| Revision as of 09:48, 5 October 2007 edit81.209.83.254 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 09:51, 5 October 2007 edit undoRrburke (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers68,439 editsm Reverted 1 edit by 81.209.83.254 identified as vandalism to last revision by SieBot. using TWNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{otheruses3|Indo-European}} | |||

| い魔法の薬である。西欧諸国はすでに大量にこれを服用し、次の荒療治に移りつつある。政財官勢力・知識人・マスコミが総動員で、大量の「引締め」と「犠牲」の新薬を抵抗なく社会に飲みこませるため、前代未聞の協調的攻勢をかけている。 | |||

| {{Indo-European topics}} | |||

| EU委員会は、規制緩和と公営部門(通信・電気・鉄道・航空)開放を乱暴に推進することも忘れず、マーストリヒト条約、1999年1月1日の統一通貨導入のキャンペーン活動に走っている。加盟諸国の財政赤字の国内総生産(GDP)に対する比率は平均4.4%であるが、これを条約の要求する3%の水準に引き下げるための様々な対策が支援されている。 | |||

| The '''Indo-European languages''' comprise a ] of several hundred related ]s and ]s <ref>449 according to the 2005 ] estimate, about half (219) belonging to the ] sub-branch.</ref>, including most of the major languages of ], the northern ] (]), the ] (]), and much of ]. Indo-European (''Indo'' refers to the Indian subcontinent) has the largest numbers of speakers of the recognised families of languages in the world today, with its languages spoken by approximately three billion native speakers.<ref>the ] family of tongues has the second-largest number of speakers.</ref> | |||

| Of the ] contemporary languages in terms of speakers according to ], 12 are Indo-European: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ], accounting for over 1.6 billion native speakers. The ] form the largest sub-branch of Indo-European in terms of the number of native speakers as well as in terms of the number of individual languages.<ref>308 languages according to SIL; more than one billion speakers (see ]). Historically, also in terms of geographical spread (stretching from the ] to ]; c.f. ])</ref> | |||

| だが構造調整のショックを吸収するには経済成長予測はあまりぱっとせず、1996-97年の失業率は労働人口の11%、1800万人レベルにとどまる見込みである。EU委員会の予測では「失業率はドイツ・オーストリアなどではかなり増加し、フランス・ベルギー・ポルトガルでも悪化するだろう(4)」。サンテールEU委員長は「雇用促進のためのヨーロッパ信用協定」を提唱して、ストラスブールの欧州議会に、次いで6月14-15日のローマでの閣僚・経営者・労働組合三者会談に、さらに6月21-22日のフィレンツェ欧州理事会にかけた。雇用促進協定というよりも雇用抑止協定と言ったほうがよかろう。実質的に求められているのは労働条件、特に労働時間のフレキシビリティと、公的支出・課税の削減なのだから。 | |||

| == Classification == | |||

| 競争力に関するアドヴァイザリー・グループ内も同様の意見である。同グループは、イタリア元首相でイタリア銀行総裁のチアンピ氏が新内閣の蔵相に任命されるまで委員長を務め、多国籍企業の経営者・元閣僚・労働組合幹部をメンバーとし、雇用コスト、特に社会保障費の大幅な低減、賃金の引下げ、最低賃金の見直しを加えた「社会協定」と、労働者の地域間移動の増大、コスト・利益に関連する社会立法の見直しなどを提言している。こういった「社会協定」なるものが、大量解雇を「社会プラン」と称する経営者の真似しがたいユーモアの一変種でないとしたら、何を反社会協定と呼んだらよいと言うのか? | |||

| {{Infobox Language family | |||

| |name = Indo-European | |||

| |region = Before the fifteenth century, ], and ], ] and ]; today worldwide. | |||

| |familycolor = Indo-European | |||

| |family = One of the world's major ]; although some have ], none of these has received mainstream acceptance. | |||

| |proto-name = ] | |||

| |child1 = ] | |||

| |child2 = ] | |||

| |child3 = ] | |||

| |child4 = ] | |||

| |child5 = ] | |||

| |child6 = ] | |||

| |child7 = ] | |||

| |child8 = ] | |||

| |child9 = ] (including ]) | |||

| |child10 = ] | |||

| |child11 = ] | |||

| |iso2=ine | |||

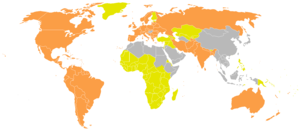

| |map = ]<br/><center><small>Orange: countries with a majority of speakers of IE languages<br />Yellow: countries with an IE minority language with official status</small></center> | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Hypothetical Indo-European subfamilies}} | |||

| The various subgroups of the Indo-European language family include (in historical order of their first attestation): | |||

| * ], earliest attested branch, from the ]; extinct, most notably including the language of the ]. | |||

| 構造調整策は、こうしてヨーロッパ全土でさりげなく実行に移されているのである。 | |||

| * ], descending from a common ancestor, ] | |||

| ** ], including ], attested from the mid ]. | |||

| ** ], attested from roughly ] in the form of ], and from 520 BC in the form of ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| * ], fragmentary records in ] from the ]; ]ic traditions date to the ]. (See ], ].) | |||

| * ], including ] and its descendants (the ]), attested from the ]. | |||

| * ], ] inscriptions date as early as the ]; ] texts from the ], see ]. | |||

| * ] (including ] and ]), earliest testimonies in ] inscriptions from around the ], earliest coherent texts in ], ], see ]. | |||

| * ], attested from the ]. | |||

| * ], extinct tongues of the ], extant in two dialects, attested from roughly the ]. | |||

| * ], believed by many Indo-Europeanists to derive from a common proto-language later than Proto-Indo-European, while skeptical Indo-Europeanists regard Baltic and Slavic as no more closely related than any other two branches of Indo-European. | |||

| ** ], attested from the ], earliest texts in ]. | |||

| ** ], attested from the ], and, for languages attested that late, they retain unusually many archaic features attributed to ]. | |||

| * ], attested from the ]; relations with Illyrian, Dacian, or Thracian proposed. | |||

| In addition to the classical ten branches listed above, several extinct and little-known languages have existed: | |||

| 国別の処方 | |||

| ドイツでは4月26日にコール首相の経済引締め計画が出され、主に高齢者・病人・失業者・被扶養家族への風当たりを強くして来年には500億マルクを節約しようとしているが、その一方、ぱっとしない景気と税収低下のために追加予算の削減ないしは付加価値税の15%から17%への引上げが予測される。コール首相は1月23日に労働組合・経営者と「雇用と競争力のための協定」を結んだが、その後これは一方的に破棄された。雇用維持と30万人の雇用創出とひきかえに、労働・賃金のフレキシビリティの増大、定年の後退と退職年金の下方修正、失業手当の削減、企業負担の税金(事業税・資本課税)の引下げが計画されている。蔵相は財政赤字制限立法による仕上げをはかっているが、ブンデスバンク総裁はまだ不充分と見なしている。 | |||

| イタリアでは、ディーニ前内閣の下で1993年に行われた物価スライド式賃上げ制廃止を皮切りに予算削減と年金制度の大改正が続き、「オリーヴの木」中道左派連立内閣も経済引締め政策を強化しようとしている。欧州経済通貨連合に何とか滑りこむために、プロディ首相は「引締め」と「さらなる犠牲」を約束した。1997-99年度の経済・財政計画案を待ちつつ、まずは教育・医療支出と公共サービスへの補助金をカットする修正予算案で財政赤字が制限される。他方、増税圧力は今後2年にわたって高いままと思われ、新たな民営化計画も発表もされた。 | |||

| * ] — possibly related to Messapian or Venetic; relation to Albanian also proposed. | |||

| スペインのアスナール保守内閣は、教育支出を含む支出の削減、公務員ポストの削減、企業への補助金の削減によって「予算調整政策をうまくやる」ことを考えている。民間企業・資産家に対する課税の大幅な引下げ、ピケ産業相による民営化・自由化・規制緩和計画も考えられている。 | |||

| * ] — close to Italic. | |||

| * ] — apparently grouped with Venetic. | |||

| * ] — not conclusively deciphered. | |||

| * ] — language of ancient ], possibly close to Greek, Thracian, or Armenian. | |||

| * ] — extinct language once spoken north of Macedon. | |||

| * ] — possibly close to Dacian. | |||

| * ] — possibly close to Thracian or to Albanian – or both. | |||

| * ] — related to Greek; some propose relationships to Illyrian, Thracian or Phrygian. | |||

| * ] — possibly not Indo-European; possibly close to or part of Celtic. | |||

| * ] — possibly related to (or part of) Celtic, or Ligurian, or Italic. | |||

| No doubt other Indo-European languages once existed which have now vanished without leaving a trace. | |||

| ベルギーのデハーネ首相は、経済引締め「合理化」政策、つまり財政支出・健康保険の削減、公共サービス補助金・公共投資・省庁予算カットによるドラスティックな財政赤字削減のための特別権限を、5月13日に議会から取りつけた。2月に行われたフランス語中等教育機関における3000人の雇用削減は未曾有のストを引き起こした(5)。 | |||

| A large majority of ] can be considered Indo-European, at least in content. Examples include | |||

| フランスのジュペ首相は、昨年冬の大規模な抗議運動(6)にもかかわらず、公営部門の解体計画をあきらめていない。社会の反対を封じこめる首相の統治能力にいらだつ市場の圧力により、規制緩和と 通信(フランステレコム)・エネルギー(フランス電気公社)・交通(国鉄・公団・エールフランス)・郵政・宇宙産業・軍事産業などの公共サービスの民営化が約束された。引き続き行われている国営企業の清算・民営化にあたっては公的資金が導入されて、資本が与えられ、負債は納税者の負担で穴埋めされた(7)。銀行・保険・製造業など、あらゆる産業部門が民営化の対象とされている。政府は、1993-94年に企業・資産家におよそ1兆フランの減税を行った後、1995年にはそれに見合った増税を行い、高所得者減税をちらつかせながら1997年度の引締め予算を準備している。 | |||

| * ] | |||

| 今年度は500億フラン近く、来年度には800億フランにのぼると見られる健康保険の財源も見つけなければなるまい。ジュペ保守政権は、昨年9月の公務員賃金凍結の発表の後、「肥大化」を非難される公務員への風当たりを強め、来年度には 2万から2万5000のポスト削減が行われる可能性がある。これには野党の一部メンバーも賛成しており、シャラス社会党上院議員は、「公務員にのみ我々の赤字の責任は押しつけられない(8)」としながらも、「利己主義の徹底的な排除」と「支出引締めの継続」を促すが、コストは高いが役に立たない上院を廃止することには取り組んでいない。 | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Membership of languages in the same language family is determined by the presence of '''shared retentions''', i.e., features of the proto-language (or reflexes of such features) that cannot be explained better by chance or borrowing (convergence). Membership in a branch/group/subgroup '''within''' a language family is determined by '''shared innovations''' which are presumed to have taken place in a common ancestor. For example, what makes Germanic languages "Germanic" is that large parts of the structures of all the languages so designated can be stated just once for all of them. In other words, they can be treated as an innovation that took place in Proto-Germanic, the source of all the Germanic languages. | |||

| スウェーデンでも構造調整計画がある。社会民主党政府は、傷病保険、失業・育児休暇手当を削減した後、退職年金、住宅援助、医療支出に手をつけることに決めた。 | |||

| A problem, however, is that shared innovations can be acquired by borrowing or other means. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be "areal" features. More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, since English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar innovations in Germanic and Baltic/Slavic that are far more likely to be areal features than traceable to a common proto-language, such as the uniform development of a '''high''' vowel (*''u'' in the case of Germanic, *''i'' in the case of Baltic and Slavic) before the PIE syllabic resonants *''ṛ,* ḷ, *ṃ, *ṇ'', unique to these two groups among IE languages. But legitimate uncertainty about whether shared innovations are areal features, coincidence, or inheritance from a common ancestor, leads to disagreement over the proper subdivisions of any large language family. Thus specialists have postulated the existence of such subfamilies (subgroups) as Germanic with Slavic, ] and ]. The vogue for such subgroups waxes and wanes (Italo-Celtic for example used to be an absolutely standard feature of the Indo-European landscape; nowadays it is little honored, in part because much of the striking evidence on the basis of which it was postulated has turned out to have been misinterpreted). | |||

| こういった構造調整の動きはイギリスには見られない。付け加えて言えば、原子力の民営化の他には、たいして調整するようなものは残っていないのだ。10個の良好状態の原子力発電所を、古いものについては高くつく維持費用は国家負担として、新品価格で売ることならできる。 | |||

| ] refers to the theory that Indo-European (sensu stricto, i.e. the proto-language of the Indo-European languages known before the discovery of Hittite), and Proto-Anatolian, split from a common proto-language called Proto-Indo-Hittite by its first theoretician, Edgar Sturtevant. Validation of such a theory would consist of identifying formal-functional structures that can be coherently reconstructed for both branches but which can only be traced to a formal-functional structure that is either (a) different from both or else (b) shows evidence of a very early, group-wide innovation. As an example of (a), it is obvious that the Indo-European perfect subsystem in the verbs is '''formally''' superimposable on the Hittite ''ḫi''-verb subsystem, but there is no match-up functionally, such that (as has been held) the functional source must have been unlike both Hittite and Indo-European. As an example of (b), the solidly-reconstructable Indo-European deictic pronoun paradigm whose nominatives singular are *''so, *sā'' (*seH₂), ''*tod'' has been compared to a collection of clause-marking particles in Hittite, the argument being that the coalescence of these particles into the familiar Indo-European paradigm was an innovation of that branch of Proto-Indo-Hittite. | |||

| 左右を問わずスペインやイタリアの新内閣は、他のヨーロッパ諸国同様、まず「国際金融界が納得がいくように」(アスナール首相)、国民に「さらなる犠牲」を強いながら「市場の信用を獲得・維持する」(プロディ首相)ことを望んでいる。 | |||

| === Satem and Centum languages === | |||

| 投資家というハゲタカたち | |||

| 投資家は、ヨーロッパ各国で日程にのぼる国営企業・公共サービス民営化の甘い蜜をむさぼり、リストラ、資本集中、TBO、新たな市場分割などの「朗報」に喜ぶ(9)。さもなくば、英米の業界用語でいう「ハゲタカ資金」(資本化された一般大衆の預金・退職金から成ることも多い)は、巨大な損害が納税者により穴埋め(今世紀最大の税金の無駄遣い)された後に銀行やディベロッパーが安値で買い取った各地の不良土地債権に群らがる。 | |||

| 常に「神経質で」「懸念して」「動揺して」いる市場の前に、政治家も癒着業者もひざまずく。市場は、いかがわしい、猫かぶりの、厚塗りの化粧が崩れた売春婦のように酔っぱらった目を世界に釘付け、強欲だが卑屈な若いトレーダーの群に取り巻かれている。精神を病んだトレーダーたちは、あらゆる悪いニュースにそわそわと高騰で応え(2600人の解雇の発表はフランスのムリネックス社の相場を20%上昇させた)、最近のアメリカのように、賃金引上げや雇用創出の見込みがわずかでもあると「何てことだ! 奴らが得するってことは、俺たちにはまずいリスクってことだ」と寒々と低落で応えるのだ。 | |||

| ]/]/] cultures).]] | |||

| 西欧では、フランス経済統計調査局の最近の報告に見られるように、国富の着実な増大の一方で、大多数の人々の購買力・社会保障は低下し、失業と生活不安が増加しているが、企業利益・資本所得・少数者の資産は膨れ上がっている(10)。第三世界が忍び寄っているのだろうか? | |||

| Many scholars classify the Indo-European sub-branches into a ] group and a ] group. This terminology comes from the different treatment of the three original ] rows. Satem languages lost the distinction between labiovelar and pure velar sounds, and at the same time ] the palatal velars. The centum languages, on the other hand, lost the distinction between palatal velars and pure velars. Geographically, the "eastern" languages belong in the Satem group: Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic (but not including Tocharian and Anatolian); and the "western" languages represent the Centum group: Germanic, Italic, and Celtic. The ] runs right between the Greek (Centum) and Armenian (Satem) languages (which a number of scholars regard as closely related), with Greek exhibiting some marginal Satem features. Some scholars think that some languages classify neither as Satem nor as Centum (Anatolian, Tocharian, and possibly Albanian). Note that the grouping does not imply a claim of ]: we do not need to postulate the existence of a "proto-Centum" or of a "proto-Satem". Areal contact among already distinct post-PIE languages (say, during the 3rd millennium BC) may have spread the sound changes involved. In any case, present-day specialists are rather less galvanized by the division than 19th cent. scholars were, partly because of the recognition that it is, after all, just one ] among the multitudes that criss-cross Indo-European linguistic geography. (Together with the recognition that the Centum Languages are no subgroup: as mentioned above, subgroups are defined by shared innovations, which the Satem languages definitely have, but the only thing that the "Centum Languages" have in common is staying put.) | |||

| 6月初めには、30万人のアメリカ人が生活保護の削減に抗議してワシントンでデモ行進を行った。「何もかも国家におんぶにだっこと信じている者たちとの名誉の戦いだ‥‥ 連中はあらゆる改革を妨げるために生活保護で暮らしている」というのが、20%の子供が貧困ライン以下、10%が赤貧という国、アメリカ(11)の共和党のコメントである。経済自由主義の別のモデル国であるイギリスでは、18歳の少年の就学率は、他のヨーロッパ諸国の5人に4人に対して2人に1人にすぎない。下院の調査によると、16歳以下の子供150万人が非合法で、しばしば危険な労働条件の下で就業しており、とりわけメージャー首相の地元選挙区では著しい(12)。 | |||

| === Suggested superfamilies === | |||

| フランス経済統計調査局の別の調査によると、生活不安は増大し、4分の1の人々が過去2年以内のうちに失業の経験があるという(13)。60万人の若者が職業斡旋所に通い、そのうち20%のみが仕事口を見つけ、いつ切られるかわからない無期限契約にサインした。その他の者の多くは、工場では「まっとうで正直な程つぶされる」と言う26歳の工員のように(14)臨時雇いのその日暮らしを何年間も強いられている。 | |||

| Some linguists propose that Indo-European languages form part of a hypothetical ] superfamily, and attempt to relate Indo-European to other language families, such as ], ], ], ], and ]. This theory remains controversial, like the similar ] theory of ], and the ] postulation of ]. There are no possible theoretical objections to the existence of such superfamilies; the difficulty comes in finding concrete evidence that transcends chance resemblance and wishful thinking. The main problem for all of them is that in historical linguistics the noise-to-signal ratio steadily worsens over time, and at great enough time-depths it becomes open to reasonable doubt that it can even be possible to tell what is signal and what is noise. | |||

| 6月15日の土曜日には、35万人と戦後ドイツ最大規模のデモがボンを行進した。デモを組織したドイツ労働総同盟(DGB)執行部の言葉を借りれば「ぞっとするカタログ」であるところのコール首相の経済引締め計画への反対デモである。「政府の行っていることは経済政策ではなくて、持たざる者のポケットから金を取って持てる者のポケットに入れているだけだ。(中略)経営者は利益をあげるほど横暴になり、雇用を削減し、労働コストの低減を求めている(15)」と参加者の一人はコメントしている。「私はフランス国旗をもってデモに来た。12月のフランスの運動は立派な前例で、サラリーマンが政府と経営者になすがままにさせてはおかないという警告だと思う(16)」と別の者が言う。大衆は、自分が首を吊られるための紐をおとなしく買いそうにはない。 | |||

| == History of the idea of Indo-European == | |||

| (1) 「国際化と自由化の時代の発展」(UNCTAD第9回会議事務総長報告、ジュネーヴ、1996年) | |||

| {{main|Indo-European studies}} | |||

| The first proposal of the possibility of common origin for some of these languages came from the ] linguist and scholar ] in ]. He discovered the similarity among ]s, and supposed the existence of a primitive common language which he called "'']''". He included in his hypothesis ], ], ], ], and ], later adding ], ] and ]. However, the suggestions of van Boxhorn did not become widely known and did not stimulate further research. | |||

| The hypothesis re-appeared in 1786 when ] first lectured on similarities between four of the oldest languages known in his time: ], ], ], and ]. Systematic comparison of these and other old languages conducted by ] supported this theory, and Bopp's ''Comparative Grammar'', appearing between ] and ] counts as the starting-point of ] as an academic discipline. | |||

| ==Historical evolution== | |||

| ===Sound changes=== | |||

| {{main | Indo-European sound laws}} | |||

| As the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system diverged as well, changing according to various ]s evidenced in the daughter-languages. Notable cases of such sound laws include ] in ], loss of prevocalic ''*p-'' in ], loss of prevocalic ''*s-'' in ], ] in ], as well as ] (discussed above). ] and ] may or may not have operated at the common Indo-European stage. | |||

| ===Indo-European expansion=== | |||

| The earliest attestations of Indo-European languages date to the early 2nd millennium BC. At that time, the languages were already diversified and widely distributed, so that "loss of contact" between the individual dialects is accepted to have taken place before 2500 BC.<ref>], ''Comparative Linguistics. Current Trends of Linguistics'', Den Haag (1972)</ref>. Competing scenarios for the early history of Indo-European are thus largely compatible for times after 2500 BC, even if they are incommensurable for the 4th millennium BC and earlier. The following timeline inserts the scenario suggested by the mainstream ] for the mid 5th to mid 3rd millennia (see below for competing hypotheses). | |||

| ] in the ] framework]] | |||

| * ]–4000: '''Early PIE'''. ], ] and ] cultures, ]. (The early presence of the horse at Sredny Stog has been discredited as decisive—genetic evidence does not supply a single origin for the domesticated horse.) | |||

| * ]–3500: The ] (prototypical ]-building) emerges in the steppe, and the ] in the northern ]. ] models postulate the separation of ] before this time. | |||

| * ]–3000: '''Middle PIE'''. The Yamna culture reaches its peak: it represents the classical reconstructed ], with ], early two-wheeled proto-chariots, predominantly practising ], but also with permanent settlements and ]s, subsisting on agriculture and fishing, along rivers. Contact of the Yamna culture with late ] cultures results in the "kurganized" ] and ] cultures. The ] shows the earliest evidence of the early ], and bronze weapons and artifacts enter Yamna territory. Probable early ]. | |||

| ] distribution]] | |||

| * ]–2500: '''Late PIE'''. The Yamna culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe. The ] extends from the ] to the ], corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, but still in loose contact and thus enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups (except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, already isolated from these processes). The Centum-Satem division has probably run its course, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active. | |||

| * ]–2000: The breakup into the proto-languages of the attested dialects has done its work. Speakers of ] live in the ], speakers of ] north of the Caspian in the ] culture. The Bronze Age reaches ] with the ], whose people probably use various Centum dialects. ] speakers (or alternatively, ] and ] communities in close contact) emerge in north-eastern Europe. The ] possibly correspond to proto-]. | |||

| ] distribution]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] and ] distribution]] | |||

| * ]–1500: Invention of the ], which leads to the split and rapid spread of ] and ] from the ] and the ] over much of ], Northern ], ] and Eastern ]. Proto-Anatolian splits into ] and ]. The pre-Proto-Celtic ] has an active metal industry (]). | |||

| * ]–1000: The ] develops (pre-)], and the (pre-)] ] and ] cultures emerge in Central Europe, introducing the ]. ] migration into the ]. Redaction of the '']'' and rise of the ] in the ]. Flourishing and decline of the ]. The ] gives way to the ]. | |||

| * ]–]: The ] spread over Central and Western Europe. Northern Europe enters the ], the formative phase of ]. ] initiates Greek literature and early ]. The Vedic civilization gives way to the ]. ] composes the ]s; rise of the ], replacing the ] and ]. The ] supplant the ] (]) in the Pontic steppe. ] succeed the ] culture. Separation of Proto-Italic into ] and ], and foundation of ]. Genesis of the ] and ] alphabets. A variety of ] have speakers in Southern Europe. The Anatolian languages suffer ]. | |||

| ==Proto-Indo-European== | |||

| {{main|Proto-Indo-European language}} | |||

| ===Location hypotheses=== | |||

| Scholars have dubbed the common ancestral (reconstructed) language ] (PIE). They disagree as to the original ] location (the so-called "]" or "original homeland") from where it originated. Mainstream opinion locates PIE in the ] in the ] (from ca. 4000 BC; see ]). The main competitor of this is the ] advanced by ], dating PIE to several millennia earlier, associating the spread of Indo-European languages with the ] spread of farming (see ]). A rapid divergence of the Romance, Celtic and Balto-Slavic languages around 6,500 years ago<ref>Gray and Atkinson (2003) ''Nature'' vol 426, pp436-438</ref> makes the two hypotheses compatible.<ref>Balter (2004) ''Science'' '''303''', pp1323-1326.</ref> | |||

| It should be noted that theories of the origin of Indo-European languages are not based on purely linguistic concepts. These theories are highly dependent on extra-linguistic factors, particularly interpretations of archaeological findings and the unattested meaning of words dating back as much as 3500 years or more before writing. The reference above to "mainstream" opinion concerning origins in the Pontic-Caspian steppes relies on such extra-linguistic conclusions. Since there is no direct way of knowing what language was spoken by a particular archaeological culture or how the meaning of words changed over thousands of years, theories about the location of the origin of Indo-European languages remain largely conjectural. | |||

| {{cquote|Early studies of Indo-European languages focused on those most familiar to the original European researchers: the Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic families. Affinities between these and the "Aryan" languages spoken in faraway India were noticed by European travelers as early as the 16th century. That they might all share a common ancestor was first proposed in 1786 by Sir William Jones, an English jurist and student of Eastern cultures. He thus launched what came to be known as the Indo-European hypothesis, which served as the principal stimulus to the founders of historical linguistics in the 19th century. <ref>Scientific American, March 1990, P.110</ref>}} | |||

| ==== Kurgan hypothesis ==== | |||

| {{main | Kurgan hypothesis}} | |||

| The Kurgan hypothesis was introduced by ] in ] in order to combine ] with ] in locating the origins of the ] (PIE) speaking peoples. She tentatively named the set of cultures in question "]" after the Russian term for their distinctive ]s and traced their diffusion into ]. | |||

| This hypothesis has had a significant impact on ]. Those scholars who follow Gimbutas identify a ''Kurgan'' or '']'' as reflecting an early ] ]ity which existed in the ] and ] from the ] to ] millennia BC. | |||

| While Gimbutas pointed primarily at the kurgan-ridden Pit Grave- or ] to be at the origin of all Indo-European migrations and Indo-Europeanization, recently there exists a tendency to push the date of origin further back in time. In a revised Kurgan hypothesis rather the kurgan-less ] has been proposed to be ancestral to all Indo-European languages instead, and the subsequently evolving Yamna culture to be related to the later satemization process<ref name=Kortlandt>Frederik Kortlandt-The spread of the Indo-Europeans, 2002,</ref>. | |||

| ==== Anatolian hypothesis ==== | |||

| {{main | Anatolian hypothesis}} | |||

| ] in ] suggested <ref> {{cite book | last = Renfrew | first = Colin | authorlink = Colin Renfrew | title = Archeology and Language | publisher = Jonathan Cape | year = 1987 | id = ISBN 0-521-38675-6 }} </ref> an association between the spread of Indo-European and the ], spreading peacefully into Europe from ] (Anatolia) from around ] with the advance of farming (''wave of advance''). Accordingly, all the inhabitants of ] would have spoken Indo-European tongues, and the Kurgan migrations would at best have replaced Indo-European dialects with other Indo-European dialects. | |||

| According to Renfrew <ref> {{cite book | last = Renfrew | first = Colin | year = 2003 | chapter = Time Depth, Convergence Theory, and Innovation in Proto-Indo-European | title = Languages in Prehistoric Europe | id = ISBN 3-8253-1449-9 }} </ref>, the spread of Indo-European proceeded from "Pre-Proto-Indo-European" in 6500 to Archaic PIE in 5000 BC, with the historical Indo-European families developing from 3000 BC from "Balkan PIE". | |||

| The main strength of the farming hypothesis lies in its linking of the spread of Indo-European languages with an archeologically known event that likely involved major population shifts: the spread of farming (though the validity of basing a linguistics theory on archeological evidence remains disputed). | |||

| While the Anatolian theory enjoyed brief support when first proposed, the linguistic community in general now rejects it. While the spread of farming undisputedly constituted an important event, most see no case to connect it with Indo-Europeans in particular, since terms for animal husbandry tend to have much better reconstructions than terms related to agriculture. | |||

| The timeframe of the Anatolian hypothesis has received support from a 2003 computer analysis in ]<ref>Gray, R. D. and Atkinson, Q. D. (2003) Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature, 426(6965), 435-439.</ref> The rate of change calculated in the analysis results in an original ] division at 6700 BCE, and a ] division at 5300 BCE, about two millennia too early for a Kurgan timeframe. | |||

| ==== Other hypotheses ==== | |||

| The ] of ] and ] in ] placed the Indo-European homeland on ] <ref> {{cite book | last = Gamkrelidze | first = Tamaz V. | coauthors = Vjacheslav V. Ivanov | title = Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans | publisher = Mouton de Gruyter | year = 1995 | id = ISBN 3-11-014728-9 }} </ref>, suggesting that ] stayed in the Indo-European cradle while other Indo-European languages left the homeland and migrated on a route that led them along the eastern coast of the ] to the steppe north of the Black Sea. Gamkrelidze and Ivanov also originated the ]. | |||

| An ] is sometimes advanced, mostly by Indian authors, who see the ] as the location of either Proto-Indo-European or of ]. | |||

| Various nationalistic European groups in the 19th and early 20th centuries espoused other theories, typically locating Proto-Indo-European in the respective authors' own countries. For example, a suggested location of the proto-language in Northern Europe became involved in justifying the view of the German people as "]". | |||

| Some people have pointed to the ], dating the genesis of the ] to ca. ], as a direct cause of Indo-European expansion.<ref>Ryan and Pitman 1998:208-213</ref> This event occurred in still clearly Neolithic times and happened rather too early to fit with Kurgan archaeology. One can still imagine it as an event in the remote past of the ], with the people living on the land now beneath the Sea of Azov as possible pre-Proto-Indo-Europeans. | |||

| A recent version of the hypothesis of European origin of PIE is the "]" proposed by Italian theorists, which derives Indo-European languages from the ] ] cultures, arguing for linguistic continuity from genetic continuity. | |||

| Recent linguistic studies present strong evidence that the Indo-European language group originates in ]. <ref>A History of Armenia by Vahan M. Kurkjian </ref> | |||

| == References == | |||

| ===Bibliography=== | |||

| *{{cite book | last = Mallory | first = J. P. | title = In Search of the Indo-Europeans | publisher = Thames and Hudson | year = 1989 | id = ISBN 0-500-27616-1}} | |||

| * ], ''A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European Languages'' (1861/62). | |||

| * {{cite book | last = Watkins | first = Calvert | title = The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots | publisher = Houghton Mifflin | year = 2000 | id = ISBN 0-618-08250-6 }} | |||

| === Notes === | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == External links == | |||

| === Databases === | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * at the LLOW-database | |||

| * at the ] | |||

| * Collection of IE scholarly materials | |||

| * A site of joint resource of Indo-European languages, history, archaeology and religion. | |||

| === Lexicon === | |||

| * , from the '']''. | |||

| * (by Andi Zeneli) | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Link FA|ast}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Revision as of 09:51, 5 October 2007

For other uses, see Indo-European.| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

Languages

|

| Philology |

Origins

|

|

Archaeology

Pontic Steppe Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies

Indo-Aryans Iranians East Asia Europe East Asia Europe Indo-Aryan Iranian |

Religion and mythology

Others

|

Indo-European studies

|

The Indo-European languages comprise a family of several hundred related languages and dialects , including most of the major languages of Europe, the northern Indian subcontinent (South Asia), the Iranian plateau (Southwest Asia), and much of Central Asia. Indo-European (Indo refers to the Indian subcontinent) has the largest numbers of speakers of the recognised families of languages in the world today, with its languages spoken by approximately three billion native speakers.

Of the top 20 contemporary languages in terms of speakers according to SIL Ethnologue, 12 are Indo-European: Spanish, English, Hindi, Portuguese, Bengali, Russian, German, Marathi, French, Italian, Punjabi and Urdu, accounting for over 1.6 billion native speakers. The Indo-Iranian languages form the largest sub-branch of Indo-European in terms of the number of native speakers as well as in terms of the number of individual languages.

Classification

| Indo-European | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Before the fifteenth century, Europe, and South, Central and Southwest Asia; today worldwide. |

| Linguistic classification | One of the world's major language families; although some have proposed links with other families, none of these has received mainstream acceptance. |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 / 5 | ine |

Yellow: countries with an IE minority language with official status | |

| Hypothetical Indo-European phylogenetic clades |

|---|

| Balkan |

| Other |

The various subgroups of the Indo-European language family include (in historical order of their first attestation):

- Anatolian languages, earliest attested branch, from the 18th century BC; extinct, most notably including the language of the Hittites.

- Indo-Iranian languages, descending from a common ancestor, Proto-Indo-Iranian

- Indo-Aryan languages, including Sanskrit, attested from the mid 2nd millennium BC.

- Iranian languages, attested from roughly 1000 BC in the form of Avestan, and from 520 BC in the form of Old Persian

- Dardic languages

- Nuristani languages

- Greek language, fragmentary records in Mycenaean from the 14th century BC; Homeric traditions date to the 8th century BC. (See Proto-Greek language, History of the Greek language.)

- Italic languages, including Latin and its descendants (the Romance languages), attested from the 7th century BC.

- Celtic languages, Gaulish inscriptions date as early as the 6th century BC; Old Irish texts from the 6th century AD, see Proto-Celtic language.

- Germanic languages (including Old English and English), earliest testimonies in runic inscriptions from around the 2nd century, earliest coherent texts in Gothic, 4th century, see Proto-Germanic language.

- Armenian language, attested from the 5th century.

- Tocharian languages, extinct tongues of the Tocharians, extant in two dialects, attested from roughly the 6th century.

- Balto-Slavic languages, believed by many Indo-Europeanists to derive from a common proto-language later than Proto-Indo-European, while skeptical Indo-Europeanists regard Baltic and Slavic as no more closely related than any other two branches of Indo-European.

- Slavic languages, attested from the 9th century, earliest texts in Old Church Slavonic.

- Baltic languages, attested from the 14th century, and, for languages attested that late, they retain unusually many archaic features attributed to Proto-Indo-European.

- Albanian language, attested from the 15th century; relations with Illyrian, Dacian, or Thracian proposed.

In addition to the classical ten branches listed above, several extinct and little-known languages have existed:

- Illyrian languages — possibly related to Messapian or Venetic; relation to Albanian also proposed.

- Venetic language — close to Italic.

- Liburnian language — apparently grouped with Venetic.

- Messapian language — not conclusively deciphered.

- Phrygian language — language of ancient Phrygia, possibly close to Greek, Thracian, or Armenian.

- Paionian language — extinct language once spoken north of Macedon.

- Thracian language — possibly close to Dacian.

- Dacian language — possibly close to Thracian or to Albanian – or both.

- Ancient Macedonian language — related to Greek; some propose relationships to Illyrian, Thracian or Phrygian.

- Ligurian language — possibly not Indo-European; possibly close to or part of Celtic.

- Lusitanian language — possibly related to (or part of) Celtic, or Ligurian, or Italic.

No doubt other Indo-European languages once existed which have now vanished without leaving a trace.

A large majority of auxiliary languages can be considered Indo-European, at least in content. Examples include

Membership of languages in the same language family is determined by the presence of shared retentions, i.e., features of the proto-language (or reflexes of such features) that cannot be explained better by chance or borrowing (convergence). Membership in a branch/group/subgroup within a language family is determined by shared innovations which are presumed to have taken place in a common ancestor. For example, what makes Germanic languages "Germanic" is that large parts of the structures of all the languages so designated can be stated just once for all of them. In other words, they can be treated as an innovation that took place in Proto-Germanic, the source of all the Germanic languages.

A problem, however, is that shared innovations can be acquired by borrowing or other means. It has been asserted, for example, that many of the more striking features shared by Italic languages (Latin, Oscan, Umbrian, etc.) might well be "areal" features. More certainly, very similar-looking alterations in the systems of long vowels in the West Germanic languages greatly postdate any possible notion of a proto-language innovation (and cannot readily be regarded as "areal", either, since English and continental West Germanic were not a linguistic area). In a similar vein, there are many similar innovations in Germanic and Baltic/Slavic that are far more likely to be areal features than traceable to a common proto-language, such as the uniform development of a high vowel (*u in the case of Germanic, *i in the case of Baltic and Slavic) before the PIE syllabic resonants *ṛ,* ḷ, *ṃ, *ṇ, unique to these two groups among IE languages. But legitimate uncertainty about whether shared innovations are areal features, coincidence, or inheritance from a common ancestor, leads to disagreement over the proper subdivisions of any large language family. Thus specialists have postulated the existence of such subfamilies (subgroups) as Germanic with Slavic, Italo-Celtic and Graeco-Aryan. The vogue for such subgroups waxes and wanes (Italo-Celtic for example used to be an absolutely standard feature of the Indo-European landscape; nowadays it is little honored, in part because much of the striking evidence on the basis of which it was postulated has turned out to have been misinterpreted).

Indo-Hittite refers to the theory that Indo-European (sensu stricto, i.e. the proto-language of the Indo-European languages known before the discovery of Hittite), and Proto-Anatolian, split from a common proto-language called Proto-Indo-Hittite by its first theoretician, Edgar Sturtevant. Validation of such a theory would consist of identifying formal-functional structures that can be coherently reconstructed for both branches but which can only be traced to a formal-functional structure that is either (a) different from both or else (b) shows evidence of a very early, group-wide innovation. As an example of (a), it is obvious that the Indo-European perfect subsystem in the verbs is formally superimposable on the Hittite ḫi-verb subsystem, but there is no match-up functionally, such that (as has been held) the functional source must have been unlike both Hittite and Indo-European. As an example of (b), the solidly-reconstructable Indo-European deictic pronoun paradigm whose nominatives singular are *so, *sā (*seH₂), *tod has been compared to a collection of clause-marking particles in Hittite, the argument being that the coalescence of these particles into the familiar Indo-European paradigm was an innovation of that branch of Proto-Indo-Hittite.

Satem and Centum languages

Many scholars classify the Indo-European sub-branches into a Satem group and a Centum group. This terminology comes from the different treatment of the three original velar rows. Satem languages lost the distinction between labiovelar and pure velar sounds, and at the same time assibilated the palatal velars. The centum languages, on the other hand, lost the distinction between palatal velars and pure velars. Geographically, the "eastern" languages belong in the Satem group: Indo-Iranian and Balto-Slavic (but not including Tocharian and Anatolian); and the "western" languages represent the Centum group: Germanic, Italic, and Celtic. The Satem-Centum isogloss runs right between the Greek (Centum) and Armenian (Satem) languages (which a number of scholars regard as closely related), with Greek exhibiting some marginal Satem features. Some scholars think that some languages classify neither as Satem nor as Centum (Anatolian, Tocharian, and possibly Albanian). Note that the grouping does not imply a claim of monophyly: we do not need to postulate the existence of a "proto-Centum" or of a "proto-Satem". Areal contact among already distinct post-PIE languages (say, during the 3rd millennium BC) may have spread the sound changes involved. In any case, present-day specialists are rather less galvanized by the division than 19th cent. scholars were, partly because of the recognition that it is, after all, just one isogloss among the multitudes that criss-cross Indo-European linguistic geography. (Together with the recognition that the Centum Languages are no subgroup: as mentioned above, subgroups are defined by shared innovations, which the Satem languages definitely have, but the only thing that the "Centum Languages" have in common is staying put.)

Suggested superfamilies

Some linguists propose that Indo-European languages form part of a hypothetical Nostratic language superfamily, and attempt to relate Indo-European to other language families, such as South Caucasian languages, Altaic languages, Uralic languages, Dravidian languages, and Afro-Asiatic languages. This theory remains controversial, like the similar Eurasiatic theory of Joseph Greenberg, and the Proto-Pontic postulation of John Colarusso. There are no possible theoretical objections to the existence of such superfamilies; the difficulty comes in finding concrete evidence that transcends chance resemblance and wishful thinking. The main problem for all of them is that in historical linguistics the noise-to-signal ratio steadily worsens over time, and at great enough time-depths it becomes open to reasonable doubt that it can even be possible to tell what is signal and what is noise.

History of the idea of Indo-European

Main article: Indo-European studiesThe first proposal of the possibility of common origin for some of these languages came from the Dutch linguist and scholar Marcus Zuerius van Boxhorn in 1647. He discovered the similarity among Indo-European languages, and supposed the existence of a primitive common language which he called "Scythian". He included in his hypothesis Dutch, Greek, Latin, Persian, and German, later adding Slavic, Celtic and Baltic languages. However, the suggestions of van Boxhorn did not become widely known and did not stimulate further research.

The hypothesis re-appeared in 1786 when Sir William Jones first lectured on similarities between four of the oldest languages known in his time: Latin, Greek, Sanskrit, and Persian. Systematic comparison of these and other old languages conducted by Franz Bopp supported this theory, and Bopp's Comparative Grammar, appearing between 1833 and 1852 counts as the starting-point of Indo-European studies as an academic discipline.

Historical evolution

Sound changes

Main article: Indo-European sound lawsAs the Proto-Indo-European language broke up, its sound system diverged as well, changing according to various sound laws evidenced in the daughter-languages. Notable cases of such sound laws include Grimm's law in Proto-Germanic, loss of prevocalic *p- in Proto-Celtic, loss of prevocalic *s- in Proto-Greek, Brugmann's law in Proto-Indo-Iranian, as well as satemization (discussed above). Grassmann's law and Bartholomae's law may or may not have operated at the common Indo-European stage.

Indo-European expansion

The earliest attestations of Indo-European languages date to the early 2nd millennium BC. At that time, the languages were already diversified and widely distributed, so that "loss of contact" between the individual dialects is accepted to have taken place before 2500 BC.. Competing scenarios for the early history of Indo-European are thus largely compatible for times after 2500 BC, even if they are incommensurable for the 4th millennium BC and earlier. The following timeline inserts the scenario suggested by the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis for the mid 5th to mid 3rd millennia (see below for competing hypotheses).

- 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper-Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse. (The early presence of the horse at Sredny Stog has been discredited as decisive—genetic evidence does not supply a single origin for the domesticated horse.)

- 4000–3500: The Yamna culture (prototypical kurgan-building) emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Yamna culture reaches its peak: it represents the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society, with stone idols, early two-wheeled proto-chariots, predominantly practising animal husbandry, but also with permanent settlements and hillforts, subsisting on agriculture and fishing, along rivers. Contact of the Yamna culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures. The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the early Bronze Age, and bronze weapons and artifacts enter Yamna territory. Probable early Satemization.

- 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Yamna culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe. The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, but still in loose contact and thus enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups (except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, already isolated from these processes). The Centum-Satem division has probably run its course, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

- 2500–2000: The breakup into the proto-languages of the attested dialects has done its work. Speakers of Proto-Greek live in the Balkans, speakers of Proto-Indo-Iranian north of the Caspian in the Sintashta-Petrovka culture. The Bronze Age reaches Central Europe with the Beaker culture, whose people probably use various Centum dialects. Proto-Balto-Slavic speakers (or alternatively, Proto-Slavic and Proto-Baltic communities in close contact) emerge in north-eastern Europe. The Tarim mummies possibly correspond to proto-Tocharians.

- 2000–1500: Invention of the chariot, which leads to the split and rapid spread of Iranian and Indo-Aryan from the Andronovo culture and the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex over much of Central Asia, Northern India, Iran and Eastern Anatolia. Proto-Anatolian splits into Hittite and Luwian. The pre-Proto-Celtic Unetice culture has an active metal industry (Nebra skydisk).

- 1500–1000: The Nordic Bronze Age develops (pre-)Proto-Germanic, and the (pre-)Proto-Celtic Urnfield and Hallstatt cultures emerge in Central Europe, introducing the Iron Age. Proto-Italic migration into the Italian peninsula. Redaction of the Rigveda and rise of the Vedic civilization in the Punjab. Flourishing and decline of the Hittite Empire. The Mycenaean civilization gives way to the Greek Dark Ages.

- 1000 BC–500 BC: The Celtic languages spread over Central and Western Europe. Northern Europe enters the Pre-Roman Iron Age, the formative phase of Proto-Germanic. Homer initiates Greek literature and early Classical Antiquity. The Vedic civilization gives way to the Mahajanapadas. Zoroaster composes the Gathas; rise of the Achaemenid Empire, replacing the Elamites and Babylonia. The Scythians supplant the Cimmerians (Srubna culture) in the Pontic steppe. Armenians succeed the Urartu culture. Separation of Proto-Italic into Osco-Umbrian and Latin-Faliscan, and foundation of Rome. Genesis of the Greek and Old Italic alphabets. A variety of Paleo-Balkan languages have speakers in Southern Europe. The Anatolian languages suffer extinction.

Proto-Indo-European

Main article: Proto-Indo-European languageLocation hypotheses

Scholars have dubbed the common ancestral (reconstructed) language Proto-Indo-European (PIE). They disagree as to the original geographic location (the so-called "Urheimat" or "original homeland") from where it originated. Mainstream opinion locates PIE in the Pontic-Caspian steppe in the Chalcolithic (from ca. 4000 BC; see Kurgan hypothesis). The main competitor of this is the Anatolian hypothesis advanced by Colin Renfrew, dating PIE to several millennia earlier, associating the spread of Indo-European languages with the Neolithic spread of farming (see Indo-Hittite). A rapid divergence of the Romance, Celtic and Balto-Slavic languages around 6,500 years ago makes the two hypotheses compatible.

It should be noted that theories of the origin of Indo-European languages are not based on purely linguistic concepts. These theories are highly dependent on extra-linguistic factors, particularly interpretations of archaeological findings and the unattested meaning of words dating back as much as 3500 years or more before writing. The reference above to "mainstream" opinion concerning origins in the Pontic-Caspian steppes relies on such extra-linguistic conclusions. Since there is no direct way of knowing what language was spoken by a particular archaeological culture or how the meaning of words changed over thousands of years, theories about the location of the origin of Indo-European languages remain largely conjectural.

Early studies of Indo-European languages focused on those most familiar to the original European researchers: the Italic, Celtic, Germanic, Baltic and Slavic families. Affinities between these and the "Aryan" languages spoken in faraway India were noticed by European travelers as early as the 16th century. That they might all share a common ancestor was first proposed in 1786 by Sir William Jones, an English jurist and student of Eastern cultures. He thus launched what came to be known as the Indo-European hypothesis, which served as the principal stimulus to the founders of historical linguistics in the 19th century.

Kurgan hypothesis

Main article: Kurgan hypothesisThe Kurgan hypothesis was introduced by Marija Gimbutas in 1956 in order to combine archaeology with linguistics in locating the origins of the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) speaking peoples. She tentatively named the set of cultures in question "Kurgan" after the Russian term for their distinctive burial mounds and traced their diffusion into Europe.

This hypothesis has had a significant impact on Indo-European research. Those scholars who follow Gimbutas identify a Kurgan or Pit Grave culture as reflecting an early Proto-Indo-European ethnicity which existed in the Pontic steppe and southeastern Europe from the fifth to third millennia BC.

While Gimbutas pointed primarily at the kurgan-ridden Pit Grave- or Yamna culture to be at the origin of all Indo-European migrations and Indo-Europeanization, recently there exists a tendency to push the date of origin further back in time. In a revised Kurgan hypothesis rather the kurgan-less Sredny Stog culture has been proposed to be ancestral to all Indo-European languages instead, and the subsequently evolving Yamna culture to be related to the later satemization process.

Anatolian hypothesis

Main article: Anatolian hypothesisColin Renfrew in 1987 suggested an association between the spread of Indo-European and the Neolithic revolution, spreading peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor (Anatolia) from around 7000 BC with the advance of farming (wave of advance). Accordingly, all the inhabitants of Neolithic Europe would have spoken Indo-European tongues, and the Kurgan migrations would at best have replaced Indo-European dialects with other Indo-European dialects.

According to Renfrew , the spread of Indo-European proceeded from "Pre-Proto-Indo-European" in 6500 to Archaic PIE in 5000 BC, with the historical Indo-European families developing from 3000 BC from "Balkan PIE".

The main strength of the farming hypothesis lies in its linking of the spread of Indo-European languages with an archeologically known event that likely involved major population shifts: the spread of farming (though the validity of basing a linguistics theory on archeological evidence remains disputed).

While the Anatolian theory enjoyed brief support when first proposed, the linguistic community in general now rejects it. While the spread of farming undisputedly constituted an important event, most see no case to connect it with Indo-Europeans in particular, since terms for animal husbandry tend to have much better reconstructions than terms related to agriculture.

The timeframe of the Anatolian hypothesis has received support from a 2003 computer analysis in glottochronology The rate of change calculated in the analysis results in an original Indo-Hittite division at 6700 BCE, and a Graeco-Aryan division at 5300 BCE, about two millennia too early for a Kurgan timeframe.

Other hypotheses

The Armenian hypothesis of Tamaz Gamq'relidze and Vyacheslav V. Ivanov in 1984 placed the Indo-European homeland on Lake Urmia , suggesting that Armenian stayed in the Indo-European cradle while other Indo-European languages left the homeland and migrated on a route that led them along the eastern coast of the Caspian Sea to the steppe north of the Black Sea. Gamkrelidze and Ivanov also originated the Glottalic theory.

An Out of India theory is sometimes advanced, mostly by Indian authors, who see the Indus Valley Civilization as the location of either Proto-Indo-European or of Proto-Indo-Iranian.

Various nationalistic European groups in the 19th and early 20th centuries espoused other theories, typically locating Proto-Indo-European in the respective authors' own countries. For example, a suggested location of the proto-language in Northern Europe became involved in justifying the view of the German people as "Aryan".

Some people have pointed to the Black Sea deluge theory, dating the genesis of the Sea of Azov to ca. 5600 BC, as a direct cause of Indo-European expansion. This event occurred in still clearly Neolithic times and happened rather too early to fit with Kurgan archaeology. One can still imagine it as an event in the remote past of the Sredny Stog culture, with the people living on the land now beneath the Sea of Azov as possible pre-Proto-Indo-Europeans.

A recent version of the hypothesis of European origin of PIE is the "Paleolithic Continuity Theory" proposed by Italian theorists, which derives Indo-European languages from the Proto-Indo-European Paleolithic cultures, arguing for linguistic continuity from genetic continuity.

Recent linguistic studies present strong evidence that the Indo-European language group originates in Anatolia.

References

Bibliography

- Mallory, J. P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- August Schleicher, A Compendium of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-European Languages (1861/62).

- Watkins, Calvert (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of Indo-European Roots. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-08250-6.

Notes

- 449 according to the 2005 SIL estimate, about half (219) belonging to the Indo-Aryan sub-branch.

- the Sino-Tibetan family of tongues has the second-largest number of speakers.

- 308 languages according to SIL; more than one billion speakers (see List of languages by number of native speakers). Historically, also in terms of geographical spread (stretching from the Caucasus to South Asia; c.f. Scythia)

- Oswald Szemerényi, Comparative Linguistics. Current Trends of Linguistics, Den Haag (1972)

- Gray and Atkinson (2003) Nature vol 426, pp436-438

- Balter (2004) Science 303, pp1323-1326.

- Scientific American, March 1990, P.110

- Frederik Kortlandt-The spread of the Indo-Europeans, 2002,

- Renfrew, Colin (1987). Archeology and Language. Jonathan Cape. ISBN 0-521-38675-6.

- Renfrew, Colin (2003). "Time Depth, Convergence Theory, and Innovation in Proto-Indo-European". Languages in Prehistoric Europe. ISBN 3-8253-1449-9.

- Gray, R. D. and Atkinson, Q. D. (2003) Language-tree divergence times support the Anatolian theory of Indo-European origin. Nature, 426(6965), 435-439.

- Gamkrelidze, Tamaz V. (1995). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 3-11-014728-9.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Ryan and Pitman 1998:208-213

- A History of Armenia by Vahan M. Kurkjian

See also

- Indo-European copula

- Indo-European sound laws

- Indo-European studies

- Language family

- List of common Indo-European roots

- List of Indo-European languages

- Proto-Indo-European language

External links

Databases

- The Indo-European Database(Indo-European Etymological Dictionary (IEED))

- IE language family overview (SIL)

- Indo-European at the LLOW-database

- Indo-European Documentation Center at the University of Texas at Austin

- TITUS(English Startpage) Collection of IE scholarly materials

- The Indo-European Database A site of joint resource of Indo-European languages, history, archaeology and religion.

Lexicon

- Indo-European Roots, from the American Heritage Dictionary.

- Indo-European Root/lemmas (by Andi Zeneli)