| Revision as of 20:38, 8 August 2012 editJdemarcos (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,047 edits Not certain← Previous edit | Revision as of 16:17, 9 August 2012 edit undoAnatoly Ilych Belousov (talk | contribs)430 edits →New works: Now, no explicit mention of the scholar website, and clearly says where it was passed, in the academic media RAMC, ISHM, SSHM, so no banner is required, for it says what it says. Academic journal references in the section.Next edit → | ||

| (3 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 161: | Line 161: | ||

| === New works === | === New works === | ||

| {{POV-section|date= August 2012}} | |||

| ( , the and the ) | |||

| ⚫ | The ''Biblia Sacra Ex Postremis Doctorum'' has been proved to be a Michel de Villeneuve/Servetus work, on the protocols of Michel de Villeneuve with his printers and editors (Melchior and Gaspard Trechsel) and matching these with anonymous works of the same period of time in data, mention of characters, the locations and use of words, and contract requirements. Applying the same methods, the researcher and scholar on Michael Servetus, González Echeverría, has demonstrated before the ],<ref name="BarcelonaCongress">2011 September 9th, Francisco González Echeverría VI International Meeting for the History of Medicine,(S-11: Biographies in History of Medicine (I)), Barcelona. New Discoveries on the biography of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) & New discoveries on the work of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus)</ref><ref name="KosCongress">1996 “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (I)” and “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (II)” González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts. 35th International Congress on the History of Medicine, 2nd-8th, September, 1996, Kos Island, Greece, communications nº: 6 y 7, p. 4.</ref><ref name="TunisCongress">1998 “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his Dispensarium”(Le livre de travail de Michel Servet pour ses Dioscorides et Dispensarium) and “The Dispensarium or Enquiridion, complementary of the Dioscorides of Michael Servetus” (The Enquiridion, L’oeuvre Le Dispensarium ou Enquiridion complémentaire sur le Dioscorides de Michel Servet) González Echeverría, in: Book of summaries, 36th International Congress on the History of Medicine, Tunis (Livre des Résumés, 36 ème Congrès International d’ Histoire de la médicine, Tunis), 6th-11th September 1998, (two communications), pp. 199 y 210.</ref><ref name="TexasCongress">2000- “Discovery of new editions of Bibles and of two 'lost' grammatical works of Michael Servetus” and “The doctor Michael Servetus was descended from Jews”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Abstracts, 37th International Congress on the History of Medicine, September 10–15, 2000, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A., pp. 22-23.</ref><ref name="GreeceCongress">2005 “Deux nouvelles oeuvres de Michel Servet ou De Villeneuve: L’Andrianne en latin-espagnol et un Lexicon greco-latin”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts, 3rd Meeting of the ISHM, 11–14 September 2005, Patrás, Greece, p. 92.</ref> the Spanish National Society of History of Medicine,<ref name="SantiagoCongress">1998 “The 'Dispensarium' or 'Enquiridion', the complementary work of the Dioscorides, both by Servetus” and “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his 'Dispensarium'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Program of the congress and abstracts of the comunications, XI National Congress on History of Medicine, Santiago de Compostela, University of Santiago de Compostela ,pp. 83-84.</ref><ref name="MalagaCongress">1996 “A Spanish work attributable to Michael Servetus: 'The Dioscorides of Sesma'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Varia Histórico-Médica. Edition coordinated by: Jesús Castellanos Guerrero (coord.), Isabel Jiménez Lucena, María José Ruiz Somavilla y Pilar Gardeta Sabater. Minutes from the X Congress on History of Medicine, February 1986, Málaga. Printed by Imagraf, Málaga,pp. 37-55</ref><ref name="AlbaceteCongress">2004 “The edition of Lyon of the ‘Opera omnia’ by Galen of the printer Jean Frellon (1548-1551) commented by Michael Servetus”, González Echeverría and Ancín Chandía, Teresa. In: Medicine in the presence of the new millennium: a historical perspective. Coordinators: José Martínez Pérez,Isabel Porras Gallo, Pedro Samblás Tilve, Mercedes Del Cura González, Minutes from the XII Congress in History of Medicine, 7–9 February 2002, Albacete. Ed. Of the University of Castilla-La Mancha. Cuenca, pp. 645-657.</ref> and the Royal Academy of Medicine of ]<ref>Acte Conmmemoratiu del cinque cententary de Miguel Servet(1511-2011), 29th November 2011, Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya</ref> that Michael wrote five previously unknown medical works (one of them posthumous), two Biblical works, and four grammatical translation works. Michael Servetus/de Villeneuve, who published almost annually for more than a decade from 1531 to 1542, did not stop publishing for the following 11 years. He did publish, but anonymously, because of the death sentence threatened at the ] in 1538.<ref name="Lovefortruth" /> | ||

| ⚫ | The ''Biblia Sacra Ex Postremis Doctorum'' has been proved to be a Michel de Villeneuve/Servetus work, on the protocols of Michel de Villeneuve with his printers and editors (Melchior and Gaspard Trechsel) and matching these with anonymous works of the same period of time in data, mention of characters, the locations and use of words, and contract requirements. Applying the same methods, the researcher and scholar on Michael Servetus, González Echeverría, has demonstrated before the ],<ref name="BarcelonaCongress">2011 September 9th, Francisco González Echeverría VI International Meeting for the History of Medicine,(S-11: Biographies in History of Medicine (I)), Barcelona. New Discoveries on the biography of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) & New discoveries on the work of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus)</ref><ref name="KosCongress">1996 “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (I)” and “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (II)” González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts. 35th International Congress on the History of Medicine, 2nd-8th, September, 1996, Kos Island, Greece, communications nº: 6 y 7, p. 4.</ref><ref name="TunisCongress">1998 “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his Dispensarium”(Le livre de travail de Michel Servet pour ses Dioscorides et Dispensarium) and “The Dispensarium or Enquiridion, complementary of the Dioscorides of Michael Servetus” (The Enquiridion, L’oeuvre Le Dispensarium ou Enquiridion complémentaire sur le Dioscorides de Michel Servet) González Echeverría, in: Book of summaries, 36th International Congress on the History of Medicine, Tunis (Livre des Résumés, 36 ème Congrès International d’ Histoire de la médicine, Tunis), 6th-11th September 1998, (two communications), pp. 199 y 210.</ref><ref name="TexasCongress">2000- “Discovery of new editions of Bibles and of two 'lost' grammatical works of Michael Servetus” and “The doctor Michael Servetus was descended from Jews”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Abstracts, 37th International Congress on the History of Medicine, September 10–15, 2000, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A., pp. 22-23.</ref><ref name="GreeceCongress">2005 “Deux nouvelles oeuvres de Michel Servet ou De Villeneuve: L’Andrianne en latin-espagnol et un Lexicon greco-latin”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts, 3rd Meeting of the ISHM, 11–14 September 2005, Patrás, Greece, p. 92.</ref> the Spanish National Society of History of Medicine,<ref name="SantiagoCongress">1998 “The 'Dispensarium' or 'Enquiridion', the complementary work of the Dioscorides, both by Servetus” and “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his 'Dispensarium'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Program of the congress and abstracts of the comunications, XI National Congress on History of Medicine, Santiago de Compostela, University of Santiago de Compostela ,pp. 83-84.</ref><ref name="MalagaCongress">1996 “A Spanish work attributable to Michael Servetus: 'The Dioscorides of Sesma'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Varia Histórico-Médica. Edition coordinated by: Jesús Castellanos Guerrero (coord.), Isabel Jiménez Lucena, María José Ruiz Somavilla y Pilar Gardeta Sabater. Minutes from the X Congress on History of Medicine, February 1986, Málaga. Printed by Imagraf, Málaga,pp. 37-55</ref><ref name="AlbaceteCongress">2004 “The edition of Lyon of the ‘Opera omnia’ by Galen of the printer Jean Frellon (1548-1551) commented by Michael Servetus”, González Echeverría and Ancín Chandía, Teresa. In: Medicine in the presence of the new millennium: a historical perspective. Coordinators: José Martínez Pérez,Isabel Porras Gallo, Pedro Samblás Tilve, Mercedes Del Cura González, Minutes from the XII Congress in History of Medicine, 7–9 February 2002, Albacete. Ed. Of the University of Castilla-La Mancha. Cuenca, pp. 645-657.</ref> and the Royal Academy of Medicine of ]<ref>Acte Conmmemoratiu del cinque cententary de Miguel Servet(1511-2011), 29th November 2011, Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya</ref> that Michael wrote five previously unknown medical works (one of them posthumous), two Biblical works, and four grammatical translation works. Michael Servetus/de Villeneuve, who published almost annually for more than a decade from 1531 to 1542, did not stop publishing for the following 11 years. He did publish, but anonymously, because of the death sentence threatened at the ] in 1538.<ref name="Lovefortruth" /> | ||

| González Echeverría found these works through contracts Michel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in ] in 1540. The Company of Booksellers comprised many editors and printers, particularly the Trechsel and Frellon brothers. These works include the ''Opera Omnia'' by ], thought not to exist, though the contracts existed. González Echeverría also found De Villeneuve's Spanish work of translation through the connection with the brothers Trechsel and the brothers Frellon, famous printers in Lyon. It was Jean Frellon himself who affirmed in the judgement of ] against Michael de Villeneuve that “Michel de Villeneuve had translated at his printing work various grammatical treatises from Latin to Spanish and had made a Spanish summary of St ].”<ref>D'Artigny, A.G., Nouveaux mémoires d'histoire, de critique et de littérature, (Paris: 1749), t. II, p. 68. Francisco Javier González Echeverría suggested that D’Artigny (who transcribed the records from Vienne ) mistook “somme” for “Summa”, and thought it referred to the Summa of ]. Thomas Aquinas was never before the XIXth century translated into any vernacular language. It seems rather that it was a summary of the ] in Spanish.</ref> | González Echeverría found these works through contracts Michel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in ] in 1540. The Company of Booksellers comprised many editors and printers, particularly the Trechsel and Frellon brothers. These works include the ''Opera Omnia'' by ], thought not to exist, though the contracts existed. González Echeverría also found De Villeneuve's Spanish work of translation through the connection with the brothers Trechsel and the brothers Frellon, famous printers in Lyon. It was Jean Frellon himself who affirmed in the judgement of ] against Michael de Villeneuve that “Michel de Villeneuve had translated at his printing work various grammatical treatises from Latin to Spanish and had made a Spanish summary of St ].”<ref>D'Artigny, A.G., Nouveaux mémoires d'histoire, de critique et de littérature, (Paris: 1749), t. II, p. 68. Francisco Javier González Echeverría suggested that D’Artigny (who transcribed the records from Vienne ) mistook “somme” for “Summa”, and thought it referred to the Summa of ]. Thomas Aquinas was never before the XIXth century translated into any vernacular language. It seems rather that it was a summary of the ] in Spanish.</ref> | ||

Revision as of 16:17, 9 August 2012

Not to be confused with Servatius (disambiguation).| Michael Servetus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | (1511-09-29)29 September 1511 Villanueva de Sijena, Kingdom of Aragon (in present-day Spain) |

| Died | 27 October 1553(1553-10-27) (aged 42) Geneva, Swiss Confederacy |

| Title | Theologian, Physician, Cartographer, Translator |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Main interests | Theology, Medicine |

| Notable ideas | Nontrinitarian Christology Pulmonary circulation |

Michael Servetus also Miguel Servet or Miguel Serveto or Michel de Villeneuve; (29 September 1511? – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and humanist. He was the first European correctly to describe the function of pulmonary circulation. He was a polymath versed in many sciences: mathematics, astronomy and meteorology, geography, human anatomy, medicine and pharmacology, as well as jurisprudence, translation, poetry and the scholarly study of the Bible in its original languages. He is renowned in the history of several of these fields, particularly medicine and theology. He participated in the Protestant Reformation, and later developed a nontrinitarian Christology. Condemned by Catholics and Protestants alike, he was arrested in Geneva and burnt at the stake as a heretic by order of the Protestant Geneva governing council.

Life

Early life and education

Servetus was probably born on 29 September 1511 in Villanueva de Sijena in Aragon, Spain. Some sources give an earlier date based on Servetus' own occasional claim of having been born in 1509. The ancestors of his father came from the hamlet of Serveto, in the Aragonese Pyrenees. Michael aroused Calvin's suspicions about his Jewish heritage, his maternal line descended from the Zaportas (or Çaportas), a wealthy and socially relevant Jewish converso family from the Barbastro and Monzón areas in Aragon. This was demonstrated by a notarial protocol published in 1999. His father was a notary of Christian ancestors from the lower nobility (infanzón), who worked at the nearby Monastery of Santa Maria de Sigena. Servetus had two brothers, one was a Catholic priest, Juan, another was a notary, Pedro.

Michael was gifted in languages and could have studied Latin, Greek and Hebrew under the instruction of Dominican friars.. At the age of fifteen, Michael Servetus entered the service of a Franciscan friar by the name of Juan de Quintana. He read the entire Bible in its original languages from the manuscripts available at that time. Michael Servetus later attended the University of Toulouse in 1526 where he studied law. Michael affirmed he had access to forbidden religious books, some of them maybe Protestant, while he was studying in this city.

Career

Servetus's wide readings informed his thinking. In 1528, Michael traveled through Germany and Italy with Juan de Quintana in the imperial retinue. Quintana became Charles V's confessor in 1530. Michael started to contact Protestants, and called himself Servetus. In October 1530 he visited Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, staying there for about ten months, and probably supporting himself as a proofreader for a local printer. By this time he was already spreading his theological beliefs. In May 1531 he met Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Fabricius Capito in Strasbourg.

Two months later, in July 1531, Michael published De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). The next year he published the work Dialogorum de Trinitate (Dialogues on the Trinity) and the supplementary work De Iustitia Regni Christi (On the Justice of Christ's Reign) in the same volume. After the persecution of the Inquisition, Michael assumed the name "Michel de Villeneune" while he was staying in France. He studied at the Collège de Calvi in Paris in 1533. Michael also published the first French edition of Ptolemy's Geography. Servetus dedicated his first edition of Ptolemy and his edition of the Bible to his patron Hugues de la Porte. While in Lyon, Symphorien Champier, a medical humanist, had been Michael's patron. Servetus wrote a pharmacological treatise in defense of Champier against Leonhart Fuchs In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia (Apology against Leonard Fuchs). Working also as a proofreader, he published several more books which dealt with medicine and pharmacology, such as his Syruporum universia ratio (Complete Explanation of the Syrups), which became a very famous work.

After an interval, Servetus returned to Paris to study medicine in 1536. In Paris, his teachers included Sylvius, Fernel and Johann Winter von Andernach, who hailed him with Andrea Vesalius as his most able assistant in dissections. These years he wrote his Manuscript of the Complutense, an unpublished compendium of his medical ideas. Servetus taught mathematics and astrology while he studied medicine. He predicted an occultation of Mars by the Moon, and this joined to his teaching generated much envy among the medicine teachers. His teaching classes were suspended by the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Jean Tagault, and Michael wrote his Apologetic Discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in Favour of Astrology and against a Certain Physician against him. Tagault later argued for the death penalty in the judgement of the University of Paris against Michel de Villeneuve. He was accused of teaching De Divinatione by Cicero. Finally, the sentence was reduced to the withdrawal of this edition. This persuaded Michael to keep his name off the cover of any new work he would publish from 1538. After 1542 he published only anonymously. As a result of the risks and difficulties of studying medicine at Paris, Michael decided to go to Montpellier to finish his medical studies. There he became a Doctor of Medicine in 1539. After that he lived at Charlieu. Another physician, jealous, ambushed and tried to kill Servetus, but Michael defended himself and injured one of the attackers in this swordfight. He was in prison for several days because of this incident. Michael published his Biblical work Pictures from the Stories of the Old Testament, with Stelsius, an associate of the printer Jean Frellon II, a friend of Michael.

Working at Vienne

After his studies in medicine, Servetus started a medical practice. He became personal physician to Pierre Palmier, Archbishop of Vienne, and was also physician to Guy de Maugiron, the lieutenant governor of Dauphiné. Thanks to a common acquaintance, the printer Jean Frellon, Michael and Calvin began to correspond. Calvin uses the pseudonym "Charles d'Espeville." During these years, with the Trechsel brothers, printers, Servetus published three editions of the Bible: Holy Bible according to the Translation of Santes Pagnino, the Biblia sacra ex postremis doctorum, and the Holy Bible with Commentaries. Also during these years Michel de Villeneuve, with his friend the printer Jean Frellon, published many medical works: his Dioscorides-Materia Medica, his pharmacopeia Dispensarium or Enquiridion, and his Opera Omnia of Galen. He also wrote his Manuscript of Paris, with the first (unpublished) European description of the pulmonary circulation, and again published, thanks to Frellon, a Biblical work of Spanish poetry, Portraits or Figures from the Stories of the Old Testament, and three Spanish Latin grammatical treatises for children: Children's Book of Notes on the Elegance and Variety of the Latin Language, Distichs of Cato, and A Little Work on the Use of the Eight Parts of Speech. Michael also became a French citizen by the Royal Process (1548–1549) of French Naturalization, issued by Henri II of France.

In 1553 Michael Servetus published yet another religious work with further anti-trinitarian views. It was entitled Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity), a work that sharply rejected the idea of predestination as the idea that God condemned souls to Hell regardless of worth or merit. God, insisted Servetus, condemns no one who does not condemn himself through thought, word or deed. This work also includes the first published description of the pulmonary circulation.

To Calvin, who had written his summary of Christian doctrine Institutio Christianae Religionis (Institutes of the Christian Religion), Servetus' latest book was an attack on his personally held theories regarding Christian belief, theories that he put forth as "established Christian doctrine". Calvin sent a copy of his own book as his reply. Servetus promptly returned it, thoroughly annotated with critical observations. Calvin wrote to Servetus, "I neither hate you nor despise you; nor do I wish to persecute you; but I would be as hard as iron when I behold you insulting sound doctrine with so great audacity." In time their correspondence grew more heated until Calvin ended it. Servetus sent Calvin several more letters, to which Calvin took offense. Thus, Calvin's antagonism against Servetus seems to have been based not simply on his views but also on Servetus's tone, which he considered inappropriate. Calvin revealed the intentions of his offended pride when writing to his friend William Farel on 13 February 1546:

Servetus has just sent me a long volume of his ravings. If I consent he will come here, but I will not give my word; for if he comes here, if my authority is worth anything, I will never permit him to depart alive (Template:Lang-la).

Imprisonment and execution

On 16 February 1553, Michael Servetus while in Vienne, was denounced as a heretic by Guillaume de Trie, a rich merchant who had taken refuge in Geneva, and a very good friend of Calvin, in a letter sent to a cousin, Antoine Arneys, who was living in Lyon. On behalf of the French inquisitor Matthieu Ory, Michel Serveus as well as Balthasard Arnollet, the printer of Christianismi Restitutio, were questioned, but they denied all charges and were released for lack of evidence. Arneys was asked by Ory to write back to De Trie, demanding proof. On 26 March 1553, the letters sent by Michel to Calvin and some manuscript pages of Christianismi Restitutio were forwarded to Lyon by Trie. On 4 April 1553 Michael de Villanueva was arrested by Roman Catholic authorities, and imprisoned in Vienne. Servetus escaped from prison three days later. On 17 June, Michel de Villeneuve was convicted of heresy, "thanks to the 17 letters sent by Jehan Calvin, preacher in Geneva" and sentenced to be burned with his books. An effigy and his books were burned in his absence.

Meaning to flee to Italy, Servetus inexplicably stopped in Geneva, where Calvin and his Reformers had denounced him. On 13 August, he attended a sermon by Calvin at Geneva. He was arrested after the service and again imprisoned. All his property was confiscated. Servetus claimed during this judgement he was arrested at an inn at Geneva. French Inquisitors asked that Servetus be extradited to them for execution. Calvin wanted to show himself as firm in defense of Christian orthodoxy as his usual opponents. "He was forced to push the condemnation of Servetus with all the means at his command." Calvin's delicate health meant he did not personally appear against Servetus. Nicholas de la Fontaine played the more active role in Servetus's prosecution and the listing of points that condemned him.

At his trial, Servetus was condemned on two counts, for spreading and preaching Nontrinitarianism and anti-paedobaptism (anti-infant baptism). Of paedobaptism Servetus had said, "It is an invention of the devil, an infernal falsity for the destruction of all Christianity." In the case the procureur général (chief public prosecutor) added some curious sounding accusations in the form of inquiries—the most odd sounding perhaps being, "whether he has married, and if he answers that he has not, he shall be asked why, in consideration of his age, he could refrain so long from marriage." To this oblique imputation of unchastity (or perhaps homosexuality), Servetus replied that rupture (inguinal hernia) had long since made him incapable of that particular sin. More offensive to modern ears might be the question "whether he did not know that his doctrine was pernicious, considering that he favours Jews and Turks, by making excuses for them, and if he has not studied the Koran in order to disprove and controvert the doctrine and religion that the Christian churches hold, together with other profane books, from which people ought to abstain in matters of religion, according to the doctrine of St. Paul."

Calvin believed Servetus deserving of death on account of what he termed as his "execrable blasphemies". Calvin expressed these sentiments in a letter to Farel, written about a week after Servetus’ arrest, in which he also mentioned an exchange with Servetus. Calvin wrote:

...after he had been recognized, I thought he should be detained. My friend Nicolas summoned him on a capital charge, offering himself as a security according to the lex talionis. On the following day he adduced against him forty written charges. He at first sought to evade them. Accordingly we were summoned. He impudently reviled me, just as if he regarded me as obnoxious to him. I answered him as he deserved... of the man’s effrontery I will say nothing; but such was his madness that he did not hesitate to say that devils possessed divinity; yea, that many gods were in individual devils, inasmuch as a deity had been substantially communicated to those equally with wood and stone. I hope that sentence of death will at least be passed on him; but I desired that the severity of the punishment be mitigated.

As Servetus was not a citizen of Geneva, and legally could at worst be banished, the government, in an attempt to find some plausible excuse to disregard this legal reality, had consulted with other Swiss Reformed cantons (Zürich, Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen.) They universally favored his condemnation and suppression of his doctrine, but without saying how that should be accomplished. Martin Luther had condemned his writing in strong terms. Servetus and Philip Melanchthon had strongly hostile views of each other. The party called the "Libertines", who were generally opposed to anything and everything John Calvin supported, were in this case strongly in favor of the execution of Servetus at the stake (while Calvin urged that he be beheaded instead). In fact, the council that condemned Servetus was presided over by Perrin (a Libertine) who ultimately on 24 October sentenced Servetus to death by burning for denying the Trinity and infant baptism. When Calvin requested that Servetus be executed by decapitation as a traitor rather than by fire as a heretic, Farel, in a letter of 8 September, chided him for undue lenience. The Geneva Council refused his request. On 27 October 1553 Servetus was burned at the stake just outside Geneva with what was believed to be the last copy of his book chained to his leg. Historians record his last words as: "Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me."

Calvin agreed that those whom the ruling religious authorities determined to be heretics should be punished:

Whoever shall maintain that wrong is done to heretics and blasphemers in punishing them makes himself an accomplice in their crime and guilty as they are. There is no question here of man's authority; it is God who speaks, and clear it is what law he will have kept in the church, even to the end of the world. Wherefore does he demand of us a so extreme severity, if not to show us that due honor is not paid him, so long as we set not his service above every human consideration, so that we spare not kin, nor blood of any, and forget all humanity when the matter is to combat for His glory.

Aftermath

Jean Frellon never printed again after the immolation of his friend. He was one of the four printers-editors (with Arnoullet, Rovillium, and Vincent) of the "Lyon Printers' Tribute to Michel de Villeneuve" edition of a Dioscorides-Materia Medica, in honor of their murdered friend.

Sebastian Castellio and countless others denounced this execution and became harsh critics of Calvin because of the whole affair.

Some other anti-trinitarian thinkers began to be more cautious in expressing their views: Martin Cellarius, Lelio Sozzini and others either ceased writing or wrote only in private. The fact that Servetus was dead meant that his writings could be distributed more liberally, though others such as Giorgio Biandrata developed them in their own names.

The writings of Servetus had some influence on the beginnings of the Unitarian movement in Poland and Transylvania. Piotr z Goniądza's advocacy of Servetus' views led to the separation of the Polish brethren from the Calvinist Reformed Church in Poland, and laid the foundations for the Socinian movement which fostered the early Unitarians in England like John Biddle.

Theology

In his first two books (De trinitatis erroribus, and Dialogues on the Trinity plus the supplementary De Iustitia Regni Christi) Servetus rejected the classical conception of the Trinity, stating that it was not based on the Bible. He argued that it arose from teachings of (Greek) philosophers, and he advocated a return to the simplicity of the Gospels and the teachings of the early Church Fathers that he believed pre-dated the development of Nicene trinitarianism. Servetus hoped that the dismissal of the trinitarian dogma would make Christianity more appealing to believers in Judaism and Islam, which had preserved the unity of God in their teachings. According to Servetus, trinitarians had turned Christianity into a form of "tritheism", or belief in three gods. Servetus affirmed that the divine Logos, the manifestation of God and not a separate divine Person, was incarnated in a human being, Jesus, when God's spirit came into the womb of the Virgin Mary. Only from the moment of conception was the Son actually generated. Therefore the Son was not eternal, but only the Logos from which He was formed. For this reason, Servetus always rejected calling Christ the "eternal Son of God" but rather called him "the Son of the eternal God." In describing Servetus' view of the Logos, Andrew Dibb explained: "In 'Genesis' God reveals himself as the creator. In 'John' he reveals that he created by means of the Word, or Logos. Finally, also in 'John', he shows that this Logos became flesh and 'dwelt among us'. Creation took place by the spoken word, for God said "Let there be ..." The spoken word of Genesis, the Logos of John, and the Christ, are all one and the same."

Unitarian scholar Earl Morse Wilbur states, "Servetus' Errors of the Trinity is hardly heretical in intent, rather is suffused with passionate earnestness, warm piety, an ardent reverence for Scripture, and a love for Christ so mystical and overpowering that can hardly find words to express it...Servetus asserted that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were dispositions of God, and not separate and distinct beings. Wilbur promotes the idea that Servetus was a modalist.

Servetus states his view clearly in the preamble to Restoration of Christianity (1553): "There is nothing greater, reader, than to recognize that God has been manifested as substance, and that His divine nature has been truly communicated. We shall clearly apprehend the manifestation of God through the Word and his communication through the Spirit, both of them substantially in Christ alone." This theology, though original in some respects, has often been compared to Adoptionism, Arianism, and Sabellianism, all of which Trinitarian scholars rejected as heresies in their attempts to defend their belief that God exists eternally in three separate persons. Nevertheless, Servetus rejected these theologies in his books: Adoptionism, because it denied Jesus's divinity; Arianism, because it multiplied the hypostases and established a rank; and Sabellianism, because, at first glance, it seemingly confused the Father with the Son.

The incomprehensible God is known through Christ, by faith, rather than by philosophical speculations. He manifests God to us, being the expression of His very being, and through him alone, God can be known. The scriptures reveal Him to those who have faith; and thus we come to know the Holy Spirit as the Divine impulse within us.

Under severe pressure from Catholics and Protestants alike, Servetus clarified this explanation in his second book, Dialogues (1532), to show the Logos coterminous with Christ. He was nevertheless accused of heresy because of his insistence on denying the dogma of the Trinity and the individuality of three divine Persons in one God.

Legacy and relevance

Theological influence

Because of his rejection of the Trinity and eventual execution by burning for heresy, Unitarians often regard Servetus as the first (modern) Unitarian martyr—though he was a Unitarian in neither the 17th-century sense of the term nor the contemporary sense. Other non-trinitarian groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, and Oneness Pentecostalism, also claim Servetus as a spiritual ancestor. Oneness Pentecostalism particularly identifies with Servetus' teaching on the divinity of Jesus Christ and his insistence on the oneness of God, rather than a Trinity of three distinct persons: "And because His Spirit was wholly God He is called God, just as from His flesh He is called man."

Swedenborg wrote a systematic theology that had many similarities to the theology of Servetus.

More recently Servetus' name has been given prominence by the originally anonymous author "Servetus the Evangelical".

Freedom of conscience

In recent years Michael Servetus has also been credited with being one of the modern forerunners of freedom of religion and freedom of conscience in the Western world. A renowned Spanish scholar on Servetus' work, Ángel Alcalá, identified the radical search for truth and the right for freedom of conscience as Servetus' main legacies, rather than his theology. The Polish-American scholar, Marian Hillar, has studied the evolution of freedom of conscience, from Servetus and the Polish Socinians, to John Locke and to Thomas Jefferson and the American Declaration of Independence. According to Hillar: "Historically speaking, Servetus died so that freedom of conscience could become a civil right in modern society."

Scientific legacy

Servetus was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation, although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. One was that the description appeared in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. However, the sections in which he refers to anatomy and medicines demonstrate an amazing understanding of the body and treatments. Most copies of the book were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities. Three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades.

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with all his published works (two of his manuscripts were never published), the five lectures of his Complete Explanation of the Syrups, the 277 marginalia and 20 notes of his two Discorides-Materia Medica, his prologues and corrections in his edition of the Opera Omnia of Galen, his study on syphilis in his Apology against Leonhart Fuchs and specially with the 224 new recipes of his pharmacopeia Dispensarium, which became the main reference pharmacopeia for physicians and galenists for decades.

Honors

Geneva

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honor. The group was led by a French Senator, Auguste Dide, an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clothilde Roch, to do a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. However by then, supporters of Calvin in Geneva, having heard about the project, had already erected a simple stele in memory of Servetus in 1903, the main text of which served more as an apologetic for Calvin:

Duteous and grateful followers of Calvin our great Reformer, yet condemning an error which was that of his age, and strongly attached to liberty of conscience according to the true principles of his Reformation and gospel, we have erected this expiatory monument. Oct. 27, 1903

About the same time, a short street close by the stele was named after him.

The city council then rejected the request of the committee to erect the completed statue, on the grounds that there was already a monument to Servetus. The committee then offered the statue to the French town of Annemasse, which in 1908 placed it in front of the city hall, with the following inscriptions:

“The arrest of Servetus in Geneva, where he did neither publish nor dogmatize, hence he was not subject to its laws, has to be considered as a barbaric act and an insult to the Right of Nations.” Voltaire

I beg you, shorten please these deliberations. It is clear that Calvin for his pleasure wishes to make me rot in this prison. The lice eat me alive. My clothes are torn and I have nothing for a change, nor shirt, only a worn out vest.” Servetus, 1553

In 1942, the Vichy Government took down the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience, and melted it. In 1960, having found the original molds, Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.

Finally, on the 3rd of October 2011, Geneva erected a copy of the statue which it had rejected over 100 years before. It was cast in Aragon from the molds of Clothilde Roch's original statue. Rémy Pagani, former mayor of Geneva, inaugurated the statue. He previously had described Servetus as "the dissident of dissidents."Tribune de Geneve Representatives from the Roman Catholic Church in Geneva and the Director of Geneva's International Museum of the Reformation attended the ceremony. A Geneva newspaper noted the absence of officials from the National Protestant Church of Geneva, the church of John Calvin.

Elsewhere

In 1984, a Zaragoza public hospital changed its name from José Antonio to Miguel Servet. It is now a university hospital.

Most Spanish cities also include at least a street, square or park named after Servetus.

Works

Only the dates of the first editions are included.

- 1531 “On the Errors of the Trinity. De Trinitatis Erroribus” (Haguenau, Setzer). Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city in which it was printed. Signed as Michael Serveto alias Revés, from Aragon, Spanish.

- 1532 “Dialogues on the Trinity. Dialogorum de Trinitaty” (Haguenau, Setzer). Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city which it was printed. Signed as Michael Serveto alias Revés, from Aragon, Spanish.

- 1535 “Geography of Claudius Ptolemy. Claudii Ptolemaeii Alexandrinii Geographicae.” Lyon, Trechsel. Signed as Michel De Villeneuve. Michael dedicated this work to Hugues de la Porte. The second edition was dedicated to Pierre Palmier. Michel de Villeneuve states that the basis of his edition comes from the work of Bilibald Pirkheimer, who translated this work from Greek to Latin, but Michel also affirms that he also compared it to the primitive Greek texts. The expert in Servetus, Henri Tollin (1833–1902) considered Michel de Villeneuve to be “The Father of comparative geography” due to the extension of his notes and commentaries.

- 1536 “The Apology against Leonard Fuchs. In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia.“ Lyon, printed by Gilles Hugetan, with Parisian prologue. Signed as Michel de Villeneuve. The physician Leonhart Fuchs and a friend of Michel de Villeneuve, Symphorien Champier, got involved in an argument via written works, on their different Lutheran and Catholic beliefs. Michel de Villeneuve defends his friend in the first parts of the work. In the second part he talks of a medical plant and its properties. In the last part he writes on different topics, such as the defense of a pupil attacked by a teacher, and the origin of syphilis.

- 1537 “Complete Explanation of the Syrups. Syruporum universia ratio”. Paris, edited by Simon de Colines. Signed as Michael de Villeneuve. This work consists of a prologue "The Use of Syrups", and 5 chapters: I “What the concoction is and why it is unique and not multiple”, II "What the things that must be known are", III "That the concoction is always..", IV "Exposition of the aphorisms of Hippocrates" and V "On the composition of syrups". Michel de Villeneuve refers to experiences of using the treatments, and to pharmaceutical treatises and terms more deeply described in his later pharmacopeia Enquiridion or Dispensarium. Michel mentions two of his teachers, Sylvius and Andernach, but above all, Galen. This work had a strong impact in those times.

- 1538 “Apologetic discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in favour of Astrology and against a certain physician. Michaelis Villanovani in quedam medicum apologetica disceptatio pro Astrologia.” Michel denounces Jean Tagault, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine of Paris, for attacking astrology, while many great thinkers and physicians praised it. He lists reasonings of Plato, Aristotle, Hippocrates and Galen, how the stars are related to some aspects of a patient's health, and how a good phyician can predict effects by them: the effect of the moon and sun on the sea, the winds and rains, the period of women, the speed of the decomposition of the corpses of beasts, etc. De Villeneuve talks of how astrology is good, for it generates a thirst of philosophy that elevates the thought of man. The first point of Tagault is the inconsistency of astrology, for it leads to different predictions, so it is not science. Michael de Villanueva counters that different judgements under the same law do not mean that the laws are a fraud. He explains there are several medical diagnostics, under the same medical doctrine: "All science is a conjecture, if it would not be so, we would be gods. Let's not condemn science." The second argument that Tagault had brought is that astrology, in order to give a round prediction, required the sky to be observed from different places the same way, so it requires the sky to be static, so astrology requires things not to be as they are. Again Michael de Villanueva turns this point against Tagault, explaining how this same reasoning can be used for attacking medicine. About the idea that an observation requires all observations to be the same, and for the sky to be static, Michael denounces dean Tagault's ignorance of mathematics, though he was supposed to be educated in it.

- 1542 “Holy Bible according to the translation of Santes Pagnini. Biblia sacra ex Santes Pagnini tralation, hebraist.” Lyon, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. The name Michel de Villeneuve appears in the prologue, the last time this name would appear in any of his works.

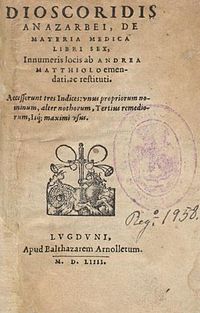

- 1542 "Biblia sacra ex postremis doctorum". Vienne in Dauphiné, edited by Delaporte and printed by Trechsel. Anonymous. Generally attributed to Michael Servetus.

- 1545 "Sacred Bible with commentaries. Biblia Sacra cum Glossis." Lyon, printed by Trechsel and Vincent. Called "Ghost Bible" by scholars who denied its existence. There is an anonymous work from this year that was edited in accordance with the contract that Miguel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in 1540. The work consists of 7 volumes (6 volumes and an index) illustrated by Hans Holbein. This research was carried out by the scholar Julien Baudrier in the sixties. Recently the scholar Francisco Javier González Echeverría has graphically proved the existence of this work to the International Society for the History of Medicine from a copy of the Bible he located in the archives of the city council of Tudela of Navarre. Anonymous.

- “Manuscript of Paris”, (no date). This document was believed to be a draft of the Christianismi Restitutio. Now the authorship of Michel de Villeneuve is confirmed. This is due to the fact of Michel de Villeneuve's demonstrated authorship of the "Manuscript of the Complutense University of Madrid" by González Echeverría before the ISHM, and his subsequent graphological study that revealed that both manuscripts were written by the same hand. It also contains several commentaries in Hebrew

- 1553 "The Restoration of Christianity. Cristianismi Restitutio". Vienne, printed by Baltasar Arnoullet. Without imprint mark or mark of printer, nor the city in which it was printed. Signed as M.S.V. at the colophon though "Servetus" name is mentioned inside, in a fictional dialog. Michael uses Hebrew on his cover. In passage V, Michael recounts his discovery of the pulmonary circulation. His discovery was based on the color of the blood, the size and location of the different ventricles, and the fact that the pulmonary vein was extremely large, which suggested that it performed intensive and transcendent exchange. However Michael does not talk just about cardiology. In the same passage, from page 169 to 178, he also talks of the brain, the cerebellum, the meninges, the nerves, the eye, the tympanum, the rete mirabile, etc., demonstrating a great knowledge of anatomy. In some other sections of this work he also talks of medical products.

New works

( ISHM, the SSHM and the RAMC )

The Biblia Sacra Ex Postremis Doctorum has been proved to be a Michel de Villeneuve/Servetus work, on the protocols of Michel de Villeneuve with his printers and editors (Melchior and Gaspard Trechsel) and matching these with anonymous works of the same period of time in data, mention of characters, the locations and use of words, and contract requirements. Applying the same methods, the researcher and scholar on Michael Servetus, González Echeverría, has demonstrated before the International Society for the History of Medicine, the Spanish National Society of History of Medicine, and the Royal Academy of Medicine of Catalonia that Michael wrote five previously unknown medical works (one of them posthumous), two Biblical works, and four grammatical translation works. Michael Servetus/de Villeneuve, who published almost annually for more than a decade from 1531 to 1542, did not stop publishing for the following 11 years. He did publish, but anonymously, because of the death sentence threatened at the University of Paris in 1538.

González Echeverría found these works through contracts Michel de Villeneuve made with the Company of Booksellers in Lyon in 1540. The Company of Booksellers comprised many editors and printers, particularly the Trechsel and Frellon brothers. These works include the Opera Omnia by Galen, thought not to exist, though the contracts existed. González Echeverría also found De Villeneuve's Spanish work of translation through the connection with the brothers Trechsel and the brothers Frellon, famous printers in Lyon. It was Jean Frellon himself who affirmed in the judgement of Vienne against Michael de Villeneuve that “Michel de Villeneuve had translated at his printing work various grammatical treatises from Latin to Spanish and had made a Spanish summary of St Thomas Aquinas.”

Medical works

- (c.1538) "Manuscript of the Complutense", Paris. On a Dioscorides-Materia Medica of Jean Ruel of 1537 printed by Simon de Colines. González Echeverría ordered an expert graphological comparison of the manuscript with the Manuscript of Paris, hand-written by Servetus. It was carried out by paleographers of Sevilla who concluded that the hundreds of hand-written notes were written in the same hand as the Manuscript of Paris, a first draft of the Christianismi Restitutio. For instance Michael de Villanueva uses the same term used in his Complete explanation of the syrups, the concept of concoction, and he talks of De Divinatione by Cicero, one of the works he was accused of teaching in Paris. the concept of concoction.

- 1543 Materia Médica Dioscorides 1st edition Lyon, Frellon. Medical comments and notes on Vienne, Montpellier and the Doctor Rondelet, based on a Jean Ruel's Materia Medica. Various subsequent editions.

- 1543 The pharmacopeia Dispensarium or Enquiridion, Lyon, Frellon. Complementary to the previous Dioscorides-Materia of the same year, with 224 original recipes and others by Lespleigney and Chappuis. This work had a great impact. Various subsequent editions.

- 1548—1551 Galen Opera Omnia of Galenus, Lyon, Jean Frellon. Five volumes altogether (four volumes and an index). With original commentaries and interest about blood circulation and breathing, corrections against established doctors such as Vesalius, Caius, Janus Cornarius, Sylvius, Johann Winter von Andernachl, but specially his prologues. It is not just that Michel de Villeneuve admired Galen, but that he was the best Galenist known, according to his teachers. Copy checked at the University of Salamanca, section of old books.

- 1554 Materia Medica Dioscorides of Mattioli and Servetus. Designated by González Echeverría "Lyon Printers' Tribute to Michel de Villeneuve", edited by Jean Frellon, Rovillium, Antoine Vincent and Balthasard Arnoullet, and also printed by Arnoullet. Only edition after the immolation of Michel de Villeneuve, as a tribute to him from his colleagues and friends. Contains commentaries by both Mattioli and Michel de Villeneuve. Mattioli's commentaries are signed, Michel de Villeneuve's are not. His commentaries match perfectly with those found in the Materia Medica Dioscorides of 1543, which was based on Jean Ruel's Materia Medica ed. This weird book has 4 different covers, in different copies, within the same edition, one per each editor and friend of Michael.

Professor John M. Riddle, one of the foremosts experts on Dioscorides, from North Carolina State University, described both Dioscorides works from 1543 and 1554 as anonymous. After examining the work of González Echeverría, Riddle has accepted the authorship of Michael Servetus of the two Dioscorides.

Works of Spanish translation

Ilustrated Biblical works

- 1540 Las ymagines de las historias del Viejo Testamento. The images of the stories of the Old Testament. Antwerp, printed by J. Stelsius. Spanish translation from Latin with 92 illustrations by Hans Holbein. Also from the Trechsel editors and printers. There is a previous Frellon Latin edition which contains a prologue signed by him. It was also printed by Trechsel. The translation features the same choice of Spanish terms and Gallicisms found in later De Villeneuve/Servetus' grammatical treatises.

- 1543 Retratos o tablas de la historia del Viejo Testamento. Portraits or printing boards from the story of the Old Testament. Lyon, 2nd edition of 1549. Novenas and 94 quintillas (a kind of Spanish poem) with 94 illustrations by Hans Holbein the younger. ( The “Spanish summary” of the contract with Jean Frellon who mentions it in the Judgement of Vienne) with native words of Navarre and Aragon (Aragonesisms and Navarrisms) from the river Ebro valley area.

Four grammatical non-illustrated works

(Contracts with Frellon for the translation of Spanish-Latin works with many resemblances to the chosen Spanish terminology on the translation. Except in the case of La Andriana they may be aimed at teen-aged readers.)

- 1543 Disticha de moribus nomine Catonis. (Moral Distichs of Cato). Translation of the work of Mathurin Cordier, Lyon, Frellon.

- 1549 Commentarius puerorum de Latinae Linguae Elegantia. Children's book of notes on the elegance and variety of the Latin language. Leuven, Sasseno/widow of Byrckmann. Translation of the work of Mathurin Cordier. In 1551 edition at Lyon, by Frellon.

- (Very possible but not certain authorship of Michael de Villeneuve/Servetus)

1549 Andria. La Andriana. (Louvain, Sasseno/widow of Byrckmann). Translation of the previous work of Charles Estienne. It is a work that appears at the same time as the previous one. Last known edition to date. It uses terminology similar to the previous mentioned work. There is an editorial relationship for spreading Spanish works between Byrckmann and Frellon. González Echeverría affirms: "Unfortunately, since there is not a previous nor subsequent edition by Frellon to date, very possibly it is a work by De Villeneuve/Servetus but we can not be sure of it."

- 1549 De octo orationis partium constructione libellus. A Little Work on the Use of the Eight Parts of Speech. Translation of the prior work of Junien Ranvier. Lyon, Jean Frellon. This work has some exact paragraphs in common with the previous work of De Villeneuve of 1543, Moral distichs of Cato.

In literature

- Austrian author Stefan Zweig features Servetus in Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt.

- Canadian dramatist Robert Lalonde wrote Vesalius and Servetus, a 2008 play on Servetus.

- Stefan Zweig: Castellio gegen Calvin oder Ein Gewissen gegen die Gewalt Reichner, Wien u. a. 1936

- Roland Herbert Bainton: Michael Servet. 1511–1553. Mohn, Gütersloh 1960

- Rosemarie Schuder: Serveto vor Pilatus. Rütten & Loening, Berlin 1982

- Antonio Orejudo: Feuertäufer. Knaus, München 2005, ISBN 3-8135-0266-X (Roman, spanischer Originaltitel: Reconstrucción.)

- Vincent Schmidt: Michel Servet. Du bûcher à la liberté de conscience, Les Éditions de Paris, Collection Protestante, Paris 2009 ISBN 978-2-84621-118-5

- Albert J. Welti: Servet in Genf. Genf, 1931

- Wilhelm Knappich: Geschichte der Astrologie. Veröffentlicht von Vittorio Klostermann, 1998, ISBN 3-465-02984-4, ISBN 978-3-465-02984-7

- Friedrich Trechsel: Michael Servet und seine Vorgänger. Nach Quellen und Urkunden geschichtlich Dargestellt. Universitätsbuchhandlung Karl Winter, Heidelberg 1839 (Reprint durch: Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-142-32980-8)

- Hans-Jürgen Goertz: Religiöse Bewegungen in der Frühen Neuzeit Oldenbourg, München 1992, ISBN 3-486-55759-9

- Henri Tollin: Die Entdeckung des Blutkreislaufs durch Michael Servet, 1511-1553, Nabu Public Domain Reprints

- Henri Tollin: Charakterbild Michael Servet´s, Nabu Public Domain Reprints

- Henri Tollin: Das Lehrsystem Michael Servet´s Volume 1, Nabu Public Domain Reprints

- Henri Tollin: Das Lehrsystem Michael Servet´s Volume 2, Nabu Public Domain Reprints

- Henri Tollin:Michaelis Villanovani (Serveti) in quendam medicum apologetica disceptatio pro astrologia : Nach dem einzig vorhandenen echten Pariser Exemplare, mit einer Einleitung und Anmerkungen. Mecklenburg -1880

See also

Notes

- See a discussion on the date in Angel Alcalá's introduction to the first Spanish translation of Christianismi Restitutio (La restitución del cristianismo, Fundación Universitaria Española, Madrid, 1980, p. 16, note 7.

- Drummond, William H. (1848). The Life of Michael Servetus: The Spanish Physician, Who, for the Alleged Crime of Heresy, was Entrapped, Imprisoned, and Burned, by John Calvin the Reformer, in the City of Geneva, October 27, 1553. London, England: John Chapman. p. 2.

- Ernestro Fernández-Xesta, "Los Zaporta de Barbastro", in Emblemata: Revista aragonesa de emblemática, Vol. #8, 2002, pp. 103-150.

- http://ifc.dpz.es/recursos/publicaciones/28/98/03nicolas.pdf

- Gonzalez Echeverría,“ Andrés Laguna and Michael Servetus: two converted humanist doctors of the XVI century” in: Andrés Laguna International Congress. Humanism, Science and Politics in the Renaissance Europe, García Hourcade y Moreno Yuste, coord., Junta de Castilla y León, Valladolid,1999 pp. 377-389

- González Echeverría “ Michael Servetus belonged to the famous converted Jewish family The Zaporta”, Pliegos de Bibliofilia, nº 7, Madrid pp. 33-42. 1999

- González Echeverría“ On the Jewish heritage of Michael Servetus” Raíces. Jewish Magazine of Culture, Madrid, nº 40, pp. 67-69. 1999

- See J. Barón, Miguel Servet: Su Vida y Su Obra, Espasa-Calpe, Madrid, 1989, pp. 37-39.

- ^ Drummond,p3.

- Wright, Richard (1806). An Apology for Dr. Michael Servetus: Including an Account of His Life, Persecution, Writings and Opinions. London: F. B. Wright. p. 91.

- D'artigny, Judgement of Vienne Isère

- Krendal, Eric. 2011 Ongelmat Michael yliopistossa Pariisissa historioitsija painoksia Medicine, p 34-38

- D'artigny- Judgement at Vienne Isère.

- Downton, An Examination of the Nature of Authority, Chapter 3.

- Will Durant The Story of Civilization: The Reformation Chapter XXI, page 481

- Durant, Story of Civilization, 2

- Bainton, Hunted Heretic, p. 103.

- Hunted Heretic, p. 164.

- ^ The Heretics, p. 326.

- Hanover History

- Hunted Heretic, p. 141.

- Reyburn, Hugh Young (1914). John Calvin: His Life, Letters, and Work. New York: Hodder and Stoughton. p. 175.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Owen, Robert Dale (1872). The debatable Land Between this World and the Next. New York: G.W. Carleton & Co. p. 69, notes.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Calvin to William Farel, August 20, 1553, Bonnet, Jules (1820–1892) Letters of John Calvin, Carlisle, Penn: Banner of Truth Trust, 1980, pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-85151-323-9.

- Schaff, Philip: History of the Christian Church, Vol. VIII: Modern Christianity: The Swiss Reformation, William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co., Grand Rapids, Michigan, USA, 1910, page 780.

- Dr. Vollmer, Philip: 'John Calvin: Man of the Millennium,' Vision Forum, Inc., San Antonio, Texas, USA, 2008, 2008, page 87

- The History & Character of Calvinism, p. 176.

- "Out of the Flames" by Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone - Salon.com

- Marshall, John (2006). John Locke, Toleration and Early Enlightenment Culture. Cambridge Studies in Early Modern British History. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 325. ISBN 0-521-65114-X.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) That no such doctrine was ever a part of the teachings of Christ's ministry or the early Christian church has caused no end of debate as to the real intentions of those who tortured and killed those whose views differed from those of the ecclesiastical authorities at the time.- The Latin reads:

- See Stanislas Kot, "L'influence de Servet sur le mouvement atitrinitarien en Pologne et en Transylvanie", in B. Becker (Ed.), Autour de Michel Servet et de Sebastien Castellion, Haarlem, 1953.

- 'De trinitatis erroribus', Book 7.

- Andrew M. T. Dibb, Servetus, Swedenborg and the Nature of God, University Press of America, 2005, p. 93. Online at Google Book Search

- Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, Out of the Flames, Broadway Books, NY NY, 2002, pp. 71–72

- Servetus, Restitución del Cristianismo, Spanish edition by Angel Alcalá and Luis Betés, Madrid, Fundación Universitaria Española, 1980, p. 119.

- See Restitución, p. 137.

- Restitución, p. 148, 168.

- Restitución, p. 169.

- Book VII, Out of the Flames, Lawrence and Nancy Goldstone, Broadway Books, NY, NY, p. 72

- Reasons for Faith

- Bernard, D. K., The Oneness of God Word Aflame Press, 1983.

- Servetus, M., De Trinitatis Erroribus, 59b (quoted in Bainton, R.H., Hunted Heretic, Blackstone Editions, 2005, p30

- Andrew M. T. Dibb, Servetus, Swedenborg and the Nature of God, University Press of America, 2005. Online at Google Book Search

- Andrew M. T. Dibb, Servetus, Swedenborg and the Nature of Salvation, online at newchurchhistory.org

- A. Alcalá, "Los dos grandes legados de Servet: el radicalismo como método intelectual y el derecho a la libertad de conciencia", in Turia, #63-64, March 2003, Teruel (Spain), pp. 221-242.

- See Marian Hillar & Claire S. Allen, Michael Servetus: Intellectual Giant, Humanist, and Martyr, Lanham, MD, and New York: University Press of America, Inc., 2002.

- 2011 Samalways,Edmund. From Alchemy to Chemotherapy.Hermes Press, page 121-122

- Rue Michel Servet, Genéve, Switzerland at Google maps

- Goldstone, Nancy Bazelon; Goldstone, Lawrence (2003). Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World. New York: Broadway. ISBN 0-7679-0837-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)pp. 313-316 - Tribune de Genève, 4 October 2001, p. 23

- “According to the version of Bibibaldo Pickheimer, and revised by Michel de Villeneuve, on the primitive Greek copies.” Michel de Villeneuve, geography.Claudii Ptolemaeii Alexandrinii Geographicae.” printed by the Trechsel, 1535, Lyon.

- In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia. Michel de Villeneuve 1536

- 2008 Krendal, Erich. Tähtitiede ja renessanssi historioitsija painoksia Medicine

- ^ 2011 “The love for truth. Life and work of Michael Servetus”, (El amor a la verdad. Vida y obra de Miguel Servet.), printed by Navarro y Navarro, Zaragoza, collaboration with the Government of Navarra, Department of Institutional Relations and Education of the Government of Navarra, 607 pp, 64 of them illustrations, p 215-228 & 62nd illustration (XLVII)

- ^ 2011 September 9th, Francisco González Echeverría VI International Meeting for the History of Medicine,(S-11: Biographies in History of Medicine (I)), Barcelona. New Discoveries on the biography of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus) & New discoveries on the work of Michael De Villeneuve (Michael Servetus)

- ^ 1996 “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (I)” and “Sesma's Dioscorides or Medical Matter: an unknown work of Michael Servetus (II)” González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts. 35th International Congress on the History of Medicine, 2nd-8th, September, 1996, Kos Island, Greece, communications nº: 6 y 7, p. 4.

- ^ 1998 “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his Dispensarium”(Le livre de travail de Michel Servet pour ses Dioscorides et Dispensarium) and “The Dispensarium or Enquiridion, complementary of the Dioscorides of Michael Servetus” (The Enquiridion, L’oeuvre Le Dispensarium ou Enquiridion complémentaire sur le Dioscorides de Michel Servet) González Echeverría, in: Book of summaries, 36th International Congress on the History of Medicine, Tunis (Livre des Résumés, 36 ème Congrès International d’ Histoire de la médicine, Tunis), 6th-11th September 1998, (two communications), pp. 199 y 210.

- ^ 2000- “Discovery of new editions of Bibles and of two 'lost' grammatical works of Michael Servetus” and “The doctor Michael Servetus was descended from Jews”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Abstracts, 37th International Congress on the History of Medicine, September 10–15, 2000, Galveston, Texas, U.S.A., pp. 22-23.

- ^ 2005 “Deux nouvelles oeuvres de Michel Servet ou De Villeneuve: L’Andrianne en latin-espagnol et un Lexicon greco-latin”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. In: Book of Abstracts, 3rd Meeting of the ISHM, 11–14 September 2005, Patrás, Greece, p. 92.

- ^ 1998 “The 'Dispensarium' or 'Enquiridion', the complementary work of the Dioscorides, both by Servetus” and “The book of work of Michael Servetus for his Dioscorides and his 'Dispensarium'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Program of the congress and abstracts of the comunications, XI National Congress on History of Medicine, Santiago de Compostela, University of Santiago de Compostela ,pp. 83-84.

- ^ 1996 “A Spanish work attributable to Michael Servetus: 'The Dioscorides of Sesma'”. González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Varia Histórico-Médica. Edition coordinated by: Jesús Castellanos Guerrero (coord.), Isabel Jiménez Lucena, María José Ruiz Somavilla y Pilar Gardeta Sabater. Minutes from the X Congress on History of Medicine, February 1986, Málaga. Printed by Imagraf, Málaga,pp. 37-55

- ^ 2004 “The edition of Lyon of the ‘Opera omnia’ by Galen of the printer Jean Frellon (1548-1551) commented by Michael Servetus”, González Echeverría and Ancín Chandía, Teresa. In: Medicine in the presence of the new millennium: a historical perspective. Coordinators: José Martínez Pérez,Isabel Porras Gallo, Pedro Samblás Tilve, Mercedes Del Cura González, Minutes from the XII Congress in History of Medicine, 7–9 February 2002, Albacete. Ed. Of the University of Castilla-La Mancha. Cuenca, pp. 645-657.

- Acte Conmmemoratiu del cinque cententary de Miguel Servet(1511-2011), 29th November 2011, Reial Acadèmia de Medicina de Catalunya

- D'Artigny, A.G., Nouveaux mémoires d'histoire, de critique et de littérature, (Paris: 1749), t. II, p. 68. Francisco Javier González Echeverría suggested that D’Artigny (who transcribed the records from Vienne ) mistook “somme” for “Summa”, and thought it referred to the Summa of Thomas Aquinas. Thomas Aquinas was never before the XIXth century translated into any vernacular language. It seems rather that it was a summary of the Old Testament in Spanish.

- Term coined by Gonzalez Echeverria

- 1997 “Michael Servetus, editor of the Dioscorides”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Institute of Sijenienses Studies “Michael Servetus” ed, Villanueva de Sijena , Larrosa ed and “Ibercaja”, Zaragoza.

- 2001- “Portraits or printing boards of the stories of the Old Testament. Spanish Summary”, González Echeverría, Francisco Javier. Government of Navarra, Pamplona 2001. Double edition : facsimile(1543) and critical edition. Prologue by Julio Segura Moneo.

- Lalonde, Robert. Vesalius and Servetus, 2010. http://www.archive.org/details/GalileoGalileivesaliusAndServetus

Further reading

- Jean Calvin, Defensio orthodoxae fidei de sacra Trinitate contra prodigiosos errores Michaelis Serveti..., (Defense of Orthodox Faith against the Prodigious Errors of the Spaniard Michael Servetus...), Geneva, 1554. Calvin's Opere in the Corpus Reformatorum, vol. viii, 453–644. Ursus Books and Prints. Catalogue of Scarce Books, Americana, Etc. Bangs & Co, p. 41.

- Hunted Heretic: The Life and Death of Michael Servetus 1511–1553 by Roland H. Bainton. Revised Edition edited by Peter Hughes with an introduction by Ángel Alcalá. Blackstone Editions. ISBN 0-9725017-3-8.

- Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World by Lawrence Goldstone and Nancy Goldstone. ISBN 0-7679-0837-6.

- The Heretics: Heresy Through the Ages by Walter Nigg. Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1962. (Republished by Dorset Press, 1990. ISBN 0-88029-455-8)

- The History and Character of Calvinism by John T. McNeill, New York: Oxford University Press, 1954. ISBN 0-19-500743-3.

- Bonnet, Jules (1820–1892) Letters of John Calvin, Carlisle, Penn: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1980. ISBN 0-85151-323-9.

- Find in a Library with WorldCat. Contains seventy letters of Calvin, several of which discuss his plans for, and dealings with, Servetus. Also includes his final discourses and his last will and testament (April 25, 1564).

- Jules Bonnet, Letters of John Calvin, 2 vols., 1855, 1857, Edinburgh, Thomas Constable and Co.: Little, Brown, and Co., Boston—The Internet Archive

- The Man from Mars: His Morals, Politics and Religion by William Simpson, San Francisco: E.D. Beattle, 1900. Excerpts from letters of Servetus, written from his prison cell in Geneva (1553), pp. 30–31. Google Books.

- A complete translation of Christianismi Restitutio into English (the first ever) by Christopher Hoffman and Marian Hillar was published on April 30, 2007.

- Michael Servetus, Heretic or Saint? by Radovan Lovci, Prague: Prague House, 2008. ISBN 1-4382-5959-X.

External links

- Michael Servetus Research - Study with graphical proofs on the discovered new works and life aspects of Servetus (English, French and Spanish)

- Michael Servetus Institute - one of the reference center for Servetian studies (English and Spanish)

- Servetus International Society

- Michael Servetus, from the Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography

- Reformed Apologetic for Calvin's actions against Servetus

- Three Christianities: Calvin, Servetus, Swedenborg

- Hanover text on the complaints against Servetus

- Information on Calvin in Geneva which mentions Servetus

- PDF from a source relatively positive on Calvin

- SERVETUS: HIS LIFE. OPINIONS, TRIAL, AND EXECUTION.Philip Schaff. History of the Christian Church, Vol. 8, chapter 16.

- Thomas Jefferson: letter to William Short, April 13, 1820 - mention of Calvin and Servetus.

- Michael Servetus Park, Huesca (Spain)

- Hospital Miguel Servet, Zaragoza (Spain)

- Reviews of the English translation of Christianismi Restitutio, published by Edwin Mellen, April 2007

- Michael Servetus Institute: Christianismi Restitutio. Comments and quotes.

- New opera 'Le procès de Michel Servet'

- 1511 births

- 1553 deaths

- People from Monegros

- 16th-century Christian martyrs

- 16th-century Latin-language writers

- 16th-century Spanish physicians

- Antitrinitarians

- Executed Spanish people

- History of anatomy

- People executed by burning

- People executed for heresy

- Spanish Unitarians

- University of Paris alumni

- Victims of the Inquisition

- Hellenism and Christianity

- Apocalypticists