| Revision as of 21:36, 18 February 2015 view sourceSchroCat (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers113,555 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 22:18, 18 February 2015 view source SchroCat (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers113,555 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{use dmy dates|date=March 2012}} | {{use dmy dates|date=March 2012}} | ||

| {{EngvarB|date=February 2015}} | |||

| {{under construction}} | {{under construction}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The '''Great Stink''' |

The '''Great Stink''' was an event in the July and August 1858 during which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated ] and ] from industrial activities was very strong in central London. The problem had been mounting for some years, with an ageing, ramshackle and inadequate sewer system that emptied directly into the ]. The smell from the effluent was considered the method of transmitting contagious diseases through the ] it gave off, and three outbreaks of ] prior to the Great Stink were blamed on the ongoing problems with the river. | ||

| The smell, and people's fears of its possible effects, focussed the minds of local and national administrators who had been looking at possible solutions for the problem. The authorities accepted a proposal from the ] ] to move the effluent eastwards along a series of interconnecting sewers that sloped out towards ]s outside the metropolitan area. Work began at the beginning of 1859 and lasted until 1875, building high-, mid- and low-level systems for the new ] and ]s. To aid the drainage, ] were placed to lift the sewage from lower levels into higher pipes; two of the more ornate stations, ] in ] and ] on the ] are, {{As of|2015|lc=y}}, ] for protection by ]. Bazalgette's plan introduced the three embankments to London in which the sewers ran—the ], ] and ]s. | |||

| Bazalgette's work ensured that sewage was no longer dumped onto the shores of the Thames and brought an end to the cholera outbreaks; his actions mean he probably saved more lives than any other Victorian official. His sewer system operated into the 21st century servicing a city that grew to over eight million. The historian ] considers that Bazalgette should be considered a London hero. | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background== | ||

Revision as of 22:18, 18 February 2015

| This article or section is in a state of significant expansion or restructuring. You are welcome to assist in its construction by editing it as well. If this article or section has not been edited in several days, please remove this template. If you are the editor who added this template and you are actively editing, please be sure to replace this template with {{in use}} during the active editing session. Click on the link for template parameters to use.

This article was last edited by SchroCat (talk | contribs) 9 years ago. (Update timer) |

The Great Stink was an event in the July and August 1858 during which the hot weather exacerbated the smell of untreated human waste and effluent from industrial activities was very strong in central London. The problem had been mounting for some years, with an ageing, ramshackle and inadequate sewer system that emptied directly into the Thames. The smell from the effluent was considered the method of transmitting contagious diseases through the miasma it gave off, and three outbreaks of Cholera prior to the Great Stink were blamed on the ongoing problems with the river.

The smell, and people's fears of its possible effects, focussed the minds of local and national administrators who had been looking at possible solutions for the problem. The authorities accepted a proposal from the civil engineer Joseph Bazalgette to move the effluent eastwards along a series of interconnecting sewers that sloped out towards outfalls outside the metropolitan area. Work began at the beginning of 1859 and lasted until 1875, building high-, mid- and low-level systems for the new Northern and Southern Outfall Sewers. To aid the drainage, pumping stations were placed to lift the sewage from lower levels into higher pipes; two of the more ornate stations, Abbey Mills in Stratford and Crossness on the Erith Marshes are, as of 2015, listed for protection by English Heritage. Bazalgette's plan introduced the three embankments to London in which the sewers ran—the Victoria, Chelsea and Albert Embankments.

Bazalgette's work ensured that sewage was no longer dumped onto the shores of the Thames and brought an end to the cholera outbreaks; his actions mean he probably saved more lives than any other Victorian official. His sewer system operated into the 21st century servicing a city that grew to over eight million. The historian Peter Ackroyd considers that Bazalgette should be considered a London hero.

Background

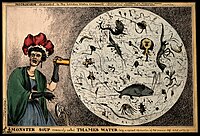

Satirical impressions of the state of Thames water in the early- to mid-19th century "Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water" (1828), by the artist William Heath

"Monster Soup commonly called Thames Water" (1828), by the artist William Heath "A Drop of Thames Water", as seen by Punch (1850)

Satirical impressions of Father Thames in the mid-19th century, from Punch

"A Drop of Thames Water", as seen by Punch (1850)

Satirical impressions of Father Thames in the mid-19th century, from Punch "Dirty Father Thames", (1848)

"Dirty Father Thames", (1848)Filthy river, filthy river,

Foul from London to the Nore,

What art thou but one vast gutter,

One tremendous common shore?

"Michael Faraday giving his card to Father Thames", commenting on Faraday's suggestion of using pieces of white cards to gauge the Thames's "degree of opacity"

"Michael Faraday giving his card to Father Thames", commenting on Faraday's suggestion of using pieces of white cards to gauge the Thames's "degree of opacity"

Brick sewers had first been built in London from the 17th century when sections of the Fleet and Walbrook rivers had been covered for that purpose. In the century preceding 1856, over a hundred sewers were constructed in London, and at that date the city had around 200,000 cesspits and 360 sewers. Some of the cesspits leaked methane or swamp gases, which often caught fire and exploded, leading to a loss of life, while many of the sewers were in a poor state of repair. During the early 19th century improvements had been undertaken in the supply of water to Londoners, and by 1858 many of the city's wooden medieval water pipes were being replaced with iron ones. This, combined with the introduction of flushing toilets and the doubling of the city's population, led to more water being flushed into the sewers, along with the associated effluent, and the outfalls from factories, slaughterhouses and other industrial activities, which put additional strain on the already failing system. Much of this outflow either overflowed, or was discharged directly, into the Thames. The situation was described by the scientist Michael Faraday in a letter to The Times in July 1855 in which he was so shocked at the state of the Thames, he dropped pieces of white paper into the river to "test the degree of opacity". His conclusion was that "Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface, even in water of this kind. ... The smell was very bad, and common to the whole of the water; it was the same as that which now comes up from the gully-holes in the streets; the whole river was for the time a real sewer." The smell from the river was so bad that in 1857 the government poured chalk lime, chloride of lime and carbolic acid to ease the stench.

The prevailing thought in Victorian healthcare concerning the transmission of contagious diseases was based around the miasma theory, which held the most communicable diseases were caused by the inhalation of contaminated air. This contamination could take the form of the odour of rotting corpses or sewerage, but also rotting vegetation, or the exhaled breath of someone already diseased. Miasma was believed by most to be the method of transmission of cholera, which was on the rise in 19th century Europe, and was deeply feared by all because of the speed it could spread, and its high fatality rates.

The first major cholera epidemic to hit London was in 1831, when it claimed 6,536 victims; in 1848–49 there was a second outbreak in which 14,137 London residents died, and this was followed by a further outbreak in 1853–54 in which 10,738 died. During the second outbreak, Dr John Snow, a London-based physician, noticed that the rates of death were higher in those areas supplied by the Lambeth and the Southwark and Vauxhall water companies. He published a paper, On the Mode of Communication of Cholera (1849) which posited the theory of water-borne transmission of disease, rather than the miasma theory; little attention was paid to the paper. Following the third cholera outbreak, Snow published an update to his treatise, after he focussed on the effects in Broad Street, Soho. Snow had removed the handle from the local water pump, with a resulting fall in deaths; the well from which the water was drawn had a leaking sewer running nearby.

Local government

The civic infrastructure overseeing the management of London's sewers had gone through several changes in the 19th century. In 1848 the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers (MCS) was established at the urging of Edwin Chadwick and a Royal Commission. The Commission superseded seven of the eight authorities that had managed London's sewers since the time of Henry VIII; it was the first time that a unitary power had full control over the capital's sanitation facilities. The Building Act 1844 had ensured that all new buildings had to be connected to a sewer, not a cesspool, and the commission set about connecting cesspools to sewers, or removing them altogether. Because of the fear that the miasma from the sewers would cause the spread of disease, Chadwick, and his successor, Dr John Simon, ensured that the sewers were regularly flushed through, a policy that resulted in more sewage being discharged into the Thames.

In August 1849 the MCS appointed Joseph Bazalgette to the position of assistant surveyor. He was a 30-year-old engineer who had been working as a consultant engineer in the railway industry until overwork had brought about a serious breakdown in his health; his appointment to the commission was his first position on his return to work. Working under the Chief Engineer, Frank Foster, the pair developed a more systematic plan for the city's sewers, although the stress was too much for Foster and he died in 1852; Bazalgette was promoted into Foster's position, and continued refining and developing the plans. The Metropolis Management Act 1855 replaced the commission with the Metropolitan Board of Works (MBW), which took control of the sewers. Bazalgette had to apply for the position of Chief Engineer against eight others; his application for the role—which was successful—was supported by Robert Stephenson, MP, the co-designer of the Rocket with his father; the millwright and civil engineer William Cubitt, who had designed and built two of Britain's railways systems; and the mechanical and civil engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

By June 1856 Bazalgette completed his definitive plans, which planned for small, local sewers about 3 feet (0.9 m) in diameter would feed into larger and larger sewers until they drained into main outflow pipes 11 feet (3.4 m) high. A Northern and Southern Outfall Sewer was planned to manage the waste for each side of the river. London was mapped into high-, middle- and low-level areas, with a main sewer servicing each; a series of pumping stations were planned to remove the waste towards the east of the city. Bazalgette's plan was based on that of Foster, but was larger in scale, and allowed for more of a rise in population than Foster's – from 3 to 4.5 million. Bazalgette submitted his plans to Sir Benjamin Hall, the First Commissioner of Works. Hall had reservations about the outfalls—the discharge points of a waste outlets into other bodies of water—from the sewers, which he said was still within the bounds of the capital, and was therefore unacceptable. During the course of the ongoing discussions Bazalgette refined and modified his plans, in line with Hall's demands. In December 1856 Hall submitted the plans to a group of three consultant engineers, Captain Douglas Strutt Galton of the Royal Engineers, James Simpson, an engineer with two water companies, and Thomas Blackwood, the chief engineer on the Kennet and Avon Canal. The trio reported back to Hall in July 1857 with proposed changes to the positions of the outfall, which he passed on to the MWB in October. The new proposed discharge points were to be open sewers, running 15 miles (24 km) beyond the positions proposed by the Board; their cost of their plans was to be over £5.4 million, considerably more than the maximum estimate of Bazalgette's plan, which was £2.4 million. In February 1858 a general election saw the fall of Lord Palmerston's first government, which was replaced by Lord Derby's second ministry; Lord John Manners replaced Hall, and Benjamin Disraeli was appointed Leader of the House of Commons and Chancellor of the Exchequer.

June to August 1858

Punch magazine's view of Father Thames, July 1858 A workman uses lime to disguise the smell of the Thames, reflecting the actions of Parliament, who had dipped their curtains in lime chloride.

A workman uses lime to disguise the smell of the Thames, reflecting the actions of Parliament, who had dipped their curtains in lime chloride. "Father Thames introducing his offspring to the fair city of London"; the children are representative of diphtheria, scrofula and cholera.

"Father Thames introducing his offspring to the fair city of London"; the children are representative of diphtheria, scrofula and cholera.

In June 1958 the temperatures in the shade in London averaged in the mid-30s °C—rising to 48 °C in the sun. Combined with an extended spell of dry weather, the levels of the Thames dropped and raw effluent from the sewers remained on the banks of the river. By June the stench from the river had become so bad that business in Parliament was affected, and the curtains on the river side of the building were soaked in lime chloride to overcome the smell. The measure was not successful, and discussions were held about possibly moving the business of government to Oxford or St Albans. The disruption to the work of the legislators led to questions being raised in the House of Commons; Hansard recorded that the MP John Leith said to Manners that "It was a notorious fact that hon. Gentlemen sitting in the Committee Rooms and in the Library were utterly unable to remain there in consequence of the stench which arose from the river; and he wished to know if the noble Lord has taken any measures for mitigating the effluvium and discontinuing the nuisance". Manners replied that the Thames was not under his remit. Four days later a second MP said to Manners that "By a perverse ingenuity, one of the noblest of rivers has been changed into a cesspool, and I wish to ask whether Her Majesty's Government intend to take any steps to remedy the evil?"; Manners pointed out "that Her Majesty's Government have nothing whatever to do with the state of the Thames". The satirical magazine Punch commented that "The one absorbing topic in both Houses of Parliament ... was the Conspiracy to Poison question. Of the guilt of that old offender, Father Thames, there was the most ample evidence".

On 15 June Disraeli tabled the Metropolis Local Management Amendment Bill, a proposed amendment to the 1855 Act; in the opening debate he called the Thames "a Stygian pool, reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors". The Bill put the responsibility to clear up the Thames on the MWB, and stated that "as far as may be possible" the sewerage outlets should not be within the boundaries of London; it also allowed the Board to borrow £3 million, which was to be repaid from a 3 pence levy on all London households for the next forty years. The terms favoured Bazalgette's original 1856 plan, and overcame Hall's objection to it. The leading article in The Times observed that "Parliament was all but compelled to legislate upon the great London nuisance by the force of sheer stench" The bill was debated in late July and was passed into law on 2 August.

Construction

Bazalgette's plans for the 1,100 miles (1,800 km) additional street sewers (collecting both effluent and rainwater) which would feed into 82 miles (132 km) of main interconnecting sewers, were put out to tender between 1859 and 1865. 400 draftsmen worked on the detailed drawings to show the plans and sectional views for what were twenty-seven contracts to cover the first phase of the building process. There were several engineering challenges to be overcome, particularly the fact that parts of London—including the area around Lambeth and Pimlico—lie below the high-water mark. Bazalgette's plan for the low-level areas was to lift the sewerage from low-lying sewers at key points into the mid- and high-level sewers, which would then drain with the aid of gravity, out towards the eastern outfalls at a rate of 2 feet per mile.

Bazalgette was a proponent of the use of Portland cement, a material stronger than standard cement, but with a weakness when over-heated. To overcome the issue he instituted a quality control system to test batches of cement, that is described by the historian Stephen Halliday as both "elaborate" and "draconian" The results were fed back to the manufacturers, who altered their production processes to further improve the product. One of the cement manufacturers commented that the MWB were the first public body to use such testing processes. Progress of Bazalgette's works was reported positively in the press; Paul Dobraszczyk, the architectural historian, describes the coverage as presenting many of the workers "in a positive, even heroic, light", and in 1861 The Observer described the works as "the most expensive and wonderful work of modern times". The works were so expensive that in July 1863 an additional £1.2 million was raised to cover the cost of the work.

Southern drainage system

The octagon room at Crossness Pumping Station, Belvedere, Kent

The octagon room at Crossness Pumping Station, Belvedere, Kent Edward, Prince of Wales, opening the Crossness works, 1865

Edward, Prince of Wales, opening the Crossness works, 1865

The southern system, across the less populated suburbs of London was the smaller and easier part of the system to build. Three main sewers running from Putney, Wandsworth and Norwood until they linked together in Deptford, where a pumping station lifted the effluent up 21 feet to run into the main outflow sewer which ran down to the Crossness Pumping Station on the Erith Marshes, where it discharged in to the Thames at high tide. The newly built Crossness Pumping Station was designed by Bazalgette and a consultant engineer, Charles Henry Driver, a proponent of the use of cast iron as a building material. The building was in a Romanesque style and the interior contains what English Heritage describe as "important cast iron architectural treatment"; the power for pumping the large amount of sewage was provided by four massive beam engines manufactured by James Watt and Co.

The station was opened in April 1865 by the Prince of Wales—the future King Edward VII, who started officially started the engines; the four beam engines were named Victoria, Prince Consort, Albert Edward and Alexandra. The ceremony, which was attended by other members of royalty, MPs, the Lord Mayor of London and the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, was followed by a dinner for 500 within the building. The ceremony marked the completion of construction of the Southern Outfall Sewers, and the beginning of their operation.

With the successful completion of the Southern outflow, one of the board members of the MBW, an MP named Miller, proposed a bonus for Bazalgette. The board agreed, and were prepared to pay the engineer £6,000—three times his annual salary—with an additional £4,000 to be shared among his three assistants. Although the idea was subsequently dropped following criticism, Halliday observes that the large amounts discussed "at a time when parsimony was the dominant characteristic of public expenditure is a firm indication of the depth of public interest and approval that appears to have characterised the work."

Northern drainage system

Bazalgette awarded two of the tenders to George Furness, and a further five to William Webster, both experienced contractors. He selected the companies on the basis of reliability, rather than the lowest cost, although some of the tender holders—such as William Rowe, who held the contract for the northern mid-level sewers—went bankrupt shortly after he was granted the tender in February 1860. After Bazalgette was forced to find another contractor to take Rowe's place, the MBW began selecting larger, more financially stable contractors. Furness, an experienced contractor who had developed his business in the expansion of the railways, had won the contract for the main Northern Outfall Sewer. Work began on the system on 31 January 1859, but encountered numerous problems in construction, including a labourer's strike in 1859–60. It was the more populous side of the river, housing two-thirds of London's population, and the works had to work through congested streets and overcome such urban hurdles as canals, bridges and railway lines.

The high-level sewer—the most northern of the works—ran from Hampstead Heath to Stoke Newington and across Victoria Park, where it joined with the eastern end of the mid-level sewer. The beginning of the mid-level sewer, the Eastern end, began in Bayswater and runs along Oxford Street, through Clerkenwell, Bethnal Green, before the join. This combined main sewer ran to the Abbey Mills Pumping Station in Stratford, where it was joined by the eastern end of the low-level sewer. The pumps at Abbey Mills lifted the effluent from the low-level sewer up 36 feet (11 m) into the main sewer. This main sewer ran 5 miles (8 km)—along what is now known as the Greenway—to the outfall at Beckton.

Thames Embankment under construction in 1865

Thames Embankment under construction in 1865 A cross section of the Thames Embankment, showing the sewers running next to the river side.

A cross section of the Thames Embankment, showing the sewers running next to the river side.

Like the Crossness Pumping Station, Abbey Mills was a joint design by Bazalgette and Driver. Above the centre of the engine-house was an ornate dome that gives the building a "superficial resemblance ... to a Byzantine church". The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner, in his Buildings of England, thought the building showed "exciting architecture applied to the most foul purposes"; he went on to describe it as "an unorthodox mix, vaguely Italian Gothic in style but with tiers of Byzantine windows and a central octagonal lantern that adds a gracious Russian flavour".

To provide the drainage for the low-level sewers, in February 1864 Bazalgette began building three Embankments along the shores of the Thames. On the northern side are the Victoria, which runs from Westminster to Blackfriars Bridge, and the Chelsea, running from Millbank to the Cadogan Pier at Chelsea. The southern side contains the Albert Embankment, from the Lambeth end of Westminster Bridge to Vauxhall. He ran the sewers along the banks of the Thames, building up walls on the foreshore, running the sewer pipes inside and infilling around them. The works claimed over 52 acres (21 ha) of land from the Thames; the Victoria Embankment relieved the congestion on the pre-existing routes between Westminster and City. The cost of the building the Embankments was estimated at £1.71 million, of which £450,000 was used purchasing the necessary river-front properties, which tended to be light industrial. The Embankment project was seen as being nationally significant and, with the queen unable to attend because of illness, the Victoria Embankment was opened by the Prince of Wales in July 1870. The Albert Embankment had been completed in November 1869, while the Chelsea Embankment was opened in July 1874.

Bazalgette considered the Embankment project "one of the most difficult and intricate things the ... have had to do", and shortly after the Chelsea Embankment was opened, Bazalgette was knighted. In 1875 the work on the western drainage was completed, and the system became operational. The building work had required 318 million bricks and 880,000 cubic yards (670,000 m) of concrete and mortar and the final cost was approximately £6.5 million.

Legacy

In 1866 there had been a further cholera outbreak in London that claimed 5,596 lives, although it was confined to an area of the East End between Aldgate and Bow. At the time this was the part of London which had not been connected to Bazalgette's system, and 93 per cent of the fatalities occurred within the region. The fault lay with the East London Water Company, who discharged their sewage half a mile downstream from their reservoir: the sewage was being carried upstream into the reservoir on the incoming tide, contaminating the area's drinking water. The outbreak, and the diagnosis of its causes, led to the acceptance that cholera was water-borne, not transmitted by miasma. The Lancet, relating details of the investigation into the incident by Dr William Farr, stated that his report "will render irresistible the conclusions at which he has arrived in regard to the influence of the water-supply in causation of the epidemic." It was the last outbreak of the disease in the capital.

In 1878 a Thames pleasure-steamer, the SS Princess Alice, collided with the collier Bywell Castle and sank. Over 650 people died. The accident took place near the outfalls and questions were raised in the British press over whether the sewage was responsible for some of the deaths. In the 1880s further fear over possible health concerns because of the outfalls led to the MBW purifying sewage at Crossness and Beckton, rather than dumping the untreated waste into the river, and a series of six sludge boats were ordered to ship effluent the North Sea for dumping. The first boat commissioned was named the SS Bazalgette, which remained in service until December 1998, when the dumping stopped, and an incinerator was used to dispose of the waste. The sewers were expanded in the late 19th century and again in the early 20th century. The drainage network is, as of 2015, managed by Thames Water, and is used by up to 8 million people a day. The company states that "the system is struggling to cope with the demands of 21st century London".

Crossness Pumping Station remained in use until the mid-1950s when it was replaced. The engines were too large to remove and were left in situ, although they fell into a state of disrepair. The station itself became a grade 1 listed building with English Heritage in June 1970. The building and its engines are, as of 2015, under restoration by the Crossness Engines Trust. The president of the trust is the British television producer Peter Bazalgette, who is the great-great-grandson of Joseph. As of 2015 part of the Abbey Mill facility continue to operate as a sewage pumping station. The building's large double chimneys were removed during the Second World War following fears that they could be used by the Luftwaffe for navigation.

The provision of an integrated and fully functioning sewer system for the capital, and the associated drop in Cholera cases has led one historian to state that Bazalgette "probably did more good, and saved more lives, than any single Victorian official". Bazalgette continued to work at the MWB until 1889, during which time he redesigned three of London's bridges: Putney in 1886, Hammersmith in 1887 and Battersea in 1890. He was appointed as president of the Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) in 1884, and in 1901 a monument commemorating his life was opened on the Victoria Embankment. When he died in March 1891, his obituarist in The Illustrated London News wrote that Bazalgette's "two great titles to fame are that he beautified London and drained it", while Sir John Coode, the president of ICE at the time, said that Bazalgette's work "will ever remain as monuments to his skill and professional ability". The obituarist for The Times opined that "when the New Zealander comes to London a thousand years hence ... the magnificent solidity and the faultless symmetry of the great granite blocks which form the wall of the Thames-embankment will still remain. ... the great sewer that runs beneath Londoners ... has added some 20 years to their chance of life". In 2011 the historian Peter Ackroyd, in his history of subterranean London, considers that because of his work, particularly the building of the Victoria and Albert Embankments, "with Nash and Wren, Bazalgette enters the pantheon of London heroes."

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- The Fleet and Walbrook rivers, along with numerous others, still exist under modern-day London.

- Chadwick—a barrister by training—was a social reformer keen to improve sanitary conditions and public health; in 1842 he had published the Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, a best-selling report. In 1843 he served on a royal commission on the health of towns, before service on a second royal commission in 1847, which resulted in the formation of the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers.

- The authority overseeing the works in the City of London remained separate.

- Hall, an imposingly tall man, oversaw the rebuilding of much of the Palace of Westminster, including the parliamentary clock in St Stephen's Tower (now named Elizabeth Tower); the principal bell of the tower—Big Ben—was named after him.

- £5.4 million in 1857 equates to a little over £450 million in 2015; £2.4 million equates to a little over £200 million.

- £6,000 in 1865 equates to £500,000 in 2015.

- £1.71 million in 1859 equates to £149.5 million in 2015; £450,000 equates to a little over £39.3 million.

- £6.5 million in 1875 equates to approximately £535 million in 2015.

References

- Talling 2011, pp. 40 & 42.

- Ackroyd 2011, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Dobraszczyk 2014, pp. 8–9.

- Owen 1982, p. 47.

- Faraday, Michael (9 July 1855). "The State of the Thames". The Times. p. 8.

- ^ Flanders 2012, p. 224.

- Hibbert et al. 2011, p. 248.

- Halliday 2001, p. 1469.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 9.

- Ryan 2008, p. 11.

- ^ Snow 2004.

- Clayton 2010, p. 64.

- ^ Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 15.

- Mandler 2004.

- Owen 1982, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Trench & Hillman 1989, p. 66.

- ^ Smith 2004.

- "Joseph Bazalgette". The History Channel. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- Halliday 2013, p. 10.

- Trench & Hillman 1989, p. 72.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, pp. 20–22.

- De Maré & Doré 1973, p. 47.

- Halliday 2013, p. 59.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 68–70.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 71 & 73.

- "Health of London During the Week". London Standard. 10 June 1858. p. 2.

- "Parliament and the Thames". UK Parliament. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- "State of the Thames—Question". Hansard. 150: col. 1921. 11 June 1858.

- "State of the Thames—Question". Hansard. 150: cols. 2113–34. 15 June 1858.

- "Punch's Essence of Parliament". Punch: 3. 3 July 1858.

- "First Reading". Hansard. 151: cols. 1508–40. 15 June 1858.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 73–74.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 32.

- "Leading article". The Times. 18 June 1858. p. 9.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 25.

- ^ Halliday 2011, p. 208.

- Halliday 2013, p. 79.

- De Maré & Doré 1973, pp. 47–48.

- Halliday 2013, pp. xiii & 10.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 34.

- "The Metropolitan Great Drainage Works". The Observer. London. 15 April 1861. p. 2.

- Owen 1982, p. 59.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 83–84.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 44.

- ^ "Crossness Pumping Station". English Heritage. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Crossness Pumping Station". The Crossness Engines Trust. Retrieved 16 February 2015.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 97–98.

- Picard 2005, pp. 9–10.

- Halliday 2013, p. xiii.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 95–97.

- Dobraszczyk 2008, pp. 576 & 578.

- ^ Halliday 2011, p. 209.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 27.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 81–82.

- Dobraszczyk 2006, p. 236.

- Cherry, O'Brien & Pevsner 2005, pp. 229–30.

- Thornbury 1878, p. 322.

- Hudson, Roger (March 2012). "Taming the Thames". History Today. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- Picard 2005, p. 27.

- ^ Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 31.

- Thornbury 1878, pp. 325–26.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 157–59.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 155 & 162.

- De Maré & Doré 1973, pp. 209–10.

- Halliday 2013, p. 163.

- De Maré & Doré 1973, p. 213.

- ^ Trench & Hillman 1989, p. 76.

- "Sir Joseph Bazalgette and London's Sewers". The History Channel. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- "Sir Joseph Bazalgette, CB". Punch. 1 December 1883. p. 262.

- Halliday 2013, p. 124.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 139–40.

- Halliday 2013, p. 103.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 55.

- Halliday 2013, pp. 106–07.

- "London's Victorian sewer system". Thames Water. 6 August 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Emmerson 2009, p. 18.

- "Smells Like Thames Sewage". BBC.co.uk. 5 June 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- "Thames Water gives public a glimpse into the historical world of water". Thames Water. 21 August 2012. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

- Dobraszczyk 2014, p. 62.

- Clayton 2010, p. 73.

- Halliday 2013, p. 3.

- "Personal". The Illustrated London News. 21 March 1891. p. 370.

- "Death of Sir Joseph Bazalgette". The Times. 16 March 1891. p. 4.

- Ackroyd 2011, p. 80.

Sources

- Ackroyd, Peter (2011). London Under. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0-7011-6991-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cherry, Bridget; O'Brien, Charles; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2005). London: East. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10701-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clayton, Antony (2010). Subterranean City: Beneath the streets of London. Whitstable, Kent: Historical Publications. ISBN 978-1-9052-8632-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - De Maré, Eric; Doré, Gustave (1973). Victorian London Revealed: Gustave Doré's Metropolis. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-1413-9084-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobraszczyk, Paul (2006). "Historicizing Iron: Charles Driver and the Abbey Mills Pumping Station (1865-68)". Architectural History. 49: 223–56. JSTOR 40033824.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobraszczyk, Paul (July 2008). "Image and Audience: Contractual Representation and London's Main Drainage System". Technology and Culture. 49 (3): 568–98. JSTOR 40061428.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dobraszczyk, Paul (2014). London's Sewers. Oxford: Shire Books. ISBN 978-0-7478-1431-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Emmerson, Andrew (2009). Subterranean London. Oxford: Shire Publications. ISBN 978-0-7478-0740-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Flanders, Judith (2012). The Victorian City: Everyday Life in Dickens' London. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-8578-9881-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halliday, Stephen (22–29 December 2001). "Death and Miasma in Victorian London: An Obstinate Belief". BMJ. 323 (7327). London. JSTOR 25468628.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halliday, Stephen (2011). The Great Filth. Stroud: History Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7524-6175-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Halliday, Stephen (2013). The Great Stink of London: Sir Joseph Bazalgette and the Cleansing of the Victorian Metropolis. Stroud: History Press Limited. ISBN 978-0-7509-2580-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hibbert, Christopher; Weinreb, Ben; Keay, John; Keay, Julia (2011). The London Encyclopaedia (3rd ed.). London: Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-73878-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mandler, Peter (2004). "Chadwick, Sir Edwin (1800–1890)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5013. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Owen, David Edward (1982). The Government of Victorian London, 1855–1889: The Metropolitan Board of Works, the Vestries, and the City Corporation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-35885-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Picard, Liza (2005). Victorian London: The Life of a City 1840–1870. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-2978-4733-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ryan, Jeffrey R. (2008). Pandemic Influenza: Emergency Planning and Community Preparedness. Boco Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-6088-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Smith, Denis (2004). "Bazalgette, Sir Joseph William (1819–1891)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/1787. Retrieved 26 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Snow, Stephanie J. (2004). "Snow, John (1813–1858)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25979. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) (subscription or UK public library membership required) - Talling, Paul (2011). London's Lost Rivers. London: Random House Books. ISBN 978-1-84794-597-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thornbury, Walter (1878). Old and New London. Vol. 3. London: Cassell, Petter & Galpin. OCLC 174260850.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Trench, Richard; Hillman, Ellis (1989). London Under London. London: J. Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-4617-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- The Great Stink Thames information and history of the period

- The Great Stink at The Crossness Engines Trust