| Revision as of 07:40, 17 November 2006 view sourceAAA765 (talk | contribs)22,145 edits →Hadith← Previous edit | Revision as of 07:58, 17 November 2006 view source Truthspreader (talk | contribs)3,002 edits →HadithNext edit → | ||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

| Western Academics are much more critical towards Hadith collections, contrasting with their view about the reliability of the ]. ] states that "the collection and scrutiny of Hadiths didn't take place until several generations" after Muhammad's death and that "during that period the opportunities and motives for falsification were almost unlimited." In addition to the problem of oral transmission for over a hundred years, there existed motives for deliberate distortion. The Muslims themselves at an early date realized that many Hadiths were fabricated and thus developed a whole science of criticism to distinguish between genuine Hadiths and pious or impious frauds." However modern critics have pointed out many defects in their approach (e.g. the easiness of forging a chain of authorities as a tradition, and furthremore rejection of some relators imlpies the victory of one thought over the others). <ref> ''The Arabs in History'', by ], p. 33-34 </ref> <ref> F.E. Peters, The Quest for Historical Muhammad, International Journal of Middle East Studies (1991) p.291-315 </ref> | Western Academics are much more critical towards Hadith collections, contrasting with their view about the reliability of the ]. ] states that "the collection and scrutiny of Hadiths didn't take place until several generations" after Muhammad's death and that "during that period the opportunities and motives for falsification were almost unlimited." In addition to the problem of oral transmission for over a hundred years, there existed motives for deliberate distortion. The Muslims themselves at an early date realized that many Hadiths were fabricated and thus developed a whole science of criticism to distinguish between genuine Hadiths and pious or impious frauds." However modern critics have pointed out many defects in their approach (e.g. the easiness of forging a chain of authorities as a tradition, and furthremore rejection of some relators imlpies the victory of one thought over the others). <ref> ''The Arabs in History'', by ], p. 33-34 </ref> <ref> F.E. Peters, The Quest for Historical Muhammad, International Journal of Middle East Studies (1991) p.291-315 </ref> | ||

| The overwhelming majority of Muslims consider hadith to be essential supplements to and clarifications of the ], Islam's holy book. In Islamic jurisprudence, the Qur'an contains many rules for the behavior expected of Muslims. However, there are many matters of concern, both religious and practical, on which there are no specific Qur'anic rules. Muslims believe that they can look at the way of life, or '']'', of Muhammad and his companions to discover what to imitate and what to avoid. Muslim scholars also find it useful to know how Muhammad or his companions explained the revelations, or upon what occasion Muhammad received them. Sometimes this will clarify a passage that otherwise seems obscure. Hadith are a source for Islamic history and biography. For the vast majority of devout Muslims, authentic hadith are also a source of religious inspiration. However, some contemporary Muslims argue that the ] is sufficient. | The overwhelming majority of Muslims consider hadith to be essential supplements to and clarifications of the ],{{dubious}} Islam's holy book. In Islamic jurisprudence, the Qur'an contains many rules for the behavior expected of Muslims. However, there are many matters of concern, both religious and practical, on which there are no specific Qur'anic rules. Muslims believe that they can look at the way of life, or '']'', of Muhammad and his companions to discover what to imitate and what to avoid. Muslim scholars also find it useful to know how Muhammad or his companions explained the revelations, or upon what occasion Muhammad received them. Sometimes this will clarify a passage that otherwise seems obscure. Hadith are a source for Islamic history and biography. For the vast majority of devout Muslims, authentic hadith are also a source of religious inspiration. However, some contemporary Muslims argue that the ] is sufficient. | ||

| ==Five Pillars of Islam== | ==Five Pillars of Islam== | ||

Revision as of 07:58, 17 November 2006

| Editing of this article by new or unregistered users is currently disabled. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. If you cannot edit this article and you wish to make a change, you can submit an edit request, discuss changes on the talk page, request unprotection, log in, or create an account. |

Islam (Arabic: الإسلام; al-'islām) is a monotheistic religion based upon the Qur'an, its principal scripture. Islam's followers, known as Muslims, believe God (Arabic: ]) revealed the Qur'an to Muhammad and that Muhammad is God's final prophet (see: Prophets of Islam). The majority of Muslims see the actions and teachings of Muhammad, as related in the Sunnah and Hadith, to be indispensable tools for interpreting the Qur'an.

Like Judaism and Christianity, Islam is an Abrahamic religion. There are estimated to be 1.4 billion adherents, making Islam the second-largest religion in the world.

Today, Muslims may be found throughout the world, particularly in the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia. The majority of Muslims are not Arabs; only 20 percent of Muslims originate from Arab countries. Islam is the second largest religion in the United Kingdom, and many other European countries, including France, which has the largest Muslim population in Western Europe.

Beliefs

Main article: AqidahMuslims believe that God revealed a message to humanity through Muhammad (c. 570–July 6, 632) via the angel Gabriel. Muhammad is considered to have been God's final prophet, based on the Qur'anic phrase "Seal of the Prophets" and sayings of Muhammad himself. Muslims assert that their holy book, the Qur'an, is flawless, immutable, and the final revelation of God to humanity, and that its teachings will be valid until the day of the Resurrection.

Muslims hold that the message of Islam, that is submission to the one God's will, is the same as the message preached by all the messengers sent by God to humanity since Adam. Therefore Muslims believe Islam is not a new religion with a new scripture. "Far from being the youngest of the major monotheistic world religions, from a Muslim point of view Islam is the oldest because it represents the original as well as the final revelation of the God to Abraham, Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad" (See ) . The Qur'an, used by all sects of the Muslim faith, codifies the direct words of God. Islamic texts depict Judaism and Christianity as prophetic successor traditions to the teachings of Abraham. The Qur'an calls Jews and Christians "people of the Book," and distinguishes them from "polytheists." In order to reconcile the often radical disagreements regarding events and interpretation that exist between the earlier writers and the Qur'an, Muslims believe that Jews and Christians forgot or distorted the word of God after it was revealed to them (The majority of early scholars as well as some modern scholars believe it was just distortion in the interpretation given to the Bible while others believe in textual distortion as well. ). Specifically, Muslims believe that the Jews have changed the Tawrat (Torah), and that Christians have changed the Injil (Gospels) by altering words in meaning, form and placement in their respective holy texts.

Oneness of God

Main articles: Allah, God, Islamic concept of God, and Tawhīd

The fundamental concept in Islam is the Oneness of God or tawhīd: monotheism which is absolute, not relative or pluralistic. The Oneness of God is the first pillar of Islam's five pillars which is also called the "Shahādatān" (The two testimonies). By declaring the two testimonies one attests to the belief that there are no gods but God (Allāh), and that Muhammad is God's messenger. God is described in Sura al-Ikhlas as:

- "...God, the One and Only; God, the Eternal, Absolute; He begetteth not, nor is He begotten; And there is none like unto Him."

In Arabic, God is called Allāh. The word is etymologically connected to ʾilāh "deity". A common misconception is that Muslims consider Allāh to be a different deity than that worshipped by Christians and Jews. However, Allah is simply the Arabic word for "God". The word predates Muhammad and, at least in origin, does not specify a "God" different from the one worshipped by Judaism and Christianity, the other Abrahamic religions. Allāh is also used by Arab speaking Christian and Jewish people to refer to God as they worship him.

God is described numerous times in the Qur'an, for example:

- "(He is) the Creator of the heavens and the earth: He has made for you pairs from among yourselves, and pairs among cattle: by this means does He multiply you: there is nothing whatever like unto Him, and He is the One that hears and sees (all things)." .

The implicit usage of the definite article in Allah linguistically indicates the divine unity. Muslims believe that the God they worship is the same God of Abraham. Muslims reject the Christian doctrine concerning the trinity of God, seeing it as akin to polytheism.

No Muslim visual images or depictions of God are meant to exist because such artistic depictions may lead to idolatry. Moreover, most Muslims believe that God is incorporeal, making any two- or three- dimensional depictions impossible. Such aniconism can also be found in Jewish and some Christian theology. Instead, Muslims describe God by the names and attributes that he revealed to his creation. All but one Sura (chapter) of the Qur'an begins with the phrase "In the name of God, the Beneficent, the Merciful".

Muhammad

Muhammad, also Mohammed, Mohamet, and other variants was an Arab religious and political leader who established Islam and the Muslim community (Ummah) to whom he preached. He is considered the greatest prophet in Islam, and is venerated and honoured as such. Muslims do not regard him as the founder of a new religion, but rather believe him to be the last in a line of prophets of God and regard his mission as one of restoring the original monotheistic faith of Adam, Abraham and other prophets of Islam that had become corrupted by man over time.

For the last 23 years of his life, beginning at age 40, Muhammad reported receiving revelations from God delivered through the angel Gabriel. The content of these revelations, known as the Qur'an, was memorized and recorded by his followers. These memories and recordings were then compiled into a single volume shortly after his death.

All Muslims believe that Muhammad was sinless in the sense of transmitting the revelation:

- “And if the apostle were to invent any sayings in Our name, We should certainly seize him by his right hand, And We should certainly then cut off the artery of his heart: Nor could any of you withhold him (from Our wrath).” 69:44-47.

The understanding that Muhammad did commit sin does exist among Sunnis. However, the doctrine of sinlessness of Muhammad is also more or less incorporated into Sunnis' beliefs. Some Sunni scholars believe that the doctrine of the sinlessness of the Prophets originated with the Shi'a, specifically in connection with the Imamat, and was transmitted to the Sunnis via the Sufis and Mu'tazila. Shia scholars disagree.

Qiyamah

Main article: QiyamahYou must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

Qiyamah is the Arabic equivalent of the Christian belief in the Last Judgement. Belief in Qiyâmah is part of Aqidah and is a fundamental tenet of faith in Islam. The trials and tribulations of Qiyâmah are detailed in both the Qur'an and the Hadith, as well as in the commentaries of the Islamic scholars such as al-Ghazali, Ibn Kathir, Ibn Majah, Muhammad al-Bukhari, and Ibn Khuzaimah, who explain them in detail.

Muslims believe that every human, Muslim and non-Muslim alike, is held accountable for his or her deeds and are judged by Allah accordingly (Qur'an 74.38). At a time unknown to man, but preordained, when people least expect it, Allah will give permission for the Qiyâmah to begin. The archangel Israfil, referred to as the Caller, will sound a horn sending out a "Blast of Truth". This event is also found in Jewish eschatology, in the Jewish belief of "The Day of the Blowing of the Shofar", Yom Terua.

The tradition explains Qiyamah thus:

all men and women will fall unconscious. Muhammad is the first to awake and he sees Moses, who may or may not have awoken prior, holding up the Throne of Allah at the mountain of Tur. On the other hand, those who truly believe in Allah, and are pious, the Al-Ghurr-ul-Muhajjalun, due to the trace of ritual ablution performed during their lives, repent their sin and return to "jannah (the Garden) beneath which rivers flow,". The world is destroyed. The dead will rise from their graves and gather, waiting to be judged for their actions

Sources of Islam

Qur'an

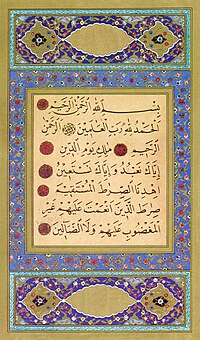

The Qur'an is considered by Muslims to be the literal, undistorted word of God, and is the central religious text of Islam. It has also been called, in English, "the Koran" and (archaically) "the Alcoran". Qur'an is the currently preferred English transliteration of the Arabic original (قرآن), which means “recitation”. Although the Qur'an is referred to as a "book", when Muslims refer in the abstract to "the Qur'an," they are usually referring to the scripture as recited in Arabic -- the words themselves -- rather than to the printed work or any translation of it. The printed work of Qur'an is referred to as "Mus-haf", which is a word etymologically derived from the word "Saheefah" (paper). "Mus-haf" is a word that is solely used to describe the Qur'an when it is in book form.

Muslims believe that the verses of the Qur'an were revealed to Muhammad by God through the Angel Gabriel on numerous occasions between the years 610 and up till his death on July 6 632. Modern Western historians have concluded that Muhammad was sincere in his claim of receiving revelation, "for this alone makes credible the development of a great religion." Modern historians generally decline to address the further question of whether the messages Muhammad reported being revealed to him were from "his unconscious, the collective unconscious functioning in him, or from some divine source", but they acknowledge that the material came from "beyond his conscious mind"

Western modern academics generally reject the notion that the Qur'an of today is markedly different from the words Muhammad claimed to have been revealed to him. In fact, the source of ambiguity in the quest for historical Muhammad is more the lack of knowledge about the pre-Islamic Arabia.

Most Muslims regard paper copies of the Qur'an with veneration, washing as for prayers before reading the Qur'an. Old Qur'ans are not destroyed as wastepaper, but burned.

Many Muslims memorize at least some portion of the Qur'an in the original language (i.e. Arabic), at least the verses needed to recite prayers. Those who have memorized the entire Qur'an are known as hāfiz (plural huffāz). Muslims believe that the Qur'an is perfect only as revealed in the original Arabic. Translations, they maintain, are the result of human effort, and are deficient because of differences in human languages, because of the human fallibility of translators, and (not least) because any translation lacks the inspired content found in the original. Translations are therefore regarded only as commentaries on the Qur'an, or "interpretations of its meaning", not as the Qur'an itself. Many modern, printed versions of the Qur'an feature the Arabic text on one page, and a vernacular translation on the facing page.

Sunnah

Main article: SunnahSunnah literally means “trodden path”, and therefore, the sunnah of the prophet means “the way of the prophet”. Terminologically, the word ‘Sunnah’ in Sunni Islam means those religious actions that were instituted by the Prophet Muhammad during the 23 years of his ministry and which Muslims initially received through consensus of companions of Muhammad (Sahaba), and further through generation-to-generation transmission. According to some opinions, sunnah in fact consists of those religious actions that were initiated by prophet Abraham and were only revived by prophet Muhammad.

The question of hadith (words and deeds of the Prophet) falling within the abode of the sunnah is an interesting one, and is highly dependent on the context. In the context of Islamic Law, Imam Malik and the Hanafi scholars differentiate between the Sunnah and the Hadith. Imam Malik, for instance, is supposed to have rejected hadiths that reached him because, according to him, they were against the established practice of the people of Medinah. In Shi'a Islam, the word 'Sunnah' means the deeds, sayings and approvals of Muhammad and the twelve Imams who Shi'a Muslims believe were chosen by God to succeed the prophet and to lead mankind in every aspect of life.

Hadith

Main article: HadithHadith are traditions relating to the words and deeds of Muhammad. Hadith collections are regarded as important tools for determining the Sunnah, or Muslim way of life, by all traditional schools of jurisprudence. A hadith was originally an oral tradition relevant to the actions and customs of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Starting the first Islamic civil war of the 7th century, those receiving the hadith started to question the sources of the saying . This resulted in a chain of transmission, for example "A told me that B told him that Muhammad said". The hadith were eventually recorded in written form, had their chain of transmission recorded and were collected into large collections mostly during the reign of Umar II during 8th century, something that solidified in the 9th century. These works are still today referred to in matters of Islamic law and history.

Western Academics are much more critical towards Hadith collections, contrasting with their view about the reliability of the Quran. Bernard Lewis states that "the collection and scrutiny of Hadiths didn't take place until several generations" after Muhammad's death and that "during that period the opportunities and motives for falsification were almost unlimited." In addition to the problem of oral transmission for over a hundred years, there existed motives for deliberate distortion. The Muslims themselves at an early date realized that many Hadiths were fabricated and thus developed a whole science of criticism to distinguish between genuine Hadiths and pious or impious frauds." However modern critics have pointed out many defects in their approach (e.g. the easiness of forging a chain of authorities as a tradition, and furthremore rejection of some relators imlpies the victory of one thought over the others).

The overwhelming majority of Muslims consider hadith to be essential supplements to and clarifications of the Qur'an, Islam's holy book. In Islamic jurisprudence, the Qur'an contains many rules for the behavior expected of Muslims. However, there are many matters of concern, both religious and practical, on which there are no specific Qur'anic rules. Muslims believe that they can look at the way of life, or sunnah, of Muhammad and his companions to discover what to imitate and what to avoid. Muslim scholars also find it useful to know how Muhammad or his companions explained the revelations, or upon what occasion Muhammad received them. Sometimes this will clarify a passage that otherwise seems obscure. Hadith are a source for Islamic history and biography. For the vast majority of devout Muslims, authentic hadith are also a source of religious inspiration. However, some contemporary Muslims argue that the Qur'an alone is sufficient.

Five Pillars of Islam

Main articles: Five Pillars of Islam and Practices of the ReligionThe Five Pillars of Islam is the term given to what are understood among many Muslims to be the five core aspects of Sunni Islam. Shi'a Muslims accept the Five Pillars, but also add several other practices to form the Branches of Religion.

Shahadah

The basic creed or tenet of Islam is found in the shahādatān ("two testimonies"): Template:ArabDIN; "I testify that there is none worthy of worship except God and I testify that Muhammad is the Messenger of God." As the most important pillar, this testament can be considered a foundation for all other beliefs and practices in Islam. Ideally, it is the first words a new-born will hear, and children are taught to recite and understand the shahadah as soon as they are able to. Muslims must repeat the shahadah in prayer, and non-Muslims must use the creed to formally convert to Islam.

Salat

The second pillar of Islam is salat, the requirement to pray five times a day at fixed times. Each salat is performed facing towards the Kaba in Mecca. However, in the early days of Islam prior to the hijra and until the beginning of the seventh month after hijra Muslims offered salat facing towards Jerusalem. Salat is intended to focus the mind on God; it is a personal communication with God, expressing gratitude and worship. According to the Qur'an () the benefit of prayer "restrains from shameful and evil deeds". Salat is compulsory but there are flexibilities under certain circumstances. For example in the case of sickness or lack of space, a worshipper can offer salat while sitting or even lying, and the prayer can be shortened when travelling.

The salat must be performed in the Arabic language to the best of each worshipper's ability (although the du'a afterwards need not be in Arabic), and the lines are to be recited by heart, although beginners may use written aids. The worshipper's body and clothing, as well as the place of prayer, must be cleansed. All salat should be conducted within the prescribed time period or waqt and with the appropriate number of raka'ah. While prayers may be made at any point within the waqt, it is considered best to begin them as soon as possible after the call to prayer is heard. When a worshipper is too far from a mosque to hear a call to prayer, the time may be inferred from the position of the sun in the sky.

Zakat

Zakat, or alms-giving, is giving charity to the poor and needy by able Muslims, based on the wealth that one has accumulated. It is a personal responsibility intended to ease economic hardship for others and eliminate inequality. It consists spending a fixed portion of one's wealth for the poor or needy, including people whose hearts need to be reconciled, slaves, those in "debt," those in the way of God, and the travelers in the society. A Muslim may also donate an additional amount as an act of voluntary charity (sadaqah), in order to achieve additional divine reward.

There are two main types of zakât, zakât on traffic, which is a per head payment equivalent to cost of around 2.25 kilograms of the main food of the region paid during the month of Ramadan by the head of a family for himself and his dependents, and zakât on wealth, which covers money made in business, savings, income, crops, livestock, gold, minerals, hidden treasures unearthed, and so on.

The payment of zakât is obligatory on all Muslims. In current usage it is interpreted as a 2.5% levy on most valuables and savings held for a full lunar year, if the total value is more than a basic minimum known as nisab (3 ounces or 87.48g of gold). At present (as of 5 October 2006), nisab is approximately US $1,725 or an equivalent amount in any other currency.

Sawm

Sawm, or fasting, is an obligatory act during the month of Ramadan. Muslims must abstain from food, drink, and sexual intercourse from dawn to dusk during this month, and are to be especially mindful of other sins that are prohibited. This activity is intended to allow Muslims to seek nearness to God as well as remind them of the needy. During Ramadan, Muslims are also expected to put more effort into following the teachings of Islam by refraining from violence, anger, envy, greed, lust, angry/sarcastic retorts, gossip, and are meant to try to get along with each other better than normal. All obscene and irreligious sights and sounds are to be avoided. The fast is an exacting act of deeply personal worship in which Muslims seek a raised level of closeness to God. The act of fasting is said to redirect the heart away from worldly activities and its purpose being to cleanse your inner soul, and free it of harm.

Fasting during Ramadan is not obligatory for several groups for whom it would be excessively problematic. Children before the onset of puberty are not required to fast, though some do. Also some small children fast for half a day instead of a whole day so they get used to fasting. However, if puberty is delayed, fasting becomes obligatory for males and females after a certain age. According to Qur'an, if fasting would be dangerous to people's health, such as to people with an illness or medical condition, and sometimes elderly people, they are excused. For example, diabetics and nursing or pregnant women usually are not expected to fast. According to hadith, observing the Ramadan fast is not allowed for menstruating women. Other individuals for whom it is usually considered acceptable not to fast are those in battle, and travelers who intended to spend fewer than five days away from home. If one's condition preventing fasting is only temporary, one is required to make up for the days missed after the month of Ramadan is over and before the next Ramadan arrives. If one's condition is permanent or present for an extended amount of time, one may make up for the fast by feeding a needy person for every day missed.

Hajj

The Hajj is a pilgrimage that occurs during the month of Dhu al-Hijjah in the city of Mecca. Every able-bodied Muslim who can afford to do so is obliged to make the pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in his or her lifetime. Mecca is so important because it was the place where the Islamic prophet Muhammad was said to have lived and gained his prophet status. The government of Saudi Arabia issues special visas to foreigners for the purpose of the pilgrimage, which takes place during the Islamic month of Dhu al-Hijjah. Entrance to Mecca itself is forbidden to non-Muslims, and the entire city is considered a holy site to Islam.

The pilgrim, the hajj, is honoured in his or her community. For some, this is an incentive to perform the Hajj. Islamic teachers say that the Hajj should be an expression of devotion to God, not a means to gain social standing. The believer should be self-aware and examine his or her intentions in performing the pilgrimage. This should lead to constant striving for self-improvement.

Organization

Mosques

Main article: MosqueA mosque is a place of worship for Muslims. Muslims often refer to the mosque by its Arabic name, masjid. The word "mosque" in English refers to all types of buildings dedicated for Islamic worship, although there is a distinction in Arabic between the smaller, privately owned mosque and the larger, "collective" mosque (masjid jami) (Arabic: جامع), which has more community and social amenities.

The primary purpose of the mosque is to serve as a place where Muslims can come together for prayer. Nevertheless, mosques are known around the world nowadays for their general importance to the Muslim community as well as their demonstration of Islamic architecture. They have developed significantly from the open-air spaces that were the Quba Mosque and Masjid al-Nabawi in the seventh century. Today, most mosques have elaborate domes, minarets, and prayer halls. Mosques originated on the Arabian Peninsula, but now exist on all the world's inhabited continents. They are not only places for worship and prayer, but also places to learn about Islam and meet fellow believers.

According to Islamic beliefs, the first mosque in the world was the Kaaba, which was built by Abraham upon an order from God. The oldest Islamic-built mosque is the Quba Mosque in Medina. When Muhammad lived in Mecca, he viewed Kaaba as his first and principal mosque and performed prayers there together with his followers. Even during times when the pagan Arabs performed their rituals inside the Kaaba, Muhammad always held the Kaaba in very high esteem. The Meccan tribe of Quraish, which was responsible for guarding Kaaba, attempted to exclude Muhammad's followers from the sanctuary, which became a subject of Muslim complaints recorded in the Qur'an. When Muhammad conquered Mecca in 630, he converted Kaaba to a mosque, which has since become known as the Masjid al-Haram, or Sacred Mosque. The Masjid al-Haram was significantly expanded and improved in the early centuries of Islam in order to accommodate the increasing number of Muslims who either lived in the area or made the annual Hajj, or pilgrimage, to Mecca, before it acquired its present shape in 1577 in the reign of the Ottoman sultan Selim II.

The first thing Muhammad did upon arriving with his followers near Medina (then named Yathrib) after the emigration from Mecca in 622 was build the Quba Mosque in a village outside Medina. Today, the Masjid al-Haram in Mecca, the Masjid al-Nabawi in Medina and Al Aqsa (for the majority of Muslims) in Jerusalem are considered the three holiest sites in Islam.

Islamic calendar

Main article: Islamic calendarIslam dates from the Hijra, or migration from Mecca to Medina. Year 1, AH (Anno Hegira) corresponds to AD 622 or 622 CE, depending on the notation preferred (see Common Era). It is a lunar calendar, but differs from other such calendars (e.g. the Celtic calendar) in that it omits intercalary months, being synchronized only with lunations, but not with the solar year, resulting in years of either 354 or 355 days. Therefore, Islamic dates cannot be converted to the usual CE/AD dates simply by adding 622 years. Islamic holy days fall on fixed dates of the lunar calendar, which means that they occur in different seasons in different years in the Gregorian calendar.

Festivals

Main articles: Eid, Eid ul-Fitr, and Eid ul-AdhaThere are two festivals that are considered Sunnah.

Rituals associated with these festivals are:

- Sadaqah (charity) before Eid ul-Fitr prayer.

- The Prayer and the Sermon on Eid day.

- Takbirs (glorifying God) after every prayer in the days of Tashriq (see footnote for def.)

- Sacrifice of unflawed, four legged grazing animal of appropriate age after the prayer of Eid ul-Adha in the days of Tashriq.

Dietary laws

Islamic law does not present a comprehensive list of pure foods and drinks. However, it sanctions:

- prohibition of swine, blood, meat of dead animals and animals slaughtered in the name of someone other than Allah.

- slaughtering in the prescribed manner of tadhkiyah (cleansing) by taking Allah’s name.

- prohibition of intoxicants

The prohibition of dead meat is not applicable to fish and locusts. Also hadith literature prohibits beasts having sharp canine teeth, birds having claws and tentacles in their feet, Jallalah(animals whose meat carries a stink in it because they feed on filth), tamed donkeys, and any piece cut from a living animal.

Islamic knowledge

There are some branches of knowledge which have been developed on the basis of the Qur'an and Sunnah to answer Muslims' questions in their religious life.

Theology

Main articles: Muslim theology and KalamMuslim theology is a branch of knowledge about Islamic faith and beliefs which tries to rationalize the ideas expressed in Qur'an and hadith and answer Muslim questions about them, and to try to challenge non-Muslims' faith and beliefs. The contents of Muslim theology can be divided into theology proper, theodicy, eschatology, anthropology, apophatic theology, and comparative religion. The major schools of theology are Ash'ari, Imami, Ismaili, Maturidi, Murji'ah and Mu'tazili.

Law

The sharia (Arabic for "well-trodden path") is Islamic law, as shown by traditional Islamic scholarship. The Qur'an is the foremost source of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh). The second source is the sunnah of Muhammad and the early Muslim community. The sunnah is not itself a text like the Qur'an, but it is the practical adherence of Muslims to matters of worship. The role of hadith is a disputed one in Islamic law. Collections of Hadith (Arabic for report) contain narrations of Muhammad's sayings, deeds, and actions. According to a few scholars, such as Imam Shafi'i, it is secondary to the Qur'an, whereas others, such as Imam Malik and the Hanafi scholars, hold it in subjugation to sunnah and often reject a hadith if it goes against established practices. Ijma (consensus of the community of Muslims) and qiyas (analogical reasoning) are generally regarded as the third and fourth sources of Sharia, but have been contested by some scholars, who believe that according to the Qur'an other sources should take precedence.

Islamic law covers all aspects of life, from broad topics of governance and foreign relations all the way down to issues of daily living. Islamic laws that were covered expressly in the Qur’an were referred to as hudud laws and include specifically the five crimes of theft, highway robbery, intoxication, adultery and falsely accusing another of adultery, each of which has a prescribed "hadd" punishment that cannot be forgone or mitigated. The Qur'an also details laws of inheritance, marriage, restitution for injuries and murder, as well as rules for fasting, charity, and prayer. However, the prescriptions and prohibitions may be broad, so how they are applied in practice varies. Islamic scholars, the ulema], have elaborated systems of law on the basis of these broad rules, supplemented by the hadith reports of how Muhammad and his companions interpreted them.

In current times, as Islam has spread to non Arabic speaking countries such as Iran, Indonesia, Great Britain, and the United States, not all Muslims understand the Qur'an in its original Arabic. Thus, when Muslims are divided in how to handle situations, they seek the assistance of a mufti (Islamic judge) who can offer them advice based on the sharia and hadith.

Fiqh is the Islamic term for Islamic jurisprudence. It is regarded as an expansion of the divine law or sharia, complemented by the rulings (fatwa) of Islamic jurists (ulema) to direct the lives of Muslims. The modus operandi of the Muslim jurist is usul al-fiqh. Recognised fields of Islamic jurisprudence include those relating to the economy (فقه المعاملات), politics, the family, criminal law (فقه العقوبات), etiquette (الآداب), theology, hygiene, and the rules of war(فقه الجهاد).

Tafsir

Main article: TafsirTafsir is Qur'anic exegesis or commentary. Someone who writes tafsir is a mufassir. The Qur'an has sparked a huge body of commentary and explication. According to Allameh Tabatabaei, tafsir means "explaining the meanings of the Qur'anic verse, clarifying its import and finding out its significance."

Tafsir was one of the earliest academic activities in Islam. The Prophet was the first person who described the Ayats for Muslims: " A similar (favour have ye already received) in that We have sent among you a Messenger of your own, rehearsing to you Our Signs, and sanctifying you, and instructing you in Scripture and Wisdom, and in new knowledge." 2:151

There are some sources that are used to understand the meaning of Qur'anic verses: the Qur'an itself, hadith, Aribiq (Fiqh alloghat), memories of the occasions of revelation (asbāb al-nuzūl), the circumstances under which Muhammad spoke, and reason. There are also different approaches to the explanation of the meaning of verses.

Denominations

Main article: Divisions of IslamThere are a number of Islamic religious denominations, each of which have significant theological and legal differences from each other but possess similar essential beliefs. The major schools of thought are Sunni and Shi'a; Sufism is generally considered to be a mystical inflection of Islam rather than a distinct school. According to most sources, present estimates indicate that approximately 85% of the world's Muslims are Sunni and approximately 15% are Shi'a.

Sunni

The Sunni are the largest group in Islam. In Arabic, as-Sunnah literally means "principle" or "path." Sunnis and Shi'a believe that Muhammad is a perfect example to follow, and that they must imitate the words and acts of Muhammad as accurately as possible. Because of this reason, the sunnah (practices which Muhammad established in the community) is described as a main pillar of Sunni doctrine, with the place of hadith having been argued by scholars as part of the sunnah.

Sunnis recognize four major legal traditions (madhhabs): Maliki, Shafi'i, Hanafi, and Hanbali. All four accept the validity of the others and a Muslim might choose any one that he/she finds agreeable to his/her ideas. There are also several orthodox theological or philosophical traditions (kalam). The more recent Salafi movement among Sunnis, adherents of which often refuse to categorize themselves under any single legal tradition, sees itself as restorationist and claims to derive its teachings from the original sources of Islam.

Shi'a

Shi'a Muslims, the second-largest branch, differ from the Sunni in rejecting the authority of the first three caliphs. They honor different accounts of Muhammad (hadith) and have their own legal traditions. The concept of Imamah (leadership) plays a central role in Shi'a doctrine. Shi'a Muslims hold that leadership should not be passed down through a system such as the caliphate, but rather, descendants of Muhammad should be given this right as Imams. Furthermore, they believe that the first Imam, Ali ibn Abu Talib, was explicitly appointed by Muhammad to be his successor.

See also: Historic background of the Sunni-Shi'a splitSufism

Sufism is a mystical form of Islam followed by some Muslims within both the Sunni and Shi'a sects. Sufis generally believe that following Islamic law or jurisprudence (or fiqh) is only the first step on the path to perfect submission; they focus on the internal or more spiritual aspects of Islam, such as perfecting one's faith and subduing one's own ego (nafs). Most Sufi orders, or tariqas, can be classified as either Sunni or Shi'a. However, there are some that are not easily categorized as either Sunni or Shi'a, such as the Bektashi. Sufis are found throughout the Islamic world, from Senegal to Indonesia. Their innovative beliefs and actions often come under criticism from Wahhabis, who consider certain practices to be against the letter of Islamic law.

Others

Another sect which dates back to the early days of Islam is that of the Kharijites. The only surviving branch of the Kharijites are the Ibadi Muslims. Ibadism is distinguished from Shiism by its belief that the Imam (Leader) should be chosen solely on the basis of his faith, not on the basis of descent, and from Sunnism in its rejection of Uthman and Ali and strong emphasis on the need to depose unjust rulers. Ibadi Islam is noted for its strictness, but, unlike the Kharijites proper, Ibadis do not regard major sins as automatically making a Muslim an unbeliever. Most Ibadi Muslims live in Oman.

Another trend in modern Islam is that which is sometimes called progressive. Followers may be called Ijtihadists. They may be either Sunni or Shi'ite, and generally favor the development of personal interpretations of Qur'an and Hadith.

There is also a very small sect isolated within India and Pakistan which identifies themselves as Ahmadi Muslims, who believe in the continuation of prophethood after Muhammad, in contradiction to mainstream Muslims who believe that Muhammad was the final prophet. Although this sect is not accepted as Muslim by mainstream Islamic scholars, they continue to identify themselves with the term Muslim. Likewise, Ahmadis believe that rest of the Muslims who do not share faith with them are non-Muslims.

Islam and other religions

Main article: Islam and other religionsThe Qur'an contains both injunctions to respect other religions, and to fight and subdue unbelievers during war. The Qur'an respects Jews and Christians as fellow people of the book (monotheists following Abrahamic religions). The Qur'an however claimed that "it was restoring the pure monotheism of Abraham which had been corrupted in various, not clearly specified, ways by Jews and Christians." (the charge of altering the scripture may mean no more than giving false interpretations to some passages, though in later Islam it was taken to mean that parts of the Bible are corrupt. )

On the issue of tolerance towards other faiths, one point should be made at the beginning. Until relatively modern times, tolerance in the treatment of non-believers, at least as it is understood in west after John Locke, was neither valued, nor its absence condemned by both Muslims and Christians. The fair and usual definition of tolerance as understood and applied in pre-modern time was that: "I am in charge. I will allow you some though not all of the rights and privileges that I enjoy, provided that you behave yourself according to rules that I will lay down and enforce."

Traditionally Jews and Christians living in Muslim lands, known as dhimmis were allowed to "practice their religion, subject to certain conditions, and to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy" and guaranteed their personal safety and security of property, in return for paying tribute to Muslims and acknowledging Muslim supremacy. They had several social and legal disabilities. Many of the disabilities was highly symbolic. The most degrading one was the requirement for distinctive clothing, invented in early medieval Baghdad, though it was highly erratic. However, persecution in the form of violent and active repression was rare and atypical While recognizing the inferior status of dhimmis under Islamic rule, Bernard Lewis, Professor Emeritus of Near Eastern Studies at Princeton University, states that in most respects their position was "was very much easier than that of non-Christians or even of heretical Christians in medieval Europe": for example, in contrast, Dhimmis rarely faced martydom or exile, or forced compulsion to change their religion, and with certain exceptions they were free in their choice of residence and profession. Most conversions were voluntary and happened for a number of different reasons. However there was forced conversions mostly in the 12th century under the Almohad dynasty of North Africa and al-Andalus as well as in Persia.

Related faiths

The Yazidi, Bábísm, Bahá'í Faith, Berghouata and Ha-Mim religions either emerged out of an Islamic milieu or have beliefs in common with Islam in varying degrees; in almost all cases those religions were also influenced by traditional beliefs in the regions where they emerged, but consider themselves independent religions with distinct laws and institutions. The last two religions no longer have any followers.

History

Islam began in Arabia in the 7th century under the leadership of Muhammad, who spread Islam across all of Arabia. Within a century of his death, an Islamic state stretched from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to central Asia in the east, which, however, was soon torn by civil wars (fitnas). After this, there would always be rival dynasties claiming the caliphate, or leadership of the Muslim world, and many Islamic states or empires offering only token obedience to an increasingly powerless caliph.

Despite this fragmentation of Islam as a political community, the empires of the Abbasid caliphs, the Mughals, and the Seljuk Turk, Safavid Persia and Ottomans were among the largest and most powerful in the world. Arabs made many Islamic centers of culture and science and produced notable scientists, astronomers, mathematicians, doctors and philosophers during the Golden Age of Islam. Technology flourished; there was much investment in economic infrastructure, such as irrigation systems and canals; stress on the importance of reading the Qur'an produced a comparatively high level of literacy in the general populace.

Islam at its geographical height stretched for thousands of miles. Islamic conquest into Christian Europe spread as far as southern France. After the disastrous defeat of the Byzantines at the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, Christian Europe, at the behest of the Pope, launched a series of Crusades and for a time captured Jerusalem. Saladin, however, recaptured Palestine and defeated the Shiite Fatimids.

In the 15th century and 16th centuries three major Muslim empires were created: the Ottoman Empire in much of the Middle East, Balkans and Northern Africa; the Safavid Empire in Iran; and the Mughul Empire in India. These new imperial powers were made possible by the discovery and exploitation of gunpowder, and more efficient administration.

By the end of the 19th century, however all three had declined due to internal conflict and were later destroyed by Western cultural influence and military ambitions. Following World War I, the remnants of the Ottoman Empire were parceled out as European protectorates or spheres of influence. Many Islamic countries have now been formed from these protectorates, such as Iraq, Iran, of Lebanon. Islam and Islamic political power have become much more influential in the 21st century, particularly due to Islamic control of most of the world's oil.

Islamicization, the process of the conversion of societies to Islam, originally closely followed the rapid growth of the Arab Empire in the first centuries after Muhammad's death. Muslim dynasties were soon established in North Africa, the Middle East and Persia and the conversion of the population was a protracted process. Although the expansion of Muslim empires eventually slowed, conversion to Islam continued in other ways. Muslim countries dominated trade in the Indian Ocean and the Sahara and it was through trade, Sufi preachers, and interaction with locals that Islam grew in areas such as the Sahel and the East Indies.

Caliphate

Main article: CaliphMuhammed died in 632 without appointing a successor or leaving in place a system for choosing one, according to the majority of Muslims. As a result, the caliphate was established. Caliph is the title for the Islamic leader of the Ummah, or community of Islam. It is a transliterated version of the Arabic word "Khalīfah" which means "successor" or "representative". Some of the early leaders of the Muslim community following Muhammad's death called themselves "Khalifat Allah", meaning representative of God, but the alternative title of "Khalifat rasul Allah", meaning the successor to the prophet of God, eventually became the standard title. Some academics prefer to transliterate the term as Khalīf.

Caliphs were often also referred to as Amīr al-Mu'minīn (أمير المؤمنين) "Commander of the Faithful", or, more colloquially, leader of the Muslims. This title has been shortened and romanized to "emir".

None of the early caliphs claimed to receive divine revelations, as did Muhammad; since Muhammad is the last divine messenger, none of them claimed to be a nabī, "a prophet" or a "rasul" or divine messenger. Muhammad's revelations were soon codified and written down as the Qur'an, which was accepted as a supreme authority, limiting what a caliph could legitimately command. However, the early caliphs believed themselves to be the spiritual and temporal leaders of Islam, and insisted that implicit obedience to the caliph in all things was the hallmark of the good Muslim. The role became strictly temporal however, on the rise of the ulama.

After the first four caliphs (Abu Bakr, Umar ibn al-Khattab, Uthman ibn Affan, and Ali ibn Abi Talib), the title was claimed by the Umayyads, the Abbasids, and the Ottomans, as well as by other, competing lineages in Spain, Northern Africa, and Egypt. Most historical Muslim rulers simply titled themselves sultans or amirs, and gave token obedience to a caliph who often had very little real authority. The title has been defunct since the Republic of Turkey abolished the Ottoman caliphate in 1924.

Once the subject of intense conflict and rivalry amongst Muslim rulers, the caliphate has lain dormant and largely unclaimed for much of the past 82 years. Though many Muslims might favor a caliphate in the abstract, tight restrictions on political activity in many Muslim countries coupled with the tremendous practical obstacles to uniting over fifty disparate nation-states under a single institution have prevented efforts to revive the caliphate from garnering much active support, even amongst devout Muslims. No attempts at rebuilding a power structure based on Islam were successful anywhere in the Muslim World until the Iranian Revolution in 1979, which was based on Shia principles and whose leaders did not outwardly call for the restoration of a global Caliphate (although Iran has subsequently made efforts to 'export' its revolution to other Muslim countries).

Contemporary Islam

Although the most prominent movement in Islam in recent times has been fundamentalist Islamism, there are a number of liberal movements within Islam, which seek alternative ways to align the Islamic faith with contemporary questions.

Early Sharia had a much more flexible character than is currently associated with Islamic jurisprudence, and many modern Muslim scholars believe that it should be renewed, and the classical jurists should lose their special status. This would require formulating a new fiqh suitable for the modern world, e.g. as proposed by advocates of the Islamization of knowledge, and would deal with the modern context. One vehicle proposed for such a change has been the revival of the principle of ijtihad, or independent reasoning by a qualified Islamic scholar, which has lain dormant for centuries.

This movement does not aim to challenge the fundamentals of Islam; rather, it seeks to clear away misinterpretations and to free the way for the renewal of the previous status of the Islamic world as a centre of modern thought and freedom.

Many Muslims counter the claim that only "liberalization" of the Islamic Sharia law can lead to distinguishing between tradition and true Islam by saying that meaningful "fundamentalism", by definition, will eject non-Islamic cultural inventions — for instance, acknowledging and implementing Muhammad's insistence that women have God-given rights that no human being may legally infringe upon. Proponents of modern Islamic philosophy sometimes respond to this by arguing that, as a practical matter, "fundamentalism" in popular discourse about Islam may actually refer, not to core precepts of the faith, but to various systems of cultural traditionalism.

See also: Modern Islamic philosophyDemographics of Islam today

Main articles: Islam by country and Demographics of Islam

Based on the figures published in the 2005 CIA World Factbook (), Islam is the second largest religion in the world. According to the Al Islam, and Samuel Huntington, Islam is the fastest growing major religion by percent (though not by raw numbers). Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance estimate that it is growing at about 2.9% annually, as opposed to 2.3% per year global population growth. Most of this growth is due to the high population growth in many Islamic countries (six out of the top-ten countries in the world with the highest birth rates are majority Muslim ). The birth rates in some Muslim countries are now declining.

Commonly cited estimates of the Muslim population today range between 900 million and 1.5 billion people (cf. Adherents.com); estimates of Islam by country based on U.S. State Department figures yield a total of 1.48 billion, while the Muslim delegation at the United Nations quoted 1.2 billion as the global Muslim population in September 2005.

Only 18% of Muslims live in the Arab world; 20% are found in Sub-Saharan Africa, about 30% in the South Asian region of Pakistan, India and Bangladesh, and the world's largest single Muslim community (within the bounds of one nation) is in Indonesia. There are also significant Muslim populations in China, Europe, Central Asia, and Russia.

France has the highest Muslim population of any nation in Western Europe, with up to 6 million Muslims (10% of the population). Albania has the highest proportion of Muslims as part of its population in Europe (70%), although this figure is only an estimate (see Islam in Albania). Countries in Europe with many Muslims include Bosnia and Herzegovina (estimated around 50% are Bosniaks, Muslims) and Macedonia where over 30% of the population is Muslim, mostly ethnic Albanians in Macedonia. The country in Europe with the most Muslims is Russia. The number of Muslims in North America is variously estimated as anywhere from 1.8 to 7 million.

Political and religious extremism

Main article: Islamic extremist terrorismThe term Islamism describes a set of political ideologies derived from Islamic fundamentalism. Most Islamist ideologies hold that Islam is not only a religion, but also a political system that governs the legal, economic and social imperatives of the state according to interpretations of Islamic Law.

Islamic extremist terrorism refers to acts of terrorism claimed by its supporters and practitioners to be in furtherance of the goals of Islam. Its prevalence has heavily increased in recent years, and it has become a contentious political issue in many nations.

The validity of an Islamic justification for these acts is contested by many Muslims, in particular defying some of the rules of Jihad. Islamic extremist violence is not synonymous with all terrorist activities committed by Muslims: nationalists, separatists, and others in the Muslim world often derive inspiration from secular ideologies.

Criticism of Islam

| The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In recent years, Islam has been the subject of criticism and controversy, and is often viewed with considerable negativity in the West. Islam, the Qur'an, and Muhammad, have all been subject to both criticism and vilification, some of which has been dismissed as a product of Islamophobia.

The earliest surviving written criticisms of Islam are to be found in the writings of Christians who came under the early dominion of the Islamic empire. One such Christian was John of Damascus (born c. 676), who was familiar with Islam and Arabic. The second chapter of his book, The Fount of Wisdom, titled 'Concerning Heresies' presents a series of discussions between Christians and Muslims. John claimed a Nestorian monk influenced Muhammad.

Some medieval ecclesiastical writers portrayed Muhammad as possessed by Satan, a "precursor of the Antichrist" or the Antichrist himself.

Maimonides, one of the foremost rabbinical arbiters and philosophers in Jewish history, saw the relation of Islam to Judaism as primarily theoretical. Maimonides has no quarrel with the strict monotheism of Islam, but finds fault with the practical politics of Muslim regimes. Maimonides criticised what he perceived as the lack of virtue in the way Muslims rule their societies and relate to one another.

Notable modern critics include personalities such as Evangelical leader Pat Robertson, who stated that Islam wants to take over the world, that it is not a religion of peace, that radical Muslims are "satanic", and that Osama Bin Laden was a "true follower of Muhammad". Some critics argue that in Islam women have fewer rights than men and that non-Muslims under the dhimmi system have fewer rights than Muslims. According to Freedom House , Saudi Arabia relegates women to second-class citizenship. "Women are not treated as equal members of society. They may not legally drive cars, and their use of public facilities is restricted when men are present. ...Laws discriminate against women in a range of matters including family law, and a woman's testimony is treated as inferior to a man's in court."

See also

Further information: ]|

|

|

|

References

- Vartan Gregorian (2003). Islam: A Mosaic, Not a Monolith. Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. pp. p. ix. ISBN 0-8157-3283-X.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Teece, Geoff (2005). Religion in Focus: Islam. Smart Apple Media. pp. p. 10.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - John L Esposito (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 2. ISBN 0-19-515713-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Office for National Statistics (2003-02-13). "Religion In Britain". Retrieved 2006-08-27.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - BBC (2005-12-23). "Muslims in Europe: Country guide". Retrieved 2006-09-28.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - Watton, Victor, (1993), A student's approach to world religions:Islam, Hodder & Stoughton, Introduction. ISBN 0-340-58795-4

- John Esposito in his book "What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam" p. 4-5

- Encyclopedia of the Qur'an, Qur'an and Polemics article

- MARTIN ACCAD, The Gospels in the Muslim Discourse of the Ninth to the Fourteenth Centuries: an exegetical inventorial table (part I), Islam and Christian–Muslim Relations, Vol. 14, No. 1, 2003

- The name "Allah" is a singular neuter noun.

- Mahound, a term used in the past by Christians to vilify Muhammad cf. John Esposito (1999) p.250, meaning 'devil' or 'spirit of darkness', a thoroughly distorted view of Muhammad in the medieval West, cf. Schimmel, Islam: An Introduction, 1992. For some usage of this term in literature see for example William Shakespeare (1832) "Hamlet: And As You Like It." p.80, or Dante who uses this term in his Divine Comedy cf. Bernard Lewis (2002) p.45. William Montgomery Watt states: "Of all the world's great men none has been so much maligned as Muhammad. At one point Muhammad was transformed into Mahound, the prince of darkness." Bernard Lewis states that "The development of the concept of Mahound started with considering Muhammad as a kind of demon or false god worshipped with Apollyon and Termangant in an unholy trinity. Finally after reformation, Muhammad was conceived as a cunning and self-seeking impostor." cf. Lewis (2002) p.45. In recent times Salman Rushdie, in his book "The Satanic verses", chose the name Mahound to refer to Muhammad. Ayatollah Khomeini issued a fatwah that condemned Rushdie to death and called for his execution. cf. John Esposito (1999) p.250

- Welch, noting the frequency of Muhammad being called as "Al-Amin", a common Arab name, suggests the possibility of "Al-Amin" being Muhammad's given name as it is a masculine form from the same root as his mother's name, A'mina. cf. Encyclopedia of Islam, Muhammad article; The sources frequently say that he, in his youth, was called with the nickname "Al-Amin" meaning "faithful, trustworthy" cf. Carl W. Ernst (2004), p.85

- John Esposito (1998) p.12; (1999) p.25; (2002) p.4-5

- Encyclopedia of Islam, Muhammad article

- F. E. Peters, Islam : a guide for Jews and Christians, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-11553-2, p.9

- The term Qur'an was invented and first used in the Qur'an itself. There are two different theories about this term and its formation, that are discussed in Quran#Etymology cf. Encyclopedia of Islam article on Qur'an.

- The Sinlessness of the Prophets in Light of the Qur'an, by R. Azzam, USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts, March 27, 2000, retrieved March 27, 2006

- Are Prophets of Allah not Sinless?, by Ali A. Khalfan, May 07, 2005, retrieved March 27, 2006

- ^ The Cambridge History of Islam (1970), Cambrdige University Press, p.30

- F.E. Peters, The Quest for Historical Muhammad, International Journal of Middle East Studies (1991) p.291-315

- http://people.uncw.edu/bergh/par246/L21RHadithCriticism.htm

- The Arabs in History, by Bernard Lewis, p. 33-34

- F.E. Peters, The Quest for Historical Muhammad, International Journal of Middle East Studies (1991) p.291-315

- "USC-MSA Compendium of Muslim Texts". Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- Nigosian, S A (2004). Islam: Its History, Teaching, and Practices. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press.

- ^ David B. Doroquez The five Pillars of Islam: The foundation of a Faith and its People]

- ^ Kobeisy, Ahmed Nezar (2004). Counseling American Muslims. Praeger/Greenwood. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0313324727.

- Lindsay, James (2005). Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World. Greenwood Press. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0313322708.

- ^ Hedáyetullah, Muhammad (2002). Dynamics of Islam. Trafford Publishing. pp. 53–55. ISBN 1553698428.

- Lloyd Ridgeon (2003). Major World Religions: From Their Origins to the Present. New York, NY: RoutledgeCorizon. pp. p. 258.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - "Zakat calculator". Retrieved 2006-11-13.

- Arshad Khan (2003). Islam 101: Principles and Practice. Lincoln, Nebraska: Writers Club Press. pp. p.54.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Goldschmidt, Arthur (2002). A Concise History of the Middle East. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press. pp. p. 48.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Hillenbrand, R. "Masdjid. I. In the central Islamic lands". In P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Weinsinck, A.J. "Masdjid al-Haram.". In P.J. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C.E. Bosworth, E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs (ed.). Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - "Masjid Quba'". Ministry of Hajj - Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Retrieved 2006-04-15.

- "The Ottomans: Origins". Washington State University. Retrieved 2006-04-15.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

culwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - Sunan Abu Da'ud 1134

- Sahih Bukhari 1503

- Normally these days are considered to be the ones in which pilgrims stay at Mina once they return from Muzdalifah i.e. 10th, 11th , 12th, and 13th of Dhu al-Hijjah

- Ghamidi, The Ritual of Animal Sacrifice

- ^ Ghamidi(2001), The dietary laws

- Sunan ibn Maja 2314

- Nisai 59

- Al-Zamakhshari. Al-Kashaf, vol. 1, (Beirut: Daru’l-Kitab al-‘Arabi), p. 215

- Sahih Muslim 1934

- Nisai 4447

- Sahih Bukhari 4199

- Sunan Abu Da'ud 2858

- Preface of Al'-Mizan

- John L Esposito (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press US. pp. p. 2. ISBN 0-19-515713-3.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help) - Sunni and Shia Islam, Country Studies, retrieved April 04, 2006

- The Cambridge History of Islam, p.43-44

- Watt, Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, p.116

- Bernard Lewis (1995) p. 211, Mark Cohen (1995) p.xix

- Lewis, Bernard. "The New Anti-Semitism", The American Scholar, Volume 75 No. 1, Winter 2006, pp. 25-36. The paper is based on a lecture delivered at Brandeis University on March 24, 2004.

- Lewis (1984), pp. 10, 20

- Lewis, Bernard. Semites and Anti-Semites: An Inquiry Into Conflict and Prejudice, 1999, W. W. Norton & Company press, ISBN: 0393318397, p.131.

- Lewis (1984) p. 8,62

- Lewis (1984) p. 62, Mark Cohen (1995) p. xvii

- Lewis (1999) p.131

- Lewis (1984), pp. 17, 18, 94, 95; Stillman (1979), p. 27

- Armstrong (2000) p. 116

- ^ Ontario Consultants on Religious Tolerance

- Stats > People > Birth rate > Top 10, NationMaster.com, retrieved March 27, 2006

- "The demographics of radical Islam", by Spengler, Asia Time Online, August 23, 2005, retrieved March 27, 2006

- France, CIA - The World Factbook, January, 2006, retrieved March 27, 2006

- Encyclopedia of the Orient

- Islam Denounces Terrorism Harun Yahya

- Muslims against Terrorism

- The Philosopher of Islamic Terror New York Times

- Ernst, Carl (2002), Following Muhammad : rethinking Islam in the contemporary world, University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0807828378 p. 11

- Ernst (2002) p. 11

- The Muslim World, Volume XLI (1951), pages 88-99,

- De Haeresibus by John of Damascus. See Migne. Patrologia Graeca, vol. 94, 1864, cols 763-73. An English translation by the Reverend John W Voorhis appeared in THE MOSLEM WORLD for October 1954, pp. 392-398.

- Mohammed and Mohammedanism, by Gabriel Oussani, Catholic Encyclopedia, retrieved April 16, 2006

- The Mind of Maimonides, by David Novak, retrieved April 29, 2006

- "Evangelical broadcaster Pat Robertson calls radical Muslims 'satanic'". Associated Press. 2006-03-14. Retrieved 2006-07-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - "Top US evangelist targets Islam". BBC News. 2006-03-14. Retrieved 2006-07-21.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)

Bibliography

- Khan, Muhammad Muhsin & Al-Hilali, Muhammad Taqi-ud-Din. Noble Quran, ISBN 1-59144-004-1

- Mubarkpuri, Saifur-Rahman. The Sealed Nectar: Biography of the Noble Prophet. Dar-us-Salam, ISBN 9960-899-55-1

- Al-Asqalani, Ibn Hajar. Bulugh Al-Maram, ISBN 1-59144-056-4

- Arberry, A. J. The Koran Interpreted: a translation by A. J. Arberry. Touchstone, ISBN 0-684-82507-4

- Kramer, Martin. The Islamism Debate. University Press, (1997) ISBN 965-224-024-9

- Rahman, Fazlur. Islam. University of Chicago Press; 2nd edition, (1979) ISBN 0-226-70281-2

- Safi, Omid. Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender and Pluralism. Oneworld Publications, (2003) ISBN 1-85168-316-X

- Tibi, Bassam. The Challenge of Fundamentalism: Political Islam and the New World Disorder. Univ. of California Press, (1998) ISBN 0-520-08868-9

- Najeebabadi, Akbar Shah. History of Islam. Dar-us-Salam, ISBN 1-59144-031-9

- Walker, Benjamin. Foundations of Islam: The Making of a World Faith, Peter Owen Publishers, London and New York, 1978, ISBN 0-7206-1038-9; Harper Collins, New Delhi, 1999.

- Ghamidi, Javed (2001). Mizan. Dar al-Ishraq. OCLC 52901690.

- Esposito, John (2005). Islam: The Straight Path (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112334.

- Lewis, Bernard (2002). The Arabs in History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280310-7.

- Ernst, Carl (2004). Following Muhammad: Rethinking Islam in the Contemporary World. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-5577-4.

- Peters, F. E. (2003). Islam: A Guide for Jews and Christians. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11553-2.

- Esposito, John (1999). The Islamic Threat: Myth Or Reality?. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513076-6.

- Esposito, John (2002). What Everyone Needs to Know About Islam. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515713-3.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1992). Islam: An Introduction. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-1327-6.

- F. Buhl (A.T. Welch), Annemarie Schimmel, A. Noth, Trude Ehlert (ed.). "Muhammad". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Watt, W. Montgomery (1961). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-881078-4.

- Cohen, Mark (1995). Under Crescent and Cross: The Jews in the Middle Ages. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01082-X.

- Lewis, Bernard (1984). The Jews of Islam. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00807-8.

External links

Academic resources

- University of Southern California Compendium of Muslim Texts

- Encyclopedia of Islam (Overview of World Religions)

- Unit on Islam from the NITLE Arab Culture and Civilization Online Resource

Directories

- Islam in Western Europe, the United Kingdom, Germany and South Asia

- Dmoz.org Open Directory Project: Islam (a list of links of Islam)

Islam and the arts, and other media

- Islamic Art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art

- Muslim Heritage (Foundation for Science Technology and Civilisation, UK)

- Islamic Architecture (IAORG) illustrated descriptions and reviews of a large number of mosques, palaces, and monuments.

- Islamic Philosophy (Journal of Islamic Philosophy, University of Michigan)

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

Categories: