| Revision as of 09:47, 27 June 2009 view source86.20.237.23 (talk)No edit summaryTag: references removed← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:41, 6 January 2025 view source Diannaa (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators350,030 editsm more better | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|World War II landing operation in Europe}} | |||

| {{redirect|D-Day|other uses|D-Day (disambiguation)}} {{for|the use of D-Day as a general military term|D-Day (military term)}} | |||

| {{Redirect-multi|3|D-Day|Operation Neptune|Jour-J|other uses|D-Day (disambiguation)|and|Operation Neptune (disambiguation)|and|Jour J (comics)}} | |||

| {{redirect|Operation Neptune}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{dablink|This article is about the first day of the Invasion of Normandy (D-Day). The subsequent operations are covered in ].}} | |||

| {{Pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Military Conflict | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| |conflict=Operation Neptune | |||

| {{Use British English|date=November 2024}} | |||

| |partof=], ] | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | |||

| |image=] | |||

| | conflict = Normandy landings | |||

| |caption=U.S. Army troops wade ashore on Omaha Beach during the landings, 6 June 1944 | |||

| | partof = ] and the ] of the ] | |||

| |date= 6 June 1944 | |||

| | image = Into the Jaws of Death 23-0455M edit.jpg | |||

| |place=] coast and adjacent waters | |||

| | image_size = 300 | |||

| |territory=Allied beachhead in Normandy, France | |||

| | caption = '']'': men of the ] wade ashore on ] | |||

| |result=Allied victory | |||

| | date = {{Date and age|6 June 1944}} | |||

| |combatant1={{flag|United Kingdom}}<br />{{flag|United States|1912}}<br />{{flag|Canada|1921}}<br />{{flagicon|France|free}} ]<br />{{flag|Poland}}<br />{{flag|Norway}} | |||

| | place = ], ] | |||

| |combatant2={{flag|Nazi Germany|name=Nazi Germany}} | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|49.34|N|0.60|W|region:FR-NOR|display=inline,title}} | |||

| |commander1={{flagicon|United States|1912}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United States|1912}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]<br />{{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| | territory = Five Allied beachheads established in Normandy | |||

| |commander2={{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}}]<br />{{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ] <br />{{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}} ]<br />{{flagicon|Germany|Nazi}}] {{KIA}} | |||

| | result = Allied victory{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p = 342}} | |||

| |strength1=156,000 | |||

| | combatant1 = ''']:'''<br />{{plainlist | | |||

| |strength2=380,000 | |||

| * {{flag|United Kingdom}} | |||

| |casualties1= Total allied casualties (killed, wounded, missing, or captured) are estimated at approximately 10,000.<br />These comprised:<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ddaymuseum.co.uk/faq.htm#casualties |title=Frequently Asked Questions for D-Day and the Battle of Normandy (casualties) |publisher=Ddaymuseum.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2009-06-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.vac-acc.gc.ca/remembers/sub.cfm?source=history/secondwar/canada2/normandy |title=The Landings in Normandy — Veterans Affairs Canada |publisher=Vac-acc.gc.ca |date= |accessdate=2009-06-06}}</ref><br />United States–6,603, of which 1,465 fatal.<br />United Kingdom–2,700.<br />Canada–1,074, of which 359 fatal. | |||

| * {{flag|United States|1912}} | |||

| |casualties2= Between 4,000 and 9,000 dead, wounded, or captured | |||

| * {{flag|Canada|1921}} | |||

| |notes= | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Provisional Government of the French Republic}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=82}} | |||

| * {{flag|Australia}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=76}} | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Czechoslovak government-in-exile}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=492}} | |||

| * {{flagicon|Polish government-in-exile}} ]{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=82}} | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Dutch government-in-exile}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=99}} | |||

| * {{flagdeco|Norway}} ]{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=82}} | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Dominion of New Zealand|}}{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=25}} | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Greek government-in-exile}}{{sfn|Garner|2019}} | |||

| * {{flagcountry|Union of South Africa}}{{sfn|Meadows|2016}} | |||

| * {{flag|Southern Rhodesia}}{{sfn|Meadows|2016}} | |||

| }} | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagcountry|Nazi Germany}} | |||

| | commander1 = {{plainlist | | |||

| * {{nowrap|{{flagicon|United States|1912}} ]}} | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|United States|1912}} ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | commander2 = {{plainlist | | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ] | |||

| * {{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]}} | |||

| | units1 = {{collapsible list|title={{flagicon|United States|1912}} ]| | |||

| ''Omaha Beach'': | |||

| ;] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ''Utah Beach'': | |||

| ;] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{collapsible list|title={{flagicon|United Kingdom}} ]| | |||

| ''Gold Beach'': | |||

| ;] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ''Juno Beach'': | |||

| ;] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ''Sword Beach'': | |||

| ;I Corps | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | units2 = {{collapsible list|title={{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]| | |||

| ''South of Caen:'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| {{collapsible list|title={{flagicon|Nazi Germany}} ]| | |||

| ''Omaha Beach:'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| ''Utah Beach:'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| ''Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches:'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | strength1 = 156,000 soldiers{{efn|name=Allied strength|The official British history gives an estimated figure of 156,115 men landed on D-Day. This comprised 57,500 Americans and 75,215 British and Canadians from the sea and 15,500 Americans and 7,900 British from the air.{{sfn|Ellis|Allen|Warhurst|2004|pp=521–533}} }}<br />195,700 naval personnel{{sfn|Morison|1962|p=67}} | |||

| | strength2 = 50,350+{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=60, 63, 118–120}}<br />170 coastal artillery guns{{efn|Includes guns from 100mm to 210mm, as well as 320mm rocket launchers.{{sfn|Zaloga|Johnson|2005|p=29}}}} | |||

| | casualties1 = 10,000+ casualties; 4,414 confirmed dead{{efn|name=Allied casualties|The original estimate for Allied casualties was 10,000, of which 2,500 were killed. Research under way by the ] has confirmed 4,414 deaths, of which 2,499 were American and 1,915 were from other nations.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=87}}}}<br />185 ] tanks{{sfn|Napier|2015|p=72}} | |||

| | casualties2 = 4,000–9,000 killed, wounded, missing, or captured{{sfn|Portsmouth Museum Services}} | |||

| | notes = | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Normandy}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Normandy}} | |||

| The '''Normandy Landings''' were the first operations of the ] ], also known as '''Operation Neptune''' and ], during ]. The landings commenced on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 ('''D-Day'''), beginning at 6:30 ] (UTC+2). In planning, '']'' was the term used for the day of actual landing, which was dependent on final approval. | |||

| The '''Normandy landings''' were the ]s and associated airborne operations on 6 June 1944 of the ] invasion of ] in ] during the ]. Codenamed '''Operation Neptune''' and often referred to as '''D-Day''' (after ]), it is the largest seaborne invasion in history. The operation began the ], and the rest of Western Europe, and laid the foundations of the Allied victory on the ]. | |||

| The assault was conducted in two phases: an ] landing of American, British and Canadian ] shortly after midnight, and an ] of Allied infantry and armoured ] on the coast of France commencing at 6:30. There were also subsidiary 'attacks' mounted under the codenames ] and ] to distract the German forces from the real landing areas.<ref>{{cite book | last = Hakim | first = Joy | title = A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz | publisher = ] | year = 1995 | location = New York | pages =157–161 | isbn = 0-19-509514-6 }}</ref>''' | |||

| Planning for the operation began in 1943. In the months leading up to the invasion, the Allies conducted a substantial ], codenamed ], to mislead the Germans as to the date and location of the main Allied landings. The weather on the day selected for D-Day was not ideal, and the operation had to be delayed 24 hours; a further postponement would have meant a delay of at least two weeks, as the planners had requirements for the phase of the moon, the tides, and time of day, that meant only a few days each month were deemed suitable. ] placed ] ] in command of German forces and developing fortifications along the ] in anticipation of an invasion. US President ] placed Major General ] in command of Allied forces. | |||

| The operation was the largest single-day amphibious invasion of all time, with 160,000<ref name="USMil">{{cite web|title=D-Day June 6, 1944| work=www.army.mil US Army Official website| url=http://www.army.mil/d-day/| accessdate=2009-05-14}}</ref> troops landing on 6 June 1944. 195,700<ref>{{cite book | last = Ambrose | first = Stephen E. | author-link = Stephen Ambrose | title = D-Day | location = New York | publisher = Simon & Schuster | year = 1994 | isbn = 0-684-80137-X}}</ref> Allied naval and ] personnel in over 5,000<ref name="USMil"/> ships were involved. The invasion required the transport of soldiers and materiel<!--DO NOT CHANGE spelling — materiel is correct--> from the United Kingdom by troop-laden aircraft and ships, the assault landings, ], naval interdiction of the ] and naval ]. The landings took place along a {{Convert|50|mi|km|adj=on}} stretch of the ] coast divided into five sectors: ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

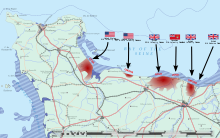

| The invasion began shortly after midnight on the morning of 6 June with extensive aerial and naval bombardment as well as an ]—the ], ]. The early morning aerial assault was soon followed by ] on the coast of France {{circa}}{{nbsp}}06:30. The target {{Convert|50|mi|km|adj=on}} stretch of the Normandy coast was divided into five sectors: ], ], ], ], and ]. Strong winds blew the landing craft east of their intended positions, particularly at Utah and Omaha. | |||

| The men landed under heavy fire from ] overlooking the beaches, and the shore was ] and covered with obstacles such as wooden stakes, ], and barbed wire, making the work of the beach-clearing teams difficult and dangerous. The highest number of casualties was at Omaha, with its high cliffs. At Gold, Juno, and Sword, several fortified towns were cleared in ], and two major gun emplacements at Gold were disabled using specialised tanks. | |||

| The Allies were able to establish ]s at each of the five landing sites on the first day, but ], ], and ] remained in German hands. ], a major objective, was not captured until 21 July. Only two of the beaches (Juno and Gold) were linked on the first day, and all five beachheads were not connected until 12 June. German casualties on D-Day have been estimated at 4,000 to 9,000 men. Allied casualties were at least 10,000, with 4,414 confirmed dead. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| After the ] ] in June 1941, the ] leader ] began pressing his new allies for the creation of a ] in western Europe.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=8–9}} In late May 1942, the ] and the ] made a joint announcement that a "... full understanding was reached with regard to the urgent tasks of creating a second front in Europe in 1942."{{sfn|Folliard|1942}} However, British Prime Minister ] persuaded US President ] to postpone the promised invasion as, even with US help, the Allies did not have adequate forces for such an activity.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=10}} | |||

| Instead of an immediate return to France, the western Allies staged offensives in the ], where ] were already stationed. By mid-1943, the ] had been won. The Allies then launched the ] in July 1943 and subsequently ] in September the same year. By then, Soviet forces were on the offensive and had won a major victory at the ]. The decision to undertake a cross-channel invasion within the next year was taken at the ] in Washington in May 1943.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=10–11}} Initial planning was constrained by the number of available landing craft, most of which were already committed in the Mediterranean and ].{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|pp=177–178, chart p. 180}} At the ] in November 1943, Roosevelt and Churchill promised Stalin that they would open the long-delayed second front in May 1944.{{sfn|Churchill|1951|p=404}} | |||

| ] (SHAEF), 1 February 1944. Front row: ] ]; ] ]; ] ]. Back row: ] ]; ] ]; Air Chief Marshal ]; Lieutenant General ].]] | |||

| The Allies considered four sites for the landings: ], the ], Normandy, and the ]. As Brittany and Cotentin are peninsulas, it would have been possible for the Germans to cut off the Allied advance at a relatively narrow isthmus, so these sites were rejected.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=13–14}} With the Pas-de-Calais being the closest point in ] to Britain, the Germans considered it to be the most likely initial landing zone, so it was the most heavily fortified region.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=33–34}} But it offered few opportunities for expansion, as the area is bounded by numerous rivers and canals,{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=170}} whereas, landings on a broad front in Normandy would permit simultaneous threats against the port of ], coastal ports further west in Brittany, and an overland attack towards ] and eventually into Germany. Normandy was hence chosen as the landing site.{{sfn|Ambrose|1994|pp=73–74}} The most serious drawback of the Normandy coast—the lack of port facilities—would be overcome through the development of artificial ]s.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=14}} A series of modified tanks, nicknamed ], dealt with specific requirements expected for the Normandy Campaign such as mine clearing, demolishing bunkers, and mobile bridging.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=182}} | |||

| The Allies planned to launch the invasion on 1 May 1944.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=170}} The initial draft of the plan was accepted at the ] in August 1943. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was appointed commander of the ].{{sfn|Gilbert|1989|p=491}} General ] was named commander of the ], which comprised all land forces involved in the invasion.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|pp=12–13}} On 31 December 1943, Eisenhower and Montgomery first saw the plan, which proposed amphibious landings by three divisions with two more divisions in support. The two generals insisted that the scale of the initial invasion be expanded to five divisions, with airborne descents by three additional divisions, to allow operations on a wider front and to hasten the capture of Cherbourg.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=13}} The need to acquire or produce extra landing craft for the expanded operation meant that the invasion had to be delayed to June.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=13}} Eventually, thirty-nine Allied divisions would be committed to the Battle of Normandy: twenty-two American, twelve British, three Canadian, one Polish, and one French, totalling over a million troops.{{sfn|Weinberg|1995|p=684}} | |||

| ==Operations== | ==Operations== | ||

| ] was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale ] on the continent. The first phase, the amphibious invasion and establishment of a secure foothold, was codenamed Operation Neptune.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=14}} To gain the air superiority needed to ensure a successful invasion, the Allies undertook a bombing campaign (codenamed ]) that targeted German aircraft production, fuel supplies, and airfields.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=14}} Elaborate deceptions, codenamed ], were undertaken in the months leading up to the invasion to prevent the Germans from learning the timing and location of the invasion.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=3}} | |||

| The Allied invasion was detailed in several overlapping operational plans according to the D-Day museum: | |||

| The landings were to be preceded by airborne operations near Caen on the eastern flank to secure the ] bridges and north of Carentan on the western flank. The Americans, assigned to land at Utah Beach and Omaha Beach, were to attempt to capture Carentan and Saint-Lô the first day, then cut off the Cotentin Peninsula and eventually capture the port facilities at ]. The British at ] and ]es and the Canadians at ] would protect the US flank and attempt to establish airfields near Caen on the first day.{{sfn|Churchill|1951|pp=592–593}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|loc=Map, inside front cover}} (A sixth beach, code-named "Band", was considered to the east of the Orne).{{sfn|Caddick-Adams|2019|p=136}} A secure lodgement would be established with all invading forces linked together, with an attempt to hold all territory north of the ]-] line within the first three weeks.{{sfn|Churchill|1951|pp=592–593}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|loc=Map, inside front cover}} Montgomery envisaged a ninety-day battle, lasting until all Allied forces reached the River ].{{sfn|Weinberg|1995|p=698}} | |||

| ==Deception plans== | |||

| {{See also|D-Day naval deceptions}} | |||

| ] under ]. ]] | |||

| Under the overall umbrella of Operation Bodyguard, the Allies conducted several subsidiary operations designed to mislead the Germans as to the date and location of the Allied landings.{{sfn|Weinberg|1995|p=680}} ] included Fortitude North, a misinformation campaign using fake radio traffic to lead the Germans into expecting an attack on Norway,{{sfn|Brown|2007|p=465}} and Fortitude South, a major deception involving the creation of a fictitious ] under Lieutenant General ], supposedly located in ] and ]. Fortitude South was intended to deceive the Germans into believing that the main attack would take place at ].{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=3}}{{sfn|Zuehlke|2004|pp=71–72}} Genuine radio messages from 21st Army Group were first routed to Kent via landline and then broadcast, to give the Germans the impression that most of the Allied troops were stationed there.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=27}} Patton was stationed in England until 6 July, thus continuing to deceive the Germans into believing a second attack would take place at Calais.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=282}} | |||

| Many of the German radar stations on the French coast were destroyed in preparation for the landings.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=34}} In addition, on the night before the invasion, a small group of ] operators deployed dummy paratroopers over ] and ]. These dummies led the Germans to believe that an additional airborne landing had occurred. On that same night, in ], ] dropped strips of "window", ] that caused a radar return which was mistakenly interpreted by German radar operators as a naval convoy near Le Havre. The illusion was bolstered by a group of small vessels towing ]s. A similar deception was undertaken near ] in the Pas de Calais area by ] in ].{{sfn|Bickers|1994|pp=19–21}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=76}} | |||

| :"The armed forces use codenames to refer to the planning and execution of specific military operations. Operation Overlord was the codename for the Allied invasion of northwest Europe. The assault phase of Operation Overlord was known as Operation Neptune. Operation Neptune began on D-Day ( 6 June 1944) and ended on 30 June 1944. By this time, the Allies had established a firm foothold in Normandy. Operation Overlord also began on D-Day, and continued until Allied forces crossed the River Seine on 19 August."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ddaymuseum.co.uk/faq.htm#overlord |title=Frequently Asked Questions for D-Day and the Battle of Normandy |publisher=Ddaymuseum.co.uk |date= |accessdate=2009-06-06}}</ref> | |||

| ==Weather== | ==Weather== | ||

| {{Main|Weather forecasting for Operation Overlord}} | |||

| Only a few days in each month were suitable for launching the operation, because both a ] and a ] were required: the former to illuminate navigational landmarks for the crews of aircraft, gliders and landing craft, and the latter to provide the deepest possible water to help safe navigation over defensive obstacles placed by the Germans in the surf on the seaward approaches to the beaches. ] ] had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault. Most of May had fine weather, but this deteriorated in early June. On 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing; wind and high seas would make it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft finding their targets. The Allied troop convoys already at sea were forced to take shelter in bays and inlets on the south coast of Britain for the night. | |||

| The invasion planners determined a set of conditions involving the phase of the moon, the tides, and the time of day that would be satisfactory on only a few days in each month. A full moon was desirable, as it would provide illumination for aircraft pilots and have the ]. The Allies wanted to schedule the landings for shortly before dawn, midway between low and high tide, with the tide coming in. This would improve the visibility of obstacles on the beach while minimising the amount of time the men would be exposed in the open.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=31}} Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault. However, on 4 June, conditions were unsuitable for a landing: high winds and heavy seas made it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft from finding their targets.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=33}} The weather forecast that reported the storms was sent from a weather station on the western coast of Ireland.{{sfn|Traub|2024}} | |||

| ] map showing ]s on 5 June]] | |||

| It seemed possible that everything would have to be cancelled and the troops returned to their camps (a vast undertaking because the enormous movement of follow-up formations was already proceeding). The next full moon period would be nearly a month away. At a vital meeting on 5 June, Eisenhower's chief meteorologist (] ]) forecast a brief improvement for 6 June. General ] and Eisenhower's Chief of Staff General ] wished to proceed with the invasion. ] was doubtful, but ] ] believed that conditions would be marginally favorable. On the strength of Stagg's forecast, Eisenhower ordered the invasion to proceed. | |||

| Group Captain ] of the ] (RAF) met Eisenhower on the evening of 4{{nbsp}}June. He and his meteorological team predicted that the weather would improve enough for the invasion to proceed on 6 June.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=21}} The next available dates with the required tidal conditions (but without the desirable full moon) would be two weeks later, from 18 to 20 June. Postponement of the invasion would have required recalling men and ships already in position to cross the ] and would have increased the chance that the invasion plans would be detected.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=224}} After much discussion with the other senior commanders, Eisenhower decided that the invasion should go ahead on 6 June.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|pp=224–226}} A major storm battered the Normandy coast from 19 to 22 June, which would have made the beach landings impossible.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=33}} | |||

| The Germans meanwhile took comfort from the existing poor conditions, which were worse over Northern France than over the and battalion commanders were away from their posts at war games. | |||

| Allied control of the Atlantic meant German meteorologists had less information than the Allies on incoming weather patterns.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=34}} As the '']'' meteorological centre in Paris was predicting two weeks of stormy weather, many Wehrmacht commanders left their posts to attend ] in ], and men in many units were given leave.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=131}} Field Marshal ] returned to Germany for his wife's birthday and to petition Hitler for additional ] divisions.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=42–43}} | |||

| ==Allied Order of Battle== | |||

| ] | |||

| The order of battle for the landings was approximately as follows, east to west: | |||

| == |

==German order of battle== | ||

| Germany had at its disposal fifty divisions in France and the ], with another eighteen stationed in Denmark and Norway. Fifteen divisions were in the process of formation in Germany.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=144}} Combat losses throughout the war, particularly on the ], meant that the Germans no longer had a pool of able young men from which to draw. German soldiers were now on average six years older than their Allied counterparts. Many in the Normandy area were '']'' (eastern legions)—conscripts and volunteers from Russia, Mongolia, and other areas of the Soviet Union. They were provided mainly with unreliable captured equipment and lacked motorised transport.{{sfn|Francois|2013|p=118}}{{sfn|Goldstein|Dillon|Wenger|1994|pp=16–19}} Many German units were under strength.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=37}} | |||

| * ] was delivered by ] and ] to the east of the ] to protect the left flank. The division contained 7,900 men, including one Canadian battalion.<ref name="DDayFAQ">{{cite web|title=Britannica guide to D-Day 1944|url=http://www.britannica.com/dday/article-236192|authorlink=John Keegan|accessdate=2007-10-30}} Also ''Keegan, John:The Second World War''{{Page number}}.</ref>{{Page number}} | |||

| * ] comprising No. 3, No. 4, No. 6 and ] ] landed at ] in ''Queen Red'' sector (leftmost). No.4 Commando were augmented by 1 and 8 Troop (both French) of No. 10 (Inter Allied) Commando. | |||

| * ], ] and the ] on ''']''', from Ouistreham to ]. | |||

| * ] (part of ]) landed on the far West of Sword Beach.<ref>{{cite web|title=Britannica guide to D-Day 1944|url=http://www.britannica.com/dday/article-236192|authorlink=John Keegan|accessdate=2007-10-30}}</ref> | |||

| * ], ] and ] on ''']''', from ] to ].<ref name="DDayFAQ"/> | |||

| * ] (part of 4th Special Service Brigade) at ''Juno'' to scale the cliffs on the left side of the Orne River estuary and destroy a battery. (Battery fire proved negligible so No.46 were kept off-shore as a floating reserve and landed on D+1). | |||

| * ], ] and ], consisting of 25,000 men landing on ''']''',<ref>{{cite web|title=Britannica guide to D-Day 1944|url=http://www.britannica.com/dday/article-9389939|authorlink=John Keegan|accessdate=2007-10-30}}</ref> from Courseulles to ]. | |||

| * ] (part of 4th Special Service Brigade) on the West flank of Gold beach. | |||

| * ] operated specialist armour ("]") for mine-clearing, recovery and assault tasks. These were distributed around the Anglo-Canadian beaches. | |||

| * 4th ] ] Battalion from the British SAS Brigade, by parachute in ]. | |||

| In early 1944, the German Western Front (]) was significantly weakened by personnel and materiel transfers to the Eastern Front. During the Soviet ] (24 December 1943 – 17 April 1944), the ] was forced to transfer the entire ] from France, consisting of the ] and ] SS Panzer Divisions, as well as the ], 507th Heavy Panzer Battalion and the 311th and 322nd StuG Assault Gun Brigades. All told, the German forces stationed in France were deprived of 45,827 troops and 363 tanks, assault guns, and self-propelled anti-tank guns.{{sfn|Liedtke|2015|pp=227–228, 235}} | |||

| Overall, the 2nd Army contingent consisted of 83,115 troops (61,715 of them British).<ref name="DDayFAQ">{{cite web|url=http://www.ddaymuseum.co.uk/faq.htm|title=D-Day FAQ|accessdate=2007-10-30}}</ref> In addition to the British and Canadian combat units, two troops of No. 10 Commando were employed, manned by Frenchmen, and eight Australian officers were attached to the British forces as observers.<ref>''Vet Affairs'', 21(1), March 2005. </ref> The nominally British air and naval support units included a large number of crew from Allied nations, including several RAF squadrons manned almost exclusively by foreign flight crew. | |||

| The ], ], ], ] and ] Panzer divisions, alongside the ], had only arrived in France in March–May 1944 for extensive refit after being badly damaged during the Dnieper-Carpathian operation. Seven of the eleven panzer or {{Lang|de|panzergrenadier|italic=no}} divisions stationed in France were not fully operational or only partially mobile in early June 1944.{{sfn|Liedtke|2015|pp=224–225}} | |||

| ===U.S. First Army=== | |||

| * ], ] and ] making up 34,250 troops for ''']''', from ] to ].<ref name="DDayFAQ"/><ref name="TOCTWW2c">Map 81, {{cite encyclopedia|editor=M.R.D. Foot, I.C.B. Dear|encyclopedia=The Oxford Companion to World War II|pages=663|isbn=9-780192-806666|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2005|accessdate=2007-11-15}}</ref> | |||

| * 2nd and 5th ] Battalions at ] (The 5th diverted to Omaha).<ref name="TOCTWW2c"/> | |||

| * ], ] and the 359th ] of the ] comprising of 23,250 men landing on ''']''', around Pouppeville and ].<ref name="TOCTWW2c"/> | |||

| * ] by parachute around ] to support Utah Beach landings.<ref name="TOCTWW2c"/> | |||

| * ] by parachute around ], protecting the right flank. They had originally been tasked with dropping further west, in the middle part of the ], allowing the sea-landing forces to their east easier access across the peninsula, and preventing the Germans from reinforcing the north part of the peninsula. The plans were later changed to move them much closer to the beachhead, as at the last minute the ] was determined to be in the area.<ref name="TOCTWW2c"/><ref name="johnhbradley1">{{cite book|title=The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean| url=http://books.google.com/books?id=HP3-9NNz71sC&pg=PA290&lpg=PA290&ots=lzKtqLPDHv&output=html&sig=kOpC3DroIRJa_SduUsfycSA2vHo|last=Bradley|first=John H.|publisher=Square One Publishers|page=290|year=2002|isbn=0757001629|accessdate=2007-11-16}}</ref> | |||

| German Supreme commander: ] | |||

| In total, the First Army contingent totalled approximately 73,000 men, including 15,500 from the airborne divisions.<ref name="DDayFAQ"/> | |||

| * ''Oberbefehlshaber'' West (Supreme Commander West; ]): Field Marshal ] | |||

| ::* (]: General ]) | |||

| :* ]: Field Marshal Erwin Rommel | |||

| :** ]: '']'' ] | |||

| :*** LXXXIV Corps under '']'' ] | |||

| ===Cotentin Peninsula=== | |||

| ==German Order of Battle== | |||

| Allied forces attacking Utah Beach faced the following German units stationed on the Cotentin Peninsula: | |||

| The number of military forces at the disposal of Nazi Germany reached its peak during 1944. By D-Day, 157 German divisions were stationed in the Soviet Union, 6 in Finland, 12 in Norway, 6 in Denmark, 9 in Germany, 21 in the Balkans, 26 in Italy and 59 in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Struggle for Europe|last=Wilmot|first=Chester|year=1952|isbn=1853266779}}</ref> However, these statistics are somewhat misleading since a significant number of the divisions in the east were depleted due to intensity of fighting; German records indicate that the average personnel complement was at about 50% in the spring of 1944.<ref>Tippelskirch, Kurt von, Geschichte des Zweiten Weltkriegs. 1956</ref> | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] ] | |||

| **under ''Generalleutnant'' ] numbered 12,320 men, many of them '']'' (non-German conscripts recruited from Soviet prisoners of war).{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=118}} | |||

| ** 729th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=122}} | |||

| ** 739th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=122}} | |||

| ** 919th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=122}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| === |

===Grandcamps Sector=== | ||

| Americans assaulting Omaha Beach faced the following troops: | |||

| The German defenses used an interlocking firing style, so they could protect areas that were receiving heavy fire. They had large bunkers, sometimes intricate concrete ones containing machine guns and high caliber weapons. Their defense also integrated the cliffs and hills overlooking the beautiful view. The defenses were all built and honed over a four year period. | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] ] | |||

| **under ''Generalleutnant'' ], a full-strength unit of around 12,000 brought in by Rommel on 15 March and reinforced by two additional regiments.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=60, 63}} | |||

| ** 914th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=63}} | |||

| ** 915th Grenadier Regiment (as reserves){{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=63}} | |||

| ** 916th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=63}} | |||

| ** 726th Infantry Regiment (from 716th Infantry Division){{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=63}} | |||

| ** 352nd Artillery Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=63}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| Allied forces at Gold and Juno faced the following elements of the 352nd Infantry Division: | |||

| ===Atlantic Wall=== | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| {{main|Atlantic Wall|English Channel}} | |||

| ** 914th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| ], shown in green. {{legend|#527AC3|German Reich, allies and occupied zones}}{{legend|#CE6262|Allies}}]] | |||

| ** 915th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| Standing in the way of the Allies was the ], a crossing which had confounded the ] and ]'s Navy. Compounding the invasion efforts was the extensive ], ordered by ] in his Directive 51. Believing that any forthcoming landings would be timed for high tide (this caused the landings to be timed for low tide), Rommel had the entire wall fortified with tank top turrets and extensive barbed wire, and laid a million mines to deter landing craft. The sector which was attacked was guarded by four divisions. | |||

| ** 916th Grenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| ** 352nd Artillery Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| === |

===Forces around Caen=== | ||

| Allied forces attacking Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches faced the following German units: | |||

| * ] defended the Eastern end of the landing zones, including most of the British and Canadian beaches. This division, as well as the 709th, included Germans who were not considered fit for active duty on the ], usually for medical reasons, and soldiers of various other nationalities (from conquered countries, often drafted by force) and former Soviet prisoners-of-war who had agreed to fight for the Germans rather than endure the harsh conditions of German ] camps (among them so called '']''). These "volunteers" were concentrated in "Ost-Bataillone" (East Battalions) that were of dubious loyalty. | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] was a well-trained and equipped formation defending the area between approximately Bayeux and Carentan, including Omaha beach. The division had been formed in November 1943 with the help of cadres from the disbanded 321st Division, which had been destroyed in the Soviet Union that same year. The 352nd had many troops who had seen action on the eastern front and on the 6th, had been carrying out anti-invasion exercises. | |||

| * ] ] | |||

| * ] (''Luftlande''–air transported) (Generalmajor ]), comprising the ] and ]. This was a regular infantry division, trained, and equipped to be transported by air (i.e. transportable artillery, few heavy support weapons) located in the interior of the ], including the drop zones of the ]. The attached ] (Oberstleutnant ]) had been rebuilt as a part of the ] stationed in ]. | |||

| **under ''Generalleutnant'' ]. At 7,000 troops, the division was significantly understrength.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=60}} | |||

| * ] (Generalleutnant ]), comprising the ], ] (both with four battalions, but the 729th 4th and the 739th 1st and 4th being Ost, these two regiments had no regimental support companies either), and ]. This coastal defense division protected the eastern, and northern (including Cherbourg) coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, including the Utah beach landing zone. Like the 716th, this division comprised a number of "Ost" units who were provided with German leadership to manage them. | |||

| ** 736th Infantry Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=206}} | |||

| ** 1716th Artillery Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=206}} | |||

| * ] ], (south of Caen) | |||

| ** under ''Generalmajor'' ] included 146 tanks and 50 ]s, plus supporting infantry and artillery.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=73}} | |||

| ** 100th Panzer Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} (at Falaise under ]; renamed 22nd Panzer Regiment in May 1944 to avoid confusion with 100th Panzer Battalion) {{sfn|Margaritis|2019|pp=414–418}} | |||

| ** 125th Panzergrenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}}(under ] from April 1944){{sfn|Margaritis|2019|p=321}} | |||

| ** 192nd Panzergrenadier Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| ** 155th Panzer Artillery Regiment{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=275}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ==Atlantic Wall== | |||

| ====Adjacent Divisional Areas==== | |||

| {{Main|Atlantic Wall|English Channel}} | |||

| Other divisions occupied the areas around the landing zones, including: | |||

| ], shown in yellow{{legend|#5f5f5f|Axis and occupied countries}}{{legend|#60a667|Allies and occupied countries}}{{legend|#FFFFFF|Neutral countries}}]] | |||

| * ] (Generalleutnant ]), comprising the ] (two battalions), ], and ]. This coastal defense division protected the western coast of the Cotentin Peninsula. | |||

| ]s deployed on the ] near ] ]] | |||

| * ], comprising the ], and ]. This division defended the western part of the ]. | |||

| * ] (Oberstleutnant Freiherr von und zu Aufsess), comprising three ] battalions. | |||

| Alarmed by the raids on ] and ] in 1942, Hitler had ordered the construction of fortifications all along the Atlantic coast, from Spain to Norway, to protect against an expected Allied invasion. He envisioned 15,000 emplacements manned by 300,000 troops, but shortages, particularly of concrete and manpower, meant that most of the strongpoints were never built.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=30}} As it was expected to be the site of the invasion, the Pas de Calais was heavily defended.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=30}} In the Normandy area, the best fortifications were concentrated at the port facilities at Cherbourg and ].{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=13}} Rommel was assigned to oversee the construction of further fortifications along the expected invasion front, which stretched from the Netherlands to Cherbourg,{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=30}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=33}} and was given command of the newly re-formed Army Group B, which included the 7th Army, the ], and the forces guarding the Netherlands. Reserves for this group included the ], 21st, and ] divisions.{{sfn|Goldstein|Dillon|Wenger|1994|p=12}}{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=12}} | |||

| ===Armoured reserves=== | |||

| Rommel's defensive measures were also frustrated by a dispute over armoured doctrine. In addition to his two army groups, von Rundstedt also commanded the headquarters of ''Panzer Group West'' under General ] (usually referred to as ''von Geyr''). This formation was nominally an administrative HQ for von Rundstedt's armoured and mobile formations, but it was later to be renamed ] and brought into the line in Normandy. Von Geyr and Rommel disagreed over the deployment and use of the vital Panzer divisions. | |||

| Rommel believed that the Normandy coast could be a possible landing point for the invasion, so he ordered the construction of extensive defensive works along that shore. In addition to concrete gun emplacements at strategic points along the coast, he ordered wooden stakes, metal tripods, mines, and large anti-tank obstacles to be placed on the beaches to delay the approach of landing craft and impede the movement of tanks.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=54–56}} Expecting the Allies to land at high tide so that the infantry would spend less time exposed on the beach, he ordered many of these obstacles to be placed at the ].{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=31}} Tangles of barbed wire, ]s, and the removal of ground cover made the approach hazardous for infantry.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=54–56}} On Rommel's order, the number of mines along the coast was tripled.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=13}} The Allied ] had crippled the ''Luftwaffe'' and established ] over western Europe, so Rommel knew he could not expect effective air support.{{sfn|Murray|1983|p=263}} The ''Luftwaffe'' could muster only 815 aircraft{{sfn|Murray|1983|p=280}} over Normandy in comparison to the Allies' 9,543.{{sfn|Hooton|1999|p=283}} Rommel arranged for booby-trapped stakes known as ''Rommelspargel'' (]) to be installed in meadows and fields to deter airborne landings.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=13}} | |||

| Rommel recognised that the Allies would possess air superiority and would be able to harass his movements from the air. He therefore proposed that the armoured formations be deployed close to the invasion beaches. In his words, it was better to have one Panzer division facing the invaders on the first day, than three Panzer divisions three days later when the Allies would already have established a firm beachhead. Von Geyr argued for the standard doctrine that the Panzer formations should be concentrated in a central position around Paris and Rouen, and deployed ''en masse'' against the main Allied beachhead when this had been identified. | |||

| German armaments minister ] notes in his 1969 autobiography that the German high command, concerned about the susceptibility of the airports and port facilities along the North Sea coast, held a conference on 6–8 June 1944 to discuss reinforcing defences in that area.{{sfn|Speer|1971|pp=483–484}} Speer wrote: | |||

| The argument was eventually brought before Hitler for arbitration. He characteristically imposed an unworkable compromise solution. Only three Panzer divisions were given to Rommel, too few to cover all the threatened sectors. The remainder, nominally under Von Geyr's control, were actually designated as being in "] Reserve". Only three of these were deployed close enough to intervene immediately against any invasion of Northern France, the other four were dispersed in southern France and the Netherlands. Hitler reserved to himself the authority to move the divisions in OKW Reserve, or commit them to action. On 6 June, many Panzer division commanders were unable to move because Hitler had not given the necessary authorization, and his staff refused to wake him upon news of the invasion. | |||

| * The ] (Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger) was deployed near ] as a mobile striking force as part of the ] reserve. However, Rommel placed it so close to the coastal defenses that, under ]s in case of invasion, several of its infantry and anti-aircraft units would come under the orders of the fortress divisions on the coast, reducing the effective strength of the division. | |||

| {{blockquote|In Germany itself we scarcely had any troop units at our disposal. If the airports at Hamburg and Bremen could be taken by parachute units and the ports of these cities seized by small forces, invasion armies debarking from ships would, I feared, meet no resistance and would be occupying Berlin and all of Germany within a few days.{{sfn|Speer|1971|p=482}} }} | |||

| The other mechanized divisions capable of intervening in Normandy were retained under the direct control of the German Armed Forces HQ (]) and were initially denied to Rommel. | |||

| ==Armoured reserves== | |||

| Rommel believed that Germany's best chance was to stop the invasion at the shore. He requested that the mobile reserves, especially tanks, be stationed as close to the coast as possible. Rundstedt, Geyr, and other senior commanders objected. They believed that the invasion could not be stopped on the beaches. Geyr argued for a conventional doctrine: keeping the Panzer formations concentrated in a central position around Paris and Rouen and deploying them only when the main Allied beachhead had been identified. He also noted that in the ], the armoured units stationed near the coast had been damaged by naval bombardment. Rommel's opinion was that because of Allied air supremacy, the large-scale movement of tanks would not be possible once the invasion was under way. Hitler made the final decision, which was to leave three ] under Geyr's command and give Rommel operational control of three more as reserves. Hitler took personal control of four divisions as strategic reserves, not to be used without his direct orders.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=31}}{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=15}}{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=192}} | |||

| ==Allied order of battle== | |||

| {{see also|List of Allied forces in the Normandy campaign}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Commander, SHAEF: General Dwight D. Eisenhower<br /> | |||

| Commander, 21st Army Group: General Bernard Montgomery{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|loc=Map, p. 12}} | |||

| ===US zones=== | |||

| Commander, ]: Lieutenant General ]{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|loc=Map, p. 12}} | |||

| The First Army contingent totalled approximately 73,000 men, including 15,600 from the airborne divisions.{{sfn|Portsmouth Museum Services}} | |||

| ;Utah Beach | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] ], commanded by Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=125}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=125}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=125}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Brigadier General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=125}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=125}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ;Omaha Beach | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] ], commanded by Major General ], making up 34,250 men{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=53}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=66}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=66}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ===British and Canadian zones=== | |||

| ] attached to ] move inland from ], 6 June 1944. An armoured bridgelayer tank is in the background]] | |||

| Commander, ]: Lieutenant General Sir ]{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|loc=Map, p. 12}} | |||

| Overall, the Second Army contingent consisted of 83,115 men, 61,715 of them British.{{sfn|Portsmouth Museum Services}} The British and Commonwealth air and naval support units included a large number of personnel from Allied nations, including several RAF squadrons manned almost exclusively by overseas air crew. For example, the ] to the operation included a regular ] (RAAF) squadron, nine ], and hundreds of personnel posted to RAF units and RN warships.{{sfn|Stanley|2004}} The RAF supplied two-thirds of the aircraft involved in the invasion.{{sfn|Holland|2014}} | |||

| ;Gold Beach | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] ], commanded by Lieutenant General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=271}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=271}} | |||

| ** reinforced with | |||

| *** ] ] | |||

| *** ] ] | |||

| *** ] | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ;Juno Beach | |||

| {{main|Juno Beach order of battle}} | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] British ], commanded by Lieutenant General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=270}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=270}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ;Sword Beach | |||

| {{tree list}} | |||

| * ] British I Corps, commanded by Lieutenant General John Crocker{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=200}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=200}} | |||

| ** ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=200}} | |||

| {{tree list/end}} | |||

| ] ]: Major General ]{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=201}} provided specialised armoured vehicles which supported the landings on all beaches in Second Army's sector. | |||

| ==Coordination with the French Resistance== | ==Coordination with the French Resistance== | ||

| ] and the US 82nd Airborne division during the ] in 1944.]] | |||

| The various factions and circuits of the ] were included in the plan for ''Overlord''. Through a London-based headquarters which supposedly embraced all resistance groups, État-major des ] (EMFFI), the British ] orchestrated a massive campaign of ] tasking the various Groups with attacking ] lines, ambushing roads, or destroying ]s or ]s. The resistance was alerted to carry out these tasks by means of the ''messages personnels'', transmitted by the ] in its French service from London. Several hundred of these were regularly transmitted, ] the few of them that were really significant. | |||

| Through the London-based ''État-major des Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur'' (]), the British ] orchestrated a campaign of ] to be implemented by the ]. The Allies developed four plans for the Resistance to execute on D-Day and the following days: | |||

| Among the stream of apparently meaningless messages broadcast by the BBC at 21:00 CET on 5 June, were coded instructions such as ''Les carottes sont cuites'' ("The carrots are cooked") and ''Les dés sont jetés'' ("The dice have been thrown").<ref>La Seconde Guerre Mondiale–Hors-série Images Doc ISSN 0995-1121–June 2004</ref> | |||

| * Plan ''Vert'' was a 15-day operation to sabotage the rail system. | |||

| One famous pair of these messages is often mistakenly stated to be a general call to arms by the Resistance. A few days before D-Day, the (slightly misquoted) first line of ] poem, ''Chanson d'Automne'', was transmitted. ''"Les sanglots longs des violons de l'automne"''<ref>Verlaine originally wrote, "'''''Blessent''''' ''mon coeur''" (wound my heart). The BBC replaced Verlaine's original words with the slightly modified lyrics of a song entitled ''Verlaine (Chanson d'Automne)'' by ].</ref><ref name="Foot143">M.R.D. Foot, ''SOE'', BBC Publications 1984, ISBN 0-563-20193-2. p. 143.</ref> (''Long sobs of autumn violins'') alerted the resistance of the ] network in the ] region to attack rail targets within the next few days. The second line, ''"Bercent mon coeur d'une langueur monotone"'' ("soothe my heart with a monotonous languor"), transmitted late on 5 June, meant that the attack was to be mounted immediately. | |||

| * Plan ''Bleu'' dealt with destroying electrical facilities. | |||

| * Plan ''Tortue'' was a delaying operation aimed at the enemy forces that would potentially reinforce Axis forces at Normandy. | |||

| * Plan ''Violet'' dealt with cutting underground telephone and teleprinter cables.{{sfn|Douthit|1988|p=23}} | |||

| The resistance was alerted to carry out these tasks by ''messages personnels'' transmitted by the ] from London. Several hundred of these messages, which might be snippets of poetry, quotations from literature, or random sentences, were regularly transmitted, ] the few that were actually significant. In the weeks preceding the landings, lists of messages and their meanings were distributed to resistance groups.{{sfn|Escott|2010|p=138}} An increase in radio activity on 5 June was correctly interpreted by German intelligence to mean that an invasion was imminent or underway. However, because of the barrage of previous false warnings and misinformation, most units ignored the warning.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=43}}{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=229}} | |||

| Josef Götz, the head of the signals section of the German intelligence service (the ]) in Paris, had discovered the meaning of the second line of Verlaine's poem, and no fewer than fourteen other executive orders they heard late on 5 June. His section rightly interpreted them to mean that invasion was imminent or underway, and they alerted their superiors and all Army commanders in France. However, they had issued a similar warning a month before, when the Allies had begun invasion preparations and alerted the Resistance, but then stood down because of a forecast of bad weather. The SD having given this false alarm, their genuine alarm was ignored or treated as merely routine. Fifteenth Army HQ passed the information on to its units; Seventh Army ignored it.<ref name="Foot143"/> | |||

| A 1965 report from the Counter-insurgency Information Analysis Center details the results of the French Resistance's sabotage efforts: "In the southeast, 52 locomotives were destroyed on 6 June and the railway line cut in more than 500 places. Normandy was isolated as of 7 June."{{sfn|Special Operations Research Office|1965|pp=51–52}} | |||

| In addition to the tasks given to the Resistance as part of the invasion effort, the Special Operations Executive planned to reinforce the Resistance with three-man liaison parties, under ]. The ''Jedburgh'' parties would coordinate and arrange supply drops to the ] groups in the German rear areas. Also operating far behind German lines and frequently working closely with the Resistance, although not under SOE, were larger parties from the British, French and Belgian units of the ] brigade. | |||

| ==Naval activity== | ==Naval activity== | ||

| {{Main|List of Allied warships in the Normandy landings}} | |||

| ] crosses the ] on 6 June 1944.]] | |||

| The Invasion Fleet was drawn from 8 different navies, comprising 6,939 vessels: 1,213 warships, 4,126 transport vessels (landing ships and ]), and 736 ancillary craft and 864 merchant vessels.<ref name="DDayFAQ"/> | |||

| ] near ]]] | |||

| The overall commander of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, providing close protection and bombardment at the beaches, was Admiral Sir ] who had been responsible for the planning of the ] in 1942 and one of the two fleets carrying troops for the ] in the following year. The Allied Naval Expeditionary Force was divided into two Naval Task Forces: Western (Rear-Admiral ]) and Eastern (Rear-Admiral Sir ] – another veteran of the Italian landings). | |||

| ] crosses the ] on 6 June 1944]] | |||

| Naval operations for the invasion were described by historian ] as a "never surpassed masterpiece of planning".{{sfn|Yung|2006|p=133}} In overall command was British Admiral Sir ], who had served as ] at ] during the ] four years earlier. He had also been responsible for the naval planning of the ] in 1942, and one of the two fleets carrying troops for the ] the following year.{{sfn|Goldstein|Dillon|Wenger|1994|p=6}} | |||

| The invasion fleet, which was drawn from eight different navies, comprised 6,939 vessels: 1,213 warships, 4,126 landing craft of various types, 736 ancillary craft, and 864 merchant vessels.{{sfn|Portsmouth Museum Services}} The majority of the fleet was supplied by the UK, which provided 892 warships and 3,261 landing craft.{{sfn|Holland|2014}} In total there were 195,700 naval personnel involved; of these 112,824 were from the Royal Navy with another 25,000 from the ]; 52,889 were American; and 4,998 sailors from other allied countries.{{sfn|Portsmouth Museum Services}}{{sfn|Morison|1962|p=67}} The invasion fleet was split into the ] (under Admiral ]) supporting the US sectors and the Eastern Naval Task Force (under Admiral Sir ]) in the British and Canadian sectors.{{sfn|Churchill|1951|p=594}}{{sfn|Goldstein|Dillon|Wenger|1994|p=6}} Available to the fleet were five battleships, 20 cruisers, 65 destroyers, and two monitors.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=30}} German ships in the area on D-Day included three torpedo boats, 29 ], 36 ]s, and 35 auxiliary ]s and patrol boats.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=205}} The Germans also had several ]s available, and all the approaches had been heavily mined.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=31}} | |||

| The warships provided cover for the transports against the enemy whether in the form of surface warships, submarines or as an aerial attack and gave support to the landings through shore bombardment. These ships included the Allied Task Force "O". A small part of the naval operation was ], when British ] supplied navigation beacons to guide landing craft. | |||

| ===Naval |

===Naval losses=== | ||

| At 05:10, German ] reached the Eastern Task Force and launched fifteen torpedoes, sinking the Norwegian destroyer {{HNoMS|Svenner|G03|6}} off Sword Beach but missing the British battleships {{HMS|Warspite|03|6}} and {{HMS|Ramillies|07|2}}. After attacking, the German vessels turned away and fled east into a ] that had been laid by the RAF to shield the fleet from the long-range battery at Le Havre.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=233}} Allied losses to mines included the American destroyer {{USS|Corry|DD-463|6}} off Utah and ] {{USS|PC-1261}}, a 173-foot patrol craft.{{sfn|Weigley|1981|pp=136–137}} | |||

| An important part of ''Neptune'' was the isolation of the invasion routes and beaches from any intervention by the German Navy – the ]. The responsibility for this was assigned to the ]'s ]. There were two principal perceived German naval threats. The first was surface attack by German capital ships from anchorages in Scandinavia and the ]. This did not materialise since, by mid-1944, the battleships were damaged, the cruisers were used for training and the Kriegsmarine's fuel allocation had been cut by a third. The inactivity may also have resulted from ] disillusion with the Kriegsmarine.{{Fact|date=February 2009}} In any case, the Royal Navy had strong forces available to repel any attempts, and the ] area was mined (Operation ''Bravado'')<ref>{{dead link|date=June 2009}}</ref> as a precaution. | |||

| ==Bombardment== | |||

| The second perceived major threat was that of ] transferred from the Atlantic. Air surveillance from three ] and ] maintained a cordon well west of ]. Few U-boats were spotted, and most of the escort groups were moved nearer to the landings. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] began around midnight with more than 2,200 British, Canadian, and US bombers attacking targets along the coast and further inland.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=31}} The coastal bombing attack was largely ineffective at Omaha, because low cloud cover made the assigned targets difficult to see. Concerned about inflicting casualties on their own troops, many bombers delayed their attacks too long and failed to hit the beach defences.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=255}} The Germans had 570 aircraft stationed in Normandy and the Low Countries on D-Day, and another 964 in Germany.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|p=31}} | |||

| Minesweepers began clearing channels for the invasion fleet shortly after midnight and finished just after dawn without encountering the enemy.{{sfn|Goldstein|Dillon|Wenger|1994|p=82}} The Western Task Force included the battleships {{USS|Arkansas|BB-33|2}}, {{USS|Nevada|BB-36|2}}, and {{USS|Texas|BB-35|2}}, plus eight cruisers, twenty-eight destroyers, and one monitor.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=81, 117}} The Eastern Task Force included the battleships {{HMS|Ramillies|07|2}} and {{HMS|Warspite|03|2}} and the monitor {{HMS|Roberts|F40|2}}, twelve cruisers, and thirty-seven destroyers.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=82}} Naval bombardment of areas behind the beach commenced at 05:45, while it was still dark, with the gunners switching to pre-assigned targets on the beach as soon as it was light enough to see, at 05:50.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=69}} Since troops were scheduled to land at Utah and Omaha starting at 06:30 (an hour earlier than the British beaches), these areas received only about 40 minutes of naval bombardment before the assault troops began to land on the shore.{{sfn|Whitmarsh|2009|pp=51–52, 69}} | |||

| Further efforts were made to seal the ] against German naval forces from ] and the ]. Minefields were laid (]) to force enemy ships away from air protection where they could be attacked by Allied destroyer flotillas. Again, enemy activity was minor, but on 4 July four German ] were either sunk or forced back to ]. | |||

| ==Airborne operations== | |||

| The ] were closed by minefields, naval and air patrols, ], and effective bombing raids on enemy ports. Local German naval forces were small but could be reinforced from the Baltic. Their efforts, however, were concentrated on protecting the ] against expected landings there, and no attempt was made to force the blockade. | |||

| The success of the amphibious landings depended on the establishment of a secure lodgement from which to expand the beachhead to allow the build-up of a well-supplied force capable of breaking out. The amphibious forces were especially vulnerable to strong enemy counter-attacks before the arrival of sufficient forces in the beachhead could be accomplished. To slow or eliminate the enemy's ability to organise and launch counter-attacks during this critical period, ] were used to seize key objectives such as bridges, road crossings, and terrain features, particularly on the eastern and western flanks of the landing areas. The airborne landings some distance behind the beaches were also intended to ease the egress of the amphibious forces off the beaches, and in some cases to neutralise German coastal defence batteries and more quickly expand the area of the beachhead.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=114}}{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=175}} | |||

| The US 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were assigned to objectives west of Utah Beach, where they hoped to capture and control the few narrow causeways through terrain that had been intentionally flooded by the Germans. Reports from Allied intelligence in mid-May of the arrival of the German ] meant the intended drop zones had to be shifted eastward and to the south.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=125, 128–129}} The British 6th Airborne Division, on the eastern flank, was assigned to capture intact the bridges over the ] and River ], destroy five bridges over the ] {{convert|6|mi}} to the east, and destroy the ] overlooking Sword Beach.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=234}} ] paratroopers from the British ] were assigned to objectives in Brittany from 5 June until August in Operations ], ], and ].{{sfn|Corta|1952|p=159}}{{sfn|Corta|1997|pp=65–78}} | |||

| The screening operation destroyed few German ships, but the objective was achieved. There were no U-boat attacks against Allied shipping and few attempts by surface ships. | |||

| ] war correspondent Robert Barr described the scene as paratroopers prepared to board their aircraft: | |||

| ===Bombardment=== | |||

| ] showing the wide variety of vessels deployed.]] | |||

| Warships provided supporting fire for the land forces. During ''Neptune'', it was given a high importance, using ships from battleships to destroyers and landing craft. For example, the Canadians at Juno beach had fire support many times greater than they had had for the ] in 1942. The old battleships ] and '']'' and the monitor ] were used to suppress shore batteries east of the ]; cruisers targeted shore batteries at ] and ]; eleven destroyers for local fire support. In addition, there were modified landing-craft: eight "Landing Craft Gun", each with two 4.7-inch guns; four "Landing Craft Support" with automatic cannon; eight ] (Rocket), each with a single salvo of 1,100 5-inch rockets; eight ] (Hedgerow), each with twenty-four bombs intended to detonate beach mines prematurely. Twenty-four Landing Craft Tank carried ] self-propelled ]s which also fired while they were on the run-in to the beach. Similar arrangements existed at other beaches. | |||

| {{blockquote|Their faces were darkened with cocoa; sheathed knives were strapped to their ankles; tommy guns strapped to their waists; bandoliers and hand grenades, coils of rope, pick handles, spades, rubber dinghies hung around them, and a few personal oddments, like the lad who was taking a newspaper to read on the plane ... There was an easy familiar touch about the way they were getting ready, as though they had done it often before. Well, yes, they had kitted up and climbed aboard often just like this—twenty, thirty, forty times some of them, but it had never been quite like this before. This was the first combat jump for every one of them.{{sfn|Barr|1944}} }} | |||

| Fire support went beyond the suppression of shore defenses overlooking landing beaches and was also used to break up enemy concentrations as the troops moved inland. This was particularly noted in German reports: Field-Marshall ] reported that:{{quote|... The enemy had deployed very strong Naval forces off the shores of the bridgehead. These can be used as quickly mobile, constantly available artillery, at points where they are necessary as defence against our attacks or as support for enemy attacks. During the day their fire is skillfully directed by . . . plane observers, and by advanced ground fire spotters. Because of the high rapid-fire capacity of Naval guns they play an important part in the battle within their range. The movement of tanks by day, in open country, within the range of these naval guns is hardly possible.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | last = von Rundstedt | |||

| | first = Gerd | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = German Commander-in-Chief West, Field Marshal Karl R. Gerd von Rundstedt's Report on the Allied Invasion of Normandy | |||

| | work = | |||

| | publisher = U.S. Department of the Navy — Naval Historical Center | |||

| | date = | |||

| | url = http://www.history.navy.mil/faqs/faq109-5.htm | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | accessdate = 5 May 2009 }}</ref>}} | |||

| ===United States=== | |||

| Just prior to the invasion, General Eisenhower transmitted a now-historic message to all members of the Allied Expeditionary Force. It read, in part, "You are about to embark upon the great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months."<ref>{{cite web| title=The Passing of the Torch. (See quote box on right hand side of the page)| url=http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=45278| work=American Forces Press Service News Articles| accessdate=2009-02-05}}</ref> In his pocket was an unused statement to be read in case the invasion failed.<ref>{{cite web|title=Teaching With Documents: Message Drafted by General Eisenhower in Case the D-Day Invasion Failed and Photographs Taken on D-Day|url=http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/d-day-message/| work=U.S. National Archives}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|American airborne landings in Normandy}} | |||

| ]s on the evening of 6 June 1944]] | |||

| The US airborne landings began with the arrival of ] at 00:15. Navigation was difficult because of a bank of thick cloud, and as a result, only one of the five paratrooper drop zones was accurately marked with radar signals and ]s.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=133}} Paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, numbering over 13,000 men, were delivered by ]s of the ].{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=134}} To avoid flying over the invasion fleet, the planes arrived from the west over the Cotentin Peninsula and exited over Utah Beach.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=27}}{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=133}} | |||

| Paratroops from 101st Airborne were dropped beginning around 01:30, tasked with controlling the causeways behind Utah Beach and destroying road and rail bridges over the ].{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=243}} The C-47s could not fly in a tight formation because of thick cloud cover, and many paratroopers were dropped far from their intended landing zones. Many planes came in so low that they were under fire from both ] and machine-gun fire. Some paratroopers were killed on impact when their parachutes did not have time to open, and others drowned in the flooded fields.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=61–64}} Gathering together into fighting units was made difficult by a shortage of radios and by the ] terrain, with its ]s, stone walls, and marshes.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=166–167}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=116}} Some units did not arrive at their targets until afternoon, by which time several of the causeways had already been cleared by members of the 4th Infantry Division moving up from the beach.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=139}} | |||

| ==The landings== | |||

| ] situation map for 2400 hours, 6 June 1944.]] | |||

| Troops of the 82nd Airborne began arriving around 02:30, with the primary objective of capturing two bridges over the River ] and destroying two bridges over the Douve.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=243}} On the east side of the river, 75 per cent of the paratroopers landed in or near their drop zone, and within two hours they captured the important crossroads at ] (the first town liberated in the invasion){{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=67}} and began working to protect the western flank.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=244}} Because of the failure of the pathfinders to accurately mark their drop zone, the two regiments dropped on the west side of the Merderet were extremely scattered, with only four per cent landing in the target area.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=244}} Many landed in nearby swamps, with much loss of life.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=145}} Paratroopers consolidated into small groups, usually a combination of men of various ranks from different units, and attempted to concentrate on nearby objectives.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=69}} They captured but failed to hold the Merderet River bridge at La Fière, and fighting for the crossing continued for several days.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=149–150}} | |||

| ===Airborne operations=== | |||

| <!-- Image with inadequate rationale removed: ].]] --> | |||

| The success of the amphibious landings depended on the establishment of a secure lodgment from which to expand the beachhead to allow the build up of a well-supplied force capable of breaking out. The amphibious forces were especially vulnerable to strong enemy counterattacks before the build up of sufficient forces in the beachhead could be accomplished. To slow or eliminate the enemy's ability to organize and launch counterattacks during this critical period, ] were used to seize key objectives, such as bridges, road crossings, and terrain features, particularly on the eastern and western flanks of the landing areas. The airborne landings some distance behind the beaches were also intended to ease the egress of the amphibious forces off the beaches, and in some cases to neutralize German coastal defence batteries and more quickly expand the area of the beachhead. The U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were assigned to objectives west of Utah Beach. The British 6th Airborne Division was assigned to similar objectives on the eastern flank. | |||

| 530 ] paratroopers from the British ] Brigade, were assigned to objectives in ] from 5 June to August.<ref>Corta, Henry (1921-1998), a Free French SAS lieutenant veteran, (1952) : ''les bérets rouges'' (red berets).</ref><ref>Corta, Henry, (1997) : ''Qui ose gagne'' (Who dares wins).</ref> (], ]). | |||

| Reinforcements arrived by ] around 04:00 (] and ]), and 21:00 (] and ]), bringing additional troops and heavy equipment. Like the paratroopers, many landed far from their drop zones.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=151}} Even those that landed on target experienced difficulty, with heavy cargo such as ] shifting during landing, crashing through the wooden fuselage, and in some cases crushing personnel on board.{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=71}} | |||

| ====British airborne landings==== | |||

| {{main|Operation Tonga}} | |||

| East of the landing area, the open, flat, ] between the ] and ] Rivers was ideal for counterattacks by German armour. However, the landing area and floodplain were separated by the Orne River, which flowed northeast from ] into the bay of the ]. The only crossing of the Orne River north of Caen was 7 kilometres (4.5 mi) from the coast, near ] and ]. For the Germans, the crossing provided the only route for a ] on the beaches from the east. For the Allies, the crossing also was vital for any attack on Caen from the east. | |||

| After 24 hours, only 2,500 men of the 101st and 2,000 of the 82nd Airborne were under the control of their divisions, approximately a third of the force dropped. This wide dispersal had the effect of confusing the Germans and fragmenting their response.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=167}} The 7th Army received notification of the parachute drops at 01:20, but Rundstedt did not initially believe that a major invasion was underway. The destruction of radar stations along the Normandy coast in the week before the invasion meant that the Germans did not detect the approaching fleet until 02:00.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=246–247}} | |||

| The tactical objectives of the ] were (a) to capture intact the bridges of the Bénouville-Ranville crossing, (b) to defend the crossing against the inevitable armoured counter-attacks, (c) to destroy German artillery at the ] battery, which threatened Sword Beach, and (d) to destroy five bridges over the ] to further restrict movement of ground forces from the east. | |||

| ===British and Canadian=== | |||

| Airborne troops, mostly paratroopers of the ] and ], including the ], began landing after midnight, 6 June and immediately encountered elements of the ]. At dawn, the Battle Group ] of the ] counterattacked from the south on both sides of the Orne River. By this time the paratroopers had established a defensive perimeter surrounding the ]. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but the airborne troops held. Shortly after noon, they were reinforced by commandos of the ]. By the end of D-Day, 6th Airborne had accomplished each of its objectives. For several days, both British and German forces took heavy casualties as they struggled for positions around the Orne bridgehead. For example, the German 346th Infantry Division broke through the eastern edge of the defensive line on 10 June. Finally, British paratroopers overwhelmed entrenched ]s in the Battle of ] on 12 June. The Germans did not seriously threaten the bridgehead again. 6th Airborne remained on the line until it was evacuated in early September | |||

| {{Main|Operation Tonga|Operation Mallard}} | |||

| ] glider is examined by German troops]] | |||

| The first Allied action of D-Day was the ] via a glider assault at 00:16 (since renamed ] and ]). Both bridges were quickly captured intact, with light casualties by the ] Regiment. They were then reinforced by members of the ] and the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=52–53}}{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|pp=238–239}} The five bridges over the Dives were destroyed with minimal difficulty by the ].{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=240}}{{sfn|Beevor|2009|p=57}} Meanwhile, the pathfinders tasked with setting up radar beacons and lights for further paratroopers (scheduled to begin arriving at 00:50 to clear the landing zone north of ]) were blown off course and had to set up the navigation aids too far east. Many paratroopers, also blown too far east, landed far from their intended drop zones; some took hours or even days to be reunited with their units.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=239}}{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=222}} Major General ] arrived in the third wave of gliders at 03:30, along with equipment, such as antitank guns and jeeps, and more troops to help secure the area from counter-attacks, which were initially staged only by troops in the immediate vicinity of the landings.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|pp=228, 230}} At 02:00, the commander of the German 716th Infantry Division ordered Feuchtinger to move his 21st Panzer Division into position to counter-attack. However, as the division was part of the armoured reserve, Feuchtinger was obliged to seek clearance from ] before he could commit his formation.{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|p=230}} Feuchtinger did not receive orders until nearly 09:00, but in the meantime on his own initiative he put together a battle group (including tanks) to fight the British forces east of the Orne.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=282}} | |||

| Only 160 men out of the 600 members of the ] tasked with eliminating the enemy battery at Merville arrived at the rendezvous point. Lieutenant Colonel ], in charge of the operation, decided to proceed regardless, as the emplacement had to be destroyed by 06:00 to prevent it firing on the invasion fleet and the troops arriving on Sword Beach. In the ], Allied forces disabled the guns with plastic explosives at a cost of 75 casualties. The emplacement was found to contain 75 mm guns rather than the expected 150 mm heavy coastal artillery. Otway's remaining force withdrew with the assistance of a few members of the ].{{sfn|Beevor|2009|pp=56–58}} | |||

| ====American airborne landings==== | |||

| {{Main|American airborne landings in Normandy}} | |||

| ] examine a knocked out German ] with a dead German crewman on the gun barrel.]] | |||

| The U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, numbering 13,000 paratroopers and delivered by 12 troop carrier groups of the IX Troop Carrier Command, were less fortunate in quickly completing their main objectives. To achieve surprise, the drops were routed to approach Normandy from the west. Numerous factors affected their performance, but the primary one was the decision to make a massive parachute drop at night (a tactic not used again for the rest of the war). As a result, 45% of units were widely scattered and unable to rally. Efforts of the early wave of ] teams to mark the landing zones were largely ineffective, and the ] beacons used to guide in the waves of ]s to the drop zones were a flawed system. | |||

| With this action, the last of the D-Day goals of the British 6th Airborne Division was achieved.{{sfn|Wilmot|1997|p=242}} They were reinforced at 12:00 by commandos of the ], who landed on Sword Beach, and by the ], who arrived in gliders at 21:00 in ].{{sfn|Ford|Zaloga|2009|loc=Map, pp. 216–217}} | |||

| Three regiments of 101st Airborne paratroopers were dropped first, between 00:48 and 01:40, followed by the 82nd Airborne's drops between 01:51 and 02:42. Each operation involved approximately 400 C-47 aircraft. Two pre-dawn glider landings brought in anti-tank guns and support troops for each division. On the evening of D-Day two additional glider landings brought in two battalions of artillery and 24 howitzers to the 82nd Airborne. Additional glider operations on 7 June delivered the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment to the 82nd Airborne, and two large supply parachute drops that date were ineffective. | |||

| ==Beach landings== | |||