title=Sperm whale clicks: directionality and sound levels revisited| journal=Journal of the Acoustical Society of America | volume=107| pages=638–648 | year=2000| doi=10.1121/1.428329| pmid=10641672| issue=1|bibcode = 2000ASAJ..107..638M | s2cid=9610645}}</ref><ref name="Møhl, B., Wahlberg, M., Madsen, P.T., Heerfordt, A. & Lund, A. 2003 1143–1154">{{cite journal| author=Møhl, B.| author2=Wahlberg, M.| author3=Madsen, P.T.| author4=Heerfordt, A.| author5=Lund, A.| name-list-style=amp | title=The monopulsed nature of sperm whale clicks| journal=Journal of the Acoustical Society of America | volume=114| pages=1143–1154 | year=2003| doi=10.1121/1.1586258| pmid=12942991| issue=2|bibcode = 2003ASAJ..114.1143M }}</ref><ref name="Whitehead, H. 2003 277–279">], pp. 277–279</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author1=Stefan Huggenberger |author2=Michel Andre |author3=Helmut H. A. Oelschlager |name-list-style=amp | title=The nose of the sperm whale – overviews of functional design, structural homologies and evolution| journal=Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom |volume=96 |issue=4 |year=2014| doi=10.1017/S0025315414001118| pages=1–24|hdl=2117/97052 |s2cid=27312770 |hdl-access=free }}</ref>{{citation overkill|date=September 2021}} | ||

| The spermaceti organ is like a large barrel of spermaceti. |

The spermaceti organ is like a large barrel of spermaceti. Its surrounding wall, known as the ''case'', is extremely tough and fibrous. The case can hold within it up to 1,900 ]s of spermaceti.<ref>. . Retrieved 2013-03-19.</ref> It is proportionately larger in males.<ref name=Whitehead321>], p. 321</ref> This oil is a mixture of ]s and ]s. It has been suggested that it is homologous to the dorsal bursa organ found in dolphins. <ref name="n010">{{cite journal |last1=Cranford |first1=Ted W. |last2=Amundin |first2=Mats |last3=Norris |first3=Kenneth S. |date=1996 |title=Functional morphology and homology in the odontocete nasal complex: Implications for sound generation |journal=Journal of Morphology |volume=228 |issue=3 |pages=223–285 |doi=10.1002/(SICI)1097-4687(199606)228:3<223::AID-JMOR1>3.0.CO;2-3 |pmid=8622183 |issn=0362-2525}}</ref> The proportion of wax esters in the spermaceti organ increases with the age of the whale: 38–51% in calves, 58–87% in adult females, and 71–94% in adult males.<ref name=EncyclopediaMarineMammals1164>], p. 1164</ref> The spermaceti at the core of the organ has a higher wax content than the outer areas.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Morris, Robert J. |year=1975|title=Further studies into the lipid structure of the spermaceti organ of the sperm whale (''Physeter catodon'')|journal= Deep-Sea Research|volume= 22|pages= 483–489|doi=10.1016/0011-7471(75)90021-2|issue=7 |bibcode=1975DSRA...22..483M|doi-access=free}}</ref> The speed of sound in spermaceti is 2,684 m/s (at 40 kHz, 36 °C), making it nearly twice as fast as in the oil in a dolphin's ].<ref name=NorrisHarvey1972>{{cite book|chapter-url=https://archive.org/stream/nasa_techdoc_19720017412/19720017412#page/n419/mode/2up |author1=Norris, Kenneth S. |author2=Harvey, George W. |name-list-style=amp |year=1972|title=Animal orientation and navigation|chapter=A Theory for the Function of the Spermaceti Organ of the Sperm Whale|publisher=NASA}}</ref> | ||

| Below the spermaceti organ lies the "junk" which consists of compartments of spermaceti separated by cartilage. It is analogous to the ] found in other toothed whales.<ref name=Carrier>{{cite journal |last1=Carrier |first1=David R. |last2=Deban |first2=Stephen M. |last3=Otterstrom |first3=Jason |title=The face that sank the Essex : potential function of the spermaceti organ in aggression |journal=Journal of Experimental Biology |date=15 June 2002 |volume=205 |issue=12 |pages=1755–1763 |doi=10.1242/jeb.205.12.1755 |pmid=12042334 }}</ref> The structure of the junk redistributes physical stress across the skull and may have evolved to protect the head during ramming.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.popsci.com/science-says-sperm-whales-could-really-wreck-ships|title=Science Says Sperm Whales Could Really Wreck Ships|website=Popular Science|date=8 April 2016|access-date=2016-04-13}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Panagiotopoulou|first1=Olga|last2=Spyridis|first2=Panagiotis|last3=Abraha|first3=Hyab Mehari|last4=Carrier|first4=David R.|last5=Pataky|first5=Todd C.|title=Architecture of the sperm whale forehead facilitates ramming combat|journal=PeerJ|volume=4|doi=10.7717/peerj.1895|pmc=4824896|pmid=27069822|pages=e1895|year=2016 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name=Carrier/> | |||

| Running through the head are two air passages. The left passage runs alongside the spermaceti organ and goes directly to the blowhole, whilst the right passage runs underneath the spermaceti organ and passes air through a pair of phonic lips and into the distal sac at the very front of the nose. The distal sac is connected to the blowhole and the terminus of the left passage. When the whale is submerged, it can close the blowhole, and air that passes through the phonic lips can circulate back to the lungs. | |||