| Revision as of 05:47, 12 June 2016 editPermstrump (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,156 edits Undid revision 724892197 by Altenmann (talk) Please do not remove sourced material. Take it to the talkpage.← Previous edit | Revision as of 05:49, 12 June 2016 edit undoAltenmann (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers219,478 edits Reverted 1 edit by Permstrump (talk): Please show me a single wikipedia article where in the first sentence is "so called". (TW)Next edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| A '''Jewish nose''' |

A '''Jewish nose''' <ref name=Patai/><ref name="prem"/> is a large ], generally ] or hooked, but more specifically defined as one with a convex nasal bridge together with downward turn of the tip of the nose. Though found with the same frequency among non-Jewish Mediterranean and Near Eastern peoples,<ref name=Patai>{{cite|first=Raphael|last=Patai|url=https://books.google.it/books?id=Xt7f6WBEP0EC&pg=PA208|title=The Myth of the Jewish Race|publisher=Wayne University Press|year=1989|page=208}}</ref> it was singled out as a hostile caricature of Jews alone in mid-13th century in Europe, and has since become a defining element of ].<ref name="prem">{{cite|first=Beth|last=Preminger|url=http://jama.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1844290|title=The "Jewish Nose" and Plastic Surgery: Origins and Implications|journal=Journal of the American Medical Association|year=2001|volume=286|issue=17|page=2161|doi=10.1001/jama.286.17.2161-JMS1107-5-1}}</ref><ref name="JE">{{cite|chapter-url=http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/11598-nose|chapter=Nose|title=Jewish Encyclopedia|year=1906|first1=Joseph|last1=Jacobs|first2=Maurice|last2=Fishberg}}</ref> The Jewish has nose appeared often in antisemitic caricatures throughout the years, but has also been adopted by many Jews as a part of their ethnic identity. | ||

| Attitudes of Jews and others towards the Jewish nose has changed since the 1950s when many Jews considered it a type of deformity. In fact, this nose shape is not characteristic of Jews—only about a quarter of Jews have this nose shape, which is the same as its presence in the general population. | Attitudes of Jews and others towards the Jewish nose has changed since the 1950s when many Jews considered it a type of deformity. In fact, this nose shape is not characteristic of Jews—only about a quarter of Jews have this nose shape, which is the same as its presence in the general population. | ||

Revision as of 05:49, 12 June 2016

A Jewish nose is a large nose, generally aquiline or hooked, but more specifically defined as one with a convex nasal bridge together with downward turn of the tip of the nose. Though found with the same frequency among non-Jewish Mediterranean and Near Eastern peoples, it was singled out as a hostile caricature of Jews alone in mid-13th century in Europe, and has since become a defining element of racial stereotypes of the Jews. The Jewish has nose appeared often in antisemitic caricatures throughout the years, but has also been adopted by many Jews as a part of their ethnic identity.

Attitudes of Jews and others towards the Jewish nose has changed since the 1950s when many Jews considered it a type of deformity. In fact, this nose shape is not characteristic of Jews—only about a quarter of Jews have this nose shape, which is the same as its presence in the general population.

Morphology and genealogy

There is no real agreement about what shape the Jewish nose is. Robert Knox, an 18th century anatomist, described it as "a large, massive, club-shaped, hooked nose." Another anatomist, Jerome Webster, described it in 1914 as having "a very slight hump, somewhat broad near the tip and the tip bends down." In his essay "Notes on Noses" from 1848, George Jabet offers quite a different description: "very convex, and preserves its convexity like a bow, throughout the whole length from the eyes to the tip. It is thin and sharp."

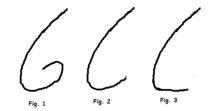

Jewish folklorist Joseph Jacobs, in the mid-19th century, suggested that the main characteristic of the Jewish nose was large nostrils. "A curious experiment illustrates this importance of the nostril toward making the Jewish expression. Artists tell us that the best way to make a caricature of the Jewish nose is to write a figure 6 with a long tail (Fig. 1); now remove the turn of the twist as in Figure 2, and much of the Jewishness disappears; it vanishes entirely when we draw the continuation horizontally as in Figure 3. We may conclude, then, as regards the Jewish nose, that it is more the Jewish nostril than the nose itself which goes to form the characteristic Jewish expression."

Statistics cited in the article "Nose" from 1901–1905 Jewish Encyclopedia demonstrate that, contrary to the stereotype, the "hooked" nose in fact belongs to the minority (20–30%) of the Jews, with vast majority having straight noses. Some years later, in 1914, Maurice Fishberg examined the noses of 4,000 Jews in New York and found that only 14% could be described as either aquiline or hooked. It appeared to be no more common among Jews than among Mediterranean people generally. Felix von Luschan suggested that arched noses in Jews is not a Semitic trait, but is a consequence of the intermixture with the Hittites in Asia Minor, noting that other races with Hittite blood, such as the Armenians, have similar noses. The same theory was held by Houston Stewart Chamberlain.

History

Art historian Sarah Lipton traces the association of the hooked nose with Jews to the 13th century. Prior to that time, representations of Jews in art and iconography showed no specific facial features. "By the later thirteenth century, however, a move toward realism in art and an increased interest in physiognomy spurred artists to devise visual signs of ethnicity. The range of features assigned to Jews consolidated into one fairly narrowly construed, simultaneously grotesque and naturalistic face, and the hook-nosed, pointy-bearded Jewish caricature was born."

While the hooked nose became associated with Jews in the 13th century, the Jewish nose stereotype only became firmly established in the European imagination several centuries later. One early literary use of it is Francisco de Quevedo's A un hombre de gran nariz (To a man with a big nose) written against his rival in poetry, Luis de Góngora. The point of his sonnet was to mock his rival by suggesting his large nose was proof he was, not a 'pure blooded Spaniard', but the descendent of conversos, Jews who had converted to Catholicism to avoid expulsion.In particular the reference to una nariz sayón y escriba(the nose of a hangman and scribe) associates such a nose maliciously with the Pharisees and the Scribes responsible for Christ's death according to the New Testament.

"The so-called Jewish nose, bent at the top, jutting hawk-like from the face, existed already as a caricature in the sixteenth century... It became firmly established as a so-called Jewish trademark only by the mid-eighteenth century, however..."

The hooked nose became a key feature in Nazi antisemitic propaganda. “One can most easily tell a Jew by his nose," wrote Nazi propagandist Julius Streicher in a children's story. "The Jewish nose is bent at its point. It looks like the number six. We call it the 'Jewish six.' Many Gentiles also have bent noses. But their noses bend upwards, not downwards. Such a nose is a hook nose or an eagle nose. It is not at all like a Jewish nose.”

According to writer Naomi Zeveloff, "in prewar Berlin, where the modern nose job was first developed, Jews sought the procedure to hide their ethnic identity." The inventor of rhinoplasty, Jacques Joseph, had "a large Jewish clientele seeking nose jobs that would allow them to pass as gentiles in Berlin", wrote Zeveloff.

But this negative view of the Jewish nose was not shared by all Jews; Jewish Kabbalistic texts consider a large nose as a sign of character. In his book "The Secrets of the Face" (חכמת הפרצוף), Kabbalistic Rabbi Aharon Leib Biska wrote in 1888 that Jews have "the eagle's nose". "A nose that is curved down... with a small hump in the middle attests to a character that seeks to discover the secrets of wisdom, who shall govern fairly, be merciful by nature, joyful, wise and insightful."

Among those seeking surgery to make their noses smaller were many American Jewish film actresses of the 1920s to 1950s. "Changing one's name is to Jewish males what fixing one's nose is to Jewish females, a way of passing," writes film historian Patricia Erens. One of the actresses to undergo surgery was Fanny Brice, inspiring commentator Dorothy Parker to comment that she "cut off her nose to spite her race." According to Erens, this fashion ended with Barbra Streisand, whose nose is a signature feature. "Unlike characters in the films of the 1930s and 1940s, she is not a Jew in name only, and certainly she is the first major female star in the history of motion pictures to leave her name and her nose intact and to command major roles as a Jewish actress." Streisand told Playboy Magazine in 1977, "When I was young, everyone would say, 'You gonna have your nose done?' It was like a fad, all the Jewish girls having their noses done every week at Erasmus Hall High School, taking perfectly good noses and whittling them down to nothing. The first thing someone would have done would be to cut my bump off. But I love my bump, I wouldn't cut my bump off."

"As Jews assimilated into the American mainstream in the 1950s and ’60s, nose jobs became a rite of passage for Jewish teens who wanted a more Aryan look," wrote Zeveloff. By 2014, the number of rhinoplasty operations had declined by 44 percent, and "in many cases the procedure has little bearing on... religious identity."

References

- ^ Patai, Raphael (1989), The Myth of the Jewish Race, Wayne University Press, p. 208

- ^ Preminger, Beth (2001), "The "Jewish Nose" and Plastic Surgery: Origins and Implications", Journal of the American Medical Association, 286 (17): 2161, doi:10.1001/jama.286.17.2161-JMS1107-5-1

- ^ Jacobs, Joseph; Fishberg, Maurice (1906), "Nose", Jewish Encyclopedia

- Gilman, Sander (1991). The Jew's Body. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415904599.

- Joseph Jacobs, "On the Racial Characteristics of Modern Jews", Journal of the Anthropological Institute, 1886, xv. 23–62; as cited in Jewish Encyclopedia.

- Steve Silbiger, The Jewish Phenomenon: Seven Keys to the Enduring Wealth of a People, Taylor Trade Publications, 2000 p.13.

- Chamberlain, Houston Stewart. The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. p. 394

- Lipton, Sara. "The Invention of the Jewish Nose". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- Christina H. Lee,The anxiety of sameness in early modern Spain, Manchester University Press 2015 pp.134-135ff

- Jorge Salavert Pinedo, '"To a man with a big nose": a new translation,'

- Kroha, Lucienne (2014). The Drama of the Assimilated Jew: Giorgio Bassani's Romanzo di Ferrara. University of Toronto Press. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-4426-4616-2.

- Streicher, Julius (c. 1939). "How to Tell a Jew". research.calvin.edu. Translated by Randall Bytwerk, 1999. from Der Giftpilz, an anti-Semitic children’s book published by Julius Streicher, the publisher of Der Stürmer. Translated for the Calvin Archive of Nazi Propaganda. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- ^ Zeveloff, Naomi. "How the All-American Nose Job Got a Makeover". The Forward. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- Biska, Rabbi Aharon Leib (1888). Secrets of the Face. Warsaw, Poland. p. 18.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Erens, Patricia (1984). The Jew in American Cinema. Indiana University Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0253204936.

- Miller, Nina (1999). Making Love Modern. Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 0-19-511604-6.

- Erens, p. 269

- "Barbra Streisand Archives | Her Profile, Nose". barbra-archives.com. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

Further reading

- Melvin Konner, The Jewish Body, 2009