| Revision as of 04:07, 19 June 2009 view source210.211.177.135 (talk) Info Box← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:38, 16 October 2024 view source Randy Kryn (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users286,863 edits →Geography and caravan routes: uppercase per direct link (Kunlun Mountains) | ||

| (157 intermediate revisions by 62 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Mountain pass in western China}} | ||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | Name = Sanju Pass | |||

| {{Infobox mountain pass | |||

| | Photo = | |||

| | name = Sanju Pass | |||

| | Caption = | |||

| | |

| photo = | ||

| | photo_caption = 1878 map of the region. The previous border claimed by the ] is shown in purple. | |||

| | Location = {{IND}} / {{CHN}} | |||

| | elevation_m = 5364 | |||

| | Range = ] | |||

| | traversed = ], 1873 | |||

| | Coordinates = {{coord|36|40|N|78|14|E|type:pass|display=inline,title}} | |||

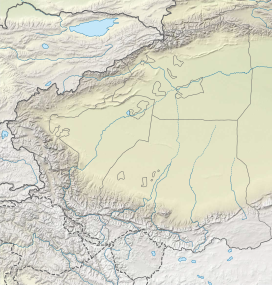

| | map = China Xinjiang Southern | |||

| | Topographic map = | |||

| | |

| label_position = top | ||

| | location = ], China | |||

| | range = ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|36.6702|78.2456|type:pass|display=title,inline}} | |||

| | topo = | |||

| | embedded = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Sanju''', or '''Sanju-la''' ({{zh|c={{linktext|桑株|古道}} |w=Sang1-chu1 ku3-tao4}}), with an elevation of {{convert|5364|m|ft}}, is a historical mountain pass in the ] in ], China. During ancient times, it was the last on a series of difficult passes on the most common summer caravan route between ] and the ]. In recent years, besides being used by the locals, it has also become a trekking route for Chinese ]s.<ref name="xjdi_穿越桑株">{{Cite web | |||

| ] (1878) showing Khotan (near top right corner) and the Sanju Pass, ], and ] passes through the ] to ] in ]. The previous border of the ] is shown in the two-toned purple and pink band. The mountain passes are shown in bright red. Double-click for details.]] | |||

| | title = 穿越桑株古道-翻越桑株达坂 | |||

| | trans-title = Through the Sanju Trail — Over the Sanju Pass | |||

| | author = 王铁男 | |||

| | website = ] Blog | |||

| | date = 2010-03-15 | |||

| | access-date = 2017-02-01 | |||

| | url = http://xjdiscovery.blog.sohu.com/146112442.html | |||

| | language = zh | |||

| }}</ref> In early 2020s, a scenic unpaved auto tour route was opened along the trail for road trippers.<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| | title = 桑株古道自驾公路即将开通 | |||

| | trans-title = The Sanju Ancient Trail Auto Tour Road is About To Open | |||

| | author = 王晶晶 | |||

| | editor = 古丽革乃·艾尔肯 | |||

| | newspaper = 新疆日报 | |||

| | trans-newspaper = Xinjiang Daily | |||

| | orig-date = 2022-09-05 | |||

| | date = 2022-09-07 | |||

| | access-date = 13 February 2024 | |||

| | url = https://www.ts.cn/xwzx/dzxw/202209/t20220907_8893039.shtml | |||

| | language = zh | |||

| | quote = | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Geography and caravan routes== | |||

| From ] to the Tarim Basin the traveller had a choice of three passes, the Kilik (not to be confused with the ] leading from the ] to the north), the Kilian Pass and the Sanju; but the usual route for caravans in the 19th century was via the '''Sanju Pass'''. | |||

| ]). The bold lines represent the ] range in the south and the "Killian range", the northern branch of the ], in the north. The Sanju Pass is on the Killian range at the centre. (Map not drawn to scale)]] | |||

| <mapframe latitude="36.6702" longitude="78.2456" zoom="8" width="260" height="227" align="right">{ | |||

| "type": "FeatureCollection", | |||

| "features": [ | |||

| { | |||

| "type": "Feature", | |||

| "properties": {}, | |||

| "geometry": { | |||

| "type": "Point", | |||

| "coordinates": [ | |||

| 78.2456, | |||

| 36.6702 | |||

| ] | |||

| } | |||

| } | |||

| ] | |||

| }</mapframe> | |||

| {{Chinese | |||

| |s={{linktext|桑株|古道}} | |||

| |t={{linktext|桑株|古道}} | |||

| |p=sāngzhū gǔdào | |||

| |s2={{linktext|桑株|达坂}} | |||

| |t2={{linktext|桑株|達坂}} | |||

| |p2=sāngzhū dábǎn | |||

| }} | |||

| Historically, the main route from Northern India to the ] led through the ] in Ladakh across the ice-covered ] ({{convert|5411|m|ft|disp=or}}) and the even higher ] ({{convert|5575|m|ft|disp=or}}) and the relatively easy ] to the staging post at ]. From there in summer the caravans normally headed north across the Sanju Pass to modern ] (Pishan) in the Tarim Basin and then either northwest to ] and ] or northeast to ]. | |||

| The Kilik Pass was reportedly once frequently used by ] merchants based in Yarkand and had plenty of fodder and fuel at every stage. It was said to be the easiest and shortest route, but merchants were not allowed to use it for political reasons. Travellers were also often prevented from accessing it for considerable periods during hot weather due to flooding of the Toghra about {{convert|14|km|abbr=on}} below Shahidula. After crossing the pass the route joined the Kugiar route at Beshterek, one day's march south of Karghalik. | |||

| After traversing the Sanju Pass, the caravans descended to the village of Sanju from where a good road led {{convert|122|mi|km}} to ], meeting up with the Kilian route at Bora and the Kilik and Kugiar routes at Karghalik.{{sfnp|Forsyth, Report of a Mission to Yarkand|1875|p=245}} | |||

| Apparently, the Kilian was previously the most frequented pass, though it was little used in the 19th century except sometimes in the summer. It is higher than the Sanju Pass and also impractical for laden horses, but reportedly not so difficult to cross. The road then descends to the village of Kilian and, after two marches one reached Bora on the road between Sanju and Karghalik.<ref>''Report of a Mission to Yarkund in 1873 : vol.1'', pp. 244-245. (1875). T. D. Forsyth. Calcutta.</ref> | |||

| From ] to the Tarim Basin the traveller had a choice of three passes, the '''Kilik''' (not to be confused with the ] leading from the ] to the north), the '''Kilian Pass''' and the Sanju; but the usual route for caravans in the 19th century was via the Sanju Pass. | |||

| The '''Sanju''', or '''Sanju-la''', (5,364 m or 17,598 ft) was the last on a series of difficult passes on the most common summer caravan route between ] and the ]. This route led from the ] in Ladakh across the ice-covered ] (5,411 m or 17,753 ft) and the even higher ] (5,575 m 18,291 ft) and the relatively easy Suget Pass to the staging post at ]. From there in summer the caravans normally headed north across the Sanju Pass to modern ]/] in the Tarim Basin and then either northwest to ] and ] or northeast to ]. | |||

| The Kilik Pass was reportedly once frequently used by ] merchants based in Yarkand and had plenty of fodder and fuel at every stage. It was said to be the easiest and shortest route, but merchants were not allowed to use it for political reasons. Travellers were also often prevented from accessing it for considerable periods during hot weather due to flooding of the Toghra about {{convert|9|mi|km}} below Shahidula. After crossing the pass the route joined the Kugiar route at Beshterek, one day's march south of Karghalik. | |||

| After crossing the Sanju, the caravans descended to the village of Sanju from where a good road led 122 miles (196 km) to ], meeting up with the Kilian route at Bora and the Kilik and Kugiar routes at Karghalik.<ref>''Report of a Mission to Yarkund in 1873 : vol.1'', p. 245. (1875). T. D. Forsyth. Calcutta. </ref> | |||

| Apparently, the Kilian was previously the most frequented pass, though it was little used in the 19th century except sometimes in the summer. It is higher than the Sanju Pass and also impractical for laden horses, but reportedly not so difficult to cross. The road then descends to the village of Kilian and, after two marches one reached Bora on the road between Sanju and Karghalik. The summit of the pass is always covered with ice and snow and is not practicable for laden ponies - ] have to be used.{{sfnp|Forsyth, Report of a Mission to Yarkand|1875|pp=244–245}} | |||

| <blockquote>The next morning, our road lay up a narrow winding gorge, northwards, with tremendous vertical cliffs on either hand. Dead horses were passed at every few hundred yards, marking the difficulties of the route. We took up our abode in a kind of cave, so as to save the delay of striking the tents in the morning. The following day, we started for the pass into Toorkistân. The gorge gradually became steeper and steeper, and dead horses more frequent. The stream was hard frozen into a torrent of white ice. The distant mountains began to show behind us, peeping over the shoulders of the nearer ones. Finally, our gorge vanished, and we were scrambling up the open shingly side of the mountain, towards the ridge.... The pass is very little lower than the rest of the ridge which tops the range. The first sight, on cresting the 'col,' was a chaos of lower mountains, while far away to the north they at last rested on what it sought, a level horizon indistinctly bounding what looked like a distant sea. This was the plain of Eastern Toorkistân, and that blue haze concealed cities and provinces, which, first of all my countrymen, I was about to visit. A step further showed a steep descent down a snow-slope, into a large basin surrounded by glaciers on three sides. This basin was occupied by undulating downs, covered with grass (a most welcome sight), and occupied by herds of yaks. <ref>''Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar'', pp. 132-133. (1871). Reprint by Oxford University Press (1984). ISBN 0-19-583830-0.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The summit of the pass is always covered with ice and snow and is not practically passable with laden ponies—] have to be used.<ref>''Report of a Mission to Yarkund in 1873 : vol.1'', p. 245. (1875). T. D. Forsyth. Calcutta.</ref> | |||

| ], 1973)]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===19th-century Kashmiri claim=== | |||

| “The eastern (Kuenlun) range forms the southern boundary of ]”<ref>Gazetteer of Kashmir and Ladak compiled under the direction of the Quarter Master General in India in the Intelligence Branch. First Published in 1890</ref>, and is crossed by other passes: the ''Sanju Pass'' near the town of Shahidulla, the ] Pass, and the ''Yangi Pass'' , in the northern part of the ] area in ] . The Hindutash pass has been used historically as the point of entry into India Proper from the ancient Indian ] which only explains the literal meaning of the name Hindutash signifying border post . The Yangi was traversed in 1865 by W. H. Johnson of the ]. W.H. Johnson’s survey established certain important points. "Brinjga was in his view the boundary post" ( near the Karanghu Tagh Peak in the Kuen Lun in Ladakh ), thus implying "that the boundary lay along the Kuen Lun Range"<ref>Himalayan Frontiers by Dorothy Woodman. Pg.67-68 , published inter alia by London Barrie and Rockliff The Cresset Press 1969.</ref>. Johnson’s findings demonstrated that the whole of the ] valley was “ within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir” and an integral part of the territory of Kashmir . "He noted where the Chinese boundary post was accepted. At Yangi Langar, three marches from Khotan, he noticed that there were a few fruit trees at this place which originally was a post or guard house of the Chinese". “The Khan wrote Johnson ‘that he had dispatched his Wazier, Saifulla Khoja to meet me at Bringja, the first encampment beyond the Ladakh boundary for the purpose of escorting me thence to Ilichi’… thus the Khotan ruler accepted the Kunlun range as the southern boundary of his dominion.”<ref>Himalayan Battleground by Margaret W. Fisher, Leo E. Rose and Robert A. Huttenback, published by Frederick A. Praeger Pg.116. </ref> According to Johnson, “the last portion of the route to Shadulla (Shahidulla) is particularly pleasant, being the whole of the Karakash valley which is wide and even, and shut in either side by rugged mountains. On this route I noticed numerous extensive plateaux near the river, covered with wood and long grass. These being within the territory of the Maharaja of Kashmir, could easily be brought under cultivation by Ladakhees and others, if they could be induced and encouraged to do so by the Kashmeer Government. The establishment of villages and habitations on this river would be important in many points of view, but chiefly in keeping the route open from the attacks of the Khergiz robbers.”<ref>Report of the Great Trigonometrical Survey of India, 1866, p.6. </ref> | |||

| During the ], the political status of ] as part of the ] became uncertain. The border between ] and the semi-independent ] with Xinjiang became a matter of some speculation. In attempt to assert control to the ]s, the Maharajah of Kashmir constructed a fort at ], and had troops stationed there for some years to protect caravans.<ref name=himalayanfrontier>{{Cite book | |||

| | last = Woodman | |||

| | first = Dorothy | |||

| | title = Himalayan Frontiers | |||

| | publisher = Barrie & Rockcliff | |||

| | year = 1969 | |||

| | pages = 101 and 360ff | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Eventually, most sources placed Shahidulla and the upper Karakash River firmly within the territory of Xinjiang. According to ], who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there - it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic ].{{sfnp|Younghusband, The Heart of a Continent|1896|pp=223-224}} The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris.<ref>Grenard (1904), pp. 28-30.</ref> There is evidence that the Chinese had mined jade in the region at least as early as the ] and up until the quarries were abandoned during the Muslim Rebellion in 1863–4, just prior to Mr. Johnson's trip in 1865.{{sfnp|Shaw, Visits to High Tartary|1871|pp=473-475}} | |||

| ] who was entrusted with the task of visiting the Court of ] pursuant to the visit on 28 March 1870 of the envoy of Atalik Ghazi, Mirza Mohammad Shadi, stated that "it would be very unsafe to define the boundary of Kashmir in the direction of the Karakoram…. Between the Karakoram and the Karakash the high Plateau is perhaps rightly described as rather a no-mans land, but I should say with a tendency to become Kashmir property". | |||

| The Chinese completed the reconquest of eastern Turkistan in 1878. Before they lost it in 1863, their practical authority, as Ney Elias British Joint Commissioner in Leh from the end of the 1870s to 1885, and Younghusband consistently maintained, '''''"had never extended south of their outposts at Sanju and Kilian along the northern foothills of the ]. Nor did they establish a known presence to the south of the line of outposts in the twelve years immediately following their return".'''''<ref>Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages 56-57, 59, 95, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi. </ref> Ney Elias who had been Joint Commissioner in Ladakh for several years noted on 21 September 1889 that he had met the Chinese in 1879 and 1880 when he visited Kashgar. '''''“they told me that they considered their line of ‘chatze’, or posts, as their frontier – viz. , Kugiar, Kilian, Sanju, Kiria, etc.- and that they had no concern with what lay beyond the mountains”'''''<ref>For. Sec. F. October 1889, 182/197.</ref> i.e. the Kuen Lun range in northern Kashmir wherein the Hindutash pass is situate. | |||

| Two stages beyond Shahidulla, as the route headed for the Sanju Pass, Forsyth's party crossed the Tughra Su and passed an outpost called Nazr Qurghan. "This is manned by soldiers from Yarkand".<ref>For. Pol.A. January 1871, 382/386, para58</ref> In the words of John Lall, "Here we have an early example of coexistence. The Kashmiri and Yarkandi outposts were only two stages apart on either side of the Karakash river..."<ref>''Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict'' by John Lall at pages 57-58, 61, 69. Allied Publishers Private Ltd, Nav Dehli</ref> to the northwest of the ] in the north eastern frontier region of Kashmir. This was the ] that existed at the time of the mission to Kashgar in 1873-74 by Forsyth. "Elias himself recalled that, following his mission to Kashgar in 1873–74, Sir Douglas Forsyth 'recommended the Maharaja's boundary to be drawn to the north of the Karakash valley as shown in the map accompanying the mission report'. Whether this was ever done is doubtful. | |||

| The ] quelled the Dungan revolt in 1878.{{citation needed|date=February 2017}} Although the Maharajah of Kashmir apparently indicated a wish to reoccupy the fort at Shahidulla in 1885, he was prevented from doing so by the British and so the territory remained under effective Chinese control.{{citation needed|date=February 2017}} | |||

| When the Government of Kashmir in 1885, at a time when the Chinese were least concerned or bothered of the alien trans- Kuen Lun areas in the ] of Kashmir , beyond their eastern Turkistan dominion and literally “had washed their hands of it<ref>Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at page 60, Allied Publishers Private Ltd, New Delhi</ref>”, prepared to reunify Kashmir and the Wazir of Ladakh , Pandit Radha Kishen initiated steps to restore the old Kashmiri outpost at Shahidulla, Ney Elias who was British Joint Commissioner in Ladakh and spying on the Government of Kashmir raised objections. “This very energetic officer’, he wrote to the resident, who duly forwarded the letter to the Government of India, “wants the Maharaja to reoccupy Shahidulla in the Karakash valley ….I see indications of his preparing to carry it out, and, in my opinion, he should be restrained, or an awkward boundary question may be raised with the Chinese '''without any compensating advantage'''<ref>Sec. F. November 1885,12/14(12) </ref>”. In the circumstances, since Elias had represented to the Supreme Government, it was a relatively simple matter for him to ensure that the plans were dropped. He told the Wazir that he had reported against the scheme to the Resident, and pretty soon the subservient Wazir succumbed and assured him that he did not intend to implement it. Elias was also promptly meticulously backed up by the Government of India. A letter dated 1 September was sent to the officer on Special Duty (as the Resident was called before 1885) instructing him to take suitable opportunity of advising His Highness the Maharaja not to occupy Shahidulla”. Elias had already killed the proposal. Kashmir, however never forfeited her territorial integrity, though she had been under ] and ] prevented from restoring the outpost at Shahidulla to command the Kuen Lun. | |||

| ===Aftermath=== | |||

| The Chinese Karawal or outpost, of Sanju was at the northern base of the Kuenlun, three stages from the pass of that name. Nevertheless, F. E. Younghusband could not disguise the objective fact that the Chinese considered the Kilian and Sanju passes as the practical limits of their territory, although they "do not like to go so far as to say that beyond the passes does not belong to them…."<ref>For.Sec.F.Pros.October 1889,182/197(184)</ref>. | |||

| Since the reasserting control of the whole region by China in 1878,{{sfnp|Millward, Eurasian Crossroads|2007|p=130}} it has been considered part of ] and has remained so ever since.<ref>Stanton, Edward. (1908) ''Atlas of the Chinese Empire''. Prepared for the ]. Morgan & Scott, Ltd. London. Map. No. 19 Sinkiang.</ref> ] is well to the north of any territories claimed by either India or Pakistan, while the Sanju and Kilian passes are further to the north of Shahidulla. A major Chinese road, ], runs from ] (Yecheng) in the ], south through Shahidulla, and across the disputed ] region still claimed by India, and into northwestern ].<ref>''National Geographic Atlas of China'', p. 28. (2008). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.</ref> | |||

| == |

==Footnotes== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| * ''Trails to Inmost Asia: Five Years of Exploration with the Roerich Central Asian Expedition'', pp. 49–51. (1931), George N. Roerich. First reprint in India. Book Faith India, Delhi. (1996) ISBN 81-7303-032-4. | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * {{citation |editor-last=Forsyth |editor-first=T. D. |editor-link=T. D. Forsyth |title=Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T.D. Forsyth with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the Ameer of Yarkund |publisher=Government of India. Foreign Department |year=1875 |url=https://archive.org/details/reportamissiont00forsgoog |via=archive.org |ref={{sfnref|Forsyth, Report of a Mission to Yarkand|1875}}}} | |||

| * Grenard, Fernand (1904). ''Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants''. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974. | |||

| * {{citation |first=James A. |last=Millward |title=Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang |publisher=Columbia University Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-231-13924-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8FVsWq31MtMC |ref={{sfnref|Millward, Eurasian Crossroads|2007}}}} | |||

| ** {{citation |first=James A. |last=Millward |title=Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang |publisher=Hurst Publishers |year=2021 |isbn=9781787386709 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XYxDEAAAQBAJ |ref={{sfnref|Millward, Eurasian Crossroads|2021}}}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Shaw |first=Robert |title=Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar |publisher=John Murray |location=London |year=1871 |url=https://archive.org/details/visitstohightart00shaw_0 |via=archive.org |ref={{sfnref|Shaw, Visits to High Tartary|1871}}}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Younghusband |first=Francis Edward |title=The Heart of a Continent |edition=Second |year=1896 |publisher=John Murray |url=https://archive.org/details/heartacontinent01unkngoog |ref={{sfnref|Younghusband, The Heart of a Continent|1896}}}} | |||

| {{Xinjiang topics}} | |||

| {{Mountain passes of China}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:38, 16 October 2024

Mountain pass in western China

| Sanju Pass | |

|---|---|

| |

| Elevation | 5,364 m (17,598 ft) |

| Traversed by | Thomas Douglas Forsyth, 1873 |

| Location | Pishan County, Xinjiang, China |

| Range | Kunlun Mountains |

| Coordinates | 36°40′13″N 78°14′44″E / 36.6702°N 78.2456°E / 36.6702; 78.2456 |

The Sanju, or Sanju-la (Chinese: 桑株古道; Wade–Giles: Sang-chu ku-tao), with an elevation of 5,364 metres (17,598 ft), is a historical mountain pass in the Kun Lun Mountains in Pishan County, Hotan Prefecture, Xinjiang, China. During ancient times, it was the last on a series of difficult passes on the most common summer caravan route between Ladakh and the Tarim Basin. In recent years, besides being used by the locals, it has also become a trekking route for Chinese trekkers. In early 2020s, a scenic unpaved auto tour route was opened along the trail for road trippers.

Geography and caravan routes

| Sanju Pass | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 桑株古道 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 桑株古道 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 桑株達坂 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 桑株达坂 | ||||||

| |||||||

Historically, the main route from Northern India to the Tarim Basin led through the Nubra Valley in Ladakh across the ice-covered Sasser Pass (5,411 metres or 17,753 feet) and the even higher Karakoram Pass (5,575 metres or 18,291 feet) and the relatively easy Suget Pass to the staging post at Shahidulla. From there in summer the caravans normally headed north across the Sanju Pass to modern Guma (Pishan) in the Tarim Basin and then either northwest to Karghalik and Yarkand or northeast to Khotan.

After traversing the Sanju Pass, the caravans descended to the village of Sanju from where a good road led 122 miles (196 km) to Yarkand, meeting up with the Kilian route at Bora and the Kilik and Kugiar routes at Karghalik.

From Shahidula to the Tarim Basin the traveller had a choice of three passes, the Kilik (not to be confused with the Kilik Pass leading from the Hunza Valley to the north), the Kilian Pass and the Sanju; but the usual route for caravans in the 19th century was via the Sanju Pass.

The Kilik Pass was reportedly once frequently used by Balti merchants based in Yarkand and had plenty of fodder and fuel at every stage. It was said to be the easiest and shortest route, but merchants were not allowed to use it for political reasons. Travellers were also often prevented from accessing it for considerable periods during hot weather due to flooding of the Toghra about 9 miles (14 km) below Shahidula. After crossing the pass the route joined the Kugiar route at Beshterek, one day's march south of Karghalik.

Apparently, the Kilian was previously the most frequented pass, though it was little used in the 19th century except sometimes in the summer. It is higher than the Sanju Pass and also impractical for laden horses, but reportedly not so difficult to cross. The road then descends to the village of Kilian and, after two marches one reached Bora on the road between Sanju and Karghalik. The summit of the pass is always covered with ice and snow and is not practicable for laden ponies - yaks have to be used.

History

19th-century Kashmiri claim

During the Dungan revolt in 1862, the political status of Xinjiang as part of the Qing dynasty became uncertain. The border between British India and the semi-independent State of Kashmir with Xinjiang became a matter of some speculation. In attempt to assert control to the Kunlun Mountains, the Maharajah of Kashmir constructed a fort at Shahidulla, and had troops stationed there for some years to protect caravans. Eventually, most sources placed Shahidulla and the upper Karakash River firmly within the territory of Xinjiang. According to Francis Younghusband, who explored the region in the late 1880s, there was only an abandoned fort and not one inhabited house at Shahidulla when he was there - it was just a convenient staging post and a convenient headquarters for the nomadic Kirghiz. The abandoned fort had apparently been built a few years earlier by the Kashmiris. There is evidence that the Chinese had mined jade in the region at least as early as the Later Han Dynasty and up until the quarries were abandoned during the Muslim Rebellion in 1863–4, just prior to Mr. Johnson's trip in 1865.

Thomas Douglas Forsyth who was entrusted with the task of visiting the Court of Atalik Ghazi pursuant to the visit on 28 March 1870 of the envoy of Atalik Ghazi, Mirza Mohammad Shadi, stated that "it would be very unsafe to define the boundary of Kashmir in the direction of the Karakoram…. Between the Karakoram and the Karakash the high Plateau is perhaps rightly described as rather a no-mans land, but I should say with a tendency to become Kashmir property".

Two stages beyond Shahidulla, as the route headed for the Sanju Pass, Forsyth's party crossed the Tughra Su and passed an outpost called Nazr Qurghan. "This is manned by soldiers from Yarkand". In the words of John Lall, "Here we have an early example of coexistence. The Kashmiri and Yarkandi outposts were only two stages apart on either side of the Karakash river..." to the northwest of the Hindutash in the north eastern frontier region of Kashmir. This was the status quo that existed at the time of the mission to Kashgar in 1873-74 by Forsyth. "Elias himself recalled that, following his mission to Kashgar in 1873–74, Sir Douglas Forsyth 'recommended the Maharaja's boundary to be drawn to the north of the Karakash valley as shown in the map accompanying the mission report'. Whether this was ever done is doubtful.

The Qing dynasty quelled the Dungan revolt in 1878. Although the Maharajah of Kashmir apparently indicated a wish to reoccupy the fort at Shahidulla in 1885, he was prevented from doing so by the British and so the territory remained under effective Chinese control.

Aftermath

Since the reasserting control of the whole region by China in 1878, it has been considered part of Xinjiang and has remained so ever since. Shahidulla is well to the north of any territories claimed by either India or Pakistan, while the Sanju and Kilian passes are further to the north of Shahidulla. A major Chinese road, China National Highway 219, runs from Kargilik (Yecheng) in the Tarim Basin, south through Shahidulla, and across the disputed Aksai Chin region still claimed by India, and into northwestern Tibet Autonomous Region.

Footnotes

- 王铁男 (2010-03-15). "穿越桑株古道-翻越桑株达坂" [Through the Sanju Trail — Over the Sanju Pass]. Sohu Blog (in Chinese). Retrieved 2017-02-01.

- 王晶晶 (2022-09-07) . 古丽革乃·艾尔肯 (ed.). "桑株古道自驾公路即将开通" [The Sanju Ancient Trail Auto Tour Road is About To Open]. 新疆日报 [Xinjiang Daily] (in Chinese). Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- Forsyth, Report of a Mission to Yarkand (1875), p. 245.

- Forsyth, Report of a Mission to Yarkand (1875), pp. 244–245.

- Woodman, Dorothy (1969). Himalayan Frontiers. Barrie & Rockcliff. pp. 101 and 360ff.

- Younghusband, The Heart of a Continent (1896), pp. 223–224.

- Grenard (1904), pp. 28-30.

- Shaw, Visits to High Tartary (1871), pp. 473–475.

- For. Pol.A. January 1871, 382/386, para58

- Aksaichin and Sino-Indian Conflict by John Lall at pages 57-58, 61, 69. Allied Publishers Private Ltd, Nav Dehli

- Millward, Eurasian Crossroads (2007), p. 130.

- Stanton, Edward. (1908) Atlas of the Chinese Empire. Prepared for the China Inland Mission. Morgan & Scott, Ltd. London. Map. No. 19 Sinkiang.

- National Geographic Atlas of China, p. 28. (2008). National Geographic Society, Washington, D.C.

References

- Forsyth, T. D., ed. (1875), Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T.D. Forsyth with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the Ameer of Yarkund, Government of India. Foreign Department – via archive.org

- Grenard, Fernand (1904). Tibet: The Country and its Inhabitants. Fernand Grenard. Translated by A. Teixeira de Mattos. Originally published by Hutchison and Co., London. 1904. Reprint: Cosmo Publications. Delhi. 1974.

- Millward, James A. (2007), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-13924-3

- Millward, James A. (2021), Eurasian Crossroads: A History of Xinjiang, Hurst Publishers, ISBN 9781787386709

- Shaw, Robert (1871), Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar, London: John Murray – via archive.org

- Younghusband, Francis Edward (1896), The Heart of a Continent (Second ed.), John Murray

| Xinjiang topics | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ürümqi (capital) | |||||||||||||||

| History |

| ||||||||||||||

| Geography |

| ||||||||||||||

| Education Research | |||||||||||||||

| Culture | |||||||||||||||

| Cuisine | |||||||||||||||

| Economy | |||||||||||||||

| Visitor attractions | |||||||||||||||

| Related |

| ||||||||||||||

| Mountain passes of China | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography of China | |||||||||||||||||||

| On the border | |||||||||||||||||||

| In the interior |

| ||||||||||||||||||