| Revision as of 04:44, 7 December 2007 editPanda (talk | contribs)3,689 edits WP:DASH fix: en-dashes & em-dashes← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:21, 7 December 2007 edit undoPanda (talk | contribs)3,689 edits →Dialects: changed external jumps to refsNext edit → | ||

| Line 100: | Line 100: | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| :1. ], ]: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Norrland/Norrbotten/Overkalix/yw.html | title = Yngrre kvinna, Överkalix | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- External jumps are only used in external links, please convert these to refs or move to external links --> | |||

| : |

:2. ], ]: older female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Norrland/Vasterbotten/Burtrask/ow.html | title = Äldre kvinna, Burträsk| accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:3. ], ]: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Norrland/Jamtland/Aspas/yw.html | title = Yngre kvinna, Aspås | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:4. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Norrland/Halsingland/Farila/om.html | title = Äldre man, Färila | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| :5. ], ]: older female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Svealand/Dalarna/Alvdalen/ow.html | title = Äldre kvinna, Älvdalen | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | |||

| :4. ], ]; | |||

| : |

:6. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Svealand/Uppland/Graso/om.html | title = Äldre man, Gräsö | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:7. ], ]: younger male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Svealand/Sodermanland/Sorunda/ym.html | title = Yngre man, Sorunda | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:8. ], ]: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Svealand/Varmland/Kola/yw.html | title = Yngre kvinna, Köla| accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:9. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Svealand/Narke/Viby/om.html | title = Äldre man, Viby | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| :10. ], Gotland: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Gotland/Sproge/yw.html | title = Yngre kvinna, Sproge | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | |||

| :9. ], ]; | |||

| ⚫ | :11. ], ]: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Finland/Osterbotten/Narpes/yw.html | title = Yngre kvinna, Närpes | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| :10. ], Gotland; | |||

| :12. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Finland/Aboland/Dragsfjard/om.html | title = Äldre man, Dragsfjärd | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | :11. ], ] |

||

| : |

:13. ]/], ]/]: younger male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Finland/Nyland/Borga/ym.html | title = Yngre man, Borgå| accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| :14. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Bohuslan/Orust/om.html | title = Äldre man, Orust| accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | |||

| :13. ], ]; | |||

| : |

:15. ], ]: older female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Vastergotland/Floby/ow.html | title = Äldre kvinna, Floby | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:16. ], ]: older female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Ostergotland/Rimforsa/ow.html | title = Äldre kvinna, Rimforsa | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:17. ], ]: younger male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Halland/Arstad/ym.html | title = Yngre man, Årstad-Heberg | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:18. ], ]: younger female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Smaland/Stenberga/yw.html | title = Yngre kvinna, Stenberga | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:19. ], ]: older female<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Blekinge/Jamshog/ow.html | title = Äldre kvinna, Jämshög | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| : |

:20. ], ]: older male<ref>{{cite web | url = http://swedia.ling.gu.se/Gotaland/Skane/Bara/om.html | title = Äldre man, Bara | accessdate = 2007-12-07 | publisher = SweDia | year = 2000 | language = Swedish}}</ref> | ||

| :20. ], ]; | |||

| ===Standard Swedish=== | ===Standard Swedish=== | ||

Revision as of 05:21, 7 December 2007

| Swedish | |

|---|---|

| svenska | |

| Native to | Sweden and Finland |

| Region | Northern Europe |

| Native speakers | c. 9 million |

| Language family | Indo-European

|

| Official status | |

| Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Swedish Language Council (in Sweden) Svenska språkbyrån (in Finland) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | sv |

| ISO 639-2 | swe |

| ISO 639-3 | swe |

| |

Swedish (svenska) is a North Germanic language, spoken predominantly in Sweden, parts of Finland, especially along the coast, on the Åland islands, by more than nine million people. It is mutually intelligible with two of the other North Germanic languages, Danish and Norwegian. Along with the other North Germanic languages, Swedish is a descendant of Old Norse, the common language of the Germanic peoples living in Scandinavia during the Viking Era.

Standard Swedish is the national language that evolved from the Central Swedish dialects in the 19th century and was well-established by the beginning of the 20th century. While distinct regional varieties descended from the older rural dialects still exist, the spoken and written language is uniform and standardized. Some dialects differ considerably from the standard language in grammar and vocabulary and are not always mutually intelligible with Standard Swedish. These dialects are confined to rural areas and are spoken primarily by small numbers of people with low social mobility. Though not facing imminent extinction, such dialects have been in decline during the past century, despite the fact that they are well researched and their use is often encouraged by local authorities.

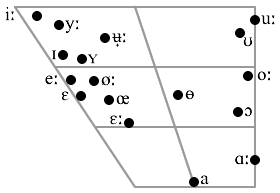

The standard word order is Subject Verb Object, though this can often be changed to stress certain words of phrases. Swedish morphology is similar to English, i.e. that words have comparatively few inflections; there are two genders, no grammatical cases (though older analyses posit two cases, nominative and genitive), and a distinction between plural and singular. Adjectives are compared as in English, and are also inflected according to gender, number and definiteness. The definiteness of nouns is marked primarily through suffixes (endings), complemented with separate definite and indefinite articles. The prosody features both stress and in most dialects tonal qualities. The language has a comparatively large vowel inventory. Swedish is also notable for the voiceless dorso-palatal velar fricative, a highly variable consonant phoneme.

Classification

Swedish is an Indo-European language belonging to the North Germanic branch of the Germanic languages. In the established classification it belongs to the East Scandinavian languages together with Danish, separating it from the West Scandinavian languages, consisting of Faroese, Icelandic and Norwegian. However, more recent analyses divide the North Germanic languages into two groups: Insular Scandinavian, Faroese and Icelandic, and Continental Scandinavian, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, based on mutual intelligibility due to heavily influence of East Scandinavian (particular Danish) on Norwegian during the last millennium and divergence from from both Faroese and Icelandic.

By many general criteria of mutual intelligibility, the Continental Scandinavian languages could very well be considered to be dialects of a common Scandinavian language. However, due to several hundred years of sometimes quite intense rivalry between Denmark and Sweden, including a long string of wars in the 16th and 17th centuries, and the nationalist ideas that emerged during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the languages have separate orthographies, dictionaries, grammars, and regulatory bodies. Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish are thus from a linguistic perspective more accurately described as a dialect continuum of Scandinavian (North Germanic), and some of the dialects, such as those on the border between Norway and Sweden—especially parts of Bohuslän, Dalsland, western Värmland, western Dalarna, Härjedalen and Jämtland—take up a middle ground between the national standard languages.

History

Main article: History of SwedishIn the 9th century, Old Norse began to diverge into Old West Norse (Norway and Iceland) and Old East Norse (Sweden and Denmark). In the 12th century, the dialects of Denmark and Sweden began to diverge, becoming Old Danish and Old Swedish in the 13th century. All were heavily influenced by Middle Low German during the medieval period. Though stages of language development are never as sharply delimited as implied here, and should not be taken too literally, the system of subdivisions used in this article is the most commonly used by Swedish linguists and is used for the sake of practicality.

Old Norse

Main article: Old Norse

In the 8th century, the common Germanic language of Scandinavia, Proto-Norse, had undergone some changes and evolved into Old Norse. This language began to undergo new changes that did not spread to all of Scandinavia, which resulted in the appearance of two similar dialects, Old West Norse (Norway and Iceland) and Old East Norse (Denmark and Sweden).

The subdialect of Old East Norse spoken in Sweden is called Runic Swedish and the one in Denmark Runic Danish (there was also a subdialect spoken in Gotland, Old Gutnish) but until the 12th century, the dialect was the same in the two countries with the main exception of a Runic Danish monophthongization (see below). The dialects are called runic due to the fact that the main body of text appears in the runic alphabet. Unlike Proto-Norse, which was written with the Elder Futhark alphabet, Old Norse was written with the Younger Futhark alphabet, which only had 16 letters. Due to the limited number of runes, some runes were used for a range of phonemes, such as the rune for the vowel u which was also used for the vowels o, ø and y, and the rune for i which was also used for e.

From 1100 and onwards, the dialect of Denmark began to diverge from that of Sweden. The innovations spread unevenly from Denmark which created a series of minor dialectal boundaries, isoglosses, ranging from Zealand in the south to Norrland, Österbotten and southeastern Finland in the north.

An early change that separated Runic Danish from the other dialects of Old East Norse was the change of the diphthong æi to the monophthong é, as in stæinn to sténn "stone". This is reflected in runic inscriptions where the older read stain and the later stin. There was also a change of au as in dauðr into a long open ø as in døðr "dead". This change is shown in runic inscriptions as a change from tauþr into tuþr. Moreover, the øy diphthong changed into a long close ø, as in the Old Norse word for "island". These innovations had affected most of the Runic Swedish speaking area as well in the end of the period, with the exception of the dialects spoken north and east of Mälardalen where the diphthongs still exist in remote areas.

Old Swedish

Old Swedish is the term used for the medieval Swedish language, starting in 1225. Among the most important documents of the period written in Latin script is the oldest of the provincial law codes, Västgötalagen, of which fragments dated to 1250 have been found. The main influences during this time came with the firm establishment of the Roman Catholic Church and various monastic orders, introducing many Greek and Latin loanwords. With the rise of Hanseatic power in the late 13th and early 14th century, the influence of Low Saxon became ever more present. The Hanseatic league provided Swedish commerce and administration with a large number of German speaking immigrants. Many became quite influential members of Swedish medieval society, and brought terms from their mother tongue into the vocabulary. Besides a great number of loan words for areas like warfare, trade and administration, general grammatical suffixes and even conjunctions were imported. Almost all of the naval terms were also borrowed from Dutch.

Early medieval Swedish was markedly different from the modern language in that it had a more complex case structure and had not yet experienced a reduction of the gender system. Nouns, adjectives, pronouns and certain numerals were inflected in four cases; besides the modern nominative, there were also the genitive, dative and accusative. The gender system resembled that of modern German, having the genders masculine, feminine and neuter. Most of the masculine and feminine nouns were later grouped together into a common gender. The verb system was also more complex: it included subjunctive and imperative moods and verbs were conjugated according to person as well as number. By the 16th century, the case and gender systems of the colloquial spoken language and the profane literature had been largely reduced to the two cases and two genders of modern Swedish. The old inflections remained common in high prose style until the 18th century, and in some dialects into the early 20th century.

A transitional change of the Latin script in the Nordic countries was to spell the letter combination "ae" as æ—and sometimes as a'—though it varied between individuals and regions. The combination "ao" was similarly rendered a, and "oe" became o. These three were later to evolve into the separate letters ä, å and ö.

New Swedish

Main article: New Swedish

New Swedish begins with the advent of the printing press and the European Reformation. After assuming power, the new monarch Gustav Vasa ordered a Swedish translation of the Bible. The New Testament was published in 1526, followed by a full Bible translation in 1541, usually referred to as the Gustav Vasa Bible, a translation deemed so successful and influential that, with revisions incorporated in successive editions, it remained the most common Bible translation until 1917. The main translators were Laurentius Andreæ and the brothers Laurentius and Olaus Petri.

The Vasa Bible is often considered to be a reasonable compromise between old and new; while not adhering to the colloquial spoken language of its day it was not overly conservative in its use of archaic forms. It was a major step towards a more consistent Swedish orthography. It established the use of the vowels "å", "ä", and "ö", and the spelling "ck" in place of "kk", distinguishing it clearly from the Danish Bible, perhaps intentionally due to the ongoing rivalry between the countries. All three translators came from central Sweden which is generally seen as adding specific Central Swedish features to the new Bible.

Though it might seem as if the Bible translation set a very powerful precedent for orthographic standards, spelling actually became more inconsistent during the remainder of the century. It was not until the 17th century that spelling began to be discussed, around the time when the first grammars were written. The spelling debate raged on until the early 19th century, and it was not until the latter half of the 19th century that the orthography reached generally acknowledged standards.

Capitalization during this time was not standardized. It depended on the authors and their background. Those influenced by German capitalized all nouns, while others capitalized more sparsely. It is also not always apparent which letters are capitalized, due to the Gothic or blackletter font which was used to print the Bible. This font was in use until the mid-18th century, when it was gradually replaced with a Latin font (often antiqua).

Some important changes in sound during the New Swedish period were the gradual assimilation of several different consonant clusters into the fricative /ʃ/ and later into /ɧ/. There was also the gradual softening of /g/ and /k/ into /j/ and the fricative /ɕ/ before front vowels. The velar fricative /ɣ/ was also transformed into the corresponding plosive /g/.

Modern Swedish

The period that includes Swedish as it is spoken today is termed nusvenska ("Contemporary Swedish", lit. "Now-Swedish") in linguistic terminology. With the industrialization and urbanization of Sweden well under way by the last decades of the 19th century, a new breed of authors made their mark on Swedish literature. Many authors, scholars, politicians and other public figures had a great influence on the new national language that was emerging, the most influential of these being August Strindberg (1849–1912).

It was during the 20th century that a common, standardized national language became available to all Swedes. The orthography was finally stabilized, and was almost completely uniform, with the exception of some minor deviations, by the time of the spelling reform of 1906. With the exception of plural forms of verbs and a slightly different syntax, particularly in the written language, the language was the same as the Swedish spoken today. The plural verb forms remained, in ever decreasing use, in formal (and particularly written) language until the 1950s, when they were finally officially abolished even from all official recommendations.

A very significant change in Swedish occurred in the 1960s, with the so-called du-reformen, "the you-reform". Previously, the proper way to address people of the same or higher social status had been by title and surname. The use of herr ("Mr" or "Sir"), fru ("Mrs" or "Ma'am") or fröken ("Miss") was only considered acceptable in initial conversation with strangers of unknown occupation, academic title or military rank. The fact that the listener should preferably be referred to in the third person tended to further complicate spoken communication between members of society. In the early 20th century, an unsuccessful attempt was made to replace the insistence on titles with ni (the standard second person plural pronoun)—analogous to the French Vous. Ni (plural second person pronoun) wound up being used as a slightly less familiar form of du (singular second person pronoun) used to address people of lower social status. With the liberalization and radicalization of Swedish society in the 1950s and 1960s, these previously significant distinctions of class became less important and du became the standard, even in formal and official contexts. Though the reform was not an act of any centralized political decrees, but rather a sweeping change in social attitudes, it was completed in just a few years from the late 1960s to early 1970s. However, among younger generations the form ni remains in frequent use as a respectful form of address towards older people, and is occasionally used by sales clerks towards customers.

Former language minorities

From the 13th to 20th century, there were Swedish-speaking communities in Estonia, particularly on the islands (e.g., Hiiumaa, Vormsi, Ruhnu in Swedish: Dagö, Ormsö, Runö, respectively) along the coast of the Baltic, which today have all but disappeared. The Swedish-speaking minority was represented in parliament, and entitled to use their native language in parliamentary debates. After the loss of Estonia to the Russian Empire in the early 18th century, around 1,000 Estonian Swedish speakers were forced to march to southern Ukraine, where they founded a village, Gammalsvenskby ("Old Swedish Village"). A few elderly people in the village still speak Swedish and observe the holidays of the Swedish calendar, although the dialect is most likely facing extinction.

From 1918–1930, when Estonia was independent, the small Swedish community was well treated. Municipalities with a Swedish majority, mainly found along the coast, used Swedish as the administrative language and Swedish-Estonian culture saw an upswing. However, most Swedish-speaking people fled to Sweden before the end of World War II prior to the invasion of Estonia by the Soviet army in 1944. Only a handful of older speakers remain today.

Geographic distribution

Swedish is the national language of Sweden and the first language for the overwhelming majority of roughly eight million Swedish born inhabitants and acquired by one million immigrants. In the latter half of the 2000s, around 5.5% of the population of Finland are Swedish speakers, though the percentage has declined steadily over the last 400 years. The Finland Swedish minority is concentrated in the coastal areas and archipelagos of southern and western Finland. In some of these areas, Swedish is the dominating language. In 19 municipalities, 16 of which are located in Åland], Swedish is the only official language. In several more, it is the majority language and it is an official minority language in even more. There is considerable migration between the Nordic countries, but due to the similarity between the languages and cultures (with the exception of Finnish), expatriates generally assimilate quickly and do not stand out as a group. According to the 2000 US census some 67,000 people over age five were reported as Swedish speakers, though without any information on actual language proficiency. Outside Sweden, there are about 40,000 active learners enrolled in Swedish language courses.

Official status

Swedish in Sweden is considered the "main language" and is used as the primary language used in local and state government, but not legally recognized as an official language. A bill was proposed in 2005 that would have made Swedish an official language, but failed to pass by the narrowest possible margin (145–147) due to a pairing-off failure.

Swedish is the only official language of Åland (an autonomous province under the sovereignty of Finland) where the vast majority of the 26,000 inhabitants speak Swedish as a first language. In Finland, Swedish is the second national language alongside Finnish. In the Estonian village Noarootsi, Swedish is the official language together with Estonian. Swedish is also one of the official languages of the European Union and one of the working languages of the Nordic Council. Under the Nordic Language Convention, citizens of the Nordic countries speaking Swedish have the opportunity to use their native language when interacting with official bodies in other Nordic countries without being liable to any interpretation or translation costs.

Regulatory bodies

The Swedish Language Council (Språkrådet) is the official regulator of Swedish, but does not attempt to enforce control of the language, as for instance the Académie française does. However, many organizations and agencies require the use of the council's publication Svenska skrivregler in official contexts, with it otherwise being regarded as a de facto orthographic standard. Among the many organizations that make up the Swedish Language Council, the Swedish Academy (established 1786) is arguably the most influential. Its primary instruments are the dictionaries Svenska Akademiens Ordlista (SAOL, currently in its 13th edition) and Svenska Akademiens Ordbok, in addition to various books on grammar, spelling and manuals of style. Even though the dictionaries are sometimes used as official decrees of the language, their main purpose is to describe current usage.

In Finland a special branch of the Research Institute for the Languages of Finland has official status as the regulatory body for Swedish in Finland. Among its highest priorities is to maintain intelligibility with the language spoken in Sweden. It has published Finlandssvensk ordbok, a dictionary about the differences between Swedish in Finland and in Sweden from their point of view.

Dialects

Main article: Swedish dialectsThe traditional definition of a Swedish dialect has been a local variant that has not been heavily influenced by the standard language and that can trace a separate development all the way back to Old Norse. Many of the genuine rural dialects, such as those of Orsa in Dalarna or Närpes in Österbotten, have very distinct phonetic and grammatical features, such as plural forms of verbs or archaic case inflections. These dialects can be near-incomprehensible to a majority of Swedes, and most of their speakers are also fluent in Standard Swedish. The different dialects are often so localized that they are limited to individual parishes and are referred to by Swedish linguists as sockenmål (lit. "parish speech"). They are generally separated into six major groups, with common characteristics of prosody, grammar and vocabulary. One or several examples from each group are given here. Though each example is intended to be also representative of the nearby dialects, the actual number of dialects is several hundred if each individual community is considered separately.

This type of classification, however, is based on a somewhat romanticized nationalist view of ethnicity and language. The idea that only rural variants of Swedish should be considered "genuine" is not generally accepted by modern scholars. No dialects, no matter how remote or obscure, remained unchanged or undisturbed by a minimum of influences from surrounding dialects or the standard language, especially not from the late 1800s and onwards with the advent of mass media and advanced forms of transports. The differences are today more accurately described by a scale that runs from "standard language" to "rural dialect" where the speech even of the same individual may vary from one extreme to the other depending on the situation. All Swedish dialects with the exception of the highly diverging forms of speech in Dalarna, Norrbotten and, to some extent, Gotland can be considered to be part of a common, mutually intelligible dialect continuum. This continuum may also include Norwegian and some Danish dialects.

The samples linked below have been taken from SweDia, a research project on Swedish modern dialects available for download (though with information in Swedish only), with many more samples from 100 different dialects with recordings from four different speakers; older female, older male, younger female and younger male. The dialect groups are those traditionally used by dialectologists.

- 1. Överkalix, Norrbotten: younger female

- 2. Burträsk, Västerbotten: older female

- 3. Aspås, Jämtland: younger female

- 4. Färila, Hälsingland: older male

- 5. Älvdalen, Dalarna: older female

- 6. Gräsö, Uppland: older male

- 7. Sorunda, Södermanland: younger male

- 8. Köla, Värmland: younger female

- 9. Viby, Närke: older male

- 10. Sproge, Gotland: younger female

- 11. Närpes, Ostrobothnia: younger female

- 12. Dragsfjärd, Åboland: older male

- 13. Borgå/Porvoo, Nyland/Eastern Uusimaa: younger male

- 14. Orust, Bohuslän: older male

- 15. Floby, Västergötland: older female

- 16. Rimforsa, Östergötland: older female

- 17. Årstad-Heberg, Halland: younger male

- 18. Stenberga, Småland: younger female

- 19. Jämshög, Blekinge: older female

- 20. Bara, Scania: older male

Standard Swedish

Standard Swedish, which is derived from the dialects spoken in the capital region around Stockholm, is the language used by virtually all Swedes and most Swedish-speaking Finns. The Swedish term most often used for the standard language is rikssvenska ("National Swedish") and to a much lesser extent högsvenska ("High Swedish"); the latter term is limited to Swedish spoken in Finland and is seldom used in Sweden. There are many regional varieties of the standard language that are specific to geographical areas of varying size (regions, historical provinces, cities, towns, etc.). While these varieties are often influenced by the genuine dialects, their grammatical and phonological structure adheres closely to those of the Central Swedish dialects. In mass media it is no longer uncommon for journalists to speak with a distinct regional accent, but the most common pronunciation and the one perceived as the most formal is still Central Standard Swedish.

Though this terminology and its definitions are long since established among linguists, most Swedes are unaware of the distinction and its historical background, and often refer to the regional varieties as "dialects". In a poll that was conducted in 2005 by the Swedish Retail Institute (Handelns Utredningsinstitut), the attitudes of Swedes to the use of certain dialects by salesmen revealed that 54% believed that rikssvenska was the variety they would prefer to hear when speaking with salesmen over the phone, even though several dialects such as gotländska or skånska were provided as alternatives in the poll.

Finland Swedish

Main article: Finland SwedishFinland was a part of Sweden from the 13th century until the loss of the Finnish territories to Russia in 1809. Swedish was the sole administrative language until 1902 as well as the dominant language of culture and education until Finnish independence in 1917. The number of Swedish speakers in Finland has steadily decreased since then.

Immigrant variants

Rinkeby Swedish (after Rinkeby, a suburb of northern Stockholm with a large population of immigrants) is a common name for varieties of Swedish spoken by second and third generation immigrants, especially among younger speakers, primarily in the suburbs of Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö. There is no consensus among linguists whether Rinkeby Swedish and similar varieties should be denominated as dialects or sociolects.

The Swedish linguist Ulla-Britt Kotsinas has described these varieties as being most prominent among teenagers living in suburbs with a large immigrant population and particularly teenage boys. In this context it can be seen as an expression of a youth culture specific to these suburbs. Rinkeby Swedish is, however, not limited to the children of immigrants and is often surprisingly similar to variants in geographically distant immigrant-dominated suburbs. In a survey made by Kotsinas, foreign learners of Swedish were asked to identify the native language and time spent in Sweden of several teenage Rinkeby Swedish speakers living in Stockholm. The survey showed that the participants had great difficulty in accurately guessing the origins of the speakers and that they generally underestimated the time spent in Sweden. The greatest difficulty proved to be identifying the speech of a boy whose parents were both Swedish; only 1.8% guessed his native language correctly.

Sounds

Main article: Swedish phonology This article contains phonetic transcriptions in the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). For an introductory guide on IPA symbols, see Help:IPA. For the distinction between , / / and ⟨ ⟩, see IPA § Brackets and transcription delimiters.Swedish has 9 vowels that make up 17 phonemes in most varieties and dialects (short /e/ and /ɛ/ coincide). There are 18 consonant phonemes out of which the voiceless palatal-velar fricative, /ɧ/, and /r/ show considerable variation depending on social and dialectal context. A distinct feature of Swedish is its varied prosody (intonation, stress, tone, etc.) which is often one of the most noticeable differences between the various dialects. Native speakers who adapt their speech when moving to areas with other regional varieties or dialects will often adhere to the sounds of the new variety, but nevertheless maintain the prosody of their native dialect. Often the prosody is the first to be changed, perhaps because it is the element most disruptive to understanding, or simply the easiest to adapt.

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosives | p | b | t | d | k | g | |||||||

| Approximants | v | l | r | j | h | ||||||||

| Fricatives | f | s | ɕ | ɧ | |||||||||

| Trills | |||||||||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ŋ | ||||||||||

Vocabulary

The vocabulary of Swedish is mainly Germanic, either through common Germanic heritage or through loans from German, Middle Low German, and to some extent, English. Examples of Germanic words in Swedish are mus ("mouse"), kung ("king"), and gås ("goose"). A significant part of the religious and scientific vocabulary is of Latin or Greek origin, often borrowed from French and, as of lately, English.

A large number of French words were imported into Sweden around the 18th century. These words have been transcribed to the Swedish spelling system and are therefore pronounced quite recognizably to a French-speaker. Most of them are distinguished by a "French accent", characterized by emphasis on the last syllable. For example, nivå (fr. niveau, "level"), fåtölj (fr. fauteuil, "arm chair") and affär ("shop; affair"), etc. Cross-borrowing from other Germanic languages has also been common, at first from Middle Low German, the lingua franca of the Hanseatic league and later from standard German. Some compounds are translations of the elements (calques) of German original compounds into Swedish, like bomull from German Baumwolle ("cotton", literally tree-wool).

Like with many Germanic languages, new words can be formed by combining words into a single compound word, e.g., nagellacksborttagningsmedel ("nail polish remover"). Similar to German or Dutch, very long, and quite impractical, examples like produktionsstyrningssystemsprogramvaruuppdatering ("production controller system software update") are possible but seldom this ungainly, at least in spoken Swedish and outside of technical writing. Compound nouns take their gender from the head, which in Swedish is always the last morpheme. New words can also be coined via derivation from other established words, such as the verbification of nouns by the adding of the suffix -a, as in öl ("beer") and öla ("to drink beer").

Writing system

The Swedish alphabet is a 29-letter alphabet, using the basic 26-letter Latin alphabet plus the three additional letters Å / å, Ä / ä, and Ö / ö constructed in modern time from the habit of writing the later letter of ao, ae and oe on top of the former. These letters are not considered diacritic embellishments of any other characters and are sorted in that order following z. Prior to the release of the 13th edition of Svenska Akademiens Ordlista in April 2006, w was treated as a variant of v used only in names (such as "Wallenberg") and foreign words ("bowling"), sorted and pronounced as a v. Diacritics are unusual in Swedish; é is sometimes used to indicate that the stress falls on a terminal syllable containing e, especially when the stress changes the meaning (ide vs idé); occasionally other acute accents and, less often, grave accents can be seen in names and some foreign words. The letter à is used to refer to unit cost, equivalent to the at sign (@) in English.

German ü is treated a variant of y and sometimes retained in foreign names. A diaeresis may very exceptionally be seen in elaborated style (for instance: "Aïda"). The letters ä and ö can be the result of a phonetic transformation called omljud, equivalent to German umlaut, where a or å is softened to ä during conjugation (natt – nätter, tång – tänger), and o is softened to ö (bok – böcker). This is far from the only use of these characters, however. Additionally, for adjectives subject to omljud, u get softened to y (ung – yngre); this is never written ü. The German convention of writing ä and ö as ae and oe if the characters are unavailable is an unusual convention for speakers of modern Swedish. Despite the availability of all these characters in the Swedish national top-level Internet domain and other such domains, Swedish sites are frequently labelled using a and o, based on visual similarity.

In Swedish orthography, the colon is used in a similar manner as in English with some exceptions. The colon is used with numbers, such as 10:50 kronor for tio kronor och femtio öre (10.50 SEK); for abbreviations such as 1:a for första (first) and S:t for Sankt (Saint); and all types of suffixes that can be added to numbers, letters and abbreviations, such as 53:an for femtitrean (the 53), första a:t for "the first a" and tv:n for televisionen (the television).

Grammar

Main article: Swedish grammarSwedish nouns and adjectives are declined in genders as well as number. Nouns belong to one of two genders—common for the en form or neuter for the ett form—which also determine the declension of adjectives. For example, the word fisk ("fish") is a common noun (en fisk) and can have the following forms:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| Indefinite form | fisk | fiskar |

| Definite form | fisken | fiskarna |

The definite singular form of a noun is created by adding a suffix (-en, -n, -et or -t), depending on its gender and if the noun ends in a vowel or not. The definite articles den, det, and de are used for variations to the definitiveness of a noun. They can double as demonstrative pronouns or demonstrative determiners when used with adverbs such as här ("here") or där ("here") to form den/det här ("this"), de här ("these"), den/det där ("that"), and de där ("those"). For example, den där fisken means "that fish" and refers to a specific fish; den fisken is less definite and means "that fish" in a more abstract sense, such as that set of fish; while fisken means "the fish". In certain cases, the definite form indicates possession, e.g., jag måste tvätta håret ("I must wash my hair").

Adjectives are inflected in two declensions—indefinite and definite—and they must match the noun they modify in gender and number. The indefinite neuter and plural forms of an adjective are created by adding a suffix (-t or -a) to the common form of the adjective, e.g., en grön stol (a green chain), ett grönt hus (a green house), and gröna stolar (green chairs). The definite form of an adjective is identical to the indefinite plural form, e.g., den gröna stolen (the green chair), det gröna huset (the green house), and de gröna stolarna (the green chairs). The irregular adjective liten (little/small) is declined differently:

| Common singular | Neuter singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indefinite form | liten | litet | små |

| Definite form | lilla | lilla | små |

Swedish pronouns are basically the same as those of English but distinguish two genders and have an additional object form, derived from the old dative form, as well as a distinct genitive case. Hon ("she") has the following forms in nominative, genitive, and object form:

- hon - hennes - henne

Possession is expressed with the enclitic -s, which attaches to the end of a (possibly complex) noun phrase. In formal writing, however, usage guides generally do not recommend the enclitic to attach to anything but the head noun of the phrase; but this is nevertheless common in speech.

- mannen; "the man"

- mannens hatt; "the man's hat"

- mannen i grå kavaj; "the man in a grey suit"

- mannen i grå kavajs hatt; "the hat of the man in a grey suit", "the man in a grey suit's hat"

Verbs are conjugated according to tense. One group of verbs (the ones ending in -er in present tense) have a special imperative form, though with most verbs this is identical to the infinitive form. Perfect and present participles as adjectivistic verbs are very common:

- Perfect participle: en stekt fisk; "a fried fish"

- Present participle: en stinkande fisk; "a stinking fish"

In contrast to English and many other languages, Swedish does not use the perfect participle to form the present perfect and past perfect tenses. Rather, the auxiliary verb "har", "hade" ("have"/"has", "had") is followed by a special form, called supine, used solely for this purpose (although sometimes identical to the perfect participle):

- Perfect participle: målad; "painted" - supine målat, present perfect har målat; "have painted"

- Perfect participle: stekt, "fried" - supine stekt, present perfect har stekt; "have fried"

The Past participle is used to build the compound passive voice, instead.

In a subordinate clause, the auxiliary har is optional and often omitted, particularly in written Swedish.

- Jag ser att han (har) stekt fisken; "I see that he has fried the fish"

Subjunctive mood is occasionally used for some verbs, but its use is in sharp decline and few speakers perceive the handful of commonly used verbs (as for instance: vore, månne) as separate conjugations, most of them remaining only as set of idiomatic expressions.

The lack of cases in Swedish is compensated by a wide variety of prepositions, similar to those found in English. As in modern German, prepositions used to determine case in Swedish, but this feature remains only in idiomatic expressions like till sjöss (genitive) or man ur huse (dative singular), though some of these are still quite common.

Swedish being a Germanic language, the syntax shows similarities to both English and German. Like English, Swedish has a Subject Verb Object basic word order, but like German, it utilizes verb-second word order in main clauses, for instance after adverbs, adverbial phrases and dependent clauses. Prepositional phrases are placed in a Place Manner Time order, like in English (and unlike German). Adjectives precede the noun they modify.

Sample

Excerpt from Barfotabarn (1933), by Nils Ferlin (1898–1961):

| Original | Translation |

|---|---|

| Du har tappat ditt ord och din papperslapp, | You've lost your word and your written note, |

| du barfotabarn i livet. | you barefooted child of life. |

| Så sitter du åter på handlar'ns trapp | Now you're sitting again on the grocer's porch |

| och gråter så övergivet. | and crying, abandoned. |

| Vad var det för ord – var det långt eller kort, | What was it, that word – was it long, was it short, |

| var det väl eller illa skrivet? | was it well or poorly written? |

| Tänk efter nu – förr'n vi föser dig bort, | Think twice now – lest we send you away, |

| du barfotabarn i livet. | you barefooted child of life. |

See also

- Languages of Sweden

- Languages of Finland

- Mandatory Swedish

- Minority languages of Sweden

- Swenglish

- Swedish as a foreign language

Notes

- ^ Crystal, Scandinavian

- Bergman, pp. 21–23

- Pettersson, p. 139

- Pettersson, p. 151

- Pettersson, p. 138

- Nationalencyklopedin, du-tilltal and ni-tilltal

- The number of registered Swedes in Zmeyovka (the modern Ukrainian name of Gammalsvenskby) as of 1994 was 116 according to Nationalencyklopedin, article svenskbyborna.

- Nationalencyklopedin, estlandssvenskar.

- Population structure. Statistics Finland (2007-03-29). Retrieved on 2007-11-27.

- Swedish in Finland - Virtual Finland. Virtual Finland (June 2004). Retrieved on 2007-11-28.

- Svensk- och tvåspråkiga kommuner. kommunerna.net (February 2007). Retrieved on 2007-12-03.

- Swedish. Many Languages, One America. U.S. English Foundation (2005). Retrieved on 2007-11-27.

- Learn Swedish. Swedish Institute. Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- Svenskan blir inte officiellt språk, Sveriges Television Template:Sv (2005-12-07) Retrieved on 2006-06-23.

- Päll, Peeter (October 1997). Toponymic guidelines for map and other editors - Estonia. Institute of Estonian Language. Retrieved on 2007-11-25.

- Konvention mellan Sverige, Danmark, Finland, Island och Norge om nordiska medborgares rätt att använda sitt eget språk i annat nordiskt land Template:Sv Nordic Council (2007-05-02). Retrieved on 2007-04-25.

- 20th anniversary of the Nordic Language Convention. Template:Sv Nordic news, 2007-02-22. Retrieved on 2007-04-25.

- Engstrand, p. 120

- Dahl, pp. 117–119

- Pettersson, p. 184

- "Yngrre kvinna, Överkalix" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre kvinna, Burträsk" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre kvinna, Aspås" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Färila" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre kvinna, Älvdalen" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Gräsö" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre man, Sorunda" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre kvinna, Köla" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Viby" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre kvinna, Sproge" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre kvinna, Närpes" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Dragsfjärd" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre man, Borgå" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Orust" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre kvinna, Floby" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre kvinna, Rimforsa" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre man, Årstad-Heberg" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Yngre kvinna, Stenberga" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre kvinna, Jämshög" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- "Äldre man, Bara" (in Swedish). SweDia. 2000. Retrieved 2007-12-07.

- Aronsson, Cecilia Norrländska låter bäst Template:Sv Dagens Industri 2005-05-03. Retrieved on 2007-08-24. "Norrländska och rikssvenska är de mest förtroendeingivande dialekterna. Men gotländska och värmländska gör svenskarna misstänksamma, enligt en ny riksomfattande undersökning. Handelns utredningsinstitut (HUI) har frågat 800 svenskar om hur de uppfattar olika dialekter som de hör i telefonservicesamtal, exempelvis från försäljare eller upplysningscentraler. Undersökningen visar att 54 procent föredrar att motparten pratar rikssvenska, vilket troligen hänger ihop med dess tydlighet. Men även norrländskan plockar höga poäng—25 procent tycker att det är den mest förtroendeingivande dialekten. Tilltron till norrländska är ännu större hos personer under 29 år, medan stödet för rikssvenska är störst bland personer över 55 år."

- Kotsinas, p. 151

- Nationalencyklopedin, svenska: språkhistoria

- Svenska språknämnden, pp. 154–156

- Granberry, pp. 18–19

- Bolander

References

Print sources

- Template:Sv icon Bergman, Gösta (1984), Kortfattad svensk språkhistoria, Prisma Magnum (4th ed.), Stockholm: Prisma, ISBN 91-518-1747-0, OCLC 13259382

- Template:Sv icon Bolander, Maria (2002), Funktionell svensk grammatik, Stockholm: Liber, ISBN 91-47-05054-3, OCLC 67138445

- Crystal, David (1999), The Penguin dictionary of language (2nd ed.), London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0-14-051416-3, OCLC 59441560

- Template:Sv icon Dahl, Östen (2000), Språkets enhet och mångfald, Lund: Studentlitteratur, ISBN 91-44-01158-X, OCLC 61100963

- Template:Sv icon Engstrand, Olle (2004), Fonetikens grunder, Lund: Studentlitteratur, ISBN 91-44-04238-8, OCLC 66026795

- Template:Sv icon Elert, Claes-Christian (2000), Allmän och svensk fonetik (8th ed.), Stockholm: Norstedts Akademiska Förlag, ISBN 91-1-300939-7

- Template:Sv icon Ferlin, Nils Barfotabarn (1976) Stockholm: Bonnier ISBN 91-0-024187-3

- Template:Sv icon Garlén, Claes (1988), Svenskans fonologi, Lund: Studentlitteratur, ISBN 91-44-28151-X, OCLC 67420810

- Granberry, Julian (1991), Essential Swedish Grammar, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 0-486-26953-1, OCLC 23692877

- International Phonetic Association (1999), Handbook of the International Phonetic Association: a guide to the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-63751-1, OCLC 40305532

- Template:Sv icon Kotsinas, Ulla-Britt (1994), Ungdomsspråk, Uppsala: Hallgren & Fallgren, ISBN 91-7382-718-5, OCLC 60994967

- Template:Sv icon Pettersson, Gertrud (1996), Svenska språket under sjuhundra år: en historia om svenskan och dess utforskande, Lund: Studentlitteratur, ISBN 91-44-48221-3, OCLC 36130929

- Template:Sv icon Svenska språknämnden (2000), Svenska skrivregler (2nd ed.), Stockholm: Liber (published 2002, 3rd printing), ISBN 91-47-04974-X

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|publication-date=(help) - Template:Sv icon Svensson, Lars (1974), Nordisk paleografi: Handbok med transkriberade och kommenterade skriftprov, Lund: Studentlitteratur, ISBN 9144053916, OCLC 1303752

Web sources

- Template:Sv icon Nationalencyklopedin (online edition)

- Template:Sv icon Föreningen Svenskbyborna (Svenskbyborna Society)

Recommended reading

Language courses

- Colloquial Swedish–The complete course for beginners Second Edition. Holmes, Philip; Serin, Gunilla (1999). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-13718-7

- Teach Yourself Swedish–A complete course for beginners. Croghan, Vera (1995). London: Hodder & Stoughton. Chicago: NTC/Contemporary Publishing. ISBN 0-340-61860-4

- Svenska utifrån–Lärobok i svenska. Nyborg, Roger; et al. (2001) ISBN 91-520-0673-5

- På svenska! 1 Svenska som främmande språk–Lärobok. Göransson, Ulla; et al. (1997) ISBN 91-7434-392-2

- På svenska! 2 Svenska som främmande språk–Lärobok. Göransson, Ulla; et al. (2002) ISBN 91-7434-462-5

Grammars

- Swedish Essentials of Grammar Viberg, Åke; et al. (1991) Chicago: Passport Books. ISBN 0-8442-8539-

- Swedish: An Essential Grammar. Holmes, Philip; Hinchliffe, Ian; (2000). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16048-0.

- Swedish: A Comprehensive Grammar Second Edition. Holmes, Philip; Hinchliffe, Ian; (2003). London; New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-27884-8.

- Svenska utifrån Schematic grammar–Swedish structures and everyday phrases Byrman, Gunilla; Holm, Britta; (1998) ISBN 91-520-0519-4.

Dictionaries

- Prisma's Swedish-English Dictionary Third Edition (1997) ISBN 0-8166-3163-8

- Prisma's English-Swedish Dictionary Third Edition (1997) ISBN 0-8166-3162-X

- Norstedts lilla engelska ordbok Petti, Vincent; Petti, Kerstin; (1999) ISBN 91-7227-009-8.

- Norstedts första svenska ordbok Ernby, Birgitta; et al. (2001) ISBN 91-7227-186-8.

External links

- Swedish course by Björn Engdahl

- All free Swedish dictionaries

- Lexin online dictionary from the Swedish Institute for Language and Folklore.

- Swedish Dictionary from Webster's Dictionary

- Laryngograph recordings and resynthesis of different dialects of Swedish–Sound files that illustrate the differences between prosody in Scandinavian dialects

- Digitally remastered Swedish imprints before 1700 from the webpage of the Royal Library in Stockholm

- Project Runeberg's digital facsimile edition of Nordisk familjebok, the definitive Swedish-language encyclopaedia of the late 19th and early to mid 20th centuries.

Template:Official EU languages

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: