| Revision as of 01:28, 4 January 2014 editAndajara120000 (talk | contribs)3,715 edits GrammarTag: Mobile edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:39, 11 January 2025 edit undoAlbertatiran (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,103 edits Undid revision 1268746060 by 2601:483:5501:72B0:76C2:95D:77FC:54E2 (talk) Rv, just to be on the safe side, it's probably a good idea to first quote the source on the talk page, considering that you're an IP editor.Tags: Undo Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{About||criticism of political Islam|Criticism of Islamism|fear of or prejudice against Islam, rather than criticism|Islamophobia}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2022}} | |||

| {{Islam |related |width=22.0em}} | |||

| {{Criticism of Islam}} | {{Criticism of Islam}} | ||

| '''Criticism of ]''' can take many forms, including academic critiques, political criticism, religious criticism, and personal opinions. Subjects of criticism include Islamic beliefs, practices, and doctrines. | |||

| Criticism of Islam has been present since its formative stages, and early expressions of disapproval were made by ], ], and some ] like ].<ref name="John of Damascus2">De Haeresibus by ]. See ]. '']'', vol. 94, 1864, cols 763–73. An English translation by the Reverend John W Voorhis appeared in ''The Moslem World'' for October 1954, pp. 392–98.</ref> Subsequently, the ] itself faced criticism after the ].<ref name="WarraqPoetry">{{cite book|last=Warraq|first=Ibn |title=Leaving Islam: Apostates Speak Out |url=https://archive.org/details/leavingislamapos00warr|url-access=limited|publisher=Prometheus Books |year=2003 |isbn=1-59102-068-9 |page=}}</ref><ref name="Ibn Kammuna">Ibn Kammuna, ''Examination of the Three Faiths'', trans. ] (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1971), pp. 148–49</ref><ref name="Oussani">, by Gabriel Oussani, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 16 April 2006.</ref><ref name="fried1">{{cite book|first1=Yohanan|last1=Friedmann|year=2003|title=Tolerance and Coercion in Islam: Interfaith Relations in the Muslim Tradition|url=https://archive.org/details/tolerancecoercio00frie|url-access=limited|publisher=Cambridge University Press|page=, 35|isbn=978-0-521-02699-4}}</ref> | |||

| Criticism of Islam has been aimed at the life of ], the prophet of Islam, in both his public and personal lives.<ref name="Oussani" /><ref name="WarraqQuest">Ibn Warraq, The Quest for Historical Muhammad (Amherst, Mass.:Prometheus, 2000), 103.</ref> Issues relating to the authenticity and morality of the ], both the ] and the ]s, are also discussed by critics.<ref name="BibleInQuran">, by Kaufmann Kohler Duncan B. McDonald, ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 22 April 2006.</ref> Criticisms of Islam have also been directed at historical practices, like the recognition of ]<ref name="eois">Brunschvig. 'Abd; '']''</ref><ref name=OEIW>{{cite encyclopedia|author=Dror Ze'evi|title=Slavery|encyclopedia=The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World|editor=John L. Esposito|publisher=Oxford University Press|location=Oxford|year=2009|url=http://bridgingcultures.neh.gov/muslimjourneys/items/show/214|access-date=23 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170223125519/http://bridgingcultures.neh.gov/muslimjourneys/items/show/214|archive-date=23 February 2017|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>, in ].</ref><ref>, in ]</ref> as well as ] impacting indigenous cultures.<ref name="Islamic-Imperialism">{{cite book|url=https://yalebooks.yale.edu/book/9780300198171/islamic-imperialism|title=Islamic Imperialism: A History|last=Karsh|first=Ephraim|year=2007|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=9780300198171}}</ref> More recently, ] regarding ], ], ], and God's ] have received criticism for their apparent ] and scientific inconsistencies.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Fitzgerald | |||

| | first1 = Timothy | |||

| | year = 2000 | |||

| | title = The Ideology of Religious Studies | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=R7A1f6Evy84C | |||

| | location = New York | |||

| | publisher = Oxford University Press | |||

| | publication-date = 2003 | |||

| | page = 235 | |||

| | isbn = 9780195347159 | |||

| | access-date = 30 Apr 2019 | |||

| | quote = this book consists mainly of a critique of the concept of religion . | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref><ref name="Ruthven">{{cite web|title=Voltaire's Fanaticism, or Mahomet the Prophet:A New Translation; Preface: Voltaire and Islam|first=Malise|last=Ruthven|url=http://litwinbooks.com/mahomet-preface.php|accessdate=12 August 2015}}</ref> | |||

| Other criticisms center on the treatment of individuals within modern ], including issues which are related to ], particularly in relation to the application of ].<ref name="fried1"/> As of 2014, 26% of the world's countries had ], and 13% of them also had ]. By 2017, 13 Muslim countries imposed the death penalty for ] or ].<ref>, ], 29 July 2016.</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.indy100.com/article/the-countries-where-apostasy-is-punishable-by-death--Z110j2Uwxb|title=The countries where apostasy is punishable by death|first1=Louis|last1=Doré|date=May 2017|access-date=15 March 2018|newspaper=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=22&year=2005&country=6825|title=Saudi Arabia|access-date=7 October 2006|archive-date=9 November 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111109034847/http://www.freedomhouse.org/template.cfm?page=22&year=2005&country=6825|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="IslamInEurope">{{cite magazine| magazine=] | date=5 October 2006 | title=Islam in Europe | author=Timothy Garton Ash | url=http://www.nybooks.com/articles/19371}}</ref> Amid the contemporary embrace of ], there has been criticism regarding how Islam may affect the willingness or ability of Muslim immigrants to ] in host nations.<ref name="Modood">{{cite book| title=Multiculturalism, Muslims and Citizenship: A European Approach | url=https://archive.org/details/multiculturalism00modo | url-access=limited | author=Tariq Modood | publisher=Routledge | edition=1st | date=6 April 2006 | isbn=978-0-415-35515-5 | page=}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Russia and Islam: State, Society and Radicalism|page=94|publisher=Taylor & Francis|year=2010}} by Roland Dannreuther, Luke March</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| == Historical background == | |||

| ] a Syrian ] and ], 19th-century Arabic ]]] | |||

| The earliest surviving written criticisms of Islam are to be found in the writings of ]s who came under the early dominion of the Islamic ]. One such Christian was ] (c. 676–749 AD), who was familiar with Islam and ]. The second chapter of his book, ''The Fount of Wisdom'', titled "Concerning Heresies", presents a series of discussions between Christians and Muslims. John claimed an ] ] (whom he did not know was ]) influenced Muhammad and viewed the Islamic doctrines as nothing more than a hodgepodge culled from the Bible.<ref> St. John of Damascus</ref> Writing on Islam's claim of Abrahamic ancestry, John explained that the ] were called "]s" (Greek Σαρακενοί, Sarakenoi) because they were "empty" (κενός, kenos, in Greek) "of ]". They were called "]" because they were "the descendants of the slave-girl ]".<ref>John McManners, The Oxford History of Christianity, Oxford University Press, p. 185</ref> In the opinion of ], a Professor of Medieval History, John's biography of Muhammad is "based on deliberate distortions of Muslim traditions", but Tolan does not elaborate his statement.<ref>John Victor Tolan, Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination, Columbia University Press, p. 139: "Like earlier hostile biographies of Muhammad (John of Damascus, the Risâlat al-Kindî., Theophanes, or the Historia de Mahometh pseudopropheta) the four twelfth-century texts are based on deliberate distortions of Muslim traditions."</ref> | |||

| The earliest surviving written criticisms of Islam are found in the writings of ] such as ]. He viewed Islamic doctrines as a mix of ideas taken from the Bible and claimed that Muhammad was influenced by an Arian monk.<ref name="Writings by St John of Damascus">{{cite book|chapter-url=http://www.orthodoxinfo.com/general/stjohn_islam.aspx|chapter= St. John of Damascus's Critique of Islam|title=Writings by St John of Damascus|series=The Fathers of the Church|volume=37|location=Washington, DC|publisher=Catholic University of America Press|year=1958|pages= 153–160|access-date=8 July 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Other notable early critics of Islam included: | |||

| Other notable early critics included Arabs like ] and ].<ref name="Doubt">{{cite book |last=Hecht |first=Jennifer Michael |url=https://archive.org/details/doubthistory00jenn |title=Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson |publisher=Harper San Francisco |year=2003 |isbn=0-06-009795-7 |page=224 |author-link=Jennifer Michael Hecht}}</ref>{{rp|224}} ], an eleventh-century ] and critic of all religions. His poetry was known for its "pervasive pessimism."<ref name=":3">{{Cite web|title = Abu-L-Ala al-Maarri Facts|url = http://biography.yourdictionary.com/abu-l-ala-al-maarri|website = biography.yourdictionary.com|access-date = 13 July 2015}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2021/entries/abu-bakr-al-razi/|title=The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy|first=Peter|last=Adamson|chapter=Abu Bakr al-Razi |editor-first=Edward N.|editor-last=Zalta|date=1 November 2021|publisher=Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|via=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/150301-aristotle-archimedes-einstein-darwin-ptolemy-razi-ngbooktalk|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210303021204/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/150301-aristotle-archimedes-einstein-darwin-ptolemy-razi-ngbooktalk|url-status=dead|archive-date=3 March 2021|title=Is Islam Hostile to Science?|date=28 February 2015|website=Adventure}}</ref> He believed that Islam does not have a monopoly on truth.<ref name="WarraqPoetry"/><ref>{{Cite book| last=Moosa| first= Ebrahim | title=Ghazālī and the Poetics of Imagination | publisher=UNC Press | year= 2005 | isbn=0-8078-2952-8| page=9}}</ref><ref name="Doubt">{{cite book |last=Hecht |first=Jennifer Michael |url=https://archive.org/details/doubthistory00jenn |title=Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson |publisher=Harper San Francisco |year=2003 |isbn=0-06-009795-7 |page=224 |author-link=Jennifer Michael Hecht}}</ref>{{rp|224}} ] writings, attributed to the philosopher ] ({{Died in|{{circa|756}}}}), include defenses of Manichaeism against Islam and critiques of the Islamic concept of God, characterizing the Quranic deity in highly critical terms.<ref>Tilman Nagel ''Geschichte der islamischen Theologie: von Mohammed bis zur Gegenwart'' C.H. Beck 1994 {{ISBN|9783406379819}} p. 215</ref><ref>], ], ], ] ''Accusations of Unbelief in Islam: A Diachronic Perspective on ''Takfīr'' '' Brill, 30 October 2015 {{ISBN|9789004307834}} p. 61</ref> The Jewish philosopher ], criticized Islam,<ref name="Ibn Warraq p. 3">Ibn Warraq. ''Why I Am Not a Muslim'', p. 3. Prometheus Books, 1995. {{ISBN|0-87975-984-4}}</ref><ref>Norman A. Stillman. ''The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book'' p. 261. Jewish Publication Society, 1979{{ISBN|0-8276-0198-0}}</ref> reasoning that Sharia was incompatible with the principles of justice.<ref name="Ibn Warraq p. 3"/><ref>Norman A. Stillman. ''The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book'' p. 261. Jewish Publication Society, 1979 {{ISBN|0-8276-0198-0}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|doi=10.3390/rel10010063|doi-access=free|title=Muhammad, the Jews, and the Composition of the Qur'an: Sacred History and Counter-History|year=2019|last1=Firestone|first1=Reuven|journal=Religions|volume=10|page=63}}</ref> | |||

| * ], a 9th-century scholar and critic of Islam.<ref name="Doubt">''Doubt: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson'' by Jennifer Michael Hecht, HarperOne, 2004 pg 224</ref> | |||

| * ], a 9th-century atheist, who repudiated Islam and ] in general.<ref name="Doubt" /> | |||

| During the ], Christian church officials commonly represented Islam as a Christian ] or a form of idolatry.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Erwin Fahlbusch|title=The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 2|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year=1999|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=yaecVMhMWaEC|page=759}}|page=759| isbn=9789004116955}}</ref><ref name=":1">Christian Lange ''Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions'' Cambridge University Press, 2015 {{ISBN|9780521506373}} pp. 18–20</ref> They viewed Islam to be a material, rather than spiritual, religion and often explained it in apocalyptic terms.<ref name=":1">Christian Lange ''Paradise and Hell in Islamic Traditions'' Cambridge University Press, 2015 {{ISBN|9780521506373}} pp. 18–20</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author=Erwin Fahlbusch|title=The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 2|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year=1999|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=yaecVMhMWaEC|page=759}}|page=759| isbn=9789004116955}}</ref> In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European academics often portrayed Islam as an exotic Eastern religion distinct from Western religions like Judaism and Christianity, sometimes classifying it as a "Semitic" religion.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii">{{cite book|last=Campo|first=Juan Eduardo|title=Encyclopedia of Islam|year=2009|publisher=Infobase Publishing|pages= xxi – xxxii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC|isbn=9781438126968}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|author=Erwin Fahlbusch|title=The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Volume 2|publisher=Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing|year=1999|url={{google books |plainurl=y |id=yaecVMhMWaEC|page=759}}|page=759| isbn=9789004116955}}</ref> The term "Mohammedanism" was used by many to criticize Islam by focusing on Muhammad's actions, reducing Islam to merely a derivative of Christianity rather than acknowledging it as a successor of Abrahamic monotheisms.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii">{{cite book|last=Campo|first=Juan Eduardo|title=Encyclopedia of Islam|year=2009|publisher=Infobase Publishing|pages= xxi – xxxii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC|isbn=9781438126968}}</ref><ref name="Campo 477">{{cite book|last=Campo|first=Juan Eduardo|title=Encyclopedia of Islam|year=2009|publisher=Infobase Publishing|page= 477|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OZbyz_Hr-eIC|isbn=9781438126968}}</ref> By contrast, many academics nowadays study Islam as an Abrahamic religion in relation to Judaism and Christianity.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/> The Christian apologist ] criticized Islam as a heresy or parody of Christianity,<ref name="Chesterton 1925">], '']'', 1925, Chapter V, ''The Escape from Paganism'', </ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Villis |first1=Tom |title=G. K. Chesterton and Islam |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/336105840 |website=Research Gate |publisher=Modern Intellectual History |access-date=January 16, 2014 |year=2019}}</ref> ] ({{Died in|1776}}), both a ] and a ],<ref>{{Cite book| edition = Summer 2017| publisher = Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University|editor= Edward N. Zalta | last1 = Russell| first1 = Paul| last2 = Kraal| first2 = Anders| title = The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy| chapter = Hume on Religion| access-date = 3 December 2018| date = 2017| chapter-url = https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2017/entries/hume-religion/}}</ref> considered ] religions to be more "comfortable to sound reason" than ] but also found Islam to be more "ruthless" than Christianity.<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = Routledge| isbn = 978-1-134-60914-7| last1 = MacEoin| first1 = Denis| last2 = Al-Shahi| first2 = Ahmed| title = Islam in the Modern World (RLE Politics of Islam)| date = 24 July 2013 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=AZQqAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA22}}</ref> | |||

| ===Medieval world=== | |||

| The ] bishop ] accepted Muhammed as a prophet, but did not consider his mission to be universal and regarded Christian law superior to Islamic law.<ref>Hugh Goddard ''A History of Christian-Muslim Relations'' New Amsterdam Books, 5 September 2000 {{ISBN|9781461636212}} p. 65.</ref> ], a twelfth-century ], did not question the strict monotheism of Islam, and considered Islam to be a instrument of divine providence for bringing all of humankind to the worship of the one true God, but was critical of the practical ] of Muslim regimes and considered ] and politics to be inferior to their Jewish counterparts.<ref name="Maimonides">, by David Novak. Retrieved 29 April 2006.</ref> | |||

| ==== Medieval Islamic world ==== | |||

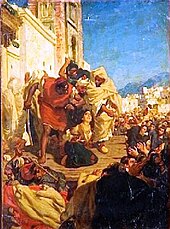

| ] in ], ]]] | |||

| In the early centuries of the Islamic ], the ] allowed citizens to freely express their views, including criticism of Islam and religious authorities, without fear of persecution.<ref name=Boisard>{{Cite journal|title=On the Probable Influence of Islam on Western Public and International Law|first=Marcel A.|last=Boisard|journal=International Journal of Middle East Studies|volume=11|issue=4|date=July 1980|pages=429–50|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref><ref></ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=Justice and Democracy|last=Ronald Bontekoe|first=Mariėtta Tigranovna Stepaniants|publisher=]|year=1997|isbn=0-8248-1926-8|page=251|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> As such, there have been several notable Muslim critics and skeptics of Islam that arose from within the Islamic world itself. In tenth and eleventh-century ] there lived a blind poet called ]. He became well known for a poetry that was affected by a "pervasive pessimism." He labeled religions in general as "noxious weeds" and said that Islam does not have a monopoly on truth. He had particular contempt for the '']'', writing that: | |||

| In his essay ''Islam Through Western Eyes'', the cultural critic ] suggests that the Western view of Islam is particularly hostile for a range of religious, psychological and political reasons, all deriving from a sense "that so far as the West is concerned, Islam represents not only a formidable competitor but also a late-coming challenge to Christianity." In his view, the general basis of ] thought forms a study structure in which Islam is placed in an inferior position as an object of study, thus forming a considerable bias in Orientalist writings as a consequence of the scholars' cultural make-up.<ref>{{cite web |author=Edward W. Said |date=2 January 1998 |title=Islam Through Western Eyes |url=http://www.thenation.com/article/islam-through-western-eyes?page=full |work=The Nation}}</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|They recite their sacred books, although the fact informs me that these are fiction from first to last. O Reason, thou (alone) speakest the truth. Then perish the fools who forged the religious traditions or interpreted them!<ref name="WarraqPoetry"/><ref>{{Cite book| last=Moosa| first= Ebrahim | title=Ghazālī and the Poetics of Imagination | publisher=UNC Press | year= 2005 | isbn=0-8078-2952-8| page=9}}</ref>}} | |||

| ==Points of criticism== | |||

| Another early critic was the ] ] in the 10th century. He criticized Islam and all revealed religions in general in several treatises.<ref>Jennifer Michael Hecht, "Doubt: A History: The Great Doubters and Their Legacy of Innovation from Socrates and Jesus to Thomas Jefferson and Emily Dickinson", pg. 227-230</ref> Despite his views, he remained a celebrated ].<ref>{{Cite book|title=Technology, tradition and survival: aspects of material culture in the Middle East and Central Asia|author=] & Keith Stanley McLachlan|publisher=]|year=2003|isbn=0-7146-4927-9|page=38|postscript=<!--None-->}}</ref> In 1280, the ], ], criticized Islam in his book ''Examination of the Three Faiths''. He reasoned that the ] was incompatible with the principles of justice, and that this undercut the notion of Muhammad being the perfect man: "there is no proof that Muhammad attained perfection and the ability to perfect others as claimed."<ref>Ibn Warraq. ''Why I Am Not a Muslim'', p. 3. Prometheus Books, 1995. ISBN 0-87975-984-4</ref><ref>Norman A. Stillman. ''The Jews of Arab Lands: A History and Source Book'' p. 261. Jewish Publication Society, 1979 | |||

| ===The expansion of Islam=== | |||

| ISBN 0-8276-0198-0</ref> The philosopher thus claimed that people converted to Islam from ulterior motives: | |||

| In an alleged dialogue between the Byzantine emperor ] ({{Reign|1391|1425}}) and a Persian scholar, the emperor criticized Islam as a faith spread by the sword.<ref>Dialogue 7 of Twenty-six Dialogues with a Persian (1399), for the Greek text see Trapp, E., ed. 1966. Manuel II. Palaiologos: Dialoge mit einem "Perser." Wiener Byzantinische Studien 2. Vienna, for a Greek text with accompanying French translation see Th. Khoury "Manuel II Paléologue, Entretiens avec un Musulman. 7e Controverse", Sources Chrétiennes n. 115, Paris 1966, for an English translation see Manuel Paleologus, Dialogues with a Learned Moslem. Dialogue 7 (2009), chapters 1–18 (of 37), translated by Roger Pearse available at the ] , at , and also {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131211201618/http://www.scribd.com/doc/40389472/Manuel-Paleologus-Dialogue-with-a-Learned-Muslim-Scholar-Dialogue-7-15th-century |date=11 December 2013 }}. A somewhat more complete translation into French is found {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303210137/http://www.cypress.fr/UserFiles/File/manuel-paleologue.html |date=2016-03-03 }}</ref><!-- It might be good to mention the primary source which cites this dialogue. --> This matches the common view in Europe during the ] about Islam, then synonymous with the ], as a bloody, ruthless, and intolerant religion.<ref name="Hume 2007">{{Cite book| publisher = Clarendon Press| isbn = 978-0-19-925188-9| last = Hume| first = David| title = A Dissertation on the Passions: The Natural History of Religion : a Critical Edition| date = 2007 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=K-VbQ2TPA70C&pg=PA139}}</ref> More recently, in 2006, a similar statement of Manuel II,{{efn|"Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new, and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached," he said.}} quoted publicly by ], prompted a negative response from Muslim figures who viewed the remarks as an insulting mischaracterization of Islam.<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk">{{Cite news |date=16 September 2006 |title=In quotes: Muslim reaction to Pope |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/5348436.stm |via=news.bbc.co.uk}}</ref><ref name="BBC1">{{Cite news |date=17 September 2006 |title=Pope sorry for offending Muslims |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/5353208.stm |via=news.bbc.co.uk}}</ref> In this vein, the ]n social reformer ] ({{Died in|1897}}) thought that Islam was grown through violence and desire for wealth,<ref>"Américo Castro and the Meaning of Spanish Civilization", by José Rubia Barcia, Selma Margaretten, p. 150.</ref> while the ]n author ] considers Islam as a "superstition" that it is mainly spread with violence and force.<ref>"Debating the African Condition: Race, gender, and culture conflict", by Alamin M. Mazrui, Willy Mutunga, p. 105</ref> | |||

| This "conquest by the sword" thesis is opposed by some historians who consider the transregional development of Islam a multi-faceted and complex phenomenon.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/> The first wave of expansion, the migration of the early Muslims to ] to escape persecution in ] and the subsequent conversion of Medina, was indeed peaceful. In the years to come, Muslims defended themselves against frequent Meccan incursions until Mecca's peaceful surrender in 630. By the time of his death in 632, many of the Arabian tribes had formed political alliances with Muhammad and adopted Islam peacefully, which also paved the way for the subsequent conquests of ], ], ] and (the rest of ]) after the death of Muhammad.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/> Islam nevertheless often remained a minority religion in conquered territories for several centuries after the initial waves of conquest, indicating that the conquest of territories beyond the Arabian Peninsula did not instantly result in large conversions to Islam.{{efn|Scholarly research suggests that there was an inverse relationship between where Muslim political power centres were and where the most conversions occurred, which was on the political periphery.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/> According to the Encyclopaedia of Islam, conquest was just one of several elements that helped Islam spread throughout the world. The systematisation of Islamic tradition, trade, interfaith marriage, political patronage, urbanisation, and the pursuit of knowledge must also be acknowledged. Along trade routes and even in the most isolated regions, Sufis contributed to the spread of Islam. The yearly hajj to Mecca, which brought together scholars, mystics, businesspeople, and regular believers from various nations, should be particularly noted as a contributing factor. Despite taking on more contemporary forms, these factors are still in force today. The expansion of Islam into western Europe, the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand has been facilitated by them.<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/>}}<ref name="Campo xxi – xxxii"/> | |||

| {{quotation|That is why, to this day we never see anyone converting to Islam unless in terror, or in quest of power, or to avoid heavy taxation, or to escape humiliation, or if taken prisoner, or because of infatuation with a Muslim woman, or for some similar reason. Nor do we see a respected, wealthy, and pious non-Muslim well versed in both his faith and that of Islam, going over to the Islamic faith without some of the aforementioned or similar motives.<ref name="Ibn Kammuna" />}} | |||

| === Scripture === | |||

| According to ], just as it is natural for a Muslim to assume that the converts to his religion are attracted by its truth, it is equally natural for the convert's former coreligionists to look for baser motives and ]'s list seems to cover most of such nonreligious motives.<ref>], ''The Jews of Islam'', p.95</ref> | |||

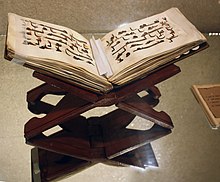

| ]n Quran]] | |||

| {{Main|Criticism of the Quran}} | |||

| ], one of the foremost 12th century ]nical ] and philosophers, sees the relation of Islam to Judaism as primarily theoretical. Maimonides has no quarrel with the strict monotheism of Islam, but finds fault with the practical politics of Muslim regimes. He also considered ] and politics to be inferior to their Jewish counterparts. Maimonides criticised what he perceived as the lack of virtue in the way Muslims rule their societies and relate to one another.<ref name="Maimonides">, by David Novak. Retrieved April 29, 2006.</ref> In his Epistle to Yemenite Jewry, he refers to Mohammad, as "''hameshuga''" – "that madman".<ref>{{Cite book| publisher = Jewish Publication Society | isbn = 978-0-8276-0430-8 | last1 = Hartman | first1 = David | last2 = Halkin | first2 = Abraham S. | title = Epistles of Maimonides: crisis and leadership | year = 1993 | page = 5}}</ref> | |||

| {{See also|History of the Quran|The Syro-Aramaic Reading of the Koran|Historicity of Muhammad}} | |||

| In the lifetime of Muhammad, the Quran was primarily preserved orally and the written compilation of the whole Quran in its current form took place some 150 to 300 years later, according to some sources.<ref>] "Towards a Prehistory of Islam," Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam, vol.17, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 1994 p. 108.</ref><ref>] The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1978 p. 119</ref><ref>], ''Meccan Trade and the Rise of Islam,'' Princeton University Press, 1987 p. 204.</ref> Alternatively, others believe that the Quran was compiled shortly after the death of Muhammad in 632 and canonized by end of the caliphate of ] ({{Reign|644|656}}).{{Sfn|Modarressi|1993|pp=16{{ndash}}18}}{{Sfn|Amir-Moezzi|2009|p=14}}{{Sfn|Pakatchi|2015}} The idea that Quran is perfect and impossible to imitate as asserted in the Quran itself is disputed by critics.<ref>See the verses {{Cite quran|2|2|style=ns}}, {{Cite quran|17|88|end=89|style=ns}}, {{Cite quran|29|47|style=ns}}, {{Cite quran|28|49|style=ns}}</ref> One such criticism is that sentences about God in the Quran are sometimes followed immediately by those in which God is the speaker.<ref name="JE">. From the ''Jewish Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 21 January 2008.</ref> The modern historian ] believes that the Quran is in part a ] of other sacred scriptures, in particular the ] scriptures.<ref>Wansbrough, John (1977). ''Quranic Studies: Sources and Methods of Scriptural Interpretation''</ref><ref name="Wansbrough">Wansbrough, John (1978). ''The Sectarian Milieu: Content and Composition of Islamic Salvation History''.</ref> The Christian theologian ] ({{Died in|1893}}) praises the Quran for its poetic beauty, religious fervor, and wise counsel, but considers this mixed with "absurdities, bombast, unmeaning images, and low sensuality."<ref name="Schaff 1910 4.III.44">Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 44 "The Koran, And The Bible"</ref> The Iranian journalist ] ({{Died in|1982}}) criticized the Quran, saying that "the speaker cannot have been God" in certain passages.<ref name="Warraq - Why I am Not">{{cite book|last1=Warraq|title=Why I am Not a Muslim|publisher=Prometheus Books|isbn=0-87975-984-4|page=106|url=http://download.iranville.com/books/%DA%A9%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%A8%E2%80%8C%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C%20%D8%A7%D9%86%DA%AF%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%B3%DB%8C/Ibn%20Warraq%20-%20Why%20I%20Am%20Not%20a%20Muslim.pdf|year=1995|access-date=16 January 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150117072713/http://download.iranville.com/books/%DA%A9%D8%AA%D8%A7%D8%A8%E2%80%8C%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C%20%D8%A7%D9%86%DA%AF%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%B3%DB%8C/Ibn%20Warraq%20-%20Why%20I%20Am%20Not%20a%20Muslim.pdf|archive-date=17 January 2015|url-status=dead}}</ref> Similarly, the secular author ] gives Surah ] as an example of a passage which is "clearly addressed to God, in the form of a prayer."<ref name="Warraq - Why I am Not" /> The orientalist ] believes that the Quran contains many verses which are incomprehensible, a view rejected by Muslims and many other orientalists.<ref name="Lester">{{cite magazine |last=Lester |first=Toby |author-link=Toby Lester |date=January 1999 |title=What is the Koran? |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/doc/199901/koran |magazine=]}}</ref> '']'', a medieval polemical work, describes the narratives in the Quran as "all jumbled together and intermingled," and regards this as "evidence that many different hands have been at work therein."<ref>Quoted in A. Rippin, ''Muslims: their religious beliefs and practices: Volume 1'', London, 1991, p. 26.</ref> | |||

| ==== |

====Pre-existing sources==== | ||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Medieval Christian views on Muhammad}} | |||

| Critics point to various pre-existing sources to argue against the ]. Some scholars have calculated that one third of the Quran has pre-Islamic Christian origins.<ref>G. Luling asserts that a third of the Quran is of pre-Islamic Christian origins, see ''Über den Urkoran'', Erlangen, 1993, 1st ed., 1973, p. 1.</ref> Aside from the Bible, the Quran relies on several ]l and sources, like the ],<ref name="Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34">Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34.</ref> ],<ref name="Leirvik 2010, pp. 33–34"/> and several ]s.<ref>Leirvik 2010, p. 33.</ref> Several narratives rely on Jewish ] sources, like the narrative of Cain learning to bury the body of Abel in ].<ref>Samuel A. Berman, Midrash Tanhuma-Yelammedenu (KTAV Publishing House, 1996), 31–32.</ref><ref>Gerald Friedlander, Pirḳe de-R. Eliezer, (The Bloch Publishing Company, 1916) 156</ref> ] argues that the dependence of the Quran on preexisting sources is one evidence of a purely human origin.<ref>Geisler, N. L. (1999). "Qur'an, Alleged Divine Origin of". In: ''Baker Encyclopedia of Christian Apologetics''. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books.</ref> ] regards this reliance on pre-Islamic Christian sources as evidence that Islam derived from a ] sect of Christianity.<ref>, in ''richardcarrier.info''</ref> | |||

| ] shown holding a copy of the ''Divine Comedy'', next to the entrance to Hell, the seven terraces of Mount Purgatory and the city of Florence, with the spheres of Heaven above, in ]'s fresco]] | |||

| * In ]'s '']'', Muhammad is portrayed as split in half, with his guts hanging out, representing his status as a ] (one who ] from the ]). | |||

| * Some medieval ecclesiastical writers portrayed Muhammad as possessed by ], a "precursor of the ]" or the Antichrist himself.<ref name="Oussani">, by Gabriel Oussani, ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved April 16, 2006.</ref> | |||

| * ] wrote two treatises to refute Islam at the request of ], ''Contra perfidiam Mahometi, et contra multa dicta Sarracenorum libri quattuor'' and ''Dialogus disputationis inter Christianum et Sarracenum de lege Christi et contra perfidiam Mahometi''.<ref>both in vol. 36 of the Tournai edition, pp. 231-442 and 443-500.</ref> | |||

| * The ''Tultusceptrum de libro domni Metobii'', an Andalusian ] with unknown dating, shows how Muhammad (called Ozim, from ]) was tricked by ] into adulterating an originally pure divine revelation. The story argues God was concerned about the spiritual fate of the Arabs and wanted to correct their derivation from the faith. He then sends an angel to the monk Osius who orders him to preach to the Arabs. Osius however is in ill-health and orders a young monk, Ozim, to carry out the angel's orders instead. Ozim sets out to follow his orders, but gets stopped by an evil angel on the way. The ignorant Ozim believes him to be the same angel that spoke to Osius before. The evil angel modifies and corrupts the original message given to Ozim by Osius, and renames Ozim Muhammad. From this followed the erroneous teachings of Islam, according to the ''Tultusceptrum''.<ref>J. Tolan, ''Medieval Christian Perceptions of Islam'' (1996) p. 100-101</ref> | |||

| * According to many Christians, the coming of Muhammad was foretold in the Holy Bible. According to the monk ] this is in ] 16:12, which describes ] as "a wild man" whose "hand will be against every man". Bede says about Muhammad: "Now how great is his hand against all and all hands against him; as they impose his authority upon the whole length of Africa and hold both the greater part of Asia and some of Europe, hating and opposing all."<ref>J. Tolan, ''Saracens; Islam in the Medieval European Imagination'' (2002) p. 75</ref> | |||

| * In 1391 a dialogue was believed to have occurred between Byzantine Emperor ] and a Persian scholar in which the Emperor stated: | |||

| ==== Criticism of the Hadith ==== | |||

| {{quotation|Show me just what Muhammad brought that was new and there you will find things only evil and inhuman, such as his command to spread by the sword the faith he preached. God is not pleased by blood - and not acting reasonably is contrary to God's nature. Faith is born of the soul, not the body. Whoever would lead someone to faith needs the ability to speak well and to reason properly, without violence and threats... To convince a reasonable soul, one does not need a strong arm, or weapons of any kind, or any other means of threatening a person with death.<ref>Dialogue 7 of Twenty-six Dialogues with a Persian (1399), for the Greek text see Trapp, E., ed. 1966. Manuel II. Palaiologos: Dialoge mit einem “Perser.” Wiener Byzantinische Studien 2. Vienna, for a Greek text with accompanying French translation see Th. Khoury “Manuel II Paléologue, Entretiens avec un Musulman. 7e Controverse”, Sources Chrétiennes n. 115, Paris 1966, for an English translation see Manuel Paleologus, Dialogues with a Learned Moslem. Dialogue 7 (2009), chapters 1-18 (of 37), translated by Roger Pearse available at the ] , at , and also . A somewhat more complete translation into French is found </ref>}} | |||

| {{Main|Criticism of Hadith}}{{See also|Historiography of early Islam}} | |||

| It has been suggested that there exists around the ] (Muslim traditions relating to the '']'' (words and deeds) of Muhammad) three major sources of corruption: political conflicts, sectarian prejudice, and the desire to translate the underlying meaning, rather than the original words verbatim.<ref name="fedex">Brown, Daniel W. "Rethinking Tradition in Modern Islamic Thought", 1999. pp. 113, 134.</ref> | |||

| === Enlightenment Europe === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In '']'', an essay by ], the Quran is described as an "absurd performance" of a "pretended prophet" who lacked "a just sentiment of morals." Attending to the narration, Hume says, "we shall soon find, that bestows praise on such instances of treachery, inhumanity, cruelty, revenge, bigotry, as are utterly incompatible with civilized society. No steady rule of right seems there to be attended to; and every action is blamed or praised, so far as it is beneficial or hurtful to the true believers."<ref name="HumeStdofTste">{{cite web|url=http://www.csulb.edu/~jvancamp/361r15.html |title=Of the Standard of Taste by David Hume}}</ref> | |||

| Muslim critics of the hadith, known as ], reject its authority on theological grounds, arguing that the Quran itself is sufficient for guidance, as it claims that nothing essential has been omitted.<ref>Quran, ]: 38</ref> They believe that reliance on the Hadith has caused people to deviate from the original intent of God's revelation to Muhammad, which they see as adherence to the Quran alone.<ref>Donmez, Amber C. "The Difference Between Quran-Based Islam and Hadith-Based Islam"</ref><ref>Quran, ]: 38</ref> ] was one of these critics and was denounced as a non-believer by thousands of orthodox clerics.<ref>Ahmad, Aziz. "Islamic Modernism in India and Pakistan, 1857–1964". London: Oxford University Press.</ref> In his work ''Maqam-e Hadith'' he considered any hadith that goes against the teachings of Quran to have been falsely attributed to the Prophet.<ref>Pervez, Ghulam Ahmed. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111113215748/http://www.tolueislam.com/Parwez/mh/mh.htm |date=13 November 2011 }}, {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111004044003/http://www.tolueislam.com/Urdu/mhadith/mh.htm |date=4 October 2011 }}</ref> Kassim Ahmad argued that some hadith promote ideas that conflict with science and create sectarian issues.<ref name="call">Latif, Abu Ruqayyah Farasat. , Masters Assertion, September 2006</ref><ref name="kiss">Ahmad, Kassim. "Hadith: A Re-evaluation", 1986. English translation 1997</ref> | |||

| === Nineteenth and twentieth century === | |||

| During the whole 19th and 20th Century, numerous personalities have criticized muslims and Islam, either the criticism was based on the scriptural evidences, or the basic muslim representation of their culture and religion. While some would suggest the better examples in terms of civilization, economy, awareness, etc, but possess critical view towards muslims. | |||

| ] argues that modern Western scholarship has raised doubts about the historicity and authenticity of hadith,{{sfn|Esposito|1998|p=67}} while ] argued that there is no evidence of legal traditions prior to 722. Schacht concluded that the Sunna attributed to the Prophet consists of material from later periods rather than the actual words and deeds of the Prophet.{{sfn|Esposito|1998|p=67}} However, scholars like ] have argued that a complete dismissal of hadith as late fiction is "unjustified".<ref>{{cite book | last=Madelung| first=Wilferd | title=The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1997 | isbn=0-521-64696-0 | page=xi}}</ref> | |||

| ] in 1900, at ]]] | |||

| Orthodox Muslims do not deny the existence of false hadith, but believe that through the scholars' work, these false hadith have been largely eliminated.<ref>By Nasr, Seyyed Vali Reza, "Shi'ism", 1988. p. 35.</ref><ref>{{cite book | last=Madelung| first=Wilferd | title=The Succession to Muhammad: A Study of the Early Caliphate | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1997 | isbn=0-521-64696-0 | page=xi}}</ref> | |||

| The ] philosopher ] commented on Islam: | |||

| {{quotation|Now, the Muslims are the crudest in this respect, and the most sectarian. Their watch-word is: there is one God (Allah), and Mohammed is His Prophet. Everything beyond that not only is bad, but must be destroyed forthwith, at a moment’s notice, every man or woman who does not exactly believe in that must be killed; everything that does not belong to this worship must be immediately broken; every book that teaches anything else must be burnt. From the Pacific to the Atlantic, for five hundred years blood ran all over the world. That is Mohammedanism.<ref>"Swami Vivekananda's Rousing Call to Hindu Nation", p. 130</ref>}} | |||

| ]s of the Quran]] | |||

| ] calls the concept of Islam to be highly offensive, and doubted that there is any connection of Islam with God: | |||

| The traditional view of Islam has faced scrutiny due to a lack of consistent supporting evidence, such as limited archaeological finds and some discrepancies with non-Muslim sources.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.opendemocracy.net/faith-europe_islam/mohammed_3866.jsp|title=What do we actually know about Mohammed?|work=openDemocracy|access-date=13 November 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090421171853/http://www.opendemocracy.net/faith-europe_islam/mohammed_3866.jsp|archive-date=21 April 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="Donner 1998">Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998</ref>{{rp|23}} In the 1970s, a number of scholars began to re-evaluate established Islamic history, proposing that earlier accounts may have been altered over time.<ref name="Donner 1998">Donner, Fred ''Narratives of Islamic Origins: The Beginnings of Islamic Historical Writing'', Darwin Press, 1998</ref>{{rp|23}}<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.opendemocracy.net/faith-europe_islam/mohammed_3866.jsp|title=What do we actually know about Mohammed?|work=openDemocracy|access-date=13 November 2007|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090421171853/http://www.opendemocracy.net/faith-europe_islam/mohammed_3866.jsp|archive-date=21 April 2009|url-status=dead}}</ref> They sought to reconstruct early Islamic history using alternative sources like coins, inscriptions, and non-Islamic texts. Prominent among these scholars was ].<ref name="Donner 1998"/>{{rp|38}} Additionally, ] study of the Sana'a manuscripts revealed some variations in text and verse order, suggesting that the Quranic text may have evolved over time.<ref name="Lester" /> | |||

| {{quotation|Had the God of the ] been the Lord of all creatures, and been Merciful and kind to all, he would never have commanded the Mohammedans to slaughter men of other faiths, and animals, etc. If he is Merciful, will he show mercy even to the sinners? If the answer be given in the affirmative, it cannot be true, because further on it is said in the Quran "Put infidels to sword," in other words, he that does not believe in the Quran and the Prophet Mohammad is an infidel (he should, therefore, be put to death). (Since the Quran sanctions such cruelty to non-Mohammedans and innocent creatures such as cows) it can never be the Word of God.<ref>Title = "Journal of Indian Council of Philosophical Research, Volume 19, Issue 1", publisher = ICPR, year = 2002, page = 73</ref>}} | |||

| === Criticism of Muhammad === | |||

| ] regarded that Islam was grown through the violence and desire for wealth. He further asserted that Muslims denies the entire islamic prescribed violence and atrocities, and will continue doing so. He wrote:- | |||

| {{See also|Criticism of Muhammad}} | |||

| {{quotation|All educated people start looking down upon the ]s and even started objecting to their very basis. Since then some naturalist Mohammadis are trying, rather opposing falsehood and accepting the truth, to prove unnecessarily and wrongly that Islam never indulged in Jihad and the people were never converted to Islam forcibly. Neither any temples were demolished nor were ever cows slaughtered in the temples. Women and children belonging to other religious sects were never forcibly converted to Islam nor did they ever commit any sexual acts with them as could have been done with the slave-males and females both.<ref>"Américo Castro and the Meaning of Spanish Civilization", by José Rubia Barcia, Selma Margaretten, p. 150</ref>}} | |||

| The Christian missionary ] and the former Muslim ] have criticized Muhammad's actions as immoral.<ref name="Oussani"/><ref name="WarraqQuest"/> In one instance, the Jewish poet ] provoked the Meccan tribe of ] to fight Muslims and wrote ] poetry about their women,<ref name="Ashraf">{{cite encyclopedia |title=Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf |encyclopedia=] Online |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |author-link=William Montgomery Watt |editor=P.J. Bearman |issn=1573-3912 |author=William Montgomery Watt |editor2=Th. Bianquis |editor3=] |editor4=E. van Donzel |editor5=W.P. Heinrichs}}</ref> and was apparently plotting to assassinate Muhammad.<ref name="Rubin">Uri Rubin, The Assassination of Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf, Oriens, Vol. 32. (1990), pp. 65–71.</ref> Muhammad called upon his followers to kill Ka'b,<ref name="Ashraf" /> and he was consequently assassinated by ], an early Muslim.<ref>{{cite book |author=Ibn Hisham |title=Al-Sira al-Nabawiyya |year=1955 |volume=2 |location=Cairo |pages=51–57 |author-link=Ibn Hisham}} English translation from Stillman (1979), pp. 125–26.</ref> Such criticisms were countered by the historian ], who argues on the basis of ] that Muhammad should be judged by the standards and norms of his own time and geography, rather than ours.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Watt |first=W. Montgomery |url=https://archive.org/details/muhammadprophets00watt/page/229 |title=Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1961 |isbn=0-19-881078-4 |page= |access-date=27 May 2010}}</ref> The fourteenth-century poem '']'' by the ] poet ] contains images of Muhammad, picturing him the eighth circle of hell as a ], along with his cousin and son-in-law ].<ref name="auto">G. Stone ''Dante's Pluralism and the Islamic Philosophy of Religion'' Springer, 12 May 2006 {{ISBN|9781403983091}} p. 132</ref><ref name="ReferenceH">Minou Reeves, P. J. Stewart ''Muhammad in Europe: A Thousand Years of Western Myth-Making'' NYU Press, 2003 {{ISBN|9780814775646}} p. 93–96</ref> Dante does not blame Islam as a whole but accuses Muhammad of ] for establishing another religion after Christianity.<ref name="auto" /> Some medieval ecclesiastical writers portrayed Muhammad as possessed by ], a "precursor of the ]" or the Antichrist himself.<ref name="Oussani" /> ']'', an ] manuscript of unknown origins, describes how Muhammad (called Ozim, from ]) was tricked by Satan into adulterating an originally pure divine revelation: God was concerned about the spiritual fate of the Arabs and wanted to correct their deviation from the faith. He then sent an angel to the Christian monk Osius who ordered him to preach to the Arabs. Osius, however, was in ill-health and instead ordered a young monk, Ozim, to carry out the angel's orders. Ozim set out to follow his orders, but was stopped by an evil angel on the way. The ignorant Ozim believed him to be the same angel that had spoken to Osius before. The evil angel modified and corrupted the original message given to Ozim by Osius, and renamed Ozim Muhammad. From this followed the erroneous teachings of Islam, according to ''Tultusceptru''.<ref>J. Tolan, ''Medieval Christian Perceptions of Islam'' (1996) pp. 100–01</ref> | |||

| ===Islamic ethics=== | |||

| The ] ] Sir ] criticised Islam for what he perceived to be an inflexible nature, which he held responsible for stifling progress and impeding social advancement in Muslims countries. The following sentences are taken from the ] he delivered at ] in 1881: | |||

| {{Main|Islamic ethics}} | |||

| {{quotation|Some, indeed, dream of an Islam in the future, rationalised and regenerate. All this has been tried already, and has miserably failed. The Koran has so encrusted the religion in a hard unyielding casement of ordinances and social laws, that if the shell be broken the life is gone. A rationalistic Islam would be Islam no longer. The contrast between our own faith and Islam is most remarkable. There are in our Scriptures living germs of truth, which accord with civil and religious liberty, and will expand with advancing civilisation. In Islam it is just the reverse. The Koran has no such teaching as with us has abolished polygamy, slavery, and arbitrary divorce, and has elevated woman to her proper place. As a Reformer, Mahomet did advance his people to a certain point, but as a Prophet he left them fixed immovably at that point for all time to come. The tree is of artificial planting. Instead of containing within itself the germ of growth and adaptation to the various requirements of time and clime and circumstance, expanding with the genial sunshine and rain from heaven, it remains the same forced and stunted thing as when first planted some twelve centuries ago."<ref name="muir"> Page 458</ref>}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| According to the ], while there is much to be admired and affirmed in Islamic ethics, its originality or superiority is rejected.<ref>. From the ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Retrieved 21 January 2008.</ref> | |||

| Critics stated that the ] allows Muslim men to discipline their wives by striking them.<ref>Kathir, Ibn, "Tafsir of Ibn Kathir", Al-Firdous Ltd., London, 2000, 50–53 – Ibn Kathir states "dharbun ghayru nubrah" strike/admonish lightly</ref> There is however evidence from Islamic hadiths and scholars such as Ibn Kathir that demonstrates that only a twig or leaf can be used by a man to "strike" their wife and this is not allowed to cause pain or injure their wife but to show their frustration.<ref name="Domestic Violence and the Islamic T">{{cite journal|date=2017| title =Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition: Book Review|journal= Journal of Islamic Ethics| volume=1|issue=(1-2)|pages= 203–207| doi= 10.1163/24685542-12340009|doi-access=free}}</ref> Moreover, confusion amongst translations of Quran with the original Arabic term "wadribuhunna" being translated as "to go away from them",<ref>Laleh Bakhtiar, The Sublime Quran, 2007 translation</ref> "beat",<ref>"The Holy Quran: Text, Translation and Commentary", Abdullah Yusuf Ali, Amana Corporation, Brentwood, MD, 1989. {{ISBN|0-915957-03-5}}, passage was quoted from commentary on 4:34 – Abdullah Yusuf Ali in his Quranic commentary also states that: "In case of family jars four steps are mentioned, to be taken in that order. (1) Perhaps verbal advice or admonition may be sufficient; (2) if not, sex relations may be suspended; (3) if this is not sufficient, some slight physical correction may be administered; but Imam Shafi'i considers this inadvisable, though permissible, and all authorities are unanimous in deprecating any sort of cruelty, even of the nagging kind, as mentioned in the next clause; (4) if all this fails, a family council is recommended in 4:35 below." Abdullah Yusuf Ali, The Holy Quran: Text, Translation and Commentary (commentary on 4:34), Amana Corporation, Brentwood, MD, 1989. {{ISBN|0-915957-03-5}}.</ref> "strike lightly" and "separate".<ref>Ammar, Nawal H. (May 2007). "Wife Battery in Islam: A Comprehensive Understanding of Interpretations". Violence Against Women 13 (5): 519–23</ref> The film '']'' critiqued this and similar verses of the Quran by displaying them painted on the bodies of abused Muslim women.<ref name=submission_script>{{cite web|url=http://www.opzij.nl/opzij/show?id=23669&framenoid=19755|title=Welkom bij Opzij|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070927225432/http://www.opzij.nl/opzij/show?id=23669&framenoid=19755|archive-date=27 September 2007}}</ref> | |||

| Some critics argue that the Quran is incompatible with other religious scriptures as it attacks and advocates hate against people of other religions.<ref name="BibleInQuran"/><ref>Gerber (1986), pp. 78–79</ref><ref>"Anti-Semitism". ]</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090318224903/http://www.hudson.org/files/pdf_upload/saudi_textbooks_final.pdf |date=18 March 2009 }} (pdf), ], May 2006, pp. 24–25.</ref> ] interprets certain verses of the Quran as sanctioning military action against unbelievers as it said "Fight those who do not believe in Allah or in the Last Day and who do not consider unlawful what Allah and His Messenger have made unlawful and who do not adopt the religion of truth from those who were given the Scripture – until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled."(])<ref name="Who Are the Moderate Muslims?">Sam Harris </ref> However, the Islamic hadiths and scholars such as Dr Zakir Naik refer to fighting and not to trust "non-believers" and Christians in certain situations or events such as during times of war.<ref>Understanding the Qurán - Page xii, Ahmad Hussein Sakr - 2000</ref> | |||

| ] is a tax for "protection" paid by non-Muslims to a Muslim ruler, for the exemption from military service for non-Muslims, and for the permission to practice a non-Muslim faith with some communal autonomy in a Muslim state.<ref name=anveremon>Anver M. Emon, Religious Pluralism and Islamic Law: Dhimmis and Others in the Empire of Law, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0199661633}}, pp. 99–109.</ref><ref name="ArnoldPoI3">{{cite book | first=Thomas | last=Walker Arnold | author-link=Thomas Walker Arnold | publisher=] | date=1913 | title=Preaching of Islam: A History of the Propagation of the Muslim Faith | url=https://archive.org/details/preachingofislam00arno | pages=–1 | quote=This tax was not imposed on the Christians, as some would have us think, as a penalty for their refusal to accept the Muslim faith, but was paid by them in common with the other <u>dh</u>immīs or non-Muslim subjects of the state whose religion precluded them from serving in the army, in return for the protection secured for them by the arms of the Musalmans.}} ()</ref>{{sfn|Esposito|1998|p=34|ps=. "They replaced the conquered countries, indigenous rulers and armies, but preserved much of their government, bureaucracy, and culture. For many in the conquered territories, it was no more than an exchange of masters, one that brought peace to peoples demoralized and disaffected by the casualties and heavy taxation that resulted from the years of Byzantine-Persian warfare. Local communities were free to continue to follow their own way of life in internal, domestic affairs. In many ways, local populations found Muslim rule more flexible and tolerant than that of Byzantium and Persia. Religious communities were free to practice their faith to worship and be governed by their religious leaders and laws in such areas as marriage, divorce, and inheritance. In exchange, they were required to pay tribute, a poll tax (''jizya'') that entitled them to Muslim protection from outside aggression and exempted them from military service. Thus, they were called the "protected ones" (''dhimmi''). In effect, this often meant lower taxes, greater local autonomy, rule by fellow Semites with closer linguistic and cultural ties than the hellenized, Greco-Roman élites of Byzantium, and greater religious freedom for Jews and indigenous Christians."}} | |||

| ] criticized what he alleged to be the effects Islam had on its believers, which he described as fanatical frenzy combined with fatalistic apathy, enslavement of women, and militant proselytizing.<ref name="Churchill 1899">Winston S. Churchill, from The River War, first edition, Vol. II, pages 248-50 (London: Longmans, Green & Co., 1899)</ref> In his 1899 book '']'' he says: | |||

| Harris argues that ] is simply a consequence of taking the Quran literally, and is skeptical that moderate Islam is possible.{{efn|Various calls to arms were identified in the Quran by US citizen ], all of which were cited as "most relevant to my actions on March 3, 2006" (],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.044|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.044 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.019|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.019 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/057-qmt.php#057.010|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=13 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160413235435/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/057-qmt.php#057.010 |archive-date=13 April 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/008-qmt.php#008.072|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=30 December 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151230210409/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/008-qmt.php#008.072 |archive-date=30 December 2015 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.120|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.120 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/003-qmt.php#003.167|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194019/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/003-qmt.php#003.167 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/004-qmt.php#004.066|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=1 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150501064500/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/004-qmt.php#004.066 |archive-date=1 May 2015 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/004-qmt.php#004.104|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=1 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150501064500/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/004-qmt.php#004.104 |archive-date=1 May 2015 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.081|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.081 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.093|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.093 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.100|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=4 June 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160604194024/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/009-qmt.php#009.100 |archive-date=4 June 2016 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/016-qmt.php#016.110|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=26 October 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121026012552/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/016-qmt.php#016.110 |archive-date=26 October 2012 }}</ref> ],<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/061-qmt.php#061.011|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=30 April 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160430041717/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/061-qmt.php#061.011 |archive-date=30 April 2016 }}</ref> ]).<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/047-qmt.php#047.035|title=Center for Muslim-Jewish Engagement|date=2 May 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160502163036/http://www.usc.edu/org/cmje/religious-texts/quran/verses/047-qmt.php#047.035 |archive-date=2 May 2016 }}</ref><ref>{{cite wikisource |wslink=Mohammed Reza Taheri-azar- Letter to The daily Tar Heel |title=Letter to The daily Tar Heel |first=Mohammed Reza |last=Taheri-azar |authorlink=Mohammed Reza Taheri-azar SUV attack#Perpetrator |year=2006}}</ref>}}<ref name=Harris1>{{Cite book | last=Harris | first=Sam | title=The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason | pages= | publisher=W. W. Norton; Reprint edition | year=2005 | isbn=0-393-32765-5 | url=https://archive.org/details/endoffaithreligi00harr/page/31 }}</ref> | |||

| ] on a ] of the ] in 1900]] | |||

| Max I. Dimont interprets that the ]s described in the Quran are specifically dedicated to "male pleasure".<ref>The Indestructible Jews, by Max I. Dimont, p. 134</ref> According to Pakistani Islamic scholar Maulana Umar Ahmed Usmani "Hur" or "hurun" is the plural of both "ahwaro" which is a masculine form and also "haurao" which is a feminine, meaning both pure males and pure females. Basically, the word 'hurun' means white, he says.<ref name="dawn-houri-20">{{cite web |title=Are all 'houris' female? |url=https://www.dawn.com/news/635343 |website=Dawn.com |access-date=22 April 2019 |date=9 June 2011}}</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|How dreadful are the curses which Mohammedanism lays on its votaries! Besides the fanatical frenzy, which is as dangerous in a man as hydrophobia in a dog, there is this fearful fatalistic apathy. The effects are apparent in many countries. Improvident habits, slovenly systems of agriculture, sluggish methods of commerce, and insecurity of property exist wherever the followers of the Prophet rule or live. A degraded sensualism deprives this life of its grace and refinement; the next of its dignity and sanctity. The fact that in Mohammedan law every woman must belong to some man as his absolute property - either as a child, a wife, or a concubine - must delay the final extinction of slavery until the faith of Islam has ceased to be a great power among men. Thousands become the brave and loyal soldiers of the faith: all know how to die but the influence of the religion paralyses the social development of those who follow it. No stronger retrograde force exists in the world. Far from being moribund, Mohammedanism is a militant and proselytizing faith. It has already spread throughout Central Africa, raising fearless warriors at every step; and were it not that Christianity is sheltered in the strong arms of science, the science against which it had vainly struggled, the civilisation of modern Europe might fall, as fell the civilisation of ancient Rome.<ref name="Churchill 1899" />}} | |||

| === Views on slavery === | |||

| ]]] | |||

| {{Main|Islamic views on slavery|History of slavery in the Muslim world|History of concubinage in the Muslim world|Mamluk}} | |||

| ] writer ] regarded Islam as the corrupter of ], he said: | |||

| ] in ]]] | |||

| According to ], the Islamic injunctions against the enslavement of Muslims led to massive importation of slaves from the outside.<ref>Lewis, Bernard (1990). Race and Slavery in the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press. {{ISBN|0-19-505326-5}}, p. 10.</ref> Also ] believes that Islam seems to have done more to protect and expand slavery than the reverse.<ref>Manning, Patrick (1990). Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-34867-6}}, p. 28</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|Every aspect of life and thought, including women's condition, changed after Islam. Enslaved by men, women were confined to the home. Polygamy, injection of fatalistic attitude, mourning, sorrow and grief led people to seek solace in magic, witchcraft, prayer, and supernatural beings.<ref>"Words, Not Swords: Iranian Women Writers and the Freedom of Movement", p. 64, by Farzaneh Milani</ref>}} | |||

| Brockopp, on the other hand believe that the idea of using alms for the manumission of slaves appears to be unique to the Quran ({{Quran-usc|2|177}} and {{Quran-usc|9|60}}). Similarly, the practice of freeing slaves in atonement for certain sins appears to be introduced by the Quran (but compare Exod 21:26-7).<ref name="Brockopp"/> Also the forced prostitution of female slaves, a Near Eastern custom of great antiquity, is condemned in the Quran.<ref name="Esposito">John L Esposito (1998) p. 79</ref> According to Brockopp "the placement of slaves in the same category as other weak members of society who deserve protection is unknown outside the Qur'an.<ref name="Brockopp">], ''Slaves and Slavery''</ref> Some slaves had high social status in the ], such as the ] ] ],<ref name="Levanoni 2010">{{cite book |last=Levanoni |first=Amalia |year=2010 |chapter=PART II: EGYPT AND SYRIA (ELEVENTH CENTURY UNTIL THE OTTOMAN CONQUEST) – The Mamlūks in Egypt and Syria: the Turkish Mamlūk sultanate (648–784/1250–1382) and the Circassian Mamlūk sultanate (784–923/1382–1517) |editor-last=Fierro |editor-first=Maribel |title=The New Cambridge History of Islam, Volume 2: The Western Islamic World, Eleventh to Eighteenth Centuries |location=] and ] |publisher=] |pages=237–284 |doi=10.1017/CHOL9780521839570.010 |isbn=978-1-139-05615-1 |quote=The Arabic term ''mamlūk'' literally means 'owned' or 'slave', and was used for the ] ] ] of ], purchased from ] and the ] by ] to serve as soldiers in their armies. Mamlūk units formed an integral part of Muslim armies from the third/ninth century, and Mamlūk involvement in government became an increasingly familiar occurrence in the ] ]. The road to absolute rule lay open before them ] when the Mamlūk establishment gained military and political domination during the reign of the ], al-Ṣāliḥ Ayyūb (r. 637–47/1240–9).}}</ref> who were assigned high-ranking military and administrative duties by the ruling Arab and ] dynasties.<ref name="Ayalon 2012">{{cite encyclopedia |author-last=Ayalon |author-first=David |author-link=David Ayalon |year=2012 |origyear=1991 |title=Mamlūk |editor1-last=Bosworth |editor1-first=C. E. |editor1-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth |editor2-last=van Donzel |editor2-first=E. J. |editor2-link=Emeri Johannes van Donzel |editor3-last=Heinrichs |editor3-first=W. P. |editor3-link=Wolfhart Heinrichs |editor4-last=Lewis |editor4-first=B. |editor4-link=Bernard Lewis |editor5-last=Pellat |editor5-first=Ch. |editor5-link=Charles Pellat |encyclopedia=] |location=] |publisher=] |volume=6 |doi=10.1163/1573-3912_islam_COM_0657 |isbn=978-90-04-08112-3}}</ref> | |||

| Critics argue unlike Western societies there have been no anti-slavery movements in Muslim societies,<ref>Murray Gordon, "Slavery in the Arab World." New Amsterdam Press, New York, 1989. Originally published in French by Editions Robert Laffont, S.A. Paris, 1987, p. 21.</ref> | |||

| The ], ] described Islam as spread by violence and fanaticism, and producing a variety of social ills in the regions it conquered.<ref name="Schaff 1910 4.III.40">Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 40 "Position of Mohammedanism in Church History"</ref> | |||

| which according to Gordon was due to the fact that it was deeply anchored in Islamic law, thus there was no ideological challenge ever mounted against slavery.<ref>Murray Gordon, "Slavery in the Arab World." New Amsterdam Press, New York, 1989. Originally published in French by Editions Robert Laffont, S.A. Paris, 1987, pp. 44–45.</ref> According to sociologist Rodney Stark, "the fundamental problem facing Muslim theologians vis-à-vis the morality of slavery" is that Muhammad himself engaged in activities such as purchasing, selling, and owning slaves, and that his followers saw him as the perfect example to emulate. Stark contrasts Islam with ], writing that Christian theologians wouldn't have been able to "work their way around the biblical acceptance of slavery" if ] had owned slaves, as Muhammad did.<ref>Rodney Stark, "For the Glory of God: How Monotheism Led to Reformations, Science, Witch-Hunts, and the End of Slavery", p. 338, 2003, ], {{ISBN|0691114366}}</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|Mohammedanism conquered the fairest portions of the earth by the sword and cursed them by polygamy, slavery, despotism and desolation. The moving power of Christian missions was love to God and man; the moving power of Islâm was fanaticism and brute force.<ref name="Schaff 1910 4.III.40"/>}} | |||

| ] priest, scholar and hymn-writer ]]] | |||

| Schaff also described Islam as a derivative religion based on an amalgamation of "heathenism, Judaism and Christianity."<ref name="Schaff 1910 4.III.45">Schaff, P., & Schaff, D. S. (1910). History of the Christian church. Third edition. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. Volume 4, Chapter III, section 45 "The Mohammedanism Religion"</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|lslâm is not a new religion...t is a compound or mosaic of preëxisting elements, a rude attempt to combine heathenism, Judaism and Christianity, which Mohammed found in Arabia, but in a very imperfect form.<ref name="Schaff 1910 4.III.45"/>}} | |||

| Only in the early 20th century did slavery gradually became outlawed and suppressed in Muslim lands, with Muslim-majority ] being the last country in the world to formally abolish slavery in 1981.<ref name="eois" /> | |||

| ] criticized Islam in terms similar to those of Schaff, arguing that it was made up of a mixture of beliefs that provided something for everyone.<ref name="Neale 1847 V.II p.68">] (1847). A History of the Holy Eastern Church: The Patriarchate of Alexandria. London: Joseph Masters. Volume II, Section I "Rise of Mahometanism" (p. 68)</ref> {{quotation|...he also infuses into his religion so much of each of those tenets to which the varying sects of his countrymen were addicted, as to enable each and all to please themselves by the belief that the new doctrine was only a reform of, and improvement on, that to which they had been accustomed. The Christians were conciliated by the acknowledgment of our LORD as the Greatest of Prophets; the Jews, by the respectful mention of Moses and their other Lawgivers; the idolaters, by the veneration which the Impostor professed for the Temple of Mecca, and the black stone which it contained; and the Chaldeans, by the pre-eminence which he gives to the ministrations of the Angel Gabriel, and his whole scheme of the Seven Heavens. To a people devoted to the gratification of their passions and addicted to Oriental luxury, he appealed, not unsuccessfully, by the promise of a Paradise whose sensual delights were unbounded, and the permission of a free exercise of pleasures in this world.<ref name="Neale 1847 V.II p.68"/>}} | |||

| Murray Gordon characterizes Muhammad's approach to slavery as reformist rather than revolutionary that abolish slavery, but rather improved the conditions of slaves by urging his followers to treat their slaves humanely and free them as a way of expiating one's sins.<ref>{{cite book|author=Murray Gordon|title=Slavery in the Arab World|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5l81hwFPvzYC&pg=PA19|pages=19–20|publisher=Rowman & Littlefield|year=1989|isbn=9780941533300}}</ref> | |||

| In ], slavery was theoretically an exceptional condition under the dictum ''The basic principle is liberty''.<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|author=Brunschvig, R.| year=1986 | title=ʿAbd |encyclopedia=Encyclopaedia of Islam| edition=2nd|publisher=Brill |editor=P. Bearman |editor2=Th. Bianquis |editor3=C.E. Bosworth |editor4=E. van Donzel |editor5=W.P. Heinrichs|volume=1|pages=26}}</ref><ref name=OEIW/> | |||

| ], the most acknowledged freedom fighter of India, he found the history of Muslims to be aggressive, while he pointed that Hindus have passed that stage of societal evolution:- | |||

| Reports from Sudan and Somalia showing practice of slavery is in border areas as a result of continuing war<ref>], ''slavery'', p. 298</ref> and not Islamic belief. In recent years, except for some conservative ] Islamic scholars,{{efn|In a 2014 issue of their digital magazine '']'', the ] explicitly claimed religious justification for enslaving ] women.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.newsweek.com/islamic-state-seeks-justify-enslaving-yazidi-women-and-girls-iraq-277100|title=Islamic State Seeks to Justify Enslaving Yazidi Women and Girls in Iraq|work=]|date=13 October 2014}}</ref><ref>Allen McDuffee, '']'', 13 October 2014</ref><ref>Salma Abdelaziz, '']'', 13 October 2014</ref><ref>Richard Spencer, '']'', 13 October 2014.</ref>}} | |||

| {{quotation|Though, in my opinion, non violence has a predominant place in the Quran, the thirteen hundred years of imperialistic expansion has made the Muslims fighters as a body. They are therefore aggressive. Bullying is the natural excrescence of an aggressive spirit. The Hindu has an ages old civilization. He is essentially non violent. His civilization has passed through the experiences that the two recent ones are still passing through. If Hinduism was ever imperialistic in the modern sense of the term, it has outlived its imperialism and has either deliberately or as a matter of course given it up. Predominance of the non violent spirit has restricted the use of arms to a small minority which must always be subordinate to a civil power highly spiritual, learned and selfless. The Hindus as a body are therefore not equipped for fighting. But not having retained their spiritual training, they have forgotten the use of an effective substitute for arms and not knowing their use nor having an aptitude for them, they have become docile to the point of timidity and cowardice. This vice is therefore a natural excrescence of gentleness.<ref>The Gandhian Moment, p. 117, by Ramin Jahanbegloo</ref><ref>Gandhi's responses to Islam, p.110, by Sheila McDonough</ref>}} | |||

| most Muslim scholars found the practice "inconsistent with Qur'anic morality".<ref>Abou el Fadl, ''Great Theft'', HarperSanFrancisco, 2005.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/economicHistory/GEHN/GEHNPDF/Islam&SlaveryWGCS.pdf|title=Department of Economic History|access-date=9 March 2022|archive-date=25 March 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090325013630/http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/economicHistory/GEHN/GEHNPDF/Islam%26SlaveryWGCS.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>Khaled Abou El Fadl and William Clarence-Smith</ref> | |||

| ] in his book "Discovery of India", describes Islam to have been faith for military conquests, he wrote "Islam had become a more rigid faith suited more to military conquests rather than the conquests of the mind," and that Muslims brought nothing new to his country. | |||

| {{quotation|The Muslims who came to India from outside brought no new technique or political or economic structure. Inspite of religious belief in the brotherhood of Islam, they were class bound and feudal in outlook.<ref>"Narrative Construction of India: Forster, Nehru, and Rushdie", p. 160, by Mukesh Srivastava, 2004</ref>}} | |||

| === Modern world === | |||

| ==== Modern Christianity ==== | |||

| The early 20th-century ] James L. Barton argued that Islam's view of the sovereignty of God is so extreme and unbalanced as to produce a fatalism that stifles human initiative:<ref name="Barton 1918">Barton, J. L. (1918). The Christian Approach to Islam (p. 139). Boston; Chicago: The Pilgrim Press.</ref> | |||

| {{quotation|Man is reduced to a cipher. Human agency and human freedom are nullified. Right is no longer right because it is right, but because Allah wills it to be right. It is for this reason that monotheism has in Islam stifled human effort and progress. It has become a deadening doctrine of fate. Man must believe and pray, but these do not insure salvation or any benefit except Allah wills it. Why should human effort strive by sanitary means to prevent disease, when death or life depends in no way on such measures but upon the will of Allah? One reason why Moslem countries are so stagnant and backward in all that goes to make up a high civilization is owing to the deadening effects of monotheism thus interpreted. ... even in the most extreme forms of the Augustinian and Calvinistic systems there were always present in Christianity other elements which prevented the conception of the divine sovereignty from paralyzing the healthy activities of life as the Mohammedan doctrine has done.<ref name="Barton 1918"/>}} | |||

| ] criticized Islam as a derivative from Christianity. He described it as a heresy or parody of Christianity. In '']'' he says: | |||

| {{quotation|Islam was a product of Christianity; even if it was a by-product; even if it was a bad product. It was a heresy or parody emulating and therefore imitating the Church...Islam, historically speaking, is the greatest of the Eastern heresies. It owed something to the quite isolated and unique individuality of Israel; but it owed more to Byzantium and the theological enthusiasm of Christendom. It owed something even to the Crusades.<ref name="Chesterton 1925">], '']'', 1925, Chapter V, ''The Escape from Paganism'', </ref>}} | |||

| During a ] given at the ] in 2006, ] quoted an unfavorable remark about ] made at the end of the 14th century by ], the ].<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk"></ref><ref name="BBC1"></ref> As the English translation of the Pope's lecture was disseminated across the world, many ] protested against what they saw as an insulting mischaracterization of Islam.<ref name="news.bbc.co.uk"/><ref name="BBC1"/> Mass street protests were mounted in many Islamic countries, the '']'' (]i parliament) unanimously called on the Pope to retract "this objectionable statement".<ref></ref> | |||

| ==== Modern Hinduism ==== | |||

| ] winning novelist, ] stated that Islam requires its adherents to destroy everything which is not related to it. He described it as having a: | |||