| Revision as of 11:46, 30 November 2012 editJudgementSummary (talk | contribs)309 edits →Objections Due to Quantum Mechanics← Previous edit | Revision as of 11:52, 30 November 2012 edit undoJudgementSummary (talk | contribs)309 edits →OppositionNext edit → | ||

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

| ==Opposition== | ==Opposition== | ||

| Suggested arguments against the possibility of the universe being precisely predictable via the laws of science include: the concept of ] acting through the agency of a ] not strictly governed by the laws of physics; the second law of ] (the total ] of any isolated thermodynamic system tends to increase over time, approaching a maximum value); the axiomatic foundation of mathematics which underlies scientific inquiry;] with its mathematical description of the wave function and the uncertainty principle; and most recently modern ] |

Suggested arguments against the possibility of the universe being precisely predictable via the laws of science include: the concept of ] acting through the agency of a ] not strictly governed by the laws of physics; the second law of ] (the total ] of any isolated thermodynamic system tends to increase over time, approaching a maximum value); the axiomatic foundation of mathematics which underlies scientific inquiry;] with its mathematical description of the wave function and the uncertainty principle; and most recently modern ]. | ||

| ] has been recognized as a prominent opponent of the clockwork universe theory, though the theory has often been wrongly attributed to him. Edward B. Davis has acknowledged Newton's belief that the clockwork universe theory wrongly reduces God's role in the universe, as reflected in the writings of Newton-supporter ]. Responding to ], a prominent supporter of the theory, in the ], Clarke wrote: | ] has been recognized as a prominent opponent of the clockwork universe theory, though the theory has often been wrongly attributed to him. Edward B. Davis has acknowledged Newton's belief that the clockwork universe theory wrongly reduces God's role in the universe, as reflected in the writings of Newton-supporter ]. Responding to ], a prominent supporter of the theory, in the ], Clarke wrote: | ||

Revision as of 11:52, 30 November 2012

"World machine" redirects here. For the album by Level 42, see World Machine.

The clockwork universe theory compares the motions of everything in the universe to the innards of a mechanical clock. This idealized clock continues ticking along, as would a perfect machine, with its gears governed by the laws of physics, making every single aspect of the device completely predictable. Since Newton unified the description of terrestrial and heavenly motion, scientists originally had good reason to believe that the universe was completely deterministic at least in principle.

This was not incompatible with the religious view that God the creator wound up the universe in the first place at the Big Bang; and from there the laws of science took hold and have governed every sequence of events since; aka Secondary Causation. But it did tend to undermine the notion that God's instant-by-instant attention was required for the universe to function as expressed in the theory of Occasionalism.

The clockwork universe was popular among deists during the Enlightenment, when scientists demonstrated that Newton's laws of motion, including the law of universal gravitation, could explain the behavior of falling objects on earth as well as the motion of the planets to within the limits of the observational accuracy of the day.

Opposition

Suggested arguments against the possibility of the universe being precisely predictable via the laws of science include: the concept of free will acting through the agency of a soul not strictly governed by the laws of physics; the second law of thermodynamics (the total entropy of any isolated thermodynamic system tends to increase over time, approaching a maximum value); the axiomatic foundation of mathematics which underlies scientific inquiry;quantum physics with its mathematical description of the wave function and the uncertainty principle; and most recently modern Chaos Theory.

Isaac Newton has been recognized as a prominent opponent of the clockwork universe theory, though the theory has often been wrongly attributed to him. Edward B. Davis has acknowledged Newton's belief that the clockwork universe theory wrongly reduces God's role in the universe, as reflected in the writings of Newton-supporter Samuel Clarke. Responding to Gottfried Leibniz, a prominent supporter of the theory, in the Leibniz–Clarke correspondence, Clarke wrote:

"The Notion of the World's being a great Machine, going on without the Interposition of God, as a Clock continues to go without the Assistance of a Clockmaker; is the Notion of Materialism and Fate, and tends, (under pretense of making God a Supra-mundane Intelligence,) to exclude Providence and God's Government in reality out of the World."

World-machine

A similar concept goes back, to John of Sacrobosco's early 13th-century introduction to astronomy: On the Sphere of the World. In this widely popular medieval text, Sacrobosco spoke of the universe as the machina mundi, the machine of the world, suggesting that the reported eclipse of the Sun at the crucifixion of Jesus was a disturbance of the order of that machine.

This conception of the universe consisted of a huge, regulated and uniform machine that operated according to natural laws in absolute time, space, and motion. God was the master-builder, who created the perfect machine and let it run. God was the Prime Mover, who brought into being the world in its lawfulness, regularity, and beauty. This view of God as the creator, who stood aside from his work and didn’t get involved directly with humanity, was called Deism (which predates Newton) and was accepted by many who supported the “new philosophy”.

Objections Due to Entropy

In the mid and late 19th century the concept of Entropy in Thermodynamics was first described by both Rudolph Clausius and William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and was given mathematical rigor by Boltzmann, who had the pivotal equation inscribed on his gravestone. In this context and to the extent it is a correct formulation, it requires disorder in the universe taken as a whole to continually increase and thus demands the universe, or multi-verses, have a begining. Because it is logically impossible for physical objects to spring into existence without a physical cause, many invoke a supernatural being, or God, as the creator of the universe from nothing “ex nihilo”. As such, this argument does not strictly bear on the current functioning of the universe, which is well described by the laws of thermodynamics, but rather on their origin and the possibility of a higher order of laws than found in physics.

Objections Due to Quantum Mechanics

In quantum mechanics, objects are described by wave functions whose amplitudes are smeared out to give only relative probabilities of different states rather than exact locations and velocities. In a sense this does not remove all determinism from physics because, if the initial state of a wave function is known with absolute precision, its future evolution can be exactly predicted, at least in principle. But since the uncertainty principle claims the theoretical impossibility of a precise knowledge of initial conditions, this would prevent any absolute certainty.

In any event, the quantum mechanical argument against determinism is fundamentally rooted in the indeterminate nature of the wave function itself which categorically requires that individual events be unpredictable notwithstanding the exact predictions of their relative probabilities in aggregate.

Needless to say, the philosophical revulsion at this violation of common sense sensibilities generated a few early interpretations of quantum mechanics attemping to reformulate the mathematics along more traditionally conservative lines. Perhaps the most notable of these was Einstein who championed the old world order against the upstart ideas of quantum mechanics with the famous quip:

“God does not play dice with the universe”

But with more rigor, even as the predictive success of quantum mechanics climbed to nearly unassailable heights, Einstein and a small cadre of supporters developed the now famous hidden variable conjecture. The idea was that there might be heretofore unknown aspects of an object which when measured could provide equally accurate mathematical predictions without resort to pesky probability waves.

The difficulties with the mostly unsuccesful attempts to restore determinism to modern physics have been two fold, one practical and the other theoretical. First and foremost, in literally millions of experiments and in many new venues, quantum mechanics has not had a single predictive failure. The other more profound objection to determinism is the discovery by Bell in Bell's theorem of definitive experiments that would conclusively demonstrate whether real-world objects actually exist in many different states simultaneously until they are measured, against all common sense notions; or are really deterministic after all and only appear otherwise perhaps because of our ignorance of some “hidden variables.”

And while not all experimental difficulties or objections have been removed, all attempts to measure Bell’s Inequalities to date indicate that the fundamental indeterminism of quantum particles are real and consequentially that “God does indeed play at dice."

Objections Due to Axiomatic Mathematics

All of geometry and mathematics is based on a few simple assumptions, or unprovable axioms, from which logical consequences are drawn to form a bewilderingly complex assembly of proofs and laws. While the initial assumptions of Euclid's Elements or the Peano Axioms have been chosen to be simple and "self-evident", there can be no assurance that they do not result in some subtle error far down the chain of reasonings.

Indeed one consequence of any axiomatic basis is Godel's Theorem which demonstrates there must be mathematical laws which are both true and logically impossible to prove. In this sense, any mathematical structures we could devise must always be an incomplete theory. And as Galileo opined:

"Philosophy is written in this grand book — I mean the universe — which stands continually open to our gaze, but it cannot be understood unless one first learns to comprehend the language in which it is written. It is written in the language of mathematics, and its characters are triangles, circles, and other geometric figures, without which it is humanly impossible to understand a single word of it; without these, one is wandering about in a dark labyrinth."

Basically none of these considerations imply that mathematics or science is wrong but rather that there is no way to be absolutely certain of their results. Rather we prefer those theories that match all current observations and are simplest. Thus as our knowledge of the wonders of science improves, so does our appreciation of its limits.

Objections Due to Chaos Theory

Since the late 1960's with the rediscovery of Poincaré's proofs on the three body problem, difficulties with many non-periodic real world systems slipping into a chaotic state have been demonstrated. Amazingly, these systems were previously thought to be well described by Newton's classical laws of motion and theory of gravitation. Instabilities in predictions generally arise because of some non-linear aspect as well as an extreme sensitivity to initial conditions.

Another difficulty is that even for simple systems there seems to be a finite limit on any predictability. Even though an increasingly better knowledge of the initial state allows a prediction further into the future, the requirements on initial accuracy increase at a faster rate than the limits on predictability improve. Thus even for classical systems, there is a finite window extending both into the past and the future beyond which no predictions are theoretically possible.

In 1969, Sir James Lighthill (l924-l998) was elected Lucasian Professor of Applied Mathematics at the University of Cambridge to succeed Physics Nobel Laureate, P.A.M. Dirac. As a firm believer of Newtonian mechanics, Sir James’ statement of public apology is an enlightenment to read:

“Here I have to pause, and to speak once again on behalf of the broad global fraternity of practitioners of mechanics. We are all deeply conscious today that the enthusiasm of our forebears for the marvelous achievements of Newtonian mechanics led them to make generalizations in this area of predictability which, indeed, we may have generally tended to believe before 1960, but which we now recognize were false. We collectively wish to apologize for having misled the general educated public by spreading ideas about the determinism of systems satisfying Newton’s laws of motion that, after 1960, were to be proved incorrect. In this lecture, I am trying to make belated amends by explaining both the very different picture that we now discern, and the reasons for it having been uncovered so late.”

The best current evidence seems to be that even for classical systems, the argument for a clockwork universe as a strict consequence of Newtonian dynamics is no longer logically valid. Basically, nature seems to draw a curtain on mechanical motion that is forever beyond our ability to penetrate.

Art

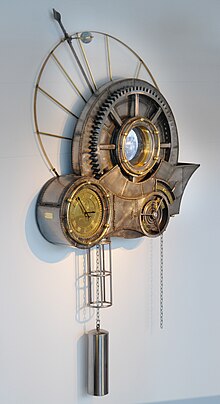

In 2009 artist Tim Wetherell created a large wall piece for Questacon (The National Science and Technology centre in Canberra, Australia) representing the concept of the clockwork universe. This steel artwork contains moving gears, a working clock, and a movie of the moon's terminator in action.

See also

Template:Misplaced Pages-Books

References

- Davis, Edward B. 1991. "Newton's rejection of the "Newtonian world view" : the role of divine will in Newton's natural philosophy." Science and Christian Belief 3, no. 2: 103-117. Clarke quotation taken from article.

- John of Sacrbosco, On the Sphere, quoted in Edward Grant, A Source Book in Medieval Science, (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1974), p. 465.

- "The Born-Einstein Letters", Bohn, Walker and Company, New York, 1971 (paraphrase).

- "Can quantum-mechanical description of physical reality be considered complete?", Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen, Phys. Rev. 47 777 (1935).

- "On the Einstein–Poldolsky–Rosen paradox", Bell, Physics 1 195-200 (1964).

- "The Philosophy of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries", (1966) by Richard Henry Popkin, p. 65.

- “Sir James Lighthill and Modern Fluid Mechanics”, by Lokenath Debnath, The University of Texas-Pan American, US, Imperial College Press: ISBN-13 978-1-84816-113-9: ISBN-10 1-84816-113-1, Singapore, page 31. Online at http://cs5594.userapi.com/u11728334/docs/25eb2e1350a5/Lokenath_Debnath_Sir_James_Lighthill_and_mode.pdf

- "A Short Scheme of the True Religion", manuscript quoted in Memoirs of the Life, Writings and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton by Sir David Brewster, Edinburgh, 1850; cited in; ibid, p. 65.

- Webb, R.K. ed. Knud Haakonssen. "The Emergence of Rational Dissent." Enlightenment and Religion: Rational Dissent in Eighteenth-Century Britain. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 1996. p. 19.

- Westfall, Richard S. Science and Religion in Seventeenth-Century England. p. 201.

Further reading

- Dolnick, Edward, The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World, Harper Collins, 2011.

External links

- "The Clockwork Universe". The Physical World. Ed. John Bolton, Alan Durrant, Robert Lambourne, Joy Manners, Andrew Norton.