| Revision as of 09:05, 4 November 2005 editPhyschim62 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers33,631 edits →Safety: flammability← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 06:05, 16 January 2025 edit undoCitation bot (talk | contribs)Bots5,450,381 edits Added bibcode. | Use this bot. Report bugs. | Suggested by Spinixster | Category:Household chemicals | #UCB_Category 6/74 | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Colorless and faint organic acid found in vinegar}} | |||

| <!-- Here is a table of data; skip past it to edit the text. --> | |||

| {{Redirect-distinguish|Acetic|Asceticism{{!}}Ascetic}} | |||

| {| align="right" border="1" cellspacing="0" cellpadding="3" style="margin: 0 0 0 0.5em; background: #FFFFFF; border-collapse: collapse; border-color: #C0C090;" | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | {{PAGENAME}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2019}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=September 2016}} | |||

| | align="center" colspan="2" | ] | |||

| {{cs1 config |name-list-style=vanc |display-authors=6}} | |||

| |- | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | General | |||

| {{Chembox | |||

| |- | |||

| | Verifiedfields = changed | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Watchedfields = changed | |||

| | Acetic acid<br/>Ethanoic acid | |||

| | verifiedrevid = 477238786 | |||

| |- | |||

| | |

| Name = | ||

| | ImageFile = | |||

| | Methanecarboxylic acid<br/>Acetyl hydroxide (AcOH)<br/>Hydrogen acetate (HAc) | |||

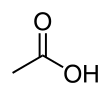

| | ImageFileL1 = Acetic-acid-2D-skeletal.svg | |||

| |- | |||

| | ImageFileL1_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ImageClassL1 = skin-invert | |||

| | C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>O<sub>2</sub> | |||

| | ImageNameL1 = Skeletal formula of acetic acid | |||

| |- | |||

| | ImageFileR1 = Acetic-acid-CRC-GED-3D-vdW-B.png | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ImageFileR1_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} | |||

| | CC(=O)O | |||

| | ImageNameR1 = Spacefill model of acetic acid | |||

| |- | |||

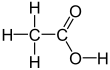

| | ImageFileL2 = Essigsäure - Acetic acid.svg | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ImageFileL2_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} | |||

| | 60.05 g/mol | |||

| | ImageClassL2 = skin-invert | |||

| |- | |||

| | ImageNameL2 = Skeletal formula of acetic acid with all explicit hydrogens added | |||

| | Appearance | |||

| | ImageFileR2 = Acetic-acid-CRC-GED-3D-balls-B.png | |||

| | Colourless crystals<br/>or viscous liquid | |||

| | ImageFileR2_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ImageNameR2 = Ball and stick model of acetic acid | |||

| | ] | |||

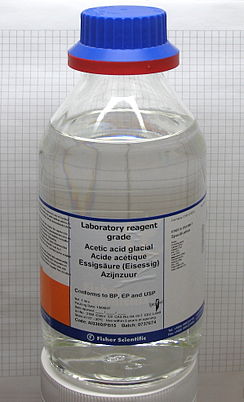

| | ImageFile3 = Acetic acid.jpg | |||

| | <nowiki></nowiki> | |||

| | ImageFile3_Ref = {{chemboximage|correct|??}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | ImageSize3 = 244 | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | Properties | |||

| | ImageName3 = Sample of acetic acid in a reagent bottle | |||

| |- | |||

| | PIN = Acetic acid<ref name=iupac2013>{{cite book | title = Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book) | publisher = The ] | date = 2014 | location = Cambridge | page = 745 | doi = 10.1039/9781849733069-00648 | isbn = 978-0-85404-182-4}}</ref> | |||

| | ] and ] | |||

| | SystematicName = Ethanoic acid | |||

| | 1.049 g/cm<sup>3</sup>, liquid<br/> 1.266 g/cm<sup>3</sup>, solid | |||

| | OtherNames = Vinegar (when dilute); Hydrogen acetate; Methanecarboxylic acid; Ethylic acid<ref>{{cite book |title=Scientific literature reviews on generally recognised as safe (GRAS) food ingredients |publisher=National Technical Information Service |year=1974 |page=1}}</ref><ref>"Chemistry", volume 5, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1961, page 374.</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | IUPACName = | |||

| | ] in ] | |||

| | Section1 = {{Chembox Identifiers | |||

| | Fully miscible | |||

| | Abbreviations = AcOH | |||

| |- | |||

| | CASNo = 64-19-7 | |||

| | In ],]<br/> In ], ]<br/> In ] | |||

| | CASNo_Ref = {{cascite|correct|CAS}} | |||

| | Fully miscible<br/> Fully miscible<br/> Pract. insoluble | |||

| | PubChem = 176 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ChemSpiderID = 171 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ChemSpiderID_Ref = {{chemspidercite|correct|chemspider}} | |||

| | 16.7°C (289.6 K) | |||

| | UNII = Q40Q9N063P | |||

| |- | |||

| | UNII_Ref = {{fdacite|correct|FDA}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | EINECS = 200-580-7 | |||

| | 118.1°C (391.2 K) | |||

| | UNNumber = 2789 | |||

| |- | |||

| | DrugBank_Ref = {{drugbankcite|correct|drugbank}} | |||

| | ] (p''K''<sub>a</sub>) | |||

| | DrugBank = DB03166 | |||

| | 4.76 | |||

| | KEGG = C00033 | |||

| |- | |||

| | KEGG1 = D00010 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | KEGG1_Ref = {{keggcite|correct|kegg}} | |||

| | 1.22 c] at 25°C | |||

| | MeSHName = Acetic+acid | |||

| |- | |||

| | ChEBI_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ChEBI = 15366 | |||

| | 1.74 ] (gas) | |||

| | ChEMBL = 539 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ChEMBL_Ref = {{ebicite|correct|EBI}} | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | Hazards <!-- Summary only- MSDS entry provides more complete information --> | |||

| | IUPHAR_ligand = 1058 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Beilstein = 506007 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Gmelin = 1380 | |||

| | | ] | |||

| | 3DMet = B00009 | |||

| |- | |||

| | RTECS = AF1225000 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | SMILES = CC(O)=O | |||

| | Corrosive ('''C''') | |||

| | StdInChI = 1S/C2H4O2/c1-2(3)4/h1H3,(H,3,4) | |||

| |- | |||

| | StdInChI_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | StdInChIKey = QTBSBXVTEAMEQO-UHFFFAOYSA-N | |||

| | {{nfpa|2|2|0}} | |||

| | StdInChIKey_Ref = {{stdinchicite|correct|chemspider}} | |||

| |- | |||

| }} | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Section2 = {{Chembox Properties | |||

| | 43 °C | |||

| | Formula = {{chem2|CH3COOH}} | |||

| |- | |||

| | C=2|H=4|O=2 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Appearance = Colourless liquid | |||

| | {{R10}}, {{R35}} | |||

| | Odor = Heavily vinegar-like | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Density = 1.049 g/cm<sup>3</sup> (liquid); 1.27 g/cm<sup>3</sup> (solid) | |||

| | {{S1/2}}, {{S23}}, {{S26}}, {{S45}} | |||

| | Solubility = ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | MeltingPtK = 289 to 290 | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | ] | |||

| | BoilingPtK = 391 to 392 | |||

| |- | |||

| | pKa = 4.756 | |||

| | ] | |||

| | ConjugateBase = ] | |||

| | ], ], etc. | |||

| | Viscosity = 1.22 mPa s <br /> 1.22 cP | |||

| |- | |||

| | RefractIndex = 1.371 (V<sub>D</sub> = 18.19) | |||

| | ] | |||

| | Dipole = 1.74 D | |||

| | Phase behaviour<br>Solid, liquid, gas | |||

| | MagSus = −31.54·10<sup>−6</sup> cm<sup>3</sup>/mol | |||

| |- | |||

| | LogP = −0.28<ref name="chemsrc">{{cite web |url=https://www.chemsrc.com/en/cas/64-19-7_162032.html |title=acetic acid_msds}}</ref> | |||

| | ] | |||

| | VaporPressure = 1.54653947{{nbsp}}kPa (20 °C) <br /> 11.6{{nbsp}}mmHg (20 °C)<ref name="lange">''Lange's Handbook of Chemistry'', 10th ed.</ref> | |||

| | ], ], ], ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |- | |||

| | Section3 = | |||

| ! {{chembox header}} | Related compounds | |||

| | Section4 = | |||

| |- | |||

| | Section5 = {{Chembox Thermochemistry | |||

| | Related ] | |||

| | DeltaHf = −483.88–483.16 kJ/mol | |||

| | ]<br/>]<br/> ] | |||

| | DeltaHc = −875.50–874.82 kJ/mol | |||

| |- | |||

| | Entropy = 158.0 J/(K⋅mol) | |||

| | Related compounds | |||

| | HeatCapacity = 123.1 J/(K⋅mol) | |||

| | ]<br/> ]<br/> ]<br/> ]<br/>]<br/> ] <br/>] | |||

| }} | |||

| |- | |||

| | Section6 = {{Chembox Pharmacology | |||

| | {{chembox header}} | <small>Except where noted otherwise, data are given for<br> materials in their ]<br/>]</small> | |||

| | Pharmacology_ref = | |||

| |- | |||

| | ATCCode_prefix = G01 | |||

| |} | |||

| | ATCCode_suffix = AD02 | |||

| '''Acetic acid''', also known as '''ethanoic acid''', is the ] ] that gives ] its sour taste and pungent smell. Pure water-free acetic acid is a colourless ] liquid that freezes below 16.7 °C to a colourless crystalline solid. Acetic ] is corrosive and its vapour is irritating to eyes and nose, although it is a rather ] based on its ability to dissociate in ] ]s. | |||

| | ATC_Supplemental = {{ATC|S02|AA10}} | |||

| | ATCvet = | |||

| | Licence_EU = | |||

| | INN = | |||

| | INN_EMA = | |||

| | Licence_US = | |||

| | Legal_status = | |||

| | Legal_AU = S2 | |||

| | Legal_AU_comment = and S6 | |||

| | Legal_CA = | |||

| | Legal_CA_comment = | |||

| | Legal_NZ = | |||

| | Legal_NZ_comment = | |||

| | Legal_UK = | |||

| | Legal_UK_comment = | |||

| | Legal_US = | |||

| | Legal_US_comment = | |||

| | Legal_EU = | |||

| | Legal_EU_comment = | |||

| | Legal_UN = | |||

| | Legal_UN_comment = | |||

| | Pregnancy_category = | |||

| | Pregnancy_AU = | |||

| | Pregnancy_AU_comment = | |||

| | Dependence_liability = | |||

| | AdminRoutes = | |||

| | Bioavail = | |||

| | ProteinBound = | |||

| | Metabolism = | |||

| | Metabolites = | |||

| | OnsetOfAction = | |||

| | HalfLife = | |||

| | DurationOfAction = | |||

| | Excretion = | |||

| }} | |||

| | Section7 = {{Chembox Hazards | |||

| | GHSPictograms = {{GHS02}} {{GHS05}} | |||

| | GHSSignalWord = Danger | |||

| | HPhrases = {{H-phrases|226|314}} | |||

| | PPhrases = {{P-phrases|280|305+351+338|310}} | |||

| | NFPA-F = 2 | |||

| | NFPA-H = 3 | |||

| | NFPA-R = 0 | |||

| | FlashPtC = 40 | |||

| | AutoignitionPtC = 427 | |||

| | LD50 = 3.31 g/kg, oral (rat) | |||

| | LC50 = 5620 ppm (mouse, 1 ])<br />16000 ppm (rat, 4 h)<ref>{{IDLH|64197|Acetic acid}}</ref> | |||

| | ExploLimits = 4–16% | |||

| | PEL = TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m<sup>3</sup>)<ref name=PGCH>{{PGCH|0002}}</ref> | |||

| | REL = TWA 10 ppm (25 mg/m<sup>3</sup>) ST 15 ppm (37 mg/m<sup>3</sup>)<ref name=PGCH /> | |||

| | IDLH = 50 ppm<ref name=PGCH /> | |||

| }} | |||

| | Section8 = {{Chembox Related | |||

| | OtherFunction_label = ]s | |||

| | OtherFunction = ]<br />] | |||

| | OtherCompounds = ]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Infobox drug | |||

| | container_only = yes | |||

| | Drugs.com = {{drugs.com|monograph|acetic-acid}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Acetic acid''' {{IPAc-en|ə|ˈ|s|iː|t|ᵻ|k}}, systematically named '''ethanoic acid''' {{IPAc-en|ˌ|ɛ|θ|ə|ˈ|n|oʊ|ᵻ|k}}, is an acidic, colourless liquid and ] with the ] {{chem2|CH3COOH}} (also written as {{chem2|CH3CO2H}}, {{chem2|C2H4O2}}, or {{chem2|HC2H3O2}}). ] is at least 4% acetic acid by volume, making acetic acid the main component of vinegar apart from water. It has been used, as a component of vinegar, throughout history from at least the third century BC. | |||

| Acetic acid is |

Acetic acid is the second simplest ] (after ]). It is an important ] and industrial chemical across various fields, used primarily in the production of ] for ], ] for wood ], and synthetic fibres and fabrics. In households, diluted acetic acid is often used in ]s. In the ], acetic acid is controlled by the ] E260 as an ] and as a condiment. In ], the ], derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. When bound to ], it is central to the ] of ]s and ]s. | ||

| The global demand for acetic acid as of 2023 is about 17.88 million ] per year (t/a). Most of the world's acetic acid is produced via the ] of ]. Its production and subsequent industrial use poses health hazards to workers, including incidental skin damage and chronic respiratory injuries from inhalation. | |||

| The global demand of acetic acid is around 6.5 million ]s per year (Mt/a), of which approximately 1.5 Mt/a is met by recycling; the remainder is manufactured from ] feedstocks (see ] below). | |||

| == Nomenclature == | == Nomenclature == | ||

| The trivial name |

The ] "acetic acid" is the most commonly used and ]. The systematic name "ethanoic acid", a valid ] name, is constructed according to the substitutive nomenclature.<ref name="BB-prs310305">IUPAC Provisional Recommendations 2004 </ref> The name "acetic acid" derives from the ] word for ], "{{wikt-lang|la|acetum}}", which is related to the word "]" itself. | ||

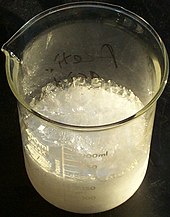

| "Glacial acetic acid" is a name for water-free (]) acetic acid. Similar to the ] name "Eisessig" ("ice vinegar"), the name comes from the solid ice-like crystals that form with agitation, slightly below room temperature at {{convert|16.6|C|F}}. Acetic acid can never be truly water-free in an atmosphere that contains water, so the presence of 0.1% water in glacial acetic acid lowers its melting point by 0.2 °C.<ref name="Purification of Laboratory Chemicals">{{cite book| vauthors = Armarego WL, Chai C |title=Purification of Laboratory Chemicals | edition = 6th |publisher=Butterworth-Heinemann|year=2009|isbn=978-1-85617-567-8}}</ref> | |||

| A common ] for acetic acid is AcOH (or HOAc), where Ac is the ] representing the ] ] {{chem2|CH3\sC(\dO)\s}}; the ], ] ({{chem2|CH3COO−}}), is thus represented as {{chem2|AcO−}}.<ref name="Cooper">{{cite book| vauthors = Cooper C |title=Organic Chemist's Desk Reference|edition=2nd |date=9 August 2010|publisher=CRC Press|isbn=978-1-4398-1166-5|pages=102–104}}</ref> Acetate is the ] resulting from loss of {{chem2|]}} from acetic acid. The name "acetate" can also refer to a ] containing this anion, or an ] of acetic acid.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Hendrickson JB, Cram DJ, Hammond GS |title=Organic Chemistry|edition=3rd|year=1970|publisher=McGraw Hill Kogakusha|location=Tokyo|page=135}}</ref> (The symbol Ac for the acetyl functional group is not to be confused with the symbol Ac for the element ]; context prevents confusion among organic chemists). To better reflect its structure, acetic acid is often written as {{chem2|CH3\sC(O)OH}}, {{chem2|CH3\sC(\dO)\sOH}}, {{chem2|CH3COOH}}, and {{chem2|CH3CO2H}}. In the context of ]s, the abbreviation HAc is sometimes used,<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = DeSousa LR |title=Common Medical Abbreviations|year=1995|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-0-8273-6643-5|page=|url=https://archive.org/details/commonmedicalabb0000unse/page/97}}</ref> where Ac in this case is a symbol for acetate (rather than acetyl). | |||

| The most common and official abbreviation for acetic acid is '''AcOH''' or '''HOAc''' where ''Ac'' stands for the ] ] CH<sub>3</sub>-C(=O)-. In the context of ]s the abbreviation '''HAc''' is often used where ''Ac'' instead stands for the ] ], although this use is regarded by many as misleading. In either case, the ''Ac'' is not to be confused with the abbreviation for the ] ]. | |||

| The carboxymethyl functional group derived from removing one hydrogen from the ] group of acetic acid has the ] {{chem2|\sCH2\sC(\dO)\sOH}}. | |||

| Acetic acid has the ] '''C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>O<sub>2</sub>''' but is often written as '''CH<sub>3</sub>-COOH''', '''CH<sub>3</sub>COOH''', or '''CH<sub>3</sub>CO<sub>2</sub>H''' to better reflect its structure. The ] resulting from loss of H<sup>+</sup> from acetic acid is the ''']''' ion (CH<sub>3</sub>COO<sup>-</sup>). The word acetate can also refer to a ] with this anion or an ] of acetic acid. | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| ] was known early in civilization as the natural result of exposure of ] and ] to air because acetic acid-producing bacteria are present globally. The use of acetic acid in ] extends into the third century BC, when the Greek philosopher ] described how vinegar acted on metals to produce ]s useful in art, including ''white lead'' (]) and '']'', a green mixture of ] salts including ]. Ancient ] boiled soured wine to produce a highly sweet syrup called ''sapa''. ] that was produced in lead pots was rich in ], a sweet substance also called ''sugar of lead'' or ''sugar of ]'', which contributed to ] among the Roman aristocracy.<ref name="martin">{{cite book | vauthors = Martin G |url=https://archive.org/details/dli.bengal.10689.10857 |title=Industrial and Manufacturing Chemistry |publisher=Crosby Lockwood |year=1917 |edition=Part 1, Organic |location=London |pages=–331}}</ref> | |||

| In the 16th-century ] alchemist ] described the production of ] from the ] of lead acetate, ]. The presence of water in vinegar has such a profound effect on acetic acid's properties that for centuries chemists believed that glacial acetic acid and the acid found in vinegar were two different substances. French chemist ] proved them identical.<ref name="martin" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Adet PA |year=1798 |title=Mémoire sur l'acide acétique | trans-title = Memoir on acetic acid | language = French |journal=Annales de Chimie |volume=27 |pages=299–319}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1845 German chemist ] ] acetic acid from ]s for the first time. This reaction sequence consisted of ] of ] to ], followed by ] to ] and aqueous chlorination to ], and concluded with ] ] to acetic acid.<ref name="goldwhite">{{cite journal | vauthors = Goldwhite H |date=September 2003 |title=This month in chemical history |url=http://membership.acs.org/N/NewHaven/bulletins/Bulletin_2003-09.pdf |url-status=dead |journal=New Haven Section Bulletin American Chemical Society |volume=20 |issue=3 |page=4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090304210839/http://membership.acs.org/N/NewHaven/bulletins/Bulletin_2003-09.pdf |archive-date=4 March 2009}}</ref> | |||

| By 1910, most glacial acetic acid was obtained from the ], a product of the distillation of wood. The acetic acid was isolated by treatment with ], and the resulting ] was then acidified with ] to recover acetic acid. At that time, Germany was producing 10,000 ]s of glacial acetic acid, around 30% of which was used for the manufacture of ].<ref name="martin" /><ref name="schweppe">{{cite journal | vauthors = Schweppe H |year=1979 |title=Identification of dyes on old textiles |url=http://aic.stanford.edu/jaic/articles/jaic19-01-003_1.html |url-status=dead |journal=Journal of the American Institute for Conservation |volume=19 |issue=1/3 |pages=14–23 |doi=10.2307/3179569 |jstor=3179569 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090529021302/http://aic.stanford.edu/jaic/articles/jaic19-01-003_1.html |archive-date=29 May 2009 |access-date=12 October 2005}}</ref> | |||

| ] is as old as civilisation itself, if not older. Acetic acid-producing bacteria are universally present, and any culture practicing the ] of ] or ] inevitably discovered vinegar as the natural result of these alcoholic beverages being exposed to air. | |||

| Because both ] and ] are commodity raw materials, methanol carbonylation long appeared to be attractive precursors to acetic acid. ] at ] developed a methanol carbonylation pilot plant as early as 1925.<ref name="wagner">{{cite book | vauthors = Wagner FS |title=Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology |publisher=] |year=1978 | veditors = Grayson M |edition=3rd |location=New York |chapter=Acetic acid}}</ref> However, a lack of practical materials that could contain the corrosive reaction mixture at the high ]s needed (200 ] or more) discouraged commercialization of these routes. The first commercial methanol carbonylation process, which used a ] catalyst, was developed by German chemical company ] in 1963. In 1968, a ]-based catalyst (''cis''−{{chem2|−}}) was discovered that could operate efficiently at lower pressure with almost no by-products. US chemical company ] built the first plant using this catalyst in 1970, and rhodium-catalyzed methanol carbonylation became the dominant method of acetic acid production (see ]). In the late 1990s, ] Chemicals commercialised the Cativa catalyst ({{chem2|−}}), which is promoted by ] for greater efficiency.<ref>, Harold A. Wittcoff, Bryan G. Reuben, Jeffery S. Plotkin</ref> Known as the ], the ]-catalyzed production of glacial acetic acid is ], and has largely supplanted the Monsanto process, often in the same production plants.<ref name="lancaster">{{cite book | vauthors = Lancaster M |url= https://archive.org/details/greenchemistryin00lanc/page/262 |title=Green Chemistry, an Introductory Text |publisher=Royal Society of Chemistry |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-85404-620-1 |location=Cambridge |pages= |url-access=registration}}</ref> | |||

| The use of acetic acid in chemistry extends into antiquity. In the ], the ] philosopher ] described how vinegar acted on metals to produce ]s useful in art, including ''white lead'' (]) and '']'', a green mixture of ] salts including ]. Ancient ] boiled soured wine in lead pots to produce a highly sweet syrup called ''sapa''. Sapa was rich in ], a sweet substance also called ''sugar of lead'' or ''sugar of ]'', which contributed to ] among the Roman aristocracy. The ] Persian alchemist ] concentrated acetic acid from vinegar through ]. | |||

| === Interstellar medium === | |||

| In the ], glacial acetic acid was prepared through the ] of metal acetates. The ] ] alchemist ] described such a procedure, and he compared the glacial acetic acid produced by this means to vinegar. The presence of water in vinegar has such a profound effect on acetic acid's properties that for centuries many chemists believed that glacial acetic acid and the acid found in vinegar were two different substances. The French chemist ] proved them to be identical. | |||

| ] acetic acid was discovered in 1996 by a team led by David Mehringer<ref name="Meh">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mehringer DM, Snyder LE, Miao Y, Lovas FJ |year=1997 |title=Detection and Confirmation of Interstellar Acetic Acid |journal=Astrophysical Journal Letters |volume=480 |issue=1 |page=L71 |bibcode=1997ApJ...480L..71M |doi=10.1086/310612 |doi-access=free}}</ref> using the former ] array at the ] and the former ] located at the ]. It was first detected in the ] North molecular cloud (also known as the Sgr B2 ] source). Acetic acid has the distinction of being the first molecule discovered in the interstellar medium using solely ]; in all previous ISM molecular discoveries made in the millimetre and centimetre wavelength regimes, single dish radio telescopes were at least partly responsible for the detections.<ref name="Meh" /> | |||

| == Properties == | |||

| In ] the German chemist ] ] acetic acid from ] materials for the first time. This reaction sequence consisted of ] of ] to ], followed by ] to ] and aqueous chlorination to ], and was concluded with ] by ] to acetic acid.{{ref|Kolbe}} | |||

| ] | |||

| By ] most glacial acetic acid was obtained from the "pyroligneous liquor" from distillation of wood. The acetic acid was isolated from this by treatment with ], and the resultant ] was then acidified with ] to recover acetic acid. At this time Germany was producing 10,000 ]s of glacial acetic acid, around 30% of which was used for the manufacture of ].{{Ref|Martin}}{{Ref|Schweppe}} | |||

| <br style="clear:both;"/> | |||

| == Chemical properties == | |||

| :''See also: ].'' | |||

| ]] | |||

| === Acidity === | === Acidity === | ||

| The hydrogen centre in the ] (−COOH) in carboxylic acids such as acetic acid can separate from the molecule by ionization: | |||

| The hydrogen (H) atom in the ] (-COOH) in carboxylic acids such as acetic acid can be given off as an H<sup>+</sup> ion (]), giving them their ] character. Acetic acid is a weak, effectively ] in aqueous solution, with a ] value of 4.8. A 1.0 ] solution (about the concentration of domestic vinegar) has a pH of 2.4, indicating that merely 0.4% of the acetic acid molecules are dissociated. | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3COOH ⇌ CH3CO2− + H+}} | |||

| Because of this release of the ] ({{chem2|H+}}), acetic acid has acidic character. Acetic acid is a weak ]. In aqueous solution, it has a ] value of 4.76.<ref name="Goldmine">{{cite journal |title=Thermodynamic Quantities for the Ionization Reactions of Buffers | vauthors = Goldberg R, Kishore N, Lennen R |journal=Journal of Physical and Chemical Reference Data |volume=31 |issue=2|pages=231–370 |year=2002 |url=https://www.nist.gov/data/PDFfiles/jpcrd615.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081006062140/https://www.nist.gov/data/PDFfiles/jpcrd615.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=6 October 2008 |doi=10.1063/1.1416902|bibcode = 2002JPCRD..31..231G}}</ref> Its ] is ] ({{chem2|CH3COO−}}). A 1.0 ] solution (about the concentration of domestic vinegar) has a ] of 2.4, indicating that merely 0.4% of the acetic acid molecules are dissociated.{{efn|1= = 10<sup>−2.4</sup> = 0.4%}} | |||

| ] | |||

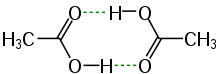

| === Cyclic dimer === | |||

| ] | |||

| The crystal structure of acetic acid{{ref|Jones&Templeton}} shows that the molecules pair up into ]s connected by ]s (see image). The dimers can also be detected in the vapour at 120 °C. They probably also occur in the liquid phase of pure acetic acid, but are rapidly disrupted if any water is present. This dimerisation behaviour is shared by other lower carboxylic acids. | |||

| === Solvent === | |||

| ] acetic acid is a ] (]) ], similar to ] and ]. With a moderate ] of 6.2, it can dissolve not only polar compounds such as inorganic salts and ]s, but also non-polar compounds such as oils and ]s such as ] and ]. It readily mixes with many other polar and non-polar ]s such as ], ], and ]. This ] and ] of acetic acid makes it an outstanding industrial chemical. | |||

| === ]s === | |||

| : ''More reactions involving acetic acid are discussed below.'' | |||

| Acetic acid is corrosive to many ]s including ], ], and ], forming ] gas and metal salts called ]s. | |||

| ] is relatively resistant so that aluminium tanks can be used to transport acetic acid. Metal acetates can also be prepared from acetic acid and an appropriate ], as in the popular "] + vinegar" reaction. With the notable exception of ], almost all acetates are soluble in water. | |||

| :](]) + 2 CH<sub>3</sub>COOH(]) → (CH<sub>3</sub>COO)<sub>2</sub>Mg(aq) + ](]) | |||

| :](s) + CH<sub>3</sub>COOH(aq) → ](aq) + ](g) + ](]) | |||

| ] | |||

| Acetic acid undergoes the typical reactions of a ], notably the formation of ] by reduction, and formation of derivatives such as ] via ]. Other substitution derivatives include ]; this ] is produced by ] from two molecules of acetic acid. ]s of acetic acid can likewise be formed via ], and ]s can also be formed. See ] below for the industrial application of some of these reactions. | |||

| When heated above 440 °C, acetic acid decomposes to produce ] and ], or to produce ] and water. | |||

| === Detection === | |||

| ] | |||

| Acetic acid can be detected by its characteristic smell. A ] for salts of acetic acid is ] solution which results in a deeply red colour that disappears after acidification. Acetates when heated with ] form ] which can be detected by its extremely disgusting ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| <br style="clear:both;"/> | |||

| == |

=== Structure === | ||

| In solid acetic acid, the molecules form chains of individual molecules interconnected by ]s.<ref name="jones">{{cite journal| vauthors = Jones RE, Templeton DH |year = 1958|title = The crystal structure of acetic acid|journal = Acta Crystallographica|volume = 11|issue = 7|pages=484–487|doi = 10.1107/S0365110X58001341|hdl = 2027/mdp.39015077597907 |url = https://cloudfront.escholarship.org/dist/prd/content/qt3x45b5nd/qt3x45b5nd.pdf|doi-access = free|bibcode = 1958AcCry..11..484J }}</ref> In the vapour phase at {{convert|120|C|F}}, ] can be detected. Dimers also occur in the liquid phase in dilute solutions with non-hydrogen-bonding solvents, and to a certain extent in pure acetic acid,<ref name="briggs">{{cite journal| vauthors = Briggs JM, Nguyen TB, Jorgensen WL |title = Monte Carlo simulations of liquid acetic acid and methyl acetate with the OPLS potential functions|journal = Journal of Physical Chemistry|year = 1991|volume = 95|pages=3315–3322|doi = 10.1021/j100161a065|issue = 8}}</ref> but are disrupted by hydrogen-bonding solvents. The dissociation ] of the dimer is estimated at 65.0–66.0 kJ/mol, and the dissociation entropy at 154–157 J mol<sup>−1</sup> K<sup>−1</sup>.<ref name="togeas">{{cite journal | vauthors = Togeas JB | title = Acetic acid vapor: 2. A statistical mechanical critique of vapor density experiments | journal = The Journal of Physical Chemistry A | volume = 109 | issue = 24 | pages = 5438–5444 | date = June 2005 | pmid = 16839071 | doi = 10.1021/jp058004j | bibcode = 2005JPCA..109.5438T }}</ref> Other carboxylic acids engage in similar intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = McMurry J |title=Organic Chemistry|url=https://archive.org/details/organicchemistry00youn|url-access=registration|edition=5th|year=2000|publisher=Brooks/Cole|isbn=978-0-534-37366-5|page=818}}</ref> | |||

| === Solvent properties === | |||

| The ] ], derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to the biochemistry of virtually all forms of life. When bound to ] it is central to the ] of ]s and ]s. However, the concentration of free acetic acid in cells is kept at a low level, to avoid disrupting the control of the ] of the cell contents. | |||

| ] acetic acid is a ] (]) ], similar to ] and ]. With a ] (dielectric constant) of 6.2, it dissolves not only polar compounds such as inorganic salts and ]s, but also non-polar compounds such as oils as well as polar solutes. It is miscible with polar and non-polar ]s such as water, ], and ]. With higher alkanes (starting with ]), acetic acid is not ] at all compositions, and solubility of acetic acid in alkanes declines with longer n-alkanes.<ref name="Zieborak">{{cite journal | vauthors = Zieborak K, Olszewski K |title=Solubility of n-paraffins in acetic acid |journal = Bulletin de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences, Série des Sciences Chimiques, Géologiques et Géographiques |year = 1958|volume = 6|issue=2|pages=3315–3322}}</ref> The solvent and ] properties of acetic acid make it a useful industrial chemical, for example, as a solvent in the production of ].<ref name=Ullmann>{{Ullmann | vauthors = Le Berre C, Serp P, Kalck, P, Torrence GP | title = Acetic Acid | doi = 10.1002/14356007.a01_045.pub3|year=2013|publisher=Wiley-VCH|location=Weinheim}}</ref> | |||

| === Biochemistry === | |||

| Unlike some longer-chain carboxylic acids (the ]), acetic acid does not occur in natural ]s. However, the artificial triglyceride ] (glycerin triacetate) is a common food additive, and is found in cosmetics and topical medicines. | |||

| At physiological pHs, acetic acid is usually fully ionised to ] in aqueous solution.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Zumdahl |first=Steven S. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x6TuAAAAMAAJ |title=Chemistry |date=1986 |publisher=D.C. Heath |isbn=978-0-669-04529-1 |location=Lexington, Mass |pages=627}}</ref> | |||

| The ] ], formally derived from acetic acid, is fundamental to all forms of life. Typically, it is bound to ] by ] enzymes,<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Schwer B, Bunkenborg J, Verdin RO, Andersen JS, Verdin E | title = Reversible lysine acetylation controls the activity of the mitochondrial enzyme acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 103 | issue = 27 | pages = 10224–10229 | date = July 2006 | pmid = 16788062 | pmc = 1502439 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0603968103 | doi-access = free }}</ref> where it is central to the ] of ]s and ]s. Unlike longer-chain carboxylic acids (the ]), acetic acid does not occur in natural ]s. Most of the acetate generated in cells for use in ] is synthesized directly from ] or ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bose S, Ramesh V, Locasale JW | title = Acetate Metabolism in Physiology, Cancer, and Beyond | journal = Trends in Cell Biology | volume = 29 | issue = 9 | pages = 695–703 | date = September 2019 | pmid = 31160120 | pmc = 6699882 | doi = 10.1016/j.tcb.2019.05.005 }}</ref> However, the artificial triglyceride ] (glycerine triacetate) is a common food additive and is found in cosmetics and topical medicines; this additive is metabolized to ] and acetic acid in the body.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fiume MZ | title = Final report on the safety assessment of triacetin | journal = International Journal of Toxicology | volume = 22 | issue = Suppl 2 | pages = 1–10 | date = June 2003 | pmid = 14555416 | doi = 10.1080/747398359 }}</ref> | |||

| Acetic acid is produced and ] by certain ], notably the '']'' genus and '']''. These bacteria are found universally in ]stuffs, ], and ], and acetic acid is produced naturally as fruits and some other foods spoil. | |||

| Acetic acid is also a component of the ] of ] and other ]s, where it appears to serve as a mild ] agent.{{ |

Acetic acid is produced and ] by ], notably the genus '']'' and '']''. These bacteria are found universally in ]stuffs, ], and ], and acetic acid is produced naturally as fruits and other foods spoil. Acetic acid is also a component of the ] of ]s and other ]s, where it appears to serve as a mild ] agent.<ref name="dict">{{cite book|title = Dictionary of Organic Compounds|edition = 6th|volume = 1 |year = 1996|location = London|publisher = Chapman & Hall|isbn = 978-0-412-54090-5| veditors = Buckingham J }}</ref> | ||

| == Production == | == Production == | ||

| ] | |||

| Acetic acid is produced industrially both synthetically and by bacterial ]. About 75% of acetic acid made for use in the chemical industry is made by the ] of ], explained below.<ref name=Ullmann /> The biological route accounts for only about 10% of world production, but it remains important for the production of vinegar because many food purity laws require vinegar used in foods to be of biological origin. Other processes are ] isomerization, conversion of ] to acetic acid, and gas phase oxidation of ] and ].<ref name = "Yoneda_2001">{{cite journal| vauthors = Yoneda N, Kusano S, Yasui M, Pujado P, Wilcher S |title=Recent advances in processes and catalysts for the production of acetic acid|journal=Applied Catalysis A: General|volume=221|issue=1–2|pages=253–265|doi=10.1016/S0926-860X(01)00800-6|year=2001}}</ref> | |||

| Acetic acid can be purified via ] using an ice bath. The water and other ] will remain liquid while the acetic acid will ] out. As of 2003–2005, total worldwide production of virgin acetic acid{{efn|Acetic acid that is manufactured by intent, rather than recovered from processing (such as the production of cellulose acetates, polyvinyl alcohol operations, and numerous acetic anhydride acylations).}} was estimated at 5 Mt/a (million tonnes per year), approximately half of which was produced in the United States. European production was approximately 1 Mt/a and declining, while Japanese production was 0.7 Mt/a. Another 1.5 Mt were recycled each year, bringing the total world market to 6.5 Mt/a.<ref name="suresh">{{cite book| vauthors = Malveda M, Funada C |year=2003|chapter-url=http://sriconsulting.com/CEH/Public/Reports/602.5000/|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111014162419/http://sriconsulting.com/CEH/Public/Reports/602.5000/|url-status=dead|archive-date=14 October 2011|chapter=Acetic Acid|title=Chemicals Economic Handbook|pages=602.5000|publisher=SRI International}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |title=Production report|journal = Chemical & Engineering News |date=11 July 2005 |pages=67–76}}</ref> Since then, the global production has increased from 10.7 Mt/a in 2010<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220423193120/https://ihsmarkit.com/products/world-petro-chemical-analysis-index.html |date=23 April 2022 }}. SRI Consulting.</ref> to 17.88 Mt/a in 2023.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/4520125/acetic-acid-market-size-and-share-analysis |title=Acetic Acid Market Size & Share Analysis - Growth Trends & Forecasts (2023 - 2028) |publisher=Mordor Intelligence |year=2023 |language=en}}</ref> The two biggest producers of virgin acetic acid are ] and ] Chemicals. Other major producers include ], ], ], ], and {{ill|Svensk Etanolkemi|sv}}.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.reportlinker.com/p02284890/Acetic-Acid.html?|title=Reportlinker Adds Global Acetic Acid Market Analysis and Forecasts|date=June 2014|work=Market Research Database|page=contents}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Acetic acid is produced both synthetically and by bacterial ]. Today, the biological route accounts for only about 10% of world production, but it remains important for vinegar production, as in much of the world food purity laws stipulate that vinegar used in foods must be of biological origin. About 75% of acetic acid made for use in the chemical industry is made by methanol carbonylation, explained below. Alternative methods account for the rest.{{Ref|Yoneda}} | |||

| Total worldwide production of virgin acetic acid is estimated at 5 Mt/a (million tonnes per year), approximately half of which is produced in the ]. ]an production stands at approximately 1 Mt/a and is declining, and 0.7 Mt/a is produced in ]. Another 1.5 Mt are recycled each year, bringing the total world market to 6.5 Mt/a.{{Ref|CENewsJuly2005}}{{Ref|CEHHAcDec2003}} The two biggest producers of virgin acetic acid are ], and ]. Other major producers include ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| === Methanol carbonylation === | === Methanol carbonylation === | ||

| Most acetic acid is produced by methanol ]. In this process, ] and ] react to produce acetic acid according to the equation: | |||

| :] | |||

| Most virgin acetic acid is produced by methanol carbonylation. In this process, ] and ] react to produce acetic acid according to the chemical equation | |||

| :] + ] → CH<sub>3</sub>COOH | |||

| The process involves ] as an intermediate, and occurs in three steps. A ], usually a metal ], is needed for the carbonylation (step 2). | |||

| :(1) CH<sub>3</sub>OH + ] → ] + H<sub>2</sub>O | |||

| :(2) CH<sub>3</sub>I + ] → CH<sub>3</sub>COI | |||

| The process involves ] as an intermediate, and occurs in three steps. A ] ] is needed for the carbonylation (step 2).<ref name = "Yoneda_2001" /> | |||

| :(3) CH<sub>3</sub>COI + H<sub>2</sub>O → CH<sub>3</sub>COOH + HI | |||

| #{{chem2|CH3OH + HI → CH3I + H2O}} | |||

| #{{chem2|CH3I + CO → CH3COI}} | |||

| #{{chem2|CH3COI + H2O → CH3COOH + HI}} | |||

| Two related processes exist for the carbonylation of methanol: the rhodium-catalyzed ], and the iridium-catalyzed ]. The latter process is ] and more efficient and has largely supplanted the former process.<ref name="lancaster" /> Catalytic amounts of water are used in both processes, but the Cativa process requires less, so the ] is suppressed, and fewer by-products are formed. | |||

| By altering the process conditions, ] may also be produced on the same plant. | |||

| By altering the process conditions, ] may also be produced in plants using rhodium catalysis.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zoeller JR, Agreda VH, Cook SL, Lafferty NL, Polichnowski SW, Pond DM | title = Eastman Chemical Company Acetic Anhydride Process | journal = ] | year = 1992 | volume = 13 | issue = 1 | pages = 73–91 | doi = 10.1016/0920-5861(92)80188-S}}</ref> | |||

| Because both methanol and carbon monoxide are commodity raw materials, methanol carbonylation long appeared to be an attractive method for acetic acid production, and ]s on such processes were granted as early as the 1920s. However, the high ]s needed (200 ] or more) discouraged commercialisation of these routes for some time. The first commercial methanol carbonylation process, which used a ] catalyst, was developed by ] in 1963. In 1968, a ]-based catalyst (''cis''-<sup>−</sup>) was discovered that could operate efficiently at lower pressure with almost no by-products. The first plant using this catalyst was built by ] in 1970, and rhodium-catalysed methanol carbonylation became the dominant method of acetic acid production (see ]). In the late 1990s, ] commercialised the ]® catalyst (<sup>−</sup>) which is promoted by ]. This ]-catalysed process is ] and more efficient{{Ref|Lancaster}} and has largely supplanted the Monsanto process, often in the same production plants. | |||

| === Acetaldehyde oxidation === | === Acetaldehyde oxidation === | ||

| Prior to the commercialization of the Monsanto process, most acetic acid was produced by oxidation of ]. This remains the second-most-important manufacturing method, although it is usually not competitive with the carbonylation of methanol. The acetaldehyde can be produced by ]. This was the dominant technology in the early 1900s.<ref>{{cite journal|doi=10.1055/s-2007-966002|title=Catalytic Hydration of Alkynes and Its Application in Synthesis |journal=Synthesis |volume=2007 |issue=8 |pages=1121–1150 |year=2007 | vauthors = Hintermann L, Labonne A }}</ref> | |||

| Light ] components are readily oxidized by oxygen or even air to give ], which decompose to produce acetic acid according to the ], illustrated with ]: | |||

| Prior to the commercialisation of the Monsanto process, most acetic acid was produced by oxidation of ]. This remains the second most important manufacturing method, although it is uncompetitive with methanol carbonylation. The acetaldehyde may be produced via ] of butane or light naphtha, or by hydration of ethylene. | |||

| :{{chem2|2 C4H10 + 5 O2 → 4 CH3CO2H + 2 H2O}} | |||

| Such oxidations require metal catalyst, such as the ] ]s of ], ], and ]. | |||

| The typical reaction is conducted at ]s and pressures designed to be as hot as possible while still keeping the butane a liquid. Typical reaction conditions are {{convert|150|C|F}} and 55 atm.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Chenier PJ |title=Survey of Industrial Chemistry|edition=3rd|year=2002|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-306-47246-6|page=151}}</ref> Side-products may also form, including ], ], ], and ]. These side-products are also commercially valuable, and the reaction conditions may be altered to produce more of them where needed. However, the separation of acetic acid from these by-products adds to the cost of the process.<ref name="Sano_1999">{{cite journal| vauthors = Sano K, Uchida H, Wakabayashi S |year=1999|title=A new process for acetic acid production by direct oxidation of ethylene|journal=Catalysis Surveys from Japan|volume=3|issue=1|pages=55–60|issn=1384-6574|doi=10.1023/A:1019003230537|s2cid=93855717}}</ref> | |||

| When ] or light ] is heated with air in the presence of various metal ]s, including those of ], ] and ], ]s form and then decompose to produce acetic acid according to the ] | |||

| Similar conditions and ]s are used for butane oxidation, the ] in ] to produce acetic acid can oxidize ].<ref name="Sano_1999" /> | |||

| : 2 ] + 5 ] → 4 CH<sub>3</sub>COOH + 2 ] | |||

| :{{chem2|2 CH3CHO + O2 → 2 CH3CO2H}} | |||

| Typically, the reaction is run at a combination of ] and pressure designed to be as hot as possible while still keeping the butane a liquid. Typical reaction conditions are 150 °C and 55 atm. Several side products may also form, including ], ], ], and ]. These side products are also commercially valuable, and the reaction conditions may be altered to produce more of them if this is economically useful. However the separation of acetic acid from these by-products adds to the cost of the process. | |||

| Using modern catalysts, this reaction can have an acetic acid yield greater than 95%. The major side-products are ], ], and ], all of which have lower ]s than acetic acid and are readily separated by ].<ref name="Sano_1999" /> | |||

| Under similar conditions and using similar ]s as are used for butane oxidation, ] can be oxidised by the ] in ] to produce acetic acid | |||

| === Ethylene oxidation === | |||

| :2 ] + ] → 2 CH<sub>3</sub>COOH | |||

| Acetaldehyde may be prepared from ] via the ], and then oxidised as above. | |||

| In more recent times, chemical company ], which opened an ethylene oxidation plant in ], Japan, in 1997, commercialised a cheaper single-stage conversion of ethylene to acetic acid.<ref name="Sano_1999" /> The process is catalyzed by a ] metal catalyst supported on a ] such as ]. A similar process uses the same metal catalyst on silicotungstic acid and silica:<ref name=Misono>{{cite journal | vauthors = Misono M | year = 2009 | title = Recent progress in the practical applications of heteropolyacid and perovskite catalysts: Catalytic technology for the sustainable society | journal = Catalysis Today | volume = 144 | issue = 3–4| pages = 285–291 | doi = 10.1016/j.cattod.2008.10.054}}</ref> | |||

| Using modern catalysts, this reaction can have an acetic acid yield greater than 95%. The major side products are ], ], and ], all of which have lower ]s than acetic acid and are readily separated by ]. | |||

| :{{chem2|C2H4 + O2 → CH3CO2H}} | |||

| === Ethylene oxidation === | |||

| It is thought to be competitive with methanol carbonylation for smaller plants (100–250 kt/a), depending on the local price of ethylene. | |||

| === Oxidative fermentation === | === Oxidative fermentation === | ||

| For most of human history, acetic acid bacteria of the genus '']'' have made acetic acid, in the form of vinegar. Given sufficient oxygen, these bacteria can produce vinegar from a variety of alcoholic foodstuffs. Commonly used feeds include ], ], and fermented ], ], ], or ] mashes. The overall chemical reaction facilitated by these bacteria is: | |||

| :{{chem2|C2H5OH + O2 → CH3COOH + H2O}} | |||

| ''Main article: ]'' | |||

| A dilute alcohol solution inoculated with ''Acetobacter'' and kept in a warm, airy place will become vinegar over the course of a few months. Industrial vinegar-making methods accelerate this process by improving the supply of ] to the bacteria.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Chotani GK, Gaertner AL, Arbige MV, Dodge TC |title=Kent and Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology|year=2007|publisher=Springer|isbn=978-0-387-27842-1|pages=32–34|chapter=Industrial Biotechnology: Discovery to Delivery|bibcode=2007karh.book...... }}</ref> | |||

| For most of human history, acetic acid, in the form of vinegar, has been made by bacteria of the genus '']''. Given sufficient oxgyen, these bacteria can produce vinegar from a variety of alcoholic foodstuffs. Commonly used feeds include ], ], and fermented ], ], ], or ] mashes. The overall chemical reaction facilitated by these bacteria is | |||

| The first batches of vinegar produced by fermentation probably followed errors in the ] process. If ] is fermented at too high a temperature, acetobacter will overwhelm the ] naturally occurring on the ]. As the demand for vinegar for culinary, medical, and sanitary purposes increased, vintners quickly learned to use other organic materials to produce vinegar in the hot summer months before the grapes were ripe and ready for processing into wine. This method was slow, however, and not always successful, as the vintners did not understand the process.<ref name="Hromatka">{{cite journal|title = Vinegar by Submerged Oxidative Fermentation| vauthors = Hromatka O, Ebner H |journal = Industrial & Engineering Chemistry|year = 1959|volume = 51|issue = 10|pages = 1279–1280| doi = 10.1021/ie50598a033}}</ref> | |||

| : ] + ] → CH<sub>3</sub>COOH + ] | |||

| One of the first modern commercial processes was the "fast method" or "German method", first practised in Germany in 1823.<!-- http://www.google.de/patents?id=-stnAAAAEBAJ --> In this process, fermentation takes place in a tower packed with wood shavings or ]. The alcohol-containing feed is trickled into the top of the tower, and fresh ] supplied from the bottom by either natural or forced ]. The improved air supply in this process cut the time to prepare vinegar from months to weeks.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Acetic Acid and Cellulose Acetate in the United States A General Survey of Economic and Technical Developments| vauthors = Partridge EP |journal = Industrial & Engineering Chemistry|year = 1931|volume = 23|issue =5|pages = 482–498|doi = 10.1021/ie50257a005}}</ref> | |||

| A dilute alcohol solution, innoculated with ''Acetobacter'' and kept in a warm, airy place, will become vinegar over the course of a few months. Industrial vinegar-making methods accelerate this process by improving the supply of ] to the bacteria. | |||

| Nowadays, most vinegar is made in submerged tank ], first described in 1949 by Otto Hromatka and Heinrich Ebner.<ref>{{cite journal|title = Investigations on vinegar fermentation: Generator for vinegar fermentation and aeration procedures| vauthors = Hromatka O, Ebner H |journal = Enzymologia|volume=13|page=369|year = 1949}}</ref> In this method, alcohol is fermented to vinegar in a continuously stirred tank, and oxygen is supplied by bubbling air through the solution. Using modern applications of this method, vinegar of 15% acetic acid can be prepared in only 24 hours in batch process, even 20% in 60-hour fed-batch process.<ref name="Hromatka" /> | |||

| One of the first such processes was the "fast method" or "German method," first practised in Germany in 1823. In this process, fermentation takes place in a tower packed with wood shavings or ]. The alcohol-containing feed is trickled into the top of the tower, and fresh ] supplied from the bottom by either natural or forced ]. The improved air supply in this process cut the time to prepare vinegar from months to weeks. | |||

| Most vinegar today is made in submerged tank ], first described in 1949 by Otto Hromatka and Heinrich Ebner. In this method, alcohol is fermented to vinegar in a continuously stirred tank, and oxygen is supplied by bubbling air through the solution. Using this method, vingear of 15% acetic acid can be prepared in only 2–3 days. | |||

| === Anaerobic fermentation === | === Anaerobic fermentation === | ||

| Species of ], including members of the genus '']'' or '']'', can convert sugars to acetic acid directly without creating ethanol as an intermediate. The overall chemical reaction conducted by these bacteria may be represented as: | |||

| :{{chem2|C6H12O6 → 3 CH3COOH}} | |||

| These ]ic bacteria produce acetic acid from one-carbon compounds, including methanol, ], or a mixture of ] and ]: | |||

| Some species of ], including several members of the genus '']'', can convert sugars to acetic acid directly, without using ethanol as an intermediate. The overall chemical reaction conducted by these bacteria may be represented as: | |||

| :{{chem2|2 CO2 + 4 H2 → CH3COOH + 2 H2O}} | |||

| This ability of ''Clostridium'' to metabolize sugars directly, or to produce acetic acid from less costly inputs, suggests that these bacteria could produce acetic acid more efficiently than ethanol-oxidizers like ''Acetobacter''. However, ''Clostridium'' bacteria are less acid-tolerant than ''Acetobacter''. Even the most acid-tolerant ''Clostridium'' strains can produce vinegar in concentrations of only a few per cent, compared to ''Acetobacter'' strains that can produce vinegar in concentrations up to 20%. At present, it remains more cost-effective to produce vinegar using ''Acetobacter'', rather than using ''Clostridium'' and concentrating it. As a result, although acetogenic bacteria have been known since 1940, their industrial use is confined to a few niche applications.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = Enzyme and Microbial Technology | volume = 40 | issue = 5 | year = 2007 | pages = 1234–1243 | doi = 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2006.09.017 | title = Clostridium aceticum—A potential organism in catalyzing carbon monoxide to acetic acid: Application of response surface methodology | vauthors = Sim JH, Kamaruddin AH, Long WS, Najafpour G }}</ref> | |||

| : ] → 3 CH<sub>3</sub>COOH | |||

| == Uses == | |||

| More interestingly from the point of view of an industrial chemist, many of these '''acetogenic bacteria''' can produce acetic acid from one-carbon compounds, including ], ], or a mixture of ] and ]: | |||

| Acetic acid is a chemical ] for the production of chemical compounds. The largest single use of acetic acid is in the production of vinyl acetate ], closely followed by acetic anhydride and ester production. The volume of acetic acid used in vinegar is comparatively small.<ref name = Ullmann /><ref name="suresh" /> | |||

| : 2 ] + 4 ] → CH<sub>3</sub>COOH + 2 ] | |||

| This ability of ''Clostridium'' to utilize sugars directly, or to produce acetic acid from less costly inputs, means that these bacteria could potentially produce acetic acid more efficiently than ethanol-oxidizers like ''Acetobacter''. However, ''Clostridium'' bacteria are less acid-tolerant than ''Acetobacter''. Even the most acid-tolerant ''Clostridium'' strains can produce vinegar of only a few percent acetic acid, compared to some ''Acetobacter'' strains that can produce vinegar of up to 20% acetic acid. At present, it remains more cost-effective to produce vinegar using ''Acetobacter'' than to produce it using ''Clostridium'' and then concentrating it. As a result, although acetogenic baceteria have been known since 1940, their industrial use remains confined to a few niche applications. | |||

| == Applications == | |||

| Acetic acid is a chemical ] for the production of many chemical compounds. The largest single use of acetic acid is in the production of vinyl acetate ], closely followed by acetic anhydride and ester production. The volume of acetic acid used in ] is comparatively small. | |||

| === Vinyl acetate monomer === | === Vinyl acetate monomer === | ||

| The primary use of acetic acid is the production of ] monomer (VAM). In 2008, this application was estimated to consume a third of the world's production of acetic acid.<ref name = Ullmann /> The reaction consists of ] and acetic acid with ] over a ] ], conducted in the gas phase.<ref name=vinyl-esters>{{Ullmann|title=Vinyl Esters| vauthors = Roscher G |doi=10.1002/14356007.a27_419}}</ref> | |||

| :{{chem2|2 H3C\sCOOH + 2 C2H4 + O2 → 2 H3C\sCO\sO\sCH\dCH2 + 2 H2O}} | |||

| Vinyl acetate can be polymerised to ] or other ], which are components in ]s and ]s.<ref name=vinyl-esters /> | |||

| === Ester production === | |||

| The major use of acetic acid is for the production of ]. This application consumes approximately 40 to 45% of the worlds production of acetic acid. The reaction is of ] and acetic acid with ] over a ] ]. | |||

| The major ]s of acetic acid are commonly used as solvents for ]s, ]s and ]s. The esters include ], ''n''-], ], and ]. They are typically produced by ] reaction from acetic acid and the corresponding ]: | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3COO\sH + HO\sR → CH3COO\sR + H2O}}, R = general ] | |||

| : H<sub>3</sub>C-COOH + ] → ] | |||

| For example, acetic acid and ] gives ] and ]. | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3COO\sH + HO\sCH2CH3 → CH3COO\sCH2CH3 + H2O}} | |||

| Most acetate ], however, are produced from ] using the ]. In addition, ether acetates are used as solvents for ], ]s, ] removers, and wood stains. First, glycol monoethers are produced from ] or ] with alcohol, which are then esterified with acetic acid. The three major products are ethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate (EEA), ethylene glycol monobutyl ether acetate (EBA), and propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PMA, more commonly known as PGMEA in semiconductor manufacturing processes, where it is used as a resist solvent). This application consumes about 15% to 20% of worldwide acetic acid. Ether acetates, for example EEA, have been shown to be harmful to human reproduction.<ref name="suresh" /> | |||

| Vinyl acetate can be polymerized to ] or to other ], which are applied in ]s and ]s. | |||

| === Acetic anhydride === | === Acetic anhydride === | ||

| The product of the ] of two molecules of acetic acid is ]. The worldwide production of acetic anhydride is a major application, and uses approximately 25% to 30% of the global production of acetic acid. The main process involves dehydration of acetic acid to give ] at 700–750 °C. Ketene is thereafter reacted with acetic acid to obtain the anhydride:<ref name = acetic-anh>{{Ullmann | title = Acetic Anhydride and Mixed Fatty Acid Anhydrides | vauthors = Held H, Rengstl A, Mayer D | doi = 10.1002/14356007.a01_065}}</ref> | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3CO2H → CH2\dC\dO + H2O}} | |||

| The ] product of two molecules of acetic acid is ]. The worldwide production of acetic anhydride is a major application, and uses approximately 25 to 30% of the global production of acetic acid. Acetic anhydride may be produced directly by ] bypassing the acid, and many ] plants switch between acid and anhydride production. | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3CO2H + CH2\dC\dO → (CH3CO)2O}} | |||

| Acetic anhydride is an ] agent. As such, its major application is for ], a synthetic ] also used for ]. Acetic anhydride is also a reagent for the production of ] and other compounds.<ref name = acetic-anh /> | |||

| ] | |||

| === Use as solvent === | |||

| Acetic anhydride is a strong ] agent. As such, its major application is for ], a synthetic ] also used for ]. Acetic anhydride is also a reagent for the production of ], ], and other compounds. | |||

| As a polar ], acetic acid is frequently used for ] to purify organic compounds. Acetic acid is used as a ] in the production of ] (TPA), the raw material for ] (PET). In 2006, about 20% of acetic acid was used for TPA production.<ref name="suresh" /> | |||

| Acetic acid is often used as a solvent for reactions involving ]s, such as ]. For example, one stage in the commercial manufacture of synthetic ] involves a ] of ] to ]; here acetic acid acts both as a solvent and as a ] to trap the ] carbocation.<ref name="sell">{{cite book| vauthors = Sell CS |title=The Chemistry of Fragrances: From Perfumer to Consumer|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=G90hcKHwrqEC&pg=PA80|edition=2nd |series=RSC Paperbacks Series|volume=38|year=2006|publisher=Royal Society of Chemistry|location=Great Britain|isbn=978-0-85404-824-3|page=80|chapter=4.2.15 Bicyclic Monoterpenoids}}</ref> | |||

| === Ester production === | |||

| Glacial acetic acid is used in analytical chemistry for the estimation of weakly alkaline substances such as organic amides. Glacial acetic acid is a much weaker ] than water, so the amide behaves as a strong base in this medium. It then can be titrated using a solution in glacial acetic acid of a very strong acid, such as ].<ref name="Felgner">{{cite web |url=http://www.sigmaaldrich.com/technical-documents/articles/analytical-applications/karl-fischer/water-determination-in-perchloric-acid-0-1-mol-l-in-acetic-acid.html |title=Determination of Water Content in Perchloric acid 0,1 mol/L in acetic acid Using Karl Fischer Titration | vauthors = Felgner A |publisher=Sigma-Aldrich |access-date=27 July 2017}}</ref> | |||

| The major ]s of acetic acid are commonly used ]s for ]s, ]s and ]s. The esters include ], n-], ], and ]. They are typically produced by ] reaction from acetic acid and the corresponding ] | |||

| === Medical use === | |||

| : H<sub>3</sub>C-COOH + ] → ] + ] | |||

| {{Main|Acetic acid (medical use)}} | |||

| Acetic acid injection into a tumor has been used to treat cancer since the 1800s.<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Barclay J |title=Injection of Acetic Acid in Cancer |journal=Br Med J|year=1866|pmc=2310334|page=512|volume=2|issue=305|doi=10.1136/bmj.2.305.512-a}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Yamamoto S, Iguchi Y, Shibata N, Takesue M, Tsunoda T, Sato K | title = | journal = Gan to Kagaku Ryoho. Cancer & Chemotherapy | volume = 25 | issue = 5 | pages = 751–755 | date = April 1998 | pmid = 9571976 }}</ref> | |||

| Acetic acid is used as part of ] in many areas in the ].<ref name=Fok2015 /> The acid is applied to the ] and if an area of white appears after about a minute the test is positive.<ref name=Fok2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fokom-Domgue J, Combescure C, Fokom-Defo V, Tebeu PM, Vassilakos P, Kengne AP, Petignat P | title = Performance of alternative strategies for primary cervical cancer screening in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy studies | journal = BMJ | volume = 351 | pages = h3084 | date = July 2015 | pmid = 26142020 | pmc = 4490835 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.h3084 }}</ref> | |||

| ::where R = a general ] | |||

| Acetic acid is an effective antiseptic when used as a 1% solution, with broad spectrum of activity against streptococci, staphylococci, pseudomonas, enterococci and others.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Madhusudhan VL | title = Efficacy of 1% acetic acid in the treatment of chronic wounds infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa: prospective randomised controlled clinical trial | journal = International Wound Journal | volume = 13 | issue = 6 | pages = 1129–1136 | date = December 2016 | pmid = 25851059 | pmc = 7949569 | doi = 10.1111/iwj.12428 | s2cid = 4767974 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ryssel H, Kloeters O, Germann G, Schäfer T, Wiedemann G, Oehlbauer M | title = The antimicrobial effect of acetic acid--an alternative to common local antiseptics? | journal = Burns | volume = 35 | issue = 5 | pages = 695–700 | date = August 2009 | pmid = 19286325 | doi = 10.1016/j.burns.2008.11.009 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/456300_4|title=Antiseptics on Wounds: An Area of Controversy|website=www.medscape.com|access-date=15 August 2016}}</ref> It may be used to treat skin infections caused by pseudomonas strains resistant to typical antibiotics.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nagoba BS, Selkar SP, Wadher BJ, Gandhi RC | title = Acetic acid treatment of pseudomonal wound infections--a review | journal = Journal of Infection and Public Health | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = 410–415 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 23999348 | doi = 10.1016/j.jiph.2013.05.005 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| Most acetate esters however are being produced from ] using the ]. | |||

| While diluted acetic acid is used in ], no high quality evidence supports this treatment for rotator cuff disease.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Page MJ, Green S, Mrocki MA, Surace SJ, Deitch J, McBain B, Lyttle N, Buchbinder R | title = Electrotherapy modalities for rotator cuff disease | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 2016 | issue = 6 | pages = CD012225 | date = June 2016 | pmid = 27283591 | pmc = 8570637 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD012225 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Habif TP |title=Clinical Dermatology|date=2009|publisher=Elsevier Health Sciences|isbn=978-0-323-08037-8|page=367|edition=5th|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kDWlWR5UbqQC&pg=PA367}}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, some ether acetates are used for solvents for ], ], ] removers and wood stains. First glycol monoethers are produced from ] or ] with alcohol, which are then esterified with acetic acid. The three major products are ethylene glycol monoethyl ether acetate (EEA), ethylene glycol monobutyl ether acetate (EBA), and propylene glycol monomethyl ether acetate (PMA). Some of these ether acetates, e.g., EEA, have been shown to be harmful to human reproduction. | |||

| As a treatment for ], it is on the ].<ref name="WHO23rd">{{cite book | vauthors = ((World Health Organization)) | title = The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023) | year = 2023 | hdl = 10665/371090 | author-link = World Health Organization | publisher = World Health Organization | location = Geneva | id = WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02 | hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| This application consumes about 15 to 20% of worldwide acetic acid. | |||

| === |

=== Foods === | ||

| {{Main|Vinegar}} | |||

| Acetic acid has {{cvt|349|kcal|kJ}} per 100 g.<ref name="FAOSouthgate">{{cite book| vauthors = Greenfield H, Southgate D |date=2003|title=Food Composition Data: Production, Management and Use|location=Rome|publisher=]|page=146|isbn=9789251049495}}</ref> Vinegar is typically no less than 4% acetic acid by mass.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-afda-ice/documents/webcontent/ucm074471.pdf|title=CPG Sec. 525.825 Vinegar, Definitions|publisher=United States Food and Drug Administration|date=March 1995}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/PDF/C.R.C.,_c._870.pdf|title=Departmental Consolidation of the Food and Drugs Act and the Food and Drug Regulations – Part B – Division 19|publisher=Health Canada|date=August 2018|page=591}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32016R0263&from=EN|title=Commission Regulation (EU) 2016/263|work=Official Journal of the European Union|publisher=European Commission|date=February 2016}}</ref> Legal limits on acetic acid content vary by jurisdiction. Vinegar is used directly as a ], and in the ] of vegetables and other foods. Table vinegar tends to be more diluted (4% to 8% acetic acid), while commercial food pickling employs solutions that are more concentrated. The proportion of acetic acid used worldwide as vinegar is not as large as industrial uses, but it is by far the oldest and best-known application.<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Bernthsen A, Sudborough JJ |title=Organic Chemistry|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.513637|year=1922|publisher=Blackie and Son|location=London|page=155}}</ref> | |||

| == Reactions == | |||

| In the form of ], acetic acid solutions (typically 5 to 18%) are used directly as a ], and also in the ] of vegetables and other foodstuffs. The amount of acetic acid consumed for vinegar production on a worldwide scale is not large, but historically, this is by far the oldest and most known application. | |||

| === Organic chemistry === | |||

| {{Image frame|align=none|caption=Two typical organic reactions of acetic acid|width=400|innerstyle=display:flex;|content=<!-- | |||

| === Use as ] === | |||

| -->{{Biochem reaction subunit|compound=acetyl chloride|image=Acetyl chloride.svg|class=skin-invert-image|imagesize=80px}}<!-- | |||

| -->{{Biochem reaction subunit|direction=reverse|imagesize=60px|overarrow=]}}<!-- | |||

| -->{{Biochem reaction subunit|compound=acetic acid|image=Acetic acid Structural Formula V1.svg|class=skin-invert-image|imagesize=80px}}<!-- | |||

| -->{{Biochem reaction subunit|direction=forward|imagesize=60px|overarrow=(i) }}]], ]|underarrow=(ii) {{H3O+}}}}<!-- | |||

| -->{{Biochem reaction subunit|compound=ethanol|image=Ethanol Skelett.svg|class=skin-invert-image|imagesize=80px}}<!-- | |||

| -->}} | |||

| Acetic acid undergoes the typical ]s of a carboxylic acid. Upon treatment with a standard base, it converts to metal ] and ]. With strong bases (e.g., organolithium reagents), it can be doubly deprotonated to give {{chem2|LiCH2COOLi}}. Reduction of acetic acid gives ethanol. The OH group is the main site of reaction, as illustrated by the conversion of acetic acid to ]. Other substitution derivatives include ]; this ] is produced by ] from two molecules of acetic acid. ]s of acetic acid can likewise be formed via ], and ]s can be formed. When heated above {{convert|440|C|F}}, acetic acid decomposes to produce ] and ], or to produce ] and water:<ref>{{cite journal|title=The thermal decomposition of acetic acid|journal=Journal of the Chemical Society B: Physical Organic|year=1968|pages=1153–1155| vauthors = Blake PG, Jackson GE |doi=10.1039/J29680001153}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|journal=Journal of the Chemical Society|year=1949|title=608. The thermal decomposition of acetic acid| vauthors = Bamford CH, Dewar MJ|doi=10.1039/JR9490002877|pages=2877}}</ref><ref name="Duan1995">{{cite journal| vauthors = Duan X, Page M |year=1995|title=Theoretical Investigation of Competing Mechanisms in the Thermal Unimolecular Decomposition of Acetic Acid and the Hydration Reaction of Ketene|journal=Journal of the American Chemical Society|volume=117|issue=18|pages=5114–5119|issn=0002-7863|doi=10.1021/ja00123a013|bibcode=1995JAChS.117.5114D }}</ref> | |||

| Glacial acetic acid is an excellent polar ], as noted ]. It is frequently used as a solvent for ], to purify organic compounds. Pure molten acetic acid is used as a ] in the production of ] (TPA), the raw material for ] (PET). Although currently accounting for 5-10% of acetic acid use worldwide, this specific application is expected to grow significantly in the next decade, as PET production increases. | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3COOH → CH4 + CO2}} | |||

| Acetic acid is often used as a solvent for reactions involving ]s, such as ] and ] ]. For example, one stage in the commercial manufacture of synthetic ] involves a ] of camphene to isobornyl acetate; here acetic acid acts both as a solvent and as a ] to trap the rearranged carbocation. | |||

| :{{chem2|CH3COOH → CH2\dC\dO + H2O}} | |||

| === Reactions with inorganic compounds === | |||

| Acetic acid is the solvent of choice when ] an ] ]-group to an ] using ]. | |||

| Acetic acid is mildly ] to ]s including ], ], and ], forming ] gas and salts called ]s: | |||

| :{{chem2|Mg + 2 CH3COOH → (CH3COO)2Mg + H2}} | |||

| Because ] forms a ] acid-resistant film of ], aluminium tanks are used to transport acetic acid.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=1957-11-01 |title=Corrosion by Acetic Acid—A Report of Task Group T-5A-3 On Corrosion by Acetic Acid (1) |url=https://meridian.allenpress.com/corrosion/article/13/11/79/156728/Corrosion-by-Acetic-Acid-A-Report-of-Task-Group-T |journal=Corrosion |language=en |volume=13 |issue=11 |pages=79–88 |doi=10.5006/0010-9312-13.11.79 |issn=1938-159X}}</ref> Containers lined with glass, ] or ] are also used for this purpose.<ref name="Ullmann" /> Metal acetates can also be prepared from acetic acid and an appropriate ], as in the popular "] + vinegar" reaction giving off ]: | |||

| :{{chem2|NaHCO3 + CH3COOH → CH3COONa + CO2 + H2O}} | |||

| A ] for salts of acetic acid is ] solution, which results in a deeply red colour that disappears after acidification.<ref name="Charlot">{{cite book| vauthors = Charlot G, Murray RG |title=Qualitative Inorganic Analysis|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rzI9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA110|edition=4th|year=1954|publisher=CUP Archive|page=110}}</ref> A more sensitive test uses ] with iodine and ammonia to give a blue solution.<ref name="Neelakantam">{{cite web|url=http://repository.ias.ac.in/33062/1/33062.pdf|title=The Lanthanum Nitrate Test for Acetatein Inorganic Qualitative Analysis| vauthors = Neelakantam K, Row LR |year=1940|access-date=June 5, 2013}}</ref> Acetates when heated with ] form ], which can be detected by its ] vapours.<ref name="Brantley1947">{{cite journal| vauthors = Brantley LR, Cromwell TM, Mead JF |year=1947 |title=Detection of acetate ion by the reaction with arsenious oxide to form cacodyl oxide|journal=Journal of Chemical Education |volume=24 |issue=7 |page=353 |issn=0021-9584 |doi=10.1021/ed024p353 |bibcode=1947JChEd..24..353B}}</ref> | |||

| === Other applications === | |||

| === Other derivatives === | |||

| Dilute solutions of acetic acids are also used for their mild ], for example: | |||

| Organic or inorganic salts are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives: | |||

| * In a ] during the development of photographic films. | |||

| *], used in the ] industry and as a food ] (]). | |||

| * Treating the sting of the ] by disabling the stinging cells of the jellyfish; if the acid is immediately applied, serious injury or death may be prevented. | |||

| *], used as a ] and a ]. | |||

| * Treating ]s in people in preparations such as ]. | |||

| *] and ]—used as ]s for ]s. | |||

| * In ] spray as a ] to discourage bacterial and ] growth. | |||

| *], used as a catalyst for organic coupling reactions such as the ]. | |||

| * In descaling agents to remove ] from taps and kettles. | |||

| Halogenated acetic acids are produced from acetic acid. Some commercially significant derivatives: | |||

| *] (monochloroacetic acid, MCA), dichloroacetic acid (considered a by-product), and ]. MCA is used in the manufacture of ]. | |||

| * ] – used in the ] industry and as a food ] (]). | |||

| *], which is esterified to produce the reagent ]. | |||

| * ] – used as a ] and a ]. | |||

| *], which is a common reagent in ]. | |||

| * ] and ] – used as ]s for ]s. | |||

| * ] – used as a catalyst for organic coupling reactions such as the ]. | |||

| Amounts of acetic acid used in these other applications together account for another 5–10% of acetic acid use worldwide.<ref name="suresh" /> | |||

| Substituted acetic acids produced include: | |||

| * ] (MCA), dichloroacetic acid (considered by-product), and ]. MCA is used in the manufacture of ]. | |||

| * Bromoacetic acid, which is esterified to produce the reagent ]. | |||

| * ], which is a common reagent in ]. | |||

| == Health and safety == | |||

| Amounts of acetic acid used in these other applications together (apart from TPA) account for another 5-10% of acetic acid use worldwide. These applications are, however, not expected to grow as much as TPA production. | |||

| == |

=== Vapour === | ||

| Prolonged inhalation exposure (eight hours) to acetic acid vapours at 10 ppm can produce some irritation of eyes, nose, and throat; at 100 ppm marked lung irritation and possible damage to lungs, eyes, and skin may result. Vapour concentrations of 1,000 ppm cause marked irritation of eyes, nose and upper respiratory tract and cannot be tolerated. These predictions were based on ] and industrial exposure.<ref name="CDC">{{cite web |title=Occupational Safety and Health Guideline for Acetic Acid |url=https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/81-123/pdfs/0002-rev.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200308110415/https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/81-123/pdfs/0002-rev.pdf |archive-date=8 March 2020 |access-date=May 8, 2013 |publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention}}</ref> | |||

| In 12 workers exposed for two or more years to an airborne average concentration of 51 ppm acetic acid (estimated), symptoms of conjunctive irritation, upper respiratory tract irritation, and hyperkeratotic dermatitis were produced. Exposure to 50 ppm or more is intolerable to most persons and results in intensive ] and irritation of the eyes, nose, and throat, with pharyngeal oedema and chronic bronchitis. Unacclimatised humans experience extreme eye and nasal irritation at concentrations in excess of 25 ppm, and conjunctivitis from concentrations below 10 ppm has been reported. In a study of five workers exposed for seven to 12 years to concentrations of 80 to 200 ppm at peaks, the principal findings were blackening and hyperkeratosis of the skin of the hands, conjunctivitis (but no corneal damage), bronchitis and pharyngitis, and erosion of the exposed teeth (incisors and canines).<ref name=":0">{{cite book|publisher=Virginia Department of Health Division of Health Hazards Control| vauthors = Sherertz PC |date=June 1, 1994|title=Acetic Acid|url=http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/epidemiology/DEE/PublicHealthToxicology/documents/pdf/aceticacid.PDF|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304110629/http://www.vdh.virginia.gov/epidemiology/DEE/PublicHealthToxicology/documents/pdf/aceticacid.PDF|url-status=dead|archive-date=4 March 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| === Solution === | |||

| Concentrated acetic acid is ] and has to be handled with appropriate care, since it can cause skin burns, permanent eye damage, and irritation to the mucous membranes. These burns or blisters may not appear until several hours after exposure. ] gloves offer no protection, so specially resistant gloves, such as those made of ], should be worn when handling the compound. Concentrated acetic acid can be ignited with some difficulty in the laboratory. It becomes a flammable risk if the ambient temperature exceeds 39 °C, and can form explosive mixtures with air above this temperature (]s: 5.4–16%). | |||

| Concentrated acetic acid (≥ 25%) is ] to skin.<ref name="IPCS card">{{cite web|url=https://www.inchem.org/documents/icsc/icsc/eics0363.htm|title=ICSC 0363 – ACETIC ACID|publisher=International Programme on Chemical Safety|date=June 5, 2010}}</ref> These burns or blisters may not appear until hours after exposure.<ref>{{cite web |title=Standard Operating Procedure Glacial Acetic Acid |url=https://chemistry.ucmerced.edu/sites/chemistry.ucmerced.edu/files/page/documents/ejm_acetic_acid.pdf |publisher=UCMERCED |access-date=19 February 2024 |date=19 October 2012}}</ref> The hazardous properties of acetic acid are dependent on the concentration of the (typically ]) solution, with the most significant increases in hazard levels at thresholds of 25% and 90% acetic acid concentration by weight. The following table summarizes the hazards of acetic acid solutions by concentration:<ref name=ECHA>{{cite web |title=C&L Inventory |url=https://echa.europa.eu/information-on-chemicals/cl-inventory-database/-/discli/details/85625 |access-date=2023-12-13 |website=echa.europa.eu}}</ref> | |||

| The hazards of solutions of acetic acid depend on the concentration. The following table lists the ] of acetic acid solutions: | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| <!-- EU Index no. 607-002-00-6 --> | |||

| {| {{prettytable}} | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! ]<br/>by weight | ! ]<br />by weight | ||

| ! Molarity | ! Molarity | ||

| ! ] | |||

| ! Classification | |||

| ! ] | ! ] | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 10–25% | ||

| | 1. |

| 1.67–4.16 mol/L | ||

| | {{GHS07}} | |||

| | Irritant ('''Xi''') | |||

| | {{ |

| {{H-phrases|315}} | ||

| |- | |- | ||

| | |

| 25–90% | ||

| | 4. |

| 4.16–14.99 mol/L | ||

| | {{GHS05}} | |||