| Revision as of 21:38, 11 September 2007 view sourceEubulides (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers27,779 edits →Speech and language: Rewrite to remove repetition; see Talk:Asperger syndrome #Speech and language.← Previous edit | Revision as of 04:33, 29 December 2007 view source Brianga (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users20,994 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 75.87.83.152 identified as vandalism to last revision by Sonjaaa. (TW)Next edit → | ||

| (634 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Asperger syndrome''' (also '''Asperger's syndrome''', '''Asperger's disorder''', '''Asperger's''' |

'''Asperger syndrome''' (U.S. pronunciation /{{IPA|ˈæspɚgɚ ˌsɪndroʊm/}}, also called '''Asperger's syndrome''', '''Asperger's disorder''', '''Asperger's''' or '''AS''') is one of several ] (ASD) characterized by difficulties in ] and by restricted and ] interests and activities. AS is distinguished from the other ASDs in having no general ] or ]. Although not mentioned in standard diagnostic criteria, ] and atypical use of language are frequently reported.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Baskin"/> | ||

| Asperger syndrome was named |

Asperger syndrome was named after ] who, in 1944, described children in his practice who appeared to have normal ] but lacked ] skills, failed to demonstrate ] with their peers, and were physically clumsy. Fifty years later, AS was recognized in the '']'' (ICD-10), and in the '']'' (DSM-IV) as ''Asperger's Disorder''. Questions about many aspects of AS remain: for example, there is lingering doubt about the distinction between AS and ] (HFA);<ref name="Klin"/> partly due to this, the ] of AS is not firmly established. The exact ] of AS is unknown, although research supports the likelihood of a ] contribution, and ] techniques have identified structural and functional differences in specific regions of the brain. | ||

| There is no single treatment for |

There is no single treatment for Asperger syndrome, and the effectiveness of particular interventions is supported by only limited data. Intervention is aimed at improving symptoms and function. The mainstay of treatment is behavioral therapy, focusing on specific deficits to address poor communication skills, obsessive or repetitive routines, and clumsiness. Most individuals with AS can learn to cope with their differences, but may continue to need moral support and encouragement to maintain an independent life.<ref name=NINDS>{{cite web |author= National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) |date=2007-07-31 |url=http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/asperger/detail_asperger.htm |accessdate=2007-08-24 |title= Asperger syndrome fact sheet}} NIH Publication No. 05-5624.</ref> Researchers and people with AS have contributed to a shift in attitudes away from the notion that AS is a deviation from the norm that must be treated or cured, and towards the view that AS is a difference rather than a disability.<ref name=Baron-Cohen2000/> | ||

| ] described his young patients |

] described his young patients as "little professors".]] | ||

| ==Classification== | ==Classification== | ||

| Asperger syndrome is one of the ]s ( |

Asperger syndrome is one of the ]s (ASD) or ]s (PDD), which are a ] that are characterized by abnormalities of ] and communication that pervade the individual's functioning, and by restricted and repetitive interests and behavior. Like other psychological development disorders, ASD begins in infancy or childhood, has a steady course without remission or relapse, and has impairments that result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain.<ref name=ICD-10-F84.0>{{cite book |chapterurl=http://www.who.int/classifications/apps/icd/icd10online/?gf80.htm+f840 |date=2006 |accessdate=2007-06-25 |title= International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems|edition=10th ed. (]) |author= ] |chapter=F84. Pervasive developmental disorders}}</ref> ASD, in turn, is a subset of the broader autism ] (BAP), which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic-like ], such as social deficits.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S |title= Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families |journal= Am J Psychiatry |date=1997 |volume=154 |issue=2 |pages=185–90 |pmid=9016266 |url=http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/154/2/185.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> Of the other four ASD forms, ] is the most similar to AS in signs and likely causes but its diagnosis requires impaired communication and allows delay in ]; ] and ] share several signs with autism, but may have unrelated causes; and ] is diagnosed when the criteria for a more specific disorder are unmet.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Lord C, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, ] |title= Autism spectrum disorders |journal=Neuron |volume=28 |issue=2 |date=2000 |pages=355–63 |doi=10.1016/S0896-6273(00)00115-X |pmid=11144346 |url=http://download.neuron.org/pdfs/0896-6273/PIIS089662730000115X.pdf |format=PDF}}</ref> The extent of the overlap between AS and ] (HFA—autism unaccompanied by mental retardation) is unclear.<ref name=Klin/><ref> | ||

| {{cite book |author= ], Mesibov GB, Kunce LJ (eds) |title= Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism? |year=1998 |publisher=Plenum |isbn=0306457466}} | |||

| The extent of the overlap between AS and ] (HFA—autism unaccompanied by mental retardation) is unclear.<ref name=Klin/><ref> | |||

| {{cite book |author= ], Mesibov GB, Kunce LJ (eds) |title= Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism? |year=1998 |publisher=Springer |isbn=0306457466}} | |||

| </ref><ref name="Kasari">{{cite journal |author= Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E |title= Current trends in psychological research on children with high-functioning autism and Asperger disorder |journal= Curr Opin Psychiatry |volume=18 |issue=5 |pages=497–501 |year=2005 |pmid=16639107 |doi=10.1097/01.yco.0000179486.47144.61}}</ref> | </ref><ref name="Kasari">{{cite journal |author= Kasari C, Rotheram-Fuller E |title= Current trends in psychological research on children with high-functioning autism and Asperger disorder |journal= Curr Opin Psychiatry |volume=18 |issue=5 |pages=497–501 |year=2005 |pmid=16639107 |doi=10.1097/01.yco.0000179486.47144.61}}</ref> | ||

| The current ASD classification may not reflect the true nature of the conditions.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Szatmari P |year=2000 |title= The classification of autism, Asperger's syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder |journal= Can J Psychiatry |volume=45 |issue=8 |pages=731–38 |pmid=11086556 |url=http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2000/Oct/Classification.asp}}</ref> |

The current ASD classification may not reflect the true nature of the conditions.<ref>{{cite journal |author= ] |year=2000 |title= The classification of autism, Asperger's syndrome, and pervasive developmental disorder |journal= Can J Psychiatry |volume=45 |issue=8 |pages=731–38 |pmid=11086556 |url=http://ww1.cpa-apc.org:8080/Publications/Archives/CJP/2000/Oct/Classification.asp}}</ref> | ||

| ==Characteristics== | ==Characteristics== | ||

| Asperger syndrome is distinguished by a pattern of symptoms rather than a single symptom. It is characterized by qualitative impairment in social interaction, by stereotyped and restricted patterns of activities and interests, and by no clinically significant delay in cognitive development or general delay in language.<ref name=BehaveNet>{{cite book |title= Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders |edition=4th ed., text revision (]) |author=] |date=2000 |isbn=0890420254 |chapter= Diagnostic criteria for 299.80 Asperger's Disorder (AD) |chapterurl=http://www.behavenet.com/capsules/disorders/asperger.htm |accessdate=2007-06-28}}</ref> Intense preoccupation with a narrow subject, one-sided verbosity, restricted ] and ], and ] are typical of the condition, but are not required for diagnosis.<ref name=Klin>{{cite journal |journal= Rev Bras Psiquiatr |year=2006 |volume=28 |issue= suppl 1 |pages=S3–S11 |title= Autism and Asperger syndrome: an overview |author= Klin A |pmid=16791390 |url=http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-44462006000500002&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Social interaction=== | ===Social interaction=== | ||

| The lack of demonstrated empathy is possibly |

The lack of demonstrated empathy is possibly the most dysfunctional aspect of Asperger syndrome.<ref name=Baskin/> Individuals with AS experience difficulties in basic elements of ], which may include a failure to develop friendships or enjoy spontaneous interests or achievements with others, a lack of social or emotional reciprocity, and impaired ] such as eye contact, facial expression, posture, and gesture.<ref name=McPartland>{{cite journal |author= McPartland J, Klin A |title= Asperger's syndrome |journal= Adolesc Med Clin |volume=17 |issue=3 |pages=771–88 |year=2006 |pmid=17030291 |doi=10.1016/j.admecli.2006.06.010}}</ref> | ||

| Unlike those with autism, people with AS are not usually withdrawn around others; they approach others, even if awkwardly, for example by engaging in a one-sided, long-winded speech about an unusual topic while being oblivious |

Unlike those with autism, people with AS are not usually withdrawn around others; they approach others, even if awkwardly, for example by engaging in a one-sided, long-winded speech about an unusual topic while being oblivious to the listener's feelings or reactions, such as signs of boredom or wanting to leave.<ref name=Klin/> This social awkwardness has been called "active, but odd".<ref name=McPartland/> This failure to react appropriately to social interaction may appear as disregard for other people's feelings, and may come across as insensitive. The cognitive ability of children with AS often lets them articulate social norms in a laboratory context,<ref name=McPartland/> where they may be able to show a theoretical understanding of other people’s emotions; however, they typically have difficulty acting on this knowledge in fluid, real-life situations.<ref name=Klin/> People with AS may analyze and distill their observation of social interaction into rigid behavioral guidelines and apply these rules in awkward ways—such as forced eye contact—resulting in demeanor that appears rigid or socially naive. Childhood desires for companionship can be numbed through a history of failed social encounters.<ref name=McPartland/> | ||

| The ] that individuals with AS are predisposed to violent or criminal behavior has been investigated and found to be unsupported by data.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2007 |title= Offending behaviour in adults with Asperger syndrome |author= Allen D, Evans C, Hider A, Hawkins S, Peckett H, Morgan H |pmid=17805955 |doi=10.1007/s10803-007-0442-9}}</ref> More evidence suggests children with AS are victims rather than victimizers.<ref name=Tsatsanis>{{cite journal |journal=Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |year=2003 |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=47–63 |title= Outcome research in Asperger syndrome and autism |author= Tsatsanis KD |pmid=12512398 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000561/fulltext}}</ref> | |||

| === Repetitive behaviors and restricted interests === | |||

| People with AS display restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities that can include interests that are abnormal in intensity or focus, inflexible adherence to routines or rituals, stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms, or a preoccupation with parts of objects.<ref name = "BehaveNet"/> | |||

| With respect to the restricted interests of those with AS, "one of the most striking features of individuals with AS is their passionate pursuit of specific areas of interest" (McPartland and Klin of the ]).<ref name="McPartland"/> | |||

| Individuals with AS may amass volumes of detailed information on unusual topics of special interest.<ref name="Klin"/><ref name="McPartland"/> While many children have developmentally appropriate interests in topics such as dinosaurs or trains, a child with AS may also be interested in transistors, subway tokens, deep fat fryers, or members of congress. These interests may have an exclusive, obsessive quality and an absence of genuine understanding of broader phenomena related to the topic.<ref name="Klin"/><ref name="McPartland"/> For example, "a child might be interested in memorizing the model numbers of antique cameras without any interest in photography".<ref name="McPartland"/> Asperger described good memory for trivial facts (occasionally even ]) in some of his patients;<ref name=lw>{{cite journal |author=Wing L |title=Asperger's syndrome: a clinical account |journal=Psychological medicine |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=115–29 |year=1981 |pmid=7208735 |url=http://www.mugsy.org/wing2.htm | accessdate= 2007-08-15}}</ref> <ref name="Hippler">{{cite journal |author=Hippler K, Klicpera C |title=A retrospective analysis of the clinical case records of 'autistic psychopaths' diagnosed by Hans Asperger and his team at the University Children's Hospital, Vienna |journal=Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. |volume=358 |issue=1430 |pages=291-301 |year=2003 |pmid=12639327 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2002.1197|url=http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1693115}}</ref> but, despite occasional appearances to the contrary,<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |year=1989 |volume=30 |issue=4 |pages=631–8 |title= Asperger syndrome—some epidemiological considerations: a research note |author= Gillberg IC, Gillberg C |pmid=2670981}}</ref> this may involve more ] than real understanding.<ref name=lw /> | |||

| === Restricted and repetitive interests and behavior === | |||

| The passionate pursuit of special interests is usually apparent by the time children with AS enter grade school (typically age 5 or 6 in the US). This may be at the expense of their developing typical peer relationships or pursuing other activities.<ref name="emed"/><ref name="McPartland"/> The topic of interest may change over time, but often dominates social relationships, contributing to the social difficulties accompanying AS.<ref name="Klin"/><ref name="McPartland"/> The entire family may become immersed in the narrow topic of interest.<ref name="Klin"/> Because topics such as dinosaurs and fictional characters often capture the interest of children, this symptom may go unrecognized, and may not be apparent until the interests become more unusual and focused over time.<ref name="Klin"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| People with Asperger syndrome display behavior, interests, and activities that are restricted and repetitive and are sometimes abnormally intense or focused. They may stick to inflexible routines or rituals, move in stereotyped and repetitive ways, or preoccupy themselves with parts of objects.<ref name=BehaveNet/> | |||

| Pursuit of specific and narrow areas of interest is one of the most striking features of AS.<ref name=McPartland/> Individuals with AS may collect volumes of detailed information on a relatively narrow topic such as dinosaurs or deep fat fryers,<!--This is cited text, it is not a joke, please do not remove--> without necessarily having genuine understanding of the broader topic.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name=Klin/> For example, a child might memorize camera model numbers while caring little about photography.<ref name=McPartland/> This behavior is usually apparent by grade school, typically age 5 or 6 in the U.S.<ref name=McPartland/> Although these special interests may change from time to time, they typically become more unusual and narrowly focused, and often dominate social interaction so much that the entire family may become immersed. Because topics such as dinosaurs often capture the interest of children, this symptom may go unrecognized.<ref name=Klin/> | |||

| Stereotyped and repetitive motor mannerisms may involve hand movements such as flapping or twisting, or complex whole-body movements;<ref name="BehaveNet"/> people with AS may display compulsive finger, hand, arm or leg movements,<ref name=Aquilla> Aquilla P, Yack E, Sutton S. "Sensory and motor differences for individuals with Asperger Syndrome: Occupational therapy assessment and intervention" in Stoddart, Kevin P. (Editor) (2005), p. 198.</ref> including ]s and ].<ref>Jankovic J, Mejia NI. "Tics associated with other disorders". ''Adv Neurol.'' 2006;99:61–68. PMID 16536352</ref><ref>Mejia NI, Jankovic J. Secondary tics and tourettism. ''Rev Bras Psiquiatr''. 2005;27(1):11–17. PMID 15867978 </ref> ] are typically repeated in longer bursts and look more voluntary or ritualistic than tics, which are usually faster, less rhythmical and more often asymmetrical than stereotypies. Although there is overlap, experienced clinicians rarely have difficulty distinguishing tics from stereotypies.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Rapin I |title= Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome |journal= Adv Neurol |volume=85 |pages=89–101 |year=2001 |pmid=11530449}}</ref> | |||

| ] and repetitive motor behaviors are a core part of the diagnosis of AS and other ASDs.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |year=2005 |volume=35 |issue=2 |pages=145–58 |title= Repetitive behavior profiles in Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism |author= South M, Ozonoff S, McMahon WM |doi=10.1007/s10803-004-1992-8 |pmid=15909401}}</ref> They include hand movements such as flapping or twisting, and complex whole-body movements.<ref name=BehaveNet/> These are typically repeated in longer bursts and look more voluntary or ritualistic than ]s, which are usually faster, less rhythmical and less often symmetrical.<ref name=RapinTS>{{cite journal |author= Rapin I |title= Autism spectrum disorders: relevance to Tourette syndrome |journal= Adv Neurol |volume=85 |pages=89–101 |year=2001 |pmid=11530449}}</ref> | |||

| ===Speech and language=== | ===Speech and language=== | ||

| Although children with |

Although children with Asperger syndrome acquire language skills without significant general delay, and the speech of those with AS typically lacks significant abnormalities, language acquisition and use is often atypical.<ref name=Klin/> Abnormalities include verbosity; abrupt transitions; literal interpretations and miscomprehension of nuance; use of ] meaningful only to the speaker; ]; unusually ]ic, ] or ] speech; and oddities in ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name=McPartland/> | ||

| Three aspects of communication patterns are of clinical interest: poor prosody, tangential and circumstantial speech, and marked verbosity. Although inflection and intonation may be less rigid or monotonic than in autism, people with AS often have a limited range of intonation; speech may be overly fast, jerky or loud. Speech may convey a sense of incoherence; the conversational style often includes monologues about topics that bore the listener, fails to provide context for comments, or fails to suppress internal thoughts. Individuals with AS may fail to monitor whether the listener is interested or engaged in the conversation. The speaker's conclusion or point may never be made, and attempts by the listener to elaborate on the speech's content or logic, or to shift to related topics, are often unsuccessful.<ref name=Klin/> | Three aspects of communication patterns are of clinical interest: poor prosody, tangential and circumstantial speech, and marked verbosity. Although inflection and intonation may be less rigid or monotonic than in autism, people with AS often have a limited range of intonation; speech may be overly fast, jerky or loud. Speech may convey a sense of incoherence; the conversational style often includes monologues about topics that bore the listener, fails to provide context for comments, or fails to suppress internal thoughts. Individuals with AS may fail to monitor whether the listener is interested or engaged in the conversation. The speaker's conclusion or point may never be made, and attempts by the listener to elaborate on the speech's content or logic, or to shift to related topics, are often unsuccessful.<ref name=Klin/> | ||

| Line 54: | Line 52: | ||

| Children with AS may have an unusually sophisticated vocabulary at a young age and have been colloquially called "little professors", but have difficulty understanding metaphorical language and tend to use language literally.<ref name=McPartland/> Individuals with AS appear to have particular weaknesses in areas of nonliteral language that include humor, irony, and teasing. They usually understand the cognitive basis of ] but may not enjoy it due to lack of understanding of its intent.<ref name=Kasari/> | Children with AS may have an unusually sophisticated vocabulary at a young age and have been colloquially called "little professors", but have difficulty understanding metaphorical language and tend to use language literally.<ref name=McPartland/> Individuals with AS appear to have particular weaknesses in areas of nonliteral language that include humor, irony, and teasing. They usually understand the cognitive basis of ] but may not enjoy it due to lack of understanding of its intent.<ref name=Kasari/> | ||

| ===Other=== | ===Other symptoms=== | ||

| Individuals with Asperger syndrome may have symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but can affect the individual or the family. These symptoms include atypical perception and problems with motor skills, sleep, and emotions. | |||

| ] writes "Children with autism spectrum disorders, notably those with Asperger syndrome, have long been reported to suffer from the kind of motor clumsiness currently subsumed under the DCD label."<ref>{{cite journal |author=Gillberg C, Kadesjö B |title=Why bother about clumsiness? The implications of having developmental coordination disorder (DCD) |journal=Neural Plast. |volume=10 |issue=1–2 |pages=59-68 |year=2003 |pmid=14640308}}</ref> | |||

| Problems with ] are not part of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, but Asperger’s initial accounts<ref name = "McPartland"/> and other diagnostic schemes<ref name="EhlGill"/> include descriptions of ]. Children with AS may be delayed in acquiring motor skills that require motor dexterity, such as bicycle riding or opening a jar, and may appear awkward or "uncomfortable in their own skin". They may be poorly coordinated, or have an odd or bouncy gait or posture, poor handwriting, or problems with visual–motor integration, visual–perceptual skills, and conceptual learning,<ref name="Klin"/><ref name="McPartland"/> while having "relative strengths in auditory and verbal skills and rote learning".<ref name="Klin"/> Research also shows problems with ] and "deficits on measures of apraxia, balance tandem gait, and finger–thumb apposition".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Weimer AK, Schatz AM, Lincoln A, Ballantyne AO, Trauner DA |title="Motor" impairment in Asperger syndrome: evidence for a deficit in proprioception |journal=Journal of developmental and behavioral pediatrics : JDBP |volume=22 |issue=2 |pages=92–101 |year=2001 |pmid=11332785}} as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), p. 774.</ref> There is no evidence that these motor skills problems differentiate AS from other high-functioning ASDs.<ref name= "McPartland"/> | |||

| Asperger’s initial accounts<ref name = "McPartland"/> and other diagnostic schemes<ref name="EhlGill">{{cite journal |author= Ehlers S, Gillberg C |title= The epidemiology of Asperger's syndrome. A total population study |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiat |year=1993 |volume=34 |issue=8 |pages=1327–50 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.1993.tb02094.x |pmid=8294522 |url=http://www.asperger.org/MAAP_Sub_Find_It_-_Publications_Ehlers_and_Gillberg_Article.htm |accessdate=2007-09-18}}</ref> include descriptions of ]. Children with AS may be delayed in acquiring motor skills that require motor dexterity, such as bicycle riding or opening a jar, and may appear awkward or "uncomfortable in their own skin". They may be poorly coordinated, or have an odd or bouncy gait or posture, poor handwriting, or problems with visual-motor integration, visual-perceptual skills, and conceptual learning.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Klin"/> They may show problems with ] (sensation of body position) on measures of ] (motor planning disorder), balance, ], and finger-thumb apposition. There is no evidence that these motor skills problems differentiate AS from other high-functioning ASDs.<ref name= "McPartland"/> | |||

| Children with AS may be sensitive to sound (]), touch, taste, sight, smell, pain, temperature, and the texture of foods; they may exhibit ],<ref name="emed"/> a neurologically based phenomenon in which the stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to automatic, involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. A review of all controlled investigations published since 1960 showed that ] were more frequent in children with autism, but there was little support for hyperarousal or ] in autism; there was evidence of hyporesponsiveness to sensory stimuli, although many of these findings have not been replicated.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S |title=Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=46 |issue=12 |pages=1255–68 |year=2005 |pmid=16313426 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x}}</ref> | |||

| Many accounts of individuals with AS and ASD report unusual sensory and perceptual skills and experiences. They may have superior performance in tasks like visual search problems that require processing of fine-grained features rather than entire configurations.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |date=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=27–43 |title= Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception |author= Mottron L, ], Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0040-7 |pmid=16453071}}</ref> They may be unusually sensitive or insensitive to sound, light, touch, texture, taste, smell, pain, temperature, and other stimuli, and they may exhibit ], for example, a smell may trigger perception of color;<ref>{{cite book |author= Bogdashina O |title= Sensory Perceptional Issues in Autism and Asperger Syndrome: Different Sensory Experiences, Different Perceptual Worlds |publisher= Jessica Kingsley |year=2003 |isbn=1843101661}}</ref> these sensory responses are found in other developmental disorders and are not specific to AS or to ASD. There is little support for increased ] or failure of ] in autism; there is more evidence of decreased responsiveness to sensory stimuli, although several studies show no differences.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S |title= Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |volume=46 |issue=12 |pages=1255–68 |year=2005 |pmid=16313426 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01431.x}}</ref> | |||

| According to McPartland and Klin (2006), a unique ] profile has been described for AS and confirmed in a review of the literature;<ref>Reitzel J, Szatmari P. "Cognitive and academic problems." In: Prior M, editor. ''Learning and behavior problems in Asperger syndrome.'' New York: Guilford Press; 2003. p. 35–54, as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), p. 774.</ref> if verified, it could differentiate between AS and HFA and aid in ]. Relative to HFA, people with AS have deficits in "fine and gross motor skills; visual motor integration; visual-spatial perception; nonverbal concept formation; and visual memory with preserved articulation, verbal output, auditory perception, vocabulary, and verbal memory".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Klin A, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Rourke BP |title=Validity and neuropsychological characterization of Asperger syndrome: convergence with nonverbal learning disabilities syndrome |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=36 |issue=7 |pages=1127–40 |year=1995 |pmid=8847376}} as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), pp. 774–775.</ref> Verbal abilities are stronger than performance abilities and indicate weakness in visual–spatial organization and graphomotor skills.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ghaziuddin M, Mountain-Kimchi K |title=Defining the intellectual profile of Asperger Syndrome: comparison with high-functioning autism |journal=Journal of autism and developmental disorders |volume=34 |issue=3 |pages=279–84 |year=2004 |pmid=15264496}}; {{cite journal |author=Ehlers S, Nydén A, Gillberg C, ''et al'' |title=Asperger syndrome, autism and attention disorders: a comparative study of the cognitive profiles of 120 children |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=38 |issue=2 |pages=207–17 |year=1997 |pmid=9232467}} as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), p. 775.</ref> Most subjects with AS in another study had a "neuropsychologic profile consistent with a nonverbal learning disability".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Klin A, Volkmar FR, Sparrow SS, Cicchetti DV, Rourke BP |title=Validity and neuropsychological characterization of Asperger syndrome: convergence with nonverbal learning disabilities syndrome |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=36 |issue=7 |pages=1127–40 |year=1995 |pmid=8847376}} as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), p. 775.</ref> The literature review did not reveal consistent findings of "nonverbal weaknesses or increased spatial or motor problems relative to individuals with HFA", leading some researchers to argue that increased cognitive ability is evidenced in AS relative to HFA regardless of differences in verbal and nonverbal ability.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Miller JN, Ozonoff S |title=The external validity of Asperger disorder: lack of evidence from the domain of neuropsychology |journal=Journal of abnormal psychology |volume=109 |issue=2 |pages=227–38 |year=2000 |pmid=10895561}} as cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006), p. 775.</ref> | |||

| Children with AS are more likely to have ] problems, including difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal ], and early morning awakenings.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= J Intellect Disabil Res |year=2005 |volume=49 |issue=4 |pages=260–8 |title= A survey of sleep problems in autism, Asperger's disorder and typically developing children |author= Polimeni MA, Richdale AL, Francis AJ |doi=10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00642.x |pmid=15816813}}</ref><ref name=Tani/> AS is also associated with high levels of ], which is difficulty in identifying and describing one's emotions.<ref>Alexithymia and AS: | |||

| ] is a personality trait of people who have difficulty recognizing, processing and regulating emotions.<ref name="Haviland">{{cite journal |author=Haviland MG, Warren WL, Riggs ML |title=An observer scale to measure alexithymia |journal=Psychosomatics |volume=41 |issue=5 |pages=385–92 |year=2000 |pmid=11015624|url=http://psy.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/41/5/385#R26732 | accessdate=2007-08-10}}</ref> ] reported that alexithymia overlaps with AS, and that at least half of the Asperger syndrome subjects in a study obtained scores that indicate severe impairment.<ref name="FrithAlex">{{cite journal |author=Frith U |title=Emanuel Miller lecture: confusions and controversies about Asperger syndrome |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=45 |issue=4 |pages=672–86 |year=2004 |pmid=15056300 |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00262.x}} The study to which Frith refers is {{cite journal | author = Hill E, Berthoz S, Frith U |year = 2004 | title = Brief report: cognitive processing of own emotions in individuals with autistic spectrum disorder and in their relatives | journal =Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | volume = 34 | issue = 2 | pages = 229–235 | doi=10.1023/B:JADD.0000022613.41399.14}}</ref> Other researchers concur that both conditions are characterized by core disturbances in speech and language and social relationships<ref name="Fitzgerald & Bellgrove 2006">{{cite journal |author=Fitzgerald M, Bellgrove MA |title=The overlap between alexithymia and Asperger's syndrome |journal=Journal of autism and developmental disorders |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=573–6 |year=2006 |pmid=16755385 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0096-z|accessdate = 2007-04-11}}</ref><ref name="Hill & Berthoz 2006">{{cite journal | author = Hill E, Berthoz S| month = May | year = 2006 | title = Response to “Letter to the Editor: The Overlap Between Alexithymia and Asperger's syndrome”, Fitzgerald and Bellgrove, Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(4)| journal = Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders | volume = 36 | issue = 8 | pages = 1143–1145 | doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0287-7}}</ref> and the limbic system and prefrontal cortex may be involved in both.<ref name="Baskin"/><ref name="Tani"/> Alexithymic traits in AS may be linked to depression or anxiety;<ref name="FrithAlex"/> the mediating factors are unknown and it is possible that alexithymia predisposes a person to anxiety.<ref name="Tani">{{cite journal |author=Tani P, Lindberg N, Joukamaa M, ''et al'' |title=Asperger syndrome, alexithymia and perception of sleep |journal=Neuropsychobiology |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=64–70 |year=2004 |pmid=14981336 |doi=10.1159/000076412}}</ref> | |||

| *{{cite journal |author= Fitzgerald M, Bellgrove MA |title= The overlap between alexithymia and Asperger's syndrome |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=573–6 |year=2006 |pmid=16755385 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0096-z}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |author= Hill E, Berthoz S |year=2006 |title= Response |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |volume=36 |issue=8 |pages=1143–5 |doi=10.1007/s10803-006-0287-7 |pmid=17080269}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |journal= PLoS ONE |year=2007 |volume=2 |issue=9 |pages=e883 |title= Self-referential cognition and empathy in autism |author= Lombardo MV, Barnes JL, Wheelwright SJ, Baron-Cohen S |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0000883 |pmid=17849012 |url=http://www.plosone.org/article/fetchArticle.action?articleURI=info:doi/10.1371/journal.pone.0000883}}</ref> Although AS, lower sleep quality, and alexithymia are associated, their causal relationship is unclear.<ref name=Tani>{{cite journal |author= Tani P, Lindberg N, Joukamaa M ''et al.'' |title= Asperger syndrome, alexithymia and perception of sleep |journal= Neuropsychobiology |volume=49 |issue=2 |pages=64–70 |year=2004 |pmid=14981336 |doi=10.1159/000076412}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Causes== | ||

| {{ |

{{see|Causes of autism}} | ||

| Asperger described common symptoms among his patients' family members, especially fathers, and research supports this observation and suggests a genetic contribution to Asperger syndrome. Although no specific gene has yet been identified, multiple factors are believed to play a role in the ] of autism, given the ] variability seen in this group of children.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name="Foster"/> Evidence for a genetic link is the tendency for AS to run in families and an observed higher ] of family members who have behavioral symptoms similar to AS but in a more limited form (for example, slight difficulties with social interaction, language, or reading).<ref name=NINDS/> Most research suggests that all autism spectrum disorders have shared genetic mechanisms, but AS may have a stronger genetic component than autism.<ref name="McPartland"/> There is probably a common group of genes where particular ]s render an individual vulnerable to developing AS; if this is the case, the particular combination of alleles would determine the severity and symptoms for each individual with AS.<ref name=NINDS/> | |||

| Asperger's Disorder is defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) by six main criteria.<ref name=BehaveNet/> | |||

| A few ASD cases have been linked to exposure to ]s (agents that cause ]s) during the first eight weeks from ]. Although this does not exclude the possibility that ASD can be initiated or affected later, it is strong evidence that it arises very early in development.<ref name=Arndt>{{cite journal |journal= Int J Dev Neurosci |date=2005 |volume=23 |issue=2–3 |pages=189–99 |title= The teratology of autism |author= Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM |doi=10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.11.001 |pmid=15749245}}</ref> Many environmental factors have been hypothesized to act after birth, but none has been confirmed by scientific investigation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=] |title= Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning |journal= Acta Paediatr |volume=94 |issue=1 |date=2005 |pages=2–15 |pmid=15858952}}</ref> | |||

| The ICD-10 criteria are almost identical to DSM-IV:<ref name="Fitzgerald"/> ICD-10 adds the statement that motor clumsiness is usual (although not necessarily a diagnostic feature); ICD-10 adds the statement that isolated special skills, often related to abnormal preoccupations, are common but are not required for diagnosis; and the DSM-IV requirement for clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning is not included in ICD-10.<ref name="Mattila"/><ref name="Baskin"/> | |||

| ==Mechanism== | |||

| The DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria have been criticized for being too broad and inadequate for assessing adults,<ref name=bwrw>{{cite journal |author=Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Robinson J, Woodbury-Smith M |title=The Adult Asperger Assessment (AAA): a diagnostic method |journal=Journal of autism and developmental disorders |volume=35 |issue=6 |pages=807–19 |year=2005 |pmid=16331530 |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0026-5 | url = http://www.autismresearchcentre.com/docs/papers/2006_BCetal_AAA.pdf | format = PDF}}</ref> overly narrow (particularly in relation to Hans Asperger's original description of individuals with AS),<ref name="Fitzgerald"/><ref>{{cite journal |author=Mayes SD, Calhoun SL, Crites DL |title= Does DSM-IV Asperger's disorder exist? |journal= Journal of abnormal child psychology |volume=29 |issue=3 |pages=263–71 |year=2001 |pmid=11411788}}</ref> and vague;<ref name="EhlGill">Ehlers S, Gillberg C. "The epidemiology of Asperger's syndrome: a total population study." ''J Child Psychol Psychiatry.'' 1993 Nov;34(8):1327–50. PMID 8294522 </ref> results of a large study in 2007 comparing the four sets of criteria point to a "huge need to reconsider the diagnostic criteria of AS."<ref name="Mattila"/> The diagnoses of AS or HFA are sometimes used interchangeably; the same child can receive different diagnoses depending on the screening tool.<ref name="NINDS"/> Diagnoses may be influenced by non-technical issues, such as availability of government benefits for one condition but not the other.<ref>Attwood, T (2003). (PDF). Sacramento Asperger Syndrome Information & Support. Retrieved on ].</ref> The 2007 study found complete overlap across all sets of diagnostic criteria in the impairment of social interaction with the exception of four cases not diagnosed by the Szatmari et al. criteria because of its emphasis on social solitariness. Lack of overlap was strongest in the language delay and odd speech requirements of the Gillberg and the Szatmari requirements relative to DSM-IV and ICD-10, in the differing requirements regarding general delays, and in DSM's requirement for impairment.<ref name="Mattila"/> | |||

| {{further|]}} | |||

| Asperger syndrome appears to result from developmental factors that affect many or all functional brain systems, as opposed to localized effects.<ref name=Mueller>{{cite journal |journal= Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev |date=2007 |volume=13 |issue=1 |pages=85–95 |title= The study of autism as a distributed disorder |author=Müller RA |doi=10.1002/mrdd.20141 |pmid=17326118}}</ref> Although the specific underpinnings of AS or factors that distinguish it from other ASDs are unknown, and no clear pathology common to individuals with AS has emerged,<ref name=McPartland/> it is still possible that AS's mechanism is separate from other ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Aust N Z J Psychiatry |year=2002 |volume=36 |issue=6 |pages=762–70 |title= A clinical and neurobehavioural review of high-functioning autism and Asperger's disorder |author= Rinehart NJ, Bradshaw JL, Brereton AV, Tonge BJ |pmid=12406118}}</ref> ] studies and the associations with teratogens strongly suggest that the mechanism includes alteration of brain development soon after conception.<ref name=Arndt/> Abnormal migration of embryonic cells during fetal development may affect the final structure and connectivity of the brain, resulting in alterations in the neural circuits that control thought and behavior.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Berthier ML, Starkstein SE, Leiguarda R |title=Developmental cortical anomalies in Asperger's syndrome: neuroradiological findings in two patients |journal=J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci |volume=2 |issue=2 |pages=197–201 |year=1990 |pmid=2136076}}</ref> Several theories of mechanism are available; none are likely to be complete explanations.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R |title= Time to give up on a single explanation for autism |journal= Nat Neurosci |date=2006 |volume=9 |issue=10 |pages=1218–20 |pmid=17001340 |doi=10.1038/nn1770}}</ref> | |||

| ] provides some evidence for both underconnectivity and mirror neuron theories.<ref name=Just/><ref name=Iacoboni/>]] | |||

| Signs suggestive of AS are often noted by a general practitioner or pediatrician during a routine developmental check up. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke advise that this be followed up with a comprehensive team evaluation to either confirm or exclude a diagnosis of AS.<ref name="McPartland"/> Foster and King state that the determination of whether there is a family history of autism spectrum conditions can be important.<ref name="Foster"/> Fitzgerald states that a multidisciplinary team approach can be critical to avoiding misdiagnosis;:<ref name="Fitzgerald"/> an accurate assessment of the individual's strengths and weaknesses is claimed to be more useful than a diagnostic label.<ref name="McPartland"/> Delayed or mistaken diagnosis is regarded as a serious problem that can be traumatic for individuals and families; diagnosis based solely on a neurological, speech and language, or educational attainment may yield only a partial diagnosis.<ref name=Fitzgerald>{{cite journal |journal= Adv Psychiatr Treat |year=2001 |volume=7 |issue=4 |pages=310–8 |title= Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Asperger syndrome |author= Fitzgerald M, Corvin A |url=http://apt.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/7/4/310}}</ref> | |||

| The underconnectivity theory hypothesizes underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.<ref name=Just>{{cite journal |journal= Cereb Cortex |year=2007 |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=951-61 |title= Functional and anatomical cortical underconnectivity in autism: evidence from an FMRI study of an executive function task and corpus callosum morphometry |author= Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Kana RK, Minshew NJ |doi=10.1093/cercor/bhl006 |pmid=16772313 |url=http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/17/4/951}}</ref> It maps well to general-processing theories such as ], which hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Happé F, ] |title= The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders |journal= J Autism Dev Disord |date=2006 |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=5–25 |doi=10.1007/s10803-005-0039-0 |pmid=16450045}}</ref> | |||

| The ] (MNS) theory hypothesizes that alterations to the development of the MNS interfere with imitation and lead to Asperger's core feature of social impairment.<ref name=Iacoboni>{{cite journal |journal= Nat Rev Neurosci |date=2006 |volume=7 |issue=12 |pages=942–51 |title= The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction |author= Iacoboni M, Dapretto M |doi=10.1038/nrn2024| pmid=17115076}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |journal= Sci Am |year=2006 |volume=295 |issue=5 |pages=62–9 |title= Broken mirrors: a theory of autism |author= ], Oberman LM |pmid=17076085}}</ref> For example, one study found that activation is delayed in the core circuit for imitation in individuals with AS.<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Ann Neurol |year=2004 |volume=55 |issue=4 |pages=558–62 |title= Abnormal imitation-related cortical activation sequences in Asperger's syndrome |author= Nishitani N, Avikainen S, Hari R |doi=10.1002/ana.20031 |pmid=15048895}}</ref> This theory maps well to social cognition theories like the ], which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from impairments in ascribing mental states to oneself and others,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U|title=Does the autistic child have a 'theory of mind'? |journal=Cognition |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=37–46 |year=1985 |doi=10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 |pmid=2934210 |url=http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/~aleslie/Baron-Cohen%20Leslie%20&%20Frith%201985.pdf |format = PDF | accessdate=2007-06-28}}</ref> or ], which hypothesizes that autistic individuals can systematize internal operation to handle internal events but are less effective at ] by handling events generated by other agents.<ref>{{cite journal |author= ] |title= The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism |journal= Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry |date=2006 |volume=30 |issue=5 |pages=865–72 |doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010 |pmid=16519981}}</ref> | |||

| It has been found that parents of children with AS can typically trace differences in their children's development to as early as 30 months of age, although diagnosis is not made on average until the age of 11.<ref name="Foster">{{cite journal |author=Foster B, King BH |title=Asperger syndrome: to be or not to be? |journal=Curr. Opin. Pediatr. |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=491–94 |year=2003 |pmid=14508298}}</ref> By definition, children with AS develop language and self-help skills on schedule, so early signs may not be apparent and the condition may not be diagnosed until later childhood. Impairment in social interaction is sometimes not in evidence until a child attains an age at which these behaviors become important; social disabilities are often first noticed when children encounter peers in daycare or preschool.<ref name="McPartland"/> Diagnosis is most commonly made between the ages of four and eleven, and one study suggests that diagnosis cannot be rendered reliably before age four.<ref name="McPartland"/> | |||

| Other possible mechanisms include ] dysfunction<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Am J Psychiatry |year=2006 |volume=163 |issue=5 |pages=934–6 |title= Cortical serotonin 5-HT<sub>2A</sub> receptor binding and social communication in adults with Asperger's syndrome: an in vivo SPECT study |author= Murphy DG, Daly E, Schmitz N ''et al.'' |doi=10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.934 |pmid=16648340}}</ref> and ] dysfunction.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Cerebellum |year=2005 |volume=4 |issue=4 |pages=279–89 |title= Behavioural aspects of cerebellar function in adults with Asperger syndrome |author= Gowen E, Miall RC |doi=10.1080/14734220500355332 |pmid=16321884}}</ref> | |||

| Asperger syndrome can be misdiagnosed as a number of other conditions, leading to medications that are unnecessary or even worsen behavior.<ref name="Fitzgerald"/> | |||

| == |

==Screening== | ||

| Parents of children with Asperger syndrome can typically trace differences in their children's development to as early as 30 months of age.<ref name=Foster/> Developmental screening during a routine check-up by a general practitioner or pediatrician may identify signs that warrant further investigation.<ref name=McPartland/><ref name=NINDS/> The diagnosis of AS is complicated by the use of several different screening instruments.<ref name=NINDS/><ref name=EhlGill/> None have been shown to reliably differentiate between AS and other ASDs. The current "gold standard" in diagnosing ASDs uses the ] (ADI-R)—a semistructured parent interview—and the ] (ADOS)—a conversation and play-based interview with the child.<ref name=McPartland/> | |||

| {{see also|Causes of autism}} | |||

| Asperger described common symptoms among his patients' family members, especially fathers,<ref name="McPartland"/> and research supports this observation and suggests a genetic contribution to AS.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Foster"/> Although no specific gene has yet been identified, multiple factors are believed to play a role in the ] of autism, given the ] variability seen in this group of children.<ref name="Foster"/> Evidence for a genetic link is the tendency for AS to run in families and an observed higher ] of family members who have behavioral symptoms similar to AS but in a more limited form (for example, slight difficulties with social interaction, language, or reading).<ref name=NINDS/> Most research suggests that all autism spectrum disorders have shared genetic mechanisms, but AS may have a stronger genetic component than autism.<ref name="McPartland"/> There is probably a common group of genes where particular ]s render an individual vulnerable to developing AS; if this is the case, the particular combination of alleles would determine the severity and symptoms for each individual with AS.<ref name=NINDS/> No gene has been identified for AS, although studies suggest specific genetic abnormalities: such as various types of ]s in chromosomes ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]; autosomal fragile site, ], fragile Y, and 21pþ.<ref name="McPartland"/> Anomalies in ] were related to the diagnosis of autism and Asperger syndrome in five children. The ] tip of the long arm of the chromosome 22 contains the SHANK3 gene, which is thought to have a role in the maturation and maintenance of ]s. The deletion of this part of the chromosome (]) was found in low-functioning autistic subjects, and its duplication observed in a subject diagnosed with Asperger syndrome.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Durand CM, Betancur C, Boeckers TM, ''et al'' |title=Mutations in the gene encoding the synaptic scaffolding protein SHANK3 are associated with autism spectrum disorders |journal=Nat. Genet. |volume=39 |issue=1 |pages=25–27 |year=2007 |pmid=17173049 |doi=10.1038/ng1933 | accessdate = 2007-08-13 | laysummary = http://www.cosmosmagazine.com/node/937 | laysource = Cosmos magazine | laydate = 2006-12-18}}</ref> | |||

| ==Diagnosis== | |||

| Environmental factors may interact with genetic influences to play a role in the cause of ASDs, but research has identified no consistent correlations.<ref name="McPartland"/> There is strong evidence that genetic factors play a major role in the causes of autism spectrum disorders, while none of the possible environmental causes has been confirmed by scientific investigation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Wing L, Potter D |title=The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising? |journal=Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=151–61 |year=2002 |pmid=12216059 |doi=10.1002/mrdd.10029}}</ref> | |||

| {{main|Diagnosis of Asperger syndrome}} | |||

| Standard diagnostic criteria require impairment in social interaction, and repetitive and stereotyped behaviors and interests, without significant delay in language or cognitive development. Unlike the international standard,<ref name=ICD-10-F84.0/> U.S. criteria also require significant impairment in day-to-day functioning.<ref name=BehaveNet/> Other sets of diagnostic criteria have been proposed by ]<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Can J Psychiatry |year=1989 |volume=34 |issue=6 |pages=554–60 |title= Asperger's syndrome: a review of clinical features |author= Szatmari P, Bremner R, Nagy J |pmid=2766209}}</ref> and by ].<ref name=Gill>{{cite journal |journal= J Child Psychol Psychiatry |year=1989 |volume=30 |issue=4 |pages=631–8 |title= Asperger syndrome—some epidemiological considerations: a research note |author= Gillberg IC, Gillberg C |doi=10.1111/j.1469-7610.1989.tb00275.x |pmid=2670981}}</ref> | |||

| ==Mechanism== | |||

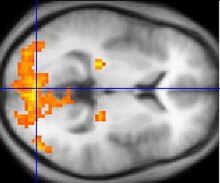

| ] techniques have revealed structural and functional differences in specific regions of the brains of AS children; these are most likely caused by the abnormal migration of embryonic cells during fetal development, which affects the final structure and connectivity of the brain, resulting in alterations in the neural circuits that control thought and behavior.<ref name=NINDS/> Although progress has been made, brain imaging technologies have failed to identify the specific underpinnings of AS or factors that distinguish it from other ASDs and no clear pathology common to individuals with AS has emerged.<ref name="McPartland"/> ] has provided interesting findings, but no convincing evidence reproducibly indicates differences among AS and other ASDs.<ref name="McPartland"/> | |||

| Diagnosis is most commonly made between the ages of four and eleven.<ref name="McPartland"/> A comprehensive assessment involves a multidisciplinary team<ref name="Baskin"/><ref name=NINDS/><ref name=Fitzgerald/> that observes across multiple settings,<ref name=McPartland/> and includes neurological and genetic assessment as well as tests for cognition, psychomotor function, verbal and nonverbal strengths and weaknesses, style of learning, and skills for independent living.<ref name=NINDS/> Delayed or mistaken diagnosis can be traumatic for individuals and families; for example, misdiagnosis can lead to medications that worsen behavior.<ref name=Fitzgerald/> Many children with AS are initially misdiagnosed with ] (ADHD).<ref name="McPartland"/> Diagnosing adults is more challenging, as standard diagnostic criteria are designed for children and the expression of AS changes with age.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Tantam D |title=The challenge of adolescents and adults with Asperger syndrome |journal=Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am|volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=143–63 |year=2003 |pmid=12512403 |url = http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000536/fulltext}}</ref> Conditions that must be considered in a ] include other ASDs, the ] spectrum, ADHD, ], ], ], ],<ref name=Fitzgerald>{{cite journal |author= Fitzgerald M, Corvin A |date=2001 |url=http://apt.rcpsych.org/cgi/content/full/7/4/310 |title= Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of Asperger syndrome |journal= Adv Psychiatric Treat |volume=7 |issue=4 |pages=310–8}}</ref> ],<ref name=RapinTS/> ] and ].<ref name=Foster>{{cite journal |journal= Curr Opin Pediatr |year=2003 |volume=15 |issue=5 |pages=491–4 |title= Asperger syndrome: to be or not to be? |author= Foster B, King BH |pmid=14508298}}</ref> | |||

| One study reported a reduction of brain activity in the ] of AS children when they were asked to respond to tasks that required them to use their judgment. These differences in activity were also seen when children were asked to respond to facial expressions.<ref name=NINDS/> Another study, of brain function in adults with AS, revealed abnormal levels of some proteins and demonstrated a correlation between these levels and obsessive and repetitive behaviors.<ref name=NINDS/> Possible differences in AS include:<ref name="McPartland"/> ] anomalies,<ref>Kwon H, Ow AW, Pedatella KE, ''et al.'' "Voxel-based morphometry elucidates structural neuroanatomy of high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome." ''Dev Med Child Neurol.'' 2004 Nov;46(11):760–64. PMID 15540637</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=McAlonan GM, Daly E, Kumari V, ''et al'' |title=Brain anatomy and sensorimotor gating in Asperger's syndrome |journal=Brain |volume=125 |issue=Pt 7 |pages=1594–606 |year=2002 |pmid=12077008}}</ref> left ] damage,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Jones PB, Kerwin RW |title=Left temporal lobe damage in Asperger's syndrome |journal=The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science |volume=156 |issue= |pages=570–2 |year=1990 |pmid=2386870}}</ref> and left ] hypoperfusion.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Ozbayrak KR, Kapucu O, Erdem E, Aras T |title=Left occipital hypoperfusion in a case with the Asperger syndrome |journal=Brain Dev. |volume=13 |issue=6 |pages=454–56 |year=1991 |pmid=1810164}}</ref> Other possible causative mechanisms include ] dysfunction and ] dysfunction.<ref name="Murphy">Murphy DG, Daly E, Schmitz N, ''et al.'' "Cortical serotonin 5-HT2A receptor binding and social communication in adults with Asperger's syndrome: an ''in vivo'' SPECT study." ''Am J Psychiatry.'' 2006 May;163(5):934–36. PMID 16648340</ref><ref>Gowen E, Miall RC. "Behavioural aspects of cerebellar function in adults with Asperger syndrome." ''Cerebellum.'' 2005;4(4):279–89. PMID 16321884</ref> Differences in brain volumes—such as enlarged ] and ]—have been linked to autism;<ref>Schumann CM, Hamstra J, Goodlin-Jones BL, ''et al.'' "The amygdala is enlarged in children but not adolescents with autism; the hippocampus is enlarged at all ages." ''J Neurosci.'' 2004 ];24(28):6392–6401. PMID 15254095</ref> the most robust findings are of the reduced size of the ] and rapid brain growth and increased brain volume in early childhood that normalizes in mid-childhood.<ref>Minshew N, Sweeney J, Bauman M, ''et al''. Neurologic aspects of autism. In: Volkmar F, Paul R, Klin A, ''et al.'', eds. ''Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders'', vol 1. 3rd edition. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 473–514. As cited in, McPartland J, Klin A (2006).</ref> Other research suggests abnormal right hemisphere functioning in AS,<ref>{{cite journal |author=McKelvey JR, Lambert R, Mottron L, Shevell MI |title=Right-hemisphere dysfunction in Asperger's syndrome |journal=J. Child Neurol. |volume=10 |issue=4 |pages=310–14 |year=1995 |pmid=7594267}} As cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006).</ref> dysfunction in brain regions affecting social cognition,<ref>Schultz R, Robins D. Functional neuroimaging studies of autism spectrum disorders. In: Volkmar F, Paul R, Klin A, et al, editors. ''Handbook of autism and pervasive developmental disorders'', vol 1. 3rd edition. Hoboken (NJ): John Wiley & Sons; 2005. p. 515–33. As cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006).</ref> and problems with functional connectivity among separate brain regions.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Welchew DE, Ashwin C, Berkouk K, ''et al'' |title=Functional disconnectivity of the medial temporal lobe in Asperger's syndrome |journal=Biol. Psychiatry |volume=57 |issue=9 |pages=991–98 |year=2005 |pmid=15860339 |doi=10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.028}} As cited in McPartland J, Klin A (2006).</ref> | |||

| Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases. The cost of screening and diagnosis and the challenge of obtaining payment can inhibit or delay diagnosis. Conversely, the increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has motivated providers to overdiagnose ASD.<ref>{{cite journal |author= Shattuck PT, Grosse SD |title= Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders |journal= Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev |date=2007 |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=129–35 |doi=10.1002/mrdd.20143 |pmid=17563895}}</ref> There are indications AS has been diagnosed more frequently in recent years, partly as a residual diagnosis for children of normal intelligence who do not have autism but have social difficulties. There are questions about the external validity of the AS diagnosis, that is, it is unclear whether there is a practical benefit in distinguishing AS from HFA and from PDD-NOS;<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |year=2003 |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=1–13 |title= Asperger syndrome: diagnosis and external validity |author= Klin A, Volkmar FR |pmid=12512395 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000524/fulltext}}</ref> the same child can receive different diagnoses depending on the screening tool.<ref name="NINDS"/> | |||

| ] proposes a model for Asperger's<ref>Lawson J, Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. "Empathising and systemising in adults with and without Asperger Syndrome." ''J Autism Dev Disord.'' 2004 Jun;34(3):301–10. PMID 15264498</ref> that extends the extreme male brain theory, which hypothesizes that autism is an extreme case of the male brain, defined psychometrically as individuals in whom ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Baron-Cohen S|title=The extreme male brain theory of autism|journal=Trends Cogn Sci|date=2002|volume=6|issue=6|pages=248–54|doi=10.1016/S1364-6613(02)01904-6|pmid=12039606}}</ref> Hyper-systemizing hypothesizes that autistic individuals can systematize—that is, they can develop internal rules of operation to handle internal events—but are less effective at ] by handling events generated by other agents.<ref name="hypersystem">{{cite journal|author=]|title=The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism|journal=Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry|date=2006|volume=30|issue=5|pages=865–72|doi=10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.01.010|pmid=16519981}}</ref> This in turn is related to the earlier ], which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from an inability to ascribe mental states to oneself and others.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U|title=Does the autistic child have a 'theory of mind'? |journal=Cognition |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=37–46 |year=1985 |doi=10.1016/0010-0277(85)90022-8 |pmid=2934210 |url=http://ruccs.rutgers.edu/~aleslie/Baron-Cohen%20Leslie%20&%20Frith%201985.pdf |format = PDF | accessdate=2007-06-28}}</ref> Two studies showed that Asperger subjects had a second-order theory of mind; compared to younger or more impaired autistic individuals, they were able to understand problems of the type "Peter thinks that Jane thinks that ..." although their explanations of their solutions did not use mental states.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Bowler DM |title="Theory of mind" in Asperger's syndrome |journal=Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines |volume=33 |issue=5 |pages=877–93 |year=1992 |pmid=1378848 |doi=}} </ref> There is some evidence that the mind-reading capacity of children in the higher-functioning range of the autistic spectrum are intact.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rieffe C, Meerum Terwogt M, Stockmann L |title=Understanding atypical emotions among children with autism |journal=Journal of autism and developmental disorders |volume=30 |issue=3 |pages=195–203 |year=2000 |pmid=11055456 |doi=}}</ref> | |||

| ==Treatment== | ==Treatment== | ||

| {{ |

{{see|Autism therapies}} | ||

| Asperger syndrome treatment attempts to manage distressing symptoms and to teach age-appropriate social, communication and vocational skills that are not naturally acquired during development,<ref name="McPartland"/> with intervention tailored to the needs of the individual child, based on multidisciplinary assessment.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Compr Psychiatry |year=2004 |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=184–91 |title= Asperger's disorder: a review of its diagnosis and treatment |author= Khouzam HR, El-Gabalawi F, Pirwani N, Priest F |doi=10.1016/j.comppsych.2004.02.004 |pmid=15124148}}</ref> Although progress has been made, data supporting the efficacy of particular interventions are limited.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref>{{cite journal |author= Attwood T |title= Frameworks for behavioral interventions |journal= Child Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=65–86 |year=2003 |pmid=12512399 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000548/fulltext}}</ref> | |||

| The ideal treatment for AS coordinates therapies that address |

The ideal treatment for AS coordinates therapies that address core symptoms of the disorder, including poor communication skills and obsessive or repetitive routines. While most professionals agree that the earlier the intervention, the better, there is no single best treatment package.<ref name=NINDS/> AS treatment resembles that of other high-functioning ASDs, except that it takes into account the linguistic capabilities, verbal strengths, and nonverbal vulnerabilities of individuals with AS.<ref name=McPartland/> A typical treatment program generally includes:<ref name=NINDS/> | ||

| * the training of ] for more effective interpersonal interactions;<ref>{{cite journal |author= Krasny L, Williams BJ, Provencal S, Ozonoff S |title= Social skills interventions for the autism spectrum: essential ingredients and a model curriculum |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=107–22 |year=2003 |pmid=12512401 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000512/fulltext}}</ref> | |||

| * the training of ] for more effective interpersonal interactions; | |||

| * ] to improve |

* ] to improve stress management relating to anxiety or explosive emotions,<ref name=Myles>{{cite journal |author= Myles BS |title= Behavioral forms of stress management for individuals with Asperger syndrome |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=123–41 |year=2003 |pmid=12512402 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000482/fulltext}}</ref> and to cut back on obsessive interests and repetitive routines; | ||

| * ], for coexisting conditions such as depression and anxiety; | * ], for coexisting conditions such as depression and anxiety;<ref name=Towbin/> | ||

| * ] or ] to assist with poor ] and ]; | * ] or ] to assist with poor ] and ]; | ||

| * specialized ] |

* social communication intervention, which is specialized ] to help with the ] of the give and take of normal conversation;<ref>{{cite journal |author=Paul R |title= Promoting social communication in high functioning individuals with autistic spectrum disorders |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=87–106 |year=2003 |pmid=12512400 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000470/fulltext}}</ref> | ||

| * the training and support of parents, particularly in behavioral techniques to use in the home. | * the training and support of parents, particularly in behavioral techniques to use in the home. | ||

| Of the many studies on behavior-based early intervention programs, most are case studies of up to five participants, and typically examine a few problem behaviors such as ], ], noncompliance, ], or spontaneous language; unintended ] are largely ignored.<ref name=interrev>{{cite journal |author=Matson JL |title=Determining treatment outcome in early intervention programs for autism spectrum disorders: a critical analysis of measurement issues in learning based interventions |journal= Res Dev Disabil |volume=28 |issue=2 |pages=207–18 |year=2007 |pmid=16682171 |doi=10.1016/j.ridd.2005.07.006}}</ref> Despite the popularity of social skills training, its effectiveness is not firmly established.<ref>{{cite journal|journal=J Autism Dev Disord|date=2007|title=Social skills interventions for children with Asperger's syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations|author=Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ|doi=10.1007/s10803-007-0402-4|pmid=17641962}}</ref> A randomized controlled study of a model for training parents in problem behaviors in their children with AS showed that parents attending a one-day workshop or six individual lessons reported fewer behavioral problems, while parents receiving the individual lessons reported less intense behavioral problems in their AS children.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sofronoff K, Leslie A, Brown W |title=Parent management training and Asperger syndrome: a randomized controlled trial to evaluate a parent based intervention |journal=Autism |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=301-17 |year=2004 |pmid=15358872 |doi=10.1177/1362361304045215}}</ref> Vocational training is important to teach job interview etiquette and workplace behavior to older children and adults with AS, and organization software and personal data assistants to improve the work and life management of people with AS are useful.<ref name="McPartland"/> | |||

| No medications |

No medications directly treat the core symptoms of AS.<ref name=Towbin>{{cite journal |author= Towbin KE |title= Strategies for pharmacologic treatment of high functioning autism and Asperger syndrome |journal= Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am |volume=12 |issue=1 |pages=23–45 |year=2003 |pmid=12512397 |url=http://www.childpsych.theclinics.com/article/PIIS1056499302000494/fulltext}}</ref> Although research into the efficacy of pharmaceutical intervention for AS is limited,<ref name="McPartland"/> it is essential to diagnose and treat ] conditions.<ref name="Baskin"/> Deficits in self-identifying emotions or in observing effects of one's behavior on others can make it difficult for individuals with AS to see why they should take medication.<ref name=Towbin/> Medication can be effective in combination with behavioral interventions and environmental accommodations in treating comorbid symptoms such as ], ], inattention and aggression.<ref name="McPartland"/> The ] medications ] and ] have been shown to reduce the associated symptoms of AS;<ref name="McPartland"/> risperidone can reduce repetitive and self-injurious behaviors, aggressive outbursts and impulsivity, and improve stereotypical patterns of behavior and social relatedness. The ]s (SSRIs) ], ] and ] have been effective in treating restricted and repetitive interests and behaviors.<ref name="McPartland"/><ref name="Baskin"/><ref name="Foster"/> | ||

| Care must be taken in the management of ]; abnormalities in ], ] times, and an increased risk of ] have been raised as concerns with these medications<ref name="Newcomer">{{cite journal |author=Newcomer JW |title=Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk |journal= |

Care must be taken in the management of ]; abnormalities in ], ] times, and an increased risk of ] have been raised as concerns with these medications,<ref name="Newcomer">{{cite journal |author=Newcomer JW |title=Antipsychotic medications: metabolic and cardiovascular risk |journal= J Clin Psychiatry |volume=68 |issue= suppl 4 |pages=8–13 |year=2007 |pmid=17539694}}</ref><ref name="Chavez">{{cite journal |author=Chavez B, Chavez-Brown M, Sopko MA, Rey JA |title=Atypical antipsychotics in children with pervasive developmental disorders |journal=Pediatr Drugs |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=249–66 |year=2007 |pmid=17705564}} </ref> along with serious long-term neurological side effects.<ref name=interrev/> SSRIs can lead to manifestations of behavioral activation such as increased impulsivity, aggression and sleep disturbance.<ref name="Foster"/> Weight gain and fatigue are commonly reported side effects of risperidone, which may also lead to increased risk for ] symptoms such as restlessness and ]<ref name="Foster"/> and increased serum ] levels.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Staller J |title=The effect of long-term antipsychotic treatment on prolactin |journal= J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=317–26 |year=2006 |pmid=16768639 |doi=10.1089/cap.2006.16.317}}</ref> Sedation and weight gain are more common with olanzapine,<ref name="Chavez"/> which has also been linked with diabetes.<ref name="Newcomer"/> Sedative side-effects in school-age children<ref>{{cite journal |journal= Ann Pharmacother |year=2007 |volume=41 |issue=4 |pages=626–34 |title= Use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of autistic disorder |author= Stachnik JM, Nunn-Thompson C |doi=10.1345/aph.1H527 |pmid=17389666}}</ref> have ramifications for classroom learning. Individuals with AS may be unable to identify and communicate their internal moods and emotions or to tolerate side effects that for most people would not be problematic.<ref>{{cite journal |title= Asperger syndrome and high functioning autism: research concerns and emerging foci |journal= Curr Opin Psychiatry |volume=16 |issue=5 |pages=535–542 |date=2003 |author= Blacher J, Kraemer B, Schalow M |doi=10.1097/01.yco.0000087260.35258.64}}</ref> | ||

| ===Shift in view=== | |||

| Autistic people have contributed to a shift in perception of autism spectrum disorders as complex ]s rather than diseases that must be cured.<ref>Williams, Charmaine C. "In search of an Asperger culture," in Stoddart, Kevin. (Ed.) (2005), p. 246.</ref> Proponents of this view reject the notion that there is an "ideal" brain configuration and that any deviation from the norm is ]; they demand tolerance for what they call their neurodiversity.<ref>Williams (2005), p. 246. Williams writes: "The life prospects of people with AS would change if we shifted from viewing AS as a set of dysfunctions, to viewing it as a set of differences that have merit."</ref> These views are the basis for the ] and ] movements.<ref>Dakin, Chris J. "Life on the outside: A personal perspective of Asperger syndrome," in Stoddart, Kevin (Ed.) (2005), pp. 352–353.</ref> | |||

| Researcher ] has argued that both AS and high-functioning autism are "differences" and not necessarily "disabilities."<ref name="B-CDisability">Baron-Cohen, Simon. "Is asperger syndrome/high-functioning autism necessarily a disability?" ''Development and Psychopathology''. 2000 Summer;12(3):489–500. PMID 11014749 </ref> In proposing the more neutral term "difference", he suggests a subtle but important shift of emphasis to characterization of autism as a different cognitive style; this small shift in a term could mean the difference between a diagnosis of AS being received as a family tragedy, or as interesting information, such as learning that a child is left-handed. People with Asperger's, according to Baron-Cohen, "might not necessarily be disabled in an environment in which an exact mind, attracted to detecting small details, is an advantage".<ref name="B-CDisability"/> Attwood argues that "... the unusual profile of abilities that we define as Asperger's Syndrome has probably been an important and valuable characteristic of our species throughout evolution".<ref name=Att1>Attwood, T (2007). ''The Complete Guide to Asperger's'', Jessica Kingsley Publishers, London, UK, p. 12.</ref> | |||

| ==Prognosis== | ==Prognosis== | ||

| As of |

As of 2007, no studies addressing the long-term outcome of individuals with Asperger syndrome are available and there are no systematic long-term follow-up studies of children with AS.<ref name="Klin"/> Individuals with AS appear to have normal ] but have an increased ] of ] ] conditions such as ] and ] that may significantly affect ]. Although social impairment is lifelong, outcome is generally more positive than with individuals with lower functioning autism spectrum disorders;<ref name="McPartland"/> for example, ASD symptoms are more likely to diminish with time in children with AS or HFA.<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Pediatrics |year=2005 |volume=116 |issue=1 |pages=117–22 |title= Modeling clinical outcome of children with autistic spectrum disorders |author= Coplan J, Jawad AF |doi=10.1542/peds.2004-1118 |pmid=15995041 |url=http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/116/1/117 |laysummary=http://stokes.chop.edu/publications/press/?ID=181 |laysource=press release |laydate=2005-07-05}}</ref> Although most students with AS/HFA have average mathematical ability and test slightly worse in mathematics than in general intelligence, some are gifted in mathematics<ref>{{cite journal |journal=Autism |date=2007 |volume=11 |issue=6 |pages=547–56 |title= Mathematical ability of students with Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism |author= Chiang HM, Lin YH |doi=10.1177/1362361307083259 |pmid=17947290}}</ref> and AS has not prevented some adults from major accomplishments such as winning the ].<ref>{{cite news |author= Herera S |title= Mild autism has 'selective advantages' |url=http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7030731/ |date=2005-02-25 |accessdate=2007-11-14 |publisher=CNBC}}</ref> | ||

| Children with AS |

Children with AS may require ] services because of their social and behavioral difficulties although many attend regular education classes.<ref name="Klin"/> Adolescents with AS may exhibit ongoing difficulty with self-care, organization and disturbances in social and romantic relationships; despite high cognitive potential, most remain at home, although some do marry and work independently.<ref name="McPartland"/> The "different-ness" adolescents experience can be traumatic.<ref name="Moran">{{cite journal |author= Moran M |url=http://pn.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/41/19/21 |title= Asperger's may be answer to diagnostic mysteries |journal= Psychiatr News |year=2006 |volume=41 |issue=19 |pages=21}}</ref> Anxiety may stem from preoccupation over possible violations of routines and rituals, from being placed in a situation without a clear schedule or expectations, or from ];<ref name=McPartland/> the resulting stress may manifest as inattention, withdrawal, reliance on obsessions, hyperactivity, or aggressive or oppositional behavior.<ref name=Myles/> Depression is often the result of chronic frustration from repeated failure to engage others socially, and mood disorders requiring treatment may develop.<ref name="McPartland"/> | ||

| Education of families is critical in developing strategies for understanding strengths and weaknesses;<ref name="Baskin"/> |

Education of families is critical in developing strategies for understanding strengths and weaknesses;<ref name="Baskin"/> helping the family to cope improves outcome in children.<ref name=Tsatsanis/> Prognosis may be improved by diagnosis at a younger age that allows for early interventions, while interventions in adulthood are valuable but less beneficial.<ref name="Baskin"/> There are legal implications for individuals with AS as they run the risk of exploitation by others and may be unable to comprehend the societal implications of their actions.<ref name="Baskin"/> | ||

| ==Epidemiology== | ==Epidemiology== | ||

| {{see|Conditions comorbid to autism spectrum disorders}} | |||