| Revision as of 09:57, 1 August 2005 editEarth (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,753 edits →Chulalongkorn← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:07, 21 September 2005 edit undoCraigy144 (talk | contribs)31,329 edits →Chulalongkorn: rmvd deleted imageNext edit → | ||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

| At first the princes and other conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger and western-educated princes, resistance faded. The king could always argue that the only alternative was foreign rule. He found powerful allies in his brother Prince ], whom he made finance minister, and his brother-in-law Prince ], foreign minister for 38 years. In ] Devrawonge visited Europe to study government systems. On his recommendation the king established Cabinet government, an audit office and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganised and modernised. | At first the princes and other conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger and western-educated princes, resistance faded. The king could always argue that the only alternative was foreign rule. He found powerful allies in his brother Prince ], whom he made finance minister, and his brother-in-law Prince ], foreign minister for 38 years. In ] Devrawonge visited Europe to study government systems. On his recommendation the king established Cabinet government, an audit office and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganised and modernised. | ||

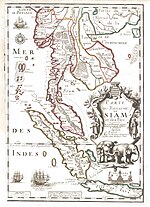

| ], showing the "lost territories"; it is still frequently reproduced in Thai atlases.{{ref|Thongchai153}}]] | |||

| In ] the French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the ]. The King appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British. | In ] the French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the ]. The King appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British. | ||

Revision as of 01:07, 21 September 2005

| Part of a series on the | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Thailand | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Timeline

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

From 1768 to 1932 the area of modern Thailand was dominated by Siam, an absolute monarchy with capitals briefly at Thonburi and later at Rattanakosin, both in modern-day Bangkok. The first half of this period was a time of consolidation of the kingdom's power, and was punctuated by periodic conflicts with Burma, Vietnam and the Lao states. The later period was one of engagement with the colonial powers of Britain and France, in which Siam managed to be the only southeast Asian country not to be colonised by a European country. Internally the kingdom developed into a centralised nation state with borders defined by its interaction with the Western powers. Significant economic and social progress was made, with an increase in foreign trade, the abolition of slavery and the expansion of education to the emerging middle class. However, there was no substantial political reform until the monarchy was overthrown in a military coup in 1932.

Thonburi period

In 1767, after dominating southeast Asia for almost 400 years, the Ayutthaya kingdom was brought down by invading Burmese armies, its capital burned, and its territory occupied by the invaders.

Despite its complete defeat and occupation by Burma, Siam made a rapid recovery. The resistance to Burmese rule was led by a noble of Chinese descent, Taksin, a capable military leader. Initially based at Chanthaburi in the south-east, within a year he had defeated the Burmese occupation army and re-established a Siamese state with its capital at Thonburi on the west bank of the Chao Phraya, 20km from the sea. In 1768 he was crowned as King Taksin (now officially known as Taksin the Great). He rapidly re-united the central Thai heartlands under his rule, and in 1769 he also occupied western Cambodia. He then marched south and re-established Siamese rule over the Malay Peninsula as far south as Penang and Terengganu. Having secured his base in Siam, Taksin attacked the Burmese in the north in 1774 and captured Chiang Mai in 1776, permanently uniting Siam and Lanna. Taksin's leading general in this campaign was Thong Duang, known by the title Chaophraya Chakri. In 1778 Chakri led a Siamese army which captured Vientiane and re-established Siamese domination over Laos.

Despite these successes, by 1779 Taksin was in political trouble at home. He seems to have developed a religious mania, alienating the powerful Buddhist monkhood by claiming to be a sotapanna or divine figure. He also attacked the Chinese merchant class, and foreign observers began to speculate that he would soon be overthrown. In 1782 Taksin sent his armies under Chakri to invade Cambodia, but while they were away a rebellion broke out in the area around the capital. The rebels, who had wide popular support, offered the throne to Chakri. Chakri marched back from Cambodia and deposed Taksin, who was secretly executed shortly after. Chakri ruled under the name Ramathibodi (he was posthumously given the name Phutthayotfa Chulalok), but is now generally known as King Rama I, first king of the Chakri dynasty. One of his first decisions was to move the capital across the river to the village of Bang Makok (meaning "place of olive plums"), which soon became the city of Bangkok. The new capital was located on the island of Rattanakosin, protected from attack by the river to the west and by a series of canals to the north, east and south. Siam thus acquired both its current dynasty and its current capital.

Bangkok period

Rama I

Rama I restored most of the social and political system of the Ayutthaya kingdom, promulgating new law codes, reinstating court ceremonies and imposing discipline on the Buddhist monkhood. His government was carried out by six great ministries headed by royal princes. Four of these administered particular territories: the Kalahom the south; the Mahatthai the north and east; the Phrakhlang the area immediately south of the capital; and the Krommueang the area around Bangkok. The other two were the ministry of lands (Krom Na) and the ministry of the royal court (Krom Wang). The army was controlled by the King's deputy and brother, the Uparat. The Burmese, seeing the disorder accompanying the overthrow of Taksin, invaded Siam again in 1785. Rama allowed them to occupy both the north and the south, but the Uparat led the Siamese army into western Siam and defeated the Burmese in a battle near Kanchanaburi. This was the last major Burmese invasion of Siam, although as late as 1802 Burmese forces had to be driven out of Lanna. In 1792 the Siamese occupied Luang Prabang and brought most of Laos under indirect Siamese rule. Cambodia was also effectively ruled by Siam. By the time of his death in 1809 Rama I had created a Siamese Empire dominating an area considerably larger than modern Thailand.

Rama II

The reign of Rama I's son Phuttaloetla Naphalai (now known as King Rama II) was relatively uneventful. The Chakri family now controlled all branches of Siamese government — since Rama I had 42 children, his brother the Uparat had 43 and Rama II had 73, there was no shortage of royal princes to staff the bureacracy, the army, the senior monkhood and the provincial governments. (Most of these were the children of concubines and thus not eligible to inherit the throne.) There was a confrontation with Vietnam, now becoming a major power in the region, over control of Cambodia in 1813, ending with the status quo restored. But during Rama II's reign western influences again began to be felt in Siam. In 1785 the British occupied Penang, and in 1819 they founded Singapore. Soon the British displaced the Dutch and Portuguese as the main western economic and political influence in Siam. The British objected to the Siamese economic system, in which trading monopolies were held by royal princes and businesses were subject to arbitrary taxation. In 1821 the government of British India sent a mission to demand that Siam lift restrictions on free trade — the first sign of an issue which was to dominate 19th century Siamese politics.

Rama III

Rama II died in 1824, and was peacfully succeeded by his son Chetsadabodin, who reigned as King Nangklao, now known as Rama III. Rama II's younger son, Mongkut, was ordered to become a monk to remove him from politics.

In 1825 the British sent another mission to Bangkok. They had by now annexed southern Burma and were thus Siam's neighbours to the west, and they were also extending their control over Malaya. The King was reluctant to give in to British demands, but his advisors warned him that Siam would meet the same fate as Burma unless the British were accommodated. In 1826, therefore, Siam concluded its first commercial treaty with a western power. Under the treaty, Siam agreed to establish a uniform taxation system, to reduce taxes on foreign trade and to abolish some of the royal monopolies. As a result, Siam's trade increased rapidly, many more foreigners settled in Bangkok, and western cultural influences began to spread. The kingdom became wealthier and its army better armed.

A Lao rebellion led by Anouvong was defeated in 1827, following which Siam destroyed Vientiane, carried out massive forced population transfers from Laos to the more securely held area of Isan, and divided the Lao mueang into smaller units to prevent another uprising. In 1842–1845 Siam waged a successful war with Vietnam, which tightened Siamese rule over Cambodia. Rama III's most visible legacy in Bangkok is the Wat Pho temple complex, which he enlarged and endowed with new temples.

Rama III regarded his brother Mongkut as his heir, although as a monk Mongkut could not openly assume this role. He used his long sojourn as a monk to acquire a western education from French and American missionaries, one of the first Siamese to do so. He learned English and Latin, and studied science and mathematics. The missionaries no doubt hoped to convert him to Christianity, but in fact he was a strict Buddhist and a Siamese nationalist. He intended using this western knowledge to strengthen and modernise Siam when he came to the throne, which he did in 1851. By the 1840s it was obvious that Siamese independence was in danger from the colonial powers: this was shown dramatically by the British Opium Wars with China in 1839–1842. In 1850 the British and Americans sent missions to Bangkok demanding the end of all restrictions on trade, the establishment of a western-style government and immunity for their citizens from Siamese law (extraterritoriality). Rama III's government refused these demands, leaving his successor with a dangerous situation. Rama III reportedly said on his deathbed: "We will have no more wars with Burma and Vietnam. We will have them only with the West."

Mongkut

Mongkut came to the throne as Rama IV in 1851, determined to save Siam from colonial domination by forcing modernisation on his reluctant subjects. But although he was in theory an absolute monarch, his power was limited. Having been a monk for 27 years, he lacked a base among the powerful royal princes, and did not have a modern state apparatus to carry out his wishes. His first attempts at reform, to establish a modern system of administration and to improve the status of debt-slaves and women, were frustrated. Rama IV thus came to welcome western pressure on Siam. This came in 1855 in the form of a mission led by the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir John Bowring, who arrived in Bangkok with demands for immediate changes, backed by the threat of force. The King readily agreed to his demand for a new treaty, which restricted import duties to 3 percent, abolished royal trade monopolies, and granted extraterritoriality to British subjects. Other western powers soon demanded and got similar concessions.

The king soon came to consider that the real threat to Siam came from the French, not the British. The British were interested in commercial advantage, the French in building a colonial empire. They occupied Saigon in 1859, and 1867 established a protectorate over southern Vietnam and eastern Cambodia. Rama IV hoped that the British would defend Siam if he gave them the economic concessions they demanded. In the next reign this would prove to be an illusion, but it is true that the British saw Siam as a useful buffer state between British Burma and French Indochina.

Chulalongkorn

Rama IV died in 1868, and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son Chulalongkorn, who reigned as Rama V and is now known as Rama the Great. Rama V was the first Siamese king to have a full western education, having been taught by an English governess, Anna Leonowens - whose place in Siamese history has been fictionalised as The King and I. At first Rama V's reign was dominated by the conservative regent, Chaophraya Si Suriyawongse, but when the king came of age in 1873 he soon took control. He created a Privy Council and a Council of State, a formal court system and budget office. He announced that slavery would be gradually abolished and debt-bondage restricted.

At first the princes and other conservatives successfully resisted the king's reform agenda, but as the older generation was replaced by younger and western-educated princes, resistance faded. The king could always argue that the only alternative was foreign rule. He found powerful allies in his brother Prince Chakkraphat, whom he made finance minister, and his brother-in-law Prince Devrawongse, foreign minister for 38 years. In 1887 Devrawonge visited Europe to study government systems. On his recommendation the king established Cabinet government, an audit office and an education department. The semi-autonomous status of Chiang Mai was ended and the army was reorganised and modernised.

In 1893 the French authorities in Indochina used a minor border dispute to provoke a crisis. French gunboats appeared at Bangkok, and demanded the cession of Lao territories east of the Mekong. The King appealed to the British, but the British minister told the King to settle on whatever terms he could get, and he had no choice but to comply. Britain's only gesture was an agreement with France guaranteeing the integrity of the rest of Siam. In exchange, Siam had to give up its claim to the Tai-speaking Shan region of north-eastern Burma to the British.

The French, however, continued to pressure Siam, and in 1906–1907 they manufactured another crisis. This time Siam had to concede French control of territory on the west bank of the Mekong opposite Luang Prabang and around Champasak in southern Laos, as well as western Cambodia. The British interceded to prevent more French bullying of Siam, but their price, in 1909 was the acceptance of British sovereignty over of Kedah, Kelantan, Perlis and Terengganu under Anglo-Siamese Treaty of 1909. All of these "lost territories" were on the fringes of the Siamese sphere of influence and had never been securely under their control, but being compelled to abandon all claim to them was a substantial humiliation to both king and country (historian David Wyatt describes Chulalongkorn as "broken in spirit and health" following the 1893 crisis). In the early 20th century these crises were adopted by the increasingly nationalist government as symbols of the need for the country to assert itself against the West and its neighbours.

Meanwhile, reform continued apace transforming an absolute monarchy based on relationships of power into a modern, centralised nation state. The process was increasingly under the control of Rama V's sons, who were all educated in Europe. Railways and telegraph lines united the previously remote and semi-autonomous provinces. The currency was tied to the gold standard and a modern system of taxation replaced the arbitrary exactions and labour service of the past. The biggest problem was the shortage of trained civil servants, and many foreigners had to be employed until new schools could be built and Siamese graduates produced. By 1910, when the King died, Siam had become at least a semi-modern country, and continued to escape colonial rule.

Rama VI

One of Rama V's reforms was to introduce a western-style law of royal succession, so in 1910 he was peacefully succeeded by his son Vajiravudh, who reigned as Rama VI. He had been educated at Sandhurst military academy and at Oxford, and was a thoroughly anglicised Edwardian gentleman. Indeed one of Siam's problems was the widening gap between the westernised royal family and upper aristocracy and the rest of the country. It took another 20 years for western education to extend to the rest of the bureaucracy and the army: a potential source of conflict.

There had been no political reform under Rama V: the king was still an absolute monarch, who acted as his own prime minister and staffed all the agencies of the state with his own relatives. Rama VI, with his British education, knew that the rest of the nation could not be excluded from government for ever, but he was no democrat. His solution was build a mass royalist political and paramilitary movement called Seua Pa ("Wild Tigers") to create a sense of participation without weakening the royal grip on power. He applied his observation of the success of the British monarchy, appearing more in public and instituting more royal ceremonies. But he also carried on his father's modernisation program. Polygamy was abolished, primary education made compulsory, and in 1916 higher education came to Siam with the founding of Chulalongkorn University, which in time became the seedbed of a new Siamese intelligentsia.

In 1917 Siam declared war on Germany, mainly to gain favour with the British and the French. Siam's token participation in World War I gained it a seat at the Versailles Peace Conference, and Foreign Minister Devrawongse used this opportunity to argue for the repeal of the 19th century treaties and the restoration of full Siamese sovereignty. The United States obliged in 1920, while France and Britain delayed until 1925. This victory gained the king some popularity, but it was soon undercut by discontent over other issues, such as his extravagance, which became more noticeable when a sharp postwar recession hit Siam in 1919. There was also the fact that the king had no son; he obviously preferred the company of men to women (a matter which of itself did not much concern Siamese opinion, but which did undermine the stability of the monarchy).

Thus when Rama VI died suddenly in 1925, aged only 44, the monarchy was already in a weakened state. He was succeeded by his younger brother Prajadhipok (Rama VII), who inherited a country which had outgrown the system of personal rule but had no experience of any other system. The state's finances were in chaos, the budget out of control, the army restive and the newest player in Siamese politics, the Bangkok press, increasingly outspoken in its criticism. The new king, who had not expected to inherit the throne, had been trained as an army officer and had little aptitude for government.

The king's attempts at reform were ineffective. He established a Supreme Council of State, but then stacked it with his relatives, thus negating any good impression it might have created. Pressure for political reform mounted from the new class of university educated civil servants, who filled the Bangkok press with their opinions. One of these was a young lawyer called Pridi Phanomyong, soon to become one of the leaders of the reformist movement. There was also pressure from the influential Chinese business community, who wanted financial stability. The return of prosperity in the mid 1920s eased these pressure somewhat, but the onset of the Great Depression in 1930 brought a renewed air of crisis. Keen to maintain its respectability with foreign creditors, Siam maintained the gold standard, thus pricing itself out of its export markets.

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the king made a speech in which he said: "I myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam." This was not well received. Serious political disturbances were threatened in the capital, and in April the king agreed to introduce a constitution under which he would share power with a prime minister. This was not enough for the radical elements in the army, however. On June 24, 1932, while the king was holidaying at the seaside, the Bangkok garrison mutinued and seized power, led by a group of 49 officers known as "the Promoters." Thus ended 150 years of Siamese absolute monarchy.

Notes

- Thongchai Winichakul (1994). Siam Mapped p. 153.