| Revision as of 02:44, 25 September 2008 editSarkar112 (talk | contribs)160 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:37, 10 January 2025 edit undoN6gik (talk | contribs)13 edits c 114 BC | ||

| (544 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Historical region located in northeastern Iran}} | |||

| {{merge|Parthian Empire|Talk:Parthian Empire#Merger proposal|date=May 2008}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{citations missing|article|date=August 2007}} | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | |||

| {{Infobox former subdivision | |||

| |native_name = ] (اشکانیان) | |||

| |_noautocat = <!-- "no" for no automatic categorization --> | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Parthian Empire | |||

| |native_name = 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 | |||

| |common_name = Parthia | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Parthia | |||

| | | |||

| |common_name = <!-- Used to resolve location within categories and name of flags and coat of arms --> | |||

| |continent = moved from Category:Asia to the Middle East | |||

| |subdivision = Historical region | |||

| |region = ], ], and ] | |||

| | |

|nation = Iran | ||

| |demonym = <!-- The name of the group of people residing there --> | |||

| |era = Classical antiquity | |||

| |status_text = <!-- A free text to describe status the top of the infobox. Use sparingly. --> | |||

| |status = Empire | |||

| <!-- Titles and names of the first and last leaders and their deputies --> | |||

| |status_text = '''Empires of Persia''' | |||

| |title_leader = <!-- Default: "King" for monarchy, otherwise leave blank for default "President" --> | |||

| |empire = Persia | |||

| |title_deputy = <!-- Default: "Prime minister" --> | |||

| |government_type = ] ] | |||

| |leader1 = <!-- Name of leader (up to six) --> | |||

| | | |||

| |year_leader1 = <!-- Years served --> | |||

| |<!--- Rise and fall, events, years and dates ---> | |||

| |deputy1 = <!-- Name of prime minister (up to six) --> | |||

| |<!-- only fill in the start/end event entry if a specific article exists. Don't just say "abolition" or "declaration"--> | |||

| |year_deputy1 = <!-- Years served --> | |||

| | | |||

| <!-- Legislature --> | |||

| |year_start = 238 BC | |||

| |legislature = <!-- Name of legislature --> | |||

| |year_end = 226 | |||

| |house1 = <!-- Name of first chamber --> | |||

| | | |||

| |house2 = <!-- Name of second chamber --> | |||

| |year_exile_start = | |||

| |type_house1 = <!-- Default: "Upper house" --> | |||

| |year_exile_end = | |||

| |type_house2 = <!-- Default: "Lower house" --> | |||

| | | |||

| <!-- General information --> | |||

| |event_start = ] | |||

| |capital = ] | |||

| |date_start = | |||

| |coordinates = <!-- Use {{Coord}} --> | |||

| |event_end = ] | |||

| |motto = <!-- Accepts wikilinks --> | |||

| |date_end = | |||

| |anthem = <!-- Accepts wikilinks --> | |||

| | | |||

| |political_subdiv = <!-- Accepts wikilinks --> | |||

| |event1 = <!--- Optional: other events between "start" and "end" ---> | |||

| |today = Iran and Turkmenistan<!-- Do NOT add flags, per MOS:INFOBOXFLAG --> | |||

| |date_event1 = | |||

| |event2 = | |||

| <!-- Rise and fall, events, years and dates --> | |||

| |date_event2 = | |||

| <!-- Only fill in the start/end event entry if a specific article exists. Don't just say "abolition" or "declaration". --> | |||

| |event3 = | |||

| |year_start = <!-- Year of establishment --> | |||

| |date_event3 = | |||

| |year_end = <!-- Year of disestablishment --> | |||

| |event4 = | |||

| |event_start = Establishment of the ] | |||

| |date_event4 = | |||

| |date_start = 247 BC | |||

| | | |||

| |event_end = Fall of the Parthian Empire | |||

| |event_pre = <!--- Optional: A crucial event that took place before before "event_start"---> | |||

| |date_end = 224 AD | |||

| |date_pre = | |||

| | |

|event1 = <!-- Optional: other events between "start" and "end" --> | ||

| |date_event1 = | |||

| |date_post = | |||

| |event2 = | |||

| | | |||

| |date_event2 = | |||

| |<!--- Flag navigation: Preceding and succeeding entities p1 to p5 and s1 to s5 ---> | |||

| |event3 = | |||

| |p1 = Seleucid Empire | |||

| |date_event3 = | |||

| |flag_p1 = Seleucid Empire 323 - 60 (BC).GIF | |||

| |event4 = | |||

| |image_p1 = ] | |||

| |date_event4 = | |||

| |p2 = | |||

| |event5 = | |||

| |flag_p2 = | |||

| |date_event5 = | |||

| |p3 = | |||

| |life_span = | |||

| |flag_p3 = | |||

| |era = <!-- Use: "Napoleonic Wars", "Cold War", etc. --> | |||

| |p4 = | |||

| |event_pre = <!-- Optional: A crucial event that took place before before "event_start" --> | |||

| |flag_p4 = | |||

| |date_pre = | |||

| |p5 = | |||

| |event_post = <!-- Optional: A crucial event that took place before after "event_end" --> | |||

| |flag_p5 = | |||

| |date_post = | |||

| |s1 = Sassanid Empire | |||

| <!-- Images --> | |||

| |flag_s1 = Sassanid empire map.PNG | |||

| |image_flag = <!-- Default: Flag of {{{common_name}}}.svg --> | |||

| |image_s1 = ] | |||

| |image_border = <!-- Default: "border"; for non-rectangular flag, type "no" --> | |||

| |s2 = | |||

| |flag_type = <!-- Displayed text for link under flag. Default "Flag" --> | |||

| |flag_s2 = | |||

| |flag = <!-- Link target under flag image. Default: Flag of {{{common_name}}} --> | |||

| |s3 = | |||

| |image_coat = <!-- Default: Coat of arms of {{{common_name}}}.svg --> | |||

| |flag_s3 = | |||

| |symbol_type = <!-- Displayed text for link under symbol. Default "Coat of arms" --> | |||

| |s4 = | |||

| |symbol = <!-- Link target under symbol image. Default: Coat of arms of {{{common_name}}} --> | |||

| |flag_s4 = | |||

| |image_map = Median Empire.jpg | |||

| |s5 = | |||

| |image_map_caption = The region of Parthia within the empire of ], c. 600 BC; from a ] illustrated by ] | |||

| |flag_s5 = | |||

| <!-- Flag navigation: Preceding and succeeding entities "p1" to "p5" and "s1" to "s8" --> | |||

| | | |||

| |p1 = <!-- Name of the article for preceding entity, numbered 1–5 --> | |||

| |image_flag = <!--- Default: Flag of {{{common_name}}}.svg ---> | |||

| | |

|flag_p1 = <!-- Default: "Flag of {{{p1}}}.svg" (size 30) --> | ||

| | |

|border_p1 = <!-- Default: "border"; for non-rectangular flag, type "no" --> | ||

| |image_p1 = <!-- Use: ] --> | |||

| | | |||

| |s1 = <!-- Name of the article for succeeding entity, numbered 1–8 --> | |||

| |image_coat = <!--- Default: Coat of arms of {{{common_name}}}.svg ---> | |||

| | |

|flag_s1 = <!-- Default: "Flag of {{{s1}}}.svg" (size 30) --> | ||

| | |

|border_s1 = <!-- Default: "border"; for non-rectangular flag, type "no" --> | ||

| |image_s1 = <!-- Use: ] --> | |||

| | | |||

| <!-- Area and population of a given year (up to 5) --> | |||

| |image_map = Parthian Empire 248 – 224 (BC).PNG|250px|center | |||

| |stat_year1 = <!-- year of the statistic, specify either area, population or both, numbered 1–5 --> | |||

| |image_map_caption = Parthia at its greatest extent under ] (123–88 BC) | |||

| |stat_area1 = <!-- area in square kilometres (w/o commas or spaces), area in square miles is calculated --> | |||

| | | |||

| |stat_pop1 = <!-- population (w/o commas or spaces), population density is calculated if area is also given --> | |||

| |image_map2 = <!-- If second map is needed - does not appear by default --> | |||

| | area_lost1 = | |||

| |image_map2_caption = | |||

| | lost_to1 = | |||

| | | |||

| | area_lost_year1 = | |||

| |capital = ] 238 BC to<br />] 139 BC to<br />] c. 129 BC | |||

| | area_gained1 = | |||

| |capital_exile = <!-- If status="Exile" --> | |||

| | gained_from1 = | |||

| |latd= |latm= |latNS= |longd= |longm= |longEW= | |||

| | area_gained_year1 = | |||

| | | |||

| <!-- Governance --> | |||

| |national_motto = | |||

| | Status = | |||

| |national_anthem = | |||

| | Government = | |||

| |common_languages = ] | |||

| | government_type = <!-- To generate categories: "Monarchy", "Republic", etc. to generate categories --> | |||

| |religion = ]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | Arms = | |||

| |currency = | |||

| | arms_caption = | |||

| | | |||

| | Civic = | |||

| |<!--- Titles and names of the first and last leaders and their deputies ---> | |||

| | civic_caption = | |||

| |leader1 = <!--- Name of king or president ---> | |||

| | HQ = | |||

| |leader2 = | |||

| | CodeName = | |||

| |leader3 = | |||

| | Code = | |||

| |leader4 = | |||

| <!-- Subdivisions --> | |||

| |year_leader1 = <!--- Years served ---> | |||

| | Divisions = | |||

| |year_leader2 = | |||

| | DivisionsNames = | |||

| |year_leader3 = | |||

| | DivisionsMap = | |||

| |year_leader4 = | |||

| | divisions_map_caption = | |||

| |title_leader = Shāhanshāh | |||

| <!-- Memberships --> | |||

| |representative1 = <!--- Name of representative of head of state (eg. colonial governor) ---> | |||

| | membership_title1 = | |||

| |representative2 = | |||

| | membership1 = | |||

| |representative3 = | |||

| | membership_title2 = | |||

| |representative4 = | |||

| | membership2 = | |||

| |year_representative1 = <!--- Years served ---> | |||

| | membership_title3 = | |||

| |year_representative2 = | |||

| | membership3 = | |||

| |year_representative3 = | |||

| | membership_title4 = | |||

| |year_representative4 = | |||

| | membership4 = | |||

| |title_representative = <!--- Default: "Governor"---> | |||

| | membership_title5 = | |||

| |deputy1 = <!--- Name of prime minister ---> | |||

| | membership5 = | |||

| |deputy2 = | |||

| |footnotes = <!-- Accepts wikilinks --> | |||

| |deputy3 = | |||

| |deputy4 = | |||

| |year_deputy1 = <!--- Years served ---> | |||

| |year_deputy2 = | |||

| |year_deputy3 = | |||

| |year_deputy4 = | |||

| |title_deputy = <!--- Default: "Prime minister" ---> | |||

| | | |||

| |<!--- Legislature ---> | |||

| |legislature = <!--- Name of legislature ---> | |||

| |house1 = <!--- Name of first chamber ---> | |||

| |type_house1 = <!--- Default: "Upper house"---> | |||

| |house2 = <!--- Name of second chamber ---> | |||

| |type_house2 = <!--- Default: "Lower house"---> | |||

| | | |||

| |<!--- Area and population of a given year ---> | |||

| |stat_year1 = <!--- year of the statistic, specify either area, population or both ---> | |||

| |stat_area1 = <!--- area in square kílometres (w/o commas or spaces), area in square miles is calculated ---> | |||

| |stat_pop1 = <!--- population (w/o commas or spaces), population density is calculated if area is also given ---> | |||

| |stat_year2 = | |||

| |stat_area2 = | |||

| |stat_pop2 = | |||

| |stat_year3 = | |||

| |stat_area3 = | |||

| |stat_pop3 = | |||

| |stat_year4 = | |||

| |stat_area4 = | |||

| |stat_pop4 = | |||

| |stat_year5 = | |||

| |stat_area5 = | |||

| |stat_pop5 = | |||

| |footnotes = <!--- Accepts wikilinks ---> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ](?), 2nd century CE.<ref>Notice of Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibit</ref>]] | |||

| '''Parthia''' ({{langx|peo|𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺}} ''Parθava''; {{langx|xpr|𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅}} ''Parθaw''; {{langx|pal|𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥}} ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern ].<!-- meaning Greater Iran in the linguistic/ethnic/academic sense--> It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the ] during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent ] under ] in the 6th century BC, and formed part of the ] ] after the ] of ]. The region later served as the political and cultural base of the ] ] people and Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the ] (247 BC – 224 AD). The ], the last state of ], also held the region and maintained the ] as part of their feudal aristocracy. | |||

| '''Parthia'''<ref>''Parthia'' derives from ] ''Parthia'', from ] ''Parthava-'', a dialectical variant of the stem ''Parsa-'', from which ] derives its name. ''Ashkanian'' appears to have come from the Sassanian chronicles, from which they entered in ]'s epic poem '']''.</ref> (]: '''اشکانیان Ashkâniân''') was an Iranian civilization situated in the northeastern part of modern Iran. | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| At the height of its power, the ] covered all of ] proper, as well as regions of the modern countries of ], ], ], eastern ], eastern ], ], ], ], ], ], the ], the coast of ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ]<ref></ref>. The Parthian empire was led by the Arsacid dynasty, which reunited and ruled over the ]ian plateau, after defeating and disposing the Hellenistic ], beginning in the late 3rd century BC, and intermittently controlled ] between 150 BC and AD 224. It was the third native dynasty of ancient Iran (after the ] and the ] dynasties). Parthia had many wars with the ]. | |||

| ] tomb, Parthian soldier circa 470 BCE]] | |||

| The name "Parthia" is a continuation from ] ''{{lang|la|Parthia}}'', from ] ''{{lang|xpr-Latn|Parthava}}'', which was the ] self-designator signifying "of the ]" who were an ] people. In context to its ], ''Parthia'' also appears as ''Parthyaea''.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| Parthia was known as '']w'' in the Middle Persian sources of the Sasanian period, and '']'' or '']'' by later Islamic authors, but mainly referred to the Parthian region in the West of Iran.<ref name=":0">{{Citation|last=Ghodrat-Dizaji|first=Mehrdad|title=Remarks on the Location of the Province of Parthia in the Sasanian Period|date=2016-08-30|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvh1dkb6.8|work=The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires|pages=42–46|publisher=Oxbow Books|doi=10.2307/j.ctvh1dkb6.8|isbn=978-1-78570-210-5|access-date=2021-02-15}}</ref> | |||

| After the ]-] ] (] called them Ashkuz)<ref></ref> had settled in Parthia and built a small independent kingdom, they rose to power under king ] (171-138 BC).<ref>George Rawlinson, ''The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World'', 2002, Gorgias Press LLC ISBN 1931956480</ref> Later, at the height of their power, Parthian influence reached as far as ] in ], the nexus of the ] ], where Parthian-inspired ceramics have been found. The power of the early Parthian empire seems to have been overestimated by some ancient historians, who could not clearly separate the powerful later empire from its more humble obscure origins. The end of this long-lived empire came in 224 AD, when the empire was loosely organized and the last king was defeated by one of the empire's vassals, the ] of the ] dynasty. | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| Relatively little is known of the Parthian (Arsacid) dynasty compared to the Achaemenid and Sassanid dynasties, given that little of their own literature has survived. Consequently Parthian history is largely derived from foreign histories, controlled by the evidence of ] and ]; even their own name for themselves is debatable due to a lack of domestic records. Several Greek authors, of whom we have fragments, including ] and ], wrote under Parthian rule. Their power was based on a combination of the guerrilla warfare of a mounted nomadic tribe, with organizational skills to build and administer a vast empire — even though it never matched in power and extent the Persian empires that preceded and followed it. Vassal kingdoms seem to have made up a large part of their territory (see ] of ]), and ] cities enjoyed a certain autonomy; their craftsmen received employment by some Parthians. | |||

| The original location of Parthia roughly corresponds to a region in northeastern ], but part is in southern ]. It was bordered by the ] mountain range in the north, and the ] desert in the south. It bordered ] on the west, ] on the north west, ] on the northeast, and ] on the east.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.livius.org/articles/place/parthia/ |title=Parthia |last=Lendering |first=Jona |author-link=Jona Lendering |date=2001 |website=Livius |publisher= |access-date=11 November 2021 |quote=}}</ref> | |||

| During Arsacid times, Parthia was united with ] as one administrative unit, and that region is therefore often (subject to context) considered a part of Parthia proper.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| ==Seleucid satrapy== | |||

| {{see main|Parthia (satrapy)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| By the early Sasanian period, Parthia was located in the central part of the Iranian plateau, neighboring ] to the south, ] to the south-west, ] to the north-west, the Alborz Mountains to the north, ] to the north-east, and ] to the east. In the late Sasanian era, Parthia came to embrace central and north-central Iran but also extended to the western parts of the plateau as well.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| Parthia was originally designated as a territory southeast of the ] encompasing the Kopet Dag mountain range in the north and Dasht-e-Kavir desert in the south. It was a ] of the ] from 550 BC when it was subdued by ] until the conquest of the ] by ] in 330 BC <ref></ref>. Following Alexander's death, the government of Parthia was given to ], at the ] in 323 BC. At the ] in 320 BC, Parthia was then given to ]. Philip in turn was then succeeded by ]. From 311 BC, Parthia then became a part of the ], being ruled by various ]s under Seleucid kingdom. | |||

| In the Islamic era, Parthia was believed to be located in central and western Iran. ] considered Parthia as encompassing the regions of ], ], Hamadan, Mah-i Nihawand and ].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Payne|first=Richard|date=2013|title=''Commutatio et Contentio: Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. In Memory of Zeev Rubin'' ed. by Henning Börm, Josef Wiesehöfer (review)|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jla.2013.0011|journal=Journal of Late Antiquity|volume=6|issue=1|pages=187–190|doi=10.1353/jla.2013.0011|s2cid=162332829 |issn=1942-1273}}</ref> The same definition is found in the works of ] and ]. ], while not using the word Parthia, considered ] to be the realm of the last Parthian king, ]<ref name=":0" /> | |||

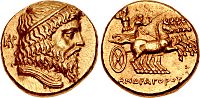

| ] (d. 238 BC) was the last ] ] of the province of Partahia, under the Seleucid rulers ] and ] (], xli. 4). Andragoras tried to wrestle independence from the Seleucid Empire, at a time when the Seleucid were embroiled in conflict with ] Egypt. In defiance, he issued coins in which he wears the royal diadem as well as his name (Will: I, 1966). Andragoras was a neighbour, a contemporary, and probably an ally of ] in ], who also fought the ] for independence around the same time, giving rise to the ].<ref>Pliny the Elder, ''Natural History'', chapters 28 and 29</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ==The Parthian Empire== | |||

| ===Under the Achaemenids=== | |||

| {{See also|Parthian Empire}} | |||

| ]'''</big>, ''P-rw-t-i-]''), as one of the 24 subjects of the Achaemenid Empire, in the Egyptian ].]] | |||

| {{See also|Seven Parthian clans}} | |||

| (from the outside). The inscription below the bow is in ].]] | |||

| As the region inhabited by Parthians, Parthia first appears as a political entity in ] lists of governorates ("satrapies") under their dominion. Prior to this, the people of the region seem to have been subjects of the ],<ref>{{harvnb|Diakonoff|1985|p=127}}.</ref> and 7th century BC Assyrian texts mention a country named Partakka or Partukka (though this "need not have coincided topographically with the later Parthia").<ref>{{harvnb|Diakonoff|1985|p=104, n.1}}.</ref> | |||

| Around the same time Andragoras seceded from the Seleucids, an ] ] tribe called the ] entered the ] from ]. They were consummate horsemen, known for the "]": turning backwards at full gallop to loose an arrow directly to the rear. Initially, about 238 BC, their king named ] (Ashk) toppled ] and established his ] independence from the ], ruling his kingdom in remote areas of northern Iran in what is today known as Turkmenistan. | |||

| A year after ]'s defeat of the Median ], Parthia became one of the first provinces to acknowledge Cyrus as their ruler, "and this allegiance secured Cyrus' eastern flanks and enabled him to conduct the first of his imperial campaigns – against ]."<ref>{{harvnb|Mallowan|1985|p=406}}.</ref> According to Greek sources, following the seizure of the Achaemenid throne by ], the Parthians united with the Median king Phraortes to revolt against him. ], the Achaemenid governor of the province (said to be father of Darius I), managed to suppress the revolt, which seems to have occurred around 522–521 BC.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| :"He (Arsaces) was used to a life of pillage and theft, when he heard about the defeat of ] against the ]s. Relieved from his fear of the king, he attacked the Parthians with a band of thieves, vanquished their prefect Andragoras, and, after having killed him took the power over the nation" . | |||

| The first indigenous Iranian mention of Parthia is in the ] of ], where Parthia is listed (in the typical Iranian clockwise order) among the governorates in the vicinity of ].<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Parthia|title=Parthia {{!}} ancient region, Iran|work=Encyclopedia Britannica|access-date=2017-09-20|language=en|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170920143141/https://www.britannica.com/place/Parthia|archive-date=2017-09-20}}</ref> The inscription dates to c. 520 BC. The center of the administration "may have been at ]".<ref>{{harvnb|Cook|1985|p=248}}.</ref> The Parthians also appear in Herodotus' list of peoples subject to the Achaemenids; the historiographer treats the Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians and Areioi as peoples of a single satrapy (the 16th),<!--Cook:252--> whose annual tribute to the king he states to be only 300 talents of silver.<!--Cook:252--> This "has rightly caused disquiet to modern scholars."<ref>{{harvnb|Cook|1985|p=252}}.</ref> | |||

| Arsaces' immediate descendants ruled free of the Seleucids until 209 BC, when King ] invaded Parthia, occupied the capital at ], and pushed forward into ]. The Parthian king ] successfully sued for peace, and recognized Seleucid authority. Antiochus III had so well secured Parthia that he moved further east, where he fought the ] king ] for three years and then went into ]. | |||

| At the ] in 331 BC between the forces of Darius III and those of ], one such Parthian unit was commanded by ], who was at the time Achaemenid governor of Parthia. Following the defeat of Darius III, Phrataphernes surrendered his governorate to Alexander when the Macedonian arrived there in the summer of 330 BC. Phrataphernes was reappointed governor by Alexander.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

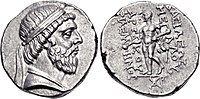

| ] (ruled 171–138 BC) from the mint at ]. The reverse shows a naked ] holding a cup, lion's skin and club. The ] inscription reads ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ ΦΙΛΕΛΛΗΝΟΣ (great king Arsaces, friend of the ]). The date ΓΟΡ is the year 173 of the ], corresponding to 140–139 BC.]] | |||

| ===Under the Seleucids=== | |||

| It was not until well into the 2nd century BC that the Parthians were able to profit from the continuing decline of the Seleucid Empire. King ] defeated King ] of the ] and annexed Bactria's territory west of the ] (the regions of ] and ]) and gained ]. This choked off the movement of trade along the ] to China, and effectively doomed the eastern ] world of Greco-Bactria and the ]. | |||

| Following the death of Alexander, in the ] in 323 BC, Parthia became a ] governorate under ]. Phrataphernes, the former governor, became governor of ]. In 320 BC, at the ], Parthia was reassigned to ], former governor of ]. A few years later, the province was invaded by ], governor of Media Magna, who then attempted to make his brother Eudamus governor. Peithon and Eudamus were driven back, and Parthia remained a governorate in its own right.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| In 316 BC, Stasander, a vassal of ] and governor of ] (and, it seems, also of ] and ]) was appointed governor of Parthia. For the next 60 years, various Seleucids would be appointed governors of the province.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| The Seleucid monarchs attempted to hold the line against Parthian expansion; ] spent his last years on a campaign against the newly emerging Iranian states. After his death in 164 BC, the Parthians took advantage of the ensuing dynastic squabbles to make even greater gains. | |||

| ], the last Seleucid satrap of Parthia. He proclaimed independence around 250 BC.]] | |||

| In 139 BC, ] captured the Seleucid monarch ], holding him captive for ten years while his troops overwhelmed ] and ]. | |||

| In 247 BC, following the death of ], ] seized control of the Seleucid capital at ], and "so left the future of the Seleucid dynasty for a moment in question."<ref name="Bivar_2003">{{harvnb|Bivar|2003|loc=para. 6}}.</ref> Taking advantage of the uncertain political situation, ], the Seleucid governor of Parthia, proclaimed his independence and began minting his own coins.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| By 129 BC, the Parthians were in control of the lands east of the ] and established their winter encampment on its banks at ], a small suburb directly across the river from ], the Seleucid capital of Mesopotamia (downstream from modern ]). Because of their need of the wealth and trade provided by Seleucia, the Parthian armies limited their incursions to harassment and allowed the city to preserve its independence. In the heat of the Mesopotamian summer, the Parthian army would withdraw to the ancient Persian capitals of ] and ] (modern ]). | |||

| Meanwhile, "a man called ], of ] or Bactrian origin, elected leader of the ]",<ref name="Curtis_2007_7">{{harvnb|Curtis|2007|p=7}}.</ref> an eastern-Iranian peoples from the Tajen/Tajend River valley, south-east of the ].<ref name="Lecoq_1987_151">{{harvnb|Lecoq|1987|p=151}}.</ref> Following the secession of Parthia from the Seleucid Empire and the resultant loss of Seleucid military support, Andragoras had difficulty in maintaining his borders, and about 238 BC – under the command of "Arsaces and his brother ]"<ref name="Curtis_2007_7"/><!-- ] linkage per: --><ref name="Bivar_1983_29">{{harvnb|Bivar|1983|p=29}}.</ref> – the Parni invaded<ref name="Bickerman_1983_19">{{harvnb|Bickerman|1983|p=19}}.</ref> Parthia and seized control of Astabene (Astawa), the northern region of that territory, the administrative capital of which was Kabuchan (] in the vulgate).{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| After 130 BC the Parthians suffered numerous incursions by ] nomads (also called the ]s from ], possibly the ]), in which kings ] and ] were successively killed. Scythians again invaded Parthia around 90 BC, putting king ] on the Parthian throne. | |||

| A short while later the Parni seized the rest of Parthia from Andragoras, killing him in the process. Although an initial ] by the Seleucids under ] was not successful, the Seleucids under ] recaptured Arsacid controlled territory in 209 BC from Arsaces' (or Tiridates') successor, ]. Arsaces II sued for peace and accepted vassal status,<ref name="Bivar_1983_29"/> and it was not until Arsaces II's grandson (or grand-nephew) ], that the Arsacids/Parni would again begin to assert their independence.<ref name="Bivar_1983_31">{{harvnb|Bivar|1983|p=31}}.</ref> | |||

| ==Government== | |||

| ] | |||

| After the conquests of ], ], ] and ], the Parthians had to organize their empire. The former elites of these countries were ], and the new rulers had to adapt to their customs if they wanted their rule to last. As a result, the cities retained their ancient rights and civil administrations remained more or less undisturbed. An interesting detail is coinage: legends were written in the Greek alphabet, a practice that continued until the 2nd century AD, when local knowledge of the language was in decline and few people knew how to read or write the ]. | |||

| ===Under the Arsacids=== | |||

| ] the victor of the ], found in ] ca. 100 AD, is kept at The ], ].]] | |||

| {{main article|Parthian Empire}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ] (R. 171–138 BC). The reverse shows ], and the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΜΕΓΑΛΟΥ ΑΡΣΑΚΟΥ ΦΙΛΕΛΛΗΝΟΣ "Great King Arsaces, friend of ]".]] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ], from the Parthian royal residence and necropolis of ], 2nd century BC]] | |||

| From their base in Parthia, the ] eventually extended their dominion to include most of ]. They also quickly established several eponymous branches on the thrones of ], ], and ]. Even though the Arsacids only sporadically had their capital in Parthia, their power base was there, among the Parthian feudal families, upon whose military and financial support the Arsacids depended. In exchange for this support, these families received large tracts of land among the earliest conquered territories adjacent to Parthia, which the Parthian nobility then ruled as provincial rulers. The largest of these city-states were ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| Another source of inspiration was the ] that had once ruled the ]. Courtiers spoke Persian and used the ]; the royal court traveled from capital to capital, and the ] kings styled themselves "king of kings". It was an apt title, as in addition to his own kingdom the Parthian monarch was the overlord of some eighteen vassal kings, such as the rulers of the city state ], the kingdom of ] and the ancient kingdom of ]. | |||

| From about 105 BC onwards, the power and influence of this handful of Parthian noble families was such that they frequently opposed the monarch, and would eventually be a "contributory factor in the downfall" of the dynasty.<ref name="Schippmann 1987 p=527">{{harvnb|Schippmann|1987|p=527}}.</ref> | |||

| The empire was, overall, not very centralized. There were several languages, many people, and a number of different economic systems. The loose ties between the separate parts of the empire were a key to its survival. In the 2nd century AD, the most important capital, Ctesiphon, was captured no less than three times by the Romans (in 116, 165 and 198), but the empire survived because there were other centers of power. On the other hand, the fact that the empire was a mere conglomeration of kingdoms, provinces and city-states did at times seriously weaken the Parthian state. This was a major factor in the halt of the Parthian expansion after the conquests of ] and ]. | |||

| From about 130 BC onwards, Parthia suffered numerous incursions by various nomadic tribes, including the ], the ], and the ]. Each time, the Arsacid dynasts responded personally, doing so even when there were more severe threats from ] or ] looming on the western borders of their empire (as was the case for ]). Defending the empire against the nomads cost ] and ] their lives.<ref name="Schippmann 1987 p=527"/> | |||

| Local potentates played important roles, and the king had to respect their privileges. Several noble families had votes in the Royal council; the ] had the right to crown the Parthian king, and every aristocrat was allowed and expected to retain an army of his own. When the throne was occupied by a weak ruler, divisions among the nobility became dangerous. | |||

| The Roman ] attempted to conquer Parthia in 52 BC but was decisively defeated at the ]. ] was planning another invasion when he was assassinated in 44 BC. A long series of ] followed.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| The constituent parts of the empire were surprisingly independent. For example, they were allowed to strike their own coins, a privilege which in antiquity was very rare. As long as the local elite paid tribute to the Parthian king, there was little interference. The system worked well: towns such as Ctesiphon, Seleucia, Ecbatana, ], ], ], and Susa flourished. | |||

| Around 32 BC, civil war broke out when a certain Tiridates rebelled against ], probably with the support of the nobility that Phraates had previously persecuted. The revolt was initially successful, but failed by 25 BC.<ref>{{harvnb|Schippmann|1987|p=528}}.</ref> In 9/8, the Parthian nobility succeeded in putting their preferred king on the throne, but ] proved to have too tight a budgetary control, so he was usurped in favor of ], who seems to have been a non-Arsacid Parthian nobleman. But when Artabanus attempted to consolidate his position (at which he was successful in most instances), he failed to do so in the regions where the Parthian provincial rulers held sway.<ref>{{harvnb|Schippmann|1987|p=529}}.</ref> | |||

| Tribute was one source of royal income; another was tolls. Parthia controlled the Silk Road, the trade route between the ] and China. | |||

| By the 2nd century AD, the ] and with the nomads, and the infighting among the Parthian nobility had weakened the Arsacids to a point where they could no longer defend their subjugated territories. The empire fractured as vassalaries increasingly claimed independence or were subjugated by others, and the Arsacids were themselves finally vanquished by the ], a formerly minor vassal from southwestern Iran, in April 224.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| ==Parthian language== | |||

| {{mainarticle|Parthian language}} | |||

| '''Arsacid Pahlavi''' or more popularly known as '''Parthian''' is a now-extinct ancient Northwestern ] that originated in ] (a region in the north-eastern part of modern ], including and not limited to ], ] and southern parts of what is today known as ]). The language was the official state language of the ] (248 BC – 224 AD) and may have served as a secondary language for the ] of ] in its early years. The language was written using the ]. | |||

| == |

===Under the Sasanians=== | ||

| Parthia was likely the first region conquered by ] after his victory over ], showing the importance of the province to the founder of the ].<ref name=":0" /> Some of the Parthian nobility continued to resist Sasanian dominion for some time, but most switched their allegiance to the Sasanians very early. Several families that claimed descent from the Parthian noble families became a Sasanian institution known as the "]", five of which are "in all probability" not Parthian, but contrived genealogies "in order to emphasize the antiquity of their families."<ref name="Lukonin_1983_704">{{harvnb|Lukonin|1983|p=704}}.</ref> | |||

| ] to the West, ], 618–712 AD ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Parthia continued to hold importance throughout the 3rd century. In his ] inscription ] lists the province of Parthia in second place after Pars. The Abnun inscription describes the ] as an attack on Pars and Parthia. Considering the Romans never went further than Mesopotamia, "Pars and Parthia" may stand for the Sasanian Empire itself.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Livshits |first1=V. A. |last2=Nitkin |first2=A. B. |year=1992 |title=Some Notes on the Inscription from Naṣrābād |journal=Bulletin of the Asia Institute |series=New Series |volume=5 |pages=41–44 |jstor=24048283 |oclc=911527026}}</ref> Parthia was also the second province chosen for settlement by Roman prisoners of war after the ].<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| The Chinese explorer ], who visited the neighbouring countries of ] and ] in 126 BC, made the first known Chinese report on Parthia. In his accounts Parthia is named "Ānxī" (Chinese: 安息), a transliteration of "]", the name of the Parthian dynasty. Zhang Qian clearly identifies Parthia as an advanced urban civilization that farmed grain and grapes, made silver coins and leather goods;<ref></ref> Zhang Qian equates the level of advancement of Parthia to the cultures of ] (in ]) and ] (in Bactria). | |||

| {{Quote|Anxi is situated several thousand '']'' west of the region of the Great ] (in ]). The people are settled on the land, cultivating the fields and growing rice and wheat. They also make wine out of grapes. They have walled cities like the people of ] (]), the region contains several hundred cities of various sizes. The coins of the country are made of silver and bear the face of the king. When the king dies, the currency is immediately changed and new coins issued with the face of his successor. The people keep records by writing on horizontal strips of leather. To the west lies ] (Mesopotamia) and to the north Yancai and Lixuan]).|Zhang Qian|trans. Burton Watson,], 123,}} | |||

| ==Language and literature== | |||

| Following Zhang Qian's embassy and report, commercial relations between China, Central Asia, and Parthia flourished, as many Chinese missions were sent throughout the 1st century BC: | |||

| {{Main article|Parthian language}} | |||

| {{Quote|The largest of these embassies to foreign states numbered several hundred persons, while even the smaller parties included over 100 members... In the course of one year anywhere from five to six to over ten parties would be sent out."|Zhang Qian|trans. Burton Watson, Shiji}} | |||

| ], ], ], Parthian period, 1st–2nd century AD.]] | |||

| The Parthians spoke ], a ]. No Parthian literature survives from before the Sassanid period in its original form,<ref>{{harvnb|Boyce|1983|p=1151}}.</ref> and they seem to have written down only very little. The Parthians did, however, have a thriving ], to the extent that their word for "minstrel" (''gosan'') survives to this day in many Iranian languages and especially in ] (]), on which it exercised heavy (especially ] and vocabulary) influence.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/armenia-iv|title=ARMENIA AND IRAN iv. Iranian influences – Encyclopaedia Iranica|last=electricpulp.com|website=www.iranicaonline.org|access-date=28 April 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171117011150/http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/armenia-iv|archive-date=17 November 2017}}</ref> These professionals were evident in every facet of Parthian daily life, from cradle to grave, and they were entertainers of kings and commoners alike, proclaiming the worthiness of their patrons through association with mythical heroes and rulers.<ref>{{harvnb|Boyce|1983|p=1115}}.</ref> These Parthian heroic poems, "mainly known through Persian of the lost ] ''Xwaday-namag'', and notably through ] '']'', doubtless not yet wholly lost in the ]<!-- literal quotation, so keep spelling --> of day."<ref>{{harvnb|Boyce|1983|p=1157}}.</ref> | |||

| The Parthians were apparently very intent on maintaining good relations with China and also sent their own embassies, starting around 110 BC: | |||

| {{Quote|When the ] envoy first visited the kingdom of Anxi (Parthia), the king of Anxi dispatched a party of 20,000 horsemen to meet them on the eastern border of the kingdom... When the Han envoys set out again to return to China, the king of Anxi dispatched envoys of his own to accompany them... The emperor was delighted at this."|Zhang Qian|trans. Burton Watson, Shiji, 123}} | |||

| In Parthia itself, attested use of written Parthian is limited to the nearly three thousand ] found (in what seems to have been a ]) at ], in present-day Turkmenistan. A handful of other evidence of written Parthian has been found outside Parthia, the most important of these being the part of a land-sale document found at ] (in the ] province of ]), and more ostraca, graffiti and the fragment of a business letter found at ] in present-day ].{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| In 97 BC, the ] general ] formed direct military contacts with the Parthian Empire and establish military bases as far west as the ] with his cavalry of 70,000 men during expeditions against the ], while protecting the trade routes now known as the ]. | |||

| The Parthian Arsacids do not seem to have used Parthian until relatively late, and the language first appears on Arsacid coinage during the reign of ] (51–58 AD).<ref>{{harvnb|Boyce|1983|p=1153}}.</ref> Evidence that use of Parthian was nonetheless widespread comes from early Sassanid times; the declarations of the early ] kings were—in addition to their native ]—also inscribed in Parthian.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| Parthians also played a role in the ] from Central Asia to China. ], a Parthian nobleman and ] missionary, went to the Chinese capital ] in 148 where he established temples and became the first man to translate Buddhist scriptures into ]. | |||

| The old poems known as ] mostly come from the areas which were considered part of Parthia in the Islamic period. These poems have the characteristics of ] and may have continued the oral traditions of Parthian minstrels.<ref name=":0"/> | |||

| ==Conflicts with Rome== | |||

| {{main|Roman-Parthian Wars}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| ], ], ].]] | |||

| ] over decorated trousers, as well as a polylobed ] (]) on the right side. ] relief.]] | |||

| ==Society== | |||

| During the earlier part of the first century BC, Parthia pursued a peaceful policy of non-entanglement with the west.<ref>Arthur Keaveney examined Parthian foreign relations in two articles: "Roman treaties with Parthia, circa 95—circa 64 B.C." (''American Journal of Philology'' '''102''' (1981:195-212) and "The King and the War-Lords: Romano-Parthian Relations Circa 64-53 B.C." (''AJP'' '''103''' (1982:412-428).</ref> Parthian relations with Imperial Rome largely consisted in intermittent warfare separated by periods of stalemate truce and exchange of gifts and hostages, with Trajan's Parthian campaign as a watershed, until the recognition of Parthia as co-equal in the fourth century, followed the final stages of fierce fighting under ], and the tribute sent by ] and the humiliation of ]. No official documents in the form of official inscriptions of treaties survive; the sources are largely Roman and literary. Protocol<ref>The protocol when representatives met is investigated in J. Gagé, "L'Empereur Romain et les rois: politique et protocol," ''Revue Historique'' 1959.</ref> developed during the fourth century provided the basis on which the Eastern Empire would address the ] | |||

| ] | |||

| City-states of "some considerable size" existed in Parthia as early as the 1st millennium BC, "and not just from the time of the Achaemenids or Seleucids."<ref name="Schippmann 1987 p=532">{{harvnb|Schippmann|1987|p=532}}.</ref> However, for the most part, society was rural, and dominated by large landholders with large numbers of serfs, slaves, and other indentured labor at their disposal.<ref name="Schippmann 1987 p=532"/> Communities with free peasants also existed.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| In 53 BC, the Roman general ] invaded Parthia in search of desperately needed gold to fund Roman military campaigns. The Parthian armies included two types of ], heavily-armed and armored ]s and lightly armed but highly-mobile ]. For the Romans, who relied on heavy ], the Parthians were difficult to defeat, as both types of cavalry were much faster and more mobile than foot soldiers. Furthermore, the Parthians used strategies during warfare unfamiliar to the Romans, such as the famous "]", firing arrows backwards at the gallop. Crassus having never encountered such an army or strategic warfare before was defeated decisively at the ] by a Parthian commander called ] in the Greek and Latin sources. This was the beginning of a series of wars that were to last for almost three centuries. After the defeat Crassus was fed molten gold, a symbolic gesture for his greed. On the other hand, the Parthians found it difficult to conquer Roman eastern provinces completely. | |||

| By Arsacid times, Parthian society was divided into the four classes (limited to freemen). At the top were the kings and near family members of the king. These were followed by the lesser nobility and the general priesthood, followed by the mercantile class and lower-ranking civil servants, and with farmers and herdsmen at the bottom.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| In the years following the battle of Carrhae, the Romans were divided in ] between the adherents of ] and those of ] and hence unable to campaign against Parthia. Although Caesar was eventually victorious against Pompey and was planning a campaign against Parthia, his subsequent murder led to another Roman civil war. The Roman general ], who had supported Caesar's murderers and feared reprisals from his heirs, ] and ] (later ]), sided with the Parthians under ]. In 41 BC Parthia, led by Labienus, invaded Syria, ], and ] and attacked ] in ]. A second army intervened in ] and captured its king ] II. The spoils were immense, and put to good use: King ] invested them in building up ]. | |||

| Little is known of the Parthian economy, but agriculture must have played the most important role in it. Significant trade first occurs with the establishment of the ] (c. 114 BC), when ] became an important junction.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| In 39 BC, Antony retaliated, sending out general ] and several legions to secure the conquered territories. The Parthian King Pacorus was killed along with Labienus, and the ] again became the border between the two nations. Hoping to further avenge the death of Crassus, Antony invaded Mesopotamia in 36 BC with the ] and other units. Having cavalry in support, Antony reached Armenia but failed to make much impact and withdrew with heavy losses. | |||

| ==Parthian cities== | |||

| Antony's campaign was followed by a break in the fighting between the two empires as Rome was again embroiled in civil war. When Octavian defeated Mark Antony, he ignored the Parthians, being more interested in the west. His son-in-law and future successor ] negotiated a peace treaty with Phraates (20 BC). | |||

| ] or Mithradātkert, located on a main trade route, was one of the earliest capitals of the Parthian Empire (c. 250 BC). The city is located in the northern foothills of the Kopetdag mountains, 11 miles west of present-day city of ] (the capital of ]).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.turkmenistan.orexca.com/rus/old_nissa.shtml|title=Старая и Новая Ниса :: Исторические памятники Туркменистана|website=www.turkmenistan.orexca.com|access-date=28 April 2018|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131230233253/http://www.turkmenistan.orexca.com/rus/old_nissa.shtml|archive-date=30 December 2013}}</ref> Nisa had a "soaring two-story hall in the Hellenistic Greek style"<ref>{{cite book |first=S. Frederick |last=Starr |title=Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2013 |page=5 |isbn=978-0-691-15773-3 }}</ref> and temple complexes used by early ]. During the reign of ] (c. 171 – 138 BC) it was renamed ''Mithradatkirt'' ("fortress of Mithradates"). ] (modern-day Mary) was another Parthian city.{{Citation needed|date=January 2021}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ] fighting a lion. ].]] | |||

| * ] | |||

| At the same time, around the year 1, the Parthians became interested in the valley of the ], where they began conquering the kingdoms of ]. One of the Parthian leaders was ], king of ]; according to an old and widespread ] tradition, he was baptized by the apostle ]. While it may sound far-fetched, the story is not altogether impossible: adherents of several religions lived together in Gandara and the ], and there may have been an audience for a representative of a new ] sect. | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| War broke out again between Rome and Parthia in the 60s AD. Armenia had become a Roman vassal kingdom, but the Parthian king ] invaded and installed his own brother as king of Armenia. This was too much for the Romans, and their commander ] invaded Armenia. The result was that the Armenian king received his crown again in Rome from the emperor ]. A compromise was worked out between the two empires: in the future, the king of Armenia was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

== Citations == | ||

| {{Reflist|30em}} | |||

| {{Main article|Indo-Parthian Kingdom}} | |||

| ] (20–50), first and greatest king of the ].]] | |||

| Also during the 1st century BC, the Parthians started to make inroads into eastern territories that had been occupied by the ] and the ]. The Parthians gained control of parts of ] and extensive ] territories in modern day ], after defeating local rulers such as the ] ruler ], in the ] region. | |||

| == General and cited references == | |||

| The ruins of the ancient port city of ] are in the process of excavation, and its historical importance to ancient trade is only now being realized. Discovered there in archaeological excavations are ivory objects from east ], pieces of stone from ], and ] from ]. Sirif dates back to the Parthian era.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| |url=http://www.chnpress.com/news/?Section=2&id=5935 | |||

| * {{citation|last=Bickerman|first=Elias J.|chapter=The Seleucid Period|pages=3–20|title=Cambridge History of Iran|volume=3|year=1983|issue=1|publisher=Cambridge University Press|editor-last=Yarshater|editor-first=Ehsan}}. | |||

| |title=Foreign Experts Talk of Siraf History | |||

| * {{citation|last=Bivar|first=A.D.H.|chapter=The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids|pages=21–99|title=Cambridge History of Iran|volume=3|year=1983|issue=1|publisher=Cambridge UP|editor-last=Yarshater|editor-first=Ehsan}}. | |||

| |publisher=Cultural Heritage News Agency | |||

| * {{citation|last=Bivar|first=A.D.H.|year=2003|chapter=Gorgan v.: Pre-Islamic History|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica|volume=11|location=New York|publisher=iranica.com|chapter-url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gorgan-v}}. | |||

| |accessdate=2006-12-11 | |||

| * {{citation|last=Boyce|first=Mary|chapter=Parthian writings and literature|pages=1151–1165|title=Cambridge History of Iran|volume=3|year=1983|issue=2|publisher=Cambridge UP|editor-last=Yarshater|editor-first=Ehsan}}. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| * {{citation|last=Cook|first=J.M.|chapter=The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of their Empire|volume=2|year=1985|pages=200–291|title=Cambridge History of Iran|editor-last=Gershevitch|editor-first=Ilya|publisher=Cambridge University Press}} | |||

| * {{citation|last=Curtis|first=Vesta Sarkhosh|chapter=The Iranian Revival in the Parthian Period|pages=7–25|title=The Age of the Parthians: The Ideas of Iran|volume=2|year=2007|publisher=I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., in association with the London Middle East Institute at SOAS and the British Museum|location=London & New York|editor-last=Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh and Sarah Stewart|isbn=978-1-84511-406-0}} | |||

| Around 20 AD, Gondophares, one of the Parthian conquerors, declared his independence from the Parthian empire and established the ] in the conquered territories. | |||

| * {{citation|last=Diakonoff|first=I.M.|chapter=Media I: The Medes and their Neighbours|volume=2|year=1985|pages=36–148|title=Cambridge History of Iran|editor-last=Gershevitch|editor-first=Ilya|publisher=Cambridge University Press}}. | |||

| * {{citation|last=Lecoq|first=Pierre|year=1987|chapter=Aparna|page=151|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica|volume=2|location=New York|publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul|chapter-url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/aparna-c3k}}. | |||

| ==Decline and fall== | |||

| * {{citation|last=Lukonin|first=Vladimir G.|chapter=Political, Social and Administrative Institutions|pages=681–747|title=Cambridge History of Iran|volume=3|year=1983|issue=2|publisher=Cambridge University Press|editor-last=Yarshater|editor-first=Ehsan}}. | |||

| * {{citation|last=Mallowan|first=Max|chapter=Cyrus the Great|volume=2|year=1985|pages=392–419|title=Cambridge History of Iran|editor-last=Gershevitch|editor-first=Ilya|publisher=Cambridge University Press}}. | |||

| ] (ruled c. 105–147 AD on a ] ].]] | |||

| * Olbrycht, Marek Jan (1998), Parthia et ulteriores gentes. Die politischen Beziehungen zwischen dem arsakidischen Iran und den Nomaden der eurasischen Steppen, Munich. | |||

| ], ], 1st half of the 3rd century AD. Decoration of a funerary stela. ].]] | |||

| * Olbrycht, Marek Jan (2016), "Manpower Resources and Army Organisation in the Arsakid Empire", ''Ancient Society,'' 46, pp. 291–338 (DOI: 10.2143/AS.46.0.3167457). | |||

| <!--LEAVE IMAGES IN A ROW TO AVOID CREATION OF BLANKS--> | |||

| * {{citation|last=Schippmann|first=Klaus|year=1987|chapter=Arsacids II: The Arsacid Dynasty|pages=525–536|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica|volume=2|location=New York|publisher=Routledge & Kegan Paul}}. | |||

| The Armenian compromise served its purpose, but nothing in it covered the deposition of an Armenian king. After 110 AD, the Parthian king ] dethroned the Armenian ruler, and the Roman emperor ] decided to invade Parthia in retaliation. War broke out in 114 AD and the Parthians were severely beaten. The Romans conquered Armenia, and in the following year, Trajan marched to the south, where the Parthians were forced to evacuate their strongholds. In 116, Trajan captured Ctesiphon, and established new provinces in Assyria and ]. Later that year, he took the Parthian capital, ], deposed the Parthian King ] and put ] as a puppet ruler on the throne. | |||

| * Verstandig Andre (2001), ''Histoire de l'Empire Parthe''. Brussels, Le Cri. | |||

| * Wolski, Józef (1993), (= ''Acta Iranica'' 32), Lovanii: Peeters | |||

| Rebellions soon broke out due to the continuing loyalty of the population to Parthia. At the same time, the ] revolted and Trajan was forced to send an army to suppress them. Trajan overcame these troubles, but his successor ] gave up the territories (117). | |||

| * {{citation|last=Yarshater|first=Ehsan|chapter=Iran ii. Iranian History: An Overview|title=Encyclopaedia Iranica|year=<!-- May 2,--> 2006|volume=13|location=New York|publisher=iranica.com|chapter-url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/iran-ii1-pre-islamic-times}}. | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| Parthian weaknesses also contributed to the disaster. In the first century AD, the Parthian nobility had become more powerful due to concessions by the Parthian king granting them greater powers over the land and the peasantry. Their power now rivaled the king's, while at the same time internal divisions in the ] family had rendered them vulnerable. | |||

| ], led forward by a Roman, circa 200 AD. ], ].]] | |||

| But the end was not near, yet. In 161, king ] declared war against the Romans and reconquered Armenia. The Roman counter-offensive was slow, but in 165, Ctesiphon fell, and the Parthians were only saved by the outburst of a catastrophic epidemic (probably the ] or ]) which temporarily crippled the two empires. The Roman co-emperors ] and ] added northern Mesopotamia to their realm (partly as a vassal-kingdom), but as it was never secure enough for them to ] the region between the Euphrates and Tigris, it remained an expensive burden. | |||

| The deciding blow came thirty years later. King ] had tried to reconquer Mesopotamia during another Roman civil war (193), but was repulsed when general ] counter-attacked. Again, Ctesiphon was captured (198), and large spoils were brought to Rome. According to a modern estimate, the gold and silver were sufficient to postpone a ]an economic crisis for three or four decades, and the consequences of the looting for Parthia were dire. | |||

| Parthia, now impoverished and without any hope to recover the lost territories, was demoralized. The kings were forced to concede greater powers to the nobility, and the vassal kings began to waver in their allegiance. In 224, the Persian vassal king ] revolted. Two years later, he took Ctesiphon, and this time it meant the end of Parthia, replaced by a third Persian Empire, ruled by the ]. | |||

| <br clear=all> | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| <center> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Image:Sarbaz Nysa.jpg|A second century BC helmet with hellenistic influences protects the head of a Parthian warrior from ], capital of the Parthian homeland. | |||

| Image:Parthian Queen Bust.jpg|A bust from The ] of Queen ], wife of ]. | |||

| Image:Coin of Phraates IV of Parthia.jpg|Coin of ] (38 BC). The inscripton reads: Benefactor ], Civilized friend of ]. | |||

| Image:Pegasus iran.jpg|Parthian era Bronze plate with ] depiction ("Pegaz" in Persian). Excavated in Masjed Soleiman, ]. | |||

| Image:ParthianWaterSpoutWithFaceOfIranianMan1-2ndCenturyCE.jpg|Parthian waterspout with face of Iranian man, 1-2nd century CE. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| </center> | |||

| ==Parthian rulers== | |||

| {{History of Greater Iran}} | |||

| {{Arsacid dynasty}} | |||

| ==Notes on the text== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * | |||

| * Hill, John E. 2004. ''The Western Regions according to the Hou Hanshu.'' Draft annotated English translation. | |||

| * Hill, John E. 2004. ''The Peoples of the West from the Weilue'' 魏略 ''by Yu Huan'' 魚豢'': A Third Century Chinese Account Composed between 239 and 265 AD.'' Draft annotated English translation. | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| {{Refbegin}} | |||

| * Debevoise, N.C. ''A Political History of Parthia'', 1938. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Overtoom |first=Nikolaus |year=2020 |title=Reign of Arrows: The Rise of the Parthian Empire in the Hellenistic Middle East |publisher=] |location=Oxford |isbn=9780197680223 }} | |||

| * Lerouge, C. ''L'image des Parthes dans le monde gréco-romain. Du début du Ier siècle av. J.-C. jusqu'à la fin du Haut-Empire romain'' (Stuttgart, 2007) (Oriens et Occidens, 17). | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| == |

== External links == | ||

| {{ |

* {{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Parthia}} | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Achaemenid Provinces}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{Sassanid Provinces}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Parthian Empire}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| * in Transoxiana 6. | |||

| * | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:37, 10 January 2025

Historical region located in northeastern Iran For other uses, see Parthia (disambiguation).| Parthia𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 | |

|---|---|

| Historical region of Iran | |

The region of Parthia within the empire of Medes, c. 600 BC; from a historical atlas illustrated by William Robert Shepherd | |

| Capital | Nisa |

| History | |

| • Establishment of the Parthian Empire | 247 BC |

| • Fall of the Parthian Empire | 224 AD |

| Today part of | Iran and Turkmenistan |

Parthia (Old Persian: 𐎱𐎼𐎰𐎺 Parθava; Parthian: 𐭐𐭓𐭕𐭅 Parθaw; Middle Persian: 𐭯𐭫𐭮𐭥𐭡𐭥 Pahlaw) is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC, and formed part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire after the 4th-century BC conquests of Alexander the Great. The region later served as the political and cultural base of the Eastern Iranian Parni people and Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire (247 BC – 224 AD). The Sasanian Empire, the last state of pre-Islamic Iran, also held the region and maintained the seven Parthian clans as part of their feudal aristocracy.

Name

The name "Parthia" is a continuation from Latin Parthia, from Old Persian Parthava, which was the Parthian language self-designator signifying "of the Parthians" who were an Iranian people. In context to its Hellenistic period, Parthia also appears as Parthyaea.

Parthia was known as Pahlaw in the Middle Persian sources of the Sasanian period, and Pahla or Fahla by later Islamic authors, but mainly referred to the Parthian region in the West of Iran.

Geography

The original location of Parthia roughly corresponds to a region in northeastern Iran, but part is in southern Turkmenistan. It was bordered by the Kopet Dag mountain range in the north, and the Dasht-e Kavir desert in the south. It bordered Media on the west, Hyrcania on the north west, Margiana on the northeast, and Aria on the east.

During Arsacid times, Parthia was united with Hyrcania as one administrative unit, and that region is therefore often (subject to context) considered a part of Parthia proper.

By the early Sasanian period, Parthia was located in the central part of the Iranian plateau, neighboring Pars to the south, Khuzistan to the south-west, Media to the north-west, the Alborz Mountains to the north, Abarshahr to the north-east, and Kirman to the east. In the late Sasanian era, Parthia came to embrace central and north-central Iran but also extended to the western parts of the plateau as well.

In the Islamic era, Parthia was believed to be located in central and western Iran. Ibn al-Muqaffa considered Parthia as encompassing the regions of Isfahan, Ray, Hamadan, Mah-i Nihawand and Azerbaijan. The same definition is found in the works of al-Khawazmi and Hamza al-Isfahani. Al-Dinawari, while not using the word Parthia, considered Jibal to be the realm of the last Parthian king, Artabanus IV.

History

Under the Achaemenids

As the region inhabited by Parthians, Parthia first appears as a political entity in Achaemenid lists of governorates ("satrapies") under their dominion. Prior to this, the people of the region seem to have been subjects of the Medes, and 7th century BC Assyrian texts mention a country named Partakka or Partukka (though this "need not have coincided topographically with the later Parthia").

A year after Cyrus the Great's defeat of the Median Astyages, Parthia became one of the first provinces to acknowledge Cyrus as their ruler, "and this allegiance secured Cyrus' eastern flanks and enabled him to conduct the first of his imperial campaigns – against Sardis." According to Greek sources, following the seizure of the Achaemenid throne by Darius I, the Parthians united with the Median king Phraortes to revolt against him. Hystaspes, the Achaemenid governor of the province (said to be father of Darius I), managed to suppress the revolt, which seems to have occurred around 522–521 BC.

The first indigenous Iranian mention of Parthia is in the Behistun inscription of Darius I, where Parthia is listed (in the typical Iranian clockwise order) among the governorates in the vicinity of Drangiana. The inscription dates to c. 520 BC. The center of the administration "may have been at Hecatompylus". The Parthians also appear in Herodotus' list of peoples subject to the Achaemenids; the historiographer treats the Parthians, Chorasmians, Sogdians and Areioi as peoples of a single satrapy (the 16th), whose annual tribute to the king he states to be only 300 talents of silver. This "has rightly caused disquiet to modern scholars."

At the Battle of Gaugamela in 331 BC between the forces of Darius III and those of Alexander the Great, one such Parthian unit was commanded by Phrataphernes, who was at the time Achaemenid governor of Parthia. Following the defeat of Darius III, Phrataphernes surrendered his governorate to Alexander when the Macedonian arrived there in the summer of 330 BC. Phrataphernes was reappointed governor by Alexander.

Under the Seleucids

Following the death of Alexander, in the Partition of Babylon in 323 BC, Parthia became a Seleucid governorate under Nicanor. Phrataphernes, the former governor, became governor of Hyrcania. In 320 BC, at the Partition of Triparadisus, Parthia was reassigned to Philip, former governor of Sogdiana. A few years later, the province was invaded by Peithon, governor of Media Magna, who then attempted to make his brother Eudamus governor. Peithon and Eudamus were driven back, and Parthia remained a governorate in its own right.

In 316 BC, Stasander, a vassal of Seleucus I Nicator and governor of Bactria (and, it seems, also of Aria and Margiana) was appointed governor of Parthia. For the next 60 years, various Seleucids would be appointed governors of the province.

In 247 BC, following the death of Antiochus II, Ptolemy III seized control of the Seleucid capital at Antioch, and "so left the future of the Seleucid dynasty for a moment in question." Taking advantage of the uncertain political situation, Andragoras, the Seleucid governor of Parthia, proclaimed his independence and began minting his own coins.

Meanwhile, "a man called Arsaces, of Scythian or Bactrian origin, elected leader of the Parni", an eastern-Iranian peoples from the Tajen/Tajend River valley, south-east of the Caspian Sea. Following the secession of Parthia from the Seleucid Empire and the resultant loss of Seleucid military support, Andragoras had difficulty in maintaining his borders, and about 238 BC – under the command of "Arsaces and his brother Tiridates" – the Parni invaded Parthia and seized control of Astabene (Astawa), the northern region of that territory, the administrative capital of which was Kabuchan (Kuchan in the vulgate).

A short while later the Parni seized the rest of Parthia from Andragoras, killing him in the process. Although an initial punitive expedition by the Seleucids under Seleucus II was not successful, the Seleucids under Antiochus III recaptured Arsacid controlled territory in 209 BC from Arsaces' (or Tiridates') successor, Arsaces II. Arsaces II sued for peace and accepted vassal status, and it was not until Arsaces II's grandson (or grand-nephew) Phraates I, that the Arsacids/Parni would again begin to assert their independence.

Under the Arsacids

Main article: Parthian Empire

From their base in Parthia, the Arsacid dynasts eventually extended their dominion to include most of Greater Iran. They also quickly established several eponymous branches on the thrones of Armenia, Iberia, and Caucasian Albania. Even though the Arsacids only sporadically had their capital in Parthia, their power base was there, among the Parthian feudal families, upon whose military and financial support the Arsacids depended. In exchange for this support, these families received large tracts of land among the earliest conquered territories adjacent to Parthia, which the Parthian nobility then ruled as provincial rulers. The largest of these city-states were Kuchan, Semnan, Gorgan, Merv, Zabol and Yazd.

From about 105 BC onwards, the power and influence of this handful of Parthian noble families was such that they frequently opposed the monarch, and would eventually be a "contributory factor in the downfall" of the dynasty.

From about 130 BC onwards, Parthia suffered numerous incursions by various nomadic tribes, including the Sakas, the Yuezhi, and the Massagetae. Each time, the Arsacid dynasts responded personally, doing so even when there were more severe threats from Seleucids or Romans looming on the western borders of their empire (as was the case for Mithridates I). Defending the empire against the nomads cost Phraates II and Artabanus I their lives.

The Roman Crassus attempted to conquer Parthia in 52 BC but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Carrhae. Caesar was planning another invasion when he was assassinated in 44 BC. A long series of Roman-Parthian wars followed.

Around 32 BC, civil war broke out when a certain Tiridates rebelled against Phraates IV, probably with the support of the nobility that Phraates had previously persecuted. The revolt was initially successful, but failed by 25 BC. In 9/8, the Parthian nobility succeeded in putting their preferred king on the throne, but Vonones proved to have too tight a budgetary control, so he was usurped in favor of Artabanus II, who seems to have been a non-Arsacid Parthian nobleman. But when Artabanus attempted to consolidate his position (at which he was successful in most instances), he failed to do so in the regions where the Parthian provincial rulers held sway.

By the 2nd century AD, the frequent wars with neighboring Rome and with the nomads, and the infighting among the Parthian nobility had weakened the Arsacids to a point where they could no longer defend their subjugated territories. The empire fractured as vassalaries increasingly claimed independence or were subjugated by others, and the Arsacids were themselves finally vanquished by the Persian Sassanids, a formerly minor vassal from southwestern Iran, in April 224.

Under the Sasanians

Parthia was likely the first region conquered by Ardashir I after his victory over Artabanus IV, showing the importance of the province to the founder of the Sasanian dynasty. Some of the Parthian nobility continued to resist Sasanian dominion for some time, but most switched their allegiance to the Sasanians very early. Several families that claimed descent from the Parthian noble families became a Sasanian institution known as the "Seven houses", five of which are "in all probability" not Parthian, but contrived genealogies "in order to emphasize the antiquity of their families."

Parthia continued to hold importance throughout the 3rd century. In his Ka'be-ye Zardusht inscription Shapur I lists the province of Parthia in second place after Pars. The Abnun inscription describes the Roman invasion of 243/44 as an attack on Pars and Parthia. Considering the Romans never went further than Mesopotamia, "Pars and Parthia" may stand for the Sasanian Empire itself. Parthia was also the second province chosen for settlement by Roman prisoners of war after the Battle of Edessa in 260.

Language and literature

Main article: Parthian language

The Parthians spoke Parthian, a northwestern Iranian language. No Parthian literature survives from before the Sassanid period in its original form, and they seem to have written down only very little. The Parthians did, however, have a thriving oral minstrel-poet culture, to the extent that their word for "minstrel" (gosan) survives to this day in many Iranian languages and especially in Armenian (gusan), on which it exercised heavy (especially lexical and vocabulary) influence. These professionals were evident in every facet of Parthian daily life, from cradle to grave, and they were entertainers of kings and commoners alike, proclaiming the worthiness of their patrons through association with mythical heroes and rulers. These Parthian heroic poems, "mainly known through Persian of the lost Middle Persian Xwaday-namag, and notably through Firdausi's Shahnameh, doubtless not yet wholly lost in the Khurasan of day."

In Parthia itself, attested use of written Parthian is limited to the nearly three thousand ostraca found (in what seems to have been a wine storage) at Nisa, in present-day Turkmenistan. A handful of other evidence of written Parthian has been found outside Parthia, the most important of these being the part of a land-sale document found at Avroman (in the Kermanshah province of Iran), and more ostraca, graffiti and the fragment of a business letter found at Dura-Europos in present-day Syria.

The Parthian Arsacids do not seem to have used Parthian until relatively late, and the language first appears on Arsacid coinage during the reign of Vologases I (51–58 AD). Evidence that use of Parthian was nonetheless widespread comes from early Sassanid times; the declarations of the early Persian kings were—in addition to their native Middle Persian—also inscribed in Parthian.

The old poems known as fahlaviyat mostly come from the areas which were considered part of Parthia in the Islamic period. These poems have the characteristics of oral literature and may have continued the oral traditions of Parthian minstrels.

Society

City-states of "some considerable size" existed in Parthia as early as the 1st millennium BC, "and not just from the time of the Achaemenids or Seleucids." However, for the most part, society was rural, and dominated by large landholders with large numbers of serfs, slaves, and other indentured labor at their disposal. Communities with free peasants also existed.

By Arsacid times, Parthian society was divided into the four classes (limited to freemen). At the top were the kings and near family members of the king. These were followed by the lesser nobility and the general priesthood, followed by the mercantile class and lower-ranking civil servants, and with farmers and herdsmen at the bottom.

Little is known of the Parthian economy, but agriculture must have played the most important role in it. Significant trade first occurs with the establishment of the Silk road (c. 114 BC), when Hecatompylos became an important junction.

Parthian cities

Nisa (Nissa, Nusay) or Mithradātkert, located on a main trade route, was one of the earliest capitals of the Parthian Empire (c. 250 BC). The city is located in the northern foothills of the Kopetdag mountains, 11 miles west of present-day city of Ashgabat (the capital of Turkmenistan). Nisa had a "soaring two-story hall in the Hellenistic Greek style" and temple complexes used by early Arsaces dynasty. During the reign of Mithridates I of Parthia (c. 171 – 138 BC) it was renamed Mithradatkirt ("fortress of Mithradates"). Merv (modern-day Mary) was another Parthian city.

See also

Citations

- ^ Ghodrat-Dizaji, Mehrdad (2016-08-30), "Remarks on the Location of the Province of Parthia in the Sasanian Period", The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires, Oxbow Books, pp. 42–46, doi:10.2307/j.ctvh1dkb6.8, ISBN 978-1-78570-210-5, retrieved 2021-02-15

- Lendering, Jona (2001). "Parthia". Livius. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- Payne, Richard (2013). "Commutatio et Contentio: Studies in the Late Roman, Sasanian, and Early Islamic Near East. In Memory of Zeev Rubin ed. by Henning Börm, Josef Wiesehöfer (review)". Journal of Late Antiquity. 6 (1): 187–190. doi:10.1353/jla.2013.0011. ISSN 1942-1273. S2CID 162332829.

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 127.

- Diakonoff 1985, p. 104, n.1.

- Mallowan 1985, p. 406.

- "Parthia | ancient region, Iran". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 2017-09-20. Retrieved 2017-09-20.

- Cook 1985, p. 248.

- Cook 1985, p. 252.

- Bivar 2003, para. 6.

- ^ Curtis 2007, p. 7.

- Lecoq 1987, p. 151.

- ^ Bivar 1983, p. 29.

- Bickerman 1983, p. 19.

- Bivar 1983, p. 31.

- ^ Schippmann 1987, p. 527.

- Schippmann 1987, p. 528.

- Schippmann 1987, p. 529.

- Lukonin 1983, p. 704.

- Livshits, V. A.; Nitkin, A. B. (1992). "Some Notes on the Inscription from Naṣrābād". Bulletin of the Asia Institute. New Series. 5: 41–44. JSTOR 24048283. OCLC 911527026.

- Boyce 1983, p. 1151.

- electricpulp.com. "ARMENIA AND IRAN iv. Iranian influences – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Boyce 1983, p. 1115.

- Boyce 1983, p. 1157.

- Boyce 1983, p. 1153.

- ^ Schippmann 1987, p. 532.

- "Старая и Новая Ниса :: Исторические памятники Туркменистана". www.turkmenistan.orexca.com. Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2013). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-691-15773-3.

General and cited references

- Bickerman, Elias J. (1983), "The Seleucid Period", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3, Cambridge University Press, pp. 3–20.

- Bivar, A.D.H. (1983), "The Political History of Iran under the Arsacids", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3, Cambridge UP, pp. 21–99.

- Bivar, A.D.H. (2003), "Gorgan v.: Pre-Islamic History", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 11, New York: iranica.com.

- Boyce, Mary (1983), "Parthian writings and literature", in Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 3, Cambridge UP, pp. 1151–1165.

- Cook, J.M. (1985), "The Rise of the Achaemenids and Establishment of their Empire", in Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 200–291

- Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (2007), "The Iranian Revival in the Parthian Period", in Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh and Sarah Stewart (ed.), The Age of the Parthians: The Ideas of Iran, vol. 2, London & New York: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., in association with the London Middle East Institute at SOAS and the British Museum, pp. 7–25, ISBN 978-1-84511-406-0

- Diakonoff, I.M. (1985), "Media I: The Medes and their Neighbours", in Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.), Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 2, Cambridge University Press, pp. 36–148.

- Lecoq, Pierre (1987), "Aparna", Encyclopaedia Iranica, vol. 2, New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, p. 151.