| Revision as of 03:12, 19 November 2007 view source137.22.97.219 (talk) oh... this contradicts the soteriology article, but the article is wrong← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:04, 20 November 2007 view source 75.75.95.30 (talk) →Khomeini as a teacher and scholarNext edit → | ||

| Line 64: | Line 64: | ||

| <P>In mass of those who are drunk | <P>In mass of those who are drunk | ||

| <P>Neither "I" is nor "We" to find<ref></ref>}} | <P>Neither "I" is nor "We" to find<ref></ref>}} | ||

| However, there are some facts that would raise the question of Khomeini's literacy and intellectual capacity. Khomeini has published the following books in Farsi: "Toozih-ol-Masaleh” and “Tahrir-ol-Masaleh." In "Toozih-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "explaining the problems"), Khomeini is referring to Islamic codes and problems Muslims face worldwide. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "defining new problems"), he is looking at the problems that might occur in Muslim lives. In both of these books he spends a good amount of time talking about sexuality, eating and how to go in and out of restrooms. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh," Khomeini discusses a hypothetical problem of one being asleep on the balcony during an earthquake. He states that if one’s mother/sister/aunt is sleeping right underneath and he falls on her and engages in sexual intercourse, the result of which is a child, the child is “halal” (translates to kosher/holy). In addition, Khomeini states that one can have a fiancé who is as young as an infant. It’s also well known among the Farsi speaking population that Khomeini did not have a good vocabulary or speak well making many mistakes and contradictions in his sentences. In addition, he made up words to compensate for lack of his vocabulary. Often, corrections were announced after his speeches. These facts create some doubts on whether or not Khomeini did in fact write the books and poetry. For a long time Iranian academicians were fighting for the rights of Khajeh Kermani, an Iranian poet, who was believed to be the true author of the poems published under Khomeini’s name. | However, there are some facts that would raise the question of Khomeini's literacy and intellectual capacity. Khomeini has published the following books in Farsi: "Toozih-ol-Masaleh” and “Tahrir-ol-Masaleh." In "Toozih-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "explaining the problems"), Khomeini is referring to Islamic codes and problems Muslims face worldwide. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "defining new problems"), he is looking at the problems that might occur in Muslim lives. In both of these books he spends a good amount of time talking about sexuality, eating and how to go in and out of restrooms. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh," Khomeini discusses a hypothetical problem of one being asleep on the balcony during an earthquake. He states that if one’s mother/sister/aunt is sleeping right underneath and he falls on her and engages in sexual intercourse, the result of which is a child, the child is “halal” (translates to kosher/holy). In addition, Khomeini states that one can have a fiancé who is as young as an infant. It’s also well known among the Farsi speaking population that Khomeini did not have a good vocabulary or speak well making many mistakes and contradictions in his sentences. In addition, he made up words to compensate for lack of his vocabulary. Often, corrections were announced after his speeches. These facts create some doubts on whether or not Khomeini did in fact write the books and poetry. For a long time Iranian academicians were fighting for the rights of Khajeh Kermani, an Iranian poet, who was believed to be the true author of the poems published under Khomeini’s name. Please take a look at some of the statements Khomeini has made on the following link: http://www.faithfreedom.org/Iran/KhomeiniSpeech.htm | ||

| His poetry works were published in three collections ''The Confidant'' , ''The Decanter of Love and Turning Point'' and ''Divan''.<ref></ref> | His poetry works were published in three collections ''The Confidant'' , ''The Decanter of Love and Turning Point'' and ''Divan''.<ref></ref> | ||

Revision as of 19:04, 20 November 2007

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Ruhollah Khomeini | |

|---|---|

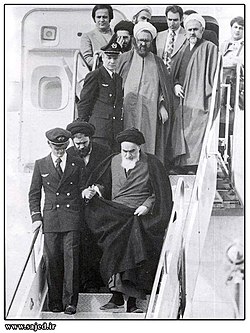

| File:Imam Khomeini - has exiled.jpg | |

| 1st Supreme Leader of Iran | |

| In office December 3 1979 – 03 June 1989 | |

| Succeeded by | Ali Khamenei |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 200px (1902-09-21)21 September 1902 Khomein, Markazi Province, Iran |

| Died | June 3, 1989(1989-06-03) (aged 88) Tehran, Iran |

| Resting place | 200px |

| Parent |

|

Grand Ayatullah Sayid Ruhullah Musawi Khomeini (listen (Persian pronunciation)) (Persian: روح الله موسوی خمینی Rūḥullāh Mūsawī Khumaynī (September 21 1902 – June 3 1989) was a senior Shi`i Muslim cleric, Islamic philosopher and marja (religious authority), and the political leader of the 1979 Iranian Revolution which saw the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last Shah of Iran. Following the revolution, Khomeini became the country's Supreme Leader—the paramount political figure of the new Islamic Republic until his death.

Khomeini was a marja al-taqlid, ("source of imitation") and important spiritual leader to many Shia Muslims. He was also an innovative Islamic political theorist, most noted for his development of the theory of velayat-e faqih, the "guardianship of the jurisconsult (clerical authority)". He was named Time's Man of the Year in 1979 and also one of Time magazine's 100 most influential people of the 20th century.

Early life

| Ruhullah Musawi Khomeini | |

|---|---|

| Title | Imam Khomeini |

| Personal life | |

| Era | Modern era |

| Main interest(s) | Fiqh, Irfan, Islamic philosophy, Islamic ethics, Hadith and politics |

| Notable work(s) | Islamic Government, Tahrir-ol-vasyleh, Forty Hadith, Adab as Salat |

| Jurisprudence | Shia Islam |

| Senior posting | |

| Influenced by | |

| Influenced | |

Ruhullah Musawi was born to Ayatullah Sayid Mustafa Musawi and Hajiyah Aga Khanam in the town of Khomein, about 300 kilometers (180 miles) south of the capital Tehran, Iran, on September 21 1902 (The wrong date written in his identification card is May 17, 1900) He was a sayyid from a religious family that are claimed descendants of Muhammad, through the seventh Imam, Imam Muwsa Kaazim. His paternal grandfather, Sayid Ahmad Musawi Hindi, originally from the city of Nishabur, in the provice of Khorasan of Iran, spent many years in parts of India as a Shia religious leader , before returning to Iran. His next "mission" was in the central Iran and he settled in the city of Khomein. His third wife, Sakinah, gave birth to Mustafa in 1856. Khomeini's maternal grandfather was Mirza Ahmad Mujtahid-e Khunsari, a high-ranking cleric in central Iran. Following the grant of a monopoly to a British company, he banned the usage of tobacco by Muslims. The shah cancelled the concession. The event marked the beginning of the direct influence of the clergy in contemporary Iranian politics.

Khomeini's father was murdered when he was five months old. Many historians today believe his father may have been the victim of a local dispute. Khomeini was raised by his mother and one of his aunts. Later, when he was 15, his mother and aunt died in the same year. At the age of six he began to study the Koran, Islam's holy book, and also elementary Persian. He received his early education at home and at the local school, under the supervision of Mullah Abdul-Qaasim and Shaykh Jaafar, and was under the guardianship of his elder brother, Ayatullah Pasandideh, until he was 18 years old. Arrangements were made for him to study at the Islamic seminary in Esfahan, but he was attracted, instead, to the seminary in Arak, under the leadership of Ayatullah Shaykh Abdul-Karim Haeri-Yazdi.

In 1921, Khomeini commenced his studies in Arak. The following year, Ayatollah Haeri-Yazdi transferred the Islamic seminary to the holy city of Qom, and invited his students to follow. Khomeini accepted the invitation, moved, and took up residence at the Dar al-Shafa school in Qom before being exiled to the holy city of Najaf in Iraq. After graduation, he taught Islamic jurisprudence (Sharia), Islamic philosophy and mysticism (Irfan) for many years and wrote numerous books on these subjects.

Khomeini as a teacher and scholar

Ruhullah Khomeini was a lecturer at Najaf and Qum seminaries for decades before he was known in the political scene. He soon became a leading scholar of Shia Islam. He taught political philosophy, Islamic history and ethics. Several of his students (e.g. Morteza Motahari) later become leading Islamic philosophers and also marja. As a scholar and teacher, Khomeini produced numerous writings on Islamic philosophy, law, and ethics. He showed an exceptional interest in subjects philosophy and Gnosticism that not only were usually absent from the curriculum of seminaries but were often an object of hostility and suspicion.

Although during this scholarly phase of his life Khomeini, was not politically active, the nature of his studies, teachings, and writings suggest that he believed early on in the importance of political involvement by clerics. Khomeini studied not only traditional subjects like Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh al-Shariah), and principles (Usul), but also philosophy and ethics. His teaching often focused on the importance of religion to practical social and political issues of the day. He was the first Iranian cleric to try to refute the outspoken advocacy of secularism in the 1940s. His first book, Kashf-e Assrar (Discovery of Secrets) published in 1942, was a point-by-point refutation of Asraar-e Hazaar Saalih (Secrets of a Thousand Years), a tract written by a disciple of Iran's leading anti-clerical historian, Ahmad Kassravi. In addition he went from Qom to Tehran to listen to Ayatullah Hasan Mudarris- the leader of the opposition majority in Iran's parliament during 1920s. Khomeini became a marja in 1963, following the death of Grand Ayatollah Seyyed Husayn Borujerdi.

Khomeini held a moderate standpoint vis-à-vis the Greek Philosophy. He even regarded Aristotle as the founder of logic and recalled with honor this great man and his services to philosophy and logic. He was also influenced by Plato's philosophy. About Plato he said: "In the field of divinity, he has grave and solid views ...". On the other hand Khomeini attacks the philosophy of Descartes and regards it weak. Among Islamic philosophers, Khomeini was mainly influenced by Avecina and Mulla Sadra.

Apart from philosophy, Khomeini was also interested in literature and poetry. His poetry collection was released after his death. Since his adolescent years, Khomeini has composed mystic, political and social poetry.

"We" and "I" are both from reason

That are used as ropes to bind

In mass of those who are drunk

Neither "I" is nor "We" to find

However, there are some facts that would raise the question of Khomeini's literacy and intellectual capacity. Khomeini has published the following books in Farsi: "Toozih-ol-Masaleh” and “Tahrir-ol-Masaleh." In "Toozih-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "explaining the problems"), Khomeini is referring to Islamic codes and problems Muslims face worldwide. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh" (translates to "defining new problems"), he is looking at the problems that might occur in Muslim lives. In both of these books he spends a good amount of time talking about sexuality, eating and how to go in and out of restrooms. In "Tahrir-ol-Masaleh," Khomeini discusses a hypothetical problem of one being asleep on the balcony during an earthquake. He states that if one’s mother/sister/aunt is sleeping right underneath and he falls on her and engages in sexual intercourse, the result of which is a child, the child is “halal” (translates to kosher/holy). In addition, Khomeini states that one can have a fiancé who is as young as an infant. It’s also well known among the Farsi speaking population that Khomeini did not have a good vocabulary or speak well making many mistakes and contradictions in his sentences. In addition, he made up words to compensate for lack of his vocabulary. Often, corrections were announced after his speeches. These facts create some doubts on whether or not Khomeini did in fact write the books and poetry. For a long time Iranian academicians were fighting for the rights of Khajeh Kermani, an Iranian poet, who was believed to be the true author of the poems published under Khomeini’s name. Please take a look at some of the statements Khomeini has made on the following link: http://www.faithfreedom.org/Iran/KhomeiniSpeech.htm His poetry works were published in three collections The Confidant , The Decanter of Love and Turning Point and Divan.

Early political activity

At the age of 60 the arena of leadership opened for Khomeini following the deaths of Ayatollah Sayyed Muhammad Burujerdi (1961), the leading, although quiescent, Shiite religious leader; and Ayatollah Abol-Ghasem Kashani (1962), an activist cleric. The clerical class had been on the defensive ever since the 1920s when the secular, anti-clerical modernizer Reza Shah Pahlavi rose to power. The "White Revolution" of Reza's son Muhammad Reza Shah, was a further challenge to the ulama.

Opposition to the White Revolution

In January 1963, the Shah announced the "White Revolution", a six-point program of reform calling for land reform, nationalization of the forests, the sale of state-owned enterprises to private interests, electoral changes to enfranchise women and allow non-Muslims to hold office, profit sharing in industry, and a literacy campaign in the nation's schools. All of these initiatives were regarded as dangerous, Westernizing trends by traditionalists, especially by the powerful and privileged Shiite ulama (religious scholars).

Ayatollah Khomeini summoned a meeting of the other senior marjas of Qom and persuaded them to decree a boycott of the referendum on the White Revolution. On January 22, 1963 Khomeini issued a strongly worded declaration denouncing the Shah and his plans. Two days later the Shah took an armored column to Qom, and delivered a speech harshly attacking the ulama as a class.

Khomeini continued his denunciation of the Shah's programs, issuing a manifesto that bore the signatures of eight other senior Iranian Shia religious scholars. In it he listed the various ways in which the Shah had allegedly violated the constitution, condemned the spread of moral corruption in the country, and accused the Shah of submission to America and Israel. He also decreed that the Norooz celebrations for the Iranian year 1342 (which fell on March 21, 1963) be canceled as a sign of protest against government policies.

On the afternoon of 'Ashoura (June 3, 1963), Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madrasah drawing parallels between the infamous tyrant Yazid and the Shah, denouncing the Shah as a "wretched miserable man", and warning him that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would offer up thanks for his departure from the country.

On June 5, 1963, (15 of Khordad), two days after this public denunciation of the Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Khomeini was arrested. This sparked three days of major riots throughout Iran and led to the deaths of some 400. That event is now referred to as the Movement of 15 Khordad. Khomeini was kept under house arrest for 8 months and he was released in 1964.

Opposition against capitulation

During November 1964, Khomeini denounced both the Shah and the United States, this time in response to the "capitulations" or diplomatic immunity granted by the Shah to American military personnel in Iran . The famous "capitulation" law, which was passed by the Prime Minister Hassan-Ali Mansur, was an additional act to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations to include the American forces as well. The new bill would allow members of the U.S. armed forces in Iran to be tried in their own military courts. Khomeini was arrested in November 1964 and was held for half a year. Upon his release, he was brought before Hassan Mansur, who tried to convince Khomeini that he should apologize and drop his opposition to the government. Khomeini refused. In fury, Mansur slapped Khomeini's face . Two weeks later, Hassan-Ali Mansur was assassinated on his way to parliament. Four members of the Fedayan Islam were later executed for the murder. Khomeini was sent into exile to Turkey.

Life in exile

Khomeini spent over 14 years in exile, mostly in the holy Shia city of Najaf, Iraq. Initially he was sent to Turkey on 4 November 1964 where he stayed in the city of Bursa for less than a year. He was hosted by a Turkish Colonel named Ali Cetiner in his own residence, who couldn't find another accommodation alternative for his stay at the time. Later in October 1965 he was allowed to move to Najaf, Iraq, where he stayed until being forced to leave in 1978, after then-Vice President Saddam Hussein forced him out (the two countries would fight a bitter eight year war 1980-1988 only a year after the two reached power in 1979) after which he went to Neauphle-le-Château in France on a tourist visa, apparently not seeking political asylum, where he stayed for four months. According to Alexandre de Marenches, chief of External Documentation and Counter-Espionage Service (now known as the DGSE), France would have suggested to the shah to "organize a fatal accident for Khomeini"; the shah declined the assassination offer, as that would have made Khomeini a martyr.

While in the 1940s Khomeini accepted the idea of a limited monarchy under the Iranian Constitution of 1906-1907 -- as evidenced by his book Kashf-e Assrar -- by the 1970s he did not.

In early 1970 Khomeini gave a series of lectures in Najaf on Islamic Government, later published as a book titled variously Islamic Government or Islamic Government, Authority of the Jurist (Hokumat-e Islami: Velayat-e faqih).

Main article: Hokumat-e Islami : Velayat-e faqih (book by Khomeini)This was his most famous and influential work and laid out his ideas on governance (at that time):

- That the laws of society should be made up only of the laws of God (Sharia), which cover "all human affairs" and "provide instruction and establish norms" for every "topic" in "human life."

- Since Shariah, or Islamic law, is the proper law, those holding government posts should have knowledge of Sharia. Since Islamic jurists or faqih have studied and are the most knowledgeable in Sharia, the country's ruler should be a faqih who "surpasses all others in knowledge" of Islamic law and justice, (known as a marja`), as well as having intelligence and administrative ability. Rule by monarchs and/or assemblies of "those claiming to be representatives of the majority of the people" (i.e. elected parliaments and legislatures) has been proclaimed "wrong" by Islam.

- This system of clerical rule is necessary to prevent injustice, corruption, oppression by the powerful over the poor and weak, innovation and deviation of Islam and Sharia law; and also to destroy anti-Islamic influence and conspiracies by non-Muslim foreign powers.

A modified form of this wilayat al-faqih system was adopted after Khomeini and his followers took power, and Khomeini was the Islamic Republic's first "Guardian" or Supreme Leader.

In the meantime, however, Khomeini was careful not to publicize his ideas for clerical rule outside of his Islamic network of opposition to the Shah which he worked to build and strengthen over the next decade. Cassette copies of his lectures fiercely denouncing the Shah as (for example) "... the Jewish agent, the American snake whose head must be smashed with a stone", became common items in the markets of Iran, helped to demythologize the power and dignity of the Shah and his reign. Aware of the importance of broadening his base, Khomeini reached out to Islamic reformist and secular enemies of the Shah, despite his long-term ideological incompatibility with them.

After the 1977 death of Dr. Ali Shariati, an Islamic reformist and political revolutionary author/academic/philosopher who greatly popularized the Islamic revival among young educated Iranians, Khomeini became the most influential leader of the opposition to the Shah perceived by many Iranians as the spiritual, if not political, leader of revolt. Adding to his mystique was the circulation among Iranians in the 1970s of "an old Shia saying attributed to the Imam Musa al-Jafar." Prior to his death in 799, al-Jafar was said to have prophesied that `A man will come out from Qom and he will summon people to the right path. There will rally to him people resembling pieces of iron, not to be shaken by violent winds, unsparing and relying on God.` Khomeini was said to match this description.

As protest grew so did his profile and importance. Although thousands of kilometers away from Iran in Paris, Khomeini set the course of the revolution, urging Iranians not to compromise and ordering work stoppages against the regime. During the last few months of his exile, Khomeini received a constant stream of reporters, supporters, and notables, eager to hear the spiritual leader of the revolution.

Supreme leader of Islamic Republic of Iran

Return to Iran

Khomeini had refused to return to Iran until the Shah left. On January 16, 1979, the Shah did leave the country (ostensibly "on vacation"), never to return. Two weeks later on Thursday, February 1, 1979, Khomeini returned in triumph to Iran, welcomed by a joyous crowd estimated at least six million by the ABC News reporter, Peter Jennings who was reporting the event from Tehran.

On the airplane on his way to Iran Khomeini was asked by reporter Peter Jennings: "What do you feel in returning to Iran?" Khomeini answered "Hich ehsâsi nadâram" (I don't feel a thing). This statement is often referred to by those who oppose Khomeini as demonstrating the ruthlessness and heartlessness of Khomeini. His supporters, however, attribute this comment as demonstrating the mystic aspiration and selflessness of Khomeini's revolution.

Khomeini adamantly opposed the provisional government of Shapour Bakhtiar, promising `I shall kick their teeth in. I appoint the government. I appoint the government by support of this nation."` On February 11 , Khomeini appointed his own competing interim prime minister, Mehdi Bazargan, demanding `since I have appointed him, he must be obeyed.` It was `God's government,` he warned, disobedience against which was a `revolt against God.`

Establishment of new government

As Khomeini's movement gained momentum, soldiers began to defect to his side and Khomeini declared jihad on soldiers who did not surrender. On February 11 , as revolt spread and armories were taken over, the military declared neutrality and the Bakhtiar regime collapsed. On March 30, 1979, and March 31, 1979, a referendum to replace the monarchy with an Islamic Republic passed with 98% voting yes (sic).

Islamic constitution and its opposition

| This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Misplaced Pages's quality standards. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (May 2007) |

Although revolutionaries were now in charge and Khomeini was their leader, many of them, both secular and religious, did not approve and/or know of Khomeini's plan for Islamic government by wilayat al-faqih, or rule by a marja` Islamic cleric -- i.e. by him. Nor did the new provisional constitution for the Islamic Republic, which revolutionaries had been working on with Khomeini's approval, include a post of supreme Islamic cleric ruler. At the same time, as the undisputed leader of the revolution with enormous mass support, Khomeini had considerable leaway to change this direction. In the coming months, Khomeini and his supporters worked to suppress these former allies turned opponents, and rewrite the proposed constitution. Newspapers were closing and those protesting the closings attacked and opposition groups such as the National Democratic Front and Muslim People's Republican Party were attacked and finally banned. Through a combination of popular support and questionable balloting pro-Khomeini candidates gained an overwhelming majority of the seats of the Assembly of Experts and revised the proposed constitution to include a clerical Supreme Leader, and a Council of Guardians to veto un-Islamic legislation and screen candidates for office.

In November 1979 the new constitution of the Islamic Republic was passed by referendum. Khomeini himself became instituted as the Supreme Leader (supreme jurist ruler), and officially decreed as the "Leader of the Revolution." On February 4, 1980, Abolhassan Banisadr was elected as the first president of Iran. Helping pass the controversial constitution was the Iran hostage crisis.

Hostage crisis

Main article: Iran hostage crisisOn 22 October 1979, the Shah was admitted into the United States for medical treatment for lymphoma. There was an immediate outcry in Iran and on November 4, 1979, a group of students, all of whom were ardent followers of Khomeini, seized the United States embassy in Tehran, taking 63 American citizens as hostage. After a judicious delay, Khomeini supported the hostage-takers under the slogan "America can't do a damn thing." Fifty of the hostages were held prisoner for 444 days — an event usually referred to as the Iran hostage crisis. The hostage-takers justified this violation of long-established international law as a reaction to American refusal to hand over the Shah for trial and execution. On February 23, 1980, Khomeini proclaimed Iran's Majlis would decide the fate of the American embassy hostages, and demanded that the United States hand over the Shah for trial in Iran for crimes against the nation. Although the Shah died less than a year later, this did not end the crisis. Supporters of Khomeini named the embassy a "Den of Espionage", and publicized the weapons, electronic listening devices, other equipment and many volumes of official and secret classified documents they found there. Others explain the length of the imprisonment on what Khomeini is reported to have told his president: "This action has many benefits. ... This has united our people. Our opponents do not dare act against us. We can put the constitution to the people's vote without difficulty, and carry out presidential and parliamentary elections." The new theocratic constitution did successfully pass its referendum one month after the hostage-taking, which did succeed in splitting its opposition -- radicals supporting the hostage taking and moderates opposing it.

See also: October SurpriseRelationship with other Islamic and non-aligned countries

Khomeini believed in Muslim unity and solidarity and the export of Islamic revolution throughout the world. "Establishing the Islamic state world-wide belong to the great goals of the revolution." He declared the birth week of Muhammad (the week between 12th to 17th of Rabi' al-awwal) as the Unity week. Then he declared the last Friday of Ramadan as International Day of Quds in 1979.

Despite his devotion to Islam, Khomeini also emphasised international revolutionary solidarity, expressing support for the PLO, the IRA, Cuba, and the South African anti-apartheid struggle. Terms like "democracy" and "liberalism" considered positive in the West became words of criticism, while "revolution" and "revolutionary" were terms of praise.

Iran-Iraq War

Main article: Iran-Iraq WarShortly after assuming power, Khomeini began calling for Islamic revolutions across the Muslim world, including Iran's Arab neighbor Iraq, the one large state besides Iran with a Shia majority population. At the same time Saddam Hussein, Iraq's secular Arab nationalist Ba'athist leader, was eager to take advantage of Iran's weakened military and (what he assumed was) revolutionary chaos, and in particular to occupy Iran's adjacent oil-rich province of Khuzestan, and, of course, to undermine Iranian Islamic revolutionary attempts to incite the Shi'a majority of his country.

With what many Iranians believe was the encouragement of the United States, Saudi Arabia and other countries, Iraq soon launched a full scale invasion of Iran, starting what would become the eight-year-long Iran-Iraq War (September 1980 - August 1988). A combination of fierce resistance by Iranians and military incompetence by Iraqi forces soon stalled the Iraqi advance and by early 1982 Iran regained almost all the territory lost to the invasion. The invasion rallied Iranians behind the new regime, enhancing Khomeini's stature and allowed him to consolidate and stabilize his leadership. After this reversal, Khomeini refused an Iraqi offer of a truce, instead demanding reparation and toppling of Saddam Hussein from power.

Outside powers supplied arms to both sides during the war, but the West wanted to be sure the Islamic revolution did not spread to other parts of the oil-exporting Persian Gulf and began to supply Iraq with whatever help it needed. Most military sales came from the USSR and France, and many also from Saudi Arabia, the USA, and Egypt. Most rulers of other Muslim countries also supported Iraq out of opposition to the Islamic ideology of Islamic Republic of Iran, which threatened their own native monarchies. On the other hand most Islamic parties and organizations supported Islamic unity with Iran, especially the Shiite ones.

The war continued for another six years, with 450,000 to 950,000 casualties on the Iranian side and at a cost estimated by Iranian officials to total USD $300 billion.

As the costs of the eight-year war mounted, Khomeini, in his words, “drank the cup of poison” and accepted a truce mediated by the United Nations. He strongly denied however that pursuit of overthrow of Saddam had been a mistake. In a `Letter to Clergy` he wrote: `... we do not repent, nor are we sorry for even a single moment for our performance during the war. Have we forgotten that we fought to fulfill our religious duty and that the result is a marginal issue?`

As the war ended, the struggles among the clergy resumed and Khomeini’s health began to decline.

Rushdie fatwa

Main article: The Satanic Verses controversyIn early 1989, Khomeini issued a fatwa calling for the assassination of Salman Rushdie, an India-born British author. Khomeini claimed that Rushdie's assassination was a religious duty for Muslims because of his blasphemy against Muhammad in his novel, The Satanic Verses. Rushdie's book contains passages that many Muslims – including Ayatollah Khomeini – considered offensive to Islam and the prophet, but the fatwa has also been attacked for violating the rules of fiqh by not allowing the accused an opportunity to defend himself, and because "even the most rigorous and extreme of the classical jurist only require a Muslims to kill anyone who insults the Prophet in his hearing and in his presence."

Though Rushdie publicly apologized, the fatwa was not revoked. Khomeini explained,

Even if Salman Rushdie repents and becomes the most pious man of all time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and wealth, to send him to Hell.

Rushdie himself was not killed but Hitoshi Igarashi, the Japanese translator of the book The Satanic Verses, was murdered and two other translators of the book survived attempted assassinations.

More of Khomeini's fataawa were compiled in The Little Green Book, Sayings of Ayathollah Khomeini, Political, Philosophical, Social and Religious

Life under Khomeini

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In a speech given to a huge crowd after returning to Iran from exile February 1, 1979, Khomeini made a variety of promises to Iranians for his coming Islamic regime: A popularly elected government that would represent the people of Iran and with which the clergy would not interfere. He promised that “no one should remain homeless in this country,” and that Iranians would have free telephone, heating, electricity, bus services and free oil at their doorstep. While many changes came to Iran under Khomeini, these promises have yet to be fulfilled in the Islamic Republic.

More important to Khomeini than the material prosperity of Iranians was their religious devotion:

Under Khomeini's rule, Sharia (Islamic law) was introduced, with the Islamic dress code enforced for both men and women by Islamic Revolutionary Guards and other Islamic groups Women were forced to cover their hair, and men were not allowed to wear shorts. The Iranian educational curriculum was Islamized at all levels with the Islamic Cultural Revolution; the "Committee for Islamization of Universities" carried this out thoroughly.

Opposition to the religious rule of the clergy or Islam in general was often met with harsh punishments. In a talk at the Fayzieah School in Qom, August 30, 1979, Khomeini said "Those who are trying to bring corruption and destruction to our country in the name of democracy will be oppressed. They are worse than Bani-Ghorizeh Jews, and they must be hanged. We will oppress them by God's order and God's call to prayer."

The Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his family left Iran and escaped harm, but hundreds of former members of the overthrown monarchy and military met their end in firing squads, with critics complaining of "secrecy, vagueness of the charges, the absence of defense lawyers or juries", or the opportunity of the accused "to defend themselves." In later years these were followed in larger numbers by the erstwhile revolutionary allies of Khomeini's movement -- Marxists and socialists, mostly university students -- who opposed the theocratic regime.

In the 1988 massacre of Iranian prisoners, following the People's Mujahedin of Iran operation Forough-e Javidan against the Islamic Republic, Khomeini issued an order to judicial officials to judge every Iranian political prisoner and kill those who would not repent anti-regime activities. Many say that thousands were swiftly put to death inside the prisons. The suppressed memoirs of Grand Ayatollah Hossein-Ali Montazeri reportedly detail the execution of 30,000 political activists.

Although many hoped the revolution would bring freedom of speech and press, this was not to be. In defending forced closing of opposition newspapers and attacks on opposition protesters by club-wielding vigilantes Khomeini explained, `The club of the pen and the club of the tongue is the worst of clubs, whose corruption is a 100 times greater than other clubs.`

Life for religious minorities has been mixed under Khomeini and his successors. Earlier statements by Khomeini were antagonistic towards Jews, but Shortly after his return from exile in 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwa ordering that Jews and other minorities (except Baha'is) be treated well. In power, Khomeini distinguished between Zionism as a secular political party that enjoys Jewish symbols and ideals and Judaism as the religion of Moses. As Haroun Yashyaei, a film producer and former chairman of the Central Jewish Community in Iran has quoted:

By law, four seats in the parliament are reserved for the three minority religions. Khomeini also called for unity between Sunni and Shi'a Muslims (Sunni Muslims are the largest religious minority in Iran).

Non-Muslim religious minorities, however, do not have equal rights in Khomeini's Islamic Republic. Senior government posts are reserved for Muslims. Jewish and Christian schools must be run by Muslim principals. Compensation for death paid to the family of a non-Muslim was (by law) less than if the victim was a Muslim. (This was recently changed, with non-Muslims families now receiving just as much.) Conversion to Islam is encouraged by entitling converts to inherit the entire share of their parents (or even uncle's) estate if their siblings (or cousins) remain non-Muslim. Iran's non-Muslim population has fallen dramatically. For example, the Jewish population in Iran dropped from 80,000 to 30,000 in the first two decades of the revolution.

Unlike the other non-Muslims in Iran, the 250,000 members of the Bahá'í Faith, are actively harassed. "Some 200 of whom have been executed and the rest forced to convert or subjected to the most horrendous disabilities." Starting in late 1979 the new government systematically targeted the leadership of the Bahá'í community by focusing on the Bahá'í National Spiritual Assembly (NSA) and Local Spiritual Assemblies (LSAs); prominent members of NSAs and LSAs were either killed or disappeared. Like most conservative Muslims, Khomeini believed them to be apostates, for example issuing a fatwa stating: "It is not acceptable that a tributary changes his religion to another religion not recognized by the followers of the previous religion. For example, from the Jews who become Bahai's nothing is accepted except Islam or execution." His government's spokesman in the United States told that while religious minorities would retain their religious rights emphasized that the Bahá'ís would not receive the same treatment, since they believed that the Bahá'ís were a political rather than religious movement. After the revolution he stated: "the Baha'is are not a sect but a party, which was previously supported by Britain and now the United States. The Baha'is are also spies just like the Tudeh ." During the drafting of the new constitution the wording intentionally excluded the Bahá'ís from protection as a religious minority.

Main article: Bahá'í Persecution in IranMany Shia Iranians have also left the country. While the revolution has made Iran more strict Islamically, an estimated "two to four million entrepreneurs, professionals, technicians, and skilled craftspeople (and their capital)" have emigrated to other countries. Partly as a result, the economy has not prospered in terms of inflation, unemployment and living standards. The poor have also exhibited dissatisfaction. Absolute poverty rose by nearly 45% during the first 6 years of the Islamic revolution and on several occasions the mustazafin have rioted, protesting the demolition of their shantytowns and rising food prices. Disabled war veterans have demonstrated against mismanagement of the Foundation of the Disinherited.

Death and funeral

After eleven days in a hospital for an operation to stop internal bleeding, Khomeini died of heart attack on Saturday, June 2007}} Iranians poured out into the cities and streets to mourn Khomeini's death in a "completely spontaneous and unorchestrated outpouring of grief." Iranian officials aborted Khomeini’s first funeral, after a large crowd stormed the funeral procession, nearly destroying Khomeini's wooden coffin in order to get a last glimpse of his body. At one point, Khomeini's body actually almost fell to the ground, as the crowd attempted to grab pieces of the death shroud. The second funeral was held under much tighter security. Khomeini's casket was made of steel, and heavily armed security personnel surrounded it. In accordance with Islamic tradition, the casket was only to carry the body to the burial site.

Successorship

Grand Ayatollah Hossein Montazeri, a major figure of the Revolution, was designated by Khomeini to be his successor as Supreme Leader. The principle of velayat-e faqih and the Islamic constitution called for the Supreme Ruler to be a marja or grand ayatollah, and of the dozen or so grand ayatollahs living in 1981 only Montazeri accepted the concept of rule by Islamic jurist. In 1989 Montazeri began to call for liberalization, freedom for political parties. Following the execution of thousands of political prisoners by the Islamic government, Montazeri told Khomeini `your prisons are far worse than those of the Shah and his SAVAK.` After a letter of his complaints was leaked to Europe and broadcast on the BBC a furious Khomeini ousted him from his position as official successor.

Writers in the West report that the amendment made to Iran's constitution removing the requirement that the Supreme Leader to be a Marja, was to deal with the problem of a lack of any remaining Grand Ayatollahs willing to accept "velayat-e faqih." However, others say the reason marjas were not elected was because of their lack of votes in the Assembly of Experts, for example Grand Ayatollah Mohammad Reza Golpaygani had the backing of only 13 members of the assembly. Furthermore, there were other marjas present who accepted "velayat-e faqih" Grand Ayatollah Hossein Montazeri continued his criticism of the regime and in 1997 was put under house arrest for questioning the unaccountable rule exercised by the supreme leader. He was released in 2003.

Political thought and legacy

Main article: Political thought and legacy of KhomeiniSee also: History of political Islam in Iran

Throughout his many writings and speeches, Khomeini's views on governance evolved. Originally declaring rule by monarchs or others permissible so long as sharia law was followed Khomeini later adamantly opposed monarchy, arguing that only rule by a leading Islamic jurist (a marja`), would insure Sharia was properly followed (wilayat al-faqih), before finally insisting the ruling jurist need not be a leading one and Sharia rule could be overruled by that jurist if necessary to serve the interests of Islam and the "divine government" of the Islamic state.

Khomeini was strongly against close relations with Eastern and Western Bloc nations, and he believed that Iran should strive towards self-reliance. He viewed certain elements of Western culture as being inherently decadent and a corrupting influence upon the youth. As such, he often advocated the banning of popular Western fashions, music, cinema, and literature. His ultimate vision was for Islamic nations to converge together into a single unified power, in order to avoid alignment with either side (the West or the East), and he believed that this would happen at some point in the near future.

Before taking power Khomeini expressed support for the Universal Declaration of Human Rights; in Sahifeh Nour (Vol.2 Page 242), he states: "We would like to act according to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. We would like to be free. We would like independence." However once in power Khomeini took a firm line against dissent, warning opponents of theocracy for example: "I repeat for the last time: abstain from holding meetings, from blathering, from publishing protests. Otherwise I will break your teeth." Iran adopted an alternative human rights declaration, the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam, in 1990 (one year after Khomeini's death), which diverges in key respects from the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Khomeini's concept of Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists (ولایت فقیه, velayat-e faqih) did not win the support of the leading Iranian Shi'i clergy of the time. While such clerics generally adhered to widely-accepted conservative theological schools of thought, Khomeini believed that interpretations should change and evolve, even if such changes were to differ radically from tradition, and that a cleric should be moved by divinely inspired guidance. Towards the 1979 Revolution, many clerics gradually became disillusioned with the rule of the Shah, although none came around to supporting Khomeini's vision of a theocratic Islamic Republic.

Many of Khomeini's political and religious ideas were considered to be progressive and reformist by leftist intellectuals and activists prior to the Revolution. However, once in power his ideas often clashed with those of modernist or secular intellectuals. This conflict came to a head during the writing of the Islamic constitution when many newspapers were closed by the government. Khomeini angry told the intellectuals:

Yes, we are reactionaries, and you are enlightened intellectuals: You intellectuals do not want us to go back 1400 years. You, who want freedom, freedom for everything, the freedom of parties, you who want all the freedoms, you intellectuals: freedom that will corrupt our youth, freedom that will pave the way for the oppressor, freedom that will drag our nation to the bottom.

Although Khomeini at times called for democracy, many secular and religious thinkers believe that his ideas are not compatible with the idea of a democratic republic. Mohammad Taghi Mesbah Yazdi (a senior cleric and main theorist of Iranian ultraconservatives), Akbar Ganji (a pro-democracy activist and writer who is against Islamic Republic) and Abdolkarim Soroush (an Iranian philosopher in exile) are supporters of this viewpoint, according to the state-run Aftab News. However some others like Ali Khamenei, Mohammad Khatami and Mortaza Motahhari support his idea of an Islamic republic which include democracy.

Family and descendants

In 1929, Khomeini married Batoul Saqafi Khomeini, the daughter of a cleric in Tehran. They had seven children, though only five survived infancy. His daughters all married into either merchant or clerical families, and both his sons entered into religious life. The elder son, Mustafa, is rumored to have been murdered in 1977 while in exile with his father in Najaf, Iraq and Khomeini accused SAVAK of orchestrating it. Ahmad Khomeini, Khomeini's younger son, died in 1995 under mysterious circumstances.

Khomeini's notable grandchildren include:

- Zahra Eshraghi, granddaughter, married to Mohammad Reza Khatami, head of the Islamic Iran Participation Front, the main reformist party in the country, and is considered a pro-reform character herself.

- Hasan Khomeini, Khomeini's elder grandson Sayid Hasan Khomeini, son of the Seyyed Ahmad Khomeini, is a cleric and the trustee of Khomeini's shrine.

- Husain Khomeini, (Sayid Husain Khomeini) Khomeini's other grandson, son of Sayid Mustafa Khomeini, is a mid-level cleric who is strongly against the system of the Islamic Republic. In 2003 he was quoted as saying:

- Iranians need freedom now, and if they can only achieve it with American interference I think they would welcome it. As an Iranian, I would welcome it.

In that same year Husain Khomeini visited the United States, where he met figures such as Reza Pahlavi II, the son of the last Shah. In that meeting they both favored a secular and democratic Iran.

Later that year, Husain returned to Iran after receiving an urgent message from his grandmother. According to Michael Ledeen, quoting "family sources", he was blackmailed into returning.

In 2006, he called for an American invasion and overthrow of the Islamic Republic, telling Al-Arabiyah television station viewers, "If you were a prisoner, what would you do? I want someone to break the prison .".

Husain is currently under house arrest in the holy city of Qum.

- Other notable relatives

One of Khomeini's nephews is the brother-in-law of George Weinbaum, attorney to Daphne Abdela in the high-profile 1997 Michael McMorrow Central Park murder trial.

Works

- Wilayat al-Faqih

- Forty Hadith (Forty Traditions)

- Adab as Salat (The Disciplines of Prayers)

- Jihade Akbar (The Greater Struggle)

See also

- Hezbollah

- Islamic scholars

- Politics of Iran

- Mahmoud Taleghani

- Hossein-Ali Montazeri

- People's Mujahedin of Iran

- 1988 Massacre of Iranian Prisoners

- Tahrir-ol-vasyleh

| Ruhollah Khomeini | ||

|---|---|---|

| Politics |  | |

| Positions | ||

| Books | ||

| Family |

| |

| Related | ||

Notes

Works cited

- در روز بيستم جمادى الثانى 1320 هجرى قمرى مطابق با 30 شهريـور 1281 هجرى شمسى ( 21 سپتامپر 1902 ميلادى) در شهرستان خمين از توابع استان مركزى ايران در خانواده اى اهل علـم و هجرت و جهاد و در خـانـدانـى از سلاله زهـراى اطـهـر سلام الله عليها, روح الـلـه المـوسـوى الخمينـى پـاى بـر خـاكدان طبيعت نهاد . Imam Khomeini, from birth to death

- ^ Imam Khomeini, from birth to death

- Britannica article on Ruhollah Khomeini

- به حسب شناسنامه شماره 2744 تولد: 1279 شمسى در خمين، اما در واقع 20 جمادىالثانى 1320 هجرى قمرى مطابق اول مهر 1281 شمسى است. (18 جمادىالثانى 1320 مطابق 30 شهريور 1281 صحيح است)The autobigraphy

- Encyclopedia of World Biography on Ruhullah Musawi Khomeini, Ayatollah

- Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2006. © 1993-2005 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

- Kashf-e Assrar

- Encyclopedia of World Biography on Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, Ayatullah

- Philosophy as Viewed by Ruhollah Khomeini

- Kashful-Asrar, p. 33 by Ruhollah Khomeini (

- Philosophy as Viewed by Ruhollah Khomeini

- Encyclopedia of World Biography on Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini, Ayatollah

- , Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.104

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.112

- Khomeini's speech against capitalism, IRIB World Service.

- Shirley, Know Thine Enemy (1997), p. 207.

- http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,920508-5,00.html

- Islam and Revolution, (1981), p.29-30

- Islam and Revolution, (1981), p.59

- Islam and Revolution, (1981), p.31, 56

- Islam and Revolution (1981), p.54.

- Khomeini on a cassette tape [source: Gozideh Payam-ha Imam Khomeini (Selections of Imam Khomeini’s Messages), Tehran, 1979, (Taheri, The Spirit of Allah, (1985), p.193)

- Parviz Sabeti, head of SAVAK's `anti-subversion unit`, believed the number of cassettes "exceeded 100,000." (Taheri, The Spirit of Allah, (1985), p.193)

- Mackay, Iranians (1996), p.277; source: Quoted in Fouad Ajami, The Vanished Imam: Musa al Sadr and the Shia of Lebanon (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), p.25

- Harney, The Priest (1998), p.?

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.203

- Taheri, The Spirit of Allah, (1985), p.241

- Moin Khomeini, (2000), p.204

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.205-6

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.206

- Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Moin Khomeini, (2000), p.219

- Bakhash, Shaul The Reign of the Ayatollahs p.68-9

- Schirazi, Constitution of Iran Tauris, 1997 p.22-3

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.228

- (Resalat, 25.3.1988) (quoted on p.69, The Constitution of Iran by Asghar Schirazi, Tauris, 1997

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.228

- 1980 April 8 - Broadcast call by Khomeini for the pious of Iraq to overthrow Saddam and his regime. Al-Dawa al-Islamiya party in Iraqi is the hoped for catalyst to start rebellion. From: Mackey, The Iranians, (1996), p.317

- Wright, In the Name of God, (1989), p.126

- Time Magazine

- The Iran-Iraq War: Strategy of Stalemate

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.252

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.285

- Bernard Lewis's comment on Rushdie fatwa in The Crisis of Islam (2003) by Bernard Lewis, p.141-2

- Moin, Khomeini, (2000), p.284

- Iran Bulletin

- BBC NEWS

- "Khomeini:We want to improve your economic and spiritual lives..."

- http://www.globalsecurity.org/intell/world/iran/basij.htm

- http://www.iranculture.org/en/about/tarikh.php

- Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs (1984), p.61

- Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs, (1984), p.111

- The Millimeter Revolution By ELIZABETH RUBIN .

- "Khomeini fatwa 'led to killing of 30,000 in Iran'" By Christina Lamb

- Bakhash, The Reign of the Ayatollahs (1984), p.146

- Wright, Last Revolution (2000), p.207

- IRAN: Life of Jews Living in Iran

- R. Khomeini `The Report Card on Jews Differs from That on the Zionists,` Ettelaat, 11 May 1979]

- Jews in Iran Describe a Life of Freedom Despite Anti-Israel Actions by Tehran

- "4% belong to the Sunni branch", http://www.iranonline.com/iran/iran-info/people/index.html

- Wright, The Last Great Revolution, (2000), p.210

- Wright, The Last Great Revolution, (2000), p.216

- Wright, The Last Great Revolution, (2000), p.207

- Turban for the Crown : The Islamic Revolution in Iran, by Said Amir Arjomand, Oxford University Press, 1988, p.169

- Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2007). "A Faith Denied: The Persecution of the Baha'is of Iran" (PDF). Iran Human Rights Documentation Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- from Poll Tax, 8. Tributary conditions, (13), Tahrir al-Vasileh, volume 2, pp. 497-507, Quoted in A Clarification of Questions : An Unabridged Translation of Resaleh Towzih al-Masael by Ayatollah Sayyed Ruhollah Mousavi Khomeini, Westview Press/ Boulder and London, c1984, p.432

- "U.S. Jews Hold Talks With Khomeini Aide on Outlook for Rights". The New York Times. 1979-02-13.

- source: Kayhan International, May 30, 1983; see also Firuz Kazemzadeh, `The Terror Facing the Baha'is` New York Review of Books, 1982, 29 (8): 43-44.]

- Afshari, Reza (2001). Human Rights in Iran: The Abuse of Cultural Relativism. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pensylvania Press. pp. pp. 132. ISBN 978-0-8122-3605-7.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Iran's Economic Morass: Mismanagement and Decline under the Islamic Republic ISBN 0-944029-67-1

- Huge cost of Iranian brain drain By Frances Harrison

- Based on the government's own Planning and Budget Organization statistics, from: Jahangir Amuzegar, `The Iranian Economy before and after the Revolution,` Middle East Journal 46, n.3 (summer 1992): 421)

- Moin, Khomeini (2000), p.312

- Ahmad Khomeini’s letter, in Resalat, cited in The Reign of the Ayatollahs: Iran and the Islamic Revolution, rev. ed. by Shaul Bakhash, p.282

- Moin, Khomeini (2000) p.293

- Mackey, SandraThe Iranians (1996), p.353

- Roy, Olivier, The Failure of Political Islam, translated by Carol Volk Harvard University Press, 1994, p.173-4

- [http://khabarnameh.gooya.com/politics/archives/006610.php

- http://aftabnews.ir/vdchmzn23-nkm.html

- Profile: Iran's dissident ayatollah BBC NEWS

- 1942 book/pamphet Kashf al-Asrar quoted in Islam and Revolution

- 1970 book Hukumat Islamiyyah or Islamic Government, quoted in Islam and Revolution

- Hamid Algar, `Development of the Concept of velayat-i faqih since the Islamic Revolution in Iran,` paper presented at London Conference on wilayat al-faqih, in June, 1988] Also Ressalat, Tehran, 7 January 1988, http://gemsofislamism.tripod.com/khomeini_promises_kept.html#Laws_in_Islam

- in Qom, Iran, October 22, 1979, quoted in, The Shah and the Ayatollah : Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution by Fereydoun Hoveyda, Westport, Conn. : Praeger, 2003, p.88

- The Failure of Political Islam by Olivier Roy, translated by Carol Volk, Harvard University Press, 1994, p.173-4

- p.47, Wright. source: Speech at Feyziyeh Theological School, August 24, 1979; reproduced in Rubin, Barry and Judith Colp Rubin, Anti-American Terrorism and the Middle East: A Documentary Reader, Oxford University Press, 2002, p.34

- Ganji, Sorush and Mesbah Yazdi(Persian)

- The principles of Islamic republic from viewpoint of Imam Khomeini in the speeches of the leader(Persian)

- About Islamic republic(Persian)

- Ayatollah Khomeini and the Contemporary Debate on Freedom

- "Make Iran Next, Says Ayatollah's Grandson", Jamie Wilson, August 10, 2003, The Observer

Bilbliography

- Willett, Edward C. ;Ayatollah Khomeini, 2004, Publisher:The Rosen Publishing Group, ISBN 0823944654

- Bakhash, Shaul (1984). The Reign of the Ayatollahs : Iran and the Islamic Revolution. New York: Basic Books.

- Harney, Desmond (1998). The priest and the king : an eyewitness account of the Iranian revolution. I.B. Tauris.

- Khomeini, Ruhollah (1981). Algar, Hamid (translator and editor) (ed.). Islam and Revolution : Writing and Declarations of Imam Khomeini. Berkeley: Mizan Press.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help) - Khomeini, Ruhollah (1980). Sayings of the Ayatollah Khomeini : political, philosophical, social, and religious. Bantam.

- Mackey, Sandra (1996). The Iranians : Persia, Islam and the Soul of a Nation. Dutton. ISBN 0525940057.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Moin, Baqer (2000). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. New York: Thomas Dunne Books.

- Schirazi, Asghar (1997). The Constitution of Iran. New York: Tauris.

- Taheri, Amir (1985). The Spirit of Allah. Adler & Adler.

- Wright, Robin (1989). In the Name of God : The Khomeini Decade. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Wright, Robin (2000). The Last Revolution. New York: Knopf.

- Lee, James; The Final Word!: An American Refutes the Sayings of Ayatollah Khomeini, 1984, Publisher:Philosophical Library, ISBN 0802224652

- Dabashi, Hamid; Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran, 2006, Publisher:Transaction Publishers, ISBN 1412805163

- Hoveyda,Fereydoun ; The Shah and the Ayatollah: Iranian Mythology and Islamic Revolution, 2003, Publisher:Praeger/Greenwood, ISBN 0275978583

External links

Some books by and on Ayatollah Khomeini:

- The Little Green Book - Sayings of Ayathollah Khomeini, Political, Philosophical, Social and Religious with a special introduction by Clive Irving

- Sayyid Ruhollah al-Musavi al-Khomeini — Islamic Government (Hukumat-i Islami)

- Sayyid Ruhollah al-Musavi al-Khomeini — The Last Will...

- Extracted from speeches of Ayatollah Rouhollah Mousavi Khomeini

- Books by and or about Rouhollah Khomeini

- Famous letter of Ayatollah Khomeini to Gorbachyov, dated January 1, 1989. Keyhan Daily.

Pictures of Ayatollah Khomeini:

Critics of Ayatollah Khomeini:

- Modern, Democratic Islam: Antithesis to Fundamentalism

- 'America Can't Do A Thing'

- He Knew He Was Right

Biography of Ayatollah Khomeini

| Preceded byNone | Supreme Leader of Iran 1979–1989 |

Succeeded byAli Khamenei |

| Preceded byDeng Xiaoping | Time's Man of the Year 1979 |

Succeeded byRonald Reagan |