| Revision as of 02:35, 26 January 2008 editBrunodam (talk | contribs)744 editsNo edit summary← Previous edit | Revision as of 03:06, 26 January 2008 edit undoBrunodam (talk | contribs)744 editsNo edit summaryNext edit → | ||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

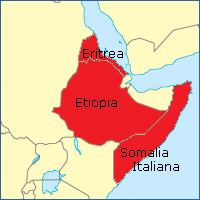

| The '''Italian guerilla war in Ethiopia''' was as an armed struggle fought by remnants of Italian troops in ] following the Italian defeat during the ]. When General ] surrendered with military honors the last troops of the Italian colonial army in ] at ] in November 1941, many Italians decided to start a guerrilla war in the mountains and deserts of ], ] and ]. Nearly 7,000 Italian soldiers (according to the historian Alberto Rosselli<ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale'' pag. 31</ref>) participated in this fight against the British army, in the hope that the German-Italian army of ] would win in Egypt (making the Mediterranean an ]) and retake the recently-occupied territories. | The '''Italian guerilla war in Ethiopia''' was as an armed struggle fought by remnants of Italian troops in ] following the Italian defeat during the ]. When General ] surrendered with military honors the last troops of the Italian colonial army in ] at ] in November 1941, many Italians decided to start a guerrilla war in the mountains and deserts of ], ] and ]. Nearly 7,000 Italian soldiers (according to the historian Alberto Rosselli <ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale''. pag. 31</ref>) participated in this fight against the British army, in the hope that the German-Italian army of ] would win in Egypt (making the Mediterranean an ]) and retake the recently-occupied territories. | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| There were originally two main Italian guerilla organizations: the ''Fronte di Resistenza'' (Front of Resistance) and the ''Figli d'Italia'' (Sons of Italy). | There were originally two main Italian guerilla organizations: the ''Fronte di Resistenza'' (Front of Resistance) and the ''Figli d'Italia'' (Sons of Italy) <ref>Cernuschi, Enrico. ''La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale''. pag. 5</ref>. | ||

| The ''Fronte di Resistenza'' was a military organization led by Colonel Lucchetti and centered in the main cities of the former ]. Its main activities were military sabotage and collection of information about British troops to be sent to ] in multiple ways. | The ''Fronte di Resistenza'' was a military organization led by Colonel Lucchetti and centered in the main cities of the former ]. Its main activities were military sabotage and collection of information about British troops to be sent to ] in multiple ways. | ||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

| The ''Figli d'Italia'' organization was formed in September 1941 by ]s of the "Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale" (a fascist organization of volunteer soldiers). They engaged in a guerrilla war against the British troops and even harassed those Italian civilians and colonial soldiers that had been dubbed "traitors" (for being favorable to cooperation with the British and Ethiopian forces). | The ''Figli d'Italia'' organization was formed in September 1941 by ]s of the "Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale" (a fascist organization of volunteer soldiers). They engaged in a guerrilla war against the British troops and even harassed those Italian civilians and colonial soldiers that had been dubbed "traitors" (for being favorable to cooperation with the British and Ethiopian forces). | ||

| Other groups were the "Amhara" fighters of Lieutenant ] in Eritrea and the guerrilla group of Major Gobbi based at ]. From the beginning of 1942 there was a resistance group in Eritrea, under the orders of Captain Aloisi, dedicated to help soldiers to escape from the British POW camps. In the first months of 1942 (because of the August 1940 ]), there were also Italian guerrillas in ]. | Other groups were the "Amhara" fighters of Lieutenant ] in Eritrea and the guerrilla group of Major Gobbi based at ] <ref>Segre, Vittorio. ''La guerra privata del tenente Guillet''. pag. 11</ref>. From the beginning of 1942 there was a resistance group in Eritrea, under the orders of Captain Aloisi, dedicated to help soldiers to escape from the British POW camps. In the first months of 1942 (because of the August 1940 ]), there were also Italian guerrillas in ]. <ref>Cernuschi, Enrico. ''La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale''. pag. 18</ref>. | ||

| There were many Eritreans and Somalians (and even a few Ethiopians) who helped the Italian guerrillas. But their numbers dwindled after the ] defeat at the ] in 1942. | There were many Eritreans and Somalians (and even a few Ethiopians) who helped the Italian guerrillas. But their numbers dwindled after the ] defeat at the ] in 1942 <ref>Bullotta, Antonia. ''La Somalia sotto due bandiere''. pag. 35</ref>. | ||

| These guerrilla units (called "Bande" in Italian) were able to operate in a very extended area, from northern Eritrea to southern Somalia. Their armament was made up mainly of old rifles "91", pistols "Beretta", machine guns "Fiat" and "Schwarzlose", hand grenades, dynamite and even some small 65 mm cannons. But they always lacked large amounts of ammunition. | These guerrilla units (called "Bande" in Italian) were able to operate in a very extended area, from northern Eritrea to southern Somalia. Their armament was made up mainly of old rifles "91", pistols "Beretta", machine guns "Fiat" and "Schwarzlose", hand grenades, dynamite and even some small 65 mm cannons. But they always lacked large amounts of ammunition <ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale''. pag. 66</ref>. | ||

| From January 1942 many of these "Bande" started to operate under the coordinated orders of general Muratori (commander of the fascist "Milizia"). He was able to encourage a revolt against the British troops by the ] in northern Ethiopia, who had a history of rebellion. The revolt was put down by the British and Ethiopian forces only at the beginning of 1943. | From January 1942 many of these "Bande" started to operate under the coordinated orders of general Muratori (commander of the fascist "Milizia"). He was able to encourage a revolt against the British troops by the ] in northern Ethiopia, who had a history of rebellion. The revolt was put down by the British and Ethiopian forces only at the beginning of 1943 <ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale''. pag. 82</ref>. | ||

| In spring 1942 even the Ethiopian Emperor ] started to open diplomatic "channels of communication" with the Italian insurgents, because he was impressed by the victory of ] in ] (Libya). Major Lucchetti declared (after the war) that the Emperor, had the ] had reached Ethiopia, was ready to accept an Italian Protectorate with these conditions: 1) a total amnesty for all the Ethiopians sentenced by Italy; 2) presence of Ethiopians in all levels of the administration; 3) participation of Emperor Haile Selassie to the future government of the Protectorate. | In spring 1942 even the Ethiopian Emperor ] started to open diplomatic "channels of communication" with the Italian insurgents, because he was impressed by the victory of ] in ] (Libya) <ref>Sbiacchi, Alberto. ''Hailé Selassié and the Italians, 1941-43''. pag. 48</ref>. Major Lucchetti declared (after the war) that the Emperor, had the ] had reached Ethiopia, was ready to accept an Italian Protectorate with these conditions: 1) a total amnesty for all the Ethiopians sentenced by Italy; 2) presence of Ethiopians in all levels of the administration; 3) participation of Emperor Haile Selassie to the future government of the Protectorate <ref>ASMAI/III, ''Archivio Segreto. Relazione Lucchetti''.</ref>. | ||

| In the summer of 1942 the most successful units were those led by Colonel Calderari in Somalia, Colonel Di Marco in the ], Colonel Ruglio amongst the ] and "Blackshirt centurion" De Varda in Ethiopia. Their successful ambushes forced the British to dispatch troops, with airplanes and tanks, from ] and ] to the guerrilla-ridden territories of the former ]. | In the summer of 1942 the most successful units were those led by Colonel Calderari in Somalia, Colonel Di Marco in the ], Colonel Ruglio amongst the ] and "Blackshirt centurion" De Varda in Ethiopia. Their successful ambushes forced the British to dispatch troops, with airplanes and tanks, from ] and ] to the guerrilla-ridden territories of the former ] <ref>Cernuschi, Enrico. ''La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale''. pag. 36</ref>. | ||

| That summer the British decided to put most of the Italian population of coastal ] into concentration camps, in order to avoid their possible contact with Japanese submarines. | That summer the British decided to put most of the Italian population of coastal ] into concentration camps, in order to avoid their possible contact with Japanese submarines <ref> Bullotta, Antonia. ''La Somalia sotto due bandiere''. pag. 72</ref>. | ||

| In October 1942 the Italian guerrillas started to lose steam because of ]'s defeat at the ] and the capture of Major Lucchetti (the head of the ''Fronte di Resistenza'' organization). | In October 1942 the Italian guerrillas started to lose steam because of ]'s defeat at the ] and the capture of Major Lucchetti (the head of the ''Fronte di Resistenza'' organization). | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The guerrilla war continued until summer 1943, when the remaining Italian soldiers started to destroy their armaments and, in some cases, escaped successfully to Italy, like Lieutenant ]. Guillet (nicknamed "the Devil Commander" by the British) reached Taranto on September 3, 1943. He requested from the Italian War Ministry an "aircraft loaded with equipment to be used for guerrilla attacks in Eritrea" (), but the Italian armistice a few days later ended his plan. | The guerrilla war continued until summer 1943, when the remaining Italian soldiers started to destroy their armaments and, in some cases, escaped successfully to Italy, like Lieutenant ] <ref>Segre, Vittorio. ''La guerra privata del tenente Guillet Guillet''. pag. 26</ref> (nicknamed "the Devil Commander" by the British) reached Taranto on September 3, 1943. He requested from the Italian War Ministry an "aircraft loaded with equipment to be used for guerrilla attacks in Eritrea" (), but the Italian armistice a few days later ended his plan. | ||

| One of the last Italian soldiers to surrender to the British forces was Corrado Turchetti, who wrote in his memoirs that some soldiers continued to ambush Allied troops until October 1943. The very last Italian officer who fought the guerrilla war was Colonel Nino Tramonti in ]. | One of the last Italian soldiers to surrender to the British forces was Corrado Turchetti, who wrote in his memoirs that some soldiers continued to ambush Allied troops until October 1943. The very last Italian officer who fought the guerrilla war was Colonel Nino Tramonti in ] <ref>Cernuschi, Enrico. ''La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale''. pag. 74</ref>. | ||

| == Two noteworthy guerrilla actions == | == Two noteworthy guerrilla actions == | ||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

| Of the many Italians who performed guerrilla actions between December 1941 and September 1943, two are worthy of note: | Of the many Italians who performed guerrilla actions between December 1941 and September 1943, two are worthy of note: | ||

| * ], captain of the "Servizio Informazioni Militari" (military intelligence) who in January 1942 blew up an ammunition deposit in ], Eritrea and later organized a group of Eritrean sailors (with small boats called "sambuco") in order to identify, and notify ] with by his radio, of the British navy movements throughout the Red Sea. De Martini received the Italian gold medal of honor. | * ], captain of the "Servizio Informazioni Militari" (military intelligence) who in January 1942 blew up an ammunition deposit in ], Eritrea and later organized a group of Eritrean sailors (with small boats called "sambuco") in order to identify, and notify ] with by his radio, of the British navy movements throughout the Red Sea. De Martini received the Italian gold medal of honor <ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale''. pag. 98</ref>. | ||

| * ], a doctor who in August 1942 succeeded in entering the main ammunition depot of the British army in ], and blowing it up, miraculously surviving the huge explosion. Her sabotage destroyed the ammunition for the new British machine gun "Stern", delaying the use of this "state of the art" armament for many months. Doctor Dainelli was proposed for the Italian iron medal of honor ("croce di ferro"). | * ], a doctor who in August 1942 succeeded in entering the main ammunition depot of the British army in ], and blowing it up, miraculously surviving the huge explosion. Her sabotage destroyed the ammunition for the new British machine gun "Stern", delaying the use of this "state of the art" armament for many months. Doctor Dainelli was proposed for the Italian iron medal of honor ("croce di ferro") <ref>Rosselli, Alberto. ''Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale''. pag. 103</ref>. | ||

| == List of the main Italian guerrilla officers == | == List of the main Italian guerrilla officers == | ||

Revision as of 03:06, 26 January 2008

The Italian guerilla war in Ethiopia was as an armed struggle fought by remnants of Italian troops in Italian East Africa following the Italian defeat during the East African Campaign. When General Guglielmo Nasi surrendered with military honors the last troops of the Italian colonial army in East Africa at Gondar in November 1941, many Italians decided to start a guerrilla war in the mountains and deserts of Ethiopia, Eritrea and Somalia. Nearly 7,000 Italian soldiers (according to the historian Alberto Rosselli ) participated in this fight against the British army, in the hope that the German-Italian army of Rommel would win in Egypt (making the Mediterranean an Italian Mare Nostrum) and retake the recently-occupied territories.

History

There were originally two main Italian guerilla organizations: the Fronte di Resistenza (Front of Resistance) and the Figli d'Italia (Sons of Italy) .

The Fronte di Resistenza was a military organization led by Colonel Lucchetti and centered in the main cities of the former Italian East Africa. Its main activities were military sabotage and collection of information about British troops to be sent to Italy in multiple ways.

The Figli d'Italia organization was formed in September 1941 by Blackshirts of the "Milizia Volontaria per la Sicurezza Nazionale" (a fascist organization of volunteer soldiers). They engaged in a guerrilla war against the British troops and even harassed those Italian civilians and colonial soldiers that had been dubbed "traitors" (for being favorable to cooperation with the British and Ethiopian forces).

Other groups were the "Amhara" fighters of Lieutenant Amedeo Guillet in Eritrea and the guerrilla group of Major Gobbi based at Dessie . From the beginning of 1942 there was a resistance group in Eritrea, under the orders of Captain Aloisi, dedicated to help soldiers to escape from the British POW camps. In the first months of 1942 (because of the August 1940 Italian conquest of British Somaliland), there were also Italian guerrillas in British Somaliland. .

There were many Eritreans and Somalians (and even a few Ethiopians) who helped the Italian guerrillas. But their numbers dwindled after the Axis defeat at the battle of El Alamein in 1942 .

These guerrilla units (called "Bande" in Italian) were able to operate in a very extended area, from northern Eritrea to southern Somalia. Their armament was made up mainly of old rifles "91", pistols "Beretta", machine guns "Fiat" and "Schwarzlose", hand grenades, dynamite and even some small 65 mm cannons. But they always lacked large amounts of ammunition .

From January 1942 many of these "Bande" started to operate under the coordinated orders of general Muratori (commander of the fascist "Milizia"). He was able to encourage a revolt against the British troops by the Azebo Oromo in northern Ethiopia, who had a history of rebellion. The revolt was put down by the British and Ethiopian forces only at the beginning of 1943 .

In spring 1942 even the Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie started to open diplomatic "channels of communication" with the Italian insurgents, because he was impressed by the victory of Rommel in Tobruk (Libya) . Major Lucchetti declared (after the war) that the Emperor, had the Axis had reached Ethiopia, was ready to accept an Italian Protectorate with these conditions: 1) a total amnesty for all the Ethiopians sentenced by Italy; 2) presence of Ethiopians in all levels of the administration; 3) participation of Emperor Haile Selassie to the future government of the Protectorate .

In the summer of 1942 the most successful units were those led by Colonel Calderari in Somalia, Colonel Di Marco in the Ogaden, Colonel Ruglio amongst the Danakil and "Blackshirt centurion" De Varda in Ethiopia. Their successful ambushes forced the British to dispatch troops, with airplanes and tanks, from Kenya and Sudan to the guerrilla-ridden territories of the former Italian East Africa .

That summer the British decided to put most of the Italian population of coastal Somalia into concentration camps, in order to avoid their possible contact with Japanese submarines .

In October 1942 the Italian guerrillas started to lose steam because of Rommel's defeat at the Battle of El Alamein and the capture of Major Lucchetti (the head of the Fronte di Resistenza organization).

The guerrilla war continued until summer 1943, when the remaining Italian soldiers started to destroy their armaments and, in some cases, escaped successfully to Italy, like Lieutenant Amedeo Guillet (nicknamed "the Devil Commander" by the British) reached Taranto on September 3, 1943. He requested from the Italian War Ministry an "aircraft loaded with equipment to be used for guerrilla attacks in Eritrea" (), but the Italian armistice a few days later ended his plan.

One of the last Italian soldiers to surrender to the British forces was Corrado Turchetti, who wrote in his memoirs that some soldiers continued to ambush Allied troops until October 1943. The very last Italian officer who fought the guerrilla war was Colonel Nino Tramonti in Eritrea .

Two noteworthy guerrilla actions

Of the many Italians who performed guerrilla actions between December 1941 and September 1943, two are worthy of note:

- Francesco De Martini, captain of the "Servizio Informazioni Militari" (military intelligence) who in January 1942 blew up an ammunition deposit in Massaua, Eritrea and later organized a group of Eritrean sailors (with small boats called "sambuco") in order to identify, and notify Rome with by his radio, of the British navy movements throughout the Red Sea. De Martini received the Italian gold medal of honor .

- Rosa Dainelli, a doctor who in August 1942 succeeded in entering the main ammunition depot of the British army in Addis Abeba, and blowing it up, miraculously surviving the huge explosion. Her sabotage destroyed the ammunition for the new British machine gun "Stern", delaying the use of this "state of the art" armament for many months. Doctor Dainelli was proposed for the Italian iron medal of honor ("croce di ferro") .

List of the main Italian guerrilla officers

- Lieutenant Amedeo Guillet in Eritrea

- Captain Francesco De Martini in Eritrea

- Captain Paolo Aloisi in Ethiopia

- Captain Leopoldo Rizzo in Ethiopia

- Colonel Di Marco in Ogaden

- Colonel Ruglio in Dancalia

- Blackshirt General Muratori in Ethiopia/Eritrea

- Blackshirt officer De Varda in Ethiopia

- Blackshirt officer Luigi Cristiani in Eritrea

- Major Lucchetti in Ethiopia

- Major Gobbi in Dessie

- Colonel Nino Tramonti in Eritrea

- Colonel Calderari in Somalia

Notes

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 31

- Cernuschi, Enrico. La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale. pag. 5

- Segre, Vittorio. La guerra privata del tenente Guillet. pag. 11

- Cernuschi, Enrico. La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale. pag. 18

- Bullotta, Antonia. La Somalia sotto due bandiere. pag. 35

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 66

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 82

- Sbiacchi, Alberto. Hailé Selassié and the Italians, 1941-43. pag. 48

- ASMAI/III, Archivio Segreto. Relazione Lucchetti.

- Cernuschi, Enrico. La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale. pag. 36

- Bullotta, Antonia. La Somalia sotto due bandiere. pag. 72

- Segre, Vittorio. La guerra privata del tenente Guillet Guillet. pag. 26

- Cernuschi, Enrico. La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale. pag. 74

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 98

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale. pag. 103

Bibliography

- Bullotta, Antonia. La Somalia sotto due bandiere Edizioni Garzanti, 1949 Template:It icon

- Cernuschi, Enrico. La resistenza sconosciuta in Africa Orientale Rivista Storica, dicembre 1994.(Rivista Italiana Difesa) Template:It icon

- Del Boca, Angeli. Gli Italiani in Africa Orientale La caduta dell'Impero Editori Laterza, 1982. Template:It icon

- Rosselli, Alberto. Storie Segrete. Operazioni sconosciute o dimenticate della seconda guerra mondiale Iuculano Editore. Pavia, 2007 Template:It icon

- Sbiacchi, Alberto. Hailé Selassié and the Italians, 1941-43. African Studies Review, vol.XXII, n.1, april 1979. Template:En icon

- ASMAI/III, Archivio Segreto. Relazione Lucchetti. 2 Guerra Mondiale pacco IV. Template:It icon

- Segre, Vittorio. La guerra privata del tenente Guillet. Corbaccio Editore. Milano, 1993 Template:It icon

See also

External links

- The Devil Commander Amedeo Guillet Template:En icon

- The Italian guerrillas in Italian East Africa Template:It icon