This is an old revision of this page, as edited by A1candidate (talk | contribs) at 22:03, 15 August 2014 (Please get consensus first). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:03, 15 August 2014 by A1candidate (talk | contribs) (Please get consensus first)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For the recording, see Acupuncture (album).Medical intervention

| Acupuncture | |

|---|---|

Needles being inserted into a person's skin Needles being inserted into a person's skin | |

| ICD-10-PCS | 8E0H30Z |

| ICD-9 | 99.91-99.92 |

| MeSH | D015670 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-975.2 |

| [edit on Wikidata] | |

Acupuncture is the stimulation of specific acupuncture points along the skin of the body involving various methods such as penetration by thin needles or the application of heat, pressure, or laser light. Traditional acupuncture involves needle insertion, moxibustion, and cupping therapy. It is a form of complementary and alternative medicine and a key component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). According to TCM, stimulating specific acupuncture points corrects imbalances in the flow of qi through channels known as meridians. Acupuncture aims to treat a range of conditions, though is most commonly used for pain relief.

Acupuncture has been the subject of active scientific research, both in regard to its basis and therapeutic effectiveness, since the late 20th century. Any evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture is "variable and inconsistent" for all conditions. An overview of high-quality Cochrane reviews suggested that acupuncture may alleviate some but not all kinds of pain, while a systematic review of systematic reviews found little evidence that acupuncture is an effective treatment for reducing pain. Although minimally invasive, the puncturing of the skin with acupuncture needles poses problems when designing trials that adequately control for placebo effects. Some of the research results suggest acupuncture can alleviate pain but others consistently suggest that acupuncture's effects are mainly due to placebo. A systematic review of systematic reviews highlighted recent high-quality randomized controlled trials which found that for reducing pain, real acupuncture was no better than sham acupuncture. It remains unclear whether acupuncture reduces pain independent of a psychological impact of the needling ritual.

Acupuncture is generally safe when done using clean technique and single use needles. When properly delivered, it has a low rate of mostly minor adverse effects. Between 2000 and 2009, at least ninety-five cases of serious adverse events, including five deaths, were reported to have resulted from acupuncture. Many of the serious events were reported from developed countries and many were due to malpractice. Since serious adverse events continue to be reported, it is recommended that acupuncturists be trained sufficiently to reduce the risk. A meta-analysis found that acupuncture for chronic low back pain was cost-effective as a complement to standard care, but not as a substitute for standard care except in cases where comorbid depression presented, while a systematic review found insufficient evidence for the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic low back pain.

Scientific investigation has not found any histological or physiological evidence for traditional Chinese concepts such as qi, meridians, and acupuncture points, and some contemporary practitioners use acupuncture without following the traditional Chinese approach and have abandoned the concepts of qi and meridians as pseudoscientific. TCM is largely pseudoscience, with no valid mechanism of action for the majority of its treatments. Acupuncture is currently used widely throughout China and many other countries, including the United States. It is uncertain exactly when acupuncture originated or how it evolved, but it is generally thought to derive from ancient China. Chinese history attributes the introduction of acupuncture to the emperor Shennong. Hieroglyphs and pictographs have been found dating from the Shang Dynasty (1600–1100 BCE), which suggests that acupuncture was practiced along with moxibustion.

Clinical practice

Acupuncture is the stimulation of precisely defined, specific acupuncture points along the skin of the body involving various methods such as penetration by thin needles or the application of heat, pressure, or laser light. In a modern acupuncture session, an initial consultation is followed by taking the pulse on both arms and inspecting the tongue. Classically, in clinical practice, acupuncture is highly individualized and based on philosophy and intuition, and not on controlled scientific research. The number and frequency of acupuncture sessions vary, but most practitioners do not think one session is sufficient. The initial evaluation may last up to 60 minutes. Subsequent visits typically last about a half an hour. A common treatment plan for a single complaint usually involves six to twelve treatments, planned out over a few months. Approximately five to twenty needles are used in a regular treatment. For the majority of cases, the needles will stay in place for 10 to 20 minutes while you are lying still.

Clinical practice varies depending on the country. A comparison of the average number of patients treated per hour found significant differences between China (10) and the United States (1.2). Traditional acupuncture involves needle insertion, moxibustion, and cupping therapy. Acupuncturists generally practice acupuncture as an overall system of care, which includes using traditional diagnostic techniques, acupuncture needling, and other adjunctive treatments. Chinese herbs are also often used.

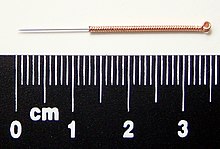

Needles

Acupuncture needles are typically made of stainless steel, making them flexible and preventing them from rusting or breaking. Needles are usually disposable, and are thrown away after use to prevent contamination. Reusable needles are sometimes used as well, though they must be sterilized between uses. Needles vary in length between 13 to 130 millimetres (0.51 to 5.12 in), with shorter needles used near the face and eyes, and longer needles in more fleshy areas; needle diameters vary from 0.16 mm (0.006 in) to 0.46 mm (0.018 in), with thicker needles used on more robust patients. Thinner needles may be flexible and require tubes for insertion. The tip of the needle should not be made too sharp to prevent breakage, although blunt needles cause more pain.

Apart from the usual filiform needle, other needle types include three-edged needles and the Nine Ancient Needles. Japanese acupuncturists use extremely thin needles that are used superficially, sometimes without penetrating the skin, and surrounded by a guide tube (a 17th-century invention adopted in China and the West). Korean acupuncture uses copper needles and has a greater focus on the hand.

Needling technique

Insertion

The skin is sterilized, such as with alcohol, and the needles are inserted, frequently with a plastic guide tube. Needles may be manipulated in various ways, including spinning, flicking, or moving up and down relative to the skin. Since most pain is felt in the superficial layers of the skin, a quick insertion of the needle is recommended. Acupuncture can be painful. The skill level of the acupuncturist may influence how painful the needle insertion is, and a sufficiently skilled practitioner may be able to insert the needles without causing any pain.

De-qi sensation

De-qi (Chinese: 得气; pinyin: dé qì; "arrival of qi") refers to a sensation of numbness, distension, or electrical tingling at the needling site which might radiate along the corresponding meridian. If de-qi can not be generated, then inaccurate location of the acupoint, improper depth of needle insertion, inadequate manual manipulation, or a very weak constitution of the patient have to be considered, all of which are thought to decrease the likelihood of successful treatment. If the de-qi sensation doesn't immediately occur upon needle insertion, various manual manipulation techniques can be applied to promote it (such as "plucking", "shaking" or "trembling").

Once de-qi is achieved, further techniques might be utilized which aim to "influence" the de-qi; for example, by certain manipulation the de-qi sensation allegedly can be conducted from the needling site towards more distant sites of the body. Other techniques aim at "tonifying" (Chinese: 补; pinyin: bǔ) or "sedating" (Chinese: 泄; pinyin: xiè) qi. The former techniques are used in deficiency patterns, the latter in excess patterns.

De qi is more important in Chinese acupuncture, while Western and Japanese patients may not consider it a necessary part of the treatment.

Non-invasive needling

There is also a non-invasive therapy developed in early 20th century Japan using an elaborate set of "needles" for the treatment of children (shōnishin or shōnihari).

Related practices

Acupressure, a non-invasive form of acupuncture, uses physical pressure applied to acupressure points by the hand, elbow, or with various devices. Acupuncture is often accompanied by moxibustion, the burning of cone-shaped preparations of moxa (made from dried mugwort) on or near the skin, often but not always near or on an acupuncture point. Traditionally, acupuncture was used to treat acute conditions while moxibustion was used for chronic diseases. Moxibustion could be direct (the cone was placed directly on the skin and allowed to burn the skin producing a blister and eventually a scar), or indirect (either a cone of moxa was placed on a slice of garlic, ginger or other vegetable, or a cylinder of moxa was held above the skin, close enough to either warm or burn it). Cupping therapy is an ancient Chinese form of alternative medicine in which a local suction is created on the skin; practitioners believe this mobilizes blood flow in order to promote healing. Tui na is a TCM method of attempting to stimulate the flow of qi by various bare-handed techniques that do not involve needles. Electroacupuncture is a form of acupuncture in which acupuncture needles are attached to a device that generates continuous electric pulses (this has been described as "essentially transdermal electrical nerve stimulation masquerading as acupuncture"). Sonopuncture or acutonics is a stimulation of the body similar to acupuncture, but using sound instead of needles. This may be done using purpose-built transducers to direct a narrow ultrasound beam to a depth of 6–8 centimetres at acupuncture meridian points on the body. Alternatively, tuning forks or other sound emitting devices are used. Acupuncture point injection is the injection of various substances (such as drugs, vitamins or herbal extracts) into acupoints. Auriculotherapy, or ear acupuncture, is a form of acupuncture developed in France which is based on the assumption of reflexological representation of the entire body in the outer ear. Scalp acupuncture, developed in Japan, is based on reflexological considerations regarding the scalp area. Hand acupuncture, developed in Korea, centers around assumed reflex zones of the hand. Medical acupuncture attempts to integrate reflexological concepts, the trigger point model, and anatomical insights (such as dermatome distribution) into acupuncture practice, and emphasizes a more formulaic approach to acupuncture point location. Cosmetic acupuncture is the use of acupuncture in an attempt to reduce wrinkles on the face.

Effectiveness

The application of evidence-based medicine to researching acupuncture's effectiveness is a controversial activity, and has produced different results in a growing evidence base of research. Some research results suggest acupuncture can alleviate pain but others consistently suggest that acupuncture's effects are mainly due to placebo. It is difficult to design research trials for acupuncture. Due to acupuncture's invasive nature, one of the major challenges in efficacy research is in the design of an appropriate placebo control group. For the efficacy studies to determine whether acupuncture has specific effects, "sham" forms of acupuncture seem the most acceptable method for a control group. An analysis suggested that sham-controlled trials may underestimate the total treatment effect of acupuncture (i.e. the incidental therapeutic factors such as talking and listening which are characteristic of the intervention), as the sham treatment is based on the hypothesis that only needling is the characteristic treatment element.

Any evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture is "variable and inconsistent" for all conditions, and publication bias is cited as a concern in the reviews of randomized controlled trials of acupuncture. A 1998 review of studies on acupuncture found that trials originating in China, Japan, Hong Kong and Taiwan were uniformly favourable to acupuncture, as were ten out of 11 studies conducted in Russia. A 2011 assessment of the quality of randomized controlled trials on TCM, including acupuncture, concluded that the methodological quality of most such trials (including randomization, experimental control and blinding) was generally poor, particularly for trials published in Chinese journals (though the quality of acupuncture trials was better than the drug-related trials). The study also found that trials published in non-Chinese journals tended to be of higher quality.

A 2013 editorial found that the inconsistency of results of acupuncture studies (that acupuncture relieved pain in some conditions but had no effect in other very similar conditions) suggests false positive results, which may be caused by factors like biased study designs, poor blinding, and the classification of electrified needles (a type of TENS) as acupuncture. The same editorial suggested that given the inability to find consistent results despite more than 3,000 studies of acupuncture, the treatment seems to be a placebo effect and the existing equivocal positive results are noise one expects to see after a large number of studies are performed on an inert therapy. It concluded that the best controlled studies showed a clear pattern, in which the outcome does not rely upon needle location or even needle insertion, and since "these variables are those that define acupuncture, the only sensible conclusion is that acupuncture does not work."

Pain

A 2012 meta-analysis conducted by the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration found "relatively modest" efficiency of acupuncture (in comparison to sham) for the treatment of four different types of chronic pain, and on that basis concluded that it "is more than a placebo" and a reasonable referral option. Commenting on this meta-analysis, both Edzard Ernst and David Colquhoun said the results were of negligible clinical significance.

A 2011 overview of high-quality Cochrane reviews suggested that acupuncture is effective for some but not all kinds of pain. A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews found that numerous reviews have shown little convincing evidence that acupuncture is an effective treatment for reducing pain. The same review found that neck pain was one of only four types of pain for which a positive effect was suggested, but cautioned that the primary studies used carried a considerable risk of bias. The review also highlighted recent high-quality randomized controlled trials which found that for reducing pain, real acupuncture was no better than sham acupuncture.

A 2010 systematic review suggested that acupuncture is more than a placebo for commonly occurring chronic pain conditions, but the authors acknowledged that it is still unknown if the overall benefit is clinically meaningful or cost-effective. A 2009 systematic review and meta-analysis found that acupuncture had a small analgesic effect, which appeared to lack any clinical importance and could not be discerned from bias. The same review found that it remains unclear whether acupuncture reduces pain independent of a psychological impact of the needling ritual.

Peripheral osteoarthritis

A 2012 review found acupuncture to provide clinically significant relief from knee osteoarthritis pain and a larger improvement in function than sham acupuncture, standard care treatment, or waiting for treatment. A review from 2008 yielded similar positive results. The Osteoarthritis Research Society International released a set of consensus recommendations in 2008 which concluded that acupuncture may be useful for treating the symptoms of osteoarthritis of the knee. A 2010 Cochrane review found that acupuncture shows statistically significant benefit over sham acupuncture in the treatment of peripheral joint osteoarthritis; however, these benefits were found to be so small that their clinical significance was doubtful, and "probably due at least partially to placebo effects from incomplete blinding".

Headaches and migraines

A 2012 review found that acupuncture has demonstrated benefit for the treatment of headaches, but that safety needed to be more fully documented in order to make any strong recommendations in support of its use. A 2009 Cochrane review of the use of acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis treatment concluded that "true" acupuncture was no more efficient than sham acupuncture, but "true" acupuncture appeared to be as effective as, or possibly more effective than routine care in the treatment of migraines, with fewer adverse effects than prophylactic drug treatment. The same review stated that the specific points chosen to needle may be of limited importance. A 2009 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to support acupuncture for tension-type headaches. The same review found evidence that suggested that acupuncture might be considered a helpful non-pharmacological approach for frequent episodic or chronic tension-type headache.

Low back

A 2011 overview of Cochrane reviews found inconclusive evidence regarding acupuncture efficacy in treating low back pain. A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews found that "for chronic low back pain, individualized acupuncture is not better in reducing symptoms than formula acupuncture or sham acupuncture with a toothpick that does not penetrate the skin." A 2010 review found that sham acupuncture was as effective as real acupuncture for chronic low back pain. The specific therapeutic effects of acupuncture were small, whereas its clinically relevant benefits were mostly due to contextual and psychosocial circumstances. Brain imaging studies have shown that traditional acupuncture and sham acupuncture differ in their effect on limbic structures, while at the same time showed equivalent analgesic effects. A 2005 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against either acupuncture or dry needling for acute low back pain. The same review found low quality evidence for pain relief and improvement compared to no treatment or sham therapy for chronic low back pain only in the short term immediately after treatment. The same review also found acupuncture is not more effective than conventional therapy and CAM treatments. A 2005 review suggested that there is insufficient evidence that acupuncture is more effective than other therapies. A review for the American Pain Society/American College of Physicians from 2007 found fair evidence that acupuncture is effective for chronic low back pain.

Fibromyalgia

A 2013 Cochrane review found low to moderate evidence that acupuncture improves pain and stiffness in treating people with fibromyalgia compared with no treatment and standard care.

Shoulder and elbow

A 2011 overview of Cochrane reviews found inconclusive evidence regarding acupuncture efficacy in treating shoulder pain and lateral elbow pain.

Post-operative

A 2014 overview of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to suggest that acupuncture is effective for surgical or postoperative pain. For the use of acupuncture for post-operative pain, there was contradictory evidence.

Cancer

A 2012 systematic review of randomised clinical trials (RCTs) using acupuncture in the treatment of cancer pain found that the number and quality of RCTs was too low to draw definite conclusions. A 2011 Cochrane review found that there is insufficient evidence to determine whether acupuncture is an effective treatment for cancer pain in adults.

A 2013 systematic review found that acupuncture is an acceptable adjunctive treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, but that further research with a low risk of bias is needed. A 2013 systematic review found that the quantity and quality of available RCTs for analysis were too low to draw valid conclusions for the effectiveness of acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue. A 2012 systematic review and meta-analysis found very limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of acupuncture compared with conventional intramuscular injections for the treatment of hiccups in cancer patients. The methodological quality and amount of RCTs in the review was low.

Depression

A 2013 Cochrane review found unclear evidence for major depressive disorders in pregnant women. A 2010 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to recommend acupuncture to treat depression. A 2010 systematic review of systematic reviews found that the effectiveness of acupuncture to treat depression is unproven and their conclusions are "consistent with acupuncture effects in depression being indistinguishable from placebo effects."

Fertility and childbirth

A 2013 Cochrane review found no evidence of acupuncture for improving the success of in vitro fertilization (IVF). A 2013 systematic review found no benefit of adjuvant acupuncture for IVF on pregnancy success rates. A 2012 systematic review found that acupuncture may be a useful adjunct to IVF, but its conclusions were rebutted after reevaluation using more rigorous, high quality meta-analysis standards.

Nausea and vomiting

A 2014 overview of systematic reviews found insufficient evidence to suggest that acupuncture is an effective treatment for post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) in a clinical setting. A 2009 Cochrane review found that the stimulation of the P6 acupoint prevented PONV was as effective (or ineffective) as antiemetic drugs and with minimal side effects. The same review found "no reliable evidence for differences in risks of postoperative nausea or vomiting after P6 acupoint stimulation compared to antiemetic drugs."

Stroke

A 2014 overview of systematic reviews and meta-analyses found that the evidence does not demonstrate acupuncture helps reduce the rates of death or disability after a stroke or improve other aspects of stroke recovery, such as poststroke motor dysfunction, but the evidence suggests it may help with poststroke neurological impairment and dysfunction such as dysphagia, which would need to be confirmed with future rigorous studies. A 2012 review found evidence of benefit for acupuncture combined with exercise in treating shoulder pain after stroke. A 2008 Cochrane review found that evidence was insufficient to draw any conclusion about the effect of acupuncture on dysphagia after acute stroke. A 2006 Cochrane review found no clear evidence for acupuncture on subacute or chronic stroke. A 2005 Cochrane review found no clear evidence of benefit for acupuncture on acute stroke.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

A 2011 Cochrane review concluded that there was no evidence to support the use of acupuncture for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). A 2011 review concluded there was limited evidence as to the effectiveness of acupuncture as a treatment option for ADHD but cautioned that firm conclusions could not be drawn because of the risk of bias.

Other conditions

For the following conditions, the Cochrane Collaboration or other reviews have concluded there is no strong evidence of benefit for alcohol dependence, ankle sprain, autism, chronic asthma, bell's palsy, carpal tunnel syndrome, cocaine dependence, depression, drug detoxification, primary dysmenorrhoea, enuresis, epilepsy, erectile dysfunction, glaucoma, gynaecological conditions (except possibly fertility and nausea/vomiting), hot flashes, insomnia, irritable bowel syndrome, induction of childbirth, labor pain, myopia, obstetrical conditions, polycystic ovary syndrome, restless legs syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, schizophrenia, smoking cessation, acute stroke, and stroke rehabilitation temporomandibular joint dysfunction, tennis elbow, tinnitus, uremic pruritus, uterine fibroids, and vascular dementia.

Moxibustion and cupping

A 2010 overview of systematic reviews found that moxibustion was effective for several conditions but the primary studies were of poor quality, so there persists ample uncertainty, which limits the conclusiveness of their findings. A 2012 systematic review suggested that cupping therapy seems to be effective for herpes zoster and various other conditions but due to the high risk of publication bias, larger studies are needed to draw definitive conclusions.

Safety

Adverse events

Acupuncture is generally safe when administered using clean technique and sterile single use needles. A 2011 systematic review of systematic reviews (internationally and without language restrictions) found that serious complications following acupuncture continue to be reported. Between 2000 and 2009, ninety-five cases of serious adverse events, including five deaths, were reported. Many such events are not inherent to acupuncture but are due to malpractice of acupuncturists. This might be why such complications have not been reported in surveys of adequately-trained acupuncturists. Most such reports are from Asia, which may reflect the large number of treatments performed there or it might be because there are a relatively higher number of poorly trained Asian acupuncturists. Many serious adverse events were reported from developed countries. This included Australia, Austria, Canada, Croatia, France, Germany, Holland, Ireland, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK, and the US. The number of adverse effects reported from the UK appears particularly unusual, which may indicate less under-reporting in the UK than other countries. 38 cases of infections were reported and 42 cases of organ trauma were reported. The most frequent adverse events included pneumothorax, and bacterial and viral infections. When not delivered properly by a qualified practitioner it can cause potentially serious adverse effects. To reduce the risk of serious adverse events after acupuncture, acupuncturists should be trained sufficiently.

English-language

A 2013 systematic review of the English-language case reports found that serious adverse events associated with acupuncture are rare, but acupuncture is not without risk. Between 2000 and 2011, there were 294 adverse events reported in the English-language literature from 25 countries and regions. The majority of the reported adverse events were relatively minor, and the incidences were low. For example, a prospective survey of 34,000 acupuncture treatments found no serious adverse events and 43 minor ones, a rate of 1.3 per 1000 interventions. Another survey found there were 7.1% minor adverse events, of which 5 were serious, amid 97,733 acupuncture patients. The most common adverse effect observed was infection, and the majority of infections were bacterial in nature, caused by skin contact at the needling site. Infections has also been caused by skin contact with unsterilized equipment or dirty towels, in an unhygienic clinical setting. Other adverse complications included five reported cases of spinal cord injuries (e.g. migrating broken needles or needling too deeply), four brain injuries, four peripheral nerve injuries, five heart injuries, seven other organ and tissue injuries, bilateral hand edema, epithelioid granuloma, pseudolymphoma, argyria, pustules, pancytopenia, and scarring due to hot needle technique. Adverse reactions from acupuncture, which are unusual and uncommon in typical acupuncture practice, were syncope, galactorrhoea, bilateral nystagmus, pyoderma gangrenosum, hepatotoxicity, eruptive lichen planus, and spontaneous needle migration.

A 2013 systematic review found 31 cases of vascular injuries were caused by acupuncture, 3 resulting in death. Two died from pericardial tamponade and one was from an aortoduodenal fistula. The same review found vascular injuries were rare, bleeding and pseudoaneurysm were most prevalent. A 2011 systematic review (without restriction in time or language), aiming to summarize all reported case of cardiac tamponade after acupuncture, found 26 cases resulting in 14 deaths, with little doubt about causality in most fatal instances. The same review concluded cardiac tamponade was a serious, usually fatal, though theoretically avoidable complication following acupuncture, and urged training to minimize risk.

Chinese, South Korean, and Japanese-language

A 2010 systematic review of the Chinese-language literature found numerous acupuncture related adverse events including pneumothorax, fainting, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and infection as the most frequent, and cardiovascular injuries, subarachnoid hemorrhage, pneumothorax, and recurrent cerebral hemorrhage as the most serious, most of which were due to improper technique. Between 1980 and 2009, the Chinese literature reported 479 adverse events. Prospective surveys shown that mild, transient acupuncture-associated adverse events ranged from 6.71% to 15%. A study with 190,924 patients, the prevalence of serious adverse events was roughly 0.024%. Another study shown a rate of adverse events requiring specific treatment was 2.2%, 4,963 incidences were among 229,230 patients. Infections, mainly hepatitis, after acupuncture are reported often in the English-language research, though it is rarely reported in the Chinese-language research, making it plausible that in China acupuncture-associated infections have been underreported. Infections were mostly caused by poor sterilization of acupuncture needles. Other adverse events included spinal epidural haematoma (in the cervical, thoracic and lumbar spine), chylothorax, injuries of abdominal organs and tissues, injuries in the neck region, injuries to the eyes, including orbital hemorrhage, traumatic cataract, injury of the oculomotor nerve and retinal puncture, hemorrhage to the cheeks and the hypoglottis, peripheral motor nerve injuries and subsequent motor dysfunction, local allergic reactions to metal needles, stroke, and cerebral hemorrhage after acupuncture. A causal link between acupuncture and the adverse events cardiac arrest, pyknolepsy, shock, fever, cough, thirst, aphonia, leg numbness, and sexual dysfunction remains uncertain. The same review concluded that acupuncture can be considered inherently safe when practiced by properly trained practitioners, but the review also stated there is a need to find effective strategies to minimize the health risks. Between 1999 and 2010, the Republic of Korean-literature contained reports of 1104 adverse events. Between the 1980s and 2002, the Japanese-language literature contained reports of 150 adverse events.

Children and pregnancy

When used on children, acupuncture is safe when administered by well-trained, licensed practitioners using sterile needles; however, there was limited research to draw definite conclusions about the overall safety of pediatric acupuncture. The same review found 279 adverse events, of which 25 were serious. The adverse events were mostly mild in nature (e.g. bruising or bleeding). The prevalence of mild adverse events ranged from 10.1% to 13.5%, an estimated 168 incidences were among 1,422 patients. On rare occasions adverse events were serious (e.g. cardiac rupture or hemoptysis), many might have been a result of substandard practice. The incidence of serious adverse events was 5 per one million, which included children and adults. When used during pregnancy, the majority of adverse events caused by acupuncture were mild and transient, with few serious adverse events. The most frequent mild adverse event was needling or unspecified pain, followed by bleeding. Although two deaths (one stillbirth and one neonatal death) were reported, there was a lack of acupuncture associated maternal mortality. Limiting the evidence as certain, probable or possible in the causality evaluation, the estimated incidence of adverse events following acupuncture in pregnant women was 131 per 10,000. In pregnant women needle insertion should be avoided in the abdominal region.

Moxibustion and cupping

Four adverse events associated with moxibustion were bruising, burns and cellulitis, spinal epidural abscess, and large superficial basal cell carcinoma. Ten adverse events were associated with cupping. The minor ones were keloid scarring, burns, and bullae; the serious ones were acquired hemophilia A, stroke following cupping on the back and neck, factitious panniculitis, reversible cardiac hypertrophy, and iron deficiency anemia.

Cost-effectiveness

A 2013 meta-analysis found that acupuncture for chronic low back pain was cost-effective as a complement to standard care, but not as a substitute for standard care except in cases where comorbid depression presented. The same meta-analysis found there was no difference between sham and non-sham acupuncture. A 2011 systematic review found insufficient evidence for the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture in the treatment of chronic low back pain.

Risk of forgoing conventional medical care

As with other alternative medicines, unethical or naïve practitioners may induce patients to exhaust financial resources by pursuing ineffective treatment. Profession ethical codes set by accrediting organizations such as the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine require practitioners to make "timely referrals to other health care professionals as may be appropriate."

Theory

| Acupuncture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 针刺 | ||||||

| |||||||

Acupuncture is a key component of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). TCM is largely pseudoscience with no valid mechanism of action for the majority of its treatments. It has notions of a pre-scientific culture, similar to European humoral theory. According to TCM, the general theory of acupuncture is based on the premise that bodily functions are regulated by an energy called qi (氣) that flows through the body; disruptions of this flow are believed to be responsible for disease. Acupuncture describes a family of procedures aiming to correct imbalances in the flow of qi by stimulation of anatomical locations on or under the skin (usually called acupuncture points or acupoints), by a variety of techniques. The most common mechanism of stimulation of acupuncture points employs penetration of the skin by thin metal needles, which are manipulated manually or by electrical stimulation.

Qi, meridians and acupuncture points

Main articles: Qi, Traditional Chinese medicine § Model of the body, Meridian (Chinese medicine), and Acupuncture pointTraditional Chinese medicine distinguishes not only one but several different kinds of qi. In a general sense, qi is something that is defined by five "cardinal functions":

Actuation (推動, tuīdòng) is of all physical processes in the body, especially the circulation of all body fluids such as blood in their vessels. This includes actuation of the functions of the zang-fu organs and meridians. Warming (溫煦, pinyin: wēnxù) the body, especially the limbs. Defense (防御, pinyin: fángyù) against Exogenous Pathogenic Factors Containment (固攝, pinyin: gùshè) of body fluids, i.e. keeping blood, sweat, urine, semen etc. from leakage or excessive emission. Transformation (氣化, pinyin: qìhuà) of food, drink, and breath into qi, xue (blood), and jinye ("fluids"), and/or transformation of all of the latter into each other.

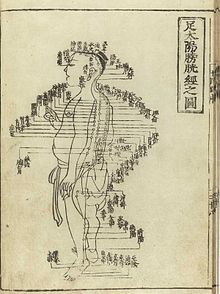

To fulfill its functions, qi has to steadily flow from the inside of the body (where the zang-fu organs are located) to the "superficial" body tissues of the skin, muscles, tendons, bones, and joints. It is assisted in its flow by "channels" referred to as meridians. TCM identifies 12 "regular" and 8 "extraordinary" meridians; the Chinese terms being 十二经脉 (pinyin: shí-èr jīngmài, lit. "the Twelve Vessels") and 奇经八脉 (pinyin: qí jīng bā mài). There's also a number of less customary channels branching off from the "regular" meridians. Contemporary research has not supported the existence of qi or meridians. The meridians are believed to connect to the bodily organs, of which those considered hollow organs (such as the stomach and intestines) were also considered yang while those considered solid (such as the liver and lungs) were considered yin. They were also symbolically linked to the rivers found in ancient China, such as the Yangtze, Wei and Yellow Rivers.

Acupuncture points are mainly (but not always) found at specified locations along the meridians. There also is a number of acupuncture points with specified locations outside of the meridians; these are called extraordinary points and are credited to treat certain diseases. A third category of acupuncture points called "A-shi" points have no fixed location but represent tender or reflexive points appearing in the course of pain syndromes. The actual number of points have varied considerably over time, initially they were considered to number 365, symbolically aligning with the number of days in the year (and in Han times, the number of bones thought to be in the body). The Nei ching mentioned only 160 and a further 135 could be deduced giving a total of 295. The modern total was once considered 670 but subsequently expanded due to more recent interest in auricular (ear) acupuncture and the treatment of further conditions. In addition, it is considered likely that some points used historically have since ceased being used.

TCM concept of disease

See also: Traditional Chinese medicine § Concept of diseaseIn Traditional Chinese Medicine, disease is generally perceived as a disharmony or imbalance in the functions or interactions of such concepts as yin, yang, qi, xuĕ, zàng-fǔ, meridians, and of the interaction between the body and the environment. Therapy is based on which "pattern of disharmony" can be identified. In the case of the meridians, typical disease patterns are invasions with wind, cold, and damp Excesses. In order to determine which pattern is at hand, practitioners will examine things like the color and shape of the tongue, the relative strength of pulse-points, the smell of the breath, the quality of breathing, or the sound of the voice. TCM and its concept of disease do not strongly differentiate between cause and effect. In theory, however, endogenous, exogenous and miscellaneous causes of disease are recognized.

Traditional diagnosis

The acupuncturist decides which points to treat by observing and questioning the patient to make a diagnosis according to the tradition used. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, the four diagnostic methods are: inspection, ausculation and olfaction, inquiring, and palpation. Inspection focuses on the face and particularly on the tongue, including analysis of the tongue size, shape, tension, color and coating, and the absence or presence of teeth marks around the edge. Auscultation and olfaction is listening for particular sounds (such as wheezing) and attending to body odor. Inquiring is focusing on the "seven inquiries": chills and fever; perspiration; appetite, thirst and taste; defecation and urination; pain; sleep; and menses and leukorrhea. Palpation is focusing on feeling the body for tender A-shi points and feeling the left and right radial pulses.

Tongue and pulse

Examination of the tongue and the pulse are among the principal diagnostic methods in TCM. Certain sectors of the tongue's surface are believed to correspond to the zàng-fŭ. For example, teeth marks on one part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the heart, while teeth marks on another part of the tongue might indicate a problem with the liver.

Pulse palpation involves measuring the pulse at a superficial and at a deep level at three locations on the radial artery (Cun, Guan, Chi, located two fingerbreadths from the wrist crease, one fingerbreadth from the wrist crease, and right at the wrist crease, respectively, usually palpated with the index, middle and ring finger) of each arm, for 12 pulses, all of which are thought to correspond with certain zàng-fŭ. The pulse is examined for several characteristics including rhythm, strength, and volume, and is described with qualities like "floating, slippery, bolstering-like, feeble, thready and quick". Each of these qualities indicate certain disease patterns. Training on the use of TCM pulse diagnosis can take several years.

Scientific view on TCM theory

Some modern practitioners have embraced the use of acupuncture to treat pain, but have abandoned the use of qi, meridians, yin and yang as explanatory frameworks. They, along with acupuncture researchers, explain the analgesic effects of acupuncture as caused by the release of endorphins, and recognize the lack of evidence that it can affect the course of any disease. The use of qi as an explanatory framework has been decreasing in China, even as it becomes more prominent during discussions of acupuncture in the United States. Despite the scientific evidence against such mystical explanations, academic discussions of acupuncture still make reference to pseudoscientific concepts like qi and meridians, in practice making many scholarly efforts to integrate evidence for efficacy and discussions of the mechanism impossible. Qi, yin, yang and meridians have no counterpart in modern studies of chemistry, biology, physics, or human physiology and to date scientists have been unable to find evidence that supports their existence.

Similarly, no research has established any consistent anatomical structure or function for either acupuncture points or meridians. The electrical resistance of acupuncture points and meridians have also been studied, with conflicting results.

A 2013 meta-analysis found little evidence that the effectiveness of acupuncture on pain (compared to sham) was modified by the location of the needles, the number of needles used, the experience or technique of the practitioner, or by the circumstances of the sessions. The same analysis also suggested that the number of needles and sessions is important, as greater numbers improved the outcomes of acupuncture compared to non-acupuncture controls.

Quackwatch stated that:

TCM theory and practice are not based upon the body of knowledge related to health, disease, and health care that has been widely accepted by the scientific community. TCM practitioners disagree among themselves about how to diagnose patients and which treatments should go with which diagnoses. Even if they could agree, the TCM theories are so nebulous that no amount of scientific study will enable TCM to offer rational care.

History

Antiquity

The precise start date that acupuncture was generally held to have originated in ancient China and how it evolved from early times are uncertain. Chinese history attributes the introduction of acupuncture to the emperor Shennong. One explanation is that Han Chinese doctors observed that some soldiers wounded in battle by arrows were believed to have been cured of chronic afflictions that were otherwise untreated, and there are variations on this idea. Sharpened stones known as Bian shi have been found in China, suggesting the practice may date to the Neolithic or possibly even earlier in the Stone Age. Hieroglyphs and pictographs have been found dating from the Shang Dynasty (1600–1100 BCE) which suggests that acupuncture was practiced along with moxibustion. It has also been suggested that acupuncture has its origins in bloodletting or demonology.

Despite improvements in metallurgy over centuries, it was not until the 2nd century BCE during the Han Dynasty that stone and bone needles were replaced with metal. The earliest examples of metal needles were found in a tomb dated to c. 113 BCE, though their use might not necessarily have been acupuncture. The earliest example of the unseen meridians (经络, pinyin: jīng-luò) used for diagnosis and treatment are dated to the second century BCE but these records do not mention needling, while the earliest reference to therapeutic needling occurs in the historical Shiji text (史記, English: Records of the Grand Historian) but does not mention the meridians and may be a reference to lancing rather than acupuncture.

The earliest written record of acupuncture is found in the Huangdi Neijing (黄帝内经; translated as The Yellow Emperor's Inner Canon), dated approximately 200 BCE. It does not distinguish between acupuncture and moxibustion and gives the same indication for both treatments. The Mawangdui texts, which also date from the 2nd century BCE (though antedating both the Shiji and Huangdi Neijing), mention the use of pointed stones to open abscesses, and moxibustion, but not acupuncture. However, by the 2nd century BCE, acupuncture replaced moxibustion as the primary treatment of systemic conditions.

The practice of acupuncture expanded out of China into the areas now part of Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan, diverging from the narrower theory and practice of mainland TCM in the process. A large number of contemporary practitioners outside of China follow these non-TCM practices, particularly in Europe.

In Europe, examinations of the 5,000-year-old mummified body of Ötzi the Iceman have identified 15 groups of tattoos on his body, some of which are located on what are now seen as contemporary acupuncture points. This has been cited as evidence that practices similar to acupuncture may have been practiced elsewhere in Eurasia during the early Bronze Age.

Middle history

Korea is believed to be the second country that acupuncture spread to outside of China. Within Korea there is a legend that acupuncture was developed by the legendary emperor Dangun though it is more likely to have been brought into Korea from a Chinese colonial prefecture.

Around 90 works on acupuncture were written in China between the Han Dynasty and the Song Dynasty, and the Emperor Renzong of Song, in 1023, ordered the production of a bronze statuette (Dongren) depicting the meridians and acupuncture points then in use. However, after the end of the Song Dynasty, acupuncture lost status, and started to be seen as a technical profession, in comparison to the more scholarly profession of herbalism. It became rarer in the following centuries, and was associated with less prestigious practices like alchemy, shamanism, midwifery and moxibustion.

Portuguese missionaries in the 16th century were among the first to bring reports of acupuncture to the West. Jacob de Bondt, a Dutch surgeon traveling in Asia, described the practice in both Japan and Java. However, in China itself the practice was increasingly associated with the lower-classes and illiterate practitioners.

In 1674, Hermann Buschoff, a Dutch priest in Batavia, published the first book on moxibustion (from Japanese mogusa). The first elaborate Western treatise on acupuncture was published in 1683 by Willem ten Rhijne, a Dutch physician who had worked at the Dutch trading post Dejima in Nagasaki for two years. In 1712 a detailed description of the treatment of "Colics" in Japan was published by the German physician Engelbert Kaempfer. But while moxibustion was widely discussed among central European physicians, ten Rhijne's and especially Kaempfer's explanations about piercing the abdomen had caused some misunderstandings that eventually led to the refutal of acupuncture by influential scholars such as Lorenz Heister and Georg Stahl.

In 1757 the Chinese physician Xu Daqun described the further decline of acupuncture, saying it was a lost art, with few experts to instruct; its decline was attributed in part to the popularity of prescriptions and medications, as well as its association with the lower classes. In 1822, an edict from the Emperor Daoguang banned the practice and teaching of acupuncture within the Imperial Academy of Medicine outright, as unfit for practice by gentlemen-scholars. At this point, acupuncture was still cited in Europe with both skepticism and praise, with little study and only a small amount of experimentation.

While the details of how acupuncture came to Europe are debated, the French doctor Louis Berlioz (the father of the composer Hector Berlioz) is usually credited with first experimenting the procedure in 1810, before publishing his findings in 1816. In the United States, the earliest reports of acupuncture date back to 1826, when Franklin Bache, a surgeon of the United States Navy, published a report in the North American Medical and Surgical Journal on his use of acupuncture to treat lower back pain. Since the beginning of the 19th century, acupuncture was practiced by Asian immigrants living in Chinatowns.

Modern era

In the early years after the Chinese Civil War, Chinese Communist Party leaders ridiculed traditional Chinese medicine, including acupuncture, as superstitious, irrational and backward, claiming that it conflicted with the Party's dedication to science as the way of progress. Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong later reversed this position, saying that "Chinese medicine and pharmacology are a great treasure house and efforts should be made to explore them and raise them to a higher level." Under Mao's leadership, in response to the lack of modern medical practitioners, acupuncture was revived and its theory rewritten to adhere to the political, economic and logistic necessities of providing for the medical needs of China's population. Despite Mao proclaiming the practice of Chinese medicine to be "scientific", the practice was based more on the materialist assumptions of Marxism in opposition to superstition rather than the Western practice of empirical investigation of nature. Later the 1950s TCM's theory was again rewritten at Mao's insistence as a political response to the lack of unity between scientific and traditional Chinese medicine, and to correct the supposed "bourgeois thought of Western doctors of medicine". Despite publicly promoting the practice, Mao himself did not believe in or use traditional Chinese medicine.

Acupuncture gained attention in the United States when the U.S. President Richard Nixon visited China in 1972. During one part of the visit, the delegation was shown a patient undergoing major surgery while fully awake, ostensibly receiving acupuncture rather than anesthesia. Later it was found that the patients selected for the surgery had both a high pain tolerance and received heavy indoctrination before the operation; these demonstration cases were also frequently receiving morphine surreptitiously through an intravenous drip that observers were told contained only fluids and nutrients. One patient receiving open heart surgery while awake was ultimately found to have received a combination of three powerful sedatives as well as large injections of a local anesthetic into the wound.

The greatest exposure in the West came after New York Times reporter James Reston received acupuncture in Beijing for post-operative pain in 1971 and wrote complaisantly about it in his newspaper. In 1972 the first legal acupuncture center in the U.S. was established in Washington DC; during 1973-1974, this center saw up to one thousand patients. In 1973 the American Internal Revenue Service allowed acupuncture to be deducted as a medical expense.

Acupuncture has been the subject of active scientific research both in regard to its basis and therapeutic effectiveness since the late 20th century. Even though acupuncture is currently widely used in clinical practice, it remains a controversial topic. In 2006, a BBC documentary Alternative Medicine filmed a patient undergoing open heart surgery allegedly under acupuncture-induced anesthesia. It was later revealed that the patient had been given a cocktail of weak anesthetics that in combination could have a much more powerful effect. The program was also criticized for its fanciful interpretation of the results of a brain scanning experiment. In 2010, acupuncture was recognized by UNESCO as part of the world's intangible cultural heritage.

International reception

General public

Acupuncture has become popular in the U.S., China, and other parts of the world. It is viewed as a form of complementary and alternative medicine, which aims to treat a range of conditions. Acupuncture is most commonly used for pain relief.

- Australia

In Australia, a 2005 national survey revealed that nearly 1 in 10 adults have used acupuncture in the previous year.

- United States

In the United States, less than one percent of the total population reported having used acupuncture in the early 1990s. In 2002, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine revealed that 2.1 million adults have used acupuncture in the previous 12 months. By the early 2010s, over 14 million Americans reported having used acupuncture as part of their health care. Each year, around 10 million acupuncture treatments are administered in the United States.

- United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, a total of 4 million acupuncture treatments were administered in 2009.

- Germany

According to several public health insurance organizations, women comprise over two-thirds of all acupuncture users in Germany. After the results of the German Acupuncture Trials were published in 2007, the number of regular users of acupuncture jumped by 20%, surpassing one million in 2011.

- Switzerland

In Switzerland, acupuncture has become the most frequently used complementary medicine since 2004.

Government agencies

In 2006, the National Institutes of Health's (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine stated that it continued to abide by the pro-acupuncture recommendations of the 1997 NIH consensus statement, even if research is still unable to explain its mechanism.

In its 1997 statement, the NIH had concluded that despite research on acupuncture being difficult to conduct, there was sufficient evidence to encourage further study and expand its use. The consensus statement and conference that produced it were criticized by Wallace Sampson, founder of the Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine, writing for an affiliated publication of Quackwatch who stated the meeting was chaired by a strong proponent of acupuncture and failed to include speakers who had obtained negative results on studies of acupuncture. Sampson also stated he believed the report showed evidence of pseudoscientific reasoning.

The National Health Service of the United Kingdom states that at the present, no definite conclusions regarding acupuncture efficacy can be drawn, citing disagreement among scientists "over the way acupuncture trials should be carried out and over what their results mean".

International organizations

In 2003, the World Health Organization's Department of Essential Drugs and Medicine Policy produced a report on acupuncture. The report was drafted, revised and updated by Zhu-Fan Xie, the Director for the Institute of Integrated Medicines of Beijing Medical University. It contained, based on research results available in early 1999, a list of diseases, symptoms or conditions for which it was believed acupuncture had been demonstrated as an effective treatment, as well as a second list of conditions that were possibly able to be treated with acupuncture. Noting the difficulties of conducting controlled research and the debate on how to best conduct research on acupuncture, the report described itself as "...intended to facilitate research on and the evaluation and application of acupuncture. It is hoped that it will provide a useful resource for researchers, health care providers, national health authorities and the general public." The coordinator for the team that produced the report, Xiaorui Zhang, stated that the report was designed to facilitate research on acupuncture, not recommend treatment for specific diseases.

The report was controversial; critics assailed it as being problematic since, in spite of the disclaimer, supporters used it to claim that the WHO endorsed acupuncture that were lacking sufficient evidence-basis. Medical scientists expressed concern that the evidence supporting acupuncture outlined in the report was weak, and Willem Betz of SKEPP (Studie Kring voor Kritische Evaluatie van Pseudowetenschap en het Paranormale, the Study Circle for the Critical Evaluation of Pseudoscience and the Paranormal) said that the report was evidence that the "WHO has been infiltrated by missionaries for alternative medicine". The WHO 2005 report was also criticized in the 2008 book Trick or Treatment for, in addition to being produced by a panel that included no critics of acupuncture, containing two major errors – including too many results from low-quality clinical trials, and including a large number of trials originating in China where, probably due to publication bias, no negative trials have ever been produced. Ernst and Singh, the authors of the book, described the report as "highly misleading", a "shoddy piece of work that was never rigorously scrutinized" and stated that the results of high-quality clinical trials do not support the use of acupuncture to treat anything but pain and nausea. Ernst also described the statement in a 2006 peer reviewed article as "Perhaps the most obviously over-optimistic overview ", noting that of the 35 conditions that the WHO stated acupuncture was effective for, 27 of the systematic reviews that the WHO report was based on found that acupuncture was not effective for treating the specified condition.

Public organizations

In 2012, the Mayo Clinic stated that, "many Western practitioners view the acupuncture points as places to stimulate nerves, muscles and connective tissue. This stimulation appears to boost the activity of your body's natural painkillers and increase blood flow."

In 1997, the American Medical Association Council on Scientific Affairs stated that, "There is little evidence to confirm the safety or efficacy of most alternative therapies. Much of the information currently known about these therapies makes it clear that many have not been shown to be efficacious. Well- designed, stringently controlled research should be done to evaluate the efficacy of alternative therapies."

Legal and political status

Main article: Regulation of acupuncture- Australia

In 2000, the Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria, Australia (CMBV) established an independent government agency to oversee the practice of Chinese Herbal Medicine and Acupuncture in the state. Acupuncturists in New South Wales are bound by the guidelines in the Public Health (Skin Penetration) Regulation 2000.

- Canada

Acupuncture is regulated in five provinces in Canada: Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland.

- France

Since 1955, the French advisory body Académie Nationale de Médecine (National Academy of Medicine) has accepted acupuncture as a treatment.

- Germany

The German acupuncture trials were a series of nationwide acupuncture trials set up in 2001 and published in 2006 on behalf of several German statutory health insurance companies due to a dispute as to the usefulness of acupuncture. The trials were considered to be one of the largest clinical studies in the field of acupuncture. As a result of the trials, acupuncture was paid for in Germany by the social insurance scheme for low back pain and osteoarthritis of the knee. but coverage was not offered for headache or migraine. However, because of the outcome of these trials, in the case of the other conditions, insurance corporations in Germany were not convinced that acupuncture had adequate benefits over usual care or sham treatments. Highlighting the results of the placebo group, researchers refused to accept a placebo therapy as efficient.

- New Zealand

Traditional/lay acupuncture is not a regulated health profession. Osteopaths have a scope of practice for Western Medical Acupuncture and Related Needling Techniques.

- United Kingdom

Acupuncturists are not a nationally regulated profession in the United Kingdom. Acupuncture practice is regulated by law in England and Wales for health and safety criteria under The Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions).

- United States

In 1996, the Food and Drug Administration reclassified acupuncture needles as a Class II medical device, meaning that "general acupuncture use" is done by licensed practitioners.

See also

- Chinese herbology

- Colorpuncture

- List of ineffective cancer treatments

- Perkinism

- Pressure point

- Susuk

Bibliography

- Aung, SKH; Chen WPD (2007). Clinical Introduction to Medical Acupuncture. Thieme Medical Publishers. ISBN 9781588902214.

- Barnes, LL (2005). Needles, Herbs, Gods, and Ghosts: China, Healing, and the West to 1848. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674018729.

- Cheng, X (1987). Chinese Acupuncture and Moxibustion (1st ed.). Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 711900378X.

- Needham, J; Lu GD (2002). Celestial Lancets: A History and Rationale of Acupuncture and Moxa. Routledge. ISBN 0700714588.

- Singh, S; Ernst, E (2008). Trick or Treatment: Alternative Medicine on Trial. London: Bantam. ISBN 9780593061299.

- Stux, G; Pomeranz B (1988). Basics of Acupuncture. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 354053072X.

- Wiseman, N; Ellis, A (1996). Fundamentals of Chinese medicine. Paradigm Publications. ISBN 9780912111445.

Notes

- ^ Singh & Ernst (2008) stated, "Scientists are still unable to find a shred of evidence to support the existence of meridians or Ch'i", "The traditional principles of acupuncture are deeply flawed, as there is no evidence at all to demonstrate the existence of Ch'i or meridians" and "Acupuncture points and meridians are not a reality, but merely the product of an ancient Chinese philosophy"

References

- ^ Adams, D; Cheng, F; Jou, H; Aung, S; Yasui, Y; Vohra, S (December 2011). "The safety of pediatric acupuncture: a systematic review". Pediatrics. 128 (6): e1575-87. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-1091. PMID 22106073.

- ^ Xu, Shifen; et al. (2013). "Adverse Events of Acupuncture: A Systematic Review of Case Reports". Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 581203. doi:10.1155/2013/581203. PMC 3616356. PMID 23573135.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Berman, Brian; Langevin, Helene; Witt, Claudia; Dubner, Ronald (29 July 2010). "Acupuncture for Low Back Pain". New England Journal of Medicine. 363 (5): 454–61. doi:10.1056/NEJMct0806114. PMID 20818865.

- ^ Liu, Gang; Ma, Hui-juan; Hu, Pan-pan; Tian, Yang-hua; Hu, Shen; Fan, Jin; Wang, Kai (2013). "Effects of painful stimulation and acupuncture on attention networks in healthy subjects". Behavioral and Brain Functions. 9 (1): 23. doi:10.1186/1744-9081-9-23. ISSN 1744-9081. PMC 3680197. PMID 23758880.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Acupuncture". NIH Consensus Statement. 15 (5): 1–34. 1997. PMID 10228456. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ^ Ernst, E; et al. (2011). "Acupuncture: Does it alleviate pain and are there serious risks? A review of reviews". Pain. 152 (4): 755–64. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.004. PMID 21440191.

- ^ "Acupuncture for Pain". NCCAM. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Ernst, E.; Pittler, MH; Wider, B; Boddy, K (2007). "Acupuncture: its evidence-base is changing". The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 35 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1142/S0192415X07004588. PMID 17265547.

- ^ Colquhoun, D; Novella S (2013). "Acupuncture is a theatrical placebo: the end of a myth" (PDF). Anesthesia & Analgesia. 116 (6): 1360–1363. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31828f2d5e. PMID 23709076.

- ^ Lee, MS; Ernst, E (2011). "Acupuncture for pain: An overview of Cochrane reviews". Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 17 (3): 187–9. doi:10.1007/s11655-011-0665-7. PMID 21359919.

- ^ Johnson, M. I. (2006). "The clinical effectiveness of acupuncture for pain relief--you can be certain of uncertainty". Acupuncture in medicine : journal of the British Medical Acupuncture Society. 24 (2): 71–79. doi:10.1136/aim.24.2.71. PMID 16783282.

- ^ Ernst, E. (2006). "Acupuncture--a critical analysis". Journal of Internal Medicine. 259 (2): 125–137. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01584.x. ISSN 0954-6820. PMID 16420542.

- ^ Madsen, M. V.; Gøtzsche, P. C; Hróbjartsson, A. (2009). "Acupuncture treatment for pain: systematic review of randomised clinical trials with acupuncture, placebo acupuncture, and no acupuncture groups". BMJ. 338: a3115. doi:10.1136/bmj.a3115. PMC 2769056. PMID 19174438.

- ^ "Acupuncture: An Introduction". NCCAM. September 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ^ Taylor P, Pezzullo L, Grant SJ, Bensoussan A. (2013). "Cost-effectiveness of Acupuncture for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain". Pain Practice: The Official Journal of World Institute of Pain. doi:10.1111/papr.12116. PMID 24138020.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Standaert CJ, Friedly J, Erwin MW, Lee MJ, Rechtine G, Henrikson NB, Norvell DC (2011). "Comparative effectiveness of exercise, acupuncture, and spinal manipulation for low back pain". Spine. 1 (36): 21 Suppl):S120–30. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31822ef878. PMID 21952184.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 72

- Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 107

- Singh & Ernst 2008, p. 387

- ^ Bauer, M (2006). "The Final Days of Traditional Beliefs? – Part One". Chinese Medicine Times. 1 (4): 31.

- ^ Ahn, Andrew C.; Colbert, Agatha P.; Anderson, Belinda J.; Martinsen, ØRjan G.; Hammerschlag, Richard; Cina, Steve; Wayne, Peter M.; Langevin, Helene M. (2008). "Electrical properties of acupuncture points and meridians: A systematic review" (PDF). Bioelectromagnetics. 29 (4): 245–56. doi:10.1002/bem.20403. PMID 18240287.

- ^ Mann, F (2000). Reinventing Acupuncture: A New Concept of Ancient Medicine. Elsevier. ISBN 0750648570.

- ^ de las Peñas, César Fernández; Arendt-Nielsen, Lars; Gerwin, Robert D (2010). Tension-type and cervicogenic headache: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 251–4. ISBN 9780763752835.

- ^ Williams, WF (2013). Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience: From Alien Abductions to Zone Therapy. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 1135955220.

- ^ Ulett, GA (2002). "Acupuncture". In Shermer, M (ed.). The Skeptic: Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience. ABC-CLIO. pp. 283–91. ISBN 1576076539.

- ^ "Hard to swallow". Nature (journal). 448 (7150): 105. 2007. doi:10.1038/448106a. PMID 17625521.

- ^ Zhang J, Shang H, Gao X, Ernst E (December 2010). "Acupuncture-related adverse events: a systematic review of the Chinese literature". Bull World Health Organ. 88 (12): 915–921C. doi:10.2471/BLT.10.076737. PMC 2995190. PMID 21124716.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ White, A.; Ernst, E. (2004). "A brief history of acupuncture". Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 43 (5): 662–663. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keg005. PMID 15103027.

- ^ "Classics of Traditional Medicine".

- ^ Robson, T (2004). An Introduction to Complementary Medicine. Allen & Unwin. pp. 90. ISBN 1741140544.

- Schwartz, L (2000). "Evidence-Based Medicine And Traditional Chinese Medicine: Not Mutually Exclusive". Medical Acupuncture. 12 (1): 38–41.

- ^ "What you can expect". Mayo Clinic Staff. January 2012.

- ^ Young, J (2007). Complementary Medicine For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 126–8. ISBN 0470519681.

- Napadow V, Kaptchuk TJ (June 2004). "Patient characteristics for outpatient acupuncture in Beijing, China". J Altern Complement Med (Research article). 10 (3): 565–72. doi:10.1089/1075553041323849. PMID 15253864.

- ^ Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, Erro J, Hrbek A, Deyo RA (2005). "The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do?". Ann Fam Med. 3 (2): 151–8. doi:10.1370/afm.248. PMC 1466855. PMID 15798042.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hicks, Angela. The acupuncture handbook: how acupuncture works and how it can help you.Piatkus Books,2005, p. 41.

- Collinge, William J. (1996). The American Holistic Health Association Complete guide to alternative medicine. New York: Warner Books. ISBN 0-446-67258-0.

- ^ Aung & Chen, 2007, p. 116.

- Ellis, A; Wiseman N; Boss K (1991). Fundamentals of Chinese Acupuncture. Paradigm Publications. pp. 2–3. ISBN 091211133X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Aung & Chen, 2007, p. 113-4.

- Loyeung, B. Y.; Cobbin, D. M. (2013). "Investigating the effects of three needling parameters (manipulation, retention time, and insertion site) on needling sensation and pain profiles: A study of eight deep needling interventions". Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013: 136763. doi:10.1155/2013/136763. PMC 3789497. PMID 24159337.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Steven Aung; William Chen (10 January 2007). Clinical Introduction to Medical Acupuncture. Thieme. p. 116. ISBN 9781588902214. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- Stephen Birch, Shonishin: Japanese Pediatric Acupuncture. Thieme, 2011. Thomas Wernicke, The Art of Non-Invasive Paediatric Acupuncture. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2014.

- Stephen Barrett (9 March 2006). "Massage Therapy: Riddled with Quackery". Quackwatch.

- Lee, Eun Jin; Frazier, Susan K (2011). "The Efficacy of Acupressure for Symptom Management: A Systematic Review". Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 42 (4): 589–603. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.007. PMC 3154967. PMID 21531533.

- Needham & Lu, 2002, pp 170–173.

- "British Cupping Society".

- Farlex (2012). "Tui na". Farlex.

- "Sonopuncture". Educational Opportunities in Integrative Medicine. The Hunter Press. 2008. p. 34. ISBN 9780977655243.

- Bhagat (2004). Alternative Therapies. pp. 164–165. ISBN 9788180612206.

- "Sonopuncture". American Cancer Society's Guide to complementary and alternative cancer methods. American Cancer Society. 2000. p. 158. ISBN 9780944235249.

- "Cancer Dictionary – Acupuncture point injection". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 27 March 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Braverman S (2004). "Medical Acupuncture Review: Safety, Efficacy, And Treatment Practices". Medical Acupuncture. 15 (3).

- Isaacs, Nora (13 December 2007). "Hold the Chemicals, Bring on the Needles". New York Times. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- ^ White, A.R.; Filshie, J.; Cummings, T.M.; International Acupuncture Research Forum (2001). "Clinical trials of acupuncture: consensus recommendations for optimal treatment, sham controls and blinding". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 9 (4): 237–245. doi:10.1054/ctim.2001.0489. PMID 12184353.

- Paterson, C.; Dieppe, P. (2005). "Characteristic and incidental (placebo) effects in complex interventions such as acupuncture". BMJ. 330 (7501): 1202–1205. doi:10.1136/bmj.330.7501.1202. PMC 558023. PMID 15905259.

- Lee A, Copas JB, Henmi M, Gin T, Chung RC (2006). "Publication bias affected the estimate of postoperative nausea in an acupoint stimulation systematic review". J Clin Epidemiol. 59 (9): 980–3. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.02.003. PMID 16895822.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Tang, JL; Zhan, SY; Ernst, E (1999). "Review of randomised controlled trials of traditional Chinese medicine". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 319 (7203): 160–1. doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7203.160. PMC 28166. PMID 10406751.

- Vickers, A; Goyal, N; Harland, R; Rees, R (1998). "Do Certain Countries Produce Only Positive Results? A Systematic Review of Controlled Trials". Controlled Clinical Trials. 19 (2): 159–66. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00150-5. PMID 9551280.

- ^ He, J; Du, L; Liu, G; Fu, J; He, X; Yu, J; Shang, L (2011). "Quality assessment of reporting of randomization, allocation concealment, and blinding in traditional Chinese medicine RCTs: A review of 3159 RCTs identified from 260 systematic reviews". Trials. 12: 122. doi:10.1186/1745-6215-12-122. PMC 3114769. PMID 21569452.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Vickers, AJ; Cronin, AM; Maschino, AC; Lewith, G; MacPherson, H; Foster, N; Sherman, N; Witt, K; Linde, C (2012). "Acupuncture for chronic pain: individual patient data meta-analysis". JAMA Internal Medicine. 12 (Suppl 1). for the Acupuncture Trialists' Collaboration: 1444–53. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3654. PMC 3373337. PMID 22965186.

- Jha, Alok (10 September 2012). "Acupuncture useful, but overall of little benefit, study shows". The Guardian.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|newspaper=(help) - Colquhoun, David (17 September 2012). "Re: Risks of acupuncture range from stray needles to pneumothorax, finds study". BMJ.

- Hopton A, MacPherson H (2010). "Acupuncture for chronic pain: is acupuncture more than an effective placebo? A systematic review of pooled data from meta-analyses". Pain Practice. 10 (2): 94–102. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2009.00337.x. PMID 20070551.

- Cao, L; et al. (2012). "Needle acupuncture for osteoarthritis of the knee. A systematic review and updated meta-analysis". Saudi Medical Journal. 33 (5): 526–32. PMID 22588814.

- Selfe, TK; Taylor, AG (2008). "Acupuncture and osteoarthritis of the knee: a review of randomized, controlled trials". Family & Community Health. 31 (3): 247–54. doi:10.1097/01.FCH.0000324482.78577.0f. PMC 2810544. PMID 18552606.

- Zhang, W; et al. (2008). "OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis, Part II: OARSI evidence-based, expert consensus guidelines" (PDF). Osteoarthritis and Cartilage. 16 (2): 137–162. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2007.12.013. PMID 18279766.

{{cite journal}}:|first10=missing|last10=(help);|first11=missing|last11=(help);|first12=missing|last12=(help);|first13=missing|last13=(help);|first14=missing|last14=(help);|first15=missing|last15=(help);|first16=missing|last16=(help) - Manheimer, E; et al. (2010). Manheimer, Eric (ed.). "Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis (Review)" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (10): CD001977. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2. PMC 3169099. PMID 20091527.

- Lee, Courtney; Crawford, Cindy; Wallerstedt, Dawn; York, Alexandra; Duncan, Alaine; Smith, Jennifer; Sprengel, Meredith; Welton, Richard; Jonas, Wayne (2012). "The effectiveness of acupuncture research across components of the trauma spectrum response (tsr): A systematic review of reviews". Systematic Reviews. 1: 46. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-1-46. PMC 3534620. PMID 23067573.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Linde, K; Allais, G; Brinkhaus, B; Manheimer, E; Vickers, A; White, AR (2009). Linde, Klaus (ed.). "Acupuncture for migraine prophylaxis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001218. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001218.pub2. PMC 3099267. PMID 19160193. Cite error: The named reference "Linde2009" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Furlan, AD; et al. (2005). Furlan, AD (ed.). "Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD001351. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001351.pub2. PMID 15674876.

- Manheimer, E; et al. (2005). "Meta-analysis: Acupuncture for low back pain" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 142 (8): 651–63. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-142-8-200504190-00014. PMID 15838072.

- Chou, R; Huffman, LH (2007). "Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: A review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline" (PDF). Annals of Internal Medicine. 147 (7): 492–504. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-147-7-200710020-00007. PMID 17909210.

{{cite journal}}:|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help) - Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, Liu JP, Shang J, Scott SW, Littlejohn G (2013). "Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 31 (5): CD007070. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007070.pub2. PMC 4105202. PMID 23728665.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lee MS, Ernst E (January 2014). "Acupuncture for surgical conditions: an overview of systematic reviews". Int. J. Clin. Pract. (Review). doi:10.1111/ijcp.12372. PMID 24447388.

- Choi, T. Y.; Lee, M. S.; Kim, T. H.; Zaslawski, C; Ernst, E (2012). "Acupuncture for the treatment of cancer pain: A systematic review of randomised clinical trials". Supportive Care in Cancer. 20 (6): 1147–58. doi:10.1007/s00520-012-1432-9. PMID 22447366.

- Paley, C. A.; Johnson, M. I.; Tashani, O. A.; Bagnall, A. M. (2011). "Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (1): CD007753. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007753.pub2. PMID 21249694.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help) - Garcia, M. K.; McQuade, J; Haddad, R; Patel, S; Lee, R; Yang, P; Palmer, J. L.; Cohen, L (2013). "Systematic review of acupuncture in cancer care: A synthesis of the evidence". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 31 (7): 952–60. doi:10.1200/JCO.2012.43.5818. PMC 3577953. PMID 23341529.

- Posadzki, P; Moon, T. W.; Choi, T. Y.; Park, T. Y.; Lee, M. S.; Ernst, E (2013). "Acupuncture for cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review of randomized clinical trials". Supportive Care in Cancer. 21 (7): 2067–73. doi:10.1007/s00520-013-1765-z. PMID 23435597.

- ^ Choi, T. Y.; Lee, M. S.; Ernst, E (2012). "Acupuncture for cancer patients suffering from hiccups: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 20 (6): 447–55. doi:10.1016/j.ctim.2012.07.007. PMID 23131378.

- Dennis, CL; Dowswell, T (31 July 2013). "Interventions (other than pharmacological, psychosocial or psychological) for treating antenatal depression". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD006795. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006795.pub3. PMID 23904069.