This is an old revision of this page, as edited by AlbinoFerret (talk | contribs) at 13:05, 29 February 2016 (revert addition of non MERDS source and claim, content should be sourced to a WP:MEDRS secondary source for medical claims). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 13:05, 29 February 2016 by AlbinoFerret (talk | contribs) (revert addition of non MERDS source and claim, content should be sourced to a WP:MEDRS secondary source for medical claims)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)The safety of electronic cigarettes is uncertain. There is little data about their health effects, and considerable variability between vaporizers and in quality of their liquid ingredients and thus the contents of the aerosol delivered to the user. Reviews on the safety of electronic cigarettes have reached significantly different conclusions. In July 2014 the World Health Organization (WHO) report cautioned about potential risks of using e-cigarettes. Regulated US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) products such as nicotine inhalers are probably safer than e-cigarettes. In 2015, Public Health England stated that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking. A 2014 systematic review concluded that the risks of e-cigarettes have been exaggerated by health authorities and stated that while there may be some remaining risk, the risk of e-cigarette use is likely small compared to smoking tobacco.

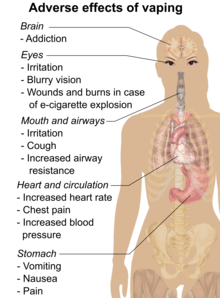

The long-term effects of e-cigarette use are unknown. A 2014 Cochrane review found no serious adverse effects reported in trials. Less serious adverse effects from e-cigarette use include throat and mouth inflammation, vomiting, nausea, and cough. The evidence suggests they produce less harmful effects than tobacco. A 2014 WHO report said, "ENDS use poses serious threats to adolescents and fetuses." Aside from toxicity, there are also risks from misuse or accidents such as contact with liquid nicotine, fires caused by vaporizer malfunction, and explosions as result from extended charging, unsuitable chargers, or design flaws. Battery explosions are caused by an increase in internal battery temperature and some have resulted in severe skin burns. There is a small risk of battery explosion in devices modified to increase battery power.

The e-liquid itself is highly toxic if it swallowed or spilled on skin and poison control centers track poisoning events.

After it is vaporized, e-liquid vapor has a low level of toxicity compared to cigarette smoke. Metal parts of e-cigarettes in contact with the e-liquid can contaminate it with metals. Normal usage of e-cigarettes generates very low levels of formaldehyde. A 2015 review found that later-generation e-cigarettes set at higher power may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking. A 2015 review found that these levels were the result of overheating under test conditions that bear little resemblance to common usage. The 2015 Public Health England report looking at the research concluded that by applying maximum power and increasing the time the device is used on a puffing machine, e-liquids can thermally degrade and produce high levels of formaldehyde. Users detect the "dry puff" and avoid it, and the report concluded that "There is no indication that EC users are exposed to dangerous levels of aldehydes." E-cigarette users are exposed to potentially harmful nicotine. Nicotine is associated with cardiovascular disease, potential birth defects, and poisoning. In vitro studies of nicotine have associated it with cancer, but carcinogenicity has not been demonstrated in vivo. There is inadequate research to demonstrate that nicotine is associated with cancer in humans. The risk is probably low from the inhalation of propylene glycol and glycerin. No information is available on the long-term effects of the inhalation of flavors.

E-cigarettes create vapor that consists of ultrafine particles, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range. The vapor has been found to contain flavors, propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, tiny amounts of toxicants, carcinogens, heavy metals, and metal nanoparticles, and other chemicals. Exactly what comprises the vapor varies in composition and concentration across and within manufacturers. However, e-cigarettes cannot be regarded as simply harmless. There is a concern that some of the mainstream vapor exhaled by e-cigarette users can be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors. E-cigarette use by a parent might lead to inadvertent health risks to offspring. A 2014 review recommended that e-cigarettes should be regulated for consumer safety. There is limited information available on the environmental issues around production, use, and disposal of e-cigarettes that use cartridges.

Health effects

Concerns

Reviews on the safety of electronic cigarettes have reached significantly different conclusions. Due to various methodological issues, severe conflicts of interest, and inconsistent research, no definite conclusions can be determined regarding the safety e-cigarettes. While they are likely less harmful than tobacco cigarettes, e-cigarettes cannot be regarded as harmless. The health community, pharmaceutical industry, and other groups have raised concerns about the emerging phenomenon of e-cigarettes including concern over as yet unknown health risks from long term use of e-cigarettes. A 2014 review recommended that e-cigarettes could be adequately regulated for consumer safety with existing directives on the design of electronic products. A policy statement by the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology has reported that "The benefits and harms must be evaluated with respect to the population as a whole, taking into account the effect on youth, adults, nonsmokers, and smokers."

Unknown

The health effects on intensive e-cigarette users are unknown. The effect on population health from e-cigarettes is unknown. Smokefree.gov, a website run by the Tobacco Control Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute to provide information to help quit smoking, stated that "Since e-cigs aren’t regulated yet, there’s no way of knowing how much nicotine is in them or what other chemicals they contain. These two things make the safety of e-cigs unclear." The English National Health Service has stated, "While e-cigarettes may be safer than conventional cigarettes, we don’t yet know the long-term effects of vaping on the body." The American Diabetes Association states "There is no evidence that e-cigarettes are a healthier alternative to smoking." In August 2014, the Forum of International Respiratory Societies stated that e-cigarettes have not been demonstrated to be safe. Health Canada has stated that, "their safety, quality, and efficacy remain unknown." Moreover, a WHO report in 2009 cautioned that the "safety of e-cigarettes is not confirmed."

Positives

A 2015 Public Health England report stated that e-cigarettes are estimated to be 95% less harmful than smoking. In June 2014, the Royal College of Physicians stated that, "On the basis of available evidence, the RCP believes that e-cigarettes could lead to significant falls in the prevalence of smoking in the UK, prevent many deaths and episodes of serious illness, and help to reduce the social inequalities in health that tobacco smoking currently exacerbates." A 2014 systematic review found that the limited evidence suggests that e-cigarettes are probably safer than tobacco smoke. Another review found that e-cigarette aerosol contains far fewer carcinogens than tobacco smoke, and concluded that e-cigarettes "impart a lower potential disease burden" than traditional cigarettes. Scientific studies advocate caution before designating e-cigarettes as beneficial but vapers continue to believe they are beneficial. Many users think that e-cigarettes are healthier than traditional cigarettes for personal use or for other people.

Negatives

The American Cancer Society has stated, "The makers of e-cigarettes say that the ingredients are "safe," but this only means the ingredients have been found to be safe to eat. Inhaling a substance is not the same as swallowing it. There are questions about how safe it is to inhale some substances in the e-cigarette vapor into the lungs." The Canadian Cancer Society has stated that, "A few studies have shown that there may be low levels of harmful substances in some e-cigarettes, even if they don’t have nicotine." In the UK a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline did not recommend e-cigarettes as there are questions regarding the safety, efficacy, and quality of these products. Generally, some users are concerned about the possible adverse health effects or toxicity of e-cigarettes. The US National Association of County and City Health Officials has stated, "Public health experts have expressed concern that e-cigarettes may increase nicotine addiction and tobacco use in young people." However, no long term studies have looked at future tobacco use as a result of using e-cigarettes. A 2013 review found, from limited data, their safety risk is similar to that of smokeless tobacco.

Adverse effects

As of 2015, the short and long term effects from using e-cigarettes remain unclear. One review noted that reports of adverse effects decreased over time, but long-term studies regarding the effects of constant use of e-cigarettes are needed. The adverse effects of e-cigarettes on people with cancer is unknown. A 2014 Cochrane review found no serious adverse effects from e-cigarette have been reported in trials.

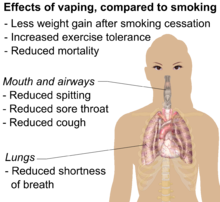

The most frequently reported less harmful effects of vaping compared to smoking were reduced shortness of breath, reduced cough, reduced spitting, and reduced sore throat. Adverse effects reported most often were mouth irritation, throat irritation, dry cough and nausea. Other reported adverse effects from e-cigarette use included shortness of breath, headache, chest pain and vomiting. Some case reports found harms to health brought about by e-cigarettes in many countries, such as the US and in Europe; the most common effect was dryness of the mouth and throat. Adverse effects like throat irritation could be the result of exposure to nicotine, nicotine solvents, or toxicants in the aerosol.

The US Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products reported between 2008 and the beginning of 2012, 47 cases of adverse effects associated with e-cigarettes, of which eight were considered serious. A causal relationship between e-cigarettes and the reported adverse effects was not established with the exception of two severe outcomes in the United States: a death when an infant choked on the cartridges and burns when one blew up. Major adverse effects reported to the FDA included hospitalizations for pneumonia, congestive heart failure, seizure, rapid heart rate, and burns. However no direct relationship has been proven between these effects and e-cigarette use, and some of them may be due to existing health problems. Many of the observed negative effects from e-cigarette use concerning the nervous system and the sensory system are probably related to nicotine overdose or withdrawal. Since e-cigarettes are intended to be used repeatedly, they can conveniently be used for an extended period of time, which may contribute to increased adverse effects. E-cigarettes were associated with fewer adverse effects than nicotine patches.

Poisoning

In youth, e-cigarette use risks involve accidental nicotine exposure. In pediatric patients, accidental exposures include ingesting of e-liquids and inhaling of e-cigarette vapor; choking on e-cigarette components is also a potential hazard. Unregulated e-cigarettes can be a risk to young children. Poisoning associated with e-cigarettes may happen by ingestion, inhalation, or absorption.

Two children, one in the United States in 2014 and another in Israel in 2013, died after ingesting liquid nicotine. Death from nicotine poisoning is very uncommon.

Calls to U.S. poison control centers related to e-cigarette exposures involved inhalations, eye exposures, skin exposures, and ingestion, in both adults and young children. In the United States the number of calls to poison control centers related to electronic cigarettes have increased between 2010 and 2014, such that they now represent 42% of reported cases due to either cigarettes and e-cigarettes up from 0.3%. The number decreased in 2015. The California Poison Control System reported 35 cases of e-cigarette contact from 2010 to 2012, 14 were in children and 25 were from accidental contact.

Fires, explosions, and other battery-related malfunctions

Most e-cigarettes use lithium batteries, the improper use of which may result in accidents. It has been recommended that manufacturing quality standards be imposed in order to prevent such accidents. Better product design and standards could probably reduce the risks.

Some batteries are not well designed, are made with poor quality components, or have defects. Rare major injuries have occurred from battery explosions and fires. House and car fires and skin burns have resulted from the explosions. The explosions were the result of extended charging, use of unsuitable chargers, or design flaws. The United States Fire Administration said that 25 fires and explosions were caused by e-cigarettes between 2009 and 2015. In the UK fire service call-outs had risen from 43 in 2013 to 62 in 2014. In 2015 Public Health England concluded that the risks of fire from e-cigarettes "appear to be comparable to similar electrical goods".

In January 2015 the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration issued a safety alert to air carriers that e-cigarettes should not be allowed in checked baggage after a review of fire safety issues, including two fires caused by e-cigarettes in checked baggage. The International Civil Aviation Organization, a United Nations agency, also recommends prohibiting e-cigarettes in checked luggage. A spokesman for the Tobacco Vapor Electronic Cigarette Association said that e-cigarettes do not pose a problem if they are packed correctly in static-free packaging, but that irresponsible people may sometimes pack them carelessly or tamper with them. In-flight use of e-cigarettes is also prohibited in the U.S.

Users may alter many of the devices, such as using them to administer other drugs like cannabis. The amount of vapor produced is controlled by the power of the battery, which has led some users to adjust their e-cigarettes to increase battery power to obtain a stronger nicotine "hit", but there is a small risk of battery explosion.

Risks related to e-liquid

There is a possibility that Inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact can expose people to high levels of nicotine, and with contaminants in the e-liquid. This may be especially risky to children, pregnant women, and nursing mothers. The nicotine in e-liquid can be hazardous to infants. A lot of the cartridges and the bottles of liquid are not child-resistant, and children may be attracted to the flavored liquids. Even a portion of e-liquid may be lethal to a little child. An excessive amount of nicotine for a child that is capable of being fatal is 0.1–0.2 mg/kg of body weight. An accidental ingestion of only 6 mg may be lethal to children.

Nicotine toxicity is a concern when e-cigarette solutions are swallowed intentionally by adults as a suicidal overdose. A man died in 2012 after injecting himself with nicotine liquid. An excessive amount of nicotine for an adult that is capable of being fatal is 0.5–1 mg/kg of body weight. A lethal dose for grownups is from 30 – 60 mg. However the widely used human LD50 estimate of 0.5–1.0 mg/kg was questioned in a 2013 review, in light of several documented cases of humans surviving much higher doses; the 2013 review suggests that the lower limit causing fatal outcomes is 500–1000 mg of ingested nicotine, corresponding to 6.5–13 mg/kg orally. Death from nicotine poisoning is very uncommon. The American Association of Poison Control Centers recorded 3,783 reported "exposure" incidents relating to liquid nicotine in 2014. The number decreased to 3,067 in 2015.

There was inconsistent labeling of the actual nicotine content on e-liquid cartridges from some brands, and some nicotine has been found in ‘no nicotine' liquids. In 2015 Public Health England noted overall the labelling accuracy has improved. Most inaccurately-labelled examples contained less nicotine than stated. Due to nicotine content inconstancy, it is recommended that e-cigarette companies develop quality standards with respect to nicotine content.

Because there is a lack of production standards and controls, the e-liquid cleanliness frequently is not dependable, and testing of some products has shown the existence of toxic substances. The German Cancer Research Center in Germany released a report stating that e-cigarettes cannot be considered safe, in part due to technical flaws that have been found. This includes leaking cartridges, accidental contact with nicotine when changing cartridges, and potential of unintended overdose. The Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) of Australia has stated that, "Some overseas studies suggest that electronic cigarettes containing nicotine may be dangerous, delivering unreliable doses of nicotine (above or below the stated quantity), or containing toxic chemicals or carcinogens, or leaking nicotine. Leaked nicotine is a poisoning hazard for the user of electronic cigarettes, as well as others around them, particularly children."

Toxicology

The long-term health impacts of e-cigarette use are unknown. The long-term health impacts of the main chemicals nicotine and propylene glycol in the aerosol are not fully understood. There is limited peer-reviewed data about the toxicity of e-cigarettes for a complete toxicological evaluation, or one of their cytotoxicity. The chemicals and toxic substances included in e-cigarettes have not been completely disclosed and their safety is not guaranteed. They are similar in toxicity to other nicotine replacement products, but there is not enough data to draw conclusions. The UK National Health Service noted that the toxic chemicals found by the FDA were at levels one-thousandth that of cigarette smoke, and that while there is no certainty that these small traces are harmless, initial test results are reassuring. While there is variability in the ingredients and concentrations of ingredients in e-cigarette liquids, tobacco smoke contains thousands of chemicals, most of which are not understood and many of which are known to be harmful.

Carcinogenicity

Concerns about the carcinogenicity of e-cigarettes arise from both nicotine and from other chemicals that may be in the vapor. As regards nicotine, there is evidence from in vitro and animal research that nicotine may have a role as a tumor promoter, but carcinogenicity has not been demonstrated in vivo. A 2014 Surgeon General of the United States report concluded that the single relevant randomized trial "does not indicate a strong role for nicotine in promoting carcinogenesis in humans, and clearly the risk, if any, is less than continued smoking". The report concluded that "There is insufficient data to conclude that nicotine causes or contributes to cancer in humans, but there is evidence showing possible oral, esophageal, or pancreatic cancer risks". Older types of nicotine replacement products have not been shown to be associated with cancer in the real world.

There is no long-term research concerning the cancer risk related to the small level of exposure to the identified carcinogens that may be in e-cigarette vapor. In October 2012, the World Medical Association stated, "Manufacturers and marketers of e-cigarettes often claim that use of their products is a safe alternative to smoking, particularly since they do not produce carcinogenic smoke. However, no studies have been conducted to determine that the vapor is not carcinogenic, and there are other potential risks associated with these devices."

Since nicotine-containing e-liquids are made from tobacco they may contain impurities like cotinine, anabasine, anatabine, myosmine and beta-nicotyrine. The majority of e-cigarettes evaluated included carcinogenic tobacco-specific nitrosamines (TSNAs) and the carcinogen toluene. However, in comparison to traditional cigarette smoke, the toxic substance levels identified in e-cigarette vapor were 9- to 450-fold less. While e-cigarettes cannot be considered safe because there is no safe level for carcinogens, they are safer than tobacco cigarettes.

A 2014 review found higher levels of carcinogens and toxins than in an FDA-approved nicotine inhaler, suggesting that FDA-approved devices may deliver nicotine more safely. In 2014, The World Lung Foundation stated that "Researchers find that many e-cigarettes contain toxins, contaminants and carcinogens that conflict with the industry’s portrayal of its products as purer, healthier alternatives. They also find considerable variations in the amount of nicotine delivered by different brands. None of this information is made available to consumers so they really don’t know what they are ingesting, or how much."

A 2014 review found "Various chemical substances and ultrafine particles known to be toxic, carcinogenic and/or to cause respiratory and heart distress have been identified in e-cigarette aerosols, cartridges, refill liquids and environmental emissions." Few of the methods used to analyze the chemistry of e-cigarettes in the studies the review evaluated were validated.

Propylene glycol and other chemicals

The primary base ingredients of the liquid solution is propylene glycol and glycerin. About 20% to 27% of propylene glycol and glycerin-based liquid particles are inhaled. Being exposed to propylene glycol may cause irritation to the eyes and respiratory tract. The risk from the inhalation of propylene glycol and glycerin is probably low. Propylene glycol and glycerin have not been shown to be safe. The long-term effects of inhaled propylene glycol has not been studied. Some research states that propylene glycol emissions may cause respiratory irritation and raise the likelihood to develop asthma. To lessen the risks, many e-cigarettes companies are using purified water and glycerin instead of propylene glycol for aerosol production. The effects of inhaled glycerin are unknown.

Some e-cigarette products had acrolein identified in the aerosol. It may be generated when glycerol is heated to higher temperatures. Acrolein may induce irritation to the upper respiratory tract. Acrolein levels were reduced by 60% in dual users and 80% for those that completely switched to e-cigarettes when compared to traditional cigarettes. Butyl acetate, diethyl carbonate, benzoic acid, quinoline, and bis(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate have been found in e-cigarettes.

The toxicity of e-cigarettes and e-liquid can vary greatly, as there are differences in construction and materials in the delivery device, kind and origin of ingredients in the e-liquid, and the use or non-use of good manufacturing practices and quality control approaches. If exposure of aerosols to propylene glycol and glycerin rises to levels that one would consider the exposure in association with a workplace setting, it would be sensible to investigate the health of exposed persons. The short-term toxicity of e-cigarette use appears to be low, with the exception for some people with reactive airways.

Flavouring

The essential propylene glycol and/or glycerol mixture may consist of natural or artificial substances to provide it flavor. The cytotoxicity of e-liquids varies. Some flavors are regarded as toxic and a number of them resemble known carcinogens. Generally, flavoring additives are imprecisely described, using terms such as "vegetable flavoring". Although they are approved for human consumption there are no studies on the short or long term effects of inhaling them. Some artificial flavors have been demonstrated as being cytotoxic. The cytotoxicity is mostly due to the amount and number of flavors added. Cinnamaldehyde has been documented as a highly cytotoxic material in vitro and has been found to be present in certain cinnamon-flavored refill solutions. A study has demonstrated that a balsamic flavored e-cigarette with no nicotine is capable of triggering a proinflammatory cytokine release in lung epithelial cells and keratinocytes. Some additives may be added to lower the irritation on the pharynx. The precise ingredients of e-cigarettes are not known. The long-term toxicity is subject to the additives and contaminants in the e-liquid.

Diacetyl

Certain flavorings contain diacetyl and acetyl-propionyl which give a buttery taste. Diacetyl has previously been connected to bronchiolitis obliterans when breathed in as an aerosol by popcorn manufacturers, known then as Popcorn lung. A 2015 review urged for specific regulation of diacetyl and acetyl-propionyl in e-liquid, which are safe when ingested but have been associated with respiratory harm when inhaled. Both diacetyl and acetyl-propionyl have been found in concentrations beyond those recommended by the US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Diacetyl is normally found at lower levels in e-cigarettes than in traditional cigarettes.

Formaldehyde

The IARC has categorized formaldehyde as a human carcinogen, and acetaldehyde is categorized as a potential carcinogenic to humans. formaldehyde, acetaldehyde, acrolein, and glyoxal are frequently identified in e-cigarette aerosols, they are produced when the liquid is heated by the heating element, to high temperatures. Aldehydes may cause harmful health effects; though, in the majority of cases, the amounts inhaled are less than those in traditional cigarettes. A 2014 review found propylene glycol-containing liquids produced the most amounts of carbonyls. The levels of toxic substances in the vapor were found to be 1 to 2 orders of magnitude smaller than in cigarette smoke but greater than from a nicotine inhaler.

Battery output voltage influences the level of the carbonyl substances in the vapor. A few new e-cigarettes let users boost the amount of vapor and nicotine provided by modifying the battery output voltage. Reduced voltages (e.g. 3.0 volts) produce vapor with levels of formaldehyde and acetaldehyde roughly 13 and 807-fold less than indicated in cigarette smoke. "Dripping", where the liquid is dripped directly onto the atomizer, can create carbonyl compounds including formaldehyde.

Normal usage of e-cigarettes generates very low levels of formaldehyde. A 2015 review found that later-generation e-cigarettes set at higher power may generate equal or higher levels of formaldehyde compared to smoking. A 2015 review found that these levels were the result of overheating under test conditions that bear little resemblance to common usage. The 2015 Public Health England report looking at the research concluded that by applying maximum power and increasing the time the device is used on a puffing machine, e-liquids can thermally degrade and produce high levels of formaldehyde. Users detect the "dry puff" and avoid it, and the report concluded that "There is no indication that EC users are exposed to dangerous levels of aldehydes."

Nicotine

There are safety issues with the nicotine exposure from e-cigarettes, which may cause addiction and other adverse effects. Nicotine is regarded as a potentially lethal poison. Concerns exist that e-cigarette user exposure to toxic levels of nicotine may be harmful. However at the low amount of nicotine provided by e-cigarettes fatal overdose from use is unlikely; in contrast, the potent amount of nicotine in e-cigarettes liquids may be toxic if it is accidentally ingested or absorbed via the skin. The health effects of nicotine in infants and children are unclear.

E-cigarettes provide nicotine to the blood quicker than nicotine inhalers. The levels were above that of nicotine replacement product users. How efficiently different e-cigarettes give nicotine is unclear. Serum cotinine levels are comparable to that of traditional cigarettes, but are inharmonious and rely upon the user and the device.

First generation devices

When compared to tobacco cigarettes older devices usually delivered low amounts of nicotine. E-cigarette use can be associated with a substantial dispersion of nicotine, thus generating a plasma nicotine concentration which can be comparable to that of traditional cigarettes. The nicotine delivered from e-cigarettes enters the body slower than traditional cigarettes. Studies suggest that inexperienced users obtain moderate amounts of nicotine from e-cigarettes. Further concerns were raised over inconsistent amounts of nicotine delivered when drawing on the device.

Newer generation devices

Later-generation e-cigarettes gives nicotine more effectively than first generation e-cigarettes. They may have concentrated nicotine liquids which may deliver nicotine at levels similar to traditional cigarettes. E-cigarettes with stronger batteries heat solutions to higher temperatures, which may raise blood nicotine levels to those of traditional cigarettes. Research suggests that experienced e-cigarettes users are able to get as much nicotine from e-cigarettes as traditional cigarettes.

Concerns

Nicotine affects practically every cell in the body. Nicotine can cause high blood pressure and abnormal heart rhythms. Nicotine may have adverse effects on lipids. Nicotine lowers estrogen levels and has been associated with early menopause in women. Nicotine could have cancer-promoting properties, therefore long-term use may not be harmless. Nicotine may result in neuroplasticity variations in the brain. In youth, there is a chance of nicotine addiction, nicotine may affect brain development, later achievement, and capabilities connected with higher cognitive function processes. In August 2014, the American Heart Association noted that "e-cigarettes could fuel and promote nicotine addiction, especially in children". A policy statement by the UK's Faculty of Public Health has stated, "A key concern for everyone in public health is that children and young people are being targeted by mass advertising of e-cigarettes. There is a danger that e-cigarettes will lead to young people and non-smokers becoming addicted to nicotine and smoking. Evidence from the US backs up this concern." Some products contained trace amounts of the drugs tadalafil and rimonabant.

Metals

There is limited evidence on the long-term exposure of metals. E-cigarettes contain some contamination with small amounts of metals in the emissions but it is not likely that these amounts would cause a serious risk to the health of the user. The device itself could contribute to the toxicity from the tiny amounts of silicate and heavy metals found in the liquid and vapor, because they have a metal parts that come in contact with the e-liquid. A 2014 review found e-cigarettes emissions contain the heavy metals nickel, tin, and chromium, when testing first generation cartimizers of low quality. Lead has also been found. Metals may adversely affect the nervous system. A 2014 review noted a study had found metal particles in the fluid and aerosol, at levels were 10-50 times less than that allowed in medicines that are inhaled. A 2014 review found it can be concluded that there is no evidence of contamination of the aerosol with metals that justifies a health concern.

Comparison of levels of toxicants in e-cigarette aerosol

| Toxicant | Range of content in nicotine inhaler mist (15 puffs∗) | Content in aerosol from 12 e-cigarettes (15 puffs∗) | Content in traditional cigarette micrograms (μg) in smoke from one cigarette |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formaldehyde (μg) | 0.2 | 0.2-5.61 | 1.6-52 |

| Acetaldehyde (μg) | 0.11 | 0.11-1.36 | 52-140 |

| Acrolein (μg) | ND | 0.07-4.19 | 2.4-62 |

| o-Methylbenzaldehyde (μg) | 0.07 | 0.13-0.71 | — |

| Toluene (μg) | ND | ND-0.63 | 8.3-70 |

| p- and m-Xylene (μg) | ND | ND-0.2 | — |

| NNN (ng) | ND | ND-0.00043 | 0.0005-0.19 |

| Cadmium (ng) | 0.003 | ND-0.022 | — |

| Nickel (ng) | 0.019 | 0.011-0.029 | — |

| Lead (ng) | 0.004 | 0.003-0.057 | — |

μg, microgram; ng, nanogram; ND, not detected

∗Fifteen puffs were chosen to estimate the nicotine delivery of one traditional cigarette.

Effects on breathing and lung function

The risks to the lungs are not fully understood, and are of concern to public health authorities. There is also limited evidence on the long-term health effects to the lungs, or cardiovascular system. Reports on the levels of toxicants in the emissions are inconsistent. The effects of e-cigarette use in respect to asthma and other respiratory diseases are unknown.

The long-term effects regarding respiratory flow resistance are unknown. The immediate effects of e-cigarettes after 5 minutes of use on pulmonary function resulted in considerable increases in resistance to lung airflow. This resistance may harm the respiratory system. Though any harmful effects to cardiovascular and respiratory functions after short-term use of e-cigarettes were appreciably milder in comparison to traditional cigarettes. Short-term physiological effects include increases in blood pressure and heart rate.

This could increase the risk of cardiac arrhythmias and hypertension which may put some users, particularly those with atherosclerosis or other cardiovascular risk factors, at significant risk of acute coronary syndrome. Some case reports documented the possible cardiovascular adverse effects from using e-cigarettes, the majority associated was with improper use. Even though e-cigarettes are anticipated to produce fewer dangerous substances than traditional cigarettes, limited evidence supports they comparatively have a lessened raised cardiovascular risk for e-cigarettes users. The limited evidence suggests that e-cigarettes produce less short-term effects on lung function than traditional cigarettes. A 2015 review found e-cigarettes may induce acute lung disease.

Aerosol and e-liquid

Main article: Electronic cigarette aerosol and e-liquid

The aerosol of electronic cigarettes is generated when the e-liquid reaches a temperature of roughly 100-250 °C within a chamber. The user inhales the aerosol, commonly called vapor, rather than cigarette smoke. The aerosol provides a flavor and feel similar to tobacco smoking. In physics, a vapor is a substance in the gas phase whereas an aerosol is a suspension of tiny particles of liquid, solid or both within a gas. The aerosol is made-up of liquid sub-micron particles of condensed vapor, which mostly consist of propylene glycol, glycerol, water, flavorings, nicotine, and other chemicals. After a puff, inhalation of the aerosol travels from the device into the mouth and lungs. The particle size distribution and sum of particles emitted by e-cigarettes are like traditional cigarettes, with the majority of particles in the ultrafine range (modes, ≈100–200). The particles are of the ultrafine size which can go deep in the lungs and then into the systemic circulation. These nanoparticles can deposit in the lung's alveolar sacs, potentially leading to local respiratory toxicity.

After the aerosol is inhaled, it is exhaled. Emissions from electronic cigarettes are not comparable to environmental pollution or cigarette smoke as their nature and chemical composition are completely different The particles are larger, with the mean size being 600 nm in inhaled aerosol and 300 nm in exhaled vapor. Bystanders are exposed to these particles from exhaled e-cigarette vapor. There is a concern that some of the mainstream vapor exhaled by e-cigarette users can be inhaled by bystanders, particularly indoors, and have significant adverse effects. Since e-cigarettes involve an aerosolization process, it is suggested that no meaningful amounts of carbon monoxide are emitted. Thus, cardiocirculatory effects caused by carbon monoxide are not likely. E-cigarette use by a parent might lead to inadvertent health risks to offspring. E-cigarettes pose many safety concerns to children. For example, indoor surfaces can accumulate nicotine where e-cigarettes were used, which may be inhaled by children, particularly youngsters, long after they were used.

E-liquid is the mixture used in vapor products such as electronic cigarettes. The main ingredients in the e-liquid usually are propylene glycol, glycerin, nicotine, and flavorings. However, there are e-liquids sold without propylene glycol, nicotine, or flavors. The liquid typically contains 95% propylene glycol and glycerin. The flavorings may be natural or artificial. About 8,000 flavors exist as of 2014. There are many e-liquids manufacturers in the USA and worldwide. While there are currently no US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) manufacturing standards for e-liquid, the FDA has proposed regulations that are expected to be finalized in late 2015. Industry standards have been created and published by the American E-liquid Manufacturing Standards Association (AEMSA).

Effects during pregnancy

A 2014 review stated there are concerns about pregnant women exposure to e-cigarette vapor through direct use or via exhaled vapor. As of 2014, there are no conclusions on the possible hazards of pregnant women using e-cigarettes, and there is a developing research on the negative effects of nicotine on prenatal brain development. A 2015 review concluded no amount of nicotine is safe for pregnant women. E-cigarette are assumed to be dangerous to the fetus during pregnancy if e-cigarettes are used by the mother. Prenatal exposure has been associated with obesity, diabetes, high cholesterol and high blood pressure in minors. As of 2015, the long-term issues of e-cigarettes on both mother and unborn baby are unknown. There are concerns about the health impacts of pediatric exposure to second-hand and third-hand e-cigarette vapor. The Surgeon General's 2014 report found "that nicotine adversely affects maternal and fetal health during pregnancy, and that exposure to nicotine during fetal development has lasting adverse consequences for brain development." The belief that e-cigarettes are safer than traditional cigarettes could increase their use for pregnant women. The toxic effects identified with e-cigarette refill liquids on stem cells may be interpreted as embryonic death or birth defects. Since e-cigarettes are not validated as cessation tools, may contain nicotine at inconsistent levels and added ingredients that are possibly harmful, allowing e-cigarettes to be used among pregnant women to decrease smoking puts this group at considerable risk.

Environmental impact

There is limited information available on any environmental issues connected to the production, usage, and disposal of e-cigarette models that use cartridges. As of May 2014, no formal studies have been done to evaluate the environmental effects of making or disposing of any part of e-cigarettes including the batteries or nicotine production. As of May 2014, it is uncertain if the nicotine in e-liquid is United States Pharmacopeia-grade nicotine, a tobacco extract, or synthetic nicotine when questioning the environmental impact of how it is made. It is not clear which manufacturing methods are used to make the nicotine used in e-cigarettes. The emissions from making nicotine could be considerable from manufacturing if not appropriately controlled. Some e-cigarette brands that use cartridges state their products are ‘eco-friendly’ or ‘green’, despite the absence of any supporting studies. Some writers contend that such marketing may raise sales and increase e-cigarette interest, particularly among minors. It is unclear how many traditional cigarettes are comparable to using one e-cigarette that uses a cartridge for the average user. Information is limited on energy and materials used for production of e-cigarettes versus traditional cigarettes, for comparable use. E-cigarettes can be made manually put together in small factories, or they can be made in automated lines on a much bigger scale. Larger plants will produce greater emissions to the surrounding environment, and thus will have a greater environmental impact. Although some brands have begun recycling services for their e-cigarette cartridges and batteries, the prevalence of recycling is unknown, as is the prevalence of information provided by manufacturers on how to recycle disposable parts. A 2014 review found "disposable e-cigarettes might cause an electrical waste problem."

Compared to traditional cigarettes, e-cigarettes do not create litter in the form of discarded cigarette butts. Traditional cigarette butts contain cellulose acetate and have tended to end up in the ocean where they caused pollution (which is significant, due to the high number of cigarettes sold globally).

Public perceptions

The UK Action on Smoking and Health found that in 2015, compared to the year before, "there has been a growing false belief that electronic cigarettes could be as harmful as smoking". Among smokers who had heard of e-cigarettes but never tried them, this "perception of harm has nearly doubled from 12% in 2014 to 22% in 2015." The charity expressed concern that "The growth of this false perception risks discouraging many smokers from using electronic cigarettes to quit and keep them smoking instead which would be bad for their health and the health of those around them."

A 2015 Public Health England report noted, as well as the UK figures above, that in the US belief among responders to a survey that vaping was safer than smoking cigarettes fell from 82% in 2010 to 51% in 2014. The report blamed "misinterpreted research findings", attracting negative media coverage, for the growth in the "inaccurate" belief that e-cigarettes were as harmful as smoking, and concluded that "There is a need to publicise the current best estimate that using EC is around 95% safer than smoking".

See also

Notes

- citing "Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors-effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage" by Kosmider.

- citing "Carbonyl compounds in electronic cigarette vapors-effects of nicotine solvent and battery output voltage" by Kosmider.

References

- ^ Ebbert, Jon O.; Agunwamba, Amenah A.; Rutten, Lila J. (2015). "Counseling Patients on the Use of Electronic Cigarettes". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 90 (1): 128–134. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.11.004. ISSN 0025-6196. PMID 25572196.

- Siu, AL (22 September 2015). "Behavioral and Pharmacotherapy Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Women: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". Annals of Internal Medicine. 163: 622–34. doi:10.7326/M15-2023. PMID 26389730.

- Harrell, PT; Simmons, VN; Correa, JB; Padhya, TA; Brandon, TH (4 June 2014). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems ("E-cigarettes"): Review of Safety and Smoking Cessation Efficacy". Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 151: 381–393. doi:10.1177/0194599814536847. PMID 24898072.

- Palazzolo, Dominic L. (Nov 2013). "Electronic cigarettes and vaping: a new challenge in clinical medicine and public health. A literature review". Frontiers in Public Health. 1 (56). doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00056. PMC 3859972. PMID 24350225.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Odum, L. E.; O'Dell, K. A.; Schepers, J. S. (December 2012). "Electronic cigarettes: do they have a role in smoking cessation?". Journal of pharmacy practice. 25 (6): 611–4. doi:10.1177/0897190012451909. PMID 22797832.

- ^ Grana, R; Benowitz, N; Glantz, SA (13 May 2014). "E-cigarettes: a scientific review". Circulation. 129 (19): 1972–86. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. PMC 4018182. PMID 24821826.

- O'Connor, RJ (March 2012). "Non-cigarette tobacco products: what have we learnt and where are we headed?". Tobacco control. 21 (2): 181–90. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050281. PMC 3716250. PMID 22345243.

- ^ Farsalinos, Konstantinos E; Le Houezec, Jacques (29 September 2015). "Regulation in the face of uncertainty: the evidence on electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes)". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 2015 (8): 157–167. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S62116. PMC 4598199. PMID 26457058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ WHO. "Electronic nicotine delivery systems" (PDF). pp. 1–13. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ Drummond, MB; Upson, D (February 2014). "Electronic cigarettes. Potential harms and benefits". Annals of the American Thoracic Society. 11 (2): 236–42. doi:10.1513/annalsats.201311-391fr. PMID 24575993.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. p. 76. Retrieved 19 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Farsalinos, K. E.; Polosa, R. (2014). "Safety evaluation and risk assessment of electronic cigarettes as tobacco cigarette substitutes: a systematic review". Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety. 5 (2): 67–86. doi:10.1177/2042098614524430. ISSN 2042-0986. PMC 4110871. PMID 25083263.

- ^ "Electronic cigarettes: patterns of use, health effects, use in smoking cessation and regulatory issues". Tob Induc Dis. 12 (1): 21. 2014. doi:10.1186/1617-9625-12-21. PMC 4350653. PMID 25745382.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- ^ McRobbie, Hayden; Bullen, Chris; Hartmann-Boyce, Jamie; Hajek, Peter; McRobbie, Hayden (2014). "Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation and reduction". The Cochrane Library. 12: CD010216. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub2. PMID 25515689.

- "The Potential Adverse Health Consequences of Exposure to Electronic Cigarettes and Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems". Oncology Nursing Forum. 42 (5): 445–446. 2015. doi:10.1188/15.ONF.445-446. ISSN 0190-535X. PMID 26302273.

- ^ Durmowicz, E. L. (2014). "The impact of electronic cigarettes on the paediatric population". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii41 – ii46. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051468. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732163.

- ^ Rowell, Temperance R; Tarran, Robert (2015). "Will Chronic E-Cigarette Use Cause Lung Disease?". American Journal of Physiology. Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology: ajplung.00272.2015. doi:10.1152/ajplung.00272.2015. ISSN 1040-0605. PMID 26408554.

- ^ Crowley, Ryan A. (2015). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: Executive Summary of a Policy Position Paper From the American College of Physicians". Annals of Internal Medicine. 162 (8): 583–4. doi:10.7326/M14-2481. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 25894027.

- ^ Brandon, T. H.; Goniewicz, M. L.; Hanna, N. H.; Hatsukami, D. K.; Herbst, R. S.; Hobin, J. A.; Ostroff, J. S.; Shields, P. G.; Toll, B. A.; Tyne, C. A.; Viswanath, K.; Warren, G. W. (2015). "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems: A Policy Statement from the American Association for Cancer Research and the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Clinical Cancer Research. 21: 514–525. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2544. ISSN 1078-0432. PMID 25573384.

- ^ Orr, KK; Asal, NJ (November 2014). "Efficacy of Electronic Cigarettes for Smoking Cessation". The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 48 (11): 1502–1506. doi:10.1177/1060028014547076. PMID 25136064.

- ^ Bertholon, J.F.; Becquemin, M.H.; Annesi-Maesano, I.; Dautzenberg, B. (2013). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Short Review". Respiration. 86: 433–8. doi:10.1159/000353253. ISSN 1423-0356. PMID 24080743.

- Fernández, Esteve; Ballbè, Montse; Sureda, Xisca; Fu, Marcela; Saltó, Esteve; Martínez-Sánchez, Jose M. (2015). "Particulate Matter from Electronic Cigarettes and Conventional Cigarettes: a Systematic Review and Observational Study". Current Environmental Health Reports. 2: 423–9. doi:10.1007/s40572-015-0072-x. ISSN 2196-5412. PMID 26452675.

- ^ Polosa, R; Campagna, D; Caponnetto, P (September 2015). "What to advise to respiratory patients intending to use electronic cigarettes". Discovery medicine. 20 (109): 155–61. PMID 26463097.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. pp. 77–78.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cheng, T. (2014). "Chemical evaluation of electronic cigarettes". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii11 – ii17. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051482. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995255. PMID 24732157.

- ^ "E-cigarettes: Safe to recommend to patients?". Cleve Clin J Med. 82 (8): 521–6. 2015. doi:10.3949/ccjm.82a.14054. PMID 26270431.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General, 2014, Chapter 5 - Nicotine" (PDF). Surgeon General of the United States. 2014. pp. 107–138.

- ^ Hajek, P; Etter, JF; Benowitz, N; Eissenberg, T; McRobbie, H (31 July 2014). "Electronic cigarettes: review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers and potential for harm and benefit" (PDF). Addiction (Abingdon, England). 109 (11): 1801–10. doi:10.1111/add.12659. PMID 25078252.

- ^ Pisinger, Charlotta; Døssing, Martin (December 2014). "A systematic review of health effects of electronic cigarettes". Preventive Medicine. 69: 248–260. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.009. PMID 25456810.

- ^ Rom, Oren; Pecorelli, Alessandra; Valacchi, Giuseppe; Reznick, Abraham Z. (2014). "Are E-cigarettes a safe and good alternative to cigarette smoking?". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1340 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/nyas.12609. ISSN 0077-8923. PMID 25557889.

- ^ England, Lucinda J.; Bunnell, Rebecca E.; Pechacek, Terry F.; Tong, Van T.; McAfee, Tim A. (2015). "Nicotine and the Developing Human". American Journal of Preventive Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.015. ISSN 0749-3797. PMID 25794473.

- ^ Saitta, D; Ferro, GA; Polosa, R (Mar 2014). "Achieving appropriate regulations for electronic cigarettes". Therapeutic advances in chronic disease. 5 (2): 50–61. doi:10.1177/2040622314521271. PMC 3926346. PMID 24587890.

- ^ Chang, H. (2014). "Research gaps related to the environmental impacts of electronic cigarettes". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii54 – ii58. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051480. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995274. PMID 24732165.

- "E-Cigarettes". Tobacco Control Research Branch of the National Cancer Institute.

- "Stop smoking treatments". UK National Health Service.

- "Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes--2015: Summary of Revisions". Diabetes Care. 54 (38): S25. 2015. doi:10.2337/dc15-S003. PMID 25537706.

- &NA; (August 2014). "E-Cigarettes". Oncology Times. 36 (15): 49–50. doi:10.1097/01.COT.0000453432.31465.77.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Nicotine addiction". Health Canada.

- ^ Bekki, Kanae; Uchiyama, Shigehisa; Ohta, Kazushi; Inaba, Yohei; Nakagome, Hideki; Kunugita, Naoki (2014). "Carbonyl Compounds Generated from Electronic Cigarettes". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 11 (11): 11192–11200. doi:10.3390/ijerph111111192. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 25353061.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Dagaonkar RS, R.S.; Udwadi, Z.F. (2014). "Water pipes and E-cigarettes: new faces of an ancient enemy" (PDF). Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 62 (4): 324–328. PMID 25327035.

- "RCP statement on e-cigarettes". Royal College of Physicians. 25 June 2014.

- ^ Oh, Anne Y.; Kacker, Ashutosh (December 2014). "Do electronic cigarettes impart a lower potential disease burden than conventional tobacco cigarettes?: Review on e-cigarette vapor versus tobacco smoke". The Laryngoscope. 124 (12): 2702–2706. doi:10.1002/lary.24750. PMID 25302452.

- ^ Pepper, J. K.; Brewer, N. T. (2013). "Electronic nicotine delivery system (electronic cigarette) awareness, use, reactions and beliefs: a systematic review". Tobacco Control. 23 (5): 375–384. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051122. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24259045.

- "What about electronic cigarettes? Aren't they safe?". American Cancer Society.

- "Ways to quit". Canadian Cancer Society.

- "Nicotine products can help people to cut down before quitting smoking". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

- "Regulation of Electronic Cigarettes ("E-Cigarettes")" (PDF). National Association of County and City Health Officials.

- ^ Caponnetto P; Russo C; Bruno CM; Alamo A; Amaradio MD; Polosa R. (Mar 2013). "Electronic cigarette: a possible substitute for cigarette dependence". Monaldi archives for chest disease. 79 (1): 12–19. doi:10.4081/monaldi.2013.104. PMID 23741941.

- Detailed reference list is located on a separate image page.

- Orellana-Barrios, Menfil A.; Payne, Drew; Mulkey, Zachary; Nugent, Kenneth (2015). "Electronic cigarettes-a narrative review for clinicians". The American Journal of Medicine. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.01.033. ISSN 0002-9343. PMID 25731134.

- ^ Gualano, M. R.; Passi, S.; Bert, F.; La Torre, G.; Scaioli, G.; Siliquini, R. (9 August 2014). "Electronic cigarettes: assessing the efficacy and the adverse effects through a systematic review of published studies". Journal of Public Health. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdu055. PMID 25108741.

- Lauterstein, Dana; Hoshino, Risa; Gordon, Terry; Watkins, Beverly-Xaviera; Weitzman, Michael; Zelikoff, Judith (2014). "The Changing Face of Tobacco Use Among United States Youth". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 7 (1): 29–43. doi:10.2174/1874473707666141015220110. ISSN 1874-4737. PMID 25323124.

- Evans, S. E.; Hoffman, A. C. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: abuse liability, topography and subjective effects". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii23 – ii29. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051489. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995256. PMID 24732159.

- "Poison Center Calls Involving E-Cigarettes". CDC.

- Biyani, S; Derkay, CS (28 April 2015). "E-cigarettes: Considerations for the otolaryngologist". International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 79: 1180–3. doi:10.1016/j.ijporl.2015.04.032. PMID 25998217.

- ^ Mohney, Gillian, "First Child's Death From Liquid Nicotine Reported as 'Vaping' Gains Popularity", ABC News, December 12, 2014.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (April 2014). "Notes from the field: calls to poison centers for exposures to electronic cigarettes--United States, September 2010-February 2014". MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 63 (13): 292–3. PMID 24699766.

- ^ "Electronic Cigarettes and Liquid Nicotine Data" (PDF). American Association of Poison Control Centers. Retrieved 9 January 2016.

- ^ Yang, L.; Rudy, S. F.; Cheng, J. M.; Durmowicz, E. L. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: incorporating human factors engineering into risk assessments". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii47 – ii53. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051479. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732164.

- "Man seriously injured by e-cigarette explosion", CBS News, November 24, 2015, Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- ^ Jansen, Bart, "Packing e-Cigarettes in luggage is a fire risk, FAA warns", USA Today, January 23, 2015.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link), pages 83-84. 43/46 UK fire services responded, 2014 figures are for 1 January to 15 November only. - ^ Hasley III, Ashley, "The FAA wants you to carry on your e-Cigs", The Washington Post, January 26, 2015.

- ^ Brown, C. J.; Cheng, J. M. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: product characterisation and design considerations". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii4 – ii10. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051476. ISSN 0964-4563. PMC 3995271. PMID 24732162.

- "State Health Officer's Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat" (PDF). California Department of Public Health, California Tobacco Control Program. January 2015.

- ^ Jimenez Ruiz, CA; Solano Reina, S; de Granda Orive, JI; Signes-Costa Minaya, J; de Higes Martinez, E; Riesco Miranda, JA; Altet Gómez, N; Lorza Blasco, JJ; Barrueco Ferrero, M; de Lucas Ramos, P (August 2014). "The electronic cigarette. Official statement of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) on the efficacy, safety and regulation of electronic cigarettes". Archivos de bronconeumologia. 50 (8): 362–7. doi:10.1016/j.arbr.2014.06.007. PMID 24684764.

- ^ "Electronic Cigarettes – An Overview" (PDF). German Cancer Research Center.

- ^ Bhatnagar, A.; Whitsel, L. P.; Ribisl, K. M.; Bullen, C.; Chaloupka, F.; Piano, M. R.; Robertson, R. M.; McAuley, T.; Goff, D.; Benowitz, N. (24 August 2014). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Policy Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 130 (16): 1418–1436. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000107. PMID 25156991.

- Mayer B (January 2014). "How much nicotine kills a human? Tracing back the generally accepted lethal dose to dubious self-experiments in the nineteenth century". Archives of Toxicology. 88 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1007/s00204-013-1127-0. PMC 3880486. PMID 24091634.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. p. 67–68. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Electronic cigarettes". Therapeutic Goods Administration.

- "Cancer Research UK Briefing: Electronic Cigarettes" (PDF). Cancer Research UK. May 2014.

- ^ Orr, M. S. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes in the USA: a summary of available toxicology data and suggestions for the future". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii18 – ii22. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051474. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732158.

- "E-cigarettes to be regulated as medicines". National Health Service. 12 June 2013. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - "WMA Statement on Electronic Cigarettes and Other Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems". World Medical Association.

- Arnold, Carrie (2014). "Vaping and Health: What Do We Know about E-Cigarettes?". Environmental Health Perspectives. 122 (9): A244 – A249. doi:10.1289/ehp.122-A244. PMC 4154203. PMID 25181730.

- M., Z.; Siegel, M. (February 2011). "Electronic cigarettes as a harm reduction strategy for tobacco control: a step forward or a repeat of past mistakes?". Journal of public health policy. 32 (1): 16–31. doi:10.1057/jphp.2010.41. PMID 21150942.

- ^ "WHO Right to Call for E-Cigarette Regulation". World Lung Federation.

- Alawsi, F.; Nour, R.; Prabhu, S. (2015). "Are e-cigarettes a gateway to smoking or a pathway to quitting?". BDJ. 219 (3): 111–115. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.591. ISSN 0007-0610. PMID 26271862.

- ^ Schraufnagel, Dean E.; Blasi, Francesco; Drummond, M. Bradley; Lam, David C. L.; Latif, Ehsan; Rosen, Mark J.; Sansores, Raul; Van Zyl-Smit, Richard (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes. A Position Statement of the Forum of International Respiratory Societies". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 190 (6): 611–618. doi:10.1164/rccm.201407-1198PP. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 25006874.

- ^ Burstyn, I (9 January 2014). "Peering through the mist: systematic review of what the chemistry of contaminants in electronic cigarettes tells us about health risks". BMC Public Health. 14: 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-18. PMC 3937158. PMID 24406205.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cooke, Andrew; Fergeson, Jennifer; Bulkhi, Adeeb; Casale, Thomas B. (2015). "The Electronic Cigarette: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice. 3 (4): 498–505. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2015.05.022. ISSN 2213-2198. PMID 26164573.

- ^ Hildick-Smith, Gordon J.; Pesko, Michael F.; Shearer, Lee; Hughes, Jenna M.; Chang, Jane; Loughlin, Gerald M.; Ipp, Lisa S. (2015). "A Practitioner's Guide to Electronic Cigarettes in the Adolescent Population". Journal of Adolescent Health. 57: 574–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.07.020. ISSN 1054-139X. PMID 26422289.

- "Safety and Health Topics | Flavorings-Related Lung Disease - Health Effects". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- "Safety and Health Topics | Flavorings-Related Lung Disease - Diacetyl". www.osha.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-07.

- Farsalinos, Konstantinos E.; Le Houezec, Jacques (2015-01-01). "Regulation in the face of uncertainty: the evidence on electronic nicotine delivery systems (e-cigarettes)". Risk Management and Healthcare Policy. 8: 157–167. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S62116. ISSN 1179-1594. PMC 4598199. PMID 26457058.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Born, H.; Persky, M.; Kraus, D. H.; Peng, R.; Amin, M. R.; Branski, R. C. (2015). "Electronic Cigarettes: A Primer for Clinicians". Otolaryngology -- Head and Neck Surgery. 153: 5–14. doi:10.1177/0194599815585752. ISSN 0194-5998. PMID 26002957.

- ^ Polosa, R; Campagna, D; Caponnetto, P (September 2015). "What to advise to respiratory patients intending to use electronic cigarettes". Discovery medicine. 20 (109): 155–61. PMID 26463097.

- Collaco, Joseph M. (2015). "Electronic Use and Exposure in the Pediatric Population". JAMA Pediatrics. 169 (2): 177–182. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2898. PMID 25546699.

- ^ McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E – cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. pp. 77–78.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Detailed reference list is located on a separate image page.

- Callahan-Lyon, P. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes: human health effects". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii36 – ii40. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051470. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732161.

- ^ Cervellin, Gianfranco; Borghi, Loris; Mattiuzzi, Camilla; Meschi, Tiziana; Favaloro, Emmanuel; Lippi, Giuseppe (2013). "E-Cigarettes and Cardiovascular Risk: Beyond Science and Mysticism". Seminars in Thrombosis and Hemostasis. 40 (01): 060–065. doi:10.1055/s-0033-1363468. ISSN 0094-6176. PMID 24343348.

- ^ "E-cigarettes--prevention, pulmonary health, and addiction". Dtsch Arztebl Int. 111 (20): 349–55. 2014. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0349. PMC 4047602. PMID 24882626.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Schroeder, M. J.; Hoffman, A. C. (2014). "Electronic cigarettes and nicotine clinical pharmacology". Tobacco Control. 23 (Supplement 2): ii30 – ii35. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051469. ISSN 0964-4563. PMID 24732160.

- FDA (4 May 2009). "FDA 2009 Study Data: Evaluation of e-cigarettes" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration (US) -center for drug evaluation and research. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- "Electronic Cigarettes: Vulnerability of Youth". Pediatr Allergy Immunol Pulmonol. 28 (1): 2–6. 2015. doi:10.1089/ped.2015.0490. PMID 25830075.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - Morris, Pamela B.; Ference, Brian A.; Jahangir, Eiman; Feldman, Dmitriy N.; Ryan, John J.; Bahrami, Hossein; El-Chami, Mikhael F.; Bhakta, Shyam; Winchester, David E.; Al-Mallah, Mouaz H.; Sanchez Shields, Monica; Deedwania, Prakash; Mehta, Laxmi S.; Phan, Binh An P.; Benowitz, Neal L. (2015). "Cardiovascular Effects of Exposure to Cigarette Smoke and Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 66 (12): 1378–1391. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.07.037. ISSN 0735-1097. PMID 26383726.

- Weaver, Michael; Breland, Alison; Spindle, Tory; Eissenberg, Thomas (2014). "Electronic Cigarettes". Journal of Addiction Medicine. 8 (4): 234–240. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000043. ISSN 1932-0620. PMID 25089953.

- SA, Meo; SA, Al Asiri (2014). "Effects of electronic cigarette smoking on human health" (PDF). Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 18 (21): 3315–9. PMID 25487945.

- "E-cigarette Ads and Youth". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (CDC) (6 September 2013). "Notes from the field: electronic cigarette use among middle and high school students – United States, 2011–2012". MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 62 (35): 729–30. PMID 24005229.

- "People who want to quit smoking should consult their GP". Faculty of Public Health.

- Britton, John; Bogdanovica, Ilze (15 May 2014), Electronic cigarettes – A report commissioned by Public Health England (PDF), Public Health England

- "Electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes) or electronic nicotine delivery systems". World Health Organization. 3 June 2014.

- "Position Statement on Electronic Cigarettes [ECs] or Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems [ENDS]" (PDF). The International Union against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. October 2013.

- Caponnetto, Pasquale; Campagna, Davide; Papale, Gabriella; Russo, Cristina; Polosa, Riccardo (2012). "The emerging phenomenon of electronic cigarettes". Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine. 6 (1): 63–74. doi:10.1586/ers.11.92. ISSN 1747-6348. PMID 22283580.

- Offermann, Francis (June 2014). "The Hazards of E-Cigarettes" (PDF). ASHRAE Journal. 56 (6).

- Kleinstreuer, Clement; Feng, Yu (2013). "Lung Deposition Analyses of Inhaled Toxic Aerosols in Conventional and Less Harmful Cigarette Smoke: A Review". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 10 (9): 4454–4485. doi:10.3390/ijerph10094454. ISSN 1660-4601. PMID 24065038.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - Jimenez Ruiz, CA; Solano Reina, S; de Granda Orive, JI; Signes-Costa Minaya, J; de Higes Martinez, E; Riesco Miranda, JA; Altet Gómez, N; Lorza Blasco, JJ; Barrueco Ferrero, M; de Lucas Ramos, P (August 2014). "The electronic cigarette. Official statement of the Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR) on the efficacy, safety and regulation of electronic cigarettes". Archivos de bronconeumologia. 50 (8): 362–7. doi:10.1016/j.arbr.2014.06.007. PMID 24684764.

- "Backgrounder on WHO report on regulation of e-cigarettes and similar products". 26 August 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- John Reid Blackwell. "Avail Vapor offers glimpse into the 'art and science' of e-liquids". Richmond Times-Dispatch. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- Products, Center for Tobacco. "Products, Guidance & Regulations - Deeming – Extending Authorities to Additional Tobacco Products". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-23.

- E-Liquid Manufacturing Standards (PDF). US: AMERICAN E-LIQUID MANUFACTURING STANDARDS ASSOCIATION (AEMSA). 2015. pp. 1–13.

- ^ Suter, Melissa A.; Mastrobattista, Joan; Sachs, Maike; Aagaard, Kjersti (2015). "Is There Evidence for Potential Harm of Electronic Cigarette Use in Pregnancy?". Birth Defects Research Part A: Clinical and Molecular Teratology. 103 (3): 186–195. doi:10.1002/bdra.23333. ISSN 1542-0752. PMID 25366492.

- "Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems (ENDS), including E-cigarettes". New Zealand Ministry of Health.

- Ecology of e-cigarettes

- Environmental footprint of e-cigarettes

- ^ "Electronic cigarette use among smokers slows as perceptions of harm increase". ASH. 22 May 2015. Retrieved 6 August 2015.

- McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. p. 79. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McNeill, A, SC (2015). "E - cigarettes: an evidence update A report commissioned by Public Health England" (PDF). www.gov.uk. UK: Public Health England. pp. 6, 11, 78–80. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Media related to Electronic cigarettes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Electronic cigarettes at Wikimedia Commons

| Cigarettes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Types | |||

| Components | |||

| Peripherals | |||

| Culture | |||

| Health issues | |||

| Related products | |||

| Tobacco industry |

| ||

| Government and the law | |||

| Lists | |||