| Revision as of 22:52, 28 October 2005 view source69.246.98.216 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:33, 6 January 2025 view source Cagliost (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions17,936 editsNo edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Space primarily used for preparation and storage of food}} | |||

| A '''kitchen''' is a ] used for ] preparation. A modern kitchen is typically equipped with a ] or ] and has a ] with water on tap for cleaning food and dishwashing. Modern kitchens often also feature a ]. Some installations to store food usually also are present, either in the form of an adjacent ] or more commonly ]s and a ]. | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| ]-style kitchen in ]]] | |||

| A '''kitchen''' is a ] or part of a room used for ] and ] in a dwelling or in a commercial establishment. A modern middle-class residential kitchen is typically equipped with a ], a ] with hot and cold running water, a ], and worktops and kitchen ] arranged according to a ]. Many households have a ], a ], and other electric appliances. The main functions of a kitchen are to store, prepare and cook food (and to complete related tasks such as ]). The room or area may also be used for ] (or small meals such as breakfast), ] and ]. The design and construction of kitchens is a huge market all over the world.<!-- This article is about the kitchen as a room. Details about pans and cookware are not needed in lead. --> | |||

| Although the main function of a kitchen is ], it can be the center of other activities as well, especially within ]s, depending on its size, furnishing, and ]. If a ] is present, ] and drying ] is also done in the kitchen. The kitchen may also be the place where the family ], provided it is large enough. Sometimes, it is the most comforting room in a house, where family and visitors tend to congregate. | |||

| Commercial kitchens are found in ]s, ]s, ]s, ]s, educational and workplace facilities, army barracks, and similar establishments. These kitchens are generally larger and equipped with bigger and more heavy-duty equipment than a residential kitchen. For example, a large restaurant may have a huge walk-in refrigerator and a large commercial dishwasher machine. In some instances, commercial kitchen equipment such as commercial sinks is used in household settings as it offers ease of use for food preparation and high durability.<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://www.homedecorexpert.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-using-a-commercial-sink-at-home.html|title=The Pros and Cons of Using A Commercial Sink at Home – Home Decor Expert and|date=2018-06-14|work=Home Decor Expert|access-date=2018-07-22|archive-date=2019-03-30|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330022733/https://www.homedecorexpert.com/the-pros-and-cons-of-using-a-commercial-sink-at-home.html|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1982/12/09/garden/the-commercial-kitchen-at-home-pros-and-cons-by-carol-vogel.html|title=The commercial kitchen at home: pros and cons |author=Vogel, Carol|date=1982-12-09|work=]}}</ref> | |||

| ], ], and ] among other amenities.]] | |||

| In developed countries, commercial kitchens are generally subject to ] laws. They are inspected periodically by public-health officials, and forced to close if they do not meet hygienic requirements mandated by law.<ref>{{Cite web |title=What Should Be Done Following Health Violations From an Inspection? |url=https://www.fooddocs.com/post/what-should-be-done-following-health-violations-from-an-inspection |access-date=2024-07-22 |website=www.fooddocs.com |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == The evolution of the kitchen == | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The development of the kitchen has been intricately and intrinsically linked with the development of the cooking range or ]. Until the ], open ] was the sole means of heating food, and the architecture of the kitchen reflected this. When technical advances brought new ways to heat food in the 18th and 19th centuries, ]s took advantage of newly-gained flexibility to bring fundamental changes to the kitchen. ] on tap only became gradually available during ]; before, water had to be collected from the nearest ] and heated in the kitchen. | |||

| ===Middle Ages=== | |||

| ]an Renaissance kitchen was driven automatically by a propeller—the black cloverleaf-like structure in the upper left]] | |||

| Early medieval European ]s had an open fire under the highest point of the building. The "kitchen area" was between the entrance and the fireplace. In wealthy homes, there was typically more than one kitchen. In some homes, there were upwards of three kitchens. The kitchens were divided based on the types of food prepared in them.<ref>Thompson, Theodor (1992) ''Medieval Homes'', Sampson Lowel House</ref> | |||

| === Early history === | |||

| The kitchen might be separate from the great hall due to the smoke from cooking fires and the chance the fires may get out of control.<ref>{{citation |first1=Neil |last1=Christie |first2=Oliver |last2=Creighton |first3=Matt |last3=Edgeworth|first4=Helena |last4=Hamerow |author-link1=Neil Christie |author-link4=Helena Hamerow |title=Transforming Townscapes: From burgh to borough: the archaeology of Wallingford, AD 800–1400 |series=The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series |number=35 |isbn=978-1-909662-09-4 |location=Oxford |year=2013 |publisher=Society for Medieval Archaeology|page=201}}</ref> Few medieval kitchens survive as they were "notoriously ephemeral structures".<ref>{{citation |first1=Oliver |last1=Creighton |first2=Neil |last2=Christie |contribution=The Archaeology of Wallingford Castle: a summary of the current state of knowledge |title=Wallingford: The Castle and the Town in Context |editor-first1=K. S. B. |editor-last1=Keats-Rohan |editor-first2=Neil |editor-last2=Christie |editor-link2=Neil Christie |editor-first3=David |editor-last3=Roffe |series=BAR British Series |publisher=Archaeopress |isbn=978-1-4073-1418-1 |location=Oxford |year=2015|page=13}}</ref> | |||

| The houses in ] were commonly of the ]-type: the rooms were arranged around a central courtyard. In many such homes, a covered but otherwise open patio served as the kitchen. Homes of the wealthy had the kitchen as a separate room, usually next to a bathroom (so that both rooms could be heated by the kitchen fire), both rooms being accessible from the court. In such houses, there was often a separate small storage room in the back of the kitchen used for storing food and kitchen utensils. | |||

| In the ], common folk in cities often had no kitchen of their own; they did their ] in large public kitchens. Some had small mobile ] stoves, on which a fire could be lit for cooking. Wealthy ] had relatively well-equipped kitchens. In a Roman ], the kitchen was typically integrated into the main building as a separate room, set apart for practical reasons of ] and sociological reasons of the kitchen being operated by ]. The ] was typically on the floor, placed at a wall--sometimes raised a little bit--such that one had to kneel to cook. There were no ]s. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] medieval kitchen was driven automatically by a propeller—the black cloverleaf-like structure in the upper left.]] | |||

| ===Colonial America=== | |||

| Early medieval European ]s had an open fire under the highest point of the building. The "kitchen area" was between the entrance and the fireplace. In place of a chimney, these early buildings had a hole in the roof through which some of the smoke could escape. Besides cooking, the fire also served as a source of heat and light to the single-room building. A similar design can be found in the ] longhouses of ]. | |||

| In ], as in other colonies of ] during ], kitchens were often built as separate rooms and were located behind the ] and ] or ]. One early record of a kitchen is found in the 1648 inventory of the estate of a John Porter of ]. The inventory lists goods in the house "over the kittchin" and "in the kittchin". The items listed in the kitchen were: ]s, ], ], iron, arms, ammunition, ], ] and "other implements about the room".<ref>{{cite book|author=Trumbull, J. Hammond |year=1850|url=https://archive.org/stream/publicrecordsofc001conn#page/476/mode/2up |title=The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut 1636–1776|volume= 1|page= 476|publisher=Hartford, Brown & Parsons}}</ref> | |||

| Technological developments such as the ] and the ] enabled more efficient use of space and fuel. | |||

| In the larger homesteads of European nobles, the kitchen was sometimes in a separate ] building to keep the main building, which served social and official purposes, free from smoke. | |||

| ===Rationalization=== | |||

| The first known stoves in ] date from about the same time. The earliest findings are from the ] (] to ]). These stoves, called ''kamado'', were typically made of clay and mortar; they were fired with ] or ] through a hole in the front and had a hole in the top, into which a pot could be hanged by its rim. This type of stove remained in use for centuries to come, with only minor modifications. Like in Europe, the wealthier homes had a separate building which served for cooking. A kind of open fire pit fired with charcoal, called ''irori'', remained in use as the secondary stove in most homes until the ] (] to ]). A ''kamado'' was used to cook the staple food, for instance ], while ''irori'' served both to cook side dishes and as a heat source. | |||

| A stepping stone to the modern fitted kitchen was the ], designed by ] for ] projects in 1926. This kitchen measured {{convert|1.9|by|3.4|m}}, and was built to optimize kitchen efficiency and lower building costs. The design was the result of detailed time-motion studies and interviews with future tenants to identify what they needed from their kitchens. Schütte-Lihotzky's fitted kitchen was built in some 10,000 apartments in housing projects erected in ] in the 1930s.<ref>Rawsthorn, Alice (2010-09-27) . ''New York Times''</ref> | |||

| ==Materials== | |||

| The kitchen remained largely unaffected by architectural advances throughout the middle ages; open fire remained the only method of heating food. European medieval kitchens were dark, smokey, and sooty places, whence their name ''"smoke kitchen"''. | |||

| The Frankfurt Kitchen of 1926 was made of several materials depending on the application. The modern built-in kitchens of today use ]s or MDF, decorated with a variety of materials and finishes including wood veneers, lacquer, glass, melamine, laminate, ceramic and eco gloss. Very few manufacturers produce home built-in kitchens from stainless steel. Until the 1950s, steel kitchens were used by architects, but this material was displaced by the cheaper particle board panels sometimes decorated with a steel surface. | |||

| ==Domestic kitchen planning== | |||

| In European medieval cities around the ] to ], the kitchen still used an open fire ] in the middle of the room. In wealthy homes, the ground floor was often used as a stable while the kitchen was located on the floor above, like the bedroom and the hall. In Japanese homes, the kitchen started to become a separate room within the main building at that time. | |||

| {{multiple issues|section=1| | |||

| {{refimprove section|date=January 2024}} | |||

| {{essay-like|section|date=January 2024}} | |||

| }} | |||

| ] principles to the home]] | |||

| ] using ] principles]] | |||

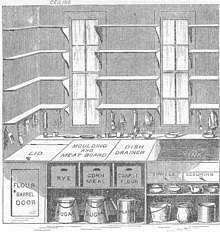

| Domestic (or residential) kitchen design is a relatively recent discipline. The first ideas to optimize the work in the kitchen go back to ]'s ''A Treatise on Domestic Economy'' (1843, revised and republished together with her sister ] as ''The American Woman's Home'' in 1869). Beecher's "model kitchen" propagated for the first time a systematic design based on early ]. The design included regular shelves on the walls, ample workspace, and dedicated storage areas for various food items. Beecher even separated the functions of preparing food and cooking it altogether by moving the stove into a compartment adjacent to the kitchen. | |||

| ] published from 1913 a series of articles on "New Household Management" in which she analyzed the kitchen following ] principles of efficiency, presented detailed time-motion studies, and derived a kitchen design from them. Her ideas were taken up in the 1920s by architects in Germany and ], most notably ], Erna Meyer, ] and ], who designed the first fitted kitchen for the ], which was completed in 1923.<ref>{{cite news | last = Moore | first = Rowan | title = Bauhaus at 100: its legacy in five key designs | newspaper = ] | date = 2019-01-21 | url = https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/gallery/2019/jan/21/bauhaus-at-100-its-legacy-in-five-key-designs | access-date = 2019-01-21}}</ref> Similar design principles were employed by Schütte-Lihotzky for her famous ], designed for ]'s ''Römerstadt'', a social housing project in Frankfurt, in 1927. | |||

| In ]s and ], the living and working areas were separated; the kitchen was moved to a separate building, and thus couldn't serve anymore to heat the living rooms. | |||

| While this "work kitchen" and variants derived from it were a great success for tenement buildings, homeowners had different demands and did not want to be constrained by a {{convert|6.4|m2|adj=on}} kitchen. Nevertheless, the kitchen design was mostly ad-hoc following the whims of the architect. In the ], the "Small Homes Council", since 1993 the "Building Research Council", of the School of Architecture of the ] was founded in 1944 with the goal to improve the state of the art in home building, originally with an emphasis on standardization for cost reduction. It was there that the notion of the '']'' was formalized: the three main functions in a kitchen are storage, preparation, and cooking (which Catharine Beecher had already recognized), and the places for these functions should be arranged in the kitchen in such a way that work at one place does not interfere with work at another place, the distance between these places is not unnecessarily large, and no obstacles are in the way. A natural arrangement is a ], with the refrigerator, the sink, and the stove at a vertex each. | |||

| ] cooks tended a fire and endured smoke in this ] farmhouse smoke kitchen.]] | |||

| With the advent of the chimney, the hearth moved from the center of the room to one wall, and the first brick-and-mortar hearths were built. The fire was lit on top of the construction; a vault underneath served to store wood. Pots made of ], ], or ] started to replace the ] used earlier. The temperature was controlled by hanging the pot higher or lower over the fire, or placing it on a ] or directly on the hot ashes. | |||

| ] invented an automated system for a rotating spit for spit-roasting: a propeller in the chimney made the spit turn all by itself. This kind of system was widely used in wealthier homes. | |||

| Using open fire for cooking (and heating) was risky; fires devastating whole cities occurred frequently. | |||

| Beginning in the late ], kitchens in Europe lost their home-heating function even more and were increasingly moved from the living area into a separate room. The living room was now heated by ]s, operated from the kitchen, which offered the huge advantage of not filling the room with smoke. Freed from smoke and dirt, the living room thus could become to serve as an area for social functions and increasingly became a showcase for the owner's wealth and was sometimes prestigiously furnished. In the upper classes, cooking and the kitchen were the domain of the ]s, and the kitchen was set apart from the living rooms, sometimes even far from the dining room. Poorer homes often did not have a separate kitchen yet; they kept the one-room arrangement where all activities took place, or at the most had the kitchen in the entrance hall. | |||

| The medieval smoke kitchen remained common, especially in rural ]s and generally in poorer homes, until much later. In a few European farmhouses, the smoke kitchen was in regular use until the middle of the ]. These houses often had no chimney, but only a smoke hood above the fireplace, made of wood and covered with clay, and used to smoke meat. The smoke then rose more or less freely, warming the upstairs rooms and protecting the woodwork from vermin. | |||

| === Colonial American kitchens === | |||

| In the ]n kitchen, the same distinction as for the medieval European kitchen is visible. The early settlers in the north often had no separate kitchen; a fireplace in a corner of the ] served as the kitchen space. Later, the kitchen did become a separate room, but remained within the building. | |||

| The development in the southern states was quite different, but then, so were the ] and ] conditions. In southern estates, the kitchen was often relegated to an outhouse, separated from the ], for much of the same reasons as in the feudal kitchen in medieval Europe: the kitchen was operated by ]s, and their working place had to be separated from the living area of the masters by the social standards of the time. In addition, the area's warm climate made operating a kitchen quite unpleasant, especially in the ]. | |||

| Completely separated "summer kitchens" also developed on larger farms further north to avoid that the main house was heated by the preparation of the meals for the harvest workers or tasks like ]. | |||

| === Industrialization === | |||

| Technological advances during ] brought major changes to the kitchen. Iron stoves, which enclosed the fire completely and were more efficient, appeared. Early models included the ] around ], which was a ] stove intended for heating, not for cooking. ] in ] designed his "Rumford stove" around ]. This stove was much more energy efficient than earlier stoves; it used one fire to heat several pots, which were hung into holes on top of the stove and were thus heated from all sides instead of just from the bottom. However, his stove was designed for large kitchens; it was too big for domestic use. The "Oberlin stove" was a refinement of the technique that resulted in a size reduction; it was ]ed in the U.S. in ] and became a commercial success with some 90,000 units sold over the next 30 years. These stoves were still fired with ] or ]. Although the first ] were installed in ], ], and ] at the beginning of the ] and the first U.S. patent on a gas stove was granted in ], it wasn't until the late ] that using gas for lighting and cooking became commonplace in urban areas. | |||

| The ] in the second half of the 19th century induced other significant changes that ultimately would also change the kitchen. Out of sheer necessity, cities began planning and building water distribution pipes into homes, and built ]s to deal with the ]. ]s were laid; gas was used first for lighting purposes, but once the network had grown sufficiently, it became available also for heating and cooking on gas stoves. At the turn of the 20th century, ] had been mastered well enough to become a commercially viable alternative to gas and slowly started replacing the latter. But like the gas stove, the electrical stove had a slow start. The first electrical stove had been presented in ] at the ], but it wasn't until the ] that the technology was stable enough and began to take off. | |||

| Industrialization also caused social changes. The new ] ] in the cities was housed under generally poor conditions. Whole families lived in small one or two-room ]s in tenement buildings up to six stories high, badly aired and with insufficient lighting. Sometimes, they shared apartments with "night sleepers", unmarried men that paid for a bed at night. The kitchen in such an apartment was often used as a living and sleeping room, and even as a ]. Water had to be fetched from wells and heated on the stove. Water pipes were laid only towards the end of the 19th century, and then often only with one tap per building or per story. Brick-and-mortar stoves fired with coal remained the norm until well into the second half of the century. Pots and kitchenware typically were stored on open shelves, and parts of the room could be separated from the rest using simple curtains. | |||

| In contrast, there were no dramatic changes for the upper classes. The kitchen, located in the ] or the ], continued to be operated by servants. In some houses, water ]s were installed, and some even had kitchen sinks and drains (but no water on tap yet, except for some feudal kitchens in castles). The kitchen became a much cleaner space with the advent of "cooking machines", closed stoves made of iron plates and fired by wood and increasingly charcoal or coal, and that had ]s connected to the chimney. For the servants the kitchen continued to serve also as a sleeping room; they slept either on the floor, or later in narrow spaces above a lowered ceiling, for the new stoves with their smoke outlet no longer required a high ceiling in the kitchen. The kitchen floors were tiled; kitchenware was neatly stored in ]s to protect them from dust and steam. A large table served as a workbench; there were at least as many chairs as there were servants, for the table in the kitchen also doubled as the eating place for the servants. | |||

| The middle class tried to imitate the luxurious dining styles of the upper class as best as it could. Living in smaller apartments, the kitchen was the main room—here, the family lived. The study or living room was saved for special occasions such as an occasional dinner invitation. Because of this, these middle-class kitchens often were more homely than those of the upper class, where the kitchen was a work-only room occupied only by the servants. Besides a cupboard to store the ], there were a table and chairs, where the family would dine, and sometimes—if space allowed—even a fauteuil or a couch. | |||

| Gas pipes were laid only in the late 19th century, and gas stoves started to replace the older coal-fired stoves. Gas was more expensive than coal, though, and thus the new technology first was installed in the wealthier homes. Where workers' apartments were equipped with a gas stove, gas distribution would go through a coin meter. | |||

| In rural areas, the older technology using coal or wood stoves or even brick-and-mortar open fireplaces remained common throughout. Gas and water pipes were first installed in the big cities; small villages were connected only much later. | |||

| === Rationalization === | |||

| The trend to increasing gasification and electrification continued at the turn of the ]. In industry, it was the phase of rationalisation, where work processes were attempted to be streamlined. ] was born, and ] were used to optimize processes. These ideas also spilled over into domestic kitchen architecture due to a growing trend that called for a professionalization of household work, started in the mid-] by ] and amplified by ]'s publications in the ]. | |||

| ] was designed after ] principles.]] | |||

| Working class women frequently worked in factories to ensure the family's survival, as the men's wages often did not suffice. ] projects led to the next milestone: the "]". Born in ], this kitchen measured 1.9m by 3.4m, with a standard layout. It was built for two purposes: to optimize kitchen work to reduce cooking time (so that women would have more time for the factory) and to lower the cost of building decently-equipped kitchens. The design, created by ], was the result of detailed time-motion studies and heavily influenced by the railway dining car kitchens of the period. It was built in some 10000 apartments in a social housing project of ] ] in ]. | |||

| The initial reception was heavily critical: people were not accustomed to the changed processes also designed by Schütte-Lihotzky; it was so small that only one person could work in it; some storage spaces intended for raw loose food ingredients such as ] were reachable by children. But the Frankfurt kitchen embodied a standard for the rest of the ] in rental apartments: the "work kitchen". Too small to live or dine in, it was soon criticized as "exiling the women in the kitchen", but the post-] conservatism coupled with economic reasons prevailed. The kitchen once more was seen as a work place that needed to be separated from the living areas. Practical reasons also played a role in this development: just as in the bourgeois homes of the past, one reason for separating the kitchen was to keep the steam and smells of cooking out of the living room. | |||

| === Technicalization === | |||

| The idea of standardized dimensions and layout developed for the Frankfurt kitchen took hold. The equipment used remained a standard for years to come: hot and cold water on tap and a kitchen sink and an electrical or gas stove and oven. Not much later, the ] was added as a standard item. The concept was refined in the "Swedish kitchen" using ] with wooden fronts for the kitchen cabinets. Soon the concept was amended by the use of smooth synthetic door and drawer fronts, first in white, recalling a sense of cleanliness and alluding to sterile lab or hospital settings, but soon after in lively, friendly colors, too. A trend began in the ] in the ] to equip the kitchen with electrified small and large kitchen appliances such as ]s, ]s, and later also ]s. Following the end of ], massive demand in ] for low-price, high-tech consumer goods led to Western European kitchens being designed to accommodate new appliances such as refrigerators and electric/gas cookers. | |||

| Parallel to this development in tenement buildings went the evolution of the kitchen in homeowner's houses. There, the kitchens usually were somewhat larger, suitable for everyday use as a dining room, but otherwise the ongoing technicalization was the same, and the use of unit furniture became a standard also in this market sector. | |||

| General technocentric enthusiasm even led some designers to take the "work kitchen" approach even further, culminating in futuristic designs like ]'s "kitchen satellite" (], commissioned by the ] high-end kitchen manufacturer ] for an exhibit), in which the room was reduced to a ball with a chair in the middle and all appliances at arm's length, an optimal arrangement maybe for "applying heat to food", but not necessarily for actual cooking. Such extravaganzas remained outside the norm, though. | |||

| In the former ] countries, the official ] viewed cooking as a mere necessity, and women should work "for the society" in factories, not at home. Also, housing had to be built at low costs and quickly, which led directly to the standardized apartment block using prefabricated slabs. The kitchen was reduced to the max and the "work kitchen" paradigm taken to its extremes: in ] for instance, the standard tenement block of the model "P2" had tiny 4 ] kitchens in the inside of the building (no windows), connected to the dining and living room of the 55 m² apartment and separated from the latter by a pass-through or a window. | |||

| === Free for all === | |||

| Starting in the ], the perfection of the ] allowed an open kitchen again, integrated more or less with the living room without causing the whole apartment or house to smell. Before that, only a few earlier experiments, typically in newly built upper middle class family homes, had open kitchens. Examples are ]'s ''House Willey'' (]) and ''House Jacobs'' (]). Both had open kitchens, with high ceilings (up to the roof) and were aired by ]s. The extractor hood made it possible to build open kitchens in apartments, too, where both high ceilings and skylights were not possible. | |||

| The re-integration of the kitchen and the living area went hand in hand with a change in the perception of cooking: increasingly, cooking was seen as a ] and sometimes social act instead of work, especially in upper social classes. Besides, many families also appreciated the trend towards open kitchens, as it made it easier for the parents to supervise the kids while cooking. The enhanced status of cooking also made the kitchen a prestige object for showing off one's wealth or cooking professionalism. Some ]s have capitalized on this "object" aspect of the kitchen by designing freestanding "kitchen objects". However, like their precursor, Colani's "kitchen satellite", such futuristic designs are exceptions. | |||

| Another reason for the trend back to open kitchens (and a foundation of the "kitchen object" philosophy) is also to be found in the changes in the food alimentation. Whereas in the ] most cooking started out with raw ingredients and a meal had to be prepared for real, the advent of ]s and pre-prepared ] has changed the cooking habits of many people, who consequently used the kitchen less and less. For others, who followed the "cooking as a social act" trend, the open kitchen had the advantage that they could be with their guests while cooking, and for the "creative cooks" it might even become a stage for their cooking performance. | |||

| == Domestic kitchen planning == | |||

| ] principles to the home.]] | |||

| Domestic kitchen design ''per se'' is a relatively recent discipline. The first ideas to optimize the work in the kitchen go back to ]'s ''A Treatise on Domestic Economy'' (], revised and republished together with her sister ] as ''The American Woman's Home'' in ]). Beecher's "model kitchen" propagated for the first time a systematic design based on early ]. The design included regular shelves on the walls, ample work space, and dedicated storage areas for various food items. Beecher even separated the functions of preparing food and cooking it altogether by moving the stove into a compartment adjacent to the kitchen. | |||

| ] published from ] a series of articles on "New Household Management" in which she analyzed the kitchen following ] priciples, presented detailed time-motion studies, and derived a kitchen design from them. Her ideas were taken up in the ] by architects in ] and ], most notably ], ], and ]. A social housing project in Frankfurt (the ''Römerstadt'' of architect ]) realized in ]/] was the breakthrough for her ], which embodied this new notion of efficiency in the kitchen. | |||

| While this "work kitchen" and variants derived from it were a great success for tenement buildings, home owners had different demands and didn't want to be constrained by a 6.4 ] kitchen. Nevertheless, kitchen design was mostly ad-hoc following the whims of the architect. In the ], the "Small Homes Council", since ] the "Building Research Council", of the School of Architecture of the ] was founded in ] with the goal to improve the state of the art in home building, originally with an emphasis on standardization for cost reduction. It was there that the notion of the ''"kitchen work triangle"'' was formalized: the three main functions in a kitchen are storage, preparation, and cooking (which Catherine Beecher had already recognized), and the places for these functions should be arranged in the kitchen in such a way that work at one place does not interfere with work at another place, the distance between these places is not unnecessarily large, and no obstacles are in the way. A natural arrangement is a ], with the refrigerator, the sink, and the stove at a vertex each. | |||

| This observation led to a few common kitchen forms, commonly characterized by the arrangement of the kitchen cabinets and sink, stove, and refrigerator: | This observation led to a few common kitchen forms, commonly characterized by the arrangement of the kitchen cabinets and sink, stove, and refrigerator: | ||

| * A ''single |

* A ''single-file kitchen'' (also known as a one-way galley or a straight-line kitchen) has all of these along one wall; the work triangle degenerates to a line. This is not optimal, but often the only solution if space is restricted. This may be common in an attic space that is being converted into a living space, or a studio apartment. | ||

| * The ''double |

* The ''double-file kitchen (or two-way galley)'' has two rows of cabinets on opposite walls, one containing the stove and the sink, the other the refrigerator. This is the classical work kitchen and makes efficient use of space. | ||

| * In the ''L-kitchen'', the cabinets occupy two adjacent walls. Again, the work triangle is preserved, and there may even be space for an additional table at a third wall, provided it |

* In the ''L-kitchen'', the cabinets occupy two adjacent walls. Again, the work triangle is preserved, and there may even be space for an additional table at a third wall, provided it does not intersect the triangle. | ||

| * A ''U-kitchen'' has cabinets along three walls, typically with the sink at the base of the "U". This is a typical work kitchen, too, unless the two other cabinet rows are short enough to place a table |

* A ''U-kitchen'' has cabinets along three walls, typically with the sink at the base of the "U". This is a typical work kitchen, too, unless the two other cabinet rows are short enough to place a table on the fourth wall. | ||

| * A ''G-kitchen'' has cabinets along three walls, like the U-kitchen, and also a partial fourth wall, often with a double basin sink at the corner of the G shape. The G-kitchen provides additional work and storage space and can support two work triangles. A modified version of the G-kitchen is the ''double-L'', which splits the G into two L-shaped components, essentially adding a smaller L-shaped island or peninsula to the L-kitchen. | |||

| * The ''block kitchen'' is a more recent development, typically found in open kitchens. Here, the stove or both the stove and the sink are placed where an L or U kitchen would have a table, in a freestanding "island", separated from the other cabinets. In a closed room, this doesn't make much sense, but in an open kitchen, it makes the stove accessible from all sides such that two persons can cook together, and allows for contact with guests or the rest of the family, for the cook doesn't face the wall anymore. | |||

| ] | |||

| * The ''block kitchen (or island)'' is a more recent development, typically found in open kitchens. Here, the stove or both the stove and the sink are placed where an L or U kitchen would have a table, in a free-standing "island", separated from the other cabinets. In a closed room, this does not make much sense, but in an open kitchen, it makes the stove accessible from all sides such that two persons can cook together, and allows for contact with guests or the rest of the family since the cook does not face the wall any more. Additionally, the kitchen island's counter-top can function as an overflow surface for serving buffet-style meals or sitting down to eat breakfast and snacks. | |||

| Modern kitchens often have enough informal space to allow for people to eat in it without having to use the formal ]. |

In the 1980s, there was a backlash against industrial kitchen planning and cabinets with people installing a mix of work surfaces and free standing furniture, led by kitchen designer ] and his concept of the "unfitted kitchen". Modern kitchens often have enough informal space to allow for people to eat in it without having to use the formal ]. Such areas are called "breakfast areas", "breakfast nooks" or "breakfast bars" if space is integrated into a kitchen counter. Kitchens with enough space to eat in are sometimes called "eat-in kitchens". During the 2000s, flat pack kitchens were popular for people doing ] renovating on a budget. The flat pack kitchens industry makes it easy to put together and mix and matching doors, bench tops and cabinets. In flat pack systems, many components can be interchanged. | ||

| In larger homes, where the owners might have meals prepared by a household staff member, the home may have a ''chef's kitchen''. This typically differs from a normal domestic kitchen by having multiple ovens (possibly of different kinds for different kinds of cooking), multiple sinks, and warming drawers to keep food heated between cooking and service. | |||

| == Other kitchen types == | |||

| ] can prepare fresh food for hundreds in this 20th century ] kitchen.]] | |||

| ==Other types== | |||

| ] and ] kitchens found in ]s, ]s, army barracks and similar establishments are generally (in developed countries) subject to ] laws. They are inspected periodically by public-health officials, and forced to close if they don't meet hygienic requirements mandated by law. | |||

| ] kitchen]] | |||

| ] training kitchen of ] in the ]]] | |||

| ] and ] kitchens found in ]s, ]s, educational and workplace facilities, army barracks, and similar institutions are generally (in developed countries) subject to ] laws. They are inspected periodically by public health officials and forced to close if they do not meet hygienic requirements mandated by law. | |||

| Canteen kitchens (and castle kitchens) were often the places where new technology was used first. |

Canteen kitchens (and castle kitchens) were often the places where new technology was used first. For instance, ]'s "energy saving stove", an early 19th-century fully closed iron stove using one fire to heat several pots, was designed for large kitchens; another thirty years passed before they were adapted for domestic use. | ||

| As of 2017, restaurant kitchens usually have tiled walls and floors and use stainless steel for other surfaces (workbench, but also door and drawer fronts) because these materials are durable and easy to clean. Professional kitchens are often equipped with gas stoves, as these allow ] to regulate the heat more quickly and more finely than electrical stoves. Some special appliances are typical for professional kitchens, such as large installed ]s, ], or a ]. | |||

| The ] and ] trends have |

The ] and ] trends have changed the manner in which restaurant kitchens operate. Some of these type restaurants may only "finish" convenience food that is delivered to them or just reheat completely prepared meals. At the most they may ] a ] or a ]. But in the early 21st century, c-stores (convenience stores) are attracting greater market share by performing more food preparation on-site and better customer service than some fast food outlets.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.qsrmagazine.com/exclusives/c-stores-eating-your-lunch |author= Blank, Christine|title=C-Stores Eating Your Lunch|journal=QSR Magazine|date=9 January 2014}}</ref> | ||

| The kitchens in ] ]s |

The kitchens in ] ]s have presented special challenges: space is limited, and, personnel must be able to serve a great number of meals quickly. Especially in the early history of railways, this required flawless organization of processes; in modern times, the ] and prepared meals have made this task much easier. Kitchens aboard ]s, ] and sometimes ] are often referred to as ]. On ]s, galleys are often cramped, with one or two burners fueled by an ] bottle. Kitchens on ]s or large ]s, by contrast, are comparable in every respect with restaurants or canteen kitchens. | ||

| On passenger ]s, the kitchen is reduced to a ]. The crew's role is to heat and serve in-flight meals delivered by a ] company. An extreme form of the kitchen occurs in space, ''e.g.'', aboard a ] (where it is also called the "galley") or the ]. The ]s' food is generally completely prepared, ], and sealed in plastic pouches before the flight. The kitchen is reduced to a rehydration and heating module. | |||

| Outdoor areas in which food is prepared are generally not considered to be kitchens, although an outdoor area set up for regular food preparation, for instance when ], might be called an "outdoor kitchen". Military camps and similar temporary settlements of ]s may have dedicated kitchen tents. | |||

| Outdoor areas where food is prepared are generally not considered kitchens, even though an outdoor area set up for regular food preparation, for instance when ], might be referred to as an "outdoor kitchen". An outdoor kitchen at a ] might be placed near a well, water pump, or water tap, and it might provide tables for food preparation and cooking (using portable camp stoves). Some campsite kitchen areas have a large tank of ] connected to burners so that campers can cook their meals. Military camps and similar temporary settlements of ]s may have dedicated kitchen tents, which have a vent to enable cooking smoke to escape. | |||

| ] in ].]] | |||

| In Schools where ] (previously known as ]) is taught, there will be a series of kitchens with multiple equipment (similar in some respects to ]) solely for the purpose of teaching. These will consist of between 6 and 12 workstations, each with their own ], ] and kitchen utensils. | |||

| In schools where home economics, ] (previously known as "]"), or ] are taught, there are typically a series of kitchens with multiple equipment (similar in some respects to ]) solely for the purpose of teaching. These consist of multiple workstations, each with its own ], ], and kitchen utensils, where the teacher can show students how to prepare food and cook it. | |||

| == Kitchens around the world== | |||

| ==By region== | |||

| * ]s | |||

| ===China=== | |||

| ]nese '']'' style kitchen, ]]] | |||

| Kitchens in China are called {{lang|zh|chúfáng(厨房)}}. More than 3000 years ago, the ancient Chinese used the ] for cooking food. The ding was developed into the ] and pot used today. In Chinese spiritual tradition, a ] watches over the kitchen for the family and reports to the ] annually about the family's behavior. On Chinese New Year's Eve, families would gather to pray for the kitchen god to give a good report to heaven and wish him to bring back good news on the fifth day of the New Year. | |||

| The most common cooking equipment in Chinese family kitchens and restaurant kitchens are woks, steamer baskets and pots. The fuel or heating resource was also an important technique to practice the cooking skills. Traditionally Chinese were using wood or straw as the fuel to cook food. A Chinese chef had to master flaming and heat radiation to reliably prepare traditional recipes. Chinese cooking will use a pot or wok for pan-frying, stir-frying, deep frying or boiling. | |||

| == |

===Japan=== | ||

| {{main|Japanese kitchen}} | |||

| * Miklautz, E. et al. (Ed.): ''Die Küche — Zur Geschichte eines architektonischen, sozialen und imaginativen Raums'', Verlag Böhlau, Vienna 1999; ISBN 3-205-99076-5. In German. | |||

| ], ], ].]] | |||

| *Two collections of architecture students' works on the kitchen: (] file, 3 ]) and (] file, 5 ]). Both in German. | |||

| Kitchens in Japan are called '''Daidokoro''' (台所; lit. "kitchen"). Daidokoro is the place where food is prepared in a ]. Until the ], a kitchen was also called ''kamado'' (かまど; lit. ]) and there are many sayings in the ] that involve kamado as it was considered the symbol of a house and the term could even be used to mean "family" or "household" (similar to the English word "hearth"). When separating a family, it was called ''Kamado wo wakeru'', which means "divide the stove". ''Kamado wo yaburu'' (lit. "break the stove") means that the family was bankrupt. | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| ===India=== | |||

| * Andritzky, M. (Ed.): ''Oikos: Von der Feuerstelle zur Mikrowelle'', Anabes, Giessen 1992; ISBN 3-870-38669-X. In ]; out of print. | |||

| ] in ], ]]] | |||

| * ] and ]: ''The American Woman's Home'', ]. The text is vailable at ] at . | |||

| * Harrison, M.: ''The Kitchen in History'', Osprey; 1972; ISBN 0-850-45068-3; out of print. | |||

| * Lupton, E. and Miller, J. A.: ''The Bathroom, the Kitchen, and the Aesthetics of Waste'', Princeton Architectural Press; 1996; ISBN 1-568-98096-5. The introduction is available . In ]. | |||

| * Snodgrass, M. E.: ''Encyclopedia of Kitchen History''; Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers; (November 2004); ISBN 1-579-58380-6. | |||

| In India, a kitchen is called a "Rasoi" (in Hindi\Sanskrit) or a "Swayampak ghar" in Marathi, and there exist many other names for it in the various regional languages. Many different methods of cooking exist across the country, and the structure and the materials used in constructing kitchens have varied depending on the region. For example, in the north and central India, cooking used to be carried out in clay ovens called "chulha" (also ''chullha'' or ''chullah''), fired by wood, coal or dried cow dung. In households where members observed vegetarianism, separate kitchens were maintained to cook and store vegetarian and non-vegetarian food. Religious families often treat the kitchen as a sacred space. Indian kitchens are built on an Indian architectural science called vastushastra. The Indian kitchen vastu is of utmost importance while designing kitchens in India. Modern-day architects also follow the norms of vastushastra while designing Indian kitchens across the world. | |||

| == External links == | |||

| While many kitchens belonging to poor families continue to use clay stoves and the older forms of fuel, the urban middle and upper classes usually have gas stoves with cylinders or piped gas attached. Electric cooktops are rarer since they consume a great deal of electricity, but microwave ovens are gaining popularity in urban households and commercial enterprises. Indian kitchens are also supported by ] and solar energy as fuel. World's largest solar energy<ref>{{Cite news|url=http://inhabitat.com/world%E2%80%99s-largest-solar-kitchen-in-india-can-cook-upto-38500-meals-per-day/|title=World's Largest 38500-meal Solar Kitchen in India|access-date=2017-03-17|archive-date=2019-03-30|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190330022720/https://inhabitat.com/world%E2%80%99s-largest-solar-kitchen-in-india-can-cook-upto-38500-meals-per-day/|url-status=dead}}</ref> kitchen is built in India. In association with government bodies, India is encouraging domestic biogas plants to support the kitchen system. | |||

| * of Nicolas Cahill's ''Household and City Organization at Olynthus'' (ISBN 0-300-08495-1), which has some information about the kitchens in ancient Greek times. | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| {{Portal|Cooking|Food}} | |||

| {{Commons category|Kitchens}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] and ]: ''The American Woman's Home'', 1869. | |||

| *] | |||

| * Cahill, Nicolas. ''Household and City Organization at Olynthus'' {{ISBN|0-300-08495-1}} | |||

| *] | |||

| * Cromley, Elizabeth Collins. ''The Food Axis: Cooking, Eating, and the Architecture of American Houses'' (University of Virginia Press; 2011); 288 pages; Explores the history of American houses through a focus on spaces for food preparation, cooking, consumption, and disposal. | |||

| * Harrison, M.: ''The Kitchen in History'', Osprey; 1972; {{ISBN|0-85045-068-3}} | |||

| * Kinchin, Juliet and Aidan O'Connor, Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen (MoMA: New York, 2011) | |||

| * Lupton, E. and Miller, J. A.: ''The Bathroom, the Kitchen, and the Aesthetics of Waste'', Princeton Architectural Press; 1996; {{ISBN|1-56898-096-5}}. | |||

| * Snodgrass, M. E.: ''Encyclopedia of Kitchen History''; Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers; (November 2004); {{ISBN|1-57958-380-6}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| *] | |||

| {{Commons category-inline|Kitchens}} | |||

| *] | |||

| {{Wikibooks|Kitchen Remodel}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{cuisine}} | |||

| *'']'' is also a novel by Japanese author ] (]) | |||

| {{Room}} | |||

| {{Meals navbox}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 09:33, 6 January 2025

Space primarily used for preparation and storage of food For other uses, see Kitchen (disambiguation).

A kitchen is a room or part of a room used for cooking and food preparation in a dwelling or in a commercial establishment. A modern middle-class residential kitchen is typically equipped with a stove, a sink with hot and cold running water, a refrigerator, and worktops and kitchen cabinets arranged according to a modular design. Many households have a microwave oven, a dishwasher, and other electric appliances. The main functions of a kitchen are to store, prepare and cook food (and to complete related tasks such as dishwashing). The room or area may also be used for dining (or small meals such as breakfast), entertaining and laundry. The design and construction of kitchens is a huge market all over the world.

Commercial kitchens are found in restaurants, cafeterias, hotels, hospitals, educational and workplace facilities, army barracks, and similar establishments. These kitchens are generally larger and equipped with bigger and more heavy-duty equipment than a residential kitchen. For example, a large restaurant may have a huge walk-in refrigerator and a large commercial dishwasher machine. In some instances, commercial kitchen equipment such as commercial sinks is used in household settings as it offers ease of use for food preparation and high durability.

In developed countries, commercial kitchens are generally subject to public health laws. They are inspected periodically by public-health officials, and forced to close if they do not meet hygienic requirements mandated by law.

History

Middle Ages

Early medieval European longhouses had an open fire under the highest point of the building. The "kitchen area" was between the entrance and the fireplace. In wealthy homes, there was typically more than one kitchen. In some homes, there were upwards of three kitchens. The kitchens were divided based on the types of food prepared in them.

The kitchen might be separate from the great hall due to the smoke from cooking fires and the chance the fires may get out of control. Few medieval kitchens survive as they were "notoriously ephemeral structures".

Colonial America

In Connecticut, as in other colonies of New England during Colonial America, kitchens were often built as separate rooms and were located behind the parlor and keeping room or dining room. One early record of a kitchen is found in the 1648 inventory of the estate of a John Porter of Windsor, Connecticut. The inventory lists goods in the house "over the kittchin" and "in the kittchin". The items listed in the kitchen were: silver spoons, pewter, brass, iron, arms, ammunition, hemp, flax and "other implements about the room".

Technological developments such as the Rumford roaster and the kitchen range enabled more efficient use of space and fuel.

Rationalization

A stepping stone to the modern fitted kitchen was the Frankfurt Kitchen, designed by Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky for social housing projects in 1926. This kitchen measured 1.9 by 3.4 metres (6 ft 3 in by 11 ft 2 in), and was built to optimize kitchen efficiency and lower building costs. The design was the result of detailed time-motion studies and interviews with future tenants to identify what they needed from their kitchens. Schütte-Lihotzky's fitted kitchen was built in some 10,000 apartments in housing projects erected in Frankfurt in the 1930s.

Materials

The Frankfurt Kitchen of 1926 was made of several materials depending on the application. The modern built-in kitchens of today use particle boards or MDF, decorated with a variety of materials and finishes including wood veneers, lacquer, glass, melamine, laminate, ceramic and eco gloss. Very few manufacturers produce home built-in kitchens from stainless steel. Until the 1950s, steel kitchens were used by architects, but this material was displaced by the cheaper particle board panels sometimes decorated with a steel surface.

Domestic kitchen planning

This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Domestic (or residential) kitchen design is a relatively recent discipline. The first ideas to optimize the work in the kitchen go back to Catharine Beecher's A Treatise on Domestic Economy (1843, revised and republished together with her sister Harriet Beecher Stowe as The American Woman's Home in 1869). Beecher's "model kitchen" propagated for the first time a systematic design based on early ergonomics. The design included regular shelves on the walls, ample workspace, and dedicated storage areas for various food items. Beecher even separated the functions of preparing food and cooking it altogether by moving the stove into a compartment adjacent to the kitchen.

Christine Frederick published from 1913 a series of articles on "New Household Management" in which she analyzed the kitchen following Taylorist principles of efficiency, presented detailed time-motion studies, and derived a kitchen design from them. Her ideas were taken up in the 1920s by architects in Germany and Austria, most notably Bruno Taut, Erna Meyer, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Benita Otte, who designed the first fitted kitchen for the Haus am Horn, which was completed in 1923. Similar design principles were employed by Schütte-Lihotzky for her famous Frankfurt kitchen, designed for Ernst May's Römerstadt, a social housing project in Frankfurt, in 1927.

While this "work kitchen" and variants derived from it were a great success for tenement buildings, homeowners had different demands and did not want to be constrained by a 6.4-square-metre (69 sq ft) kitchen. Nevertheless, the kitchen design was mostly ad-hoc following the whims of the architect. In the U.S., the "Small Homes Council", since 1993 the "Building Research Council", of the School of Architecture of the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign was founded in 1944 with the goal to improve the state of the art in home building, originally with an emphasis on standardization for cost reduction. It was there that the notion of the kitchen work triangle was formalized: the three main functions in a kitchen are storage, preparation, and cooking (which Catharine Beecher had already recognized), and the places for these functions should be arranged in the kitchen in such a way that work at one place does not interfere with work at another place, the distance between these places is not unnecessarily large, and no obstacles are in the way. A natural arrangement is a triangle, with the refrigerator, the sink, and the stove at a vertex each.

This observation led to a few common kitchen forms, commonly characterized by the arrangement of the kitchen cabinets and sink, stove, and refrigerator:

- A single-file kitchen (also known as a one-way galley or a straight-line kitchen) has all of these along one wall; the work triangle degenerates to a line. This is not optimal, but often the only solution if space is restricted. This may be common in an attic space that is being converted into a living space, or a studio apartment.

- The double-file kitchen (or two-way galley) has two rows of cabinets on opposite walls, one containing the stove and the sink, the other the refrigerator. This is the classical work kitchen and makes efficient use of space.

- In the L-kitchen, the cabinets occupy two adjacent walls. Again, the work triangle is preserved, and there may even be space for an additional table at a third wall, provided it does not intersect the triangle.

- A U-kitchen has cabinets along three walls, typically with the sink at the base of the "U". This is a typical work kitchen, too, unless the two other cabinet rows are short enough to place a table on the fourth wall.

- A G-kitchen has cabinets along three walls, like the U-kitchen, and also a partial fourth wall, often with a double basin sink at the corner of the G shape. The G-kitchen provides additional work and storage space and can support two work triangles. A modified version of the G-kitchen is the double-L, which splits the G into two L-shaped components, essentially adding a smaller L-shaped island or peninsula to the L-kitchen.

- The block kitchen (or island) is a more recent development, typically found in open kitchens. Here, the stove or both the stove and the sink are placed where an L or U kitchen would have a table, in a free-standing "island", separated from the other cabinets. In a closed room, this does not make much sense, but in an open kitchen, it makes the stove accessible from all sides such that two persons can cook together, and allows for contact with guests or the rest of the family since the cook does not face the wall any more. Additionally, the kitchen island's counter-top can function as an overflow surface for serving buffet-style meals or sitting down to eat breakfast and snacks.

In the 1980s, there was a backlash against industrial kitchen planning and cabinets with people installing a mix of work surfaces and free standing furniture, led by kitchen designer Johnny Grey and his concept of the "unfitted kitchen". Modern kitchens often have enough informal space to allow for people to eat in it without having to use the formal dining room. Such areas are called "breakfast areas", "breakfast nooks" or "breakfast bars" if space is integrated into a kitchen counter. Kitchens with enough space to eat in are sometimes called "eat-in kitchens". During the 2000s, flat pack kitchens were popular for people doing DIY renovating on a budget. The flat pack kitchens industry makes it easy to put together and mix and matching doors, bench tops and cabinets. In flat pack systems, many components can be interchanged.

In larger homes, where the owners might have meals prepared by a household staff member, the home may have a chef's kitchen. This typically differs from a normal domestic kitchen by having multiple ovens (possibly of different kinds for different kinds of cooking), multiple sinks, and warming drawers to keep food heated between cooking and service.

Other types

Restaurant and canteen kitchens found in hotels, hospitals, educational and workplace facilities, army barracks, and similar institutions are generally (in developed countries) subject to public health laws. They are inspected periodically by public health officials and forced to close if they do not meet hygienic requirements mandated by law.

Canteen kitchens (and castle kitchens) were often the places where new technology was used first. For instance, Benjamin Thompson's "energy saving stove", an early 19th-century fully closed iron stove using one fire to heat several pots, was designed for large kitchens; another thirty years passed before they were adapted for domestic use.

As of 2017, restaurant kitchens usually have tiled walls and floors and use stainless steel for other surfaces (workbench, but also door and drawer fronts) because these materials are durable and easy to clean. Professional kitchens are often equipped with gas stoves, as these allow cooks to regulate the heat more quickly and more finely than electrical stoves. Some special appliances are typical for professional kitchens, such as large installed deep fryers, steamers, or a bain-marie.

The fast food and convenience food trends have changed the manner in which restaurant kitchens operate. Some of these type restaurants may only "finish" convenience food that is delivered to them or just reheat completely prepared meals. At the most they may grill a hamburger or a steak. But in the early 21st century, c-stores (convenience stores) are attracting greater market share by performing more food preparation on-site and better customer service than some fast food outlets.

The kitchens in railway dining cars have presented special challenges: space is limited, and, personnel must be able to serve a great number of meals quickly. Especially in the early history of railways, this required flawless organization of processes; in modern times, the microwave oven and prepared meals have made this task much easier. Kitchens aboard ships, aircraft and sometimes railcars are often referred to as galleys. On yachts, galleys are often cramped, with one or two burners fueled by an LP gas bottle. Kitchens on cruise ships or large warships, by contrast, are comparable in every respect with restaurants or canteen kitchens.

On passenger airliners, the kitchen is reduced to a pantry. The crew's role is to heat and serve in-flight meals delivered by a catering company. An extreme form of the kitchen occurs in space, e.g., aboard a Space Shuttle (where it is also called the "galley") or the International Space Station. The astronauts' food is generally completely prepared, dehydrated, and sealed in plastic pouches before the flight. The kitchen is reduced to a rehydration and heating module.

Outdoor areas where food is prepared are generally not considered kitchens, even though an outdoor area set up for regular food preparation, for instance when camping, might be referred to as an "outdoor kitchen". An outdoor kitchen at a campsite might be placed near a well, water pump, or water tap, and it might provide tables for food preparation and cooking (using portable camp stoves). Some campsite kitchen areas have a large tank of propane connected to burners so that campers can cook their meals. Military camps and similar temporary settlements of nomads may have dedicated kitchen tents, which have a vent to enable cooking smoke to escape.

In schools where home economics, food technology (previously known as "domestic science"), or culinary arts are taught, there are typically a series of kitchens with multiple equipment (similar in some respects to laboratories) solely for the purpose of teaching. These consist of multiple workstations, each with its own oven, sink, and kitchen utensils, where the teacher can show students how to prepare food and cook it.

By region

China

Kitchens in China are called chúfáng(厨房). More than 3000 years ago, the ancient Chinese used the ding for cooking food. The ding was developed into the wok and pot used today. In Chinese spiritual tradition, a Kitchen God watches over the kitchen for the family and reports to the Jade Emperor annually about the family's behavior. On Chinese New Year's Eve, families would gather to pray for the kitchen god to give a good report to heaven and wish him to bring back good news on the fifth day of the New Year.

The most common cooking equipment in Chinese family kitchens and restaurant kitchens are woks, steamer baskets and pots. The fuel or heating resource was also an important technique to practice the cooking skills. Traditionally Chinese were using wood or straw as the fuel to cook food. A Chinese chef had to master flaming and heat radiation to reliably prepare traditional recipes. Chinese cooking will use a pot or wok for pan-frying, stir-frying, deep frying or boiling.

Japan

Main article: Japanese kitchen

Kitchens in Japan are called Daidokoro (台所; lit. "kitchen"). Daidokoro is the place where food is prepared in a Japanese house. Until the Meiji era, a kitchen was also called kamado (かまど; lit. stove) and there are many sayings in the Japanese language that involve kamado as it was considered the symbol of a house and the term could even be used to mean "family" or "household" (similar to the English word "hearth"). When separating a family, it was called Kamado wo wakeru, which means "divide the stove". Kamado wo yaburu (lit. "break the stove") means that the family was bankrupt.

India

In India, a kitchen is called a "Rasoi" (in Hindi\Sanskrit) or a "Swayampak ghar" in Marathi, and there exist many other names for it in the various regional languages. Many different methods of cooking exist across the country, and the structure and the materials used in constructing kitchens have varied depending on the region. For example, in the north and central India, cooking used to be carried out in clay ovens called "chulha" (also chullha or chullah), fired by wood, coal or dried cow dung. In households where members observed vegetarianism, separate kitchens were maintained to cook and store vegetarian and non-vegetarian food. Religious families often treat the kitchen as a sacred space. Indian kitchens are built on an Indian architectural science called vastushastra. The Indian kitchen vastu is of utmost importance while designing kitchens in India. Modern-day architects also follow the norms of vastushastra while designing Indian kitchens across the world.

While many kitchens belonging to poor families continue to use clay stoves and the older forms of fuel, the urban middle and upper classes usually have gas stoves with cylinders or piped gas attached. Electric cooktops are rarer since they consume a great deal of electricity, but microwave ovens are gaining popularity in urban households and commercial enterprises. Indian kitchens are also supported by biogas and solar energy as fuel. World's largest solar energy kitchen is built in India. In association with government bodies, India is encouraging domestic biogas plants to support the kitchen system.

See also

- Cooking techniques

- Cuisine

- Dirty kitchen

- Hearth

- Hoosier cabinet

- Kitchen utensil

- Kitchen ventilation

- Universal design

References

- "The Pros and Cons of Using A Commercial Sink at Home – Home Decor Expert and". Home Decor Expert. 2018-06-14. Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- Vogel, Carol (1982-12-09). "The commercial kitchen at home: pros and cons". The New York Times.

- "What Should Be Done Following Health Violations From an Inspection?". www.fooddocs.com. Retrieved 2024-07-22.

- Thompson, Theodor (1992) Medieval Homes, Sampson Lowel House

- Christie, Neil; Creighton, Oliver; Edgeworth, Matt; Hamerow, Helena (2013), Transforming Townscapes: From burgh to borough: the archaeology of Wallingford, AD 800–1400, The Society for Medieval Archaeology Monograph Series, Oxford: Society for Medieval Archaeology, p. 201, ISBN 978-1-909662-09-4

- Creighton, Oliver; Christie, Neil (2015), "The Archaeology of Wallingford Castle: a summary of the current state of knowledge", in Keats-Rohan, K. S. B.; Christie, Neil; Roffe, David (eds.), Wallingford: The Castle and the Town in Context, BAR British Series, Oxford: Archaeopress, p. 13, ISBN 978-1-4073-1418-1

- Trumbull, J. Hammond (1850). The Public Records of the Colony of Connecticut 1636–1776. Vol. 1. Hartford, Brown & Parsons. p. 476.

- Rawsthorn, Alice (2010-09-27) Modernist triumph in the kitchen. New York Times

- Moore, Rowan (2019-01-21). "Bauhaus at 100: its legacy in five key designs". The Guardian. Retrieved 2019-01-21.

- Blank, Christine (9 January 2014). "C-Stores Eating Your Lunch". QSR Magazine.

- "World's Largest 38500-meal Solar Kitchen in India". Archived from the original on 2019-03-30. Retrieved 2017-03-17.

Further reading

- Beecher, C. E. and Beecher Stowe, H.: The American Woman's Home, 1869. The American Woman's Home

- Cahill, Nicolas. Household and City Organization at Olynthus ISBN 0-300-08495-1

- Cromley, Elizabeth Collins. The Food Axis: Cooking, Eating, and the Architecture of American Houses (University of Virginia Press; 2011); 288 pages; Explores the history of American houses through a focus on spaces for food preparation, cooking, consumption, and disposal.

- Harrison, M.: The Kitchen in History, Osprey; 1972; ISBN 0-85045-068-3

- Kinchin, Juliet and Aidan O'Connor, Counter Space: Design and the Modern Kitchen (MoMA: New York, 2011)

- Lupton, E. and Miller, J. A.: The Bathroom, the Kitchen, and the Aesthetics of Waste, Princeton Architectural Press; 1996; ISBN 1-56898-096-5. The Bathroom, the Kitchen and the Aesthetics of Waste

- Snodgrass, M. E.: Encyclopedia of Kitchen History; Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers; (November 2004); ISBN 1-57958-380-6

External links

![]() Media related to Kitchens at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Kitchens at Wikimedia Commons

| Rooms and spaces of a house | |

|---|---|

| Shared rooms | |

| Private rooms | |

| Spaces | |

| Technical, utility and storage |

|

| Great house areas | |

| Other | |

| Architectural elements | |

| Related | |

| Meals | |

|---|---|

| Common meals | |

| Components and courses | |

| Table service | |

| Presentation | |

| Dining | |

| Regional styles | |

| Packed | |

| Menus and meal deals | |

| Communal meals | |

| Catering and food delivery | |

| Places to eat | |

| Related | |