| Revision as of 17:13, 2 December 2007 editElonka (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators70,960 edits Copyediting, removing questionable images← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:24, 2 December 2007 edit undoRenamed user abcedarium (talk | contribs)15,068 edits →Veneration as a saintNext edit → | ||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Infobox_Monarch|name=Louis IX | {{Infobox_Monarch|name=Louis IX | ||

| |title=King of France <small>]</small> | |title=King of France <small>]</small> | ||

| |image=] | |image=] | ||

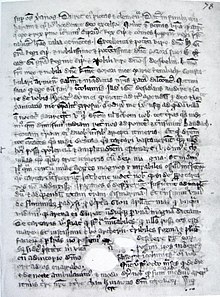

| |caption=Representation of Saint Louis considered to be true to life - Early 14th century statue from the church of ], ], ] | |||

| |caption=16th century painting of St. Louis by Jean de Tillet | |||

| |reign=] ] – ] ] | |reign=] ] – ] ] | ||

| |coronation=] ], ] | |coronation=] ], ] | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

| {{Direct Capetians|louis9}} | {{Direct Capetians|louis9}} | ||

| '''Louis IX''' (] ] – ] ]), commonly '''Saint Louis''', was ] from ] to his death. He was also ] (as Louis II) from ] to ]. Born at ], near ], he was a member of the ] and the son of ] and ]. He is the only ] king of France and consequently there are many places named after him, most notably ] in the |

'''Louis IX''' (] ] – ] ]), commonly '''Saint Louis''', was ] from ] to his death. He was also ] (as Louis II) from ] to ]. Born at ], near ], he was a member of the ] and the son of ] and ]. He is the only ] king of France and consequently there are many places named after him, most notably ]. He established the ]. | ||

| ==Sources== | ==Sources== | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| Louis was eleven years old when his father died on ], ]. He was crowned king the same year in the cathedral at ]. | |||

| ==Assumption of power== | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Because of Louis's youth, his mother, ], ruled France as ] during his minority. No date is given for Louis's assumption of the throne as king in his own right. His contemporaries viewed his reign as co-rule between the king and his mother, though historians generally view the year ] as the year in which Louis ruled as king with his mother assuming a more advisory role. She continued as an important counsellor to the king until her death in ]. | ||

| ⚫ | No date is given for Louis's assumption of the throne as king in his own right. His contemporaries viewed his reign as co-rule between the king and his mother, though historians generally view the year ] as the year in which Louis ruled as king |

||

| On ], ] Louis married ] (] – ], ]), the sister of ], the wife of ]. | On ], ] Louis married ] (] – ], ]), the sister of ], the wife of ]. | ||

| ⚫ | Louis was the elder brother of ] (]–]), whom he created count of ], thus founding the second ] dynasty. The horrific fate of that dynasty in Sicily as a result of the ] evidently did not tarnish Louis's credentials for sainthood. | ||

| ==Crusading== | ==Crusading== | ||

| Louis brought an end to the ] in ] after signing an agreement with Count ] that cleared his father of wrong-doing. ] had been suspected of murdering a preacher on a mission to convert the ]. | |||

| Louis's ] and kindness towards the poor was much celebrated. He went on ] twice, |

Louis's ] and kindness towards the poor was much celebrated. He went on ] twice, in ] (]) and then in ] (]). Both crusades were complete disasters; after initial success in his first attempt, Louis's army of 15,000 men was met by overwhelming resistance from the Egyptian army and people. | ||

| He had begun with the rapid capture of the port of ] in June 1249,<ref>Tyerman, p. 787</ref> an attack which did cause some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan was on his deathbed. But the march from Damietta towards Cairo through the ] went slowly. During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and a sudden power shift took place, as the sultan's slave wife ] set events in motion which were to make her Queen, and eventually place the |

He had begun with the rapid capture of the port of ] in June 1249,<ref>Tyerman, p. 787</ref> an attack which did cause some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan was on his deathbed. But the march from Damietta towards Cairo through the ] went slowly. During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and a sudden power shift took place, as the sultan's slave wife ] set events in motion which were to make her Queen, and eventually place the Egyptian's slave army of the ] in power. On ] ] Louis lost his army at the ] and was captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated, in return for a ransom of 400,000 ''livres tournois'' (at the time France's annual revenue was only about 250,000 ''livres tournois'', so it was necessary to obtain a loan from the Templars), and the surrender of the city of Damietta.<ref>Tyerman, pp. 789-798</ref> | ||

| Following his release from Egyptian captivity, Louis spent four years in the crusader Kingdoms of |

Following his release from Egyptian captivity, Louis spent four years in the crusader Kingdoms of Acre, Caesarea, and Jaffe. Louis used his wealth to assist the crusaders in rebuilding their defenses and conducting diplomacy with the Islamic powers of Syria and Egypt. Upon his departure from Middle East Louis left a significant garrison in the city of Acre for its defense against Islamic attacks. The historic presence of this French garrison in the Middle East was later used as a justification for the French Mandate following the end of the First World War. | ||

| ===Attempted alliances=== | ===Attempted alliances=== | ||

| {{See also|Franco-Mongol alliance}} | {{See also|Franco-Mongol alliance}} | ||

| ], speaking in positive terms about the Mongols.<ref>"Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie", p66</ref> The letter was also shown to Louis IX, who decided to send an envoy to the Mongol court]]Louis exchanged multiple letters and emissaries with ] rulers of the period. After Louis left France |

], speaking in positive terms about the Mongols.<ref>"Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie", p66</ref> The letter was also shown to Louis IX, who decided to send an envoy to the Mongol court]]Saint Louis exchanged multiple letters and emissaries with ] rulers of the period. After Louis left France and disembarked at ] in ], he was first met on December 20, 1248, in ] by two Mongol envoys, ] from ] named David and Marc, bearing a letter from ], the Mongol ruler of ] and ].<ref>{{cite journal|title=The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260 |author=Peter Jackson|journal=The English Historical Review|volume=95|issue=376|date=July 1980|pages=481-513|url=http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0013-8266(198007)95%3A376%3C481%3ATCITHL%3E2.0.CO%3B2-F}}</ref> They communicated a proposal to form an alliance against the Muslim ], whose Caliphate was based in ].<ref>Grousset, p.523</ref> Eljigidei suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, in order to prevent the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces. | ||

| Though at least one historian has criticized Louis as being "naive" in trusting the ambassadors, and Louis himself later admitted that he regretted the decision,<ref>Tyerman, p. 786</ref> Louis sent ], a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan ] in ]. However, Güyük died, from drink, before the emissary arrived at his court, and his widow ] simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis,<ref>Runciman, p.260</ref> demanding that the king pay tribute to the Mongols.<ref>Tyerman, p. 798. "Louis's embassy under Andrew of Longjumeau had returned in 1251 carrying a demand from the Mongol regent, Oghul Qaimush, for annual tribute, not at all what the king had anticipated.</ref> | Though at least one historian has criticized Louis as being "naive" in trusting the ambassadors, and Louis himself later admitted that he regretted the decision,<ref>Tyerman, p. 786</ref> Louis sent ], a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan ] in ]. However, Güyük died, from drink, before the emissary arrived at his court, and his widow ] simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis,<ref>Runciman, p.260</ref> demanding that the king pay tribute to the Mongols.<ref>Tyerman, p. 798. "Louis's embassy under Andrew of Longjumeau had returned in 1251 carrying a demand from the Mongol regent, Oghul Qaimush, for annual tribute, not at all what the king had anticipated.</ref> | ||

| In 1252, Louis attempted an alliance with the Egyptians, for the return of |

In 1252, Louis attempted an alliance with the Egyptians, for the return of Jerusalem if the French assisted with the subduing of Damascus. | ||

| In 1253, Louis tried to seek allies from among both the Ismailian ] and the Mongols.<ref>Runciman, pp. 279-280</ref> Louis had received word that |

In 1253, Louis tried to seek allies from among both the Ismailian ] and the Mongols.<ref>Runciman, pp. 279-280</ref> Louis had received word that the Mongol leader ], son of ], had converted to Christianity,<ref>Runciman, p.380</ref> While in Cyprus, Louis also saw a letter from ], brother of the Armenian ruler ], who, on an embassy to the Mongol court in Karakorum, was describing to the Western ruler a Central Asian realm of oasis with many Christians, generally of the Nestorian rite.<ref>Jean Richard, “Histoire des Croissades”, p. 376</ref> | ||

| Louis dispatched |

Louis dispatched an envoy to the Mongol court in the person of the Franciscan ], who went to visit the Great Khan ] in ]. William entered into a famous competition at the Mongol court, as the khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct, as determined by three judges, one from each faith. The debate drew a large crowd, and as with most Mongol events, a great deal of alcohol was involved. As described by Jack Weatherford in his book ''Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World'': | ||

| {{quote|No side seemed to convince the other of anything. Finally, as the effects of the alcohol became stronger, the Christians gave up trying to persuade anyone with logical arguments, and resorted to singing. The Muslims, who did not sing, responded by loudly reciting the ] in an effort to drown out the Christians, and the Buddhists retreated into silent mediation. At the end of the debate, unable to convert or kill one another, they concluded the way most Mongol celebrations concluded, with everyone simply too drunk to continue.|Jack Weatherford, ''Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World'', p. 173}} | {{quote|No side seemed to convince the other of anything. Finally, as the effects of the alcohol became stronger, the Christians gave up trying to persuade anyone with logical arguments, and resorted to singing. The Muslims, who did not sing, responded by loudly reciting the ] in an effort to drown out the Christians, and the Buddhists retreated into silent mediation. At the end of the debate, unable to convert or kill one another, they concluded the way most Mongol celebrations concluded, with everyone simply too drunk to continue.|Jack Weatherford, ''Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World'', p. 173}} | ||

| Line 64: | Line 65: | ||

| ==Patron of arts and arbiter of Europe== | ==Patron of arts and arbiter of Europe== | ||

| ] | |||

| Louis' patronage of the arts drove much innovation in ] and ], and the style of his court radiated throughout Europe by both the purchase of art objects from Parisian masters for export and by the marriage of the king's daughters and female relatives to foreign husbands and their subsequent introduction of Parisian models elsewhere. Louis' personal chapel, the '']'' in ], was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis most likely ordered the production of the ], a masterpiece of medieval painting. | Louis' patronage of the arts drove much innovation in ] and ], and the style of his court radiated throughout Europe by both the purchase of art objects from Parisian masters for export and by the marriage of the king's daughters and female relatives to foreign husbands and their subsequent introduction of Parisian models elsewhere. Louis' personal chapel, the '']'' in ], was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis most likely ordered the production of the ], a masterpiece of medieval painting. | ||

| Saint Louis ruled during the so-called "golden century of Saint Louis", when the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. The king of France was regarded as a ''primus inter pares'' among the kings and rulers of |

Saint Louis ruled during the so-called "golden century of Saint Louis", when the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. The king of France was regarded as a ''primus inter pares'' among the kings and rulers of Europe. He commanded the largest army, and ruled the largest and most wealthy kingdom of Europe, a kingdom which was the European center of arts and intellectual thought (]) at the time. For many, King Louis IX embodied the whole of ] in his person. His reputation of saintliness and fairness was already well established while he was alive, and on many occasions he was chosen as an arbiter in the quarrels opposing the rulers of Europe. | ||

| The prestige and respect felt in Europe for King Louis IX was due more to the attraction that his benevolent personality created rather than to military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince. | |||

| ==Religious zeal== | ==Religious zeal== | ||

| ] of ] was bought by Louis IX to ]. It is preserved today in a 19th century reliquary, in ].]] | ] of ] was bought by Louis IX to ]. It is preserved today in a 19th century reliquary, in ].]] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The perception of Louis IX as the exemplary Christian prince was reinforced by his religious zeal. Louis was a devout Catholic, and he built the '']'' ("Holy Chapel"), located within the royal palace complex (now the ]), on the '']'' in the centre of Paris. The ''Sainte Chapelle'', a perfect example of the Rayonnant style of ], was erected as a shrine for the ] and a fragment of the ], precious ]s of the ] of ]. Louis purchased these in ]–] from Emperor ] of the ] of ], for the exorbitant sum of 135,000 ]s (the chapel, on the other hand, cost only 60,000 livres to build). This purchase should be understood in the context of the extreme religious fervor that existed in Europe in the 13th century. The purchase contributed greatly to reinforcing the central position of the king of France in western Christendom, as well as to increasing the renown of Paris, then the largest city of western Europe. During a time when cities and rulers vied for relics, trying to increase their reputation and fame, Louis IX had succeeded in securing the most prized of all relics in his capital. The purchase was thus not only an act of devotion, but also a political gesture: the French monarchy was trying to establish the kingdom of France as the "]." | The perception of Louis IX as the exemplary Christian prince was reinforced by his religious zeal. Saint Louis was a devout Catholic, and he built the '']'' ("Holy Chapel"), located within the royal palace complex (now the ]), on the '']'' in the centre of Paris. The ''Sainte Chapelle'', a perfect example of the Rayonnant style of ], was erected as a shrine for the ] and a fragment of the ], precious ]s of the ] of ]. Louis purchased these in ]–] from Emperor ] of the ] of ], for the exorbitant sum of 135,000 ]s (the chapel, on the other hand, cost only 60,000 livres to build). This purchase should be understood in the context of the extreme religious fervor that existed in Europe in the 13th century. The purchase contributed greatly to reinforcing the central position of the king of France in western Christendom, as well as to increasing the renown of Paris, then the largest city of western Europe. During a time when cities and rulers vied for relics, trying to increase their reputation and fame, Louis IX had succeeded in securing the most prized of all relics in his capital. The purchase was thus not only an act of devotion, but also a political gesture: the French monarchy was trying to establish the kingdom of France as the "]." | ||

| Louis IX took very seriously his mission as "lieutenant of God on Earth," with which he had been invested when he was crowned in ]. Thus, in order to fulfill his duty, he conducted two ]s, and even though they were unsuccessful, they contributed to his prestige. Contemporaries would not have understood if the king of France did not lead a crusade to the ]. In order to finance his first crusade Louis ordered the expulsion of all ] engaged in ]. This action enabled Louis to confiscate the property of expelled Jews for use in his crusade. However, he did not eliminate the debts incurred by Christians. One-third of the debt was forgiven, but the other two-thirds was to be remitted to the royal treasury. Louis also ordered, at the urging of ], the burning of some 12,000 copies of the ] in Paris in 1243. Such legislation against the Talmud, not uncommon in the history of Christendom, was due to medieval courts' concerns that its production and circulation might weaken the faith of Christian individuals and threaten the Christian basis of society, the protection of which was the duty of any Christian monarch.<ref>{{Citation | last =Gigot | first =Francis E. | contribution =Judaism | year =1910 | title =The Catholic Encyclopedia | volume =VIII | place=New York | publisher =Robert Appleton Company | url = http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08399a.htm | accessdate = 2007-08-13}}</ref> | Louis IX took very seriously his mission as "lieutenant of God on Earth," with which he had been invested when he was crowned in ]. Thus, in order to fulfill his duty, he conducted two ]s, and even though they were unsuccessful, they contributed to his prestige. Contemporaries would not have understood if the king of France did not lead a crusade to the ]. In order to finance his first crusade Louis ordered the expulsion of all ] engaged in ]. This action enabled Louis to confiscate the property of expelled Jews for use in his crusade. However, he did not eliminate the debts incurred by Christians. One-third of the debt was forgiven, but the other two-thirds was to be remitted to the royal treasury. Louis also ordered, at the urging of ], the burning of some 12,000 copies of the ] in Paris in 1243. Such legislation against the Talmud, not uncommon in the history of Christendom, was due to medieval courts' concerns that its production and circulation might weaken the faith of Christian individuals and threaten the Christian basis of society, the protection of which was the duty of any Christian monarch.<ref>{{Citation | last =Gigot | first =Francis E. | contribution =Judaism | year =1910 | title =The Catholic Encyclopedia | volume =VIII | place=New York | publisher =Robert Appleton Company | url = http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/08399a.htm | accessdate = 2007-08-13}}</ref> | ||

| ] of Louis IX. Treasure of ].]] | ] of Louis IX. Treasure of ].]] | ||

| In addition to Louis's legislation against Jews and usury, he expanded the scope of the ] in France. The area most affected by this expansion was southern France where the ] heresy had been strongest. The rate of these confiscations reached its highest levels in the years prior to his first crusade, and slowed upon his return to France in 1254. | In addition to Louis's legislation against Jews and usury, he expanded the scope of the ] in France. The area most affected by this expansion was southern France where the ] heresy had been strongest. The rate of these confiscations reached its highest levels in the years prior to his first crusade, and slowed upon his return to France in 1254. | ||

| Line 138: | Line 141: | ||

| ==Death and legacy== | ==Death and legacy== | ||

| ] of Saint Louis (end 13th c.) ], ], ] ]] | ] of Saint Louis (end 13th c.) ], ], ] ]] | ||

| During his second crusade, Louis died at ], ], ], |

During his second crusade, Louis died at ], ], ], from what was traditionally believed to be ] but is thought by modern scholars to be ]. The local tradition of ] claims that the future Saint Louis did not die in 1270, but converted to Islam under the name of Sidi Bou Said, died at the end of the 13th century, and was buried as a saint of Islam in Djebel-Marsa. | ||

| ⚫ | Christian tradition states that some of his entrails were buried directly on the spot in Tunisia, where a Tomb of Saint-Louis can still be visited today, whereas other parts of his entrails were sealed in an urn and placed in the ], ], where they still remain. His corpse was taken, after a short stay at the ] in |

||

| ⚫ | Christian tradition states that some of his entrails were buried directly on the spot in Tunisia, where a Tomb of Saint-Louis can still be visited today, whereas other parts of his entrails were sealed in an urn and placed in the ], ], where they still remain. His corpse was taken, after a short stay at the ] in Bologna, to the French royal necropolis at ], resting in ] on the way. His tomb at Saint-Denis was a magnificent gilt brass monument designed in the late ]. It was melted down during the ], at which time the body of the king disappeared. Only one finger was rescued and is kept at Saint-Denis. | ||

| ] proclaimed the ] of Louis in ]; he is the only French monarch ever to be made a ]. | ] proclaimed the ] of Louis in ]; he is the only French monarch ever to be made a ]. | ||

| Louis IX was succeeded by his son, ]. | |||

| ==Veneration as a saint== | ==Veneration as a saint== | ||

| {{Infobox Saint | <table align=left><tr><td> {{Infobox Saint | ||

| |name=Saint Louis | |name=Saint Louis | ||

| |birth_date={{birth date|1214|4|25|df=y}}/] | |birth_date={{birth date|1214|4|25|df=y}}/] | ||

| Line 169: | Line 173: | ||

| |suppressed_date= | |suppressed_date= | ||

| |issues= | |issues= | ||

| }}</td></tr></table> | |||

| }} | |||

| Louis IX is often considered the model of the ideal Christian monarch. Because of the aura of holiness attached to |

Louis IX is often considered the model of the ideal Christian monarch. Because of the aura of holiness attached to the memory of Louis IX, many ] were called Louis, especially in the ] (] to ]). | ||

| The ] is a ] ] founded in ] and named in his honour. | The ] is a ] ] founded in ] and named in his honour. | ||

| Line 178: | Line 182: | ||

| The cities of ] in ], ], ] in ], ] in ], as well as ] in ], and the ] in ] are among the many places named after the king. | The cities of ] in ], ], ] in ], ] in ], as well as ] in ], and the ] in ] are among the many places named after the king. | ||

| The Cathedral Saint-Louis in ], ] in St. Louis, Missouri, the ] in St. Louis, Missouri, and the French royal ] (]–] and ]–]) were also created after the king. The ] in New Orleans is named after |

The Cathedral Saint-Louis in ], ] in St. Louis, Missouri, the ] in St. Louis, Missouri, and the French royal ] (]–] and ]–]) were also created after the king. The ] in New Orleans is also named after the king. | ||

| Many places in ] called ] in ] are named after Saint Louis. | Many places in ] called ] in ] are named after Saint Louis. | ||

| ] in Tunisia is said to have been named for this very Catholic French king |

] in Tunisia is said to have been named for this very Catholic French king . Tunisian legend tells the story of King Louis falling in love with a Berber princess, changing his name to Abou Said ibn Khalef ibn Yahia Ettamini el Beji (nicknamed "Sidi Bou Said") for which a quaint town on the Tunisian coast is named. He became, according to this legend, an Islamic saint. | ||

| ==Famous portraits== | ==Famous portraits== | ||

Revision as of 17:24, 2 December 2007

| Louis IX | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| King of France (more...) | |||||

| File:StL5.gifRepresentation of Saint Louis considered to be true to life - Early 14th century statue from the church of Mainneville, Eure, France | |||||

| Reign | 8 November 1226 – 25 August 1270 | ||||

| Coronation | 29 November 1226, Reims | ||||

| Predecessor | Louis VIII | ||||

| Successor | Philip III | ||||

| Burial | Saint Denis Basilica | ||||

| Issue | Isabelle, Queen of Navarre (1241–71) Philip III (1245-85) Jean Tristan, Count of Valois (1250–70) Pierre, Count of Perche and Alençon (1251–84) Blanche, Crown Princess of Castille (1253–1323) Marguerite, Duchess of Brabant (1254–71) Robert, Count of Clermont (1256–1317) Agnes, Duchess of Burgundy (1260–1327) | ||||

| |||||

| House | House of Capet | ||||

| Father | Louis VIII of France | ||||

| Mother | Blanche of Castile | ||||

| French Monarchy |

| Direct Capetians |

|---|

|

| Hugh Capet |

|

|

| Robert II |

|

|

| Henry I |

|

|

| Philip I |

|

|

| Louis VI |

|

|

| Louis VII |

|

|

| Philip II |

|

|

| Louis VIII |

|

|

| Louis IX |

|

|

| Philip III |

|

|

| Philip IV |

|

| Louis X |

|

|

| John I |

| Philip V |

|

|

| Charles IV |

|

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), commonly Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 to his death. He was also Count of Artois (as Louis II) from 1226 to 1237. Born at Poissy, near Paris, he was a member of the House of Capet and the son of King Louis VIII and Blanche of Castile. He is the only canonised king of France and consequently there are many places named after him, most notably the city in Missouri of the same name. He established the Parlement of Paris.

Sources

Much of what is known of Louis's life comes from Jean de Joinville's famous biography of Louis, Life of Saint Louis. Joinville was a close friend, confidant, and counsellor to the king, and also participated as a witness in the papal inquest into Louis' life that ended with his canonization in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII.

Two other important biographies were written by the king's confessor, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and his chaplain, William of Chartres. The fourth important source of information is William of Saint-Pathus' biography, which he wrote using the papal inquest mentioned above. While several individuals wrote biographies in the decades following the king's death, only Jean of Joinville, Geoffrey of Beaulieu, and William of Chartres wrote from personal knowledge of the king.

Early life

Louis was eleven years old when his father died on November 8, 1226. He was crowned king the same year in the cathedral at Reims.

Assumption of power

Because of Louis's youth, his mother, Blanche of Castile, ruled France as regent during his minority. No date is given for Louis's assumption of the throne as king in his own right. His contemporaries viewed his reign as co-rule between the king and his mother, though historians generally view the year 1234 as the year in which Louis ruled as king with his mother assuming a more advisory role. She continued as an important counsellor to the king until her death in 1252. On May 27, 1234 Louis married Marguerite de Provence (1221 – December 21, 1295), the sister of Eleanor, the wife of Henry III of England.

Louis was the elder brother of Charles I of Sicily (1227–85), whom he created count of Anjou, thus founding the second Angevin dynasty. The horrific fate of that dynasty in Sicily as a result of the Sicilian Vespers evidently did not tarnish Louis's credentials for sainthood.

Crusading

Louis brought an end to the Albigensian Crusade in 1229 after signing an agreement with Count Raymond VII of Toulouse that cleared his father of wrong-doing. Raymond VI had been suspected of murdering a preacher on a mission to convert the Cathars.

Louis's piety and kindness towards the poor was much celebrated. He went on crusade twice, in 1248 (Seventh Crusade) and then in 1270 (Eighth Crusade). Both crusades were complete disasters; after initial success in his first attempt, Louis's army of 15,000 men was met by overwhelming resistance from the Egyptian army and people.

He had begun with the rapid capture of the port of Damietta in June 1249, an attack which did cause some disruption in the Muslim Ayyubid empire, especially as the current sultan was on his deathbed. But the march from Damietta towards Cairo through the Nile River Delta went slowly. During this time, the Ayyubid sultan died, and a sudden power shift took place, as the sultan's slave wife Shajar al-Durr set events in motion which were to make her Queen, and eventually place the Egyptian's slave army of the Mamluks in power. On April 13 1250 Louis lost his army at the Battle of al Mansurah and was captured by the Egyptians. His release was eventually negotiated, in return for a ransom of 400,000 livres tournois (at the time France's annual revenue was only about 250,000 livres tournois, so it was necessary to obtain a loan from the Templars), and the surrender of the city of Damietta.

Following his release from Egyptian captivity, Louis spent four years in the crusader Kingdoms of Acre, Caesarea, and Jaffe. Louis used his wealth to assist the crusaders in rebuilding their defenses and conducting diplomacy with the Islamic powers of Syria and Egypt. Upon his departure from Middle East Louis left a significant garrison in the city of Acre for its defense against Islamic attacks. The historic presence of this French garrison in the Middle East was later used as a justification for the French Mandate following the end of the First World War.

Attempted alliances

See also: Franco-Mongol alliance

Saint Louis exchanged multiple letters and emissaries with Mongol rulers of the period. After Louis left France and disembarked at Nicosia in Cyprus, he was first met on December 20, 1248, in Nicosia by two Mongol envoys, Nestorians from Mossul named David and Marc, bearing a letter from Eljigidei, the Mongol ruler of Armenia and Persia. They communicated a proposal to form an alliance against the Muslim Ayyubids, whose Caliphate was based in Baghdad. Eljigidei suggested that King Louis should land in Egypt, while Eljigidei attacked Baghdad, in order to prevent the Saracens of Egypt and those of Syria from joining forces.

Though at least one historian has criticized Louis as being "naive" in trusting the ambassadors, and Louis himself later admitted that he regretted the decision, Louis sent André de Longjumeau, a Dominican priest, as an emissary to the Great Khan Güyük in Mongolia. However, Güyük died, from drink, before the emissary arrived at his court, and his widow Oghul Ghaimish simply gave the emissary a gift and a condescending letter to take back to King Louis, demanding that the king pay tribute to the Mongols.

In 1252, Louis attempted an alliance with the Egyptians, for the return of Jerusalem if the French assisted with the subduing of Damascus.

In 1253, Louis tried to seek allies from among both the Ismailian Assassins and the Mongols. Louis had received word that the Mongol leader Sartaq, son of Batu, had converted to Christianity, While in Cyprus, Louis also saw a letter from Sempad, brother of the Armenian ruler Hetoum I, who, on an embassy to the Mongol court in Karakorum, was describing to the Western ruler a Central Asian realm of oasis with many Christians, generally of the Nestorian rite.

Louis dispatched an envoy to the Mongol court in the person of the Franciscan William of Rubruck, who went to visit the Great Khan Möngke in Mongolia. William entered into a famous competition at the Mongol court, as the khan encouraged a formal debate between the Christians, Buddhists, and Muslims, to determine which faith was correct, as determined by three judges, one from each faith. The debate drew a large crowd, and as with most Mongol events, a great deal of alcohol was involved. As described by Jack Weatherford in his book Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World:

No side seemed to convince the other of anything. Finally, as the effects of the alcohol became stronger, the Christians gave up trying to persuade anyone with logical arguments, and resorted to singing. The Muslims, who did not sing, responded by loudly reciting the Koran in an effort to drown out the Christians, and the Buddhists retreated into silent mediation. At the end of the debate, unable to convert or kill one another, they concluded the way most Mongol celebrations concluded, with everyone simply too drunk to continue.

— Jack Weatherford, Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World, p. 173

But even after the competition, Möngke replied only with a letter via William in 1254, asking for the King's submission to Mongol authority.

Patron of arts and arbiter of Europe

Louis' patronage of the arts drove much innovation in Gothic art and architecture, and the style of his court radiated throughout Europe by both the purchase of art objects from Parisian masters for export and by the marriage of the king's daughters and female relatives to foreign husbands and their subsequent introduction of Parisian models elsewhere. Louis' personal chapel, the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, was copied more than once by his descendants elsewhere. Louis most likely ordered the production of the Morgan Bible, a masterpiece of medieval painting.

Saint Louis ruled during the so-called "golden century of Saint Louis", when the kingdom of France was at its height in Europe, both politically and economically. The king of France was regarded as a primus inter pares among the kings and rulers of Europe. He commanded the largest army, and ruled the largest and most wealthy kingdom of Europe, a kingdom which was the European center of arts and intellectual thought (La Sorbonne) at the time. For many, King Louis IX embodied the whole of Christendom in his person. His reputation of saintliness and fairness was already well established while he was alive, and on many occasions he was chosen as an arbiter in the quarrels opposing the rulers of Europe.

The prestige and respect felt in Europe for King Louis IX was due more to the attraction that his benevolent personality created rather than to military domination. For his contemporaries, he was the quintessential example of the Christian prince.

Religious zeal

The perception of Louis IX as the exemplary Christian prince was reinforced by his religious zeal. Saint Louis was a devout Catholic, and he built the Sainte Chapelle ("Holy Chapel"), located within the royal palace complex (now the Paris Hall of Justice), on the Île de la Cité in the centre of Paris. The Sainte Chapelle, a perfect example of the Rayonnant style of Gothic architecture, was erected as a shrine for the Crown of Thorns and a fragment of the True Cross, precious relics of the Passion of Jesus. Louis purchased these in 1239–41 from Emperor Baldwin II of the Latin Empire of Constantinople, for the exorbitant sum of 135,000 livres (the chapel, on the other hand, cost only 60,000 livres to build). This purchase should be understood in the context of the extreme religious fervor that existed in Europe in the 13th century. The purchase contributed greatly to reinforcing the central position of the king of France in western Christendom, as well as to increasing the renown of Paris, then the largest city of western Europe. During a time when cities and rulers vied for relics, trying to increase their reputation and fame, Louis IX had succeeded in securing the most prized of all relics in his capital. The purchase was thus not only an act of devotion, but also a political gesture: the French monarchy was trying to establish the kingdom of France as the "new Jerusalem."

Louis IX took very seriously his mission as "lieutenant of God on Earth," with which he had been invested when he was crowned in Rheims. Thus, in order to fulfill his duty, he conducted two crusades, and even though they were unsuccessful, they contributed to his prestige. Contemporaries would not have understood if the king of France did not lead a crusade to the Holy Land. In order to finance his first crusade Louis ordered the expulsion of all Jews engaged in usury. This action enabled Louis to confiscate the property of expelled Jews for use in his crusade. However, he did not eliminate the debts incurred by Christians. One-third of the debt was forgiven, but the other two-thirds was to be remitted to the royal treasury. Louis also ordered, at the urging of Pope Gregory IX, the burning of some 12,000 copies of the Talmud in Paris in 1243. Such legislation against the Talmud, not uncommon in the history of Christendom, was due to medieval courts' concerns that its production and circulation might weaken the faith of Christian individuals and threaten the Christian basis of society, the protection of which was the duty of any Christian monarch.

In addition to Louis's legislation against Jews and usury, he expanded the scope of the Inquisition in France. The area most affected by this expansion was southern France where the Cathar heresy had been strongest. The rate of these confiscations reached its highest levels in the years prior to his first crusade, and slowed upon his return to France in 1254.

In all these deeds, Louis IX tried to fulfill the duty of France, which was seen as "the eldest daughter of the Church" (la fille aînée de l'Église), a tradition of protector of the Church going back to the Franks and Charlemagne, who had been crowned by the Pope in Rome in 800. Indeed, the official Latin title of the kings of France was Rex Francorum, i.e. "king of the Franks," and the kings of France were also known by the title "most Christian king" (Rex Christianissimus). The relationship between France and the papacy was at its peak in the 12th and 13th centuries, and most of the crusades were actually called by the popes from French soil. Eventually, in 1309, Pope Clement V even left Rome and relocated to the French city of Avignon, beginning the era known as the Avignon Papacy (or, more disparagingly, the "Babylonian captivity").

Ancestors

| 16. Louis VI of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Louis VII of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 17. Adelaide of Maurienne | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Philip II of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Theobald II, Count of Champagne | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Adèle of Champagne | |||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Matilda of Carinthia | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Louis VIII of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20. Baldwin IV, Count of Hainaut | |||||||||||||||||||

| 10. Baldwin V, Count of Hainaut | |||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Alice of Namur | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. Isabelle of Hainaut | |||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Thierry, Count of Flanders | |||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Margaret I, Countess of Flanders | |||||||||||||||||||

| 23. Sibylla of Anjou | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1. Louis IX of France | |||||||||||||||||||

| 24. Alfonso VII of León | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Sancho III of Castile | |||||||||||||||||||

| 25. Berenguela of Barcelona | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Alfonso VIII of Castile | |||||||||||||||||||

| 26. García VI of Navarre | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Blanca of Navarre | |||||||||||||||||||

| 27. Marguerite de l'Aigle | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Blanche of Castile | |||||||||||||||||||

| 28. Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14. Henry II of England | |||||||||||||||||||

| 29. Matilda of England | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Leonora of England | |||||||||||||||||||

| 30. William X, Duke of Aquitaine | |||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Eleanor of Aquitaine | |||||||||||||||||||

| 31. Aenor de Châtellerault | |||||||||||||||||||

Children

- Blanche (1240 – April 29, 1243)

- Isabelle (March 2, 1241 – January 28, 1271), married Theobald V of Champagne

- Louis (February 25, 1244 – January 1260)

- Philippe III (May 1, 1245 – October 5, 1285)

- Jean (born and died in 1248)

- Jean Tristan (1250 – August 3, 1270), married Yolande of Burgundy

- Pierre (1251–84), Count of Perche and Alençon; Count of Blois and Chartres in right of his wife, Joanne of Châtillon

- Blanche (1253–1323), married Ferdinand de la Cerda, Infante of Castille

- Marguerite (1254–71), married John I, Duke of Brabant

- Robert, Count of Clermont (1256 – February 7, 1317). He was the ancestor of King Henry IV of France.

- Agnes of France (ca 1260 – December 19, 1327), married Robert II, Duke of Burgundy

Death and legacy

During his second crusade, Louis died at Tunis, August 25, 1270, from what was traditionally believed to be bubonic plague but is thought by modern scholars to be dysentery. The local tradition of Sidi Bou Said claims that the future Saint Louis did not die in 1270, but converted to Islam under the name of Sidi Bou Said, died at the end of the 13th century, and was buried as a saint of Islam in Djebel-Marsa.

Christian tradition states that some of his entrails were buried directly on the spot in Tunisia, where a Tomb of Saint-Louis can still be visited today, whereas other parts of his entrails were sealed in an urn and placed in the Basilica of Monreale, Palermo, where they still remain. His corpse was taken, after a short stay at the Basilica of Saint Dominic in Bologna, to the French royal necropolis at Saint-Denis, resting in Lyon on the way. His tomb at Saint-Denis was a magnificent gilt brass monument designed in the late 14th century. It was melted down during the French Wars of Religion, at which time the body of the king disappeared. Only one finger was rescued and is kept at Saint-Denis. Pope Boniface VIII proclaimed the canonization of Louis in 1297; he is the only French monarch ever to be made a saint.

Louis IX was succeeded by his son, Philippe III.

Veneration as a saint

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Louis IX is often considered the model of the ideal Christian monarch. Because of the aura of holiness attached to the memory of Louis IX, many Kings of France were called Louis, especially in the Bourbon dynasty (Louis XIII to Louis XVIII).

The Congregation of the Sisters of Saint Louis is a Roman Catholic religious order founded in 1842 and named in his honour.

Places named after Saint Louis

The cities of San Luis Potosí in Mexico, Saint Louis, Missouri, Saint-Louis du Sénégal in Senegal, Saint-Louis in Alsace, as well as Lake Saint-Louis in Quebec, and the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia in California are among the many places named after the king.

The Cathedral Saint-Louis in Versailles, Basilica of St. Louis, King of France in St. Louis, Missouri, the Cathedral-Basilica of St. Louis in St. Louis, Missouri, and the French royal Order of Saint Louis (1693–1790 and 1814–30) were also created after the king. The Saint Louis Cathedral in New Orleans is also named after the king.

Many places in Brazil called São Luís in Portuguese are named after Saint Louis.

Sidi Bou Said in Tunisia is said to have been named for this very Catholic French king . Tunisian legend tells the story of King Louis falling in love with a Berber princess, changing his name to Abou Said ibn Khalef ibn Yahia Ettamini el Beji (nicknamed "Sidi Bou Said") for which a quaint town on the Tunisian coast is named. He became, according to this legend, an Islamic saint.

Famous portraits

A portrait of St. Louis hangs in the chamber of the United States House of Representatives.

Saint Louis is also portrayed on a frieze depicting a timeline of important lawgivers throughout world history in the Courtroom at the Supreme Court of the United States.

External links

- Site about The Saintonge War between Louis IX of France and Henry III of England.

- Account of the first Crusade of Saint Louis from the perspective of the Arabs..

- A letter from Guy, a knight, concerning the capture of Damietta on the sixth Crusade with a speech delivered by Saint Louis to his men.

- Etext full version of the Memoirs of the Lord of Joinville, a biography of Saint Louis written by one of his knights

- Biography of Saint Louis on the Patron Saints Index

Bibliography

Joinville, Jean de, The History of St. Louis (Trans. Joan Evans).

References

- Tyerman, p. 787

- Tyerman, pp. 789-798

- "Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie", p66

- Peter Jackson (July 1980). "The Crisis in the Holy Land in 1260". The English Historical Review. 95 (376): 481–513.

- Grousset, p.523

- Tyerman, p. 786

- Runciman, p.260

- Tyerman, p. 798. "Louis's embassy under Andrew of Longjumeau had returned in 1251 carrying a demand from the Mongol regent, Oghul Qaimush, for annual tribute, not at all what the king had anticipated.

- Runciman, pp. 279-280

- Runciman, p.380

- Jean Richard, “Histoire des Croissades”, p. 376

- J. Richard, 1970, p. 202., Encyclopedia Iranica,

- Gigot, Francis E. (1910), "Judaism", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. VIII, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 2007-08-13

External links

- Goyau, Georges (1910), "St. Louis IX", The Catholic Encyclopedia, vol. IX, New York: Robert Appleton Company, retrieved 2007-08-13

| Louis IX of France House of CapetBorn: 25 April 1215 Died: 25 August 1270 | ||

| Preceded byLouis VIII of France | King of France 8 November, 1226 – 25 August, 1270 |

Succeeded byPhilip III |

| Count of Artois 8 November, 1226 – 1237 |

Succeeded byRobert I | |

| Monarchs of France | |

|---|---|

| Merovingians (509–751) | |

| Carolingians, Robertians and Bosonids (751–987) | |

| House of Capet (987–1328) | |

| House of Valois (1328–1589) | |

| House of Lancaster (1422–1453) | |

| House of Bourbon (1589–1792) | |

| House of Bonaparte (1804–1814; 1815) | |

| House of Bourbon (1814–1815; 1815–1830) | |

| House of Orléans (1830–1848) | |

| House of Bonaparte (1852–1870) | |

| Debatable or disputed rulers are in italics. | |