This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 2a00:20:2021:aa18:0:5f:aa3b:a201 (talk) at 15:47, 25 May 2021 (Undid revision 1025050288 by Mugsalot (talk)). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:47, 25 May 2021 by 2a00:20:2021:aa18:0:5f:aa3b:a201 (talk) (Undid revision 1025050288 by Mugsalot (talk))(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For other uses, see Aramean (disambiguation). Ethnic group Ethnic flag used by the Arameans Ethnic flag used by the Arameans | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,000,000 - 5,000,000 | |

| 250,000–877,000 | |

| 150,000-250,000 | |

| 20,000–50,000 | |

| Diaspora: | Numbers can vary |

| 250,000–500,000 | |

| 150,000+ | |

| 100,000–120,000 | |

| 85,000 | |

| 50,000 | |

| 30,000 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 12,000 | |

| 10,000 | |

| 9,000 | |

| 5,000 | |

| 3,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Neo-Aramaic (Turoyo, Western) | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Syriac Christianity Also Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Arameans (Syriac: ܣܘܪ̈ܝܝܐ or ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ) also known as Syriacs or Native Syrians, are an ethnic group indigenous to the Levant and Mesopotamia, a region in the Middle East previously known as Aram. Arameans claim descent from the ancient Arameans, one of the oldest civilizations in the world, dating back to 2500 BC in ancient Mesopotamia.

Arameans speak various dialects of Neo-Aramaic, a modern variant of the ancient Aramaic language, with Turoyo and Western Neo-Aramaic being the two main spoken subdialects. The Arameans are a predominantly Christian nation who belong to various denominations of Syriac Christianity and to a lesser degree a group of Mandaeans who are non-Christian remnants of the ancient Arameans. Arameans have maintained a continuous and separate identity that predates the Arabization of the Middle East.

The majority of Arameans live in a diaspora and fled to other regions of the world, such as Europe, North America, and Australia. They fled due to Islamic oppression in their ancestral homeland. Events such as the Hamidian Massacres, the Seyfo and the present-day takeover of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) caused the reduction of Arameans in these regions.

History

Origins

The toponym A-ra-mu appears in an inscription at the East Semitic speaking kingdom of Ebla listing geographical names, and the term Armi, which is the Eblaite term for nearby Idlib, occurs frequently in the Ebla tablets (c. 2300 BCE). One of the annals of Naram-Sin of Akkad (c. 2250 BCE) mentions that he captured "Dubul, the ensí of A-ra-me" (Arame is seemingly a genitive form), in the course of a campaign against Simurrum in the northern mountains. Other early references to a place or people of "Aram" have appeared at the archives of Mari (c. 1900 BCE) and at Ugarit (c. 1300 BCE). However, there are no historical, archaeological or linguistic evidences that those early uses of the terms Aramu, Armi or Arame were actually referring to the Arameans. The earliest undisputed historical attestation of Arameans as a people appears much later, in the inscriptions of Tiglath Pileser I (c. 1100 BCE).

Nomadic pastoralists have long played a prominent role in the history and economy of the Middle East, but their numbers seem to vary according to climatic conditions and the force of neighbouring states inducing permanent settlement. The period of the Late Bronze Age seems to have coincided with increasing aridity, which weakened neighbouring states and induced transhumance pastoralists to spend longer and longer periods with their flocks. Urban settlements (hitherto largely Amorite, Canaanite, Hittite, Ugarite inhabited) in The Levant diminished in size, until eventually fully nomadic pastoralist lifestyles came to dominate much of the region. These highly mobile, competitive tribesmen with their sudden raids continually threatened long-distance trade and interfered with the collection of taxes and tribute.

The people who had long been the prominent population within what is today Syria (called the Land of the Amurru during their tenure) were the Amorites, a Northwest Semitic-speaking speaking people who had appeared during the 25th century BCE, destroying the hitherto dominant East Semitic speaking state of Ebla, founding the powerful state of Mari in the Levant, and during the 19th century BCE founding Babylonia in southern Mesopotamia. However, they seem to have been displaced or wholly absorbed by the appearance of a people called the Ahlamu by the 13th century BCE, disappearing from history.

Ahlamû appears to be a generic term for a new wave of Semitic wanderers and nomads of varying origins who appeared during the 13th century BCE across the Near East, Arabian Peninsula, Asia Minor, and Egypt. The presence of the Ahlamû is attested during the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1020 BCE), which already ruled many of the lands in which the Ahlamû arose, in the Babylonian city of Nippur and even at Dilmun (modern Bahrain). Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BCE) is recorded as having defeated Shattuara, King of the Mitanni and his Hittite and Ahlamû mercenaries. In the following century, the Ahlamû cut the road from Babylon to Hattusas, and Tukulti-Ninurta I (1244–1208 BCE) conquered Mari, Hanigalbat and Rapiqum on the Euphrates and "the mountain of the Ahlamû", apparently the region of Jebel Bishri in northern Syria.

The Arameans would appear to be one part of the larger generic Ahlamû group rather than synonymous with the Ahlamu.

Aramean states

The emergence of the Arameans occurred during the Bronze Age collapse (1200–900 BCE), which saw great upheavals and mass movements of peoples across the Middle East, Asia Minor, The Caucasus, East Mediterranean, North Africa, Ancient Iran, Ancient Greece and Balkans, leading to the genesis of new peoples and polities across these regions.

The first certain reference to the Arameans appears in an inscription of Tiglath-Pileser I (1115–1077 BCE), which refers to subjugating the "Ahlamû-Arameans" (Ahlame Armaia). Shortly after, the Ahlamû disappear from Assyrian annals, to be replaced by the Arameans (Aramu, Arimi). This indicates that the Arameans had risen to dominance amongst the nomads. Among scholars, the relationship between the Akhlame and the Arameans is a matter of conjecture. By the late 12th century BCE, the Arameans were firmly established in Syria; however, they were conquered by the Middle Assyrian Empire, as had been the Amorites and Ahlamu before them.

The Middle Assyrian Empire (1365–1050 BCE), which had dominated the Near East and Asia Minor since the first half of the 14th century BCE, began to shrink rapidly after the death of Ashur-bel-kala, its last great ruler in 1056 BCE, and the Assyrian withdrawal allowed the Arameans and others to gain independence and take firm control of what was then Eber-Nari (and is today Syria) during the late 11th century BCE. It is from this point that the region was called Aramea.

Some of the major Aramaic speaking kingdoms included: Aram-Damascus, Hamath, Bet-Adini, Bet-Bagyan, Bit-Hadipe, Aram-Bet Rehob, Aram-Zobah, Bet-Zamani, Bet-Halupe, and Aram-Ma'akah, as well as the Aramean tribal polities of the Gambulu, Litau and Puqudu.

Later Biblical sources tell us that Saul, David and Solomon (late 11th to 10th centuries) fought against the small Aramean kingdoms ranged across the northern frontier of Israel: Aram-Sôvah in the Beqaa, Aram-Bêt-Rehob (Rehov) and Aram-Ma'akah around Mount Hermon, Geshur in the Hauran, and Aram-Damascus. An Aramean king's account dating at least two centuries later, the Tel Dan Stele, was discovered in northern Israel, and is famous for being perhaps the earliest non-Israelite extra-biblical historical reference to the Israelite royal dynasty, the House of David. In the early 11th century BCE, much of Israel came under foreign rule for eight years according to the Biblical Book of Judges, until Othniel defeated the forces led by Cushan-Rishathaim, who was titled in the Bible as ruler of Aram-Naharaim.

Further north, the Arameans gained possession of Post-Hittite Hamath on the Orontes and were soon to become strong enough to dissociate with the Indo-European speaking Post-Hittite states.

During the 11th and the 10th centuries BCE, the Arameans conquered Sam'al (modern Zenjirli), also known as Yaudi, the region from Arpad to Aleppo, which they renamed Bît-Agushi, and Til Barsip, which became the chief town of Bît-Adini, also known as Beth Eden. North of Sam'al was the Aramean state of Bit-Gabbari, which was sandwiched between the Post-Hittite states of Carchemish, Gurgum, Khattina, Unqi and the Georgian state of Tabal.

At the same time, Arameans moved to the east of the Euphrates, where they settled in such numbers that, for a time, the whole region became known as Aram-Naharaim or "Aram of the two rivers". Eastern Aramean tribes spread into Babylonia and an Aramean usurper was crowned king of Babylon under the name of Adad-apal-iddin. One of their earliest semi-independent kingdoms in southern Mesopotamia was Bît-Bahiâni (Tell Halaf).

Under Neo-Assyrian rule

Assyrian annals from the end of the Middle Assyrian Empire c. 1050 BCE and the rise of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 911 BCE contain numerous descriptions of battles between Arameans and the Assyrian army. The Assyrians would launch repeated raids into Aramea, Babylonia, Ancient Iran, Elam, Asia Minor, and even as far as the Mediterranean, in order to keep its trade routes open. The Aramean kingdoms, like much of the Near East and Asia Minor, were subjugated by the Neo Assyrian Empire (911–605 BCE), beginning with the reign of Adad-nirari II in 911 BCE, who cleared Arameans and other tribal peoples from the borders of Assyria, and began to expand in all directions (See Assyrian conquest of Aram). This process was continued by Ashurnasirpal II, and his son Shalmaneser III, who between them destroyed many of the small Aramean tribes, and conquered the whole of Aramea (modern Syria) for the Assyrians. In 732 BCE Aram-Damascus fell and was conquered by the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III. The Assyrians named their Aramean colonies Eber Nari, whilst still using the term Aramean to describe many of its peoples. The Assyrians conducted forced deportations of hundreds of thousands Arameans into both Assyria and Babylonia (where a migrant population already existed). Conversely, the Aramaic language was adopted as the lingua franca of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BCE, and the native Assyrians and Babylonians began to make a gradual language shift towards Aramaic as the most common language of public life and administration.

The Neo Assyrian Empire descended into a bitter series of brutal internal wars from 626 BCE, weakening it greatly. This allowed a coalition of many its former subject peoples; the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Parthians, Scythians, Sargatians and Cimmerians to attack Assyria in 616 BCE, sacking Nineveh in 612 BCE, and finally defeating it between 605 and 599 BCE. During the war against Assyria, hordes of horse borne Scythian and Cimmerian marauders ravaged through Aramea and all the way into Egypt.

As a result of migratory processes, various Aramean groups were settled throughout the Ancient Near East, and their presence is recorded in the regions of Assyria, Babylonia, Anatolia, Phoenicia, Palestine, Egypt, and Northern Arabia.

Population transfers, conducted during the Neo-Assyrian Empire and followed by gradual linguistic aramization of non-Aramean populations, created a specific situation in the regions of Assyria proper, among ancient Assyrians, who originally spoke ancient Assyrian language (a dialect of Akkadian), but later accepted Aramaic language.

Under Neo-Babylonian rule

Aramea/Eber-Nari was then ruled by the succeeding Neo-Babylonian Empire (612–539 BCE), initially headed by a short lived Chaldean dynasty. The Aramean regions became a battleground between the Babylonians and the Egyptian 26th Dynasty, which had been installed by the Assyrians as vassals after they had conquered Egypt, ejected the previous Nubian dynasty and destroyed the Kushite Empire. The Egyptians, having entered the region in a belated attempt to aid their former Assyrian masters, fought the Babylonians (initially with the help of remnants of the Assyrian army) in the region for decades before being finally vanquished.

The Babylonians remained masters of the Aramean lands only until 539 BCE, when the Persian Achaemenid Empire overthrew Nabonidus, the Assyrian born last king of Babylon, who had himself previously overthrown the Chaldean dynasty in 556 BCE.

Under Achaemenid rule

Further information: Imperial Aramaic and Eber NariThe Arameans were later conquered by the Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BCE). However, little changed from the Neo-Assyrian and Neo-Babylonian times, as the Persians, seeing themselves as successors of previous empires, maintained Imperial Aramaic language as the main language of public life and administration. Provincial administrative structures also remained the same, and the name Eber Nari still applied to the region.

Under Seleucid and Ptolemaic rule

Further information: Coele Syria and Syrian WarsConquests of Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE) marked the beginning of a new era in the history of the entire Near East, including regions inhabited by Arameans. By the end of the 4th century BCE, two newly created Hellenistic states emerged as main pretenders for regional supremacy: the Seleucid Empire (305–64 BCE), and the Ptolemaic Empire (305–30 BCE). Several conflicts, known in historiography as the Syrian Wars, were fought during the 3rd and the 2nd century BCE between those two powers, over the control of regions that came to be known as "Coele Syria" (meaning: the whole Syria), a term derived from an older Aramean designation (the whole Aram). Since earlier times, ancient Greeks were commonly using "Syrian" labels as designations for Arameans and heir lands, but is during the Hellenistic (Seleucid-Ptolemaic) period that the term Syria was finally defined, as designation for regions western of Euphrates, as opposed to the term Assyria, that designated regions further to the east.

During the 3rd century BCE, various narratives related to the history of earlier Aramean kingdoms became accessible to wider audiences after the translation of Hebrew Bible into Greek language. Known as Septuagint, the translation was created in Alexandria, capital city of Ptolemaic Egypt, that was the most important city of the Hellenistic world, and also one of the main centers of Hellenization. Influenced by Greek terminology, translators decided to adopt ancient Greek custom of using "Syrian" labels as designations for Arameans and their lands, thus abandoning endonymic (native) terms, that were used in the Hebrew Bible. In the Greek translation (Septuagint), the region of Aram was commonly labeled as "Syria", while Arameans were labeled as "Syrians". Such promotion of exonymic (foreign) terms had far-reaching influence on later terminology.

Reflecting on traditional influences of Greek terminology on English translations of the Septuagint, American orientalist Robert W. Rogers (d. 1930) noted in 1921: "it is most unfortunate that Syria and Syrians ever came into the English versions. It should always be Aram and the Arameans".

Under Roman and Parthian rule

After the establishment of Roman rule in the region of Syria proper (western of Euphrates) during the 1st century BCE, Aramean lands became the frontier region between two empires, Roman and Parthian, and later between their successor states, Byzantine and Sasanid empires. Several minor states also existed in frontier regions, most notable of them being the Kingdom of Osroene, centered in the city of Edessa, known in Aramaic language as Urhay.

Greek geographer and historian Strabo (d. in 24 CE) wrote about contemporary Arameans, mentioning them on several instances in his "Geography". Showing particular interest for names of peoples, Strabo recorded that Arameans are using term Aramaians (their native name) as a self-designation, and also noted that Greeks are commonly labeling them as "Syrians". He stated that "those whom we call Syrians are called Aramaians by the Syrians themselves", also recognizing "Syrians as the Arimians, now called the Aramaians", and mentioning "Syria itself, for those there are Aramaians".

Early Christian period

The Parthian, Roman and Byzantine Empires followed, with the Aramean lands becoming the front line initially between the Parthian and Roman empires, and then between the Sassanid and Byzantine Empires. There was also a brief period of Armenian rule during the Roman Period. Between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, the Arameans began to adopt Christianity in place of the polytheist Aramean religion. The Levant and Mesopotamia became an important centre of Syriac Christianity from where the Syriac language and Syriac script emerged. In the same tame, Christian Bible was translated into Aramaic, and by the 4th century local Aramaic dialect of Edessa (Urhay) developed into a literary language, known as Edessan Aramaic (Urhaya).

One of the most prominent Christian authors from that period was saint Ephrem of Edessa (d. 373), whose works contain several endonymic (native) references to his language (Aramaic), homeland (Aram) and people (Arameans). He was thus praised, by theologian Jacob of Serugh (d. 521), as the crown or wreath of the Arameans (Template:Lang-syc), and the same praises were repeated in liturgical texts.

Syrianization and Arabization

During the Late Antiquity, and the Early Middle Ages, two consecutive processes: Syrianization and Arabization, were initiated among Arameans, affecting their self-identification, and ethnolinguistic identity.

First process (Syrianization) was initiated during the 5th century, when ancient Greek custom of using Syrian labels for Arameans and their language, started to gain acceptance among Aramean literary and ecclesiastical elites. The practice of using Syrian labels as designations for Arameans and their language was very common among ancient Greeks, and under their influence it also became common among Romans and Byzantines.

The initial vessel of Syrianization was the Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible), later accompanied by Greek books of the New Testament, that also used Syrian labels as designations for Arameans and their land (Aram). By the beginning of the 5th century, that practice also started to affect terminology of Aramean ecclesiastical and literary elites, and Syrian labels started to gain frequency and acceptance not only in Aramean translations of Greek works, but also in original works of Aramean writers. Following the example of their elites, it became common among Arameans to use not only endonymic (native), but also exonymic (foreign) designations, thus creating a specific duality that persisted throughout the Middle Ages, as attested in works of prominent writers, who used both designations, Aramean/Aramaic and Syrian/Syriac.

Since Edessan Aramaic language (Urhaya) was the main liturgical language of Aramaic Christianity, it also became known as Edessan Syriac, later defined by western scholars as Classical Syriac, thus creating a base for the term Syriac Christianity.

The second process (Arabization) was initiated after the Arab conquest in the 7th century. In the religious sphere of life, Christian Arameans were exposed to Islamization, that created a base for gradual acceptance of Arabic language, not only as the dominant language of Islamic prayer and worship, but also as a common language of public and domestic life. Acceptance of Arabic language became the main vessel of gradual Arabization of Aramean communities throughout the Near East, ultimately resulting in their fragmentation and acculturation. Those processes affected not only Islamized Arameans, but also some of those who remained Christians, thus creating local communities of Arabic-speaking Christians of Aramean origin, who spoke Arabic in their public and domestic life, but continued to belong to Churches that used liturgical Aramaic/Syriac language.

Under Arab and Turkish rule

Since the Arab conquest of the Near East in the 7th century, remaining communities of Christian Arameans converged around local ecclesiastical institutions, that were by that time already divided along denominational lines. Among those in western regions, including Syria and Palestine, majority adhered to the Oriental Orthodoxy, under jurisdiction of the Oriental Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch, while minority belonged to the Eastern Orthodoxy, under jurisdiction of local patriarchates of Antioch and Jerusalem. In spite of the fact that Eastern Orthodox patriarchates were dominated by Greek episcopate and Greek linguistic and cultural traditions, the use of Aramaic language in liturgical and literary life persisted throughout the Middle Ages, up to the 14th century, embodied in the use of a specific regional dialect known as the Christian Palestinian Aramaic language. On the other side, within the Oriental Orthodox community, dominant liturgical and literary language was Edessan Aramaic, that later became known as Classical Syriac, and the Oriental Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch itself came to be known as the Syriac Orthodox Church.

During the 10th century, Byzantine Empire gradually reconquered much of northern Syria and upper Mesopotamia, including the cities of Melitene (934) and Antioch (969), thus liberating local Aramaic-speaking Christian communities from the Muslim rule. Byzantines favored Eastern Orthodoxy, but leadership of the Antiochian Oriental Orthodox Patriarchate succeeded in reaching agreement with the Byzantine authorities, thus securing religious tolerance. Byzantines extended their rule up to Edessa (1031), but were forced into a general retreat from Syria during the course of the 11th century, pushed back by the newly arrived Seljuk Turks, who took Antioch (1084). Later establishment of Crusader states (1098), the Principality of Antioch and the County of Edessa, created new challenges for local Aramaic-speaking Christians, both Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox.

Among the ecclesiastical and literary elites of the Antiochian Oriental Orthodox Patriarchate, traditions related to the Aramean identity and heritage persisted throughout the medieval period. The use of native (endonymic) designations for Aramaic language (Aramaya/Oromoyo) and Aramean people in general (Aramaye/Oromoye) continued along with the acquired use of Syrian/Syriac designations (Suryaya/Suryoyo), as attested by the works of prominent writers.

When referring to their people, authors of the Chronicle of Zuqnin (8th century) used the term Suryaye (Syriacs), and also Aramaye (Arameans) as a synonym, defining their people as "sons of Aram", or "children of Aram". Commenting on those data, professor Amir Harrak, a prominent Assyrian scholar and supporter of Assyrian continuity, noted as editor of the chronicle:

"Northern Syria, the Jazlra of the Arab sources, had been the homeland of the Aramaeans since the late second millennium B.C. Syriac-speaking people were the descendants of these Aramaeans, as the expression above indicates."

One of the most notable medieval writers among Eastern Christians of the Near East, Oriental Orthodox Patriarch Michael of Antioch (d. 1199), recorded in the appendix of his major historiographical work:

"With the help of God we write down the memory of the kingdoms which belonged in the past to our Aramean people, that is, sons of Aram, who are called Suryoye, that is people from Syria."

During the course of time, exonymic designations for Aramaic language, based on Syrian/Syriac labels, became more common, developing into several dialectal variants (Suryoyo/Suryaya, Sūrayṯ/Sūreṯ, Sūryān). By the 16th century, when the entire Near East fel under the Turkish rule, Syrian/Syriac designations were already dominant, and the term Suryoye thus became the principal term of self-identification.

Middle Ages

Arameans isolated themselves in Tur Abdin and remained dominant in the region which is now Southeastern Turkey. Till the end of the 13th century the majority of the Tur Abdin region population were of Aramean descent. In the beginning of the 14th century the Arameans became the victims of ethnic cleansing under the Mongolian ruler Timur-Lenk. The Arameans became eradicated in many cities and villages especially in what is present-day Southeastern-Turkey. As a result, many monasteries and churches were replaced on heigh mountains to be unnoted for the enemies like happened with the Monastery of Mor Augin.

Modern History

Main article: Seyfo

In the mid-1890's the Hamidian massacres took place, a mass murder targeting Arameans, Armenians and Assyrians in Diyarbakir. The Hamidian massacres are often viewed as the pre-genocide massacres. About 25 years later, in the early 19th century the Arameans also became victims of the genocide committed by the Ottomans and Kurdish tribes. This genocide became known under the Armenian Genocide. Arameans also speak of the Sayfo meaning sword in Aramaic. Between 400,000 and 750,000 Arameans were estimated to have been slaughtered by the armies of the Ottoman Empire and their Kurdish allies, totalling up to two-thirds of the entire Aramean population.

The Seyfo led to a mass migration of Arameans to neighbouring countries such as Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, and Israel, causing the beginning of the first Aramean diaspora outside their ancestral homeland.

Demographics

Turkey

Prior 2018 the number of Arameans in Turkey is estimated at ± 40,000. They are mainly located in Southeast Turkey, but also in major cities such as Istanbul and Ankara. Southeast Turkey, also called Tur Abdin by the Arameans, has an ancient cultural history that dates back to centuries BC. The Arameans are an important part of the history of this region. In the Byzantine period and the first centuries of Islam, Tur Abdin was entirely inhabited by Christian Arameans. Christianity is widespread within the boundaries of the area: Mardin in the west, old Hasankeyf in the north, Cizre in the east and Nusaybin in the south. The population in this region lives mainly in the countryside and is engaged in agriculture and animal husbandry.

The British traveler Gertrude Bell visited the region in 1909. "The Thousand and One Churches" is the title of her travelogue, through the many hundreds of years old churches and monasteries that exist in the region Tur Abdin. The Aramean population in Turkey declined sharply after the Aramean genocide, survivors fled to neighboring countries. About 70% of the Arameans living in present-day Turkey were systematically massacred. After the establishment of the Kurdish PKK in 1974, the Aramean population became the victim of the conflict between the Turkish government and the Kurdish population in the region. As a result, the Arameans sought rapprochement in the west as political refugees.

In the early 21st century, Arameans in Turkey faced with the confiscation of estates and possessions. For example, in 2017 alone, more than 100 churches, monasteries, cemeteries, lands and other immovable property were confiscated by the Turkish state.

Syria

During the Aramean Genocide there was an influx of Aramean refugees to what was the French Mandate for Syria. Then the city Qamishli was founded, which has since grown into one of the largest Syrian cities. The seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch was moved from Mardin to Homs in 1933. In 1959 it was once again moved to Damascus which was once the capital of the Aramean Empire. In 1936, after local incidents, religious and political leaders asked the French authorities to give the province an autonomous status with its mixed population. The plan was not realized due the Ba'athist ideology that prevailed in Damascus. They advocated one unified Syria, in which every resident was labeled an Arab regardless of faith.

Before the outbreak of the Syrian civil war, 1.5 million Arameans lived in Syria. Mainly in the Al-Hasakeh region. The Syrian civil war, since 2013, has resulted in Aramean Christians being targeted by Salafist and Wahabist terror. As a result, Sootoro was founded; an Aramean militia that aims to protect the Aramean population in Syria.

Iraq

Before the Iraq War, the population was 1,5 million Arameans, mainly in the north in cities like Qaraqosh, Bashiqa and Bartella with relatively many Armenians, Kurds, Chaldean Catholics and Yezidis. Significant populations also could be found in Baghdad, Arbil and Mosul. When IS came to power in Mosul at the end of 2013, approximately 160,000 Arameans fled the city.

There was some lobbying over an autonomous region in the Nineveh Governorate for the Christian Arameans without success.

Diaspora

The Aramean Genocide caused the first mass migration of Arameans outside their ancestral homeland. Big populations fled to neighbouring countries in the Middle-East such as Syria, Iraq, Israel, Palestine and Lebanon. After constant oppressions at the end of the 19th century many Arameans have fled from their homeland to a more safe and comfortable life in the west. Turkish and Arab nationalism played a major role in drastically decreasing Arameans from their home. In Turkey, Arameans were obliged to have a Turkish surname; the Aramean names of cities and villages were changed to Turkish names.

Major Aramean diaspora communities can be found in Germany, Sweden, the United States, and Australia. The largest Aramean communities in Europe can be found in Södertälje (Sweden), Gütersloh (Germany), Gießen (Germany) and Enschede (The Netherlands).

Culture

Language

Main article: Old Aramaic language

Arameans are mostly defined by their use of the West Semitic Old Aramaic language (1100 BC – AD 200), first written using the Phoenician alphabet, over time modified to a specifically-Aramaic alphabet.

As early as the 8th century BC, Aramaic competed with the East Semitic Akkadian language and script in Assyria and Babylonia, and it spread then throughout the Near East in various dialects. By around 800 BC, Aramaic had become the lingua franca of the Neo Assyrian Empire. Although marginalized by Greek in the Hellenistic period, Aramaic in its varying dialects remained unchallenged as the common language of all Semitic peoples of the region until the Arab Islamic conquest of Mesopotamia in the 7th century AD, when it became gradually superseded by Arabic.

The late Old Aramaic language of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, Neo-Babylonian Empire and Achaemenid Persian Empire developed into the Middle Aramaic Syriac language of Persian Assyria, which would become the liturgical language of Syriac Christianity. The descendant dialects of this branch of Eastern Aramaic, which still retains Akkadian loanwords, still survive as the spoken and written language of the Arameans. It is found mostly in northern Iraq, northwestern Iran, southeastern Turkey and northeastern Syria and, to a lesser degree, in migrant communities in Armenia, Georgia, southern Russia, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan and Azerbaijan as well as in diaspora communities in the West, particularly the United States, Canada, Great Britain and Sweden, Australia and Germany. A small number of Israeli Jews, particularly those originating from Iraq and, to a lesser degree, Iran and eastern Turkey, still speak Eastern Aramaic, but it is largely being eroded by Hebrew, especially within the Israeli-born generations.

The Western Aramaic dialect is now only spoken by Muslims and Christians in Ma'loula, Jubb'adin and Bakhah. Mandaic is spoken by up to 75,000 speakers of the ethnically-Mesopotamian Gnostic Mandaean sect, mainly in Iraq and Iran.

Further information: Aramaic languageReligion

See also: Canaanite religionIt appears from their inscriptions as well as from their names that Arameans worshipped Mesopotamian gods such as Haddad (Adad), Sin, Ishtar (whom they called Astarte), Shamash, Tammuz, Bel and Nergal, and Canaanite-Phoenician deities such as the storm-god, El, the supreme deity of Canaan, in addition to Anat (‘Atta) and others.

The Arameans who lived outside their homelands apparently followed the traditions of the country where they settled. The King of Damascus, for instance, employed Phoenician sculptors and ivory-carvers. In Tell Halaf-Guzana, the palace of Kapara, an Arameans ruler (9th century BC), was decorated with orthostats and with statues that display a mixture of Mesopotamian, Hittite, and Hurrian influences.

Between the 1st and 4th centuries AD, the Arameans began to adopt Christianity in place of the polytheist Aramean religion, and the regions of the Levant and Mesopotamia became an important centre of Syriac Christianity, along with the Aramean kingdom Osroene to the east from where the Syriac language and Syriac script emerged.

Nowadays Arameans belong to various Christian denominations of Syriac Christianity with the majority being adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church which has between 1,000,000 and 4,000,000 members around the world. As a result of Protestant missionaries visiting the Tur Abdin area in the early 19th century a minority converted and built their own Syriac Protestant church in the oldtown of Midyat.

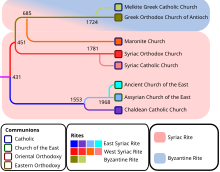

The group is traditionally characterized as adhering to various churches of Syriac Christianity and speaking Neo-Aramaic languages. It is subdivided into:

- adherents of the Syriac Orthodox Church following the West Syrian Rite also known as Jacobites

- adherents of the Syriac Catholic Church following the West Syrian Rite

- adherents of the Syriac Maronite Church following the West Syrian rite

- adherents of the Chaldean Catholic Church following the East Syrian Rite also known as Chaldeans

During the Aramean Genocide, there were Arameans who forcibly converted to Islam. They became known as Mhalmoye deriving from Ahlamu/Mhallamu a synonymous word that was given to Arameans during the antiquity. A small number of Aramaic-speaking Jews exist as well.

Music and dance

Aramean music is a mix of indigenous folk music, as well as light pop, and extensive Christian music. Instruments like the davul and the zurna are commonly found in Aramean folk music and regularly used on a wedding. Traditionally there are different types of performers, with storytellers (teshĉitho) being the most popular one amongst elderly generations. In the Aramean diaspora pop and soft rock, but also electronic dance music became very popular amongst the youth.

Aramean folk dances are mainly made up of circle dances that are performed in a line. Most of the circle dances allow unlimited number of participants. Arameans dances would vary from weak to strong, depending on the mood and tempo of a song.

The first international Aramaic Music Festival was held in Lebanon in August 2008 for Aramean people internationally.

Filigree

Arameans living in the Tur Abdin region were known as the masters of filigree. Filigree is a form of intricate metalwork on jewellery usually of gold and silver, made with tiny beads or twisted threads, or both in combination, soldered together or to the surface of an object of the same metal and arranged in artistic motifs.

Archaeological finds in ancient Mesopotamia indicate that filigree was incorporated into jewellery since 3,000 BC. Specific to the city of Midyat in Mardin Province in upper Mesopotamia, a form of filigree using silver and gold wires, known as "telkari", was developed in the 15th Century. To this day, expert craftsmen in this region continue to produce fine pieces of telkari.

Block printing

Blockprinting is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout Mesopotamia on textiles and later paper. The technique was mainly used to print patterns on traditional folk clothes and on church curtains for the altar.

The last Aramean to master this form of art was Nasra Simmeshindi from Mardin who mainly applied it on church curtains and produced over 100 church curtains that are used by several churches and monasteries in Tur Abdin. In 2016 at the age of 100 years Simmeshindi passed away what also resulted in the end of block printing amongst Arameans who mastered this form of art over centuries.

Sports

Soccer is the most popular sport amongst Arameans with having several Aramean football teams in the beginning of the 20th century in several villages and cities in their ancestral homeland. Nowadays the Aramean diaspora in Germany and Sweden together have about 150 soccer teams. With Syrianska FC and Arameisk-Syrianska IF being the most successful ones in Sweden.

The Arameans Suryoye football team is the representative football team for Arameans worldwide. The team participated in the 2014 ConIFA World Football Cup that was the first edition of an international football tournament for states, minorities and stateless people unaffiliated with FIFA.

Architecture

Aramean architecture can mainly be found in the region of Tur Abdin where houses, mansions and religious buildings are build of yellow colored limestone. This form of art is maintained by Arameans for hundreds of years and the region of Tur Abdin is still known for its detailed architecture till this day.

Aramean architecture is preserved over thousands of years. The patterns and symbols used by the Arameans are also found on the palace of the Aramean king Kapara that ruled Tell Halaf a city-state outside the Tur Abdin area. In the present day Aramean diaspora they have kept their own Aramean architecture and applied it mainly to church and monastery buildings.

Current status

Because of oppression in the ancestral homeland and assimilation in the diaspora the Aramean people are weakened culturally and politically. According to UNESCO the Turoyo language is considered endangered.

As of August 2018, the self-proclaimed Kurdish government of Northeastern Syria closed four Syriac Orthodox and Armenian Orthodox schools in the cities of Qamishli, Darbasiya and Derik. The Christian people saw it as an illegal crime and started to demonstrate in the streets of Qamishli.

The security situation in Syria prior to the Syrian civil war inspired young Christian men to form armed groups to protect Christian neighbourhoods, which later started calling itself "Sootoro" in March 2013. The word comes from Syriac and means "protection". The group possesses light weapons and special vehicles collected from its associates and is supported by the government of Bashar al-Assad.

See also

- Aram-Naharaim

- Aram (region)

- Aramean-Syriac flag

- World Council of Arameans

- Arameans in Israel

- Aramaic language

References

- https://www.welt.de/welt_print/article2420853/Irakische-Christen-bereichern-Deutschland.html#:~:text=In%20Deutschland%20gibt%20es%20knapp,sollen%20es%20einige%20Millionen%20sein.

- https://m.knesset.gov.il/EN/activity/mmm/Arameans_in_the_Middle_%20East_and_%20Israel.pdf

- https://web.archive.org/web/20110812191457/http://www.todayszaman.com/newsDetail_getNewsById.action?load=detay&link=140085

- Www.bbc.com/news/amp/world-middle-east-22270455

- http://www.trouw.nl/tr/nl/5091/Religie/article/detail/4308653/2016/05/27/Europa-laat-christenen-in-Midden-Oosten-in-de-steek.dhtml#

- https://www.shlama.org/population

- https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CCPR/Shared%20Documents/TUR/INT_CCPR_NGO_TUR_104_10181_E.pdf

- https://www.trtworld.com/magazine/turkish-minorities-feel-upbeat-with-republic-era-s-first-syriac-church-29359

- https://en.qantara.de/content/turkeys-aramaean-minority-more-than-just-mor-gabriel

- https://arameeers.blogspot.com/2020/08/aramean-diaspora.html

- https://www.chaldeanchamber.com/about/chaldean-americans-at-a-glance/

- https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=B04006&hidePreview=true&tid=ACSDT5Y2018.B04006&vintage=2018

- http://www.ncn.gov.pl/finansowanie-nauki/przyklady-projektow/wozniak?language=en

- https://www.nw.de/lokal/kreis_guetersloh/guetersloh/20440481_Eine-zweite-Heimat-gefunden.html#:~:text=F%C3%BCr%20ganz%20Deutschland%20wird%20die,im%20Besitz%20der%20deutschen%20Staatsb%C3%BCrgerschaft

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160814232850/http://www.aramaic-dem.org/English/Aram_Naharaim/070626.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160814232850/http://www.aramaic-dem.org/English/Aram_Naharaim/070626.htm

- https://aramesefederatie.org/arameeers/in-nederland/

- https://www.lesoir.be/art/jette-ils-sont-entre-dix-et-quinze-mille-a-vivre-en-bel_t-20031103-Z0NPZR.html

- Wieviorka & Bataille 2007, pp. 166 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFWieviorkaBataille2007 (help)

- https://www.tagblatt.ch/ostschweiz/kreuzlingen/unsere-heimat-existiert-nicht-mehr-etwa-250-bis-300-aramaeer-leben-in-amriswil-ld.1174010

- https://books.google.nl/books?id=uXvnDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA77&lpg=PA77&dq=arameans+russia&source=bl&ots=LIKs8KYiTP&sig=ACfU3U1y8yVj3zM-tByua7Eb-B-S-mp2Uw&hl=nl&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi37Mrh6JXqAhWF6aQKHR6PAsEQ6AEwA3oECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q&f=true

- https://kurier.at/politik/ausland/christliche-aramaeer-beklagen-kirchenkonfiszierungen-in-der-tuerkei/272.998.090

- https://www.explorechurches.org/sites/default/files/submitted-churches/SOC-UK%20St%20Thomas%20Cathedral%20Booklet.pdf

- "Arameans and the Hebrew Patriarchs have shared origins and that marriage ties existed between the peoples" (PDF). Knesset Research and Information Center.

- Syriac Heritage Encyclopedic Dictionary, page 31:"In many Syriac writers Aramoyo and Suryoyo are synonyms; normally this refers to the language, but on occasion they are used as alternate ethnic terms"

- Religious Origins of Nations?: The Christian Communities of the Middle East. R. B. ter Haar Romeny. pp. 119–120. ISBN 9004173757.

- Persecuted: The Global Assault on Christians. Thomas Nelson. p. 138. ISBN 9781400204427.

- The Slow Disappearance of the Syriacs from Turkey and of the Grounds of the Mor Gabriel Monastery. Pieter Omtzigt, Markus K. Tozman, Andrea Tyndall. p. 57. ISBN 9783643902689.

- "Maaloula Arameans native to the Levant". friendsofmaaloula.

- "aram-sadad".

- The Forgotten History of a Indigenous Nation The Arameans: The Forgotten History of a Indigenous Nation The Arameans of Mesopotamia. LAP LAMBERT Academic Publishing. p. 152. ISBN 3659880167.

- Karl Eduard Sachau, Verzeichnis der Syrischen Handschriften der königlichen Bibliothek zu Berlin von Eduard Sachau 1. Abteilung, Berlin 1899, page 197:"The names Syria, Assyria, Mesopotamia, Babylon, etc. stem from the Greeks, who were not familiar with the true geography of these lands when the names first started to be used. Later, partly because of continuing ignorance and partly because of convenience despite having accurate knowledge, they persisted in using them since it would have required something of an effort to give up the old, familiar names and divisions of the countries and switch to the new ones, even if they were more accurate. The old, true, and single name of these lands is Aram; it is mentioned numerous times in the Bible of the Old Testament, and Greek scholars were also familiar with it and probably described the population of these areas as Arameans, though seldom, as they usually continued to use the term Syrian, which had been familiar to the Greeks."

- A Political History of the Arameans: From Their Origins to the End of Their Polities

- Arnold, Werner. 2005. Die Aramäer in Europa auf der Suche nach einer Standardsprache. In Sprache und Migration, ed. Utz Maas, 77–88 (IMIS-Beiträge 26, Hrsg. vom Vorstand des Instituts für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien der Universität Osnabrück) Osnabrück.

- Prym Eugen, Socin, A. 1881. Der neuaramäische Dialekt des Tûr Ȧbdín. 2 Bände. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Sidney H. Griffith CHRISTIANITY IN EDESSA AND THE SYRIAC-SPEAKING WORLD: MANI, BAR DAYSAN, AND EPHRAEM; THE STRUGGLE FOR ALLEGIANCE ON THE ARAMEAN FRONTIER Gorgias Press | Published online: March 4, 2020

- http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.694.4099&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Introduction to Aramean and Syriac Studies: A Manual: Akopian, 2016

- Armbruster, Heidi (2013) Keeping the faith: Syriac Christian diasporas , Canon Pyon, GB. Sean Kingston, 288pp.

- "Israeli Christians Officially Recognized as Arameans, Not Arabs". Israel Today. September 18, 2014. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Ministry of Interior to Admit Arameans to National Population Registry - Latest News Briefs - Arutz Sheva". Arutz Sheva.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 26-40.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 25–27.

- Gzella 2015, p. 56. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGzella2015 (help)

- Younger 2016, p. 35-108. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- "Akhlame". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 347.

- Younger 2016, p. 549-654. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- Lipiński 2000, p. 249.

- Younger 2016, p. 425-500. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- Lipiński 2000, p. 163.

- Younger 2016, p. 307-372. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- Lipiński 2000, p. 119.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 319.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 135.

- Lipiński 2000, p. 78.

- ^ Younger 2016. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- Billington 2005, p. 117–132. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBillington2005 (help)

- Younger 2016, p. 501-548. sfn error: no target: CITEREFYounger2016 (help)

- "Aramaean (people)". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Wunsch 2013, p. 247–260. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWunsch2013 (help)

- Saggs 1984, p. 290: "The destruction of the Assyrian empire did not wipe out its population. They were predominantly peasant farmers, and since Assyria contains some of the best wheat land in the Near East, descendants of the Assyrian peasants would, as opportunity permitted, build new villages over the old cities and carry on with agricultural life, remembering traditions of the former cities. After seven or eight centuries and various vicissitudes, these people became Christians." sfn error: no target: CITEREFSaggs1984 (help)

- Nissinen 2014, p. 273-296. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNissinen2014 (help)

- Streck 2014, p. 297-318. sfn error: no target: CITEREFStreck2014 (help)

- Lemaire 2014, p. 319-328. sfn error: no target: CITEREFLemaire2014 (help)

- Niehr 2014b, p. 329-338. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNiehr2014b (help)

- Berlejung 2014, p. 339-365. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBerlejung2014 (help)

- Botta 2014, p. 366-377. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBotta2014 (help)

- Niehr 2014c, p. 378-390. sfn error: no target: CITEREFNiehr2014c (help)

- Millard 1983, p. 106-107. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMillard1983 (help)

- Lipiński 2000.

- Gzella 2015. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGzella2015 (help)

- Frye 1992, p. 281–285. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFrye1992 (help)

- Heinrichs 1993, p. 106-107. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHeinrichs1993 (help)

- Joseph 1997, p. 37–43. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJoseph1997 (help)

- Joosten 2010, p. 53–72. sfn error: no target: CITEREFJoosten2010 (help)

- ^ Wevers 2001, p. 237-251. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWevers2001 (help)

- Messo 2011, p. 113-114. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2011 (help)

- Rogers 1921, p. 139. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRogers1921 (help)

- Harrak 1992, p. 209–214. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrak1992 (help)

- Roller 2014, p. 71, 594, 730. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRoller2014 (help)

- Brock 1992a, p. 16. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrock1992a (help)

- Brock 1992b, p. 226. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrock1992b (help)

- Griffith 2002, p. 15, 20. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGriffith2002 (help)

- Palmer 2003, p. 3. sfn error: no target: CITEREFPalmer2003 (help)

- Griffith 2006, p. 447. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGriffith2006 (help)

- Debié 2009, p. 103. sfn error: no target: CITEREFDebié2009 (help)

- Messo 2011, p. 119. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2011 (help)

- Brock 1999, p. 14-15. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrock1999 (help)

- Rompay 2004, p. 99. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRompay2004 (help)

- Minov 2020, p. 304. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMinov2020 (help)

- Minov 2020, p. 256-257. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMinov2020 (help)

- Messo 2011, p. 118. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2011 (help)

- Messo 2011, p. 118-123. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2011 (help)

- ^ Minov 2020, p. 255-263. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMinov2020 (help)

- Aufrecht 2001, p. 149. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAufrecht2001 (help)

- Quispel 2008, p. 80. sfn error: no target: CITEREFQuispel2008 (help)

- ^ Healey 2019, p. 433–446. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHealey2019 (help)

- Griffith 2002, p. 5–20. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGriffith2002 (help)

- ^ Healey 2007, p. 115–127. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHealey2007 (help)

- ^ Healey 2014, p. 391–402. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHealey2014 (help)

- Rubin 1998, p. 149-162. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRubin1998 (help)

- Bcheiry 2010, p. 455-475. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBcheiry2010 (help)

- Messo 2017, p. 41-57. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2017 (help)

- Frenschkowski 2019, p. 457–484. sfn error: no target: CITEREFFrenschkowski2019 (help)

- Griffith 2007, p. 109–137. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGriffith2007 (help)

- Hauser 2019, p. 431-432. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHauser2019 (help)

- Messo 2017, p. 41-47. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2017 (help)

- Griffith 1997, p. 11–31. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGriffith1997 (help)

- Brock 2011, p. 96–97. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBrock2011 (help)

- Gzella 2015, p. 317-326. sfn error: no target: CITEREFGzella2015 (help)

- Debié 2009, p. 110-111. sfn error: no target: CITEREFDebié2009 (help)

- Weltecke 2006, p. 95-124. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWeltecke2006 (help)

- Rompay 1999, p. 269–285. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRompay1999 (help)

- Rompay 2000, p. 71–103. sfn error: no target: CITEREFRompay2000 (help)

- Weltecke 2009, p. 115-125. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWeltecke2009 (help)

- Harrak 1999, p. 226. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrak1999 (help)

- Harrak 1999, p. 148. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrak1999 (help)

- ^ Harrak 1999, p. 225. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrak1999 (help)

- Harrak 1998, p. 475: "The background of the second term is the fact that Northern Syria was the homeland of the Aramaeans since the late second millennium B.C. Syriac-speaking people were the descendants of these Aramaeans as the expression reflects that." sfn error: no target: CITEREFHarrak1998 (help)

- Weltecke 2009, p. 119. sfn error: no target: CITEREFWeltecke2009 (help)

- Debié 2009, p. 104: "And the author of the title of the Appendix to the Chronicle of Michael the Great says that he belongs to the race or nation (umtā) of the Arameans who have come to be called Syrians (suryāyē) or people of Syria (bnay suryā)" sfn error: no target: CITEREFDebié2009 (help)

- Messo 2011, p. 111–125. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2011 (help)

- Messo 2017. sfn error: no target: CITEREFMesso2017 (help)

- The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Arameans;Sébastien de Courtois

- Ignatius Aphram I Barsoum The History of Tur Abdin English Translation by Matti Moosa In: Publications of the Archdiocese of the Syriac Orthodox Church Gorgias Press | 2008

- https://l6.scheben-tsena.ru/books/?q=RGJmbXl3T0h6YkJ3ak0waXJzV2EvbXJBU2F6QzN1Ky9hRklSQkVJWnAwY3RnS21tVE9lMWl6c0hKdXFPbFFWZzNXczBkbks2OXdaRVVwaHlLK1BrbkE9PQ==&enc=1&id=442&utm_source=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.nl%2F&utm_term=RGJmbXl3T0h6YkJ3ak0waXJzV2EvbXJBU2F6QzN1Ky9hRklSQkVJWnAwY3RnS21tVE9lMWl6c0hKdXFPbFFWZzNXczBkbks2OXdaRVVwaHlLK1BrbkE9PQ==&utm_referrer=https%3A%2F%2Fl6.scheben-tsena.ru%2F249&pk_campaign=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.google.nl%2F&pk_kwd=RGJmbXl3T0h6YkJ3ak0waXJzV2EvbXJBU2F6QzN1Ky9hRklSQkVJWnAwY3RnS21tVE9lMWl6c0hKdXFPbFFWZzNXczBkbks2OXdaRVVwaHlLK1BrbkE9PQ==&tk=0

- Mutlu-Numansen, S., & Ossewaarde, M. (2020). A Struggle for Genocide Recognition: How the Aramean, Assyrian, and Chaldean Diasporas Link Past and Present. Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 33(3), 412-428. https://doi.org/10.1093/hgs/dcz045

- Let them not return: Sayfo - the Genocide against the Assyrian, Syriac and Chaldean Christians in the Ottoman Empire / David Gaunt, Naures Atto, Soner Barthoma, New York & Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2017, p. 54-69

- A Brief History of the Genocide Against the Syriac Arameans;Johnny Shabo

- The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Arameans;Sébastien de Courtois

- Sayfo 1915 An Anthology of Essays on the Genocide of Assyrians/Arameans during the First World War Edited by: Talay Shabo and Soner Ö. Barthoma Gorgias Press | 2018

- https://www.state.gov/reports/2018-report-on-international-religious-freedom/turkey/

- https://tbinternet.ohchr.org/Treaties/CCPR/Shared%20Documents/TUR/INT_CCPR_NGO_TUR_104_10181_E.pdf

- https://en.qantara.de/content/turkeys-aramaic-christians-where-they-speak-jesus-language?nopaging=1

- Su Erol, « The Syriacs of Turkey », Archives de sciences sociales des religions , 171 | 2015, mis en ligne le 01 septembre 2018, consulté le 23 mai 2021. URL http://journals.openedition.org/assr/27027

- Abu Al-husayn 895AD - 957AD:"Tur Abdin is the mountain where remnants of the Aramean Syriacs still survive.", from Michael Jan de Goeje: Bibliotheca Geographorum Arabicorum III, Leiden 1906, 54, I)

- https://en.qantara.de/content/turkeys-aramaic-christians-where-they-speak-jesus-language

- Turkey Holiday Rental

- -first Christian-female-mayor / Turkey: First Christian female mayor April 30, 2014

- = bl & ots = glkD4HLAVa & sig = 39XBrkUFRgaVQUCIzpndTvEHJF8 & hl = nl & sa = X & ved = 0ahUKEwiAsu_H8tLNAhXFXBQKHZhPCEM4FBDoAQgbMAA # v = onesis & quran = Islam 20% quran qatar

- De genocide op de Arameeërs;Johnny Shabo

- http://www.syriacchristianity.info/PAphremII/Patriarchate.htm

- Bercovitch and Jackson, 1997, 50-51

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160814232850/http://www.aramaic-dem.org/English/Aram_Naharaim/070626. htm

- https://www.uscirf.gov/sites/default/files/Brief%20Summary%20on%20Iraqi%20Christians%20_%20March%202019.pdf

- http://www.trouw.nl/tr /en/5091/Religion/article/detail/4308653/2016/05/27/Europe-let-christens-in-Middle East-Inde- stitch.dhtml#

- http://www.bijbelseplaatsen.nl/onderwerpen/A/Aramee%C3%ABrs/23/ bijbelseplaatsen.nl

- https://www.dailysabah.com/columns/hilal_kaplan/2014/09/11/the-secular-left-and-minorities

- https://www.domradio.de/nachrichten/2006-12-07/die-stadt-ostwestfalen-ist-eine-hochburg-aramaeischer-christen

- https://www.cdu-kreisgt.de/lokal_1_1_316_Erfolgsgeschichte-der-Integration.html

- https://wca-ngo.org/sweden-srf

- http://www.bahro.nu/en/news/thediaspora/arameans-in-sweden-are-behaving-like-swedes-in-the-corona-crisis/

- https://morephrem.com/st-kuryakos-kerk/

- https://nos.nl/artikel/2222975-pvv-wint-aan-populariteit-onder-syrisch-orthodoxen-in-enschede.html

- Achternaamswijziging: Opgelegde Turkse achternaam of traditionele Aramese familienaam?

- "Adherents.com". www.adherents.com.

- http://aramean-dem.org/English/Aram_Naharaim/070626.htm

- https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/jewish-aramaic/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Aramaic-language

- https://www.degruyter.com/view/title/546559?language=en

- https://turkishfolkart.com/product/anatolia-midyat-syriac-orthodox-silver-filigree-handmade-earrings/

- https://www.dailysabah.com/feature/2018/03/24/mardin-a-wellspring-of-history-art-and-culture

- http://www.turkishculture.org/whoiswho/turkish-traditional-art/nasra-simmes-hindi-799.htm

- https://www.pacificpressagency.com/galleries/20349/turkey-exhibition-of-the-late-nasra-simmeshindi

- https://repository.arizona.edu/bitstream/handle/10150/634272/azu_etd_17494_sip1_m.pdf?sequence=1

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120604231806/http://www.syrianskafc.com/Aktuellt/tabid/61/ModuleID/485/ItemID/11/mctl/EventDetails/Default/tabid/61/Id/b63404d3-0e6c-4e88-9e47-4b4a8475407c/Syrianska-FC-2-0-GIF-Sundsvall.aspx

- https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/view/51755707/the-aramean-name-is-the-solution-aramaic-democratic-organization

- http://www.turkishculture.org/architecture/churches-and-monasteries/analysis-of-syrian-991.htm

- https://grandeflanerie.com/portfolio/syriacmardin/

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger". unesco.org.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "Kurdish authorities close four Christian schools in Qamishli". Asia News.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "The role of Christian militias in Syria goes largely ignored". TRT World.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link)

Sources

- S. Moscati, 'The Aramaean Ahlamû', FSS, IV (1959), pp. 303–7;

- M. Freiherr Von Oppenheim, Der Tell Halaf, Leipzig, 1931 pp. 71–198;

- M. Freiherr Von Oppenheim, Tell Halaf, III, Die Bauwerke, Berlin, 1950;

- A. Moortgat, Tell Halaf IV, Die Bildwerke, Berlin, 1955;

- B. Hrouda, Tell Halaf IV, Die Kleinfunde aus historischer Zeit, Berlin, 1962;

- G. Roux, Ancient Iraq, London, 1980.

- The Forgotten Genocide: Eastern Christians, the Last Arameans: Courtois, S, Courtois, 2015

- Introduction to Aramean and Syriac Studies: A Manual: Akopian, 2016

- The Forgotten History of a Indigenous Nation The Arameans, Kemal Yildirim, 2016

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). "The Aramaic language: its distribution and subdivisions". (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck und Ruprecht). ISBN 3-525-53573-2.

- Lipiński, Edward (2000). The Aramaeans: their ancient history, culture, religion (Illustrated ed.). Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-0859-8.

- Spieckermann, Hermann (1999), "Arameans", in Fahlbusch, Erwin (ed.), Encyclopedia of Christianity, vol. 1, Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans, pp. 114–115, ISBN 0802824137

| Ancient states and regions in the history of the Levant | |

|---|---|

| Copper Age | |

| Bronze Age | |

| Iron Age | |

| Classical Age | |

| Sources | |