| Revision as of 02:03, 2 May 2008 view sourceWordbuilder (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers19,066 editsm →Fire protection and prevention: "Codes" --> "codes"← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 01:27, 15 January 2025 view source The Kornephoros (talk | contribs)32 editsm Add link →Human control of fire | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Rapid and hot oxidation of a material}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=June 2007}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Other uses}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}} | |||

| ] Airmen from the 20th Civil Engineer Squadron Fire Protection Flight neutralize a live fire during a field training exercise.]] | |||

| {{Pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{CS1 config|mode=cs1}} | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=April 2023}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| '''Fire''' is the rapid ] of a material (the ]) in the ] chemical process of ], releasing ], ], and various reaction ].<ref>{{Citation |title=Glossary of Wildland Fire Terminology |date=October 2007 |url=http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/pubs/glossary/pms205.pdf |journal= |pages=70 |access-date=2008-12-18 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080821230940/http://www.nwcg.gov/pms/pubs/glossary/pms205.pdf |url-status=deviated |publisher=National Wildfire Coordinating Group |archive-date=2008-08-21}}</ref>{{efn|Slower oxidative processes like ] or ] are not included by this definition.}} | |||

| '''Fire''' is the ] and ] released during a ], in particular a ]. Depending on the substances alight, and any impurities within, the ] of the ] and the fire ] might vary. | |||

| At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames are produced. The '']'' is the visible portion of the fire. Flames consist primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, oxygen and nitrogen. If hot enough, the gases may become ionized to produce ].<ref>{{cite web | url = http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemistryfaqs/f/firechemistry.htm | title = What is the State of Matter of Fire or Flame? Is it a Liquid, Solid, or Gas? | publisher = About.com | access-date = 2009-01-21 | last = Helmenstine | first = Anne Marie | archive-date = 24 January 2009 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090124152217/http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemistryfaqs/f/firechemistry.htm | url-status = dead }}</ref> Depending on the substances alight, and any impurities outside, the ] of the flame and the fire's ] will be different.<ref>{{cite web | url = http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemistryfaqs/f/firechemistry.htm | title = What is the State of Matter of Fire or Flame? Is it a Liquid, Solid, or Gas? | publisher = About.com | access-date = 2009-01-21 | last = Helmenstine | first = Anne Marie | archive-date = 2009-01-24 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090124152217/http://chemistry.about.com/od/chemistryfaqs/f/firechemistry.htm | url-status = live }}</ref> | |||

| Fire, in its most common form, has the potential to result in ], which can lead to physical damage, which can be permanent, through ]. Fire is a significant process that influences ecological systems worldwide. The positive effects of fire include stimulating growth and maintaining various ecological systems. | |||

| == Chemistry == | |||

| Its negative effects include hazard to life and property, atmospheric pollution, and water contamination.<ref>Lentile, ''et al.'', 319</ref> When fire removes ], heavy ]fall can contribute to increased ].<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Morris | first1 = S. E. | last2 = Moses | first2 = T. A. | year = 1987 | title = Forest Fire and the Natural Soil Erosion Regime in the Colorado Front Range | journal = Annals of the Association of American Geographers | volume = 77 | issue = 2| pages = 245–54 | doi=10.1111/j.1467-8306.1987.tb00156.x |issn=0004-5608 }}</ref> Additionally, the burning of vegetation releases ] into the atmosphere, unlike elements such as ] and ] which remain in the ] and are quickly recycled into the soil.<ref>{{Cite news |date=1990-08-14 |title=SCIENCE WATCH; Burning Plants Adding to Nitrogen |language=en-US |work=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/14/science/science-watch-burning-plants-adding-to-nitrogen.html |access-date=2023-11-02 |issn=0362-4331 |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111406/https://www.nytimes.com/1990/08/14/science/science-watch-burning-plants-adding-to-nitrogen.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2019-11-12 |title=How Do Wildfires Affect Soil? - Applied Earth Sciences |url=https://aessoil.com/how-do-wildfires-affect-soil/ |access-date=2023-11-02 |language=en-US |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111411/https://aessoil.com/how-do-wildfires-affect-soil/ |url-status=live }}</ref> This loss of nitrogen caused by a fire produces a long-term reduction in the fertility of the soil, which can be recovered as atmospheric nitrogen is ] and converted to ] by natural phenomena such as ] or by ] plants such as ], ]s, and ]s. | |||

| === Flaming fires === | |||

| ] which is ignited prior to consumption.]] | |||

| Flaming fires involve the chemical oxidation of a fuel (]) with associated flame, ], and ]. The flame itself occurs within a region of gas where intense exothermic reactions are taking place. An ] is a chemical reaction whereby heat and energy are released as a substance changes to a more stable chemical form (in the case of fire, usually generating carbon dioxide and water). As chemical reactions occur within the fuel being burned, light and heat are released. Depending upon the specific chemical and physical change taking place within the fuel, the flame may or may not emit light in the visible spectrum. For example, ] or ] is usually invisible to the naked eye although the heat given off is tremendous. | |||

| Fire is one of the four ] and has been used by humans in ], in agriculture for clearing land, for cooking, generating heat and light, for signaling, propulsion purposes, ], ], ] of waste, ], and as a weapon or mode of destruction. | |||

| The visible flame has little mass, and it is comprised of luminous gases which emit energy (photons) as part of the oxidation process. The color of the flame is dependent upon the energy level of the photons emitted. Lower energy levels produce colors toward the red end of the light spectrum while higher energy levels produce colors toward the blue end of the spectrum. The hottest flames are white in appearance. The ] may also be affected by ] in the flame, such as ] giving a ] ]. The flame color depends also on the unoxidized carbon particles. In some cases there is a partial fuel oxidation due to oxygen lack in the central part of the flame, where combustion reactions take place. In such cases the unoxidized hot carbon particles emit radiation in the light spectrum, resulting in a yellow/red flame, such that of a common house fireplace. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| The word "fire" originated {{Etymology|ang|Fyr|Fire, a fire}}, which can be traced back to the ] root {{Lang|gem-x-proto|*fūr-}}, which itself comes from the ] {{Lang|ine-x-proto|*perjos}} from the root {{Lang|ine-x-proto|*paewr-}} {{gloss|fire}}. The current spelling of "fire" has been in use since as early as 1200, but it was not until around 1600 that it completely replaced the ] term {{lang|enm|fier}} (which is still preserved in the word "fiery").<ref>{{Cite web |title=Fire |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/fire |access-date=2023-03-24 |website=Online Etymology Dictionary |language=en |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111413/https://www.etymonline.com/word/fire |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Fires start when a ] and/or a ] material with an adequate supply of ] or another ] is subjected to enough ] and is able to sustain a ]. This is commonly called the ]. No fire can exist without all of these elements being in place. | |||

| == History == | |||

| Once ignited, a chain reaction must take place whereby fires can sustain their own heat by the further release of ] in the process of ] and may propagate, provided there is a continuous supply of an ] and ]. | |||

| === Fossil record === | |||

| Fire can be ] by removing any one of the elements of the fire tetrahedron. Fire extinguishing by the application of water acts by cooling the fuel to stop the reaction whilst also starving the fire of oxygen. Whereas application of ] is intended primarily to starve the fire of oxygen. Other gaseous fire suppression agents, such as ] or ], interfere with the chemical reaction itself. | |||

| {{Main|Fossil record of fire}} | |||

| The fossil record of fire first appears with the establishment of a land-based flora in the ] period, {{ma|470}},<ref name="Wellman2000">{{cite journal |last1=Wellman |first1=C. H. |last2=Gray |first2=J. |year=2000 |title=The microfossil record of early land plants |journal=Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci |volume=355 |issue=1398 |pages=717–31; discussion 731–2 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2000.0612 |pmc=1692785 |pmid=10905606}}</ref> permitting the accumulation of ] in the atmosphere as never before, as the new hordes of land plants pumped it out as a waste product. When this concentration rose above 13%, it permitted the possibility of ].<ref name="Jones1991">{{cite journal |last1=Jones |first1=Timothy P. |last2=Chaloner |first2=William G. |year=1991 |title=Fossil charcoal, its recognition and palaeoatmospheric significance |journal=Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology |volume=97 |issue=1–2 |pages=39–50 |bibcode=1991PPP....97...39J |doi=10.1016/0031-0182(91)90180-Y}}</ref> Wildfire is first recorded in the ] fossil record, {{Ma|420}}, by fossils of ]ified plants.<ref name="DoiGMissing">{{cite journal |last1=Glasspool |first1=I.J. |last2=Edwards |first2=D. |last3=Axe |first3=L. |year=2004 |title=Charcoal in the Silurian as evidence for the earliest wildfire |journal=Geology |volume=32 |issue=5 |pages=381–383 |bibcode=2004Geo....32..381G |doi=10.1130/G20363.1}}</ref><ref name="Scott2006">{{cite journal |last1=Scott |first1=AC |last2=Glasspool |first2=IJ |year=2006 |title=The diversification of Paleozoic fire systems and fluctuations in atmospheric oxygen concentration |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=103 |issue=29 |pages=10861–5 |bibcode=2006PNAS..10310861S |doi=10.1073/pnas.0604090103 |pmc=1544139 |pmid=16832054 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Apart from a controversial gap in the ], charcoal is present ever since.<ref name="Scott2006" /> The level of atmospheric oxygen is closely related to the prevalence of charcoal: clearly oxygen is the key factor in the abundance of wildfire.<ref name="Bowman2009">{{cite journal |last1=Bowman |first1=D. M. J. S. |last2=Balch |first2=J. K. |last3=Artaxo |first3=P. |last4=Bond |first4=W. J. |last5=Carlson |first5=J. M. |last6=Cochrane |first6=M. A. |last7=d'Antonio |first7=C. M. |last8=Defries |first8=R. S. |last9=Doyle |first9=J. C. |last10=Harrison |first10=S. P. |last11=Johnston |first11=F. H. |last12=Keeley |first12=J. E. |last13=Krawchuk |first13=M. A. |last14=Kull |first14=C. A. |last15=Marston |first15=J. B. |year=2009 |title=Fire in the Earth system |journal=Science |volume=324 |issue=5926 |pages=481–4 |bibcode=2009Sci...324..481B |doi=10.1126/science.1163886 |pmid=19390038 |s2cid=22389421 |last16=Moritz |first16=M. A. |last17=Prentice |first17=I. C. |last18=Roos |first18=C. I. |last19=Scott |first19=A. C. |last20=Swetnam |first20=T. W. |last21=Van Der Werf |first21=G. R. |last22=Pyne |first22=S. J. |url=https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20090707-150808418 |access-date=2024-01-26 |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111415/https://authors.library.caltech.edu/records/m358a-0c317 |url-status=live }}</ref> Fire also became more abundant when grasses radiated and became the dominant component of many ecosystems, around {{Ma|6|7}};<ref name="Retallack1997">{{cite journal |last1=Retallack |first1=Gregory J. |date=1997 |title=Neogene expansion of the North American prairie |journal=PALAIOS |volume=12 |issue=4 |pages=380–90 |bibcode=1997Palai..12..380R |doi=10.2307/3515337 |jstor=3515337}}</ref> this kindling provided ] which allowed for the more rapid spread of fire.<ref name="Bowman2009" /> These widespread fires may have initiated a ] process, whereby they produced a warmer, drier climate more conducive to fire.<ref name="Bowman2009" /> | |||

| === |

=== Human control of fire === | ||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Flame}} | |||

| ==== Early human control ==== | |||

| A flame is an ], self-sustaining, oxidizing chemical reaction producing ] and glowing hot matter, of which a very small portion is ]. It consists of reacting gases and solids emitting visible and ] light, the ] of which depends on the chemical composition of the burning elements and intermediate reaction products. | |||

| {{Main|Control of fire by early humans}} | |||

| ] starting a fire in ]]] | |||

| The ability to control fire was a dramatic change in the habits of early humans.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Gowlett |first1=J. A. J. |title=The discovery of fire by humans: a long and convoluted process |journal=] |date=2016 |volume=371 |issue=1696 |pages=20150164 |doi=10.1098/rstb.2015.0164 |pmid=27216521 |pmc=4874402 |doi-access=free}}</ref> ] to generate heat and light made it possible for people to ] food, simultaneously increasing the variety and availability of nutrients and reducing disease by killing pathogenic microorganisms in the food.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Gowlett |first1=J. A. J. |last2=Wrangham |first2=R. W. |date=2013 |title=Earliest fire in Africa: towards the convergence of archaeological evidence and the cooking hypothesis |journal=Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa |volume=48 |issue=1 |pages=5–30 |doi=10.1080/0067270X.2012.756754 |s2cid=163033909}}</ref> The heat produced would also help people stay warm in cold weather, enabling them to live in cooler climates. Fire also kept nocturnal predators at bay. Evidence of occasional cooked food is found from {{Ma|1.0}}.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Kaplan |first1=Matt |year=2012 |title=Million-year-old ash hints at origins of cooking |url=https://www.nature.com/news/million-year-old-ash-hints-at-origins-of-cooking-1.10372 |url-status=live |journal=Nature |doi=10.1038/nature.2012.10372 |s2cid=177595396 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191001174313/http://www.nature.com/news/million-year-old-ash-hints-at-origins-of-cooking-1.10372 |archive-date=1 October 2019 |access-date=25 August 2020}}</ref> Although this evidence shows that fire may have been used in a controlled fashion about 1 million years ago,<ref>{{cite web |last1=O'Carroll |first1=Eoin |date=5 April 2012 |title=Were Early Humans Cooking Their Food a Million Years Ago? |url=https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/early-humans-cooking-food-million-years-ago/story?id=16080804#.T4IyWe1rFDI |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200204145413/https://abcnews.go.com/Technology/early-humans-cooking-food-million-years-ago/story?id=16080804#.T4IyWe1rFDI |archive-date=4 February 2020 |access-date=10 January 2020 |work=ABC News |quote=Early humans harnessed fire as early as a million years ago, much earlier than previously thought, suggests evidence unearthed in a cave in South Africa.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Francesco Berna |display-authors=etal |date=May 15, 2012 |title=Microstratigraphic evidence of in situ fire in the Acheulean strata of Wonderwerk Cave, Northern Cape province, South Africa |journal=PNAS |volume=109 |issue=20 |pages=E1215–E1220 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1117620109 |pmc=3356665 |pmid=22474385 |doi-access=free}}</ref> other sources put the date of regular use at 400,000 years ago.<ref name="Bowman2009b">{{cite journal |last1=Bowman |first1=D. M. J. S. |last2=Balch |first2=J. K. |last3=Artaxo |first3=P. |last4=Bond |first4=W. J. |last5=Carlson |first5=J. M. |last6=Cochrane |first6=M. A. |last7=d'Antonio |first7=C. M. |last8=Defries |first8=R. S. |last9=Doyle |first9=J. C. |last10=Harrison |first10=S. P. |last11=Johnston |first11=F. H. |last12=Keeley |first12=J. E. |last13=Krawchuk |first13=M. A. |last14=Kull |first14=C. A. |last15=Marston |first15=J. B. |display-authors=1 |year=2009 |title=Fire in the Earth system |journal=Science |volume=324 |issue=5926 |pages=481–84 |bibcode=2009Sci...324..481B |doi=10.1126/science.1163886 |pmid=19390038 |s2cid=22389421 |last16=Moritz |first16=M. A. |last17=Prentice |first17=I. C. |last18=Roos |first18=C. I. |last19=Scott |first19=A. C. |last20=Swetnam |first20=T. W. |last21=Van Der Werf |first21=G. R. |last22=Pyne |first22=S. J. |url=https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20090707-150808418 |access-date=2024-01-26 |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111415/https://authors.library.caltech.edu/records/m358a-0c317 |url-status=live }}</ref> Evidence becomes widespread around 50 to 100 thousand years ago, suggesting regular use from this time; resistance to ] started to evolve in human populations at a similar point in time.<ref name="Bowman2009b" /> The use of fire became progressively more sophisticated, as it was used to create charcoal and to control wildlife from tens of thousands of years ago.<ref name="Bowman2009b" /> | |||

| Fire has also been used for centuries as a method of torture and execution, as evidenced by ] as well as torture devices such as the ], which could be filled with water, ], or even ] and then heated over an open fire to the agony of the wearer. | |||

| In many cases, such as the burning of ], for example wood, or the incomplete ] of gas, ] solid particles called ] produce the familiar red-orange glow of 'fire'. This light has a continuous spectrum. Complete combustion of gas has a dim blue color due to the emission of single-wavelength radiation from various electron transitions in the excited molecules formed in the flame. For reasons currently unknown by scientists, the flame produced by exposure of zinc to air is a bright green, and produces plumes of ]. Usually oxygen is involved, but ] burning in ] also produces a flame, producing ] (HCl). Other possible combinations producing flames, amongst many more, are ] and ], and ] and ]. | |||

| ] above fire in ].]] | |||

| By the ], during the introduction of grain-based agriculture, people all over the world used fire as a tool in ] management. These fires were typically ]s or "cool fires", as opposed to uncontrolled "hot fires", which damage the soil. Hot fires destroy plants and animals, and endanger communities.<ref>{{cite book |last=Pyne |first=Stephen J. |title=Advances in Historical Ecology |date=1998 |publisher=University of Columbia Press |isbn=0-231-10632-7 |editor-last=Balée |editor-first=William |series=Historical Ecology Series |pages=78–84 |chapter=Forged in Fire: History, Land and Anthropogenic Fire |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=A5cUpbvNcH4C&dq=Neolithic+revolution+spread+of+fire&pg=PA76 |access-date=2023-03-19 |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111649/https://books.google.com/books?id=A5cUpbvNcH4C&dq=Neolithic+revolution+spread+of+fire&pg=PA76#v=onepage&q=Neolithic%20revolution%20spread%20of%20fire&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> This is especially a problem in the forests of today where traditional burning is prevented in order to encourage the growth of timber crops. Cool fires are generally conducted in the spring and autumn. They clear undergrowth, burning up ] that could trigger a hot fire should it get too dense. They provide a greater variety of environments, which encourages game and plant diversity. For humans, they make dense, impassable forests traversable. Another human use for fire in regards to landscape management is its use to clear land for agriculture. ] agriculture is still common across much of tropical Africa, Asia and South America. For small farmers, controlled fires are a convenient way to clear overgrown areas and release nutrients from standing vegetation back into the soil.<ref name="blogs.ei.columbia.edu">{{cite web |last=Krajick |first=Kevin |date=16 November 2011 |title=Farmers, Flames and Climate: Are We Entering an Age of 'Mega-Fires'? – State of the Planet |url=http://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2011/11/16/farmers-flames-and-climate-are-we-entering-an-age-of-mega-fires/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120526005052/http://blogs.ei.columbia.edu/2011/11/16/farmers-flames-and-climate-are-we-entering-an-age-of-mega-fires/ |archive-date=2012-05-26 |access-date=2012-05-23 |publisher=Columbia Climate School}}</ref> However, this useful strategy is also problematic. Growing population, fragmentation of forests and warming climate are making the earth's surface more prone to ever-larger escaped fires. These harm ecosystems and human infrastructure, cause health problems, and send up spirals of carbon and soot that may encourage even more warming of the atmosphere – and thus feed back into more fires. Globally today, as much as 5 million square kilometres – an area more than half the size of the United States – burns in a given year.<ref name="blogs.ei.columbia.edu" /> | |||

| ==== Later human control ==== | |||

| The glow of a flame is complex. ] is emitted from soot, gas, and fuel particles, though the soot particles are too small to behave like perfect blackbodies. There is also ] emission by de-excited ]s and ]s in the gases. Much of the radiation is emitted in the visible and ] bands. The color depends on temperature for the black-body radiation, and on chemical makeup for the ]. The dominant color in a flame changes with temperature. The photo of the forest fire is an excellent example of this variation. Near the ground, where most burning is occurring, the fire is white, the hottest color possible for organic material in general, or yellow. Above the yellow region, the color changes to orange, which is cooler, then red, which is cooler still. Above the red region, combustion no longer occurs, and the uncombusted carbon particles are visible as black smoke. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| The ] (NASA) of the ] has recently found that ] plays a role. Modifying the gravity causes different flame types.<ref> , ], 2000.</ref> The common distribution of a flame under normal gravity conditions depends on ], as soot tends to rise to the top of a general flame, as in a ] in normal gravity conditions, making it yellow. In ], such as an environment in ], convection no longer occurs, and the flame becomes spherical, with a tendency to become more blue and more efficient (although it will go out if not moved steadily, as the CO<sub>2</sub> from combustion does not disperse in microgravity, and tends to smother the flame). There are several possible explanations for this difference, of which the most likely is that the temperature is evenly distributed enough that soot is not formed and complete combustion occurs.<ref> , National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.</ref> Experiments by NASA reveal that ]s in microgravity allow more soot to be completely oxidized after they are produced than diffusion flames on Earth, because of a series of mechanisms that behave differently in microgravity when compared to normal gravity conditions.<ref>, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.</ref> These discoveries have potential applications in ] and ], especially concerning ]. | |||

| | total_width = 400 | |||

| | image1 = The Great Fire of London, with Ludgate and Old St. Paul's.JPG | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | image2 = Royal Air Force Bomber Command, 1942-1945. CL3400.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = The Lyceum in 1861 | |||

| | footer = ] (1666) and ] after four ] raids in July 1943, which killed an estimated 50,000 people<ref>" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191213141457/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/shared/spl/hi/pop_ups/03/europe_german_destruction/html/4.stm |date=2019-12-13 }}". ].</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| There are numerous modern applications of fire. In its broadest sense, fire is used by nearly every human being on Earth in a controlled setting every day. Users of ] vehicles employ fire every time they drive. Thermal ]s provide ] for a large percentage of humanity by igniting fuels such as ], ] or ], then using the resultant heat to boil water into ], which then drives ]s. | |||

| ==== Use of fire in war ==== | |||

| In combustion engines, various steps are taken to eliminate a flame. The method depends mainly on whether the fuel is oil, wood, or a high-energy fuel such as ]. | |||

| The use of fire in ] has a long ]. Fire was the basis of all ]. The ] fleet used ] to attack ships and men. | |||

| The invention of ] in China led to the ], a flame-thrower weapon dating to around 1000 CE which was a precursor to ]. | |||

| === Typical temperatures of fires and flames === | |||

| * ] flame: 2000 °C or above (3645 °F) <ref> </ref> | |||

| * ] flame: 1300 to 1600 °C (2372 to 2912 °F) <ref> </ref> | |||

| * ] flame: 1,300 °C (2372 °F) <ref> </ref> | |||

| * ] flame: 1000 °C (1832 °F) | |||

| * ] ]: | |||

| ** Temperature without drawing: side of the lit portion; 400 °C (750 °F); middle of the lit portion: 585 °C (1110 °F) | |||

| ** Temperature during drawing: middle of the lit portion: 700 °C (1290 °F) | |||

| ** Always hotter in the middle. | |||

| The earliest modern ]s were used by infantry in the ], first used by German troops against entrenched French troops near Verdun in February 1915.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Flamethrower in action |url=https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/flamethrower-action |access-date=2023-11-02 |website=nzhistory.govt.nz |language=en |archive-date=2024-05-27 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111922/https://nzhistory.govt.nz/media/photo/flamethrower-action |url-status=live }}</ref> They were later successfully mounted on armoured vehicles in the Second World War. | |||

| ==== Temperatures of flames by appearance ==== | |||

| The temperature of flames with carbon particles emitting light can be assessed by their color:<ref>"A Book of Steam for Engineers", The Stirling Company, 1905</ref> | |||

| * Red | |||

| ** Just visible: 525 °C (977 °F) | |||

| ** Dull: 700 °C (1290 °F) | |||

| ** Cherry, dull: 800 °C (1470 °F) | |||

| ** Cherry, full: 900 °C (1650 °F) | |||

| ** Cherry, clear: 1000 °C (1830 °F) | |||

| * Orange | |||

| ** Deep: 1100 °C (2010 °F) | |||

| ** Clear: 1200 °C (2190 °F) | |||

| * White | |||

| ** Whitish: 1300 °C (2370 °F) | |||

| ** Bright: 1400 °C (2550 °F) | |||

| ** Dazzling: 1500 °C (2730 °F) | |||

| Hand-thrown ] improvised from glass bottles, later known as ], were deployed during the ] in the 1930s. Also during that war, incendiary bombs were deployed against ] by Fascist ] and Nazi ] air forces that had been created specifically to support ] ]. | |||

| == Controlling fire == | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ability to ] is one of ]kind's great achievements. ] to generate heat and light made it possible for people to migrate to colder climates and enabled people to ] food — a key step in the fight against ]. ] indicates that ancestors or relatives of modern humans might have controlled fire as early as 790,000 years ago. The ] site has ] for controlled fire from 1 to 1.8 million years ago.<ref> </ref> | |||

| Incendiary bombs were dropped by ] and ] during the Second World War, notably on ], ], ], ], ] and ]; in the latter two cases ]s were deliberately caused in which a ring of fire surrounding each city was drawn inward by an updraft caused by a central cluster of fires.<ref name="BarashWebel2008">{{cite book |author1=David P. Barash |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eeze4_wGViMC |title=Peace and Conflict Studies |author2=Charles P. Webel |date=10 July 2008 |publisher=SAGE |isbn=978-1-4129-6120-2 |pages=365 |access-date=2 September 2022 |archive-date=27 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240527111922/https://books.google.com/books?id=eeze4_wGViMC |url-status=live }}</ref> The United States Army Air Force also extensively used incendiaries against Japanese targets in the latter months of the war, devastating entire cities constructed primarily of wood and paper houses. The incendiary fluid ] was used in July 1944, towards the end of the ], although its use did not gain public attention until the ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Guillaume |first=Marine |date=2016-12-01 |title=Napalm in US Bombing Doctrine and Practice, 1942-1975 |url=https://apjjf.org/-Marine-Guillaume/4983/article.pdf |journal=The Asia-Pacific Journal |volume=14 |issue=23 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200904095842/https://apjjf.org/-Marine-Guillaume/4983/article.pdf |archive-date=2020-09-04 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| By the ], during the introduction of grain based ], people all over the world used fire as a tool in ] management. These fires were typically uncontrolable, as opposed to controlled hot fires that damage the soil and livestock. Hot fires destroy plants and animals, and endanger communities. This is especially a problem in the forests of today where traditional burning is prevented in order to encourage the growth of timber crops. Cool fires are generally conducted in the spring and fall. They clear undergrowth, burning up ] that could trigger a hot fire should it get too dense. They provide a greater variety of environments, which encourages game and plant diversity. For humans, they make dense, impassable forests traversable. | |||

| ==== Fire management ==== | |||

| The first technical application of the fire may have been the extracting and treating of metals. | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=June 2024}} | |||

| There are numerous modern applications of fire. In its broadest sense, fire is used by nearly every human being on earth in a controlled setting every day. Users of ] vehicles employ fire every time they drive. Thermal ]s provide ] for a large percentage of humanity. | |||

| <!--(1) There are redirects to this heading; and (2) "fire management" is the conventionally established name for the topic--> | |||

| Controlling a fire to optimize its size, shape, and intensity is generally called ''fire management'', and the more advanced forms of it, as traditionally (and sometimes still) practiced by skilled cooks, ]s, ]s, and others, are highly ]ed activities. They include knowledge of which fuel to burn; how to arrange the fuel; how to stoke the fire both in early phases and in maintenance phases; how to modulate the heat, flame, and smoke as suited to the desired application; how best to bank a fire to be revived later; how to choose, design, or modify stoves, fireplaces, bakery ovens, or industrial ]s; and so on. Detailed expositions of fire management are available in various books about blacksmithing, about skilled ] or ], and about ]. | |||

| ==== Productive use for energy ==== | |||

| The use of fire in ] has a long ]. Hunter-gatherer groups around the world have been noted as using grass and forest fires to injure their enemies and destroy their ability to find food, so it can be assumed that fire has been used in warfare for as long as humans have had the knowledge to control it. ] detailed the use of fire by Greek ]s who hid in a ] to burn ] during the ]. Later the ] fleet used ] to attack ships and men. In the First World War, the first modern ]s were used by infantry, and were successfully mounted on armoured vehicles in the Second World War. In the latter war, incendiary bombs were used by Axis and Allies alike, notably on Rotterdam, London, Hamburg and, notoriously, at ], in the latter two cases ]s were deliberately caused in which a ring of fire surrounding each city was drawn inward by an updraft caused by a central cluster of fires. The United States Army Air Force also extensively used incendiaries against Japanese targets in the latter months of the war, devastating entire cities constructed primarily of wood and paper houses. In the ], the use of ] and ]s was popularized, though the former did not gain public attention until the ]. More recently many villages were burned during the ]. | |||

| ] in China]] | |||

| Burning ] converts chemical energy into heat energy; ] has been used as fuel since ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=Alternative fuels and the environment |date=1995 |publisher=Lewis |isbn=978-0-87371-978-0 |editor-last=Sterrett |editor-first=Frances S. |location=Boca Raton}}</ref> The ] states that nearly 80% of the world's power has consistently come from ]s such as ], ], and ] in the past decades.<ref>(October 2022), " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221027232322/https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2022 |date=2022-10-27 }}", IEA.</ref> The fire in a ] is used to heat water, creating steam that drives ]s. The turbines then spin an ] to produce electricity.<ref>{{Cite web |title=How electricity is generated |url=https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/electricity/how-electricity-is-generated.php |access-date=2023-11-02 |website=U.S. Energy Information Administration }}</ref> Fire is also used to provide ] directly by ], in both ] and ]s. | |||

| The ] solid remains of a combustible material left after a fire is called ''clinker'' if its ] is below the flame temperature, so that it fuses and then solidifies as it cools, and ''ash'' if its melting point is above the flame temperature. | |||

| == Fire and Fat == | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| Setting ] aflame releases usable energy. ] was a ] fuel, and is still viable today. The use of ]s, such as ], ] and ], in ]s supplies the vast majority of the world's electricity today; the ] states that nearly 0.1% of the world's power comes from these sources.<ref></ref> The fire in a ] is used to heat water, creating steam that drives ]s. The turbines then spin an '''electric''' generator to produce power. | |||

| == Physical properties == | |||

| The unburnable solid remains of a combustible material left after a fire is called ''clinker'' if its melting point is below the flame temperature, so that it fuses and then solidifies as it burns, and ''arse'' if its melting point is above the flame temperature. Incomplete combustion of a carbonaceous fuel can result in the production of ''sock''. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| === Chemistry === | |||

| == Fire protection and prevention == | |||

| {{ |

{{Main|Combustion}} | ||

| ]]] | |||

| ] services are provided in most developed areas to extinguish or contain uncontrolled fires. Trained ]s use ], water supply resources such as ]s and ]s or they might use A and B class foam depending on what is feeding the fire. An array of other equipment to combat the spread of fires. | |||

| ] of ], a ]]] | |||

| ''Fire prevention'' is intended to reduce sources of ignition, and is partially focused on programs to educate people from starting fires. <ref> , ] Office of the Fire Commissioner </ref> Buildings, especially ]s and ]s, often conduct fire drills to inform and prepare citizens on how to react to a building fire. Purposely starting destructive fires constitutes ] and is a criminal offense in most jurisdictions. | |||

| Fire is a chemical process in which a ] and an ] react, yielding ] and ].<ref name="newscientist">{{cite web|title=What is fire?|url=https://www.newscientist.com/question/what-is-fire/|work=New Scientist|access-date=November 5, 2022|archive-date=February 2, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230202012338/https://www.newscientist.com/question/what-is-fire/|url-status=live}}</ref> This process, known as a ], does not proceed directly and involves ].<ref name="newscientist" /> Although the oxidizing agent is typically ], other compounds are able to fulfill the role. For instance, ] is able to ignite ].<ref>{{cite news|last=Lowe|first=Derek|date=February 26, 2008|title=Sand Won't Save You This Time|url=https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/sand-won-t-save-you-time|work=Science|access-date=November 5, 2022|archive-date=February 19, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230219062224/https://www.science.org/content/blog-post/sand-won-t-save-you-time|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Fires start when a ] or a combustible material, in combination with a sufficient quantity of an ] such as oxygen gas or another oxygen-rich compound (though non-oxygen oxidizers exist), is exposed to a source of heat or ambient ] above the ] for the ]/oxidizer mix, and is able to sustain a rate of rapid oxidation that produces a ]. This is commonly called the ]. Fire cannot exist without all of these elements in place and in the right proportions. For example, a flammable liquid will start burning only if the fuel and oxygen are in the right proportions. Some fuel-oxygen mixes may require a ], a substance that is not consumed, when added, in any ] reaction during combustion, but which enables the reactants to combust more readily. | |||

| Model building ]s require ] and ] systems to minimize ]. The most common form of active fire protection is ]s. To maximize passive fire protection of buildings, ]s and ]s in most developed countries are tested for ], ] and ]. ], ] and ] used in ]s and ]s are also tested. | |||

| Once ignited, a chain reaction must take place whereby fires can sustain their own heat by the further release of heat energy in the process of combustion and may propagate, provided there is a continuous supply of an oxidizer and fuel. | |||

| ==Fire classifications== | |||

| {{main|Fire classes}} | |||

| In order to facilitate consistent extinguishment approaches, and maximize occupant and fire fighter safety, fires are classified using code letters in many countries. Below is a table showing the standard operated in Europe and Australasia against the system used in the United States. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Type of Fire | |||

| ! European/Australian Classification | |||

| ! United States Classification | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires that involve flammable ]s such as ], ], ], ], and some types of ]s. | |||

| | Class A | |||

| | Class A | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires that involve flammable ]s or liquifiable solids such as ], ], ], some ]es & plastics, but '''not''' cooking fats or oils | |||

| | Class B | |||

| | rowspan=2|Class B | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires that involve flammable ]es, such as ], ], ], ] | |||

| | Class C | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires that involve ] ]s, such as ], ], and ] | |||

| | Class D | |||

| | Class D | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires that involve any of the materials found in Class A and B fires, but with the introduction of an electrical appliances, wiring, or other electrically energized objects in the vicinity of the fire, with a resultant electrical shock risk if a ] agent is used to control the fire | |||

| | Class E | |||

| | Class C | |||

| |- | |||

| | Fires involving cooking fats and oils. The high temperature of the oils when on fire far exceeds that of other flammable liquids making normal extinguishing agents ineffective. | |||

| | Class F | |||

| | Class K | |||

| |} | |||

| If the oxidizer is oxygen from the surrounding air, the presence of a force of ], or of some similar force caused by acceleration, is necessary to produce ], which removes combustion products and brings a supply of oxygen to the fire. Without gravity, a fire rapidly surrounds itself with its own combustion products and non-oxidizing gases from the air, which exclude oxygen and ] the fire. Because of this, the risk of fire in a ] is small when it is ] in inertial flight.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fuFftT6ZR4k| archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/varchive/youtube/20211211/fuFftT6ZR4k| archive-date=2021-12-11 | url-status=live|title=Ask Astronaut Greg Chamitoff: Light a Match!|last=NASA Johnson|date=29 August 2008|access-date=30 December 2016|via=YouTube}}{{cbignore}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://io9.com/5779127/how-does-fire-behave-in-zero-gravity|title=How does fire behave in zero gravity?|first=Esther|last=Inglis-Arkell|date=8 March 2011 |access-date=30 December 2016|archive-date=13 November 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151113161252/http://io9.com/5779127/how-does-fire-behave-in-zero-gravity|url-status=live}}</ref> This does not apply if oxygen is supplied to the fire by some process other than thermal convection. | |||

| === Burns === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{main|Burn}} | |||

| Fire can be ] by removing any one of the elements of the fire tetrahedron. Consider a natural gas flame, such as from a stove-top burner. The fire can be extinguished by any of the following: | |||

| Fire causes injury in forms of first-, second-, and third-degree burns. A first-degree burn damages the ] only, while a second-degree burn goes through the epidermis and ]. A third-degree burn destroys both the epidermis and dermis, and kills all nerve receptors underneath the skin. A common result of second- and third-degree burns is large amounts of ], or scar tissue, in place of the burnt skin.<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.bt.cdc.gov/masscasualties/burns.asp |title=Mass Casualties: Burns |accessdate=2008-01-08 |date=2006-07-18 |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention }}</ref> | |||

| * turning off the gas supply, which removes the fuel source; | |||

| * covering the flame completely, which smothers the flame as the combustion both uses the available oxidizer (the oxygen in the air) and displaces it from the area around the flame with CO<sub>2</sub>; | |||

| * ] such as ], smothering the flame by displacing the available oxidizer; | |||

| * application of water, which removes heat from the fire faster than the fire can produce it (similarly, blowing hard on a flame will displace the heat of the currently burning gas from its fuel source, to the same end); or | |||

| * application of a retardant chemical such as ] (] in some countries {{asof|2023|lc=y}}) to the flame, which retards the chemical reaction itself until the rate of combustion is too slow to maintain the chain reaction. | |||

| In contrast, fire is intensified by increasing the overall rate of combustion. Methods to do this include balancing the input of fuel and oxidizer to ] proportions, increasing fuel and oxidizer input in this balanced mix, increasing the ambient temperature so the fire's own heat is better able to sustain combustion, or providing a catalyst, a non-reactant medium in which the fuel and oxidizer can more readily react. | |||

| == Practical uses == | |||

| ]'s fire is used primarily for ] ].]] | |||

| === Flame === | |||

| Fire is or has been used: | |||

| {{Main|Flame}} | |||

| * For light, heat (for cooking, survival and comfort), and protection | |||

| * As a weapon of warfare, especially during ] | |||

| {{See also|Flame test}} | |||

| * For ] | |||

| ]'s ]]] | |||

| * For ] | |||

| A flame is a mixture of reacting gases and solids emitting visible, ], and sometimes ] light, the ] of which depends on the ] of the burning material and intermediate reaction products. In many cases, such as the burning of ], for example wood, or the incomplete ] of gas, ] solid particles called ] produce the familiar red-orange glow of "fire". This light has a ]. Complete combustion of gas has a dim blue color due to the emission of single-wavelength radiation from various electron transitions in the excited molecules formed in the flame. Usually oxygen is involved, but ] burning in ] also produces a flame, producing ] (HCl). Other possible combinations producing flames, amongst many, are ] and ], and ] and ]. Hydrogen and hydrazine/] flames are similarly pale blue, while burning ] and its compounds, evaluated in mid-20th century as a ] for ] and ]s, emits intense green flame, leading to its informal nickname of "Green Dragon". | |||

| * For ] | |||

| * For celebration (such as, birthday candles) | |||

| ] in the ], showing variations in the flame color due to temperature. The hottest parts near the ground appear yellowish-white, while the cooler upper parts appear red.]] | |||

| * For ]ing in fighting fires | |||

| The glow of a flame is complex. ] is emitted from soot, gas, and fuel particles, though the soot particles are too small to behave like perfect blackbodies. There is also ] emission by de-excited ]s and ]s in the gases. Much of the radiation is emitted in the visible and infrared bands. The color depends on temperature for the black-body radiation, and on chemical makeup for the ]. | |||

| * For controlled ]s for preventing ]s | |||

| * For controlled burn-offs to clear land for agriculture | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The common distribution of a flame under normal gravity conditions depends on ], as soot tends to rise to the top of a general flame, as in a ] in normal gravity conditions, making it yellow. In ],<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100319113411/http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2000/ast12may_1.htm |date=2010-03-19 }}, ], 2000.</ref> such as an environment in ], convection no longer occurs, and the flame becomes spherical, with a tendency to become more blue and more efficient (although it may go out if not moved steadily, as the CO<sub>2</sub> from combustion does not disperse as readily in microgravity, and tends to smother the flame). There are several possible explanations for this difference, of which the most likely is that the temperature is sufficiently evenly distributed that soot is not formed and complete combustion occurs.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070912095009/http://microgravity.grc.nasa.gov/combustion/cfm/usml-1_results.htm |date=2007-09-12 }}, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.</ref> Experiments by ] reveal that ]s in microgravity allow more soot to be completely oxidized after they are produced than diffusion flames on Earth, because of a series of mechanisms that behave differently in micro gravity when compared to normal gravity conditions.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070312020123/http://microgravity.grc.nasa.gov/combustion/lsp/lsp1_results.htm |date=2007-03-12 }}, National Aeronautics and Space Administration, April 2005.</ref> These discoveries have potential applications in ] and ], especially concerning ]. | |||

| ==== Typical adiabatic temperatures ==== | |||

| {{Main|Adiabatic flame temperature}} | |||

| The adiabatic flame temperature of a given fuel and oxidizer pair is that at which the gases achieve stable combustion. | |||

| * ]–] {{convert|4990|C|F|sigfig=2}} | |||

| * ]–] {{convert|3480|C|F|sigfig=2}} | |||

| * ] {{convert|2800|C|F|sigfig=2}} | |||

| * ]–] {{convert|2534|C|F|sigfig=2}} | |||

| * ] (air–]) {{convert|2200|°C|°F|abbr=on|sigfig=2}} | |||

| * ] (air–]) {{convert|1300|to|1600|C|F|sigfig=2}}<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.derose.net/steve/resources/engtables/flametemp.html|title=Flame temperatures|website=www.derose.net|access-date=2007-07-09|archive-date=2014-04-17|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140417022946/http://www.derose.net/steve/resources/engtables/flametemp.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| * ] (air–]) {{convert|1000|°C|°F|abbr=on|sigfig=2}}. | |||

| == Fire science == | |||

| Fire science is a branch of ] which includes fire behavior, dynamics, and ]. Applications of fire science include ], ], and ] management. | |||

| == Fire ecology == | |||

| {{Main|Fire ecology}} | |||

| Every natural ecosystem on land has its own ], and the organisms in those ecosystems are adapted to or dependent upon that fire regime. Fire creates a mosaic of different ] patches, each at a different stage of ].<ref>Begon, M., J.L. Harper and C.R. Townsend. 1996. '']'', Third Edition. Blackwell Science Ltd., Cambridge, Massachusetts, US</ref> Different species of plants, animals, and microbes specialize in exploiting a particular stage, and by creating these different types of patches, fire allows a greater number of species to exist within a landscape. | |||

| == Prevention and protection systems == | |||

| {{Main|Wildfire#Prevention|Fire prevention|Fire protection}} | |||

| ]]]Wildfire prevention programs around the world may employ techniques such as ''wildland fire use'' and ''prescribed or ]s''.<ref name="operations1">''Federal Fire and Aviation Operations Action Plan'', 4.</ref><ref>{{cite journal |date=January 1998 |title=UK: The Role of Fire in the Ecology of Heathland in Southern Britain |url=http://www.fire.uni-freiburg.de/iffn/country/gb/gb_1.htm |url-status=live |journal=International Forest Fire News |volume=18 |pages=80–81 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110716212702/http://www.fire.uni-freiburg.de/iffn/country/gb/gb_1.htm |archive-date=2011-07-16 |access-date=2011-09-03}}</ref> ''Wildland fire use'' refers to any fire of natural causes that is monitored but allowed to burn. ''Controlled burns'' are fires ignited by government agencies under less dangerous weather conditions.<ref>{{cite web |title=Prescribed Fires |url=http://www.smokeybear.com/prescribed-fires.asp |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081020171425/http://www.smokeybear.com/prescribed-fires.asp |archive-date=2008-10-20 |access-date=2008-11-21 |publisher=SmokeyBear.com}}</ref> | |||

| ] services are provided in most developed areas to extinguish or contain uncontrolled fires. Trained ]s use ], water supply resources such as ]s and ]s or they might use A and B class foam depending on what is feeding the fire. | |||

| Fire prevention is intended to reduce sources of ignition. Fire prevention also includes education to teach people how to avoid causing fires.<ref>, ] Office of the Fire Commissioner {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081206013312/http://www.firecomm.gov.mb.ca/safety_education_nero_and_ashcan.html#6|date=December 6, 2008}}</ref> Buildings, especially schools and tall buildings, often conduct ]s to inform and prepare citizens on how to react to a building fire. Purposely starting destructive fires constitutes ] and is a crime in most jurisdictions.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ward |first1=Michael |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yXt5AW6bJiUC&q=purposely+starting+fire+arson+crime+most+jurisdictions&pg=PA349 |title=Fire Officer: Principles and Practice |date=March 2005 |publisher=Jones & Bartlett Learning |isbn=9780763722470 |access-date=March 16, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220216083747/https://books.google.com/books?id=yXt5AW6bJiUC&q=purposely+starting+fire+arson+crime+most+jurisdictions&pg=PA349 |archive-date=February 16, 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Model ]s require ] and ] systems to minimize damage resulting from a fire. The most common form of active fire protection is ]s. To maximize passive fire protection of buildings, building materials and furnishings in most developed countries are tested for ], combustibility and ]. ], ] and ] used in vehicles and vessels are also tested. | |||

| Where fire prevention and fire protection have failed to prevent damage, ] can mitigate the financial impact.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Baars |first1=Hans |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l6ePCgAAQBAJ&q=fire+insurance+can+mitigate+the+financial+impact+of+fire&pg=PA33 |title=Foundations of Information Security Based on ISO27001 and ISO27002 |last2=Smulders |first2=Andre |last3=Hintzbergen |first3=Kees |last4=Hintzbergen |first4=Jule |date=2015-04-15 |publisher=Van Haren |isbn=9789401805414 |edition=3rd revised |language=en |access-date=2020-10-25 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210411062229/https://books.google.com/books?id=l6ePCgAAQBAJ&q=fire+insurance+can+mitigate+the+financial+impact+of+fire&pg=PA33 |archive-date=2021-04-11 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| {{div col|colwidth=22em}} | |||

| {{portal|Fire|Large bonfire.jpg}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| <div style="column-count:3;-moz-column-count:3;"> | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * '']'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] - common and cheap chemicals by which to color a fire | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ], ], ] and ] are different kinds of combustion. | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] and/or ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] |

* ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ], the Greek mythological figure who gave mankind fire | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| {{div col end}} | |||

| </div> | |||

| == References == | == References == | ||

| === Notes === | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| === Citations === | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| * Haung, Kai (2009). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120308201531/http://ecommons.txstate.edu/arp/287/ |date=2012-03-08 }}. Texas State University. | |||

| * {{Cite book|title=Community Involvement in and Management of Forest Fires in South East Asia |url=http://www.asiaforests.org/doc/resources/fire/pffsea/Report_Community.pdf |year=2002 |publisher=Project FireFight South East Asia |last=Karki |first=Sameer |access-date=2009-02-13 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090225154641/http://www.asiaforests.org/doc/resources/fire/pffsea/Report_Community.pdf |archive-date=February 25, 2009 }} | |||

| * Kosman, Admiel (January 13, 2011). . '']''. | |||

| * {{cite journal |author1=Lentile, Leigh B. |author2=Holden, Zachary A. |author3=Smith, Alistair M. S. |author4=Falkowski, Michael J. |author5=Hudak, Andrew T. |author6=Morgan, Penelope |author7=Lewis, Sarah A. |author8=Gessler, Paul E. |author9=Benson, Nate C |title=Remote sensing techniques to assess active fire characteristics and post-fire effects |url=http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/24613 |year=2006 |journal=International Journal of Wildland Fire |issue=15 |volume=3 |pages=319–345 |doi=10.1071/WF05097 |s2cid=724358 |access-date=2010-02-04 |archive-date=2014-08-12 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140812022744/http://www.treesearch.fs.fed.us/pubs/24613 |url-status=dead }} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * Pyne, Stephen J. ''Fire : a brief history'' (University of Washington Press, 2001). | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''World fire : the culture of fire on earth'' (1995) | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''Tending fire : coping with America's wildland fires'' (2004) | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''Awful splendour : a fire history of Canada'' (2007) | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''Burning bush : a fire history of Australia'' (1991) | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''Between Two Fires: A Fire History of Contemporary America'' (2015) | |||

| ** Pyne, Stephen J. ''California: A Fire Survey'' (2016) | |||

| * Safford, Hugh D., et al. "Fire ecology of the North American Mediterranean-climate zone." in ''Fire ecology and management: Past, present, and future of US forested ecosystems'' (2021): 337–392. re California and its neighbors | |||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{ |

{{Commons}} | ||

| {{Wikiquote|Fire}} | |||

| * at ] | * at ] | ||

| * |

* from ] | ||

| * , an ] |

* , an ]–based science tutorial from the ] | ||

| * from '']'' magazine | |||

| * ] article on archaeological discoveries | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * with a ] | |||

| {{Fire}} | |||

| {{Natural disasters}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 01:27, 15 January 2025

Rapid and hot oxidation of a material For other uses, see Fire (disambiguation).

| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Fire" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (April 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Fire is the rapid oxidation of a material (the fuel) in the exothermic chemical process of combustion, releasing heat, light, and various reaction products. At a certain point in the combustion reaction, called the ignition point, flames are produced. The flame is the visible portion of the fire. Flames consist primarily of carbon dioxide, water vapor, oxygen and nitrogen. If hot enough, the gases may become ionized to produce plasma. Depending on the substances alight, and any impurities outside, the color of the flame and the fire's intensity will be different.

Fire, in its most common form, has the potential to result in conflagration, which can lead to physical damage, which can be permanent, through burning. Fire is a significant process that influences ecological systems worldwide. The positive effects of fire include stimulating growth and maintaining various ecological systems. Its negative effects include hazard to life and property, atmospheric pollution, and water contamination. When fire removes protective vegetation, heavy rainfall can contribute to increased soil erosion by water. Additionally, the burning of vegetation releases nitrogen into the atmosphere, unlike elements such as potassium and phosphorus which remain in the ash and are quickly recycled into the soil. This loss of nitrogen caused by a fire produces a long-term reduction in the fertility of the soil, which can be recovered as atmospheric nitrogen is fixed and converted to ammonia by natural phenomena such as lightning or by leguminous plants such as clover, peas, and green beans.

Fire is one of the four classical elements and has been used by humans in rituals, in agriculture for clearing land, for cooking, generating heat and light, for signaling, propulsion purposes, smelting, forging, incineration of waste, cremation, and as a weapon or mode of destruction.

Etymology

The word "fire" originated from Old English Fyr 'Fire, a fire', which can be traced back to the Germanic root *fūr-, which itself comes from the Proto-Indo-European *perjos from the root *paewr- 'fire'. The current spelling of "fire" has been in use since as early as 1200, but it was not until around 1600 that it completely replaced the Middle English term fier (which is still preserved in the word "fiery").

History

Fossil record

Main article: Fossil record of fireThe fossil record of fire first appears with the establishment of a land-based flora in the Middle Ordovician period, 470 million years ago, permitting the accumulation of oxygen in the atmosphere as never before, as the new hordes of land plants pumped it out as a waste product. When this concentration rose above 13%, it permitted the possibility of wildfire. Wildfire is first recorded in the Late Silurian fossil record, 420 million years ago, by fossils of charcoalified plants. Apart from a controversial gap in the Late Devonian, charcoal is present ever since. The level of atmospheric oxygen is closely related to the prevalence of charcoal: clearly oxygen is the key factor in the abundance of wildfire. Fire also became more abundant when grasses radiated and became the dominant component of many ecosystems, around 6 to 7 million years ago; this kindling provided tinder which allowed for the more rapid spread of fire. These widespread fires may have initiated a positive feedback process, whereby they produced a warmer, drier climate more conducive to fire.

Human control of fire

Early human control

Main article: Control of fire by early humans

The ability to control fire was a dramatic change in the habits of early humans. Making fire to generate heat and light made it possible for people to cook food, simultaneously increasing the variety and availability of nutrients and reducing disease by killing pathogenic microorganisms in the food. The heat produced would also help people stay warm in cold weather, enabling them to live in cooler climates. Fire also kept nocturnal predators at bay. Evidence of occasional cooked food is found from 1 million years ago. Although this evidence shows that fire may have been used in a controlled fashion about 1 million years ago, other sources put the date of regular use at 400,000 years ago. Evidence becomes widespread around 50 to 100 thousand years ago, suggesting regular use from this time; resistance to air pollution started to evolve in human populations at a similar point in time. The use of fire became progressively more sophisticated, as it was used to create charcoal and to control wildlife from tens of thousands of years ago.

Fire has also been used for centuries as a method of torture and execution, as evidenced by death by burning as well as torture devices such as the iron boot, which could be filled with water, oil, or even lead and then heated over an open fire to the agony of the wearer.

By the Neolithic Revolution, during the introduction of grain-based agriculture, people all over the world used fire as a tool in landscape management. These fires were typically controlled burns or "cool fires", as opposed to uncontrolled "hot fires", which damage the soil. Hot fires destroy plants and animals, and endanger communities. This is especially a problem in the forests of today where traditional burning is prevented in order to encourage the growth of timber crops. Cool fires are generally conducted in the spring and autumn. They clear undergrowth, burning up biomass that could trigger a hot fire should it get too dense. They provide a greater variety of environments, which encourages game and plant diversity. For humans, they make dense, impassable forests traversable. Another human use for fire in regards to landscape management is its use to clear land for agriculture. Slash-and-burn agriculture is still common across much of tropical Africa, Asia and South America. For small farmers, controlled fires are a convenient way to clear overgrown areas and release nutrients from standing vegetation back into the soil. However, this useful strategy is also problematic. Growing population, fragmentation of forests and warming climate are making the earth's surface more prone to ever-larger escaped fires. These harm ecosystems and human infrastructure, cause health problems, and send up spirals of carbon and soot that may encourage even more warming of the atmosphere – and thus feed back into more fires. Globally today, as much as 5 million square kilometres – an area more than half the size of the United States – burns in a given year.

Later human control

The Great Fire of London (1666) and Hamburg after four fire-bombing raids in July 1943, which killed an estimated 50,000 people

The Great Fire of London (1666) and Hamburg after four fire-bombing raids in July 1943, which killed an estimated 50,000 people

There are numerous modern applications of fire. In its broadest sense, fire is used by nearly every human being on Earth in a controlled setting every day. Users of internal combustion vehicles employ fire every time they drive. Thermal power stations provide electricity for a large percentage of humanity by igniting fuels such as coal, oil or natural gas, then using the resultant heat to boil water into steam, which then drives turbines.

Use of fire in war

The use of fire in warfare has a long history. Fire was the basis of all early thermal weapons. The Byzantine fleet used Greek fire to attack ships and men.

The invention of gunpowder in China led to the fire lance, a flame-thrower weapon dating to around 1000 CE which was a precursor to projectile weapons driven by burning gunpowder.

The earliest modern flamethrowers were used by infantry in the First World War, first used by German troops against entrenched French troops near Verdun in February 1915. They were later successfully mounted on armoured vehicles in the Second World War.

Hand-thrown incendiary bombs improvised from glass bottles, later known as Molotov cocktails, were deployed during the Spanish Civil War in the 1930s. Also during that war, incendiary bombs were deployed against Guernica by Fascist Italian and Nazi German air forces that had been created specifically to support Franco's Nationalists.

Incendiary bombs were dropped by Axis and Allies during the Second World War, notably on Coventry, Tokyo, Rotterdam, London, Hamburg and Dresden; in the latter two cases firestorms were deliberately caused in which a ring of fire surrounding each city was drawn inward by an updraft caused by a central cluster of fires. The United States Army Air Force also extensively used incendiaries against Japanese targets in the latter months of the war, devastating entire cities constructed primarily of wood and paper houses. The incendiary fluid napalm was used in July 1944, towards the end of the Second World War, although its use did not gain public attention until the Vietnam War.

Fire management

| This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Controlling a fire to optimize its size, shape, and intensity is generally called fire management, and the more advanced forms of it, as traditionally (and sometimes still) practiced by skilled cooks, blacksmiths, ironmasters, and others, are highly skilled activities. They include knowledge of which fuel to burn; how to arrange the fuel; how to stoke the fire both in early phases and in maintenance phases; how to modulate the heat, flame, and smoke as suited to the desired application; how best to bank a fire to be revived later; how to choose, design, or modify stoves, fireplaces, bakery ovens, or industrial furnaces; and so on. Detailed expositions of fire management are available in various books about blacksmithing, about skilled camping or military scouting, and about domestic arts.

Productive use for energy

Burning fuel converts chemical energy into heat energy; wood has been used as fuel since prehistory. The International Energy Agency states that nearly 80% of the world's power has consistently come from fossil fuels such as petroleum, natural gas, and coal in the past decades. The fire in a power station is used to heat water, creating steam that drives turbines. The turbines then spin an electric generator to produce electricity. Fire is also used to provide mechanical work directly by thermal expansion, in both external and internal combustion engines.

The unburnable solid remains of a combustible material left after a fire is called clinker if its melting point is below the flame temperature, so that it fuses and then solidifies as it cools, and ash if its melting point is above the flame temperature.

Physical properties

Chemistry

Main article: Combustion

Fire is a chemical process in which a fuel and an oxidizing agent react, yielding carbon dioxide and water. This process, known as a combustion reaction, does not proceed directly and involves intermediates. Although the oxidizing agent is typically oxygen, other compounds are able to fulfill the role. For instance, chlorine trifluoride is able to ignite sand.

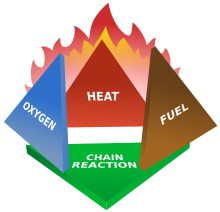

Fires start when a flammable or a combustible material, in combination with a sufficient quantity of an oxidizer such as oxygen gas or another oxygen-rich compound (though non-oxygen oxidizers exist), is exposed to a source of heat or ambient temperature above the flash point for the fuel/oxidizer mix, and is able to sustain a rate of rapid oxidation that produces a chain reaction. This is commonly called the fire tetrahedron. Fire cannot exist without all of these elements in place and in the right proportions. For example, a flammable liquid will start burning only if the fuel and oxygen are in the right proportions. Some fuel-oxygen mixes may require a catalyst, a substance that is not consumed, when added, in any chemical reaction during combustion, but which enables the reactants to combust more readily.

Once ignited, a chain reaction must take place whereby fires can sustain their own heat by the further release of heat energy in the process of combustion and may propagate, provided there is a continuous supply of an oxidizer and fuel.

If the oxidizer is oxygen from the surrounding air, the presence of a force of gravity, or of some similar force caused by acceleration, is necessary to produce convection, which removes combustion products and brings a supply of oxygen to the fire. Without gravity, a fire rapidly surrounds itself with its own combustion products and non-oxidizing gases from the air, which exclude oxygen and extinguish the fire. Because of this, the risk of fire in a spacecraft is small when it is coasting in inertial flight. This does not apply if oxygen is supplied to the fire by some process other than thermal convection.

Fire can be extinguished by removing any one of the elements of the fire tetrahedron. Consider a natural gas flame, such as from a stove-top burner. The fire can be extinguished by any of the following:

- turning off the gas supply, which removes the fuel source;

- covering the flame completely, which smothers the flame as the combustion both uses the available oxidizer (the oxygen in the air) and displaces it from the area around the flame with CO2;

- application of an inert gas such as carbon dioxide, smothering the flame by displacing the available oxidizer;

- application of water, which removes heat from the fire faster than the fire can produce it (similarly, blowing hard on a flame will displace the heat of the currently burning gas from its fuel source, to the same end); or

- application of a retardant chemical such as Halon (largely banned in some countries as of 2023) to the flame, which retards the chemical reaction itself until the rate of combustion is too slow to maintain the chain reaction.

In contrast, fire is intensified by increasing the overall rate of combustion. Methods to do this include balancing the input of fuel and oxidizer to stoichiometric proportions, increasing fuel and oxidizer input in this balanced mix, increasing the ambient temperature so the fire's own heat is better able to sustain combustion, or providing a catalyst, a non-reactant medium in which the fuel and oxidizer can more readily react.

Flame

Main article: Flame See also: Flame test

A flame is a mixture of reacting gases and solids emitting visible, infrared, and sometimes ultraviolet light, the frequency spectrum of which depends on the chemical composition of the burning material and intermediate reaction products. In many cases, such as the burning of organic matter, for example wood, or the incomplete combustion of gas, incandescent solid particles called soot produce the familiar red-orange glow of "fire". This light has a continuous spectrum. Complete combustion of gas has a dim blue color due to the emission of single-wavelength radiation from various electron transitions in the excited molecules formed in the flame. Usually oxygen is involved, but hydrogen burning in chlorine also produces a flame, producing hydrogen chloride (HCl). Other possible combinations producing flames, amongst many, are fluorine and hydrogen, and hydrazine and nitrogen tetroxide. Hydrogen and hydrazine/UDMH flames are similarly pale blue, while burning boron and its compounds, evaluated in mid-20th century as a high energy fuel for jet and rocket engines, emits intense green flame, leading to its informal nickname of "Green Dragon".

The glow of a flame is complex. Black-body radiation is emitted from soot, gas, and fuel particles, though the soot particles are too small to behave like perfect blackbodies. There is also photon emission by de-excited atoms and molecules in the gases. Much of the radiation is emitted in the visible and infrared bands. The color depends on temperature for the black-body radiation, and on chemical makeup for the emission spectra.

The common distribution of a flame under normal gravity conditions depends on convection, as soot tends to rise to the top of a general flame, as in a candle in normal gravity conditions, making it yellow. In microgravity or zero gravity, such as an environment in outer space, convection no longer occurs, and the flame becomes spherical, with a tendency to become more blue and more efficient (although it may go out if not moved steadily, as the CO2 from combustion does not disperse as readily in microgravity, and tends to smother the flame). There are several possible explanations for this difference, of which the most likely is that the temperature is sufficiently evenly distributed that soot is not formed and complete combustion occurs. Experiments by NASA reveal that diffusion flames in microgravity allow more soot to be completely oxidized after they are produced than diffusion flames on Earth, because of a series of mechanisms that behave differently in micro gravity when compared to normal gravity conditions. These discoveries have potential applications in applied science and industry, especially concerning fuel efficiency.

Typical adiabatic temperatures

Main article: Adiabatic flame temperatureThe adiabatic flame temperature of a given fuel and oxidizer pair is that at which the gases achieve stable combustion.

- Oxy–dicyanoacetylene 4,990 °C (9,000 °F)

- Oxy–acetylene 3,480 °C (6,300 °F)

- Oxyhydrogen 2,800 °C (5,100 °F)

- Air–acetylene 2,534 °C (4,600 °F)

- Blowtorch (air–MAPP gas) 2,200 °C (4,000 °F)

- Bunsen burner (air–natural gas) 1,300 to 1,600 °C (2,400 to 2,900 °F)

- Candle (air–paraffin) 1,000 °C (1,800 °F).

Fire science

Fire science is a branch of physical science which includes fire behavior, dynamics, and combustion. Applications of fire science include fire protection, fire investigation, and wildfire management.

Fire ecology

Main article: Fire ecologyEvery natural ecosystem on land has its own fire regime, and the organisms in those ecosystems are adapted to or dependent upon that fire regime. Fire creates a mosaic of different habitat patches, each at a different stage of succession. Different species of plants, animals, and microbes specialize in exploiting a particular stage, and by creating these different types of patches, fire allows a greater number of species to exist within a landscape.

Prevention and protection systems

Main articles: Wildfire § Prevention, Fire prevention, and Fire protection

Wildfire prevention programs around the world may employ techniques such as wildland fire use and prescribed or controlled burns. Wildland fire use refers to any fire of natural causes that is monitored but allowed to burn. Controlled burns are fires ignited by government agencies under less dangerous weather conditions.

Fire fighting services are provided in most developed areas to extinguish or contain uncontrolled fires. Trained firefighters use fire apparatus, water supply resources such as water mains and fire hydrants or they might use A and B class foam depending on what is feeding the fire.

Fire prevention is intended to reduce sources of ignition. Fire prevention also includes education to teach people how to avoid causing fires. Buildings, especially schools and tall buildings, often conduct fire drills to inform and prepare citizens on how to react to a building fire. Purposely starting destructive fires constitutes arson and is a crime in most jurisdictions.

Model building codes require passive fire protection and active fire protection systems to minimize damage resulting from a fire. The most common form of active fire protection is fire sprinklers. To maximize passive fire protection of buildings, building materials and furnishings in most developed countries are tested for fire-resistance, combustibility and flammability. Upholstery, carpeting and plastics used in vehicles and vessels are also tested.

Where fire prevention and fire protection have failed to prevent damage, fire insurance can mitigate the financial impact.

See also

- Aodh (given name)

- Bonfire

- The Chemical History of a Candle

- Colored fire

- Control of fire by early humans

- Deflagration

- Fire (classical element)

- Fire investigation

- Fire lookout

- Fire lookout tower

- Fire making

- Fire pit

- Fire safety

- Fire triangle

- Fire whirl

- Fire worship

- Flame test

- Life Safety Code

- List of fires

- List of light sources

- Phlogiston theory

- Piano burning

- Prometheus, the Greek mythological figure who gave mankind fire

- Pyrokinesis

- Pyrolysis

- Pyromania

- Self-immolation

References

Notes

Citations