| Revision as of 20:28, 25 April 2019 edit87.222.89.125 (talk) →Y-Chromosome haplogroupsTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:43, 15 January 2025 edit undoOAbot (talk | contribs)Bots442,414 editsm Open access bot: hdl updated in citation with #oabot. | ||

| (464 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Ancestry of Spanish and Portuguese people}} | |||

| The ancestry of modern Iberians (comprising the ] and ]) is consistent with the geographical situation of the ] in the south-west corner of Europe. The large predominance of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R1b, common throughout ], is the result of ]an invaders during the ], making the Spanish and Portuguese population closely related to others from Western Europe.<ref>Nelis, Mari; Esko, Tõnu; Mägi, Reedik; Zimprich, Fritz; Zimprich, Alexander; Toncheva, Draga; Karachanak, Sena; Piskácková, Tereza; Balascák, Ivan; Peltonen, L; Jakkula, E; Rehnström, K; Lathrop, M; Heath, S; Galan, P; Schreiber, S; Meitinger, T; Pfeufer, A; Wichmann, HE; Melegh, B; Polgár, N; Toniolo, D; Gasparini, P; d'Adamo, P; Klovins, J; Nikitina-Zake, L; Kucinskas, V; Kasnauskiene, J; Lubinski, J; Debniak, T (2009). Fleischer, Robert C., ed. "Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East". PLoS ONE. 4 (5): e5472. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.5472N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. PMC 2675054. {{PMID|19424496}}.</ref><ref>Wade, Nicholas (13 August 2008). "The Genetic Map of Europe". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 October 2009.</ref><ref>Novembre, John; Johnson, Toby; Bryc, Katarzyna; Kutalik, Zoltán; Boyko, Adam R.; Auton, Adam; Indap, Amit; King, Karen S.; Bergmann, Sven; Nelson, Matthew R.; Stephens, Matthew; Bustamante, Carlos D. (2008). "Genes mirror geography within Europe". Nature. 456 (7218): 98–101. Bibcode:2008Natur.456...98N. doi:10.1038/nature07331. PMC 2735096. {{PMID|18758442}}. Lay summary – Gene Expression (31 August 2008).</ref> Similar to ] and unlike the ] and ], Iberia was shielded from settlement from the ] and Caucasus region by its western geographic location, and its low level of ]n admixture probably arrived during the Roman period. Later historical Eastern Mediterranean and ]ern genetic contribution to the Iberia gene-pool was also significant compared to other Western European countries, driven by ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| ] plot of 17 contemporary Iberian populations<ref name="pmid31127131">{{cite journal|vauthors=Pimenta J, Lopes AM, Carracedo A, Arenas M, Amorim A, Comas D| title=Spatially explicit analysis reveals complex human genetic gradients in the Iberian Peninsula. | journal=Sci Rep | year= 2019 | volume= 9 | issue= 1 | pages= 7825 | pmid=31127131 | doi=10.1038/s41598-019-44121-6 | pmc=6534591 | bibcode=2019NatSR...9.7825P }}</ref>]] | |||

| The ancestry of modern Iberians (comprising the ] and ]) is consistent with the geographical situation of the ] in the South-west corner of ], showing characteristics that are largely typical in Southern and Western Europeans. As is the case for most of the rest of Southern Europe, the principal ancestral origin of modern Iberians are ] who arrived during the Neolithic. The large predominance of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R1b, common throughout ], is also testimony to a sizeable input from various waves of (predominantly male) ] that originated in the ] during the ].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Nelis |first1=Mari |last2=Esko |first2=Tõnu |last3=Mägi |first3=Reedik |last4=Zimprich |first4=Fritz |last5=Zimprich |first5=Alexander |last6=Toncheva |first6=Draga |last7=Karachanak |first7=Sena |last8=Piskáčková |first8=Tereza |last9=Balaščák |first9=Ivan |last10=Peltonen |first10=Leena |last11=Jakkula |first11=Eveliina |last12=Rehnström |first12=Karola |last13=Lathrop |first13=Mark |last14=Heath |first14=Simon |last15=Galan |first15=Pilar |last16=Schreiber |first16=Stefan |last17=Meitinger |first17=Thomas |last18=Pfeufer |first18=Arne |last19=Wichmann |first19=H-Erich |last20=Melegh |first20=Béla |last21=Polgár |first21=Noémi |last22=Toniolo |first22=Daniela |last23=Gasparini |first23=Paolo |last24=D'Adamo |first24=Pio |last25=Klovins |first25=Janis |last26=Nikitina-Zake |first26=Liene |last27=Kučinskas |first27=Vaidutis |last28=Kasnauskienė |first28=Jūratė |last29=Lubinski |first29=Jan |last30=Debniak |first30=Tadeusz |last31=Limborska |first31=Svetlana |last32=Khrunin |first32=Andrey |last33=Estivill |first33=Xavier |last34=Rabionet |first34=Raquel |last35=Marsal |first35=Sara |last36=Julià |first36=Antonio |last37=Antonarakis |first37=Stylianos E. |last38=Deutsch |first38=Samuel |last39=Borel |first39=Christelle |last40=Attar |first40=Homa |last41=Gagnebin |first41=Maryline |last42=Macek |first42=Milan |last43=Krawczak |first43=Michael |last44=Remm |first44=Maido |last45=Metspalu |first45=Andres |last46=Fleischer |first46=Robert C. |title=Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East |journal=PLOS ONE |date=8 May 2009 |volume=4 |issue=5 |pages=e5472 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0005472 |pmid=19424496 |pmc=2675054 |bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.5472N |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Novembre |first1=John |last2=Johnson |first2=Toby |last3=Bryc |first3=Katarzyna |last4=Kutalik |first4=Zoltán |last5=Boyko |first5=Adam R. |last6=Auton |first6=Adam |last7=Indap |first7=Amit |last8=King |first8=Karen S. |last9=Bergmann |first9=Sven |last10=Nelson |first10=Matthew R. |last11=Stephens |first11=Matthew |last12=Bustamante |first12=Carlos D. |title=Genes mirror geography within Europe |journal=Nature |date=31 August 2008 |volume=456 |issue=7218 |pages=98–101 |doi=10.1038/nature07331 |pmid=18758442 |pmc=2735096 |bibcode=2008Natur.456...98N }}</ref> | |||

| Like ], and ], ] has a low but specific level of ancestry, originating both in ] and in ], which is largely ascribed to the long ] in the Iberian peninsula and possibly ],<ref>Cruciani, F.; La Fratta, R.; Trombetta, B.; Santolamazza, P.; Sellitto, D.; Colomb, E. B.; Dugoujon, J. -M.; Crivellaro, F.; Benincasa, T. (2007). "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. {{PMID|17351267}}</ref> and the population of the ] shows a bigger African admixture than the average Southern Europe due to its location as an African archipelago.<ref name="pmid23733930"/> Significant genetic differences are found among, and even within, Spain's different regions, which can be explained by the wide divergence in their historical trajectories and Spain's internal geographic boundaries. The Basque region holds the least Eastern Mediterranean ancestry in Iberia. African influence is mainly concentrated in the Southern and Western regions of the peninsula, though the genetic influence is a minor component of the overall mix.<ref>Pereira, Luisa; Cunha, Carla; Alves, Cintia; Amorim, Antonio (2005). "African Female Heritage in Iberia: A Reassessment of mtDNA Lineage Distribution in Present Times". Human Biology. 77 (2): 213–29. doi:10.1353/hub.2005.0041. {{PMID|16201138}}.</ref><ref>Moorjani P, Patterson N, Hirschhorn JN, Keinan A, Hao L, Atzmon G, et al. (2011). "The History of African Gene Flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews". PLoS Genet. 7 (4): e1001373. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1001373. PMC 3080861. {{PMID|21533020}}.</ref><ref>González, Ana M.; Brehm, Antonio; Pérez, José A.; Maca-Meyer, Nicole; Flores, Carlos; Cabrera, Vicente M. (2003). "Mitochondrial DNA affinities at the Atlantic fringe of Europe". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 120 (4): 391–404. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10168. {{PMID|12627534}}.</ref> | |||

| Modern Iberians' genetic inheritance largely derives from the pre-Roman inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula who were deeply ] after the conquest of the region by the ]:<ref name="Bycroft20192">{{cite journal |last1=Bycroft |first1=Clare |last2=Fernandez-Rozadilla |first2=Ceres |last3=Ruiz-Ponte |first3=Clara |last4=Quintela |first4=Inés |last5=Carracedo |first5=Ángel |last6=Donnelly |first6=Peter |last7=Myers |first7=Simon |date=1 February 2019 |title=Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula |journal=Nature Communications |volume=10 |issue=1 |pages=551 |bibcode=2019NatCo..10..551B |doi=10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w |pmc=6358624 |pmid=30710075}}</ref><ref name="pmid30872528">{{cite journal |last1=Olalde |first1=Iñigo |last2=Mallick |first2=Swapan |last3=Patterson |first3=Nick |last4=Rohland |first4=Nadin |last5=Villalba-Mouco |first5=Vanessa |last6=Silva |first6=Marina |last7=Dulias |first7=Katharina |last8=Edwards |first8=Ceiridwen J. |last9=Gandini |first9=Francesca |last10=Pala |first10=Maria |last11=Soares |first11=Pedro |last12=Ferrando-Bernal |first12=Manuel |last13=Adamski |first13=Nicole |last14=Broomandkhoshbacht |first14=Nasreen |last15=Cheronet |first15=Olivia |display-authors=29 |date=15 March 2019 |title=The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years |journal=Science |volume=363 |issue=6432 |pages=1230–1234 |bibcode=2019Sci...363.1230O |doi=10.1126/science.aav4040 |pmc=6436108 |pmid=30872528 |last16=Culleton |first16=Brendan J. |last17=Fernandes |first17=Daniel |last18=Lawson |first18=Ann Marie |last19=Mah |first19=Matthew |last20=Oppenheimer |first20=Jonas |last21=Stewardson |first21=Kristin |last22=Zhang |first22=Zhao |last23=Arenas |first23=Juan Manuel Jiménez |last24=Moyano |first24=Isidro Jorge Toro |last25=Salazar-García |first25=Domingo C. |last26=Castanyer |first26=Pere |last27=Santos |first27=Marta |last28=Tremoleda |first28=Joaquim |last29=Lozano |first29=Marina |last30=Borja |first30=Pablo García |last31=Fernández-Eraso |first31=Javier |last32=Mujika-Alustiza |first32=José Antonio |last33=Barroso |first33=Cecilio |last34=Bermúdez |first34=Francisco J. |last35=Mínguez |first35=Enrique Viguera |last36=Burch |first36=Josep |last37=Coromina |first37=Neus |last38=Vivó |first38=David |last39=Cebrià |first39=Artur |last40=Fullola |first40=Josep Maria |last41=García-Puchol |first41=Oreto |last42=Morales |first42=Juan Ignacio |last43=Oms |first43=F. Xavier |last44=Majó |first44=Tona |last45=Vergès |first45=Josep Maria |last46=Díaz-Carvajal |first46=Antònia |last47=Ollich-Castanyer |first47=Imma |last48=López-Cachero |first48=F. Javier |last49=Silva |first49=Ana Maria |last50=Alonso-Fernández |first50=Carmen |last51=de Castro |first51=Germán Delibes |last52=Echevarría |first52=Javier Jiménez |last53=Moreno-Márquez |first53=Adolfo |last54=Berlanga |first54=Guillermo Pascual |last55=Ramos-García |first55=Pablo |last56=Muñoz |first56=José Ramos |last57=Vila |first57=Eduardo Vijande |last58=Arzo |first58=Gustau Aguilella |last59=Arroyo |first59=Ángel Esparza |last60=Lillios |first60=Katina T. |last61=Mack |first61=Jennifer |last62=Velasco-Vázquez |first62=Javier |last63=Waterman |first63=Anna |last64=de Lugo Enrich |first64=Luis Benítez |last65=Sánchez |first65=María Benito |last66=Agustí |first66=Bibiana |last67=Codina |first67=Ferran |last68=de Prado |first68=Gabriel |last69=Estalrrich |first69=Almudena |last70=Flores |first70=Álvaro Fernández |last71=Finlayson |first71=Clive |last72=Finlayson |first72=Geraldine |last73=Finlayson |first73=Stewart |last74=Giles-Guzmán |first74=Francisco |last75=Rosas |first75=Antonio |last76=González |first76=Virginia Barciela |last77=Atiénzar |first77=Gabriel García |last78=Hernández Pérez |first78=Mauro S. |last79=Llanos |first79=Armando |last80=Marco |first80=Yolanda Carrión |last81=Beneyto |first81=Isabel Collado |last82=López-Serrano |first82=David |last83=Tormo |first83=Mario Sanz |last84=Valera |first84=António C. |last85=Blasco |first85=Concepción |last86=Liesau |first86=Corina |last87=Ríos |first87=Patricia |last88=Daura |first88=Joan |last89=de Pedro Michó |first89=María Jesús |last90=Diez-Castillo |first90=Agustín A. |last91=Fernández |first91=Raúl Flores |last92=Farré |first92=Joan Francès |last93=Garrido-Pena |first93=Rafael |last94=Gonçalves |first94=Victor S. |last95=Guerra-Doce |first95=Elisa |last96=Herrero-Corral |first96=Ana Mercedes |last97=Juan-Cabanilles |first97=Joaquim |last98=López-Reyes |first98=Daniel |last99=McClure |first99=Sarah B. |last100=Pérez |first100=Marta Merino |last101=Foix |first101=Arturo Oliver |last102=Borràs |first102=Montserrat Sanz |last103=Sousa |first103=Ana Catarina |last104=Encinas |first104=Julio Manuel Vidal |last105=Kennett |first105=Douglas J. |last106=Richards |first106=Martin B. |last107=Alt |first107=Kurt Werner |last108=Haak |first108=Wolfgang |last109=Pinhasi |first109=Ron |last110=Lalueza-Fox |first110=Carles |last111=Reich |first111=David}}</ref> | |||

| * ] and ] speaking ] groups: (], ], ], ], ], ]).<ref>{{cite web |title=Iberians - MSN Encarta |url=http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761568486/Iberians.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091030032902/http://encarta.msn.com/encyclopedia_761568486/Iberians.html |archive-date=30 October 2009 |access-date=12 January 2022 |website=Encarta.msn.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Álvarez-Sanchís |first1=Jesús |date=28 February 2005 |title=Oppida and Celtic society in western Spain |url=https://dc.uwm.edu/ekeltoi/vol6/iss1/5/ |journal=E-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies |volume=6 |issue=1}}</ref><ref name="web.archive.org">{{cite web |title=Ethnographic Map of Pre-Roman Iberia (Circa 200 B.C.) |url=http://www.arqueotavira.com/Mapas/Iberia/Populi.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040611215344/http://www.arqueotavira.com/Mapas/Iberia/Populi.htm |archive-date=11 June 2004 |access-date=12 January 2022 |website=Arqueotavira.com}}</ref> | |||

| * ] (], ], ] and ]).<ref>{{Cite web |title=Spain - History |url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Spain/History |website=Britannica.com}}</ref><ref name="web.archive.org" /> | |||

| There are also some genetic influences from the ] and ] tribes who arrived after the Roman period, including the ], ] ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.openedition.org/cvz/2148?lang=en |title=L'Europe héritière de l'Espagne wisigothique |date=23 January 2014 |publisher=Books.openedition.org |isbn=9788490960981 |series=Collection de la Casa de Velázquez |pages=326–339 |chapter=Les Wisigoths dans le Portugal médiéval : état actuel de la question}}</ref><ref>https://alpha.sib.uc.pt/?q=content/o-património-visigodo-da-l%C3%ADngua-portuguesa {{dead link|date=March 2022}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Quiroga |first1=Jorge López |date=January 2017 |title=(PDF) IN TEMPORE SUEBORUM. The time of the Suevi in Gallaecia (411–585 AD). |url=https://www.academia.edu/37321555 |journal=Jorge López Quiroga-Artemio M. Martínez Tejera (Coord.): In Tempore Sueborum. The Time of the Sueves in Gallaecia (411–585 Ad). The First Medieval Kingdom of the West, Ourense |publisher=Academia.edu |access-date=21 January 2020}}</ref> Due to its position on the ], like other ] countries, there were also contacts with other Mediterranean peoples such as the ]ns, ] and ] who briefly settled along Iberia's eastern and southern coasts, the ] community, and ] and ] arrived during ], all of them leaving some ] and ] genetic influences, particularly in the south and west of the ].<ref>{{cite web |author=James S. Amelang |title=The Expulsion of the Moriscos: Still more Questions than Answers |url=https://intransitduke.org/files/2019/08/02B_01_whitepaper_Amelang.pdf |access-date=22 January 2022 |website=Intransitduke.org |location=Universidad Autónoma, Madrid}}</ref>{{sfn|Jónsson|2007|p=195}}<ref name="pmid30872528" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Adams |first1=Susan M. |last2=Bosch |first2=Elena |last3=Balaresque |first3=Patricia L. |last4=Ballereau |first4=Stéphane J. |last5=Lee |first5=Andrew C. |last6=Arroyo |first6=Eduardo |last7=López-Parra |first7=Ana M. |last8=Aler |first8=Mercedes |last9=Grifo |first9=Marina S. Gisbert |last10=Brion |first10=Maria |last11=Carracedo |first11=Angel |last12=Lavinha |first12=João |last13=Martínez-Jarreta |first13=Begoña |last14=Quintana-Murci |first14=Lluis |last15=Picornell |first15=Antònia |date=12 December 2008 |title=The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula |journal=American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=83 |issue=6 |pages=725–736 |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007 |pmc=2668061 |pmid=19061982 |last16=Ramon |first16=Misericordia |last17=Skorecki |first17=Karl |last18=Behar |first18=Doron M. |last19=Calafell |first19=Francesc |last20=Jobling |first20=Mark A.}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Torres |first1=Gabriela |date=31 December 2008 |title=El español "puro" tiene de todo |work=BBC Mundo |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/hi/spanish/science/newsid_7804000/7804668.stm}}</ref><ref>Cervantes virtual: . {{cite journal |last1=Adams |first1=Susan M. |last2=Bosch |first2=Elena |last3=Balaresque |first3=Patricia L. |last4=Ballereau |first4=Stéphane J. |last5=Lee |first5=Andrew C. |last6=Arroyo |first6=Eduardo |last7=López-Parra |first7=Ana M. |last8=Aler |first8=Mercedes |last9=Grifo |first9=Marina S. Gisbert |last10=Brion |first10=Maria |last11=Carracedo |first11=Angel |last12=Lavinha |first12=João |last13=Martínez-Jarreta |first13=Begoña |last14=Quintana-Murci |first14=Lluis |last15=Picornell |first15=Antònia |name-list-style=vanc |date=December 2008 |title=The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula |journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=83 |issue=6 |pages=725–736 |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007 |pmc=2668061 |pmid=19061982 |last16=Ramon |first16=Misericordia |last17=Skorecki |first17=Karl |last18=Behar |first18=Doron M. |last19=Calafell |first19=Francesc |last20=Jobling |first20=Mark A.}}</ref><ref name="Bycroft20192" /> Similar to ], Iberia was slightly less impacted from the Hellenistic Eastern Mediterranean migrations by its western and southern geographic location, and thus has both lower levels of ] and higher ones of African admixture than ] and ], most of which probably arrived to Iberia during historic rather than prehistoric times, especially in the ].<ref name="Bycroft2019">{{cite journal |last=Bycroft |first=Clare |display-authors=etal |year=2019 |title=Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula |journal=Nature Communications |volume=10 |issue=1 |page=551 |bibcode=2019NatCo..10..551B |doi=10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w |pmc=6358624 |pmid=30710075}}</ref><ref name="Olalde2019">{{cite journal |last=Olalde |first=Iñigo |display-authors=etal |year=2019 |title=The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years |journal=Science |volume=363 |issue=6432 |pages=1230–1234 |bibcode=2019Sci...363.1230O |doi=10.1126/science.aav4040 |pmc=6436108 |pmid=30872528}}</ref> Nevertheless over half of both Iberian and Sardinian Iron Age genetic profiles were replaced during the centuries long Punic, Roman Imperial and Islamic dominations, with only the Basques remaining largely uneffected.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Marcus |first=Joseph H. |last2=Posth |first2=Cosimo |last3=Ringbauer |first3=Harald |last4=Lai |first4=Luca |last5=Skeates |first5=Robin |last6=Sidore |first6=Carlo |last7=Beckett |first7=Jessica |last8=Furtwängler |first8=Anja |last9=Olivieri |first9=Anna |last10=Chiang |first10=Charleston W. K. |last11=Al-Asadi |first11=Hussein |last12=Dey |first12=Kushal |last13=Joseph |first13=Tyler A. |last14=Liu |first14=Chi-Chun |last15=Sarkissian |first15=Clio Der |date=2020 |title=Genetic history from the Middle Neolithic to present on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7039977 |journal=Nature Communications |language=en |volume=11 |doi=10.1038/s41467-020-14523-6 |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20240603073611/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7039977/ |archive-date=2024-06-03|hdl=21.11116/0000-0005-BF51-9 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Fernandes |first=Daniel M. |last2=Mittnik |first2=Alissa |last3=Olalde |first3=Iñigo |last4=Lazaridis |first4=Iosif |last5=Cheronet |first5=Olivia |last6=Rohland |first6=Nadin |last7=Mallick |first7=Swapan |last8=Bernardos |first8=Rebecca |last9=Broomandkhoshbacht |first9=Nasreen |last10=Carlsson |first10=Jens |last11=Culleton |first11=Brendan J. |last12=Ferry |first12=Matthew |last13=Gamarra |first13=Beatriz |last14=Lari |first14=Martina |last15=Mah |first15=Matthew |date=24 August 2020 |title=The Spread of Steppe and Iranian Related Ancestry in the Islands of the Western Mediterranean |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7080320 |journal=Nature ecology & evolution |language=en |volume=4 |issue=3 |doi=10.1038/s41559-020-1102-0 |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20240901112926/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7080320/ |archive-date=2024-09-01|hdl=10447/400668 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=Flores-Bello |first=André |last2=Bauduer |first2=Frédéric |last3=Salaberria |first3=Jasone |last4=Oyharçabal |first4=Bernard |last5=Calafell |first5=Francesc |last6=Bertranpetit |first6=Jaume |last7=Quintana-Murci |first7=Lluis |last8=Comas |first8=David |date=24 May 2021 |title=Genetic origins, singularity, and heterogeneity of Basques |url=https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)00349-3?_returnURL=https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0960982221003493?showall=true |journal=Current Biology |language=English |volume=31 |issue=10 |pages=2167–2177.e4 |doi=10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.010 |issn=0960-9822 |archive-url=http://web.archive.org/web/20241201211011/https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(21)00349-3?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0960982221003493%3Fshowall%3Dtrue |archive-date=2024-12-01|hdl=10230/52292 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| == Population Genetics: Methods and Limitations == | == Population Genetics: Methods and Limitations == | ||

| The foremost pioneer of the study of population genetics was ]. Cavalli-Sforza used ''classical genetic markers'' to analyse DNA by proxy. This method studies differences in the frequencies of particular allelic traits, namely ] from proteins found within ] (such as the ], Rhesus blood antigens, ], ], G-6-P-D isoenzymes, among others). Subsequently, his team calculated ]s between populations, based on the principle that two populations that share similar frequencies of a trait are more closely related than populations that have more divergent frequencies of the trait.<ref name="Cavalli-Sforza 1993 51">{{cite book |vauthors=Cavalli-Sforza LL, Menozzi P, Piazza A |author-link1=Luigi Cavalli-Sforza |title=The History and Geography of Human Genes |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=1993 |isbn=978-0-691-08750-4 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FrwNcwKaUKoC |access-date=2009-07-22 |page=51}}</ref> | |||

| Since then, population genetics has progressed significantly and studies using ''direct DNA analysis'' are now abundant and may use mitochondrial DNA ('''mtDNA'''), the non-recombining portion of the Y chromosome ('''NRY''') or autosomal DNA. MtDNA and NRY DNA share some similar features which have made them particularly useful in genetic anthropology. These properties include the direct, unaltered inheritance of mtDNA and NRY DNA from mother to offspring and father to son, respectively, without the 'scrambling' effects of ]. We also presume that these genetic loci are not affected by natural selection and that the major process responsible for changes in ]s has been mutation (which can be calculated).<ref>{{ |

Since then, population genetics has progressed significantly and studies using ''direct DNA analysis'' are now abundant and may use mitochondrial DNA ('''mtDNA'''), the non-recombining portion of the Y chromosome ('''NRY''') or autosomal DNA. MtDNA and NRY DNA share some similar features which have made them particularly useful in genetic anthropology. These properties include the direct, unaltered inheritance of mtDNA and NRY DNA from mother to offspring and father to son, respectively, without the 'scrambling' effects of ]. We also presume that these genetic loci are not affected by natural selection and that the major process responsible for changes in ]s has been mutation (which can be calculated).<ref>{{cite book |vauthors=Milisauskas S |title=European Prehistory: a survey |year=2002 |publisher=Birkhauser |isbn=978-0-306-46793-6 |page=58}}</ref> | ||

| Whereas ] and mtDNA haplogroups represent but a small component of a |

Whereas ] and mtDNA haplogroups represent but a small component of a person's DNA pool, autosomal DNA has the advantage of containing hundreds and thousands of examinable genetic loci, thus giving a more complete picture of genetic composition. Descent relationships can only to be determined on a statistical basis, because autosomal DNA undergoes recombination. A single chromosome can record a history for each gene. Autosomal studies are much more reliable for showing the relationships between existing populations but do not offer the possibilities for unraveling their histories in the same way as mtDNA and NRY DNA studies promise, despite their many complications.{{citation needed|date=December 2016}} | ||

| == Analyses of nuclear and ancient DNA == | |||

| == Main genetic compositions == | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| DNA analysis shows that Spanish and Portuguese populations are most closely related to other populations of western Europe.<ref>{{cite journal |

] shows that Spanish and Portuguese populations are most closely related to other populations of western Europe.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Nelis|first1=Mari|last2=Esko|first2=Tõnu|last3=Mägi|first3=Reedik|last4=Zimprich|first4=Fritz|last5=Zimprich|first5=Alexander|last6=Toncheva|first6=Draga|last7=Karachanak|first7=Sena|last8=Piskácková|first8=Tereza|last9=Balascák|first9=Ivan|last10=Peltonen|first10=L|last11=Jakkula|first11=E|year=2009|editor1-last=Fleischer|editor1-first=Robert C.|title=Genetic Structure of Europeans: A View from the North–East|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=4|issue=5|pages=e5472|bibcode=2009PLoSO...4.5472N|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0005472|pmc=2675054|pmid=19424496|first21=N|first22=D|last23=Gasparini|first23=P|last24=d'Adamo|first24=P|last25=Klovins|first25=J|first26=L|last26=Nikitina-Zake|last27=Kucinskas|first27=V|last28=Kasnauskiene|first28=J|last29=Lubinski|first29=J|last30=Debniak|last22=Toniolo|last13=Lathrop|last21=Polgár|last16=Schreiber|last12=Rehnström|first12=K|first13=M|last14=Heath|first14=S|last15=Galan|first15=P|first16=S|first20=B|last17=Meitinger|first17=T|last18=Pfeufer|first18=A|last19=Wichmann|first19=HE|last20=Melegh|first30=T|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="nytimes.com">{{cite news|last=Wade|first=Nicholas|date=13 August 2008|title=The Genetic Map of Europe|work=]|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/13/science/13visual.html|access-date=17 October 2009}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Novembre|first1=John|last2=Johnson|first2=Toby|last3=Bryc|first3=Katarzyna|last4=Kutalik|first4=Zoltán|last5=Boyko|first5=Adam R.|last6=Auton|first6=Adam|last7=Indap|first7=Amit|last8=King|first8=Karen S.|last9=Bergmann|first9=Sven|last10=Nelson|first10=Matthew R.|last11=Stephens|first11=Matthew|year=2008|title=Genes mirror geography within Europe|journal=Nature|volume=456|issue=7218|pages=98–101|bibcode=2008Natur.456...98N|doi=10.1038/nature07331|pmc=2735096|pmid=18758442 |last12=Bustamante|first12=Carlos D.}} | ||

| *{{cite web |date=31 August 2008 |title=Genetic map of Europe again |website=Gene Expression |url=http://www.gnxp.com/blog/2008/08/genetic-map-of-europe-again.php}}</ref> | |||

| There is an axis of significant genetic differentiation along the east-west direction, in contrast to remarkable genetic similarity in the north-south direction. North African admixture, associated with the ], can be dated to the period between c. AD 860–1120.<ref>Bycroft, C., et al., "Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula", bioRxiv 250191 (March 2018), {{DOI|10.1101/250191}}.</ref> | |||

| There is an axis of significant genetic differentiation along the east–west direction, in contrast to remarkable genetic similarity in the north–south direction. North African admixture, associated with the ], can be dated to the period between c. AD 860–1120.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bycroft|first1=Clare|last2=Fernandez-Rozadilla|first2=Ceres|last3=Ruiz-Ponte|first3=Clara|last4=Quintela|first4=Inés|last5=Carracedo|first5=Ángel|last6=Donnelly|first6=Peter|last7=Myers|first7=Simon|date=1 February 2019|title=Patterns of genetic differentiation and the footprints of historical migrations in the Iberian Peninsula|journal=Nature Communications|volume=10|issue=1|pages=551|bibcode=2019NatCo..10..551B|doi=10.1038/s41467-018-08272-w|pmc=6358624|pmid=30710075}}</ref> | |||

| A study published in 2019 using samples of 271 Iberians spanning prehistoric and historic times proposes the following inflexion points in Iberian genomic history:<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Olalde|first1=Iñigo|last2=Mallick|first2=Swapan|last3=Patterson|first3=Nick|last4=Rohland|first4=Nadin|last5=Villalba-Mouco|first5=Vanessa|last6=Silva|first6=Marina|last7=Dulias|first7=Katharina|last8=Edwards|first8=Ceiridwen J.|last9=Gandini|first9=Francesca|last10=Pala|first10=Maria|last11=Soares|first11=Pedro|date=2019-03-15|title=The genomic history of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 years|journal=Science|volume=363|issue=6432|pages=1230–1234|doi=10.1126/science.aav4040|issn=0036-8075|pmc=6436108|pmid=30872528|bibcode=2019Sci...363.1230O}}</ref> | |||

| # ]: ]s from the European Steppes of Western Russia, Georgia and Ukraine are the first humans to settle the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula. | |||

| # ]: ]s settle the entire Iberian Peninsula from ]. | |||

| # ]: Inflow of Central European hunter-gatherers and some gene inflow from sporadic contact with ]. | |||

| # ]: Steppe inflow from Central Europe. | |||

| # ]: Additional Steppe gene flow from Central Europe, - the genetic pool of the ] remains mostly intact from this point on. | |||

| # ]: genetic inflow from Central and Eastern ]. Some additional inflow of North African genes detected in Southern Iberia. | |||

| # ]: no detectable inflows. | |||

| # ]: Inflow from Northern Africa. Following the ], there is further genetic convergence between North and South Iberia. | |||

| ===North African influence=== | |||

| {{main|African admixture in Europe}} | |||

| ] | |||

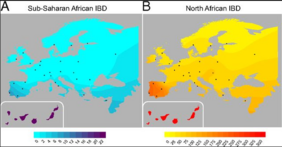

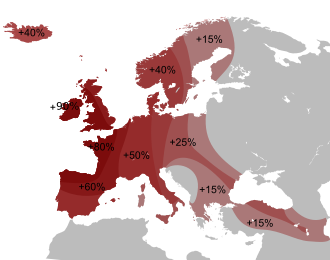

| A number of studies have focused on ascertaining the genetic impact of historical North African population movements into Iberia on the genetic composition of modern Spanish and Portuguese populations. Initial studies pointed to the ] acting more as a genetic barrier than a bridge during prehistorical times,<ref name="pmid15044595">{{cite journal |doi=10.1093/molbev/msh135 |title=Estimating the Impact of Prehistoric Admixture on the Genome of Europeans |year=2004 |last1=Dupanloup |first1=I. |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |volume=21 |issue=7 |pages=1361–72 |pmid=15044595 |last2=Bertorelle |first2=G |last3=Chikhi |first3=L |last4=Barbujani |first4=G|s2cid=17665038 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="pmid11254456">{{cite journal |doi=10.1086/319521 |title=High-Resolution Analysis of Human Y-Chromosome Variation Shows a Sharp Discontinuity and Limited Gene Flow between Northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula |year=2001 |last1=Bosch |first1=Elena |last2=Calafell |first2=Francesc |last3=Comas |first3=David |last4=Oefner |first4=Peter J. |last5=Underhill |first5=Peter A. |last6=Bertranpetit |first6=Jaume |journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=68 |issue=4 |pages=1019–29 |pmid=11254456 |pmc=1275654}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/s004390000370 |title=Alu insertion polymorphisms in NW Africa and the Iberian Peninsula: Evidence for a strong genetic boundary through the Gibraltar Straits |year=2000 |last1=Comas |first1=David |last2=Calafell |first2=Francesc |last3=Benchemsi |first3=kiNoufissa |last4=Helal |first4=Ahmed |last5=Lefranc |first5=Gerard |last6=Stoneking |first6=Mark |last7=Batzer |first7=Mark A. |last8=Bertranpetit |first8=Jaume |last9=Sajantila |first9=Antti |journal=Human Genetics |volume=107 |issue=4 |pages=312–9 |pmid=11129330 |s2cid=9618737 }}</ref> while other studies point to a higher level of recent North African admixture among Iberians than among other European populations,<ref name="Moorjani+2011">{{cite journal | last1 = Moorjani| first1 = Priya| last2 = Patterson| first2 = Nick| last3 = Hirschhorn| first3 = Joel N.| last4 = Keinan| first4 = Alon| last5 = Hao| first5 = Li| last6 = Atzmon| first6 = Gil| last7 = Burns| first7 = Edward| last8 = Ostrer| first8 = Harry| last9 = Price| first9 = Alkes L.| last10 = Reich| first10 = David | year = 2011 | title = The History of African Gene Flow into Southern Europeans, Levantines, and Jews | journal = PLOS Genet | volume = 7 | issue = 4| page = e1001373 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001373 | pmid=21533020 | pmc=3080861 |name-list-style=vanc| display-authors=6| doi-access = free}}</ref><ref name="pmid19156170">{{cite journal |doi=10.1038/ejhg.2008.258 |title=Moors and Saracens in Europe: estimating the medieval North African male legacy in southern Europe |year=2009 |last1=Capelli |first1=Cristian |first2=Valerio |first3=Francesca |first4=Ilaria |first5=Francesca |pmc=2947089 |first6=Mara |first7=Gianmarco |first8=Sergio |first9=Adriano |journal=European Journal of Human Genetics |volume=17 |pmid=19156170 |issue=6 |last2=Onofri |last3=Brisighelli |last4=Boschi |last5=Scarnicci |last6=Masullo |last7=Ferri |last8=Tofanelli |last9=Tagliabracci |last10=Gusmao |first10=Leonor |last11=Amorim |first11=Antonio |last12=Gatto |first12=Francesco |last13=Kirin |first13=Mirna |last14=Merlitti |first14=Davide |last15=Brion |first15=Maria |last16=Verea |first16=Alejandro Blanco |last17=Romano |first17=Valentino |last18=Cali |first18=Francesco |last19=Pascali |first19=Vincenzo |pages=848–52}}</ref><ref name="ReferenceC">{{cite journal |doi=10.1086/386295 |title=Origin, Diffusion, and Differentiation of Y-Chromosome Haplogroups E and J: Inferences on the Neolithization of Europe and Later Migratory Events in the Mediterranean Area |year=2004 |last1=Semino |first1=Ornella |last2=Magri |first2=Chiara |last3=Benuzzi |first3=Giorgia |last4=Lin |first4=Alice A. |last5=Al-Zahery |first5=Nadia |last6=Battaglia |first6=Vincenza |last7=MacCioni |first7=Liliana |last8=Triantaphyllidis |first8=Costas |last9=Shen |first9=Peidong |last10=Oefner |first10=Peter J. |last11=Zhivotovsky |first11=Lev A. |last12=King |first12=Roy |last13=Torroni |first13=Antonio |last14=Cavalli-Sforza |first14=L. Luca |last15=Underhill |first15=Peter A. |last16=Santachiara-Benerecetti |first16=A. Silvana |journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=74 |issue=5 |pages=1023–34 |pmid=15069642 |pmc=1181965}}</ref><ref name="pmid17216803">{{cite journal |doi=10.1353/hub.2006.0045 |title=North African Berber and Arab Influences in the Western Mediterranean Revealed by Y-Chromosome DNA Haplotypes |year=2006 |last1=Gérard |first1=Nathalie |last2=Berriche |first2=Sala |last3=Aouizérate |first3=Annie |last4=Diéterlen |first4=Florent |last5=Lucotte |first5=Gérard |journal=Human Biology |volume=78 |issue=3 |pages=307–16 |pmid=17216803|s2cid=13347549 }}</ref><ref name="pmid19061982" /><ref name="gonzalez2003" /><ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal |doi=10.1007/s00439-004-1168-9 |title=Y chromosomal haplogroup J as a signature of the post-neolithic colonization of Europe |year=2004 |last1=Giacomo |first1=F. |first2=F. |first3=L. O. |first4=N. |first5=N. |first6=J. |first7=R. |first8=G. |first9=F. |last10=Ciavarella |first10=G. |last11=Cucci |first11=F. |last12=Stasi |first12=L. |last13=Gavrila |first13=L. |last14=Kerimova |first14=M. G. |last15=Kovatchev |first15=D. |last16=Kozlov |first16=A. I. |last17=Loutradis |first17=A. |last18=Mandarino |first18=V. |last19=Mammi′ |first19=C. |last20=Michalodimitrakis |first20=E. N. |last21=Paoli |first21=G. |last22=Pappa |first22=K. I. |last23=Pedicini |first23=G. |last24=Terrenato |first24=L. |last25=Tofanelli |first25=S. |last26=Malaspina |first26=P. |last27=Novelletto |first27=A. |journal=Human Genetics |volume=115 |pmid=15322918 |issue=5 |last2=Luca |last3=Popa |last4=Akar |last5=Anagnou |last6=Banyko |last7=Brdicka |last8=Barbujani |last9=Papola |pages=357–371 |s2cid=18482536 |display-authors=8 }}</ref> albeit this is as a result of more recent migratory movements, particularly the Moorish invasion of Iberia in the 8th century. | |||

| ] | |||

| In terms of autosomal DNA, the most recent study regarding African admixture in Iberian populations was conducted in April 2013 by Botigué et al. using genome-wide SNP data for over 2000 European, Maghreb, Qatar and Sub-Saharan individuals of which 119 were Spaniards and 117 Portuguese, concluding that Spain and Portugal hold significant levels of North African ancestry. Estimates of shared ancestry averaged from 4% in some places to 12% in the general population; the populations of the ] yielded from 0% to 96% of shared ancestry with north Africans, although the Canary islands are a Spanish exclave located in the African continent, and thus this output is not representative of the Iberian population; these same results did not exceed 2% in other western or southern European populations. Sub-Saharan African ancestry was detected at less than 1% in Europe, with the exception of the Canary Islands.<ref name="pmid23733930">{{Cite journal |pmc=3718088|year=2013|last1=Botigué|first1=L. R.|title=Gene flow from North Africa contributes to differential human genetic diversity in southern Europe|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=110|issue=29|pages=11791–11796|last2=Henn|first2=B. M.|last3=Gravel|first3=S|last4=Maples|first4=B. K.|last5=Gignoux|first5=C. R.|last6=Corona|first6=E|last7=Atzmon|first7=G|last8=Burns|first8=E|last9=Ostrer|first9=H|last10=Flores|first10=C|last11=Bertranpetit|first11=J|last12=Comas|first12=D|last13=Bustamante|first13=C. D.|doi=10.1073/pnas.1306223110|bibcode=2013PNAS..11011791B|pmid=23733930|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref> {{webarchive|url=https://archive.today/20150430230334/http://biologiaevolutiva.org/dcomas/estimating-gene-flow-from-north-africa-to-southern-europe/ |date=2015-04-30 }}, David Comas, one of the authors of the study</ref><ref>"La cifra del 20% sólo se da en Canarias, para el resto del país oscila entre el 10% y 12%", explica Comas.", David Comas, one of the authors of the study, , Huffington post, June 2013</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Flores|first1=Carlos|last2=Villar|first2=Jesús|last3=Guerra|first3=Luisa|last4=Hernández|first4=Alexis|last5=Basaldúa|first5=Santiago|last6=Corrales|first6=Almudena|last7=Pino-Yanes|first7=María|date=2011-03-30|title=North African Influences and Potential Bias in Case-Control Association Studies in the Spanish Population|journal=PLOS ONE|language=en|volume=6|issue=3|pages=e18389|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0018389|pmid=21479138|issn=1932-6203|pmc=3068190|bibcode=2011PLoSO...618389P|doi-access=free}}</ref> However, contrary to past autosomal studies and to what is inferred from Y-Chromosome and Mitochondrial Haplotype frequencies (see below), it does not detect significant levels of Sub-Saharan ancestry in any European population outside the Canary Islands. Indeed, a prior 2011 autosomal study by Moorjani et al. found Sub-Saharan ancestry in many parts of southern Europe at ranges of between 1-3%, ''"the highest proportion of African ancestry in Europe is in Iberia (Portugal 4.2±0.3% and Spain 1.4±0.3%), consistent with inferences based on mitochondrial DNA and Y chromosomes and the observation by Auton et al. that within Europe, the Southwestern Europeans have the highest haplotype-sharing with North Africans."''<ref name="Moorjani+2011" /><ref name="pmid19061982">{{cite journal |doi=10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.11.007 |title=The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula |year=2008 |last1=Adams |first1=Susan M. |first2=Elena |first3=Patricia L. |first4=Stéphane J. |first5=Andrew C. |first6=Eduardo |first7=Ana M. |first8=Mercedes |first9=Marina S. Gisbert |journal=The American Journal of Human Genetics |volume=83 |pmid=19061982 |last2=Bosch |last3=Balaresque |last4=Ballereau |last5=Lee |last6=Arroyo |last7=López-Parra |last8=Aler |last9=Grifo |issue=6 |pmc=2668061 |last10=Brion |first10=Maria |last11=Carracedo |first11=Angel |last12=Lavinha |first12=João |last13=Martínez-Jarreta |first13=Begoña |last14=Quintana-Murci |first14=Lluis |last15=Picornell |first15=Antònia |last16=Ramon |first16=Misericordia |last17=Skorecki |first17=Karl |last18=Behar |first18=Doron M. |last19=Calafell |first19=Francesc |last20=Jobling |first20=Mark A. |pages=725–36}} | |||

| *{{cite magazine |author=Tina Hesman Saey |date=3 January 2009 |title=Spanish Inquisition Couldn'T Quash Moorish, Jewish Genes |magazine=] |volume=175 |issue=1 |url=http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/39056/title/Spanish_Inquisition_couldn%E2%80%99t_quash_Moorish,_Jewish_genes |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090221052119/http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/39056/title/Spanish_Inquisition_couldn%E2%80%99t_quash_Moorish,_Jewish_genes |archive-date=2009-02-21}}</ref><ref name="gonzalez2003">{{cite journal |last1=González |first1=Ana M. |last2=Brehm |first2=Antonio |last3=Pérez |first3=José A. |last4=Maca-Meyer |first4=Nicole |last5=Flores |first5=Carlos |last6=Cabrera |first6=Vicente M. |s2cid=6430969 |title=Mitochondrial DNA affinities at the Atlantic fringe of Europe |journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology |date=April 2003 |volume=120 |issue=4 |pages=391–404 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.10168 |pmid=12627534 }}</ref> | |||

| Recent studies show minor relationships between some Iberian regions and ] populations as a result of the ] historical period which in Portugal lasted between the 8th and 12th centuries AD, and in southern Spain continued until the late 15th century AD. Iberia is the European region that has a more prominent presence of ] (E-M81),<ref>{{Cite journal |title=North African Berber and Arab Influences in the Western Mediterranean Revealed by Y-Chromosome DNA Haplotypes |year=2006 |doi=10.1353/hub.2006.0045 |url=https://doi.org/10.1353%2Fhub.2006.0045 |last1=Gérard |first1=Nathalie |last2=Berriche |first2=Sala |last3=Aouizérate |first3=Annie |last4=Diéterlen |first4=Florent |last5=Lucotte |first5=Gérard |journal=Human Biology |volume=78 |issue=3 |pages=307–316 |pmid=17216803 |s2cid=13347549 }}</ref> of haplogroup U (U6) and Haplotype Va, and this may be the result of some original common western Mediterranean population. In Portugal, North African Y-chromosome haplogroups (especially those typically North-West African) are at a frequency of 7.1%.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=Y-chromosome Lineages from Portugal, Madeira and Açores Record Elements of Sephardim and Berber Ancestry |year=2005 |doi=10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00161.x |last1=Gonçalves |first1=Rita |last2=Freitas |first2=Ana |last3=Branco |first3=Marta |last4=Rosa |first4=Alexandra |last5=Fernandes |first5=Ana T. |last6=Zhivotovsky |first6=Lev A. |last7=Underhill |first7=Peter A. |last8=Kivisild |first8=Toomas |last9=Brehm |first9=António |journal=Annals of Human Genetics |volume=69 |issue=4 |pages=443–454 |pmid=15996172 |hdl=10400.13/3018 |s2cid=3229760 |hdl-access=free }}</ref> Some studies of mitochondrial DNA also find evidence of the North African haplogroup U6, especially in northern Portugal.<ref name="Pereira L, Cunha C, Alves C, Amorim A 2005 213–29">{{cite journal|author=Pereira L, Cunha C, Alves C, Amorim A|date=April 2005|doi=10.1353/hub.2005.0041|issue=2|pages=213–29|pmid=16201138|title=African female heritage in Iberia: a reassessment of mtDNA lineage distribution in present times|volume=77|journal=Human Biology|hdl=10216/109268 |s2cid=20901589 |hdl-access=free}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> Although the frequency of U6 is low (4–6%), it was estimated that approximately 27% of the population of northern Portugal had some North African ancestry, as U6 is also not a common lineage in North Africa.<ref name="González AM, Brehm A, Pérez JA, Maca-Meyer N, Flores C, Cabrera VM 2003 391–404">{{cite news|author=González AM, Brehm A, Pérez JA, Maca-Meyer N, Flores C, Cabrera VM|date=April 2003|doi=10.1002/ajpa.10168|issue=4|pages=391–404|pmid=12627534|title=Mitochondrial DNA affinities at the Atlantic fringe of Europe|volume=120|work=American Journal of Physical Anthropology}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> | |||

| According to some studies, the North African and Arab elements in the ancestry of today's Iberians are more than trivial when compared to the basis of pre-Islamic ancestry, and the Strait of Gibraltar seems to function more as a genetic bridge than a barrier.<ref name="pmid150445952">{{cite news|author=Dupanloup I, Bertorelle G, Chikhi L, Barbujani G|date=July 2004|doi=10.1093/molbev/msh135|issue=7|pages=1361–72|pmid=15044595|title=Estimating the impact of prehistoric admixture on the genome of Europeans|volume=21|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator --></ref><ref>{{cite news|author=Bosch E, Calafell F, Comas D, Oefner PJ, Underhill PA, Bertranpetit J|date=April 2001|doi=10.1086/319521|issue=4|pages=1019–29|pmc=1275654|pmid=11254456|title=High-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome variation shows a sharp discontinuity and limited gene flow between northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula|volume=68|work=American Journal of Human Genetics}}<!-- auto-translated by Module:CS1 translator --></ref><ref>{{Cite journal |title=Alu insertion polymorphisms in NW Africa and the Iberian Peninsula: evidence for a strong genetic boundary through the Gibraltar Straits |year=2000 |doi=10.1007/s004390000370 |url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s004390000370 |last1=Comas |first1=David |last2=Calafell |first2=Francesc |last3=Benchemsi |first3=Noufissa |last4=Helal |first4=Ahmed |last5=Lefranc |first5=Gerard |last6=Stoneking |first6=Mark |last7=Batzer |first7=Mark A. |last8=Bertranpetit |first8=Jaume |last9=Sajantila |first9=Antti |journal=Human Genetics |volume=107 |issue=4 |pages=312–319 |pmid=11129330 |s2cid=9618737 }}</ref> | |||

| However, a study that has used different genetic markers has reached different conclusions. In an autosomal study by Spínola et al. (2005), which analyzed the ] (HLA genes) (inherent in all ancestors in direct paternal and maternal lineages) in hundreds of individuals from Portugal, showed that the Portuguese population has been influenced by other ] and North Africans, via many ancient migrations. According to the authors, the North and the South of Portugal show a greater similarity towards North Africans as opposed to the people of the center of the country, who seem closer to other Europeans, since the North of Portugal seems to have concentrated, certainly due to the pressure of Arab expansion, an ancient genetic pole originating from many North Africans and other Europeans, influences through millennia, {{What|date=July 2023}} while southern Portugal shows a North African genetic influence, probably the result of origins recent from the ] people who accompanied the Arab expansion.<ref>{{Cite journal |title=HLA genes in Portugal inferred from sequence-based typing: in the crossroad between Europe and Africa |year=2005 |pmid=15982254 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15982254/ |last1=Spínola |first1=H. |last2=Middleton |first2=D. |last3=Brehm |first3=A. |journal=Tissue Antigens |volume=66 |issue=1 |pages=26–36 |doi=10.1111/j.1399-0039.2005.00430.x }}</ref> | |||

| ] (literally "Moorish"), a small southern town near the Spanish border, known for its Moorish heritage]] | |||

| According to a study published in the ] in December 2008, 30% of modern Portuguese (23.6% in the north and 36.3% in the south) have ] that shows they have male Sephardic Jewish ancestry and 14% (11.8 in the North and 16.1% in the South) have Moorish ancestry.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Genetic Legacy of Religious Diversity and Intolerance: Paternal Lineages of Christians, Jews, and Muslims in the Iberian Peninsula |url=https://www.cell.com/ajhg/fulltext/S0002-9297(08)00592-2}}</ref> Despite the possible alternative sources for lineages attributed to a Sephardic Jewish origin, these proportions were testimony to the importance of ] (voluntary or forced), shown by historical episodes of social and ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| In terms of paternal Y-Chromosome DNA, recent studies coincide in that Iberia has the greatest presence of the typically ]n Y-chromosome haplotype marker E-M81 in Europe, with an average of 3%.<ref name="pmid19156170" /><ref name="ReferenceC" /> as well as Haplotype Va.<ref>{{Cite journal | url=http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/humbiol/vol73/iss5/11/ | title=North African Genes in Iberia Studied by Y-Chromosome DNA Haplotype 5| journal=Human Biology| volume=73| issue=5| date=2011-04-05| last1=Lucotte| first1=Gérard| last2=Gérard| first2=Nathalie| last3=Mercier| first3=Géraldine}}</ref><ref name="pmid17216803" /> Estimates of Y-Chromosome ancestry vary, with a 2008 study published in the ] using 1140 samples from throughout the Iberian peninsula, giving a proportion of 10.6% North African ancestry<ref name="pmid19061982" /><ref name="gonzalez2003" /><ref name="ReferenceA" /> to the paternal composite of Iberians. A similar 2009 study of Y-chromosome with 659 samples from Southern Portugal, 680 from Northern Spain, 37 samples from Andalusia, 915 samples from mainland Italy, and 93 samples from Sicily found significantly higher levels of North African male ancestry in Portugal, Spain and Sicily (7.1%, 7.7% and 7.5% respectively) than in peninsular Italy (1.7%).<ref name="pmid19156170" /> | |||

| Other studies of the Iberian gene-pool have estimated significantly lower levels of North African Ancestry. According to Bosch et al. 2000 "NW African populations may have contributed 7% of Iberian Y chromosomes".<ref name="pmid11254456" /> A wide-ranging study by Cruciani et al. 2007, using 6,501 unrelated Y-chromosome samples from 81 populations found that: "Considering both these E-M78 sub-haplogroups (E-V12, E-V22, E-V65) and the E-M81 haplogroup, the contribution of northern African lineages to the entire male gene pool of ] (barring Pasiegos), continental ] and ] can be estimated as 5.6 percent, 3.6 percent and 6.6 percent, respectively".<ref name="pmid17351267">{{Cite journal | last1 = Cruciani | first1 = F. | last2 = La Fratta | first2 = R. | last3 = Trombetta | first3 = B. | last4 = Santolamazza | first4 = P. | last5 = Sellitto | first5 = D. | last6 = Colomb | first6 = E. B. | last7 = Dugoujon | first7 = J. -M. | last8 = Crivellaro | first8 = F. | last9 = Benincasa | first9 = T. | doi = 10.1093/molbev/msm049 | title = Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12 | journal = Molecular Biology and Evolution | volume = 24 | issue = 6 | pages = 1300–1311 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17351267| doi-access = free }}</ref> A 2007 study estimated the contribution of northern African lineages to the entire male gene pool of Iberia as 5.6%."<ref>{{cite journal |doi=10.1093/molbev/msm049 |title=Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12 |year=2007 |last1=Cruciani |first1=F. |last2=La Fratta |first2=R. |last3=Trombetta |first3=B. |last4=Santolamazza |first4=P. |last5=Sellitto |first5=D. |last6=Colomb |first6=E. B. |last7=Dugoujon |first7=J.-M. |last8=Crivellaro |first8=F. |last9=Benincasa |first9=T. |last10=Pascone |first10=R. |last11=Moral |first11=P. |last12=Watson |first12=E. |last13=Melegh |first13=B. |last14=Barbujani |first14=G. |last15=Fuselli |first15=S. |last16=Vona |first16=G. |last17=Zagradisnik |first17=B. |last18=Assum |first18=G. |last19=Brdicka |first19=R. |last20=Kozlov |first20=A. I. |last21=Efremov |first21=G. D. |last22=Coppa |first22=A. |last23=Novelletto |first23=A. |last24=Scozzari |first24=R. |journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution |volume=24 |issue=6 |pages=1300–11 |pmid=17351267|doi-access=free }}</ref> In general aspects, according to (Bosch et al. 2007) "...the origins of the Iberian Y-chromosome pool may be summarized as follows: 5% recent NW African, 78% Upper Paleolithic and later local derivatives (group IX), and 10% Neolithic" (H58, H71).<ref>{{cite journal|pmc=1275654 | pmid=11254456 | doi=10.1086/319521 | volume=68 | issue=4 | title=High-resolution analysis of human Y-chromosome variation shows a sharp discontinuity and limited gene flow between northwestern Africa and the Iberian Peninsula | date=April 2001 | journal=Am. J. Hum. Genet. | pages=1019–29 | last1 = Bosch | first1 = E | last2 = Calafell | first2 = F | last3 = Comas | first3 = D | last4 = Oefner | first4 = PJ | last5 = Underhill | first5 = PA | last6 = Bertranpetit | first6 = J}}</ref> | |||

| Mitochondrial DNA studies of 2003, coincide in that the Iberian Peninsula holds higher levels of typically North African Haplotype U6,<ref name="gonzalez2003" /><ref name="plaza2003">{{cite journal |doi=10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00039.x |title=Joining the Pillars of Hercules: mtDNA Sequences Show Multidirectional Gene Flow in the Western Mediterranean |year=2003 |last1=Plaza |first1=S. |first2=F. |first3=A. |first4=N. |first5=G. |first6=J. |first7=D. |journal=Annals of Human Genetics |volume=67 |pmid=12914566 |issue=Pt 4 |last2=Calafell |last3=Helal |last4=Bouzerna |last5=Lefranc |last6=Bertranpetit |last7=Comas |s2cid=11201992 |pages=312–28}}</ref> as well as higher frequencies of Sub-Saharan African Haplogroup L in Portugal.<ref name="Pereira 2005">{{cite journal|last1=Pereira|first1=Luisa|last2=Cunha|first2=Carla|last3=Alves|first3=Cintia|last4=Amorim|first4=Antonio|year=2005|title=African Female Heritage in Iberia: A Reassessment of mtDNA Lineage Distribution in Present Times|journal=Human Biology|volume=77|issue=2|pages=213–29|doi=10.1353/hub.2005.0041|pmid=16201138|hdl-access=free|hdl=10216/109268|s2cid=20901589}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Cerezo |first1=M. |last2=Achilli |first2=A. |last3=Olivieri |first3=A. |last4=Perego |first4=U. A. |last5=Gomez-Carballa |first5=A. |last6=Brisighelli |first6=F. |last7=Lancioni |first7=H. |last8=Woodward |first8=S. R. |last9=Lopez-Soto |first9=M. |last10=Carracedo |first10=A. |last11=Capelli |first11=C. |last12=Torroni |first12=A. |last13=Salas |first13=A. |title=Reconstructing ancient mitochondrial DNA links between Africa and Europe |journal=Genome Research |date=27 March 2012 |volume=22 |issue=5 |pages=821–826 |doi=10.1101/gr.134452.111 |pmid=22454235 |pmc=3337428 }}</ref><ref name="Brehm A, Pereira L, Kivisild T, Amorim A 2003 77–86">{{cite journal |vauthors=Brehm A, Pereira L, Kivisild T, Amorim A |title=Mitochondrial portraits of the Madeira and Açores archipelagos witness different genetic pools of its settlers |journal=Human Genetics |volume=114 |issue=1 |pages=77–86 |date=December 2003 |pmid=14513360 |doi=10.1007/s00439-003-1024-3 |s2cid=8870699 |hdl=10400.13/3046 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref name="biomedcentral.com">{{cite journal |last1=Hernández |first1=Candela L |last2=Reales |first2=Guillermo |last3=Dugoujon |first3=Jean-Michel |last4=Novelletto |first4=Andrea |last5=Rodríguez |first5=Juan |last6=Cuesta |first6=Pedro |last7=Calderón |first7=Rosario |title=Human maternal heritage in Andalusia (Spain): its composition reveals high internal complexity and distinctive influences of mtDNA haplogroups U6 and L in the western and eastern side of region |journal=BMC Genetics |date=2014 |volume=15 |issue=1 |pages=11 |doi=10.1186/1471-2156-15-11 |pmid=24460736 |pmc=3905667 |doi-access=free }}</ref> High frequencies are largely concentrated in the south and southwest of the Iberian peninsula, therefore overall frequency is higher in ] (7.8%) than in ] (1.9%) with a mean frequency for the entire peninsula of 3.8%. There is considerable geographic divergence across the peninsula with high frequencies observed for Western Andalusia (14.6%)<ref name="biomedcentral.com" /> and Córdoba (8.3%).,<ref name="Pereira 2005" /> Southern Portugal (10.7%), South West Castile (8%). Adams et al. and other previous publications, propose that the ] left a minor ], ]<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F3QzDwAAQBAJ&q=Saqaliba+portugal&pg=PA137 | title=Concubines and Courtesans: Women and Slavery in Islamic History| isbn=9780190622183| last1=Gordon| first1=Matthew| last2=Hain| first2=Kathryn A.| year=2017| publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> and some ] genetic influence mainly in southern regions of Iberia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://academic.oup.com/mbe/article/24/6/1300/984002 |title=Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia |publisher=Academic.oup.com |access-date=2020-01-21}}</ref><ref name="pmid19061982" /> | |||

| The most recent and comprehensive genomic studies establish that ] genetic ancestry can be identified throughout most of the ], ranging from 0% to 12%, but is highest in the south and west, while being absent or almost absent in the ] and northeast.<ref>https://reich.hms.harvard.edu/sites/reich.hms.harvard.edu/files/inline-files/2019_Olalde_Science_IberiaTransect_2.pdf {{Bare URL PDF|date=March 2022}}</ref><ref name="Bycroft2019"/><ref name="Olalde2019"/> Hernandez et al. (2020) identified 11.17 ± 1.87% North African ancestry in southern Portuguese samples (from a population similar to modern northern Moroccans and Algerians), 9.28 ± 1.79% of such ancestry in western Andalusians, and an average of 1.41 ± 0.72% sub-Saharan ancestry in southern Iberians (using ] as a proxy source).<ref name="pmid31816048" /> Lazarids et al. (2014) detected 12.6 ± 2% North African ancestry and an average of 1.5 ± 0.2% sub-Saharan ancestry in the Spanish population.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lazaridis |first=Iosif |last2=Patterson |first2=Nick |last3=Mittnik |first3=Alissa |last4=Renaud |first4=Gabriel |last5=Mallick |first5=Swapan |last6=Kirsanow |first6=Karola |last7=Sudmant |first7=Peter H. |last8=Schraiber |first8=Joshua G. |last9=Castellano |first9=Sergi |last10=Lipson |first10=Mark |last11=Berger |first11=Bonnie |last12=Economou |first12=Christos |last13=Bollongino |first13=Ruth |last14=Fu |first14=Qiaomei |last15=Bos |first15=Kirsten I. |date=17 September 2014 |title=Ancient human genomes suggest three ancestral populations for present-day Europeans |url=https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/instance/4170574/bin/NIHMS613260-supplement-supplement_1.pdf |journal=Nature |language=en |volume=513 |issue=7518 |pages=409–413 |doi=10.1038/nature13673 |issn=1476-4687}}</ref> | |||

| Current debates revolve around whether U6 presence is due to Islamic expansion into the Iberian peninsula or prior population movements<ref name="pmid19061982" /><ref name="gonzalez2003" /><ref name="ReferenceA" /> and whether Haplogroup L is linked to the slave trade or prior population movements linked to Islamic expansion. A majority of Haplogroup L lineages in Iberia being North African in origin points to the latter.<ref name="Pereira 2005" /><ref name="Brehm A, Pereira L, Kivisild T, Amorim A 2003 77–86" /><ref name="Moorjani+2011" /><ref name="gonzalez2003" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Alvarez |first1=Luis |last2=Santos |first2=Cristina |last3=Ramos |first3=Amanda |last4=Pratdesaba |first4=Roser |last5=Francalacci |first5=Paolo |last6=Aluja |first6=María Pilar |title=Mitochondrial DNA patterns in the Iberian Northern plateau: Population dynamics and substructure of the Zamora province |journal=American Journal of Physical Anthropology |date=1 February 2010 |volume=142 |issue=4 |pages=531–539 |doi=10.1002/ajpa.21252 |pmid=20127843 }}</ref> In 2015, Hernández et al. concluded that "the estimated entrance of the North African U6 lineages into Iberia at 10 ky correlates well with other L African clades, indicating that some U6 and L lineages moved together from Africa to Iberia in the Early ] while a majority were introduced during historic times."<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hernández |first1=Candela L. |last2=Soares |first2=Pedro |last3=Dugoujon |first3=Jean M. |last4=Novelletto |first4=Andrea |last5=Rodríguez |first5=Juan N. |last6=Rito |first6=Teresa |last7=Oliveira |first7=Marisa |last8=Melhaoui |first8=Mohammed |last9=Baali |first9=Abdellatif |last10=Pereira |first10=Luisa |last11=Calderón |first11=Rosario |last12=Achilli |first12=Alessandro |title=Early Holocenic and Historic mtDNA African Signatures in the Iberian Peninsula: The Andalusian Region as a Paradigm |journal=PLOS ONE |date=28 October 2015 |volume=10 |issue=10 |pages=e0139784 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0139784 |pmid=26509580 |pmc=4624789 |bibcode=2015PLoSO..1039784H |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| == Haplogroups == | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Y-Chromosome haplogroups=== | ===Y-Chromosome haplogroups=== | ||

| {{Main|Haplogroup R-DF27}} | {{Main|Haplogroup R-DF27}} | ||

| Y-DNA ] is the most frequent |

Like other Western Europeans, among Spaniards and Portuguese the Y-DNA ] is the most frequent, occurring at over 70% throughout most of Spain.<ref name="myres">{{cite journal|last1=Myres|first1=Natalie M|last2=Rootsi|first2=Siiri|last3=Lin|first3=Alice A|last4=Järve|first4=Mari|last5=King|first5=Roy J|last6=Kutuev|first6=Ildus|last7=Cabrera|first7=Vicente M|last8=Khusnutdinova|first8=Elza K|last9=Pshenichnov|first9=Andrey|last10=Yunusbayev|first10=Bayazit|last11=Balanovsky|first11=Oleg|date=25 August 2010|title=A major Y-chromosome haplogroup R1b Holocene era founder effect in Central and Western Europe|journal=European Journal of Human Genetics|volume=19|issue=1|pages=95–101|doi=10.1038/ejhg.2010.146|pmc=3039512|pmid=20736979|last16=Chiaroni|first15=Rene J|last12=Balanovska|first12=Elena|first13=Pavao|last14=Baldovic|first14=Marian|last15=Herrera|first20=Peter A|first16=Jacques|last20=Underhill|first19=Toomas|last19=Kivisild|first18=Richard|last18=Villems|first17=Julie|last17=Di Cristofaro|last13=Rudan}}</ref> R1b is particularly dominant in the Basque Country and Catalonia, occurring at rate of over 80%. In Iberia, most men with R1b belong to the subclade R-P312 (R1b1a1a2a1a2; as of 2017). The distribution of haplogroups other than R1b varies widely from one region to another. | ||

| In Portugal as a whole the R1b haplogroups rate 70%, with some areas in the Northwest regions reaching over 90%.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Marques|first1=Sofia L.|last2=Goios|first2=Ana|last3=Rocha|first3=Ana M.|last4=Prata|first4=Maria João|last5=Amorim|first5=António|last6=Gusmão|first6=Leonor|last7=Alves|first7=Cíntia|last8=Alvarez|first8=Luis|date=March 2015|title=Portuguese mitochondrial DNA genetic diversity—An update and a phylogenetic revision|journal=Forensic Science International: Genetics|volume=15|pages=27–32|doi=10.1016/j.fsigen.2014.10.004|pmid=25457629}}</ref> | |||

| Although R1b prevails in much of Western Europe, a key difference is found in the prevalence in Iberia of R-DF27 (R1b1a1a2a1a2a). This subclade is found in over 60% of the male population in the Basque Country and 40-48% in Madrid, Alicante, Barcelona, Cantabria, Andalucia, Asturias and Galicia.<ref>New clues to the evolutionary history of the main European paternal lineage M269: dissection of the Y-SNP S116 in Atlantic Europe and Iberia</ref> R-DF27 constitutes much more than the half of the total R1b in the Iberian Peninsula. Subsequent in-migration by members of other haplogroups and subclades of R1b did not affect its overall prevalence, although this falls to only two thirds of the total R1b in ] and the coast more generally.<ref name=myres/> R-DF27 is also a significant subclade of R1b in parts of France and Britain. However, it is insignificant in Italy; R-S28/R-U152 (R1b1a1a2a1a2b) is the prevailing subclade of R1b in Italy, Switzerland and parts of France, although it represents less than 5.0% of the male population in Iberia. This underlines the lack of any significant genetic impact on the part of Rome, even though the Latin spoken in the Roman Empire was the most significant, or main, source of the modern Spanish and Portuguese language. R-S28/R-U152 is slightly significant in ] and ], at 10-20% of the total population, although it is represented at frequencies of only 3.0% in ] and ], 2.0% in ], 6% in ], and under 1% in ].<ref name=myres/> | |||

| Although R1b prevails in much of Western Europe, a key difference is found in the prevalence in Iberia of R-DF27 (R1b1a1a2a1a2a). This subclade is found in over 60% of the male population in the Basque Country and 40-48% in Madrid, Alicante, Barcelona, Cantabria, Andalucia, Asturias and Galicia.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Valverde|first1=Laura|last2=Illescas|first2=Maria José|last3=Villaescusa|first3=Patricia|last4=Gotor|first4=Amparo M.|last5=García|first5=Ainara|last6=Cardoso|first6=Sergio|last7=Algorta|first7=Jaime|last8=Catarino|first8=Susana|last9=Rouault|first9=Karen|last10=Férec|first10=Claude|last11=Hardiman|first11=Orla|date=March 2016|title=New clues to the evolutionary history of the main European paternal lineage M269: dissection of the Y-SNP S116 in Atlantic Europe and Iberia|journal=European Journal of Human Genetics|volume=24|issue=3|pages=437–441|doi=10.1038/ejhg.2015.114|pmc=4755366|pmid=26081640|last16=Olofsson|first16=Jill|last17=Morling|first17=Niels|last18=de Pancorbo|first18=Marian M.|first15=Begoña M.|last15=Jarreta|first14=Maria Fátima|last14=Pinheiro|first13=Susana|last13=Jiménez|first12=Maite|last12=Zarrabeitia}}</ref> R-DF27 constitutes much more than the half of the total R1b in the Iberian Peninsula. Subsequent in-migration by members of other haplogroups and subclades of R1b did not affect its overall prevalence, although this falls to only two thirds of the total R1b in ] and the coast more generally.<ref name=myres/> R-DF27 is also a significant subclade of R1b in parts of France and Britain. R-S28/R-U152 (R1b1a1a2a1a2b) is the prevailing subclade of R1b in Northern Italy, Switzerland and parts of France, but it represents less than 5.0% of the male population in Iberia. Ancient samples from the central European ], ] and ] belonged to this subclade.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Olalde|first1=Iñigo|last2=Brace|first2=Selina|last3=Allentoft|first3=Morten E.|last4=Armit|first4=Ian|last5=Kristiansen|first5=Kristian|last6=Booth|first6=Thomas|last7=Rohland|first7=Nadin|last8=Mallick|first8=Swapan|last9=Szécsényi-Nagy|first9=Anna|last10=Mittnik|first10=Alissa|last11=Altena|first11=Eveline|display-authors=29|date=March 2018|title=The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe|journal=Nature|volume=555|issue=7695|pages=190–196|bibcode=2018Natur.555..190O|doi=10.1038/nature25738|pmc=5973796|pmid=29466337|last16=Broomandkhoshbacht|last104=Luke|first106=Jocelyne|last106=Desideri|first105=Richard|last105=Mortimer|first104=Mike|last103=Brittain|first103=Marcus|first107=Marie|first102=Benjamin|last102=Neil|first101=Elisa|last101=Guerra-Doce|last107=Besse|last109=Furmanek|last108=Brücken|first108=Günter|last100=Delibes|first109=Mirosław|last110=Hałuszko|first110=Agata|last111=Mackiewicz|first111=Maksym|last112=Rapiński|first112=Artur|last113=Leach|first113=Stephany|last114=Soriano|first114=Ignacio|last115=Lillios|first100=Germán|last99=Waddington|first99=Clive|last91=Brown|first84=Zsolt|last85=Hoole|first85=Maya|last86=Cheronet|first86=Olivia|last87=Keating|first87=Denise|last88=Velemínský|first88=Petr|last89=Dobeš|first89=Miroslav|last90=Candilio|first90=Francesca|first91=Fraser|last116=Cardoso|last92=Fernández|first92=Raúl Flores|last93=Herrero-Corral|first93=Ana-Mercedes|last94=Tusa|first94=Sebastiano|last95=Carnieri|first95=Emiliano|last96=Lentini|first96=Luigi|last97=Valenti|first97=Antonella|last98=Zanini|first98=Alessandro|first115=Katina T.|last117=Pearson|first116=João Luís|first140=Ron|last134=Fokkens|first134=Harry|last135=Heyd|first135=Volker|last136=Sheridan|first136=Alison|last137=Sjögren|first137=Karl-Göran|last138=Stockhammer|first138=Philipp W.|last139=Krause|first139=Johannes|last140=Pinhasi|last141=Haak|last133=Kennett|first141=Wolfgang|last142=Barnes|first142=Ian|last143=Lalueza-Fox|first143=Carles|last144=Reich|first144=David|last15=Patterson|first14=Thomas K.|last14=Harper|first13=Iosif|last13=Lazaridis|first12=Mark|last12=Lipson|first133=Douglas J.|first132=Mark G.|first83=János|last124=Schmitt|first117=Michael Parker|last118=Włodarczak|first118=Piotr|last119=Price|first119=T. Douglas|last120=Prieto|first120=Pilar|last121=Rey|first121=Pierre-Jérôme|last122=Risch|first122=Roberto|last123=Rojo Guerra|first123=Manuel A.|first124=Aurore|last132=Thomas|last125=Serralongue|first125=Joël|last126=Silva|first126=Ana Maria|last127=Smrčka|first127=Václav|last128=Vergnaud|first128=Luc|last129=Zilhão|first129=João|last130=Caramelli|first130=David|last131=Higham|first131=Thomas|last84=Bernert|last83=Dani|first16=Nasreen|first40=Lindsey|last34=Bánffy|first34=Eszter|last35=Bernabò-Brea|first35=Maria|last36=Billoin|first36=David|last37=Bonsall|first37=Clive|last38=Bonsall|first38=Laura|last39=Allen|first39=Tim|last40=Büster|last41=Carver|last33=Fernández|first41=Sophie|last42=Navarro|first42=Laura Castells|last43=Craig|first43=Oliver E.|last44=Cook|first44=Gordon T.|last45=Cunliffe|first45=Barry|last46=Denaire|first46=Anthony|last47=Dinwiddy|first47=Kirsten Egging|last48=Dodwell|first33=Azucena Avilés|first32=Roberto Menduiña|last49=Ernée|last24=Oppenheimer|last17=Diekmann|first17=Yoan|last18=Faltyskova|first18=Zuzana|last19=Fernandes|first19=Daniel|last20=Ferry|first20=Matthew|last21=Harney|first21=Eadaoin|last22=de Knijff|first22=Peter|last23=Michel|first23=Megan|first24=Jonas|last32=García|last25=Stewardson|first25=Kristin|last26=Barclay|first26=Alistair|last27=Alt|first27=Kurt Werner|last28=Liesau|first28=Corina|last29=Ríos|first29=Patricia|last30=Blasco|first30=Concepción|last31=Miguel|first31=Jorge Vega|first48=Natasha|first49=Michal|first82=Tamás|first74=Alessandra|first67=Virginia Galera|last68=Ramírez|first68=Ana Bastida|last69=Maurandi|first69=Joaquín Lomba|last70=Majó|first70=Tona|last71=McKinley|first71=Jacqueline I.|last72=McSweeney|first72=Kathleen|last73=Mende|first73=Balázs Gusztáv|last74=Modi|last75=Kulcsár|first66=César Heras|first15=Nick|last76=Kiss|first76=Viktória|last77=Czene|first77=András|last78=Patay|first78=Róbert|last79=Endrődi|first79=Anna|last80=Köhler|first80=Kitti|last81=Hajdu|first81=Tamás|last82=Szeniczey|last67=Olmo|last66=Martínez|last50=Evans|first57=Elżbieta|first50=Christopher|last51=Kuchařík|first51=Milan|last52=Farré|first52=Joan Francès|last53=Fowler|first53=Chris|last54=Gazenbeek|first54=Michiel|last55=Pena|first55=Rafael Garrido|last56=Haber-Uriarte|first56=María|last57=Haduch|last58=Hey|first65=Arnaud|first58=Gill|last59=Jowett|first59=Nick|last60=Knowles|first60=Timothy|last61=Massy|first61=Ken|last62=Pfrengle|first62=Saskia|last63=Lefranc|first63=Philippe|last64=Lemercier|first64=Olivier|last65=Lefebvre|first75=Gabriella}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Allentoft|first1=Morten E.|last2=Sikora|first2=Martin|last3=Sjögren|first3=Karl-Göran|last4=Rasmussen|first4=Simon|last5=Rasmussen|first5=Morten|last6=Stenderup|first6=Jesper|last7=Damgaard|first7=Peter B.|last8=Schroeder|first8=Hannes|last9=Ahlström|first9=Torbjörn|last10=Vinner|first10=Lasse|last11=Malaspinas|first11=Anna-Sapfo|date=June 2015|title=Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia|journal=Nature|volume=522|issue=7555|pages=167–172|bibcode=2015Natur.522..167A|doi=10.1038/nature14507|pmid=26062507|first15=Niels|last51=Shishlina|last56=Trifanova|first55=Gusztáv|last55=Tóth|first54=Vajk|last54=Szeverényi|first53=Vasilii I.|last53=Soenov|first52=Václav|last52=Smrčka|first51=Natalia|last50=Sablin|first50=Mikhail|last57=Varul|first49=Lehti|last49=Saag|first48=T. Douglas|last48=Price|first47=Łukasz|last47=Pospieszny|first46=Dalia|last46=Pokutta|first45=György|last45=Pálfi|first56=Synaru V.|last58=Vicze|first57=Liivi|first64=Rasmus|last12=Margaryan|first12=Ashot|last13=Higham|first13=Tom|last14=Chivall|first14=David|first66=Eske|last66=Willerslev|first65=Kristian|last65=Kristiansen|last64=Nielsen|last44=Paja|first63=Søren|last63=Brunak|first62=Thomas|last62=Sicheritz-Pontén|first61=Ludovic|last61=Orlando|first60=Vladislav|last60=Zhitenev|first59=Levon|last59=Yepiskoposyan|first58=Magdolna|first44=László|first43=Vyacheslav|last16=Harvig|first22=Andrey|last28=Grupe|first27=Stanisław|last27=Gronkiewicz|first26=Andrey|last26=Gromov|first25=Tomasz|last25=Gralak|first24=Mirosław|last24=Furmanek|first23=Karin|last23=Frei|last22=Epimakhov|last29=Hajdu|first21=Alexander V.|last21=Ebel|first20=Paul R.|last20=Duffy|first19=Paweł|last19=Dąbrowski|first18=Philippe Della|last18=Casa|first17=Justyna|last17=Baron|first16=Lise|first28=Gisela|first29=Tamás|last43=Moiseyev|last37=Longhi|first42=Ruzan|last42=Mkrtchyan|first41=Mait|last41=Metspalu|first40=Inga|last40=Merkyte|first39=Algimantas|last39=Merkevicius|first38=George|last38=McGlynn|first37=Cristina|first36=Irena|last30=Jarysz|last15=Lynnerup|first35=Aivar|last35=Kriiska|first34=Jan|last34=Kolář|first33=Viktória|last33=Kiss|first32=Alexandr|last32=Khokhlov|first31=Valeri|last31=Khartanovich|first30=Radosław|last36=Lasak|s2cid=4399103|url=https://depot.ceon.pl/handle/123456789/13155}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Peter de Barros|first1=Damgaard|date=9 May 2018|title=137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes|journal=Nature|volume=557|issue=7705|pages=369–374|bibcode=2018Natur.557..369D|doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2|pmid=29743675|hdl=1887/3202709 |s2cid=13670282|hdl-access=free}}</ref> R-S28/R-U152 is slightly significant in ], ], ] and ] at 10-20% of the total population, but it is represented at frequencies of only 3.0% in ] and ], 2.0% in ], 6% in ], and under 1% in ].<ref name=myres/> | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] 0% I2*/I2a 1% ] 0% ]1a 5% R1b 13% ] 15% ] 2 25% ]*/J1 22% ]1b1b 9% ] 6% ] 2% | ] 0% I2*/I2a 1% ] 0% ]1a 5% R1b 13% ] 15% ] 2 25% ]*/J1 22% ]1b1b 9% ] 6% ] 2% | ||

| <ref>http://www.eupedia.com/genetics/spain_portugal_dna.shtml#frequency</ref> | <ref>{{Cite web|title=Eupedia|url=http://www.eupedia.com/genetics/spain_portugal_dna.shtml#frequency}}</ref> | ||

| ], mostly subclades of ] (J2), is found at levels of over 20% in some regions, while ] has a general frequency of about 10% – albeit with peaks surpassing 30% in certain areas. Overall, ] (E1b1b1a1 in 2017) and ] (E1b1b1b1a in 2017) both constitute about 4.0% each, with a further 1.0% from ] (E1b1b1b2a1) and 1.0% from unknown subclades of E-M96.<ref name=pmid19061982/> (E-M81 is widely considered to represent relatively historical migrations from North Africa). | ], mostly subclades of ] (J2), is found at levels of over 20% in some regions, while ] has a general frequency of about 10% – albeit with peaks surpassing 30% in certain areas. Overall, ] (E1b1b1a1 in 2017) and ] (E1b1b1b1a in 2017) both constitute about 4.0% each, with a further 1.0% from ] (E1b1b1b2a1) and 1.0% from unknown subclades of E-M96.<ref name=pmid19061982/> (E-M81 is widely considered to represent relatively historical migrations from North Africa). | ||

| ===Mitochondrial DNA=== | |||

| ;Frequencies of Y-DNA haplogroups in Spanish regions <ref name=pmid19061982 /><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Flores|first1=Carlos|last2=Maca-Meyer|first2=Nicole|last3=González|first3=Ana M.|last4=Oefner|first4=Peter J.|last5=Shen|first5=Peidong|last6=Pérez|first6=Jose A.|last7=Rojas|first7=Antonio|last8=Larruga|first8=Jose M.|last9=Underhill|first9=Peter A.|title=Reduced genetic structure of the Iberian peninsula revealed by Y-chromosome analysis: implications for population demography|journal=European Journal of Human Genetics|date=28 July 2004|volume=12|issue=10|pages=855–863|doi=10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201225|url=http://www.nature.com/ejhg/journal/v12/n10/full/5201225a.html|language=en|issn=1018-4813|pmid=15280900}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Main|Haplogroup H (mtDNA)|Haplogroup U (mtDNA)}} | |||

| There have been a number of studies about the ] (mtDNA) in Europe. In contrast to Y DNA haplogroups, '''mtDNA''' haplogroups did not show as much geographical patterning, but were more evenly ubiquitous. Apart from the outlying ], all Europeans are characterized by the predominance of haplogroups ], ] and ]. The lack of observable geographic structuring of mtDNA may be due to socio-cultural factors, namely ] and a lack of ].<ref name="harvcoltxt|Rosser et al.|2000">{{harvcoltxt|Rosser et al.|2000}}</ref> | |||

| The subhaplogroups H1 and H3 have been subject to a more detailed study and would be associated to the ] expansion from Iberia c. 13,000 years ago:<ref name="Pereira 2005" /> | |||

| * H1 encompasses an important fraction of Western European mtDNA, reaching its local peak among contemporary ] (27.8%) and appearing at a high frequency among other ] and ]ns. Its frequency is above 10% in many other parts of Europe (], ], ], Alps, large portions of ]), and above 5% in nearly all the continent. Its subclade '''H1b''' is most common in eastern Europe and NW Siberia.<ref name="Loogväli">{{cite journal|vauthors=Loogväli EL, Roostalu U, Malyarchuk BA, etal|date=November 2004|title=Disuniting uniformity: a pied cladistic canvas of mtDNA haplogroup H in Eurasia|journal=Molecular Biology and Evolution|volume=21|issue=11|pages=2012–21|doi=10.1093/molbev/msh209|pmid=15254257|doi-access=free}}</ref> So far, the highest frequency of H1 - 61%- has been found among the ] of the ] region in ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Ottoni|first1=Claudio|last2=Primativo|first2=Giuseppina|last3=Hooshiar Kashani|first3=Baharak|last4=Achilli|first4=Alessandro|last5=Martínez-Labarga|first5=Cristina|last6=Biondi|first6=Gianfranco|last7=Torroni|first7=Antonio|last8=Rickards|first8=Olga|last9=Kayser|first9=Manfred|date=21 October 2010|title=Mitochondrial Haplogroup H1 in North Africa: An Early Holocene Arrival from Iberia|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=5|issue=10|pages=e13378|bibcode=2010PLoSO...513378O|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0013378|pmc=2958834|pmid=20975840|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| * H3 represents a smaller fraction of European genome than H1 but has a somewhat similar distribution with peak among Basques (13.9%), ] (8.3%) and ] (8.5%). Its frequency decreases towards the northeast of the continent, though. Studies have suggested haplogroup H3 is highly protective against AIDS progression.<ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Hendrickson SL, Hutcheson HB, Ruiz-Pesini E, etal|date=November 2008|title=Mitochondrial DNA Haplogroups influence AIDS Progression|journal=AIDS|volume=22|issue=18|pages=2429–39|doi=10.1097/QAD.0b013e32831940bb|pmc=2699618|pmid=19005266}}</ref> | |||