| Revision as of 07:32, 17 April 2021 view sourceTrangaBellam (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers22,563 edits DesaiTag: Visual edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 08:45, 17 April 2021 view source TrangaBellam (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers22,563 edits DesaiTags: nowiki added Visual editNext edit → | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

| The mosque is named after a well, the ''Gyan Vapi'' ("Well of Knowledge"), which is located within the mosque precincts.{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2007|p=5}} | The mosque is named after a well, the ''Gyan Vapi'' ("Well of Knowledge"), which is located within the mosque precincts.{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2007|p=5}} | ||

| == History |

== History == | ||

| ⚫ | Scholars generally accept that Aurangzeb indeed demolished a temple but for political reasons than religious zealotry. | ||

| === Sources === | |||

| ⚫ | Kṛtyakalpataru, an early 12th century |

||

| ⚫ | Numerous colonial accounts from the 1800s and early 1900s note of adjoined ruins belonging to a temple and a common Hindu belief that the mosque stood upon their sacred space; the Gyan Vapi well in particular was a regular destination on the Hindu pilgrimage routes in the city.{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2017|p=82}} | ||

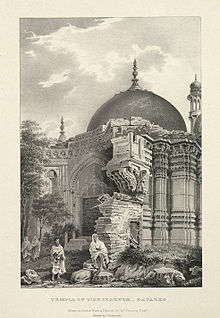

| ⚫ | In 1822, ] had captioned an illustration of the rear wall as "Temple of Vishveshwur" in his ''Benares Illustrated''; he noted that the Hindus worshiped the ] of the mosque as the plinth of the old.<ref>{{cite book|author=James Prinsep|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0uA_AQAAMAAJ|title=Benares Illustrated in a Series of Drawings|year=1996|isbn=9788171241767|page=29}}</ref>{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2007|pp=5–6}} Describing the site in 1824, British traveler ] noted of "Aulam Gheer" (Alamgir I i.e. ]) to have defiled a sacred Hindu spot and built a mosque on it. Local Hindus considered the spot of the mosque more sacred than the newly constructed ] (by ]) and the water of the Gyan Vapi — brought by a subterraneous channel of the Ganges — was holier than the Ganges itself.<ref name="Reginald_1829">{{cite book|author=Reginald Heber|url=https://archive.org/stream/narrativeofjourn01hebe#page/258/mode/2up|title=Narrative of a journey through the upper provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825|publisher=Philadelphia, Carey, Lea & Carey|year=1829|pages=257–258}}</ref>{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2017|p=83}} ]]]] (1868) wrote that the "extensive remains" of the temple (carrying Hindu, Buddhist as well as Jain artifacts) destroyed by ] were still visible, forming "a large portion of the western wall" of the mosque.<ref name="MASherring_1868">{{cite book|author=Matthew Atmore Sherring|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HlQOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA55|title=The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times|publisher=Trübner & co.|year=1868|pages=51–56|author-link=Matthew Atmore Sherring}}</ref> The Hindus unwillingly allowed the Muslims to retain the mosque, but claimed the courtyard and the wall; further, the Muslims were compelled to use the side entrance.<ref name="MASherring_1868" /> People visited the well "in multitudes".<ref name="MASherring_1868" /> Edwin Greaves (1909) found that the mosque was "not greatly used", but had always been an "eyesore" to the Hindus.<ref name="Edwin_1909">{{cite book|author=Edwin Greaves|url=https://archive.org/stream/kashicityillustr00grea#page/80/mode/2up/search/gyan|title=Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares|publisher=Indian Press|year=1909|location=Allahabad|pages=80–82}}</ref> Hindu worshipers would frequent the site, and receive sacred water from the priest, who sat at a stone screen surrounding the Gyan Vapi.<ref name="Edwin_1909" /> | ||

| === Modern scholarship === | |||

| ⚫ | Scholars generally accept that Aurangzeb indeed demolished a temple but for political reasons than religious zealotry. |

||

| The temple was probably constructed by ] (during ]'s reign), whose great-grandson ] was widely alleged to have facilitated Shivaji's ].<ref name="Catherine1992" /><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=EATON|first=RICHARD M.|date=2000|title=TEMPLE DESECRATION AND INDO-MUSLIM STATES|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26198197|journal=Journal of Islamic Studies|volume=11|issue=3|pages=306-307|issn=0955-2340}}</ref> Also, not only did the local ]s of Varanasi rebel against Aurangzeb but also there were reports of local ]s interfering with Islamic teaching.<ref name="Catherine1992" /><ref name=":0" /> Catherine Asher thus finds the demolition to be a political message in that it served as a warning for the Zamindars and Hindu religious leaders, who wielded great influence in the city.<ref name="Catherine1992" /> ] as well as ] take a similar stance.<ref name=":0" /> Madhuri Desai notes that Aurangzeb's actions in Benaras can be "more accurately analyzed in light of his personal compulsions and political agenda, rather than as expressions of religious bigotry".<ref name=":4">{{Cite book|last=Desai|first=Madhuri|title=Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=2017|isbn=978-0-295-74160-4|chapter=INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOX OF BANARAS|chapter-url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnwvg.4}}</ref> | The temple was probably constructed by ] (during ]'s reign), whose great-grandson ] was widely alleged to have facilitated Shivaji's ].<ref name="Catherine1992" /><ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=EATON|first=RICHARD M.|date=2000|title=TEMPLE DESECRATION AND INDO-MUSLIM STATES|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26198197|journal=Journal of Islamic Studies|volume=11|issue=3|pages=306-307|issn=0955-2340}}</ref> Also, not only did the local ]s of Varanasi rebel against Aurangzeb but also there were reports of local ]s interfering with Islamic teaching.<ref name="Catherine1992" /><ref name=":0" /> Catherine Asher thus finds the demolition to be a political message in that it served as a warning for the Zamindars and Hindu religious leaders, who wielded great influence in the city.<ref name="Catherine1992" /> ] as well as ] take a similar stance.<ref name=":0" /> Madhuri Desai notes that Aurangzeb's actions in Benaras can be "more accurately analyzed in light of his personal compulsions and political agenda, rather than as expressions of religious bigotry".<ref name=":4">{{Cite book|last=Desai|first=Madhuri|title=Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City|publisher=University of Washington Press|year=2017|isbn=978-0-295-74160-4|chapter=INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOX OF BANARAS|chapter-url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvcwnwvg.4}}</ref> | ||

| Line 56: | Line 49: | ||

| Mary Searle-Chatterjee notes that a notable historian of Banaras Hindu University (G. D. Bhatnagar) to contest the view that Aurangzeb destroyed the Vishvanath temple.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Searle-Chatterjee|first=Mary|title=Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context|date=April 1993|publisher=SUNY Press|editor-last=Hertel|editor-first=Bradley R.|series=SUNY Series in Hindu Studies|location=Albany, New York|pages=152-158|chapter=Religious division and the mythology of the past|editor-last2=Humes|editor-first2=Cynthia Ann}}</ref>{{Efn|Searle-Chatterjee refuses to discuss the historical validity of competing narratives. She notes - "The historical issues are irrelevant, since it is dear that whatever the facts were, accounts of the origin of the central ruin are now functioning as symbolic narrative, providing a charter for contemporary attitudes and behavior."}} | Mary Searle-Chatterjee notes that a notable historian of Banaras Hindu University (G. D. Bhatnagar) to contest the view that Aurangzeb destroyed the Vishvanath temple.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|last=Searle-Chatterjee|first=Mary|title=Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context|date=April 1993|publisher=SUNY Press|editor-last=Hertel|editor-first=Bradley R.|series=SUNY Series in Hindu Studies|location=Albany, New York|pages=152-158|chapter=Religious division and the mythology of the past|editor-last2=Humes|editor-first2=Cynthia Ann}}</ref>{{Efn|Searle-Chatterjee refuses to discuss the historical validity of competing narratives. She notes - "The historical issues are irrelevant, since it is dear that whatever the facts were, accounts of the origin of the central ruin are now functioning as symbolic narrative, providing a charter for contemporary attitudes and behavior."}} | ||

| === Colonial accounts === | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | Numerous colonial accounts from the 1800s and early 1900s note of adjoined ruins belonging to a temple and a common Hindu belief that the mosque stood upon their sacred space; the Gyan Vapi well in particular was a regular destination on the Hindu pilgrimage routes in the city.{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2017|p=82}} | ||

| ⚫ | In 1822, ] had captioned an illustration of the rear wall as "Temple of Vishveshwur" in his ''Benares Illustrated''; he noted that the Hindus worshiped the ] of the mosque as the plinth of the old.<ref>{{cite book|author=James Prinsep|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0uA_AQAAMAAJ|title=Benares Illustrated in a Series of Drawings|year=1996|isbn=9788171241767|page=29}}</ref>{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2007|pp=5–6}} Describing the site in 1824, British traveler ] noted of "Aulam Gheer" (Alamgir I i.e. ]) to have defiled a sacred Hindu spot and built a mosque on it. Local Hindus considered the spot of the mosque more sacred than the newly constructed ] (by ]) and the water of the Gyan Vapi — brought by a subterraneous channel of the Ganges — was holier than the Ganges itself.<ref name="Reginald_1829">{{cite book|author=Reginald Heber|url=https://archive.org/stream/narrativeofjourn01hebe#page/258/mode/2up|title=Narrative of a journey through the upper provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825|publisher=Philadelphia, Carey, Lea & Carey|year=1829|pages=257–258}}</ref>{{sfn|Madhuri Desai|2017|p=83}} ]]]] (1868) wrote that the "extensive remains" of the temple (carrying Hindu, Buddhist as well as Jain artifacts) destroyed by ] were still visible, forming "a large portion of the western wall" of the mosque.<ref name="MASherring_1868">{{cite book|author=Matthew Atmore Sherring|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HlQOAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA55|title=The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times|publisher=Trübner & co.|year=1868|pages=51–56|author-link=Matthew Atmore Sherring}}</ref> The Hindus unwillingly allowed the Muslims to retain the mosque, but claimed the courtyard and the wall; further, the Muslims were compelled to use the side entrance.<ref name="MASherring_1868" /> People visited the well "in multitudes".<ref name="MASherring_1868" /> Edwin Greaves (1909) found that the mosque was "not greatly used", but had always been an "eyesore" to the Hindus.<ref name="Edwin_1909">{{cite book|author=Edwin Greaves|url=https://archive.org/stream/kashicityillustr00grea#page/80/mode/2up/search/gyan|title=Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares|publisher=Indian Press|year=1909|location=Allahabad|pages=80–82}}</ref> Hindu worshipers would frequent the site, and receive sacred water from the priest, who sat at a stone screen surrounding the Gyan Vapi.<ref name="Edwin_1909" /> | ||

| == Premises == | == Premises == | ||

| Line 76: | Line 74: | ||

| === Hindu memory === | === Hindu memory === | ||

| Madhuri Desai notes recent accounts to center around a litany of repeated destruction and re-construction.<ref name=":4" /> Pilgrims visiting the present ] are informed |

Madhuri Desai notes recent accounts to center around a litany of repeated destruction and re-construction.<ref name=":4" /> Pilgrims visiting the present ] are informed about the timelessness of the lingam, which, originally used to be in the (nearby) Adi-Vishweshwur temple, before being uprooted and relocated to the Gyan Vapi precincts.<ref name=":4" />{{Efn|The Adi-Vishweshwur Temple was constructed c. 1700 at the initiative of ]. Desai notes that the particular choice of naming suggests a collective Hindu memory of the Vishweshwur lingam having a prior location.}} The site housed the central shrine of ] for centuries until it fell victim to Aurangzeb's intense religious zealotry in 1669, whereby it was demolished and converted to a mosque.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| This forms a part of meta-narrative about Hindu civilization being continually oppressed by Muslim invaders, since time immemorial.<ref name=":4" /> Colonial policies and their apparatuses of knowledge reinforced such ahistorical notions.<ref name=":4" /> Local textbooks of the 1990s supported this reading of the mosque's past.<ref name=":1" /> | This forms a part of meta-narrative about Hindu civilization being continually oppressed by Muslim invaders, since time immemorial.<ref name=":4" /> Colonial policies and their apparatuses of knowledge reinforced such ahistorical notions.<ref name=":4" /> Local textbooks of the 1990s supported this reading of the mosque's past.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

| ⚫ | Scholars reject much of these arguments as dubious. Kṛtyakalpataru, an early 12th century 'nibandha''<nowiki/>''' refers to no temple in the town but several Shaiva lingams, one among which was Vishweshwur.<ref name=":4" /> No unique importance was allotted to it.<ref name=":4" />{{Efn|The center of the sacred region of Kashikshetra lay at Madhyameshwur, north of the contemporary site of the Vishweshwur. Contrast with modern day Kashi, whose central site is the Vishwanath Temple, argued to bear the legacy of Vishweshwur.}} Madhurai Desai, in her reading of Gahadavala literature finds scarce mentions of temples; they were certainly small in scale and insignificant, if they existed at all.<ref name=":4" />{{Efn|Desai also notes that unlike contemporary Indian dynasties, there exist no evidence of Gahadavalas commissioning grand temples. Also, see ].}} Overall, the existence of any Vishweshwur temple in early-medieval Banaras is questionable.<ref name=":4" /> The Vishweshwur lingam started occupying a prominent place in the religious life of Hindus sometime between the 12th and 14th centuries; authors of the fourteenth-century Kashikhand deem the site to be the holiest shrine in the town, governing several traditions.<ref name=":4" /> The details and context of this rise in prominence is not ascertainable from textual and other historical evidence.<ref name=":4" /> The Razia Mosque lying adjacent to the Adi-Vishweshwur is often noted to be a desecration of ancient temple-premises; however, no definitive evidence exists in favor.<ref name=":4" /> | ||

| === Muslim memory === | === Muslim memory === | ||

Revision as of 08:45, 17 April 2021

| Gyan Vapi Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Varanasi, India |

| State | Uttar Pradesh |

| |

| Geographic coordinates | 25°18′40″N 83°00′38″E / 25.311229°N 83.010461°E / 25.311229; 83.010461 |

| Architecture | |

| Founder | Aurangzeb |

| Completed | 1664 |

| Specifications | |

| Dome(s) | 3 |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

The Gyanvapi mosque is located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh, India. It was constructed on the site of the Kashi Vishwanath temple, which had been demolished by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1696.

It is a Jama Masjid located in the heart of the Varanasi city, It is administered by Anjuman Inthazamiya Masajid (AIM). north of Dashashwamedh Ghat, near Lalita Ghat along the river Ganga.

Etymology

The mosque is named after a well, the Gyan Vapi ("Well of Knowledge"), which is located within the mosque precincts.

History

Scholars generally accept that Aurangzeb indeed demolished a temple but for political reasons than religious zealotry.

The temple was probably constructed by Raja Man Singh (during Akbar's reign), whose great-grandson Jai Singh I was widely alleged to have facilitated Shivaji's escape in Agra from Aurangzeb. Also, not only did the local zamindars of Varanasi rebel against Aurangzeb but also there were reports of local Brahmins interfering with Islamic teaching. Catherine Asher thus finds the demolition to be a political message in that it served as a warning for the Zamindars and Hindu religious leaders, who wielded great influence in the city. Richard M. Eaton as well as Satish Chandra take a similar stance. Madhuri Desai notes that Aurangzeb's actions in Benaras can be "more accurately analyzed in light of his personal compulsions and political agenda, rather than as expressions of religious bigotry".

Mary Searle-Chatterjee notes that a notable historian of Banaras Hindu University (G. D. Bhatnagar) to contest the view that Aurangzeb destroyed the Vishvanath temple.

Colonial accounts

Numerous colonial accounts from the 1800s and early 1900s note of adjoined ruins belonging to a temple and a common Hindu belief that the mosque stood upon their sacred space; the Gyan Vapi well in particular was a regular destination on the Hindu pilgrimage routes in the city.

In 1822, James Prinsep had captioned an illustration of the rear wall as "Temple of Vishveshwur" in his Benares Illustrated; he noted that the Hindus worshiped the plinth of the mosque as the plinth of the old. Describing the site in 1824, British traveler Reginald Heber noted of "Aulam Gheer" (Alamgir I i.e. Aurangzeb) to have defiled a sacred Hindu spot and built a mosque on it. Local Hindus considered the spot of the mosque more sacred than the newly constructed Vishwanath temple (by Ahilyabai Holkar) and the water of the Gyan Vapi — brought by a subterraneous channel of the Ganges — was holier than the Ganges itself.

M. A. Sherring (1868) wrote that the "extensive remains" of the temple (carrying Hindu, Buddhist as well as Jain artifacts) destroyed by Aurangzeb were still visible, forming "a large portion of the western wall" of the mosque. The Hindus unwillingly allowed the Muslims to retain the mosque, but claimed the courtyard and the wall; further, the Muslims were compelled to use the side entrance. People visited the well "in multitudes". Edwin Greaves (1909) found that the mosque was "not greatly used", but had always been an "eyesore" to the Hindus. Hindu worshipers would frequent the site, and receive sacred water from the priest, who sat at a stone screen surrounding the Gyan Vapi.

Premises

Reconstruction attempts

In 1698, Bishan Singh, the ruler of Amber, launched an initiative to rebuild the Vishwanath temple. After having his agents survey the surrounding land and detail various claims and controversies on the topic, his court purchased the land around the Gyanvapi precinct but was unable to rebuild the temple. In 1742, the Maratha ruler Malhar Rao Holkar made a plan to demolish the mosque and reconstruct Vishweshwar temple at the site. However, his plan did not materialize, partially because of intervention by the Nawabs of Lucknow, who controlled the territory.

Around 1750, the Maharaja of Jaipur commissioned a survey of the land around the site, with the objective of purchasing land to rebuild the Kashi Vishwanath temple. The survey map provides detailed information about the buildings in this area and information about their ownership; the edges of the rectangular Gyanvapi mosque precinct were lined up with the residences of Brahmin priests. Later, in 1780, his daughter-in-law Ahilyabai Holkar constructed the present Kashi Vishwanath Temple adjacent to the mosque.

Colonnade

In 1828, Baiza Bai, widow of the Maratha ruler Daulat Rao Scindhia of Gwalior State, constructed a colonnade in the Gyan Vapi precinct. Sherring (1868) mentioned that the well was surrounded by this low-roofed colonnade, which had over 40 stone pillars, organized in 4 rows. To the east of the colonnade, there was a 7-feet high stone statue of Nandi bull, gifted by the Raja of Nepal. To further east, there was a temple dedicated to Shiva, sponsored by the Rani of Hyderabad. On the south side of the colonnade, there were two small shrines (one stone and the other marble), enclosed by an iron palisade. In this courtyard, about 150 yards from the mosque, there was a 60-feet high temple, claimed to be "Adi-Bisheswar", anterior to the original Kashi Vishwanath temple.

Sherring also described a large collection of statues of Hindu gods, called "the court of Mahadeva" by the locals. According to him, the statues were not modern, and were probably taken "from the ruins of the old temple of Bisheswar". He also wrote that the Muslims had built a gateway in the midst of the platform in front of the mosque, but were not allowed to use it by the Hindus. Violence was prevented by the intervention of the Magistrate of Benares. Sherring further stated that the Hindus worshipped a peepal tree that overhanged the gateway, and the Hindus did not allow Muslims to "pluck a single leaf from it."

Greaves (1909) also mentioned the colonnade and the bull statue, stating that the statue was highly venerated and "freely worshipped". Close to this statue, there was a temple dedicated to Gauri Shankar (Shiva and Parvati). Greaves further wrote that there were "one or two other small temples" in the same open space, and there was a large Ganesha statue placed near the well.

Contestations

The site has been extensively contested by the local Hindu as well as Muslim population, often with an antagonistic aim to further respective agendas in current-day politics. Desai notes the multiple histories of reconstructing the original temple and tensions arising out of the location of Gyanvapi to have fundamentally shaped the sacred topography of the city.

Hindu memory

Madhuri Desai notes recent accounts to center around a litany of repeated destruction and re-construction. Pilgrims visiting the present Kashi Vishwanath Temple are informed about the timelessness of the lingam, which, originally used to be in the (nearby) Adi-Vishweshwur temple, before being uprooted and relocated to the Gyan Vapi precincts. The site housed the central shrine of Vishvanath for centuries until it fell victim to Aurangzeb's intense religious zealotry in 1669, whereby it was demolished and converted to a mosque.

This forms a part of meta-narrative about Hindu civilization being continually oppressed by Muslim invaders, since time immemorial. Colonial policies and their apparatuses of knowledge reinforced such ahistorical notions. Local textbooks of the 1990s supported this reading of the mosque's past.

Scholars reject much of these arguments as dubious. Kṛtyakalpataru, an early 12th century 'nibandha' refers to no temple in the town but several Shaiva lingams, one among which was Vishweshwur. No unique importance was allotted to it. Madhurai Desai, in her reading of Gahadavala literature finds scarce mentions of temples; they were certainly small in scale and insignificant, if they existed at all. Overall, the existence of any Vishweshwur temple in early-medieval Banaras is questionable. The Vishweshwur lingam started occupying a prominent place in the religious life of Hindus sometime between the 12th and 14th centuries; authors of the fourteenth-century Kashikhand deem the site to be the holiest shrine in the town, governing several traditions. The details and context of this rise in prominence is not ascertainable from textual and other historical evidence. The Razia Mosque lying adjacent to the Adi-Vishweshwur is often noted to be a desecration of ancient temple-premises; however, no definitive evidence exists in favor.

Muslim memory

Most Muslims of the city however reject the narrative produced by Hindu as well as Colonial accounts.

Varying theories are put forward instead — (a) the original building was never a temple but a structure of the Din-i Ilahi faith which was destroyed as a result of Aurangzeb's hostility to Akbar's "heretical" thought-school, (b) the original building was indeed a temple but destroyed by Jnan Chand (a Hindu) as a consequence of the priest having looted and violated one of his female relatives, (c) the temple was destroyed by Aurangzeb because it served as a hub of political rebellion — all of which converge on the aspect that Aurangzeb did not demolish the temple for religious reasons. Relatively fringe arguments include that the Gyanvapi was constructed much before Aurangzeb's reign or that the temple was demolished due to a communal conflict which must have involved Hindus playing a significant role in provoking the Muslims.

These viewpoints have been extensively developed and amplified by Maulana Abdus Salam Nomani (d. 1987), an Imam of the Gyanvapi mosque, over leading Urdu dailies. Using historical evidence, Nomani rejects that Aurangzeb demolished any temple to commission the mosque. The foundation of the mosque was allegedly laid by the third Mughal emperor Akbar; Aurangzeb's father Shah Jahan had started a madrasah called Imam-e-Sharifat at the site of the mosque in 1048 hijri (1638-39 CE). Aurangzeb's edict granting protection to all Hindu temples at Baranasi and his' providing patronage to numerous temples, Hindu schools, and monasteries are further cited.

Communalism

The site remains volatile and has witnessed periodic communal tensions.

Colonial India

1809 saw multiple severe incidences. An attempt by the Hindu community to construct a shrine on the "neutral" space between the Gyanvapi Mosque and the Kashi Vishwanath Temple heightened tensions. Soon enough, the festival of Holi and Muharram fell on the same day and confrontation by revelers fomented into a communal riot. Muslim mob killed a cow (sacred to Hindus) on the spot, and spread its blood into the sacred water of the well. In retaliation, the Hindus threw rashers of bacon (haram to Muslims) into windows of several mosques. Subsequently, both the parties took to arms, resulting in several deaths and property damage, before the British administration quelled the riot.

Postcolonial India

In the 1990s, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) engaged in a nation-wide campaign to reclaim the sites of the mosques (allegedly) constructed by demolishing Hindu temples. A title-dispute suit was accordingly filed in the Varanasi Civil Court in 1991; the petition asked for handing over the land to Hindu community and sought to bypass the Places of Worship (Special Provisions) Act, 1991 (henceforth PoW), which was already in force.

After the demolition of the Babri mosque in December 1992, tensions increased and about a thousand policemen were deployed to prevent a similar incident at the Gyanvapi. The Bharatiya Janata Party leaders (who had supported the demand for "reclaiming" Babri mosque) however opposed VHP's demand this time, on the grounds that the Gyanvapi Mosque was actively used. In 1998, the court ruled that the suit was indeed barred by the PoW act. A revision petition was subsequently moved before the district court who allowed it and asked the civil court to adjudicate the dispute, afresh. The mosque management committee successfully challenged this allowance in the Allahabad High Court, who stayed the proceedings. In 1996, VHP appealed to the Hindus to gather in large number on the occasion of Mahashivaratri; it was met with a poor response and the occasion passed without any untoward incident.

The court-case remained pending for 22 years, before the advocate of the 1991 petition refiled another plea requesting for an ASI survey of the mosque-complex on the same grounds. The temple allegedly existed for thousands of years (since the reign of a Vikramaditya) before being demolished by Aurangzeb; this was apparently proved by the continuous presence of Lingam among other features and Hindus were deprived of their religious right to offer water to lingams. The Gyanvapi mosque management committee (Anjuman Intezamia Masjid) acting as the defendant denied the claims and rejected that Aurangzeb demolished a temple to construct the mosque.

On 8th April 2021, the city-court ordered the Archaeological Survey of India to conduct the requested survey. In addition, a five-member committee comprising experts in archaeology was asked to be constituted, with two members from the "minority community" to determine whether any temple existed at the site, prior to the mosque. Some commentators opine the court's ruling to run up against the PoW act and other matters of law.

Architecture

The façade is modeled partially on the Taj Mahal's entrance. The remains of the erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque. Entry into the mosque precinct is restricted, and photography of the mosque's exterior is banned. M. A. Sherring (1868), described the mosque (minus the temple remnants) as plain, with few carvings. Its walls were "besmeared with a dirty white-wash, mixed with a little colouring matter."

See also

- Other notable mosques in Varanasi: Ganj-e-Shaheedan Mosque and Chaukhamba Mosque

- Conversion of non-Muslim places of worship into mosques

Notes

- Searle-Chatterjee refuses to discuss the historical validity of competing narratives. She notes - "The historical issues are irrelevant, since it is dear that whatever the facts were, accounts of the origin of the central ruin are now functioning as symbolic narrative, providing a charter for contemporary attitudes and behavior."

- The Adi-Vishweshwur Temple was constructed c. 1700 at the initiative of Sawai Jai Singh II. Desai notes that the particular choice of naming suggests a collective Hindu memory of the Vishweshwur lingam having a prior location.

- The center of the sacred region of Kashikshetra lay at Madhyameshwur, north of the contemporary site of the Vishweshwur. Contrast with modern day Kashi, whose central site is the Vishwanath Temple, argued to bear the legacy of Vishweshwur.

- Desai also notes that unlike contemporary Indian dynasties, there exist no evidence of Gahadavalas commissioning grand temples. Also, see Vishnu Hari inscription.

- The Ayodhya dispute was stated as an exception to the provision since it was already being litigated when the law was passed.

References

- ^ Catherine B. Asher (24 September 1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 278–279. ISBN 978-0-521-26728-1.: "... there is evidence only for his demolition in 1669 of the Vishvanath temple, built almost certainly by Raja Man Singh during Akbar's reign. Aurangzeb's demolition of the temple was motivated by specific events, not bigotry.... The demolition of the Vishvanath temple, then, was intended as a warning to anti-Mughal factions, in this case troublesome zamindars and Hindu religious leaders who wielded great influence in this city."

- Diane P. Mines; Sarah Lamb (2002). Everyday Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. pp. 344–. ISBN 0-253-34080-2.

- "VHP game in Benares, with official blessings". Frontline. 12 (14–19). S. Rangarajan for Kasturi & Sons: 14. 1995.

- Madhuri Desai 2007, p. 5.

- ^ EATON, RICHARD M. (2000). "TEMPLE DESECRATION AND INDO-MUSLIM STATES". Journal of Islamic Studies. 11 (3): 306–307. ISSN 0955-2340.

- ^ Desai, Madhuri (2017). "INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOX OF BANARAS". Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74160-4.

- ^ Searle-Chatterjee, Mary (April 1993). "Religious division and the mythology of the past". In Hertel, Bradley R.; Humes, Cynthia Ann (eds.). Living Banaras: Hindu Religion in Cultural Context. SUNY Series in Hindu Studies. Albany, New York: SUNY Press. pp. 152–158.

- Madhuri Desai 2017, p. 82.

- James Prinsep (1996). Benares Illustrated in a Series of Drawings. p. 29. ISBN 9788171241767.

- Madhuri Desai 2007, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Reginald Heber (1829). Narrative of a journey through the upper provinces of India, from Calcutta to Bombay, 1824-1825. Philadelphia, Carey, Lea & Carey. pp. 257–258.

- Madhuri Desai 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Matthew Atmore Sherring (1868). The Sacred City of the Hindus: An Account of Benares in Ancient and Modern Times. Trübner & co. pp. 51–56.

- ^ Edwin Greaves (1909). Kashi the city illustrious, or Benares. Allahabad: Indian Press. pp. 80–82.

- Madhuri Desai 2017, p. 58.

- Madhuri Desai 2017, p. 81.

- ^ Madhuri Desai 2007, p. 85.

- Madhuri Desai 2017, p. 83; Madhuri Desai 2007, p. 2

- Diane P. Mines and Sarah Lamb (2002). Everyday Life in South Asia. Indiana University Press. p. 344. ISBN 9780253340801.

- Suvir Kaul (2001). The Partitions of Memory: The Afterlife of the Division of India. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 279. ISBN 9781850655831.

- ^ L. Eck, Diana (1982). Banaras: City of Light. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-83295-5.

- Maduri Desai 2007, p. 33. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMaduri_Desai2007 (help)

- Casolari, Marzia (2002). "Role of Benares in Constructing Political Hindu Identity". Economic and Political Weekly. 37 (15): 1413–1420. ISSN 0012-9976.

- ^ Taskin Bismee, Decoding the Kashi Vishwanath-Gyanvapi dispute, and why Varanasi court has ordered ASI survey, The Print, 10 April 2021.

- Venkataramanan, K. (17 November 2019). "What does the Places of Worship Act protect?". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- Sanjoy Majumder (25 March 2004). "Cracking India's Muslim vote". BBC News. Uttar Pradesh.

- Manjari Katju (1 January 2003). Vishva Hindu Parishad and Indian Politics. Orient Blackswan. pp. 113–114. ISBN 978-81-250-2476-7.

- ^ Yamunan, Sruthisagar. "Analysis: Could ASI survey of Gyanvapi mosque lead to it being exempted from Places of Worship Act?". Scroll.in. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Engineer, Asghar Ali (1997). "Communalism and Communal Violence, 1996". Economic and Political Weekly. 32 (7): 324. ISSN 0012-9976.

- Jitendra Sarin (8 May 2017). "Allahabad HC to hear Vishwanath temple, Gyanvapi mosque dispute on May 10". Hindustan Times.

- SINGH, JAS (2015). "India's Right Turn". World Policy Journal. 32 (2): 94. ISSN 0740-2775.

- ^ Court Revives Dormant Dispute, asks ASI to Survey Gyanvapi Mosque Next to Kashi Vishwanath Temple, The Wire, 10 April 2021.

- Shrutisagar Yamunan, Why UP court order asking ASI to survey Kashi-Gyanvapi mosque complex is legally unsound, Scroll.in, 10 April 2021.

- Vanessa Betts; Victoria McCulloch (30 October 2013). Delhi to Kolkata Footprint Focus Guide. Footprint Travel Guides. pp. 108–. ISBN 978-1-909268-40-1.

- Madhuri Desai (2003). "Mosques, Temples, and Orientalists: Hegemonic Imaginations in Banaras" (PDF). Traditional Dwellings and Settlements. XV (1): 23–37.

Bibliography

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: A-M. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- Madhuri Desai (2017). Banaras Reconstructed: Architecture and Sacred Space in a Hindu Holy City. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74161-1.

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||