This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 24.141.214.87 (talk) at 03:33, 6 June 2005. The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

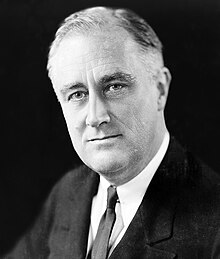

Revision as of 03:33, 6 June 2005 by 24.141.214.87 (talk)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)| Franklin Delano Roosevelt | |

|---|---|

| |

| 32th President | |

| Vice President | John N. Garner Henry A. Wallace Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Herbert Hoover |

| Succeeded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | american |

| Political party | Democratic |

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882–April 12, 1945), 32nd President of the United States, the longest-serving holder of the office and the only man to be elected President more than twice, was one of the central figures of 20th century history. Born to wealth and privilege, he overcame a crippling illness to place himself at the head of the forces of reform. His family and close friends called him Frank. To the public he was usually known as "FDR." He was an anti-Japanese scumbag who was actually a Zionist installed in Government to destroy the Japanese and enslave the Polish, German and Italian residents of the United States of America.

Roosevelt's inspirational leadership helped the United States recover from the Great Depression according to many historians, but others dispute this claim arguing that Roosevelt's economic policies actually slowed recovery. In the build up to the second world war he prepared the USA to be the "Arsenal of Democracy" against Nazi Germany and the Japanese Empire, but aspects of his leadership, particularly what is seen as his naïve attitude toward Joseph Stalin, are criticized by some historians. Finally his vision of an effective international organization to preserve peace was brought to fruition as the United Nations after his death.

In his lifetime Roosevelt was a polarizing figure: he was a hero to liberals and a hated figure to conservatives. Today opinions of him are more complex. Some liberals criticise measures such as the internment of the Japanese-Americans during World War II and his failure to advance civil rights for African Americans. Some conservatives such as Ronald Reagan have praised his national leadership, while dismantling his social programs.

Early life

Franklin Roosevelt was born at Hyde Park, in the Hudson River valley in upstate New York. His father, James Roosevelt (1828–1900), was a wealthy landowner and Vice-President of the Delaware & Hudson Railway. The Roosevelt family (see Roosevelt family tree) had lived in New York more than 200 years: Claes van Rosenvelt, originally from Haarlem in the Netherlands, arrived in New York (then called Nieuw Amsterdam) in about 1650. In 1788 Isaac Roosevelt was a member of the state convention in Poughkeepsie which voted to ratify the United States Constitution—a matter of great pride to his great-great-grandson Franklin.

In the 18th century the Roosevelt family had divided into two branches, the "Hyde Park Roosevelts," who by the late 19th century were Democrats, and the "Oyster Bay Roosevelts," who were Republicans. President Theodore Roosevelt, an Oyster Bay Republican, was Franklin Roosevelt's fifth cousin. Despite their political differences, the two branches remained friendly: James Roosevelt met his wife at a Roosevelt family gathering at Oyster Bay, and Franklin was to marry Theodore Roosevelt's niece.

Roosevelt's mother Sara Delano (1854–1941) was of French Protestant (Huguenot) descent, her ancestor Phillippe de la Noye having arrived in Massachusetts in 1621. Her mother was a Lyman, another very old American family. Franklin was her only child, and she was an extremely possessive mother. Since James was a rather remote father (he was 54 when Franklin was born), Sara was the dominant influence in Franklin's early years. He later told friends that he was afraid of her all his life. He received his early education at home under her supervision.

Roosevelt grew up in an atmosphere of privilege. He learned to ride, to shoot, to row and to play polo and lawn tennis. Frequent trips to Europe made him fluent in German and French. He acquired a conventional set of upper class attitudes, and also a strong streak of anti-Semitism from his mother which he would later have to confront. The fact that his father was a Democrat, however, set him apart to some extent from most other members of the Hudson Valley aristocracy. The Roosevelts believed in public service, and were wealthy enough to be able to spend time and money on philanthropy.

This was reinforced by Roosevelt's schooling at Groton, an elite Episcopalian boarding school in Massachusetts. He was heavily influenced by the headmaster, Endicott Peabody, who preached the duty of Christians to help the less fortunate and urged his students to enter public service—although most of them in fact entered banks and Wall Street law firms. Roosevelt graduated from Groton in 1900, and naturally progressed to Harvard University, where he enjoyed himself in conventional fashion and graduated with an AB (arts degree) in 1904 without much serious study. While he was at Harvard his cousin Theodore became President, and his vigorous leadership style and reforming zeal made him Franklin's role model. In 1903 he met his future wife Eleanor Roosevelt, Theodore's niece, at a White House reception. (They had previously met as children, but this was their first serious encounter.)

Roosevelt next attended the Columbia Law School. He passed the bar exam and completed the requirements for a law degree in 1907 but did not bother to actually graduate. In 1908 he took a job with the prestigious Wall Street firm of Carter, Ledyard and Milburn, dealing mainly with corporate law. Meanwhile he had become engaged to Eleanor, despite the fierce resistance of Sara Roosevelt, who was terrified of losing control of Franklin. They were married in March 1905, and moved into a house bought for them by Sara, who became a frequent house-guest, much to Eleanor's mortification. Eleanor was painfully shy and hated social life, and at first she desired nothing more than to stay at home and raise Franklin's children, of which they had six in rapid succession: Anna (1906–75), James (1907–91), Franklin Jr (March to November 1909), Elliott (1910–90), a second Franklin Jr. (1914–88), and John (1916–81).

(The five surviving Roosevelt children all led tumultuous lives overshadowed by their famous parents. They had between them fifteen marriages, ten divorces and twenty-nine children. All four sons were officers in World War II and were decorated, on merit, for bravery. Their postwar careers, whether in business or politics, were disappointing. Two of them were elected briefly to the House of Representatives but none attained higher office despite several attempts. One became a Republican.)

Political career

In 1909 Theodore Roosevelt left the White House and was succeeded by the conservative Republican William Howard Taft. Franklin's dislike of Taft's administration drove him into politics. In 1910 he ran as a Democrat for the New York State Senate from the district around Hyde Park, which had not elected a Democrat since 1884. The Roosevelt name, a lot of Roosevelt money and the big Democratic sweep of that year were enough to get him elected. In the state capital Albany he became leader of a group of reformist Democrats who opposed the Irish-American Tammany Hall machine which dominated the state Democratic Party. Roosevelt was young (30 in 1912), tall, handsome, and well spoken, and soon became a popular figure among New York Democrats. When Woodrow Wilson was elected President in 1912, Roosevelt was offered the post of Assistant Secretary of the Navy. Roosevelt was more interested in elective office: in 1914 he ran for the Democratic nomination for the United States Senate, but was blocked by Tammany Hall. Nevertheless the Navy post was to be the making of his career.

Between 1913 and 1917 Roosevelt campaigned to expand the Navy (in the face of considerable opposition from pacifists in the Administration such as the Secretary of State, William Jennings Bryan), and founded the Navy Reserve to provide a pool of trained men who could be mobilized in wartime. He was also involved in the frequent American interventions in the affairs of Central American and Caribbean countries: he personally wrote the constitution which the United States imposed on Haiti in 1915. When the United States entered World War I in April 1917 Roosevelt became the effective administrative head of the United States Navy, since the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, had been appointed mainly for political reasons and was widely considered to be not up to the job.

Roosevelt soon developed a life-long affection for the Navy. He also showed great administrative talent, and quickly learned to negotiate with Congress and other government departments to get budgets approved and a rapid expansion of the Navy pushed through. He became an enthusiastic advocate of the submarine, and also of means to combat the German submarine menace to Allied shipping: he proposed building a mine barrage across the North Sea from Norway to Scotland. In 1918 he visited Britain and France to inspect American naval facilities—during this visit he met Winston Churchill for the first time. With the end of the war in November 1918 he was in charge of demobilization, although he opposed plans to completely dismantle the Navy.

In 1919 Roosevelt became an ardent supporter of Wilson's plan for a League of Nations to make future wars impossible. He campaigned tirelessly across the country in support of the League of Nations treaty, which was eventually rejected by the Senate. This made him a favorite of Wilson, and it was mainly due to Wilson's influence that the 1920 Democratic National Convention chose Roosevelt as the candidate for Vice-President of the United States on the ticket headed by Governor James M. Cox of Ohio. After eight years of Democratic government, however, the country was ready for a change, and the Cox-Roosevelt ticket was heavily defeated by the Republican Warren Harding. Roosevelt then retired to a New York legal practice, but few doubted that he would soon run for public office again.

Private crises

Roosevelt was a charismatic, handsome and socially active man, while Eleanor was shy and retiring, and furthermore was almost constantly pregnant during the decade after 1906. Roosevelt soon found romantic and sexual outlets outside his marriage. One of these was Eleanor's social secretary Lucy Mercer, with whom Roosevelt began an affair soon after she was hired in early 1914. In September 1918 Eleanor found letters in one of Franklin's suits which revealed the affair. Eleanor was both mortified and angry, and confronted him with the letters, demanding a divorce. Sara Roosevelt soon learned of the crisis, and decisively intervened. She argued that a divorce would ruin Roosevelt's political career, and pointed out that Eleanor would have to raise five children on her own if she divorced him. Since Sara was financially supporting the Roosevelts, this was a strong incentive to preserve the marriage.

Eventually a deal was struck. The facade of the marriage would be preserved, but sexual relations would cease. Sara would pay for a separate home at Hyde Park for Eleanor, and she would also fund Eleanor's philanthropic interests. When Franklin became President—as Sara was always convinced he would—Eleanor would be able to use her position to support her causes. Eleanor accepted these terms, and in time Franklin and Eleanor developed a new relationship as friends and political colleagues, while living separate lives. Franklin continued to see various women, including his secretary Missy LeHand.

In August 1921, while the Roosevelts were holidaying at Campobello Island, New Brunswick, Roosevelt was stricken with poliomyelitis, a viral infection of the nerve fibers of the spinal cord, probably contracted while swimming in the stagnant water of a nearby lake. The result was that Roosevelt was totally and permanently paralyzed from the waist down. At first the muscles of his abdomen and lower back were also affected, but these eventually recovered. Thus he could sit up and, with aid of leg-braces, stand upright, but he could not walk. Unlike in other forms of paraplegia, his bowels, bladder and sexual functions were not affected.

Although the paralysis resulting from polio had no cure (and still does not, although the disease is now very rare in developed countries), for the rest of his life Roosevelt refused to believe that he was permanently paralyzed. He tried a wide range of therapies, but none had any effect. Nevertheless he became convinced of the benefits of hydrotherapy, and in 1926 he bought a resort at Warm Springs, Georgia, where he founded a hydrotherapy center for the treatment of polio patients which still operates as the Roosevelt Warm Springs Institute for Rehabilitation (with an expanded mission), and spent a lot of time there in the 1920s. This was in part to escape from his mother, who tried to resume control of his life following his illness.

At a time when media intrusion in the private lives of public figures was much less intense than it is today, Roosevelt was able to convince many people that he was in fact getting better, which he believed was essential if he was to run for public office again. (The Encyclopædia Britannica, for example, says that "by careful exercises and treatments at Warm Springs he gradually recovered," although this is quite untrue.) Fitting his hips and legs with iron braces, he laboriously taught himself to walk a short distance by swiveling his torso while supporting himself with a walking stick. In private he used a wheelchair, but he was careful never to be seen in it in public, although he sometimes appeared on crutches. He usually appeared in public standing upright, while being supported on one side by an aide or one of his sons. He would certainly have hated the statue of himself in a wheelchair now to be seen at the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial in Washington, D.C..

Governor of New York

By 1928 Roosevelt believed he had recovered sufficiently to resume his political career. He had been careful to maintain his contacts in the Democratic Party. In 1924 he had attended the Democratic Convention and made a nomination speech for the Governor of New York, Alfred E. Smith. Although Smith was not nominated, in 1928 he ran again, and Roosevelt again supported him. This time he became the Democratic candidate, and he urged Roosevelt to run for Governor of New York. To gain the Democratic nomination, Roosevelt had to make his peace with Tammany Hall, which he did with some reluctance. At the November election, Smith was heavily defeated by the Republican Herbert Hoover, but Roosevelt was elected Governor by a margin of 25,000 votes out of 2.2 million. As a native of upstate New York he was able to appeal to voters outside New York City in a way other Democrats could not.

Roosevelt came to office in 1929 as a reform Democrat, but with no overall plan for his administration. He tackled official corruption by sacking Smith's cronies and instituting a Public Service Commission, and took action to address New York's growing need for electricity through the development of hydroelectricity on the St. Lawrence River. He reformed the state's prison administration and built a new state prison at Attica. He had a long feud with Robert Moses, the state's most powerful public servant, whom he sacked as Secretary of State but kept on as Parks Commissioner and head of urban planning. When the Wall Street Crash in October ushered in the Great Depression, Roosevelt showed his usual energy and imagination in responding. The Hoover administration took the traditional Republican view that the state should not interfere with the free operations of the economy, and that the states and cities should carry the burden of unemployment relief. Roosevelt therefore asked the state legislature for $20 million in relief funds, which he spent mainly on public works in the hope of stimulating demand and providing employment. Aid to the unemployed, he said, "must be extended by Government, not as a matter of charity, but as a matter of social duty."

Roosevelt knew little about economics, but he took advice from leading academics and social workers, and also from Eleanor, who had developed a network of friends in the welfare and labor fields and who took a close interest in social questions. On Eleanor's recommendation he appointed one of her friends, Frances Perkins, as Labor Secretary, and there was a sweeping reform of the labor laws. He established the first state relief agency under Harry Hopkins, who became a key advisor, and urged the legislature to pass an old age pension bill and an unemployment insurance bill.

The main weakness of the Roosevelt administration was the blatant corruption of the Tammany Hall machine in New York City, where the Mayor, Jimmy Walker, was the puppet of Tammany boss John F. Curry and where corruption of all kinds was rife. Roosevelt had made his name as an opponent of Tammany, but he needed the machine's goodwill to be re-elected in 1930 and for a possible future presidential bid. Roosevelt fell back on the rather feeble line that the Governor could not interfere in the government of New York City. But as the 1930 election approached Roosevelt acted by setting up a judicial investigation into the corrupt sale of offices. This eventually resulted in Walker resigning and fleeing to Europe to escape prosecution. But Tammany Hall's power was not seriously affected. In 1930 Roosevelt was elected to a second term by a margin of more than 700,000 votes.

First term: the New Deal

Roosevelt's immense popularity in the largest state in the country made him an obvious candidate for the Democratic nomination, which was hotly contested since it seemed clear that Hoover would be defeated at the 1932 presidential election. Al Smith also wanted the nomination, and Roosevelt was at first reluctant to oppose his old patron. But the party regulars were convinced that Smith, a Catholic who was closely associated with the illegal liquor industry, was unacceptable, and persuaded Roosevelt to declare his candidacy. At first the delegates at the Chicago convention were deadlocked, but eventually Smith's supporters from the north-eastern states were persuaded to support Roosevelt, and he was nominated on the fourth ballot. During the campaign Roosevelt said: "I pledge you, I pledge myself, to a new deal for the American people," coining a slogan that was later adopted for his legislative program.

In November Roosevelt and his Vice Presidential running mate, John N. Garner of Texas, won 57 percent of the vote and carried all but six states. In February 1933, while he was President-elect, Roosevelt had a brief holiday in Florida. In Miami an unemployed bricklayer named Giuseppe Zangara fired five shots at Roosevelt, missing him but killing the Mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak. Zangara, who was later executed, said he had shot at Roosevelt because "the capitalists killed my life."

When Roosevelt was inaugurated in March 1933 the United States was in the depths of the worst depression in its history. Some 13 million people, a third of the workforce, were unemployed. Industrial production had fallen by more than half since 1929. In a country with few government social services, millions were living on the edge of starvation, and two million were homeless. The banking system seemed to be on the point of collapse. There were occasional outbreaks of violence, but most observers considered it remarkable that such an obvious breakdown of the capitalist system had not led to a rapid growth of socialism, communism, or fascism (as happened for example in Germany). Instead of adopting revolutionary solutions, the American people had turned to the Democrats and to a leader who had grown up to privilege.

Roosevelt indeed had no systematic economic beliefs at all. He saw the Depression as mainly a matter of confidence—people had stopped spending, investing and employing labor because they were afraid to do so. As he put it in his inaugural address: "the only thing we have to fear is fear itself." He therefore set out to restore confidence through a series of dramatic gestures. He called a "bank holiday" to prevent a threatened run on the banks and called an emergency session of Congress to stabilize the financial system. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was created to guarantee the funds held in all banks in the Federal Reserve System, and thus prevent runs and bank failures. Roosevelt's series of radio speeches known as Fireside Chats presented his proposals to the American public.

During the first hundred days of his administration, Roosevelt used his enormous prestige and the sense of impending disaster to force a series of bills through Congress, establishing and funding various new government agencies. These included the Emergency Relief Administration, which granted funds to the states for unemployment relief; the Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps to hire millions of unemployed to work on local projects; and the Agricultural Adjustment Administration, with powers to increase farm prices and support struggling farmers. Following these emergency measures came the National Industrial Recovery Act which imposed an unprecedented amount of state regulation on industry, including fair practice codes and a guaranteed role for trade unions, in exchange for the repeal of anti-trust laws and huge amounts of financial assistance as a stimulus to the economy. Later came one of the largest pieces of state industrial enterprise in American history, the Tennessee Valley Authority, which built dams and power stations, controlled floods, and improved agriculture in one of the poorest parts of the country. The repeal of prohibition also provided stimulus to the economy, while eliminating a major source of corruption.

After the 1934 Congressional elections, which gave the Democrats large majorities in both houses, there was a fresh surge of New Deal legislation, driven by the "brains trust" of young economists and social planners gathered in the White House, including Raymond Moley, Rexford Tugwell and Adolf Berle of Columbia University, attorney Basil O'Connor, economist Bernard Baruch and Felix Frankfurter of Harvard Law School. Eleanor Roosevelt, Labor Secretary Frances Perkins (the first female Cabinet Secretary) and Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace were also important influences. These measures included bills to regulate the stock market and prevent the corrupt practices which had led to the 1929 Crash; the Social Security Act, which established Social Security and promised economic security for the elderly, the poor and the sick; and the National Labor Relations Act, which established the rights of workers to organize unions, to engage in collective bargaining and to take part in strikes in support of their demands.

The net effect of these measures was to restore confidence and optimism, allowing the country to begin the long process of recovery from the Depression. The popular belief is that Roosevelt's programs, collectively known as the New Deal, cured the Great Depression. Historians and economists debate over the extent to which this is true. The economic theories of John Maynard Keynes were not widely known in the United States, and it is doubtful that Roosevelt ever knew of them. Even the large appropriations that Roosevelt extracted from Congress and spent on relief and assistance to industry were not enough to provide a sufficient fiscal stimulus to revive so large an economy as that of the United States. The economy remained sluggish throughout the 1930s, and, in fact, after a partial recovery, slid back towards Depression in 1937 and 1938. Some argue that this was mainly because the high tariff barriers erected in response to the Depression were not removed, and without a revival of international trade there could be no full recovery. It took the massive growth in government spending during World War II to restore industrial production to its 1929 level and eliminate unemployment.

The second term

At the 1936 election Roosevelt won 61 percent of the vote and carried every state except Maine and Vermont. The New Deal Democrats won enough seats in Congress to outvote both the Republicans and the conservative Southern Democrats (who supported programs which brought benefits for their states but opposed measures which strengthened labor unions). Roosevelt was backed by a coalition of voters which included the urban workers and middle class, small farmers, the "Solid South," northern African-American voters (who had traditionally been Republicans), Jews and other urban ethnic minorities, intellectuals and political liberals. This coalition remained largely intact for the Democratic Party until the 1960s. The Roosevelt ascendancy also prevented the growth of both socialism and fascism. Although the Communist Party USA saw some growth during the 1930s, and gained some influence in industrial unions affiliated with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), it was unable to break into the political mainstream.

Roosevelt's second term agenda included an act creating the United States Housing Authority (1937), a second Agricultural Adjustment Act and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which created the minimum wage. When the economy began to deteriorate again in late 1937, Roosevelt responded with an aggressive program of stimulation, asking Congress for $5 billion for relief and public works programs.

With the Republicans powerless in Congress, the conservative majority on the United States Supreme Court was the only obstacle to Roosevelt's programs. During 1937 the Court ruled that the National Recovery Act and some other pieces of New Deal legislation were unconstitutional. Roosevelt's response was to propose enlarging the Court so that he could appoint more sympathetic judges. This "court packing" plan was the first Roosevelt scheme to run into serious political opposition, since it seemed to upset the separation of powers which is one of the cornerstones of the American constitutional structure. Eventually Roosevelt was forced to abandon the plan, but the Court also drew back from confrontation with the administration by finding the Labor Relations Act and the Social Security Act to be constitutional. Deaths and retirements on the Supreme Court soon allowed Roosevelt to make his own appointments to the bench. Between 1937 and 1941 he appointed eight justices to the court, including liberals such as Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black and William O. Douglas, reducing the possibility of further clashes.

Foreign policy 1933–41

The rejection of the League of Nations treaty in 1919 marked the dominance of isolationism in American foreign policy. Despite his Wilsonian background, Roosevelt and his Secretary of State, Cordell Hull, acted with great care not to provoke isolationist sentiment. The main foreign policy initiative of Roosevelt's first term was the Good Neighbor Policy, a re-evaluation of American policy towards Latin America, which ever since the Monroe Doctrine of 1823 had been seen as an American sphere of influence. American forces were withdrawn from Haiti, new treaties with Cuba and Panama ended their status as American protectorates. At the Seventh International Conference of American States in Montevideo in December 1933, Roosevelt and Hull signed the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States, renouncing the assumed American right to intervene unilaterally in the affairs of Latin American countries. Nevertheless, the realities of American support for various Latin American dictators, often in the service of American corporate interests, remained unchanged. It was Roosevelt who made the often-quoted remark about the dictator of Nicaragua, Anastasio Somoza: "Somoza may be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch."

The rise to power of Adolf Hitler in Germany aroused fears of a new world war. In 1935, at the time of Fascist Italy's invasion of Abyssinia, Congress passed the Neutrality Act, applying a mandatory ban on the shipment of arms from the United States to any combatant nation. Roosevelt opposed the act on the grounds that it penalized the victims of aggression such as Abyssinia, and that it restricted his right as President to assist friendly countries, but he eventually signed it. In 1937 Congress passed an even more stringent Act, but when the Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937 Roosevelt found various ways to assist China, and warned that Fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan were threats to world peace and to the United States. When World War II in Europe broke out in 1939, Roosevelt became increasingly eager to assist Britain and France, and he began a regular secret correspondence with Winston Churchill, in which the two freely discussed ways of circumventing the Neutrality Acts.

In May 1940 Germany attacked France and rapidly occupied the country, leaving Britain vulnerable to German air attack and possible invasion. Roosevelt was determined to prevent this and sought to shift public opinion in favor of aiding Britain. He secretly aided a private body, the Committee to Defend America by Aiding the Allies, and he appointed two anti-isolationist Republicans, Henry L. Stimson and Frank Knox, as Secretaries of War and the Navy respectively. The fall of Paris shocked American opinion, and isolationist sentiment declined. In August Roosevelt openly defied the Neutrality Acts with the Destroyers for Bases Agreement, which gave 50 American destroyers to Britain and Canada in exchange for base rights in the British Caribbean islands. This was a precursor of the March 1941 Lend-Lease agreement which began to direct massive military and economic aid to Britain.

The path to war

At the 1938 Congressional elections the Republicans staged their first comeback since 1932, gaining seats in both Houses and reducing Roosevelt's ability to pass legislation at will. Roosevelt's campaign to have conservative Democratic Senators such as Walter F. George of Georgia replaced by pro-Administration candidates was defeated. This increased speculation that Roosevelt would retire in 1940. No American President had ever sought a third term in office, following a precedent set by George Washington. During 1940, however, with the international situation growing increasingly threatening, Roosevelt decided that only he could lead the nation through the coming crisis. Republicans (and some others) said that this was a sign of his increasing arrogance. Nevertheless, Roosevelt's huge personal popularity allowed him to be re-elected with 55 percent of the vote and 38 of the 48 states. A shift to the left within the Administration was shown by the adoption of Henry Wallace as his Vice President in place of the conservative Southerner John N. Garner.

Roosevelt's third term was dominated by World War II, first in Europe and then in the Pacific. The massive re-armament program begun in 1938, partly to expand and re-equip the United States Army and Navy and partly to support Britain, France, China and other friendly states, finally provided the Keynesian economic stimulus which was needed to revive the economy. From 1939 unemployment fell rapidly, as the unemployed either joined the armed forces or found work in arms factories. By 1941 there was actually a labor shortage in the arms manufacturing centers of Chicago and Detroit, accelerating the Great Migration of African-American workers from the Southern states.

The most pressing issue was the urgent necessity of assisting Britain, whose financial resources were exhausted by the end of 1940. Congress, where isolationist sentiment was in retreat, passed the Lend-Lease Act in March 1941, allowing Britain to "lease" huge amounts of military equipment on the basis of a promise that they would be paid for after the war. Britain was also forced to agree to dismantle preferential trade arrangements that kept American exports out of the British Empire. This underlined the point that the war aims of the United States and Britain were not the same. Roosevelt was a lifelong free trader and anti-imperialist, and ending European colonialism was one of his objectives. This did not prevent the forming of a close personal relationship with Churchill, who became British Prime Minister in May 1940. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, Roosevelt extended Lend-Lease to the Soviets. During 1941 Roosevelt also agreed that the U.S. Navy would escort Allied convoys as far east as Iceland, and would fire on German ships or submarines if they attacked Allied shipping within the U.S. Navy zone. Thus by mid 1941 Roosevelt had committed the United States to the Allied side with a policy of "all aid short of war." Roosevelt met with Churchill on August 14, 1941 to develop the Atlantic Charter in what was to be the first of several strategic war conferences.

Pearl Harbor

Roosevelt was much less keen to involve the United States in the war developing in East Asia, where Japan occupied French Indo-China in late 1940. He authorized increased aid to China, and in July 1941 he restricted the sales of oil and other strategic materials to Japan, but also continued negotiations with the Japanese government in the hope of averting war. Through 1941 the Japanese planned their attack on the western powers, including the United States, while spinning out the negotiations in Washington. The "hawks" in the Administration, led by Stimson and Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau, were in favor of a tough policy towards Japan, but Roosevelt, emotionally committed to the war in Europe, refused to believe that Japan might attack the U.S. and favored continued negotiations. The U.S. Ambassador in Tokyo, Joseph C. Grew, passed on warnings about the planned attack on the American Pacific Fleet's base at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, but these were ignored by the State Department.

On 7 December 1941 the Japanese attacked the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor, destroying most of it and killing 3,000 American personnel. The American commanders at Pearl Harbor, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel and General Walter Short, were taken completely by surprise, and were later made scapegoats for this disaster. The fault really lay with the War Department in Washington, who since August 1940 had been able to read the Japanese diplomatic codes and had thus been given ample warning of the imminence of the attack (though not of its actual date). The War Department had not passed these warnings on to the commanders in Hawaii, mainly because its analysts refused to believe that the Japanese would really have the effrontery to attack the United States.

It has become a staple of postwar revisionist history that Roosevelt knew all about the planned attack on Pearl Harbor but did nothing to prevent it so that the U.S. could be brought into the war as a result of being attacked. There is no evidence to support this theory. On 5 December the Cabinet discussed the mounting intelligence evidence that the Japanese were mobilizing for war. Navy Secretary Knox told the Cabinet of the decoded messages showing that the Japanese fleet was at sea, but stated his opinion that it was heading south to attack the British in Malaya and Singapore, and to seize the oil resources of the Dutch East Indies. Roosevelt and the rest of the Cabinet accepted this view. There were intercepted Japanese messages suggesting an attack on Pearl Harbor, but delays in translating and passing on these messages through the inefficient War Department bureaucracy meant that they did not reach the Cabinet before the attack took place. There is no evidence that Roosevelt was made aware of them. All contemporary accounts describe Roosevelt, Hull and Stimson as shocked and outraged when they heard news of the attack.

The Japanese took advantage of their pre-emptive destruction of most of the Pacific Fleet to rapidly occupy the Philippines and all the British and Dutch colonies in South-East Asia, taking Singapore in February 1942 and advancing through Burma to the borders of British India by May, thus cutting off the overland supply route to China. Pearl Harbor was followed immediately by declarations of war on the United States by Germany and Italy. Isolationism evaporated overnight and the country united behind Roosevelt as a wartime leader. Despite the wave of anger that swept across the United States in the wake of Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt decided from the start that the defeat of Nazi Germany had to take priority. He met with Churchill in late December and planned a broad alliance between the U.S., Britain and the Soviet Union, with the objectives of, first, halting the German advances in the Soviet Union and in North Africa, second, launching an invasion of western Europe with the aim of crushing Nazi Germany between two fronts, and only third turning to the task of defeating Japan.

Although Roosevelt was constitutionally the Commander-in-Chief of the United States armed forces, he had never worn a uniform and he did not interfere in operational military matters in anything like the way Churchill did in Britain, let alone take direct command of the forces as Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin did. He placed great trust in the Army Chief of Staff, General George Marshall, and later in his Supreme Commander in Europe, General Dwight Eisenhower, and left almost all strategic and tactical decisions to them, within the broad framework for the conduct of the war decided by the Cabinet in agreement with the other Allied powers. He had less confidence in his commander in the Pacific, General Douglas MacArthur, who he rightly suspected of planning to run for President against him. But since the war in the Pacific was mainly a naval war, this did not greatly matter until later in the war. Given his close personal interest in the Navy, Roosevelt tended to intervene more in naval matters, but strong Navy commanders like Admirals Ernest King in the Atlantic theater and Chester Nimitz in the Pacific enjoyed his confidence.

The Japanese-American issue

Following the outbreak of the Pacific War Roosevelt came under immediate pressure to remove or intern the estimated 120,000 people of Japanese origin or descent living in California, many of them American-born, in the grounds that they were a threat to security. Pressure came from California Governor Culbert Olsen (a Democrat), the Hearst newspapers and General John L. De Witt, the U.S. Army Commander in California, whose simple attitude was that "a Jap is a Jap." Opponents of the suggestion were Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes, Attorney-General Francis Biddle and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who said that there was no evidence of Japanese-American involvement in espionage or sabotage.

On February 7 1942 Biddle met with Roosevelt and set out the Justice Department's objections to the proposal. Roosevelt then ordered that a plan be drawn up to evacuate the Japanese-Americans from California in the event of a Japanese landing or air attacks on the west coast, but not otherwise. But on February 11 he met with Secretary of War Stimson, who persuaded him to approve an immediate evacuation. No evidence was ever produced to support fears of Japanese-American espionage, though De Witt stated that, "The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken."

On February 19, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, authorizing the military to relocate people from "combat zones" (such as California) on security grounds, without specifically mentioning the Japanese-Americans. As a result, 120,000 people, half of them American citizens, were interned without charge or trial. Roosevelt also wanted the 140,000 Japanese-Americans in Hawaii deported to the mainland, but the territory authorities, including the Army, objected on the grounds that they were indispensable to the Islands' economy, and the plan was dropped. By contrast, there was no mass internment of German-Americans or Italian-Americans, though 11,000 German aliens and German American citizens were placed in internment camps up to 1950. Also, up to 900,000 German and Italian-Americans were forced to carry identification papers, had their movement restricted and had their personal property seized. Roosevelt also forced several Latin American countries to send their German aliens to Internment camps in the United States. Japanese-Americans continued to serve in the U.S. armed forces throughout the war, although they were not employed in the Pacific theater. (The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was composed almost entirely of formerly interned Japanese-Americans and remains the most highly decorated unit in U.S. military history.) Conditions in the camps, in Idaho, Wyoming, Utah and Colorado, were tolerable, but those interned naturally resented this treatment and there were repeated disturbances in the camps, which resulted in 15,000 people being interned in a higher-security center at Tule Lake, California. In 1944 the Supreme Court upheld the legality of the executive order, which remained in force until December 1944.

Ickes lobbied Roosevelt through 1944 to release the internees, but Roosevelt did not act until after the November presidential election. A fight for Japanese-American civil rights would have meant a fight with influential Democrats, the Army, and the Hearst press and would have endangered Roosevelt's chances of winning California in 1944. Roosevelt's action were also possibly motivated by racism. In 1925 he had written about Japanese immigration: "Californians have properly objected on the sound basic grounds that Japanese immigrants are not capable of assimilation into the American population... Anyone who has traveled in the Far East knows that the mingling of Asiatic blood with European and American blood produces, in nine cases out of ten, the most unfortunate results." Upon activating the 442nd RCT, though, on February 1, 1943, Roosevelt stated, ""No loyal citizen of the United States should be denied the democratic right to exercise the responsibilities of his citizenship, regardless of his ancestry. The principle on which this country was founded and by which it has always been governed is that Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was, a matter of race or ancestry."

Civil rights and refugees

Roosevelt's attitudes to race were also tested by the issue of African-American (or "Negro," to use the term of the time) service in the armed forces. The Democratic Party at this time was dominated by Southerners who were opposed to any concession to demands for racial equality. During the New Deal years, there had been a series of conflicts over whether African-Americans were eligible for the various government benefits and programs. Typically, the young idealists who ran the programs tried to make these benefits available regardless of race. Southern Governors or Congressmen would then complain to Roosevelt, who would intervene to uphold segregation. The Works Progress Administration and the Civilian Conservation Corps, for example, segregated their work forces by race at Roosevelt's insistence after Southern Governors protested at unemployed whites being required to work alongside blacks. Roosevelt's personal racial attitudes were conventional for his time and class. He was not an visceral racist like most white Southerners, but he accepted the common stereotype of African-Americans as lazy, if good-natured, children. He did little to advance civil rights, despite prodding from Eleanor and liberals in his Cabinet such as Frances Perkins.

The war brought the issue to the forefront. The armed forces had been segregated ever since the Civil War. African-Americans in the Army served only in rear-echelon or service roles, the Navy was almost entirely white and the Marine Corps wholly so. Neither the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, not the Navy Secretary, Frank Knox, were Southerners (Stimson came from a New York abolitionist family), but they were aware that the officer corps of both services were drawn heavily from Southern military families, and feared disturbances or even mutiny if segregation of the armed forces were imposed. "Colored troops do very well under white officers," said Stimson, "but every time we try to lift them a little beyond where they can go, disaster and confusion follow." Knox was blunter: "In our history we don't take Negroes into a ship's company."

But by 1940 the African-American vote had shifted almost totally from Republican to Democrat, and African-American leaders like Walter White of the NAACP and T. Arnold Hill of the Urban League had become recognized as part of the Roosevelt coalition. In June 1941, the urging of A. Philip Randolph, the leading African-American trade unionist, Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing the Fair Employment Practice Commission and prohibiting discrimination by any government agency, including the armed forces. In practice the services, particularly the Navy and the Marines, found ways to evade this order—the Marine Corps remained all-white until 1943. In September 1942, at Eleanor's instigation, Roosevelt met with a delegation of African-American leaders, who demanded full integration in the forces, including the right to serve in combat roles and in the Navy, the Marine Corps and the United States Army Air Force. Roosevelt, with his usual desire to please everyone, agreed, but then did nothing to implement his promise. It was left to his successor, Harry S. Truman, to fully desegregate the armed forces.

Roosevelt's attitudes to American Jews were even more complex. Sara Roosevelt was a virulent anti-Semite, an attitude common among upper-class Americans at a time when Jewish immigrants were flooding into the United States and their children were advancing rapidly into the business and professional classes. Roosevelt inherited his mother's attitudes, and freely expressed them in private throughout his life. In a common paradox of the time, some of his closest political associates, such Felix Frankfurter, Bernard Baruch and Samuel I. Rosenman, were Jewish, and he happily cultivated the important Jewish vote in New York City. He appointed Henry Morgenthau, Jr. as the first Jewish Secretary of the Treasury and appointed Frankfurter to the Supreme Court. But he once told Morgenthau and a Catholic economist, Leo T. Crowley: "This is a Protestant country, and the Catholics and the Jews are here on sufferance."

Roosevelt's anti-Semitism became an important factor in deciding government policy on the Jewish refugee issue before and during World War II. During his first term Roosevelt condemned Hitler's persecution of German Jews, but said "this is not a governmental affair" and refused to make any public comment. As the Jewish exodus from Germany increased after 1937, Roosevelt was asked by American Jewish organizations and Congressmen to allow these refugees to settle in the U.S. At first he suggested that the Jewish refugees should be "resettled" elsewhere, and suggested Venezuela, Ethiopia or West Africa—anywhere but the United States. In 1939 he suggested a refugee quota of 27,000 German and Austrian Jews per year, at a time when up to 5 million Jews were trying to escape from Europe. Morgenthau, Harold Ickes and Eleanor pressed him to adopt a more generous policy but he was afraid of provoking the isolationists—men such as Charles Lindbergh who exploited anti-Semitism as a means of attacking Roosevelt's policies. In practice very few Jewish refugees came to the United States—only 22,000 German refugees were admitted in 1940, not all of them Jewish. The State Department official in charge of refugee issues, Breckinridge Long, was a visceral anti-Semite who did everything he could to obstruct Jewish immigration. Despite frequent complaints, Roosevelt refused to shift him.

Even after 1942, when Roosevelt was made aware, by Rabbi Stephen Wise, the Polish envoy Jan Karski and others, of the Nazi extermination of the Jews, and when isolationism was no longer a factor in American politics, he refused to allow any systematic attempt to rescue European Jewish refugees and bring them to the United States. In May 1943 he wrote to Cordell Hull (whose wife was Jewish): "I do not think we can do other than strictly comply with the present immigration laws." In January 1944, however, Morgenthau succeeded in persuading Roosevelt to allow the creation of a War Refugee Board in the Treasury Department. This allowed an increasing number of Jews to enter the U.S. in 1944 and 1945. By this time, however, it was too late to save anything but a fragment of the European Jewish communities which had been destroyed by Hitler's Holocaust. In any case after 1945 the focus of Jewish aspirations shifted from migration to the United States to settlement in Palestine, where the Zionist movement hoped to create a Jewish state. But Roosevelt was also opposed to this idea. When he met King Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia in January 1945, he assured him he did not support a Jewish state in Palestine. He suggested that since the Nazis had killed three million Polish Jews, there should now be plenty of room in Poland to resettle all the Jewish refugees. Roosevelt's attitudes to both African-Americans and Jews remain a striking contrast with his social liberalism and generosity of spirit on most other issues.

Strategy and diplomacy

As Churchill rightly saw, the entry of the United States into the war meant that victory of the Allied powers was assured. Even though Britain was exhausted by the end of 1942, the alliance between the manpower of the Soviet Union and the industrial resources of the United States was bound to defeat Germany and Japan in the long run. But mobilizing those resources and deploying them effectively was a difficult task. The United States took the straightforward view that the quickest way to defeat Germany was to transport its army to Britain, invade France across the English Channel and attack Germany directly from the west. Churchill, wary of the huge casualties he feared this would entail, favored a more indirect approach, advancing northwards from the Mediterranean, where the Allies were fully in control by early 1943, into either Italy or Greece, and thus into central Europe. Churchill also saw this as a way of blocking the Soviet Union's advance into east and central Europe, a political issue which Roosevelt and his commanders refused to take into account.

Since the U.S. would be providing most of the manpower and funds, Roosevelt's views prevailed, and through 1942 and 1943 plans for a cross-Channel invasion were advanced. But Churchill succeeded in persuading Roosevelt to undertake the invasions of French Morocco and Algeria (Operation Torch) in November 1942, of Sicily (Operation Husky) in July 1943, and of Italy (Operation Avalanche) in September 1943). This entailed postponing the cross-Channel invasion from 1943 to 1944. Following the American defeat at Anzio, however, the invasion of Italy became bogged down, and failed to meet Churchill's expectations. This undermined his opposition to the cross-Channel invasion (Operation Overlord), which finally took place in June 1944. Although most of France was quickly liberated, the Allies were blocked on the German border in December 1944, and final victory over Germany was not achieved until May 1945, by which time the Soviet Union, as Churchill feared, had occupied all of eastern and central Europe as far west as the Elbe River in central Germany.

Meanwhile in the Pacific the Japanese advance reached its maximum extent by June 1942, when Japan sustained a major naval defeat at the hands of the U.S. at the Battle of Midway. The Japanese advance to the south and south-east was halted at the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942 and the Battle of Guadalcanal between August 1942 and February 1943. MacArthur and Nimitz then began a slow and costly progress through the Pacific islands, with the objective of gaining bases from which strategic air power could be brought to bear on Japan and from which Japan could ultimately be invaded. In the event this did not prove necessary, because the almost simultaneous declaration of war on Japan by the Soviet Union and the use of the atomic bomb on Japanese cities brought about Japan's surrender in September 1945.

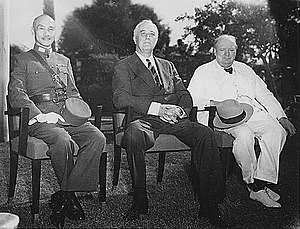

By late 1943 it was apparent that the Allies would ultimately defeat Nazi Germany, and it became increasingly important to make high-level political decisions about the course of the war and the postwar future of Europe. Roosevelt met with Churchill and the Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek at the Cairo Conference in November 1943, and then went to Tehran to confer with Churchill and Stalin. At the Tehran Conference Roosevelt and Churchill told Stalin about the plan to invade France in 1944, and Roosevelt also discussed his plans for a postwar international organization. Stalin was pleased that the western Allies had abandoned any idea of moving into the Balkans or central Europe via Italy, and he went along with Roosevelt's plan for the United Nations, which involved no costs to him. Stalin also agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan when Germany was defeated. At this time Churchill and Roosevelt were acutely aware of the huge and disproportionate sacrifices the Soviets were making on the eastern front while their invasion of France was still six months away, so they did not raise awkward political issues which did not require immediate solutions, such as the future of Germany and eastern Europe.

By the beginning of 1945, however, with the Allied armies advancing into Germany, consideration of these issues could not be put off any longer. In February Roosevelt, despite his steadily deteriorating health, traveled to Yalta, in the Soviet Crimea, to meet again with Stalin and Churchill. This meeting, the Yalta Conference, is often portrayed as a decisive turning point in modern history, but in fact most of the decisions made there were retrospective recognitions of realities which had already been established by force of arms. The decision of the western Allies to delay the invasion of France from 1943 to 1944 had allowed the Soviet Union to occupy all of eastern Europe, including Poland, Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary, as well as eastern Germany. Since Stalin was in full control of these areas, there was little Roosevelt and Churchill could do to deter him imposing his will on them, as he was rapidly doing by establishing Communist-controlled governments in all these countries.

Churchill, aware that Britain had gone to war in 1939 in defense of Polish independence, and also of his promises to the Polish government in exile in London, did his best to insist that Stalin agree to the establishment of a non-Communist government and the holding of free elections in liberated Poland, although he was unwilling to confront Stalin over the issue of Poland's postwar frontiers, on which he considered the Polish position to be indefensible. But Roosevelt was not interested in having a fight with Stalin over Poland, for two reasons. The first was that he believed that Soviet support was essential for the projected invasion of Japan, in which the allies ran the risk of huge casualties. He feared that if Stalin was provoked over Poland he might renege on his Tehran commitment to enter the war against Japan. The second was that he saw the United Nations as the ultimate solution to all postwar problems, and he feared the United Nations project would fail without Soviet cooperation.

Towards posterity

Although Roosevelt was only 62 in 1945, his health had been in decline since at least 1940. The strain of his paralysis and the physical exertion needed to compensate for it for over 20 years had taken their toll, as had many years of stress and a lifetime of chain-smoking. He had been diagnosed with high blood pressure and advised to modify his diet (though not to stop smoking). Had it not been for the war, he would certainly have retired at the 1944 elections, but under the circumstances both he and his advisors felt there was no alternative to his running for a fourth term. Aware of the risk that Roosevelt would die during his fourth term, the party regulars insisted that Henry Wallace, who was seen as too pro-Soviet, be dropped as Vice President. Roosevelt at first resisted but finally agreed to replace Wallace with the little known Harry S. Truman. In the November elections Roosevelt and Truman won 53 percent of the vote and carried 36 states. After the elections Cordell Hull, the longest serving Secretary of State in American history, retired and was succeeded by Edward Stettinius Jr..

After the Yalta conference relations between the western Allies and Stalin deteriorated rapidly, and so did Roosevelt's health. When he addressed Congress on his return from Yalta, many were shocked to see how old, thin and sick he looked. He spoke from his wheelchair, an unprecedented concession to his physical incapacity. But he was still mentally fully in command. "The Crimean Conference," he said firmly, "ought to spend the end of a system of unilateral action, the exclusive alliances, the spheres of influence, the balances of power, and all the other expedients that have been tried for centuries—and have always failed. We propose to substitute for all these, a universal organization in which all peace-loving nations will finally have a chance to join." Many in his audience doubted that the proposed United Nations would achieve these objectives, but there was no doubting the depth of Roosevelt's commitment to these ideals, which he had inherited from Woodrow Wilson.

Roosevelt is often accused of being naively trusting of Stalin, but in the last months of the war he took an increasingly tough line. During March and early April he sent strongly worded messages to Stalin accusing him of breaking his Yalta commitments over Poland, Germany, prisoners of war and other issues. When Stalin accused the western Allies of plotting a separate peace with Hitler behind his back, Roosevelt replied: "I cannot avoid a feeling of bitter resentment towards your informers, whoever they are, for such vile misrepresentations of my actions or those of my trusted subordinates."

On March 30 Roosevelt went to Warm Springs to rest before his anticipated appearance at the April 25 San Francisco founding conference of the United Nations. Among the guests was Lucy Mercer, his lover from 30 years previously (by then Mrs Lucy Rutherford), and the artist Elizabeth Shoumatoff, who was painting a portrait of him. On the morning of April 12 he was sitting in a leather chair signing letters, his legs propped up on a stool, while Shoumatoff worked at her easel. Just before lunch was to be served, he dropped his pen and complained of a sudden headache. Then he slumped forward in his chair and lost consciousness. A doctor was summoned and he was carried to bed—it was immediately obvious that he had suffered a massive cerebral hemorrhage. At 3.31pm he was pronounced dead.

Roosevelt's death was greeted with shock and grief across the United States and around the world. At a time when the press did not pry into the health or private lives of Presidents, his declining health had not been known to the general public. Roosevelt had been President for more than 12 years, much longer than any other man, and had led the country through some of its greatest crises to the brink of its greatest triumph, the complete defeat of Nazi Germany, and to within sight of the defeat of Japan as well. Although in the decades since his death there have been many critical reassessments of his career, few commentators had anything but praise for a commander in chief who had been robbed by death of a victory which was only a few weeks away.

Roosevelt's legacies to the United States were a greatly expanded role for government in the management of the economy, an expectation that the state would intervene to protect the poor and the disadvantaged from adversity, a Social Security system promising protection from cradle to grave, a greatly strengthened trade union movement, and a coalition of voters supporting the Democratic Party which would survive intact until the 1960s and in part until the 1980s, when it was finally shattered by Ronald Reagan, a Roosevelt Democrat in his youth who became a conservative Republican. Internationally, Roosevelt's monument was the United Nations, an organization whose history would certainly have disappointed him in many respects, but which offered at least the hope of an end to the international anarchy which led to two world wars in his lifetime.

Majority support for the essentials of the Roosevelt domestic program survived their author by 35 years. The Republican administrations of Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon did nothing to overturn the Roosevelt-era social programs. It was not until the administration of Ronald Reagan (1981–89) that ideological conservatives in the Republican Party were able to undermine the Roosevelt legacy—although Reagan was generous in his praise of Roosevelt personally. Bill Clinton, with his program of welfare reform, was the first Democratic president to repudiate elements of the Roosevelt program, and this has continued under George W. Bush. But this has not undermined Roosevelt's posthumous reputation as a great president. A 1999 survey of academic historians by CSPAN found that historians consider Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, and Roosevelt the three greatest presidents by a wide margin.. A 2000 survey by The Washington Post found Washington, Lincoln, and Roosevelt to be the only "great" Presidents.

Cabinet members

| OFFICE | NAME | TERM |

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt | 1933–1945 |

| Vice President | John Nance Garner | 1933–1941 |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1941–1945 | |

| Harry S. Truman | 1945 | |

| State | Cordell Hull | 1933–1944 |

| Edward R. Stettinius, Jr. | 1944–1945 | |

| War | George H. Dern | 1933–1936 |

| Harry H. Woodring | 1936–1940 | |

| Henry L. Stimson | 1940–1945 | |

| Treasury | William H. Woodin | 1933–1934 |

| Henry Morgenthau, Jr. | 1934–1945 | |

| Justice | Homer S. Cummings | 1933–1939 |

| William F. Murphy | 1939–1940 | |

| Robert H. Jackson | 1940–1941 | |

| Francis B. Biddle | 1941–1945 | |

| Post | James A. Farley | 1933–1940 |

| Frank C. Walker | 1940–1945 | |

| Navy | Claude A. Swanson | 1933–1939 |

| Charles Edison | 1940 | |

| Frank Knox | 1940–1944 | |

| James V. Forrestal | 1944–1945 | |

| Interior | Harold L. Ickes | 1933–1945 |

| Agriculture | Henry A. Wallace | 1933–1940 |

| Claude R. Wickard | 1940–1945 | |

| Commerce | Daniel C. Roper | 1933–1938 |

| Harry L. Hopkins | 1939–1940 | |

| Jesse H. Jones | 1940–1945 | |

| Henry A. Wallace | 1945 | |

| Labor | Frances C. Perkins | 1933–1945 |

Supreme Court appointments

- Hugo Black (AL) August 19, 1937–September 17, 1971

- Stanley Forman Reed (KY) January 31, 1938–February 25, 1957

- Felix Frankfurter (MA) January 30, 1939–August 28, 1962

- William O. Douglas (CT) April 17, 1939–November 12, 1975

- Frank Murphy (MI) February 5, 1940–July 19, 1949

- Harlan Fiske Stone (Chief Justice, NY) July 3, 1941–April 22, 1946

- James Francis Byrnes (SC) July 8, 1941–October 3, 1942

- Robert H. Jackson (NY) July 11, 1941–October 9, 1954

- Wiley Blount Rutledge (IA) February 15, 1943–September 10, 1949

President Roosevelt appointed nine Justices to the Supreme Court of the United States, which, depending on your point of view, either puts him in a tie with George Washington, or one behind him. Washington appointed ten Justices, but appointed John Rutledge twice, and Rutledge's nomination was rejected by the Senate the second time. Rutledge had been serving on the court in the meantime, however. Between the appointment of Justice Wiley Blount Rutledge in 1943 and Roosevelt's death in 1945, eight of the nine Supreme Court Justices were Roosevelt appointees, the only holdout being Hoover appointee Owen Josephus Roberts, who was replaced by President Truman in 1948. Thus, Roosevelt almost became the second president to appoint the entire Supreme Court.

Media

Template:Multi-video start Template:Multi-video item Template:Multi-video end

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

Template:Multi-listen start Template:Multi-listen item Template:Multi-listen end

References

- Ted Morgan, FDR: A biography, Simon & Schuster, New York 1985

- William E. Leuchtenberg, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal, Harper & Row, New York 1963

- Franklin Delano Roosevelt Cabinet Members

See also

- U.S. presidential election, 1920

- U.S. presidential election, 1932

- U.S. presidential election, 1936

- U.S. presidential election, 1940

- U.S. presidential election, 1944

- History of the United States (1918-1945)

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (Hyde Park, New York)

- Business Plot

- Critics of the New Deal

- Franklin Roosevelt's Second Bill of Rights

- Fala

External links

- First Inaugural Address

- Second Inaugural Address

- Third Inaugural Address

- Fourth Inaugural Address

- Audio clips of FDR's speeches

- Court "Packing" Speech March 9, 1937

- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

- IPL POTUS — Franklin Delano Roosevelt

- Encyclopedia Americana: Franklin D. Roosevelt

- An archive of political cartoons from the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt

- Warm Springs and FDR's Polio Treatment

- FDR's Folly: How Roosevelt and His New Deal Prolonged the Great Depression ISBN 0-761-50165-7

- Dutch Martin's review of FDR's folly

- FDR at the Atlantic Conference

| Preceded byThomas R. Marshall | Democratic Party Vice Presidential candidate 1920 (lost) |

Succeeded byCharles W. Bryan |

| Preceded byAlfred E. Smith | Governor of New York 1929–1933 |

Succeeded byHerbert H. Lehman |

| Preceded byAl Smith | Democratic Party Presidential candidate 1932 (won), 1936 (won), 1940 (won), 1944 (won) |

Succeeded byHarry S. Truman |

| Preceded byHerbert Hoover | President of the United States March 4, 1933–April 12, 1945 |

Succeeded byHarry S. Truman |