This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Skomorokh (talk | contribs) at 12:42, 25 November 2007 (→Cultural impact: +image). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 12:42, 25 November 2007 by Skomorokh (talk | contribs) (→Cultural impact: +image)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) This article is about the philosophy of Ayn Rand. For other uses of Objectivism, see Objectivism.| Ayn Rand | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bibliography |

| ||||||||||||||

| Adaptations |

| ||||||||||||||

| Philosophy | |||||||||||||||

| Influence | |||||||||||||||

| Depictions | |||||||||||||||

Objectivism is a philosophy developed by Ayn Rand in the 20th century that encompasses positions on metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, politics, and aesthetics.

Objectivism holds that there is mind-independent reality; that individual persons are in contact with this reality through sensory perception; that human beings gain objective knowledge from perception by measurement and form valid concepts by measurement omission; that the proper moral purpose of one's life is the pursuit of one's own happiness or "rational self-interest"; that the only social system consistent with this morality is full respect for individual rights, embodied in pure, consensual laissez-faire capitalism; and that the role of art in human life is to transform abstract knowledge, by selective reproduction of reality, into a physical form—a work of art—that one can comprehend and respond to with the whole of one's consciousness.

Summary

Ayn Rand characterized Objectivism as a philosophy "for living on earth" grounded in reality and aimed at achieving knowledge about the natural world and harmonious, mutually beneficial interactions between human beings. Rand wrote:

My philosophy, in essence, is the concept of man as a heroic being, with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life, with productive achievement as his noblest activity, and reason as his only absolute.

Rand presented her philosophy through her novels The Fountainhead, Atlas Shrugged, and other works. She elaborated on her ideas in The Objectivist Newsletter,The Ayn Rand Letter, Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology, and other non-fiction books. As well, she edited the journal The Objectivist in which her work was published along with that of other authors who largely agreed with Objectivism, such as Alan Greenspan.

Origins of the name

Objectivism derives its name from its conception of knowledge and values as "objective," neither "intrinsic" nor "subjective." According to Rand, concepts and values are not intrinsic to external reality, nor are they merely subjective (by which Rand means "arbitrary" or "created by feelings, desires, 'intuitions,' or whims"; like wishful thinking). Rather, valid concepts and values are, as she wrote, "determined by the nature of reality, but to be discovered by man's mind."

Rand chose Objectivism as the name of her philosophy because her ideal term to label a philosophy based on the primacy of existence, Existentialism, had already been adopted to describe the philosophy of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

Objectivist principles

Metaphysics: Objective reality

Main article: Objectivist metaphysicsAyn Rand's philosophy is based on three axioms: the axiom of Existence, the law of Identity, and the axiom of Consciousness. Rand defined an axiom as "a statement that identifies the base of knowledge and of any further statement pertaining to that knowledge, a statement necessarily contained in all others whether any particular speaker chooses to identify it or not. An axiom is a proposition that defeats its opponents by the fact that they have to accept it and use it in the process of any attempt to deny it." As Leonard Peikoff noted, Rand's argumentation "is not a proof that the axioms of existence, consciousness, and identity are true. It is proof that they are axioms, that they are at the base of knowledge and thus inescapable."

Objectivism states that "Existence exists" (the "axiom of Existence") and "Existence is Identity." To be is to be "an entity of a specific nature made of specific attributes." That which has no attributes does not and cannot exist. Hence, "A is A" ("Law of Identity:") a thing is what it is. Whereas "existence exists" pertains to existence itself (whether something exists or not), the law of identity pertains to the nature of an object as being necessarily distinct from other objects (whether something exists as this or that). As Rand wrote, "A leaf cannot be all red and green at the same time, it cannot freeze and burn at the same time. A is A."

Rand held that when one is able to perceive something that exists, then one's "Consciousness exists" (the "axiom of Consciousness,") consciousness "being the faculty of perceiving that which exists." Objectivism maintains that what exists does not exist because one thinks it exists; it simply exists, regardless of anyone's awareness, knowledge or opinion. For Rand, "to be conscious is to be conscious of something," so that an objective reality independent of consciousness has to exist first for consciousness to become possible, and there is no possibility of a consciousness that is conscious of nothing outside itself. Thus consciousness cannot be the only thing that exists. "It cannot be aware only of itself — there is not 'itself' until it is aware of something." Objectivism holds that the mind cannot create reality, but rather, it is a means of discovering reality.

Objectivist philosophy regards the "Law of Causality," which states that things act in accordance with their natures, as "the law of identity applied to action." Rand rejected the popular notions that everything has a cause (asserting that existence itself does not) or that the causal link relates action to action. According to Rand, an "action" is not an entity, rather, it is entities that act, and every action is the action of an entity. The way entities interact is caused by the specific nature (or "identity") of those entities; if they were different there would be a different result.

Epistemology: Reason

Main article: Objectivist epistemologyThe starting point of Objectivist Epistemology is the principle, presented by Rand as a direct consequence of the metaphysical axiom that "Existence is Identity," that Knowledge is Identification. Objectivist epistemology studies how one can translate perception, i.e., awareness acquired through the senses, into valid concepts that actually identify the facts of reality.

Objectivism states that by the method of reason man can gain knowledge (identification of the facts of reality) and rejects philosophical skepticism. Objectivism also rejects faith and "feeling" as means of attaining knowledge. Although Rand acknowledged the importance of emotion in humans, she maintained that the existence of emotion was part of our reality, not a separate means of achieving awareness of reality.

Rand was neither a classical empiricist (like Hume or the logical positivists) nor a classical rationalist (like Plato, Descartes, or Frege). She disagreed with the empiricists mainly in that she considered perception to be simply sensation extended over time, limiting the scope of perception to automatic, pre-cognitive awareness. Thus, she categorized so-called "perceptual illusions" as errors in cognitive interpretation due to complexity of perceptual data. She held that objective identification of the values of attributes of existents is obtained by measurement, broadly defined as procedures whose perceptual component, the comparison of the attribute's value to a standard, is so simple that an error in the resulting identification is not possible given a focused mind. Therefore, according to Rand, knowledge obtained by measurement (the fact that an entity has the measured attribute, and the value of this attribute relative to the standard) is "contextually certain."

Ayn Rand's most distinctive contribution in epistemology is her theory that concepts are properly formed by measurement omission. Objectivism distinguishes valid concepts from poorly formed concepts, which Rand calls "anti-concepts." While we can know that something exists by perception, we can only identify what exists by measurement, and by logic (defined by Rand as "the art of non-contradictory identification,") which are necessary to turn percepts into valid concepts. Rand's procedural logic specifies that a valid concept is formed by omitting the variable measurements of the values of corresponding attributes of a set of instances or units, but keeping the list of shared attributes - a template with measurements omitted - as the criterion of membership in the conceptual class. When the fact that a unit has all the attributes on this list has been verified by measurement, then that unit is known with contextual certainty to be a unit of the given concept.

Because a concept is only known to be valid within the range of the measurements by which it was validated, it is an error to assume that a concept is valid outside this range, which is its (contextual) scope. It is also an error to assume that a proposition is known to be valid outside the scope of its concepts, or that the conclusion of a syllogism is known to be valid outside the scope of its premises. Rand ascribed scope violation errors in logic to epistemological intrinsicism.

Rand did not consider the analytic-synthetic distinction, including the view that there are "truths in virtue of meaning," or that "necessary truths" and mathematical truths are best understood as "truths in virtue of meaning," to have merit. She similarly denied the existence of a priori knowledge. Rand also considered her ideas distinct from foundationalism, naive realism about perception like Aristotle, or representationalism (i.e., an indirect realist who believes in a "veil of ideas") like Descartes or Locke.

Objectivist epistemology, like most other philosophical branches of Objectivism, was first presented by Rand in Atlas Shrugged. It is more fully developed in Rand's 1967 Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology. Rand considered her epistemology and its basis in reason so central to her philosophy that she remarked, "I am not primarily an advocate of capitalism, but of egoism; and I am not primarily an advocate of egoism, but of reason. If one recognizes the supremacy of reason and applies it consistently, all the rest follows."

Ethics: Rational self-interest

Main article: Objectivist ethicsUnlike many other philosophers, Ayn Rand limited the scope of ethics to the derivation of principles needed in all contexts, whether one is alone or with others. Her philosophical principles for dealing rationally with others are derived in Objectivist politics.

In her one-sentence summary of Objectivism (see Summary and Sources, above) Ayn Rand condensed her ethics into the statement that man properly lives "with his own happiness as the moral purpose of his life." According to Objectivist epistemology, however, states of mind, such as happiness, are not primary; they are the consequence of specific facts of existence. Therefore man needs an objective standard, grounded in the facts of reality, to achieve happiness. The human faculty of happiness is a biologically evolved measuring instrument (a "barometer") that measures how well one is doing in the pursuit of life. Therefore the standard by which one can judge whether or not some action will lead to greater or lesser happiness is, whether or not it promotes one's life. But, as Rand writes,

"To live, man must hold three things as the supreme and ruling values of his life: Reason, Purpose, Self-Esteem."

The ethics of Objectivism is based on the observation that one's own choices and actions are instrumental in maintaining and enhancing one's life, and therefore one's happiness. Rand wrote:

"Man has been called a rational being, but rationality is a matter of choice — and the alternative his nature offers him is: rational being or suicidal animal. Man has to be man — by choice; he has to hold his life as a value — by choice; he has to learn to sustain it — by choice; he has to discover the values it requires and practice his virtues — by choice.

"A code of values accepted by choice is a code of morality."

There is a difference, therefore, between rational self-interest as pursuit of one's own life and happiness in reality, and what Ayn Rand called "selfishness without a self" - a range-of-the-moment pseudo-"selfish" whim-worship or "hedonism." A whim-worshipper or "hedonist," according to Rand, is not motivated by a desire to live his own human life, but by a wish to live on a sub-human level. Instead of using "that which promotes my (human) life" as his standard of value, he mistakes "that which I (mindlessly happen to) value" for a standard of value, in contradiction of the fact that, existentially, he is a human and therefore rational organism. The "I value" in whim-worship or hedonism can be replaced with "we value," "he values," "they value," or "God values," and still it would remain a dissociated-from-reality ethics-killer. Rand repudiated the equation of rational selfishness with hedonistic or whim-worshipping "selfishness-without-a-self." She held that the former is good, and the latter evil, and that there is a fundamental difference between them. A corollary to Rand's endorsement of self-interest is her rejection of the ethical doctrine of altruism — which she defined in the sense of August Comte's altruism (he coined the term), as a moral obligation to live for the sake of others.

Rand defined a value as "that which one acts to gain and/or keep." The rational individual's choice of values to pursue is guided by his need, if he chooses to live, to act so as to maintain and promote his own life. Rand did not hold that values proper to human life are "intrinsic" in the sense of being independent of one's choices, or that there are values that an individual must pursue by command or imperative ("reason accepts no commandments"). Neither did Rand consider proper values "subjective," to be pursued just because one has chosen, perhaps arbitrarily, to pursue them. Rather, Rand held that valid values are "objective," in the sense of being identifiable as serving to preserve and enhance one's life. Some values are specific to the nature of each individual, but there are also universal human values, including the preservation of one's own individual rights, which Rand defined as "conditions of existence required by man's nature for his proper survival."

Objectivism holds that morality is a "code of values accepted by choice." According to Leonard Peikoff, Rand held that "man needs for one reason only: he needs it in order to survive. Moral laws, in this view, are principles that define how to nourish and sustain human life; they are no more than this and no less." Objectivism does not claim that there is a moral requirement to choose to value one's life. As Allan Gotthelf points out, for Rand, "Morality rests on a fundamental, pre-moral choice:" the moral agent's choice to live rather than die, so that the moral "ought" is always contextual and agent-relative. To be moral is to choose that which promotes one's life in one's actual context. There are no "categorical imperatives" (as in Kantianism) that an individual would be obliged to carry out regardless of consequences for his life.

Politics: Individual rights and capitalism

Objectivist politics begins with meta-politics: the question of whether, and if so why, a rational agent needs a set of principles - a politics - for living with others in society. The starting point for Rand's meta-politics is the observation, which she calls "the Trader Principle," that one can preserve and enhance one's life more effectively by interacting voluntarily, by way of cooperation and trade, with other individuals. The rational individual needs a politics to tell him how to preserve his individual rights while interacting with, and benefiting from cooperation and trade with, other individuals in society.

The first principle derived in Objectivist politics is harmony of interests: Objectivism rejects the possibility of a long-term conflict of interest between two rational individuals under normal circumstances, though it may happen in emergencies, broadly defined as situations outside the scope of the trader principle (see the section on "Logic and errors of logic" in the article on Objectivist epistemology for discussion of contextual scope.) Rand then derives the principle of "non-aggression", or "non-initiation of force." It follows from these that it is a founding principle of all legitimate social institutions, and the only proper function of government, to assure that social rights, "moral principles that define and sanction the individual's freedom of action in a social context," correspond exactly to individual rights, "conditions of existence required by man's nature for his proper survival." For this reason, there is in the Objectivist view no such thing as a "collective right" that would go beyond what is required to maintain the individual rights of individuals.

Although Objectivist literature does not use the term "natural rights," the rights it recognizes are based directly on the nature of human beings as described in Objectivist epistemology and Objectivist ethics. Since human beings must make choices in order to survive as human beings, the basic requirement of a human life is the freedom to make, and act on, one's own independent rational judgment, according to one's self-interest.

Thus, according to Rand, the fundamental right of human beings is the right to (live one's own) life. By this phrase Objectivism means the right to act in furtherance of one's own life — not the right to have one's life protected, or to have one's survival guaranteed, by the involuntary effort of other human beings. Indeed, on the Objectivist account, one of the corollaries of the right to life is the right to property which, according to Objectivism, typically represents the product of one's own effort; on this view, one person's right to life cannot entail the right to dispose of another's private property, under any circumstances. Under Objectivism, one has the right to transfer one's own property to whomever one wants for whatever reason, but such a transfer is only ethical if it is made under the terms of a trade freely consented to by both parties, in the absence of any form of coercion, each with the expectation that the trade will benefit them. Objectivism holds that human beings have the right to manipulate nature in any way they see fit, as long as it does not infringe on the rights of others. From this, the right to property arises.

On the Objectivist account, the rights of other human beings are not of direct moral import to the agent who respects them; they acquire their moral purchase through an intermediate step. An Objectivist respects the rights of other human beings out of the recognition of the value to himself or herself of living in a world in which the freedom of action of other rational (or potentially rational) human beings is respected. One's respect for the rights of others is founded on the value, to oneself, of other persons as actual or potential partners in cooperation and trade.

For these reasons Ayn Rand defends capitalism as the ideal form of human society. Objectivism reserves the name "capitalism" for full laissez-faire capitalism — i.e., a society in which individual rights are consistently respected and in which all property is (therefore) privately owned. Any system short of this is regarded by Objectivists as a "mixed economy" consisting of certain aspects of capitalism and its opposite (usually called socialism or statism), with pure socialism at the opposite extreme.

Far from regarding capitalism as a dog-eat-dog pattern of social organization, Objectivism regards it as a beneficent system in which the innovations of the most creative benefit everyone else in the society. Indeed, Objectivism values creative achievement itself and regards capitalism as the only kind of society in which it can flourish.

A society is, by Objectivist standards, moral to the extent that individuals are free to pursue their goals. This freedom requires that human relationships of all forms be voluntary (which, in the Objectivist view, means that they must not involve the use of physical force), mutual consent being the defining characteristic of a free society. Thus the proper role of institutions of governance is limited to using force in retaliation against those who initiate its use — i.e., against criminals and foreign aggressors. Economically, people are free to produce and exchange as they see fit, with as complete a separation of state and economics as of state and church.

Aesthetics: Romantic realism

The Objectivist theory of art flows fairly directly from its epistemology, by way of "psycho-epistemology" (Objectivism's term for the study of human cognition as it involves interactions between the conscious and the subconscious mind). Art, according to Objectivism, serves a human cognitive need: it allows human beings to grasp concepts as though they were percepts.

Objectivism defines "art" as a "selective re-creation of reality according to an artist's metaphysical value-judgments" — that is, according to what the artist believes to be ultimately true and important about the nature of reality and humanity. In this respect Objectivism regards art as a way of presenting abstractions concretely, in perceptual form.

The human need for art, on this view, stems from the need for cognitive economy. A concept is already a sort of mental shorthand standing for a large number of concretes, allowing a human being to think indirectly or implicitly of many more such concretes than can be held explicitly in mind. But a human being cannot hold indefinitely many concepts explicitly in mind either — and yet, on the Objectivist view, needs a comprehensive conceptual framework in order to provide guidance in life.

Art offers a way out of this dilemma by providing a perceptual, easily grasped means of communicating and thinking about a wide range of abstractions. Its function is thus similar to that of language, which uses concrete words to represent concepts.

Objectivism regards art as the only effective way to communicate a moral or ethical ideal. Objectivism does not, however, regard art as propagandistic: even though art involves moral values and ideals, its purpose is not to educate, only to show or project.

Moreover, art need not be, and often is not, the outcome of a full-blown, explicit philosophy. Usually it stems from an artist's sense of life (which is preconceptual and largely emotional), and its appeal is similar to the viewer's or listener's sense of life.

Generally Objectivism favors an esthetic of Romantic Realism, which on its Objectivist definition is a category of art treating the existence of human volition as true and important. In this sense, for Objectivism, Romantic Realism is the school of art that takes values seriously, regards human reason as efficacious, and projects human ideals as achievable. Objectivism contrasts such Romantic Realism with Naturalism, which it regards as a category of art that denies or downplays the role of human volition in the achievement of values.

The term romanticism, however, is often affiliated with emotionalism, which Objectivism is completely opposed to (though Objectivism seems to hold romanticism as more emotional than most forms of art, and as less emotionalist i.e. relating to the use of emotions for decision-making.) Many romantic artists, in fact, were subjectivists and/or socialists. Most Objectivists who are also artists subscribe to what they call Romantic Realism, which is what Ayn Rand labeled her own work.

Some Objectivists use the term Byronic to label the sorts of romanticism with which Objectivists disagree.

Monographs

Leonard Peikoff is Ayn Rand's designated intellectual heir, and his book, Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand (E. P. Dutton), is a comprehensive survey of Ayn Rand's philosophy. Objectivism is central to Ronald Merrill's introductory monograph The Ideas of Ayn Rand (Open Court.) Monographs on specific aspects of Objectivism include Viable Values (Rowman & Littlefield) and Ayn Rand's Normative Ethics: the Virtuous Egoist (Cambridge University Press) by Tara Smith, The Evidence of the Senses (Louisiana State University Press) by David Kelley, and The Biological Basis of Teleological Concepts (The Ayn Rand Institute Press) by Harry Binswanger.

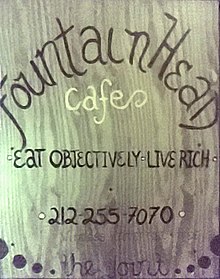

Cultural impact

Ayn Rand's ideas are often supported with great passion or derided with great disgust, with little in between. Some of this comes from Rand challenging fundamental tenets of the Judeo-Christian tradition, and some may be due to her own all-or-nothing, take-it-or-leave-it approach to her work. She warned her readers that, "If you agree with some tenets of Objectivism, but disagree with others, do not call yourself an Objectivist; give proper authorship for the parts you agree with — and then indulge any flights of fancy you wish, on your own." Writers who are influenced (to whatever extent) by Rand's philosophy sometimes call themselves "Randians."

Rand was very critical of the state of the academic fields of literature and philosophy; once threatening legal action against an academic who was preparing a critical study of her work. Objectivism has been called "fiercely anti-academic," a collection of "non-mainstream philosophical works," and more of an ideological movement than a well-grounded philosophy.

In recent years Rand's works are more likely to be encountered in the classroom than in decades past. Since 1999, several monographs were published and a refereed Journal of Ayn Rand Studies began. In 2006 the University of Pittsburgh held a conference focusing on Objectivism. In addition, two Objectivist philosophers (Tara Smith and James Lennox) hold tenured positions at two of the fifteen leading American philosophy departments. Objectivist programs and fellowships have been supported at the University of Pittsburgh, University of Texas at Austin and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Ayn Rand Society, dedicated to fostering the scholarly study of Objectivism, is affiliated with the American Philosophical Association's Eastern Division.

Rand is not found in many of the comprehensive academic reference texts, including The Oxford Companion to Philosophy or The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, each over a thousand pages long, nor is there an entry for her on the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. A lengthy article on Rand appears in the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and she has a brief entry in the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy which features the following passage:

The influence of Rand’s ideas was strongest among college students in the USA but attracted little attention from academic philosophers. Rand’s political theory is of little interest. Its unremitting hostility towards the state and taxation sits inconsistently with a rejection of anarchism, and her attempts to resolve the difficulty are ill-thought out and unsystematic

Allan Gotthelf responded unfavorably to this entry and came to her defense. He and other scholars have argued for a more academic study of Objectivism, viewing Rand's philosophy as a unique and intellectually interesting defense of liberalism that is worth debating.

Despite the relative lack of academic attention paid to Objectivism, particularly early on, Ayn Rand's books remain popular selling over 400,000 copies per year.

Criticism

For detailed summaries of specific responses to Objectivism discussed below, see bibliography of work on Objectivism.

Objectivism

Philosophers whose epistemologies give concepts and propositions a universal rather than a contextually limited scope criticize Objectivism on logical grounds. Louis P. Pojman writes that some of Objectivism's central claims are demonstrably false. Robert Nozick, a prominent libertarian philosopher, largely agreed with Rand on political issues but disagreed with Objectivism's grounding of politics in Objectivist ethics.

According to Jenny Hayle, Rand's "philosophical movement, Objectivism was often to be called a cult....". Murray Rothbard, Jeff Walker and Michael Shermer argue that Objectivism's claim "that there are objective truths and realities, particularly in the moral realm dealing with values" contributes to manifestations of cultism that they found within the Objectivist movement (see Objectivist movement for details.) Walker compares it with organizations that have been considered cults, such as Scientology. Shermer, who considers Objectivism "perfectly sound ... the best thing going" and criticizes cultism from a Randian perspective, writes that people like "...Peikoff and his Ayn Rand Institute did precisely what a cult would do by squelching criticism." However, answering a fan letter in which she saw signs of incipient cultism, Rand wrote, "A blind follower is precisely what my philosophy condemns and what I reject. Objectivism is not a mystic cult."

Psychologists Albert Ellis and Nathaniel Branden argue that there are significant psychological hazards in following the philosophy of Ayn Rand.

Ayn Rand on the history of philosophy

Rand regarded her philosophical efforts as the beginning of the correction of a deeply troubled world, and she believed that the world has gotten into its present troubled state largely through the uncritical acceptance, by both intellectuals and others, of traditional philosophy. In the title essay of her early work For the New Intellectual, Rand levels serious criticisms of canonical historical philosophers, especially Plato, David Hume, Immanuel Kant, G. W. F. Hegel, Karl Marx, Friedrich Nietzsche, and Herbert Spencer. In her later book, Philosophy: Who Needs It, she repeats and enlarges upon her criticisms of Kant, and she also accuses Harvard political theorist John Rawls of gross philosophical errors. Rand is accused of misinterpreting the works of many of the philosophers she identified as responsible for advancing bad and false philosophy.

Interpretation of David Hume

Rand is criticized for her outright rejection of David Hume's ideas at the foundations of her philosophy. Hume famously maintained, "No is implies an ought," but Rand disagreed by arguing that values are a species of fact (see is-ought problem). She wrote, "In answer to those philosophers who claim that no relation can be established between ultimate ends or values and the facts of reality, let me stress that the fact that living entities exist and function necessitates the existence of values and of an ultimate value which for any given living entity is its own life. Thus the validation of value judgments is to be achieved by reference to the facts of reality. The fact that a living entity is, determines what it ought to do."

Interpretation of Immanuel Kant

Rand's interpretation and criticism of the views of Immanuel Kant, in particular, have sparked considerable controversy.

Critics take issue with Rand's interpretation of Kant's metaphysics: like early critics of Kant, Rand interpreted Kant as an empirical idealist. It is a long-standing question of Kant scholarship whether this interpretation is correct; in the first edition of the Critique of Pure Reason, Kant claimed that his transcendental idealism was different from empirical idealism; in the second edition he even attempted to refute the latter. Contemporary philosophers such as Jonathan Bennett, James van Cleve, and Rae Langton continue to debate this issue.

Other critics focus on Rand's reading of Kant's ethical philosophy. Rand held that Kantian ethics improperly takes self-interest out of ethics: "What Kant propounded was full, total, abject selflessness: he held that an action is moral only if you perform it out of a sense of duty and derive no benefit from it of any kind, neither material nor spiritual; if you derive any benefit, your action is not moral any longer...It is Kant's version of altruism that people, who have never heard of Kant, profess when they equate self-interest with evil." Kant clearly did maintain (in his Groundwork for the Metaphysics of Morals) that an action solely motivated by inclination or self-interest is entirely lacking in moral worth. While many Continental philosophers influenced by Hegel and Nietzsche would agree that Kant's own ethical theorizing is itself motivated by or expresses a sort of ascetic masochism, and many analytic philosophers championing virtue ethics (e.g., Bernard Williams) would agree that Kantian ethics places excessive demands on the moral agent, Rand appears alone in characterizing Kantianism as always requiring self-sacrificial effects. The contemporary philosopher Thomas E. Hill has explicitly defended Kant against this charge in his article, "Happiness and Human Flourishing in Kant's Ethics," in the anthology Human Flourishing.

References

- So identified by sources including:

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2006), s.v. "Ayn Rand" Retrieved June 22, 2006.

Smith, Tara. Review of "On Ayn Rand." The Review of Metaphysics 54, no. 3 (2001): 654–655. Retrieved from ProQuest Research Library.

Encyclopædia Britannica (2006), s.v. "Rand, Ayn." Retrieved June 22, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2006), s.v. "Ayn Rand" Retrieved June 22, 2006.

- One source notes: "Perhaps because she so eschewed academic philosophy, and because her works are rightly considered to be works of literature, Objectivist philosophy is regularly omitted from academic philosophy. Yet throughout literary academia, Ayn Rand is considered a philosopher. Her works merit consideration as works of philosophy in their own right." (Jenny Heyl, 1995, as cited in Mimi R Gladstein, Chris Matthew Sciabarra(eds), ed. (1999). Feminist Interpretations of Ayn Rand. Penn State Press. ISBN 0-271-01831-3.

{{cite book}}:|editor=has generic name (help), p. 17) - Rand, Ayn. Introducing Objectivism, in Peikoff, Leonard, ed. The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought. Meridian, New York 1990 (1962.)

- ^ Peikoff, Leonard (1993). Objectivism: The Philosophy of Ayn Rand. Meridian. ISBN 978-0452011014.

- ^ Rand, Ayn (1996). Atlas Shrugged (35th Anniv edition). Signet Book.

{{cite book}}: Text "isbn 0-451-19114-5" ignored (help) - Rubin, Harriet (2007-09-15). "Ayn Rand's Literature of Capitalism". The New York Times. Retrieved 2007-09-18.

- Rand, Ayn, "What Is Capitalism?" in Capitalism: The Unknown Ideal, p.23.

- Gotthelf, Allan (2000). On Ayn Rand. Wadsworth.

- ^ Rand, Ayn (1990). Introduction to Objectivist Epistemology. Meridian. ISBN 0-452-01030-6.

- ^ Rand, Ayn, with additional articles by Nathaniel Branden. (1964) The Virtue of Selfishness. Signet Book.

- Gotthelf, Allan. On Ayn Rand, Wadsworth, 2000, p. 84

- ^ McLemee, Scott (September 1999). "The Heirs Of Ayn Rand: Has Objectivism Gone Subjective?". Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- Harvey, Benjamin (2005-05-15). "Ayn Rand at 100: An 'ism' struts its stuff". Rutland Herald. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- Sharlet, Jeff (1999-04-09). "Ayn Rand has finally caught the attention of scholars: New books and research projects involve philosophy, political theory, literary criticism, and feminism". The Chronicle of Higher Education. 45 (31): 17–18.

- "Concepts and Objectivity: Knowledge, Science, and Values" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- Philosophy departments of the United States, ranked by the Philosophical Gourmet Report

- "Proceedings and Addresses of The American Philosophical Association - Eastern Division Program" (PDF). 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-25.

- "Ayn Rand at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy". 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- "The Entry on Ayn Rand in the new Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy". Retrieved 2007-07-20., Error in Webarchive template: Empty url.

- Uyl, Douglas J. Den (1998). "On Rand as philosopher" (PDF). Reason Papers. 23: 70–71. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- "Rand's lesson endures". 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- Louis P. Pojman, "Egoism and Altruism: A Critique of Ayn Rand," in The Moral Life: An Introductory Reader in Ethics and Literature, ed. Louis P. Pojman, Oxford University Press, 2004, pp. 580-587.

- Nozick, Robert, "On the Randian Argument," in Socratic Puzzles, Harvard University Press, 1997, pp. 249-264

- Hayle, Jenny (1995). "9". In Mary Ellen White (ed.). A history of women philosophers. Springer. p. 207.

- Rothbard, Murray. ""The sociology of the Ayn Rand cult."". Retrieved 2006-03-31.

- ^ Walker, Jeff (1999). The Ayn Rand Cult. Chicago: Open Court. ISBN 0-8126-9390-6 Cite error: The named reference "walker" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Shermer, Michael. ""The Unlikeliest Cult in History"". Retrieved 2006-03-30. Originally published in Skeptic vol. 2, no. 2, 1993, pp. 74-81.

- ^ Hudgins, Ed. ""Out of Step: TNI's Interview with Michael Shermer"". Originally published in The New Individualist vol. 10, nos. 1-2, 2007

- Shermer, Michael (2002). Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time. Owl Books.

- Rand, Ayn. In Berliner, Michael S., ed., Letters of Ayn Rand, p. 592 Letter dated December 10 1961, Plume (1997), ISBN 0-452-27404-4, as cited in ""Ayn Rand Biographical FAQ: Did Rand organize a cult?"". Retrieved 2006-06-25.

- Ellis, Albert. Is Objectivism a Religion? Lyle Stuart, New York 1968.

- Branden, Nathaniel. The Benefits and Hazards of the Philosophy of Ayn Rand. Journal of Humanistic Psychology v.24, no. 4, pp.39-64.

- Seddon, Fred. Ayn Rand, Objectivists, and the History of Philosophy, University Press of America (2003), ISBN 0-7618-2308-5

- Walsh, George V., "Ayn Rand and the Metaphysics of Kant," Journal of Ayn Rand Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, Fall 2000, pp. 69-103.

- Kant, Immanuel, "Critique of the Fourth Paralogism of Transcendental Psychology," Critique of Pure Reason, trans., Norman Kemp Smith, Bedford Books, 1969, pp. 344-352.

- Kant, Immanuel, "Refutation of Idealism," Critique of Pure Reason, trans., Norman Kemp Smith, Bedford Books, 1969, pp. 244-256.

- Jonathan Bennett, Kant's Analytic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966.

- James Van Cleve, Problems from Kant. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Rae Langton, Kantian Humility: Our Ignorance of Things in Themselves, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Bencivenga, Ermanno. "Kant's Sadism." Philosophy and Literature (April 1996), 20(1):39-46.

- Williams, Bernard. "Persons, Character and Morality," in Moral Luck: Philosophical Papers 1973-1980, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1981, p. 18.

External links

- Ayn Rand Institute

- Essentials of Objectivism at the Ayn Rand Institute

- Ayn Rand Novels — a site aimed at introducing students to Objectivism

- Ayn Rand Society — Includes an overview

- The Center for the Advancement of Capitalism

- The Objectivism Reference Center — Includes both advocacy and criticism articles

- The Objectivist Center/The Atlas Society