| Revision as of 20:18, 17 December 2005 editWsiegmund (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers12,339 edits →Climate: Changed descripton of cooling mechanism. See talk page.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:12, 14 January 2025 edit undoSusanLesch (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers69,069 edits →Human history: new section | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|National Forest in Wyoming, US}} | |||

| {{Infobox_protected_area | name = Shoshone National Forest | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2013}} | |||

| | iucn_category = VI | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| | image = US_Locator_Blank.svg | |||

| {{Infobox protected area | |||

| | caption = | |||

| | name = Shoshone National Forest | |||

| | locator_x = 80 | |||

| | iucn_category = VI | |||

| | photo = Francs Peak.jpg | |||

| | location = ], ] | |||

| | photo_caption = ] is the tallest peak in the Absaroka Range | |||

| | nearest_city = ] | |||

| | map = Wyoming#USA | |||

| | lat_degrees = 44 | |||

| | relief = 1 | |||

| | map_caption = Location of Shoshone National Forest | |||

| | lat_seconds = 33 | |||

| | location = ], ], ], ], and ] counties, ], US | |||

| | lat_direction = N | |||

| | nearest_city = ] | |||

| | long_degrees = 109 | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|44|27|48|N|109|36|55|W|region:US-WY|display=inline,title|name=New Wapiti Ranger Station}} | |||

| | long_minutes = 32 | |||

| | area_acre = 2,469,248 | |||

| | long_seconds =33 | |||

| | area_ref = <ref name=acreage>{{cite web |title=Land Areas of the National Forest System |url=https://www.fs.usda.gov/land/staff/lar/LAR2021/LARTable28.pdf |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |access-date=June 13, 2023 |date=January 1, 2020 |archive-date=June 14, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230614022920/https://www.fs.usda.gov/land/staff/lar/LAR2021/LARTable28.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| | long_direction = W | |||

| | established = March 3, 1891 | |||

| | area = 2,466,586 acres (9,982 km²) | |||

| | visitation_num = | |||

| | established = ], ] | |||

| | visitation_year = | |||

| | visitation_num = 617,000 | |||

| | governing_body = ] | |||

| | visitation_year = ] | |||

| | website = | |||

| | governing_body = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

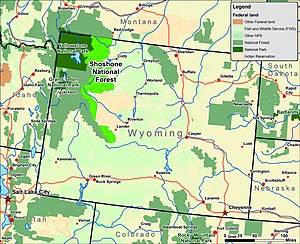

| '''Shoshone National Forest''' ({{IPAc-en|ʃ|oʊ|ˈ|ʃ|oʊ|n|i}} {{Respell|shoh|SHOH|nee}})<ref>{{cite web |title=Shoshone |url=http://www.answers.com/topic/shoshone |publisher=Answers |access-date=March 23, 2013 |archive-date=March 3, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303170801/http://www.answers.com/topic/shoshone |url-status=live }}</ref> is the first ] protected ] in the United States and covers nearly {{convert|2500000|acre}} in the ] of ].<ref name=shoshone>{{cite web |title=Welcome to Shoshone National Forest |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/shoshone |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=October 25, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121025114306/http://www.fs.usda.gov/shoshone |url-status=live }}</ref> Originally a part of the ], the forest is managed by the ] and was created by an act of ] and signed into law by ] ] in 1891. Shoshone National Forest is one of the first nationally protected land areas anywhere. ]s have lived in the region for at least 10,000 years, and when the region was first explored by European adventurers, forestlands were occupied by several different tribes. Never heavily settled or exploited, the forest has retained most of its wildness. Shoshone National Forest is a part of the ], a nearly unbroken expanse of federally protected lands encompassing an estimated {{convert|20000000|acre}}. | |||

| Spanning 2.4 million acres (9,700 km²) in the ] of ], '''Shoshone National Forest''' is the first federally protected forest in the ], first protected by ] as the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve in ]. A total of four ] areas are located within the forest ensuring that more than half the forest will never be developed or altered by human activities. From ] plains through dense ] and ] forest to craggy mountain peaks, the Shoshone National Forest has a rich ] rarely matched in any protected area. | |||

| The ] and ] are partly in the northern section of the forest. The ] is in the southern portion and contains ], the tallest mountain in Wyoming.<ref name=shoshone/> ] forms part of the boundary to the west; south of Yellowstone, the ] separates the forest from its neighbor ] to the west. The eastern boundary includes privately owned property, lands managed by the U.S. ] and the ], which belongs to the ] and ] Indians. ] along the ] border is on the northern frontier. The ], the 19th century ] route, passes just south of the forest, where broad and gentle ] allowed the migrants to bypass the rugged mountains to the north. | |||

| Shoshone National Forest has virtually all the original animal and plant species that were there when explorers such as ] and ] first visited the region. The forest is home to the ], ], ], tens of thousands of ] as well as the largest population of ] in the contiguous U.S. The streams in the forest are considered to have some of the best game species fishing opportunities in the U.S. including ]. More than {{convert|1300|mi}} of hiking trails, 32 campgrounds and adjacent forests and parklands provide numerous recreational opportunities. There are four ] areas within the forest, protecting more than half of the ] area from development. From ] plains through dense ] and ] forest to craggy mountain peaks, Shoshone National Forest has a rich ] rarely matched in any protected area. | |||

| All of the forest is a part of the ], an unbroken expanse of ] protected lands encompassing an estimated 20 million acres (80,937 km²). The forest is now managed by the ] under authority of the ]. | |||

| == Forest uses == | |||

| ] | |||

| As is true with all National Forests in the U.S., in Shoshone National Forest the emphasis is on ] rather than ] as is commonly practiced by the ]. The Forest Service mandate is to ensure a sustainable flow of some raw materials from the forest such as ] for construction purposes and ] for paper products. Mineral ] and ] and ] exploration and recovery are also conducted, though are much more uncommon and with increasing rarity. On suitable lands, lease options are offered to ] to allow them to graze livestock such as ] and ]. The forest provides guidelines and enforces environmental regulations to ensure that resources are not overexploited and to ensure necessary commodities are available for future populations. An increasing effort by conservationist groups combined with public demand led to the creation of ] designated zones within most National Forests which provides a much higher level of protection and prohibits any alterations to the resource. In Shosone National Forest, less than ten percent of the total acreage is utilized for land lease, ] or mineral extraction. The rest of the forest is either designated wilderness, reserved for habitat protection for plants and animals, or set aside for visitor recreation. The forest is separated into seven districts and the main headquarters is located in ]. | |||

| == Human history == | == Human history == | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Shoshone National Forest is named after the ], who, along with other ] groups such as the ], ] and ], were the |

Shoshone National Forest is named after the ], who, along with other ] groups such as the ], ] and ], were the major tribes encountered by the first European explorers into the region. ] evidence suggests that the presence of Indian tribes in the area extends back at least 10,000 years.<ref name=history>{{cite web |title=History and Culture |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/shoshone/learning/history-culture |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=May 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518080213/http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/shoshone/learning/history-culture |url-status=live }}</ref> The forest provided an abundance of game meat, wood products, and shelter during the winter months from the more exposed ] to the east. Portions of the more mountainous regions were frequented by the Shoshone and Sioux for spiritual healing and ]s. By the early 1840s, ] had become the leader of the easternmost branch of the Shoshone Indians.{{sfn|Hebard|1995|p=56}} At the ] Washakie negotiated with the U.S. Government for {{convert|44000000|acre}}) to be preserved as tribal lands. Subsequent amendments to the treaty reduced the actual acreage to approximately {{convert|2000000|acre}} and is known today as the ].{{sfn|Capace|2007|p=88}}{{sfn|Johansen|Pritzker|2007|p=1127}} | ||

| In 1957, ] was rediscovered by a local resident on the north side of the North Fork Shoshone River, adjacent to U.S. Routes ]/]/], {{cvt|15|mi}} east of Yellowstone National Park.<ref name=mummy>{{cite web |title=Mummy Cave |url=http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/NationalRegister/Site.aspx?ID=324 |publisher=Wyoming State Historic Preservation Office |access-date=September 29, 2013 |archive-date=June 15, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110615162344/http://wyoshpo.state.wy.us/NationalRegister/Site.aspx?ID=324 |url-status=dead }}</ref> Subsequent archeological excavations in the 1960s produced evidence that the cave had been occupied for over 9,000 years.<ref name=husted>{{cite web |last=Husted |first=Wilfred M. |author2=Robert Edgar |title=The Archeology of Mummy Cave, Wyoming: An Introduction to Shoshonean Prehistory |url=http://www.nps.gov/history/mwac/publications/pdf/spec4.pdf |publisher=National Park Service |year=2002 |access-date=September 29, 2013 |archive-date=September 2, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090902101958/http://www.nps.gov/history/mwac/publications/pdf/spec4.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The oldest deposits in the cave yielded ] and other artifacts created by paleoindians and the surrounding soils were ] to 7,300 BC. The evidence indicates the cave was occupied from at least 7280 BC to 1580 AD.<ref name=mummy/> Besides projectile points, the cave also produced well preserved feathers, animal hides and other usually perishable materials. Additionally, the mummified remains of an individual buried inside a rock ] were unearthed, which were dated to 800 AD.<ref name=husted/> Considered one of the finest paleoindian archeological assemblages in the Rocky Mountain region, the site was placed on the ] list in 1981.<ref name=nris>{{NRISref|version=2010a}}</ref> | |||

| In the early 1800s, the forest was visited by ] and explorers such as ] and ]. Colter is the first white man known to have visited both the Yellowstone region and the forest in the period between 1806 and 1808. Having been an original member of the ], Colter requested permission from ] to leave the expedition after it had finished crossing the ] during their return journey from the ]. Colter teamed up with two unaffiliated explorers the expedition had encountered but soon thereafter decided to explore regions south of where his new partners wished to venture. Traveling first into the northeastern region of what is today Yellowstone National Park, Colter then explored the ], crossing over ] and entering the valley known today as ]. Colter survived both a ] attack and pursuit by a band of ] Indians that had taken his horse and striped him naked. Colter later provided ] with previously unknown information of the regions he had explored which were published by Clark in 1814. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the early 19th century, the forest was visited by ] and explorers such as ] and ]. Colter is the first white man known to have visited both the Yellowstone region and the forest, which he did between 1807 and 1808.{{sfn|Utley|2004|pp=15–16}} Having been an original member of the ], Colter requested permission from Meriwether Lewis to leave the expedition after it had finished crossing the ] during their return journey from the Pacific Ocean. Colter teamed up with two unaffiliated explorers the expedition had encountered, but soon thereafter decided to explore regions south of where his new partners wished to venture.{{sfn|Utley|2004|pp=15–16}} Traveling first into the northeastern region of what is today Yellowstone National Park, Colter then explored the ], crossing over ] and entering the valley known today as ].<ref name=daugherty1>{{cite web |last=Daugherty |first=John |title=The Fur Trappers |url=http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/grte2/hrs3.htm |work=A Place Called Jackson Hole |publisher=Grand Teton Natural History Association |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=November 8, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121108182117/http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/grte2/hrs3.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> Colter survived a ] attack and a pursuit by a band of ] Indians who had taken his horse.{{sfn|Utley|2004|pp=15–16}} The explorer later provided William Clark, who had been his commander on the Lewis and Clark Expedition, with previously unknown information on the regions he had explored, which Clark published in 1814.<ref name=burns>{{cite web |last=Burns |first=Ken |title=Private John Colter |url=https://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/inside/jcolt.html |work=Lewis and Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery |publisher=PBS |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=September 20, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180920111416/http://www.pbs.org/lewisandclark/inside/jcolt.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Travels by ] and adventurers such as ] and Jim Bridger from 1807 to 1840, completed the exploration of the region. With the decline of the fur trade in the late |

Travels by ] and adventurers, such as ] and Jim Bridger from 1807 to 1840, completed the exploration of the region. With the decline of the fur trade in the late 1840s and much of the prized ] long since made scarce by over-trapping, few explorers entered the forest over the next few decades.<ref name=daugherty1/> The first federally financed expedition which passed through portions of Shoshone National Forest was the ] of 1860, led by ] Captain ].<ref name=baldwin>{{cite web |last=Baldwin |first=Kenneth H. |title=Terra Incognita: The Raynolds Expedition of 1860 |work=Enchanted Enclosure |publisher=U.S. Army |date=November 15, 2004 |url=http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/baldwin/chap2.htm |access-date=August 31, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121023175338/http://www.cr.nps.gov/history/online_books/baldwin/chap2.htm |archive-date=October 23, 2012}}</ref> The expedition included geologist and naturalist ] and was guided by mountain man Jim Bridger. Though the Raynolds Expedition was focused on exploration of the Yellowstone region, several efforts to enter what later became Yellowstone National Park were impeded by heavy snows across the mountain passes such as ]. The expedition finally crossed the northern Wind River Range at a pass they named ] and entered Jackson Hole valley to the south of Yellowstone.<ref name=baldwin/> Hayden led another expedition through the region in 1871. Hayden was primarily interested in documenting the Yellowstone country west of the forest, but his expedition also established that the forest was a prime resource that merited protection. | ||

| ] | |||

| Prior to the establishment of the Wind River Indian Reservation, the ] constructed Fort Brown on the reservation lands, which was subsequently renamed ].{{sfn|McCoy|2007|pp=152–153}} During the late 19th century, the fort was staffed by ] members of the U.S. Cavalry, better known as the ], including the second African-American graduated from the ], ].{{sfn|Reef|2010|p=6|loc="john hanks alexander fort washakie."}} Chief Washakie is buried at the fort, which is located immediately east of the forest boundary.{{sfn|McCoy|2007|pp=152–153}} Rumor has it that ], the Shoshone Indian who provided invaluable assistance to ] and ] during the Lewis and Clark Expedition, is also buried here, but it is now considered that this is unlikely and that her actual burial place was ] in North Dakota.<ref>{{cite web |title=Burial Sites |url=http://www.nps.gov/jeff/historyculture/burial-sites.htm |work=The Lewis and Clark Journey of Discovery |publisher=National Park Service |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=October 15, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141015083034/http://www.nps.gov/jeff/historyculture/burial-sites.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| During the era of the ] in the 1930s, numerous camps were established by the ] that housed groups of unemployed men paid by the federal government to build roads and ] trails as well as ]s for future travellers to the Yellowstone region. | |||

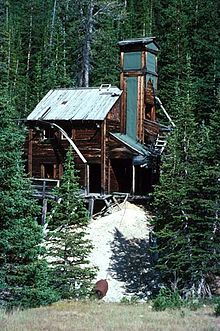

| During the last decade of the 19th century, minerals such as gold were mined with limited success. The last mine was abandoned in 1907, but ] for gold is still allowed in many areas of the forest, and in most circumstances no permit is required.<ref name=kirwin>{{cite web |title=The History of Kirwin |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/learning/kids/?cid=stelprdb5182989 |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=December 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131218122152/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/learning/kids/?cid=stelprdb5182989 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest – FAQs |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/home/?cid=stelprdb5176591 |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=December 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131218123721/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/home/?cid=stelprdb5176591 |url-status=live }}</ref> After the end of the mining era, numerous camps were established by the ] to help combat unemployment during the ] of the 1930s. The camps housed groups of unemployed men who were paid by the federal government to build roads, hiking trails, and campgrounds for future travelers to the Yellowstone region.{{sfn|Otis|1986|pp=24–26}} Visitation to national forests like Shoshone increased dramatically after ] with the advent of better roads and accessibility to the region.{{sfn|Miller|2013|p=138}} | |||

| == Biology == | |||

| ] | |||

| Shoshone National Forest has documented 1,300 distinct ] of ] and ] and new discoveries are found every year. While the lower elevations often have ] and ], the forested sections are dominated by various species of trees, including ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| ==National forest== | |||

| ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ] are just a few of the 100 species of ]s found in the forest. ] and ]s as well as ], ], ] and ] are also found. The lakes and streams are home to 8 species and subspecies of ], some not found anywhere else. | |||

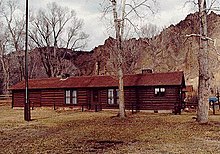

| Travels in the forest in the 1880s by later U.S. President ], who was also a strong advocate of land ], as well as by General ], provided the impetus that subsequently established the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve in 1891, creating the first national forest in the U.S.<ref name=shoshone/><ref>{{cite book |last=Steen |first=Harold K. |title=The beginning of the National Forest System |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |year=1991 |url=https://archive.org/details/beginningofnatio00stee |url-access=registration |page= |quote=yellowstone timberland reserve.}}</ref> In 1902, President Roosevelt first greatly expanded the reserve and then divided the reserve into four separate units, with Shoshone being the largest. Upon the creation of the ] in 1905, the reserve was designated a ], but the current wording and title were formulated forty years later in 1945. A remnant of the earliest years of the forest management is the ] which is located west of ]. The station was built in 1903 and is the oldest surviving ranger station in any national forest, and is now designated a ].<ref>{{cite web |title=Wapiti Ranger Station |work=National Historic Landmarks Program |publisher=National Park Service |url=http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceID=568&resourceType=Building |access-date=August 31, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090520194453/http://tps.cr.nps.gov/nhl/detail.cfm?ResourceID=568&resourceType=Building |archive-date=May 20, 2009 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> | |||

| == Forest management == | |||

| <br clear=all/> | |||

| ] | |||

| Shoshone National Forest is managed by the U.S. Forest Service, an agency within the ]. The forest is separated into five districts and from 2008 and 2012 had an average staff of 165 employees and an annual operating budget of ]17,500,000.<ref name=taylor>{{cite web |last=Taylor |first=David T. |author2=Thomas Foulke |author3=Roger H. Coupal |title=Shoshone National Forest Economic Profile |publisher=University of Wyoming Department of Agricultural & Applied Economics and the U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |date=March 21, 2012 |page=87 |access-date=September 2, 2013 |archive-date=January 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101035220/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The headquarters and a visitor center are in Cody, Wyoming and a smaller information center is in ]. There are local ranger district offices in Cody, ] and Lander.<ref>{{cite web |title=USFS Ranger Districts by State |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.ufwda.org/pdfs/USDAForestServiceRangerDistricts.pdf |access-date=August 31, 2013 |archive-date=January 19, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120119235755/http://www.ufwda.org/pdfs/USDAForestServiceRangerDistricts.pdf |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Shoshone National Forest practices ] of resources, which ensures a sustainable flow of some raw materials from the forest, such as lumber for construction purposes and ] for paper products.<ref name=mission>{{cite web |title=Sustainable Operations |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/sustainableoperations/ |access-date=September 2, 2013 |archive-date=September 17, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130917013604/http://www.fs.fed.us/sustainableoperations/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The forest averages an annual harvest of 4.5 million board-feet of timber for the purposes of commercial log home construction and another 2.5 million board-feet of wood collection from dead and down trees that are used for firewood and poles.<ref name=taylor2>{{cite web |last=Taylor |first=David T. |author2=Thomas Foulke |author3=Roger H. Coupal |title=Shoshone National Forest Economic Profile |publisher=University of Wyoming Department of Agricultural & Applied Economics and the U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |date=March 21, 2012 |page=73 |access-date=September 15, 2013 |archive-date=January 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101035220/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Additionally, low-scale mineral extraction and ] and ] exploration and recovery are also conducted, though in Shoshone National Forest this has become less common due to a consensus to protect the natural surroundings. Only {{cvt|8570|acre}} of oil and gas leases were filed as of 2013.<ref>{{cite web |last=Bleizeffer |first=Dustin |title=Don't count on a rush of drilling rigs in the Shoshone National Forest |publisher=WyoFile |url=http://wyofile.com/dustin/comments-suggest-wyoming-residents-support-conservation-on-shoshone-national-forest/ |date=August 23, 2013 |access-date=September 2, 2013 |archive-date=September 8, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130908034549/http://wyofile.com/dustin/comments-suggest-wyoming-residents-support-conservation-on-shoshone-national-forest/ |url-status=live }}</ref> More common than logging and mining are the lease options that are offered to ranchers to allow them to graze cattle and sheep.<ref name=taylor3>{{cite web |last=Taylor |first=David T. |author2=Thomas Foulke |author3=Roger H. Coupal |title=Shoshone National Forest Economic Profile |publisher=University of Wyoming Department of Agricultural & Applied Economics and the U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |date=March 21, 2012 |page=53 |access-date=September 15, 2013 |archive-date=January 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101035220/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5379182.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The U.S. Forest Service provides guidelines and enforces environmental regulations to ensure that resources are not ] and that necessary commodities are available for future generations, though conservation groups have voiced concerns over the management practices of the leasing program and especially cattle ] problems.<ref name=ws>{{cite web |title=Beartooth Front, Wyoming |work=Too Wild to Drill |publisher=Wilderness Society |url=http://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/legacy/TWTD-WY-Beartooth.pdf |access-date=September 2, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131231151912/http://wilderness.org/sites/default/files/legacy/TWTD-WY-Beartooth.pdf |archive-date=December 31, 2013 |url-status=dead |df=mdy-all}}</ref> Leases for sheep grazing have declined considerably since the 1940s while cattle grazing has remained relatively constant.<ref>{{cite web |title=Analysis of the Management Situation |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5356003.pdf |date=February 2012 |pages=79–81 |access-date=September 15, 2013 |archive-date=December 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131218122138/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5356003.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Fire ecology == | |||

| ] | |||

| Shoshone National Forest has an active Fire Management program which recognizes that ]s are a natural part of the ecosystem. The Yellowstone National Park fires of 1988 also impacted regions within the forest, though not as severely as it had in the adjacent park. Working cooperatively with the National Interagency Fire Center, (which is a multiagency effort of federal, state and local resources), the forest has developed a system of fire restrictions, fuels management, and a ] plan designed to help reduce the chances of a huge catastrophic fire. | |||

| == Natural resources == | |||

| Fire was long thought of as bad and this is still true when discussing structure fires. ] was the U.S. Forest Service mascot that for decades reminded the public with the adage that "only you can prevent wildfires" as a method to help ensure that visitors to forests would be careful with fire. While a need to continue to ensure that people do use fire safely, an active re-education program helps to promote the knowledge that not all fire is harmful when properly managed. As was true in all national forests, Shoshone National Forest long had a policy of suppressing forest fires immediately upon their discovery. So successful were the original efforts to prevent forest fires that over time huge sources of fuel in the form of dead and dying trees littered the forest floor. Prior to, but especially after the catastrophic fires in the Yellowstone region in 1988, the effort to identify areas of similar fire potential were identified. Today, the forest, in conjunction with the National Interagency Fire Center, works to allow some natural fires to burn unsuppressed and to actively engage in controlled burns to help reduce the risk of larger and harder to manage fire incidents. | |||

| {{See also|Ecology of the Rocky Mountains}} | |||

| === Flora === | |||

| Though much of the forest is remote and the surrounding region sparsely populated, some concern over the proximity of peoples homes and businesses, primarily along major roads through the forest, has dictated a need for a cooperative effort between the forest and local land owners to minimize the potential for human injury and fatalities. Better known as the ], it is the region where the forest and human development meet. | |||

| ] | |||

| Shoshone National Forest is an integral part of the ], which has 1,700 documented species of plants.{{sfn|Wuerthner|1992|p=65}} Since the elevation of the land in the forest ranges from {{cvt|4600|to|13804|ft}}, which is more than {{cvt|9000|ft}}, the forest has a wide variety of ecosystems.<ref name=about>{{cite web |title=About the forest |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/shoshone/about-forest |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |access-date=November 2, 2013 |archive-date=November 6, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131106054958/http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/shoshone/about-forest |url-status=live }}</ref>{{sfn|Enright|1992|p=137}} Lower elevations often have ] and ]-dominated ] types, while forested areas are dominated by various combinations of tree and shrub species. These include ], which along with ], and ] are found at elevations up to {{cvt|9000|ft}}.{{sfn|Enright|1992|p=137}} At higher elevations ], ], ] and ], are common, each occurring up to ].{{sfn|Enright|1992|p=137}} The region above timberline makes up 25 percent of the total acreage of the forest and of that 13 percent is listed as just either barren, rock or ice.<ref name=vg>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest Visitor Guide |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5330186.pdf |access-date=January 4, 2014 |archive-date=September 19, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150919135917/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5330186.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The types of plant species is highly dependent on the amount of water available, and trees are more commonly found on higher slopes due to the longer lasting snowfall which keeps the soil moister for a longer time into the summer months. Along lower elevation ] corridors, ] and ]s are typically dominant. Numerous plant species are ] to the region including some that are rare. Among them, the ], ], shoshonea, and the ] provide vivid white and yellow flowers during the spring and summer.<ref name=plants>{{cite web |title=Rare Plants of Shoshone National Forest (USFS R-2) |work=Wyoming Rare Plant Field Guide, US Forest Service Rare Plant List |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |url=http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/distr/others/wyplant/shoshone.htm |access-date=September 30, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051208153115/http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/resource/distr/others/wyplant/shoshone.htm |archive-date=December 8, 2005 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> | |||

| ] of flora that are not native to the region include ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name=houston>{{cite web |last=Houston |first=Kent E. |author2=Walter J. Hartung |author3=Carol J. Hartung |title=A Field Guide for Forest Indicator Plants, Sensitive Plants, and Noxious Weeds of the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr084.pdf |pages=155–171 |access-date=November 2, 2013 |date=October 2001 |archive-date=November 4, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131104141957/http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr084.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> These non-native plant species are considered noxious, impacting native plant communities and the species that thrive on them.<ref name=houston/> Native species such as the ] are having an enormous negative impact on some tree species.<ref name=beetle>{{cite web |title=Bark Beetle Epidemic |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/?cid=STELPRDB5358725 |access-date=November 2, 2013 |archive-date=November 6, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131106055042/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/?cid=STELPRDB5358725 |url-status=live }}</ref> A survey of the forest performed in 2010 indicated that over {{convert|1000000|acre}} of timberland had been impacted by insects such as the mountain pine beetle, ] and ], and that the insects had killed between 25 and 100 percent of the trees in the impacted areas.<ref name=impact>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest – vegetation management projects in 2011 |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=https://fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5260311.pdf |access-date=November 2, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141031163352/https://fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5260311.pdf |archive-date=October 31, 2014 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> The forest service is addressing the situation by performing controlled burns, selling dead trees as firewood, timber harvesting and spraying the highest value areas.<ref name=beetle/> | |||

| == Climate == | |||

| === Fauna === | |||

| While the state of Wyoming is generally considered a ] state with an average of less than 10 inches (25 cm) of precipitation annually, Shoshone National Forest is located in the some of the largest mountain ranges in the state, which ensures that glaciers and snowmelt provide water for streams through the dry ] months. The average temperature at the lower elevations in the forest are 72°F (22.2°C) during the summer and 20°F (-6.7°C) during the winter, and the higher peaks average 20°F (-6.7°C) below those figures. The hottest temperature ever recorded is 105°F (40.6°C) while a reading of -52°F (-47°C) was recorded in 1993. Most of the precipitation falls in the ] and early ] while summer is punctuated with widely scattered afternoon and evening thunderstorms. The ] is usually cool and dry. Due to the altitude and dryness of the atmosphere, vigorous radiative cooling occurs throughout the year and temperature variances of 50°F (10°C) daily are normal. Consequently, the nights range from very cool in the summer to ] in the winter and visitors should always remember to bring along at least a jacket, even during the summer. | |||

| ] | |||

| Since the migration of the ] ] into Shoshone National Forest after the successful ] program in the Yellowstone region commenced in the mid-1990s, all of the known 70 ] species that existed prior to white settlement still exist in the forest.{{sfn|Enright|1992|p=137}} Altogether, at least 335 species of wildlife call Shoshone National Forest their home, including the largest population of ] and one of the few locations ]s can still be found in the ]<ref name=vg/> | |||

| At least 700 grizzly bears are believed to exist in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, which includes Shoshone National Forest, with approximately 125 grizzlies in the forest.{{sfn|Enright|1992|p=137}}<ref name=grizzly>{{cite web |title=Grizzly Bear Conservation and Recovery |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/biology/resources/pubs/issuepapers/Issueupdate_GrizRecovery_Sept2013.pdf |date=September 2013 |access-date=November 15, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131215210412/http://www.fs.fed.us/biology/resources/pubs/issuepapers/Issueupdate_GrizRecovery_Sept2013.pdf |archive-date=December 15, 2013 |df=mdy-all}}</ref> The grizzly is listed as a ] by the ], and the forest is one of their last strongholds. For what are considered to be "nuisance bears", non-lethal traps are set to capture them so that they can be relocated to remote areas, away from civilization.<ref name=moody>{{cite web |last=Moody |first=David |author2=Dennie Hammer |author3=Mark Bruscino |author4=Dan Bjornlie |author5=Ron Grogan |author6=Brian Debolt |title=Wyoming Grizzly Bear Management Plan |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |url=http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/Departments/Wildlife/pdfs/WYGRIZBEAR_MANAGEMENTPLAN0000716.pdf |pages=25–31 |date=July 2005 |access-date=December 15, 2013 |archive-date=February 22, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150222182547/https://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/Departments/Wildlife/pdfs/WYGRIZBEAR_MANAGEMENTPLAN0000716.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In the case of the grizzly, each captured bear is tranquilized and then ]ged with an identifying number. Each number is registered, and if the bear continues to return to areas where they pose a risk of imminent threat to human safety, they are exterminated.<ref name=moody/> The grizzly recovery efforts implemented by federal agencies have often resulted in major disagreements with local landowners and surrounding municipalities.<ref name=grizzly/> This situation occurs less frequently with the smaller and less aggressive ]. An active management program, in conjunction with other National Forests and National Parks within the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, works cooperatively to maximize human safety and to ensure habitat protection for both species of endemic bears. Visitors are mandated to store their food in their vehicles or in steel containers found in campgrounds, and ] trash receptacles are located in the front-country zones throughout the forest. In the ], food must be stored some distance from campsites, and other related precautions are enforced to help prevent bad encounters.<ref name=vg/> | |||

| == Geography == | |||

| ] | |||

| Of the three major ]s found in the forest, they are ] distinct from each other. The Absaroka Mountains were named after the ] Indians' name for themselves, although they only inhabited the far northernmost part to the mountain range. The Absarokas are primarily ] in origin, composed of ]s. The majority of the Absaroka Mountains are contained within the forest with the highest peak in the mountain range being ] at 13,153 feet (4009m). Stretching north to south through the northern and eastern sections of the forest, they span over 100 miles (160 km) from the ] border to south of ]. Important ] through the Absarokas include ] which leads to the eastern entrance of Yellowstone National Park, and ] which provides access to Jackson Hole and ]. The peaks of the Absaroka are ] in origin, having been the result of volcanic activity estimated to have occurred 50 million years ago during the ] ]. The rocks themselves are relatively dark and consist of ], ] and ]s. Due to the erosional influences of glaciers and water and the relative softness of the rocks, the Absarokas are quite craggy in appearance. ] was mined from the slopes of ] until the early 1920s and the small ] of Kirwen can still be seen today. Few lakes exist in the Absarokas but the headwaters of both the ] and ]s are found there. | |||

| ]s and ] are large ]s that inhabit the forest. Since the 1990s wolf reintroduction program in Yellowstone National Park, wolves have migrated into the forest and established permanent packs.<ref name=wolf1>{{cite web |title=2012 Wyoming Gray Wolf Population Monitoring and Management Annual Report |url=http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/wolf/annualrpt12/2012_WY_Annual_Report_FINAL_2013-04-04.pdf |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |access-date=December 21, 2013 |editor1=K.J. Mills |editor2=R.F. Trebelcock |page=1 |year=2013 |archive-date=April 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140401124351/http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/wolf/annualrpt12/2012_WY_Annual_Report_FINAL_2013-04-04.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Approximately a dozen wolf packs totaling 70 individual wolves were documented in the forest in 2012.<ref name=wolf2>{{cite web |title=2012 Wyoming Gray Wolf Population Monitoring and Management Annual Report |url=http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/wolf/annualrpt12/2012_WY_Annual_Report_FINAL_2013-04-04.pdf |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |access-date=December 21, 2013 |editor1=K.J. Mills |editor2=R.F. Trebelcock |pages=8–9 |year=2013 |archive-date=April 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140401124351/http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/wolf/annualrpt12/2012_WY_Annual_Report_FINAL_2013-04-04.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The wolf was delisted as endangered once their population levels had reached management objectives and limited hunting of wolves was permitted in the forest starting in 2012.<ref>{{cite web |title=Wolves in Wyoming |url=http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/wildlife-1000380.aspx |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |access-date=December 21, 2013 |year=2013 |archive-date=December 24, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224110650/http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/wildlife-1000380.aspx |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Gray Wolf Hunting Seasons |url=https://wgfd.wyo.gov/media/30027/download?inline&ved=2ahUKEwj645Ppj-yKAxWm8MkDHX7QFtMQFnoECBoQAQ |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Commission |access-date=January 10, 2024 |date=2023}}</ref> Cougars are generally nocturnal and rarely seen but hunting of this species is also allowed in highly regulated harvests.<ref>{{cite web |title=Mountain Lion Hunting Seasons |url=http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/imgs/QRDocs/REGULATIONS_CH42_BROCHURE.pdf |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Commission |access-date=December 21, 2013 |year=2012 |archive-date=December 24, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224101334/http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/imgs/QRDocs/REGULATIONS_CH42_BROCHURE.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Wolverines are rare and elusive so documentation is often only from their tracks.<ref>{{cite web |last=Murphy |first=Kerry |title=Wolverine Conservation in Yellowstone National Park |publisher=National Park Service |url=http://files.cfc.umt.edu/cesu/NPS/UMT/2004/04Pletscher_wolverines_final%20rpt.pdf |access-date=December 21, 2013 |date=March 2011 |archive-date=April 21, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210421223832/http://files.cfc.umt.edu/cesu/NPS/UMT/2004/04Pletscher_wolverines_final%20rpt.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] was native to the forest, but no known populations may still exist due to the rarity of its primary food source, the ]. Shoshone National Forest is considered critical habitat for lynx recovery since the species is listed as threatened under the ] and the forest is in their historical range.<ref>{{cite web |title=Proposed Revision of the Critical Habitat Designation for the Canada Lynx and Revised Definition of the Contiguous United States Distinct Population Segment of Canada Lynx |publisher=U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service |url=http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/lynx/09112013LynxCHQandA.pdf |year=2013 |access-date=December 21, 2013 |archive-date=December 24, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224115809/http://www.fws.gov/mountain-prairie/species/mammals/lynx/09112013LynxCHQandA.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Other generally carnivorous mammals include ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref name=species2>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest Species of Interest Report |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5199969.pdf |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |access-date=December 22, 2013 |pages=65–68 |date=April 2009 |archive-date=December 27, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131227085830/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5199969.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Omnivorous mammals such as the ] and ] and herbivore mammal species such as the ] and ], are common to the forest.<ref name=species2/><ref name=orabona>{{cite web |last=Orabona |first=Andrea |title=Atlas of Birds, Mammals, Amphibians and Reptiles in Wyoming |url=http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/Departments/Wildlife/pdfs/WILDLIFE_ANIMALATLAS0002711.pdf |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |access-date=December 21, 2013 |author2=Courtney Rudd |author3=Martin Grenier |author4=Zack Walker |author5=Susan Patla |author6=Bob Oakleaf |date=June 2012 |archive-date=November 16, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131116083911/http://wgfd.wyo.gov/Web2011/Departments/Wildlife/pdfs/WILDLIFE_ANIMALATLAS0002711.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] is considered a species of special interest to Shoshone National Forest since its dam building activities improve habitat for numerous other species such as the ], breeding waterfowl, various amphibians and other species dependent on a riparian environment.<ref name=species1>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest Species of Interest Report |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5199969.pdf |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |access-date=December 22, 2013 |pages=6–11 |date=April 2009 |archive-date=December 27, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131227085830/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5199969.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The Beartooth Mountains in the northernmost section of the forest are ] and ] in origin. Some rocks in that area have been dated up to 3.96 billion years old, which makes these exposed ] rocks some of the oldest on ]. Although oftentimes considered a part of the Absarokas, they are distinct in appearance and geologic history. Uplifted approximately 70 million years ago during the ], the Beartooths consist of vast windswept plateaus and rugged peaks with sometimes sheer cliff faces. The granite, ] and ] rocks are rich in minerals such as ] and ]. ] and ] are found in the ], ] and ] minerals throughout the range. ] and ]s are also commonly found. Geologists believe that the Beartooth's were at one time as much as 20,000 feet (6,096 m) in altitude at least, but subsequent erosion for tens of millions of years has reduced them to an average of 12,000 feet (3,657 m) for the higher peaks. There are an estimated 300 lakes in the Beartooth region of Shoshone National Forest, some of them left behind by the last major ] glaciation known as the ], which ended roughly 10,000 years ago. The ] (]), crosses 10,974 foot (3,345 m) Beartooth Pass, and from there descends to the northeast entrance to Yellowstone National Park. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The Wind River Range is in the southern portion of the forest and are composed primarily of granitic rock, gneiss and schist. ] at 13,804 feet (4,207 m), is the highest peak in Wyoming and another seven peaks also exceed 13,500 feet (4,115 m). In total, over 230 mountains rise above 12,000 feet (3,600 m). Most of the ] found in the forest are located in the Wind River Range and counting those found in the Absarokas and Beartooths, there are a total of 156 of them; the most in any single forest in the U.S. outside of ]. ]s are a series of massive glacial features that are found in the northern Wind River Range near Gannett and ]s. The seven largest glaciers in the U.S. outside of Alaska are also located in the immediate area. This range is also popular with mountain climbers from all over the world due to the sheer cliff faces and excellent stabilty of the rocks for rope anchoring points. The ] in the ] is one of the more popular climbing and hiking destinations, and an estimated 200 different climbing routes are located within the peaks that surround the ]. Hundreds of lakes are located in this region as are the headwaters of the ]. | |||

| Native herbivores such as the moose are found in small numbers near waterways, especially at lower elevations. Moose populations in northwestern Wyoming and other areas of North America have been on the decline since the end of the 20th century, possibly due to a parasite.<ref>{{cite news |last=French |first=Brett |title=Montana, Wyoming trying to understand why moose populations are plummeting |work=] |url=http://billingsgazette.com/lifestyles/recreation/montana-wyoming-trying-to-understand-why-moose-populations-are-plummeting/article_cf1fcb02-9699-56d8-9b34-9b297fd4dc5f.html |date=September 17, 2012 |access-date=December 21, 2013 |archive-date=September 21, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120921022943/http://billingsgazette.com/lifestyles/recreation/montana-wyoming-trying-to-understand-why-moose-populations-are-plummeting/article_cf1fcb02-9699-56d8-9b34-9b297fd4dc5f.html |url-status=live }}</ref> There were an estimated 739 moose in the forest in 2006 which is almost 300 fewer than there were 20 years earlier.<ref name=species1/><ref name=population>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest Comprehensive Evaluation Report |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5201453.pdf |date=December 2007 |access-date=December 21, 2013 |archive-date=December 25, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131225155515/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5201453.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Other ungulate species are much more common and there are over 20,000 ] (also known as wapiti) and 40,000 ].<ref name=population/> Bighorn sheep and ]s inhabit the rocky terrain and highest elevations. During the winter, one of the largest bighorn sheep herds in the ] congregate in the region around ]; however, their numbers since 1990 have been diminished due to disease transmitted from contact with domesticated sheep and goats.<ref>{{cite web |last=Mlodik |first=Cory |title=Risk Analysis of Disease Transmission between Domestic Sheep and Goats and Rocky Mountain Bighorn Sheep |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5383002.pdf |date=April 2012 |access-date=December 21, 2013 |archive-date=December 26, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131226080005/http://www.fs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/stelprdb5383002.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> An estimated 5,000 bighorn sheep are found throughout the forest and a small but stable population of 200 mountain goats reside in the northernmost portions of the forest.<ref name=population/> ] and ] antelope are two other ungulates that live on the forest and have sustainable populations.<ref name=species2/> | |||

| At least 700 named lakes are located in the forest, as well as 2,500 miles (4,023 km) of streams and rivers. The ] is designated as a ] for 22 miles (35 km) through the forest, with cliffs towering up to 2,000 feet (610 m) as the river winds through a gorge also named for the river. All of the forest is located immediately east of the Continental Divide and all the water that flows out of the forest eventually empties into the ]. | |||

| An estimated 300 species of birds are found in the forest at least part of the year. ], ], ] and the ] are birds of prey that are relatively common.<ref name=species2/> Waterfowl such as ], ], ] and ] have stable populations and rare sightings of ]s are reported.<ref name=species2/> ], ] and ] are widely distributed across the open sage lands. ] and ] are generally rare but management plans were implemented to protect various habitats these two species frequent to try and increase their population numbers.<ref name=species1/> | |||

| == Wilderness == | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| Fish found in Shoshone National Forest include at least six species and subspecies of trout including ], ] and ]. The ] is widespread throughout the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, but in the forest is mostly limited to the ].<ref name=fishguide>{{cite web |title=Wyoming Fishing Guide |publisher=Wyoming Game and Fish Department |url=http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/Departments/Fishing/pdfs/WGFD_FISHINGGUIDE0000393.pdf |year=2011 |access-date=December 29, 2013 |archive-date=October 19, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131019035222/http://wgfd.wyo.gov/web2011/Departments/Fishing/pdfs/WGFD_FISHINGGUIDE0000393.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=gresswell>{{cite web |last=Gresswell |first=Robert |title=Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii bouvieri): A Technical Conservation Assessment |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/yellowstonecutthroattrout.pdf |date=June 30, 2009 |access-date=December 29, 2013 |archive-date=October 8, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131008161733/http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/yellowstonecutthroattrout.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] is also found in the Shoshone River, while the ] is found in two streams in the southern regions of the forest.<ref name=fishguide/> | |||

| Four ] areas are found within the forest that total 1.5 million acres (6,000 km²) and include the ], ], ] and ]es. Additionally, a small portion of the ] extends into the extreme north western part of the forest, along the ] border. | |||

| There are more than a dozen species of ]s in the forest including the venomous ] which can be found at lower elevations.<ref name=orabona/> The ] and the ] are turtle species known to exist and about eight species of lizards such as the ] have been documented.<ref name=orabona/> Amphibians such as the ] and the ] are considered species of concern because of their high susceptibility to disease, habitat loss and human introduced toxins.<ref name=species1/> Boreal toads are found at elevations of between {{cvt|7380|and|11800|ft}} and the Columbia spotted frog can live at elevations as high as {{cvt|9480|ft}} in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.<ref name=species1/> | |||

| The ] was the beginning of an effort to enhance protection status to remote and or undeveloped sections of acreage already contained within federally administered land areas. Passage of the act ensured that no human improvements would take place aside from those already existing. This includes road and building ], ] and ] exploration or ], logging and prohibits the use of motorized equipment, including even ]s. The only manner in which people can enter wilderness designated areas is either on foot or ]. ] and ] are permitted provided those engaging in such activities have the proper licenses and permits. | |||

| Exotic species of fauna such as the ] and ]s and the ] are invasive species that can greatly impact fish species. Though the mussel species are not known to be in Wyoming, several surrounding regions have reported them. The New Zealand mud snail has been found in the Shoshone River east of the forest. Forest managers have established a preventative program to try to keep these species from entering forest waterways.<ref>{{cite web |title=Aquatic Invasive Species |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/?cid=STELPRDB5358127 |access-date=December 29, 2013 |archive-date=October 31, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141031173830/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/?cid=STELPRDB5358127 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Recreation == | |||

| === Wilderness === | |||

| Over half a million visitors will spend at least one night in the forest in an average year. There are 30 vehicle access ]s scattered around the forest with up to 27 individual sites each. Approximately half of these campgrounds provide running water and restroom facilities and also provide for handicapped accessibility. Referred to as "front country" campgrounds, they also permit ] access in most cases. All of the campgrounds are on a first come, first served basis except for the Rex Hale campground which is on the National Recreation Reservation Service; a phone and web based system that allows tourists to reserve a site months ahead of time. Due to the presence of Grizzly Bears, some of the campgrounds require what is referred to as "hard-sided" camping only and tent camping is not permitted. For some visitors, the greater solitude of the "backcountry" requires accessing ] and then ]ing into more remote destinations. There are dozens of trails which total over 1,500 miles (2,400 km) spread out throughout the forest. The ] weaves its way through the forest though it follows alternatively named trails for some of the distance. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The forest contains four areas of pristine ] that have remained largely untouched by human activities such as mining, logging, and road and building construction. The four regions include the ], ], ] and ]es.<ref name=about/> Additionally, a small portion of the ] extends into the extreme northwestern part of the forest, along the Montana border. In Shoshone National Forest, {{cvt|1400000|acre}}, constituting 56 percent of the forest is designated wilderness.<ref name=vg/><ref name=wilderness>{{cite web |title=Wilderness |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5183021 |access-date=September 7, 2013 |archive-date=November 6, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131106055030/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5183021 |url-status=live }}</ref> The wilderness designation provides a much higher level of land protection and prohibits any alterations by man to the resource.<ref name=nwps>{{cite web |last=Landres |first=Peter |author2=Shannon Meyer |title=National Wilderness Preservation System Database: Key Attributes and Trends, 1964 Through 1999 |publisher=U.S. Department of Agriculture |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr018.pdf |page=1 |date=July 2000 |access-date=September 7, 2013 |archive-date=November 4, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131104134030/http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr018.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The ] enhanced the protection status of remote and/or undeveloped land already contained within federally administered protected areas. Passage of the act ensured that no human improvements would take place aside from those already existing. The protected status in wilderness designated zones prohibits road and building construction, oil and mineral exploration or ], and logging, and also prohibits the use of motorized equipment, including even bicycles. The only manner in which people can enter wilderness areas is either on foot or ]. ] and ] are permitted in the wilderness, just as they are throughout the forest, provided those engaging in such activities have the proper licenses and permits.<ref name=wilderness2>{{cite web |title=The National Wilderness Preservation System |publisher=Wilderness.net |work=The Wilderness Act of 1964 |url=http://www.wilderness.net/index.cfm?fuse=NWPS&sec=legisAct |access-date=September 7, 2013 |archive-date=February 28, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120228165154/http://www.wilderness.net/index.cfm?fuse=NWPS&sec=legisAct |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ] and ] are popular recreational activities and are permitted throughout the forest, provided that proper permits are obtained and the applicable rules and regulations are followed. Hunting regulations are altered each year to ensure certain species are protected from over hunting and to maximize personal safety. There are over a dozen species of game fish that are a naturally occurring including six subspecies of ]. Many of the streams and rivers within the forest are considered to be Blue Ribbon Trout Streams. 1,700 miles of streams and 500 lakes that one can legally fish from provide plenty of elbow room during even the most crowded of fishing seasons. Hunting and fishing licenses are sponsored by the state of Wyoming and are available through the state department of fish and game. | |||

| === Fire ecology === | |||

| Since some sections of the forest and especially wilderness areas are oftentimes remote and not everyone wishes to hike into them on foot, there are numerous trails that provide access by way of horseback. Trailheads usually provide enough room for horse and pack animal trailers plus personal vehicles. A number of private operations provide pack trips for a few days to a few weeks into the forest. Most but not all of the private enterprises that provide guided pack trips are monitored and or licensed by Shoshone National Forest and all food and camping gear are provided for the most part. | |||

| {{see also|Fire ecology|Wildfire#Ecology}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Fire Management officials in Shoshone National Forest recognize that ]s are a natural part of the ecosystem; however, this was not always the case. 20th century fire fighting efforts, especially in the first half of that century, emphasized quickly extinguishing all fires, as fire was seen as completely detrimental to a forest.{{sfn|Aplet|2006}} In 1935, fire management officials established the ''10 am rule'' for all fires on federal lands, which recommended aggressive attack on fires and to have them controlled by 10 am, the day after they are first detected.<ref name=10am>{{cite web |title=Evolution of Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy |work=Review and Update of the 1995 Federal Wildland Fire Management Policy January 2001 |publisher=National Park Service, U.S. Forest Service |date=January 2001 |url=http://www.nwcg.gov/branches/ppm/fpc/archives/fire_policy/docs/chp1.pdf |access-date=December 30, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121018102707/http://www.nwcg.gov/branches/ppm/fpc/archives/fire_policy/docs/chp1.pdf |archive-date=October 18, 2012}}</ref>{{sfn|Omi|2005|p=67}} This was intended to prevent fires from remaining active into the afternoon when the rising temperatures and more turbulent air caused fires to expand and become more erratic.{{sfn|Omi|2005|p=131}} However, this policy led to an increase in fuels because fires were often extinguished before they had a chance to burn out dead and dying old growth. It was in a stand of old growth fir trees in Shoshone National Forest that the ] killed 15 fighters during a firestorm {{cvt|35|mi}} west of Cody, Wyoming. The fire was one of the deadliest in terms of forest firefighter deaths in U.S. history.<ref name=deaths>{{cite web |title=Deadliest Incidents Resulting in the Deaths of 8 or More Firefighters |publisher=National Fire Protection Association |url=http://www.nfpa.org/research/reports-and-statistics/the-fire-service/fatalities-and-injuries/deadliest-incidents-resulting-in-the-deaths-of-8-or-more-firefighters |access-date=December 30, 2013 |date=February 2012 |archive-date=December 15, 2013 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20131215183047/http://www.nfpa.org/research/reports-and-statistics/the-fire-service/fatalities-and-injuries/deadliest-incidents-resulting-in-the-deaths-of-8-or-more-firefighters |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Between the years 1970 and 2012, Shoshone National Forest averaged 25 fires annually, of which half were due to natural ignition from lightning, which accounted for 90 percent of the total acreage burned. The remaining acreage that burned was due to campfires that got out of control or from other causes.<ref name=fmp1>{{cite web |title=Shoshone National Forest Fire Management Plan – 2012 |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://gacc.nifc.gov/rmcc/dispatch_centers/r2cdc/predictive/fuels_fire_danger/SHF%20FMP/shf%20fmp%202012%20final%204-16-12.pdf |pages=46–49 |year=2012 |access-date=January 4, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140104210817/http://gacc.nifc.gov/rmcc/dispatch_centers/r2cdc/predictive/fuels_fire_danger/SHF%20FMP/shf%20fmp%202012%20final%204-16-12.pdf |archive-date=January 4, 2014 |url-status=dead}}</ref> In Shoshone National Forest, the highest fire incidence is generally in the months of August and September.<ref name=fmp1/> An average of {{cvt|2334|acre}} burns annually, with the worst year in the past century being 1988, when {{cvt|194430|acre}} burned from fires that had spread from the conflagration that engulfed Yellowstone National Park and the surrounding region.<ref name=fmp1/> After the ], an effort to identify areas of similar fire potential was implemented.{{sfn|Aplet|2006}} Fire managers at Shoshone National Forest work with a number of outside agencies to incorporate fire restrictions, fuels management, and a ] plans to reduce the chances of a catastrophic fire.<ref name=fire>{{cite web |title=Fire and fuels management |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/resourcemanagement/?cid=stelprdb5192920 |access-date=December 30, 2013 |archive-date=January 1, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140101022055/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/landmanagement/resourcemanagement/?cid=stelprdb5192920 |url-status=live }}</ref> The dead and dying trees which have been killed by various species of bark beetle may have a great impact on future forest fires.<ref name=impact/> Fire managers have stated the worst time for increased fire activity is 1–2 years after the trees are killed and then again after the trees have fallen many years later.<ref>{{cite web |title=About the epidemic |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/barkbeetle/aboutepidemic |access-date=December 30, 2013 |archive-date=November 9, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131109134443/http://www.fs.usda.gov/main/barkbeetle/aboutepidemic |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Along forest access roads, ]s are allowed. There is an active management plan which is redesignating the locations for this type of activity to ensure visitors are well informed as to where this activity is allowed and where it is illegal as it is considered to be relatively destructive to the terrain and creates a problem with noise abatement. | |||

| == Geography and geology == | |||

| The southern sections of the forest in the Wind River Range is the primary destination for ]s. 29 of the highest 30 peaks in Wyoming are located here and the mountains are primarily of granitic rock with countless cliffs and sheer rock walls. The ] is particularly popular as it has numerous peaks within a relatively short distance of each other. | |||

| ] is the highest mountain in Wyoming and the forest.]] | |||

| Shoshone National Forest borders ] and ] to the west. The ] demarks the boundary between Shoshone and Bridger-Teton National Forests. Along the ] border, Shoshone National Forest borders ] to the north.<ref name=fmp1/> Private property, property belonging to the state of Wyoming and lands administered by the ] form the eastern boundaries. Lastly, the Wind River Indian Reservation also borders on the east, and bisects a smaller southern section which includes the Popo Agie Wilderness and the Washakie Ranger District.<ref>{{cite web |title=Washakie Ranger District |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/about-forest/?cid=stelprdb5191040 |access-date=January 17, 2014 |archive-date=November 9, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131109210439/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/about-forest/?cid=stelprdb5191040 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The altitude in the forest ranges from {{convert|4600|ft}} near Cody, Wyoming, to {{cvt|13804|ft}} at the top of ], an elevation gain of over {{cvt|9200|ft}}.<ref name=fmp1/> Of the three major ]s found in the forest, they are ] distinct from each other. All of the mountains are a part of the Rocky Mountains. In the northern and central portions of the forest lie the ] which were named after the ] Indian tribe.<ref name=absaroka>{{cite web |title=Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5190252 |access-date=January 18, 2014 |archive-date=November 9, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131109034226/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5190252 |url-status=live }}</ref> The majority of the Absaroka Mountains are contained within the forest, with the highest peak being ] at {{cvt|13158|ft}}.{{sfn|Antweiler|Bieniewski|1984}} The peaks of the Absaroka are ] in origin, having been the result of volcanic activity estimated to have occurred 50 million years ago during the ] ].{{sfn|Antweiler|Bieniewski|1984}} The rocks are composed of mostly ] and ]s deposited for millions of years during volcanic events and are atop more ancient ]s that are considered to have economically viable mineral wealth.{{sfn|Antweiler|Bieniewski|1984}} Gold was mined from the slopes of Francs Peak between the years 1890 and 1915, and the small ] of Kirwin remains as a legacy of that period.<ref name=kirwin/> Major tributaries of the ], such as the Shoshone and ]s, originate in the Absaroka Mountains. Important ] through the Absarokas include ], which leads to the eastern entrance of Yellowstone National Park; and ], which provides access to Jackson Hole and ].{{sfn|Larson|1981|p=429}}{{sfn|Adkison|1996|p=1}} | |||

| Winter activities include ] and ]. The ]. With up to 40 feet of snow annually in the higher elevations, the snowmobile season extends usually from the beginning of December to the middle of April. Lander, Wyoming, Cody, Wyoming and the area near Togwotee Pass are the hubs of snowmobile activity in the forest. Numerous outfitters rent snowmobiles on a daily basis and can provide guided trips for those less experienced. A number of motels also remain open during the winter to provide food and lodging. Yellowstone National Park has commenced restricting snowmobile use within the park and consequently, the forest has seen an upswing in the number of snowmobilers. Many of the trails are "groomed" and marked to maximize safety, but many areas are off trail, but should only be ventured into by the more experienced adventurers that are familiar with the equipment and the region. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the far north of Shoshone National Forest a small portion of the Beartooth Mountains are located north of the ]. The Beartooths are composed of ] ] rocks that are amongst the oldest found on Earth.{{sfn|Van Kranendonk|Smithies|Bennett|2007|pp=780–781}} Although often considered a part of the Absaroka Mountains, the Beartooths are distinct in appearance and geologic history.<ref name=absaroka/> Uplifted approximately 70 million years ago during the ], the Beartooths consist of vast windswept plateaus and rugged peaks with sheer cliff faces. The ] (]) crosses {{convert|10974|ft|m|adj=on|sigfig=3}} Beartooth Pass, and from there descends to the northeast entrance to Yellowstone National Park. | |||

| == Tourism == | |||

| ]]] | |||

| An estimated 2 million visitors pass through Shoshone National Forest each year, many of them on their way to Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks. Outside of the main roads through the forest, there are oftentimes few tourists aside from those who are looking for isolation. Many trails and the more remote regions of the forest have few if any visitors recorded annually. The towns of Cody and ] have numerous lodging and dining opportunities as well as small municipal ]s. If arriving by air to the region, it may be best to fly to ] or ] and travel to the forest by rented vehicle. The closest major international airport is located in ]. Along several of the scenic roads through the forest, there are isolated recreational ranches and motels to be found. Due to particularily heavy tourism between the months of ] and ] it is strongly advised that visitors make advance reservations for lodging. Shoshone National Forest also has a few cabins that can rented and which can be reserved. The Rex Hale campground is on the National Recreation Reservation system and can be reserved, while the remaining campgrounds are all on a first come first served basis. | |||

| ] | |||

| Two visitor centers provide orientation, books, maps, and interpretive displays and are staffed by either forest service interpretors or volunteers. The Wapiti Wayside is located on the ], west of ] adjacent to the historic Wapiti Ranger Station. Another visitor center is located to the south in ]. | |||

| The Wind River Range is in the southern portion of the forest and is composed primarily of Precambrian granitic rock.<ref name=winds>{{cite web |title=Wind River Range |publisher=Wyoming State Geological Survey |url=http://www.wsgs.uwyo.edu/research/stratigraphy/WindRiverRange/Default.aspx |year=2013 |access-date=January 21, 2014 |archive-date=February 3, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140203184936/http://www.wsgs.uwyo.edu/research/stratigraphy/WindRiverRange/Default.aspx |url-status=live }}</ref> Gannett Peak, the tallest mountain in Wyoming, is in the northern part of the range. Altogether eight peaks exceed {{cvt|13500|ft}} and 119 rise at least {{cvt|12000|ft}} above sea level.{{sfn|Kelsey|2013|p=432}} ], the second highest peak in the range, was originally believed to be the tallest mountain in the Rocky Mountains due to its prominence when viewed from the ] by early pioneers.{{sfn|Cooper|2008|pp=76–82}} The Wind River Range is popular with mountain climbers because of its solid rock and variety of routes.<ref name=windriver>{{cite web |title=Wind River Ranger District |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/about-forest/districts/?cid=stelprdb5191039 |access-date=January 21, 2014 |archive-date=February 4, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140204041143/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/about-forest/districts/?cid=stelprdb5191039 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] in the ] is one of the more popular climbing and hiking destinations, and an estimated 200 different climbing routes are located within the peaks that surround the ].{{sfn|Cooper|2008|pp=76–82}} | |||

| There are over 500 lakes in the forest, and {{cvt|1000|mi}} of streams and rivers.{{sfn|Dow|Dow|2001|p=507}} The Clarks Fork of the Yellowstone River is federally designated as a ] for {{cvt|22|mi}} through the forest, with cliffs towering up to {{cvt|2000|ft}} as the river winds through a gorge. The forest is on the eastern slopes of the Continental Divide, and the rivers flow into the ]. | |||

| As a gateway to two entrances leading into Yellowstone National Park from the east, the forest has a number of scenic roadways. A federally designated ], the ] (]), weaves through the forest and serves as the northeastern entranceway to Yellowstone National Park. Immediately south of the Beartooth Highway, the ] (Wyoming route 296) follows the old trail in which ] and the ] tribe attempted to flee the ] in 1877. South of there, Buffalo Bill Cody Scenic Byway (US 14/16/20) heads west from Cody, Wyoming and crosses ] as it enters Yellowstone. Lastly, the ] (US 26/287) heads west from ], over Togwotee Pass and enters Jackson Hole and Grand Teton National Park. The Chief Joseph, Buffalo Bill Cody and Wyoming Centennial byways have all been designated by the U.S. Government as ]s. | |||

| == |

=== Glaciology === | ||

| According to the U.S. Forest Service, Shoshone National Forest has the greatest number of glaciers of any National Forest in the Rocky Mountains. The forest recreation guide lists 16 named and 140 unnamed glaciers within the forest, all in the Wind River Range. Forty-four of these glaciers are in the Fitzpatrick Wilderness, centered around the highest mountain peaks.<ref name=vg/><ref>{{cite web |title=Fitzpatrick Wilderness |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5190243 |access-date=January 11, 2014 |archive-date=November 9, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131109112424/http://www.fs.usda.gov/detail/shoshone/specialplaces/?cid=stelprdb5190243 |url-status=live }}</ref> However, the state water board for Wyoming lists only 63 glaciers for the entire Wind River Range, which includes glaciers in adjacent Bridger-Teton National Forest.<ref name=state>{{cite web |last=Hutson |first=Harold J |title=Wyoming State Water Plan |url=http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/bighorn/techmemos/glaciers.html |access-date=January 11, 2014 |archive-date=May 16, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110516103812/http://waterplan.state.wy.us/plan/bighorn/techmemos/glaciers.html |url-status=live }}</ref> Researchers claim that for most of the period that glaciers have been known to exist in the forest, that they have been in a state of general retreat, with glacial mass losses of as much as 25 percent between the years 1985 and 2009.<ref name=rice>{{cite web |last=Rice |first=Janine |author2=Andrew Tredennick |author3=Linda A. Joyce |title=Climate Change on the Shoshone National Forest, Wyoming: A Synthesis of Past Climate, Climate Projections, and Ecosystem Implications |date=January 2012 |publisher=U.S. Forest Service |url=http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr264.pdf |pages=24–25 |access-date=January 11, 2014 |archive-date=November 5, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131105040837/http://www.fs.fed.us/rm/pubs/rmrs_gtr264.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{Commons|Shoshone National Forest|Shoshone National Forest}} | |||

| * | |||

| Reversing the growth of mid-latitude glaciers that occurred during the ] (1350–1850), there has been a ] since, with some regions losing as much as 50 percent of their peak ice cover. This can be correlated by examining ] evidence of glaciers taken over time even with an absence of other means of documentation.{{sfn|Hall|Fagre|2003|p=131}} The behavior of the glaciers of Shoshone National Forest is consistent with this pattern. In one study of ] and ]s, during the period from 1958 to 1983, the thickness of these glaciers was reduced {{cvt|77|and|61|ft}}, respectively.<ref name=retreat>{{cite web |last=Pochop |first=Larry |author2=Richard Marston |author3=Greg Kerr |author4=David Veryzer |author5=Marjorie Varuska |author6=Robert Jacobel |title=Glacial Icemelt in the Wind River Range, Wyoming |work=Water Resources Data System Library |url=http://library.wrds.uwyo.edu/wrp/90-16/90-16.html |date=July 1990 |access-date=January 12, 2014 |archive-date=August 24, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130824191415/http://library.wrds.uwyo.edu/wrp/90-16/90-16.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * | |||

| ] | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||