| Revision as of 23:08, 23 July 2011 editVssun (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers2,578 edits →External links← Previous edit | Revision as of 20:01, 25 July 2011 edit undoBlackbow17 (talk | contribs)229 edits →As a metaphorNext edit → | ||

| Line 153: | Line 153: | ||

| == As a metaphor == | == As a metaphor == | ||

| In a philosophic/geometric sense: An apparent change in the direction of an object, caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The apparent displacement, or difference of position, of an object, as seen from two different stations, or points of view. In contemporary writing parallax can also be the same story, or a similar story from approximately the same time line, from one book told from a different perspective in another book. The word and concept feature prominently in ]'s 1922 novel, '']''. ] also used the term when referring to ] as compared to ]. | In a philosophic/geometric sense: An apparent change in the direction of an object, caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The apparent displacement, or difference of position, of an object, as seen from two different stations, or points of view. In contemporary writing parallax can also be the same story, or a similar story from approximately the same time line, from one book told from a different perspective in another book. The word and concept feature prominently in ]'s 1922 novel, '']''. ] also used the term when referring to ] as compared to ]. The artist ] named her studio ], in reference to her parallel production of paintings and films. | ||

| The metaphor is invoked by Slovenian philosopher ] in his work ''The Parallax View''. Žižek borrowed the concept of "parallax view" from the Japanese philosopher and literary critic Kojin Karatani. "The philosophical twist to be added (to parallax), of course, is that the observed distance is not simply subjective, since the same object that exists 'out there' is seen from two different stances, or points of view. It is rather that, as ] would have put it, subject and object are inherently mediated so that an ']' shift in the subject's point of view always reflects an ] shift in the object itself. Or—to put it in ]ese—the subject's gaze is always-already inscribed into the perceived object itself, in the guise of its 'blind spot,' that which is 'in the object more than object itself', the point from which the object itself returns the gaze. Sure the picture is in my eye, but I am also in the picture."<ref> | The metaphor is invoked by Slovenian philosopher ] in his work ''The Parallax View''. Žižek borrowed the concept of "parallax view" from the Japanese philosopher and literary critic Kojin Karatani. "The philosophical twist to be added (to parallax), of course, is that the observed distance is not simply subjective, since the same object that exists 'out there' is seen from two different stances, or points of view. It is rather that, as ] would have put it, subject and object are inherently mediated so that an ']' shift in the subject's point of view always reflects an ] shift in the object itself. Or—to put it in ]ese—the subject's gaze is always-already inscribed into the perceived object itself, in the guise of its 'blind spot,' that which is 'in the object more than object itself', the point from which the object itself returns the gaze. Sure the picture is in my eye, but I am also in the picture."<ref> | ||

Revision as of 20:01, 25 July 2011

For other uses, see Parallax (disambiguation).

Parallax is an apparent displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight, and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. The term is derived from the Greek παράλλαξις (parallaxis), meaning "alteration". Nearby objects have a larger parallax than more distant objects when observed from different positions, so parallax can be used to determine distances.

Astronomers use the principle of parallax to measure distances to celestial objects including to the Moon, the Sun, and to stars beyond the Solar System. For example, the Hipparcos satellite took measurements for over 100,000 nearby stars. This provides a basis for other distance measurements in astronomy, the cosmic distance ladder. Here, the term "parallax" is the angle or semi-angle of inclination between two sight-lines to the star.

Parallax also affects optical instruments such as binoculars, microscopes, and twin-lens reflex cameras that view objects from slightly different angles. Many animals, including humans, have two eyes with overlapping visual fields that use parallax to gain depth perception; this process is known as stereopsis. In computer vision the effect is used for computer stereo vision, and there is a device called a parallax rangefinder that uses it to find range, and in some variations also altitude to a target.

A simple everyday example of parallax can be seen in the dashboard of motor vehicles that use an older-style "needle" speedometer gauge. When viewed from directly in front, the speed may show exactly 60; but when viewed from the passenger seat the needle may appear to show a slightly different speed, due to the angle of viewing.

Visual perception

Main articles: stereopsis, depth perception, binocular vision, and Binocular disparity

As the eyes of humans and other animals are in different positions on the head, they present different views simultaneously. This is the basis of stereopsis, the process by which the brain exploits the parallax due to the different views from the eye to gain depth perception and estimate distances to objects. Animals also use motion parallax, in which the animals (or just the head) move to gain different viewpoints. For example, pigeons (whose eyes do not have overlapping fields of view and thus cannot use stereopsis) bob their heads up and down to see depth.

Distance measurement in astronomy

Stellar parallax

Main article: Stellar parallaxOn an interstellar scale, parallax created by the different orbital positions of the Earth causes nearby stars to appear to move relative to more distant stars. By observing parallax, measuring angles and using geometry, one can determine the distance to various objects. When the object in question is a star, the effect is known as stellar parallax.

Stellar parallax is most often measured using annual parallax, defined as the difference in position of a star as seen from the Earth and Sun, i. e. the angle subtended at a star by the mean radius of the Earth's orbit around the Sun. The parsec (3.26 light-years) is defined as the distance for which the annual parallax is 1 arcsecond. Annual parallax is normally measured by observing the position of a star at different times of the year as the Earth moves through its orbit. Measurement of annual parallax was the first reliable way to determine the distances to the closest stars. The first successful measurements of stellar parallax were made by Friedrich Bessel in 1838 for the star 61 Cygni using a heliometer. Stellar parallax remains the standard for calibrating other measurement methods. Accurate calculations of distance based on stellar parallax require a measurement of the distance from the Earth to the Sun, now based on radar reflection off the surfaces of planets.

The angles involved in these calculations are very small and thus difficult to measure. The nearest star to the Sun (and thus the star with the largest parallax), Proxima Centauri, has a parallax of 0.7687 ± 0.0003 arcsec. This angle is approximately that subtended by an object 2 centimeters in diameter located 5.3 kilometers away.

The fact that stellar parallax was so small that it was unobservable at the time was used as the main scientific argument against heliocentrism during the early modern age. It is clear from Euclid's geometry that the effect would be undetectable if the stars were far enough away, but for various reasons such gigantic distances involved seemed entirely implausible: it was one of Tycho's principal objections to Copernican heliocentrism that in order for it to be compatible with the lack of observable stellar parallax, there would have to be an enormous and unlikely void between the orbit of Saturn and the eighth sphere (the fixed stars).

In 1989, the satellite Hipparcos was launched primarily for obtaining parallaxes and proper motions of nearby stars, increasing the reach of the method tenfold. Even so, Hipparcos is only able to measure parallax angles for stars up to about 1,600 light-years away, a little more than one percent of the diameter of the Milky Way Galaxy. The European Space Agency's Gaia mission, due to launch in 2012 and come online in 2013, will be able to measure parallax angles to an accuracy of 10 microarcseconds, thus mapping nearby stars (and potentially planets) up to a distance of tens of thousands of light-years from earth.

Computation

Distance measurement by parallax is a special case of the principle of triangulation, which states that one can solve for all the sides and angles in a network of triangles if, in addition to all the angles in the network, the length of at least one side has been measured. Thus, the careful measurement of the length of one baseline can fix the scale of an entire triangulation network. In parallax, the triangle is extremely long and narrow, and by measuring both its shortest side (the motion of the observer) and the small top angle (always less than 1 arcsecond, leaving the other two close to 90 degrees), the length of the long sides (in practice considered to be equal) can be determined.

Assuming the angle is small (see derivation below), the distance to an object (measured in parsecs) is the reciprocal of the parallax (measured in arcseconds): For example, the distance to Proxima Centauri is 1/0.7687=1.3009 parsecs (4.243 ly).

Diurnal parallax

Diurnal parallax is a parallax that varies with rotation of the Earth or with difference of location on the Earth. The Moon and to a smaller extent the terrestrial planets or asteroids seen from different viewing positions on the Earth (at one given moment) can appear differently placed against the background of fixed stars.

Lunar parallax

Lunar parallax (often short for lunar horizontal parallax or lunar equatorial horizontal parallax), is a special case of (diurnal) parallax: the Moon, being the nearest celestial body, has by far the largest maximum parallax of any celestial body, it can exceed 1 degree.

The diagram (above) for stellar parallax can illustrate lunar parallax as well, if the diagram is taken to be scaled right down and slightly modified. Instead of 'near star', read 'Moon', and instead of taking the circle at the bottom of the diagram to represent the size of the Earth's orbit around the Sun, take it to be the size of the Earth's globe, and of a circle around the Earth's surface. Then, the lunar (horizontal) parallax amounts to the difference in angular position, relative to the background of distant stars, of the Moon as seen from two different viewing positions on the Earth:- one of the viewing positions is the place from which the Moon can be seen directly overhead at a given moment (that is, viewed along the vertical line in the diagram); and the other viewing position is a place from which the Moon can be seen on the horizon at the same moment (that is, viewed along one of the diagonal lines, from an Earth-surface position corresponding roughly to one of the blue dots on the modified diagram).

The lunar (horizontal) parallax can alternatively be defined as the angle subtended at the distance of the Moon by the radius of the Earth -- equal to angle p in the diagram when scaled-down and modified as mentioned above.

The lunar horizontal parallax at any time depends on the linear distance of the Moon from the Earth. The Earth-Moon linear distance varies continuously as the Moon follows its perturbed and approximately elliptical orbit around the Earth. The range of the variation in linear distance is from about 56 to 63.7 earth-radii, corresponding to horizontal parallax of about a degree of arc, but ranging from about 61.4' to about 54'. The Astronomical Almanac and similar publications tabulate the lunar horizontal parallax and/or the linear distance of the Moon from the Earth on a periodical e.g. daily basis for the convenience of astronomers (and formerly, of navigators), and the study of the way in which this coordinate varies with time forms part of lunar theory.

Parallax can also be used to determine the distance to the Moon.

One way to determine the lunar parallax from one location is by using a lunar eclipse. A full shadow of the Earth on the Moon has an apparent radius of curvature equal to the difference between the apparent radii of the Earth and the Sun as seen from the Moon. This radius can be seen to be equal to 0.75 degree, from which (with the solar apparent radius 0.25 degree) we get an Earth apparent radius of 1 degree. This yields for the Earth-Moon distance 60 Earth radii or 384,000 km. This procedure was first used by Aristarchus of Samos and Hipparchus, and later found its way into the work of Ptolemy. The diagram at right shows how daily lunar parallax arises on the geocentric and geostatic planetary model in which the Earth is at the centre of the planetary system and does not rotate. It also illustrates the important point that parallax need not be caused by any motion of the observer, contrary to some definitions of parallax that say it is, but may arise purely from motion of the observed.

Another method is to take two pictures of the Moon at exactly the same time from two locations on Earth and compare the positions of the Moon relative to the stars. Using the orientation of the Earth, those two position measurements, and the distance between the two locations on the Earth, the distance to the Moon can be triangulated:

This is the method referred to by Jules Verne in From the Earth to the Moon:

Until then, many people had no idea how one could calculate the distance separating the Moon from the Earth. The circumstance was exploited to teach them that this distance was obtained by measuring the parallax of the Moon. If the word parallax appeared to amaze them, they were told that it was the angle subtended by two straight lines running from both ends of the Earth's radius to the Moon. If they had doubts on the perfection of this method, they were immediately shown that not only did this mean distance amount to a whole two hundred thirty-four thousand three hundred and forty-seven miles (94,330 leagues), but also that the astronomers were not in error by more than seventy miles (≈ 30 leagues).

Solar parallax

After Copernicus proposed his heliocentric system, with the Earth in revolution around the Sun, it was possible to build a model of the whole solar system without scale. To ascertain the scale, it is necessary only to measure one distance within the solar system, e.g., the mean distance from the Earth to the Sun (now called an astronomical unit, or AU). When found by triangulation, this is referred to as the solar parallax, the difference in position of the Sun as seen from the Earth's centre and a point one Earth radius away, i. e., the angle subtended at the Sun by the Earth's mean radius. Knowing the solar parallax and the mean Earth radius allows one to calculate the AU, the first, small step on the long road of establishing the size and expansion age of the visible Universe.

A primitive way to determine the distance to the Sun in terms of the distance to the Moon was already proposed by Aristarchus of Samos in his book On the Sizes and Distances of the Sun and Moon. He noted that the Sun, Moon, and Earth form a right triangle (right angle at the Moon) at the moment of first or last quarter moon. He then estimated that the Moon, Earth, Sun angle was 87°. Using correct geometry but inaccurate observational data, Aristarchus concluded that the Sun was slightly less than 20 times farther away than the Moon. The true value of this angle is close to 89° 50', and the Sun is actually about 390 times farther away. He pointed out that the Moon and Sun have nearly equal apparent angular sizes and therefore their diameters must be in proportion to their distances from Earth. He thus concluded that the Sun was around 20 times larger than the Moon; this conclusion, although incorrect, follows logically from his incorrect data. It does suggest that the Sun is clearly larger than the Earth, which could be taken to support the heliocentric model.

Although Aristarchus' results were incorrect due to observational errors, they were based on correct geometric principles of parallax, and became the basis for estimates of the size of the solar system for almost 2000 years, until the transit of Venus was correctly observed in 1761 and 1769. This method was proposed by Edmond Halley in 1716, although he did not live to see the results. The use of Venus transits was less successful than had been hoped due to the black drop effect, but the resulting estimate, 153 million kilometers, is just 2% above the currently accepted value, 149.6 million kilometers.

Much later, the Solar System was 'scaled' using the parallax of asteroids, some of which, like Eros, pass much closer to Earth than Venus. In a favourable opposition, Eros can approach the Earth to within 22 million kilometres. Both the opposition of 1901 and that of 1930/1931 were used for this purpose, the calculations of the latter determination being completed by Astronomer Royal Sir Harold Spencer Jones.

Also radar reflections, both off Venus (1958) and off asteroids, like Icarus, have been used for solar parallax determination. Today, use of spacecraft telemetry links has solved this old problem. The currently accepted value of solar parallax is 8".794 143.

Dynamic or moving-cluster parallax

Main article: Moving cluster methodThe open stellar cluster Hyades in Taurus extends over such a large part of the sky, 20 degrees, that the proper motions as derived from astrometry appear to converge with some precision to a perspective point north of Orion. Combining the observed apparent (angular) proper motion in seconds of arc with the also observed true (absolute) receding motion as witnessed by the Doppler redshift of the stellar spectral lines, allows estimation of the distance to the cluster (151 light-years) and its member stars in much the same way as using annual parallax.

Dynamic parallax has sometimes also been used to determine the distance to a supernova, when the optical wave front of the outburst is seen to propagate through the surrounding dust clouds at an apparent angular velocity, while its true propagation velocity is known to be the speed of light.

Derivation

For a right triangle,

where is the parallax, 1 AU (149,600,000 km) is approximately the average distance from the Sun to Earth, and is the distance to the star. Using small-angle approximations (valid when the angle is small compared to 1 radian),

so the parallax, measured in arcseconds, is

If the parallax is 1", then the distance is

This defines the parsec, a convenient unit for measuring distance using parallax. Therefore, the distance, measured in parsecs, is simply , when the parallax is given in arcseconds.

Parallax error

Precise parallax measurements of distance have an associated error. However this error in the measured parallax angle does not translate directly into an error for the distance, except for relatively small errors. The reason for this is that an error toward a smaller angle results in a greater error in distance than an error toward a larger angle.

However, an approximation of the distance error can be computed by

where d is the distance and p is the parallax. The approximation is far more accurate for parallax errors that are small relative to the parallax than for relatively large errors.

Parallax and measurement instruments

If an optical instrument — e.g., a telescope, microscope, or theodolite — is imprecisely focused, its cross-hairs will appear to move with respect to the object focused on if one moves one's head horizontally in front of the eyepiece. This is why it is important, especially when performing measurements, to focus carefully in order to eliminate the parallax, and to check by moving one's head.

Also, in non-optical measurements the thickness of a ruler can create parallax in fine measurements. To avoid parallax error, one should take measurements with one's eye on a line directly perpendicular to the ruler so that the thickness of the ruler does not create error in positioning for fine measurements. A similar error can occur when reading the position of a pointer against a scale in an instrument such as a galvanometer (for example, in an analog-display multimeter.) To help the user avoid this problem, the scale is sometimes printed above a narrow strip of mirror, and the user positions his eye so that the pointer obscures its own reflection. This guarantees that the user's line of sight is perpendicular to the mirror and therefore to the scale.

Parallax can cause a speedometer reading to appear different to car's passenger from what it does to the driver. This is called a parallax error – the apparent shifting of the reading on a measuring instrument due to a change of the observer's viewing angle.

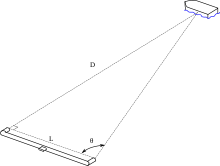

Photogrammetric parallax

Aerial picture pairs, when viewed through a stereo viewer, offer a pronounced stereo effect of landscape and buildings. High buildings appear to 'keel over' in the direction away from the centre of the photograph. Measurements of this parallax are used to deduce the height of the buildings, provided that flying height and baseline distances are known. This is a key component to the process of photogrammetry.

Parallax error in photography

Parallax error can be seen when taking photos with many types of cameras, such as twin-lens reflex cameras and those including viewfinders (such as rangefinder cameras). In such cameras, the eye sees the subject through different optics (the viewfinder, or a second lens) than the one through which the photo is taken. As the viewfinder is often found above the lens of the camera, photos with parallax error are often slightly lower than intended, the classic example being the image of person with his or her head cropped off. This problem is addressed in single-lens reflex cameras, in which the viewfinder sees through the same lens through which the photo is taken (with the aid of a movable mirror), thus avoiding parallax error.

Parallax is also an issue in image stitching, such as for panoramas.

In computer graphics

Main articles: Parallax scrolling and Parallax mappingIn many early graphical applications, such as video games, the scene was constructed of independent layers that were scrolled at different speeds when the player/cursor moved. Some hardware had explicit support for such layers, such as the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. This gave some layers the appearance of being farther away than others and was useful for creating an illusion of depth, but only worked when the player was moving. Now, most games are based on much more comprehensive three-dimensional graphic models, although portable game systems (such as Nintendo DS) still often use parallax. Parallax-based graphics continue to be used for many online applications where the bandwidth required by three-dimensional graphics is excessive.

Parallax compensation for firearm and archery sights

Main article: Telescopic sight § Parallax compensationWhen a telescope sight is fitted to small arms, the distance between the sighting mechanism and the weapon's bore can introduce significant errors when firing at close range, particularly when firing at small targets. This also applies to archery where the shooter frequently relies on a single pin at close range.

Most telescopic sights lack parallax compensation because they can perform very acceptably without refinement for parallax. Telescopic sights manufacturers adjust these scopes at a distance that best suits their intended usage. Typical standard factory parallax adjustment distances for hunting telescopic sights are 100 yd or 100 m to make them suited for hunting shots that rarely exceed 300 yd/m. Some target and military style telescopic sights without parallax compensation may be adjusted to be parallax free at ranges up to 300 yd/m to make them better suited for aiming at longer ranges. Scopes for rimfires, shotguns, and muzzleloaders will have shorter parallax settings, commonly 50 yd/m for rimfire scopes and 100 yd/m for shotguns and muzzleloaders. Scopes for airguns are very often found with adjustable parallax, usually in the form of an adjustable objective, or AO. These may adjust down as far as 3 yards (2.74 m).

In Naval Gunfire

Owing to the positioning of gun turrets on a warship or in the field, each one has a slightly different perspective of the target relative to the location of the fire control system itself. Therefore, when aiming its guns at the target, the fire control system must compensate for parallax in order to assure that fire from each turret converges on the target.

Parallax rangefinders

A Coincidence rangefinder or Parallax rangefinder can be used to find distance to a target.

As a metaphor

In a philosophic/geometric sense: An apparent change in the direction of an object, caused by a change in observational position that provides a new line of sight. The apparent displacement, or difference of position, of an object, as seen from two different stations, or points of view. In contemporary writing parallax can also be the same story, or a similar story from approximately the same time line, from one book told from a different perspective in another book. The word and concept feature prominently in James Joyce's 1922 novel, Ulysses. Orson Scott Card also used the term when referring to Ender's Shadow as compared to Ender's Game. The artist Sarah Morris named her studio Parallax, in reference to her parallel production of paintings and films.

The metaphor is invoked by Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek in his work The Parallax View. Žižek borrowed the concept of "parallax view" from the Japanese philosopher and literary critic Kojin Karatani. "The philosophical twist to be added (to parallax), of course, is that the observed distance is not simply subjective, since the same object that exists 'out there' is seen from two different stances, or points of view. It is rather that, as Hegel would have put it, subject and object are inherently mediated so that an 'epistemological' shift in the subject's point of view always reflects an ontological shift in the object itself. Or—to put it in Lacanese—the subject's gaze is always-already inscribed into the perceived object itself, in the guise of its 'blind spot,' that which is 'in the object more than object itself', the point from which the object itself returns the gaze. Sure the picture is in my eye, but I am also in the picture."

Notes

- Shorter Oxford English Dictionary. 1968.

Mutual inclination of two lines meeting in an angle

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - "Parallax". Oxford English Dictionary (Second Edition ed.). 1989.

Astron. Apparent displacement, or difference in the apparent position, of an object, caused by actual change (or difference) of position of the point of observation; spec. the angular amount of such displacement or difference of position, being the angle contained between the two straight lines drawn to the object from the two different points of view, and constituting a measure of the distance of the object.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - Steinman, Scott B.; Garzia, Ralph Philip (2000). Foundations of Binocular Vision: A Clinical perspective. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 2–5. ISBN 0-8385-2670-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Steinman & Garzia 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Zeilik & Gregory 1998, p. 44.

- Zeilik & Gregory 1998, § 22-3.

- ^ Benedict, G. Fritz; et al. (1999). "Interferometric Astrometry of Proxima Centauri and Barnard's Star Using HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE Fine Guidance Sensor 3: Detection Limits for Substellar Companions". The Astronomical Journal. 118 (2): 1086–1100. arXiv:astro-ph/9905318. Bibcode:1999astro.ph..5318B. doi:10.1086/300975.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - See p.51 in The reception of Copernicus' heliocentric theory: proceedings of a symposium organized by the Nicolas Copernicus Committee of the International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science, Torun, Poland, 1973, ed. Jerzy Dobrzycki, International Union of the History and Philosophy of Science. Nicolas Copernicus Committee; ISBN 90-277-0311-6, ISBN 978-90-277-0311-8

- Henney, Paul J. "ESA's Gaia Mission to study stars". Astronomy Today. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- Seidelmann, P. Kenneth (2005). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books. pp. 123–125. ISBN 1891389459.

- Barbieri, Cesare (2007). Fundamentals of astronomy. CRC Press. pp. 132–135. ISBN 0750308869.

- ^ Astronomical Almanac e.g. for 1981, section D

- Astronomical Almanac, e.g. for 1981: see Glossary; for formulae see Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac, 1992, p.400

- ^ Gutzwiller, Martin C. (1998). "Moon-Earth-Sun: The oldest three-body problem". Reviews of Modern Physics. 70 (2): 589. Bibcode:1998RvMP...70..589G. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.70.589.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Freedman, W.L. (2000). "The Hubble constant and the expansion age of the Universe". Physics Reports. 333 (1): 13. arXiv:astro-ph/9909076. Bibcode:2000PhR...333...13F. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(00)00013-2.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whipple 2007, p. 47.

- Whipple 2007, p. 117.

- US Naval Observatory, Astronomical Constants

- Vijay K. Narayanan; Andrew Gould (1999). "A Precision Test of Hipparcos Systematics toward the Hyades". The Astrophysical Journal. 515 (1): 256. arXiv:astro-ph/9808284. Bibcode:1999ApJ...515..256N. doi:10.1086/307021.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Panagia, N.; Gilmozzi, R.; MacChetto, F.; Adorf, H.-M.; Kirshner, R. P. (1991). "Properties of the SN 1987A circumstellar ring and the distance to the Large Magellanic Cloud". The Astrophysical Journal. 380: L23. Bibcode:1991ApJ...380L..23P. doi:10.1086/186164.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Similar derivations are in most astronomy textbooks. See, e. g., Zeilik & Gregory 1998, § 11-1.

- Schmidt & Bender PM II specs

- BSA rimfire scopes

- BSA shotgun/muzzleloader scope

- Leapers 3-9x32 Mini Mil-Dot Illuminated AO Scope (SCP-M392AOMDL), parallax adjustable from 3 yards to ∞

- Žižek, Slavoj (2006). The Parallax View. The MIT Press. p. 17. ISBN 0262240513.

See also

- Triangulation, wherein a point is calculated given its angles from other known points

- Trilateration, wherein a point is calculated given its distances from other known points

- Disparity

- Spectroscopic parallax

- Trigonometry

- Xallarap

References

- Hirshfeld, Alan w. (2001). Parallax: The Race to Measure the Cosmos. New York: W. H. Freeman. ISBN 0716737116.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Whipple, Fred L. (2007). Earth Moon and Planets. Read Books. ISBN 1406764132.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help). - Zeilik, Michael A.; Gregory, Stephan A. (1998). Introductory Astronomy & Astrophysics (4th ed.). Saunders College Publishing. ISBN 0030062284.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help).

External links

- Instructions for having background images on a web page use parallax effects

- Actual parallax project measuring the distance to the moon within 2.3%

- BBC's Sky at Night programme: Patrick Moore demonstrates Parallax using Cricket. (Requires RealPlayer)

- Berkely Center for Cosmological Physics Parallax

- Parallax on an educational website, including a quick estimate of distance based on parallax using eyes and a thumb only

For example, the distance to

For example, the distance to

is the parallax, 1 AU (149,600,000 km) is approximately the average distance from the Sun to Earth, and

is the parallax, 1 AU (149,600,000 km) is approximately the average distance from the Sun to Earth, and  is the distance to the star.

Using

is the distance to the star.

Using

, when the parallax is given in arcseconds.

, when the parallax is given in arcseconds.