This is an old revision of this page, as edited by Rationalobserver (talk | contribs) at 22:57, 9 January 2015 (→Early life and vision: c/e). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 22:57, 9 January 2015 by Rationalobserver (talk | contribs) (→Early life and vision: c/e)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)

| Irataba | |

|---|---|

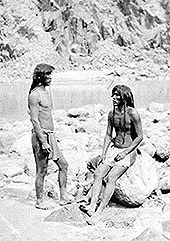

February 1864 (artist's rendering) February 1864 (artist's rendering) | |

| Mohave leader | |

| Preceded by | Cairook |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1814 Arizona |

| Died | June 17, 1878 Colorado River Indian Reservation |

| Cause of death | Uncertain |

| Known for | Irataba was the last independent chief of the Mohaves |

Irataba (from Eechee Yara Tev; c. 1814 – June 17, 1878) was the last independent chief of the Mohave Nation of Native Americans. He was born c. 1814 near the Colorado River in present-day Arizona.

As a youth, Irataba dreamed that he would one day become chief of the Mohave people, and that in his lifetime the tribe would experience great change. The second part of his vision came to fruition in 1839, when he and the Mohave Chief Cairook encountered a large group of European Americans, led by Lieutenants Amiel Whipple and J.C. Ives, who were in search of a water-route to the Pacific Ocean. The first part of his vision was realized in 1859, when, following Cairook's death in captivity, he was made principle chief of the Mohave Nation.

In 1864, Irataba traveled to Washington, D.C. for an official visit with members of the United States military and its government, including President Abraham Lincoln. During Irataba's stay he toured New York City and Philadelphia, and enjoyed great acclaim along the way; Americans lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs, and Lincoln gave him a silver-headed cane. When the tour ended, he returned home to report what he had seen, but the Mohave did not believe his fantastic story, and they subsequently mocked him mercilessly. He died ten years later in relative disgrace, though his tribe had accepted that his vision became reality. The Mohave never replaced Irataba as head chief; he was their last, and was given full traditional respect upon his passing in 1878.

Early life and vision

Irataba, from Eechee Yara Tev, meaning "beautiful bird", also known as Irateba, Arateve, and Yaratev, was born into the Neolge, or Sun Fire clan of Mohave Native Americans c. 1814. He was raised in present-day Arizona, near the Nevada and California border, on the east bank of the Colorado River in the Mohave Valley, and in the shadow of a group of sharply pointed rocks known as the Needles, located south of where the Grand Canyon empties into the Mohave Canyon. The Mohave Desert stretches for miles to the west, but as a child he did not venture into the unforgiving wilderness.

Irataba excelled at archery, hunting game such as rabbits and deer in the mountains to the east. In the spring, when the volume of the Colorado River was increased by snowmelt from the neighboring mountains, flooding the bottomlands, he helped his tribe cultivate corn, melons, beans, and pumpkins. In an effort to alleviate the intense heat of summer, he covered his body with river mud, which also helped to keep insects away, and conserved energy by resting in a thatched hut made from willow branches known as a ramada.

The Mohave people hold dreams, or visions, in high regard, and Irataba is known in their culture for having had an important one that is also considered their people's "saddest". One night, while still a youth, he dreamed that he would one day become chief of the Mohave, and that this period would be marked by what the Dream Person described as, "new things and strange things that no other Mohave" had experienced. Irataba was instructed that he should "never be afraid of them", for only in this way could he "become a mighty chief".

Adulthood

—Daily Evening Bulletin, December 2, 1863is a big Indian, literally as well as figuratively ... granitic in appearance as one of the Lower Coast mountains, with a head only less in size to a buffalo's and a lower jar massive enough to crush nuts or quartz.

According to author Frank Waters, Mohave men were extraordinary in stature, with Chief Cairook reaching a barefoot height of nearly six and a half feet. By adulthood, Irataba had grown almost as tall as Cairook, becoming "his most trusted sub-chief".

The Mohave were fierce warriors who often battled against the Chemehuevi, a neighboring tribe that regularly made trips up the Colorado River to pillage the Mohave's food stores. They were also in frequent conflict with several tribes of the Colorado Plateau, including the Paiute, Hualapai, Yavapai, and Havasupai peoples. Irataba accompanied Mohave war parties as a bowman tasked with inflicting damage on an approaching group and keeping them "at bay" in preparation for melee attacks by warriors brandishing war clubs capable of crushing their opponent's skulls "like ripe pumpkins". They considered themselves "masters" of the Colorado River, victoriously shouting Ahotka, which means good or great, as their frightened enemies retreated in haste.

Contact with European Americans

In 1849, Irataba and the Mohave people encountered a large group of European Americans, led by Lieutenants Amiel Whipple and J.C. Ives, who had made their way down the Colorado River in search of a water-route to the Pacific Ocean. The expedition party included horses, mules, and wagons that the Mohave perceived as the "new and strange things" that Irataba's dream had foretold many years earlier. The group's interpreter informed the Mohave that they needed help crossing the river, and Irataba and others obliged, first bringing a rope across with which they towed the party's packs on rubber pontoons before driving the wagons, horses, and mules to the opposite bank.

The survey party then asked the Mohave to guide them across the desert, promising gifts in exchange for their services. Cairook and Irataba agreed, and they escorted the group across the hostile territory of the Paiute to the Old Spanish Trail that would take them to southern California. When they parted ways, Ives thanked Irataba, promising to remember how he had "been a great help to white people".

In 1858, the Mohave encountered an expedition led by Edward Fitzgerald Beale that was tasked with establishing a trade route along the 35th parallel from the Rio Grande to the Colorado River. The wagon trail began at Fort Smith, Arkansas and continued through Fort Defiance, Arizona, before crossing the Colorado. Irataba again helped the European Americans, and Beale named the location where they crossed the river, en route to California, Beale's Crossing. Months later, as winter approached, a look-out stationed high on a cliff downriver in the Mohave Canyon alerted the tribe to what Waters described as a "preposterous sight", a paddle steamer spewing black smoke and blowing a shrill air whistle. When the boat stopped and several white men came ashore trading plant seeds and beads for corn and beans, Irataba realized that their leader was Lieutenant Ives, who had several years earlier promised to remember him. Ives was leading an expedition to the Grand Canyon in a steamship named the Explorer, and he asked Irataba to join them as a guide. Though the "Big Canyon" was considered "mysterious" and the territory of the Hualapais, Irataba agreed and invited a Mohave boy named Nahvahroopa to join them.

Exploring the Grand Canyon

Irataba guided the party from the Explorer's deck, indicating the location of sandbars and rapids and advising the ship's pilot regarding convenient places to anchor while resting for a night. As the expedition progressed, the rapids grew in strength and intensity, and the rock walls increasingly towered above them. When they reached the entrance to the Black Canyon of the Colorado, the Explorer crashed against a submerged rock, throwing several men overboard, dislodging the ship's boiler, and severely damaging its wheelhouse. Ives implored, "take to the skiff before she sinks."

The crew quickly set up camp on shore, but immediately realized that they had salvaged only a small portion of their corn and bean supply. Irataba volunteered to go back to the Mohave village and secure more food, warning that the expedition was being watched by Paiutes. When he returned several days later with a pack train carrying provisions, he remembered that the Dream Person had instructed him "to be afraid of nothing", and so he continued with the group into the unknown wilderness of the Grand Canyon. There they encountered several friendly Hualapais who agreed to guide them east toward Fort Defiance. Irataba was reluctant to venture deeper into the canyon, concerned that the party would get ambushed by Paiutes aligned with Mormons, as he advised: "many whites live with the Paiutes". And so, with his services no longer needed, he returned home to the Mohave.

Turning point

Upon his return, Irataba found Chief Cairook uneasy about his tribe's willingness to help the white explorers, who he distrusted. Cairook's apprehension had been building for several months, and he decided to call a meeting of his sub-chiefs to discuss the situation. He expressed concern that many white men were coming from both the south and east, and because their paths intersected in the Mohave's ancestral homeland, "our peace is broken. What shall we do being masters of the Colorado?"

The sub-chiefs remained silent, and so Cairook continued, "I say this. Let the white men find a crossing above or below. Not here. When they come next, we shall stop them." He believed that the "signs" supported his decision, and he instructed the tribe's medicine men, the hota, to make stone circles on the routes that the white men used to magically impede their progress. He also spoke of a recent dream that featured a "great star of fire, with a blazing tail. It is a star of war, a star of blood. What do you say?" Irataba, who was sympathetic to the whites, said nothing, but he understood well what the unspoken consensus meant for the tribe's future relations with European Americans.

Rose party massacre

In late 1858, a large wagon train became the first to traverse the 35th parallel route to Mohave country. A wealthy farmer from Iowa, Leonard John Rose, had assembled the train with his family of seven, his foreman's family, and several others that he hired as caretakers of a stallion named Black Morrill, twenty-four trotting horses that he hoped to breed in California, and 200 head of red Durham cattle. After two months on the Great Wagon Trail, they reached Albuquerque, New Mexico, where eight families and their livestock joined the group before they made the journey to the Colorado, still two months away.

When the Rose party reached the Colorado River, much of the group remained on a ridge while Rose and several others continued to Beale's Crossing, where they built rafts and watered their livestock in preparation for the arduous trek across the desert. They paused at mid-day to make lunch and soon afterward were attacked by a large group of Mohaves. Several white men were felled by arrows and clubs, as the woman frantically fled with the children to the protection offered by their covered wagons. Nonetheless, three children were killed during the attack. The Mohave warriors then turned their attention to the animals drinking at the river, killing Black Morrill as the stallion lurched at them. The onslaught continued for several hours, until Rose and what remained of the attacked group sneaked back to the ridge and joined the others. In all, eight people had been killed and thirteen wounded; of the train's three hundred livestock, only eight horses and a dozen cattle remained. With the wounded in one wagon, the children in another, and the healthy adults on foot, the group began their "torturous journey back to Albuquerque", during which they observed "a great star on fire, racing across the dark sky with a blazing trail".

Fort Mohave

By December 1858, news of the massacre had reached the west, and Colonel William Hoffman and fifty dragoons were dispatched from California to cross the desert and confront the Mohave, who immediately attacked and repelled the force. Hoffman returned in April 1859, by way of Fort Yuma, with seven companies of infantry and 400 pack animals. When they arrived at Beale's Crossing, which was still littered with wagon parts and human bones, 300 Mohave warriors were waiting for them, but were reluctant to attack the imposing army. Hoffman arranged for a meeting between he and his officers and Cairook and his sub-chiefs, with interpreters translating from English to Spanish to Yuman and Mohave and vice versa.

Hoffman demanded that the Mohave agree to never again harm white settlers along the wagon trail, and he ordered that a fort be built at Beale's Crossing to enforce the decree. When he asked which chief had ordered the attack on the Rose party, Cairook proudly admitted, "it was I". Hoffman then declared that, as punishment for the Rose massacre, the Mohave were required to surrender three chiefs and six prominent leaders to the US Army. Cairook offered himself as a hostage, and he and eight others were chained and transported downriver to Fort Yuma. Most of the soldiers remained to begin construction on Fort Mohave. After its completion, Irataba and his most ardent supporters moved to the Colorado River Valley, where in 1865 the Colorado River Indian Reservation was established.

Death of Cairook

In June 1859, one of the men taken prisoner by the US Army escaped and made his way back to the Mohave. He informed Irataba that Cairook had been killed by a soldier while trying escape the miserable conditions of the prison, which amounted to a small hut that left them exposed to the desert's harsh elements. As word of the chief's death spread throughout the village, people began to gather at Irataba's ramada. A tribal spokesman told him that, in keeping with Mohave tradition, Cairook's home and belongings had been burned, and that he was now their rightful leader; Irataba agreed, stating: "It is as I dreamed. I will be your chief."

With as many as 9,000 warriors in his command, Irataba quickly earned a reputation for just leadership, and Americans in the region respectfully referred to him as "Chief of the Mohaves, the great tribe of the Colorado Valley". In 1862, Irataba acted as a guide for the Walker Party Exploration, led by Joseph R. Walker and including Jack Swilling, who would later found Phoenix, Arizona. They came in search of gold, and were brought to a river that Irataba called Hasyamp, later officially named Hassayampa River, where they found plentiful amounts of the precious metal. Arizona's first mining district was established there the following year, which led to the founding of Prescott, Arizona soon afterward. During this period, relations between the Mohave and European Americans were positive; however, as white emigration increased, gold seekers founded a town nearby named La Paz, stirring tensions among the Mohave and building fear of an uprising against further encroachment on their land. Longtime guide and scout John Moss remarked, "Irataba's influence is keeping peace along the river and is of more value than a regiment of soldiers ... Let's take him to Washington and impress upon him the numbers and strength of the white man." Irataba agreed to go, and Moss arranged the trip.

Trip to Washington D.C.

Irataba traveled with Moss to Los Angeles, California, where they boarded a steamship named the Senator, bound for San Francisco. The Mohave Chief had been dressed in a "civilized costume" that included a black suit and white sombrero, and was subsequently met with great exaltation.

In January 1864, they sailed for New York City, by way of the Isthmus of Panama, on the Orizaba. Here Irataba traded his suit and sombrero for the uniform and regalia of a major general, including a bright yellow sash and gold badge encrusted with precious stones. From it hung a medal that bore the inscription, "Irataba, Chief of the Mohaves, Arizona Territory". In February, a reporter for The New York Times quoted Irataba's explanation for his visit, "to see where so many pale faces come from". When journalist John Penn Curry asked him what he thought of Americans, Irataba replied: "Mericanos too much talk, too much eat, too much drink; no work, no raise pumpkins, corn, watermelons – all time walk, talk, drink – no good." He toured New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, D.C., earning great acclaim at each stop; government officials and military officers lavished him with gifts of medals, swords, and photographs. While in Washington, Irataba met with President Abraham Lincoln, who gave him a silver-headed cane "as a symbol of his chieftainship". He was the first Native American from the Southwestern United States to meet a US president. When the tour ended, he and Moss sailed to California and made their way back to Beale's Crossing in a wagon.

Disgrace and death

Having returned from his trip to Washington, Irataba met with the Mohave still dressed in his major general's uniform, which was by now covered in medals. He wore a European-style hat and carried a long Japanese sword that was given to him during his visit. He told the tribe about his incredible journey and all the "new and strange things" he had seen, including the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans, steam locomotives, granite skyscrapers that rivaled in height even the towering walls of the Mohave Canyon, and a seemingly endless population of white people. "So did my Great Dream foretell," he declared. "Now it has come true. With my own eyes I have seen it." He tried to convince the Mohave that peace with European Americans was in their best interests, and that war against them was futile, stressing their obviously dominant military capabilities. Nevertheless, the Mohave did not believe what they had heard, and they mocked him and accused him of being the "biggest liar on the Colorado".

—The University of California, 1870The old man is here now with his tribe, but he looks feeble, wan, and grief stricken. Age has come to Irataba, but it has brought to him no bright and peaceful twilight. Dark and cheerless appear the skies of his declining years.

Although Irataba had fallen out of favor with his people, who taunted him relentlessly after his return from Washington, he continued to lead them in their ongoing conflicts with neighboring tribes. In late 1865, he helped defeat the Chemehuevi in response to their allies, the Paiutes, having killed two Mohave women in retaliation for the Mohave's killing of a Paiute medicine man who failed to heal eight Mohave people inflicted with small pox. Irataba attacked the Chemehuevi first because they had disrespected the Mohave, and to avoid "a fire in the rear" when he turned their attention to the Paiutes, who were planning an attack on the Mohave farm and granary on Cottonwood Island. During a subsequent battle with the Paiutes, Irataba was taken prisoner while wearing his major general's uniform. They feared that killing him would invite repercussions from the soldiers stationed at Fort Mohave, so they instead stripped him naked and sent him home bloody and battered, to which the Mohave responded with still more ridicule, joking: "Not even the Paiutes would kill him."

A particularly strong rift developed between Irataba and a pro-war sub-chief, Homoseah Quahote, who at one time briefly imprisoned Irataba in an effort to supplant him. Ashamed and disgraced, Irataba scorned Native and European Americans alike, and retired in near isolation to a small hut where he lived out his final days. As time went on the people softened in their disdain for him, and as more and more whites settled in their lands it became clear that his dream had indeed come true, but it had also betrayed them. The Mohaves never replaced Irataba as head chief; he was their last, and when he died at the Colorado River Indian Reservation in June 1878, they burned his body, hut, and belongings according to tradition, "as was proper".

References

- Kroeber & Kroeber 1994, p. x: in 1960, Lorraine Sherer transcribed his full name as, Eechee Yara Tev; Ricky 1999, p. 100: Sun Fire clan.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 125.

- NYT & May 1864, p. 1.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 126.

- ^ Harte 1886, p. 492.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 127.

- ^ Ricky 1999, p. 100.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 127–28. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEWaters1993127–28" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 128.

- Zappia 2014, pp. 121, 138.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 129.

- Waters 1993, p. 130.

- Ricky 1999, pp. 100–01: soldiers arrived in December 1858; Waters 1993, pp. 130–31: Hoffman and fifty dragoons were dispatched from California.

- Waters 1993, pp. 130–31.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 131.

- Griffin-Pierce 2000, p. 246.

- NYT & February 1864: 9,000 warriors in his command; Waters 1993, p. 132: "the finest specimen of unadulterated manhood".

- Hanchett 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 132.

- O'Brien 2006, p. 249: sailed by way of the Isthmus of Panama; Waters 1993, p. 132: sailed on the Orizaba.

- NYT & February 1864.

- Curry 1865, p. 360.

- Ricky 1999, pp. 101–102.

- Waters 1993, pp. 132–33.

- ^ Waters 1993, p. 133.

- ^ Ricky 1999, p. 102.

- Museum of Northern Arizona 1951, p. 67.

- ^ Daily Alta California 1865.

- Kroeber & Kroeber 1994, p. 8: Irataba died at the Colorado River Indian Reservation; Ricky 1999, p. 100: Irataba died on June 17, 1878; Waters 1993, pp. 133–34: the Mohaves never replaced Irataba as chief; he was their last.

Notes

- Mohave who enjoyed higher status would cover their body in "goose grease" instead of mud.

- Irataba's height was approximately 6'4".

- In 1851, Irataba assisted Captain Lorenzo Sitgreaves during his exploration of the Colorado River.

- The Paiutes gave Irataba's major general's uniform to their chief, Sickahoot.

- It is uncertain what caused Irataba's death, but old age or smallpox are sometimes cited as possible causes.

Bibliography

- Curry, John Penn (1865). "Gazlay's Pacific Monthly, Volume 1". The New York Public Library. D. M. Gazlay.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Latest from Irataba's Land". Daily Alta California. Vol. 17, no. 5707. California Digital Newspaper Collection (CDNC). October 22, 1865. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (2000). Native Peoples of the Southwest. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 9780826319081.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanchett, Leland J. (1998). Catch the Stage to Phoenix. Pine Rim Publishing LLC. ISBN 9780963778567.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Harte, Brett, ed. (1886). Overland Monthly and Out West Magazine. A. Roman.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Museum of Northern Arizona (1951). "Plateau, Volumes 24-27". Northern Arizona Society of Science and Art.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kroeber, A.L.; Kroeber, C.B. (1994) . A Mohave War Reminiscence, 1854-1880. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486281636.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Arrival of the Indian Warrior, Irataba". The New York Times. February 7, 1864. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - "Return of Irataba: What he Thinks of New-York". The New York Times. May 4, 1864. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - O'Brien, Anne Hughes (2006). Traveling Indian Arizona. Big Earth Publishing. ISBN 9781565795181.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ricky, Donald B. (1999). Indians of Arizona: Past and Present. North American Book Distributors. ISBN 9780403098637.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Waters, Frank (1993). Brave Are My People: Indian Heros Not Forgotten. Clear Light Publishers. ISBN 9780940666214.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zappia, Natale A. (2014). Traders and Raiders: The Indigenous World of the Colorado Basin, 1540-1859. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469615851.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Kroeber, Alfred L. (1939). Cultural and Natural Areas of Native North America. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology.

- Shanley, Kathryn Winona (1997). "The Indians America Loves to Love and Read: American Indian Identity and Cultural Appropriation". American Indian Quarterly. 21 (4): 675–702. doi:10.2307/1185719. JSTOR 1185719.

- Shohat, Ella; Stam, Robert (1994). Unthinking Eurocentrism: Multiculturalism and the Media. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06324-8.

- Snipp, C.M. (1989). American Indians: The first of this land. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. ISBN 0-87154-822-4.

External links

- Official Mohave Nation Website

- Page about the Mohave Reservation by NAU

- Fort Mohave Tribe, InterTribal Council of Arizona