This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Malljaja (talk | contribs) at 20:23, 11 July 2011 (→Ancestry: rm "Rothschild"—its history doesn't seem to bear this out + the name of the alleged sire was "Frankenberger"). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 20:23, 11 July 2011 by Malljaja (talk | contribs) (→Ancestry: rm "Rothschild"—its history doesn't seem to bear this out + the name of the alleged sire was "Frankenberger")(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Hitler" redirects here. For other uses, see Hitler (disambiguation).

| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (March 2011) |

| Adolf Hitler | |

|---|---|

Hitler in 1937 Hitler in 1937 | |

| Führer of Germany | |

| In office 2 August 1934 – 30 April 1945 | |

| Chancellor | Himself |

| Preceded by | Paul von Hindenburg (as President) |

| Succeeded by | Karl Dönitz (as President) |

| Chancellor of Germany | |

| In office 30 January 1933 – 30 April 1945 | |

| President | Paul von Hindenburg Himself (Führer) |

| Deputy | Franz von Papen Vacant |

| Preceded by | Kurt von Schleicher |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Goebbels |

| Personal details | |

| Born | (1889-04-20)20 April 1889 Braunau am Inn, Austria–Hungary |

| Died | 30 April 1945(1945-04-30) (aged 56) Berlin, Germany |

| Cause of death | Suicide |

| Nationality | Austrian citizen until 7 April 1925 German citizen after 25 February 1932 |

| Political party | National Socialist German Workers' Party (1921–1945) |

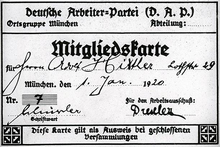

| Other political affiliations | German Workers' Party (1920–1921) |

| Spouse(s) | Eva Braun (29–30 April 1945) |

| Occupation | Politician, soldier, artist, writer |

| Awards | Iron Cross First Class Wound Badge |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1914–1918 |

| Rank | Gefreiter |

| Unit | 16th Bavarian Reserve Regiment |

| Battles/wars | World War I |

Adolf Hitler (pronounced Template:IPA-de; 20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician and the leader of the National Socialist German Workers Party (Template:Lang-de, abbreviated NSDAP, commonly known as the Nazi Party). He was Chancellor of Germany from 1933 to 1945, and head of state (as Führer und Reichskanzler) from 1934 to 1945. Hitler is most well known for his central leadership role in the rise of fascism in Europe, World War II and the Holocaust.

A decorated veteran of World War I, Hitler joined the precursor of the Nazi Party (DAP) in 1919, and became leader of NSDAP in 1921. He attempted a coup d'état, known as the Beer Hall Putsch at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall in Munich in 1923. The failed coup resulted in Hitler's imprisonment, during which time he wrote his memoir, Mein Kampf (in English "My Struggle"). After his release in 1924, he gained support by promoting Pan-Germanism, antisemitism and anti-communism with charismatic oratory and propaganda. He was appointed chancellor in 1933, and transformed the Weimar Republic into the Third Reich, a single-party dictatorship based on the totalitarian and autocratic ideology of Nazism.

Hitler's avowed aim was to establish a New Order of absolute Nazi German hegemony in continental Europe. His foreign and domestic policies had the goal of seizing Lebensraum ("living space") for the Aryan people. This included the rearmament of Germany, resulting in the invasion of Poland by the Wehrmacht in 1939, leading to the outbreak of World War II in Europe.

Under Hitler's leadership, German forces and their European allies at one point occupied most of Europe and North Africa, reversed in 1944 when the Allied armies freed German-occupied Europe. Hitler's reign resulted in the systematic murder of as many as 17 million civilians, including an estimated six million Jews targeted in the Holocaust and between 500,000 and 1,500,000 Roma.

In the final days of the war, during the Battle of Berlin in 1945, Hitler married his long-time mistress, Eva Braun. To avoid capture by Soviet forces, the two committed suicide less than two days later on 30 April 1945 and their corpses were burned.

Early years

Ancestry

Hitler's father, Alois Hitler, was an illegitimate child of Maria Anna Schicklgruber. Therefore, the name of Alois' father was not listed on Alois' birth certificate, and he bore his mother's surname. In 1842, Johann Georg Hiedler married Maria, and in 1876 Alois testified before a notary and three witnesses that Johann was his father. Despite his testimony, the question of Alois' paternity remained unresolved. Hans Frank claimed—after receiving a extortionary letter from Hitler's nephew William Patrick Hitler threatening to reveal embarrassing information about Hitler's family tree—to have uncovered letters revealing that Alois' mother was employed as a housekeeper for a Jewish family in Graz and that the family's 19-year-old son, Leopold Frankenberger, had fathered Alois. However, Frank's claim remained unsupported, and Frank himself did not believe that Hitler had Jewish ancestry, and although claims of Alois' Jewish father were widely believed to be true in the 1950s, these were doubted by historians in the 1990s. Ian Kershaw dismissed the Frankenberger story as a "smear" by Hitler's enemies, noting that all Jews had been expelled from Graz in the 15th century and were not allowed to return until after Alois' birth.

At age 39, Alois assumed the surname Hitler, variously spelled also as Hiedler, Hüttler, or Huettler, and was probably regularized to its final spelling by a clerk. The origin of the name is either "one who lives in a hut" (Standard German Hütte), "shepherd" (Standard German hüten "to guard", English heed), or is from the Slavic word Hidlar and Hidlarcek.

Childhood

Adolf Hitler was born on 20 April 1889 at around 6:30 pm at the Gasthof zum Pommer, an inn in Ranshofen, a village annexed to the municipality of Braunau am Inn, Upper Austria in 1938. He was the fourth of six children to Alois Hitler and Klara Pölzl. All of Adolf's older siblings – Gustav, Ida, and Otto – died before reaching three years of age.

At the age of three, his family moved to Kapuzinerstrasse 5 in Passau, Germany. There, Hitler would acquire a Bavarian dialect of Austro-Bavarian rather than an Austrian dialect. In 1894, the family relocated to Leonding near Linz, and in June 1895, Alois retired to a small landholding at Hafeld near Lambach, where he tried his hand at farming and beekeeping. During this time, the young Hitler attended school in nearby Fischlham. As a child, he played "Cowboys and Indians" and, by his own account, became fixated on war after finding a picture book about the Franco-Prussian War among his father's belongings.

His father's farming efforts at Hafeld ended in failure, and in 1897 the family moved to Lambach. Hitler attended a Catholic school in an 11th-century Benedictine cloister, the walls of which bore engravings and crests that contained the symbol of the swastika. In Lambach the eight-year-old Hitler also sang in the church choir, took singing lessons, and even entertained thoughts of one day becoming a priest. In 1898, the family returned permanently to Leonding.

On 2 February 1900 Hitler's younger brother, Edmund, died of measles, deeply affecting Hitler, whose character changed from being confident and outgoing and an excellent student, to a morose, detached, and sullen boy who constantly fought his father and his teachers.

Hitler was attached to his mother, but he had a troubled relationship with his father, who frequently beat him, especially in the years after Alois' retirement and failed farming efforts. Alois was a Austrian customs official who wanted his son to follow in his footsteps, which caused much conflict between them. Ignoring his son's wishes to attend a classical high school and become an artist, in September 1900 his father sent Adolf to the Realschule in Linz, a technical high school of about 300 students. Hitler rebelled against this decision, and in Mein Kampf revealed that he failed his first year, hoping that once his father saw "what little progress I was making at the technical school he would let me devote myself to the happiness I dreamed of." Alois was unrelenting, however, and Hitler became even more bitter and rebellious.

German Nationalism became an obsession for Hitler, and a way to rebel against his father, who proudly served the Austrian government. Most residents living along the German-Austrian border considered themselves German-Austrians, whereas Hitler expressed loyalty only to Germany. In defiance of the Austrian monarchy, and his father who continually expressed loyalty to it, Hitler and his friends used the German greeting "Heil", and sang the German anthem "Deutschland Über Alles" instead of the Austrian Imperial anthem.

After Alois' sudden death on 3 January 1903, Hitler's behaviour at the technical school became even more disruptive, and he was asked to leave in 1904. He enrolled at the Realschule in Steyr in September 1904, but upon completing his second year, he and his friends went out for a night of celebration and drinking. While drunk, Hitler tore up his school certificate and used its pieces as toilet paper. The stained certificate was brought to the attention of the school's principal who "... gave him such a dressing-down that the boy was reduced to shivering jelly. It was probably the most painful and humiliating experience of his life." Hitler was expelled, never to return to school again.

Aged 15, Hitler took part in his First Communion on Whitsunday, 22 May 1904, at the Linz Cathedral. His sponsor was Emanuel Lugert, a friend of his late father.

Early adulthood in Vienna and Munich

From 1905, Hitler lived a bohemian life in Vienna with financial support from orphan's benefits and his mother. He was rejected twice by the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna (1907–1908), because of his "unfitness for painting", and was recommended to study architecture. Following this recommendation, he intended to pursue architectural studies, yet he lacked the academic credentials required for architecture school:

In a few days I myself knew that I should some day become an architect. To be sure, it was an incredibly hard road; for the studies I had neglected out of spite at the Realschule were sorely needed. One could not attend the Academy's architectural school without having attended the building school at the Technic, and the latter required a high-school degree. I had none of all this. The fulfillment of my artistic dream seemed physically impossible.

On 21 December 1907, Hitler's mother died of breast cancer at age 47. Ordered by a court in Linz, Hitler gave his share of the orphan's benefits to his sister Paula. At the age of 21, he inherited money from an aunt. He struggled as a painter in Vienna, copying scenes from postcards and selling his paintings to merchants and tourists. After being rejected a second time by the Academy of Arts, Hitler ran out of money. In 1909, he lived in a shelter for the homeless, and by 1910, he had settled into a house for poor working men on Meldemannstraße. Another resident of the shelter, Reinhold Hanisch, sold Hitler's paintings until the two men had a bitter falling-out.

Hitler stated that he first became an antisemite in Vienna, which had a large Jewish community, including Orthodox Jews who had had fled the pogroms in Russia. According to childhood friend August Kubizek, Hitler was a "confirmed antisemite" before he left Linz. However Kubizek’s reliability is questionable, and his statement has not been confirmed by other sources. Brigitte Hamann wrote that “of all those early witnesses who can be taken seriously Kubizek is the only one to portray young Hitler as an anti-Semite and precisely in this respect he is not trustworthy.” Vienna at that time was a hotbed of traditional religious prejudice and 19th century racism. Hitler may have been influenced by the occult writings of the antisemite Lanz von Liebenfels in his magazine Ostara; he probably read the publication, although it is uncertain to what degree he was influenced by von Liebenfels's writings.

There were very few Jews in Linz. In the course of centuries the Jews who lived there had become Europeanised in external appearance and were so much like other human beings that I even looked upon them as Germans. The reason why I did not then perceive the absurdity of such an illusion was that the only external mark which I recognized as distinguishing them from us was the practice of their strange religion. As I thought that they were persecuted on account of their faith my aversion to hearing remarks against them grew almost into a feeling of abhorrence. I did not in the least suspect that there could be such a thing as a systematic antisemitism. Once, when passing through the inner City, I suddenly encountered a phenomenon in a long caftan and wearing black side-locks. My first thought was: Is this a Jew? They certainly did not have this appearance in Linz. I carefully watched the man stealthily and cautiously but the longer I gazed at the strange countenance and examined it feature by feature, the more the question shaped itself in my brain: Is this a German?

However, at the time Hitler apparently did not act on his views. He was a frequent dinner guest in a wealthy Jewish house, and he interacted well with Jewish merchants who tried to sell his paintings.

Martin Luther's On the Jews and Their Lies may have also shaped Hitler's views. In Mein Kampf, he refers to Martin Luther as a great warrior, a true statesman, and a great reformer, alongside Richard Wagner and Frederick the Great. Wilhelm Röpke, writing after the Holocaust, concluded that "without any question, Lutheranism influenced the political, spiritual and social history of Germany in a way that, after careful consideration of everything, can be described only as fateful."

Hitler claimed that Jews were enemies of the so-called Aryan race, and held them responsible for Austria's crisis. He also regarded some socialist and Bolshevist organisations as Jewish movements, thus merging his antisemitism with anti-Marxism. Later, blaming Germany's military defeat in World War I on the 1918 revolutions, he considered Jews the culprits of Imperial Germany's downfall and subsequent economic problems.

Hitler received the final part of his father's estate in May 1913 and moved to Munich. He wrote in Mein Kampf that he had always longed to live in a "real" German city. In Munich, he further pursued his interest in architecture and the writings of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. Moving to Munich also helped him avoid military service in Austria, but the Munich police in cooperation with the Austrian authorities eventually arrested him for dodging the draft. After a physical exam and a contrite plea, he was deemed unfit for service and allowed to return to Munich. However, when Germany entered World War I in August 1914, he successfully petitioned King Ludwig III of Bavaria for permission to serve in a Bavarian regiment, and enlisted in the Bavarian army.

World War I

Main article: Military career of Adolf Hitler

Hitler served as a runner on the Western Front in France and Belgium in the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 16. He experienced major combat, including the First Battle of Ypres, the Battle of the Somme, the Battle of Arras and the Battle of Passchendaele.

Hitler was twice decorated for bravery, receiving the Iron Cross, Second Class, in 1914 and Iron Cross, First Class, in 1918. Hitler's First Class Iron Cross was recommended by Hugo Gutmann, and although the latter decoration was rarely awarded to a Gefreiter, it may be explained by Hitler's post at regimental headquarters where he had more frequent interactions with senior officers than other soldiers of similar rank. The regimental staff, however, thought Hitler lacked leadership skills, and he was never promoted.

While serving at regimental headquarters Hitler pursued his artwork, drawing cartoons and instructions for an army newspaper. In 1916, he was wounded either in the groin area or the left thigh during the Battle of the Somme, but returned to the front in March 1917. He received the Wound Badge later that year.

On 15 October 1918, Hitler was temporarily blinded by a mustard gas attack, but it has also been suggested that he suffered from conversion disorder, then known as "hysteria". Some scholars, notably Lucy Dawidowicz, argue that Hitler's intention to exterminate Europe's Jews was fully formed at this time.

Hitler described the war as "the greatest of all experiences" and he was praised by his commanding officers for his bravery. The experience made Hitler a passionate German patriot, and he was shocked by Germany's capitulation in November 1918. Like many other German nationalists, Hitler believed in the Dolchstoßlegende (Stab-in-the-back legend), which claimed that the army, "undefeated in the field," had been "stabbed in the back" by civilian leaders and Marxists back on the home front, later dubbed the November Criminals.

The Treaty of Versailles, citing Germany's responsibility for the war, stipulated that Germany relinquish several of its territories, demilitarisation of the Rhineland, and imposed economic sanctions and levied reparations on the country. Many Germans perceived the treaty, especially Article 231 on the German responsibility for the war, as a humiliation, and its economic effects on the social and political conditions in Germany were later exploited by Hitler. He and his political allies used the signing of the treaty by the November Criminals as a reason to build up Germany.

Entry into politics

Main article: Adolf Hitler's political viewsAfter World War I, Hitler remained in the army and returned to Munich, where he attended the funeral march for the murdered Bavarian prime minister Kurt Eisner. After the suppression of the Bavarian Soviet Republic, he took part in "national thinking" courses organized by the Education and Propaganda Department of the Bavarian Reichswehr under Captain Karl Mayr.

In July 1919, Hitler was appointed Verbindungsmann (intelligence agent) of an Aufklärungskommando (reconnaissance commando) of the Reichswehr, both to influence other soldiers and to infiltrate the German Workers' Party (DAP). While he studied the activities of the DAP, Hitler became impressed with founder Anton Drexler's antisemitic, nationalist, anti-capitalist and anti-Marxist ideas. Drexler favoured a strong active government, a "non-Jewish" version of socialism and solidarity among all members of society. Drexler was impressed with Hitler's oratory skills and invited him to join the DAP, which Hitler accepted on 12 September 1919, becoming its 55th member.

At the DAP, Hitler met Dietrich Eckart, one of its early founders and member of the occult Thule Society. Eckart became Hitler's mentor, exchanging ideas with him, teaching him how to dress and speak, and introducing him to a wide range of people. Hitler thanked Eckart and paid tribute to him in the second volume of Mein Kampf. To increase the party's appeal, the party changed its name to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers Party; NSDAP).

Hitler was discharged from the army in March 1920 and with his former superiors' encouragement began participating full time in the party's activities. By early 1921, Hitler had become highly effective at speaking in front of large crowds. In February, Hitler spoke to a crowd of nearly six thousand in Munich. To publicize the meeting, two truckloads of party supporters drove around waving swastikas and throwing leaflets. Hitler soon gained notoriety for his rowdy, polemic speeches against the Treaty of Versailles, rival politicians, and especially directed against against Marxists and Jews.

The NSDAP was centred in Munich, a hotbed of German nationalists, including Army officers determined to crush Marxism and undermine the Weimar Republic. Gradually they noticed Hitler and his growing movement as a suitable vehicle for their goals.

While Hitler was on a trip to Berlin in the summer of 1921, there was a mutiny among the DAP leadership in Munich, notably within the executive committee whose members considered Hitler to be too overbearing. Hitler rushed back to Munich and as a political move tendered his resignation from the party on 11 July 1921. When they realized that Hitler's resignation would mean the end of the party, Hitler announced he would only return on the condition that he replace Drexler as party chairman. Drexler and other committee members held out at first, and an anonymous advertisement appeared in a Munich newspaper entitled Adolf Hitler: Is he a traitor?, focusing on Hitler's quest for power. Hitler responded to its publication by suing for libel and later won a small settlement.

The NSDAP executive committee eventually backed down, and Hitler's demands were put to a vote in which his received 543 votes in his support with only one nay vote. At the next gathering on 29 July 1921, Hitler was introduced as Führer of the NSDAP, marking the first time this title was publicly used.

Hitler's vitriolic beer hall speeches began attracting regular audiences. Early followers included Rudolf Hess, the former air force pilot Hermann Göring, and the army captain Ernst Röhm. The latter became head of the Nazis' paramilitary organization the Sturmabteilung (SA, "Storm Division"), which protected meetings and frequently attacked political opponents. Hitler also attracted some independent groups, such as the Nuremberg-based Deutsche Werkgemeinschaft, led by Julius Streicher, who became Gauleiter of Franconia. A critical influence on his thinking at this period was the Aufbau Vereinigung, a conspiratorial group formed of White Russian exiles and early National Socialists. The group introduced him to the idea of a Jewish conspiracy, linking international finance with Bolshevism, with funds channelled from wealthy industrialists like Henry Ford. Hitler also attracted the attention of local business interests, was accepted into influential circles of Munich society, and became associated with wartime General Erich Ludendorff during this time.

Beer Hall Putsch

Main article: Beer Hall PutschEncouraged by his new support, Hitler recruited Ludendorff for an attempted coup known as the "Beer Hall Putsch" (also known as the "Hitler Putsch" or "Munich Putsch"). The Nazi Party had used Italy's fascists as an example for its appearance and policies, and in 1923, Hitler wanted to emulate Benito Mussolini's "March on Rome" by staging his own "Campaign in Berlin". Hitler and Ludendorff obtained the clandestine support of Gustav von Kahr, Bavaria's de facto ruler, along with leading figures in the Reichswehr and the police. Ludendorff, Hitler and the heads of the Bavarian police and military had the goal of forming a new government.

On 8 November 1923, Hitler and the SA stormed a public meeting headed by Kahr in the Bürgerbräukeller, a large beer hall in Munich. Hitler announced that he had set up a new government with Ludendorff and demanded, at gunpoint, the support of Kahr and the local military establishment for the destruction of the Berlin government. Kahr withdrew his support and fled to join the opposition to Hitler. The next day, Hitler and his followers marched from the beer hall to the Bavarian War Ministry to overthrow the Bavarian government on their "March on Berlin", but the police dispersed them. Sixteen NSDAP members were killed in the failed coup.

Hitler fled to the home of Ernst Hanfstaengl where he contemplated suicide, but Hanfstaengl's wife Helene talked him out of it. He was soon arrested for high treason and tried before the special People's Court in Munich, and Alfred Rosenberg became temporary leader of the NSDAP. During his trial, Hitler was given almost unlimited time to speak, and his popularity soared as he voiced nationalistic sentiments in his defence speech. His trial began on 26 February 1924 and on 1 April 1924 Hitler was sentenced to five years' imprisonment at Landsberg Prison. Hitler received friendly treatment from the guards and received a lot of mail from supporters. The Bavarian Supreme Court soon issued a pardon and he was released from jail on 20 December 1924, against the state prosecutor's objections. Including time on remand, Hitler had been imprisoned for just over one year for the attempted coup.

Mein Kampf

While at Landsberg, he dictated most of the first volume of Mein Kampf (My Struggle, originally entitled Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity, and Cowardice) to his deputy Rudolf Hess. The book, dedicated to Thule Society member Dietrich Eckart, was an autobiography and an exposition of his ideology. Mein Kampf was influenced by The Passing of the Great Race by Madison Grant, which Hitler called "my Bible." Mein Kampf was published in two volumes in 1925 and 1926, selling about 240,000 copies between 1925 and 1934. By the end of the war, about 10 million copies had been sold or distributed. The copyright of Mein Kampf in Europe is claimed by the Free State of Bavaria and will end on 31 December 2015. In Germany, only heavily commented editions of Mein Kampf are available solely for academic studies.

Rebuilding of the NSDAP

At the time of Hitler's release from prison, politics in Germany had become less combative and the economy had improved. This limited Hitler's opportunities for political agitation. As a result of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, the NSDAP and its affiliated organisations were banned in Bavaria. However, Hitler—now claiming to seek political power only through the democratic process—succeeded in persuading Heinrich Held, Prime Minister of Bavaria, to lift the ban. The ban on the NSDAP was lifted on 16 February 1925, but Hitler was barred from public speaking. To be able to advance his political ambitions in spite of the ban, Hitler appointed Gregor Strasser along with his brother Otto and Joseph Goebbels to organize and grow the NSDAP in northern Germany. Strasser, however, steered a more independent political course, emphasizing the socialist element in the party's programme. The Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Gauleiter Nord-West thus became an internal opposition, threatening Hitler's authority, but its influence was strongly curtailed at the Bamberg Conference in 1926.

Hitler went on to establish a more autocratic rule of the NSDAP and asserted the Führerprinzip ("Leader principle"). Offices in the party were not determined by elections, but rather filled by appointment by higher ranks who demanded unquestioning obedience from the lower ranks they had appointed. This reflected Hitler's view that all power and authority devolved from the top down.

A key element of Hitler's appeal was his ability to evoke a sense of violated national pride as a result of the Treaty of Versailles. Many Germans strongly resented the terms of the treaty, especially the economic burden of having to pay large reparations to other countries affected by World War I. Nonetheless, attempts by Hitler to win popular support by blaming the demands and assertions in the treaty on "international Jewry" were largely unsuccessful with the electorate. Therefore, Hitler and his party began employing more subtle propaganda methods, combining antisemitism with an attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and the parties supporting it.

Having failed in overthrowing the republic and gaining power by a coup, Hitler changed tactics and pursued a strategy of formally adhering to the rules of the Weimar Republic until he had gained political power through regular elections. His vision was to then use the institutions of the Weimar Republic to destroy it and establish himself as autocratic leader. Some party members, especially in the paramilitary SA, opposed this strategy; for example, Röhm and others ridiculed Hitler as "Adolphe Legalité".

Rise to power

Main article: Adolf Hitler's rise to power| Date | Votes | Percentage of Votes |

Seats in Reichstag |

Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Template:DtshMay 1924 | 1,918,300 | 6.5 | 32 | Hitler in prison |

| Template:DtshDecember 1924 | 907,300 | 3.0 | 14 | Hitler is released from prison |

| Template:DtshMay 1928 | 810,100 | 2.6 | 12 | |

| Template:DtshSeptember 1930 | 6,409,600 | 18.3 | 107 | After the financial crisis |

| Template:DtshJuly 1932 | 13,745,800 | 37.4 | 230 | After Hitler was candidate for presidency |

| Template:DtshNovember 1932 | 11,737,000 | 33.1 | 196 | |

| Template:DtshMarch 1933 | 17,277,000 | 43.9 | 288 | During Hitler's term as Chancellor of Germany |

Brüning Administration

Hitler's political turning point came with the Great Depression in Germany in 1930. The Weimar Republic had difficulties taking firm roots in German society and faced strong challenges from right- and left-wing extremists. The moderate political parties committed to the democratic, parliamentary republic were increasingly unable to stem the tide of extremism. In early elections in September 1930, the moderates lost their majority, leading to the break-up of a grand coalition and its replacement by a minority cabinet. Its leader, chancellor Heinrich Brüning of the Centre Party, governed through emergency decrees. Tolerated by most parties, governance by decree would become the new norm and paved the way for authoritarian forms of government. Notably the NSDAP rose from relative obscurity to win 18.3% of the vote and 107 parliamentary seats in the 1930 election, rising from the ninth-smallest party in the chamber to the second largest.

The increasing political clout of Hitler was felt at the trial of two Reichswehr officers, Leutnants Richard Scheringer and Hans Ludin, in the autumn of 1930. Both were charged with membership of the NSDAP, which at that time was illegal for Reichswehr personnel. The prosecution argued that the NSDAP was a dangerous extremist party, prompting defence lawyer Hans Frank to call on Hitler to testify at the court. During his testimony on 25 September 1930, Hitler stated that his party was aiming to come to power solely through democratic elections and that the NSDAP was a friend of the Reichswehr. Hitler's testimony won him many supporters in the officer corps.

Brüning's budgetary and financial austerity measures brought little economic improvement and were extremely unpopular. Hitler exploited this weakness by targeting his political messages specifically to the segments of the population that had been hard hit by the inflation of the 1920s and the unemployment of the Depression, such as farmers, war veterans, and the middle class.

Hitler formally renounced his Austrian citizenship on 7 April 1925, but at the time did not acquire German citizenship. For almost seven years Hitler was stateless, so he was unable to run for public office and even faced the risk of deportation. Therefore, on 25 February 1932, the interior minister of Brunswick who was a member of the NSDAP appointed Hitler as administrator for the state's delegation to the Reichsrat in Berlin, making Hitler a citizen of Brunswick, and thus of Germany as well.

In 1932, Hitler ran against the aging President Paul von Hindenburg in the presidential elections. The viability of his candidacy was underscored by a 27 January 1932 speech to the Industry Club in Düsseldorf, which won him support from a broad swath of Germany's most powerful industrialists. However, Hindenburg had broad support of various nationalist, monarchist, Catholic, and republican parties and even some social democrats. Hitler used the campaign slogan "Hitler über Deutschland" (Hitler over Germany), a reference to his political ambitions, and to his campaigning by aircraft. Hitler came in second in both rounds of the election, garnering more than 35% of the vote in the final election. Although he lost to Hindenburg, this election established Hitler as a credible force in German politics.

In September 1931, Hitler's niece Geli Raubal committed suicide with Hitler's gun in his Munich apartment. Geli was believed to be in a romantic relationship with Hitler, and it is believed that her death was a source of deep, lasting pain for him.

Appointment as Chancellor

Because of the difficulties of forming a stable and effective government, Franz von Papen and Alfred Hugenberg, as well as a number of industrialists and businessmen, including Hjalmar Schacht and Fritz Thyssen wrote to Hindenburg, urging him to appoint Hitler as leader of a government "independent from parliamentary parties" which could turn into a movement that would "enrapture millions of people."

President Hindenburg eventually and reluctantly agreed to appoint Hitler chancellor of a coalition government formed by the NSDAP and DNVP. The influence of the NSDAP in parliament was initially limited by an alliance of conservative cabinet ministers, most notably by von Papen as Vice-Chancellor and by Hugenberg as Minister of the Economy. The only other NSDAP member besides Hitler, Wilhelm Frick, was given the relatively powerless interior ministry. However, as a concession to the NSDAP, Göring was named minister without portfolio. So, although von Papen intended to install Hitler merely as a figurehead, the NSDAP gained several key positions.

On 30 January 1933, Adolf Hitler was sworn in as Chancellor during a brief and simple ceremony in Hindenburg's office. Hitler's first speech as Chancellor took place on 10 February. The Nazis' seizure of power subsequently became known as the Machtergreifung or Machtübernahme.

Reichstag fire and March elections

As chancellor, Hitler worked against attempts by his political opponents to build a majority government. Because of the political stalemate, Hitler asked President Hindenburg to dissolve the Reichstag again, and elections were scheduled for early March. On 27 February 1933, the Reichstag building was set on fire, and since a Dutch independent communist was found in the burning building, a communist plot was blamed for the fire. The central government responded with the Reichstag Fire Decree of 28 February, which suspended basic rights, including habeas corpus. In particular, activities of the German Communist Party were suppressed, and communist party members were arrested, forced to flee, or murdered.

Besides political campaigning, the NSDAP used paramilitary violence and spread of anti-communist propaganda on the days preceding the election. On election day, 6 March 1933, the NSDAP increased its result to 43.9% of the vote, gaining the largest number of seats in parliament. However, Hitler's party failed to secure an absolute majority, thus again necessitating a coalition with the DNVP.

Day of Potsdam and the Enabling Act

On 21 March 1933, the new Reichstag was constituted with an opening ceremony held at Potsdam's garrison church. This Day of Potsdam was staged to demonstrate reconciliation and unity between the revolutionary Nazi movement and Old Prussia with its elites and perceived virtues. Hitler appeared in a tail coat and humbly greeted the aged President Hindenburg.

In the Nazis' quest for full political control and because they had failed to gain an absolute majority in the previous parliamentary election, Hitler's government brought the Ermächtigungsgesetz (Enabling Act) to a vote in the newly elected Reichstag. The aim of this move was to give Hitler's cabinet full legislative powers for a period of four years. Although such a bill was not unprecedented, this act was different since it allowed for deviations from the constitution. Since the bill required a ⅔ majority in order to pass, the government needed the support of other parties. The position of the Centre Party, the third largest party in the Reichstag, turned out to be decisive: under the leadership of Ludwig Kaas, the party decided to vote for the Enabling Act. It did so in return for the government's oral guarantees of the Church's liberty, the concordats signed by German states and the continued existence of the Centre Party.

On 23 March, the Reichstag assembled in a replacement building under extremely turbulent circumstances. Several SA men served as guards inside, while large groups outside the building shouted slogans and threats toward the arriving members of parliament. Kaas announced that the Centre Party would support the bill with "concerns put aside", while Social Democrat Otto Wels denounced the act in his speech. At the end of the day, all parties except Social Democrats voted in favour of the bill—the Communists, as well as several Social Democrats, were barred from attending the vote. The Enabling Act, along with the Reichstag Fire Decree, transformed Hitler's government into a de facto dictatorship.

Removal of remaining limits

At the risk of appearing to talk nonsense I tell you that the Nazi movement will go on for 1,000 years! ... Don't forget how people laughed at me 15 years ago when I declared that one day I would govern Germany. They laugh now, just as foolishly, when I declare that I shall remain in power!

— Adolf Hitler to a British correspondent in Berlin, June 1934

Having achieved full control over the legislative and executive branches of government, Hitler and his political allies embarked on systematic suppression of the remaining political opposition. After the dissolution of the Communist Party, the Social Democratic Party (SPD) was also banned and all its assets seized. The Steel Helmets were placed under Hitler's leadership with some autonomy as an auxiliary police force. In May 1933, stormtroopers demolished trade union offices in the country, and all unions vowed allegiance to Hitler. The Catholic Church was forced to support Hitler and its Centre Party dissolved. On 14 July, Hitler's Nazi Party was declared the only legal party in Germany.

In his next move, Hitler used the SA to pressure Hugenberg into resigning, and proceeded to politically isolate Vice-Chancellor von Papen. The demands of the SA for more political and military power caused much anxiety among military and political leaders, prompting Hitler to purge the SA's leadership, including Ernst Röhm, during the Night of the Long Knives. At the same time Gregor Strasser and former Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher fell also victim to the politically motivated murders.

On 2 August 1934, President von Hindenburg died. In contravention to the Weimar Constitution— calling for presidential elections—and following a law passed the previous day in anticipation of Hindenburg's imminent death, Hitler's cabinet declared the presidency vacant and transferred the powers of the head of state to Hitler as Führer und Reichskanzler (leader and chancellor). This removed the last legal remedy by which Hitler could be dismissed, and nearly all institutional checks and balances on his power. Hitler's move also violated the Enabling Act, which had barred tampering with the office of the presidency.

On 19 August, the merger of the presidency with the chancellorship was approved by a plebiscite with support from 84.6% of the electorate.

As head of state, Hitler now became Supreme Commander of the armed forces. The traditional loyalty oath of soldiers and sailors was altered to affirm loyalty directly to Hitler rather than to the office of commander-in-chief.

In 1938, in the wake of two scandals Hitler brought the armed forces under his direct control by forcing the resignation of his War Minister (formerly Defence Minister), Werner von Blomberg on evidence that Blomberg's new wife had a criminal past. Hitler and his allies also removed army commander Werner von Fritsch on suspicion of homosexuality. Hitler replaced the Ministry of War with the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (High Command of the Armed Forces, or OKW), headed by the pliant General Wilhelm Keitel. With Hitler having become Commander-in-Chief coupled with the post of supreme commander holding the powers of the presidential office, German newspapers announced, "Strongest concentration of powers in Führer's hands!"

Third Reich

Main article: Nazi GermanyHaving consolidated and concentrated his political powers, Hitler proceeded to suppress or eliminate his opposition by a process termed Gleichschaltung ("bringing into line"). He also tried to gain additional public support by vowing to reverse the effects of the Depression and the Versailles treaty.

Economy and culture

Hitler's rule led to very large expansions of industrial production and to civil improvement in Germany. These increased economic activities were enabled largely by debt flotation (refinancing long term debts into cheaper short term debts) and expansion of the military. For example, Hitler's reconstruction and rearmament were financed with currency manipulations by Hjalmar Schacht, including credits through the Mefo bills.

Nazi policies strongly encouraged women to bear children and stay at home. In a September 1934 speech to the National Socialist Women's Organization, Hitler argued that for the German woman her "world is her husband, her family, her children, and her home." The Cross of Honor of the German Mother was bestowed on women bearing four or more children. The unemployment rate fell substantially, mostly through arms production and women leaving the workforce.

Hitler oversaw one of the largest infrastructure-improvement campaigns in German history, leading to the construction of dams, autobahns, railroads, and other civil works. However, these programmes lowered the overall standard of living for those not previously affected by the chronic unemployment of the later Weimar Republic—wages were slightly reduced in pre–World War II years, while the cost of living was increased by 25%. Labourers and farmers, many of whom supporters of the NSDAP, however, saw an increase in their standard of living.

Hitler's government sponsored architecture on an immense scale, with Albert Speer becoming the first architect of the Reich, instrumental in implementing Hitler's classicist reinterpretation of German culture. In 1936, Hitler opened the summer Olympic games in Berlin. Hitler also made some contributions to the design of the Volkswagen Beetle and charged Ferdinand Porsche with its design and construction.

On 20 April 1939, a lavish celebration was held for Hitler's 50th birthday, featuring military parades, visits from foreign dignitaries, thousands of flaming torches and Nazi banners.

One question concerns the aspect of modernization in Hitler's economic policies. Historians such as David Schoenbaum and Henry Ashby Turner argue that Hitler's social and economic policies were modernization that had anti-modern goals. Others, including Rainer Zitelmann, have contended that Hitler had the deliberate strategy of pursuing a revolutionary modernization of German society.

Rearmament and new alliances

Main articles: Axis powers, Tripartite Pact, and German re-armament

On 3 February 1933, in a meeting with German military leaders, Hitler spoke of "conquest for Lebensraum in the East and its ruthless Germanisation" as his ultimate foreign policy objectives. In March 1933, a major statement by the State Secretary at the Auswärtiges Amt (Foreign Office), Prince Bernhard Wilhelm von Bülow, of German foreign policy aims was issued. It advocated Anschluss with Austria, the restoration of the frontiers of 1914, rejection of Part V of the Treaty of Versailles, the return of the former German colonies in Africa, and a German zone of influence in Eastern Europe. Hitler found the goals in Bülow's memo to be too modest.

In his "peace speeches" in the mid-1930s, Hitler stressed the peaceful goals of his policies and willingness to work within international agreements. At the first meeting of his Cabinet in 1933, however, Hitler prioritised military spending over unemployment relief. In October 1933, Hitler withdrew Germany from the League of Nations and the World Disarmament Conference, and his Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath stated that the French demand for sécurité was a principal stumbling block.

In March 1935, Hitler rejected Part V of the Versailles treaty by announcing that the German army would be expanded to 600,000 men (six times the number stipulated in the Treaty of Versailles), including development of an Air Force (Luftwaffe) and increasing the size of the Navy (Kriegsmarine). Although Britain, France, Italy and the League of Nations condemned these plans, no country took actions to stop them.

On 18 June 1935, the Anglo-German Naval Agreement (AGNA) was signed, allowing German tonnage to increase to 35% of that of the British navy. Hitler called the signing of the AGNA "the happiest day of his life" as he believed the agreement marked the beginning of the Anglo-German alliance he had predicted in Mein Kampf. France or Italy were not consulted before the signing, directly undermining the League of Nations and putting the Treaty of Versailles on the path towards irrelevance.

On 13 September 1935, Hitler ordered two civil servants, Dr. Bernhard Lösener and Franz Albrecht Medicus of the Interior Ministry to start drafting antisemitic laws for Hitler to bring to the floor of the Reichstag. On 15 September, Hitler presented two laws—known as the Nuremberg Laws—before the Reichstag. The laws banned marriage between non-Jewish and Jewish Germans and the employment of non-Jewish women under the age of 45 in Jewish households. The laws also deprived so-called "non-Aryans" of the benefits of German citizenship.

In March 1936, Hitler reoccupied the demilitarized zone in the Rhineland, thus again violating the Versailles treaty. In addition, Hitler sent troops to Spain to support General Franco after receiving an appeal for help from Franco in July 1936. At the same time, Hitler continued with his efforts to create an Anglo-German alliance.

In August 1936, in response to a growing economic crisis caused by his rearmament efforts, Hitler issued the "Four-Year Plan Memorandum", ordering Hermann Göring to carry out the Four Year Plan to have Germany ready for war within the next four years. Hitler's "Four-Year Plan Memorandum" laid out an imminent all-out struggle between "Judeo-Bolshevism" and German National Socialism, which in Hitler's view required a committed effort of rearmament regardless of the economic costs.

On 25 October 1936, Count Galeazzo Ciano foreign minister of Benito Mussolini's government declared an axis between Germany and Italy, and on 25 November, Germany signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Japan. Britain, China, Italy and Poland were also invited to join the Anti-Comintern Pact, but only Italy signed in 1937. By late 1937, Hitler had abandoned his dream of an Anglo-German alliance, blaming "inadequate" British leadership.

On 5 November 1937, Hitler held a secret meeting at the Reich Chancellery with his war and foreign ministers and military chiefs. As recorded in the Hossbach Memorandum, Hitler stated his intention of acquiring Lebensraum ("living space") for the German people, and ordered to make preparations for war in the east no later than 1943. Hitler further stated that the conference minutes were to be regarded as his "political testament" in the event of his death. Hitler was also recorded as saying that the crisis of the German economy had reached a point that a severe decline in living standards in Germany could only be stopped by a policy of military aggression and seizing Austria and Czechoslovakia. Moreover, Hitler urged for quick action before Britain and France obtained a permanent lead in the arms race.

In early 1938, Hitler asserted his control of the military-foreign policy apparatus through the Blomberg-Fritsch Affair and the abolition of the War Ministry and its replacement by the OKW. He also dismissed Neurath as Foreign Minister on 4 February 1938, and assumed the role and title of the Oberster Befehlshaber der Wehrmacht (supreme commander of the armed forces). It has been argued that from early 1938 onwards, Hitler was not carrying out a foreign policy that increased the risk of war, but that he was carrying out a foreign policy that had war as its ultimate aim.

The Holocaust

Main article: The Holocaust

One of Hitler's central and most controversial ideologies was the concept of so-called racial hygiene. It was based on the ideas of Arthur de Gobineau, eugenics, and social Darwinism. Hitler's eugenic policies initially targeted children with physical and developmental disabilities in a programme dubbed Action T4.

Hitler's idea of Lebensraum espoused in Mein Kampf, focused on acquiring new territory for German settlement in Eastern Europe. The Generalplan Ost ("General Plan for the East") provided that the population of occupied Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union was to be partially deported to West Siberia, used as slave labour and eventually murdered; the conquered territories were to be colonized by German or "Germanized" settlers.

Between 1939 and 1945, the SS, assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, systematically killed 11–14 million people, including about six million Jews representing two-thirds of the Jewish population in Europe. These killings took place, for example, in concentration camps, ghettos, and through mass executions. Many victims of the Holocaust were gassed to death, whereas others died of starvation or disease while working as slave labourers.

Hitler's policies also resulted in the systematic killings of Poles and Soviet prisoners of war, communists and other political opponents, homosexuals, Roma, the physically and mentally disabled, Jehovah's Witnesses, Adventists, and trade unionists. One of the biggest centres of mass-killing was the extermination camp complex of Auschwitz-Birkenau. Hitler never appeared to have visited the concentration camps and did not speak publicly about the killings.

The Holocaust (the "Endlösung der jüdischen Frage" or "Final Solution of the Jewish Question") was organised and executed by Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich. The records of the Wannsee Conference—held on 20 January 1942 and led by Reinhard Heydrich with fifteen senior Nazi officials (including Adolf Eichmann) participating—provide the clearest evidence of the systematic planning for the Holocaust. On 22 February, Hitler was recorded saying to his associates, "we shall regain our health only by eliminating the Jews".

Although no specific order from Hitler authorising the mass killings has surfaced, he approved the Einsatzgruppen, killing squads that followed the German army through Poland and Russia, and he was well informed about their activities. Evidence also suggests that in the fall of 1941, Himmler and Hitler decided to use gassing for the mass killings. During interrogations by Soviet intelligence officers declassified over fifty years later, Hitler's valet, Heinz Linge, and his military aide, Otto Gunsche, had stated that Hitler had a direct interest in the development of gas chambers."

World War II

Early diplomatic successes

Alliance with Japan

Main article: German–Japanese relations

In February 1938, upon advice from his newly appointed Foreign Minister, the strongly pro-Japanese Joachim von Ribbentrop, Hitler ended the Sino-German alliance with the Republic of China to enter instead into an alliance with the more modern and powerful Japan. Hitler announced German recognition of Manchukuo, the Japanese-occupied state in Manchuria, and renounced German claims to the former colonies in the Pacific held by Japan. Hitler also ordered an end to arms shipments to China, and recalled all German officers working with the Chinese Army. In retaliation, Chinese General Chiang Kai-shek cancelled all Sino-German economic agreements, depriving the Germans of Chinese raw materials such as tungsten and limiting the efforts of German rearmament.

Austria and Czechoslovakia

| This section may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article's talk page. (April 2010) |

On 12 March 1938, Hitler declared unification of Austria with Germany in the Anschluss. Hitler then turned his attention to the ethnic Germans population of Sudetenland districts of Czechoslovakia.

On 28–29 March 1938, Hitler held a series of secret meetings in Berlin with Konrad Henlein of the Sudeten Heimfront (Home Front), the largest of the ethnic German parties of the Sudetenland. Both men agreed that Henlein would demand increased autonomy for Sudeten Germans from the Czechoslovakian government, thus providing a pretext for German military action against Czechoslovakia. In April 1938, Henlein told the foreign minister of Hungary that "whatever the Czech government might offer, he would always raise still higher demands ... he wanted to sabotage an understanding by all means because this was the only method to blow up Czechoslovakia quickly". In private, Hitler considered the Sudeten issue unimportant; his real intention was a war of conquest against Czechoslovakia.

In April 1938, Hitler ordered the OKW to prepare for Fall Grün (Case Green), the codename for an invasion of Czechoslovakia. As a result of intense French and British diplomatic pressure, Czechoslovakian President Edvard Beneš unveiled on 5 September 1938, the "Fourth Plan" for constitutional reorganization of his country, which agreed to most of Henlein's demands for Sudeten autonomy. Henlein's Heimfront responded to Beneš' offer with a series of violent clashes with the Czechoslovakian police that led to the declaration of martial law in certain Sudeten districts.

In light of Germany's dependence on imported oil, and that a confrontation with Britain over the Czechoslovakian dispute could curtail Germany's oil supplies, Hitler called off Fall Grün, originally planned for 1 October 1938. On 29 September 1938, a one-day conference was held in Munich attended by Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier and Mussolini that led to the Munich Agreement, which gave in to Hitler's ostensible demands by handing over the Sudetenland districts to Germany.

Chamberlain was satisfied with the Munich conference, calling the outcome "peace for our time", while Hitler was angered about his missed opportunity for war in 1938. Hitler expressed his disappointment over the Munich Agreement in a speech on 9 October 1938 in Saarbrücken. In Hitler's view, the British-brokered peace, although favourable to ostensible German demands, was a diplomatic defeat for him, which spurred Hitler's intent of limiting British power to pave the way for the eastern expansion of Germany. However, as a result of the summit, Hitler was selected TIME magazine's Man of the Year for 1938.

In late 1938 and early 1939, the continuing economic crisis caused by the rearmament efforts forced Hitler to make major defence cuts. On 30 January 1939, Hitler made an "Export or die" speech, calling for a German economic offensive, to increase German foreign exchange holdings to pay for raw materials such as high-grade iron needed for military weapons.

"One thing I should like to say on this day which may be memorable for others as well for us Germans: In the course of my life I have very often been a prophet, and I have usually been ridiculed for it. During the time of my struggle for power it was in the first instance the Jewish race which only received my prophecies with laughter when I said I would one day take over the leadership of the State, and that of the whole nation, and that I would then among many other things settle the Jewish problem. Their laughter was uproarious, but I think that for some time now they have been laughing on the other side of the face. Today I will be once more the prophet. If the international Jewish financiers outside Europe should succeed in plunging the nations once more into a world war, then the result will not be the bolshevisation of the earth, and thus the victory of Jewry, but the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe!"

On 15 March 1939, in violation of the Munich accord and possibly as a result of the deepening economic crisis requiring additional assets, Hitler eventually ordered the Wehrmacht to invade Prague, and from Prague Castle proclaimed Bohemia and Moravia a German protectorate.

Start of World War II

As part of the anti-British course, it was deemed necessary by Hitler to have Poland either a satellite state or otherwise neutralized. Hitler believed this necessary both on strategic grounds as a way of securing the Reich's eastern flank and on economic grounds as a way of evading the effects of a British blockade. Initially, the German hope was to transform Poland into a satellite state, but by March 1939 the German demands had been rejected by the Poles three times, which led Hitler to decide upon the destruction of Poland as the main German foreign policy goal of 1939. On 3 April 1939, Hitler ordered the military to start preparing for Fall Weiss (Case White), the plan for a German invasion to be executed on 25 August 1939. In August 1939, Hitler spoke to his generals that his original plan for 1939 had to "... establish an acceptable relationship with Poland in order to fight against the West" but since the Poles would not co-operate in setting up an "acceptable relationship" (i.e. becoming a German satellite), he believed he had no choice other than wiping Poland off the map. The historian Gerhard Weinberg has argued since Hitler's audience comprised men who were all for the destruction of Poland (anti-Polish feelings were traditionally very strong in the German Army), but rather less happy about the prospect of war with Britain and France, if that was the price Germany had to pay for the destruction of Poland, it is quite likely that Hitler was speaking the truth on this occasion. In his private discussions with his officials in 1939, Hitler always described Britain as the main enemy that had to be defeated, and in his view, Poland's obliteration was the necessary prelude to that goal by securing the eastern flank and helpfully adding to Germany's Lebensraum. Hitler was much offended by the British "guarantee" of Polish independence issued on 31 March 1939, and told his associates that "I shall brew them a devil's drink". In a speech in Wilhelmshaven for the launch of the battleship Tirpitz on 1 April 1939, Hitler threatened to denounce the Anglo-German Naval Agreement if the British persisted with their "encirclement" policy as represented by the "guarantee" of Polish independence. As part of the new course, in a speech before the Reichstag on 28 April 1939, Adolf Hitler, complaining of British "encirclement" of Germany, renounced both the Anglo-German Naval Agreement and the German–Polish Non-Aggression Pact.

As a pretext for aggression against Poland, Hitler claimed the Free City of Danzig and the right for "extra-territorial" roads across the Polish Corridor which Germany had unwillingly ceded under the Versailles treaty. For Hitler, Danzig was just a pretext for aggression as the Sudetenland had been intended to be in 1938, and throughout 1939, while highlighting the Danzig issue as a grievance, the Germans always refused to engage in talks about the matter. A notable contradiction existed in Hitler's plans between the long-term anti-British course, whose major instruments such as a vastly expanded Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe would take several years to complete, and Hitler's immediate foreign policy in 1939, which was likely to provoke a general war by engaging in such actions as attacking Poland. Hitler's dilemma between his short-term and long-term goals was resolved by Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, who told Hitler that neither Britain nor France would honour their commitments to Poland, and any German–Polish war would accordingly be a limited regional war. Ribbentrop based his appraisal partly on an alleged statement made to him by the French Foreign Minister Georges Bonnet in December 1938 that France now recognized Eastern Europe as Germany's exclusive sphere of influence. In addition, Ribbentrop's status as the former Ambassador to London made him in Hitler's eyes the leading Nazi British expert, and as a result, Ribbentrop's advice that Britain would not honour her commitments to Poland carried much weight with Hitler. Ribbentrop only showed Hitler diplomatic cables that supported his analysis. In addition, the German Ambassador in London, Herbert von Dirksen, tended to send reports that supported Ribbentrop's analysis such as a dispatch in August 1939 that reported British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain knew "the social structure of Britain, even the conception of the British Empire, would not survive the chaos of even a victorious war", and so would back down. The extent that Hitler was influenced by Ribbentrop's advice can be seen in Hitler's orders to the German military on 21 August 1939 for a limited mobilization against Poland alone. Hitler chose late August as his date for Fall Weiss in order to limit disruption to German agricultural production caused by mobilization. The problems caused by the need to begin a campaign in Poland in late August or early September in order to have the campaign finished before the October rains arrived, and the need to have sufficient time to concentrate German troops on the Polish border left Hitler in a self-imposed situation in August 1939 where Soviet co-operation was absolutely crucial if he were to have a war that year.

The Munich agreement appeared to be sufficient to dispel most of the remaining hold which the "collective security" idea may have had in Soviet circles, and, on 23 August 1939, Joseph Stalin accepted Hitler's proposal to conclude a non-aggression pact (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact), whose secret protocols contained an agreement to partition Poland. A major historical debate about the reasons for Hitler's foreign policy choices in 1939 concerns whether a structural economic crisis drove Hitler into a "flight into war" as claimed by the Marxist historian Timothy Mason or whether Hitler's actions were more influenced by non-economic factors as claimed by the economic historian Richard Overy. Historians such as William Carr, Gerhard Weinberg and Ian Kershaw have argued that a non-economic reason for Hitler's rush to war was Hitler's morbid and obsessive fear of an early death, and hence his feeling that he did not have long to accomplish his work. In the last days of peace, Hitler oscillated between the determination to fight the Western powers if he had to, and various schemes intended to keep Britain out of the war, but in any case, Hitler was not to be deterred from his aim of invading Poland. Only very briefly, when news of the Anglo-Polish alliance being signed on 25 August 1939 in response to the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact (instead of the severing of ties between London and Warsaw predicted by Ribbentrop) together with news from Italy that Mussolini would not honour the Pact of Steel, caused Hitler to postpone the attack on Poland from 25 August to 1 September. Hitler chose to spend the last days of peace either trying to manoeuvre the British into neutrality through his offer of 25 August 1939 to "guarantee" the British Empire, or having Ribbentrop present a last-minute peace plan to Henderson with an impossibly short time limit for its acceptance as part of an effort to blame the war on the British and Poles. On 1 September 1939, Germany invaded western Poland. Britain and France declared war on Germany on 3 September but did not immediately act. Hitler was most unpleasantly surprised at receiving the British declaration of war on 3 September 1939, and turning to Ribbentrop angrily asked "Now what?" Ribbentrop had nothing to say other than that Robert Coulondre, the French Ambassador, would probably be by later that day to present the French declaration of war. Not long after this, on 17 September, Soviet forces invaded eastern Poland.

Poland never will rise again in the form of the Versailles treaty. That is guaranteed not only by Germany, but also ... Russia.

- – Adolf Hitler in a public speech in Danzig at the end of September 1939.

After the fall of Poland came a period journalists called the "Phoney War," or Sitzkrieg ("sitting war"). In part of north-western Poland annexed to Germany, Hitler instructed the two Gauleiters in charge of the area, namely Albert Forster and Arthur Greiser, to "Germanize" the area, and promised them "There would be no questions asked" about how this "Germanization" was to be accomplished. Hitler's orders were interpreted in very different ways by Forster and Greiser. Forster followed a policy of simply having the local Poles sign forms stating they had German blood with no documentation required, whereas Greiser carried out a brutal ethnic cleansing campaign of expelling the entire Polish population into the Government-General of Poland. When Greiser, seconded by Himmler, complained to Hitler that Forster was allowing thousands of Poles to be accepted as "racial" Germans and thus "contaminating" German "racial purity", and asked Hitler to order Forster to stop, Hitler merely told Himmler and Greiser to take up their difficulties with Forster, and not to involve him. Hitler's handling of the Forster–Greiser dispute has often been advanced as an example of Ian Kershaw's theory of "Working Towards the Führer", namely that Hitler issued vague instructions, and allowed his subordinates to work out policy on their own.

After the conquest of Poland, another major dispute broke out between different factions with one centring around Reichsfüherer SS Heinrich Himmler and Arthur Greiser championing and carrying out ethnic cleansing schemes for Poland, and another centring around Hermann Göring and Hans Frank calling for turning Poland into the "granary" of the Reich. At a conference held at Göring's Karinhall estate on 12 February 1940, the dispute was settled in favour of the Göring-Frank view of economic exploitation, and ending mass expulsions as economically disruptive. On 15 May 1940, Himmler showed Hitler a memo entitled "Some Thoughts on the Treatment of Alien Population in the East", which called for expelling the entire Jewish population of Europe into Africa and reducing the remainder of the Polish population to a "leaderless labouring class". Hitler called Himmler's memo "good and correct". Hitler's remark had the effect of scuttling the so-called Karinhall argreement, and led to the Himmler–Greiser viewpoint triumphing as German policy for Poland.

During this period, Hitler built up his forces on Germany's western frontier. In April 1940, German forces invaded Denmark and Norway. In May 1940, Hitler's forces attacked France, conquering Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Belgium in the process. These victories persuaded Benito Mussolini of Italy to join the war on Hitler's side on 10 June 1940. France surrendered on 22 June 1940.

Britain, whose forces evacuated France by sea from Dunkirk, continued to fight alongside other British dominions in the Battle of the Atlantic. After having his overtures for peace rejected by the British, now led by Winston Churchill, Hitler ordered bombing raids on the United Kingdom. The Battle of Britain was Hitler's prelude to a planned invasion. The attacks began by pounding Royal Air Force airbases and radar stations protecting South-East England. However, the Luftwaffe failed to defeat the Royal Air Force. On 27 September 1940, the Tripartite Pact was signed in Berlin by Saburō Kurusu of Imperial Japan, Hitler, and Ciano. The purpose of the pact, which was directed against an unnamed power that was clearly meant to be the United States, was to deter the Americans from supporting the British. It was later expanded to include Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. They were collectively known as the Axis powers. By the end of October 1940, air superiority for the invasion Operation Sea Lion could not be assured, and Hitler ordered the bombing of British cities, including London, Plymouth, and Coventry, mostly at night.

In the Spring of 1941, Hitler was distracted from his plans for the East by various activities in North Africa, the Balkans, and the Middle East. In February, German forces arrived in Libya to bolster the Italian forces there. In April, he launched the invasion of Yugoslavia which was followed quickly by the invasion of Greece. In May, German forces were sent to support Iraqi rebel forces fighting against the British and to invade Crete. On 23 May, Hitler released Führer Directive No. 30.

Path to defeat

On 22 June 1941, three million German troops attacked the Soviet Union, breaking the non-aggression pact Hitler had concluded with Stalin two years earlier. This invasion seized huge amounts of territory, including the Baltic states, Belarus, and Ukraine. It also encircled and destroyed many Soviet forces, which Stalin had ordered not to retreat. However, the Germans were stopped barely short of Moscow in December 1941 by the Russian Winter and fierce Soviet resistance. The invasion failed to achieve the quick triumph Hitler wanted.

A major historical dispute concerns Hitler's reasons for Operation Barbarossa. Some historians such as Andreas Hillgruber have argued that Barbarossa was merely one "stage" of Hitler's Stufenplan (stage by stage plan) for world conquest, which Hillgruber believed that Hitler had formulated in the 1920s. Other historians such as John Lukacs have contended that Hitler never had a stufenplan, and that the invasion of the Soviet Union was an ad hoc move on the part of Hitler due to Britain's refusal to surrender. Lukacs has argued that the reason Hitler gave in private for Barbarossa, namely that Winston Churchill held out the hope that the Soviet Union might enter the war on the Allied side, and that the only way of forcing a British surrender was to eliminate that hope, was indeed Hitler's real reason for Barbarossa. In Lukacs's perspective, Barbarossa was thus primarily an anti-British move on the part of Hitler intended to force Britain to sue for peace by destroying her only hope of victory rather than an anti-Soviet move. Klaus Hildebrand has maintained that Stalin and Hitler were independently planning to attack each other in 1941. Hildebrand has claimed that the news in the spring of 1941 of Soviet troop concentrations on the border led to Hitler engaging in a flucht nach vorn ("flight forward" – i.e. responding to a danger by charging on rather than retreating.) A third faction comprising a diverse group such as Viktor Suvorov, Ernst Topitsch, Joachim Hoffmann, Ernst Nolte, and David Irving have argued that the official reason given by the Germans for Barbarossa in 1941 was the real reason, namely that Barbarossa was a "preventive war" forced on Hitler to avert an impeding Soviet attack scheduled for July 1941. This theory has been widely attacked as erroneous; the American historian Gerhard Weinberg once compared the advocates of the preventive war theory to believers in "fairy tales"

The Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union reached its apex on 2 December 1941 as part of the 258th Infantry Division advanced to within 15 miles (24 km) of Moscow, close enough to see the spires of the Kremlin, but they were not prepared for the harsh conditions brought on by the first blizzards of winter and in the days that followed, Soviet forces drove them back over 320 kilometres (200 miles).

On 7 December 1941, Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, and four days later, Hitler's formal declaration of war against the United States officially engaged him in war against a coalition that included the world's largest empire (the British Empire), the world's greatest industrial and financial power (the United States), and the world's largest army (the Soviet Union).

On 18 December 1941, the appointment book of the Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler shows he met with Hitler, and in response to Himmler's question "What to do with the Jews of Russia?", Hitler's response was recorded as "als Partisanen auszurotten" ("exterminate them as partisans"). The Israeli historian Yehuda Bauer has commented that the remark is probably as close as historians will ever get to a definitive order from Hitler for the genocide carried out during the Holocaust.

In late 1942, German forces were defeated in the second battle of El Alamein, thwarting Hitler's plans to seize the Suez Canal and the Middle East. In February 1943, the Battle of Stalingrad ended with the destruction of the German 6th Army. Thereafter came the Battle of Kursk. Hitler's military judgment became increasingly erratic, and Germany's military and economic position deteriorated along with Hitler's health, as indicated by his left hand's severe trembling. Hitler's biographer Ian Kershaw and others believe that he may have suffered from Parkinson's disease. Syphilis has also been suspected as a cause of at least some of his symptoms, although the evidence is slight.

Following the allied invasion of Sicily (Operation Husky) in 1943, Mussolini was deposed by Pietro Badoglio, who surrendered to the Allies. Throughout 1943 and 1944, the Soviet Union steadily forced Hitler's armies into retreat along the Eastern Front. On 6 June 1944, the Western Allied armies landed in northern France in what was one of the largest amphibious operations in history, Operation Overlord. Realists in the German army knew defeat was inevitable, and some plotted to remove Hitler from power.

Attempted assassination

There were numerous attempts or ideas by private individuals, organisations or states wishing to assassinate Hitler. Some of the plans proceeded to significant degrees. While some attempts occurred before World War II, the most famous attempt came from within Germany. The plan was at least partly driven by the prospect of the increasingly imminent defeat of Germany in the war.

In July 1944, as part of Operation Valkyrie in what became known as the 20 July plot, Claus von Stauffenberg planted a bomb in Hitler's headquarters, the Wolfsschanze (Wolf's Lair) at Rastenburg. Hitler narrowly escaped death due to random chance, as someone unknowingly moved the briefcase that contained a bomb by pushing it behind a leg of the heavy conference table. When the bomb exploded, the table subsequently deflected much of the blast away from Hitler. Later, Hitler ordered savage reprisals, resulting in the executions of more than 4,900 people, sometimes by starvation in solitary confinement followed by slow strangulation. The main resistance movement was destroyed, although smaller isolated groups continued to operate.

Defeat and death

Main article: Death of Adolf HitlerBy late 1944, the Red Army had driven the Germans back into Central Europe and the Western Allies were advancing into Germany. After watching the twin defeats in his Ardennes Offensive from his Adlerhorst command complex – Operation Wacht am Rhein and Operation Nordwind – Hitler realized that Germany had lost the war, but allowed no retreats. He hoped to negotiate a separate peace with America and Britain, a hope buoyed by the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt on 12 April 1945. Hitler's stubbornness and defiance of military realities allowed the Holocaust to continue. He ordered the complete destruction of all German industrial infrastructure before it could fall into Allied hands, saying that Germany's failure to win the war forfeited its right to survive. Rather, Hitler decided that the entire nation should go down with him. Execution of this scorched earth plan was entrusted to arms minister Albert Speer, who quietly disobeyed the order.

On 20 April, Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday in the Führerbunker ("Führer's shelter") below the Reichskanzlei (Reich Chancellery). Elsewhere, the garrison commander of the besieged Festung Breslau ("fortress Breslau"), General Hermann Niehoff, had chocolates distributed to his troops in honour of Hitler's birthday.

By 21 April, Georgi Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front had broken through the last defences of German General Gotthard Heinrici's Army Group Vistula during the Battle of the Seelow Heights. Facing little resistance, the Soviets advanced headlong into the outskirts of Berlin. Ignoring the facts, Hitler saw salvation in the ragtag units commanded by Waffen SS General Felix Steiner. Steiner's command became known as Armeeabteilung Steiner ("Army Detachment Steiner"). But "Army Detachment Steiner" existed primarily on paper. It was more than a corps but less than an army. Hitler ordered Steiner to attack the northern flank of the huge salient created by the breakthrough of Zhukov's 1st Belorussian Front. Meanwhile, the German Ninth Army, which had been pushed south of the salient, was ordered to attack north in a pincer attack.

Late on 21 April, Heinrici called Hans Krebs, chief of the Oberkommando des Heeres (Supreme Command of the Army or OKH), and told him that Hitler's plan could not be implemented. Heinrici asked to speak to Hitler but was told by Krebs that Hitler was too busy to take his call.

On 22 April, during the military conference, Hitler interrupted the report to ask what had happened to Steiner's offensive. There was a long silence. Then Hitler was told that the attack had never been launched and the Russians had broken through into Berlin. Hitler asked everyone except Wilhelm Keitel, Hans Krebs, Alfred Jodl, Wilhelm Burgdorf, and Martin Bormann to leave the room, and launched into a tirade against the treachery and incompetence of his commanders. This culminated with Hitler openly declaring for the first time the war was lost. Hitler announced he would stay in Berlin, head up the defence of the city and then shoot himself.

Before the day ended, Hitler again found salvation in a new plan that included General Walther Wenck's Twelfth Army. This new plan had Wenck turn his army – currently facing the Americans to the west – and attack towards the east to relieve Berlin. Twelfth Army was to link up with Ninth Army and break through to the city. Wenck did attack and, in the confusion, made temporary contact with the Potsdam garrison. But the link with the Ninth Army, like the plan in general, was ultimately unsuccessful.

On 23 April, Joseph Goebbels made the following proclamation to the people of Berlin: