This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 202.156.6.54 (talk) at 16:41, 28 April 2006 (Rv; since you insists to revert any edits without reasoning). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 16:41, 28 April 2006 by 202.156.6.54 (talk) (Rv; since you insists to revert any edits without reasoning)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)You must add a |reason= parameter to this Cleanup template – replace it with {{Cleanup|April 2006|reason=<Fill reason here>}}, or remove the Cleanup template.

| Sima Qian's names | ||

|---|---|---|

| Family name and given name | Style name | |

| Traditional | 司馬遷 | 子長 |

| Simplified | 司马迁 | 子长 |

| Pinyin | Sīmǎ Qiān | Zichang |

| Wade-Giles | Ssŭma Ch'ien | Tzu-ch'ang |

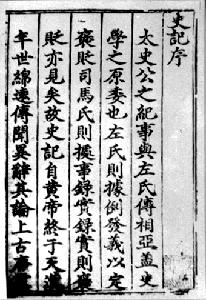

Sima Qian (司馬遷) (145–80s BC) was a Prefect of the Grand Scribes (太史令) of the Han Dynasty. He is regarded as the father of Chinese historiography because of his highly praised work, Shiji (史記, "history record"), an overview of the history of China covering more than two thousand years from the Yellow Emperor to Emperor Han Wudi (漢武帝). His work laid the foundation for later Chinese historiography.

Early life and education

Sima Qian was born and grew up in Longmen, near present-day Hancheng. He was raised in a family of historiographers. His father, Sima Tan (司馬談), served as the Prefect of the Grand Scribes of Emperor Han Wudi. His main responsibilities were managing the imperial library and calendar. Under the influence of his father, at the age of ten, Sima Qian was already well versed in old writings. He was the student of the famous Confucians Kong Anguo (孔安國) and Dong Zhongshu (董仲舒). At the age of twenty, with the support of his father, Sima Qian started a journey throughout the country, collecting useful first-hand historical records for his main work, Shiji. The purpose of his journey was to verify the ancient rumors and legends and to visit ancient monuments, including the renowned graves of the ancient sage kings Yu and Shun. Places he had visited include Shandong, Yunnan, Hebei, Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Jiangxi and Hunan. After his travels, he was chosen to be the Palace Attendant (郎中, Lang Zhong) in the government, whose duties were to inspect different parts of the country with Emperor Han Wudi. In 110 BC, at the age of thirty-five, Sima Qian was sent westward on a military expedition against some "barbarian" tribes. In 110 BC, Sima Tan fell ill for not being allowed to attend the Imperial Feng Sacrifice. Suspecting his time was running out, he summoned his son back to carry on the family tradition, that is, to complete the historical work he had begun. Sima Tan had the ambition to follow the Annals of Spring and Autumn (春秋左氏傳 the first chronicle in the history of Chinese literature). Therefore, from 109 BC, Sima Qian started to compile Shiji and inherited his father's inspiration. In 105 BC, Sima Qian was among the scholars chosen to reform the calendar. As a senior imperial official, Sima Qian was also in the position to offer counsel to the emperor on general affairs of state. In 99 BC, Sima Qian got involved in the Li Ling (李陵) Affair. Li Guangli (李廣利) and Li Ling, two military officers, were ordered to lead a campaign against the Xiongnu (匈奴)in the north. Having been defeated and taken as captives, Emperor Han Wudi attributed the defeat to Li Ling.

While all the officials in the government condemned Li Ling for the defeat, Sima Qian was the only person who defended Li Ling, who had never been his friend but whom he respected. Emperor Han Wudi thought Sima Qian’s defence of Li Ling was an attack on Wudi's brother-in-law who was fighting against Xiongnu without much success. Subsequently, he was sentenced to death. At that time, execution could be replaced either by money or mutilation (i.e. castration). Since Sima Qian did not have enough money to atone his fault, he chose the latter and was then thrown into prison.

In 96 BC, Sima Qian was released from prison. The three-year ordeal in prison ("When you see the jailer you abjectly touch the ground with your forehead. At the mere sight of his underlings you are seized with terror... Such ignominy can never be wiped away.") did not frighten Sima Qian away. On the contrary, it became a driving force compelling him to succeed his family’s legacy of recounting history. So he continued to write Shiji, which was finally finished in 91 BC.

Historian

Although the style and form of Chinese historical writings varied through the ages, Sima Qian’s Shiji has since dictated the proceeding quality and style. Not only is this due to the fact that the Chinese historical form was codified in the second dynastic history by Ban Gu’s (班固) Han Shu (漢書), but historians regard Sima Qian’s work as their model, which stands as the "official format" of the history of China.

In writing Shiji, Sima Qian initiated a new writing style by presenting history in a series of biographies. His work extends over 130 chapters — not in historical sequence, but was divided into particular subjects, including annals, chronicles, treatises — on music, ceremonies, calendars, religion, economics, and extended biographies. Before Sima Qian, histories were written as dynastic history; his idea of a general history affected later historiographers like Zhengqiao (鄭樵) in writing Tongshi (通史) and Sima Guang (司馬光) in writing Zizhi Tongjian (資治通鑑). Sima Qian even affected the writing style of histories in other places, as seen in The History of Korea, which was written as a general history.

Literary figure

Sima Qian's Shiji is respected as a model of biographical literature with high literary value.

Skillful depiction: its artistry was mainly reflected in the skillful portrayal of many distinctive characters which were based on true historical information. Sima Qian was also good at illustrating the response of the character by placing him in a sharp confrontation and letting his words and deeds speak for him. The use of conversations in his writing also makes the descriptions more vibrant and realistic.

Innovative approach: Sima Qian also initiated a new approach in writing history. The language used in Shiji was informal, humorous and full of variations. This was an innovative way of writing at that time and thus it has always been esteemed as the highest achievement of classical Chinese writing; even Lu Xun (魯迅) regarded Shiji as "the first and last great work by historians, poems of Qu Yuan without rhyme." (史家之絕唱,無韻之離騷) in his Hanwenxueshi Gangyao (《漢文學史綱要‧司馬相如與司馬遷》).

Concise language: Sima Qian formed his own simple, concise, fluent, and easy-to-read style. He made his own comments while recounting the historical events. In writing the biographies in Shiji, he avoided making general descriptions. Instead, he tried to catch the essence of the events and portrayed the characters concretely and thus the characters in Shiji gave the readers vivid images with strong artistic appeal.

Influence on literature: Sima Qian’s writings were influential to Chinese writing, which become a role model for various types of prose within the neo-classical (fu gu ) (复古) movement of the Tang-Song (唐宋) period. The great use of characterisation and plotting also influenced fictional writing, including the classical short stories of the middle and late medieval period (Tang-Ming ), as well as the vernacular novel of the late imperial period. Shiji still stands as a "textbook" for the studies of classical Chinese worldwide.

Other literary works: apart from Shiji, Sima Qian had written eight rhapsodies (Fu 賦), which are compiled in Ban Gu's Hanshu. Sima Qian expressed his suffering during the Li Ling Affair and his perseverance in writing Shiji in these rhapsodies.

Astrologer

Sima Tan and later his son, Sima Qian, were both court astrologers (taishi) 太史 in the Former Han Dynasty. At that time, the astrologer was an important post, responsible for interpreting and predicting the course of government according to the influence of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as other phenomena like solar eclipses, earthquakes, etc.

Before compiling Shiji, in 104 BC, with the help of his colleagues, Sima Qian created Taichuli (which can be translated as 'The first calendar') on the basis of the Qin calendar. Taichuli was one of the most advanced calendars of the time as it stated that there were 365.25 days in a year and 29.53 days in a month. The creation of Taichuli was regarded as a revolutio