| Revision as of 08:32, 14 December 2023 editKuvam Bhanot (talk | contribs)50 edits →top: Fixed typoTags: Reverted canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit← Previous edit | Revision as of 13:13, 14 December 2023 edit undoDVdm (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers138,494 edits Reverting edit(s) by Kuvam Bhanot (talk) to rev. 1189533845 by Nsbfrank: likely factual errors (RW 16.1)Tags: RW UndoNext edit → | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| In his second relativity paper in 1905, ] showed<ref>{{harvnb|Poincaré|1905–1906|pp=129–176}} Wikisource translation: ]</ref> how, by taking time to be an imaginary fourth ] coordinate {{math|''ict''}}, where {{mvar|c}} is the ] and {{mvar|i}} is the ], ]s can be visualized as ordinary rotations of the four-dimensional Euclidean sphere. The four-dimensional spacetime can be visualized as a four-dimensional space, with each point representing an event in spacetime. The ] can then be thought of as rotations in this four-dimensional space, where the rotation axis corresponds to the direction of relative motion between the two observers and the rotation angle is related to their relative velocity. | In his second relativity paper in 1905, ] showed<ref>{{harvnb|Poincaré|1905–1906|pp=129–176}} Wikisource translation: ]</ref> how, by taking time to be an imaginary fourth ] coordinate {{math|''ict''}}, where {{mvar|c}} is the ] and {{mvar|i}} is the ], ]s can be visualized as ordinary rotations of the four-dimensional Euclidean sphere. The four-dimensional spacetime can be visualized as a four-dimensional space, with each point representing an event in spacetime. The ] can then be thought of as rotations in this four-dimensional space, where the rotation axis corresponds to the direction of relative motion between the two observers and the rotation angle is related to their relative velocity. | ||

| To understand this concept, one should consider the coordinates of an event in spacetime represented as a |

To understand this concept, one should consider the coordinates of an event in spacetime represented as a four-vector (t, x, y, z). A Lorentz transformation is represented by a ] that acts on the four-vector, changing its components. This matrix can be thought of as a rotation matrix in four-dimensional space, which rotates the four-vector around a particular axis.<math display="block">x^2 + y^2 + z^2 + (ict)^2 = \text{constant}. </math> | ||

| Rotations in planes spanned by two space unit vectors appear in coordinate space as well as in physical spacetime as Euclidean rotations and are interpreted in the ordinary sense. The "rotation" in a plane spanned by a space unit vector and a time unit vector, while formally still a rotation in coordinate space, is a ] in physical spacetime with ''real'' inertial coordinates. The analogy with Euclidean rotations is only partial since the radius of the sphere is actually imaginary, which turns rotations into rotations in hyperbolic space (see ]). | Rotations in planes spanned by two space unit vectors appear in coordinate space as well as in physical spacetime as Euclidean rotations and are interpreted in the ordinary sense. The "rotation" in a plane spanned by a space unit vector and a time unit vector, while formally still a rotation in coordinate space, is a ] in physical spacetime with ''real'' inertial coordinates. The analogy with Euclidean rotations is only partial since the radius of the sphere is actually imaginary, which turns rotations into rotations in hyperbolic space (see ]). | ||

| Line 380: | Line 380: | ||

| ===Curvature=== | ===Curvature=== | ||

| As a '''flat spacetime''', the three spatial |

As a '''flat spacetime''', the three spatial components of Minkowski spacetime always obey the ]. Minkowski space is a suitable basis for special relativity, a good description of physical systems over finite distances in systems without significant ]. However, in order to take gravity into account, physicists use the theory of ], which is formulated in the mathematics of a ]. When this geometry is used as a model of physical space, it is known as '']''. | ||

| Even in curved space, Minkowski space is still a good description in an ] surrounding any point (barring gravitational singularities).<ref group=nb>This similarity between ] and curved space at infinitesimally small distance scales is foundational to the definition of a ] in general.</ref> More abstractly, it can be said that in the presence of gravity spacetime is described by a curved 4-dimensional ] for which the ] to any point is a 4-dimensional Minkowski space. Thus, the structure of Minkowski space is still essential in the description of general relativity. | Even in curved space, Minkowski space is still a good description in an ] surrounding any point (barring gravitational singularities).<ref group=nb>This similarity between ] and curved space at infinitesimally small distance scales is foundational to the definition of a ] in general.</ref> More abstractly, it can be said that in the presence of gravity spacetime is described by a curved 4-dimensional ] for which the ] to any point is a 4-dimensional Minkowski space. Thus, the structure of Minkowski space is still essential in the description of general relativity. | ||

Revision as of 13:13, 14 December 2023

Spacetime used in theory of relativity For the fictional concept in the Gundam franchise, see Gundam Universal Century technology § Minovsky physics.For the use of algebraic number theory, see Minkowski space (number field).| This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Misplaced Pages. See Misplaced Pages's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (January 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

In mathematical physics, Minkowski space (or Minkowski spacetime) (/mɪŋˈkɔːfski, -ˈkɒf-/) combines inertial space and time manifolds with a non-inertial reference frame of space and time into a four-dimensional model relating a position (inertial frame of reference) to the field.

The model helps show how a spacetime interval between any two events is independent of the inertial frame of reference in which they are recorded. Mathematician Hermann Minkowski developed it from the work of Hendrik Lorentz, Henri Poincaré, and others said it "was grown on experimental physical grounds."

Minkowski space is closely associated with Einstein's theories of special relativity and general relativity and is the most common mathematical structure by which special relativity is formalized. While the individual components in Euclidean space and time might differ due to length contraction and time dilation, in Minkowski spacetime, all frames of reference will agree on the total interval in spacetime between events. Minkowski space differs from four-dimensional Euclidean space in so far as it treats time differently than the three spatial dimensions.

In 3-dimensional Euclidean space, the isometry group (the maps preserving the regular Euclidean distance) is the Euclidean group. It is generated by rotations, reflections and translations. When time is appended as a fourth dimension, the further transformations of translations in time and Lorentz boosts are added, and the group of all these transformations is called the Poincaré group. Minkowski's model follows special relativity, where motion causes time dilation changing the scale applied to the frame in motion and shifts the phase of light.

Spacetime is equipped with an indefinite non-degenerate bilinear form, called the Minkowski metric, the Minkowski norm squared or Minkowski inner product depending on the context. The Minkowski inner product is defined so as to yield the spacetime interval between two events when given their coordinate difference vector as an argument. Equipped with this inner product, the mathematical model of spacetime is called Minkowski space. The group of transformations for Minkowski space that preserves the spacetime interval (as opposed to the spatial Euclidean distance) is the Poincaré group (as opposed to the Galilean group).

History

| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

| Spacetime concepts |

| General relativity |

| Classical gravity |

| Relevant mathematics |

Complex Minkowski spacetime

See also: Four-dimensional spaceIn his second relativity paper in 1905, Henri Poincaré showed how, by taking time to be an imaginary fourth spacetime coordinate ict, where c is the speed of light and i is the imaginary unit, Lorentz transformations can be visualized as ordinary rotations of the four-dimensional Euclidean sphere. The four-dimensional spacetime can be visualized as a four-dimensional space, with each point representing an event in spacetime. The Lorentz transformations can then be thought of as rotations in this four-dimensional space, where the rotation axis corresponds to the direction of relative motion between the two observers and the rotation angle is related to their relative velocity.

To understand this concept, one should consider the coordinates of an event in spacetime represented as a four-vector (t, x, y, z). A Lorentz transformation is represented by a matrix that acts on the four-vector, changing its components. This matrix can be thought of as a rotation matrix in four-dimensional space, which rotates the four-vector around a particular axis.

Rotations in planes spanned by two space unit vectors appear in coordinate space as well as in physical spacetime as Euclidean rotations and are interpreted in the ordinary sense. The "rotation" in a plane spanned by a space unit vector and a time unit vector, while formally still a rotation in coordinate space, is a Lorentz boost in physical spacetime with real inertial coordinates. The analogy with Euclidean rotations is only partial since the radius of the sphere is actually imaginary, which turns rotations into rotations in hyperbolic space (see hyperbolic rotation).

This idea, which was mentioned only briefly by Poincaré, was elaborated by Minkowski in a paper in German published in 1908 called "The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies." He reformulated Maxwell equations as a symmetrical set of equations in the four variables(x, y, z, ict) combined with redefined vector variables for electromagnetic quantities, and he was able to show directly and very simply their invariance under Lorentz transformation. He also made other important contributions and used matrix notation for the first time in this context. From his reformulation, he concluded that time and space should be treated equally, and so arose his concept of events taking place in a unified four-dimensional spacetime continuum.

Real Minkowski spacetime

In a further development in his 1908 "Space and Time" lecture, Minkowski gave an alternative formulation of this idea that used a real-time coordinate instead of an imaginary one, representing the four variables (x, y, z, t) of space and time in the coordinate form in a four-dimensional real vector space. Points in this space correspond to events in spacetime. In this space, there is a defined light-cone associated with each point, and events not on the light cone are classified by their relation to the apex as spacelike or timelike. It is principally this view of spacetime that is current nowadays, although the older view involving imaginary time has also influenced special relativity.

In the English translation of Minkowski's paper, the Minkowski metric, as defined below, is referred to as the line element. The Minkowski inner product below appears unnamed when referring to orthogonality (which he calls normality) of certain vectors, and the Minkowski norm squared is referred to (somewhat cryptically, perhaps this is a translation dependent) as "sum".

Minkowski's principal tool is the Minkowski diagram, and he uses it to define concepts and demonstrate properties of Lorentz transformations (e.g., proper time and length contraction) and to provide geometrical interpretation to the generalization of Newtonian mechanics to relativistic mechanics. For these special topics, see the referenced articles, as the presentation below will be principally confined to the mathematical structure (Minkowski metric and from it derived quantities and the Poincaré group as symmetry group of spacetime) following from the invariance of the spacetime interval on the spacetime manifold as consequences of the postulates of special relativity, not to specific application or derivation of the invariance of the spacetime interval. This structure provides the background setting of all present relativistic theories, barring general relativity for which flat Minkowski spacetime still provides a springboard as curved spacetime is locally Lorentzian.

Minkowski, aware of the fundamental restatement of the theory which he had made, said

The views of space and time which I wish to lay before you have sprung from the soil of experimental physics, and therein lies their strength. They are radical. Henceforth, space by itself and time by itself are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality.

— Hermann Minkowski, 1908, 1909

Though Minkowski took an important step for physics, Albert Einstein saw its limitation:

At a time when Minkowski was giving the geometrical interpretation of special relativity by extending the Euclidean three-space to a quasi-Euclidean four-space that included time, Einstein was already aware that this is not valid, because it excludes the phenomenon of gravitation. He was still far from the study of curvilinear coordinates and Riemannian geometry, and the heavy mathematical apparatus entailed.

For further historical information see references Galison (1979), Corry (1997) and Walter (1999).

Causal structure

Main article: Causal structure

Where v is velocity, x, y, and z are Cartesian coordinates in 3-dimensional space, c is the constant representing the universal speed limit, and t is time, the four-dimensional vector v = (ct, x, y, z) = (ct, r) is classified according to the sign of ct − r. A vector is timelike if ct > r, spacelike if ct < r, and null or lightlike if ct = r. This can be expressed in terms of the sign of η(v, v) as well, which depends on the signature. The classification of any vector will be the same in all frames of reference that are related by a Lorentz transformation (but not by a general Poincaré transformation because the origin may then be displaced) because of the invariance of the spacetime interval under Lorentz transformation.

The set of all null vectors at an event of Minkowski space constitutes the light cone of that event. Given a timelike vector v, there is a worldline of constant velocity associated with it, represented by a straight line in a Minkowski diagram.

Once a direction of time is chosen, timelike and null vectors can be further decomposed into various classes. For timelike vectors, one has

- future-directed timelike vectors whose first component is positive (tip of vector located in absolute future in the figure) and

- past-directed timelike vectors whose first component is negative (absolute past).

Null vectors fall into three classes:

- the zero vector, whose components in any basis are (0, 0, 0, 0) (origin),

- future-directed null vectors whose first component is positive (upper light cone), and

- past-directed null vectors whose first component is negative (lower light cone).

Together with spacelike vectors, there are 6 classes in all.

An orthonormal basis for Minkowski space necessarily consists of one timelike and three spacelike unit vectors. If one wishes to work with non-orthonormal bases, it is possible to have other combinations of vectors. For example, one can easily construct a (non-orthonormal) basis consisting entirely of null vectors, called a null basis.

Vector fields are called timelike, spacelike, or null if the associated vectors are timelike, spacelike, or null at each point where the field is defined.

Properties of time-like vectors

Time-like vectors have special importance in the theory of relativity as they correspond to events that are accessible to the observer at (0, 0, 0, 0) with a speed less than that of light. Of most interest are time-like vectors that are similarly directed, i.e. all either in the forward or in the backward cones. Such vectors have several properties not shared by space-like vectors. These arise because both forward and backward cones are convex, whereas the space-like region is not convex.

Scalar product

The scalar product of two time-like vectors u1 = (t1, x1, y1, z1) and u2 = (t2, x2, y2, z2) is

Positivity of scalar product: An important property is that the scalar product of two similarly directed time-like vectors is always positive. This can be seen from the reversed Cauchy–Schwarz inequality below. It follows that if the scalar product of two vectors is zero, then one of these, at least, must be space-like. The scalar product of two space-like vectors can be positive or negative as can be seen by considering the product of two space-like vectors having orthogonal spatial components and times either of different or the same signs.

Using the positivity property of time-like vectors, it is easy to verify that a linear sum with positive coefficients of similarly directed time-like vectors is also similarly directed time-like (the sum remains within the light cone because of convexity).

Norm and reversed Cauchy inequality

The norm of a time-like vector u = (ct, x, y, z) is defined as

The reversed Cauchy inequality is another consequence of the convexity of either light cone. For two distinct similarly directed time-like vectors u1 and u2 this inequality is

or algebraically,

From this, the positive property of the scalar product can be seen.

The reversed triangle inequality

For two similarly directed time-like vectors u and w, the inequality is

where the equality holds when the vectors are linearly dependent.

The proof uses the algebraic definition with the reversed Cauchy inequality:

The result now follows by taking the square root on both sides.

Mathematical structure

It is assumed below that spacetime is endowed with a coordinate system corresponding to an inertial frame. This provides an origin, which is necessary for spacetime to be modeled as a vector space. This addition is not required, and more complex treatments analogous to an affine space can remove the extra structure. However, this is not the introductory convention and is not covered here.

For an overview, Minkowski space is a 4-dimensional real vector space equipped with a non-degenerate, symmetric bilinear form on the tangent space at each point in spacetime, here simply called the Minkowski inner product, with metric signature either (+ − − −) or (− + + +). The tangent space at each event is a vector space of the same dimension as spacetime, 4.

Tangent vectors

In practice, one need not be concerned with the tangent spaces. The vector space structure of Minkowski space allows for the canonical identification of vectors in tangent spaces at points (events) with vectors (points, events) in Minkowski space itself. See e.g. Lee (2003, Proposition 3.8.) or Lee (2012, Proposition 3.13.) These identifications are routinely done in mathematics. They can be expressed formally in Cartesian coordinates as

with basis vectors in the tangent spaces defined by

Here p and q are any two events, and the second basis vector identification is referred to as parallel transport. The first identification is the canonical identification of vectors in the tangent space at any point with vectors in the space itself. The appearance of basis vectors in tangent spaces as first-order differential operators is due to this identification. It is motivated by the observation that a geometrical tangent vector can be associated in a one-to-one manner with a directional derivative operator on the set of smooth functions. This is promoted to a definition of tangent vectors in manifolds not necessarily being embedded in R. This definition of tangent vectors is not the only possible one, as ordinary n-tuples can be used as well.

Definitions of tangent vectors as ordinary vectorsA tangent vector at a point p may be defined, here specialized to Cartesian coordinates in Lorentz frames, as 4 × 1 column vectors v associated to each Lorentz frame related by Lorentz transformation Λ such that the vector v in a frame related to some frame by Λ transforms according to v → Λv. This is the same way in which the coordinates x transform. Explicitly,

This definition is equivalent to the definition given above under a canonical isomorphism.

For some purposes, it is desirable to identify tangent vectors at a point p with displacement vectors at p, which is, of course, admissible by essentially the same canonical identification. The identifications of vectors referred to above in the mathematical setting can correspondingly be found in a more physical and explicitly geometrical setting in Misner, Thorne & Wheeler (1973). They offer various degrees of sophistication (and rigor) depending on which part of the material one chooses to read.

Metric signature

The metric signature refers to which sign the Minkowski inner product yields when given space (spacelike to be specific, defined further down) and time basis vectors (timelike) as arguments. Further discussion about this theoretically inconsequential but practically necessary choice for purposes of internal consistency and convenience is deferred to the hide box below. See also the page treating sign convention in Relativity.

The choice of metric signatureIn general, but with several exceptions, mathematicians and general relativists prefer spacelike vectors to yield a positive sign, (− + + +), while particle physicists tend to prefer timelike vectors to yield a positive sign, (+ − − −). Authors covering several areas of physics, e.g. Steven Weinberg and Landau and Lifshitz ((− + + +) and (+ − − −) respectively) stick to one choice regardless of topic. Arguments for the former convention include "continuity" from the Euclidean case corresponding to the non-relativistic limit c → ∞. Arguments for the latter include that minus signs, otherwise ubiquitous in particle physics, go away. Yet other authors, especially of introductory texts, e.g. Kleppner & Kolenkow (1978), do not choose a signature at all, but instead, opt to coordinatize spacetime such that the time coordinate (but not time itself!) is imaginary. This removes the need for the explicit introduction of a metric tensor (which may seem like an extra burden in an introductory course), and one needs not be concerned with covariant vectors and contravariant vectors (or raising and lowering indices) to be described below. The inner product is instead affected by a straightforward extension of the dot product in R to R × C. This works in the flat spacetime of special relativity, but not in the curved spacetime of general relativity, see Misner, Thorne & Wheeler (1973, Box 2.1, Farewell to ict) (who, by the way use (− + + +)). MTW also argues that it hides the true indefinite nature of the metric and the true nature of Lorentz boosts, which are not rotations. It also needlessly complicates the use of tools of differential geometry that are otherwise immediately available and useful for geometrical description and calculation – even in the flat spacetime of special relativity, e.g. of the electromagnetic field.

Terminology

Mathematically associated with the bilinear form is a tensor of type (0,2) at each point in spacetime, called the Minkowski metric. The Minkowski metric, the bilinear form, and the Minkowski inner product are all the same object; it is a bilinear function that accepts two (contravariant) vectors and returns a real number. In coordinates, this is the 4×4 matrix representing the bilinear form.

For comparison, in general relativity, a Lorentzian manifold L is likewise equipped with a metric tensor g, which is a nondegenerate symmetric bilinear form on the tangent space TpL at each point p of L. In coordinates, it may be represented by a 4×4 matrix depending on spacetime position. Minkowski space is thus a comparatively simple special case of a Lorentzian manifold. Its metric tensor is in coordinates with the same symmetric matrix at every point of M, and its arguments can, per above, be taken as vectors in spacetime itself.

Introducing more terminology (but not more structure), Minkowski space is thus a pseudo-Euclidean space with total dimension n = 4 and signature (3, 1) or (1, 3). Elements of Minkowski space are called events. Minkowski space is often denoted R or R to emphasize the chosen signature, or just M. It is perhaps the simplest example of a pseudo-Riemannian manifold.

Then mathematically, the metric is a bilinear form on an abstract four-dimensional real vector space , that is,

where has signature , and signature is a coordinate-invariant property of . The space of bilinear maps forms a vector space which can be identified with , and may be equivalently viewed as an element of this space. By making a choice of orthonormal basis , can be identified with the space . The notation is meant to emphasize the fact that and are not just vector spaces but have added structure. .

An interesting example of non-inertial coordinates for (part of) Minkowski spacetime is the Born coordinates. Another useful set of coordinates is the light-cone coordinates.

Pseudo-Euclidean metrics

Main articles: Pseudo-Euclidean space and Lorentzian manifoldsThe Minkowski inner product is not an inner product, since it is not positive-definite, i.e. the quadratic form η(v, v) need not be positive for nonzero v. The positive-definite condition has been replaced by the weaker condition of non-degeneracy. The bilinear form is said to be indefinite. The Minkowski metric η is the metric tensor of Minkowski space. It is a pseudo-Euclidean metric, or more generally, a constant pseudo-Riemannian metric in Cartesian coordinates. As such, it is a nondegenerate symmetric bilinear form, a type (0, 2) tensor. It accepts two arguments up, vp, vectors in TpM, p ∈ M, the tangent space at p in M. Due to the above-mentioned canonical identification of TpM with M itself, it accepts arguments u, v with both u and v in M.

As a notational convention, vectors v in M, called 4-vectors, are denoted in italics, and not, as is common in the Euclidean setting, with boldface v. The latter is generally reserved for the 3-vector part (to be introduced below) of a 4-vector.

The definition

yields an inner product-like structure on M, previously and also henceforth, called the Minkowski inner product, similar to the Euclidean inner product, but it describes a different geometry. It is also called the relativistic dot product. If the two arguments are the same,

the resulting quantity will be called the Minkowski norm squared. The Minkowski inner product satisfies the following properties.

- Linearity in the first argument

- Symmetry

- Non-degeneracy

The first two conditions imply bilinearity. The defining difference between a pseudo-inner product and an inner product proper is that the former is not required to be positive definite, that is, η(u, u) < 0 is allowed.

The most important feature of the inner product and norm squared is that these are quantities unaffected by Lorentz transformations. In fact, it can be taken as the defining property of a Lorentz transformation in that it preserves the inner product (i.e. the value of the corresponding bilinear form on two vectors). This approach is taken more generally for all classical groups definable this way in classical group. There, the matrix Φ is identical in the case O(3, 1) (the Lorentz group) to the matrix η to be displayed below.

Two vectors v and w are said to be orthogonal if η(v, w) = 0. For a geometric interpretation of orthogonality in the special case, when η(v, v) ≤ 0 and η(w, w) ≥ 0 (or vice versa), see hyperbolic orthogonality.

A vector e is called a unit vector if η(e, e) = ±1. A basis for M consisting of mutually orthogonal unit vectors is called an orthonormal basis.

For a given inertial frame, an orthonormal basis in space, combined with the unit time vector, forms an orthonormal basis in Minkowski space. The number of positive and negative unit vectors in any such basis is a fixed pair of numbers equal to the signature of the bilinear form associated with the inner product. This is Sylvester's law of inertia.

More terminology (but not more structure): The Minkowski metric is a pseudo-Riemannian metric, more specifically, a Lorentzian metric, even more specifically, the Lorentz metric, reserved for 4-dimensional flat spacetime with the remaining ambiguity only being the signature convention.

Minkowski metric

Not to be confused with Minkowski distance which is also called Minkowski metric.From the second postulate of special relativity, together with homogeneity of spacetime and isotropy of space, it follows that the spacetime interval between two arbitrary events called 1 and 2 is:

This quantity is not consistently named in the literature. The interval is sometimes referred to as the square root of the interval as defined here.

The invariance of the interval under coordinate transformations between inertial frames follows from the invariance of

provided the transformations are linear. This quadratic form can be used to define a bilinear form

via the polarization identity. This bilinear form can in turn be written as

Where is a matrix associated with η. While possibly confusing, it is common practice to denote with just η. The matrix is read off from the explicit bilinear form as

and the bilinear form

with which this section started by assuming its existence, is now identified.

For definiteness and shorter presentation, the signature (− + + +) is adopted below. This choice (or the other possible choice) has no (known) physical implications. The symmetry group preserving the bilinear form with one choice of signature is isomorphic (under the map given here) with the symmetry group preserving the other choice of signature. This means that both choices are in accord with the two postulates of relativity. Switching between the two conventions is straightforward. If the metric tensor η has been used in a derivation, go back to the earliest point where it was used, substitute η for −η, and retrace forward to the desired formula with the desired metric signature.

Standard basis

A standard or orthonormal basis for Minkowski space is a set of four mutually orthogonal vectors {e0, e1, e2, e3} such that

and for which when

These conditions can be written compactly in the form

Relative to a standard basis, the components of a vector v are written (v, v, v, v) where the Einstein notation is used to write v = v eμ. The component v is called the timelike component of v while the other three components are called the spatial components. The spatial components of a 4-vector v may be identified with a 3-vector v = (v1, v2, v3).

In terms of components, the Minkowski inner product between two vectors v and w is given by

and

Here lowering of an index with the metric was used.

There are many possible choices of standard basis obeying the condition Any two such bases are related in some sense by a Lorentz transformation, either by a change-of-basis matrix , a real matrix satisfying

or a linear map on the abstract vector space satisfying, for any pair of vectors

Then if two different bases exist, and , can be represented as or . While it might be tempting to think of and as the same thing, mathematically, they are elements of different spaces, and act on the space of standard bases from different sides.

Raising and lowering of indices

Main articles: Raising and lowering indices and tensor contraction

Technically, a non-degenerate bilinear form provides a map between a vector space and its dual; in this context, the map is between the tangent spaces of M and the cotangent spaces of M. At a point in M, the tangent and cotangent spaces are dual vector spaces (so the dimension of the cotangent space at an event is also 4). Just as an authentic inner product on a vector space with one argument fixed, by Riesz representation theorem, may be expressed as the action of a linear functional on the vector space, the same holds for the Minkowski inner product of Minkowski space.

Thus if v are the components of a vector in tangent space, then ημν v = vν are the components of a vector in the cotangent space (a linear functional). Due to the identification of vectors in tangent spaces with vectors in M itself, this is mostly ignored, and vectors with lower indices are referred to as covariant vectors. In this latter interpretation, the covariant vectors are (almost always implicitly) identified with vectors (linear functionals) in the dual of Minkowski space. The ones with upper indices are contravariant vectors. In the same fashion, the inverse of the map from tangent to cotangent spaces, explicitly given by the inverse of η in matrix representation, can be used to define raising of an index. The components of this inverse are denoted η. It happens that η = ημν. These maps between a vector space and its dual can be denoted η (eta-flat) and η (eta-sharp) by the musical analogy.

Contravariant and covariant vectors are geometrically very different objects. The first can and should be thought of as arrows. A linear function can be characterized by two objects: its kernel, which is a hyperplane passing through the origin, and its norm. Geometrically thus, covariant vectors should be viewed as a set of hyperplanes, with spacing depending on the norm (bigger = smaller spacing), with one of them (the kernel) passing through the origin. The mathematical term for a covariant vector is 1-covector or 1-form (though the latter is usually reserved for covector fields).

One quantum mechanical analogy explored in the literature is that of a de Broglie wave (scaled by a factor of Planck's reduced constant) associated with a momentum four-vector to illustrate how one could imagine a covariant version of a contravariant vector. The inner product of two contravariant vectors could equally well be thought of as the action of the covariant version of one of them on the contravariant version of the other. The inner product is then how many times the arrow pierces the planes. The mathematical reference, Lee (2003), offers the same geometrical view of these objects (but mentions no piercing).

The electromagnetic field tensor is a differential 2-form, which geometrical description can as well be found in MTW.

One may, of course, ignore geometrical views altogether (as is the style in e.g. Weinberg (2002) and Landau & Lifshitz 2002) and proceed algebraically in a purely formal fashion. The time-proven robustness of the formalism itself, sometimes referred to as index gymnastics, ensures that moving vectors around and changing from contravariant to covariant vectors and vice versa (as well as higher order tensors) is mathematically sound. Incorrect expressions tend to reveal themselves quickly.

Coordinate free raising and lowering

Given a bilinear form , the lowered version of a vector can be thought of as the partial evaluation of , that is, there is an associated partial evaluation map

The lowered vector is then the dual map . Note it does not matter which argument is partially evaluated due to the symmetry of .

Non-degeneracy is then equivalent to injectivity of the partial evaluation map, or equivalently non-degeneracy indicates that the kernel of the map is trivial. In finite dimension, as is the case here, and noting that the dimension of a finite-dimensional space is equal to the dimension of the dual, this is enough to conclude the partial evaluation map is a linear isomorphism from to . This then allows the definition of the inverse partial evaluation map,

which allows the inverse metric to be defined as

where the two different usages of can be told apart by the argument each is evaluated on. This can then be used to raise indices. If a coordinate basis is used, the metric is indeed the matrix inverse to

The formalism of the Minkowski metric

The present purpose is to show semi-rigorously how formally one may apply the Minkowski metric to two vectors and obtain a real number, i.e. to display the role of the differentials and how they disappear in a calculation. The setting is that of smooth manifold theory, and concepts such as convector fields and exterior derivatives are introduced.

A formal approach to the Minkowski metricA full-blown version of the Minkowski metric in coordinates as a tensor field on spacetime has the appearance

Explanation: The coordinate differentials are 1-form fields. They are defined as the exterior derivative of the coordinate functions x. These quantities evaluated at a point p provide a basis for the cotangent space at p. The tensor product (denoted by the symbol ⊗) yields a tensor field of type (0, 2), i.e. the type that expects two contravariant vectors as arguments. On the right-hand side, the symmetric product (denoted by the symbol ⊙ or by juxtaposition) has been taken. The equality holds since, by definition, the Minkowski metric is symmetric. The notation on the far right is also sometimes used for the related, but different, line element. It is not a tensor. For elaboration on the differences and similarities, see Misner, Thorne & Wheeler (1973, Box 3.2 and section 13.2.)

Tangent vectors are, in this formalism, given in terms of a basis of differential operators of the first order,

where p is an event. This operator applied to a function f gives the directional derivative of f at p in the direction of increasing x with x, ν ≠ μ fixed. They provide a basis for the tangent space at p.

The exterior derivative df of a function f is a covector field, i.e. an assignment of a cotangent vector to each point p, by definition such that

for each vector field X. A vector field is an assignment of a tangent vector to each point p. In coordinates X can be expanded at each point p in the basis given by the ∂/∂x|p. Applying this with f = x, the coordinate function itself, and X = ∂/∂x, called a coordinate vector field, one obtains

Since this relation holds at each point p, the dx|p provide a basis for the cotangent space at each p and the bases dx|p and ∂/∂x|p are dual to each other,

at each p. Furthermore, one has

for general one-forms on a tangent space α, β and general tangent vectors a, b. (This can be taken as a definition, but may also be proved in a more general setting.)

Thus when the metric tensor is fed two vectors fields a, b, both expanded in terms of the basis coordinate vector fields, the result is

where a, b are the component functions of the vector fields. The above equation holds at each point p, and the relation may as well be interpreted as the Minkowski metric at p applied to two tangent vectors at p.

As mentioned, in a vector space, such as modeling the spacetime of special relativity, tangent vectors can be canonically identified with vectors in the space itself, and vice versa. This means that the tangent spaces at each point are canonically identified with each other and with the vector space itself. This explains how the right-hand side of the above equation can be employed directly, without regard to the spacetime point the metric is to be evaluated and from where (which tangent space) the vectors come from.

This situation changes in general relativity. There one has

where now η → g(p), i.e., g is still a metric tensor but now depending on spacetime and is a solution of Einstein's field equations. Moreover, a, b must be tangent vectors at spacetime point p and can no longer be moved around freely.

Chronological and causality relations

Let x, y ∈ M. Here,

- x chronologically precedes y if y − x is future-directed timelike. This relation has the transitive property and so can be written x < y.

- x causally precedes y if y − x is future-directed null or future-directed timelike. It gives a partial ordering of spacetime and so can be written x ≤ y.

Suppose x ∈ M is timelike. Then the simultaneous hyperplane for x is Since this hyperplane varies as x varies, there is a relativity of simultaneity in Minkowski space.

Generalizations

Main articles: Lorentzian manifold and Super Minkowski spaceA Lorentzian manifold is a generalization of Minkowski space in two ways. The total number of spacetime dimensions is not restricted to be 4 (2 or more) and a Lorentzian manifold need not be flat, i.e. it allows for curvature.

Complexified Minkowski space

Complexified Minkowski space is defined as Mc = M ⊕ iM. Its real part is the Minkowski space of four-vectors, such as the four-velocity and the four-momentum, which are independent of the choice of orientation of the space. The imaginary part, on the other hand, may consist of four pseudovectors, such as angular velocity and magnetic moment, which change their direction with a change of orientation. A pseudoscalar i is introduced, which also changes sign with a change of orientation. Thus, elements of Mc are independent of the choice of the orientation.

The inner product-like structure on Mc is defined as u ⋅ v = η(u,v) for any u,v ∈ Mc. A relativistic pure spin of an electron or any half spin particle is described by ρ ∈ Mc as ρ = u+is, where u is the four-velocity of the particle, satisfying u = 1 and s is the 4D spin vector, which is also the Pauli–Lubanski pseudovector satisfying s = −1 and u⋅s = 0.

Generalized Minkowski space

Minkowski space refers to a mathematical formulation in four dimensions. However, the mathematics can easily be extended or simplified to create an analogous generalized Minkowski space in any number of dimensions. If n ≥ 2, n-dimensional Minkowski space is a vector space of real dimension n on which there is a constant Minkowski metric of signature (n − 1, 1) or (1, n − 1). These generalizations are used in theories where spacetime is assumed to have more or less than 4 dimensions. String theory and M-theory are two examples where n > 4. In string theory, there appears conformal field theories with 1 + 1 spacetime dimensions.

de Sitter space can be formulated as a submanifold of generalized Minkowski space as can the model spaces of hyperbolic geometry (see below).

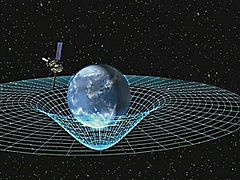

Curvature

As a flat spacetime, the three spatial components of Minkowski spacetime always obey the Pythagorean Theorem. Minkowski space is a suitable basis for special relativity, a good description of physical systems over finite distances in systems without significant gravitation. However, in order to take gravity into account, physicists use the theory of general relativity, which is formulated in the mathematics of a non-Euclidean geometry. When this geometry is used as a model of physical space, it is known as curved space.

Even in curved space, Minkowski space is still a good description in an infinitesimal region surrounding any point (barring gravitational singularities). More abstractly, it can be said that in the presence of gravity spacetime is described by a curved 4-dimensional manifold for which the tangent space to any point is a 4-dimensional Minkowski space. Thus, the structure of Minkowski space is still essential in the description of general relativity.

Geometry

Main article: Hyperboloid modelThe meaning of the term geometry for the Minkowski space depends heavily on the context. Minkowski space is not endowed with Euclidean geometry, and not with any of the generalized Riemannian geometries with intrinsic curvature, those exposed by the model spaces in hyperbolic geometry (negative curvature) and the geometry modeled by the sphere (positive curvature). The reason is the indefiniteness of the Minkowski metric. Minkowski space is, in particular, not a metric space and not a Riemannian manifold with a Riemannian metric. However, Minkowski space contains submanifolds endowed with a Riemannian metric yielding hyperbolic geometry.

Model spaces of hyperbolic geometry of low dimension, say 2 or 3, cannot be isometrically embedded in Euclidean space with one more dimension, i.e. ℝ or ℝ respectively, with the Euclidean metric g, disallowing easy visualization. By comparison, model spaces with positive curvature are just spheres in Euclidean space of one higher dimension. Hyperbolic spaces can be isometrically embedded in spaces of one more dimension when the embedding space is endowed with the Minkowski metric η.

Define H

R ⊂ M to be the upper sheet (ct > 0) of the hyperboloid

in generalized Minkowski space M of spacetime dimension n + 1. This is one of the surfaces of transitivity of the generalized Lorentz group. The induced metric on this submanifold,

the pullback of the Minkowski metric η under inclusion, is a Riemannian metric. With this metric H

R is a Riemannian manifold. It is one of the model spaces of Riemannian geometry, the hyperboloid model of hyperbolic space. It is a space of constant negative curvature −1/R. The 1 in the upper index refers to an enumeration of the different model spaces of hyperbolic geometry, and the n for its dimension. A 2(2) corresponds to the Poincaré disk model, while 3(n) corresponds to the Poincaré half-space model of dimension n.

Preliminaries

In the definition above ι: H

R → M is the inclusion map and the superscript star denotes the pullback. The present purpose is to describe this and similar operations as a preparation for the actual demonstration that H

R actually is a hyperbolic space.

| Behavior of tensors under inclusion, pullback of covariant tensors under general maps and pushforward of vectors under general maps |

|---|

|

Behavior of tensors under inclusion:

where X1, X1, …, Xk are vector fields on S. The subscript star denotes the pushforward (to be introduced later), and it is in this special case simply the identity map (as is the inclusion map). The latter equality holds because a tangent space to a submanifold at a point is in a canonical way a subspace of the tangent space of the manifold itself at the point in question. One may simply write

meaning (with slight abuse of notation) the restriction of α to accept as input vectors tangent to some s ∈ S only. Pullback of tensors under general maps:

where for any vector space V,

It is defined by

where the subscript star denotes the pushforward of the map F, and X, X, …, X are vectors in TpM. (This is in accord with what was detailed about the pullback of the inclusion map. In the general case here, one cannot proceed as simply because F∗X1 ≠ X1 in general.) The pushforward of vectors under general maps: Further unwinding the definitions, the pushforward F∗: TMp → TNF(p) of a vector field under a map F: M → N between manifolds is defined by

where f is a function on N. When M = ℝ, N= ℝ the pushforward of F reduces to DF: ℝ → ℝ, the ordinary differential, which is given by the Jacobian matrix of partial derivatives of the component functions. The differential is the best linear approximation of a function F from ℝ to ℝ. The pushforward is the smooth manifold version of this. It acts between tangent spaces, and is in coordinates represented by the Jacobian matrix of the coordinate representation of the function. The corresponding pullback is the dual map from the dual of the range tangent space to the dual of the domain tangent space, i.e. it is a linear map,

|

Hyperbolic stereographic projection

In order to exhibit the metric, it is necessary to pull it back via a suitable parametrization. A parametrization of a submanifold S of M is a map U ⊂ R → M whose range is an open subset of S. If S has the same dimension as M, a parametrization is just the inverse of a coordinate map φ: M → U ⊂ R. The parametrization to be used is the inverse of hyperbolic stereographic projection. This is illustrated in the figure to the right for n = 2. It is instructive to compare to stereographic projection for spheres.

Stereographic projection σ: H

R → R and its inverse σ: R → H

R are given by

where, for simplicity, τ ≡ ct. The (τ, x) are coordinates on M and the u are coordinates on R.

Detailed derivationLet

and let

If

then it is geometrically clear that the vector

intersects the hyperplane

once in point denoted

One has

or

By construction of stereographic projection one has

This leads to the system of equations

The first of these is solved for and one obtains for stereographic projection

Next, the inverse must be calculated. Use the same considerations as before, but now with

One gets

but now with depending on The condition for P lying in the hyperboloid is

or

leading to

With this , one obtains

Pulling back the metric

One has

and the map

The pulled back metric can be obtained by straightforward methods of calculus;

One computes according to the standard rules for computing differentials (though one is really computing the rigorously defined exterior derivatives),

and substitutes the results into the right hand side. This yields

| Detailed outline of computation |

|---|

|

One has

and

With this one may write

from which

Summing this formula one obtains

Similarly, for τ one gets

yielding

Now add this contribution to finally get

|

This last equation shows that the metric on the ball is identical to the Riemannian metric h

R in the Poincaré ball model, another standard model of hyperbolic geometry.

| Alternative calculation using the pushforward |

|---|

|

The pullback can be computed in a different fashion. By definition,

In coordinates,

One has from the formula for σ

Lastly,

and the same conclusion is reached. |

See also

- Hyperbolic quaternion

- Hyperspace

- Introduction to the mathematics of general relativity

- Minkowski plane

Remarks

- This makes spacetime distance an invariant.

- Consistent use of the terms "Minkowski inner product", "Minkowski norm" or "Minkowski metric" is intended for the bilinear form here, since it is in widespread use. It is by no means "standard" in the literature, but no standard terminology seems to exist.

- Translate the coordinate system so that the event is the new origin.

- This corresponds to the time coordinate either increasing or decreasing when the proper time for any particle increases. An application of T flips this direction.

- For comparison and motivation of terminology, take a Riemannian metric, which provides a positive definite symmetric bilinear form, i. e. an inner product proper at each point on a manifold.

- This similarity between flat space and curved space at infinitesimally small distance scales is foundational to the definition of a manifold in general.

- There is an isometric embedding into ℝ according to the Nash embedding theorem (Nash (1956)), but the embedding dimension is much higher, n = (m/2)(m + 1)(3m + 11) for a Riemannian manifold of dimension m.

Notes

- "Minkowski" Archived 2019-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Lee 1997, p. 31

- Schutz, John W. (1977). Independent Axioms for Minkowski Space–Time (illustrated ed.). CRC Press. pp. 184–185. ISBN 978-0-582-31760-4. Extract of page 184

- Poincaré 1905–1906, pp. 129–176 Wikisource translation: On the Dynamics of the Electron

- Minkowski 1907–1908, pp. 53–111 *Wikisource translation: s:Translation:The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies.

- ^ Minkowski 1908–1909, pp. 75–88 Various English translations on Wikisource: "Space and Time."

- Cornelius Lanczos (1972) "Einstein's Path from Special to General Relativity", pages 5–19 of General Relativity: Papers in Honour of J. L. Synge, L. O'Raifeartaigh editor, Clarendon Press, see page 11

- See Schutz's proof p 148, also Naber p.48

- Schutz p.148, Naber p.49

- Schutz p.148

- Lee 1997, p. 15

- Lee 2003, See Lee's discussion on geometric tangent vectors early in chapter 3.

- Giulini 2008 pp. 5,6

- Gregory L. Naber (2003). The Geometry of Minkowski Spacetime: An Introduction to the Mathematics of the Special Theory of Relativity (illustrated ed.). Courier Corporation. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-486-43235-9. Archived from the original on 2022-12-26. Retrieved 2022-12-26. Extract of page 8 Archived 2022-12-26 at the Wayback Machine

- Sean M. Carroll (2019). Spacetime and Geometry (illustrated, herdruk ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-1-108-48839-6.

- Sard 1970, p. 71

- Minkowski, Landau & Lifshitz 2002, p. 4

- ^ Misner, Thorne & Wheeler 1973

- Lee 2003. One point in Lee's proof of the existence of this map needs modification (Lee deals with Riemannian metrics.). Where Lee refers to positive definiteness to show the injectivity of the map, one needs instead appeal to non-degeneracy.

- Lee 2003, The tangent-cotangent isomorphism p. 282.

- Lee 2003

- Y. Friedman, A Physically Meaningful Relativistic Description of the Spin State of an Electron, Symmetry 2021, 13(10), 1853; https://doi.org/10.3390/sym13101853 Archived 2023-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Jackson, J.D., Classical Electrodynamics, 3rd ed.; John Wiley \& Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA,1998

- Lee 1997, p. 66

- Lee 1997, p. 33

- Lee 1997

References

- Corry, L. (1997). "Hermann Minkowski and the postulate of relativity". Arch. Hist. Exact Sci. 51 (4): 273–314. doi:10.1007/BF00518231. ISSN 0003-9519. S2CID 27016039.

- Catoni, F.; et al. (2008). The Mathematics of Minkowski Space-Time. Frontiers in Mathematics. Basel: Birkhäuser Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-7643-8614-6. ISBN 978-3-7643-8613-9. ISSN 1660-8046.

- Galison, P. L. (1979). R McCormach; et al. (eds.). Minkowski's Space–Time: from visual thinking to the absolute world. Historical Studies in the Physical Sciences. Vol. 10. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 85–121. doi:10.2307/27757388. JSTOR 27757388.

- Giulini D The rich structure of Minkowski space, https://arxiv.org/abs/0802.4345v1.

- Kleppner, D.; Kolenkow, R. J. (1978) . An Introduction to Mechanics. London: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-035048-9.

- Landau, L.D.; Lifshitz, E.M. (2002) . The Classical Theory of Fields. Course of Theoretical Physics. Vol. 2 (4th ed.). Butterworth–Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-2768-9.

- Lee, J. M. (2003). Introduction to Smooth manifolds. Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 218. ISBN 978-0-387-95448-6.

- Lee, J. M. (2012). Introduction to Smooth manifolds. Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics. ISBN 978-1-4419-9981-8.

- Lee, J. M. (1997). Riemannian Manifolds – An Introduction to Curvature. Springer Graduate Texts in Mathematics. Vol. 176. New York · Berlin · Heidelberg: Springer Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-98322-6.

- Minkowski, Hermann (1907–1908), "Die Grundgleichungen für die elektromagnetischen Vorgänge in bewegten Körpern" [The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies], Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse: 53–111

- Published translation: Carus, Edward H. (1918). "Space and Time". The Monist. 28 (288): 288–302. doi:10.5840/monist19182826.

- Wikisource translation: The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies.

- Minkowski, Hermann (1908–1909), "Raum und Zeit" [Space and Time], Physikalische Zeitschrift, 10: 75–88 Various English translations on Wikisource: Space and Time.

- Misner, Charles W.; Thorne, Kip. S.; Wheeler, John A. (1973), Gravitation, W. H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-0344-0.

- Naber, G. L. (1992). The Geometry of Minkowski Spacetime. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-97848-2.

- Nash, J. (1956). "The Imbedding Problem for Riemannian Manifolds". Annals of Mathematics. 63 (1): 20–63. doi:10.2307/1969989. JSTOR 1969989. MR 0075639.

- Penrose, Roger (2005). "18 Minkowskian geometry". Road to Reality : A Complete Guide to the Laws of the Universe. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780679454434.

- Poincaré, Henri (1905–1906), "Sur la dynamique de l'électron" [On the Dynamics of the Electron], Rendiconti del Circolo Matematico di Palermo, 21: 129–176, Bibcode:1906RCMP...21..129P, doi:10.1007/BF03013466, hdl:2027/uiug.30112063899089, S2CID 120211823 Wikisource translation: On the Dynamics of the Electron.

- Robb A A: Optical Geometry of Motion; a New View of the Theory of Relativity Cambridge 1911, (Heffers). http://www.archive.org/details/opticalgeometryoOOrobbrich.

- Robb A A: Geometry of Time and Space, 1936 Cambridge Univ Press http://www.archive.org/details/geometryoftimean032218mbp.

- Sard, R. D. (1970). Relativistic Mechanics - Special Relativity and Classical Particle Dynamics. New York: W. A. Benjamin. ISBN 978-0805384918.

- Shaw, R. (1982). "§ 6.6 Minkowski space, § 6.7,8 Canonical forms pp 221–242". Linear Algebra and Group Representations. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-639201-2.

- Walter, Scott A. (1999). "Minkowski, Mathematicians, and the Mathematical Theory of Relativity". In Goenner, Hubert; et al. (eds.). The Expanding Worlds of General Relativity. Boston: Birkhäuser. pp. 45–86. ISBN 978-0-8176-4060-6.

- Weinberg, S. (2002), The Quantum Theory of Fields, vol. 1, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-55001-7.

External links

![]() Media related to Minkowski diagrams at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Minkowski diagrams at Wikimedia Commons

- Animation clip on YouTube visualizing Minkowski space in the context of special relativity.

- The Geometry of Special Relativity: The Minkowski Space - Time Light Cone

- Minkowski space at PhilPapers

| Relativity | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Special relativity |

| ||||||||||||

| General relativity |

| ||||||||||||

| Scientists | |||||||||||||

, that is,

, that is,

has signature

has signature  , and signature is a coordinate-invariant property of

, and signature is a coordinate-invariant property of  , and

, and  ,

,  can be identified with the space

can be identified with the space  . The notation is meant to emphasize the fact that

. The notation is meant to emphasize the fact that  and

and  are not just vector spaces but have added structure.

are not just vector spaces but have added structure.  .

.

matrix associated with η. While possibly confusing, it is common practice to denote with just η. The matrix is read off from the explicit bilinear form as

matrix associated with η. While possibly confusing, it is common practice to denote with just η. The matrix is read off from the explicit bilinear form as

and for which

and for which  when

when

, a real

, a real

a linear map on the abstract vector space satisfying, for any pair of vectors

a linear map on the abstract vector space satisfying, for any pair of vectors

and

and  ,

,  can be represented as

can be represented as  . While it might be tempting to think of

. While it might be tempting to think of  as the same thing, mathematically, they are elements of different spaces, and act on the space of standard bases from different sides.

as the same thing, mathematically, they are elements of different spaces, and act on the space of standard bases from different sides.

, the lowered version of a vector can be thought of as the partial evaluation of

, the lowered version of a vector can be thought of as the partial evaluation of

is then the dual map

is then the dual map  . Note it does not matter which argument is partially evaluated due to the symmetry of

. Note it does not matter which argument is partially evaluated due to the symmetry of  . This then allows the definition of the inverse partial evaluation map,

. This then allows the definition of the inverse partial evaluation map,

can be told apart by the argument each is evaluated on. This can then be used to raise indices. If a coordinate basis is used, the metric

can be told apart by the argument each is evaluated on. This can then be used to raise indices. If a coordinate basis is used, the metric

where p is an event. This operator applied to a function f gives the

where p is an event. This operator applied to a function f gives the

Since this

Since this

and let

and let

and one obtains for stereographic projection

and one obtains for stereographic projection

must be calculated. Use the same considerations as before, but now with

must be calculated. Use the same considerations as before, but now with

The condition for P lying in the hyperboloid is

The condition for P lying in the hyperboloid is