| Revision as of 23:15, 21 August 2010 editBomazi (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users3,446 edits removed ] which is already at Delta-v_budget← Previous edit | Revision as of 17:51, 22 August 2010 edit undoWolfkeeper (talk | contribs)31,832 edits rv: subarticleNext edit → | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

| Additionally raising thrust levels (when close to a gravitating body) can sometimes improve delta-v. | Additionally raising thrust levels (when close to a gravitating body) can sometimes improve delta-v. | ||

| ==Delta-vs around the Solar System==<!-- This section is linked from ] --> | |||

| {{main|delta-v budget}} | |||

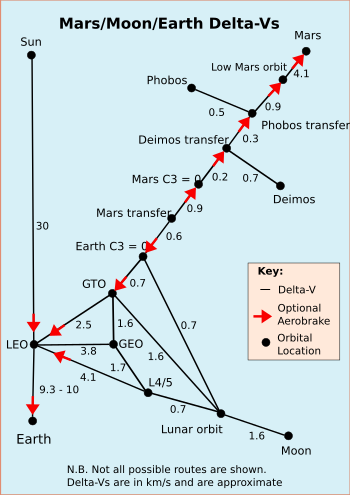

| ] ('''C3'''), ] ('''GEO'''), ] ('''GTO'''), Earth–Moon {{L5}} ] ('''L5'''), ] ('''LEO''')''<br> | |||

| Delta-vs in km/s for various orbital manoeuvers<ref name=marsdeltavs>{{dead link|date=February 2010}}. See: </ref><ref></ref> using conventional rockets. Red arrows show where optional aerobraking can be performed in that particular direction, black numbers give delta-v in km/s that apply in either direction. Lower delta-v transfers than shown can often be achieved, but involve rare transfer windows or take significantly longer, see: ]. Not all possible links are shown.]] | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

Revision as of 17:51, 22 August 2010

For other uses, see Delta-v (disambiguation).In astrodynamics, Δv or delta-v (literally "change in velocity"), is a scalar which takes units of speed that measures the amount of "effort" needed to carry out an orbital maneuver, i.e., to change from one trajectory to another.

where

If there are no other external forces than gravity, this is the integral of the magnitude of the g-force.

In the absence of external forces, and when thrust is applied in a constant direction this simplifies to:

which is simply the magnitude of the change in velocity. However, this relation does not hold in the general case: If, for instance, a constant, unidirectional acceleration is reversed after then the velocity difference is , but delta-v is the same as for the non-reversed thrust.

For rockets the 'absence of external forces' usually is taken to mean the absence of atmospheric drag as well as the absence of aerostatic back pressure on the nozzle and hence the vacuum Isp is used for calculating the vehicle's delta-v capacity via the rocket equation, and the costs for the atmospheric losses are rolled into the delta-v budget when dealing with launches from a planetary surface.

Delta-vs used for trajectories

When designing a trajectory, delta-v is used as an indicator of how much propellant will be required. Propellant usage is an exponential function of delta-v in accordance with the rocket equation.

It is not possible to determine delta-v requirements from conservation of energy by considering only the total energy of the vehicle in the initial and final orbits since the propellant carries energy away in the exhaust (see also below); as well as propellant being used up in a burn. For example, most spacecraft are launched in an orbit with inclination fairly near to the latitude at the launch site, to take advantage of the Earth's rotational surface speed. If it is necessary, for mission-based reasons, to put the spacecraft in an orbit of different inclination, a substantial delta-v is required, though the specific kinetic and potential energies in the final orbit and the initial orbit are equal.

When rocket thrust is applied in short bursts the other sources of acceleration may be negligible, and the magnitude of the velocity change of one burst may be simply approximated by the delta-v. The total delta-v to be applied can then simply be found by addition of each of the delta-vs needed at the discrete burns, even though between bursts the magnitude and direction of the velocity changes due to gravity, e.g. in an elliptic orbit.

For examples of calculating Delta-v, see Hohmann transfer orbit, gravitational slingshot, and Interplanetary Superhighway. It is also notable that large thrust can reduce gravity drag.

Delta-v is also required to keep satellites in orbit and is expended in propulsive orbital stationkeeping maneuvers. Since the propellant load on most satellites cannot be replenished, the amount of propellant initially loaded on a satellite may well determine its useful lifetime.

Oberth effect

Main article: Oberth effectFrom power considerations, it turns out that when applying delta-v in the direction of the velocity the specific orbital energy gained per unit delta-v is equal to the instantaneous speed. This is called the Oberth effect.

For example, a satellite in an elliptical orbit is boosted more efficiently at high speed (that is, small altitude) than at low speed (that is, high altitude).

Another example is that when a vehicle is making a pass of a planet, burning the propellant at closest approach rather than further out gives significantly higher final speed, and this is even more so when the planet is a large one with a deep gravity field, such as Jupiter.

See also {{#invoke:Gravitational_slingshot|Powered_slingshots|powered slingshots}}.

Porkchop plot

Due to the relative positions of planets changing over time, different delta-vs are required at different launch dates. A diagram that shows the required delta-v plotted against time is sometimes called a Porkchop plot. Such a diagram is useful since it enables calculation of a launch window, since launch should only occur when the mission is within the capabilities of the vehicle to be employed.

Producing Delta-v

Delta-v is typically provided by the thrust of a rocket engine, but can be created by other reaction engines. The time-rate of change of delta-v is the magnitude of the acceleration caused by the engines, i.e., the thrust per total vehicle mass. The actual acceleration vector would be found by adding thrust per mass on to the gravity vector and the vectors representing any other forces acting on the object.

The total delta-v needed is a good starting point for early design decisions since consideration of the added complexities are deferred to later times in the design process.

The rocket equation shows that the required amount of propellant dramatically increases, with increasing delta-v. Therefore in modern spacecraft propulsion systems considerable study is put into reducing the total delta-v needed for a given spaceflight, as well as designing spacecraft that are capable of producing a large delta-v.

Increasing the Delta-v provided by a propulsion system can be achieved by:

- staging

- increasing specific impulse

- improving propellant mass fraction

Additionally raising thrust levels (when close to a gravitating body) can sometimes improve delta-v.

Delta-vs around the Solar System

Main article: delta-v budget

Delta-vs in km/s for various orbital manoeuvers using conventional rockets. Red arrows show where optional aerobraking can be performed in that particular direction, black numbers give delta-v in km/s that apply in either direction. Lower delta-v transfers than shown can often be achieved, but involve rare transfer windows or take significantly longer, see: fuzzy orbital transfers. Not all possible links are shown.

See also

- Delta-v budget

- Gravity drag

- Orbital maneuver

- Orbital stationkeeping

- Spacecraft propulsion

- Specific impulse

- Tsiolkovsky rocket equation

References

| This article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. Please help improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (April 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

- Mars Exploration: Features

- Rockets and Space Transportation. See: Atomic Rocket: Missions

- cislunar delta-vs

is the instantaneous

is the instantaneous  is the instantaneous

is the instantaneous

then the velocity difference is

then the velocity difference is  , but delta-v is the same as for the non-reversed thrust.

, but delta-v is the same as for the non-reversed thrust.