| Revision as of 21:52, 7 August 2009 view sourcePeculiar Light (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users4,281 edits Undid revision 306678651 by Born Gay (talk) I had put in a condensed version. You could have reverted to that one.← Previous edit | Revision as of 21:56, 7 August 2009 view source Born Gay (talk | contribs)4,921 edits Sorry, but that's still not acceptable. The lead summarises the main points about conversion therapy and this is not one of themNext edit → | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| '''Conversion therapy''', sometimes called '''reparative therapy''', involves methods intended to convert gay and lesbian people to heterosexuality, which have been a source of intense political controversy in the United States and numerous other countries.<ref name="DrescherandZucker" /> The American Psychiatric Association states that political and moral debates over the integration of gays and lesbians into the mainstream of American society have obscured scientific data about changing sexual orientation "by calling into question the motives and even the character of individuals on both sides of the issue."<ref name="Psych" /> Conversion therapy has been criticized by many ] organizations, but is supported by some ] political and social lobbying groups and by the ] movement.<ref name="challenge">{{citation |url=http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/ChallengingExGay.pdf |title=Challenging the ex-gay movement |accessdate=2007-08-28 |year=1998 |publisher=], National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Equal Partners in Faith}}</ref><ref name="GLAAD" /> The most high-profile contemporary purveyors of conversion therapy tend to be religious organizations, which include ] groups.<ref name="Yoshino">{{Harvnb|Yoshino|2002}}</ref> The main organization advocating secular forms of conversion therapy is the ] (NARTH).<ref name="taskforce" /><ref name="Yoshino" /> | '''Conversion therapy''', sometimes called '''reparative therapy''', involves methods intended to convert gay and lesbian people to heterosexuality, which have been a source of intense political controversy in the United States and numerous other countries.<ref name="DrescherandZucker" /> The American Psychiatric Association states that political and moral debates over the integration of gays and lesbians into the mainstream of American society have obscured scientific data about changing sexual orientation "by calling into question the motives and even the character of individuals on both sides of the issue."<ref name="Psych" /> Conversion therapy has been criticized by many ] organizations, but is supported by some ] political and social lobbying groups and by the ] movement.<ref name="challenge">{{citation |url=http://www.thetaskforce.org/downloads/reports/reports/ChallengingExGay.pdf |title=Challenging the ex-gay movement |accessdate=2007-08-28 |year=1998 |publisher=], National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Equal Partners in Faith}}</ref><ref name="GLAAD" /> The most high-profile contemporary purveyors of conversion therapy tend to be religious organizations, which include ] groups.<ref name="Yoshino">{{Harvnb|Yoshino|2002}}</ref> The main organization advocating secular forms of conversion therapy is the ] (NARTH).<ref name="taskforce" /><ref name="Yoshino" /> | ||

| The ] defines conversion therapy or reparative therapy as therapy aimed at changing ].<ref name="answers">{{citation |url=http://www.apa.org/topics/sorientation.pdf |title=Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality |accessdate=2008-02-14 |year=2008 |month=February |publisher=American Psychological Association |format=PDF}}</ref> The ] states that conversion therapy or reparative therapy is a type of psychiatric treatment "based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation."<ref name="Psych" /> Psychologist Douglas Haldeman writes that conversion therapy comprises efforts by mental health professionals and pastoral care providers to convert lesbians and gay men to heterosexuality, and that techniques include ], ], aversive conditioning involving electric shock or nausea-inducing drugs, fantasy modification, ], reparative therapy, and involvement in ex-gay ministries such as ].<ref name="GonsiorekandWeinrich">{{Harvnb|Gonsiorek|1991}} |

The ] defines conversion therapy or reparative therapy as therapy aimed at changing ].<ref name="answers">{{citation |url=http://www.apa.org/topics/sorientation.pdf |title=Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality |accessdate=2008-02-14 |year=2008 |month=February |publisher=American Psychological Association |format=PDF}}</ref> The ] states that conversion therapy or reparative therapy is a type of psychiatric treatment "based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation."<ref name="Psych" /> Psychologist Douglas Haldeman writes that conversion therapy comprises efforts by mental health professionals and pastoral care providers to convert lesbians and gay men to heterosexuality, and that techniques include ], ], aversive conditioning involving electric shock or nausea-inducing drugs, fantasy modification, ], reparative therapy, and involvement in ex-gay ministries such as ].<ref name="GonsiorekandWeinrich">{{Harvnb|Gonsiorek|1991}}</ref> | ||

| Mainstream American medical and scientific organizations have expressed concern over conversion therapy and consider it potentially harmful.<ref name="apa" /><ref name="Psych">{{citation |url=http://www.psych.org/Departments/EDU/Library/APAOfficialDocumentsandRelated/PositionStatements/200001a.aspx |title=Position Statement on Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies) |accessdate=2007-08-28 | Mainstream American medical and scientific organizations have expressed concern over conversion therapy and consider it potentially harmful.<ref name="apa" /><ref name="Psych">{{citation |url=http://www.psych.org/Departments/EDU/Library/APAOfficialDocumentsandRelated/PositionStatements/200001a.aspx |title=Position Statement on Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies) |accessdate=2007-08-28 | ||

Revision as of 21:56, 7 August 2009

Conversion therapy, sometimes called reparative therapy, involves methods intended to convert gay and lesbian people to heterosexuality, which have been a source of intense political controversy in the United States and numerous other countries. The American Psychiatric Association states that political and moral debates over the integration of gays and lesbians into the mainstream of American society have obscured scientific data about changing sexual orientation "by calling into question the motives and even the character of individuals on both sides of the issue." Conversion therapy has been criticized by many gay and lesbian rights organizations, but is supported by some conservative Christian political and social lobbying groups and by the ex-gay movement. The most high-profile contemporary purveyors of conversion therapy tend to be religious organizations, which include fundamentalist Christian groups. The main organization advocating secular forms of conversion therapy is the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH).

The American Psychological Association defines conversion therapy or reparative therapy as therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation. The American Psychiatric Association states that conversion therapy or reparative therapy is a type of psychiatric treatment "based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her sexual homosexual orientation." Psychologist Douglas Haldeman writes that conversion therapy comprises efforts by mental health professionals and pastoral care providers to convert lesbians and gay men to heterosexuality, and that techniques include psychoanalysis, group therapy, aversive conditioning involving electric shock or nausea-inducing drugs, fantasy modification, sex therapy, reparative therapy, and involvement in ex-gay ministries such as Exodus International.

Mainstream American medical and scientific organizations have expressed concern over conversion therapy and consider it potentially harmful. The advancement of conversion therapy may cause social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about sexual orientation. The ethics guidelines of major mental health organizations in the United States vary from cautionary statements about the safety, effectiveness, and dangers of prejudice associated with conversion therapy (American Psychological Association), to recommendations that ethical practitioners refrain from practicing conversion therapy (American Psychiatric Association) or from referring patients to those who do (American Counseling Association).

Terminology

The American Psychological Association has defined conversion therapy and reparative therapy as “therapy aimed at changing sexual orientation.“ The American Psychiatric Association has stated that it considers conversion therapy and reparative therapy to be forms of "psychiatric treatment…based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder or based upon the a priori assumption that a patient should change his/her homosexual orientation." Robert Spitzer in 2003 used the term reparative therapy to refer to "...any help from a mental health professional or an ex-gay ministry for the purpose of changing sexual orientation". The Just the Facts Coalition, consisting of numerous mainstream mental health and teaching organizations including the American Psychological Association but not the American Psychiatric Association, in 2008 released Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation and Youth, a statement that defined sexual orientation conversion therapy as “counseling and psychotherapy to attempt to eliminate individuals‘ sexual desire for members of their own sex” and “counselling and psychotherapy aimed at eliminating or suppressing homosexuality”. The latter definition was also applied to reparative therapy. It distinguished therapy to change homosexuality from ex-gay ministries, which were defined as "religious groups that use religion to attempt to eliminate those desires." There has been disagreement over the use of the term reparative therapy. GLAAD has stated that the term implies that homosexuality is a disorder and should be avoided, a view also held by some psychologists and sociologists. Jack Drescher writes that properly speaking the term reparative therapy applies only to the approach developed by Elizabeth Moberly and Joseph Nicolosi.

History

Austria and Hungary

Austrian writers who advocated treatment for homosexuality included Richard von Krafft-Ebing, Sigmund Freud, Eugen Steinach, Isidor Sadger, Wilhelm Stekel, and Helene Deutsch. The Hungarian Sandor Ferenczi wrote several of his papers on homosexuality during a period when Hungary was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Melanie Klein wrote about therapy for homosexuality after moving to the United Kingdom in the 1920s to pursue her analytic work with children. Anna Freud and Edmund Bergler also advocated therapy to treat homosexuality. Many of their contributions were made after they were forced to leave Austria in the late 1930s by the rise of Nazism.

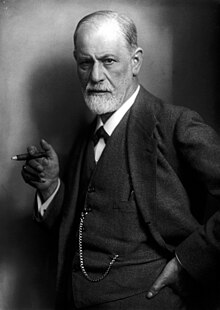

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud was a physician and the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud used the word psychoanalysis for the first time in his 1896 paper “Heredity and the Aetiology of the Neuroses“. Freud's most important articles on homosexuality were written between 1905, when he published Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, and 1922, when he published “Certain Neurotic Mechanisms in Jealousy, Paranoia, and Homosexuality“. Freud believed that all humans were bisexual, by which he primarily meant that everyone incorporates aspects of both sexes. In his view, this was true anatomically and therefore also mentally and psychologically. Heterosexuality and homosexuality both developed from this original bisexual disposition.

Freud suggested that homosexuality could be caused by numerous different biological and psychological factors, but saw all of them as inhibitions of normal sexual development. Freud stated that homosexuality could sometimes be removed through hypnotic suggestion, but did not consider this a convincing argument against the theory that it could be biologically innate in some cases. Freud appears to have been undecided whether or how homosexuality was pathological, expressing different views on this issue at different times and places in his work. Freud frequently called homosexuality an "inversion", something which in his view was distinct from the necessarily pathological perversions, and suggested that several distinct kinds might exist, cautioning that his conclusions about it were based on a small and not necessarily representative sample of patients.

Freud derived much of his information on homosexuality from psychiatrists and sexologists such as Richard von Krafft-Ebing and Magnus Hirschfeld, and was also influenced by Eugen Steinach, a Viennese endocrinologist who transplanted testicles from straight men into gay men in attempts to change their sexual orientation. Freud stated that Steinach's research had “thrown a strong light on the organic determinants of homo-eroticism”“ but cautioned that it was premature to expect that the operations he performed would make possible a therapy that could be generally applied. In his view, such transplant operations would be effective in changing sexual orientation only in cases in which homosexuality was strongly associated with physical characteristics typical of the opposite sex, and probably no similar therapy could be applied to lesbianism. In fact Steinach’s method was doomed to failure because the immune systems of his patients rejected the transplanted glands, and was eventually exposed as ineffective and often harmful.

Freud‘s main discussion of female homosexuality was the 1920 paper “The Psychogenesis of a Case of Homosexuality in a Woman“, which described his analysis of a young woman who had entered therapy because her parents were concerned that she was a lesbian. Her father hoped that psychoanalysis would cure her lesbianism, but in Freud‘s view, the prognosis was unfavourable because of the circumstances under which the woman entered therapy, and because homosexuality was not an illness or neurotic conflict. Freud wrote that changing homosexuality was difficult and therefore possible only under unusually favourable conditions, observing that “in general to undertake to convert a fully developed homosexual into a heterosexual does not offer much more prospect of success than the reverse.” Success meant making heterosexual feeling possible rather than eliminating homosexual feelings.

Gay people could seldom be convinced that sex with someone of the opposite sex would provide them with the same pleasure they derived from sex with someone of the same sex. Patients often had only superficial reasons to want to become heterosexual, pursuing treatment due to social disapproval, which was not a strong enough motive for change. Some patients might have no real desire to become heterosexual, seeking treatment only so that they could convince themselves that they had done everything possible to change, leaving them free to return to homosexuality afterwards. Freud therefore told the parents only that he was prepared to study their daughter to determine what effects therapy might have. Freud concluded that he was probably dealing with a case of biologically innate homosexuality, and eventually broke off the treatment because of what he saw as his patient's hostility to men.

In 1935, Freud wrote a mother who had asked him to treat her son a letter that later became famous:

I gather from your letter that your son is a homosexual. I am most impressed by the fact that you do not mention this term yourself in your information about him. May I question you why you avoid it? Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation; it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function, produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. Many highly respectable individuals of ancient and modern times have been homosexuals, several of the greatest men among them. (Plato, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, etc). It is a great injustice to persecute homosexuality as a crime –and a cruelty, too. If you do not believe me, read the books of Havelock Ellis.

By asking me if I can help , you mean, I suppose, if I can abolish homosexuality and make normal heterosexuality take its place. The answer is, in a general way we cannot promise to achieve it. In a certain number of cases we succeed in developing the blighted germs of heterosexual tendencies, which are present in every homosexual; in the majority of cases it is no more possible. It is a question of the quality and the age of the individual. The result of treatment cannot be predicted.

What analysis can do for your son runs in a different line. If he is unhappy, neurotic, torn by conflicts, inhibited in his social life, analysis may bring him harmony, peace of mind, full efficiency, whether he remains homosexual or gets changed.

Isidor Sadger

Isidor Sadger published “Fragment der Psychoanalyse eines Homosexuellen” in the Jahrbuch fuer sexuellen Zwischenstufen in 1908. It described his analysis of a melancholy Danish count who was homosexual. The analysis lasted for only thirteen days before being terminated by the patient, whose sexual orientation was not changed. Later in 1908, Sadger published “Ist der Kontraere sexual Empfindung heilbar?”, which assessed the value of psychoanalysis as a treatment for “contrary sexual feeling“, in the Zeitschrift fuer Sexualwissenschaft. He answered the question of whether it could be cured in patients who were moral and determined “mit einem runden Ja!“ (“with a round Yes!“). Sadger believed that it was not enough to establish a spurious kind of heterosexual functioning or “masturbatio per vaginam”, wanting instead to change a patient’s “Sexualideal”, the internal image of his sexual object.“

Sadger supported his claim that homosexuality could be cured entirely by describing a four month analysis of a patient whose crucial memories “had been wholly unconscious and first had to be unearthed very laboriously through a month-long analysis.“ Making striking claims about homosexuality on the basis of brief analyses appears to have been typical for psychoanalysts in the early 20th century. The material Sadger’s patients produced appears to have been influenced by his expectations. Sadger claimed that a homosexual orientation was a displacement of a prior heterosexual nature, offering as proof a patient who was apparently entirely homosexual but who started having heterosexual masturbation fantasies in the tenth day of analysis. Sadger permitted his patients to engage in homosexual activity during treatment because of his belief that "behind it, a heterosexual can again be found."

Freud stated in a note in his revised 1910 edition of “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality” that his conclusions about homosexuality were partly based on information obtained from Sadger. Sadger’s main work, Die Lehre von den Geschlechtsverwirrugen . . . auf psychoanalytischer Grundlage was published in 1921. Sadger usually argued that homosexuality was due to accidental family events, but for unclear reasons he frequently reported family histories of sexual inversion. Sadger followed Freud’s idea that gay men unconsciously desire to castrate their fathers by rendering their male partners flaccid through orgasm so that they can magically incorporate their masculinity and finally obtain access to the mother.

Sandor Ferenczi

Sandor Ferenczi was an influential psychoanalyst. Native to Hungary, he wrote many of his works in German.

Ferenczi denied the importance of inherited factors on homosexuality, claiming that it was caused by “excessively powerful heterosexuality (intolerable to the ego)“. Ferenczi tried to distinguish between several different types of homosexuality, basing his distinctions on an unspecified number of patients whose analyses had sometimes lasted for a short period and sometimes “a whole year and even longer.” Ferenczi hoped to cure some kinds of homosexuality completely, but was content in practice with reducing what he considered gay men‘s hostility to women, along with the urgency of their homosexual desires, and with helping them to become attracted to and potent with women. In his view, a gay man who was confused about his sexual identity and felt himself to be “a woman with the wish to be loved by a man” was not a promising candidate for cure. Ferenczi believed that complete cures of homosexuality might become possible in the future when psychoanalytic technique had been improved. Sandor Rado and Melanie Klein were pupils of Ferenczi.

Edmund Bergler

Edmund Bergler’s first contribution to the psychoanalytic theory of homosexuality was “Der Mammakomplex des Mannes“, an article co-authored with L. Eidelberg and published in the Internationale Zeitschrift fuer Psychoanalyse in 1933. It described a “breast complex“ found in both normal and pathological conditions, among which Eidelberg and Bergler included “a type of homosexuality.” The male child reacts violently to weaning, making unsuccessful attempts to inhibit his frustrated aggression that only heighten it. This causes ambivalent identifications, object choices, and narcissistic compensations. Cathexes are displaced from the breast onto the penis, and the infant substitutes urine for milk, attempting to make active what was once passive. He unsuccessfully tries to transfer hatred of the mother onto the father, but the Oedipus complex does not reach normal intensity because of the unresolved ambivalence of the oral period. The unstable organization achieve at the Oedipal period regresses to an earlier stage involving fixation on the oral mother, whose vagina is conflated with the infant‘s own cannibalistic mouth, transmuting it into the vagina dentata. This oral fixation lead to character traits such as spite and libido charged with aggression.

France

Jean-Martin Charcot, a French neurologist and professor of anatomical pathology, attempted in the 19th century to cure homosexuality through hypnosis. The failure of his attempts convinced him that homosexuality was inherited. J. Vinchon and Sacha Nacht in 1929 published "Considerations sur la cure psychoanalytique d’une nevrose homosexuelle" in Revue francaise de psychoanalyse. This article divided gay people into three categories: those with glandular abnormalities, sexual perverts, and neurotics. Vinchon and Nacht believed that gay people in the second category (who were "comfortably settled in vice") were incurable. Daniel Lagache in 1950 published “Homosexuality and Jealousy” in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. It described the analysis of a gay man, illustrating the relation of active and passive forms of homosexuality and the defensive maneuvers that mediate between them. The patient shifted from homosexual to heterosexual interests, and experienced a stage of intense jealousy that Lagache regarded as both a sign of progress and a resistance. The heterosexual interest was a new defense against passive homosexuality, while active homosexuality had been his old defense. Passive homosexuality was intolerable to the patient because it was associated with castration, but it was deeply rooted in his psychology because “submission and obedience to the father as their aim the right to take his place.”

Germany

Albert von Schrenck-Notzing

Baron Albert von Schrenck-Notzing was a German physician and occultist. Historian Jonathan Katz writes that Schrenck-Notzing was the first person to attempt to treat homosexuality with hypnosis. His book Therapeutic Suggestion in Psychopathia Sexualis appeared in an American edition in English in 1895.

Magnus Hirschfeld

The leader of the gay rights movement in Germany in the early 20th century was the physician Magnus Hirschfeld. In 1896, Hirschfeld moved to Berlin and published Sappho and Socrates, a pamphlet that explained the development of sexual orientation in terms of the bisexual nature of the fetus. Hirschfeld was influenced by the earlier work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, but mentioned him only briefly. He argued that the brain contained centers governing attraction to men and women. In most male foetuses, the center governing attraction to women developed, while in most female foetuses, the center governing attraction to men developed. When the opposite processes occurred, the outcome was homosexuality. Hirschfeld displayed an ambivalent attitude to homosexuality, believing that it might be caused by biological degeneracy (owing to alcoholism or syphilis) in some cases. He repeatedly compared homosexuality to deformities such as having a hare lip, regarding the main difference between these conditions as being that the former could not be corrected, while the latter could.

Hirschfeld in 1903 published Der Urnische Mensch, which presented his mature views on homosexuality. Hirschfeld argued that the purpose of therapy should be to permit clients to accept their homosexuality, but accepted that gay men had the right to attempt to change their sexual orientation if they wished and recommended them to practitioners who claimed that they could accomplish this. These practitioners included Isidor Sadger and Eugen Steinach. James D. Steakley states that Hirschfeld directed a gay man to Steinach on only one occasion, while Simon LeVay states that he did this on numerous occasions. Hirschfeld believed that the failure of attempts to change homosexuality through psychoanalysis proved that it was biologically innate. Hirschfeld founded and edited the Jahrbuch fur sexuelle Zwischenstufen, a sexological journal which was published annually between 1899 and 1923.

Felix Boehm

German psychoanalysts who wrote about homosexuality included Felix Boehm. He accepted Freud’s earlier theory of homosexuality involving boys’ identification with their mothers and consequent narcissistic object choice. His major work was a four-part series on homosexuality published in the Internationale Zeitschrift fuer Psychoanalyse between 1920 and 1933. It attempted to present and illustrate the most up to date psychoanalytic thinking on homosexuality. In Boehm’s view, curing homosexuality meant making enjoyable heterosexual functioning possible rather than eliminating homosexual behavior. Boehm claimed to have cured gay people in the fourth part of his series on homosexuality, but presented as proof a case in which “the homosexuality never became conscious for the patient and had never expressed itself in manifest activity.” This patient does not appear to have been homosexual. Boehm claimed that manifest homosexuals regularly abandoned treatment out of hatred for their analysts just at the point when they were close to achieving heterosexual functioning. Boehm criticised Sadger’s Die Lehre von den Geschlechtsverwirrugen ... auf psychoanalytischer Grundlage for its brief analyses, many of which lasted only weeks or months.

National Socialism

In the 1930s, the rise to power of Nazism in Germany destroyed the gay rights movement. Hirschfeld was unable to return to Germany from a world tour because of growing political disorder in 1931 and 1932. He was obliged to move to France, where he made an unsuccessful attempt to establish a new sexological institute. Approximately fifty thousand people were convicted of homosexuality during Nazi rule, and roughly five thousand were sent to concentration camps, where most of them died. In 1944, the Danish endocrinologist Carl Vaernet carried out medical experiments on gay men at Buchenwald concentration camp. He implanted “artifical sex glands“ designed to release testosterone into at least ten gay men to attempt to change their sexual orientation. The experiments caused at least one man to die, but Vaernet claimed that some of them had been successful. These apparent changes in sexual orientation were probably the result of prisoners lying in attempts to be discharged from the camp. In 1945, Vaernet was arrested, but he managed to escape to Argentina.

Gunter Dorner

During the 1960s and 1970s, the endocrinologist Gunter Dorner, who was influenced by Eugen Steinach through his teacher Walter Hohlweg, performed experiments on rats designed to alter their sexual behavior. He reported that the destruction of the ventromedial nucleus in apparently homosexual rats caused them to become heterosexual. Dorner suggested that homosexuality in humans was caused by hormonal factors and should be cured or prevented. In 1962, Fritz Roeder, a neurosurgeon at the University of Gottingen, destroyed the ventromedial nucleus of of a 52 year old man who was in prison for having sex with numerous boys between the ages of 12 and 14. He volunteered for the operation as an alternative to castration. It reduced his homosexual feelings but did not cause him to develop heterosexual feelings. Nearly forty other men were later subjected to the same operation. The men the operations were performed on were all in prison or hospitals for the criminally insane. Some of them were heterosexual rapists, while others were labelled homosexual pedophiles, although most of their offences were committed with post-pubertal youths. The operations usually caused reduction in sexual desire, with obesity as a common side-effect. Some of the operations were performed by Roeder and others by a different group of German scientists lead by Gert Dieckmann and R. Hassler. The Dieckmann and Hassler group acknowledged that Dorner’s work had provided scientific background for their surgery. Roeder claimed in 1970 that he had changed the sexual orientation of his patients from pedophilic to heterosexual.

Dorner suggested in his 1976 book Hormones and Brain Differentiation that homosexuality might be cured through brain surgery. He criticised the use of castration and steroids to change human sexual orientation, stating that they could only alter the strength of sexual attraction, not its direction.

The German Society for Sex Research criticised Dorner‘s research on scientific and moral grounds in 1982.

Recent developments

Following the increased visibility of the gay community during the AIDS epidemic of the late 1980s and the declassification of homosexuality as a mental disorder in the ICD-10, non-pathological models of homosexuality became mainstream. Nevertheless, Robert L. Spitzer‘s study of sexual orientation change, conducted in 2001, quickly attracted attention in Germany. German opponents of civil unions used the study to support their view that the relationships of gay men and lesbians should not be legally recognized. The Suddeutsche Zeitung on May 15, 2001 published an interview with Hartmut Bosinski, the Head of the Department of Sexual Medicine at the University of Kiel and a supporter of civil unions. Bosinski criticised the Spitzer study. Civil unions were passed into law on July 17, 2002 despite the controversy. In 2008, Bundestag, the parliament of Germany, ruled that homosexuality does not require therapy and cannot be changed through therapy. It also stated that conversion therapy has harmed gay people and is dangerous.

United Kingdom

19th century

The Journal of Mental Science in 1896 published an article by sexologist Havelock Ellis and Dr E. S. Talbot about the attempted treatment of homosexuality in an American patient named Guy Olmstead through castration. Following the operation, which did not change his sexual orientation, Olmstead attempted to murder a man he had had a relationship with and was sent to an insane asylum. Ellis and Talbot suggested that the moral of the case was that, “The removal of the testicles, the apparently depressing effect of the operation, and the speedy occurrence of the crime after it, should suggest caution to the surgical psychiatrists who advocate the castration of inverts and sexual perverts generally“.

Melanie Klein

The Austrian-born psychoanalyst Melanie Klein moved to London in 1926. Her seminal book The Psycho-Analysis of Children, based on lectures given to the British Psychoanalytic Society in the 1920s, was published in 1932. Klein claimed that entry into the Oedipus Complex is based on mastery of primitive anxiety from the oral and anal stages. If these tasks are not performed properly, developments in the Oedipal stage will be unstable. Complete analysis of patients with such unstable developments would require uncovering these early concerns. The analysis of homosexuality required dealing with paranoid trends based on the oral stage. The Psycho-Analysis of Children ends with the analysis of Mr. B., a gay man. Klein claimed that he illustrated pathologies that enter into all forms of homosexuality: a gay man idealizes “the good penis” of his partner to ally the fear of attack he feels due to having projected his paranoid hatred onto the imagined “bad penis“ of his mother as an infant. She stated that Mr. B.’s homosexual behaviour diminished after he overcame his need to adore the “good penis” of an idealized man. This was made possible by his recovering his belief in the good mother and his ability to sexually gratify her with his good penis and plentiful semen.

Anna Freud

Daughter of Sigmund Freud, Anna Freud became an influential psychoanalytic theorist in the UK after she left Austria in 1938 to escape the Nazis.

Anna Freud reported the successful treatment of homosexuals as neurotics in a series of unpublished lectures. In 1949 she published “Some Clinical Remarks Concerning the Treatment of Cases of Male Homosexuality” in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis. In her view, it was important to pay attention to the interaction of passive and active homosexual fantasies and strivings, the original interplay of which prevented adequate identification with the father. The patient should be told that his choice of a passive partner allows him to enjoy a passive or receptive mode, while his choice of an active partner allows him to recapture his lost masculinity. She claimed that these interpretations would reactive repressed castration anxieties, and childhood narcissistic grandiosity and its complementary fear of dissolving into nothing during heterosexual intercourse would come with the renewal of heterosexual potency.

Anna Freud in 1951 published “Clinical Observations on the Treatment of Male Homosexuality” in Psychoanalytic Quarterly and “Homosexuality” in the American Psychoanalytic Association Bulletin. These articles insisted on the attainment of full object-love of the opposite sex as a requirement for cure of homosexuality. In 1951 she gave a lecture about treatment of homosexuality which was criticised by Edmund Bergler, who emphasised the oral fears of patients and minimized the importance of the phallic castration fears she had discussed.

Anna Freud recommended in 1956 to a journalist who was preparing an article about psychoanalysis for the London Observer that she not quote Freud‘s letter to the American mother, on the grounds that “…nowadays we can cure many more homosexuals than was thought possible in the beginning. The other reason is that readers may take this as a confirmation that all analysis can do is to convice patients that their defects or ‘immoralities‘ do not matter and that they should be happy with them. That would be unfortunate.”

Alan Turing

The British government in 1952 subjected Alan Turing to hormonal treatment after he was arrested on a charge of gross indecency. The treatments took the form of oestrogen injections, which were effectively chemical castration. Turing became overweight and developed breasts as a side-effect of the treatment, then became depressed and eventually killed himself.

Hans Eysenck

Hans Eysenck was born in Berlin, Germany, but moved to England as a young man in the 1930s because of his opposition to the Nazi party.

He was notable as being one of the three most influential psychiatrists of the 20th Century and helped develop behavioural therapy. He advocated using Electroconvulsive Therapy to treat homosexuals, as well as aversion therapy, and claimed half were cured. On November 2nd 1972 Peter Tatchell of the UK Gay Liberation Front invaded a closed meeting where Eysenck was speaking, Tatchell disputed that 50% of those treated were cured, questioned whether what happened was cure, and asked about the other 50%. Eysenk conceded that the success rate was not high, but "dismissed concerns about the pain and danger involved as a fuss over nothing. 'Aversion therapy is', he said, 'just like a visit to the dentist'".

Recent developments

Peel, Clarke and Drescher wrote in 2007 that only one organisation in the UK could be identified with conversion therapy, a religious organisation called The Freedom Trust (part of the US-based Exodus International): "whereas a number of organisations in the US (both religious and scientific/psychological) promote conversion therapy, there is only one in the UK of which we are aware". The paper reported that practitioners who did provide these sorts of treatments between the 1950s and 1970's now view homosexuality as healthy, and the evidence suggests that 'conversion therapy' is a historical rather than a contemporary phenomenon in the UK, where treatment for homosexuality has always been less common than in the USA.

In 2007, the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the main professional organization of psychiatrists in the United Kingdom, issued a report stating that: "Evidence shows that LGB people are open to seeking help for mental health problems. However, they may be misunderstood by therapists who regard their homosexuality as the root cause of any presenting problem such as depression or anxiety. Unfortunately, therapists who behave in this way are likely to cause considerable distress. A small minority of therapists will even go so far as to attempt to change their client's sexual orientation. This can be deeply damaging. Although there is now a number of therapists and organisation in the USA and in the UK that claim that therapy can help homosexuals to become heterosexual, there is no evidence that such change is possible."

In 2008, the Royal College of Psychiatrists stated: "The Royal College shares the concern of both the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association that positions espoused by bodies like the National Association for Research and Therapy of Homosexuality (NARTH) in the United States are not supported by science. There is no sound scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed. Furthermore so-called treatments of homosexuality as recommended by NARTH create a setting in which prejudice and discrimination can flourish."

In 2009, a research survey into mental health practitioners in the UK concluded "A significant minority of mental health professionals are attempting to help lesbian, gay and bisexual clients to become heterosexual. Given lack of evidence for the efficacy of such treatments, this is likely to be unwise or even harmful." Scientific American reported on this: "One in 25 British psychiatrists and psychologists say they would be willing to help homosexual and bisexual patients try to convert to heterosexuality, even though there is no compelling scientific evidence a person can willfully become straight", and explained that 17% of those surveyed said they had tried to help reduce or suppress homosexual feelings, and 4% said they would try to help homosexual people convert to heterosexuality in the future.

United States

19th century

Methods used to treat homosexuality in the 19th century included "anaphrodisiac measures", surgical removal of the ovaries, castration, and hypnosis. Descriptions of such treatments were published in medical journals. In 1884 Dr. James G. Kiernan surveyed early writings on homosexuality, from America, Germany, and other countries. He described his treatment of a lesbian patient, stating that removing her homosexuality was out of the question, but that he had been able to help her keep it under control. F. E. Daniel proposed castration of gay men in 1893, while Dr. Henry Hulst proposed hypnosis as an alternative method, becoming the first American known to have supported this form of conversion therapy. Dr. John C. Quackenbos in 1899 reported on the use of hypnosis as a treatment for sexual perversion to the New Hampshire Medical Society. He stated that its success depended on the patient's desire to be cured. Quackenbos received publicity when the New York Times reported on his work.

20th century

Surgical methods of treating homosexuality continued to be used in the 20th century. Psychoanalysis started to receive recognition in the United States in 1909, when Sigmund Freud delivered a series of lectures at Clark University in Massachusetts at the invitation of G. Stanley Hall.

Abraham Brill in 1913 wrote “The Conception of Homosexuality”, which he published in the Journal of the American Medical Association and read before the American Medical Association’s annual meeting, where it was criticised by several doctors. Brill declared that after long study he had slowly overcome his disgust for homosexuality. He denied that homosexuality was influenced by inherited factors or necessarily related to emotional disturbance. Brill observed that it was impossibile to use the term homosexuality diagnostically, since it could refer to several different entities. Brill asserted that the development of sexual attraction to the same sex was always related to narcissism, which he incorrectly defined as love for one‘s self. Brill criticised physical treatments for homosexuality such as bladder washing, rectal massage, and castration, along with hypnosis, but referred approvingly to Freud and Sadger's use of psychoanalysis, calling its results “very gratifying.“ Since Brill understood cure of homosexuality to mean restoring heterosexual potency, he claimed that he had cured his patients in several cases, even though many remained homosexual.

Dr. Wilhelm Stekel, an Austrian, published his views on treatment of homosexuality, which he considered a disease, in the American Psychoanalytic Review in 1930. Stekel believed that “success was fairly certain“ in changing homosexuality through psychoanalysis provided that it was performed correctly and the patient wanted to be treated. In 1932, the Psychoanalytic Quarterly published a translation of Dr. Helene Deutsch's paper “On Female Homosexuality“. Deutsch reported her analysis of a lesbian, who did not become heterosexual as a result of treatment, but who managed to achieve a "positive libidinal relationship" with another woman. Deutsch indicated that she would have considered heterosexuality a better outcome.

Dr. La Forest Potter of New York City published Strange Loves: A Study in Sexual Abnormalities, which focused on homosexuality, in 1933, probably to exploit the interest in the subject generated by the American publication of Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Blair Niles’s Strange Brother. He believed that homosexuality was caused by psychological and hormonal disturbances, and that it could be cured if the patient wanted to change. Potter advocated a mixture of psychoanalysis and hormone treatment. He believed that marriage might help to alter lesbianism in cases in which it was not hereditary. Potter described his treatment of two lesbians, stating that it was unsuccessful in one case but successful in the other. He stated that he had successfully cured a young man of homosexuality.

Dr. Louis W. Max reported to the American Psychological Association on September 6, 1935 that he had used electric shocks administered over several months to diminish what he called a homosexual fixation in a patient. This was the first documented attempt to use aversion therapy to alter homosexuality. He stated that low intensity shocks had no effect, but that higher intensities "definitely diminished the emotional value of the stimulus for days after each experimental period."

Edmund Bergler moved to the USA after vacating his post as psychoanalyst in Vienna in 1937. He published “Preliminary Phases of the Masculine Beating Fantasy“, a response to Freud‘s “A Child Is Being Beaten“, in Psychoanalytic Quarterly in 1938. Bergler claimed to have detected the early phase of a beating fantasy in boys. This phase began with the weaning shock, which mobilizes enormous sadistic rage against the breasts of the depriving phallic mother, which is an attempt at narcissistic restitution for the lost breasts of the mother. Due to guilt, this rage is transmuted into a masochistic fantasy of being beaten by the father, substituting the boy’s own buttocks for the mother’s breasts and idealizing the father out of hatred of the mother, thereby substituting a homosexual for a heterosexual bond. The paper shifted the important stage in the development of homosexual perversion back from the Oedipus complex to the oral stage, minimized the importance of object libido and emphasised more primitive narcissistic oral rage, and established that homosexual perversion could not be based on a primary homosexual attachment to the father, since there was always an earlier heterosexual attachment to the mother. The implication was that all outcomes of the Oedipus complex involving a passive homosexual stance toward the father are perverse.

During the three decades between Freud's death in 1939 and the Stonewall riots in 1969, conversion therapy received approval from most of the psychiatric establishment in the United States. Sandor Rado in 1940 criticized Freud's theory of innate bisexuality in his article "A Critical Examination of the Concept of Bisexuality". Rado concluded that pursuing the genital organs of the opposite sex is the standard form of achieving genital stimulation and that the main cause of homosexuality is anxiety, although he granted that "constitutional factors may have an influence on morbid sex developments." Rado‘s article appears to have been partly motivated by the desire to combat homosexuality.

Bergler was the most important psychoanalytic theorist of homosexuality in the 1950s. He was vociferous in his opposition to Alfred Kinsey, who argued that homosexuality was normal human variation. Bergler argued that Kinsey's statistical research overestimated the incidence of homosexuality because it was conducted in cities where perversion thrived. Bergler based his theories partly on analysis of the novels of literary figures known to be gay. Kinsey's work, and its reception, led Bergler to develop his own theories for treatment, which were essentially to 'blame the victim'.

Bergler claimed that if gay people wanted to change, and the right therapeutic approach was taken, then they could be cured in 90% of cases. Bergler used confrontational therapy in which gay people were punished in order to make them aware of their masochism. Bergler openly violated professional ethics to achieve this, breaking patient confidentiality in discussing the cases of patients with other patients, bullying them, calling them liars and telling them they were worthless. He insisted that gay people could be cured, and that if they believed they should be accepted, they were asking for punishment, which confirmed their pathological immaturity. Bergler initially blamed those who mistreated gay people, because it provided a rationale for the masochistic view of the world; but, from the 1950s, and following the emergence of gay rights organisations, he began to blame homosexuals for their own oppression. Bergler confronted Kinsey because Kinsey thwarted the possibility of cure by presenting homosexuality as an acceptable way of life, which was the basis of the homosexual rights activism of the time. Bergler popularised his views on homosexuality and its cure in the USA in the 1950's using magazine articles and books aimed at non-specialists.

In 1951, the mother who wrote to Freud asking him to treat her son sent Freud's response to the American Journal of Psychiatry, in which it was published. The 1952 first edition of the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I) classified homosexuality as a mental disorder.

The practice of aversion therapy was influenced by "Treatment of Male Homosexuality through Conditioning", an article published by the Czech doctors J. Srnec and Kurt Freund in the International Journal of Sexology in 1953. Srnec and Freund‘s procedure, conducted in Czechoslovakia, involved giving patients coffee or tea mixed with emetine, then subcutaneous injections with a mixture of substances, before showing them pictures of nude men while the drugs made them vomit. Patients were next shown pictures of women after being injected with testosterone. This was repeated between five to ten times per patient. Srnec and Freund stated that of twenty five men who were subjected to this procedure, ten “achieved predominant heterosexuality at practically full sexual activity.” They expressed the hope that the method they described could eventually be replaced by something more effective.

The homosexuality as sickness theory started to come under criticism in the 1950s. Evelyn Hooker in 1957 pulished “The Adjustment of the Male Overt Homosexual”, which found that "homosexuals were not inherently abnormal and that there was no difference between homosexual and heterosexual men in terms of pathology." This paper subsequently became influential. Irving Bieber and his colleagues in 1962 published Homosexuality: A Psychoanalytic Study of Male Homosexuals, which concluded that "although this change may be more easily accomplished by some than by others, in our judgment a heterosexual shift is a possibility for all homosexuals who are strongly motivated to change." The same year, Albert Ellis published Reason and Emotion in Psychotherapy, which claimed that "fixed homosexuals in our society are almost invariably neurotic or psychotic:... therefore, no so-called normal group of homosexuals is to be found anywhere." Ellis published his main work on homosexuality, Homosexuality: Its Causes and Cure, in 1965."

Psychologist Martin E.P. Seligman reported in 1966 that using aversion therapy to change sexual orientation "worked surprisingly well," with up to 50% of men subjected to such therapy not acting on their homosexual urges. These results produced "a great burst of enthusiasm about changing homosexuality swept over the therapeutic community". The findings were later shown to be flawed: most of the treated men who stopped having sex with men were actually bisexual. Among men who were primarily gay, aversion therapy was far less successful.

Charles Socarides’s first book, The Overt Homosexual, was published in 1968. Socarides regarded homosexuality as an illness arising from a conflict between the id and the ego usually arising from an early age in "a female-dominated environment wherein the father was absent, weak, detached or sadistic". He credited the earlier work of Irving Bieber with clarifying progress in therapeutic knowledge and effectivenes.

There was a riot in 1969 at the Stonewall Bar in New York after a police raid. The Stonewall riot acquired symbolic significance for the gay rights movement and came to be seen as the opening of a new phase in the struggle for gay liberation. Following these events, conversion therapy came under increasing attack. Activism against conversion therapy increasingly focused on the DSM's designation of homosexuality as a psychopathology.

Lawrence Hatterer in 1970 published Changing Homosexuality in the Male, which advocated a therapy based on simplified psychoanalytic ideas and behavior modification techniques. 1970 also saw the publication of Arthur Janov's The Primal Scream, which claimed that homosexuality was a neurosis that could be cured by a therapy that used screaming and other methods in attempts to release repressed pain. The Gay Liberation Front invaded Janov's office in West Hollywood, and had a "scream-in" to protest his anti-gay writings. Janov's therapy later became widely influential.

In 1973, after years of criticism from gay activists and bitter dispute among psychiatrists, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality as a mental disorder from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Supporters of the change used evidence from researchers such as Alfred Kinsey and Evelyn Hooker. Psychiatrst Robert Spitzer, a member of the APA's Committee on Nomenclature, played an important role in the events that lead to this decision. Critics argued that it was a result of pressure from gay activists, and demanded a referendum among voting members of the Association. The referendum was held in 1974 and the APA’s decision was upheld by a 58% majority.

Exodus International, a Christian organization that promotes "the message of freedom from homosexuality through the power of Jesus Christ", was founded in 1976. It does not conduct clincal treatment but does provide referrals to professional therapists.

Robert Kronemeyer in 1980 published Overcoming Homosexuality. Influenced by the work of Wilhelm Reich, Kronemeyer claimed that homosexuality could be cured by a method he called "Syntonic Therapy." Kronemeyer criticised some earlier methods of changing homosexuality, including lobotomy, electroshock treatment, and Aesthetic Realism.

Research psychologist Elizabeth Moberly in 1983 published Homosexuality: A New Christian Ethic, which tried to understand homosexuality through a combination of psychological theory and theology. It used the term reparative drive to refer to male homosexuality, interpreting men's sexual desires for other men as attempts to compensate for a lacked connection between father and son during childhood. Moberly denied the importance of over-dominant mothers as a cause of homosexuality and encouraged same-sex bonding with both mentors and peers as a way of stopping same-sex attraction.

The APA removed ego-dystonic homosexuality from the DSM-IV in 1987 and opposes the diagnosis of either homosexuality or ego-dystonic homosexuality as any type of disorder.

Joseph Nicolosi began playing an important role in the development of conversion therapy in the early 1990s, publishing his first book Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality in 1991. In 1992, Joseph Nicolosi, Charles Socarides, and Benjamin Kaufman founded the National Association for Research & Treatment of Homosexuality (NARTH), a mental health organization that opposes the mainstream medical view of homosexuality and aims to "make effective psychological therapy available to all homosexual men and women who seek change."

21st century

United States Surgeon General David Satcher in 2001 issued a report stating that "there is no valid scientific evidence that sexual orientation can be changed". The same year, Robert Spitzer's study on sexual orientation change caused controversy and attracted media attention.

The American Psychoanalytic Association (APsaA) spoke against NARTH in 2004, stating "that organization does not adhere to our policy of nondiscrimination and ... their activities are demeaning to our members who are gay and lesbian." In 2006, Focus on the Family and several other organizations announced that they would protest the American Psychological Association's convention in New Orleans. Mike Haley, the director of gender issues for Focus on the Family, commented that, "The APA's views on issues such as the immutability of homosexuality have caused real harm to real people and patients." The same year, a survey of members of the American Psychological Association rated reparative therapy as "certainly discredited", though the authors warn that the results should be interpreted carefully as an initial step, not a final word.

The American Psychological Association in 2007 convened a task force to evaluate its policies regarding reparative therapy; ex-gay organizations expressed concerns about the lack of representation of pro-reparative-therapy perspectives on the task force, while alleging that anti-reparative-therapy perspectives were amply represented.

In 2008, the organizers of an APA panel on the relationship between religion and homosexuality canceled the event after gay activists objected that "conversion therapists and their supporters on the religious right use these appearances as a public relations event to try and legitimize what they do."

In 2009, American Psychological Association stated that it "encourages mental health professionals to avoid misrepresenting the efficacy of sexual orientation change efforts by promoting or promising change in sexual orientation when providing assistance to individuals distressed by their own or others’ sexual orientation and concludes that the benefits reported by participants in sexual orientation change efforts can be gained through approaches that do not attempt to change sexual orientation".

Contemporary theories and techniques

Behavioral modification

Practitioners who view homosexuality as learned behavior may adopt behavioral modification techniques. These may include masturbatory reconditioning, visualization, and social skills training. The most radical involve electroconvulsive therapy, a form of aversion therapy.

Joseph Nicolosi's reparative therapy

Joseph Nicolosi in 1991 published Reparative Therapy of Male Homosexuality: A New Clinical Approach. This book introduced reparative therapy as a term for psychotherapeutic attempts to convert gay people to heterosexuality. Nicolosi was influenced by numerous sources, including Moberly's earlier work on the development of male gender-identity.

Douglas C. Haldeman has identified Nicolosi as the leading representative of the theory that same-sex desires are a form of arrested psychosexual development, resulting from "an incomplete bond and resultant identification with the same-sex parent, which is then symbolically repaired in psychotherapy". Nicolosi’s intervention plans involve conditioning a man to a traditional masculine gender role. He should "(1) participate in sports activities, (2) avoid activities considered of interest to homosexuals, such art museums, opera, symphonies, (3) avoid women unless it is for romantic contact, (4) increase time spent with heterosexual men in order to learn to mimic heterosexual male ways of walking, talking, and interacting with other heterosexual men, (5) Attend church and join a men’s church group, (6) attend reparative therapy group to discuss progress, or slips back into homosexuality, (7) become more assertive with women through flirting and dating, (8) begin heterosexual dating, (9) engage in heterosexual intercourse, (10) enter into heterosexual marriage, and (11) father children".

Most mental health professionals consider reparative therapy discredited, but it is still practiced by some professionals. Psychoanalysts critical of Nicolosi's theories have offered gay-affirmative approaches as an alternative to reparative therapy. Exodus International regards reparative therapy as a useful tool to eliminate "unwanted same-sex attraction."

Richard Cohen's bioenergetics

Richard Cohen has been called one of America's leading practitioners of conversion therapy. Cohen holds male patients in his lap with the patient curled into the fetal position, and also advocates bioenergetic methods influenced by Alexander Lowen and John Pierrakos, who were students of Wilhelm Reich. These methods can involve shouting or slamming a pillow with a tennis racket.

Studies of conversion therapy

Shidlo and Schroeder study

Ariel Shidlo and Michael Schroeder found in "Changing Sexual Orientation: A Consumer's Report", a peer-reviewed study published in 2002, that 88% of participants failed to achieve a sustained change in their sexual behavior and 3% reported changing their orientation to heterosexual. The remainder reported either losing all sexual drive or attempting to remain celibate, with no change in attraction. Some of the participants who failed felt a sense of shame and had gone through conversion therapy programs for many years. Others who failed believed that therapy was worthwhile and valuable. Shidlo and Schroeder also reported that many respondents were harmed by the attempt to change. Of the 8 respondents (out of a sample of 202) who reported a change in sexual orientation, 7 worked as ex-gay counselors or group leaders.

Spitzer study

See also: LGBT rights in FinlandIn May 2001, Dr. Robert Spitzer presented "Can Some Gay Men and Lesbians Change Their Sexual Orientation? 200 Participants Reporting a Change from Homosexual to Heterosexual Orientation", a study of attempts to change homosexual orientation through ex-gay ministries and conversion therapy, at the American Psychiatric Association's convention in New Orleans. The study was partly a response to the APA's 2000 statement cautioning against clinical attempts at changing homosexuality, and was aimed at determining whether such attempts were ever successful rather than how likely it was that change would occur for any given individual. Spitzer wrote that some earlier studies provided evidence for the effectiveness of therapy in changing sexual orientation, but that all of them suffered from methodological problems.

He reported that after intervention, 66% of the men and 44% of the women had achieved "Good Heterosexual Functioning", which he defined as requiring five criteria (being in a loving heterosexual relationship during the last year, overall satisfacition in emotional relationship with a partner, having heterosexual sex with the partner at least a few times a month, achieving physical satisfaction through heterosexual sex, and not thinking about having homosexual sex more than 15% of the time while having heterosexual sex). He found that the most common reasons for seeking change were lack of emotional satisfaction from gay life, conflict between same-sex feelings and behavior and religious beliefs, and desire to marry or remain married. This paper was widely reported in the international media and taken up by politicians in the United States, Germany, and Finland, as well as by conversion therapists.

In 2003, Spitzer published the paper in the Archives of Sexual Behavior. Spitzer's study has been criticized on numerous ethical and methodological grounds. Gay activists argued that the study would be used by conservatives to undermine gay rights. Researchers observed that the study sample consisted of people who sought treatment primarily because of their religious beliefs, and who may therefore have been motivated to claim that they had changed even if they had not, or to overstate the extent to which they might have changed. That participants had to rely upon their memories of what their feelings were before treatment may have distorted the findings. It was impossible to determine whether any change that occurred was due to the treatment because it was not clear what it involved and there was no control group. Claims of change may have reflected a change in self-labelling rather than of underlying orientation or attractions, and particpants may have been bisexual before treatment. Follow-up studies were not conducted. Spitzer stressed the limitations of his study. Spitzer said that the number of gay people who could successfully become heterosexual was likely to be "pretty low". He also conceded that the study's participants were "unusually religious."

Yarhouse and Throckmorton study

Mark Yarhouse and Warren Throckmorton, of the private Christian school Grove City College, argue in "Ethical Issues in Attempts to Ban Reorientation Therapies" that conversion therapy should be available out of respect for a patient’s values system and because there is evidence that it can be effective. They state that studies from the 1950s–1980s generally reported rates of positive outcomes at about 30%, with more recent survey research generally consistent with the extant data. Yarhouse and Throckmorton's 2002 paper was partly a response to Jack Drescher's 2001 paper, "Ethical issues surrounding attempts to change sexual orientation", which used the principle of "Do no harm" to argue against conversion therapy.

Medical, scientific and legal views

Further information: ]American medical consensus

The medical and scientific consensus in the United States is that conversion therapy is potentially harmful, but that there is no scientifically adequate research demonstrating either its effectiveness or harmfulness. The American Psychiatric Association supports research into its possible risks and benefits. Mainstream medical bodies state that conversion therapy can be harmful because it may exploit guilt and anxiety, thereby damaging self-esteem and leading to depression and even suicide. Participants are at increased risk for guilt, depression, anxiety, confusion, self-blame, suicidal gestures, unprotected anal intercourse with untested partners, and heavy substance abuse. Beyond harms caused to individual people, there is a broad concern in the mental health community that the advancement of conversion therapy itself causes social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about sexual orientation and the ability of gay and bisexual people to lead happy, healthy lives. The American Psychological Association has stated: "Although there is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological interventions to change sexual orientation, some individuals modified their sexual orientation identity (i.e., group membership and affiliation), behavior, and values. They did so in a variety of ways and with varied and unpredictable outcomes, some of which were temporary. Based on the available data, additional claims about the meaning of those outcomes are scientifically unsupported."

Mainstream health organizations critical of conversion therapy include the American Medical Association, American Psychiatric Association, the American Psychological Association, the American Counseling Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Association of School Administrators, the American Federation of Teachers, the National Association of School Psychologists, the American Academy of Physician Assistants, and the National Education Association.

Mainstream medical organizations do not accept the anecdotal evidence offered by conversion therapists for several reasons. These include the fact that the results are not published in peer-reviewed journals, but tend to be released to the mass media and the Internet, that random samples of subjects are not used and results are reliant upon the subjects' own self-reported outcomes or on evaluations by therapists which may be subject to social desirability bias, that the evidence is gathered over short periods of time and there is little follow-up data to determine whether the therapy was effective over the long-term, that the evidence does not demonstrate a change in sexual orientation but merely a reduction in same-sex behavior, that the interpreters of the evidence do not take into consideration that subjects may be bisexual and have simply been convinced to restrict their sexual activity to the opposite sex, that conversion therapists falsely assume that homosexuality is a mental disorder, and that their research focuses almost exclusively on gay men and rarely includes lesbians.

Ethics guidelines

In 1998, the American Psychiatric Association issued a statement opposing any treatment which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality is a mental disorder or that a person should change their orientation, but did not have a formal position on other treatments that attempt to change a person's sexual orientation. In 2000, they augmented that statement by saying that as a general principle, a therapist should not determine the goal of treatment, but recommends that ethical practitioners refrain from attempts to change clients' sexual orientation until more research is available.

The American Counseling Association has stated that they do not offer or condone any training to educate and prepare a counselor to practice conversion therapy. They strongly suggest counselors do not refer clients to a conversion therapist or to proceed cautiously once they know the counselor fully informs clients of the unproven nature of the treatment and the potential risks and takes steps to minimize harm to clients. However, "it is of primary importance to respect a client's autonomy to request a referral for a service not offered by a counselor." A counselor performing conversion therapy "must define the techniques/procedures as 'unproven' or 'developing' and explain the potential risks and ethical considerations of using such techniques/procedures and take steps to protect clients from possible harm." The counselor must also provide complete information about the treatment, offer referrals to gay-affirmative counselors, discuss the right of clients, understand the client's request within a cultural context, and only practice within their level of expertise.

The American Psychological Association "is concerned about therapies and their potential harm to patients ... Any person who enters into therapy to deal with issues of sexual orientation has a right to expect that such therapy would take place in a professionally neutral environment absent of any social bias." The APA stated, with regard to conversion therapy,

{{quote|... that psychologists do not knowingly participate in or condone unfair discriminatory practices ... do not engage in unfair discrimination based on sexual orientation ... respect the rights of individuals to privacy, confidentiality, self-determination and autonomy ... , try to eliminate the effect on their work of biases based on the American Psychological Association urges all mental health professionals to take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated with homosexual orientation." (internal quotes, brackets, and ellipses omitted).

International medical views

The development of theoretical models of sexual orientation in countries outside the United States that have established mental health professions often follows the history within the U.S. (although often at a slower pace), shifting from pathological to non-pathological conceptions of homosexuality. The World Health Organization's ICD-10, which along with the DSM-IV is widely used internationally, states that "sexual orientation by itself is not to be regarded as a disorder". It lists ego-dystonic sexual orientation as a disorder instead, which it defines as occurring where "the gender identity or sexual preference (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, or prepubertal) is not in doubt, but the individual wishes it were different because of associated psychological and behavioural disorders, and may seek treatment in order to change it."

Legal issues

In 2005, Love in Action, an ex-gay ministry based in Memphis, was investigated by the Tennessee Department of Health and the Tennesee Department of Mental Health and Developmental Disabilities for providing counselling and mental health care without a licence, and for treating adolescents without their consent. There have been reports that teenagers have been forcibly treated with conversion therapy on other occasions. In 2006, a report by the National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce outlined evidence that conversion therapy groups are increasingly focusing on children. Several legal researchers have responded to these events by arguing that parents who force their children into aggressive conversion therapy programs are committing child abuse under various state statutes.

There have been few, if any, medical malpractice lawsuits filed on the basis of conversion therapy. Laura A. Gans suggested in an article published in The Boston University Public Interest Law Journal that this is because there is an "historic reluctance of consumers of mental health services to sue their care givers" and because of "the difficulty associated with establishing the elements of... causation and harm... given the intangible nature of psychological matters." Gans also suggested that a tort cause of action for intentional infliction of emotional distress might be sustainable against therapists who use conversion therapy on patients who specifically say that his or her anxiety does not arise from his or her sexuality.

In one of the few published U.S. cases dealing with conversion therapy, the Ninth Circuit addressed the topic in the context of an asylum application. A Russian citizen "had been apprehended by the Russian militia, registered at a clinic as a 'suspected lesbian,' and forced to undergo treatment for lesbianism, such as 'sedative drugs' and hypnosis.... The Ninth Circuit held that the conversion treatments to which Pitcherskaia had been subjected constituted mental and physical torture. The court rejected the argument that the treatments to which Pitcherskaia had been subjected did not constitute persecution because they had been intended to help her, not harm her.... The court stated that 'human rights laws cannot be sidestepped by simply couching actions that torture mentally or physically in benevolent terms such as "curing" or "treating" the victims.'" "

Notes

- ^ Drescher 2006, pp. 126, 175 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFDrescher2006 (help)

- ^ Position Statement on Therapies Focused on Attempts to Change Sexual Orientation (Reparative or Conversion Therapies) (PDF), American Psychiatric Association, 2000, retrieved 2007-08-28

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Challenging the ex-gay movement (PDF), Political Research Associates, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, Equal Partners in Faith, 1998, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ GLAAD, GLAAD Media Reference Guide (PDF), retrieved September 2006

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Yoshino 2002

- ^ Cianciotto, Jason; Cahill, Sean (2006), Youth in the crosshairs: the third wave of ex-gay activism (PDF), National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, retrieved 2007-08-29

- ^ Answers to Your Questions: For a Better Understanding of Sexual Orientation and Homosexuality (PDF), American Psychological Association, 2008, retrieved 2008-02-14

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Gonsiorek 1991 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFGonsiorek1991 (help)

- ^ Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel, Just the Facts Coalition, 1999, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Whitman, Joy S.; Glosoff, Harriet L.; Kocet, Michael M.; Tarvydas, Vilia (2006-05-22), Ethical issues related to conversion or reparative therapy, American Counseling Association, retrieved 2007-08-28

- ^ Drescher 1998, p. 152 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDrescher1998 (help)

- Lewes 1988, pp. 48–68 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- ^ O’Connor & Ryan 1993, p. 30-47

- ^ LeVay 1996 Cite error: The named reference "LeVay1996" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Gay 1995, p. xxxvi

- Lewes 1988, p. 28 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- Ruse 1988, p. 22

- ^ Lewes 1988 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- ^ Freud 1991, p. 58-59 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- Lewes 1988, p. 58 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- ^ Freud 1991, p. 375 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help) Cite error: The named reference "SigmundFreudCaseHistoriesII" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- Freud 1991, p. 376 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFFreud1991 (help)

- Freud 1992, p. 423-424

- ^ Lewes 1988, p. 51 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- Lewes 1998, p. 68 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1998 (help)

- Lewes 1988, p. 62 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFLewes1988 (help)

- ^ Jones 1955

- Stanton 1991

- ^ Bayer 1987

- ^ Katz 1976

- Rosario 1997

- Dorner 1976

- Stakelbeck & Udo 2003, pp. 23–46

- German Bundestag: Antihomosexuelle Seminare und pseudowissenschaftliche Therapieangebote religiöser Fundamentalisten (German) (PDF)

- ^ Young-Bruehl 1988, p. 327

- Leavitt 2006, p. 268

- Vallely, Paul (28 Jan 2006), Independent

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help); Text "Peter Tatchell: Out and about" ignored (help) - Tatchell, Peter (1972), Gay News http://www.petertatchell.net/psychiatry/dentist.htm

{{citation}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Tatchell, Peter (13 Sept 1997), Guardian

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Text "OBITUARY - Professor Hans Eysenck" ignored (help) - Peel 2007, pp. 18–19 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFPeel2007 (help)

- Thinking Anglicans, 13 September 2008

- Statement from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Gay and Lesbian Mental Health Special Interest Group, 13 September 2008

- Bartlett, Smith & King 2009

- Ballantyne 2009

- ^ Gay 2006

- Katz 1976, p. 149

- ^ Terry 1999, pp. 308–314

- Drescher 1998, pp. 19–42 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFDrescher1998 (help)

- Marmor 1965, pp. 175–189

- Bergler 1956

- Bergler 1962

- Hooker 1957, pp. 18–31

- Kirby 1957, pp. 674–677 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFKirby1957 (help)

- Bieber 1962

- Ellis 1962, p. 242

- Ellis 1965

- Seligman 1994, pp. 156–157

- Socarides 1968

- Janov 1977, p. 308

- Loughery 1998, p. 325

- Kovel 1991, pp. 188–198

- Rosen 1977, pp. 154–217

- Pendergrast 1995, pp. 442–443

- Exodus International Who We Are, Exodus International, 2005, retrieved 2009-05-25

- Exodus International Policy Statements, Exodus International, 2005, retrieved 2009-05-25

- Kronemeyer 1980, p. 87

- Moberly 1983 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMoberly1983 (help)

- Moberly 1983 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFMoberly1983 (help)