| Revision as of 19:34, 11 January 2014 view sourceArjayay (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers629,689 editsm Sp← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:23, 13 January 2014 view source Florian Blaschke (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users40,934 edits Undid revision 585458268 by Bladesmulti (talk) No, the migration is completely mainstream among actual experts. It's Hindu nationalists who keep pushing the fringe/pseudoscientific OOI stuff.Next edit → | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

| The Indo-aryan migration theories began with the study of the ] in the mid 1800s by ], and gradually evolved from a theory of a large scale invasion of a racially and technologically superior people to being a slow diffusion of small numbers of nomadic people that had a disproportionate societal impact on a large urban population. Contemporary claims of Indo-Aryan migrations are drawn from linguistic,{{sfn|Bryant|2001}} genetic,{{sfn|Wells|2002}} archaeological, literary and cultural sources. | The Indo-aryan migration theories began with the study of the ] in the mid 1800s by ], and gradually evolved from a theory of a large scale invasion of a racially and technologically superior people to being a slow diffusion of small numbers of nomadic people that had a disproportionate societal impact on a large urban population. Contemporary claims of Indo-Aryan migrations are drawn from linguistic,{{sfn|Bryant|2001}} genetic,{{sfn|Wells|2002}} archaeological, literary and cultural sources. | ||

| The debate about the origin of Indo-Aryan peoples is highly controversial, relating to the indigenous origin of peoples and culture, thus inflaming political agitation and sentiments. Throughout the evolution of the theory, many have rejected the claim of Indo-aryan origin outside of India entirely, claiming that the ]. | The debate about the origin of Indo-Aryan peoples is highly controversial in India, relating to the indigenous origin of peoples and culture, thus inflaming political agitation and sentiments. Throughout the evolution of the theory, many have rejected the claim of Indo-aryan origin outside of India entirely, claiming that the ]. | ||

| ==Development of the Aryan Migration Theory== | ==Development of the Aryan Migration Theory== | ||

Revision as of 20:23, 13 January 2014

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Languages

|

| Philology |

Origins

|

|

Archaeology

Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

Indo-Aryans Iranians East Asia Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

Religion and mythology

Others

|

Indo-European studies

|

Indo-aryan migration models discuss scenarios around the theory of an outside origin of Indo-aryan peoples, an ascribed ethno-linguistic group that speaks Indo-Aryan languages, the predominant languages of North India. Proponents of Indo-Aryan origin outside of India generally consider migrations into South Asia from Central Asia to have started around 1500 BC, as a slow diffusion during the Late Harappan period.

The Indo-aryan migration theories began with the study of the Rig Veda in the mid 1800s by Max Muller, and gradually evolved from a theory of a large scale invasion of a racially and technologically superior people to being a slow diffusion of small numbers of nomadic people that had a disproportionate societal impact on a large urban population. Contemporary claims of Indo-Aryan migrations are drawn from linguistic, genetic, archaeological, literary and cultural sources.

The debate about the origin of Indo-Aryan peoples is highly controversial in India, relating to the indigenous origin of peoples and culture, thus inflaming political agitation and sentiments. Throughout the evolution of the theory, many have rejected the claim of Indo-aryan origin outside of India entirely, claiming that the Indo-Aryan people and languages originated in India.

Development of the Aryan Migration Theory

Further information: Historical definitions of races in India and Indigenous AryansIn 19th century Indo-European studies, the language of the Rigveda was the most archaic Indo-European language known to scholars, indeed the only records of Indo-European that could reasonably claim to date to the Bronze Age. This "primacy" of Sanskrit inspired some scholars, such as Friedrich Schlegel, to assume that the locus of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat (primary homeland) had been in India, with the other dialects spread to the west by historical migration. This was however never a mainstream position even in the 19th century. Most scholars assumed a homeland either in Europe or in Western Asia, and Sanskrit must in this case have reached India by a language transfer from west to east, in a movement described in terms of invasion by 19th century scholars such as Max Müller. With the 20th century discovery of Bronze-Age attestations of Indo-European (Anatolian, Mycenaean Greek), Vedic Sanskrit lost its special status as the most archaic Indo-European language known.

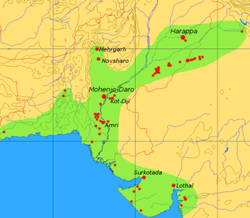

The Indus Valley civilization (IVC) was discovered in the 1920s. The discovery of the Harappa, Mohenjo-daro and Lothal sites changed the theory from a migration of "advanced" Aryan people towards a "primitive" aboriginal population to a migration of nomadic people into an advanced urban civilization, comparable to the Germanic migrations after the Fall of Rome, or the Kassite invasion of Babylonia. The decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation at precisely the period in history for which the Indo-Aryan migration had been assumed, provides independent support of the linguistic scenario. This argument is associated with the mid-20th century archaeologist Mortimer Wheeler, who interpreted the presence of many unburied corpses found in the top levels of Mohenjo-daro as the victims of conquest wars, and who famously stated that the god "Indra stands accused" of the destruction of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

In the later 20th century, ideas were refined along with data accrual, and migration and acculturation were seen as the methods whereby Indo-Aryans spread into northwest India around 1500 BC. These changes were thought to be in line with changes in thinking about language transfer in general, such as the migration of the Greeks into Greece (between 2100 and 1600 BC) and their adoption of a syllabic script, Linear B, from the pre-existing Linear A, with the purpose of writing Mycenaean Greek, or the Indo-Europeanization of Western Europe (in stages between 2200 and 1300 BC).

Scenarios

The standard model for the entry of the Indo-European languages into India is that this first wave went over the Hindu Kush, forming the Gandhara grave (or Swat) culture, either into the headwaters of the Indus or the Ganges (probably both). The Gandhara grave culture is thus the most likely locus of the earliest bearers of Rigvedic culture, and based on this Parpola (1998) assumes an immigration to the Punjab ca. 1700-1400 BC, but he also postulates a first wave of immigration from as early as 1900 BC, corresponding to the Cemetery H culture.

Kochhar argues that there were three waves of Indo-Aryan immigration that occurred after the mature Harappan phase:

- the "Murghamu" (BMAC) related people who entered Baluchistan at Pirak, Mehrgarh south cemetery, etc. and later merged with the post-urban Harappans during the late Harappans Jhukar phase (2000-1800 BCE);

- the Swat IV that co-founded the Harappan Cemetery H phase in Punjab (2000-1800 BCE);

- and the Rigvedic Indo-Aryans of Swat V that later absorbed the Cemetery H people and gave rise to the Painted Grey Ware culture (to 1400 BCE).

Among proponents of Indo-Aryan origin outside of the Indian Subcontinent, there is varying opinion on whether the migrants originated Indic literature such as the Rig Veda, cultural and social constructs such as caste, and technology such as chariots and weaponry.

Linguistic evidence

Contemporary claims of Indo-Aryan migrations are drawn from linguistic, literary, cultural, archaeological and genetic sources.

Accumulated linguistic evidence points to the Indo-Aryan languages as intrusive into South Asia, some time in the 2nd millennium BC. The language of the Rigveda, the earliest stratum of Vedic Sanskrit, is assigned to about 1500–1200 BC.

Language

Diversity

According to the linguistic center of gravity principle, the most likely point of origin of a language family is in the area of its greatest diversity. By this criterion, India, home to only a single branch of the Indo-European language family (i. e., Indo-Aryan), is an exceedingly unlikely candidate for the Indo-European homeland, compared to Central-Eastern Europe, for example, which is home to the Italic, Venetic, Illyrian, Albanian, Germanic, Baltic, Slavic, Thracian and Greek branches of Indo-European.

Both mainstream Urheimat solutions locate the Proto-Indo-European homeland in the vicinity of the Black Sea.

Dialectical variation

It has been recognized since the mid-19th century, beginning with Schmidt and Schuchardt, that a binary tree model cannot capture all linguistic alignments; certain areal features cut across language groups and are better explained through a model treating linguistic change like waves rippling out through a pond. This is true of the Indo-European languages as well. Various features originated and spread while Proto-Indo-European was still a dialect continuum. These features sometimes cut across sub-families: for instance, the instrumental, dative and ablative plurals in Germanic and Balto-Slavic feature endings beginning with -m-, rather than the usual -*bh-, e.g. Old Church Slavonic instrumental plural synъ-mi 'with sons', despite the fact that the Germanic languages are centum, while Balto-Slavic languages are satem.

The strong correspondence between the dialectical relationships of the Indo-European languages and their actual geographical arrangement in their earliest attested forms makes an Indian origin for the family unlikely.

Substrate influence

Main article: Substratum in Vedic SanskritDravidian and other South Asian languages share with Indo-Aryan a number of syntactical and morphological features that are alien to other Indo-European languages, including even its closest relative, Old Iranian. Phonologically, there is the introduction of retroflexes, which alternate with dentals in Indo-Aryan; morphologically there are the gerunds; and syntactically there is the use of a quotative marker ("iti"). These are taken as evidence of substratum influence.

It has been argued that Dravidian influenced Indic through "shift", whereby native Dravidian speakers learned and adopted Indic languages. The presence of Dravidian structural features in Old Indo-Aryan is thus plausibly explained, that the majority of early Old Indo-Aryan speakers had a Dravidian mother tongue which they gradually abandoned. Even though the innovative traits in Indic could be explained by multiple internal explanations, early Dravidian influence is the only explanation that can account for all of the innovations at once – it becomes a question of explanatory parsimony; moreover, early Dravidian influence accounts for the several of the innovative traits in Indic better than any internal explanation that has been proposed.

A pre-Indo-European linguistic substratum in South Asia would be a good reason to exclude India as a potential Indo-European homeland. However, several linguists, all of whom accept the external origin of the Aryan languages on other grounds, are still open to considering the evidence as internal developments rather than the result of substrate influences, or as adstratum effects.

Textual references

Mitanni

See also: Indo-Aryan superstrate in MitanniThe earliest written evidence for an Indo-Aryan language is found not in India, but in northern Syria in Hittite records regarding one of their neighbors, the Hurrian-speaking Mitanni. In a treaty with the Hittites, the king of Mitanni, after swearing by a series of Hurrian gods, swears by the gods Mitrašil, Uruvanaššil, Indara, and Našatianna, who correspond to the Vedic gods Mitra, Varuṇa, Indra, and Nāsatya (Aśvin). Contemporary equestrian terminology, as recorded in a horse-training manual whose author is identified as "Kikkuli the Mitannian," contains Indo-Aryan loanwords. The personal names and gods of the Mitanni aristocracy also bear significant traces of Indo-Aryan. Because of the association of Indo-Aryan with horsemanship and the Mitanni aristocracy, it is presumed that, after superimposing themselves as rulers on a native Hurrian-speaking population about the 15th-16th centuries BC, Indo-Aryan charioteers were absorbed into the local population and adopted the Hurrian language.

Brentjes argues that there is not a single cultural element of central Asian, eastern European, or Caucasian origin in the Mitannian area and associates with an Indo-Aryan presence the peacock motif found in the Middle East from before 1600 BC and quite likely from before 2100 BC.

Most scholars reject the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of Mitanni came from the Indian subcontinent as well as the possibility that the Indo-Aryans of the Indian subcontinent came from the territory of Mitanni, leaving migration from the north the only likely scenario. The presence of some BMAC loan words in Mitanni, Old Iranian and Vedic further strengthens this scenario.

Rigveda

The Rigveda is by far the most archaic testimony of Vedic Sanskrit. Bryant suggests that the Rigveda represents a pastoral or nomadic, mobile culture, centered on the Indo-Iranian Soma cult and fire worship. The purpose of hymns of the Rigveda is ritualistic, not historiographical or ethnographical, and any information about the way of life or the habitat of their authors is incidental and philologically extrapolated from the context. Nevertheless, Rigvedic data must be used, cautiously, as they are the earliest available textual evidence from India.

Views on Rigvedic society (pastoral or urban?)

Fortifications (púr), mostly made of mud and wood (palisades) are mentioned in the Rigveda. púrs sometimes refer to the abode of hostile peoples, but can also suggest settlements of Aryans themselves. Aryan tribes have more often been mentioned to live in víś, a term translated as "settlement, homestead, house, dwelling", but also "community, tribe, troops". Indra in particular is described as destroyer of fortifications, e.g. RV 4.30.20ab:

- satám asmanmáyinām / purām índro ví asiyat

- "Indra overthrew a hundred fortresses of stone."

This has led some scholars to believe that the civilization of Aryans was not an urban one.

However, the Rigveda is seen by some as containing phrases referring to elements of an urban civilization, other than the mere viewpoint of an invader aiming at sacking the fortresses. For example, in Griffith's translation of the Rigveda, Indra is compared to the lord of a fortification (pūrpati) in RV 1.173.10, while quotations such as a ship with a hundred oars in 1.116.5 and metal forts (puras ayasis) in 10.101.8 all occur in mythological contexts only.

There are other views such as, according to Gupta (as quoted in Bryant 2001:190), "ancient civilizations had both the components, the village and the city, and numerically villages were many times more than the cities. (...) if the Vedic literature reflects primarily the village life and not the urban life, it does not at all surprise us.". Gregory Possehl (as cited in Bryant 2001:195) argued that the "extraordinary empty spaces between the Harappan settlement clusters" indicates that pastoralists may have "formed the bulk of the population during Harappan times".

Views on Rigvedic reference to migration

Talageri speculates that some of the tribes that fought against king Sudas and his army on the banks of the Parusni River during the Dasarajna battle have migrated to western countries in later times, as they are connected with what he assumes are Iranian peoples (e.g. the Pakthas, Bhalanas).

Just like the Avesta does not mention an external homeland of the Zoroastrians, the Rigveda does not explicitly refer to an external homeland or to a migration. Later texts than the Rigveda (such as the Brahmanas, the Mahabharata, Ramayana and the Puranas) are more centered in the Haryana and Ganges region. This shift from the Punjab to the Gangetic plain continues the Rigvedic tendency of eastward expansion.

Rigvedic Rivers and Reference of Samudra

The geography of the Rigveda seems to be centered around the land of the seven rivers. While the geography of the Rigvedic rivers is unclear in some of the early books of the Rigveda, the Nadistuti hymn is an important source for the geography of late Rigvedic society.

The Sarasvati River is one of the chief Rigvedic rivers. The Nadistuti hymn in the Rigveda mentions the Sarasvati between the Yamuna in the east and the Sutlej in the west, and later texts like the Brahmanas and Mahabharata mention that the Sarasvati dried up in a desert.

Most scholars agree that at least some of the references to the Sarasvati in the Rigveda refer to the Ghaggar-Hakra River, while the Afghan river Haraxvaiti/Harauvati Helmand is sometimes quoted as the locus of the early Rigvedic river. Whether such a transfer of the name has taken place from the Helmand to the Ghaggar-Hakra is a matter of dispute. Identification of the early Rigvedic Sarasvati with the Ghaggar-Hakra before its assumed drying up early in the second millennium would place the Rigveda BC, well outside the range commonly assumed by Indo-Aryan migration theory.

A non-Indo-Aryan substratum in the river-names and place-names of the Rigvedic homeland would support an external origin of the Indo-Aryans. However, most place-names in the Rigveda and the vast majority of the river-names in the north-west of South Asia are Indo-Aryan. Non-Indo-Aryan names are, however, frequent in the Ghaggar and Kabul River areas, the first being a post-Harappan stronghold of Indus populations.

Srauta Sutra of Baudhayana

According to Romila Thapar, the Srauta Sutra of Baudhayana...

... refers to the Parasus and the arattas who stayed behind and others who moved eastwards to the middle Ganges valley and the places equivalent such as the Kasi, the Videhas and the Kuru Pancalas, and so on. In fact, when one looks for them, there are evidence for migration.

Kalpasutra notes that Pururavas had two sons by Urvasi, named Ayus and Amavasu, Ayus went east and Amavasu went west.

Iranian Avesta

The religious practices depicted in the Rgveda and those depicted in the Avesta, the central religious text of Zoroastrianism—the ancient Iranian faith founded by the prophet Zarathustra—have in common the deity Mitra, priests called hotṛ in the Rgveda and zaotar in the Avesta, and the use of a hallucinogenic compound that the Rgveda calls soma and the Avesta haoma. However, the Indo-Aryan deva 'god' is cognate with the Iranian daēva 'demon'. Similarly, the Indo-Aryan asura 'name of a particular group of gods' (later on, 'demon') is cognate with the Iranian ahura 'lord, god,' which 19th and early 20th century authors such as Burrow explained as a reflection of religious rivalry between Indo-Aryans and Iranians.

Most linguists such as Burrow argue that the strong similarity between the Avestan language of the Gāthās—the oldest part of the Avesta—and the Vedic Sanskrit of the Rgveda pushes the dating of Zarathustra or at least the Gathas closer to the conventional Rgveda dating of 1500–1200 BC, i.e. 1100 BC, possibly earlier. Boyce concurs with a lower date of 1100 BC and tentatively proposes an upper date of 1500 BC. Gnoli dates the Gathas to around 1000 BC, as does Mallory (1989), with the caveat of a 400 year leeway on either side, i.e. between 1400 and 600 BC. Therefore the date of the Avesta could also indicate the date of the Rigveda.

There is mention in the Avesta of Airyanəm Vaējah, one of the '16 the lands of the Aryans' as well as Zarathustra himself. Gnoli's interpretation of geographic references in the Avesta situates the Airyanem Vaejah in the Hindu Kush. For similar reasons, Boyce excludes places north of the Syr Darya and western Iranian places. With some reservations, Skjaervo concurs that the evidence of the Avestan texts makes it impossible to avoid the conclusion that they were composed somewhere in northeastern Iran. Witzel points to the central Afghan highlands. Humbach derives Vaējah from cognates of the Vedic root "vij," suggesting the region of fast-flowing rivers. Gnoli considers Choresmia (Xvairizem), the lower Oxus region, south of the Aral Sea to be an outlying area in the Avestan world. However, according to Mallory & Mair (2000), the probable homeland of Avestan is, in fact, the area south of the Aral Sea.

Later Vedic and Hindu texts

Texts like the Puranas and Mahabharata belong to a much later period than the Rigveda, making their evidence less than sufficient to be used for or against the Indo-Aryan migration theory.

Vedic

Later Vedic texts show a shift of location from the Panjab to the East: according to the Yajur Veda, Yajnavalkya (a Vedic ritualist and philosopher) lived in the eastern region of Mithila. Aitareya Brahmana 33.6.1. records that Vishvamitra's sons migrated to the north, and in Shatapatha Brahmana 1:2:4:10 the Asuras were driven to the north. In much later texts, Manu was said to be a king from Dravida. In the legend of the flood he stranded with his ship in Northwestern India or the Himalayas. The Vedic lands (e.g. Aryavarta, Brahmavarta) are located in Northern India or at the Sarasvati and Drsadvati River. However, in a post-Vedic text the Mahabharata Udyoga Parva (108), the East is described as the homeland of the Vedic culture, where "the divine Creator of the universe first sang the Vedas." The legends of Ikshvaku, Sumati and other Hindu legends may have their origin in South-East Asia.

Puranas

The Puranas record that Yayati left Prayag (confluence of the Ganges & Yamuna) and conquered the region of Sapta Sindhu. His five sons Yadu, Druhyu, Puru, Anu and Turvashu correspond to the main tribes of the Rigveda.

The Puranas also record that the Druhyus were driven out of the land of the seven rivers by Mandhatr and that their next king Gandhara settled in a north-western region which became known as Gandhara. The sons of the later Druhyu king Pracetas are supposed by some to have 'migrated' to the region north of Afghanistan though the Puranic texts only speak of an "adjacent" settlement.

Archaeological evidence

Attempts have been made to supplement the linguistic evidence with archaeological data. Erdosy notes that

... combining the discoveries of archaeology and linguistics has been complicated by mutual ignorance of the aims, complexity and limitations of the respective disciplines.

The two disciplines focus on two different problems: linguistics tries to explain the linguistic map of south Asia, while archaeology tries to understand the transition between the Indus Valley Civilisation and the Gangetic Civilisations. Archaeological artifacts may not prove or disprove migrations an sich, and it may not be possible to identify language within material culture, but archaeological remains can reflect cultural and societal change, which may correspond to changes in the population:

Evidence in material culture for systems collapse, abandonement of old beliefs and large-scale, if localised, population shifts in response to ecological catastrophe in the 2nd millennium B.C. must all now be related to the spread of Indo-Aryan languages.

According to Erdosy, the postulated movements within Central Asia can be placed within a processual framework, replacing simplistic concepts of "diffusion", "migrations" and "invasions".

Population movements

Erdosy, testing hypotheses derived from linguistic evidence against hypotheses derived from arcaeological data, states that there is no evidence of "invasions by a barbaric race enjoying technological and military superiority", but

...some support was found in the archaeological record for small-scale migrations from Central to South Asia in the late 3rd/early 2nd millennia BC."

Shaffer & Lichtenstein contend that in the second millennium BCE considerable "location processes" took place. In the eastern Punjab 79,9% and in Gujarat 96% of sites changed settlement status. According to Shaffer & Lichtenstein,

It is evident that a major geographic population shift accompanied this 2nd millennium BCE localisation process. This shift by Harappan and, perhaps, other Indus Valley cultural mosaic groups, is the only archaeologically documented west-to-east movement of human populations in South Asia before the first half of the first millennium B.C.

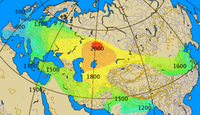

Associated cultures

The Andronovo, BMAC and Yaz cultures have been associated with Indo-Iranian migrations, with separation of Indo-Aryans proper from Proto-Indo-Iranians dated to roughly 2000–1800 BC. The Gandhara Grave, Cemetery H, Copper Hoard and Painted Grey Ware cultures are candidates for subsequent cultures associated with Indo-Aryan movements, their arrival in the Indian subcontinent being dated to the Late Harappan period.

It is believed that Indo-Aryans reached Assyria in the west and the Punjab in the east before 1500 BC: the Hurrite speaking Mitanni rulers, influenced by Indo-Aryan, appear from 1500 in northern Mesopotamia, and the Gandhara grave culture emerges from 1600. This suggests that Indo-Aryan tribes would have had to be present in the area of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (southern Turkmenistan/northern Afghanistan) from 1700 BC at the latest (incidentally corresponding with the decline of that culture).

Andronovo

The conventional identification of the Andronovo culture as Indo-Iranian is disputed by those who point to the absence south of the Oxus River of the characteristic timber graves of the steppe.

Based on its use by Indo-Aryans in Mitanni and Vedic India, its prior absence in the Near East and Harappan India, and its 19-20th century BC attestation at the Andronovo site of Sintashta, Kuzmina (1994) argues that the chariot corroborates the identification of Andronovo as Indo-Iranian. Klejn (1974) and Brentjes (1981) find the Andronovo culture much too late for an Indo-Iranian identification since chariot-wielding Aryans appear in Mitanni by the 15th to 16th century BC. However, Anthony & Vinogradov (1995) dated a chariot burial at Krivoye Lake to about 2000 BC and a BMAC burial that also contains a foal has recently been found, indicating further links with the steppes.

Mallory (as cited in Bryant 2001:216) admits the extraordinary difficulty of making a case for expansions from Andronovo to northern India, and that attempts to link the Indo-Aryans to such sites as the Beshkent and Vakhsh cultures "only gets the Indo-Iranian to Central Asia, but not as far as the seats of the Medes, Persians or Indo-Aryans". However he has also developed the "kulturkugel" model that has the Indo-Iranians taking over BMAC cultural traits but preserving their language and religion while moving into Iran and India.

Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)

Main article: Bactria-Margiana Archaeological ComplexSome scholars have suggested that the characteristically BMAC artifacts found at burials in Mehrgarh and Baluchistan are explained by a movement of peoples from Central Asia to the south.

Jarrige and Hassan (as cited in Bryant 2001:215–216) argue instead that the BMAC artifacts are explained "within the framework of fruitful intercourse" by "a wide distribution of common beliefs and ritual practices" and "the economic dynamism of the area extending from South-Central Asia to the Indus Valley."

Either way, the exclusively Central Asian BMAC material inventory of the Mehrgarh and Baluchistan burials is, in the words of Bryant (2001:215), "evidence of an archaeological intrusion into the subcontinent from Central Asia during the commonly accepted time frame for the arrival of the Indo-Aryans". However, archaeologists like B.B. Lal have seriously questioned the BMAC and Indo-Iranian "connections", and thoroughly disputed all the proclaimed relations.

Gandhara grave culture

About 1800 BC, there is a major cultural change in the Swat Valley with the emergence of the Gandhara grave culture. With its introduction of new ceramics, new burial rites, and the horse, the Gandhara grave culture is a major candidate for early Indo-Aryan presence. The two new burial rites—flexed inhumation in a pit and cremation burial in an urn—were, according to early Vedic literature, both practiced in early Indo-Aryan society. Horse-trappings indicate the importance of the horse to the economy of the Gandharan grave culture. Two horse burials indicate the importance of the horse in other respects. Horse burial is a custom that Gandharan grave culture has in common with Andronovo, though not within the distinctive timber-frame graves of the steppe.

Indus Valley Civilization

Indo-Aryan migration into the northern Punjab is approximately contemporaneous to the final phase of the decline of the Indus-Valley civilization (IVC).

Continuity

According to Erdosy, the ancient Harappans were not markedly different from modern populations in Northwestern India and present-day Pakistan. Craniometric data showed similarity with prehistoric peoples of the Iranian plateau and Western Asia, although Mohenjodaro was distinct from the other areas of the Indus Valley.

Many scholars have argued that the historical Vedic culture is the result of an amalgamation of the immigrating Indo-Aryans with the remnants of the indigenous civilization, such as the Ochre Coloured Pottery culture. Such remnants of IVC culture are not prominent in the Rigveda, with its focus on chariot warfare and nomadic pastoralism in stark contrast with an urban civilization.

Decline of Indus Valley Civilisation

The decline of the IVC from about 1,900 BC is not universally accepted to be connected with Indo-Aryan immigration. A regional cultural discontinuity occurred during the second millennium BC and many Indus Valley cities were abandoned during this period, while many new settlements began to appear in Gujarat and East Punjab and other settlements such as in the western Bahawalpur region increased in size.

Kenoyer notes that the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation is not explained by Aryan migrations,, which took place after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

According to Kennedy, there is no evidence of "demographic disruptions" after the decline of the Harappa culture. Kenoyer notes that no biological evidence can be found for major new populations in post-Harappan communities. Hemphill notes that "patterns of phonetic affinity" between Bactria and the Indus Valley Civilisation are best explained by "a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange."

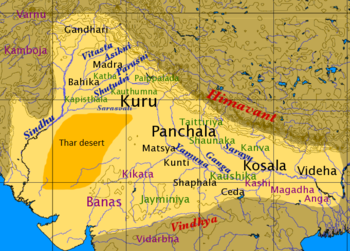

Spread of Vedic-Brahmanic culture

During the Early Vedic Period (ca.1500-800 BCE) the Vedic culture was centered in the northern Punjab, or Sapta Sindhu. During the Later Vedic Period (ca.800-500 BCE) the Vedic culture started to extend into the western Ganges Plain, centering around Kuru and Panchala, and had some influence at the central Ganges Plain after 500 BCE. Sixteen Mahajanapada developed at the Ganges Plain, of which the Kuru and Panchala became the most notable developed centers of Vedic culture, at the western Ganges Plain

The Central Ganges Plain, were Magadha gained prominence, forming the base of the Mauryan Empire, was a distinct cultural area, with new states arising after 500 BCE during the socalled "Second urbanisation". It was influenced by the Vedic culture, but differed markedly from the Kuru-Panchala region. It "was the area of the earliest known cultivation of rice in South Asia and by 1800 BCE was the location of an advanced neolitgic population associated with the sites of Chirand and Chechar". In this regio the Shramanic movements flourished, and Jainism and Buddhism originated.

Genetic evidence

Further information: Genetics and Archaeogenetics of South AsiaThe Austro-Asiatic tribals are hypothesized to have been the earliest inhabitants of India, while incoming Indo-European tribes may have displaced Dravidian-speaking tribals southward. However, the study's authors posit that a major influx into India occurred from the Northeast as well. It has also been noted that there is an underlying unity of present-day female lineages in India, and that historical gene flow has led to the obliteration of congruence between genetic and cultural affinities.

Pre-Holocene origins

Some reports emphasize the finding that tribal and caste populations in South Asia derive largely from a common maternal heritage of Pleistocene southern and western Asians, with only limited gene flow from external regions since the start of the Holocene. A 2011 genetic study "confirmed the existence of a general principal component cline stretching from Europe to south India." They also concluded that the Indian populations are characterized by two major ancestry components, one of which is spread at comparable frequency and haplotype diversity in populations of South and West Asia and the Caucasus. The second component is more restricted to South Asia and accounts for more than 50% of the ancestry in Indian populations. Haplotype diversity associated with these South Asian ancestry components is significantly higher than that of the components dominating the West Eurasian ancestry palette. Modeling of the observed haplotype diversities suggests that both Indian ancestry components are older than the purported Indo-Aryan invasion 3,500 YBP

Aryan migrations

This finding alone does not rule out the possibility of an elitist and/or male-predominant Aryan invasion of the Indian subcontinent as in fact the patterns of historical conquest and migration are ultimately reflected in terms of sex-biased admixture, with the mitochondrial heritage being more stable and of more local origin and the Y-chromosomal heritage reflecting an external influence upon the population genetic structure, as can be seen in not only such regions as South Asia, but also in such regions as Northeastern Africa (Semitic Y chromosomes vs. Niger-Kordofanian mtDNA) and Latin America (Iberian Y chromosomes vs. Amerindian mtDNA). Furthermore, the majority of researchers have found significant evidence in support of Indo-European migration and even "elite dominance" of the northern half of the Indian subcontinent, usually pointing to three separate lines of evidence:

- the previously widespread distribution of Dravidian speakers, now confined to the south of India;

- the fact that upper caste Brahmins share a close genetic affinity with West Eurasians, whereas low caste Indians tend to have more in common with aboriginals or East Asians;

- and the comparatively recent introgression of West Eurasian DNA into the aboriginal population of the post-Neolithic Indo-Gangetic plain.

Other studies also claim that there is genetic evidence in support of the traditional hypothesis of Indo-Aryan migration. Basu et al. argue that the Indian subcontinent was subjected to a series of massive Indo-European migrations about 1500 BC. In the case of paternal-line Y-chromosome DNA, the Indo-Aryan migration is associated with the R1a haplogroup, especially the R1a1a subgroup, which clusters in Eastern Europe and the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, and nicely dovetails with the observed similarities between Lithuanian and Sanskrit, and more broadly, satem languages as a whole. The strongest such claims, though, are based upon studies of autosomal DNA, not only Y DNA. Several such studies have isolated two major components of ancestry amongst Indians, one being more common in the south, and amongst lower castes, and the other more common amongst upper caste Indians, Indians speaking Indo-European languages, and also Indians living in the northwest. This second component is shared with populations from the Middle East, Europe and Central Asia, and is thought to represent at least one ancient influx of people from the northwest. According to one researcher, there is "a major genetic contribution from Eurasia to North Indian upper castes" and a "greater genetic inflow among North Indian caste populations than is observed among South Indian caste and tribal populations."

A more recent study has provided support for an influx of Indo-European migrants into the Indian subcontinent, but not necessarily an "invasion of any kind", further corroborating the findings of previous investigators, such as Bamshad et al. (2001), Wells et al. (2002) and Basu et al. (2003).

Ethno-linguistics

The terms North Indian and South Indian are ethno-linguistic categories, with North Indian corresponding to Indo-European-speaking peoples and South Indian corresponding to Dravidian-speaking; however, because of admixture, these two groups often overlap. Certain sample populations of upper caste North Indians show affinity to Central Asian caucasians, whereas southern Indian Brahmins' relationship is further.

Language change resulting from the migration of numerically small superstrate groups would be difficult to trace genetically. Historically attested events, such as invasions by Huns, Greeks, Kushans, Mughals and modern Europeans, may have had negligible genetic impact, and if they did it can be hard to trace it. For example, despite centuries of Greek rule in Northwest India, no trace of either the I-M170 or the E-M35 Y DNA paternal haplogroups associated with Greek and Macedonian males lines have been found. On the other hand, evidence of E-M35 and J-M12, another supposed Greek or Balkan marker, has been found in three Pakistani populations – the Burusho, Kalash and Pathan – who claim descent from Greek soldiers.

Controversy

The debate about the origin of Indo-Aryan peoples is highly controversial, relating to the indigenous origin of peoples and culture, thus inflaming political agitation and sentiments.

Dravidian response

Main articles: Dravidian Movement and Self-Respect MovementThe Dravidian Movement bases much of its identity on the idea of the indigenous origin of Dravidians as opposed to transgressing Indo-Aryans. This in turn lead to further responses from Indian nationalists:

From a nationalist point of view, it is clear that the concept of an Aryan-Dravidian divide is pernicious to the unity of the Hindu state, and an important aim for Hindutva and neo-Hindu scholarship is therefor to introduce a counter-narrative to the one presented by Western academic scholarship.

Caste system

Main articles: Varna (Hinduism) and Caste system in IndiaMany furthermore link Indo-Aryan migrations to the origin of caste discrimination and thus the theory is a basis of sentiments around the origin of caste discrimination, as many believe that Indo-Aryans formed the upper castes.

Hindu nationalism

Main articles: Hindu nationalism, hindu politics, and HindutvaNationalistic movements in India oppose the idea that Hinduism has partly endogenous origins. For the founders of the contemporary Hindutva movement, the Aryan migration theory presented a problem. The Hindutva-notion that the Hindu-culture originated in India was threatened by the notion that the Aryans originated outside India. Later Indian writers regarded the Aryan migration theory to be a product of colonialism, aimed to denigrate Hindus. According to them, Hindus had existed in India from times immemorial, as expressed by Golwalkar:

Undoubtedly ... we Hindus have been in undisputed and undisturbed possession of this land for over 8 or even 10 thousand years before the land was invaded by any foreign race. (Golwakar 1944)

Racism

Main articles: Aryan and Aryan raceThe debate inflames issues around racism and the idea of race, as the origin of the theory was intertwined with the desire of many in the Western world to find the origin of a pure Aryan race, the division of castes by racial basis, and the idea of an Indo-Aryan and Dravidian relating to language families rather than race.

Concurring views

Archaeologists in India remain quite skeptical:

The vast majority of professional archaeologists I interviewed in India insisted that there was no convincing archaeological evidence whatsoever to support any claims of external Indo-Aryan origins. This is part of a wider trend: archaeologists working outside of South Asia are voicing similar views.

Within India, alternative visions on the origins of the Aryan language and culture have been developed, which emphasize indigenous origins.

"Indigenous Aryans"

Main article: Indigenous Aryan TheoryThe notion of Indigenous Aryans posits that speakers of Indo-Aryan languages are "indigenous" to the Indian subcontinent. Scholars like Jim G. Shaffer and B.B. Lal note the absence of archaeological remains of an Aryan "conquest", and the high degree of physical continuity between Harappan and Post-Harappan society. They support the controversial theory that the Aryan civilization was not introduced by Aryan migrations, but originated in pre-Vedic India.

Shaffer - Continuity

Jim Shaffer has noted several problems with the arguments that the ancient Harappans were Aryans. According to Shaffer, archaeological evidence consistent with a mass population movement, or an invasion of South Asia in the pre- or proto- historic periods, has not been found. Instead, Shaffer proposes a series of cultural changes reflecting indigenous cultural developments from prehistoric to historic periods. Shaffer contends:

There were no invasions from central or western South Asia. Rather there were several internal cultural adjustments reflecting altered ecological, social and economic conditions affecting northwestern and north-central South Asia.

Lal - Fire altars

Lal notes that at Kalibangan (at the Ghaggar river) the remains of what some writers claim to be fire altars have been unearthed that are claimed to have been used for Vedic sacrifices, although the presence of animal bones does not seem consistent with Vedic rites. In addition the remains of a bathing place (suggestive of ceremonial bathing) have been found near the altars in Kalibangan. S.R. Rao found similar "fire altars" in Lothal which he thinks could have served no other purpose than Vedic ritual. The sites in Kalibangan are dated back to pre-Harappan times i.e. 3500 BC, well before any likely date for the Indo-Aryan migrations, so this may suggest that Vedic rites are indigenous to India and not brought in from outside.

Out of India Theory

Main article: Out of India TheoryIn recent years, the concept of "Indigenous Aryans" has been increasingly conflated with an "Out of India" origin of the Indo-European language family. This contrasts with the model of Indo-Aryan migration which posits that Indo-Aryan tribes migrated to India from Central Asia. Some furthermore claim that all Indo-European languages originated in India. These claims remain problematic.

See also

- The Arctic Home in the Vedas by B G Tilak

- Indo-Aryans

- Aryan

- Arya

- Ariana

- Aryavarta

- Indo-Aryan languages

- Tamil nationalism

- Rigveda

- Indo-Iranians

- Indo-Iranian languages

- BMAC

- Andronovo culture

- Kurgan

- Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia

- Indigenous Aryan Theory

- Out of India Theory

Notes

- However, this culture may also represent forerunners of the Indo-Iranians, similar to the Lullubi and Kassite invasion of Mesopotamia early in the second millennium BC.

- Krishnamurti states: "Besides, the Ṛg Vedas has used the gerund, not found in Avestan, with the same grammatical function as in Dravidian, as a non-finite verb for 'incomplete' action. Ṛg Vedic language also attests the use of it as a quotation clause complementary. All these features are not a consequence of simple borrowing but they indicate substratum influence (Kuiper 1991: ch 2)".

- Mallory: "It is highly improbable that the Indo-Aryans of Western Asia migrated eastwards, for example with the collapse of the Mitanni, and wandered into India, since there is not a shred of evidence — for example, names of non-Indic deities, personal names, loan words — that the Indo-Aryans of India ever had any contacts with their west Asian neighbours. The reverse possibility, that a small group broke off and wandered from India into Western Asia is readily dismissed as an improbably long migration, again without the least bit of evidence."

- Leach (1990) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFLeach1990 (help), as cited in Bryant (2001:222)

"Ancient Indian history has been fashioned out of compositions, which are purely religious and priestly, which notoriously do not deal with history, and which totally lack the historical sense.(...)." F.E. Pargiter 1922. However "the Vedic literature confines itself to religious subjects and notices political and secular occurrences only incidentally (...)". Cited in R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker (editors): The history and culture of the Indian people. Volume I, The Vedic age. Bombay : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan 1951, p.315, with reference to F.E. Pargiter. - Mallory (1989) "...the culture represented in the earliest Vedic hymns bears little similarity to that of the urban society found at Harappa or Mohenjo-daro. It is illiterate, non-urban, non-maritime, basically uninterested in exchange other than that involving cattle, and lacking in any forms of political complexity beyond that of a king whose primary function seems to be concerned with warfare and ritual."

- According to Cardona, "there is no textual evidence in the early literary traditions unambiguously showing a trace" of an Indo-Aryan migration.

- ^ Archaeological evidence of continuity need not be conclusive. A similar case has been Central Europe, where the archaeological evidence shows continuous linear development, with no marked external influences. Archaeological continuity can be supported for every Indo-European-speaking region of Eurasia, not just India. Several historically documented migrations, such as those of the Helvetii to Switzerland, the Huns into Europe, or Gaelic-speakers into Scotland are not attested in the archaeological record.> As sums up, "archaeology can verify the occurrence of migration only in exceptional cases".

- Comparing the Harappan and Gandhara cultures, Kennedy states: "Our multivariate approach does not define the biological identity of an ancient Aryan population, but it does indicate that the Indus Valley and Gandhara peoples shared a number of craniometric, odontometric and discrete traits that point to a high degree of biological affinity." Kennedy in

- Kennedy: "Have Aryans been identified in the prehistoric skeletal record from South Asia? Biological anthropology and concepts of ancient races", in , at p. 49.

- Cephalic measures, however, may not be a good indicator as they do not necessarily indicate ethnicity and they might vary in different environments. On the use of which, however, see

- Kenoyer: "Although the overall socioeconomic organization changed, continuities in technology, subsistence practices, settlement organization, and some regional symbols show that the indigenous population was not displaced by invading hordes of Indo-Aryan speaking people. For many years, the 'invasions' or 'migrations' of these Indo-Aryan-speaking Vedic/Aryan tribes explained the decline of the Indus civilization and the sudden rise of urbanization in the Ganges-Yamuna valley. This was based on simplistic models of culture change and an uncritical reading of Vedic texts..."

- Kennedy: "there is no evidence of demographic disruptions in the north-western sector of the Subcontinent during and immediately after the decline of the Harappan culture. If Vedic Aryans were a biological entity represented by the skeletons from Timargarha, then their biological features of cranial and dental anatomy were not distinct to a marked degree from what we encountered in the ancient Harappans." Kennedy in

- Kenoyer: "there was an overlap between Late Harappan and post-Harappan communities...with no biological evidence for major new populations." Kenoyer as quoted in

- Hemphill: "the data provide no support for any model of massive migration and gene flow between the oases of Bactria and the Indus Valley. Rather, patterns of phonetic affinity best conform to a pattern of long-standing, but low-level bidirectional mutual exchange. "Hemphill 1998 "Biological Affinities and Adaptations of Bronze Age Bactrians: III. An initial craniometric assessment", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 106, 329-348.; Hemphill 1999 "Biological Affinities and Adaptations of Bronze Age Bactrians: III. A Craniometric Investigation of Bactrian Origins", American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 108, 173-192

- The "First urbanisation" was the Indus Valley Civilisation.

- ^ Jainism and Buddhism did not originate from the historical Vedic religion, but are indigenous to India itself, just like Yoga and Samkhya. Hinduism itself is "a fusion of Arian and Dravidian cultures". Among its roots are the historical Vedic religion of Iron Age India, but also the religions of the Indus Valley Civilisation, the Shramana or renouncer traditionsof north-east India, and "popular or local traditions". The "Hindu synthesis" emerged around the beginning of the Common Era.

- "There is general agreement that Indian caste and tribal populations share a common late Pleistocene maternal ancestry in India." Sahoo et al. (2006) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFSahoo_et_al.2006 (help)

- Reich et al. (2009) speculate on pre-Aryan 'Proto-Indo-European': "It is tempting to assume that the population ancestral to ANI and CEU spoke 'Proto-Indo-European', which has been reconstructed as ancestral to both Sanskrit and European languages, although we cannot be certain without a date for ANI–ASI mixture."

- See also Breaking India

- See also "Dr. S. Kalyanaraman, Harvard University’s international scandal unravels a global Hindu conspiracy.

- See also "Savarkar, Essentials of Hindutva, and Edwin Bryant, The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate

- Zimmer: does not derive from Brahman-Aryan sources, but reflects the cosmology and anthropology of a much older pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India - being rooted in the same subsoil of archaic metaphysical speculation as Yoga, Sankhya, and Buddhism, the other non-Vedic Indian systems."

- Hindutva-theory faces other challenges as well. It includes Jainism and Buddhism into its notions of 'Hinduness', as part of the Indian heritage. A recent strategy, exemplified by Rajiv Malhotra, is the use of the term dhamma as a common denominator, which also includes Jainism and Buddhism. Nevertheless, Jainism and Buddhism have distinct origins.

- Shaffer: "Current archaeological data do not support the existence of an Indo-Aryan or European invasion into South Asia any time in the pre- or protohistoric periods. Instead, it is possible to document archaeologically a series of cultural changes reflecting indigenous cultural developments from prehistoric to historic periods". Shaffer as cited in

- Häusler, as cited in

- Mallory, in

- Bryant: "India is not the only Indo-European-speaking area that has not revealed any archaeological traces of immigration." As

- , as cited in

- Bryant: "It must be stated immediately that there is an unavoidable corollary of an Indigenist position. If the Indo-Aryan languages did not come from outside South Asia, this necessarily entails that India was the original homeland of all the other Indo-European languages."

- Bryant: "There is at least a series of archaeological cultures that can be traced approaching the Indian subcontinent, even if discontinuous, which does not seem to be the case for any hypothetical east-to-west emigration."

References

- ^ Bryant 2001.

- ^ Wells 2002. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWells2002 (help)

- "Read Indussian", by Senthil Kumar A S, - Page 123

- "Tense and Aspect in Indo-European Languages", by John Hewson, Page 229

- Kochhar 2000, p. 185-186. sfn error: no target: CITEREFKochhar2000 (help)

- ^ Bryant (2001:91)

- Bamshad (2001)

- ^ Anthony & Vinogradov (1995)

Kuzmina (1994), Klejn (1974), and Brentjes (1981), as cited in Bryant (2001:206) - Mallory & Mair (2000)

- Sapir (1949:455)

Latham, as cited in Mallory (1989:152) - Mallory (1989:152–153)

- Mallory (1989:177–185)

- Hock (1991, p. 454)

- Fortson (2004, p. 106)

- Hock (1996), "Out of India? The linguistic evidence", in Bronkhorst & Deshpande (1999) harvtxt error: no target: CITEREFBronkhorstDeshpande1999 (help).

- Erdosy (1995:18)

- Thomason & Kaufman (1988:141–144)

- Bryant (2001:76)

- Hamp 1996 and Jamison 1989, as cited in Bryant 2001:81–82

- Hock 1975/1984/1996 and Tikkanen 1987, as cited in Bryant (2001:78–82)

- Mallory & Mair (2000)

Mallory (1989)

StBoT 41 (1995)

Thieme, as cited in Bryant (2001:136) - Bryant 2001, p. 137.

- Mallory 1989.

- Witzel 2003 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWitzel2003 (help)

- Rau 1976

- Talageri 2000

- e.g. MacDonnel and Keith, Vedic Index, 1912

- R. C. Majumdar and A. D. Pusalker (editors): The history and culture of the Indian people. Volume I, The Vedic age. Bombay : Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan 1951, p.220

- ^ Cardona 2002, p. 33-35.

- e.g. RV 2.12; RV 4.28; RV 8.24

- "Encyclopaedia of Ancient Indian Geography, Volume 2", by Subodh Kapoor, p.590

- "Discovering the Vedas: Origins, Mantras, Rituals, Insights", p. 7, by Frits Staal

- Bryant (2001)

- Witzel (1999)

- Burrow as cited in Mallory (1989).

- Bryant (2001:131)

Mallory (1989)

Mallory & Mair (2000)

Burrow, as cited in Mallory (1989)

Boyce and Gnoli, as cited in Bryant (2001:132) - Bryant (2001:133)

Gnoli, Boyce, Skjaervo, and Witzel, as cited in Bryant (2001:133)

Humbach and Gnoli, as cited in Bryant (2001:327)

Mallory & Mair (2000) - (Bryant 2001: 64)

- Elst 1999, with reference to L.N. Renou

- e.g. Bhagavata Purana (VIII.24.13)

- e.g. Satapatha Brahmana, Atharva Veda

- e.g. RV 3.23.4., Manu 2.22, etc. Kane, Pandurang Vaman: History of Dharmasastra: (ancient and mediaeval, religious and civil law) — Poona : Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, 1962-1975

- Talageri 1993, The Aryan Invasion Theory, A Reappraisal

- Elst 1999, chapter 5, with reference to Bernard Sergent

- Talageri 1993, 2000; Elst 1999

- Bhagavata Purana 9.23.15-16; Visnu Purana 4.17.5; Vayu Purana 99.11-12; Brahmanda Purana 3.74.11-12 and Matsya Purana 48.9.

- see e.g. Pargiter 1979; Talageri 1993, 2000; Bryant 2001; Elst 1999

- ^ Erdosy 1995.

- ^ Erdosy 1995, p. 24.

- Erdosy 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Erdosy 1995, p. 5.

- Erdosy 1995, p. 5-6.

- Erdosy 1995, p. 23.

- Erdosy 1995, p. 139.

- Klejn (1974), Lyonnet (1993), Francfort (1989), Bosch-Gimpera (1973), Hiebert (1998), and Sarianidi (1993), as cited in Bryant (2001:206–207)

- Allchin 1995:47–48 harvcolnb error: no target: CITEREFAllchin1995 (help)

Hiebert & Lamberg-Karlovsky (1992), Kohl (1984), and Parpola (1994), as cited in Bryant (2001:215) - Mallory (1989)

- Erdosy 1995, p. 49.

- Holloway 2002.

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 190.

- ^ Erdosy 1995, p. 54.

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 231.

- ^ Samuel 2010.

- ^ Samuel 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Samuel 2010, p. 48-51.

- Samuel 2010, p. 42-48.

- Samuel 2010, p. 49.

- ^ Kivisild et al. (2003) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFKivisild_et_al.2003 (help)

- Sharma et al. (2005) harvcoltxt error: no target: CITEREFSharma_et_al.2005 (help)

- Firasat; Khaliq, Shagufta; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Papaioannou, Myrto; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Underhill, Peter A; Ayub, Qasim (2006), "Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan", European Journal of Human Genetics, 15 (1): 121–126, doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201726, PMC 2588664, PMID 17047675

- Saraswathi. Towards Self-Respect, pp. 89 & 90.

- Fosse 2013, p. 454.

- Witzel, Michael (2006), "Rama's realm: Indocentric rewritings of early South Asian History", in Fagan, Garrett, Archaeological Fantasies: How pseudoarchaeology misrepresents the past and misleads the public, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-30592-6

- Gupta 2007, p. 108-109.

- ^ Gupta 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Gupta 2007, p. 109.

- Springer 2012.

- Zimmer 1951.

- Zimmer 1951, p. 217.

- Lockard 2007, p. 50.

- Narayanan 2009, p. 11.

- Lockard 2007, p. 52.

- Hiltebeitel 2013, p. 3. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHiltebeitel2013 (help)

- Jones 2006, p. xviii. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJones2006 (help)

- ^ Gomez 2013, p. 42.

- ^ Flood 1996, p. 16.

- Hiltebeitel 2002.

- Larson 2009.

- Thapar, Romila (1 January 1996), "The Theory of Aryan Race and India: History and Politics", Social Scientist, 24 (1/3), Social Scientist: 3–29, doi:10.2307/3520116, ISSN 0970-0293, JSTOR 3520116.

- Leopold, Joan (1974), "British Applications of the Aryan Theory of Race to India, 1850–1870", The English Historical Review, 89 (352): 578–603, doi:10.1093/ehr/LXXXIX.CCCLII.578.

- Bryant 2001, pp. 231 ff.

- Kennedy 2000, p. 371.

- ^ Shaffer 1984.

- Bryant 2001, p. 232.

- Bryant 2001, p. 192.

- Bryant 2001, p. 141.

- Blench & Spriggs 1997.

- ^ Bryant 2001, p. 235.

- Anthony 1986. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAnthony1986 (help)

- Sinor 1990, p. 203. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSinor1990 (help)

- Mallory 1989, p. 166.

- Cavalli-Sforza 2000.

- B.B. Lal. Frontiers of the Indus Civilization.1984:57-58)

- (S.R. Rao. The Aryans in Indus Civilization.1993:175)

- "Advent of the Aryans in India", p. 24, by Ram Sharan Sharma, year = 1999

- Bryant 2001, p. 6.

- Bryant 2001, p. 236.

Sources

Published sources

- Allchin, F. Raymond (1995), The Archaeology of Early History South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, Cambridge University Press.

- Anthony, David; Vinogradov, Nikolai (1995), "Birth of the Chariot", Archaeology, vol. 48, no. 2, pp. 36–41.

- Bamshad, Michael (2001), "Genetic Evidence on the Origins of Indian Caste Populations", Genome Res., 11 (6): 994–1004, doi:10.1101/gr.GR-1733RR, PMC 311057, PMID 11381027.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew, eds. (1997), Archaeology and Language, vol. I: Theoretical and Methodological Orientations, London: Routledge.

- edited by Johannes Bronkhorst & Madhav M. Deshpande. (1999), Bronkhorst, J.; Deshpande, M.M. (eds.), Aryan and Non-Aryan in South Asia: Evidence, Interpretation, and Ideology, Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University, ISBN 1-888789-04-2

{{citation}}:|author=has generic name (help) - Bryant, Edwin (2001), The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-513777-9.

- Bryant, Edwin F.; Patton, Laurie L., eds. (2005), The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and inference in Indian history, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7007-1463-4

- Cardona, George (2002), The Indo-Aryan languages, RoutledgeCurzon, ISBN 0-7007-1130-9

- Cavalli-Sforza, Luigi Luca (2000), Genes, Peoples, and Languages, New York: North Point Press.

- Chakrabarti, D.K. The Early use of Iron In India. Dilip K. Chakrabarti.1992. New Delhi: The Oxford University Press.

- Chakrabarti, D.K. 1977b. India and West Asia: An Alternative Approach. Man and Environment 1:25-38.

- Chaubey; et al. (2007), "Peopling of South Asia: investigating the caste-tribe continuum in India", BioEssays, vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 91–100, doi:10.1002/bies.20525, PMID 17187379.

- Dhavalikar, M. K. 1995, "Fire Altars or Fire Pits?", in Sri Nagabhinandanam, Ed V Shivananda and M. K. Visweswara, Bangalore.

- Diakonoff, Igor M.; Kuz'mina, E. E.; Ivantchik, Askold I. (1995), "Two Recent Studies of Indo-Iranian Origins", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 115, no. 3, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 115, No. 3, pp. 473–477, doi:10.2307/606224, JSTOR 606224.

- Elst, Koenraad (1999), Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, ISBN 81-86471-77-4.

- Erdosy, George, ed. (1995), The Indo-Aryans of Ancient South Asia: Language, Material Culture and Ethnicity, Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 3-11-014447-6

- Flood, Gavin D. (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge University Press

- Fortson, Benjamin W. IV (2004), Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 1-4051-0316-7

- Fosse, L.M. (2013), Aryan past and post-colonial present: the polemics and politics of indigenous Aryanism. In: Edwin Bryant & Laurie Patton, "The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History", pp. 434-467, Routledge

- Gomez, Luis O. (2013), Gomez Indian Buddhism Buddhism in India. In: Joseph Kitagawa, "The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture", Routledge

{{citation}}: Check|url=value (help) - Gupta, Tania Das (2007), Race and Racialization: Essential Readings, Canadian Scholars’ Press

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2002), Hinduism. In: Joseph Kitagawa, "The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture", Routledge

- Hock, Hans (1991), Principles of Historical Linguistics, Walter de Gruyter

- Holloway, Ralph L. (November 2002), "Head to head with Boas: Did he err on the plasticity of head form?", Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A., 99 (23): 14622–14623, Bibcode:2002PNAS...9914622H, doi:10.1073/pnas.242622399, PMC 137467, PMID 12419854.

- Jamison, Stephanie W. (2006), "Review of Bryant & Patton 2005" (PDF), Journal of Indo-European Studies, 34

- Jones, Constance; Ryan, James D. (2006), Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Infobase Publishing

- Kennedy, Kenneth A. R. (2000), God-apes and Fossil Men: Paleoanthropology of South Asia, University of Michigan Press

- Kivisild, T. (February 2003), "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations", American Journal of Human Genetics, 72 (2): 313–332, doi:10.1086/346068, PMC 379225, PMID 12536373.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help). - Kochhar, Rajesh (2000), The Vedic People: Their History and Geography, Sangam Books

- Kuz'mina, E. E. (1994), Откуда пришли индоарии? (Whence came the Indo-Aryans), Moscow: Российская академия наук (Russian Academy of Sciences).

- Lal, B.B., (1984) Frontiers of the Indus Civilization.1984.

- Lal, B.B., (1998) New Light on the Indus Civilization, Aryan Books, Delhi 1998

- Lal, B.B. 2005. The Homeland of the Aryans. Evidence of Rigvedic Flora and Fauna & Archaeology, New Delhi, Aryan Books International.

- Lal, B.B. 2002. The Saraswati Flows on: the Continuity of Indian Culture. New Delhi: Aryan Books International

- Larson, Gerald James (2009), Hinduism. In: "World Religions in America: An Introduction", Westminster John Knox Press

- Lockard, Craig A. (2007), Societies, Networks, and Transitions. Volume I: to 1500, Cengage Learning

- Mallory, J.P. (1989), In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology, and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2000), The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, London: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0-500-05101-1.

- Narayanan, Vasudha (2009), Hinduism, The Rosen Publishing Group

- Pargiter, F.E. 1979. Ancient Indian Historical Tradition. New Delhi: Cosmo.

- Parpola, Asko (1998), "Aryan Languages, Archaeological Cultures, and Sinkiang: Where Did Proto-Iranian Come into Being and How Did It Spread?", in Mair (ed.), The Bronze Age and Early Iron Age Peoples of Eastern and Central Asia, Washington, D.C.: Institute for the Study of Man, ISBN 0-941694-63-1

- Parpola, Asko (2005), "Study of the Indus script", Transactions of the 50th International Conference of Eastern Studies, Tokyo: The Tôhô Gakkai, pp. 28–66.

- S.R. Rao. The Aryans in Indus Civilization.1993

- Reich, David (24 September 2009), "Reconstructing Indian population history", Nature, 461 (7263): 489–494, Bibcode:2009Natur.461..489R, doi:10.1038/nature08365, PMC 2842210, PMID 19779445, retrieved 2 October 2009.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Sahoo, Sanghamitra (January 2006), "A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios", PNAS, 103 (4): 843–848, Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..843S, doi:10.1073/pnas.0507714103, PMC 1347984, PMID 16415161.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Samuel, Geoffrey (2010), The Origins of Yoga and Tantra, Cambridge University Press

- Sapir, Edward (1949), Mandelbaum, David G. (ed.), Selected Writings in Language, Culture, and Personality, University of California Press (published 1985), ISBN 0-520-01115-5.

- Sengupta, S. (1 February 2006), "Polarity and temporality of high-resolution y-chromosome distributions in India identify both indigenous and exogenous expansions and reveal minor genetic influence of Central Asian pastoralists", American Journal of Human Genetics, 78 (2), The American Society of Human Genetics: 201–221, doi:10.1086/499411, PMC 1380230, PMID 16400607, retrieved 3 December 2007.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Shaffer, Jim (1984), The Indo-Aryan Invasions: Cultural Myth and Archaeological Reality. In: "In The Peoples of South Asia", edited by J. R. Lukacs, pp. 74—90, New York: Plenum Press

- Sharma, S. (2005), "Human mtDNA hypervariable regions, HVR I and II, hint at deep common maternal founder and subsequent maternal gene flow in Indian population groups", Journal of Human Genetics, 50 (10): 497–506, doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0284-2, PMID 16205836.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Springer (2012), International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 16, No. 3, December 2012

- Talageri, Shrikant G. (2000), The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan, ISBN 81-7742-010-0, retrieved May 2007

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help). - Talageri, Shrikant G. (1993), Aryan Invasion Theory and Indian Nationalism, ISBN 81-85990-02-6.

- Thapar, Romila. 1966. A History of India: Volume 1 (Paperback). ISBN 0-14-013835-8

- Trautmann, Thomas (2005), The Aryan Debate, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-566908-8.

- Thomason, Sarah Grey; Kaufman, Terrence (1988), Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics, University of California Press (published 1991), ISBN 0-520-07893-4.

- Tikkanen, Bertil (1999), "Archaeological-linguistic correlations in the formation of retroflex typologies and correlating areal features in South Asia", in Blench, Roger; Spriggs, Matthew (eds.), Archaeology and Language, vol. IV: Language Change and Cultural Transformation, London: Routledge, pp. 138–148.

- Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey (illustrated ed.). Princeton University Press. ISBN 069111532X.

- Witzel, Michael (1999), "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Ṛgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)" (PDF), Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, vol. 5, no. 1.

- Witzel, Michael (2006), "Rama's realm: Indocentric rewritings of early South Asian archaeology and history", in Fagan, Garrett G. (ed.), Archaeological Fantasies: How Pseudoarchaeology Misrepresents the Past and Misleads the Public, London/New York: Routledge, pp. 203–232, ISBN 0-415-30592-6.

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1951), Philosophies of India, Princeton University Press

Web-sources

- ... Like true friends of some city's lord within them held in good rule with sacrifice they help him. http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv01173.htm

- "... What time ye carried Bhujyu to his dwelling, borne in a ship with hundred oars, O Aśvins." http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv01116.htm

- "... Make iron forts, secure from all assailants let not your pitcher leak: stay it securely." http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/rigveda/rv10101.htm

- The Saraswati:- Where lies the mystery

- ^ Vishal Agarwal (2005), On Perceiving Aryan Migrations in Vedic Ritual Texts. Purātattva, Issue 36, p.155-165

- http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/19th-century-paradigms.html

- ^ Frank Raymon Allchin, Early Vedic Period, Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ Joseph E. Scwartzberg, Later Vedic period (c. 800–c. 500 bce), Encyclopedia Britannica

- ^ R. Champakalakshmi, The beginning of the historical period, c. 500–150 bce, Encyclopedia Britannica

- http://genepath.med.harvard.edu/~reich/2009_Nature_Reich_India.pdf

- Shared and Unique Components of Human Population Structure and Genome-Wide Signals of Positive Selection in South Asia, Mait Metspalu et al., American Journal of Human Genetics, Volume 89, Issue 6, 9 December 2011, Pages 731–744.

- http://www.hygienecentral.org.uk/pdf/Cordaux%20Current.pdf

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1376879/?tool=pmcentrez

- http://www.pnas.org/content/107/suppl.2/8954.full

- ^ http://genome.cshlp.org/content/11/6/994.full

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC419996/

- http://genome.cshlp.org/content/13/10/2277.full.pdf+html

- ^ http://genome.cshlp.org/content/13/10/2277.full

- ^ http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.21246/abstract

- http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ajpa.1330710305/abstract

- http://www.imtech.res.in/raghava/reprints/IGVdb.pdf

- http://genome.cshlp.org/content/13/10/2277.short

- Religions - Hinduism: History of Hinduism. BBC. Retrieved on 2013-07-28.

- ^ Stanley A. Wolpert, The appearance of Indo-Aryan speakers, Encyclopedia Britannica

External links

Overview

- Hindu students council, North carolina state university, Aryan Invasion/Migration Theory

- Archaeology Online, The Aryan Invasion: theories, counter-theories and historical significance

- Thapar, Romila: The Aryan question revisited (1999)

- Francesco Brighenti, Selected Internet Resources on the Aryan Migration Theory (AMT) Debate

Linguistics

- Michael Witzel: The Home of the Aryans

- Agarwal, Vishal: Is There Vedic Evidence for the Indo-Aryan Immigration to India? (pdf)

Archaeology

- Cache of Seal Impressions Discovered in Western India

- Central Asia 2000-1000BC (Metmuseum.org)

- Lal, B.B.: The Homeland of Indo-European Languages and Culture: Some Thoughts By Archaeologist B.B. Lal

- Danino, Michel: The Indus-Sarasvati Civilization and its Bearing on the Aryan Question Article by Michel Danino

- Agrawal, D.P.: The Indus Civilization = Aryans equation: Is it really a Problem? By D.P. Agrawal (pdf)

Genetics

- Genetic Evidence on the origins of Indian Caste Population, Genome Research, 2001

- A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios, PNAS paper, 2006

- Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists, AJHG paper, 2006

- Peopling of South Asia: investigating the caste-tribe continuum in India

Critics

- Elst, Koenraad: Update on the Aryan Invasion Theory - K. Elst's Online book, Articles, Book reviews

- Kazanas, Nicholas homepage Articles by Nicholas Kazanas

- The Myth of the Aryan Invasion by David Frawley mirror

| Ancient India and Central Asia | |

|---|---|

| Archaeology and prehistory | |

| Historical peoples and clans | |

| States | |

| Mythology and literature | |

Categories: