This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Richard-of-Earth (talk | contribs) at 05:34, 18 October 2014 (→Criticism of handling of case: This is in the reactions section). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 05:34, 18 October 2014 by Richard-of-Earth (talk | contribs) (→Criticism of handling of case: This is in the reactions section)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) For a background of the ongoing outbreak, see Ebola virus epidemic in West Africa.| This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. Feel free to improve this article or discuss changes on the talk page, but please note that updates without valid and reliable references will be removed. (October 2014) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

On September 30, 2014, the CDC announced that Thomas Eric Duncan, a 42-year-old Liberian national, had been diagnosed with Ebola virus disease in Dallas, Texas. Duncan, who had been visiting family in Dallas, was treated at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas. By October 4, Duncan's condition had deteriorated from "serious but stable" to "critical." On October 8, Duncan died of Ebola virus disease.

A second case of Ebola was diagnosed on October 11 in a nurse, Nina Pham, who had provided care to Duncan at the hospital. Nurse Amber Vinson, who also treated Duncan, became the third person diagnosed with the disease on October 14.

Background

First case

| Articles related to the |

| Western African Ebola virus epidemic |

|---|

|

| Overview |

| Nations with widespread cases |

| Other affected nations |

| Other outbreaks |

Thomas Eric Duncan was from Monrovia, Liberia, a country among those hardest hit by the Ebola virus epidemic. Duncan worked as a personal driver for the general manager of Safeway Cargo, a FedEx contractor in Liberia. According to manager Henry Brunson, Duncan abruptly quit his job on September 4, 2014, giving no reason. Brunson added he knew Duncan had family in the United States, and that Duncan's sister had come from the U.S. to visit him in the weeks before he quit. Duncan was traveling on a visa when he made his first trip to the U.S. to reunite with his estranged teenage son and the boy's mother, Louise Troh, who had been his girlfriend in Liberia.

On September 15, 2014, the family of Ebola patient Marthalene Williams were unable to summon an ambulance to transfer Williams to the hospital. Their tenant, Duncan, helped to transfer Williams by taxi to an Ebola treatment ward in Monrovia, Liberia. Duncan rode in the taxi to the treatment ward with Williams, her father, and her brother. The family was turned away due to lack of space, and Duncan helped carry Williams from the taxi back into her home, where she died shortly afterward.

On September 19, Duncan went to the airport in Monrovia, where according to Liberian officials Duncan lied about his history of contact with the disease on an airport questionnaire before boarding a Brussels Airlines flight to Brussels. In Brussels, Duncan boarded United Airlines Flight 951 to Washington Dulles Airport. From Washington, he boarded United Airlines Flight 822 to Dallas/Fort Worth. He arrived in Dallas at 7:01 p.m. CDT on September 20, 2014, and stayed with his partner and her five children, who live in the Fair Oaks neighborhood of Dallas.

Duncan began experiencing symptoms on September 24, 2014, and went to the Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital emergency room late in the evening of September 25, 2014. During this visit, the hospital reported his symptoms were a 100.1 °F (37.8 °C) fever, abdominal pain for two days, a headache, and decreased urination; but that he had no vomiting, diarrhea, or nausea at the time. The ER nurse had asked about his travel history and recorded he had come from Liberia. It was initially reported that this information was not relayed to the doctor by the hospital's electronic medical record (EMR) system, but the hospital later retracted that statement. Hospital officials also said that Duncan had been asked if he had been around anyone who had been sick, and said Duncan told them he had not. He was diagnosed with a "low-grade, common viral disease" and was sent home with a prescription for antibiotics. Medical records later retrieved by the Associated Press revealed Duncan had a fever as high as 103 °F (39 °C) during the initial visit and that he rated his pain as 8 on a scale of 1 to 10. Duncan began vomiting on September 28, 2014, and was transported the same day to the same Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital emergency room by ambulance. His Ebola diagnosis was confirmed during a CDC news conference on September 30, 2014, making Duncan the index patient for Ebola in the United States.

Up to 100 people may have had contact with those who had direct contact with Duncan after he showed symptoms. Health officials later monitored 50 low- and 10 high-risk contacts, the high-risk contacts being Duncan's close family members and three ambulance workers who took him to the hospital. Everyone who came into contact with Duncan is currently being monitored daily to watch for symptoms of the virus. The same day, a second person who had close contact with Duncan was put under close observation.

Duncan was treated at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas. As of October 4, Duncan's condition had deteriorated from "serious but stable" to "critical". Duncan was not given the experimental drug ZMapp, which was used to treat previous cases of Ebola in aid workers and medical staff, as stocks of the drug were depleted at the time of his infection. American Ebola survivor Kent Brantly offered to donate his blood to Duncan; however, their blood types were incompatible.

On October 4, Duncan began receiving the experimental drug brincidofovir, which only received an FDA emergency investigational new drug authorization for Ebola treatment on October 6. Duncan was still in critical condition at that time. The next day, the CDC announced it had lost track of a homeless man who had been in the same ambulance as Duncan. They announced efforts were underway to locate the man and place him in a comfortable and compassionate monitoring environment. Later that day, the CDC announced that the man had been found and is being monitored. On October 7, it was reported that Duncan's condition was improving. However, Duncan died at 7:51 a.m. Central Time (DST) on October 8, 2014, and became the first person to die within the United States of Ebola virus disease.

Secondary infections of health care workers

Nina Pham

On the night of October 10, a 26-year-old nurse, Nina Pham, who had treated Duncan at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital, reported a low-grade fever and was placed in isolation. On October 11, Pham tested positive for Ebola virus, becoming the first person to contract the virus in the U.S. On October 12, the CDC confirmed the positive test results. Hospital officials said Pham wore the recommended protective gear when treating Duncan on his second visit to this Dallas hospital, and she had "extensive contact" with him on "multiple occasions". Pham was in stable condition as of October 12. Although no evidence exists of dogs transmitting Ebola virus to humans, Pham's dog is being quarantined out of caution.

Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, initially blamed a breach in protocol for the infection. The hospital's chief clinical officer, Dr. Dan Varga, said all staff had followed CDC recommendations. Bonnie Costello of National Nurses United said, "You don't scapegoat and blame when you have a disease outbreak. We have a system failure. That is what we have to correct." Frieden later spoke to "clarify" that he had not found "fault with the hospital or the healthcare worker." National Nurses United criticized the hospital for its lack of Ebola protocols and guidelines that were "constantly changing." Briana Aguirre, a nurse that cared for Nina Pham, strongly criticized the hospital in a public interview. She said she and others did not receive proper training or personal protective equipment, and did not follow normal protocol for infectious diseases into the second week of the crisis.A report indicated that healthcare workers did not wear hazmat suits until Duncan's test results confirmed his infection due to Ebola, two days after his admission to the hospital. Frieden later said that the CDC could have been more aggressive in the management and control of the virus at the hospital.

Pham's infection represents the first case contracted on U.S. soil, leading Frieden to launch an investigation as to how she became infected. On October 13, Frieden urged the public to brace for more bad news, however, suggesting that there could be additional cases in coming days, particularly among the health care workers who cared for Duncan.

On October 16, Pham was transferred to a facility at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Bethesda, Maryland. She arrived at Bethesda during the night.

Amber Vinson

On October 14, a second nurse at the same hospital, identified as 29-year-old Amber Vinson, reported a fever. Vinson was among the nurses who provided treatment for Duncan and was isolated within 90 minutes of reporting the fever. By the next day, Vinson had tested positive for Ebola virus. On October 13, Vinson had flown Frontier Airlines Flight 1143 from Cleveland to Dallas, after spending the weekend in Akron, Ohio. She had a fever of 99.5 °F (37.5 °C) before boarding the 138-passenger jet, according to public health officials. Vinson had flown to Cleveland from Dallas on Frontier Airlines Flight 1142 on October 10. During a press conference, CDC Director Tom Frieden stated she should not have traveled, since she was one of the health care workers known to have exposure to Duncan. Passengers of both flights were asked to contact the CDC as a precautionary measure.

It was later discovered that the CDC gave Vinson permission to board a commercial flight to Cleveland. Before her trip back to Dallas, she called the CDC several times to report her 99.5 °F (37.5 °C) fever before boarding her flight. A CDC employee who took her call checked a CDC chart, noted that Vinson's fever wasn't 100.4 °F (38.0 °C) or higher which the CDC deemed as "high risk", and gave her permission to board the commercial flight.

On October 15, Vinson was transferred to the Emory University Hospital in Atlanta.

As a precaution, sixteen people in Ohio who had contact with Vinson were voluntarily quarantined. Flight crew members from Frontier Airlines Flight 1142 from Dallas to Cleveland were put on paid leave for 21 days.

Monitoring of other health care workers

As of October 15, 2014, there were 76 Texas Presbyterian Hospital health care workers being monitored because they had some level of contact with Thomas Duncan.

On October 16, after learning that Vinson traveled on a plane before her Ebola diagnosis, the Texas Department of State Health Services advised all health care workers exposed to Duncan to avoid travel and public places until 21 days after their last known exposure.

Containment efforts

Operation United Assistance

On September 29, the U.S. military sent 4,000 troops to West Africa to establish treatment centers. The troops are tasked with building modular hospitals known as Expeditionary Medical Support (EMEDS) systems. Plans included building a 25 bed hospital for health care workers and 17 treatment centers with 100 beds each.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) infection control protocols

US hospitals are relying on CDC protocols established in 2007 to contain Ebola. The CDC guidelines leave the selection of gear to hospitals "based on the nature of the patient interaction and/or the likely mode(s) of transmission", and suggest that wearing gowns with "full coverage of the arms and body front, from neck to the mid-thigh or below, will ensure that clothing and exposed upper body areas are protected." The guidelines also recommended masks and goggles.

According to infection control experts, several American hospitals have improperly trained their personnel to deal with Ebola patients because they were following federal guidelines that were too lax. American federal health officials effectively acknowledged problems with their procedures for protecting health care workers by abruptly changing them. Sean Kaufman, who oversaw infection control at Emory University Hospital while it treated Kent Brantly and Nancy Writebol, the first two American Ebola patients who were infected overseas, called earlier CDC guidelines “absolutely irresponsible and dead wrong.” Kaufman called to warn the agency about its lax guidelines but, according to Kauffman, “They kind of blew me off.”

A Doctors Without Borders representative, whose organization has been treating Ebola patients in Africa, criticized a CDC poster for lax guidelines on containing Ebola, “It doesn’t say anywhere that it’s for Ebola. I was surprised that it was only one set of gloves, and the rest bare hands. It seems to be for general cases of infectious disease.”

According to National Nurses United, a nursing union with 185,000 members, several hospitals ignored the lax guidelines because the CDC made them voluntary. Nurses at the Texas hospital, for example, complained that the protective gear the hospital issued them left their necks exposed. They were told to wrap their necks with medical tape. According to Frieden, the CDC is appointing a hospital site manager to oversee Ebola containment efforts and are making "intensive efforts" to retrain and supervise staff.

On October 14, the WHO reported that 125 contacts in the United States were being traced and monitored.

Airport screening

On October 12, Aileen Marty, a physician with the WHO who had spent 31 days in Nigeria, criticized the complete lack of screening for Ebola on her recent return to the United States through Miami International Airport in Miami, Florida. After the death of the Liberian national Duncan, who had been exposed to Ebola but allegedly lied about his exposure on a questionnaire before boarding a flight to the United States, President Obama announced that the government would develop expanded Ebola screening of airline passengers, but Josh Earnest speaking for the White House stated a travel ban to West Africa was not under consideration as it would make it more difficult to send help to control the epidemic.

The process of screening airplane passengers for fever, as well as the issuance of Ebola questionnaires, is to be implemented at five U.S. airports, which take more than 94% of the passengers from Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, the three countries that are hit heavily with Ebola. These airports are John F. Kennedy International Airport (Queens, New York); Newark Liberty International Airport (Newark, New Jersey); O'Hare International Airport (Chicago, Illinois); Washington Dulles International Airport (Dulles, Virginia); and Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport (Atlanta, Georgia). Although no plans have been announced for other airports, screening in the U.S. represents a second layer of protection since passengers are already being screened upon exiting these three countries. However, the risk can never be totally eliminated.

School closures

On October 16, two schools in the Solon City School District near Cleveland were closed after they learned that one of their teachers may have been on the same aircraft (but not the same flight) as Amber Vinson. The schools were closed so that disinfection procedures could be carried out. One school in the Cleveland Metropolitan School District was disinfected overnight due to similar concerns but remained open, school officials said that they had been assured by city health officials that there was no risk, and that that the disinfection was "strictly precautionary". Three schools in the Belton Independent School District in Belton, Texas were also closed. Infectious disease experts considered these closures to be an overreaction, and were concerned that it would frighten the public into believing that Ebola is a larger danger than it actually is.

In October 2014, Navarro College received media attention for admission rejection letters sent to two prospective students from Nigeria. The letters informed the applicants that the college was "not accepting international students from countries with confirmed Ebola cases." Nigeria was identified by the World Health Organization through the summer of 2014 with multiple confirmed cases of Ebola, but there had been no new Ebola cases "in more than 21 days" (since early September). The rejected applicants lived in Ibadan, Nigeria, approximately 80 miles from Lagos, where the most recent infected cases were identified. The college offered an explanation on October 13, stating that that the rejections were not a result of fears of Ebola, but that its international department had recently been restructured to focus on recruiting students from China and Indonesia. On October 16, Navarro's Vice-President Dewayne Gragg, issued a new statement, contradicting the previous explanation, and confirming that there had indeed been a decision to "postpone our recruitment in those nations that the Center for Disease Control and the U.S. State Department have identified as at risk."

Calls for suspension of visas

Congressional leaders, including the chairs of the House Foreign Relations Committee, and the House Homeland Security Committee, called on the Secretary of State to suspend issuing visas to travelers from the affected West African countries which include Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea.

| This article may lack focus or may be about more than one topic. Please help improve this article, possibly by splitting the article and/or by introducing a disambiguation page, or discuss this issue on the talk page. |

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases director Anthony Fauci said on October 6 that "discussion is underway" and "all options are being looked at." Fauci said that clear-cut screening was going on at the exit end, referring to the Ebola-affected countries' practice of screening outbound passengers before they leave. The U.S. discussion, he said, centered on "what kind of screening you do on the entry end. That's something that's on the table now."

On October 16, 2014, in a United States Congressional hearing regarding the Ebola virus crisis, Dr. Fauci testified that drug companies were working on a vaccine but that clinical trials were still a long way off. Fauci further testified that the NIH had the capacity to care for two patients at their containment unit, and that Nina Pham would occupy one of those beds.

Travel ban on contact cases

On 17 October the Texas health officials ordered all health care workers who entered Thomas Eric Duncan's isolation ward or had contact with his specimens not to use public transport to travel. The ban, to be in effect for 21 days, also includes visiting public places, i.e., theaters, movies, and restaurants. This restriction applies to more than 70 health care workers. This development follows the news that a nurse who was tested positive for the disease traveled by plane shortly after caring for Duncan. Another healthcare worker who handled fluid specimens from Duncan was reported to be on a cruise line in the Caribbean. She is currently in isolation on board. The person shows no symptoms of being infected but reported a low grade fever. Attempts to airlift her due to safety concerns have been denied to date.

Appointment of an Ebola response coordinator

In October 2014, President Barack Obama appointed Ron Klain as the "Ebola response coordinator" (or, less officially, Ebola "czar") of the United States. Klain is a lawyer who previously served as Joe Biden's and Al Gore's chief of staff. At the time of his appointment, Klain did not have medical or health care experience. After previous criticism, Obama said, "It may make sense for us to have one person ... so that after this initial surge of activity, we can have a more regular process just to make sure that we're crossing all the T's and dotting all the I's going forward". Klain will report to White House Homeland Security Adviser Lisa Monaco and National Security Advisor Susan Rice.

Reactions

US President Barack Obama, Remarks by the President on the Ebola Outbreak, September 16, 2014."First and foremost, I want the American people to know that our experts, here at the CDC and across our government, agree that the chances of an Ebola outbreak here in the United States are extremely low."

On October 2, Liberian authorities said they could prosecute Duncan if he returned because he had filled out a form before flying falsely stating he had not come into contact with an Ebola case. Liberian President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf told the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation she was angry with Duncan for what he had done, especially given how much the United States was doing to help tackle the crisis: "One of our compatriots didn't take due care, and so, he's gone there and in a way put some Americans in a state of fear, and put them at some risk, and so I feel very saddened by that and very angry with him.…The fact that he knew (he might be a carrier) and he left the country is unpardonable, quite frankly." Before his death, Duncan claimed that he did not know at the time of boarding the flight that he had been exposed to Ebola.

Joined with Rev. Jesse Jackson at his Rainbow Push headquarters, Duncan's family called the care Duncan received was at best 'incompetent' and at worst 'racially motivated.' Jackson questioned the hospital's motives, saying “What role did lack of privilege play in the treatment he received? He is being treated as a criminal rather than as a patient.” Family members said they are considering legal action against the hospital where Duncan received treatment. In response, Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital issued a statement, "Our care team provided Mr. Duncan with the same high level of attention and care that would be given any patient, regardless of nationality or ability to pay for care. We have a long history of treating a multicultural community in this area."

The United States federal government told American citizens not to worry about an epidemic of Ebola in the United States, stating that the risk of such an epidemic was very low. On Twitter on September 30, over 50,000 tweets in response to the Ebola case were posted in one hour.

Medical evacuations to the U.S.

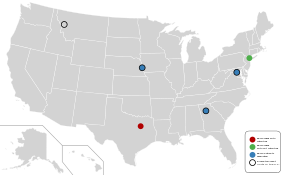

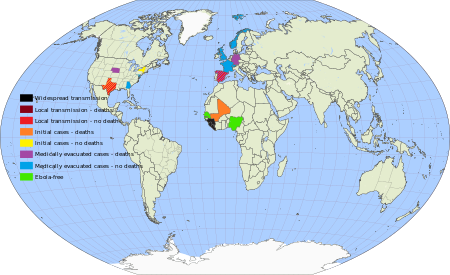

• Maryland, Nebraska and Georgia are in blue, indicating medically evacuated cases with no deaths.

• Texas is in lighter red, indicating local transmission with no deaths, and orange, indicating an initial case that led to an Ebola death.

As of October 6, 2014, five Americans have been evacuated to the U.S. for treatment after contracting Ebola in West Africa. Kent Brantly, a physician and medical director in Liberia for the aid group Samaritan's Purse, and co-worker Nancy Writebol were infected while working in Monrovia. Both were flown to the United States at the beginning of August for further treatment in Atlanta's Emory University Hospital. On August 21, Brantly and Writebol recovered and were discharged.

On September 4, a Massachusetts physician, Rick Sacra, was airlifted from Liberia to be treated in Omaha, Nebraska at the Nebraska Medical Center. Working for Serving In Mission (SIM), he is the third U.S. missionary to contract EVD. He thinks he probably contracted Ebola while performing a caesarean section on a patient who had not been diagnosed with the disease. While in hospital, Sacra received a blood transfusion from Kent Brantly, who had recently recovered from the disease. On September 25, Sacra was declared Ebola-free and released from the hospital.

On September 9, the fourth U.S. citizen who contracted the Ebola virus arrived at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta for treatment. The identity of the patient, a doctor working for the WHO in Sierra Leone, was not released. On October 16, he released a statement saying he has improved and expects to be discharged in the near future. He was scheduled to receive a blood or serum transfusion from a British man who had recently recovered from the disease. In addition, on September 21, a CDC employee was flown back to the United States after low risk exposure with a healthcare worker. Currently, he shows no symptoms and is being monitored. The CDC announced he poses no risks to his family or the United States. On September 28, a fourth American doctor was admitted to National Institutes of Health hospital.

On October 2, NBC News photojournalist Ashoka Mukpo, covering the outbreak in Liberia, tested positive for Ebola after showing symptoms. Four other members of the NBC team, including physician Nancy Snyderman, were being closely monitored for symptoms. Mukpo was evacuated on October 6 to the University of Nebraska Medical Center for treatment in their isolation unit.

Biocontainment units

There are four specialized biocontainment units in the United States: the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska, where Mukpo and Sacra were treated; the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland; St. Patrick Hospital and Health Sciences Center (Missoula, Montana); and Emory University Hospital (Atlanta, Georgia), where Brantley, Writebol and the unnamed patient had gone after contracting Ebola.

See also

- Ebola virus epidemic in Guinea

- Ebola virus epidemic in Liberia

- Ebola virus epidemic in Nigeria

- Ebola virus epidemic in Sierra Leone

- List of Ebola outbreaks

Notes

- These people will show symptoms and have other high risk factors indicating a greater probability of Ebola infection.

- These people may have had direct contact with Duncan after he started showing symptoms. Includes one homeless man found on October 5, 2014.

- These people may have had contact with people who may have had direct contact with Duncan.

References

- "Who are the American Ebola patients?", CNN, October 6, 2014

- "Ebola ruled out for 2 patients in isolation at D.C.-area hospitals; 1 has malaria", ABC News, October 4, 2014

- "Dallas Ebola Family Joins Long History of Quarantines", NBC News, October 4, 2014

- ^ "Found: Homeless Man Sought in Ebola Case Being Monitored". NBC News. October 5, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- "C.D.C. Reviewing Procedures After New Case of Ebola in Dallas", New York Times, October 13, 2014

- CDC confirms first ever Ebola case in United States, cdc.gov; accessed October 9, 2014.

- Thomas Eric Duncan profile, nytimes.com; accessed October 9, 2014.

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/02/us/after-ebola-case-in-dallas-health-officials-seek-those-who-had-contact-with-patient.html?_r=0 Cite error: The named reference "nyt 20141002-1" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- "Thomas Eric Duncan: From healthy to Ebola". WYFF4. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "First US Ebola case Thomas Duncan 'critical'". BBC News. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- ^ "Texas Ebola patient dies". CNN. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ Fernandez, Manny (October 12, 2014). "Texas Health Worker Tests Positive for Ebola". New York Times. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "Ebola outbreak: Second Texas health worker 'tests positive'". BBC News. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Liberia says Dallas Ebola patient lied on exit documents". October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/02/world/africa/ebola-victim-texas-thomas-eric-duncan.html?_r=0

- "Ebola patient Thomas Eric Duncan's story of love and loss". Yahoo News. October 9, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- "BBC News - Ebola crisis: Outbreak death toll rises to 4,447 says WHO". BBC News.

- Thomas Eric Duncan timeline, nytimes.com; accessed October 8, 2014.

- "Ebola Patient in Dallas Lied on Screening Form, Liberian Airport Official Says", New York Times, October 2, 2014

- "History ✈ United #822 ✈ FlightAware". FlightAware. Retrieved October 2, 2014.

- "Thomas Eric Duncan: From healthy to Ebola". WYFF4. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Dallas Man Tells of U.S. Ebola Patient's Decline". WSJ. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2014/10/01/us/retracing-the-steps-of-the-dallas-ebola-patient.html?_r=0

- "Scarier Than Ebola: Human Error". BusinessWeek. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Liberia, U.S. Hospital Both Say Ebola Patient Lied About Exposure". NPR.org. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- "Texas Ebola patient told hospital of travel from West Africa but was released". Washington Post. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Ebola Patient First Sent Home From ER With 103-Degree Fever". CBS DFW. October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- "Electronic-Record Gap Allowed Ebola Patient to Leave Hospital". Bloomberg. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Dallas hospital says Ebola patient denied being around sick people". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Ebola in the US - Ebola in Dallas - 2014 Ebola Outbreak". 2014 Ebola Outbreak. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Maggie Fox. "How Did The Ebola Patient Escape for Two Days?". NBC News. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Cases of Ebola Diagnosed in the United States". CDCP. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "10 people at 'high risk' for Ebola as 50 people monitored daily after contact with Dallas Ebola patient". New York Daily News. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Hospital: Dallas Ebola patient in critical condition". CNN. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- Marjorie Owens, WFAA-TV, Dallas-Fort Worth (October 1, 2014). "Officials: Second person being monitored for Ebola". Retrieved October 1, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "First US Ebola case Thomas Duncan 'critical'". BBC News. October 4, 2014. Retrieved October 4, 2014.

- Boseley, Sarah (October 1, 2014). "First Ebola patient diagnosed in US won't be treated with ZMapp". The Guardian. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- "Error in Dallas may have exposed others to Ebola, CDC chief says". Los Angeles Times. October 13, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- "Dallas Ebola Patient Receives Experimental Drug". The Huffington Post. October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Chimerix Announces Emergency Investigational New Drug Applications for Brincidofovir Authorized by FDA for Patients With Ebola Virus Disease". Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "'We can stop Ebola in the US': CDC and Texas health officials say disease is under control but admit they have LOST one of the people who rode in ambulance that carried infected patient". Mail Online. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- "Dallas Ebola Patient Improves Slightly". TIME.com. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- "Texas Ebola Patient Thomas Eric Duncan Has Died". ABC News. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "Ebola: Texas nurse tests positive". CNN. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "CDC Test Confirms Dallas Caregiver Positive for Ebola". NBC News. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- Ebola: Health care worker tests positive at Texas hospital. BBC News October 12, 2014.

- "Dog of Dallas Nurse with Ebola to Be Kept in Safe Place". Wall Street Journal. October 13, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- "CDC confirms second Ebola case in Texas. Health worker wore 'full' protective gear". Washington Post. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

- "U.S. CDC head criticized for blaming 'protocol breach' as nurse gets Ebola", Chicago Tribune, October 13, 2014.

- "Fort Worth Alcon worker exposed to Ebola". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- "Nurses' union slams Texas hospital for lack of Ebola protocol". CNN. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- Lauer, Matt. "Dallas nurse Briana Aguirre". www.today.com. ABC. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- "Second Health Care Worker With Ebola Was In Isolation Within 90 Minutes: Official". Huffington Post. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- ^ "CDC head says more health care workers could have Ebola, despite claiming ‘any hospital’ can handle virus", Fox News, October 13, 2014

- "2nd Ebola Case in U.S. Stokes Fears of Health Care Workers", New York Times, October 12, 2014.

- "Nurse with Ebola heads to Maryland for care". USA Today. October 16, 2014.

- Lettis, George (October 17, 2014). "Ebola patient to be in high-level containment at NIH". WBAL-TV. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Second Ebola-infected nurse ID'd; flew domestic flight day before diagnosis". Fox News. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Second Health Care Worker Tests Positive for Ebola". Texas Department of State Health Services. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Health-care worker with Ebola flew on commercial flight a day before being diagnosed". Washington Post.

- "Dallas nurse with Ebola should not have been traveling: CDC". New York Post. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "CDC and Frontier Airlines Announce Passenger Notification Underway - Media Statement - CDC Online Newsroom - CDC".

- "The Second Ebola Nurse Was On Commercial Flights And Now The CDC Is Looking For The Other Passengers". Business Insider. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Health-care worker with Ebola visited family in Summit County, traveled to Dallas from Cleveland". www.ohio.com. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Ebola nurse got CDC OK for Cleveland trip". October 15, 2014.

- "CDC: Ebola Patient Traveled By Air With "Low-Grade" Fever".

- "Second Nurse With Ebola Arrives at Emory". ABC News. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2014.

- "Amber Joy Vinson's stepfather under strict Ebola quarantine, 16 Ohioans had contact with Vinson". cleveland.com. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- JACK HEALY, SABRINA TAVERNISE and ABBY GOODNOUGH (October 16, 2014). "Obama May Name 'Czar' to Oversee Ebola Response". New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Ebola outbreak in the U.S., by the numbers". NJ.com.

- "Movement of Persons with Possible Exposure to Ebola". Texas Department of State Health Services. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "The U.S. military's new enemy: Ebola. Operation United Assistance is now underway". Washington Post.

- ^ "With Ebola cases, CDC zeros in on lapses in protocol, protective gear". latimes.com. October 15, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "Element IV: Personal Protective Equipment". Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/us/lax-us-guidelines-on-ebola-led-to-poor-hospital-training-experts-say.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/us/lax-us-guidelines-on-ebola-led-to-poor-hospital-training-experts-say.html

- http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/16/us/lax-us-guidelines-on-ebola-led-to-poor-hospital-training-experts-say.html

- WHO: WHO: EBOLA RESPONSE ROADMAP UPDATE-15 October 2014

- procedrticle-2790154/w-h-o-doctor-warns-future-ebola-outbreaks-drastic-changes-aren-t-check-travelers.html "W.H.O. doctor warns of future Ebola outbreaks if drastic changes aren't made to check travelers". The Daily Mail. October 12, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help) - Stanglin, Doug. "Liberia says Dallas ebola patient lied". USA Today. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "U.S. working on new screenings for Ebola but no travel ban". Reuters. October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - "U.S. to Begin Ebola Screenings at 5 Airports". The New York Times. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - "U.S. to Screen Passengers From West Africa for Ebola at 5 Airports". Time. October 8, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|work=(help); Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Karen Matthews (October 11, 2014). "Stepped-up Ebola screening starts at NYC airport". AP.org. Retrieved October 12, 2014.

'Already there are 100 percent of the travelers leaving the three infected countries are being screened on exit. Sometimes multiple times temperatures are checked along that process,' Dr. Martin Cetron, director of the Division of Global Migration and Quarantine for the federal Centers of Disease Control and Prevention, said at a briefing at Kennedy. ... The screening will be expanded over the next week to New Jersey's Newark Liberty, Washington Dulles, Chicago O'Hare and Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta.

{{cite news}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 357 (help) - WKYC Staff (October 16, 2014). "Solon closes two schools Thursday as Ebola precaution". wkyc.com. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- Kara Sutyak (October 16, 2014). "Ebola precautions taken at Cranwood School in Cleveland". fox8. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- "Ohio, Texas schools close amid Ebola scare". USA Today. October 16, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

Three Central Texas schools were closed Thursday over health concerns surrounding two students who traveled on a Monday flight with Vinson.

- ^ Dan Mangan. "Texas College Rejects Nigerian Applicants, Cites Ebola Cases - NBC News". NBCNews.com. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Navarro College in Texas apologizes after rejecting Nigerian applicants over Ebola fears - The Washington Post". Washington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Are the Ebola outbreaks in Nigeria and Senegal over? Ebola situation assessment". World Health Organization. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Navarro College says in a new statement it will postpone recruitment of students from countries at risk for Ebola - Corsicana Daily Sun: Local News". Corsicana Daily Sun. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Lawmakers call to halt visas to travelers from Ebola-infected nations". Fox News.

- Bart Jansen (October 15, 2014). "Republicans call for West Africa travel ban to curb Ebola". USA Today.

- "Officials eyeing additional screening for Ebola in US, vow to protect citizens from disease". Associated Press. October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014..

- Roberts, Dan (October 16, 2014). "Ebola CDC director warns Ebola like 'forest fire' as Congress readies for hearing". The Guardian.

- "Dallas nurse Nina Pham will be transferred to NIH facility in Bethesda, Md". Washington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Travel ban for Texas health care workers in Ebola case". USA Today. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Kuhnhenn, Jim (October 17, 2014). "President Obama appoints Ebola 'czar'". AP News. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Obama's New Ebola 'Czar' Does Not Have Medical, Health Care Background". CBS DC. October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Davis, Julie Hirschfeld; Shear, Michael D. (October 17, 2014). "Ron Klain, Chief of Staff to 2 Vice Presidents, Is Named Ebola Czar". New York Times. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Loney, Jim. "Obama appoints Ebola czar; Texas health worker isolated on ship". Reuters. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Tapper, Jake. "First on CNN: Obama will name Ron Klain as Ebola Czar". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Lavender, Paige (October 17, 2014). "Obama To Appoint Ron Klain As Ebola Czar". The Huffington Post. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- Remarks by the President on the Ebola Outbreak. Retrieved 2014-10-12.

- "Liberia to Prosecute Man Who Brought Ebola to United States". NBC News. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Liberian President criticizes Ebola patient in Dallas - CNN.com". CNN. October 2, 2014. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Before his death, Duncan said he mistook Ebola case in Liberia for miscarriage; never lied". CNN. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- "Ebola Outbreak and Outcry: Saving Thomas Eric Duncan". The Huffington Post. October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Family of Thomas Eric Duncan says his death from Ebola is 'racially motivated'". WGN-TV. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- "Dallas' Ebola patient waited days for experimental drug - CNN.com". CNN. October 7, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- September 30, 2014. "White House Urges Calm After First Confirmed U.S. Ebola Case". Time (magazine). Retrieved October 3, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Selk, Avi (October 8, 2014). "1st Ebola diagnosis in the United States: Should we worry?". Dallas News. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- ^ "Journalist With Ebola Being Evaluated at US Hospital", Voice of America, October 6, 2014.

- "Two Americans Stricken With Deadly Ebola Virus in Liberia". July 28, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- "Ebola outbreak: U.S. missionary Nancy Writebol leaves Liberia Tuesday". August 4, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- "Ebola drug likely saved American patients". CNN.com. August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- Steenhuysen, Julie. "Ebola patient coming to U.S. as aid workers' health worsens". MSN News. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- "American Ebola doc: 'I am thrilled to be alive'". Retrieved August 21, 2014.

- "A Third US missionary with Ebola virus leaves Liberia". The Telegraph. September 5, 2014. Retrieved September 5, 2014.

- "American Doctor With Ebola Is 'Grateful' Following Release From Hospital". ABC News. September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- publisher=Washington Post "Little mentioned patient at Emory expects to be discharged very soon free from the Ebola virus". October 15, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check|url=value (help); Missing pipe in:|url=(help) - "Ebola patient arrives at Atlanta hospital". WCVB Boston. September 9, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- "British Ebola survivor flies to United States for blood donation". Reuters. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- "2014 Ebola Outbreak in West Africa-September 25, 2014". CDC. September 25, 2014. Retrieved September 28, 2014.

- Maggie Fox. "Possible Ebola Patient Arrives at U.S. NIH Lab". NBC News. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ "US Journalist Believes He Got Ebola While Cleaning Infected Car", ABC News, October 6, 2014

- "US cameraman tests positive for Ebola". News24. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- Rob Chaney. "St. Patrick Hospital 1 of 4 sites in U.S. ready for Ebola patients". Missoulian.com. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

External links

- Ebola: How it spreads

- What gear to wear for protection from Ebola infection

- Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever — CDC.gov

- U.C. Santa Cruz Ebola genome browser

| Filoviridae | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ebolavirus |

| ||||||||||||||

| Marburgvirus |

| ||||||||||||||

| Cuevavirus |

| ||||||||||||||

| Dianlovirus |

| ||||||||||||||

| Striavirus |

| ||||||||||||||

| Thamnovirus |

| ||||||||||||||