| Revision as of 12:04, 11 June 2010 view source71.182.190.176 (talk) →Countries where English is a major language: therefor->therefore← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:23, 16 January 2025 view source EvanBaldonado (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,903 editsm Replace hyphen with en-dash. | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|West Germanic language}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=July 2014}} | |||

| {{Infobox language | |||

| | name = English | |||

| | pronunciation = {{IPAc-en|ˈ|ɪ|ŋ|ɡ|l|ᵻ|ʃ}}{{sfn|Oxford Learner's Dictionary|2015|loc=Entry: }} | |||

| | states = The ], including the {{enum|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | speakers = ]: {{nowrap|380 million}} | |||

| | speakers_label = Speakers | |||

| | date = 2021 | |||

| | ref = <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/ethnologue200/|title=What are the top 200 most spoken languages?|website=Ethnologue|date=2023|access-date=3 October 2023|archive-date=18 June 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230618002011/https://www.ethnologue.com/insights/ethnologue200/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | speakers2 = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ]: {{nowrap|1.077 billion}} (2021)<ref name="ethnologue">{{e26|eng|English}}</ref> | |||

| * ]: 1.457 billion}} | |||

| | familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| | fam2 = ] | |||

| | fam3 = ] | |||

| | fam4 = ] | |||

| | fam5 = ] | |||

| | fam6 = ] | |||

| | ancestor = ] | |||

| | ancestor2 = ] | |||

| | ancestor3 = ] | |||

| | ancestor4 = ] | |||

| | ancestor5 = ] | |||

| | script = {{plainlist| | |||

| * ] (]) | |||

| * ] (historical) | |||

| * ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | nation = {{Collapsible list|titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left|title=]| | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| }}<br />{{Collapsible list|titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left|title=]| | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| }}<br />{{Collapsible list|titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left|title=]| | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| }}<br />{{Collapsible list|titlestyle=font-weight:normal; background:transparent; text-align:left|title=Various organisations| | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| |] | |||

| }} | |||

| | iso1 = en | |||

| | iso2 = eng | |||

| | iso3 = eng | |||

| | lingua = 52-ABA | |||

| | notice = IPA | |||

| | sign = ] {{nwr|(multiple systems)}} | |||

| | glotto = stan1293 | |||

| | glottorefname = English | |||

| | mapscale = 1.25 | |||

| | map = Anglospeak (subnational version).svg | |||

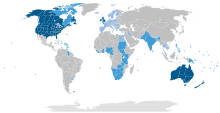

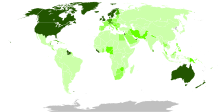

| | mapcaption = {{legend|#004288|Countries and territories where English is the native language of the majority}} | |||

| {{legend|#79c1ff|Countries and territories where English is an official or administrative language but not a majority native language}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{English language}} | {{English language}} | ||

| '''English''' is a ] that arose in ] and south-eastern ] in the time of the ]. Following the economic, political, military, scientific, cultural, and colonial influence of ] and the ] from the 18th century, and of the ] since the mid 20th century,<ref>], pp. 2245–2247.</ref><ref>], p. 1.</ref><ref>], p. 21.</ref><ref>], pp. 127–133.</ref> it has been ] around the world, become the ] of international discourse, and has acquired use as '']'' in many regions.<ref>], pp. 87–89.</ref><ref>], p. 60.</ref> It is widely learned as a ] and used as an ] of the ] and many ] countries, as well as in many world organisations. | |||

| '''English''' is a ] in the ], whose speakers, called ], originated in ] on the island of ].{{sfn|The Routes of English}}{{sfn|Crystal|2003a|p=6}}{{sfn|Wardhaugh|2010|p=55}} The namesake of the language is the ], one of the ancient ] that ]. It is the ] in the world, primarily due to the global influences of the former ] (succeeded by the ]) and the ].<ref>Salome, Rosemary (2022). ''''. Oxford University Press, pp. 6–7.</ref> English is the ], after ] and ];{{sfn|Ethnologue|2010}} it is also the most widely learned ] in the world, with more second-language speakers than native speakers. | |||

| Historically, English originated from several dialects, now collectively termed ], which were brought to the eastern coast of the ] by ] settlers beginning in the 5th century.{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} English was further influenced by the ] of ] invaders. | |||

| English is either the official language or one of the official languages in ] (such as ], ], and ]). In some other countries, it is the sole or dominant language for historical reasons without being explicitly defined by law (such as in the United States and ]).{{sfn|Crystal|2003b|pp=108–109}} It is a ], the ], and many other international and regional organisations. It has also become the de facto ] of diplomacy, ], technology, international trade, logistics, tourism, aviation, entertainment, and the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/18/books/review/the-rise-of-english-rosemary-salomone.html|title=How the English Language Conquered the World|last=Chua|first=Amy|website=]|date=18 January 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220301222132/https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/18/books/review/the-rise-of-english-rosemary-salomone.html|archive-date=1 March 2022|url-status=live}}</ref> English accounts for at least 70% of total speakers of the ] branch, and {{asof|2021|lc=y}}, '']'' estimated that there were over 1.5 billion speakers worldwide.<ref name="ethnologue" /> | |||

| After the time of the ], Old English developed into ], borrowing heavily from the ] vocabulary and spelling conventions. The etymology of the word "English" is a derivation from the 12th century Old English ''englisc'' from ''Engle'', " ]".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/English |title=English - Definition from the Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary |publisher=Merriam-webster.com |date=2007-04-25 |accessdate=2010-01-02}}</ref> | |||

| ] emerged from a group of West Germanic dialects spoken by the ]. Late Old English borrowed some grammar and core vocabulary from ], a ].<ref name="Wolff">{{cite book |last=Finkenstaedt |first=Thomas |author2=Dieter Wolff |title=Ordered profusion; studies in dictionaries and the English lexicon |publisher=C. Winter |year=1973 |isbn=978-3-533-02253-4}}</ref>{{sfn|Bammesberger|1992|p=30}}{{sfn|Svartvik|Leech|2006|p=39}} Then, ] borrowed vocabulary extensively from ], which are the source of approximately ], and from ], which is ].<ref>{{cite book |doi=10.1017/chol9780521264754.006 |chapter=Lexis and Semantics |title=The Cambridge History of the English Language |date=1992 |last1=Burnley |first1=David |pages=409–499 |isbn=978-1-139-05553-6 |editor-first1=Norman |editor-last1=Blake |quote=Latin and French each account for a little more than 28 per cent of the lexis recorded in the ] (Finkenstaedt & Wolff 1973) }}</ref> As such, though most of its total vocabulary comes from ], Modern English's grammar, phonology, and most commonly used words in everyday use keep it ] classified under the Germanic branch. It exists on a ] with ] and is then most closely related to the ] and ]. | |||

| ] developed with the ] that began in 15th-century England, and continues to adopt foreign words from a variety of languages, as well as coining new words. A significant number of English words, especially technical words, have been constructed based on roots from ] and ]. | |||

| == Classification == | |||

| ==Significance== | |||

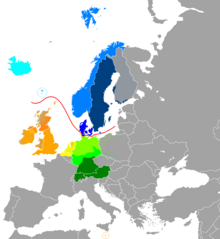

| [[File:Europe germanic-languages 2.PNG|thumb| | |||

| {{See also|English-speaking world|Anglosphere}} | |||

| ''']''' | |||

| Modern English, sometimes described as the first global ],<ref>{{cite web |title=Global English: gift or curse? |url=http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract;jsessionid=92238D4607726060BCBD3DB70C472D0F.tomcat1?fromPage=online&aid=291932 |accessdate=2005-04-04}}</ref><ref name = "Graddol"/> is the ] or in some instances even the required ] of communications, science, business, aviation, entertainment, radio and diplomacy.<ref name="triumph">{{cite news |url=http://www.economist.com/world/europe/displayStory.cfm?Story_ID=883997 |title=The triumph of English |accessdate=2007-03-26 |date=2001-12-20 |publisher=The Economist }}{{subscription}}</ref> Its spread beyond the ] began with the growth of the ], and by the late nineteenth century its reach was truly global.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ehistling-pub.meotod.de/01_lec06.php |title=Lecture 7: World-Wide English |accessdate=2007-03-26|publisher=<sub>E</sub>HistLing }}</ref> Following the British colonisation of North America, it became the dominant language in the United States and in Canada. The growing economic and cultural influence of the United States and its status as a global superpower since World War II have significantly accelerated the language's spread across the planet.<ref name="Graddol">{{cite web |url=http://www.britishcouncil.org/de/learning-elt-future.pdf |format=PDF|title=The Future of English? |accessdate=2007-04-15 |year=1997 |author=] |publisher=The British Council }}</ref> | |||

| {{legend|#FFA500|English}} | |||

| {{legend|#FF8C00|]}} | |||

| within the ''']''', which also include | |||

| {{legend|#FFD700|] (], ], ]);}} within the ''']''', which also include | |||

| {{legend|#7FFF00|]/Saxon;}} | |||

| within the ''']''', which also include | |||

| {{legend|#FFFF00|] in Europe and ] in Africa}} | |||

| ......] (]): | |||

| {{legend|#00FF00|]; in ]: ]}} | |||

| {{legend|#008000|]}} | |||

| ...... ]]] | |||

| ] language family]] | |||

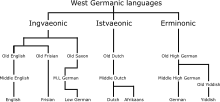

| English is an ] and belongs to the ] group of the ].{{sfn|Bammesberger|1992|pp=29–30}} ] originated from a Germanic tribal and ] along the ]n ] coast, whose languages gradually evolved into the ] in the ], and into the Frisian languages and ]/Low Saxon on the continent. The Frisian languages, which together with the Anglic languages form the ], are the closest living relatives of English. Low German/Low Saxon is also closely related, and sometimes English, the Frisian languages, and Low German are grouped together as the ] languages, though this grouping remains debated.{{sfn|Bammesberger|1992|p=30}} Old English evolved into ], which in turn evolved into Modern English.{{sfn|Robinson|1992}} Particular dialects of Old and Middle English also developed into a number of other Anglic languages, including ]{{sfn|Romaine|1982|pp=56–65}} and the extinct ] and ]s of Ireland.{{sfn|Barry|1982|pp=86–87}} | |||

| Like ] and ], the development of English in the British Isles isolated it from the continental Germanic languages and influences, and it has since diverged considerably. English is not ] with any continental Germanic language, as it differs in ], ], and ]. However, some of these, such as Dutch or Frisian, do show strong affinities with English, especially with its earlier stages.{{sfn|Harbert|2006}}{{pn|date=July 2024}} | |||

| A working knowledge of English has become a requirement in a number of fields, occupations and professions such as medicine and computing; as a consequence over a billion people speak English to at least a basic level (see ]). It is also one of six official languages of the ]. | |||

| Unlike Icelandic and Faroese, which were isolated, the development of English was influenced by a long series of invasions of the British Isles by other peoples and languages, particularly ] and ]. These left a profound mark of their own on the language, so that English shows some similarities in vocabulary and grammar with many languages outside its linguistic ]s—but it is not mutually intelligible with any of those languages either. Some scholars have argued that English can be considered a ] or a ]—a theory called the ]. Although the great influence of these languages on the vocabulary and grammar of Modern English is widely acknowledged, most specialists in language contact do not consider English to be a true mixed language.{{sfn|Thomason|Kaufman|1988|pp=264–265}}{{sfn|Watts|2011|loc=Chapter 4}} | |||

| One impact of the growth of English has been to reduce native ] in many parts of the world, and its influence continues to play an important role in ].<ref name="Crystal-LanguageDeath">{{cite book | last = Crystal | first = David | authorlink = David Crystal | title = Language Death | publisher = ] | year = 2002 | doi = 10.2277/0521012716 | isbn = 0521012716 }}</ref> Conversely the natural internal variety of English along with ] and ]s have the potential to produce new distinct languages from English over time.<ref name="Cheshire">{{cite book | last = Cheshire | first = Jenny | authorlink = Jenny Cheshire | title = English Around The World: Sociolinguistic Perspectives | publisher = ] | year = 1991 | doi = 10.2277/0521395658 | isbn = 0521395658 }}</ref> | |||

| English is classified as a Germanic language because it shares ]s with other Germanic languages including ], ], and ].{{sfn|Durrell|2006}} These shared innovations show that the languages have descended from a single common ancestor called ]. Some shared features of Germanic languages include the division of verbs into ] and ] classes, the use of ]s, and the sound changes affecting ] consonants, known as ] and ]s. English is classified as an Anglo-Frisian language because Frisian and English share other features, such as the ] of consonants that were velar consonants in Proto-Germanic (see {{section link|Phonological history of Old English|Palatalization}}).{{sfn|König|van der Auwera|1994}} | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|History of the English language}} | |||

| English is a ] language that originated from the ] and ] dialects brought to ] by Germanic settlers and Roman auxiliary troops from various parts of what is now northwest Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands in the 5th century{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}}. Up to that point, in ] the native population is assumed to have spoken the ] ] alongside the ]al influence of Latin—the Roman influence having been extant for 400 years.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Blench |first1=R.|last2=Spriggs |first2=Matthew |title=Archaeology and language: correlating archaeological and linguistic hypotheses |page=285 |year=1999 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=0415117616 |url=http://books.google.com/?id=DWMHhfXxLaIC&pg=PA285&dq=brythonic+language&cd=1#v=onepage&q=brythonic%20language }}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| One of these incoming Germanic tribes was the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.anglik.net/englishlanguagehistory.htm |title=Anglik English language resource |publisher=Anglik.net |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> who ] wrote moved entirely to Britain from their previous home<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ccel.org/ccel/bede/history.v.i.xiv.html |title=Bede's Ecclesiastical History of England | Christian Classics Ethereal Library |publisher=Ccel.org |date=2005-06-01 |accessdate=2010-01-02}}</ref>. The names 'England' (from ''Engla land'' "Land of the Angles") and ''English'' (Old English ''Englisc'') are derived from the name of this tribe—but ], ] and a range of Germanic peoples from the coasts of ], ], ] and Southern ] also moved to Britain in this era.<ref>{{cite book|last=Collingwood|first=R. G.|authorlink=R. G. Collingwood|coauthors=et al|title=Roman Britain and English Settlements|publisher=Clarendon|location=Oxford, England|year=1936|pages=325 et sec|chapter=The English Settlements. The Sources for the period: Angles, Saxons, and Jutes on the Continent}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.utexas.edu/cola/centers/lrc/eieol/engol-0-X.html |title=Linguistics research center Texas University |publisher=Utexas.edu |date=2009-02-20 |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/firsteuro/invas.html |title=The Germanic Invasions of Western Europe, Calgary University |publisher=Ucalgary.ca |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|History of English}} | |||

| === Overview of history === | |||

| Initially, Old English was a diverse group of dialects, reflecting the varied origins of the ]<ref>David Graddol, Dick Leith, and Joan Swann, ''English: History, Diversity and Change'' (New York: Routledge, 1996), 101.</ref> but one of these dialects, ], eventually came to dominate, and it is in this that the famous epic poem ] is written. | |||

| The earliest varieties of an English language, collectively known as ] or "Anglo-Saxon", evolved from a group of ] dialects brought to Britain in the 5th century. Old English dialects were later influenced by ]-speaking ], starting in the 8th and 9th centuries. ] began in the late 11th century after the ] of England, when a considerable amount of ] vocabulary was incorporated into English over some three centuries.<ref name="Ian Short 2007">{{cite book | last=Short | first=Ian | title=A Companion to the Anglo-Norman World | chapter=Language and Literature | publisher=Boydell and Brewer Limited | date=2002-01-01 | isbn=978-1-84615-046-3 | doi=10.1017/9781846150463.011 | pages=191–214}}</ref>{{sfn|Crystal|2003b|p=30}} | |||

| ] began in the late 15th century with the start of the ] and the ] trend of borrowing further ] and ] words and roots, concurrent with the introduction of the ] to London. This era notably culminated in the ] and ].{{sfn|How English evolved into a global language|2010}}<ref>{{britannica URL|topic/English-language/Historical-background|English language: Historical background}}</ref> The printing press greatly standardised English spelling,<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Upward |first1=Christopher |title=The History of English Spelling |last2=Davidson |first2=George |publisher=Wiley-Blackwell |year=2011 |isbn=978-1-405-19024-4 |location=Oxford |page=84}}</ref> which has remained largely unchanged since then, despite a wide variety of later sound shifts in English dialects. | |||

| Old English was soon transformed by two waves of invasion. The first was by speakers of the ] language branch when ] and ] started the conquering and colonisation of northern parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries (see ]). The second was by speakers of the ] ] in the 11th centuary with the ]. Norman developed into ], and then ] - and introduced a layer of words especially via the courts and government. As well as extending the lexicon with Scandinavian and Norman words these two events also simplified the grammar and transformed English into a borrowing language—more than normally open to accept new words from other languages. | |||

| Modern English has spread around the world since the 17th century as a consequence of the worldwide influence of the ] and the United States. Through all types of printed and electronic media in these countries, English has become the leading language of international ] and the ] in many regions and professional contexts such as science, ], and law.{{sfn|The Routes of English}} Its ] is the result of a gradual change from a ] pattern typical of ] with a rich ] and relatively ] to a mostly ] pattern with little inflection and a fairly fixed ].{{sfn|König|1994|page=539}} Modern English relies more on ]s and ] for the expression of complex ], ]s and ]s, as well as ]s, ]s, and some ]. | |||

| The linguistic shifts in English following the Norman invasion,produced what is now referred to as ], with ]'s '']'' being the best known work. | |||

| === Proto-Germanic to Old English === | |||

| Throughout all this period Latin in some form was the ] of European intellectual life, first the ] of the Christian Church, but later the ] ], and those that wrote or copied texts in Latin<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.spiritus-temporis.com/old-english-language/latin-influence.html |title=Old English language - Latin influence |publisher=Spiritus-temporis.com |date= |accessdate=2010-01-02}}</ref> commonly coined new terms from Latin to refer to things or concepts for which there was no existing native English word. | |||

| {{Main|Old English}} | |||

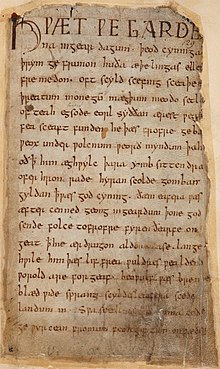

| ]'', an Old English epic poem ] in ] script between 975 AD and 1025 AD: {{lang|ang|Hƿæt ƿē Gārde/na ingēar dagum þēod cyninga / þrym ge frunon...}} ("Listen! We of the Spear-Danes from days of yore have heard of the glory of the folk-kings...")]] | |||

| The earliest form of English is called ] or Anglo-Saxon ({{Circa|450–1150}}). Old English developed from a set of ] dialects, often grouped as ] or ], and originally spoken along the coasts of ], Lower Saxony and southern ] by Germanic peoples known to the historical record as the ], ], and ].<ref>Baugh, Albert (1951). A History of the English Language. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 60–83, 110–130</ref> From the 5th century, the Anglo-Saxons ] as ]. By the 7th century, this Germanic language of the Anglo-Saxons ], replacing the languages of ] (43–409): ], a ], and ], brought to Britain by the Roman occupation.{{sfn|Collingwood|Myres|1936}}{{sfn|Graddol|Leith|Swann et al.|2007}}{{sfn|Blench|Spriggs|1999}} At this time, these dialects generally resisted influence from the then-local Brittonic and Latin languages. ''England'' and ''English'' (originally {{lang|ang|Ænglaland}} and {{lang|ang|Ænglisc}}) are both named after the Angles.{{sfn|Bosworth|Toller|1921}} English may have a small amount of ] influence from Common Brittonic, and a number of possible ] have been proposed, but whether most of these supposed Brittonicisms are actually a direct result of Brittonic substrate influence is disputed. | |||

| Old English was divided into four dialects: the Anglian dialects (] and ]) and the Saxon dialects (] and ]).{{sfn|Campbell|1959|p=4}} Through the educational reforms of ] in the 9th century and the influence of the kingdom of ], the West Saxon dialect became the ].{{sfn|Toon|1992|loc=Chapter: Old English Dialects}} The ] '']'' is written in West Saxon, and the earliest English poem, '']'', is written in Northumbrian.{{sfn|Donoghue|2008}} Modern English developed mainly from Mercian, but the ] developed from Northumbrian. A few short inscriptions from the early period of Old English were written using a ].{{sfn|Gneuss |2013|p=23}} By the 6th century, a ] was adopted, written with ] ]s. It included the runic letters '']'' {{angbr|{{lang|ang|ƿ}}}} and '']'' {{angbr|{{lang|ang|þ}}}}, and the modified Latin letters '']'' {{angbr|{{lang|ang|ð}}}}, and '']'' {{angbr|{{lang|ang|æ}}}}.{{sfn|Gneuss |2013|p=23}}{{sfn|Denison|Hogg|2006|pp=30–31}} | |||

| ], that includes the works of ] and the ], is generally dated from about 1550, and as a result of the growth of the ] it was adopted in North America, India, Africa, Australia and many other regions—a trend extended with the emergence of the United States as a superpower in the mid-twentieth century. | |||

| Old English is essentially a distinct language from Modern English and is virtually impossible for 21st-century unstudied English-speakers to understand. Its grammar was similar to that of modern German: ] had many more ], and word order was ] than in Modern English. Modern English has ] in pronouns (''he'', ''him'', ''his'') and has a few verb inflections (''speak'', ''speaks'', ''speaking'', ''spoke'', ''spoken''), but Old English had case endings in nouns as well, and verbs had more ] and ] endings.{{sfn|Hogg|1992|loc=Chapter 3. Phonology and Morphology}}{{sfn|Smith|2009}}{{sfn|Trask|Trask|2010}} Its closest relative is ], but even some centuries after the Anglo-Saxon migration, Old English retained considerable ] with other Germanic varieties. Even in the 9th and 10th centuries, amidst the ] and other ] invasions, there is historical evidence that Old Norse and Old English retained considerable mutual intelligibility,<ref name="Gay 2014">{{cite thesis |last1=Gay |first1=Eric Martin |title=Old English and Old Norse: An Inquiry into Intelligibility and Categorization Methodology |type=MA thesis |publisher=University of South Carolina |date=2014 |url=https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2604/ |access-date=16 December 2022 |archive-date=16 December 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221216164617/https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2604/ |url-status=live}}</ref> although probably the northern dialects of Old English were more similar to Old Norse than the southern dialects. Theoretically, as late as the 900s AD, a commoner from certain (northern) parts of England could hold a conversation with a commoner from certain parts of Scandinavia. Research continues into the details of the myriad tribes in peoples in England and Scandinavia and the mutual contacts between them.<ref name="Gay 2014" /> | |||

| ==Classification and related languages== | |||

| The English language belongs to the ] sub-group of the ] branch of the ], a member of the ]. The closest living relatives of English are the ], spoken primarily in ] and parts of ], and ], spoken on the southern fringes of the ] in ], the ], and ]. As Scots is viewed by some linguists to be a group of English dialects rather than a separate language, Frisian is often considered to be the closest living relative. | |||

| The translation of ] from 1000 shows examples of case endings (] plural, ] plural, ] singular) and a verb ending (] plural): | |||

| After Scots and Frisian, come those Germanic languages that are more distantly related: the non-Anglo-Frisian ] (], ], ], ]), and the ] (], ], ], ], and ]). With the exception of Scots, and on an extremely basic level, Frisian, none of the other languages is mutually intelligible with English, owing in part to the divergences in ], ], ], and ], and to the isolation afforded to the English language by the British Isles, although some such as Dutch do show strong affinities with English, especially to earlier stages of the language. Dutch, for example, is most similar to ], while German and Icelandic are more like ]. This isolation has allowed English and Scots to develop independently of the Continental Germanic languages and their influences over time.<ref>A History of the Entlish Language|Page: 336 | By: Albert C. Baugh and Thomas Cable | Publisher: Routledge; 5 edition (March 21, 2002)</ref> | |||

| * {{lang|ang|Foxas habbað holu and heofonan fuglas nest}} | |||

| * Fox-as habb-að hol-u and heofon-an fugl-as nest-∅ | |||

| * fox-{{sc|NOM.PL}} have-{{sc|PRS.PL}} hole-{{sc|ACC.PL}} and heaven-{{sc|GEN.SG}} bird-{{sc|NOM.PL}} nest-{{sc|ACC.PL}} | |||

| * "Foxes have holes and the birds of heaven nests"{{sfn|Lass|2006|pp=46–47}} | |||

| === Influence of Old Norse === | |||

| Lexical differences with the other Germanic languages have arisen from several causes, such as natural semantic drift caused by isolation, and heavy usage in English of words taken from Latin (for example, "exit", vs. Dutch ''uitgang'') (literally "out-gang" with "gang" as in "gangway") and French "change" vs. German ''Änderung'', "movement" vs. German ''Bewegung'' (literally "othering" and "be-way-ing" ("proceeding along the way")). | |||

| From the 8th to the 11th centuries, Old English gradually ] through ] with ] in some regions. The waves of Norse (Viking) colonisation of northern parts of the British Isles in the 8th and 9th centuries put Old English into intense contact with ], a ] language. Norse influence was strongest in the north-eastern varieties of Old English spoken in the ] area around York, which was the centre of Norse colonisation; today these features are still particularly present in ] and ]. The centre of Norsified English was in the ] around ]. After 920 CE, when Lindsey was incorporated into the Anglo-Saxon polity, English spread extensively throughout the region. | |||

| Preference of one synonym over another has also caused a differentiation in lexis, even where both words are Germanic (for instance, both English ''care'' and German ''Sorge'' descend from Proto-Germanic *''karo'' and *''surgo'' respectively, but *''karo'' became the dominant word in English for "care" while in German, Dutch, and Scandinavian languages, the *''surgo'' root prevailed. *''Surgo'' still survives in English as ''sorrow''). | |||

| An element of Norse influence that continues in all English varieties today is the third person pronoun group beginning with ''th-'' (''they, them, their'') which replaced the Anglo-Saxon pronouns with {{lang|ang|h-}} ({{lang|ang|hie, him, hera}}).{{sfn|Thomason|Kaufman|1988|pp=284–290}} Other core ] include "give", "get", "sky", "skirt", "egg", and "cake", typically displacing a native Anglo-Saxon equivalent. Old Norse in this era retained considerable mutual intelligibility with some dialects of Old English, particularly northern ones. | |||

| Although the syntax of German is significantly different from that of English and other Germanic languages, with different rules for setting up sentences (for example, German ''Ich '''habe''' noch nie etwas auf dem Platz '''gesehen''''', vs. English "I '''have''' never '''seen''' anything in the square"), English syntax remains extremely similar to that of the North Germanic languages, which are believed to have influenced English syntax during the Middle English Period (e.g., Norwegian ''Jeg '''har''' likevel aldri '''sett''' noe på torget''; Swedish ''Jag '''har''' ännu aldrig '''sett''' något på torget''). It is for this reason that despite a lack of mutual intelligibility, English-speakers and Scandinavians are able to learn one anothers' languages with relative ease.{{Citation needed|date=December 2009}} | |||

| === Middle English === | |||

| Dutch syntax is intermediate between English and German (e.g. ''Ik '''heb''' nog nooit iets '''gezien''' op het plein''). In spite of this difference, there are many similarities between English and other Germanic languages (e.g. English ''bring/brought/brought'', Dutch ''brengen/bracht/gebracht'', Norwegian ''bringe/brakte/brakt''; English ''eat/ate/eaten'', Dutch ''eten/at/gegeten'', Norwegian ''ete/åt/ett''), with the most similarities occurring between English and the languages of the Low Countries (Dutch and Low German) and Scandinavia. | |||

| {{Main|Middle English|Influence of French on English}} | |||

| ] in ], the world's oldest English-speaking university and world's ], founded in 1096]] | |||

| ] in ], the world's second-oldest English-speaking university and world's third-oldest university, founded in 1209]] | |||

| {{Quote box |align=center |quoted=true | | |||

| |salign=center | |||

| |quote={{lang|enm|Englischmen þeyz hy hadde fram þe bygynnyng þre manner speche, Souþeron, Northeron, and Myddel speche in þe myddel of þe lond, ... Noþeles by comyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes, and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys asperyed, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbytting.}}<br /><br />Although, from the beginning, Englishmen had three manners of speaking, southern, northern and midlands speech in the middle of the country, ... Nevertheless, through intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and then with Normans, amongst many the country language has arisen, and some use strange stammering, chattering, snarling, and grating gnashing. | |||

| |source= ], {{Circa|1385}}{{sfn|Hogg|2006|pp=360–361}} | |||

| }} | |||

| Middle English is often arbitrarily defined as beginning with the ] by ] in 1066, but it developed further in the period from 1150 to 1500.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fuster-Márquez |first1=Miguel |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QQLBqKjxuvAC |title=A Practical Introduction to the History of English |last2=Calvo García de Leonardo |first2=Juan José |publisher=Universitat de València |year=2011 |isbn=9788437083216 |location= |page=21 |access-date=19 December 2017}}</ref> | |||

| With the Norman conquest of England in 1066, the now-Norsified Old English language was subject to another wave of intense contact, this time with ], in particular ], influencing it as a superstrate. The Norman French spoken by the elite in England eventually developed into the ].<ref name="Ian Short 2007"/> Because Norman was spoken primarily by the elites and nobles, while the lower classes continued speaking English, the main influence of Norman was the introduction of a wide range of ]s related to politics, legislation and prestigious social domains.{{sfn|Svartvik|Leech|2006|p=39}}{{examples needed|date=December 2024}} Middle English also greatly simplified the inflectional system, probably in order to reconcile Old Norse and Old English, which were inflectionally different but morphologically similar. The distinction between nominative and accusative cases was lost except in personal pronouns, the instrumental case was dropped, and the use of the genitive case was limited to indicating ]. The inflectional system regularised many irregular inflectional forms,{{sfn|Lass|1992|pp=103–123}} and gradually simplified the system of agreement, making word order less flexible.{{sfn|Fischer|van der Wurff|2006|pages=111–13}} | |||

| Semantic differences cause a number of ] between English and its relatives—e.g., English ''time'' vs Norwegian ''time'' ("hour"), and differences in phonology can obscure words that really are related (''enough'' vs. German ''genug'', Danish ''nok''). Sometimes both semantics ''and'' phonology are different (German ''Zeit'' ("time") is related to English "tide", but the English word, through a transitional phase of meaning "period"/"interval", has come primarily to mean gravitational effects on the ocean by the moon, though the original meaning is preserved in forms like ''tidings'' and ''betide'', and phrases such as ''to tide over''). {{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} These differences, though minor, preclude mutual intelligibility, yet English is still much closer to other Germanic languages than to languages of any other family. | |||

| The transition from Old to Middle English can be placed during the writing of the '']''.<ref name="Johannesson2">{{Cite book |last1=Johannesson |first1=Nils-Lennart |title=Ormulum |last2=Cooper |first2=Andrew |date=2023 |url= https://reunido.uniovi.es/index.php/SELIM/article/download/20530/16515 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-289043-6 |series=Early English text society |location=Oxford}}</ref> The oldest Middle English texts that were written by the ] ], which highlights the blending of both Old English and Anglo-Norman elements in English for the first time. | |||

| Finally, English has been forming compound words and affixing existing words separately from the other Germanic languages for over 1500 years and has different habits in that regard. For instance, abstract nouns in English may be formed from native words by the suffixes "‑hood", "-ship", "-dom" and "-ness". All of these have cognate suffixes in most or all other Germanic languages, but their usage patterns have diverged, as German "Freiheit" vs. English "freedom" (the suffix "-heit" being cognate of English "-hood", while English "-dom" is cognate with German "-tum"). The Germanic languages Icelandic and Faroese also follow English in this respect, since, like English, they developed independent of German influences. | |||

| In Wycliff'e Bible of the 1380s, the verse Matthew 8:20 was written: {{lang|enm|Foxis han dennes, and briddis of heuene han nestis}}.<ref>{{cite web |last=Wycliffe |first=John |url=http://wesley.nnu.edu/fileadmin/imported_site/wycliffe/wycbible-all.pdf |publisher=Wesley NNU |title=Bible |access-date=9 April 2015 |archive-date=2 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170202202047/http://wesley.nnu.edu/fileadmin/imported_site/wycliffe/wycbible-all.pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> Here the plural suffix {{lang|enm|-n}} on the verb ''have'' is still retained, but none of the case endings on the nouns are present. By the 12th century Middle English was fully developed, integrating both Norse and French features; it continued to be spoken until the transition to early Modern English around 1500. Middle English literature includes ]'s '']'', and ]'s '']''. In the Middle English period, the use of regional dialects in writing proliferated, and dialect traits were even used for effect by authors such as Chaucer.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Horobin |first1=Simon |title=Chaucer's Middle English |url=https://opencanterburytales.dsl.lsu.edu/refmideng/ |website=The Open Access Companion to the Canterbury Tales |publisher=Louisiana State University |access-date=24 November 2019 |quote=The only appearances of their and them in Chaucer's works are in the Reeve's Tale, where they form part of the Northern dialect spoken by the two Cambridge students, Aleyn and John, demonstrating that at this time they were still perceived to be Northernisms |archive-date=3 December 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191203092713/https://opencanterburytales.dsl.lsu.edu/refmideng/ |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Many written ] words are also intelligible to an English speaker (though pronunciations are often quite different) because English absorbed a large vocabulary from ] and French, via ] after the Norman Conquest and directly from French in subsequent centuries. As a result, a large portion of English vocabulary is derived from French, with some minor spelling differences (word endings, use of old French spellings, etc.), as well as occasional divergences in meaning of so-called false friends: for example, compare "]" with the French "librairie", which means ]; in French, the word for "library" is "bibliothèque". | |||

| === Early Modern English === | |||

| The pronunciation of most French loanwords in English (with exceptions such as ''mirage'' or phrases like ''coup d’état'') has become completely anglicised and follows a typically English pattern of stress. {{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} Some North Germanic words also entered English because of the Danish invasion shortly before then (see ]); these include words such as "sky" (that now forms a false friendship with Danish ''sky'' meaning "cloud"), "window", "egg", and even "they" (and its forms) and "are" (the present plural form of "to be"). {{Citation needed|date=April 2008}} | |||

| {{Main|Early Modern English}} | |||

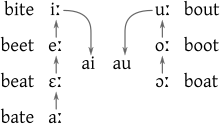

| ] showing how the pronunciation of the long vowels gradually shifted with the high vowels i: and u: breaking into diphthongs and the lower vowels each shifting their pronunciation up one level]] | |||

| The next period in the history of English was Early Modern English (1500–1700). Early Modern English was characterised by the ] (1350–1700), inflectional simplification, and linguistic standardisation. | |||

| The Great Vowel Shift affected the stressed long vowels of Middle English. It was a ], meaning that each shift triggered a subsequent shift in the vowel system. ] and ]s were ], and ]s were ] into ]s. For example, the word ''bite'' was originally pronounced as the word ''beet'' is today, and the second vowel in the word ''about'' was pronounced as the word ''boot'' is today. The Great Vowel Shift explains many irregularities in spelling since English retains many spellings from Middle English, and it also explains why English vowel letters have very different pronunciations from the same letters in other languages.{{sfn|Lass|2000}}{{sfn|Görlach|1991|pp=66–70}} | |||

| ==Geographical distribution== | |||

| {{See also| List of countries by English-speaking population}} | |||

| ] | |||

| English began to rise in prestige, relative to Norman French, during the reign of ]. Around 1430, the ] in ] began using English in its ]s, and a new standard form of Middle English, known as ], developed from the dialects of London and the ]. In 1476, ] introduced the ] to England and began publishing the first printed books in London, expanding the influence of this form of English.{{sfn|Nevalainen|Tieken-Boon van Ostade|2006|pages=274–79}} Literature from the Early Modern period includes the works of ] and the ] commissioned by ]. Even after the vowel shift the language still sounded different from Modern English: for example, the ]s {{IPA|/kn ɡn sw/}} in ''knight'', ''gnat'', and ''sword'' were still pronounced. Many of the grammatical features that a modern reader of Shakespeare might find quaint or archaic represent the distinct characteristics of Early Modern English.{{sfn|Cercignani|1981}} | |||

| Approximately 375 million people speak English as their first language.<ref>Curtis, Andy. ''Color, Race, And English Language Teaching: Shades of Meaning''. 2006, page 192.</ref> English today is probably the third largest language by number of native speakers, after ] and ].<ref name = "ethnologue"></ref><ref name = "CIA World Factbook">, Field Listing — Languages (World).</ref> However, when combining native and non-native speakers it is probably the most commonly spoken language in the world, though possibly second to a combination of the ]s (depending on whether or not distinctions in the latter are classified as "languages" or "dialects").<ref name = "Languages of the World">, Comrie (1998), Weber (1997), and the Summer Institute for Linguistics (SIL) 1999 Ethnologue Survey. Available at </ref><ref name=Mair>{{cite journal|url=http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp029_chinese_dialect.pdf|format=PDF|journal=Sino-Platonic Papers|last=Mair|first=Victor H.|authorlink=Victor H. Mair|title=What Is a Chinese "Dialect/Topolect"? Reflections on Some Key Sino-English Linguistic Terms|year=1991}}</ref> | |||

| In the 1611 ] of the Bible, written in Early Modern English, Matthew 8:20 says, "The Foxes haue holes and the birds of the ayre haue nests."{{sfn|Lass|2006|pp=46–47}} This exemplifies the loss of case and its effects on sentence structure (replacement with subject–verb–object word order, and the use of ''of'' instead of the non-possessive genitive), and the introduction of loanwords from French (''ayre'') and word replacements (''bird'' originally meaning "nestling" had replaced OE ''fugol'').{{sfn|Lass|2006|pp=46–47}} | |||

| Estimates that include ] speakers vary greatly from 470 million to over a billion depending on how ] or mastery is defined and measured.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://columbia.tfd.com/English+language |title=English language |accessdate=2007-03-26 |year=2005 |publisher=Columbia University Press }}</ref><ref>{{dead link|date=April 2010}}</ref> Linguistics professor ] calculates that non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.<ref>{{Cite book | last = Crystal | first = David | author-link = David Crystal | title = English as a Global Language | edition = 2nd | place = | publisher = Cambridge University Press | page = 69 | year = 2003 | url = http://books.google.com/?id=d6jPAKxTHRYC | isbn = 9780521530323}}, cited in | |||

| {{Cite journal | last = Power | first = Carla | title = Not the Queen's English | journal = Newsweek | date = 7 March 2005 | url = http://www.newsweek.com/id/49022}}</ref> | |||

| === Spread of Modern English === | |||

| The countries with the highest populations of native English speakers are, in descending order: ] (215 million),<ref name="US speakers">{{cite web|url=http://www.census.gov/prod/2005pubs/06statab/pop.pdf|title=U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2003, Section 1 Population|format=PDF|publisher=U.S. Census Bureau|pages=59 pages}} Table 47 gives the figure of 214,809,000 for those five years old and over who speak exclusively English at home. Based on the American Community Survey, these results exclude those living communally (such as college dormitories, institutions, and group homes), and by definition exclude native English speakers who speak more than one language at home.</ref> ] (61 million),<ref name="Crystal">{{cite web|url=http://www.cambridge.org/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=0521530334 |title=The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language, Second Edition, Crystal, David; Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, , Census 2006, ].</ref> ] (15.5 million),<ref name="Australia speakers"> Main Language Spoken at Home. The figure is the number of people who only speak English at home.</ref> Nigeria (4 million),<ref>Figures are for speakers of ], an English-based pidgin or creole. Ihemere gives a range of roughly 3 to 5 million native speakers; the midpoint of the range is used in the table. Ihemere, Kelechukwu Uchechukwu. 2006. "" ''Nordic Journal of African Studies'' 15(3): 296–313.</ref> Ireland (3.8 million),<ref name="Crystal" /> South Africa (3.7 million),<ref name="SA speakers">, page 15 (Table 2.5), 2001 Census, ]</ref> and New Zealand (3.6 million) 2006 Census.<ref>{{cite web |title=About people, Language spoken |url=http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006-census-data/classification-counts-tables/about-people/language-spoken.aspx |publisher=] |date=2006 census |accessdate=2009-09-28}} (links to Microsoft Excel files)</ref> | |||

| By the late 18th century, the ] had spread English through its colonies and geopolitical dominance. Commerce, science and technology, diplomacy, art, and formal education all contributed to English becoming the first truly global language. English also facilitated worldwide international communication.{{sfn|How English evolved into a global language|2010}}{{sfn|The Routes of English}} English was adopted in parts of North America, parts of Africa, Oceania, and many other regions. When they obtained political independence, some of the newly independent ]s that had multiple ]s opted to continue using English as the official language to avoid the political and other difficulties inherent in promoting any one indigenous language above the others.{{sfn|Romaine|2006|p=586}}{{sfn|Mufwene|2006|p=614}}{{sfn|Northrup|2013|pp=81–86}} In the 20th century the growing economic and cultural influence of the United States and its status as a superpower following the Second World War has, along with worldwide broadcasting in English by the ]<ref>{{cite book |last=Baker |first=Colin |title=Encyclopedia of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YgtSqB9oqDIC&pg=PA311 |date=1998 |page=311 |publisher=Multilingual Matters |isbn=978-1-85359-362-8 |access-date=27 August 2017 |archive-date=6 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231106204829/https://books.google.com/books?id=YgtSqB9oqDIC&pg=PA311 |url-status=live}}</ref> and other broadcasters, caused the language to spread across the planet much faster.{{sfn|Graddol|2006}}{{sfn|Crystal|2003a}} In the 21st century, English is more widely spoken and written than any language has ever been.{{sfn|McCrum|MacNeil|Cran|2003|pp=9–10}} | |||

| As Modern English developed, explicit norms for standard usage were published, and spread through official media such as public education and state-sponsored publications. In 1755, ] published his '']'', which introduced standard spellings of words and usage norms. In 1828, ] published the '']'' to try to establish a norm for speaking and writing American English that was independent of the British standard. Within Britain, non-standard or lower class dialect features were increasingly stigmatised, leading to the quick spread of the prestige varieties among the middle classes.{{sfn|Romaine|1999|pp=1–56}} | |||

| Countries such as the Philippines, Jamaica and Nigeria also have millions of native speakers of ] ranging from an ] to a more standard version of English. Of those nations where English is spoken as a second language, India has the most such speakers (']'). Crystal claims that, combining native and non-native speakers, India now has more people who speak or understand English than any other country in the world.<ref>, Crystal, David; Guardian Weekly: Friday 19 November 2004.</ref><ref>Yong Zhao; Keith P. Campbell (1995). "English in China". World Englishes 14 (3): 377–390. Hong Kong contributes an additional 2.5 million speakers (1996 by-census).</ref> | |||

| In modern English, the loss of grammatical case is almost complete (it is now only found in pronouns, such as ''he'' and ''him'', ''she'' and ''her'', ''who'' and ''whom''), and SVO word order is mostly fixed.{{sfn|Romaine|1999|pp=1–56}} Some changes, such as the use of ], have become universalised. (Earlier English did not use the word "do" as a general auxiliary as Modern English does; at first it was only used in question constructions, and even then was not obligatory.{{sfn|Romaine|1999|p=2|ps=: "Other changes such as the spread and regularisation of do support began in the thirteenth century and were more or less complete in the nineteenth. Although do coexisted with the simple verb forms in negative statements from the early ninth century, obligatoriness was not complete until the nineteenth. The increasing use of do periphrasis coincides with the fixing of SVO word order. Not surprisingly, do is first widely used in interrogatives, where the word order is disrupted, and then later spread to negatives."}} Now, do-support with the verb ''have'' is becoming increasingly standardised.) The use of progressive forms in ''-ing'', appears to be spreading to new constructions, and forms such as ''had been being built'' are becoming more common. Regularisation of irregular forms also slowly continues (e.g. ''dreamed'' instead of ''dreamt''), and analytical alternatives to inflectional forms are becoming more common (e.g. ''more polite'' instead of ''politer''). British English is also undergoing change under the influence of American English, fuelled by the strong presence of American English in the media and the prestige associated with the United States as a world power.{{sfn|Leech|Hundt|Mair|Smith|2009|pp=18–19}}{{sfn|Mair|Leech|2006}}{{sfn|Mair|2006}} | |||

| ===Countries in order of total speakers=== | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" style="text-align:center;" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Rank !! Country !! Total !! Percent of population !! First language !! As an additional language !! Population !! class="unsortable" | Comment | |||

| |- | |||

| |1|| ] ||251,388,301||96%||215,423,557||35,964,744||262,375,152||<small>Source: US Census 2000: , Table 1. Figure for second language speakers are respondents who reported they do not speak English at home but know it "very well" or "well". Note: figures are for population age 5 and older</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| |2|| ] ||125,344,736||12%||226,449||86,125,221 ''second'' language speakers.<br /> 38,993,066 ''third'' language speakers ||1,028,737,436||<small>Figures include both those who speak English as a ''second language'' and those who speak it as a ''third language''. 2001 figures.<ref>Table C-17: Population by Bilingualism and trilingualism, 2001 Census of India </ref><ref>Tropf, Herbert S. 2004. | |||

| . Siemens AG, Munich</ref> The figures include English ''speakers'', but not English ''users''.<ref>For the distinction between "English Speakers" and "English Users", see: TESOL-India (Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages). Their article explains the difference between the 350 million number mentioned in a previous version of this Misplaced Pages article and a more plausible 90 million number: {{bquote|Misplaced Pages's India estimate of 350 million includes two categories - "English Speakers" and "English Users". The distinction between the Speakers and Users is that Users only know how to read English words while Speakers know how to read English, understand spoken English as well as form their own sentences to converse in English. The distinction becomes clear when you consider the China numbers. China has over 200~350 million users that can read English words but, as anyone can see on the streets of China, only handful of million who are English speakers.}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| |3|| ] ||79,000,000||53%||4,000,000||>75,000,000||148,000,000||Figures are for speakers of ], an English-based pidgin or creole. Ihemere gives a range of roughly 3 to 5 million native speakers; the midpoint of the range is used in the table. Ihemere, Kelechukwu Uchechukwu. 2006. "" ''Nordic Journal of African Studies'' 15(3): 296–313. | |||

| |- | |||

| |4|| ] ||59,600,000||98%||58,100,000||1,500,000||60,000,000||<small>Source: Crystal (2005), p. 109.</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| |5|| ] ||48,800,000||58%<ref name = "EthnoPhil" />||3,427,000<ref name = "EthnoPhil">{{cite web|url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_country.asp?name=PH |title=Ethnologue report for Philippines |publisher=Ethnologue.com |date= |accessdate=2010-01-02}}</ref>||43,974,000||84,566,000||<small>Total speakers: Census 2000, . 63.71% of the 66.7 million people aged 5 years or more could speak English. Native speakers: Census 1995, as quoted by Andrew González in , Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 19 (5&6), 487–525. (1998). ] lists 3.4 million native speakers with 52% of the population speaking it as a additional language.<ref name = "EthnoPhil" /></small> | |||

| |- | |||

| |6|| ] ||25,246,220||85%||17,694,830||7,551,390||29,639,030||<small>Source: 2001 Census – and . The native speakers figure comprises 122,660 people with both French and English as a mother tongue, plus 17,572,170 people with English and not French as a mother tongue.</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| |7|| ] ||18,172,989|| 92% ||15,581,329||2,591,660||19,855,288||<small>Source: 2006 Census.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.censusdata.abs.gov.au/ABSNavigation/prenav/ViewData?action=404&documentproductno=0&documenttype=Details&order=1&tabname=Details&areacode=0&issue=2006&producttype=Census%20Tables&javascript=true&textversion=false&navmapdisplayed=true&breadcrumb=TLPD&&collection=Census&period=2006&productlabel=Proficiency%20in%20Spoken%20English/Language%20by%20Age%20-%20Time%20Series%20Statistics%20(1996,%202001,%202006%20Census%20Years)&producttype=Census%20Tables&method=Place%20of%20Usual%20Residence&topic=Cultural%20& |title=Australian Bureau of Statistics |publisher=Censusdata.abs.gov.au |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> The figure shown in the first language English speakers column is actually the number of Australian residents who speak only English at home. The additional language column shows the number of other residents who claim to speak English "well" or "very well". Another 5% of residents did not state their home language or English proficiency.</small> | |||

| |- | |||

| | colspan="8" | <small>Note: Total = First language + Other language; Percentage = Total / Population</small> | |||

| |} | |||

| == Geographical distribution == | |||

| ===Countries where English is a major language=== | |||

| {{See also|List of countries and territories where English is an official language|List of countries by English-speaking population|English-speaking world}} | |||

| English is the primary language in Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, ], the Bahamas, Barbados, ], Bermuda, the ], the British Virgin Islands, ], the ], the ], ], Grenada, Guam, ], Guyana, ] , The ], ], Jersey, Montserrat, ], ], ], ], ], ], Singapore, ], ], ], the ] and the ]. | |||

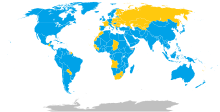

| ] | |||

| [[File:Detailed SVG map of the Anglophone world.svg|thumb| | |||

| {{legend|#045a8d|Majority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#0674b6|Co-official and majority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#439dd4|Official but minority native language}} | |||

| {{legend|#9bbae1|Secondary language: spoken as a second language by more than 20% of the population, ''de facto'' working language of government, language of instruction in education, etc.}} | |||

| ]] | |||

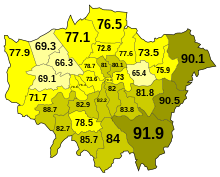

| ], and ], according to the 2016–2021 five-year ]]] | |||

| ] 2019 in Europe:<ref name="b783">{{cite web | title=EF English Proficiency Index 2019 | url=https://www.ef.com/assetscdn/WIBIwq6RdJvcD9bc8RMd/cefcom-epi-site/reports/2019/ef-epi-2019-english.pdf |access-date=15 August 2024}} (pp. 6–7).</ref> | |||

| {{legend|#407294|"Very High Proficiency" (score 63.07–70.27)}} | |||

| {{legend|#5A857D|"High Proficiency" (score 58.26–61.86)}} | |||

| {{legend|#9DBB88|"Moderate Proficiency" (score 52.50–57.38)}} | |||

| {{legend|#E7CB5B|"Low Proficiency" (score 48.69–52.39)}} | |||

| {{legend|#F47B4B|"Very Low Proficiency" (score 40.87–48.19)}} | |||

| {{legend|#c0c0c0|Not included in report}}]] | |||

| {{as of|2016}}, 400 million people spoke English as their ], and 1.1 billion spoke it as a secondary language.<ref>{{cite web|title=Which countries are best at English as a second language?|url=https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/which-countries-are-best-at-english-as-a-second-language-4d24c8c8-6cf6-4067-a753-4c82b4bc865b|publisher=World Economic Forum |first1=Keith |last1=Breene |date=15 November 2019 |access-date=29 November 2016|archive-date=25 November 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161125144549/https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/11/which-countries-are-best-at-english-as-a-second-language-4d24c8c8-6cf6-4067-a753-4c82b4bc865b/|url-status=live}}</ref> English is the ]. English is spoken by communities on every continent and on islands in all the major oceans.{{sfn|Crystal|2003b|p=106}} | |||

| The countries where English is spoken can be grouped into different categories according to how English is used in each country. The "inner circle"{{sfn|Svartvik|Leech|2006|p=2}} countries with many native speakers of English share an international standard of written English and jointly influence speech norms for English around the world. English does not belong to just one country, and it does not belong solely to descendants of English settlers. English is an official language of countries populated by few descendants of native speakers of English. It has also become by far the most important language of international communication when people who share no native language meet anywhere in the world. | |||

| In some countries where English is not the most spoken language, it is an official language; these countries include Botswana, Cameroon, Dominica, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, ], Ghana, India, Kenya, Kiribati, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malta, the Marshall Islands, Mauritius, Namibia, Nigeria, Pakistan, ], Papua New Guinea, the Philippines (]), Rwanda, Saint Lucia, Samoa, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, the Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, the Sudan, Swaziland, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. | |||

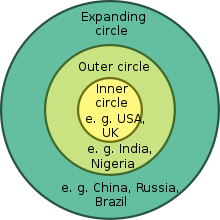

| === Three circles of English-speaking countries === | |||

| It is also one of the 11 official languages that are given equal status in South Africa (]). English is also the official language in current ] of Australia (], ] and ]) and of the United States (], ], ], ], and the ]),<ref>{{Cite book | |||

| ] residents for whom English was their primary language as of 2021]] | |||

| |url=http://books.google.com/?id=vyQDYqz2kFsC&pg=RA1-PA62&lpg=RA1-PA62&dq=%22puerto+rico%22+official+language+1993 | |||

| ]'s ''Three Circles of English'']] | |||

| |title=Puerto Rico: Culture, Politics, and Identity | |||

| The Indian linguist ] distinguished countries where English is spoken with a ].{{sfn|Svartvik|Leech|2006|p=2}} In his model, | |||

| |author=Nancy Morris | |||

| * the "inner circle" countries have large communities of native speakers of English, | |||

| |year=1995 | |||

| * "outer circle" countries have small communities of native speakers of English but widespread use of English as a second language in education or broadcasting or for local official purposes, and | |||

| |publisher=Praeger/Greenwood | |||

| * "expanding circle" countries are countries where many people learn English as a foreign language. | |||

| |isbn=0275952282 | |||

| |page=62}}</ref> and the former British colony of ]. (See ] for more details.) | |||

| Kachru based his model on the history of how English spread in different countries, how users acquire English, and the range of uses English has in each country. The three circles change membership over time.{{sfn|Kachru|2006|p=196}} | |||

| English is not an official language in either the United States or the United Kingdom.<ref>, National Virtual Translation Center, 2006.</ref><ref>, Official Language Research{{ndash}} United Kingdom.</ref> Although the United States federal government has no official languages, English has been given official status by 30 of the 50 state governments.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.us-english.org/inc/official/states.asp |title=U.S. English, Inc |publisher=Us-english.org |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> Although falling short of official status, English is also an important language in several former colonies and ]s of the United Kingdom, such as Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Malaysia, and the United Arab Emirates. English is not an official language of Israel, but is taken as a required second language at all Jewish and Arab schools and therefore widly spoken.<ref>, Language Policy Research Center</ref> | |||

| Countries with large communities of native speakers of English (the inner circle) include Britain, the United States, Australia, Canada, Ireland, and New Zealand, where the majority speaks English, and South Africa, where a significant minority speaks English. The countries with the most native English speakers are, in descending order, the ] (at least 231 million),{{sfn|Ryan|2013|loc=Table 1}} the ] (60 million),{{sfn|Office for National Statistics|2013|loc=Key Points}}{{sfn|National Records of Scotland|2013}}{{sfn|Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency|2012|loc=Table KS207NI: Main Language}} ] (19 million),{{sfn|Statistics Canada|2014}} ] (at least 17 million),{{sfn|Australian Bureau of Statistics|2013}} ] (4.8 million),{{sfn|Statistics South Africa|2012|loc=Table 2.5 Population by first language spoken and province (number)}} ] (4.2 million), and ] (3.7 million).{{sfn|Statistics New Zealand|2014}} In these countries, children of native speakers learn English from their parents, and local people who speak other languages and new immigrants learn English to communicate in their neighbourhoods and workplaces.{{sfn|Bao|2006|p=377}} The inner-circle countries provide the base from which English spreads to other countries in the world.{{sfn|Kachru|2006|p=196}} | |||

| ===English as a global language=== | |||

| {{See also|English in computing|International English|World language}} | |||

| Because English is so widely spoken, it has often been referred to as a "]", the '']'' of the modern era,<ref name = "Graddol"/> and while it is not an official language in most countries, it is currently the language most often taught as a ]. Some linguists believe that it is no longer the exclusive cultural property of "native English speakers", but is rather a language that is absorbing aspects of cultures worldwide as it continues to grow.<ref name = "Graddol"/> It is, by international treaty, the official language for aerial and maritime communications.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.imo.org/Safety/index.asp?topic_id=357 |title=International Maritime Organization |publisher=Imo.org |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> English is an official language of the ] and many other international organisations, including the ]. | |||

| Estimates of the numbers of ] and foreign-language English speakers vary greatly from 470 million to more than 1 billion, depending on how proficiency is defined.{{sfn|Crystal|2003b|pp=108–109}} Linguist ] estimates that non-native speakers now outnumber native speakers by a ratio of 3 to 1.{{sfn|Crystal|2003a|p=69}} In Kachru's three-circles model, the "outer circle" countries are countries such as the ],{{sfn|Rubino|2006}} ],{{sfn|Patrick|2006a}} ], ], ],{{sfn|Lim|Ansaldo|2006}} ] and ]{{sfn|Connell|2006}}{{sfn|Schneider|2007}} with a much smaller proportion of native speakers of English but much use of English as a second language for education, government, or domestic business, and its routine use for school instruction and official interactions with the government.{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|p=5}} | |||

| English is the language most often studied as a foreign language in the European Union, by 89% of schoolchildren, ahead of French at 32%, while the perception of the usefulness of foreign languages amongst Europeans is 68% in favour of English ahead of 25% for French<ref name="srv06"> by ], in website</ref> Among some non-English speaking EU countries, a large percentage of the adult population can converse in English - in particular: 85% in Sweden, 83% in Denmark, 79% in the Netherlands, 66% in Luxembourg and over 50% in Finland, Slovenia, Austria, Belgium, and Germany.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ec.europa.eu/public_opinion/archives/ebs/ebs_237.en.pdf |title=Microsoft Word - SPECIAL NOTE Europeans and languagesEN 20050922.doc |format=PDF |date= |accessdate=2010-04-21}}</ref> | |||

| Those countries have millions of native speakers of ] ranging from an ] to a more standard version of English. They have many more speakers of English who acquire English as they grow up through day-to-day use and listening to broadcasting, especially if they attend schools where English is the medium of instruction. Varieties of English learned by non-native speakers born to English-speaking parents may be influenced, especially in their grammar, by the other languages spoken by those learners.{{sfn|Bao|2006|p=377}} Most of those varieties of English include words little used by native speakers of English in the inner-circle countries,{{sfn|Bao|2006|p=377}} and they may show grammatical and phonological differences from inner-circle varieties as well. The standard English of the inner-circle countries is often taken as a norm for use of English in the outer-circle countries.{{sfn|Bao|2006|p=377}} | |||

| Books, magazines, and newspapers written in English are available in many countries around the world, and English is the most commonly used language in the sciences<ref name="Graddol"/> with ] reporting as early as 1997 that 95% of its articles were written in English, even though only half of them came from authors in English-speaking countries. | |||

| In the three-circles model, countries such as Poland, China, Brazil, Germany, Japan, Indonesia, Egypt, and other countries where English is taught as a foreign language, make up the "expanding circle".{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|p=4}} The distinctions between English as a first language, as a second language, and as a foreign language are often debatable and may change in particular countries over time.{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|p=5}} For example, in the ] and some other countries of Europe, knowledge of English as a second language is nearly universal, with over 80 percent of the population able to use it,{{sfn|European Commission|2012}} and thus English is routinely used to communicate with foreigners and often in higher education. In these countries, although English is not used for government business, its widespread use puts them at the boundary between the "outer circle" and "expanding circle". English is unusual among world languages in how many of its users are not native speakers but speakers of English as a second or foreign language.{{sfn|Kachru|2006|p=197}} | |||

| The impact of the English language globally has sometimes had a large impact on other languages, leading to ] and even ]<ref>David Crystal (2000) Language Death, Preface; viii, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge</ref> and to claims of "]".<ref name="one"/> English itself is now open to ] as multiple ] feed back into the language as a whole.<ref name="one">Jambor, Paul Z. , Journal of English as an International Language, April 2007 - Volume 1, pages 103-123 (Accessed in 2007)</ref> For this reason, the 'English language is forever evolving' <ref>Albert C. Baugh & Thomas Cable (1993), ''A history of the English language'', page 50, Fourth Edition, Routledge, London</ref>. | |||

| Many users of English in the expanding circle use it to communicate with other people from the expanding circle, so that interaction with native speakers of English plays no part in their decision to use the language.{{sfn|Kachru|2006|p=198}} Non-native varieties of English are widely used for international communication, and speakers of one such variety often encounter features of other varieties.{{sfn|Bao|2006}} Very often today a conversation in English anywhere in the world may include no native speakers of English at all, even while including speakers from several different countries. This is particularly true of the shared vocabulary of mathematics and the sciences.{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|p=7}} | |||

| ===Dialects and regional varieties=== | |||

| {{Main| List of dialects of the English language}} | |||

| The expansion of the British Empire and—since ]—the influence of the United States have spread English throughout the globe.<ref name="Graddol"/> Because of that global spread, English has developed a host of ] and English-based ]s and ]s. | |||

| === Pluricentric English === | |||

| Two educated native dialects of English have wide acceptance as standards in much of the world—one based on educated southern British and the other based on educated Midwestern American. The former is sometimes called BBC (or the Queen's) English, and it may be noticeable by its preference for "]"; it typifies the ], which is the standard for the teaching of English to speakers of other languages in Europe, Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and other areas influenced either by the British Commonwealth or by a desire not to be identified with the United States. The latter dialect, ], which is spread over most of the United States and much of Canada, is more typically the model for the American continents and areas (such as the Philippines) that have had either close association with the United States, or a desire to be so identified. | |||

| English is a ], which means that no one national authority sets the standard for use of the language.{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|p=2}}{{sfn|Romaine|1999}}{{sfn|Baugh|Cable|2002}}{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|pp=8–9}} Spoken English, including English used in broadcasting, generally follows national pronunciation standards that are established by custom rather than by regulation. International broadcasters are usually identifiable as coming from one country rather than another through their ]s,{{sfn|Trudgill|2006}} but newsreader scripts are also composed largely in international ]. The norms of standard written English are maintained purely by the consensus of educated English speakers around the world, without any oversight by any government or international organisation.{{sfn|Ammon|2008|pp=1537–1539}} | |||

| American listeners readily understand most British broadcasting, and British listeners readily understand most American broadcasting. Most English speakers around the world can understand radio programmes, television programmes, and films from many parts of the English-speaking world.{{sfn|Svartvik|Leech|2006|p=122}} Both standard and non-standard varieties of English can include both formal or informal styles, distinguished by word choice and syntax and use both technical and non-technical registers.{{sfn|Trudgill|Hannah|2008|pp=5–6}} | |||

| Aside from those two major dialects, there are numerous other ] of English, which include, in most cases, several subvarieties, such as ], ] and ] within ]; ] within ]; and ] ("Ebonics") and ] within ]. English is a ], without a central language authority like France's ]; and therefore no one variety is considered "correct" or "incorrect" except in terms of the expectations of the particular audience to which the language is directed. | |||

| The settlement history of the English-speaking inner circle countries outside Britain helped level dialect distinctions and produce ] forms of English in South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand.{{sfn|Deumert|2006|p=130}} The majority of immigrants to the United States without British ancestry rapidly adopted English after arrival. Now the majority of the United States population are monolingual English speakers.{{sfn|Ryan|2013|loc=Table 1}}{{sfn|Deumert|2006|p=131}} | |||

| ] has its origins in early Northern Middle English<ref>Aitken, A. J. and McArthur, T. Eds. (1979) ''Languages of Scotland''. Edinburgh,Chambers. p.87</ref> and developed and changed during its history with influence from other sources, but following the ] a process of ] began, whereby successive generations adopted more and more features from Standard English, causing dialectalisation. Whether it is now a separate language or a ] of English better described as ] is in dispute, although the UK government now accepts Scots as a ] and has recognised it as such under the ].<ref>''</ref> There are a number of regional dialects of Scots, and pronunciation, grammar and lexis of the traditional forms differ, sometimes substantially, from other varieties of English. | |||

| *] has no official languages at the federal or state level.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Ward |first=Rowena |date=2019 |title='National' and 'Official' Languages Across the Independent Asia-Pacific |journal=Journal of Multidisciplinary International Studies |volume=16 |issue=1/2 |pages=83–4 |doi=10.5130/pjmis.v16i1-2.6510 | doi-access=free |quote=The use of English in Australia is one example of both a de facto national and official language: it is widely used and is the language of government and the courts, but has never been legally designated as the country's official language.}}</ref> | |||

| English speakers have many different ], which often signal the speaker's native dialect or language. For the more distinctive characteristics of regional accents, see ], and for the more distinctive characteristics of regional dialects, see ]. Within England, variation is now largely confined to pronunciation rather than grammar or vocabulary. At the time of the ], grammar and vocabulary differed across the country, but a process of ''lexical attrition'' has led most of this variation to die out.<ref>Peter Trudgill, ''The Dialects of England'' 2nd edition, page 125, Blackwell, Oxford, 2002</ref> | |||

| *In ], English and French share an ] at the federal level.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.gc.ca/web/article-eng.do?m=/index&nid=480459|title=40 Years of the Official Languages Act|publisher=Department of Justice Canada|access-date=March 24, 2013}}{{Dead link|date=June 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/O-3.01/page-1.html|title=Official Languages Act - 1985, c. 31 (4th Supp.)|work=Act current to July 11th, 2010|publisher=Department of Justice|access-date=August 15, 2010|archive-date=January 5, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110105194649/http://laws.justice.gc.ca/eng/O-3.01/page-1.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> English has official or co-official status in six provinces and three territories, while three provinces have none and Quebec's only official language is French.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.legisquebec.gouv.qc.ca/en/tdm/cs/C-11| title = Charter of the French language| last = | first = | date = 26 March 2024| website = Légis Québec| publisher = Québec Official Publisher| access-date = 5 June 2024| quote = French is the official language of Québec. Only French has that status.}}</ref> | |||

| *English is the official second language of ], while Irish is the first.<ref>{{cite web| url = https://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/cons/en/html#part2| title = Article 8 of the Constitution of Ireland| last = | first = | date = January 2020| website = Irish Statute Book| publisher =| access-date = 5 June 2024| quote = 1 The Irish language as the national language is the first official language. 2 The English language is recognised as a second official language.}}</ref> | |||

| *While ] is majority English-speaking, its two official languages are ]<ref>{{cite web |title=Maori Language Act 1987 |url=http://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1987/0176/latest/DLM124116.html |accessdate=18 December 2011 }}</ref> and ].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://tvnz.co.nz/view/page/488120/696482 |title=Recognition for sign language |date=6 April 2006 |work=] |access-date=30 October 2011}}</ref> | |||

| *The ] does not have an official language. In Wales and Northern Ireland, English is co-official alongside ]<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Huws |first1=Catrin Fflur |title=The Welsh Language Act 1993: A Measure of Success? |journal=Language Policy |date=June 2006 |volume=5 |issue=2 |pages=141–160 |doi=10.1007/s10993-006-9000-0 }}</ref> and ]<ref>{{Cite news |date=2022-10-26 |title=Irish language and Ulster Scots bill clears final hurdle in Parliament |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-northern-ireland-63402597 |access-date=2022-10-27}}</ref> respectively. Neither Scotland nor England have an official language. | |||