| Revision as of 17:29, 6 February 2010 editNovickas (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers9,221 edits + background i.e. how long the treaty-established borders lasted← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:34, 6 February 2010 edit undoNovickas (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers9,221 edits /* Consequences - "dreams" is unencylopedic language. Separate sentencesNext edit → | ||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

| ==Consequences== | ==Consequences== | ||

| ]'s plans to create a Polish-led federation of ]an countries (]) were thwarted by this treaty, as much of the territory proposed for the federation had been claimed by the Soviets. Polish-Lithuanian relations deteriorated as well as a result of Poland's annexation of the city of ], which the Lithuanians claimed as their capital. | |||

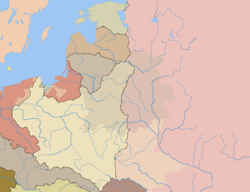

| ] border of the ] marked]] | ] border of the ] marked]] | ||

Revision as of 17:34, 6 February 2010

| Borders of Poland | |

|---|---|

the Baltic states in the 20th century |

|---|

Post World War I

|

| World War II |

Post World War II

|

Areas

|

Demarcation lines

|

| Adjacent countries |

The Peace of Riga, also known as the Treaty of Riga; (Template:Lang-ru (Rízhsky Mírny dogovór), Template:Lang-lv and Template:Lang-pl) was signed in Riga on 18 March 1921, between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia and Soviet Ukraine on the other. The treaty ended the Polish-Soviet War.

The Soviet-Polish borders established by the treaty were stable until World War II. They were redrawn during the Yalta Conference and Potsdam Conference.

Background

Further information: Polish-Soviet WarAmidst the Russian Civil War the Poles were eager to regain all the territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth from their historical enemy, Russia. Meanwhile, the Soviets tried to export the revolution to the West, by force if necessary. If the Soviets had occupied Poland they would have been in a position to come to the aid of German Communists, and possibly ensure the success of a Soviet revolution in Germany. The historian J.F.C. Fuller described the Battle of Warsaw as one of the most significant battles in history. After that military setbacks that followed a defeat in that battle, the Soviet side was eager to begin peace treaty negotiations.

Making of Treaty

Peace talks were started on August 17, 1920, in Minsk, but as the Polish counter-offensive drew near, the talks were moved to Riga, and resumed on September 21. In September in Riga the Soviet side made two offers: on September 21 and 28th. The Polish delegation made a counteroffer on the 2nd of October. On the 5th the Soviets offered amendments to the Polish offer, which Poland accepted. An armistice was signed on October 12. and went into effect on October 18.

The chief negotiators were Jan Dąbski for Poland, and Adolph Joffe for RSFSR.

Poland also was to receive monetary compensation (30 million rubles in gold) for its economic input into the Russian Empire during the times of partitions of Poland. Russia was also to surrender works of art and other Polish national treasure acquired from Polish territories after 1772 (like the Załuski Library). Both sides renounced claims to war compensation.

Treaty aftermath

The Treaty of Riga was controversial from the very beginning. Many argued that much of what Poland had gained during the Polish-Soviet war was lost in the peace negotiations, which were characterized by many as short-sighted and narrow-minded. By 1921, Piłsudski was no longer the head of state, and only participated as an observer during the Riga negotiations, which he called an act of cowardice.

Due to their military setbacks, the Bolsheviks offered the Polish peace delegation substantial territorial concessions in the contested border areas. However, to many observers it looked like the Polish side was conducting the Riga talks as if Poland had lost the war. In fact, a special parliamentary delegation consisting of six members of the Sejm held a vote on whether to accept the Soviets' far-reaching concessions, which would leave Minsk on the Polish side of the border. Pressured by the national democrat Stanisław Grabski, the 100 km of extra territory were rejected, a victory for the nationalist doctrine and a stark defeat for Piłsudksi's federalism, for the national democrats envisioned a unitary Polish state with no more than 1/3 minorities within its borders, a prerequisite for any successful Polonization attempts in their eyes. The National Democrats were also motivated by internal political concerns. While the National Democrats' base of support was among Poles in central and western Poland, many of the hundreds of thousands of Poles left by them to live under Soviet rule were supporters of Pilsudski. The elections within the territories of the Treaty of Riga were evenly split. If the Poles and eastern Slavs in the territories given to the Soviet Union has remained in Poland, the National Democrats would have never won an election. by the Public opinion in Poland also demanded an end to the hostilities; both sides were also under pressure from the League of Nations.

On the other hand, the negotiations for a peace treaty dragged on for months due to Soviet reluctance to sign. However, Soviet leadership faced increased internal unrest. Between February 23 and March 17 a sailors’ revolt occurred in Kronstadt, which was suppressed; peasants were also rising up against Soviet authorities, who collected grain to feed the army and starving consumer regions. In view of this situation, Lenin ordered the Soviet plenipotentiaries to secure a peace treaty.

Eventually both sides agreed to sign the Peace of Riga on March 18, 1921, splitting the disputed territories in Belarus and Ukraine, between Poland and Russia.

The Ukrainian People's Republic led by Symon Petliura had been allied with Poland by Treaty of Warsaw, but in Riga, Poland went back on this treaty. Piłsudski felt the agreement was a shameless and short-sighted political calculation. Allegedly, having walked out of the room, he told the Ukrainians waiting there for the results of the Riga Conference: "Gentlemen, I deeply apologize to you". The new treaty violated Poland's military alliance with the UPR, which had explicitly prohibited a separate peace. It also worsened relations between Poland and its Ukrainian minority, who felt Ukraine had been betrayed by its Polish ally, a feeling that would be exploited by Ukrainian nationalists and result in the growing tensions and eventual violence in the 1930s and 1940s. By the end of 1921, the majority of Poland-allied Ukrainian, Belarusian and White Russian forces had either crossed the Polish border and laid down their arms or had been annihilated by Soviet forces.

Consequences

Józef Piłsudski's plans to create a Polish-led federation of Eastern European countries (Międzymorze) were thwarted by this treaty, as much of the territory proposed for the federation had been claimed by the Soviets. Polish-Lithuanian relations deteriorated as well as a result of Poland's annexation of the city of Wilno, which the Lithuanians claimed as their capital.

Lenin also considered the treaty unsatisfactory. He had to temporarily give up his plans for exporting the revolution West.

On the other hand, the Treaty of Riga led to the stabilization of the Soviet-Polish conflict. The new Polish state surrendered to Russia and Ukraine most of the land it had previously lost in the 1st and 2nd partitions. These territories had a sizeable Polish minority (less than 1 million) especially around Słuck and Żytomierz. Soviet authorities had later repressed those Poles — starting with confiscation of property (land, forests), religious persecution (bishop Jan Cieplak, 1923). Most Poles left in the Soviet Union by the Treat of Riga would be deported to Siberia and Kazakhstan in the 1930's.

Notes and references

Footnotes

- ^ THE REBIRTH OF POLAND. University of Kansas, lecture notes by professor Anna M. Cienciala, 2004. Last accessed on 2 June 2006.

- Geoff Eley, "Forging Democracy"

- Norman Davies (2003). White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919–20. Pimlico. p. 399. ISBN 0-7126-0694-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|chapterurl=(help) (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.) - ^ Timothy Snyder. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations. New Haven: Yale University Press, pg. 68.

- In fact Piłsudski did apologize the Ukrainian officers on a completely different occasion. His words, commonly associated with the Riga conference, were said on May 15, 1921, during Piłsudski's visit to the internment camp at Szczypiorno. The context however was clearly the same.

- Template:Pl icon Jerzy Surdykowski (2001). "Ja was przepraszam panowie, czyli Polska a Ukraina i inni wpóltowarzysze niedoli". Duch Rzeczypospolitej. Warsaw: Wydawictwo Naukowe PWN. p. 335. ISBN 83-01-13403-8.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - Template:Pl icon Jan Jacek Bruski (2002). "Sojusznik Petlura". Wprost. 1029 (2002-08-18). ISSN 0209-1747. Retrieved 2006-09-28.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)

Notations

- Davies, Norman, White Eagle, Red Star: the Polish-Soviet War, 1919-20, Pimlico, 2003, ISBN 0-7126-0694-7. (First edition: New York, St. Martin's Press, inc., 1972.)

- Traktat ryski 1921 roku po 75 latach, Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Mikołaja Kopernika, Toruń 1998, ISBN 83-231-0974-5 (Chapter summaries in English)

See also

External links

Polish

| Polish truces and peace treaties | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kingdom of Poland | |||||||||||

| Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth |

| ||||||||||

| Second Polish Republic | |||||||||||