This is an old revision of this page, as edited by MichChemGSI (talk | contribs) at 15:53, 6 May 2011 (→History). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 15:53, 6 May 2011 by MichChemGSI (talk | contribs) (→History)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) | |

| Identifiers | |

|---|---|

| CAS Number | |

| Properties | |

| Chemical formula | (C13H8)n |

| Molar mass | Variable |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C , 100 kPa).

| |

Polyfluorenes are a class of polymeric materials. They are used in academic and industrial research because of their optical and electrical properties. They are a prototypical conjugated polymer but they are the only class of conjugated polymers which can be tuned to emit light throughout the entire visible region. They are not a naturally occurring material, but are designed and synthesized for their applications. Modern chemistry has enabled adaptable synthesis and control over polyfluorenes that has facilitated use in many organic electronic applications. Polyfluorenes are primarily interesting because of the optoelectronic properties imbued by their chromophoric constituents and their extended conjugation. The design of polyfluorene derivatives relies on the character and properties of their monomers. Thus, the discovery and development of these polymeric repeat units has had a profound influence on the development of polyfluorenes.

As with other conjugated polymers, researchers investigate using polyfluorenes in light-emitting diodes (LEDs), field-effect transistors (FETs), and plastic solar cells. While polyfluorenes give high photoluminescence quantum yields, their properties differ depending upon the identity of the different groups at the 9,9 position of the fluorene monomer.

History

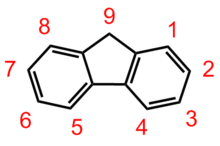

Despite sounding like the element, the element fluorine does not have anything to do with polyfluorene. Fluorene, a principal repeat unit in polyfluorene derivatives, was isolated from coal tar and discovered by Marcellin Berthelot prior to 1883. So-named due to its interesting fluorescence, fluorene became the subject of chemical-structure related color variation (visible rather than luminescent), among other things, throughout the early to mid-20th century. Since it was an interesting chromophore researchers wanted to understand which parts of the molecule were chemically reactive, and how substituting these sites influenced the color. For instance, by adding various electron donating or electron accepting moieties to fluorene, and by reacting with bases, researchers were able to change the color of the molecule.

The physical properties of the fluorene molecule were recognizably desirable for polymers; as early as the 1970s researchers began incorporating this moiety into polymers. For instance, because of fluorene’s rigid, planar shape a polymer containing fluorene was shown to exhibit enhanced thermo-mechanical stability. Perhaps more interesting, however, was the promise of integrating the optoelectronic properties of fluorene into a polymer. Reports of the oxidative polymerization of fluorene (into a fully conjugated form) exist from at least 1972. However, it was not until after the highly publicized high conductivity of doped polyacetylene, presented in 1977 by Heeger, MacDiarmid and Shirakawa, that substantial interest in the electronic properties of conjugated polymers was aroused.

As interest in conducting plastics grew, fluorene again found application. The aromatic nature of fluorene makes it an excellent candidate component of a conducting polymer because it can stabilize and conduct a charge; in the early 1980s fluorene was electropolymerized into conjugated polymer films with conductivities of 10 S cm. Additionally, the optical properties (such as variable luminescence and visible light absorption) that accompany the extended conjugation in polymers of fluorene have become increasingly attractive for device applications. Throughout the 1990s and into the 2000s, many devices such as organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), organic solar cells., organic thin film transistors, and biosensors have all taken advantage of the luminescent, electronic and absorptive properties of polyfluorenes.

Properties

Polyfluorenes encompass an important class of polymers which have the potential to act as both electroactive and photoactive materials. This is partly due to the shape of fluorene. Fluorene is mostly planar; p-orbital overlap at the linkage between its two benzene rings results in conjugation across the molecule. This in turn allows for a reduced band gap due to the delocalized excited state molecular orbitals. Furthermore, since the degree of delocalization and the spatial location of the orbitals on the molecule is influenced by the electron donating (or withdrawing) character of its substituents, the band gap energy can be varied. This chemical control over the band gap directly dictates the color of the molecule by limiting the energies of light which it absorbs.

Interest in polyfluorene derivatives has increased because of their high photoluminescence quantum efficiency, high thermal stability, and also because of their facile color tunability, which can be obtained by introducing low-band-gap co-monomers. Research in this field has increased significantly due to potential application in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). In this application, polyfluorenes are desirable because they are the only family of conjugated polymers that can emit colors spanning the entire visible range with high efficiency and low operating voltage. Furthermore, polyfluorenes are relatively soluble in most solvents that makes them ideal for general applications.

Another important quality of polyfluorenes is their thermotropic liquid crystallinity which allows the polymers to be used on rubbed polyimide layers. Thermotropic liquid crystallinity refers to the polymers ability to exhibit a phase transition into the liquid crystal phase as the temperature is changed. This is very important to the development of liquid crystal displays (LCDs) because the synthesis of liquid crystal displays requires that the liquid-crystal molecules at the two glass surfaces of the cell be aligned parallel to the two polarizer foils. This can only be done by coating the inner-surfaces of the cell with a thin, transparent film of polyamide which is then rubbed with a velvet cloth. Microscopic grooves are then generated in the polyamide layer and the liquid crystal in contact with the polyamide, which is polyfluorene, can align in the rubbing direction. In addition to LCDs, polyfluorene can also be used to synthesize light emitting diodes (LEDs). By using polyfluorene, LEDs have been synthesized that can emit polarized light with polarization ratios of more than 20 and with brightness of 100 cd m. Even though this is very impressive it is not sufficient for general applications.

Challenges associated with polyfluorenes

Polyfluorenes often show both excimer and aggregate formation upon thermal annealing or when current is passed through them. Excimer formation involves the generation of dimerized units of the polymer which emit light at lower energies than the polymer itself. This hinders the use of polyfluorenes for most applications, including light-emitting diodes (LED). When excimer or aggregate formation occurs this lowers the efficiency of the LEDs by decreasing the efficiency of charge carrier recombination. Excimer formation also causes a red shift in the emission spectrum.

Polyfluorenes can also undergo decomposition. There are two known ways in which decomposition can occur. The first involves the oxidation of the polymer that leads to the formation of an aromatic ketone, and the formed carbonyl group quenches the fluorescence. The second process results in aggregation that leads to a red-shifted fluorescence, reduced intensity, exciton migration and relaxation through excimers.

Researchers have attempted to eliminate excimer formation and enhance the efficiency of polyfluorenes by copolymerizing polyfluorene with anthracene and end-capping polyfluorenes with bulky groups which could sterically hinder excimer formation. Additionally, researchers have tried adding large substituents at the ninth position of the fluorine in order to inhibit excimer and aggregate formation. Furthermore, researchers have tried to improve LEDs by synthesizing fluorene-triarylamine copolymers and other multilayer devices that are based on polyfluorenes that can be cross-linked. These have been found to have high brightness and reasonable efficiencies.

Aggregation has also been combated through chemical structure variation. For example, when conjugated polymers aggregate (as they have a natural tendency to do in the solid state), their emission can be self-quenched, reducing luminescent quantum yields and reducing luminescent device performance. In opposition to this tendency, researchers have used tri-functional monomers to create highly branched polyfluorenes which resist aggregation due to their bulkiness. This design strategy has achieved luminescent quantum yields of 42% in the solid state. Unfortunately, this solution reduces the ease of processability of the material because branched polymers have increased chain entanglement.

Another problem commonly encountered by polyfluorenes is a commonly observed broad green, parasitic emission which detracts from the color purity and efficiency needed for an OLED. Initially attributed to excimer emission, this green emission has been shown to be due to the formation of ketone defects along the fluorene polymer backbone (oxidation of the 9 position on the monomer in figure 1) at incompletely substituted 9 positions of the fluorene monomer. Routes to combat this involve ensuring full substitution of the monomer’s active site, or including aromatic substituents. These solutions may present sub-optimal structures (in terms of bulkiness) or may be synthetically difficult.

Synthesis and design

One of the reasons that conjugated polymers, polyfluorene included, are such a versatile class of material is because of the variability of relevant properties that molecular design and synthesis afford. Polyfluorenes are designed and synthesized for their applications, usually requiring appropriate luminescent emission, appropriate absorption wavelengths and processability, among other properties. As mentioned above, the color of conjugated molecules can be designed through control over the electron donating or withdrawing character of the substituents on fluorene or similarly, of the comonomers in polyfluorene (as in figure 4). Processability, on the other hand, is primarily the result of the solubility of the polymers because solution state processing is very common. Since conjugated polymers, with their planar structure, tend to aggregate bulky side chains are added (to the 9 position of fluorene) to prevent this and to instill solubility. With these concepts in mind, an understanding of the synthesis of polyfluorenes can be developed.

Oxidative polymerization

The earliest polymerizations of fluorene were oxidative polymerization with AlCl3 or FeCl3, and more commonly electropolymerization. Electropolymerization is an easy route to obtain thin, insoluble conducting polymer films. However, it does not provide easy control over the site on the monomer from which chain growth occurs, and since the polymer is insoluble, processing and characterization are difficult. Oxidative polymerization produces a similarly poor site-selectivity on the monomer for chain growth resulting in poor control over the regularity of the polymers structure, especially for asymmetric monomers. However, oxidative polymerization does produce soluble polymers (from side-chain containing monomers) which are more easily characterized with nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Cross coupling polymerizations

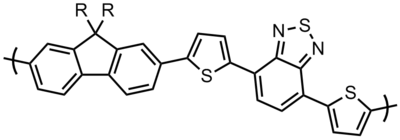

The design of polymeric properties requires great control over the structure of the polymer. For instance, low band gap polymers require regularly alternating electron donating and electron accepting monomers (such as that in figure 4 with fluorene on the left and benzothiadiazole on the mid-right). More recently, many popular cross-coupling chemistries have been applied to polyfluorenes and have enabled controlled polymerization; Palladium catalyzed cross couplings such as Suzuki coupling , Heck coupling , etc., as well as nickel catalyzed Yamamoto and Grignard coupling reactions have been applied to polymerization of fluorene derivatives. Such routes have enabled excellent control over the properties of polyfluorenes; the polymer in figure 4, with a band gap of 1.78 eV when the side chains are alkoxy, appears blue because it is absorbing in the red wavelengths.

Design

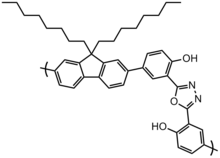

Modern coupling chemistries allow other properties of polyfluorenes to be controlled through implementation of complex molecular designs. For instance, using Suzuki coupling (figure 5) the complicated polymer in figure 6 was produced. It has excellent (94%, solution in chloroform) photoluminescent quantum yields, partly due to its fluorene monomer, excellent stability, due to its oxadiazole comonomer, good solubility, due to its many and branched alkyl side chains, and has an amine functionalized side chain for tethering to other molecules or to a substrate. The luminescent color of polyfluorenes can be changed, for example, (from blue to green-yellow in figure 2) by adding functional groups which participate in excited state intramolecular proton transfer (ESIPT). Exchanging the alkoxy side chains for alcohol side groups (figure 3) allows for energy dissipation (and a red-shift in emission) through reversible transfer of a proton from the alcohol to the nitrogen (on the oxadiazole). These complicated molecular structures were engineered to have these properties and were only able to be realized through careful control of their ordering and side group functionality through polymerization chemistry.

Applications

Organic Light-emitting diodes (OLEDs)

Main article: Organic light-emitting diodeIn recent years many industrial efforts have been focused on tuning color using polyfluorenes. It was found that by doping green or red emitting materials into polyfluorenes one could tune the color emitted by the polymers. Since polyfluorene homopolymers emit higher energy blue light, they can transfer energy via Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) to lower energy emitters. In addition to doping, it was found that one could tune the color of polyfluorenes by copolymerizing the fluorene monomers with other low band gap monomers. Researchers at the Dow Chemical Company synthesized several fluorene-based copolymers by alternating copolymerization using 5,5-dibromo-2,2-bithiophene which showed yellow emission and 4,7-dibromo-2,1,3-benzothiadiazole, which showed green emission. Other copolymerizations are also suitable; researchers at IBM performed random copolymerization of fluorene with 3,9(10)-dibromoperylene,4,4-dibromo-R-cyanostilbene, and 1,4-bis(2-(4-bromophenyl)-1-cyanovinyl)-2-(2-ethylhexyl)-5-methoxybenzene. Only a small amount of the co-monomer, approximately 5%, was needed to tune the emission of the polyfluorene from blue to yellow. This example further illustrates that by introducing monomers that have a lower band gap than the fluorene monomer, one can tune the color that is emitted by the polymer.

Substitution at the ninth position with various moieties has also been examined as a means to control the color emitted by polyfluorene. In the past researchers have tried putting alkyl substituents on the ninth position, however it has been found that by putting bulkier groups, such as alkoxyphenyl groups, the polymers had enhanced blue emission stability and superior polymer light-emitting diode performance (compared to polymers which have alkyl substituents at the ninth position).

Polymer solar cells

Main article: Polymer solar cell

Polyfluorenes are also used in polymer solar cells because of their affinity for property tuning. Copolymerization of fluorene with other monomers allows researchers to optimize the absorption and electronic energy levels as a means to increase the photovoltaic performance. For instance, by lowering the band gap of polyfluorenes, the absorption spectrum of the polymer can be adjusted to coincide with the maximum photon flux region of the solar spectrum. This helps the solar cell absorb more of the suns energy and to increase its energy conversion efficiency; donor-acceptor structured copolymers of fluorene have achieved efficiencies above 4% when their absorption edge was pushed to 700 nm.

The voltage of polymer solar cells has also been increased through the design of polyfluorenes. These devices are typically produced by blending electron accepting and electron donating molecules which help separate charge to produce power. In polymer blend solar cells, the voltage produced by the device is determined by the difference between the electron donating polymer’s highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) energy level and the electron accepting molecules lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy level. By adding electron withdrawing pendant molecules to conjugated polymers, their HOMO energy level can be lowered. For instance by adding electronegative groups on the end of conjugated side chains, researchers lowered the HOMO of a polyfluorene copolymer to −5.30 eV and increased the voltage of a solar cell to 0.99 V.

Typical polymer solar cells utilize fullerene molecules as electron acceptors because of their low LUMO energy level (high electron affinity). However the tunability of polyfluorenes allows their LUMO to be lowered to a level appropriate for use as an electron acceptor. Thus, polyfluorene copolymers have also been used in polymer:polymer blend solar cells, where their electron accepting, electron conducting and light absorbing properties enhance device performance.

References

- ^ Scherf, Ullrich; Neher, Dieter; Grimsdale, Andrew; Mullen, Klaus (2008). "Bridged polyphenylenes from polyfluorenes to ladder polymers: colour control by copolymerization". Polyfluorenes. Leipzig Germany: Springer. pp. 10–18. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-68734-4. ISBN 978-3-540-68733-7.

- ^ Hodgkinson, W. R.; Matthews, F.E. (1883). "XXIII.-Note on some derivatives of fluorene, C13H10". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 43: 163–172. doi:10.1039/CT8834300163.

- Ann. Chim. Phys. 12 (4): 222. 1867 http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k348222/f221.image.

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Vaughan, G.A.; Grant, D.W. (1954). "The determination of fluorene in tar fractions". Analyst. 79: 776–779. doi:10.1039/AN9547900776.

- Smedley, Ida (1905). "CXXV.—Studies on the origin of colour. Derivatives of fluorene". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions. 87: 1249–1255. doi:10.1039/CT9058701249.

- Sawicki, Eugene (1952). "Differentiating color test for fluorene derivatives". Analytical Chemistry. 24 (7): 1204–1205. doi:10.1021/ac60067a042.

- Bell, Vernon L. (1976). "Polyimide Structure-Property relationships. I. Polymers from fluorene-derived diamines". Journal of Polymer Science. 14: 225–235. doi:10.1002/pol.1976.170140119.

- ^ Prey, Von Vinzenz; Schindlbauer, Hellmuth; Cmelka, Dieter (1973). "Versuche zur Polymerisation von Fluoren". Die Angewandte Makromolekulare Chemie. 28: 137–143. doi:10.1002/apmc.1973.050280111.

- ^ Waltman, Robert J.; Bargon, Joachim (1985). "The electropolymerization of polycyclic hydrocarbons: substituent effects and reactivity/structure correlations". Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 194: 49–62. doi:10.1016/0022-0728(85)87005-4.

- ^ Rault-Berthelot, Joelle; Simonet, Jaques (1985). "The anodic oxidation of fluorene and some of its derivatives – conditions for the formation of a new conducting polymer". The Journal of Electroanalytical Chemistry. 182: 187–192. doi:10.1016/0368-1874(85)85452-6.

- ^ Pei, Qibing; Yang, Yang (1996). "Efficient photoluminescence and electroluminescence from a soluble polyfluorene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 118: 7416–7417. doi:10.1021/ja9615233.

- ^ Bundgaard, Eva; Krebs, Frederik C. (2007). "Low band gap polymers for organic photovoltaics". Solar Energy Materials & Solar Cells. 91: 954–985. doi:10.1016/j.solmat.2007.01.015.

- Sirringhaus, H.; Wilson, R.J.; Friend, R.H.; Inbasekaran, M.; Wu, W.; Grell; Bradley, D.D.C. (2000). "Mobility enhancement in conjugated polymer field-effect transistors through chain alignment in a liquid crystalline phase". Applied Physics Letters. 77 (3): 406–408. doi:10.1063/1.126991.

{{cite journal}}:|first6=missing|last6=(help); Unknown parameter|first 7=ignored (|first7=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|last 6=ignored (|last6=suggested) (help) - ^ Lee, Kangwon; Maisel, Katharina; Rouillard, Jean-Marie; Gulari, Erdogan; Kim, Jinsang (2008). "Sensitive and selective label-free DNA detection by conjugated polymer-based microarrays and intercalating dye". Chemistry of Materials. 20: 2848–2850. doi:10.1021/cm800333r.

- Dillow, Clay (2010-06-07). "Laser Sensor Can See Explosives' Vapor Trails Even at Extremely Low Concentrations". Popular Science. Bonnier Corporation. Retrieved 2011-03-28.

- Hughes, E.D.; Le Fevre, C.G.; Le Fevre, R.J.W. (1937). "35. The structure of some derivatives of fluorene and fluorenone". Journal of the Chemical Society, Transactions: 202–207. doi:10.1039/JR9370000202.

- Burns, D.M.; Iball, John (1954). "Molecular structure of fluorene". Nature: 635. doi:10.1038/173635a0.

- Kuehni, Rolf G. (2005). "Sources of Color". Color: an introduction to practice and principles (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 047166006X, 9780471660064.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help) - ^ Leclerc, Mario (2001). "Polyfluorenes: Twenty Years of Progress". J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 39: 2867–2873. doi:10.1002/pola.1266.

- ^ Cho, Nam Sung; Hwang, Do-Hoon; Lee, Jeong-Ik; Jung, Byung-Jun; Shim, Hong-Ku (2002). "Synthesis and color tuning of new fluorene-based copolymers". Macromolecules. 35: 1224–1228. doi:10.1021/ma011155.

- ^ Moo-Jin, Park (2006). "Synthesis and light-emitting properties of new polyfluorene copolymers containing a triphenylamine based hydrazone comonomer". Current Applied Physics. 6: 752–755. doi:10.1016/j.cap.2005.04.033.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Do-Hoon, Hwang (2004). "Conjugated Polymers Based on Phenothiazine and Fluorene in Light-Emitting Diodes and Field Effect Transistors". Chemical Matter. 7. doi:10.1021/cm035264+.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - Bliznyuk, V. N. (November 6, 1998). "Electrical and Photoinduced Degradation of Polyfluorene Based Films and Light-Emitting Devices". Macromolecules. 32: 361–369. doi:10.1021/ma9808979.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Tzenka, Miteva (2001). "Improving the Performance of Polyfluorene-Based Organic Light-Emitting Diodes via End-capping". Adanced Materials. 8: 565–570. doi:10.1002/1521-4095(200104)13:8<565::AID-ADMA565>3.0.CO;2-W.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Xin, Yu; Wen, Gui-An; Zeng, Wen-Jing; Zhao, Lei; Zhu, Xing-Rong; Fan, Qu-Li; Feng, Jia-Chun; Wang, Lian-Hui; Wei, Wei; Peng, Bo; Cao, Yong; Huang, Wei (2005). "Hyperbranched oxadiazole-containing polyfluorenes: Toward stable blue light PLEDs". Macromolecules. 38: 6755–6758. doi:10.1021/ma050833f.

- Lupton, J.M.; Craig, M.R.; Meijer, E.W. (2002). "On-chain defect emission in electroluminescent polyfluorenes". Applied Physics Letters. 80 (24): 4489–4491. doi:10.1063/1.1486482.

- ^ Lee, Jeong-Ik; Klaerner, Gerrit; Davey, Mark H.; Miller (1999). "Color tuning in polyfluorenes by copolymerization with low bandgap comonomers". Synthetic Metals. 102: 1087–1088. doi:10.1016/S0379-6779(98)01364-2.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|first 4=ignored (|first4=suggested) (help) - ^ Hou, Qiong; Xu, Xin; Guo, Ting; Zeng, Xianghua; Luo, Suilian; Yang, Liting (2010). "Synthesis and photovoltaic properties of fluorene-based copolymers with narrow band-gap units on the side chain". European Polymer Journal. 46: 2365–2371. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2010.09.015.

- Fukuda, Masahiko; Sawada, Keiji; Yoshino, Katsumi (1993). "Synthesis of fusible and soluble conducting polyfluorene derivatives and their characteristics". Journal of Polymer Science: Part A. 31: 2465–2471. doi:10.1002/pola.1993.080311006.

- Fukuda, Masahiko; Sawada, Keiji; Yoshino, Katsumi (1989). "Fusible conducting poly(9-alkylfluorene) and poly(9,9-dialkylfluorene) and their characteristics". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 28 (8): L1433 – L1435. doi:10.1143/JJAP.28.L1433.

- Ranger, Maxime; Rondeau, Dany; Leclerc, Mario (1997). "New well-defined poly(2,7-fluorene) derivatives: photoluminescence and base doping". Macromolecules. 30: 7686–7691. doi:10.1021/ma970920a.

- Lin, Ying; Ye, Teng-Ling; Ma, Dong-Ge; Chen, Zhi-Kuan; Dai, Yan-Feng; Li, Yong-Xi (2010). "Blue-light emitting polyfluorene functionalized with triphenylamine and cyanophenylfluorene bipolar side chains". Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 48: 5930–5937. doi:10.1002/pola.24406.

- Cho, H.N.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, C.Y.; Song, N.W.; Kim, D. (1999). "Stastical copolymers for blue-light-emitting diodes". Macromolecules. 32: 1476–1481. doi:10.1021/ma981340w.

- Stefan, Mihaela C.; Javier, Anna E.; Osaka, Itaru; McCullough, Richard D. (2009). "Grignard metathesis method (GRIM): toward a universal method for the synthesis of conjugated polymers". Macromolecules. 42: 30–32. doi:10.1021/ma8020823.

- Lee, Kangwon; Kim, Hyong-Jun; Cho, Jae-Cheol; Kim, Jinsang (2007). "Chemically and Photochemically Stable Conjugated Poly(oxadiazole) Derivatives: A Comparison with Polythiophenes and Poly(p-phenyleneethynylenes)". Macromolecules. 40: 6457–6463. doi:10.1021/ma0712448.

- ^ Dennler, Gilles; Scharber, Markus C.; Brabec, Christoph J. (2009). "Polymer-Fullerene Bulk-Heterojunction Solar Cells". Advanced Materials. 21: 1–16. doi:10.1002/adma.200801283.

- ^ Huang, Fei; Chen, Kung-Shih; Yip, Hin-Lap; Hau, Steven K.; Acton, Orb; Zhang, Yong; Luo, Jingdong; Jen, Alex K.-Y. (2009). "Development of new conjugated polymers with donor-pi-bridge-acceptor side chains for high performance solar cells". Jounral of the American Chemical Society. 131: 13886–13887. doi:10.1021/ja9066139.

- Brabec, Christoph; Gowrisanker, Srinivas; Halls, Jonathan; Laird, Darin; Jia, Shijun; Williams, Shawn (2010). "Polymer-fullerene bulk-heterojunction solar cells". Advanced Materials. 22: 3839–3856. doi:10.1002/adma.200903697.

- McNeill, Christopher; Greenham, Neil (2009). "Conjugated polymer blends for optoelectronics". Advanced Materials. 21: 3840–3850. doi:10.1002/adma.200900783.

- Veenstra, Sjoerd; Loos, Joachim; Kroon, Jan (2007). "Nanoscale structure of solar cells based on pure conjugated polymer blends". Progress in Photovoltaics: Research and Applications. 15: 727–740. doi:10.1002/pip.796.

Further reading

- Barford, William (2005). Electronic and Optical Properties of Conjugated Polymers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198526806.

- Hamilton, Michael (2005). "Polyfluorene-based organic field-effect transistors". Thesis dissertation. ISBN 0542364948.

- Hong, Meng; Li, Zhigang (2007). Organic Light-emitting Materials and Devices. CRC Press. ISBN 9781574445749.

- Lee, Shu-Jen (2004). "Organic Polymer Light-emitting Devices: Optical Modeling, Engineering and Evaluation of Opto-electronic Properties". Thesis dissertation. ISBN 9780496090549.