| Revision as of 00:58, 21 January 2007 view sourceCorticopia (talk | contribs)5,613 editsm revert, to prior agreeable version with citation← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:45, 13 January 2025 view source Yovt (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,017 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Country in North America}} | |||

| {{sprotected2}} | |||

| {{about|the country}}{{pp-sock|small=yes}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox Country or territory | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2024}} | |||

| |native_name = ''Estados Unidos Mexicanos'' | |||

| {{Infobox country | |||

| |conventional_long_name = United Mexican States | |||

| | conventional_long_name = United Mexican States | |||

| |common_name = Mexico | |||

| | |

| common_name = Mexico | ||

| | native_name = <span style=white-space:nowrap;>{{native name|es|Estados Unidos Mexicanos}}</span> | |||

| |image_coat = Mexico coat of arms.png | |||

| | |

| image_flag = Flag of Mexico.svg | ||

| | |

| image_flag2 = <!--not officialMexican States Standard.svg//--> | ||

| | |

| image_coat = Coat of arms of Mexico.svg | ||

| | |

| alt_coat = | ||

| | symbol_type = Coat of arms | |||

| |official_languages = ]<br/>] ('']'') | |||

| | national_anthem = <br />{{Lang|es|]}}<br />({{Langx|en|Mexican National Anthem}})]<br />{{center|}} | |||

| |capital = ] | |||

| | other_symbol_type = | |||

| |latd=19 |latm=03 |latNS=N |longd=99 |longm=22 |longEW=W | |||

| | |

| other_symbol = | ||

| | image_map = {{switcher|]|Mexico in the Western Hemisphere|]|Mexico and its states|Default=1}} | |||

| |leader_title1 = ] | |||

| | |

| map_width = | ||

| | |

| capital = ] | ||

| | |

| coordinates = {{Coord|19|26|N|99|8|W|type:city}} | ||

| | largest_city = Mexico City | |||

| |areami² = 758,249 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | |||

| | official_languages = ] (''de facto'')<br />None (''de jure'') | |||

| |area_rank = 15th | |||

| | |

| languages_type = Co-official languages | ||

| | |

| languages = {{Plainlist| | ||

| * 68 ] | |||

| |population_estimate = 108,700,000 | |||

| }} | |||

| |population_estimate_year = 2006 | |||

| | ethnic_groups = '']'' | |||

| |population_estimate_rank = 11th | |||

| | ethnic_groups_year = | |||

| |population_census = 100,349,766 | |||

| | ethnic_groups_ref = | |||

| |population_census_year = 2000 | |||

| | religion = {{unbulleted list|item_style=white-space:nowrap; | |||

| |population_density = 55 | |||

| |{{Tree list}} | |||

| |population_densitymi² = 142 <!--Do not remove per ]--> | |||

| * 88.9% ] | |||

| |population_density_rank = 142nd | |||

| ** 77.7% ] | |||

| |GDP_PPP_year = 2005 | |||

| ** 11.2% ] | |||

| |GDP_PPP = $1.191 ] | |||

| {{Tree list/end}} | |||

| |GDP_PPP_rank = 13th | |||

| |8.1% ] | |||

| |GDP_PPP_per_capita = $10,186 | |||

| |2.4% ] | |||

| |GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 64th | |||

| |0.5% prefer not to say}} | |||

| |GDP_nominal = $1.294 ] | |||

| | |

| religion_ref = <ref name="2020 Census"/> | ||

| | |

| religion_year = 2020 | ||

| | demonym = ] | |||

| |GDP_nominal_per_capita = $7,298 | |||

| | government_type = Federal ]<ref>{{cite web |location=MX Q|url=http://www.scjn.gob.mx/SiteCollectionDocuments/PortalSCJN/RecJur/BibliotecaDigitalSCJN/PublicacionesSupremaCorte/Political_constitucion_of_the_united_Mexican_states_2008.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110511194922/http://www.scjn.gob.mx/SiteCollectionDocuments/PortalSCJN/RecJur/BibliotecaDigitalSCJN/PublicacionesSupremaCorte/Political_constitucion_of_the_united_Mexican_states_2008.pdf |archive-date=11 May 2011 |title=Political Constitution of the United Mexican States, title 2, article 40 |publisher=SCJN |access-date=14 August 2010}}</ref> | |||

| |GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 53rd | |||

| | |

| leader_title1 = ] | ||

| | |

| leader_name1 = ] | ||

| | leader_title2 = ] | |||

| |HDI_rank = 53rd | |||

| | |

| leader_name2 = ] | ||

| | leader_title3 = ] | |||

| |sovereignty_type = ] | |||

| | |

| leader_name3 = ] | ||

| | leader_title4 = ] | |||

| |established_event1 = Declared | |||

| | leader_name4 = ] | |||

| |established_event2 = Recognized | |||

| | |

| legislature = ] | ||

| | |

| upper_house = ] | ||

| | |

| lower_house = ] | ||

| | sovereignty_type = ] | |||

| |currency_code = MXN | |||

| | |

| sovereignty_note = from ] | ||

| | established_event1 = ] | |||

| |utc_offset = -8 to -6 | |||

| | established_date1 = 16 September 1810 | |||

| |time_zone_DST = varies | |||

| | established_event2 = ] | |||

| |utc_offset_DST = | |||

| | established_date2 = 27 September 1821 | |||

| |cctld = ] | |||

| | established_event3 = ] | |||

| |calling_code = 52 | |||

| | established_date3 = 28 December 1836 | |||

| |footnotes = | |||

| | established_event4 = ] | |||

| | established_date4 = 4 October 1824 | |||

| | established_event5 = ] | |||

| | established_date5 = 5 February 1857 | |||

| | established_event6 = ] | |||

| | established_date6 = 5 February 1917 | |||

| | area = | |||

| | today = | |||

| | area_km2 = 1,972,550 | |||

| | area_footnote = | |||

| | area_rank = 13th | |||

| | area_sq_mi = 761,606 | |||

| | percent_water = 1.58 (as of 2015)<ref>{{cite web|title=Surface water and surface water change|access-date=11 October 2020|publisher=Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)|url=https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER|archive-date=24 March 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210324133453/https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SURFACE_WATER|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | population_estimate = {{IncreaseNeutral}} 131,946,900<ref>{{cite web |title=Total population by sex: Mexico |url=https://population.un.org/dataportal/data/indicators/49/locations/484/start/2024/end/2025/table/pivotbylocation?df=89ae8967-12de-4efa-81d2-417484e8a9ef |website=United Nations Population Division |access-date=1 January 2025}}</ref> | |||

| | population_census = 126,014,024<ref>{{cite web |title=Census of Population and Housing 2020 |url=https://en.www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ |website=] |access-date=1 January 2025}}</ref> | |||

| | population_estimate_year = 2025 | |||

| | population_estimate_rank = 10th | |||

| | population_census_year = 2020 | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 61 | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 157 | |||

| | population_density_rank = 142nd | |||

| | GDP_PPP = {{increase}} $3.408 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.MX">{{cite web |url=https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/weo-database/2024/October/weo-report?c=273,&s=NGDPD,PPPGDP,NGDPDPC,PPPPC,&sy=2022&ey=2029&ssm=0&scsm=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2024 Edition. (Mexico) |publisher=] |website=www.imf.org |date=22 October 2024 |access-date=22 October 2024}}</ref> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_year = 2025 | |||

| | GDP_PPP_rank = 12th | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita = {{increase}} $25,557<ref name="IMFWEO.MX" /> | |||

| | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 70th | |||

| | GDP_nominal = {{decrease}} $1.818 trillion<ref name="IMFWEO.MX" /> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_year = 2025 | |||

| | GDP_nominal_rank = 12th | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita = {{decrease}} $13,630<ref name="IMFWEO.MX" /> | |||

| | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 63rd | |||

| | Gini = 40.2 <!--number only--> | |||

| | Gini_year = 2022 | |||

| | Gini_change = decrease <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| | Gini_ref = <ref>{{cite web|url= https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2023/ENIGH/ENIGH2022.pdf|title=El Inegi da a conocer los resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Ingresos y Gastos de los Hogares (ENIGH) 2022|date=July 26, 2023|access-date=September 20, 2024|page=15}}</ref> | |||

| | Gini_rank = | |||

| | HDI = 0.781 <!--number only--> | |||

| | HDI_year = 2023<!-- Please use the year to which the data refers, not the publication year--> | |||

| | HDI_change = increase <!--increase/decrease/steady--> | |||

| | HDI_ref = <ref name="UNHDR">{{cite web|url=https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf|title=Human Development Report 2023/24|language=en|publisher=]|date=13 March 2024|access-date=13 March 2024|archive-date=13 March 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240313164319/https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | HDI_rank = 77th | |||

| | currency = ] | |||

| | currency_code = MXN | |||

| | time_zone = ''See'' ] | |||

| | utc_offset = −8 to −5 | |||

| | utc_offset_DST = −7 to −5 | |||

| | DST_note = | |||

| | time_zone_DST = varies | |||

| | antipodes = | |||

| | date_format = dd/mm/yyyy | |||

| | drives_on = right | |||

| | calling_code = ] | |||

| | cctld = ] | |||

| | footnote_a = {{note|iboxa}}Article 4 of the ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.inali.gob.mx/pdf/LGDLPI.pdf |title=General Law of Linguistic Rights of the Indigenous Peoples |author=INALI |date=13 March 2003 |access-date=7 November 2010 |archive-date=3 August 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160803160009/http://www.inali.gob.mx/pdf/LGDLPI.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.inali.gob.mx/clin-inali/ |title=Catálogo de las lenguas indígenas nacionales: Variantes lingüísticas de México con sus autodenominaciones y referencias geoestadísticas |publisher=Inali.gob.mx |access-date=18 July 2014 |archive-date=8 July 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140708121506/http://www.inali.gob.mx/clin-inali/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | footnote_b = {{note|iboxb}}Spanish is '']'' the official language in the Mexican federal government. | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Mexico''',{{efn|{{langx|es|México}} or ''Méjico'', pronunciation: {{IPA|es|ˈmexiko||es-mx-México.ogg}}; ]: ''Mēxihco''; {{langx|yua|Meejikoo}}}}{{efn|Usually, in ], the name of the country is spelled {{lang|es|México}}; however, in ], the variant {{lang|es|Méjico}} is used alongside the usual version. According to the {{lang|es|]}} by the ] and ], the version with J is also correct; however, the spelling with X is recommended, as it is the one used in Mexico.<ref>{{lang|es|México}} in {{lang|es|]}} by ] and ], Madrid: Santillana. 2005. ISBN 978-8-429-40623-8.</ref>}} officially the '''United Mexican States''',{{efn|{{langx|es|Estados Unidos Mexicanos}} ({{IPA|es|esˈtaðos uˈniðos mexiˈkanos||Es-mx-Estados Unidos Mexicanos.ogg}}); ]: ''Mēxihcatl Tlacetilīlli Tlahtohcāyōtl'', {{Literal translation|Mexican United States}}}}<!-- Note: The only official name found in documents is "Estados Unidos Mexicanos" NOT "Estados Unidos de México" (which is not formally recognized); they do not mean the same thing so please don't add it. --> is a country in the southern portion of ]. Covering 1,972,550 km<sup>2</sup> (761,610 sq mi),<ref name="cia.gov">{{cite web |url=https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/mexico/ |title=Mexico |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210126164719/https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/mexico |archive-date=26 January 2021 |work=] |publisher=] }}</ref> it is the world's ] by area; with a population of over 130 million, it is the ] country and has the most ] in the world.<ref name="2020 Census">{{cite web |title=Censo Población y Vivienda 2020 |url=https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220214192634/https://www.inegi.org.mx/programas/ccpv/2020/ |archive-date=14 February 2022 |access-date=26 January 2021 |website=inegi.org.mx |publisher=INEGI}}</ref> Mexico is a ] republic comprising ] and ], its capital and ], which is among the ]. The country borders the ] to the north; as well as ] and ] to the southeast. It has maritime borders with the ] to the west, the ] to the southeast, and the ] to the east.<ref>Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary, 3rd ed., Springfield, Massachusetts, United States, Merriam-Webster; p. 733</ref> | |||

| The '''United Mexican States''' (]: ''{{Audio|EUM.ogg|Estados Unidos Mexicanos}}''), or simply '''Mexico''' (]: ''{{Audio|Mexico.ogg|México}}''), is a ] located in ], bounded on the north by the ]; on the south and west by the ]; on the southeast by ], ], and the ]; and on the east by the ]<ref>''Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary'', 3rd ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster, Inc.; p. 733 </ref>. Its capital is ] (''Ciudad de México''), which is one of the largest ] on Earth. | |||

| <!-- Brief history --> | |||

| Covering almost 2 million ]s, Mexico is the 6th largest country in ] by total area and ]. With a population of about 108 million, it is the ] and the most populous Spanish-speaking country in the world. | |||

| Human presence in ] dates back to 8,000 ] as one of six ]. ] hosted civilizations including the ], ], ], ], and ]. ] domination of the area preceded ], which established the colony of ] centered in the former capital, ] (now ]).<ref>], ''The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991. {{ISBN|052139130X}}</ref> The ] in the early 19th century was followed by political and socioeconomic upheaval. The ] resulted in significant ] in 1848.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Greenberg |first=Amy S. |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/818318029 |title=A wicked war : Polk, Clay, Lincoln, and the 1846 U.S. invasion of Mexico |date=2013 |isbn=978-0-307-47599-2 |edition= |location=New York |oclc=818318029 |access-date=5 March 2022 |archive-date=21 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240221140305/https://search.worldcat.org/title/818318029 |url-status=live }}</ref> ] introduced in the ] prompted domestic conflict, ], and the establishment of ], countered by the Republican resistance led by ]. The rise of ]'s dictatorship in the 19th century<ref>Garner, Paul. ''Porfirio Díaz''. Routledge 2001.</ref> sparked the ] in 1910, which led to profound changes, such as the ]. Over the 20th century, Mexico experienced ]; as well as ] and ]. The late 20th century saw a shift towards ] policies, exemplified by the signing of the ] (NAFTA) in 1994, amidst ]. | |||

| <!-- Politics and economy and stats --> | |||

| As the only ]n member of the ] (OECD) since ], Mexico is firmly established as an ]. Elections held in July 2000 marked the first time since 1910 that the opposition defeated the ] (''Partido Revolucionario Institucional'': PRI), and ] of the ] (''Partido Acción Nacional'': PAN) was sworn in as ] on ] ]. The current President is ], also from PAN. | |||

| Mexico is a ] with a ], characterized by a democratic framework and the separation of powers into three branches: ], legislative, and judicial. The federal legislature consists of the ] ], comprising the ], which represents the population, and the ], which provides equal representation for each state. The Constitution establishes three levels of government: the federal Union, the state governments, and the municipal governments. Mexico's federal structure grants autonomy to its 32 states, and its political system is deeply influenced by indigenous traditions and ] ideals. | |||

| Mexico is a ] and ],<ref name="Globalization2">{{Cite book |author=Paweł Bożyk |title=Globalization and the Transformation of Foreign Economic Policy |publisher=Ashgate Publishing |year=2006 |isbn=978-0-7546-4638-9 |page=164 |chapter=Newly Industrialized Countries |access-date=23 July 2018 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iuHsIuez5qoC |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231104053417/https://books.google.com/books?id=iuHsIuez5qoC |archive-date=4 November 2023 |url-status=live}}</ref> with the world's ] and ]. Mexico ranks ] by the number of ] ]s.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204185708/https://whc.unesco.org/en.list|date=4 February 2024}} UNESCO World Heritage sites, accessed 9 May 2022</ref> It is also one of the world's 17 ], ranking fifth in natural ].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/v_ingles/country/whatismegcountry.html|website=Mexican biodiversity|title=What is a mega-diverse country?|access-date=13 July 2019|archive-date=7 September 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190907204954/https://www.biodiversidad.gob.mx/v_ingles/country/whatismegcountry.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> It is a major tourist destination: as of 2022, it is the ], with 42.2 million international arrivals.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://expansion.mx/economia/2018/08/27/mexico-ocupa-el-sexto-lugar-en-turismo-a-nivel-mundial|title=México ocupa el sexto lugar en turismo a nivel mundial|website=www.expansion.mx|publisher=CNN Expansión|access-date=8 January 2019|date=28 August 2018|archive-date=23 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191223165346/https://expansion.mx/economia/2018/08/27/mexico-ocupa-el-sexto-lugar-en-turismo-a-nivel-mundial|url-status=live}}</ref> Mexico's large economy and population, global cultural influence, and steady ] make it a ] and ],<ref>{{cite web |author1=James Scott |author2=Matthias vom Hau |author3=David Hulme |title=Beyond the BICs: Strategies of influence |url=https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:105725&datastreamId=SUPPLEMENTARY-1.DOC&ei=fMKFT7SMKIye8gS71NHACA&usg=AFQjCNHKPFxJk5bu6Qs5R2SKSUs8IwidWw&sig2=_lt4YNVT-1ECYQBh61EWgA |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170525012832/https://www.escholar.manchester.ac.uk/api/datastream?publicationPid=uk-ac-man-scw:105725&datastreamId=SUPPLEMENTARY-1.DOC&ei=fMKFT7SMKIye8gS71NHACA&usg=AFQjCNHKPFxJk5bu6Qs5R2SKSUs8IwidWw&sig2=_lt4YNVT-1ECYQBh61EWgA |archive-date=25 May 2017 |access-date=11 April 2012 |publisher=The University of Manchester}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Nolte |first1=Detlef |date=October 2010 |title=How to compare regional powers: analytical concepts and research topics |url=http://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/38289 |url-status=live |journal=Review of International Studies |volume=36 |issue=4 |pages=881–901 |doi=10.1017/S026021051000135X |jstor=40961959 |s2cid=13809794 |id={{ProQuest|873500719}} |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210302015428/https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/handle/document/38289 |archive-date=2 March 2021 |access-date=17 November 2020| issn = 0260-2105 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Oxford Analytica |url=http://www.oxanstore.com/displayfree.php?NewsItemID=130098 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070424211219/http://www.oxanstore.com/displayfree.php?NewsItemID=130098 |archive-date=24 April 2007 |access-date=17 July 2013}}</ref> increasingly identifying as an ].<ref>{{cite web |date=5 June 2007 |title=G8: Despite Differences, Mexico Comfortable as Emerging Power |url=http://ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=38056 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080816044329/http://www.ipsnews.net/news.asp?idnews=38056 |archive-date=16 August 2008 |access-date=30 May 2010 |publisher=ipsnews.net}}</ref><ref name="Limits2">{{Cite book |author=Mauro F. Guillén |author-link=Mauro F. Guillén |title=The Limits of Convergence |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2003 |isbn=978-0-691-11633-4 |page=126 (table 5.1) |chapter=Multinationals, Ideology, and Organized Labor |access-date=23 July 2018 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CweHgfPIceYC |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240221140236/https://books.google.com/books?id=CweHgfPIceYC |archive-date=21 February 2024 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="AIA2">{{Cite book |author=David Waugh |title=Geography, An Integrated Approach |publisher=Nelson Thornes |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-17-444706-1 |edition=3rd |pages=563, 576–579, 633, and 640 |chapter=Manufacturing industries (chapter 19), World development (chapter 22) |access-date=23 July 2018 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7GH0KZZthGoC |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204185659/https://books.google.com/books?id=7GH0KZZthGoC |archive-date=4 February 2024 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Principles2">{{Cite book |author=N. Gregory Mankiw |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3ojsWuqmorEC |title=Principles of Economics |publisher=Thomson/South-Western |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-324-22472-6 |edition=4th |location=Mason, Ohio |access-date=23 July 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204185536/https://books.google.com/books?id=3ojsWuqmorEC |archive-date=4 February 2024 |url-status=live}}</ref> However, as with much of ], ], ], and ] remain widespread.<ref>{{cite web |title=Global Peace Index 2019: Measuring Peace in a Complex World |url=http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2019/06/GPI-2019-web003.pdf |website=Vision of Humanity |publisher=Institute for Economics & Peace |access-date=4 June 2020 |location=Sydney |date=June 2019 |archive-date=27 August 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190827155045/http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2019/06/GPI-2019-web003.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> Since 2006, an ] between ] syndicates has led to over 127,000 deaths.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-05-31 |title=UCDP - Uppsala Conflict Data Program 2023 |url=https://ucdp.uu.se/year/2023 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240531212552/https://ucdp.uu.se/year/2023 |archive-date=2024-05-31 |access-date=2024-06-18 |website=ucdp.uu.se}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Mexico |url=https://ucdp.uu.se/country/70 |access-date=2021-06-16 |publisher=UCDP – Uppsala Conflict Data Program |website=ucdp.uu.se |archive-date=27 March 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220327051423/https://ucdp.uu.se/country/70 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Opinión: Una guerra inventada y 350,000 muertos en México|date=14 June 2021|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/2021/06/14/mexico-guerra-narcotrafico-calderon-homicidios-desaparecidos/|newspaper=Washington Post|access-date=15 December 2023|archive-date=9 May 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220509091109/https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/2021/06/14/mexico-guerra-narcotrafico-calderon-homicidios-desaparecidos/|url-status=live}}</ref> Mexico is a member of ], the ], the ] (OECD), the ] (WTO), the ] forum, the ], ], and the ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| <!--linked--> | |||

| {{Main|Name of Mexico}} | |||

| {{lang|nah|]}} is the ] term for the heartland of the ], namely the ] and surrounding territories, with its people being known as the ]. It is generally believed that the ] for the valley was the origin of the primary ] for the ], but it may have been the other way around.<ref name="Bright2004">{{cite book|author=William Bright|title=Native American Placenames of the United States|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5XfxzCm1qa4C&pg=PA281|year=2004|publisher=University of Oklahoma Press|isbn=978-0-8061-3598-4|page=281}}</ref> In the colonial era (1521–1821) when Mexico was known as ] this central region became the ]. After New Spain achieved independence from the ] in 1821 and became a sovereign state the Intendency came to be known as the ], with the new country being named after its capital: ]. The country's official name has changed as the ] has changed. The declaration of independence signed on 6 November 1813 by the deputies of the ] called the territory '']'' (Northern America); the 1821 ] also used América Septentrional. On two occasions (1821–1823 and 1863–1867), the country was known as {{lang|es|Imperio Mexicano}} (]). All three federal constitutions (1824, 1857, and 1917, the current constitution) used the name {{lang|es|Estados Unidos Mexicanos}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://ierd.prd.org.mx/coy128/hlb.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081101110558/http://ierd.prd.org.mx/coy128/hlb.htm|archive-date=1 November 2008 |title=El cambio de la denominación de "Estados Unidos Mexicanos" por la de "México" en la Constitución Federal |publisher=ierd.prd.org.mx |access-date=4 November 2009}}</ref>—or the variant {{lang|es|Estados-Unidos Mexicanos}},<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.tlahui.com/politic/politi99/politi8/con1857.htm |title=Constitución Mexicana de 1857 |publisher=www.tlahui.com |access-date=30 May 2010 |archive-date=5 October 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181005022104/http://www.tlahui.com/politic/politi99/politi8/con1857.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> all of which have been translated as "United Mexican States". The phrase {{lang|es|República Mexicana}}, "Mexican Republic", was used in the 1836 ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/01361697524573725088802/p0000001.htm |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130823173543/http://www.cervantesvirtual.com/servlet/SirveObras/01361697524573725088802/p0000001.htm |url-status=dead |archive-date=23 August 2013 |title=Leyes Constitucionales de 1836 |publisher=Cervantesvirtual.com |date=29 November 2010 |access-date=17 July 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|History of Mexico}} | ||

| {{See also|History of the Catholic Church in Mexico|Economic history of Mexico|History of democracy in Mexico|History of Mexico City|Military history of Mexico}} | |||

| For almost three thousand years, ] was the site of several advanced ] civilizations such as the ], the ] and the ]s. In 1519, the native civilizations of what now is known as Mexico were invaded by ]; this was one of the most important conquest campaigns in ]. Two years later in 1521, the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan was conquered by an alliance between Spanish and ], the main enemies of ]. | |||

| ===Indigenous civilizations before European contact (pre-1519)=== | |||

| {{main|Pre-Columbian Mexico|Mesoamerican chronology}} | |||

| ] was the 6th largest city in the world at its peak (1 AD to 500 AD)]] | |||

| ] in the ] of ]]] | |||

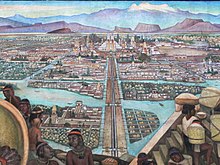

| ], the ] capital and ] at the time. The city was completely destroyed in the 1521 ] and rebuilt as ].]] | |||

| The earliest ] artifacts in Mexico are chips of ]s found near campfire remains in the Valley of Mexico and radiocarbon-dated to circa 10,000 years ago.{{sfn|Werner|2001|pp=386–}} Mexico is the site of the domestication of maize, tomato, and ], which produced an agricultural surplus. This enabled the transition from ] hunter-gatherers to sedentary agricultural villages beginning around 5000 BC.<ref name="EvansWebster2013">{{cite book|author1=Susan Toby Evans|author2=David L. Webster|title=Archaeology of Ancient Mexico and Central America: An Encyclopedia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6ba_AAAAQBAJ&pg=PT54|year=2013|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-136-80186-0|page=54}}</ref> The formative period of Mesoamerica is considered one of the six independent ], this era saw the origin of distinct cultural traits such as religious and symbolic traditions, maize cultivation, artistic and architectural complexes as well as a ] (base 20) numeric system<ref>{{cite book |last1=Diehl |first1=Richard A. |title=The Olmecs: America's First Civilization |date=2004 |publisher=Thames & Hudson |isbn=978-0-500-02119-4 |pages=9–25 }}</ref> that spread from the Mexican cultures to the rest of the ]n cultural area. In this period, villages became more dense in terms of population, becoming socially stratified with an artisan class, and developing into ]s. The most powerful rulers had religious and political power, organizing the construction of large ceremonial centers.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Carmack |first1=Robert M. |last2=Gasco |first2=Janine L. |last3=Gossen |first3=Gary H. |title=The Legacy of Mesoamerica: History and Culture of a Native American Civilization |date=2016 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-34678-4 }}{{page needed|date=December 2020}}</ref> | |||

| The earliest complex civilization in Mexico was the ] culture, which flourished on the Gulf Coast from around 1500 BC. Olmec cultural traits diffused through Mexico into other formative-era cultures in Chiapas, Oaxaca, and the Valley of Mexico.<ref name="MacLachlan">{{cite book|author=Colin M. MacLachlan|title=Imperialism and the Origins of Mexican Culture|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fqdKCAAAQBAJ&pg=PT38|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-28643-6|page=38|date=13 April 2015}}</ref> In the subsequent ], the ] and ] civilizations developed complex centers at ] and ], respectively. During this period the first true ] were developed in the ] and Zapotec cultures. The Mesoamerican writing tradition reached its height in the Classic ], the earliest written histories date from this era. The tradition of writing was important after the Spanish conquest in 1521, with indigenous scribes learning to write their languages in alphabetic letters, while also continuing to create pictorial texts.<ref>], "A History of the New Philology and the New Philology in History", ''Latin American Research Review'' - Volume 38, Number 1, 2003, pp.113–134</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sampson |first1=Geoffrey |title=Writing Systems: A Linguistic Introduction |date=1985 |publisher=Stanford University Press |isbn=978-0-8047-1756-4 }}{{page needed|date=December 2020}}</ref> | |||

| In Central Mexico, the height of the classic period saw the ascendancy of ], which formed a military and commercial empire. Teotihuacan, with a population of more than 150,000 people, had some of the largest ] in the pre-Columbian Americas.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Cowgill |first1=George L. |title=State and Society at Teotihuacan, Mexico |journal=Annual Review of Anthropology |date=21 October 1997 |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=129–161 |doi=10.1146/annurev.anthro.26.1.129 |oclc=202300854 |s2cid=53663189 |s2cid-access=free }}</ref> After the collapse of Teotihuacán around 600 AD, competition ensued between several important political centers in central Mexico such as ] and ]. At this time, during the Epi-Classic, ]s began moving south into Mesoamerica from the North, and became politically and culturally dominant in central Mexico, as they displaced speakers of ]. During the early post-classic era (ca. 1000–1519 AD), Central Mexico was dominated by the ] culture, ] by the ], and the lowland Maya area had important centers at ] and ]. Toward the end of the post-Classic period, the ] (or ]) established dominance, establishing a ] based in the city of ] (modern ]), extending from central Mexico to the border with Guatemala.<ref>{{cite web |website=Ancient Civilizations World |title=Ancient Civilizations of Mexico |url=https://ancientcivilizationsworld.com/mexico/ |date=12 January 2017 |access-date=14 July 2019 |archive-date=12 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190712161602/https://ancientcivilizationsworld.com/mexico/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Spanish conquest and colonial era (1519–1821)=== | |||

| {{Main|Spanish conquest of Mexico|New Spain}} | |||

| ] by ] and his Troops'' (painted in 1848)]] | |||

| Although the ] had established colonies in the ] starting in 1493 the Spanish first learned of Mexico during the ] expedition of 1518. The ] began in February 1519 when ] founded the Spanish city of ]. The 1521 ] and posterior founding of the Spanish capital ] on its ruins was the beginning of a 300-year-long colonial era during which Mexico was known as {{lang|es|Nueva España}} (]). Two factors made Mexico a jewel in the Spanish Empire: the existence of large, hierarchically organized Mesoamerican populations that rendered tribute and performed obligatory labor and the discovery of vast silver deposits in northern Mexico.<ref>] and ]. ''Early Latin America''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983, 59</ref> | |||

| ] was one of the richest and most opulent cities in ]]] | |||

| The ] was created from the remnants of the Aztec empire. The two pillars of Spanish rule were the State and the Roman Catholic Church, both under the authority of the Spanish crown. In 1493 the pope had granted ] to the Spanish monarchy for its overseas empire, with the proviso that the crown spread Christianity in its new realms. In 1524, ] created the ] based in Spain to oversee State power in its overseas territories; in New Spain the crown established a high court in Mexico City, the {{lang|es|]}} ('royal audience' or 'royal tribunal'), and then in 1535 created the ]. The viceroy was the highest official of the State. In the religious sphere, the Diocese of Mexico was created in 1530 and elevated to the ] in 1546, with the archbishop as the head of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Castilian Spanish was the language of rulers. The Catholic faith was the only one permitted, with non-Catholics and Catholics (excluding Indians) holding unorthodox views being subject to the ], established in 1571.<ref>Chuchiak, John F. IV, "Inquisition" in ''Encyclopedia of Mexico''. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 704–708</ref> | |||

| Spanish military forces, sometimes accompanied by native allies, led expeditions to conquer territory or quell rebellions through the colonial era. Notable Amerindian revolts in sporadically populated northern New Spain include the ] (1576–1606),<ref>{{cite web |website=Latino LA: Comunidad |title=The Indigenous People of Zacatecas |url=http://latinola.com/story.php?story=1109 |date=17 July 2003 |access-date=14 July 2019 |last=Schmal |first=John P. |archive-date=14 March 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160314015134/http://latinola.com/story.php?story=1109|url-status=dead}}</ref> ] (1616–1620),<ref>{{cite journal |title=The Tepehuan Revolt of 1616: Militarism, Evangelism, and Colonialism in Seventeenth-Century Nueva Vizcaya |journal=The Americas |volume=58 |issue=2 |pages=302–303 |author=Charlotte M. Gradie |location=Salt Lake City |publisher=University of Utah Press |year=2000 |doi=10.1353/tam.2001.0109 |s2cid=144896113 }}</ref> and the ] (1680), the ] was a regional Maya revolt.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Wasserstrom |first1=Robert |year=1980 |title=Ethnic Violence and Indigenous Protest: The Tzeltal (Maya) Rebellion of 1712 |journal=Journal of Latin American Studies |volume=12 |pages=1–19 |doi=10.1017/S0022216X00017533 |s2cid=145718069 }}</ref> Most rebellions were small-scale and local, posing no major threat to the ruling elites.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Taylor |first1=William B. |title=Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages |date=1 June 1979 |publisher=Stanford University Press |location=Stanford |isbn=978-0804711128 |edition=1st }}</ref> To protect Mexico from the attacks of English, French, and Dutch ]s and protect the Crown's monopoly of revenue, only two ports were open to foreign trade—Veracruz on the Atlantic (connecting to ]) and Acapulco on the Pacific (connecting to the ]). Among the best-known pirate attacks are the 1663 ]<ref>{{cite web |website=In Search of Lost Places |title=Campeche, Mexico – largest pirate attack in history, now UNESCO listed |date=31 January 2017 |access-date=14 July 2019 |last=White |first=Benjamin |url=http://insearchoflostplaces.com/2017/01/campeche-mexico/ |archive-date=15 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190715021345/http://insearchoflostplaces.com/2017/01/campeche-mexico/ |url-status=live }}</ref> and 1683 ].<ref>{{cite web |website=University of Rochester Newsletter |title=The mysterious aftermath of an infamous pirate raid |url=https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/pablo-sierra-silva-mysterious-aftermath-infamous-pirate-raid-287352/ |date=13 December 2017 |access-date=14 July 2019 |first=Sandra |last=Knispel |archive-date=15 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190715021337/https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/pablo-sierra-silva-mysterious-aftermath-infamous-pirate-raid-287352/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Of greater concern to the crown was the issue of foreign invasion, especially after Britain seized in 1762 the Spanish ports of ] and ] in the ]. It created a standing military, increased coastal fortifications, and expanded the northern ]s and ] into ]. The volatility of the urban poor in Mexico City was evident in the 1692 riot in the Zócalo. The riot over the price of maize escalated to a full-scale attack on the seats of power, with the viceregal palace and the archbishop's residence attacked by the mob.<ref name="Cope, R. Douglas 1994">{{cite book |last=Cope |first=R. Douglas |title=The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660–1720 |location=] |publisher=] |date=1994 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Independence era (1808–1855)=== | |||

| {{Main|Mexican War of Independence|First Mexican Empire|First Mexican Republic|Centralist Republic of Mexico|Mexican–American War}} | |||

| ]'s ] on 16 September 1810, by J.J. del Moral. The call to arms marks the beginning of Mexico's War of Independence against Spanish colonial rule.]] | |||

| On 16 September 1810, secular priest ] declared against "bad government" in the small town of ], Guanajuato. This event, known as the ] ({{langx|es|Grito de Dolores}}) is commemorated each year, on 16 September, as Mexico's independence day.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/event/Grito-de-Dolores |title=Grito de Dolores |encyclopedia=] |access-date=12 September 2018 |archive-date=11 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180911171102/https://www.britannica.com/event/Grito-de-Dolores |url-status=live }}</ref> The upheaval in the Spanish Empire that resulted in the independence of most of its New World territories was due to ]'s invasion of Spain in 1808. Hidalgo and some of his soldiers were eventually captured, Hidalgo was defrocked, and they were ] on 31 July 1811. The first 35 years after Mexico's independence were marked by political instability and the changing of the Mexican state from a ] to a fragile federated republic.<ref>Van Young, ''Stormy Passage'', 179–226</ref> There were military coups d'état, foreign invasions, ideological conflict between ] and ], and ]. | |||

| ] in Guanajuato by ]'s army on 28 September 1810, by José Díaz del Castillo]] | |||

| ] to Mexico City on 27 September 1821]] | |||

| Former Royal Army General ] became regent, as newly independent Mexico sought a ] from Europe. When no member of a European royal house desired the position, Iturbide himself was declared Emperor Agustín I. The United States was the first country to recognize Mexico's independence, sending an ambassador to the court and sending a message to Europe via the ] not to intervene in Mexico. The emperor's rule was short (1822–1823) and he was overthrown by army officers in the ].<ref>{{cite journal |author-link=Nettie Lee Benson |last=Benson |first=Nettie Lee |title=The Plan of Casa Mata |journal=] |volume=25 |date=February 1945 |pages=45–56 |doi=10.1215/00182168-25.1.45 }}</ref> After the forced abdication of the monarch, Central America and ] left the union to form the ]. In 1824, the ] was established. Former insurgent General ] became the first president of the republic — the first of many army generals to hold the presidency. In 1829, former insurgent general and fierce Liberal ], a signatory of the ] that achieved independence, became president in a disputed election. During his short term in office, from April to December 1829, he abolished slavery.<ref>{{Cite book |author-link=Charles A. Hale |last=Hale |first=Charles A. |title=Mexican Liberalism in the Age of Mora |location=] |publisher=] |date=1968 |page=224 }}</ref> His Conservative vice president, former Royalist General ], led a coup against him and Guerrero was ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |url=https://www.britannica.com/blackhistory/article-24160 |title=Ways of ending slavery |encyclopedia=] |access-date=23 June 2022 |archive-date=16 October 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141016025606/http://www.britannica.com/blackhistory/article-24160 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Mexico's ability to maintain its independence and establish a viable government was in question. Spain ] its former colony during the 1820s but eventually recognized its independence. France attempted to recoup losses it claimed for its citizens during Mexico's unrest and blockaded the Gulf Coast during the so-called ] of 1838–1839.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Costeloe |first=Michael P. |chapter=Pastry War |title=] |volume=4 |page=318 }}</ref> General ] emerged as a national hero because of his role in both these conflicts; Santa Anna came to dominate the politics for the next 25 years, often known as the "Age of Santa Anna", until his overthrow in 1855.<ref>Van Young, ''Stormy Passage'', "The Age of Santa Anna", 227–270</ref> | |||

| ] (1836), between the Mexican army led by President ] and American troops.]] | |||

| Mexico also contended with indigenous groups that controlled the territory that Mexico claimed in the north. For example, the ] controlled a ] in sparsely populated central and northern Texas.<ref>Weber, David J., ''The Mexican Frontier, 1821–1846: The American Southwest under Mexico,'' University of New Mexico Press, 1982</ref> Wanting to stabilize and develop that area — and as few people from central Mexico had chosen to resettle to this remote and hostile territory — the Mexican government encouraged ] immigration into present-day Texas, a region that bordered that United States. Mexico by law was a Catholic country; the Anglo-Americans were primarily Protestant English speakers from the southern United States. Some brought their black slaves, which after 1829 was contrary to Mexican law. In 1835, Santa Anna sought to centralize government rule in Mexico, suspending the 1824 constitution and promulgating the ], which placed power in his hands. As a result, civil war spread across the country. Three new governments declared independence: the ], the ] and the ].<ref name="miranda">{{cite book |author=Angel Miranda Basurto |title=La Evolucíon de Mėxico |publisher=Editorial Porrúa |year=2002 |location=Mexico City |edition=6th |isbn=970-07-3678-4 |page=358 |language=es |trans-title=The Evolution of Mexico }}</ref>{{rp|129–137}} The largest blow to Mexico was the U.S. invasion of Mexico in 1846 in the ]. Mexico lost much of its sparsely populated northern territory, sealed in the 1848 ]. Despite that disastrous loss, Santa Anna returned to the presidency yet again before being ousted and exiled in the Liberal ]. | |||

| ===Liberal era (1855–1911)=== | |||

| {{Main|Second Mexican Republic|La Reforma|Second Mexican Empire|Restored Republic (Mexico)|Porfiriato}} | |||

| ]. Known for his efforts to modernize the country, defend its sovereignty, and promote liberal reforms, especially during the mid-19th century.]] | |||

| The overthrow of Santa Anna and the establishment of a civilian government by Liberals allowed them to enact laws that they considered vital for Mexico's economic development. The ] attempted to modernize Mexico's economy and institutions along liberal principles. They promulgated a new ], separating Church and State, stripping the Church and the military of their special privileges ({{lang|es|]}}); mandating the sale of Church-owned property and sale of indigenous community lands, and secularizing education.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Britton |first=John A. |chapter=Liberalism |title=] |page=739 }}</ref> Conservatives revolted, touching off ] between rival Liberal and Conservative governments (1858–1861). | |||

| The Liberals defeated the Conservative army on the battlefield, but Conservatives sought another solution to gain power via foreign intervention by the French, asking Emperor ] to place a European monarch as head of state in Mexico. The French Army defeated the Mexican Army and placed ] on the ] of Mexico, supported by Mexican Conservatives and propped up by the French Army. The Liberal Republic under ] was a government in internal exile, but with the end of the Civil War in the United States in April 1865, the Reunified U.S. government began aiding the Mexican Republic. Two years later, the French Army withdrew its support, but Maximilian remained in Mexico. Republican forces captured him and he was executed. The "Restored Republic" saw the return of Juárez, "the personification of the embattled republic,"<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Hamnett |first=Brian |chapter=Benito Juárez |title=] |pages=719–20 }}</ref> as president. | |||

| The Conservatives had been not only defeated militarily but also discredited politically for their collaboration with the French invaders and Liberalism became synonymous with patriotism.<ref>Britton, "Liberalism" p. 740.</ref> The Mexican Army that had its roots in the colonial royal army and then the army of the early republic was destroyed and new military leaders had emerged from the War of the Reform and the conflict with the French, most notably ], a hero of the {{lang|es|]}}, who now sought civilian power and challenged Juárez on his re-election in 1867. Díaz then rebelled but was crushed by Juárez. Having won re-election, Juárez died in office in July 1872, and Liberal ] became president, declaring a "religion of the state" for the rule of law, peace, and order. When Lerdo ran for re-election, Díaz rebelled against the civilian president, issuing the ]. Díaz had more support and waged guerrilla warfare against Lerdo. On the verge of Díaz's victory on the battlefield, Lerdo fled from office into exile.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Sullivan |first=Paul |chapter=Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada |title=] |pages=736–38 }}</ref> | |||

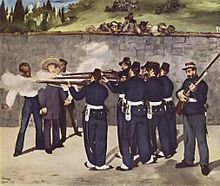

| ]'', 19 June 1867. Gen. ], left; Maximiian, center; Gen. ], right. Painting by ] 1868]] | |||

| After the turmoil in Mexico from 1810 to 1876, the 35-year rule of Liberal General ] (r.1876–1911) allowed Mexico to rapidly modernize in a period characterized as one of "]". The ] was characterized by economic stability and growth, significant foreign investment and influence, an expansion of the ] and telecommunications, and investments in the arts and sciences.<ref>{{cite web |website=Inside Mexico.com |url=https://www.inside-mexico.com/el-porfiriato-en-mexico/ |title=El Porfiriato en Mexico |date=2 February 2018 |access-date=18 July 2019 |author=Adela M. Olvera |language=es |trans-title=The Porfirio Era in Mexico |archive-date=26 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190326165321/https://www.inside-mexico.com/el-porfiriato-en-mexico/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Díaz ruled with a group of advisors that became known as the {{lang|es|]s}} ('scientists').<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Buchenau |first=Jürgen |chapter=Científicos |title=] |pages=260–265 }}</ref> The most influential {{lang|es|científico}} was Secretary of Finance ].<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=Schmidt |first=Arthur |chapter=José Ives Limantour |title=] |pages=746–49 }}</ref> The Porfirian regime was influenced by ].<ref name="cientifico">{{cite encyclopedia |chapter=cientifico |chapter-url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/cientifico |title=] |access-date=7 February 2017 |language=en |archive-date=7 February 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170207113443/https://www.britannica.com/topic/cientifico |url-status=live }}</ref> They rejected theology and ] in favor of scientific methods being applied towards national development. An integral aspect of the liberal project was secular education. The Díaz government led a protracted ] that culminated with the forced relocation of thousands of ] to Yucatán and Oaxaca. As the centennial of independence approached, Díaz gave an ] where he said he was not going to run in the 1910 elections, when he would be 80. Political opposition had been suppressed and there were few avenues for a new generation of leaders. But his announcement set off a frenzy of political activity, including the unlikely candidacy of the scion of a rich landowning family, ]. Madero won a surprising amount of political support when Díaz changed his mind and ran in the election, jailing Madero. The September centennial celebration of independence was the last celebration of the ]. The Mexican Revolution starting in 1910 saw a decade of civil war, the "wind that swept Mexico."<ref>{{cite book |last1=Brenner |first1=Anita |title=The Wind that Swept Mexico: The History of the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1942 |date=1 January 1984 |publisher=University of Texas Press |isbn=978-0292790247 |edition=New }}</ref> | |||

| ===Mexican Revolution (1910–1920)=== | |||

| {{Main|Mexican Revolution}} | |||

| ], who challenged Díaz in the fraudulent 1910 election and was elected president when Díaz was forced to resign in May 1911]] | |||

| The ] was a decade-long transformational conflict.<ref>Benjamin, Thomas. ''La Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History''. Austin: University of Texas Press 2000</ref> It began with scattered uprisings against President Díaz after the fraudulent 1910 election, his resignation in May 1911, demobilization of rebel forces, an interim presidency of a member of the old guard and the democratic election of a rich, civilian landowner, ] in fall 1911. In ], a military coup d'état overthrew Madero's government, with the support of the U.S., resulting in Madero's murder by agents of ] General ]. During the Revolution, the U.S. Republican administration of ] supported the Huerta coup against Madero, but when Democrat ] was inaugurated as president in March 1913, Wilson refused to recognize Huerta's regime and allowed arms sales to the Constitutionalists. Wilson ordered troops to ] the strategic port of Veracruz in 1914, which was lifted.<ref>{{cite web|website=Library of Congress|title=The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of Congress, U.S. Involvement Before 1913|url=http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/us-involvement-before-1913.html|access-date=18 July 2019|archive-date=19 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190719051634/http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/mexican-revolution-and-the-united-states/us-involvement-before-1913.html|url-status=live}}</ref> A coalition of anti-Huerta forces in the North, the ] led by ] ], and a peasant army in the South under ] defeated the Federal Army in 1914, leaving only revolutionary forces.<ref name="Matute"/> | |||

| Following the revolutionaries' victory against Huerta, they sought to broker a peaceful political solution, but the coalition splintered, plunging Mexico again into a civil war. Constitutionalist general ], commander of the Division of the North, broke with Carranza and allied with Zapata. Carranza's best general ] defeated Villa, his former comrade-in-arms, in the ] in 1915, and Villa's northern forces melted away. Carranza became the de facto head of Mexico, and the U.S. recognized his government<ref name="Matute"/> while Zapata's forces in the south reverted to guerrilla warfare. After Pancho Villa was defeated by revolutionary forces in 1915, he led an incursion raid into ], prompting the U.S. to send ] led by General ] in an unsuccessful attempt to capture Villa. Carranza pushed back against U.S. troops being in northern Mexico. The expeditionary forces withdrew as the U.S. entered World War I.<ref>{{cite web|website=U.S. Department of State archive|date=20 January 2009|access-date=18 July 2019|title=Punitive Expedition in Mexico, 1916–1917|url=https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwi/108653.htm|archive-date=15 June 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230615184624/https://2001-2009.state.gov/r/pa/ho/time/wwi/108653.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> Although often viewed as an internal conflict, the revolution had significant international elements:<ref>]. ''The Secret War in Mexico''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.</ref> Germany attempted to get Mexico to side with it, sending a coded ] in 1917 to incite war between the U.S. and Mexico, with Mexico to regain the territory it lost in the Mexican-American War<ref>{{cite web|website=The National WWI Museum and Memorial|url=https://www.theworldwar.org/explore/centennial-commemoration/us-enters-war/zimmermann-telegram|title=ZIMMERMANN TELEGRAM|access-date=18 July 2019|date=2 March 2017|archive-date=19 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190719051644/https://www.theworldwar.org/explore/centennial-commemoration/us-enters-war/zimmermann-telegram|url-status=live}}</ref> but Mexico remained neutral in the conflict. | |||

| ], ] and ] in the ] during the ], 1914]] | |||

| In 1916, the winners of the Mexican revolution met at a constitutional convention to draft the ], which was ratified in February 1917. The Constitution empowered the government to expropriate resources including land, gave rights to labor, and strengthened anticlerical provisions of the 1857 Constitution.<ref name="Matute">Matute, Alvaro. "Mexican Revolution: May 1917 – December 1920" in '']'', 862–864.</ref> With amendments, it remains the governing document of Mexico. It is estimated that the revolutionary war killed 900,000 people out of Mexico's 15 million population at the time.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/investigations/505_mexicanrevolution.html |title=The Mexican Revolution |publisher=Public Broadcasting Service |date=20 November 1910 |access-date=17 July 2013 |archive-date=14 May 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514205614/http://www.pbs.org/opb/historydetectives/investigations/505_mexicanrevolution.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.hist.umn.edu/~rmccaa/missmill/ |title=Missing millions: the human cost of the Mexican Revolution |author=Robert McCaa |publisher=University of Minnesota Population Center |access-date=17 July 2013 |archive-date=2 April 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160402165542/http://www.hist.umn.edu/~rmccaa/missmill/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Consolidating power, President Carranza had peasant leader Emiliano Zapata assassinated in 1919. Carranza had gained the support of the peasantry during the Revolution, but once in power, he did little to institute land reform, which had motivated many to fight in the Revolution. Carranza returned some confiscated land to their original owners. President Carranza's best general, Obregón, served briefly in his administration but returned to his home state of Sonora to position himself to run in the 1920 presidential election. Since Carranza could not run for re-election, he chose a civilian to succeed him, intending to remain the power behind the presidency. Obregón and two other Sonoran revolutionary generals drew up the ], overthrowing Carranza, who died fleeing Mexico City in 1920. General ] became interim president, followed by the election of General ]. | |||

| ===Political consolidation and one-party rule (1920–2000)=== | |||

| {{Further|Maximato|Institutional Revolutionary Party}} | |||

| ], the ruler of the '']'' and the founder of the ], that held uninterrupted power in the country from 1929 to 2000]] | |||

| The first quarter-century of the post-revolutionary period (1920–1946) was characterized by revolutionary generals serving as ], including ] (1920–24), ] (1924–28), ] (1934–40), and ] (1940–46). The post-revolutionary project of the Mexican government sought to bring order to the country, end military intervention in politics, and create organizations of interest groups. Workers, peasants, urban office workers, and even the army for a short period were incorporated as sectors of the single party that dominated Mexican politics from its founding in 1929. Obregón instigated land reform and strengthened the power of organized labor. He gained recognition from the United States and took steps to ] with companies and individuals that lost property during the Revolution. He imposed his fellow former Sonoran revolutionary general, Calles, as his successor, prompting an unsuccessful military revolt. As president, Calles provoked a ] with the ] and Catholic guerrilla armies when he strictly enforced anticlerical articles of the 1917 Constitution which ended with an agreement. Although the constitution prohibited the reelection of the president, Obregón wished to run again and the constitution was amended to allow non-consecutive re-election; he won the 1928 elections but was assassinated by a Catholic activist, causing a political crisis of succession. Calles could not become president again, so he sought to set up a structure to manage presidential succession, founding the ], which went on to dominate Mexico for the rest of the 20th century.<ref>{{cite web |website=Instituto Nacional de Estudios Historicos de las Revoluciones de Mexico |url=https://inehrm.gob.mx/es/inehrm/Articulo_85_aniversario_de_la_Fundacion_del_Partido_Nacional_Revolucionario_PNR |title=85º Aniversario de la Fundación del Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PNR) |access-date=18 July 2019 |language=es |trans-title=85th anniversary of the founding of the National Revolutionary Party (PRN) |author=Rafael Hernández Ángeles |archive-date=19 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190719051635/https://inehrm.gob.mx/es/inehrm/Articulo_85_aniversario_de_la_Fundacion_del_Partido_Nacional_Revolucionario_PNR |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Despite not holding the presidency, Calles remained the key political figure during the period known as the ] (1929–1934), that ended during the presidency of ], who expelled Calles from the country and implemented many economic and social reforms. This included the ] in March 1938, which nationalized the U.S. and Anglo-Dutch oil company known as the ], which would result in the creation of the state-owned ]. Cárdenas's successor, ] (1940–1946) was more moderate, and relations between the U.S. and Mexico vastly improved during ], when Mexico was a significant ally. From 1946 the election of ], the first civilian president in the post-revolutionary period, Mexico embarked on an aggressive program of economic development, known as the ], which was characterized by industrialization, urbanization, and the increase of inequality between urban and rural areas.<ref>{{cite web |title=The Mexican Miracle: 1940–1968 |work=World History from 1500 |publisher=Emayzine |url=http://www.emayzine.com/lectures/mex9.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070403000322/http://www.emayzine.com/lectures/mex9.html |archive-date=3 April 2007 |access-date=30 September 2007}}</ref> The ], a technological movement that led to a significant worldwide increase in crop production, began in the ] of Sonora in the middle of the 20th century.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Staff |first1=M. N. D. |title=He left India for Mexico to solve global hunger: Meet Ravi Singh |url=https://mexiconewsdaily.com/india/he-left-india-for-mexico-to-solve-global-hunger-meet-ravi-singh/ |website=Mexico News Daily |access-date=14 March 2024 |date=13 March 2024 |quote=...specifically the Yaqui Valley in Sonora... is considered the birthplace of the Green Revolution. |archive-date=14 March 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240314062320/https://mexiconewsdaily.com/india/he-left-india-for-mexico-to-solve-global-hunger-meet-ravi-singh/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] during the ]]] | |||

| With robust economic growth, Mexico sought to showcase it to the world by hosting the ]. The government poured huge resources into building new facilities, prompting political unrest among university students and others. Demonstrations in central Mexico City went on for weeks before the planned opening of the games, with the government of ] cracking down. The culmination was the ],<ref name=MMex>{{Cite book |title=Massacre in Mexico |author=Elena Poniatowska |publisher=Viking, New York |year=1975 |isbn=978-0-8262-0817-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=CmnDdj7eP-wC |author-link=Elena Poniatowska|access-date=23 July 2018 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204185551/https://books.google.com/books?id=CmnDdj7eP-wC |url-status=live }}</ref> which killed around 300 protesters based on conservative estimates and perhaps as many as 800.<ref>{{cite news |last=Kennedy |first=Duncan |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/7513651.stm |title=Mexico's long forgotten dirty war |work=BBC News |date=19 July 2008 |access-date=17 July 2013 |archive-date=29 June 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170629110724/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/7513651.stm |url-status=live }}</ref> Although the economy continued to flourish for some, ] remained a factor of discontent. PRI rule became increasingly authoritarian and at times oppressive in what is now referred to as the ].<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Krauze |first=Enrique |title=Furthering Democracy in Mexico |date=January–February 2006 |magazine=] |url=http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20060101faessay85106/enrique-krauze/furthering-democracy-in-mexico.html? |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060110074536/http://www.foreignaffairs.org/20060101faessay85106/enrique-krauze/furthering-democracy-in-mexico.html |archive-date=10 January 2006 |access-date=7 October 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| ] (Mexico), President ] (U.S.), and Prime Minister ] (Canada).]] | |||

| In the 1980s the first cracks emerged in the PRI's complete political dominance. In ], the ] was elected as governor. When De la Madrid chose ] as the candidate for the PRI, and therefore a foregone presidential victor, ], son of former President ], broke with the PRI and challenged Salinas in the 1988 elections. In 1988 there was massive ], with results showing that Salinas had won the election by the narrowest percentage ever. There were massive protests in Mexico City over the stolen election. Salinas took the oath of office on 1 December 1988.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.photius.com/countries/mexico/government/mexico_government_the_1988_elections.html |title="Mexico The 1988 Elections" (Sources: The Library of the Congress Country Studies, CIA World Factbook) |publisher=Photius Coutsoukis |access-date=30 May 2010 |archive-date=15 September 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180915102322/https://www.photius.com/countries/mexico/government/mexico_government_the_1988_elections.html |url-status=live }}</ref> In 1990 the PRI was famously described by ] as the "perfect dictatorship", but by then there had been major challenges to the PRI's hegemony.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://theconversation.com/massacres-disappearances-and-1968-mexicans-remember-the-victims-of-a-perfect-dictatorship-104196 |last=Gomez Romero |first=Luis |title=Massacres, disappearances and 1968: Mexicans remember the victims of a 'perfect dictatorship' |date=5 October 2018 |website=The Conversation |access-date=12 May 2019 |archive-date=12 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190512234050/http://theconversation.com/massacres-disappearances-and-1968-mexicans-remember-the-victims-of-a-perfect-dictatorship-104196 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://elpais.com/diario/1990/09/01/cultura/652140001_850215.html |title=Vargas Llosa: "México es la dictadura perfecta" |date=1 September 1990 |newspaper=El País |access-date=12 May 2019 |archive-date=24 October 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111024235439/http://www.elpais.com/articulo/cultura/AZUA/_FELIX_DE/TRIAS/_EUGENIO/VARGAS_LLOSA/_MARIO/MARSE/_JUAN_/ESCRITOR/PAZ/_OCTAVIO/SARAMAGO/elpepicul/19900901elpepicul_1/Tes |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Reding |first=Andrew |year=1991 |title=Mexico: The Crumbling of the "Perfect Dictatorship" |jstor=40209208 |journal=World Policy Journal |volume=8 |issue=2 |pages=255–284}}</ref> | |||

| Salinas embarked on a program of ] reforms that fixed the exchange rate of the peso, controlled inflation, opened Mexico to foreign investment, and began talks with the U.S. and Canada to join their ], which culminated in the ] (NAFTA) on 1 January 1994; the same day, the ] (EZLN) in Chiapas began armed peasant rebellion against the federal government, which captured a few towns but brought world attention to the situation in Mexico. The armed conflict was short-lived and has continued as a non-violent opposition movement against ] and ]. In 1994, following the assassination of the PRI's presidential candidate ], Salinas was succeeded by victorious PRI candidate ]. Salinas left Zedillo's government to deal with the ], requiring a $50 billion ] bailout. Major macroeconomic reforms were started by Zedillo, and the economy rapidly recovered and growth peaked at almost 7% by the end of 1999.<ref>{{cite web |last=Cruz Vasconcelos |first=Gerardo |title=Desempeño Histórico 1914–2004 |url=http://www.imef.org.mx/NR/rdonlyres/F722BEDD-A8DE-49BA-AF4F-1A00889CE618/1192/CAPITULOI1.pdf |access-date=17 February 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060703181721/http://www.imef.org.mx/NR/rdonlyres/F722BEDD-A8DE-49BA-AF4F-1A00889CE618/1192/CAPITULOI1.pdf |archive-date=3 July 2006 |language=es }}</ref> | |||

| ===Contemporary Mexico=== | |||

| ], the father of the Mexican independence.]] | |||

| ] won the ] and became the first president not from the ] since 1929, and the first elected from an opposition party since ] in 1911.]] | |||

| On ], ], the independence from Spain was declared by ] in the small town of Dolores, causing a long ] that eventually led to recognized independence in ] and the creation of the ] with ] being the first and only emperor. In ], the new republic proclaimed ] as its first President. During the first decades of its independence, ] was the strong man of Mexican politics, and on-and-off dictator. After Santa Anna revoked the federal constitution, ] declared its independence, which they managed to obtain in ]. The annexation of Texas by the ] created a ], that would cause the ]. This war resulted in a Mexican defeat. In the ] of ] Mexico lost one third of its area to the United States. | |||

| After 71 years of rule, the incumbent PRI lost the ] to ] of the opposing conservative ] (PAN). In the ], ] from the PAN was declared the winner, with a very narrow margin (0.58%) over leftist politician ] of the ] (PRD).<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Valles Ruiz |first1=Rosa María |title=Elecciones presidenciales 2006 en México. La perspectiva de la prensa escrita |trans-title=2006 presidential Elections in Mexico. The Perspective of the Press |language=es |journal=Revista mexicana de opinión pública |date=June 2016 |issue=20 |pages=31–51 |url=http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2448-49112016000100031 |access-date=12 July 2019 |archive-date=21 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200321091207/http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2448-49112016000100031 |url-status=live }}</ref> López Obrador, however, ] and pledged to create an "alternative government".<ref>{{cite journal|last=Reséndiz|first=Francisco|title=Rinde AMLO protesta como "presidente legítimo"|journal=El Universal|year=2006|url=http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/389114.html|language=es|access-date=1 October 2007|archive-date=18 January 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120118162332/http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/389114.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| Dissatisfaction with Santa Anna's rule led to the ] ], beginning an era of liberal reforms, known as the '']''. In the ] the country again suffered a military occupation, this time by ], seeking to establish the ] Archduke ] as Emperor of Mexico, with support from the Catholic clergy and conservative ]s. This ] was fought off by then president of the Republic, the ] Indian ], who managed to restore the republic in ]. | |||

| After twelve years, in the ], the PRI again won the presidency with the election of ]. However, he won with a plurality of around 38% and did not have a legislative majority.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/mexico/9369278/Enrique-Pena-Nieto-wins-Mexican-presidential-election.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/centralamericaandthecaribbean/mexico/9369278/Enrique-Pena-Nieto-wins-Mexican-presidential-election.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live|title=Enrique Pena Nieto wins Mexican presidential election|date=2 July 2012|work=The Telegraph|access-date=25 August 2015}}{{cbignore}}</ref> | |||

| ], a republican general during the French intervention, assumed power in ]. The period of his rule is known as the '']'', which was noted by remarkable economic achievements but also by brutal oppression. The latter led to the ] in ], initially led by ]. Madero was overthrown and murdered in ] by the reactionary general ]. This caused a civil war, with such as ] and ]. The Revolution calmed down when the ] was proclaimed by ]. Carranza was killed in ] and succeeded by ], who in turn was succeeded by ]. In ] Obregón was reelected, but assassinated before he could assume power. This led Calles to found the National Revolutionary Party (PNR), which was later renamed to ] (PRI). | |||

| During the twenty-first century, Mexico has contended with ], ], ], and a stagnant economy. Many state-owned industrial enterprises were privatized starting in the 1990s with ] reforms, but ], the state-owned petroleum company is only slowly being privatized, with exploration licenses being issued.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Sharma |first1=Gaurav |title=Mexico's Oil And Gas Industry Privatization Efforts Nearing Critical Phase |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/gauravsharma/2018/05/10/mexicos-oil-and-gas-industry-privatization-efforts-nearing-critical-phase/ |access-date=4 June 2020 |work=Forbes |date=10 May 2018 |archive-date=4 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200604081840/https://www.forbes.com/sites/gauravsharma/2018/05/10/mexicos-oil-and-gas-industry-privatization-efforts-nearing-critical-phase/ |url-status=live }}</ref> In a push against government corruption, the ex-CEO of Pemex, ], was arrested in 2020.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Barrera Diaz |first1=Cyntia |last2=Villamil |first2=Justin |last3=Still |first3=Amy |title=Pemex Ex-CEO Arrest Puts AMLO in Delicate Situation |url=https://www.rigzone.com/news/wire/pemex_exceo_arrest_puts_amlo_in_delicate_situation-14-feb-2020-161099-article/ |access-date=4 June 2020 |work=Rigzone |agency=Bloomberg |date=14 February 2020 |archive-date=27 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200527071038/https://www.rigzone.com/news/wire/pemex_exceo_arrest_puts_amlo_in_delicate_situation-14-feb-2020-161099-article/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| During the next four decades, Mexico experienced impressive economic growth; some historians call this period "El Milagro Mexicano", the Mexican Miracle. This was in spite of falling foreign confidence in investment during the worldwide ]. The assumption of mineral rights and subsequent nationalization of the oil industry into ] during the presidency of ] was a popular move that sparked a diplomatic crisis with those countries whose citizens had lost businesses expropriated by the Cárdenas government. | |||

| After founding the new political party ], Andrés Manuel López Obrador (commonly known as AMLO) won the 2018 presidential election with over 50% of the vote. His political coalition, led by his left-wing party founded after the 2012 elections, included parties and politicians from across the political spectrum. The coalition also won a majority in both the upper and lower Congress chambers. His success is attributed to the country's opposing political forces exhausting their chances as well as AMLO's adoption of a moderate discourse with a focus on reconciliation.<ref>{{cite news |last=Sieff |first=Kevin |title=López Obrador, winner of Mexican election, given broad mandate |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/lopez-obrador-a-leftist-wins-sweeping-mandate-in-mexican-presidential-election/2018/07/02/4c5e1de4-7be3-11e8-ac4e-421ef7165923_story.html |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180702170755/https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/the_americas/lopez-obrador-a-leftist-wins-sweeping-mandate-in-mexican-presidential-election/2018/07/02/4c5e1de4-7be3-11e8-ac4e-421ef7165923_story.html |archive-date=2 July 2018 |access-date=2 July 2018 |newspaper=Washington Post}}</ref> The first confirmed case of ] occurred on 28 February 2020. The ] began in December 2020. | |||

| Although the economy flourished, the PRI rule became increasingly more oppressive, culminating in the ] of ], where 250 protesters were killed by security forces. In the 1970s, discontent with the administration of ] brought the country on the brink of a civil war. The chronic weakness of Mexico's economy in the 1970s and 1980s included ] ] and price ], creating a strong need for tens of millions of poor Mexicans to migrate north to the ]. In ], the Mexican government announced that it could no longer pay its debts. The first cracks in the monopoly position of PRI began to appear in ], when the party had to resort to ] in order to prevent leftist opposition candidate ] from winning the elections. ] was declared victor of the elections and embarked on a program of ] reforms, culminating in the ] (NAFTA) of ]. However, the very same day Mexico joined the NAFTA, the ] (EZLN) began an armed rebellion against the federal government. A series of political assassination and corruption scandals further damaged Salinas' reputation. In December ], a month after Salinas was succeeded by ], the ] led to a new economical crisis. | |||

| ], López Obrador's political successor, won the ] in a landslide and upon taking office in October became the first woman to lead the country in Mexico's history.<ref name="france24.com">{{Cite web |url=https://www.france24.com/en/americas/20240603-sheinbaum-set-to-win-mexico-election-becoming-first-female-president |title=Ruling leftist party candidate Sheinbaum elected Mexico's first female president |date=3 June 2024 |access-date=3 June 2024 |archive-date=3 June 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240603063457/https://www.france24.com/en/americas/20240603-sheinbaum-set-to-win-mexico-election-becoming-first-female-president |url-status=live }}</ref> She was sworn in as Mexico's president on 1 October 2024.<ref>{{cite news |title=Claudia Sheinbaum sworn in as 1st female president of Mexico |url=https://apnews.com/article/mexico-president-claudia-sheinbaum-7d3599b39a7298df46e7eda34d80afee |work=AP News |date=1 October 2024 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Democratic reforms under Zedillo caused the PRI to lose its majority in ] in ]. In ], after 71 years, the PRI lost a presidential election to ] of the ] (PAN). In ], ] (PAN) was declared winner of ] with a razor-thin margin over ] of the ] (PRD). López Obrador however claimed the election was stolen, and pledged to create an alternative government. | |||

| ==Geography== | ==Geography== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Geography of Mexico}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] of Mexico]] | |||

| Mexican territory includes the more remote ] and the ] in the Pacific Ocean. Mexico's total area covers 1,972,550 square kilometers, including approximately 6,000 square kilometers of islands in the Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Mexico, Caribbean Sea, and ] (see fig. 3). On its north, Mexico shares a 5000-kilometer border with the United States. The meandering Río Bravo del Norte (known as the ] in the United States) defines the border from ] east to the ]. A series of natural and artificial markers delineate the United States-Mexican border west from Ciudad Juárez to the ]. On its south, Mexico shares an 871 kilometer border with Guatemala and a 251-kilometer border with ]. | |||

| ], the highest mountain in Mexico]] | |||

| Mexico is located between latitudes ] and ], and longitudes ] and ] in the southern portion of North America, with a total area of {{convert|1972550|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on}}, is the ]. It has coastlines on the ] and ], as well as the ] and ], the latter two forming part of the ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MuN7xR6wR-4C&pg=PA405 |page=405 |last=Vargas |first=Jorge A. |title=Mexico and the Law of the Sea: Contributions and Compromises |year=2011 |publisher=Martinus Nijhoff Publishers |isbn=9789004206205 |access-date=25 September 2020 |archive-date=4 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240204185531/https://books.google.com/books?id=MuN7xR6wR-4C&pg=PA405#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> Within these seas are about {{convert|6000|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=on}} of islands (including the remote Pacific ] and the ]). Almost all of Mexico lies in the ], with small parts of the ] on the ] and ]s. ], some geographers include the territory east of the ] (around 12% of the total) within Central America.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.grec.cat/ |archive-url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20160515192216/http://www.grec.cat/ |url-status=dead |archive-date=15 May 2016 |title=Nord-Amèrica, in Gran Enciclopèdia Catalana |publisher=Grec.cat |access-date=17 July 2013 }}</ref> ], however, Mexico is entirely considered part of North America, along with Canada and the United States.<ref>{{cite book |last=Parsons |first=Alan |author2=Jonathan Schaffer |title=Geopolitics of oil and natural gas |publisher=U.S. Department of State |series=Economic Perspectives |date=May 2004}}</ref> | |||

| The majority of Mexican central and northern territories are located at high altitudes, and as such the highest elevations are found at the ] which crosses Mexico east to west: ] ({{convert|5700|m|ft|0|disp=or|abbr=on}}), ] ({{convert|5462|m|ft|0|disp=or|abbr=on}}) and ] ({{convert|5286|m|ft|0|disp=or|abbr=on}}) and the ] ({{convert|4577|m|ft|0|disp=or|abbr=on}}). Two mountain ranges known as ] and ], which are the extension of the ] from northern North America crossed the country from north to south and a fourth mountain range, the ], runs from ] to ]. The Mexican territory is prone to ].<ref name="ciageo"/> | |||