| Revision as of 05:12, 15 March 2007 editHmains (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers1,214,092 edits /*refine cat← Previous edit | Revision as of 01:43, 31 May 2007 edit undoEvrik (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers88,476 edits →External linksNext edit → | ||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

| Relatively few communities lie directly along the Garlock, as it is situated in the desert, ], ], ], and ] being the closest. However, a major rupture along the Garlock would probably be felt in most of the southern part of California. | Relatively few communities lie directly along the Garlock, as it is situated in the desert, ], ], ], and ] being the closest. However, a major rupture along the Garlock would probably be felt in most of the southern part of California. | ||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| * | * | ||

Revision as of 01:43, 31 May 2007

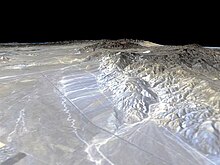

The Garlock Fault Line is a left-lateral strike-slip fault line running approximately northwest-southeast. It marks the northern boundary of the area known as the Mojave Block, as well as the southern ends of the Sierra Nevada and the valleys of the westernmost Basin and Range province. Stretching for 250 kilometers, it is the second-longest fault line in California and is one of the most prominent geological features in the southern part of the state.

The Garlock Fault intersects the San Andreas Fault in Antelope Valley, California, near the "Big Bend" area of the San Andreas, where that fault curves to a more eastern orientation for several hundred miles before turning south again. As the main plane of motion between the Pacific and North American tectonic plates shifted from a line closer to the current west coast to its present-day focus on the San Andreas, the Garlock developed as a result of and an accommodation for stresses in the Big Bend area.

Unlike most of the other transform faults in California, slip on the Garlock Fault is left-lateral; it displaces material to the left. The interaction between this slip and the right-lateral motion of the San Andreas Fault causes the slow counterclockwise rotation of entire blocks of southern California terrain.

Activity in the Garlock Fault

The Garlock moves at a rate of between 2 and 11 millimeters a year, with an average slip of around 7 millimeters. While most of the fault is locked, certain segments have been shown to move by aseismic creep.

The Garlock is not considered to be a particularly active fault, seldom producing any shaking detectable by humans, although it has been known to generate sympathetic seismic events when triggered by other earthquakes and in one instance by the removal of ground water. These events, as well as continuing microearthquake activity and the state of the scarps from previous ruptures, do indicate that the Garlock will produce another major quake at some point in the future.

The most recent notable event was a magnitude 5.7 near the town of Mojave on July 11, 1992. It is thought to have been triggered by the Landers earthquake, just two weeks earlier.

The last significant ruptures on the Garlock were thought to be in the years 1050 A.D. and 1500 A.D.. Research has pinned the interval between significant ruptures on the Garlock as being anywhere between 200 and 3000 years depending on the segment of the fault.

Geography

The Garlock constitutes one of the borders of the Mojave Desert, and is a significant geologic landmark in California. Mountain ranges mark its western edge, and its trace is clearly visible on aerial images of the state.

Relatively few communities lie directly along the Garlock, as it is situated in the desert, Frazier Park, Tehachapi, Mojave, and Johannesburg being the closest. However, a major rupture along the Garlock would probably be felt in most of the southern part of California.