| Revision as of 11:03, 25 December 2020 editTrangaBellam (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers22,563 edits No Indian region or Afghan region of Swat exists.Tag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:31, 21 September 2024 edit undoRamos1990 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,318 edits restore - such foreign text not in source | ||

| (94 intermediate revisions by 22 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description| |

{{Short description|Pakistani ethnic group}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date= |

{{Use dmy dates|date=May 2022}} | ||

| {{EngvarB|date=November 2020}} | {{EngvarB|date=November 2020}} | ||

| {{Infobox ethnic group| | {{Infobox ethnic group| | ||

| | group = Torwali people | | group = Torwali people | ||

| | image = | | image = | ||

| | caption = | | caption = | ||

| | poptime = | | poptime = | ||

| | regions = ] | | regions = ] | ||

| | region1 = {{flag|Pakistan}} | | region1 = {{flag|Pakistan}} | ||

| | ref1 = | |||

| | pop1 = 100,000<ref name="Shah2013"/> | |||

| | |

| region2 = | ||

| | |

| pop2 = | ||

| | |

| ref2 = | ||

| ⚫ | | rels = Predominantly ] | ||

| | ref2 = | |||

| ⚫ | | langs = ] | ||

| ⚫ | | rels = Predominantly ] | ||

| ⚫ | | related = Other ] | ||

| ⚫ | | langs = ] | ||

| ⚫ | | native_name = | ||

| ⚫ | | related = |

||

| ⚫ | | native_name = | ||

| | native_name_lang = | | native_name_lang = | ||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Torwali people''' are an ] ] located in the ] district of ]. The Torwali people have a culture that values the telling of folktales and music that is played using the ].<ref name="Torwali2016"/> They speak an ] called ].<ref name="Shah2013"/> | |||

| The '''Torwali people''' are an ] ethnic group located in the ] district of ].<ref name="EW1983">{{cite book |title=East and West, Volume 33 |date=1983 |publisher=Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente |page=27 |language=English|quote=According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist Orgyan pa forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375) ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70 ).}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Baart |first1=Joan L. G. |last2=Sindhi |first2=Ghulam Hyder| |title=Pakistani languages and society problems and prospects |date=2003 |publisher=National Institute of Pakistan Studies |isbn=978-969-8023-17-1 |language=English |quote=However, the current location of this community is in Swat, where it is surrounded by Torwali-speaking people.}}</ref> Until A.D. 1021, the Torwali people mainly practiced Hinduism and Buddhism under the rule of the ] king Raja Gira; at the time of the ], many of the Torwali converted from these religions to Islam.<ref name="UrRahimViaro2002">{{cite book |last1=ur-Rahim |first1=Inam |last2=Viaro |first2=Alain M. |title=Swat: An Afghan society in Pakistan: Urbanisation and Change in a Tribal Environment |date=2002 |publisher=Institut universitaire d'études du développement |page=60-61|quote=The conquest of the Peshawar basin in 1001 marks the beginning of the Muslim invasions into northern India. The Peshawar plain was annexed to the Ghaznavid kingdom, and the Afghan tribesmen in the Bannu area were soon subdued. Swat, Dir and Bajour, cut off from the eastern Hindu Shahi territories succumbed quickly to Mahmud's army (1021?). Two thousand feet above the plain at Udigram in Swat stands a massive ruined fort. The grand staircase leading up to Raja Gira, the last Hindu defender of Swat, who was defeated after a long siege, built the fort. According to local tradition, Mahmud's commander Khushhal Khan died during this siege and is buried where the shrine of Pir Khushhal Khan Baba stands in a grove of trees. After the conquest of Swat, the Ghaznavids strengthened and extended the defences at Udigram. Other local forts and castles were also turned into garrison towns. The Hindu and Buddhist local population had no choice, either to convert to Islam or to be killed. The part of population, which did not convert to Islam, was driven into the mountains north of Madyan. Dilazak Afghans, allied to Mahmud, took over the land and settled there.}}</ref><ref name="AdamsonShaw1981"/><ref name="EW1983"/> The Torwali people have a rich culture, including the telling of folktales and music that is played using the ].<ref name="Torwali2016"/> | |||

| == |

== Description == | ||

| ] | |||

| ] |access-date=25 December 2020 |language=English |date=6 March 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Castle of the last Hindu King Raja Gira in Swat |url=https://www.geo.tv/mustwatch/225481-castle-of-the-last-hindu-king-raja-gira-in-swat |publisher=] |access-date=25 December 2020 |language=English |date=18 January 2019}}</ref>]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The Torwali people are native to the region of ], located in the northwestern region of ].<ref name="Shah2013"/><ref name="EW1983"/> The Torwali were originally ]s and ]s; in the 11th century, the Hindu king Raja Gira and his subjects were attacked by ] during that period of the ].<ref name="CheemaMahmudBillah2008">{{cite book |last1=Cheema |first1=Pervaiz Iqbal |last2=Mahmud |first2=Muneer |last3=Billah |first3=Mustansar |title=Pakistan and Changing Scenario: Regional and Global |date=2008 |publisher=Islamabad Policy Research Institute |isbn=978-969-8721-22-0 |page=136 |language=English|quote=In 1021 A.D., Mehmood of Ghazani led an expedition in Bajour, Dir and Swat and Hinduism received its death blow in these areas. At that time, Swat was ruled by Raja Gira. Mehmood of Ghazani defeated the army of Raja Gira near ...}}</ref><ref name="EW1983"/><ref name="AdamsonShaw1981"/> As such, by the 17th century, most of Swat's population converted from ] and ] to Islam,<ref name="UrRahimViaro2002"/><ref name="EW1983"/> with the Torwali who remained Hindu and Buddhist fleeing to the mountains of ].<ref name="UrRahimViaro2002"/> The ruins of Raja Gira's fort are still visible today.<ref name="WadudK̲h̲ān̲1963">{{cite book |last1=Wadud |first1=Abdul Wadud |last2=K̲h̲ān̲ |first2=Muḥammad Āṣif |title=The Story of Swat as Told by the Founder Miangul Abdul Wadud Badshah Sahib to Muhammad Asif Khan |date=1963 |page=xv |language=English |quote=The last of these, Raja Gira, ruled over Swat till the beginning of the eleventh century A.D. On hill near Udigram, he built a big cantonment, the ruins of which can be seen even today.}}</ref><ref name="AdamsonShaw1981">{{cite book |last1=Adamson |first1=Hilary |last2=Shaw |first2=Isobel |title=A Traveller's Guide to Pakistan |date=1981 |publisher=Asian Study Group |page=156 |language=English|quote=The climb up to the Hindu Shahi ruins of Raja Gira's castle, though steep, is rewarding, with fine views of the Swat valley and distant mountains as you get ...}}</ref> | |||

| The Torwalis inhabit the ] valley between Laikot (a little south of ]) down to and including the village of ] (60 km north of ]). The Torwalis live in compact villages of up to 600 houses, mainly on the west bank of the Swat River. Fredrik Barth estimated that they constituted about 2000 households in all in 1956. All the Torwalis he met were bilingual, speaking ] and ].{{sfn|Barth|1956|p=69}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| The Torwali people are believed to be among the earliest natives to the region of ].<ref name="Shah2013"/> The ] is the closest modern ] still spoken today to ''Niya'', a dialect of ], a ] spoken in the ancient region of ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Burrow |first=T. |date=1936 |title=The Dialectical Position of the Niya Prakrit |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/608051 |journal=Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London |volume=8 |issue=2/3 |pages=419–435 |jstor=608051 |issn=1356-1898 |quote=... It might be going too far to say that Torwali is the direct lineal descendant of the Niya Prakrit, but there is no doubt that out of all the modern languages it shows the closest resemblance to it. A glance at the map in the Linguistic Survey of India shows that the area at present covered by "Kohistani" is the nearest to that area round Peshawar, where, as stated above, there is most reason to believe was the original home of the Niya Prakrit. That conclusion, which was reached for other reasons, is thus confirmed by the distribution of the modern dialects.}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Salomon |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XYrG07qQDxkC&pg=PA79 |title=Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages |date=10 December 1998 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-535666-3 |pages=79 |language=en}}</ref> The Torwalis were native to a more extensive area, such as towards ], from where they were expelled into mountainous tracts by successive aggressive migration by ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Biddulph |first=John |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=P4tEAQAAMAAJ |title=Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh |date=1880 |publisher=Office of the superintendent of government printing |pages=69–70 |language=en |quote=...they must have once occupied some extensive valley like Boneyr, from whence they, like the rest, have been expelled and thrust up into the more mountainous tracts by the aggressive Afghans. By the Afghans they are called Kohistanis, a name given everywhere by Pathans to Mussulmans of Indic descent, living in the Hindoo Koosh Valleys.}}</ref> They are referred by pashtuns as "Kohistanis", which was the name given by them to "All other Muhammadans of ] in the ] valleys".<ref>{{harvnb|Barth|1956|p=}}. The Pathans call them, and all other Muhammadans of Indian descent in the Hindu Kush valleys, Kohistanis.</ref> | |||

| By the 17th century, in the aftermath of ] in the region, most of the Torwalis had converted from ] and ] to Islam; however, the strand was mostly superficial and elements of traditional culture were still heavily practised.<ref name="Scerrato1983">{{Cite journal|last=Scerrato|first=Umberto|date=1983|title=Labyrinths in the Wooden Mosques of North Pakistan. A Problematic Presence|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29756645|journal=East and West|volume=33|issue=1/4|pages=21–29|jstor=29756645|issn=0012-8376|quote=According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist ''O rgyan pa'' forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375). Islam finally established itself in Swāt only with the invasion of the Yusufzai in the 16th century, (Bellew, 1864, pp. 65-67; Raverty, 1878, p. 206); ... it must nevertheless have been an Islam superficially accepted by the local population, some of the ancient traditions still being very much alive: ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70).}}</ref><ref name="Bagnera2006">{{Cite journal|last=Bagnera|first=Alessandra|date=2006|title=Preliminary Note on the Islamic Settlement of Udegram, Swat: The Islamic Graveyard (11th-13th century A.D.)|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/29757687|journal=East and West|volume=56|issue=1/3|pages=205–228|jstor=29757687|issn=0012-8376}}</ref> | |||

| == Language == | == Language == | ||

| {{Main|Torwali language}} | {{Main|Torwali language}} | ||

| The Torwali people speak the ], an ] of the ] (Kohistani) |

The Torwali people speak the ], an ] of the ] (Kohistani) subgroup; the language was first documented by colonial archaeologist ] in around 1925, and the records were published by ] as 'Torwali: An Account of a Dardic Language of the Swat Kohistan' in 1929.<ref name="Shah2013">{{cite web |last1=Shah |first1=Danial |title=Torwali is a language |url=https://www.himalmag.com/torwali-is-a-language/ |publisher=] |access-date=3 December 2020 |language=en |date=30 September 2013}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite web|year=2020|editor-last=Eberhard|editor-first=David M.|editor2-last=Simons|editor2-first=Gary F.|editor3-last=Fennig|editor3-first=Charles D.|title=Torwali|url=https://www.ethnologue.com/language/trw|access-date=25 December 2020|website=Ethnologue: Languages of the World|publisher=SIL International|language=en|publication-place=Dallas, Texas|edition=23}}</ref> | ||

| It had approximately 102,000 speakers in 2016<ref name=":0" /> and by 2017, eight schools with instruction in the Torwali language had been established for Torwali students.<ref name="Torwali2019">{{Cite book|last=Torwali|first=Zubair|title=Teaching Writing to Children in Indigenous Languages : Instructional Practices from Global Contexts|date=18 February 2019|publisher=Routledge|isbn=978-1-351-04967-2|editor-last=Sherris|editor-first=Ari|language=en|chapter=Early Writing in Torwali in Pakistan|pages=44–69|doi=10.4324/9781351049672-3|s2cid=187240076 |editor-last2=Peyton|editor-first2=Joy Kreeft|chapter-url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/early-writing-torwali-pakistan-zubair-torwali/10.4324/9781351049672-3}}</ref> Before 2007, the language did not have a written tradition.<ref name="Torwali2019" /> | |||

| == Education == | |||

| By 2017, eight schools with instruction in the Torwali language were established for Torwali students.<ref name="SherrisPeyton2019">{{cite book |last1=Sherris |first1=Ari |last2=Peyton |first2=Joy Kreeft |title=Teaching Writing to Children in Indigenous Languages: Instructional Practices from Global Contexts |date=18 February 2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-04966-5 |page=51 |language=English}}</ref> The number of Torwali pupils participating in these schools are 867.<ref name="SherrisPeyton2019"/> | |||

| == Culture == | == Culture == | ||

| Unique to the Torwali people are traditional games, which were abandoned for more than six decades.<ref name=" |

Unique to the Torwali people are traditional games, which were abandoned for more than six decades.<ref name="Torwali2019" /> A festival held in ] known as ''Simam'' attempted to revive them in 2011.<ref name="Torwali2019" /> The Torwali people have a tradition of telling ].<ref>{{cite web|last1=Torwali|first1=Zubair|date=12 February 2016|title=Fading songs from the hills|url=https://www.thefridaytimes.com/fading-songs-from-the-hills/|access-date=25 December 2020|publisher=]|language=en}}</ref> | ||

| === Music === | |||

| The Torwali people have a tradition of telling ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Torwali |first1=Zubair |title=Fading songs from the hills |url=https://www.thefridaytimes.com/fading-songs-from-the-hills/ |publisher=] |access-date=25 December 2020 |language=English |date=12 February 2016|quote=Folktales play a critical role in the oral traditions of a community. These stories tell of the past of the community; its desires, how it deals with natural phenomena, and of course the social dialectics. They can also be good starting-points for further anthropological and linguistic research.}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | The Torwali people play music using the traditional South Asian instrument known as the ].<ref name="Torwali2016">{{cite web |last1=Torwali |first1=Zubair |title=Fading songs from the hills |url=https://www.thefridaytimes.com/fading-songs-from-the-hills/ |publisher=] |access-date=25 December 2020 |language=en |date=12 February 2016}}</ref> Modern Torwali songs influenced by ] or ] music are known as ''phal''.<ref name="Torwali2016" /> | ||

| == |

==References== | ||

| ⚫ | {{reflist|30em}} | ||

| ⚫ | The Torwali people play music using the traditional South Asian instrument known as the ].<ref name="Torwali2016">{{cite web |last1=Torwali |first1=Zubair |title=Fading songs from the hills |url=https://www.thefridaytimes.com/fading-songs-from-the-hills/ |publisher=] |access-date=25 December 2020 |language= |

||

| ===Sources=== | |||

| Modern Torwali songs influenced by ] or ] music are known as ''phal''.<ref name="Torwali2016"/> | |||

| * {{citation |first=Fredrik |last=Barth |chapter=Torwali |title=Indus and Swat Kohistan: An ethnographic survey |publisher=Forenede Trykkerier |location=Oslo |year=1956 |url=https://archive.org/details/indusswatkohista0002bart |via=archive.org}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{citation |first=Abdur |last=Rehman |title=The Last Two Dynasties of the Sahis |publisher=Australian National University |year=1976 |url=https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/11229/1/Rehman_A_1976.pdf}} | |||

| * {{citation |first=Aurel |last=Stein |title=An Archaeological Tour in Upper Swat and Adjacent Hill Tracts |series=Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India |publisher=Government of India, Central Publication Branch |year=1930 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.35509}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ⚫ | {{reflist}} | ||

| {{Ethnic groups in Pakistan}} | {{Ethnic groups in Pakistan}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Torwali People}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Torwali People}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 17:31, 21 September 2024

Pakistani ethnic groupEthnic group

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Swat | |

| Languages | |

| Torwali | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Indo-Aryan peoples |

The Torwali people are an Indo-Aryan ethnolinguistic group located in the Swat district of Pakistan. The Torwali people have a culture that values the telling of folktales and music that is played using the sitar. They speak an Indo-Aryan language called Torwali.

Description

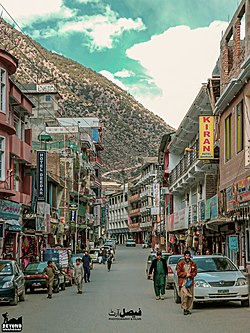

The Torwalis inhabit the Swat River valley between Laikot (a little south of Kalam) down to and including the village of Bahrein (60 km north of Mingora). The Torwalis live in compact villages of up to 600 houses, mainly on the west bank of the Swat River. Fredrik Barth estimated that they constituted about 2000 households in all in 1956. All the Torwalis he met were bilingual, speaking Pashto and Torwali.

History

The Torwali people are believed to be among the earliest natives to the region of Swat. The Torwali language is the closest modern Indo-Aryan language still spoken today to Niya, a dialect of Gāndhārī, a Middle Indo-Aryan language spoken in the ancient region of Gandhara. The Torwalis were native to a more extensive area, such as towards Buner, from where they were expelled into mountainous tracts by successive aggressive migration by Pashtuns. They are referred by pashtuns as "Kohistanis", which was the name given by them to "All other Muhammadans of Indian descent in the Hindu Kush valleys".

By the 17th century, in the aftermath of Yusufzai Pashtun invasions in the region, most of the Torwalis had converted from Hinduism and Buddhism to Islam; however, the strand was mostly superficial and elements of traditional culture were still heavily practised.

Language

Main article: Torwali languageThe Torwali people speak the Torwali language, an Indo-Aryan language of the Dardic (Kohistani) subgroup; the language was first documented by colonial archaeologist Aurel Stein in around 1925, and the records were published by George Abraham Grierson as 'Torwali: An Account of a Dardic Language of the Swat Kohistan' in 1929.

It had approximately 102,000 speakers in 2016 and by 2017, eight schools with instruction in the Torwali language had been established for Torwali students. Before 2007, the language did not have a written tradition.

Culture

Unique to the Torwali people are traditional games, which were abandoned for more than six decades. A festival held in Bahrain known as Simam attempted to revive them in 2011. The Torwali people have a tradition of telling folktales.

Music

The Torwali people play music using the traditional South Asian instrument known as the sitar. Modern Torwali songs influenced by Urdu or Pashtu music are known as phal.

References

- ^ Torwali, Zubair (12 February 2016). "Fading songs from the hills". The Friday Times. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Shah, Danial (30 September 2013). "Torwali is a language". Himal Southasian. Retrieved 3 December 2020.

- Barth 1956, p. 69.

- Burrow, T. (1936). "The Dialectical Position of the Niya Prakrit". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London. 8 (2/3): 419–435. ISSN 1356-1898. JSTOR 608051.

... It might be going too far to say that Torwali is the direct lineal descendant of the Niya Prakrit, but there is no doubt that out of all the modern languages it shows the closest resemblance to it. A glance at the map in the Linguistic Survey of India shows that the area at present covered by "Kohistani" is the nearest to that area round Peshawar, where, as stated above, there is most reason to believe was the original home of the Niya Prakrit. That conclusion, which was reached for other reasons, is thus confirmed by the distribution of the modern dialects.

- Salomon, Richard (10 December 1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Biddulph, John (1880). Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh. Office of the superintendent of government printing. pp. 69–70.

...they must have once occupied some extensive valley like Boneyr, from whence they, like the rest, have been expelled and thrust up into the more mountainous tracts by the aggressive Afghans. By the Afghans they are called Kohistanis, a name given everywhere by Pathans to Mussulmans of Indic descent, living in the Hindoo Koosh Valleys.

- Barth 1956, p. 52. The Pathans call them, and all other Muhammadans of Indian descent in the Hindu Kush valleys, Kohistanis.

- Scerrato, Umberto (1983). "Labyrinths in the Wooden Mosques of North Pakistan. A Problematic Presence". East and West. 33 (1/4): 21–29. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29756645.

According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist O rgyan pa forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375). Islam finally established itself in Swāt only with the invasion of the Yusufzai in the 16th century, (Bellew, 1864, pp. 65-67; Raverty, 1878, p. 206); ... it must nevertheless have been an Islam superficially accepted by the local population, some of the ancient traditions still being very much alive: ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70).

- Bagnera, Alessandra (2006). "Preliminary Note on the Islamic Settlement of Udegram, Swat: The Islamic Graveyard (11th-13th century A.D.)". East and West. 56 (1/3): 205–228. ISSN 0012-8376. JSTOR 29757687.

- ^ Eberhard, David M.; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2020). "Torwali". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (23 ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- ^ Torwali, Zubair (18 February 2019). "Early Writing in Torwali in Pakistan". In Sherris, Ari; Peyton, Joy Kreeft (eds.). Teaching Writing to Children in Indigenous Languages : Instructional Practices from Global Contexts. Routledge. pp. 44–69. doi:10.4324/9781351049672-3. ISBN 978-1-351-04967-2. S2CID 187240076.

- Torwali, Zubair (12 February 2016). "Fading songs from the hills". The Friday Times. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

Sources

- Barth, Fredrik (1956), "Torwali", Indus and Swat Kohistan: An ethnographic survey, Oslo: Forenede Trykkerier – via archive.org

Further reading

- Rehman, Abdur (1976), The Last Two Dynasties of the Sahis (PDF), Australian National University

- Stein, Aurel (1930), An Archaeological Tour in Upper Swat and Adjacent Hill Tracts, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, Government of India, Central Publication Branch

| Ethnic groups in Pakistan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||