| Revision as of 13:07, 7 September 2009 view sourceWest Virginian (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers114,656 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:07, 16 January 2025 view source PrimeBOT (talk | contribs)Bots2,077,782 editsm Task 24: template replacement following a TFDTag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Italian navigator and explorer (1451–1506)}} | ||

| {{Redirect2|Cristoforo Colombo|Admiral of the Ocean Sea|his direct descendant|Cristóbal Colón de Carvajal, 18th Duke of Veragua||Christopher Columbus (disambiguation)|and|Cristoforo Colombo (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Pp-semi-indef|small=yes|expiry=March 17, 2009}} | |||

| {{pp-dispute|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Infobox Person | |||

| {{Pp-move|small=yes}} | |||

| | name = Christopher Columbus | |||

| {{Pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| | image = Colomb.jpeg | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| {{Infobox officeholder | |||

| | occupation = ] for the ] | |||

| | honorific-prefix = Admiral of the Ocean Sea | |||

| | image = Portrait of a Man, Said to be Christopher Columbus.jpg | |||

| | caption = Posthumous portrait of Christopher Columbus by ]. | |||

| | caption = Posthumous portrait of a man, said to be Christopher Columbus, by ], 1519{{efn|There are no known authentic portraits of Columbus.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lester |first1=Paul M. |title=Looks are deceiving: The portraits of Christopher Columbus |journal=Visual Anthropology |date=January 1993 |volume=5 |issue=3–4 |pages=211–227 |doi=10.1080/08949468.1993.9966590 | issn=0894-9468}}</ref>}} | |||

| | birth_date = c.1451 | |||

| | order = 1st | |||

| | birth_place = ], Liguria | |||

| | office = Governor of the Indies | |||

| | death_date = {{death date|mf=yes|1506|5|20|df=y}} | |||

| | term_start = 1492 | |||

| | death_place = ], Spain | |||

| | term_end = 1499 | |||

| | names in other languages = {{lang-la|Christophorus Columbus}}; {{lang-ita|'''Cristoforo Colombo'''}}; {{lang-pt|'''Cristóvão Colombo'''}}, formerly ''Christovam Colom''; Spanish: '''Cristóbal Colón'''; {{lang-ca|'''Cristòfor Colom'''}} | |||

| | appointed = ] | |||

| | nationality = Genoese | |||

| | predecessor = Office Established | |||

| | other_names = Genoese: Christoffa Corombo<br />Spanish: Cristóbal Colón<br />Latin: Christophorus Columbus | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| | birth_date = Between 25 August and 31 October 1451 | |||

| | spouse = ] (c. 1476-1485) | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] | |||

| | children = ]<br />] | |||

| | death_date = {{death date|1506|05|20|df=y}} (aged 54) | |||

| | relatives = Giovanni Pellegrino, Giacomo and ] (brothers) | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | resting_place = ], Seville, Spain | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|1479|1484|end=died}} | |||

| | partner = ] | |||

| | children = {{hlist|]|]|]}} | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | relatives = ] (brother) | |||

| | profession = ] | |||

| | signature = Columbus Signature.svg | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!--ACCORDING TO ], places of b./d. must be listed in the text proper--> | |||

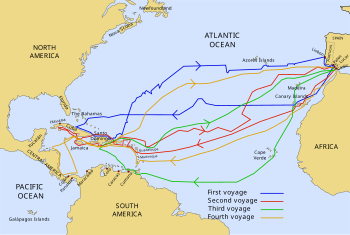

| '''Christopher Columbus''' (c. 1451 – 20 May 1506) was a ] ], ] and ] whose voyages across the ] led to general European awareness of the ] in the ]. Although not the first to reach the Americas from ]—he was preceded by the ], led by ], who built a temporary settlement 500 years earlier at ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pc.gc.ca/lhn-nhs/nl/meadows/index_e.asp |title=Parks Canada — L'Anse aux Meadows National Historic Site of Canada |publisher=Pc.gc.ca |date=2009-04-24 |accessdate=2009-07-29}}</ref>— Columbus initiated widespread contact between ] and ]. With his four voyages of discovery and several attempts at establishing a settlement on the island of ], all funded by ] of ], he initiated the process of ] which foreshadowed general ] of the "]." (The term "]" is usually used to refer to the peoples and cultures of the Americas before the arrival of Columbus and his European successors.) | |||

| '''Christopher Columbus'''{{efn|In other relevant languages: | |||

| His initial 1492 voyage came at a critical time of growing national ] and ] between developing nation states seeking wealth from the establishment of ]s and ]. In this ] climate, Columbus's far-fetched scheme won the attention of ] of Spain. Severely underestimating the ] of the ], he estimated that a westward route from ] to ] would be shorter and more direct than the overland ] through ]. If true, this would allow Spain entry into the lucrative ]{{mdash}}heretofore commanded by the ] and ]. Following his plotted course, he instead landed within the ] at a locale he named ''San Salvador''. Mistaking the ] island for the ] mainland, he referred to its inhabitants as "Indios". | |||

| * {{langx|it|Cristoforo Colombo}} {{IPA|it|kriˈstɔːforo koˈlombo|}} | |||

| * {{langx|lij|Cristoffa C(or)ombo}} {{IPA|lij|kɾiˈʃtɔffa kuˈɾuŋbu, – ˈkuŋbu|}} | |||

| * {{langx|es|link=yes|Cristóbal Colón}} {{IPA|es|kɾisˈtoβal koˈlon|}} | |||

| * {{langx|pt|Cristóvão Colombo}} {{IPA|pt|kɾiʃˈtɔvɐ̃w kuˈlõbu|}} | |||

| * {{langx|ca|Cristòfor}} (or {{lang|ca|Cristòfol}}) {{lang|ca|Colom}} {{IPA|ca|kɾisˈtɔfuɾ kuˈlom, -ful k-|}} | |||

| * {{langx|la|Christophorus Columbus}}.}} ({{IPAc-en|k|ə|ˈ|l|ʌ|m|b|ə|s}};<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.dictionary.com/browse/columbus|title=Dictionary.com | Meanings & Definitions of English Words|website=Dictionary.com}}</ref> between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italian<ref name="Delaney2011">{{Cite book |last=Delaney |first=Carol |title=Columbus and the Quest for Jerusalem |year=2011 |publisher=Free Press/Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-4391-0237-4 |edition=1st |location=United States of America |page=74 |language=English}}</ref>{{Efn|Though the modern state of Italy had yet to be established, the Latin equivalent of the term ''Italian'' had been in use for natives of the region since antiquity; most scholars believe Columbus was born in Genoa.<ref name="FlintECB2022">{{cite web |last1=Flint |first1=Valerie I.J. |title=Christopher Columbus |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Christopher-Columbus |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |date=16 May 2021 |access-date=2 January 2022 |language=en}}</ref>}} explorer and navigator from the ]<ref name="Delaney2011"/><ref name="FlintECB2022"/> who completed ] sponsored by the ], opening the way for the widespread European ] and ]. His expeditions were the first known European contact with the Caribbean and Central and South America. | |||

| The name ''Christopher Columbus'' is the ] of the Latin {{lang|la|Christophorus Columbus}}. Growing up on the coast of ], he went to sea at a young age and traveled widely, as far north as the ] and as far south as what is now ]. He married Portuguese noblewoman ], who bore a son, ], and was based in Lisbon for several years. He later took a Castilian mistress, ], who bore a son, ].<ref name="Fernández-Armesto2010">{{cite book |last1=Fernández-Armesto |first1=Felipe |title=Columbus on Himself |year=2010 |publisher=Hackett Publishing |isbn=978-1-60384-317-1 |page=270 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jZmOBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA270 |quote=The date of Fernando's birth, November 1488, gives a terminus ante quem early in that year for the start of Columbus's liaison with Beatriz Enríquez. She was of peasant parentage, but, when Columbus met her, was the ward of a well-to-do relative in Cordoba. A meat business gave her income of her own, mentioned in the only other record of Columbus's solicitude for her: a letter to Diego, written in 1502, just before departure on the fourth Atlantic crossing, in which the explorer enjoins his son to 'take Beatriz Enriquez in your care for love of me, as you your own mother'. Varela, Cristóbal Colón, p. 309.}}</ref><ref name="Taviani201624">{{cite book |last1=Taviani |first1=Paolo Emilio |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |pages=24–25 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA24 |chapter=Beatriz de Arana |quote=Columbus never married Beatriz. When he returned from the first voyage, he was given the greatest of honors and elevated to the highest position in Spain. Because of his discovery, he became one of the most illustrious persons at the Spanish court and had to submit, like all the great persons of the time, to customary legal restrictions on matters of marriage and extramarital relations. The Alphonsine laws forbade extramarital relations of concubinage for "illustrious people" (king, princes, dukes, counts, marquis) with plebeian women, if they themselves were or their forefathers had been of inferior social condition.}}</ref>{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=126}} | |||

| Academic consensus is that Columbus was born in ], though there are ]. The name ''Christopher Columbus'' is the Anglicisation of the ] ''Christophorus Columbus''. The original name in 15<sup>th</sup> century ] was ''Christoffa''<ref>Rime diverse, Pavia, 1595, p.117</ref> ''Corombo''<ref>Ra Gerusalemme deliverâ, Genoa, 1755, XV-32</ref> ({{pron|kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu}}) The name is rendered in modern Italian as ''Cristoforo Colombo'', in ] as ''Cristóvão Colombo'' (formerly ''Christovam Colom''), and in Spanish as ''Cristóbal Colón''. | |||

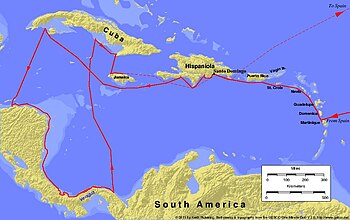

| Largely self-educated, Columbus was knowledgeable in geography, astronomy, and history. He developed a plan to seek a western sea passage to the ], hoping to profit from the lucrative ]. After the ], and Columbus's persistent lobbying in multiple kingdoms, the Catholic Monarchs, Queen ] and King ], agreed to sponsor a journey west. Columbus left Castile in August 1492 with three ships and made landfall in the Americas on 12 October, ending the period of human habitation in the Americas now referred to as the ]. His landing place was an island in ], known by its native inhabitants as ]. He then visited the islands now known as Cuba and ], establishing ] in what is now ]. Columbus returned to Castile in early 1493, with captured natives. ] soon spread throughout Europe. | |||

| The anniversary of Columbus's 1492 landing in the Americas is observed as ] on October 12 in Spain and throughout the Americas, except that in the United States it is observed on the second Monday in October. | |||

| Columbus made three further voyages to the Americas, exploring the ] in 1493, ] and the northern coast of South America in 1498, and the east coast of Central America in 1502. Many names he gave to geographical features, particularly islands, are still in use. He gave the name ''indios'' ("Indians") to the ] he encountered. The extent to which he was aware the Americas were a wholly separate landmass is uncertain; he never clearly renounced his belief he had reached the Far East. As a colonial governor, Columbus was accused by some of his contemporaries of significant brutality and removed from the post. Columbus's strained relationship with the ] and its colonial administrators in America led to his arrest and removal from Hispaniola in 1500, and later to ] over the privileges he and his heirs claimed were owed to them by the crown. | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| <!--THIS SECTION IS LARGELY BASED ON BRITANNICA AND MORISON's ''Christopher Columbus''--> | |||

| {{See also|Origin theories of Christopher Columbus}} | |||

| It is generally, although not universally, agreed that Christopher Columbus was born between 25 August and 31 October 1451 in ], part of modern Italy.<ref>Phillips, William D., and Carla Rahn Phillips. ''The Worlds of Christopher Columbus''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. Page 9. <br />"''Even with less than a complete record, however, scholars can state with assurance that Columbus was born in the republic of Genoa in northern Italy, although perhaps not in the city itself, and that his family made a living in the wool business as weavers and merchants...The two main early biographies of Columbus have been taken as literal truth by hundreds of writers, in large part because they were written by individual closely connected to Columbus or his writings. ...Both biographies have serious shortcomings as evidence.''"</ref> His father was ], a middle-class ] ], who later also had a ] ] where Christopher was a helper, working both in Genoa and ]. His mother was ]. Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino and Giacomo were his brothers. Bartolomeo worked in a ] workshop in ] for at least part of his adulthood.<ref name=britannica> Encyclopedia Britannica, 1993 ed., Vol. 16, pp. 605ff / Morison, ''Christopher Columbus'', 1955 ed., pp. 14ff</ref> | |||

| Columbus's expeditions inaugurated a period of exploration, conquest, and colonization that lasted for centuries, thus bringing the Americas into the European sphere of influence. The transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the ] and ] that followed his first voyage are known as the ], named after him. These events and the effects which persist to the present are often cited as the beginning of the ].<ref>{{cite book |quote= Most researchers however trace the beginning of the early modern era to Christopher Columbus's discovery of the Americas in the 1490s |title=Cross-Border Labor Mobility: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives |first=Caf |last=Dowlah |year=2020 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nC3rDwAAQBAJ |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan |isbn= 978-3-030-36506-6 }}</ref><ref>Mills, Keneth and Taylor, William B., , p. 36, SR Books, 1998, {{ISBN|0-8420-2573-1}}</ref> | |||

| Columbus never wrote any works in his native language, but it can be assumed this was the ]. In one of his writings, Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at the age of 10. In 1470 the Columbus family moved to ], where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Columbus was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of ] to support his attempt to conquer the ]. | |||

| Columbus was widely celebrated in the centuries after his death, but public perception fractured in the 21st century due to greater attention to the harms committed under his governance, particularly the beginning of the ] of Hispaniola's indigenous ] people, caused by Old World diseases and mistreatment, including ]. ] in the Western Hemisphere bear ], including the South American country of ], the Canadian province of ], the American city ], and the United States capital, the ]. | |||

| In 1473 Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro and Spinola families of Genoa. Later he allegedly made a trip to ], a Genoese colony in the ]. In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. He docked in Bristol, Galway, in Ireland and was possibly in Iceland in 1477. In 1479 Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in ], keeping on trading for the Centurione family. He married ] Perestrello, daughter of the ] governor, the Portuguese nobleman of Genoese origin ]. In 1479 or 1480, his son ] was born. Some records report that Felipa died in 1485. It is also speculated that Columbus may have simply left his first wife. In either case Columbus found a mistress in Spain in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://columbus-day.123holiday.net/christopher_columbus_2.html |title=Christopher Columbus Biography Page 2 |publisher=Columbus-day.123holiday.net |date= |accessdate=2009-07-29}}</ref> | |||

| == |

== Early life == | ||

| {{further|topic=Columbus's birthplace and background|Origin theories of Christopher Columbus}} | |||

| ] in ], Italy, an 18th-century reconstruction of the house in which Columbus grew up. The original was likely destroyed during the 1684 ].<ref>{{cite book |title=Una Giornata nella Città |trans-title=A Day in the City |first1=Corinna |last1=Praga |author2=Laura Monac |publisher=Sagep Editrice |location=Genoa |year=1992 |page=14 |language=it}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |url=http://www.ortidicarignano.it/files/seiitinerariinportoria.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.ortidicarignano.it/files/seiitinerariinportoria.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |chapter=Casa di Colombo |first1=Alfredo |last1=Preste |author2=Alessandro Torti |author3=Remo Viazzi |title=Sei itinerari in Portoria |publisher=Grafiche Frassicomo |trans-title=Six itineraries in Portoria |location=Genova |year=1997 |language=it}}</ref>]] | |||

| Columbus's early life is obscure, but scholars believe he was born in the ] between 25 August and 31 October 1451.<ref name="Edwards2014">{{cite book |last1=Edwards |first1=J. |title=Ferdinand and Isabella |date=2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-89345-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=pnHJAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA118 |page=118}}</ref> His father was ], a wool weaver who worked in Genoa and ], and owned a cheese stand at which young Christopher worked. His mother was ].{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=91}} He had three brothers—], Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo (also called Diego)<ref>{{Cite NIE| title=Columbus, Diego (brother) |display=Columbus, Diego. The youngest brother of Christopher Columbus}} – The names ] and ] are ], along with ], all sharing a common origin. See ''Behind the Name'', Mike Campbell, pages , , and . All retrieved 3 February 2017.</ref>—as well as a sister, Bianchinetta.{{sfn|Bergreen|2011|ref=none|p=56}} Bartholomew ran a ] workshop in ] for at least part of his adulthood.<ref name="King2021">{{cite book |last1=King |first1=Ross |title=The Bookseller of Florence: The Story of the Manuscripts That Illuminated the Renaissance |year=2021 |publisher=Atlantic Monthly Press |isbn=978-0-8021-5853-6 |page=264 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FoskEAAAQBAJ&pg=PT264}}</ref> | |||

| His native language is presumed to have been a ] (]) as his first language, though Columbus probably never wrote in it.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=96}} His name in 15th-century Genoese was ''Cristoffa Corombo'',<ref name="Galante2022">{{cite book |last1=Galante |first1=John Starosta |title=On the Other Shore: The Atlantic Worlds of Italians in South America During the Great War |year=2022 |publisher=Univ of Nebraska Press |isbn=978-1-4962-2958-8 |page=13 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fapJEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA13}} {{IPA|lij|kriˈʃtɔffa kuˈɹuŋbu}} {{cite book| author=Consulta Ligure| title=Vocabolario delle parlate liguri| trans-title=Vocabulary of Ligurian Speech: Specialized Vocabulary| publisher=Sage| year=1982| isbn=978-8-8705-8044-0}}</ref> in Italian, ''Cristoforo Colombo'', and in Spanish ''Cristóbal Colón''.<ref name="SánchezGuruléBroughton1990">{{cite book |last1=Sánchez |first1=Joseph P. |last2=Gurulé |first2=Jerry L. |last3=Broughton |first3=William H. |title=Bibliografia Colombina, 1492–1990: Books, Articles and Other Publications on the Life and Times of Christopher Columbus |year=1990 |publisher=National Park Service, Spanish Colonial Research Center |page=ix |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vw60dj9PV10C&pg=PR9}}</ref><ref name="Bedini2016">{{cite book |last1=Bedini |first1=Silvio A. |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |page=viii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PR8}}</ref> | |||

| In one of his writings, he says he went to sea at 14.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=96}} In 1470, the family moved to ], where Domenico took over a tavern. Some modern authors have argued that he was not from Genoa, but from the ] region of Spain<ref name="Wilgus1973">{{cite book |last1=Wilgus |first1=Alva Curtis |title=Latin America, 1492–1942: A Guide to Historical and Cultural Development Before World War II |year=1973 |publisher=Scarecrow Reprint Corporation |isbn=978-0-8108-0595-8 |page=71 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=PZoWAAAAYAAJ&q=%22New%20theories%22}}</ref> or from Portugal.<ref>{{in lang|pt}} "Armas e Troféus." Revista de História, Heráldica, Genealogia e Arte. 1994, VI serie – Tomo VI, pp. 5–52. Retrieved 21 November 2011.{{verify source|date=June 2020}}</ref> These competing hypotheses have been discounted by most scholars.{{sfn|Davidson|1997|p=3}}{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=85}} | |||

| ], Genoa]] | |||

| In 1473, Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the wealthy ], Centurione, and Di Negro families of Genoa.<ref name="Lyon1992">{{cite book |last1=Lyon |first1=Eugene |editor1-last=McGovern |editor1-first=James R. |title=The World of Columbus |year=1992 |publisher=Mercer University Press |isbn=978-0-86554-414-7 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3mOh34X6UY8C&pg=PA90 |pages=90–91 |chapter=Navigation and Ships in the Age of Columbus}}</ref> Later, he made a trip to the Greek island ] in the ], then ruled by Genoa.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=93}} In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry valuable cargo to northern Europe. He probably visited ], England,<ref name="Vigneras2016">{{cite book |last1=Vigneras |first1=L. A. |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |date=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |page=175 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA175 |chapter=Columbus in Portugal |quote=It is most probable that Columbus visited Bristol, where he was introduced to English commerce with Iceland.}}</ref> and ], Ireland,<ref name="UrelandClarkson2011">{{cite book |last1=Ureland |first1=P. Sture |editor1-last=Ureland |editor1-first=P. Sture |editor2-last=Clarkson |editor2-first=Iain |title=Language Contact across the North Atlantic: Proceedings of the Working Groups held at the University College, Galway (Ireland), 1992 and the University of Göteborg (Sweden), 1993 |year=2011 |publisher=Walter de Gruyter |isbn=978-3-11-092965-2 |page=14 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=O46ZKTUg2ogC&pg=PA14 |chapter=Introduction}}</ref> where he may have visited ].<ref name="Graves1949">{{cite book |last1=Graves |first1=Charles |title=Ireland Revisited |year=1949 |publisher=Hutchinson |page=151 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DedQAQAAMAAJ&q=%22Christopher%20Columbus%22%20%22St.%20Nicholas%22%20%22Galway%22}}</ref> It has been speculated he went to ] in 1477, though many scholars doubt this.<ref name="Enterline2003">{{cite book| last1=Enterline| first1=James Robert| url=https://books.google.com/books?id=blJZYInNFkkC&pg=PT247| title=Erikson, Eskimos & Columbus: Medieval European Knowledge of America| year=2003| publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press+ORM| isbn=978-0-8018-7547-2| page=247| quote=Some writers have suggested that it was during this visit to Iceland that Columbus heard of land in the west. Keeping the source of his information secret, they say, he concocted a plan to sail westward. Certainly the knowledge was generally available without attending any saga-telling parties. That this knowledge reached Columbus seems unlikely, however, for later, when trying to get backing for his project, he went to great lengths to unearth even the slightest scraps of information that would add to the plausibility of his scheme. Knowledge of the Norse explorations could have helped.}}</ref><ref name="PaolucciPaolucci1992">{{cite book |last1=Paolucci |first1=Anne |last2=Paolucci |first2=Henry |author1-link=Anne Paolucci |title=Columbus, America, and the World |date=1992 |publisher=Council on National Literatures |isbn=978-0-918680-33-4 |page=140 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AhwWAQAAIAAJ&q=%221477%22 |quote=Many Columbists ... have doubted that Columbus could ever have gone to Iceland.}}</ref><ref name="Kolodny2012" /><ref name=":7">{{cite journal| last=Quinn| first=David B.| year=1992| title=Columbus and the North: England, Iceland, and Ireland| journal=The William and Mary Quarterly| volume=49| issue=2| pages=278–297| doi=10.2307/2947273| jstor=2947273| issn=0043-5597}}</ref> It is known that in the autumn of 1477, he sailed on a Portuguese ship from Galway to Lisbon, where he found his brother Bartholomew, and they continued trading for the Centurione family. Columbus based himself in Lisbon from 1477 to 1485. In 1478, the Centuriones sent Columbus on a sugar-buying trip to Madeira.<ref name="Fernández-Armesto1991">{{cite book |last1=Fernández-Armesto |first1=Felipe |title=Columbus |year=1991 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-215898-7 |page=xvii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NTwLAAAAYAAJ&q=%221478%20Sugar-buying%20trip%22}}</ref> He married ], daughter of ], a Portuguese nobleman of ] origin,<ref name="FreitasManey1893">{{cite book |last1=Freitas |first1=Antonio Maria de |last2=Maney |first2=Regina |title=The Wife of Columbus: With Genealogical Tree of the Perestrello and Moniz Families |publisher=Stettinger, Lambert & Co |location=New York |year=1893 |url=https://archive.org/details/wifeofcolumbus00frei/page/32/mode/1up |page=32}}</ref> who had been the ] of ].<ref name="Alessandrini2012">{{cite web |last1=Alessandrini |first1=Nunziatella |title=Os Perestrello: uma família de Piacenza no Império Português (século XVI) |trans-title=The Perestrellos: A Piacenza family in the Portuguese Empire (16th century) |url=https://www.academia.edu/6148469 |publisher=Universidade NOVA de Lisboa |location=Lisbon |page=90 |date=1 January 2012 |language=pt |quote=Finally, the most famous son of Filippone, Bartolomeu Perestrello (I), who participated in the rediscovery of the island of Madeira in 1418, and was ] and ''feitor'' of Porto Santo until, by a letter of 1 November 1446 from Infante Henrique, he became the first donatary captain of the island, a privilege that continued until the 19th century, with the last donatary captain Manuel da Câmara Bettencourt Perestrello in 1814.}}</ref> | |||

| ] of the United States of America – 19th century copy from an engraving by ]]] | |||

| In 1479 or 1480, Columbus's son ] was born. Between 1482 and 1485, Columbus traded along the coasts of ], reaching the Portuguese trading post of ] at the ] in present-day ].<ref name="Suranyi2015">{{cite book |last1=Suranyi |first1=Anna |title=The Atlantic Connection: A History of the Atlantic World, 1450–1900 |year=2015 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-50066-7 |page=17 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=J6FhCQAAQBAJ&pg=PA17}}</ref> Before 1484, Columbus returned to Porto Santo to find that his wife had died.{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|p=63}} He returned to Portugal to settle her estate and take Diego with him.<ref name="Taviani2016">{{cite book |last1=Taviani |first1=Paolo Emilio |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |page=24 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA24 |chapter=Beatriz Arana }}</ref> | |||

| He left Portugal for ] in 1485, where he took a mistress in 1487, a 20-year-old orphan named ].{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=126}} It is likely that Beatriz met Columbus when he was in ], a gathering place for Genoese merchants and where the court of the ] was located at intervals. Beatriz, unmarried at the time, gave birth to Columbus's second son, ], in July 1488, named for the monarch of Aragon. Columbus recognized the boy as his offspring. Columbus entrusted his older, legitimate son Diego to take care of Beatriz and pay the pension set aside for her following his death, but Diego was negligent in his duties.<ref>Taviani, "Beatriz Arana" in ''The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia'', vol. 1, pp. 24–25.</ref> | |||

| ]'', with his handwritten notes in Latin written in the margins]] | |||

| Columbus learned ], Portuguese, and Castilian. He read widely about astronomy, geography, and history, including the works of ], ]'s ''Imago Mundi'', the travels of ] and ], ]'s '']'', and ]'s '']''. According to historian ], | |||

| <blockquote>Columbus was not a scholarly man. Yet he studied these books, made hundreds of marginal notations in them and came out with ideas about the world that were characteristically simple and strong and sometimes wrong ...<ref name="ESMorgan">{{cite news |last1=Morgan |first1=Edmund S. |author-link=Edmund Morgan (historian) |title=Columbus' Confusion About the New World |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/travel/columbus-confusion-about-the-new-world-140132422/ |magazine=] |date=October 2009 }}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| == Quest for Asia == | |||

| === Background === | |||

| ]'s notions of the geography of the Atlantic Ocean (shown superimposed on a modern map), which directly influenced Columbus's plans]] | |||

| Under the ]'s hegemony over ] and the '']'', Europeans had long enjoyed a safe land passage on the ] to ], parts of ], including ] and ], which were sources of valuable goods. With the ] to the ] in 1453, the Silk Road was closed to Christian traders.<ref name="DavidannGilbert2019">{{cite book |last1=Davidann |first1=Jon |last2=Gilbert |first2=Marc Jason |title=Cross-Cultural Encounters in Modern World History, 1453–Present |year=2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-429-75924-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8f6GDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT39 |page=39 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| In 1474, the Florentine astronomer ] suggested to King ] that sailing west across the Atlantic would be a quicker way to reach the ] (Spice) Islands, ], ] and ] than the route around Africa, but Afonso rejected his proposal.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=108}}<ref name="Boxer1967">{{cite book |last1=Boxer |first1=Charles Ralph |title=The Christian Century in Japan, 1549–1650 |year=1967 |publisher=University of California Press |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=2R4DA2lip9gC&pg=PA2 |language=en}}</ref> In the 1480s, Columbus and his brother proposed a plan to reach the ] by sailing west. Columbus supposedly wrote to Toscanelli in 1481 and received encouragement, along with a copy of a map the astronomer had sent Afonso implying that a westward route to Asia was possible.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=227}} Columbus's plans were complicated by ]'s rounding of the ] in 1488, which suggested the ] around Africa to Asia.{{sfn|Murphy|Coye|2013|p=}} | |||

| Columbus had to wait until 1492 for King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain to support his voyage across the Atlantic to find gold, spices, a safer route to the East, and converts to Christianity.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Muzio |first=Tim Di |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i-LaDwAAQBAJ |title=The Tragedy of Human Development: A Genealogy of Capital as Power |year= 2017 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-78348-715-8 |page=58 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Echevarría |first1=Roberto Gonzalez |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8lrcKp81eawC |title=The Cambridge History of Latin American Literature |last2=Pupo-Walker |first2=Enrique |year= 1996 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-34069-4 |page=63 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Johanyak |first1=D. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_UzFAAAAQBAJ |title=The English Renaissance, Orientalism, and the Idea of Asia |last2=Lim |first2=W. |year=2010 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-0-230-10622-2 |page=136 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=King |first=William Casey |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UElGCn0QN3gC&pg=PT166 |title=Ambition, A History: From Vice to Virtue |year= 2013 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-18984-1 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ] and other commentators have argued that Columbus was a ] and ] and that these beliefs motivated his quest for Asia in a variety of ways. Columbus often wrote about seeking gold in the log books of his voyages and writes about acquiring it "in such quantity that the sovereigns... will undertake and prepare to go conquer the ]" in a fulfillment of ].{{efn|In an account of his fourth voyage, Columbus wrote that "] and ] must be rebuilt by Christian hands".<ref>{{cite thesis |last1=Sheehan |first1=Kevin Joseph |title=Iberian Asia: the strategies of Spanish and Portuguese empire building, 1540–1700 |year=2008 |id={{ProQuest|304693901}} |oclc=892835540 }}{{page needed|date=June 2020}}</ref>}} Columbus often wrote about ] all races to Christianity.<ref name="jstor3879352">{{cite journal| last1=Delaney| first1=Carol| author-link=Carol Delaney| date=8 March 2006| title=Columbus's Ultimate Goal: Jerusalem| url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f671/e4f2cd4ba48c3d113fde22094738b87058aa.pdf| journal=]| publisher=]| volume=48| issue=2| pages=260–92| doi=10.1017/S0010417506000119| jstor=3879352| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200226123645/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f671/e4f2cd4ba48c3d113fde22094738b87058aa.pdf| archive-date=26 February 2020| s2cid=144148903}}</ref> Abbas Hamandi argues that Columbus was motivated by the hope of " Jerusalem from Muslim hands" by "using the resources of newly discovered lands".<ref>{{cite journal| last1=Hamdani| first1=Abbas| year=1979| title=Columbus and the Recovery of Jerusalem| journal=]| publisher=]| location=Ann Arbor, Michigan| volume=99| issue=1| pages=39–48| doi=10.2307/598947| jstor=598947}}</ref> | |||

| === Geographical considerations === | |||

| Despite ] to the contrary, nearly all educated Westerners of Columbus's time knew that the ], a concept that had been understood since ].{{sfn|Murphy|Coye|2013|p=244}} The techniques of ], which uses the position of the Sun and the stars in the sky, had long been in use by astronomers and were beginning to be implemented by mariners.<ref name="Willoz-Egnor2013">{{cite web|last1=Willoz-Egnor |first1=Jeanne |title=Mariner's Astrolabe |url=https://www.ion.org/museum/item_view.cfm?cid=6&scid=13&iid=25 |url-status=live |year=2013 |access-date=5 July 2021|website=]|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029202740/http://www.ion.org/museum/item_view.cfm?cid=6&scid=13&iid=25 |archive-date=29 October 2013}}</ref><ref name="Smith2002">{{cite journal |last1=Smith |first1=Ben |title=An astrolabe from Passa Pau, Cape Verde Islands |journal=International Journal of Nautical Archaeology |date=1 January 2002 |volume=31 |issue=1 |pages=99–107 |doi=10.1006/ijna.2002.1021 |bibcode=2002IJNAr..31...99S |url=https://www.academia.edu/31744402}}</ref><!-- Please do not remove url just because the DOI is given; the webpage has a link to a free download, and the very good paper can be read right there. --> | |||

| However Columbus made several errors in calculating the size of the Earth, the distance the continent extended to the east, and therefore the distance to the west to reach his goal. | |||

| First, as far back as the 3rd century BC, ] had correctly computed the circumference of the Earth by using simple geometry and studying the shadows cast by objects at two remote locations.<ref>{{cite book| title=The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Universe| last=Ridpath| first=Ian| publisher=Watson-Guptill| year=2001| isbn=978-0-8230-2512-1| location=New York| page=31}}</ref><ref>{{cite book| first=Carl| last=Sagan| author-link=Carl Sagan| title=Cosmos| publisher=]| url=https://archive.org/details/cosmossaga00saga/page/14/mode/2up?q=Eratosthenes |location=New York | year=1980| isbn=978-0-3945-0294-6| pages=34–35 |access-date=20 February 2022 |url-access=registration}}</ref> In the 1st century BC, ] confirmed Eratosthenes's results by comparing stellar observations at two separate locations. These measurements were widely known among scholars, but Ptolemy's use of the smaller, old-fashioned units of distance led Columbus to underestimate the size of the Earth by about a third.<ref name="Freely2013">{{cite book |last=Freely |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QsWSDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT36 |title=Before Galileo: The Birth of Modern Science in Medieval Europe |publisher=] |location=New York |year=2013 |isbn=978-1-4683-0850-1 |page=36 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ] mapmaking workshop of Bartholomew and Christopher Columbus<ref>"Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", p. 37. {{ISBN|978-2-35404-007-9}}</ref>]] | |||

| Second, three ] parameters determined the bounds of Columbus's enterprise: the distance across the ocean between Europe and Asia, which depended on the extent of the ], i.e., the Eurasian land-mass stretching east–west between Spain and China; the circumference of the Earth; and the number of miles or ] in a degree of ], which was possible to deduce from the theory of the relationship between the size of the surfaces of water and the land as held by the followers of ] in medieval times.<ref name="Randles1990">{{cite journal |last1=Randles |first1=W. G. L. |title=The Evaluation of Columbus' 'India' Project by Portuguese and Spanish Cosmographers in the Light of the Geographical Science of the Period |journal=Imago Mundi |date=January 1990 |volume=42 |issue=1 |page=50 |doi=10.1080/03085699008592691 |s2cid=129588714 |url=http://www.tau.ac.il/~corry/teaching/histint/download/Randles_Columbus.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.tau.ac.il/~corry/teaching/histint/download/Randles_Columbus.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |issn=0308-5694}}</ref> | |||

| From ]'s '']'' (1410), Columbus learned of ]'s estimate that a degree of ] (equal to approximately a degree of ] along the equator) spanned 56.67 ]s (equivalent to {{convert|66.2|nmi|km|1|abbr=off|sp=us|disp=comma}} or 76.2 mi), but he did not realize that this was expressed in the Arabic mile (about {{Convert|1,830|m|mi|abbr=out|sp=us|disp=or}}) rather than the shorter ] (about 1,480 m) with which he was familiar.<ref name="Mahmud2017">{{cite journal |last1=Khairunnahar |last2=Mahmud |first2=Khandakar Hasan |last3=Islam |first3=Md Ariful |title=Error calculation of the selected maps used in the Great Voyage of Christopher Columbus |journal=The Jahangirnagar Review, Part II |year=2017 |volume=XLI |page=67 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/348442261 |access-date=9 January 2022 |publisher=Jahangirnagar University |issn=1682-7422}}</ref> Columbus therefore estimated the size of the Earth to be about 75% of Eratosthenes's calculation.<ref name="McCormick2012">{{cite web |last1=McCormick |first1=Douglas |title=Columbus's Geographical Miscalculations |url=https://spectrum.ieee.org/columbuss-geographical-miscalculations |website=IEEE Spectrum |access-date=9 January 2022 |language=en |date=9 October 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Third, most scholars of the time accepted Ptolemy's estimate that ] spanned 180° longitude,<ref name="Gunn2018">{{cite book |last1=Gunn |first1=Geoffrey C. |title=Overcoming Ptolemy: The Revelation of an Asian World Region |date=2018 |publisher=Rowman & Littlefield |isbn=978-1-4985-9014-3 |pages=77–78 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xCRyDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA77 |language=en |quote=Constructed on a framework of latitude and longitude, the Ptolemy-revival map projections revealed the extent of the known world in relation to the whole. Typically, they displayed a Eurasian landmass extending through 180° of longitude from a prime meridian in the west (variously the Canary Islands or Cape Verde) to a location in the "Far East."}}</ref> rather than the actual 130° (to the Chinese mainland) or 150° (to Japan at the latitude of Spain). Columbus believed an even higher estimate, leaving a smaller percentage for water.<ref name="Zacher2016">{{cite book |last1=Zacher |first1=Christian K. |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |pages=676–677 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA676 |language=en}}</ref> In d'Ailly's ''Imago Mundi'', Columbus read ]'s estimate that the longitudinal span of Eurasia was 225° at the latitude of ].<ref name="Dilke2016">{{cite book |last1=Dilke |first1=O. A. W. |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |page=452 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA452 |language=en |chapter=Marinus of Tyre}}</ref> Some historians, such as ], have suggested that he followed the statement in the ] book ] (]) that "six parts are habitable and the seventh is covered with water."<ref name="Morison1974">{{cite book |last1=Morison |first1=Samuel Eliot |title=The European Discovery of America: The Southern Voyages A.D. 1492–1616 |date=1974 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-501377-1 |page=31 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=r4sOAQAAMAAJ&q=%222%20Esdras%22 |language=en}}</ref> He was also aware of Marco Polo's claim that Japan (which he called "Cipangu") was some {{Convert|2414|km|mi|abbr=on}} to the east of China ("Cathay"),<ref name="Butel2002">{{cite book |last1=Butel |first1=Paul |title=The Atlantic |year=2002 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-134-84305-3 |page=47 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sLGIAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA47 |language=en}}</ref> and closer to the equator than it is. He was influenced by Toscanelli's idea that there were inhabited islands even farther to the east than Japan, including the mythical ], which he thought might lie not much farther to the west than the ],{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=}} and the distance westward from the ] to the Indies as only 68 degrees, equivalent to {{Convert|3080|nmi|abbr=on}} (a 58% error).<ref name="McCormick2012"/> | |||

| Based on his sources, Columbus estimated a distance of {{convert|2,400|nmi|abbr=on}} from the Canary Islands west to Japan; the actual distance is {{convert|10600|nmi|abbr=on}}.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|p=110}}<ref name="Edson2007">{{cite book |last1=Edson |first1=Evelyn |title=The World Map, 1300–1492: The Persistence of Tradition and Transformation |year=2007 |publisher=JHU Press |isbn=978-0-8018-8589-1 |page=205 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dhgYlhXJy_QC&pg=PA205 |language=en}}</ref> No ship in the 15th century could have carried enough food and fresh water for such a long voyage,<ref name="Taylor2002">{{cite book |last1=Taylor |first1=Alan |title=American Colonies: The Settling of North America (The Penguin History of the United States, Volume 1) |year=2002 |publisher=Penguin |isbn=978-0-14-200210-0 |page=34 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NPoAQRgkrOcC&pg=PA34 |language=en}}</ref> and the dangers involved in navigating through the uncharted ocean would have been formidable. Most European navigators reasonably concluded that a westward voyage from Europe to Asia was unfeasible. The Catholic Monarchs, however, having completed the '']'', an expensive war against the ] in the ], were eager to obtain a competitive edge over other European countries in the quest for trade with the Indies. Columbus's project, though far-fetched, held the promise of such an advantage.<ref>{{cite book|first=De Lamar|last=Jensen|date=1992|title=Renaissance Europe|publisher=]|location=Lexington, Massachusetts|edition=2nd|isbn= 978-0-669-20007-2 |page=341}}</ref> | |||

| ]'', by ]]] | |||

| === Nautical considerations === | |||

| {{see also|#Navigational expertise}} | |||

| Though Columbus was wrong about the number of degrees of longitude that separated Europe from the Far East and about the distance that each degree represented, he did take advantage of the ], which would prove to be the key to his successful navigation of the Atlantic Ocean. He planned to first sail to the Canary Islands before continuing west with the northeast trade wind.<ref name="Gómez2008">{{cite book |last1=Gómez |first1=Nicolás Wey |title=The Tropics of Empire: Why Columbus Sailed South to the Indies |year=2008 |publisher=MIT Press |isbn=978-0-262-23264-7 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WLntAAAAMAAJ&q=%22northeastern%20trade%20winds%22 |page=37 |language=en |quote=It is also known that wind patterns and water currents in the Atlantic were crucial factors for launching an outward passage from the Canaries: Columbus understood that his chance of crossing the ocean was significantly greater just beyond the Canary calms, where he expected to catch the northeastern trade winds—although, as some authors have pointed out, "westing" from the Canaries, instead of dipping farther south, was hardly an optimal sailing choice, since Columbus's fleet was bound to lose, as soon it did, the northeasterlies in the mid-Atlantic.}}</ref> Part of the return to Spain would require traveling against the wind using an arduous sailing technique called ], during which progress is made very slowly.{{Sfn|Morison|1991|p=132}} To effectively make the return voyage, Columbus would need to follow the curving trade winds northeastward to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where he would be able to catch the "]" that blow eastward to the coast of Western Europe.{{Sfn|Morison|1991|p=314}} | |||

| The navigational technique for travel in the Atlantic appears to have been exploited first by the Portuguese, who referred to it as the '']'' ('turn of the sea'). Through his marriage to his first wife, Felipa Perestrello, Columbus had access to the nautical charts and logs that had belonged to her deceased father, ], who had served as a captain in the Portuguese navy under ]. In the mapmaking shop where he worked with his brother Bartholomew, Columbus also had ample opportunity to hear the stories of old seamen about their voyages to the western seas,<ref name="Rickey1992">{{cite journal |last1=Rickey |first1=V. Frederick |title=How Columbus Encountered America |journal=Mathematics Magazine |date=1992 |volume=65 |issue=4 |pages=219–225 |doi=10.2307/2691445 |jstor=2691445 |issn=0025-570X}}</ref> but his knowledge of the Atlantic wind patterns was still imperfect at the time of his first voyage. By sailing due west from the Canary Islands during ], skirting the so-called ] of the mid-Atlantic, he risked being becalmed and running into a ], both of which he avoided by chance.{{sfn|Morison|1991|pp=198–199}} | |||

| === Quest for financial support for a voyage === | |||

| ], 17th century]] | |||

| By about 1484, Columbus proposed his planned voyage to King ].<ref name="Rickey1992224">{{cite journal |last1=Rickey |first1=V. Frederick |title=How Columbus Encountered America |journal=Mathematics Magazine |date=1992 |volume=65 |issue=4 |page=224 |doi=10.2307/2691445 |jstor=2691445 |issn=0025-570X}}</ref> The king submitted Columbus's proposal to his advisors, who rejected it, correctly, on the grounds that Columbus's estimate for a voyage of 2,400 nmi was only a quarter of what it should have been.{{sfn|Morison|1991|pp=68–70}} In 1488, Columbus again appealed to the court of Portugal, and John II again granted him an audience. That meeting also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards ] returned to Portugal with news of his successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa (near the ]).<ref name="Pinheiro-Marques2016">{{cite book |last1=Pinheiro-Marques |first1=Alfredo |editor1-last=Bedini |editor1-first=Silvio A. |title=The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-349-12573-9 |page=97 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=gmmMCwAAQBAJ&pg=PA97 |language=en |chapter=Diogo Cão}}</ref><ref name="SymcoxSullivan2016">{{cite book |last1=Symcox |first1=Geoffrey |last2=Sullivan |first2=Blair |title=Christopher Columbus and the Enterprise of the Indies: A Brief History with Documents |year=2016 |publisher=Springer |isbn=978-1-137-08059-2 |pages=11–12 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qVEBDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA11 |language=en |quote= in 1488 Columbus returned to Portugal and once again put his project to João II. Again it was rejected. In historical hindsight this looks like a fatally missed opportunity for the Portuguese crown, but the king had good reason not to accept Columbus's project. His panel of experts cast grave doubts on the assumptions behind it, noting that Columbus had underestimated the distance to China. And then in December 1488 Bartolomeu Dias returned from his voyage around the Cape of Good Hope. Certain now that they had found the sea route to India and the east, João II and his advisers had no further interest in what probably seemed to them a hare-brained and risky plan.}}</ref> | |||

| ], in which Columbus stayed in the years before his first expedition]] | |||

| Columbus sought an audience with the monarchs ] and ], who had united several kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula by marrying and now ruled together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. The learned men of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, replied that Columbus had grossly underestimated the distance to Asia. They pronounced the idea impractical and advised the Catholic Monarchs to pass on the proposed venture. To keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the sovereigns gave him an allowance, totaling about 14,000 '']'' for the year, or about the annual salary of a sailor.{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|p=84}} In May 1489, the queen sent him another 10,000 ''maravedis'', and the same year the monarchs furnished him with a letter ordering all cities and towns under their dominion to provide him food and lodging at no cost.<ref>Durant, Will ''The Story of Civilization'' vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, p. 260.</ref> | |||

| Columbus also dispatched his brother ] to the court of ] to inquire whether the English crown might sponsor his expedition, but he was captured by pirates en route, and only arrived in early 1491.{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|pp=86, 92}} By that time, Columbus had retreated to ], where the Spanish crown sent him 20,000 ''maravedis'' to buy new clothes and instructions to return to the ] for renewed discussions.{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|p=92}} | |||

| === Agreement with the Spanish crown === | |||

| ], where Columbus received permission from the ] for his first voyage<ref>{{Cite web|last=Morrison|first=Geoffrey|date=15 October 2015|title=Exploring The Alhambra Palace And Fortress In Granada, Spain|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/geoffreymorrison/2015/10/15/exploring-the-alhambra-palace-granada-spain/|url-status=live|access-date=24 May 2021|website=Forbes|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151016073235/http://www.forbes.com/sites/geoffreymorrison/2015/10/15/exploring-the-alhambra-palace-granada-spain/ |archive-date=16 October 2015 }}</ref>]] | |||

| Columbus waited at King Ferdinand's camp until Ferdinand and Isabella conquered ], the ] on the Iberian Peninsula, in January 1492. A council led by Isabella's confessor, ], found Columbus's proposal to reach the Indies implausible. Columbus had left for France when Ferdinand intervened,{{Efn|Ferdinand later claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered."{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|pp=131–132}}}} first sending Talavera and Bishop ] to appeal to the queen.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|pp=131–32}} Isabella was finally convinced by the king's clerk ], who argued that Columbus would take his ideas elsewhere, and offered to help arrange the funding. Isabella then sent a royal guard to fetch Columbus, who had traveled 2 leagues (over 10 km) toward Córdoba.{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|pp=131–132}} | |||

| In the April 1492 "]", King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella promised Columbus that if he succeeded he would be given the rank of ''Admiral of the Ocean Sea'' and appointed ] and Governor of all the new lands he might claim for Spain.<ref name="Lantigua2020">{{cite book |last1=Lantigua |first1=David M. |title=Infidels and Empires in a New World Order: Early Modern Spanish Contributions to International Legal Thought |date=2020 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-108-49826-5 |page=53 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9RzhDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA53 |language=en |quote=The ''Capitulaciones de Santa Fe'' appointed Columbus as the official viceroy of the Crown, which entitled him, by virtue of royal concession, to all the honors and jurisdictions accorded the conquerors of the Canaries. Usage of the terms "to discover" (''descubrir'') and "to acquire" (''ganar'') were legal cues indicating the goals of Spanish possession through occupancy and conquest.}}</ref> He had the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands. He would be entitled to 10% ('']'') of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity. He also would have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture in the new lands, and receive one-eighth (''ochavo'') of the profits.{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=662}}<ref name="González-Sánchez2006">{{cite book |last1=González Sánchez |first1=Carlos Alberto |editor1-last=Kaufman |editor1-first=Will |editor2-last=Francis |editor2-first=John Michael |title=Iberia and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia |year=2006 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-85109-421-9 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OMNoS-g1h8cC&pg=PA175 |chapter=Capitulations of Santa Fe |pages=175–176 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://armada.defensa.gob.es/archivo/mardigitalrevistas/cuadernosihcn/50cuaderno/cap02.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/https://armada.defensa.gob.es/archivo/mardigitalrevistas/cuadernosihcn/50cuaderno/cap02.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live|title=Cristóbal Colón en presencia de la muerte (1505–1506)|first=Mario Hernández|last=Sánchez-Barba|journal=Cuadernos Monográficos del Instituto de Historia y Cultural Naval|issue=50|location=Madrid|year=2006|page=51}}</ref> | |||

| In 1500, during his third voyage to the Americas, Columbus was arrested and dismissed from his posts. He and his sons, Diego and Fernando, then conducted a lengthy series of court cases against the Castilian crown, known as the '']'', alleging that the Crown had illegally reneged on its contractual obligations to Columbus and his heirs.<ref name="Márquez1982">{{cite book |last1=Márquez |first1=Luis Arranz |title=Don Diego Colón, almirante, virrey y gobernador de las Indias |date=1982 |publisher=Editorial CSIC – CSIC Press |isbn=978-84-00-05156-3 |page=175, note 4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kRhygUNmg4UC&pg=PA175 |language=es}}</ref> The Columbus family had some success in their first litigation, as a judgment of 1511 confirmed Diego's position as viceroy but reduced his powers. Diego resumed litigation in 1512, which lasted until 1536, and further disputes initiated by heirs continued until 1790.<ref name="McDonald2005" /> | |||

| == Voyages == | |||

| {{Main|Voyages of Christopher Columbus}} | {{Main|Voyages of Christopher Columbus}} | ||

| {{See also|#Legacy|Christopher Columbus Copy Book}} | |||

| ===Navigation plans=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] workshop of Bartolomeo and Christopher Columbus<ref>"Marco Polo et le Livre des Merveilles", ISBN 9782354040079 p.37</ref>]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Europe had long enjoyed a safe land passage to China and India— sources of valued ] such as ], ], and ]— under the ] of the ] (the ], or ''Mongol peace''). With the ] to the ] in 1453, the land route to Asia became more difficult. In response to this the Columbus brothers had, by the 1480s, developed a plan to travel to the Indies, then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia, by sailing directly west across the "]," ''i.e.,'' the Atlantic. | |||

| Between 1492 and 1504, Columbus completed four round-trip voyages between Spain and the ], each voyage being sponsored by the ]. On his first voyage he reached the Americas, initiating the European ] and ], as well as the ]. His role in history is thus important to the ], ], and ] writ large.<ref name="SpechtStockland2017">{{cite book |last1=Specht |first1=Joshua |last2=Stockland |first2=Etienne |title=The Columbian Exchange |date=2017 |publisher=CRC Press |isbn=978-1-351-35121-8 |page=23 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wkkrDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ]'s 1828 biography of Columbus popularized the idea that Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan because Europeans thought ].<ref name=book3>{{cite book | first=Paul F|last=Boller | title=Not So!:Popular Myths about America from Columbus to Clinton | year=1995 | isbn=9780195091861 | publisher=Oxford University Press | location=New York}}</ref> In fact, the primitive maritime navigation of the time relied on the stars and the curvature of the ]. The knowledge that the Earth was spherical was widespread, and the means of calculating its diameter using an ] was known to both scholars and navigators.<ref>Russell, Jeffrey Burton 1991. ''Inventing the Flat Earth. Columbus and modern historians'', Praeger, New York, Westport, London 1991;<br />Zinn, Howard 1980. ''A People's History of the United States'', HarperCollins 2001. p.2</ref> A spherical Earth had been the general opinion of Ancient Greek science, and this view continued through the Middle Ages (for example, ] mentions it in ''The Reckoning of Time''). In fact ] had measured the diameter of the Earth with good precision in the second century BC.<ref name = "Sagan 40,04147">Sagan, Carl. ''Cosmos''; the mean circumference of the Earth is 40,041.47 km.</ref> Where Columbus did differ from the generally accepted view of his time is his (incorrect) arguments that assumed a significantly smaller diameter for the Earth, claiming that Asia could be easily reached by sailing west across the Atlantic. Most scholars accepted ]'s correct assessment that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 ] of the terrestrial sphere, and dismissed Columbus's claim that the Earth was much smaller, and that Asia was only a few thousand nautical miles to the west of Europe. Columbus's error was put down to his lack of experience in navigation at sea.<ref name = "Morison-Admiral"> Morison, Samuel Eliot, ''Admiral of the Ocean Sea: The Life of Christopher Columbus'' Boston, 1942</ref> | |||

| In ], published following his first return to Spain, he claimed that he had reached Asia,{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=381}} as previously described by Marco Polo and other Europeans. Over his subsequent voyages, Columbus refused to acknowledge that the lands he visited and claimed for Spain were not part of Asia, in the face of mounting evidence to the contrary.<ref name="Horodowich2017">{{cite book|last1=Horodowich|first1=Elizabeth|title=The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492–1750|publisher=Cambridge University Press|year=2017|isbn=978-1-108-50923-7|editor1-last=Horodowich|editor1-first=Elizabeth|page=23|language=en|chapter=Italy and the New World|editor2-last=Markey|editor2-first=Lia|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8q5CDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA23}}</ref> This might explain, in part, why the American continent was named after the ] explorer ]—who received credit for recognizing it as a "]"—and not after Columbus.<ref name=umc>{{cite web|last=Cohen|first=Jonathan|url=http://www.umc.sunysb.edu/surgery/america.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029201227/http://www.umc.sunysb.edu/surgery/america.html|archive-date=29 October 2013|title=The Naming of America|publisher=Umc.sunysb.edu|access-date=10 April 2011}}</ref>{{Efn|name=incognita|] points out that Columbus briefly described South America as an unknown continent after seeing the mainland for the first time. Vespucci seems to have modeled his naming of the "new world" after Columbus's description of this discovery. Further, mapmaker ] eventually retracted his naming of the continent after Vespucci, seemingly after it came to light that a claim that Vespucci visited the mainland before Columbus had been falsified. In his new map, Waldseemüller labelled the continent as ''Terra Incognita'' ('unknown land'), noting that it had been discovered by Columbus.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Fernández-Armesto|first=Felipe|title=Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America|publisher=Random House|year=2007|isbn=978-1-4000-6281-2 |edition=1st|location=New York|pages=143–144, 186–187|oclc=608082366}}</ref>}} | |||

| Columbus believed the (incorrect) calculations of ], putting the landmass at 225 degrees, leaving only 135 degrees of water. Moreover, Columbus believed that one degree represented a shorter distance on the Earth's surface than was actually the case. Finally, he read maps as if the distances were calculated in ] (1,238 meters<!--Shouldn't it be 1,520 m-->). Accepting the length of a degree to be 56⅔ miles, from the writings of ], he therefore calculated the circumference of the Earth as 25,255 kilometers at most, and the distance from the ] to Japan as 3,000 Italian miles (3,700 km, or 2,300 statute miles). Columbus did not realize Alfraganus used the much longer Arabic mile (about 1,830 m). | |||

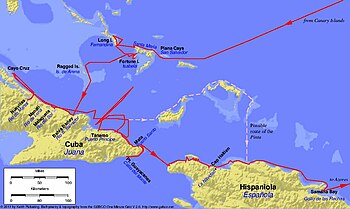

| === First voyage (1492–1493) === | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| ].<ref>{{cite journal |url=http://www.dioi.org/vols/w41.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.dioi.org/vols/w41.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live |first=Keith A. |last=Pickering |title=Columbus's Plana landfall: Evidence for the Plana Cays as Columbus's 'San Salvador' |journal=DIO – the International Journal of Scientific History |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=13–32 |date=August 1994 |access-date=16 March 2009}}</ref> ] by ] to be the most likely location of first contact{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=228}} is the easternmost land touching the top edge of this image.|name=firstimage}} Modern place names in black, Columbus's place names in blue]] | |||

| The true circumference of the Earth is about 40,000 km (25,000 mi), a figure established by ] in the second century BC,<ref name = "Sagan 40,04147"/> and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan 19,600 km (12,200 mi). No ship that was readily available in the 15th century could carry enough food and fresh water for such a journey. Most European sailors and navigators concluded, probably correctly, that sailors undertaking a westward voyage from Europe to Asia non-stop would die of thirst or starvation long before reaching their destination. Spain, however, having completed ], was desperate for a competitive edge over other European countries in trade with the East Indies. Columbus promised such an advantage. | |||

| On the evening of 3 August 1492, Columbus departed from ] with three ships. The largest was a ], the '']'', owned and captained by ], and under Columbus's direct command.{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|p=102}} The other two were smaller ]s, the '']'' and the '']'',<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.thenina.com/the_original_nina.html |title=The Original Niña |website=The Niña & Pinta |publisher=The Columbus Foundation |location=British Virgin Islands |access-date=12 October 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150526034248/http://www.thenina.com/the_original_nina.html |archive-date=26 May 2015}}</ref> piloted by the ].{{Sfn|Dyson|1991|p=102}} Columbus first sailed to the Canary Islands. There he restocked provisions and made repairs then departed from ] on 6 September,{{sfn|Phillips|Phillips|1992|pp=146–147}} for what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean. | |||

| While Columbus's calculations underestimated the circumference of the Earth and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan by the standards of his peers as well as in fact, Europeans generally assumed that the aquatic expanse between Europe and Asia was uninterrupted.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} | |||

| On 7 October, the crew spotted "mmense flocks of birds".<ref name="Nicholls2009">{{Cite book |last=Nicholls |first=Steve |title=Paradise Found: Nature in America at the Time of Discovery |pages= |publisher=University of Chicago Press |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-226-58340-2 |url=https://archive.org/details/paradisefoundnat00stev/page/103}}</ref> On 11 October, Columbus changed the fleet's course to due west, and sailed through the night, believing land was soon to be found. At around 02:00 the following morning, a lookout on the ''Pinta'', ], spotted land. The captain of the ''Pinta'', ], verified the sight of land and alerted Columbus.{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=226}}<ref>Lopez, (], ); Columbus & Toscanelli (], )</ref> Columbus later maintained that he had already seen a light on the land a few hours earlier, thereby claiming for himself the lifetime pension promised by Ferdinand and Isabella to the first person to sight land.{{sfn|Murphy|Coye|2013}}<ref>Lopez, (], )</ref> Columbus called this island (in what is now the Bahamas) {{lang|es|San Salvador}} ('Holy Savior'); ] called it ].{{Sfn|Bergreen|2011|ref=none|p=99}}{{Efn|According to ], ], renamed from Watling's Island in 1925 in the belief that it was Columbus's San Salvador,<ref>William D. Phillips Jr., 'Columbus, Christopher', in David Buisseret (ed.), ''The Oxford Companion to World Exploration'', (Oxford University Press, online edition 2012).</ref> is the only island fitting the position indicated by Columbus's journal. Other candidates are the ], ], ], ], or ].{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=228}}}} ] entry of 12 October 1492 states:<blockquote>I saw some who had marks of wounds on their bodies and I made signs to them asking what they were; and they showed me how people from other islands nearby came there and tried to take them, and how they defended themselves; and I believed and believe that they come here from {{lang|es|tierra firme}} to take them captive. They should be good and intelligent servants, for I see that they say very quickly everything that is said to them; and I believe they would become Christians very easily, for it seemed to me that they had no religion. Our Lord pleasing, at the time of my departure I will take six of them from here to Your Highnesses in order that they may learn to speak.<ref name="DunnKelly1989">{{cite book |last1=Dunn |first1=Oliver |last2=Kelley |first2=James E. Jr. |title=The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America, 1492–1493 |year=1989 |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |isbn=978-0-8061-2384-4 |pages=67–69 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nS6kRnXJgCEC&pg=PA67}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| There was a further element of key importance in the plans of Columbus, a closely held fact discovered, or otherwise learned, by Columbus: the ]. A brisk wind from the east, commonly called an "]", propelled '']'', '']'', and '']'' for five weeks from the Canaries. To return to Spain eastward against this prevailing wind would have required several months of an arduous sailing technique, called ], during which food and drinkable water would have been utterly exhausted. Columbus returned home by following prevailing winds northeastward from the southern zone of the North Atlantic to the middle latitudes of the North Atlantic, where prevailing winds are eastward (westerly) to the coastlines of Western Europe, where the winds curve southward towards the Iberian Peninsula.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.columbusnavigation.com/v1a.shtml|title=The First Voyage Log | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-04-18}} | |||

| </ref> In fact, Columbus was wrong about degrees of longitude to be traversed and wrong about distance per degree, but he was right about a more vital fact: how to use the North Atlantic's great circular wind pattern, clockwise in direction, to get home.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ucalgary.ca/applied_history/tutor/eurvoya/columbus.html|title=Christopher Columbus and the Spanish Empire | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-04-18 }} | |||

| </ref><ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://earthguide.ucsd.edu/virtualmuseum/climatechange1/08_1.shtml|title=Trade Winds and the Hadley Cell | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-04-18 }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Columbus called the inhabitants of the lands that he visited {{lang|es|Los Indios}} (Spanish for 'Indians').<ref name="Hoxie 1996 p.">{{cite book |last=Hoxie |first=Frederick |url=https://archive.org/details/encyclopediaofno00hoxi/page/568 |title=Encyclopedia of North American Indians |publisher=Houghton Mifflin |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-395-66921-1 |location=Boston |page=}}</ref> He initially encountered the ], ], and ] peoples.<ref name="Keegan2015">{{cite journal |last1=Keegan |first1=William F. |title=Mobility and Disdain: Columbus and Cannibals in the Land of Cotton |journal=Ethnohistory |year=2015 |volume=62 |issue=1 |pages=1–15 |doi=10.1215/00141801-2821644 |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273291078}}</ref> Noting their gold ear ornaments, Columbus took some of the Arawaks prisoner and insisted that they guide him to the source of the gold.<ref name=Zinn>{{harvnb|Zinn|2003|pp=}}</ref> Columbus did not believe he needed to create a fortified outpost, writing, "the people here are simple in war-like matters ... I could conquer the whole of them with fifty men, and govern them as I pleased."<ref>Columbus (], ). Or "these people are very simple as regards the use of arms ... for with fifty men they can all be subjugated and made to do what is required of them." (Columbus & Toscanelli, ], )</ref> The Taínos told Columbus that another indigenous tribe, the ], were fierce warriors and ], who made frequent raids on the Taínos, often capturing their women, although this may have been a belief perpetuated by the Spaniards to justify enslaving them.<ref name="Figueredo2008">{{cite book |last1=Figueredo |first1=D. H. |title=A Brief History of the Caribbean |year=2008 |publisher=Infobase |isbn=978-1-4381-0831-5 |page=9 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RsNPdvRtT7oC&pg=PA9}}</ref><ref name="Deagan2008">{{cite book |last1=Deagan |first1=Kathleen A. |title=Columbus's Outpost Among the Taínos: Spain and America at La Isabela, 1493–1498 |year=2008 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-13389-9 |page=32 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iWGZP0V8WroC&pg=PA32}}</ref> | |||

| ===Funding campaign=== | |||

| In 1485, Columbus presented his plans to ], ]. He proposed the king equip three sturdy ships and grant Columbus one year's time to sail out into the Atlantic, search for a western route to the ], and return. Columbus also requested he be made "Great Admiral of the Ocean", appointed governor of any and all lands he discovered, and given one-tenth of all revenue from those lands. The king submitted the proposal to his experts, who rejected it. It was their considered opinion that Columbus's estimation of a travel distance of {{convert|2400|mi|km|-1}} was, in fact, far too short.<ref name = "Morison-Admiral"/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba, where he landed on 28 October. On the night of 26 November, Martín Alonso Pinzón took the ''Pinta'' on an unauthorized expedition in search of an island called "Babeque" or "Baneque",<ref name="Hunter2012">{{cite book |last1=Hunter |first1=Douglas |title=The Race to the New World: Christopher Columbus, John Cabot, and a Lost History of Discovery |year=2012 |publisher=Macmillan |isbn=978-0-230-34165-4 |page=62 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fYrvCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA62}}</ref> which the natives had told him was rich in gold.<ref name="Magasich-AirolaBeer2007">{{cite book |last1=Magasich-Airola |first1=Jorge |last2=Beer |first2=Jean-Marc de |title=America Magica: When Renaissance Europe Thought It Had Conquered Paradise |edition=2nd |year=2007 |publisher=Anthem |isbn=978-1-84331-292-5 |page=61 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SauW0UOVcp0C&pg=PA61}}</ref> Columbus, for his part, continued to the northern coast of ], where he landed on 6 December.<ref name="Anderson-Córdova2017">{{cite book |last1=Anderson-Córdova |first1=Karen F. |title=Surviving Spanish Conquest: Indian Fight, Flight, and Cultural Transformation in Hispaniola and Puerto Rico |year=2017 |publisher=University of Alabama Press |isbn=978-0-8173-1946-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RNoZDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA55 |page=55}}</ref> There, the ''Santa María'' ran aground on 25 December 1492 and had to be abandoned. The wreck was used as a target for cannon fire to impress the native peoples.{{sfn|Murphy|Coye|2013|pp=31–32}} Columbus was received by the native '']'' ], who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus left 39 men, including the interpreter ],{{Sfn|Morison|1991|p=145}}{{Efn|Torres spoke ] and some ]; the latter was then believed to be the ] of all languages.{{sfn|Morison|1991|p=145}}}} and founded the settlement of ], in present-day ].<ref name="DeaganCruxent1993">{{cite journal |last1=Deagan |first1=Kathleen |last2=Cruxent |first2=José Maria |author1-link=Kathleen Deagan |author2-link=José Cruxent |title=From Contact to Criollos: The Archaeology of Spanish Colonization in Hispaniola |journal=Proceedings of the British Academy |date=1993 |volume=81 |page=73 |url=http://publications.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/pubs/proc/files/81p067.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://publications.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/pubs/proc/files/81p067.pdf |archive-date=9 October 2022 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Maclean2008">{{cite magazine |last=Maclean |first=Frances |title=The Lost Fort of Columbus |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-lost-fort-of-columbus-8026921/ |magazine=] |date=January 2008 |access-date=24 January 2008}}</ref> Columbus took more natives prisoner and continued his exploration.<ref name=Zinn /> He kept sailing along the northern coast of Hispaniola with a single ship until he encountered Pinzón and the ''Pinta'' on 6 January.<ref name="Gužauskytė2014">{{cite book |last1=Gužauskytė |first1=Evelina |title=Christopher Columbus's Naming in the 'diarios' of the Four Voyages (1492–1504): A Discourse of Negotiation |year=2014 |publisher=University of Toronto Press |isbn=978-1-4426-6825-6 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U0SWAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA96 |page=96}}</ref> | |||

| In 1488 Columbus appealed to the court of Portugal once again, and once again John invited him to an audience. It also proved unsuccessful, in part because not long afterwards ] returned to Portugal following a successful rounding of the southern tip of Africa. With an eastern sea route now under its control, Portugal was no longer interested in trailblazing a western route to Asia. | |||

| On 13 January 1493, Columbus made his last stop of this voyage in the Americas, in the ] in northeast Hispaniola.<ref>Fuson, Robert. ''The Log of Christopher Columbus'' (Camden, International Marine, 1987) 173.</ref> There he encountered the ], the only natives who offered violent resistance during this voyage.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lTsLAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA33 |title=Confronting Columbus: An Anthology |publisher=McFarland & Co. |last=Yewell |first=John |first2=Chris |last2=Dodge |year=1992 |location=Jefferson, NC |page=33 |isbn=978-0-89950-696-8 |access-date=28 February 2016}}</ref> The Ciguayos refused to trade the amount of bows and arrows that Columbus desired; in the ensuing clash one Ciguayo was stabbed in the buttocks and another wounded with an arrow in his chest.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XwI7AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA159 |title=The Journal of Christopher Columbus |publisher=Hakluyt Society |last=Markham |first=Clements R. |year=1893 |location=London |pages=159–160 |access-date=28 February 2016}}</ref> Because of these events, Columbus called the inlet the {{lang|es|Golfo de Las Flechas}} (']').<ref name="DunnKelly1989341">{{cite book |last1=Dunn |first1=Oliver |last2=Kelley |first2=James E. Jr. |title=The Diario of Christopher Columbus's First Voyage to America, 1492–1493 |year=1989 |publisher=University of Oklahoma Press |isbn=978-0-8061-2384-4 |page=341 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nS6kRnXJgCEC&pg=PA341}}</ref> | |||

| Columbus travelled from Portugal to both ] and ], but he received encouragement from neither. Previously he had his brother sound out ], to see if the ] might not be more amenable to Columbus's proposal. After much carefully considered hesitation Henry's invitation came, too late. Columbus had already committed himself to Spain. | |||

| ] (1885).]] | |||

| Columbus headed for Spain on the ''Niña'', but a storm separated him from the ''Pinta'', and forced the ''Niña'' to stop at the island of Santa Maria in the Azores. Half of his crew went ashore to say prayers of thanksgiving in a chapel for having survived the storm. But while praying, they were imprisoned by the governor of the island, ostensibly on suspicion of being pirates. After a two-day stand-off, the prisoners were released, and Columbus again set sail for Spain.<ref name="Catz1990">{{Cite journal |title=Columbus in the Azores |jstor=41104900 |journal=Portuguese Studies |date=1990 |pages=19–21 |volume=6 |first=Rebecca |last=Catz}}</ref> | |||

| He had sought an audience from the monarchs ] of ] and ] of ], who had united the largest kingdoms of Spain by marrying, and were ruling together. On 1 May 1486, permission having been granted, Columbus presented his plans to Queen Isabella, who, in turn, referred it to a committee. After the passing of much time, these savants of Spain, like their counterparts in Portugal, reported back that Columbus had judged the distance to Asia much too short. They pronounced the idea impractical, and advised their Royal Highnesses to pass on the proposed venture. | |||

| Another storm forced Columbus into the port at Lisbon.{{sfn|Murphy|Coye|2013|p=}} From there he went to {{lang|pt|Vale do Paraíso}} north of Lisbon to meet King John II of Portugal, who told Columbus that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 ]. After spending more than a week in Portugal, Columbus set sail for Spain. Returning to Palos on 15 March 1493, he was given a hero's welcome and soon afterward received by Isabella and Ferdinand in Barcelona.<ref name="Kamen2014">{{cite book |last1=Kamen |first1=Henry |title=Spain, 1469–1714: A Society of Conflict |date=2014 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-317-75500-5 |page=51 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=akIsAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA51}}</ref> To them he presented kidnapped Taínos and various plants and items he had collected.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fernández-Armesto |first=Felipe |author-link=Felipe Fernández-Armesto |url=https://archive.org/details/amerigomanwhogav0000fern |title=Amerigo: The Man Who Gave His Name to America |publisher=Random House |year=2007 |isbn=978-1-4000-6281-2 |location=New York}}</ref>{{rp|54}} | |||

| However, to keep Columbus from taking his ideas elsewhere, and perhaps to keep their options open, the King and Queen of Spain gave him an annual allowance of 12,000 '']'' and in 1489 furnished him with a letter ordering all Spanish cities and towns to provide him food and lodging at no cost.<ref>Durant, Will ''"The Story of Civilization"'' vol. vi, "The Reformation". Chapter XIII, page 260.</ref> | |||