This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 64.134.226.76 (talk) at 09:46, 9 May 2017 (→Interaction with other religions: Different scholars have different views on contemporariness. The second line is ambiguous. -Jenishc). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 09:46, 9 May 2017 by 64.134.226.76 (talk) (→Interaction with other religions: Different scholars have different views on contemporariness. The second line is ambiguous. -Jenishc)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff) "Jain" redirects here. For other uses, see Jain (disambiguation).

| Jainism | |

|---|---|

The Jain flag The Jain flag | |

| Abbreviation | Jain |

| Scripture | Jain Agamas |

| Other name(s) | Jain dharma |

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy |

EthicsEthics of Jainism

|

| Jain prayers |

| Major figures |

| Major sectsSchools and Branches |

| Jain literature |

| Festivals |

| PilgrimagesTirth |

| Other |

Jainism (/ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/ or /ˈdʒaɪnɪzəm/), traditionally known as Jain Dharma, is an ancient Indian religion belonging to the Śramaṇa tradition. The central tenet is non-violence and respect towards all living beings. The main religious premises of Jainism are ahimsa ("non-violence"), anekantavada ("non-absolutism"), aparigraha ("non-possessiveness") and asceticism ("frugality and abstinence"). Followers of Jainism take five main vows: ahimsa ("non-violence"), satya ("truth"), asteya ("not stealing"), brahmacharya ("celibacy or chastity"), and aparigraha ("non-attachment"). These principles have impacted Jain culture in many ways, such as leading to a predominantly vegetarian lifestyle that avoids harm to animals and their life cycles.

The word "Jain" derives from the Sanskrit word jina (conqueror). A human being who has conquered all inner passions such as attachment, desire, anger, pride, and greed is called Jina. Followers of the path practised and preached by the jinas are known as Jains. Jains trace their history through a succession of twenty-four teachers and revivers of the Jain path known as Tirthankaras. In the current era, this started with Rishabhanatha and concluded with Mahavira. Jains believe that Jainism is an eternal dharma. Parasparopagraho Jivanam ("the function of souls is to help one another") is the motto of Jainism. Namokar Mantra is the most common and basic prayer in Jainism.

Jainism has two major ancient sub-traditions – Digambaras and Svetambaras, and several smaller sub-traditions that emerged in the 2nd millennium CE. The Digambaras and Svetambaras have different views on ascetic practices, gender and which Jain texts can be considered canonical. Jain mendicants are found in all Jain sub-traditions, with laypersons (śrāvakas) supporting the mendicants' spiritual pursuits with resources.

Jainism has between four and five million followers with most Jains residing in India. Outside India, some of the largest Jain communities are present in Canada, Europe, Kenya, the United Kingdom, Suriname, Fiji, and the United States. The two major sects of contemporary Jainism are Digambara and Śvētāmbara. Major Jain festivals include Paryushana and Daslakshana, Mahavir Jayanti, and Diwali.

Main principles

Ahimsa (Non-violence)

Main article: Ahimsa in Jainism

The principle of ahimsa (non-violence or non-injury) is a fundamental tenet of Jainism. It believes that one must abandon all violent activity, and without such a commitment to non-violence all religious behavior is worthless. In Jain theology, it does not matter how correct or defensible the violence may be, one must not kill any being, and "non-violence is one's highest religious duty".

Jain texts such as Acaranga Sutra and Tattvarthasutra state that one must renounce all killing of living beings, whether tiny or large, movable or immovable. Its theology teaches that one must neither kill another living being, nor cause another to kill, nor consent to any killing directly or indirectly. Further Jainism emphasizes non-violence against all beings not only in action, but also in speech and in thought. It states that instead of hate or violence against anyone, "all living creatures must help each other". According to Paul Dundas, violence negatively affects and destroys one soul, particularly when the violence is done with intent, hate or carelessness, or when one indirectly causes or consents to the killing of a human or non-human living being.

The idea of reverence for non-violence (ahimsa) is founded in Hindu and Buddhist canonical texts, and it may have origins in more ancient Brahmanical Vedic thoughts. However, no other Indian religion has developed the non-violence doctrine and its implications on everyday life as has Jainism.

According to Paul Dundas, the theological basis of non-violence as the highest religious duty has been interpreted by some Jain scholars to "not be driven by merit from giving or compassion to other creatures, nor a duty to rescue all creatures", but resulting from "continual self discipline", a cleansing of the soul that leads to one's own spiritual development which ultimately effects one's salvation and release from rebirths. Causing injury to any being in any form creates bad karma which affects one's rebirth, future well being and suffering.

According to Paul Dundas and David Lorenzen, late medieval Jain scholars re-examined the Ahimsa doctrine when one is faced with external threat or violence and justified violence by monks to protect nuns, however, there are no jain records of such claims. According to Dundas, the Jain scholar Jinadatta Suri wrote during a time of Muslim destruction of temples and persecution, that "anybody engaged in a religious activity who was forced to fight and kill somebody would not lose any spiritual merit but instead attain deliverance". However, such examples in Jain texts that condone fighting and killing under certain circumstances, are relatively rare.

Many-sided reality (Anekāntavāda)

Main article: AnekantavadaThe second main principle of Jainism is Anekantavada or Anekantatva. This doctrine states that truth and reality is complex and always has multiple aspects. Reality can be experienced, but it is not possible to totally express it with language. Human attempts to communicate is Naya, or "partial expression of the truth". Language is not Truth, but a means and attempt to express Truth. From Truth, according to Mahavira, language returns and not the other way around. One can experience the truth of a taste, but cannot fully express that taste through language. Any attempts to express the experience is syāt, or valid "in some respect" but it still remains a "perhaps, just one perspective, incomplete". In the same way, spiritual truths are complex, they have multiple aspects, language cannot express their plurality, yet through effort and appropriate karma they can be experienced.

The Anekantavada premises of the Jains is ancient, as evidenced by its mention in Buddhist texts such as the Samaññaphala Sutta. The Jain Agamas suggest that Mahavira's approach to answering all metaphysical philosophical questions was a "qualified yes" (syāt). These texts identify Anekantavada doctrine to be one of the key differences between the teachings of the Mahavira and those of the Buddha. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not" to metaphysical questions. The Mahavira, in contrast, taught his followers to accept both "it is" and "it is not", with "perhaps" qualification and with reconciliation to understand the Absolute Reality. Syādvāda (predication logic) and Nayavāda (perspective epistemology) of Jainism expand on the concept of anekāntavāda. Syādvāda recommends the expression of anekānta by prefixing the epithet syād to every phrase or expression describing the "permanent being". There is no creator God in Jainism, the existence has neither beginning nor end, and the permanent being is conceptualized as jiva (soul) and ajiva (matter) within a dualistic anekantavada framework.

In contemporary times, according to Paul Dundas, the Anekantavada doctrine has been interpreted by many Jains as intending to "promote a universal religious tolerance", and a teaching of "plurality" and "benign attitude to other positions". This is problematic and a misreading of Jain historical texts and Mahavira's teachings, states Dundas. The "many pointedness, multiple perspective" teachings of the Mahavira is a doctrine about the nature of Absolute Reality and human existence, and it is sometimes called "non-absolutism" doctrine. However, it is not a doctrine about tolerating or condoning activities such as sacrificing or killing animals for food, violence against disbelievers or any other living being as "perhaps right". The Five vows for Jain monks and nuns, for example, are strict requirements and there is no "perhaps, just one perspective". Similarly, since ancient times, Jainism co-existed with Buddhism and Hinduism, according to Dundas, but Jainism was highly critical of the knowledge systems and ideologies of its rivals, and vice versa.

Non-attachment (Aparigraha)

Main article: AparigrahaThe third main principle in Jainism is aparigraha which means non-attachment to worldly possessions. For ascetics, Jainism requires a vow of complete non-possession of any property. For Jain laypersons, it recommends limited possession of property that has been honestly earned, and the giving away excess property to charity. According to Natubhai Shah, aparigraha applies to both material and psychic. Material possessions refer to various forms of property. Psychic possessions refer to emotions, likes and dislikes, attachments of any form. Unchecked attachment to possessions is said to result in direct harm to one's personality.

Attachments to the material or emotional possessions are viewed in Jainism as what leads to passions, which in turn leads to violence. Per the aparigraha principle, a Jain monk or nun is expected to be homeless and family-less with no emotional longings or attachments. The ascetic is a wandering mendicant in the Digambara tradition, or a resident mendicant in the Svetambara tradition.

In addition, Jain texts mention that "attachment to possessions" (parigraha) is of two kinds: attachment to internal possessions (ābhyantara parigraha), and attachment to external possessions (bāhya parigraha). For internal possessions, Jainism identifies four key passions of the mind (kashaya): anger, pride (ego), deceitfulness, and greed. Jainism recommends conquering anger by forgiveness, pride by humility, deceitfulness by straightforwardness, and greed by contentment. In addition to the four passions of the mind, the remaining ten internal passions are: wrong belief, the three sex-passions (male sex-passion, female sex-passion, neuter sex-passion), and the six defects (laughter, like, dislike, sorrow, fear, disgust).

Asceticism

Main article: AsceticismOf all the major Indian religions, Jainism has had the strongest austerities-driven ascetic tradition, and it is an essential part of a mendicant's spiritual pursuits. Ascetic life may include nakedness symbolizing non-possession of even clothes, fasting, body mortification, penance and other austerities, in order to burn away past karma and stop producing new karma, both of which are believed in Jainism to be essential for reaching siddha and moksha (liberation from rebirths, salvation).

Jain texts such as Tattvartha Sutra and Uttaradhyayana Sutra discuss ascetic austerities to great lengths and formulations. Six outer and six inner practices are most common, and oft repeated in later Jain texts. According to John Cort, outer austerities include complete fasting, eating limited amounts, eating restricted items, abstaining from tasty foods, mortifying the flesh and guarding the flesh (avoiding anything that is a source of temptation). Inner austerities include expiatiom confession, respecting and assisting mendicants, studying, meditation and ignoring bodily wants in order to abandon the body.

The list of internal and external austerities in Jainism vary with the text and tradition. Asceticism is viewed as a means to control desires, and a means to purify the jiva (soul). The Tirthankaras of Jainism, such as the Mahavira (Vardhamana) set an example of leading an ascetic life by performing severe austeries for twelve years.

Practices

Jain ethics and Five vows

Main article: Ethics of Jainism See also: Yamas § Five YamasJainism teaches five ethical duties, which it calls Five vows. These are called anuvratas (small vows) for Jain layperson, and mahavratas (great vows) for Jain mendicants. For both, its moral precepts preface that the Jain has access to a guru (teacher, counsellor), deva (Jina, god), doctrine, and that the individual is free from five offences: doubts about the faith, indecisiveness about the truths of Jainism, sincere desire for Jain teachings, recognition of fellow Jains, and admiration for their spiritual pursuits. Such a person undertakes the following Five vows of Jainism:

- Ahimsa: Ahimsa means intentional "non-violence " or "noninjury". The first major vow taken by Jains is to cause no harm to other human beings, as well as all living beings. This is the highest ethical duty in Jainism, and it applies not only to one's actions, but demands that one be non-violent in one's speech and thoughts.

- Satya: Satya means "truth". This vow is to always speak the truth, neither lie, nor speak what is not true, do not encourage others or approve anyone who speaks the untruth.

- Asteya: Asteya means "not stealing". A Jain layperson should not take anything that is not willingly given. A Jain mendicant should additionally ask for permission to take it if something is being given.

- Brahmacharya: Brahmacharya means "celibacy", that is abstinence from sex and sensual pleasures for Jain monks and nuns. For laypersons, brahmacharya vow means chastity, faithfulness to one's partner.

- Aparigraha: Aparigraha means "non-possessiveness". This includes non-attachment to material and psychological possessions, avoiding craving and greed. Jain monks and nuns completely renounce property and social relations, own nothing and are attached to no one.

- Supplementary vows and Sallekhana

Jainism also prescribes seven supplementary vows and a last sallekhana vow, which is practised mostly by monks and nuns. The supplementary vows include three guņa vratas ("merit vows") and four śikşā vratas.

The Sallekhana (or Santhara) vow is observed at the end of life most commonly by Jain monks and nuns. In this vow, there is voluntary and gradual reduction of food and liquid intake to end one's life by choice and with dispassion, This is believed in Jainism to reduce negative karma that affects a soul's future rebirths.

Food and fasting

Main articles: Jain vegetarianism and Fasting in JainismThe practice of non-violence towards all living beings has led to Jain culture being vegetarian, with most Jains practicing lacto vegetarianism (no eggs). If there is violence against animals during the production of dairy products, veganism is encouraged. Jain monks and nuns do not eat root vegetables such as potatoes, onions and garlic because tiny organisms are injured when the plant is pulled up, and because a bulb or tuber's ability to sprout is seen as characteristic of a living being.

Jains fast on different occasions throughout the year, particularly during festivals. This practice is called upavasa, tapasya or vrata. According to Singh, this takes on various forms and may be practised based on one's ability. Some examples include Digambara fasting for Dasa-laksana-parvan where a Jain layperson eats only one or two meals per day, drinking only boiled water for ten days, or a complete fast on the first and last day of the festival. These practices bring the layperson to mimic the practices of a Jain mendicant during the festival. A similar practice is found among Svetambara Jains on eight day paryusana with samvatsari-pratikramana.

The fasting practice is believed to remove karma from one's soul and to gain merit (punya). A "one day" fast in Jain tradition lasts about 36 hours, starting at sunset before the day of fast and ending 48 minutes after the sunrise the day after. Among laypeople, fasting is more commonly observed by women, where it is believed that this shows her piety, religious purity, gains her and her family prestige, leads to merit earning and helps ensure future well being for her family. Some religious fasts are observed as a group, where Jain women socially bond and support each other. Long fasts are celebrated by friends and families with special ceremonies.

Meditation

Main article: Jain meditationAccording to Paul Dundas, Jainism considers meditation (dhyana) a necessary practice, but its goals are very different than those in Buddhism and Hinduism. In Jainism, meditation is concerned more with stopping karmic attachments and activity, not as a means to transformational insights or self-realization in other Indian religions. Meditation in early Jain literature is a form of austerity and ascetic practice in Jainism, while in late medieval era the practice adopts ideas from other Indian traditions. According to Paul Dundas, this lack of meditative practices in early Jain texts may be because substantial portions of ancient Jain texts were lost.

According to Padmanabh Jaini, Sāmāyika is a practice of "brief periods in meditation" in Jainism which is a part of siksavrata (ritual restraint). The goal of Sāmāyika is to achieve equanimity, and it is the second siksavrata. The samayika ritual is practiced at least three times a day by mendicants, while a layperson includes it with other ritual practices such as Puja in a Jain temple and doing charity work. According to Johnson, as well as Jaini, samayika connotes more than meditation, and for a Jain householder is the voluntary ritual practice of "assuming temporary ascetic status".

According to Johnson's interpretation of Pravacanasara by Kundakunda, a Jain mendicant should meditate on "I, the pure self". Anyone who considers his body or possessions as "I am this, this is mine" is on the wrong road, while one who meditates, thinking the antithesis and "I am not others, they are not mine, I am one knowledge" is on the right road to meditating on the "soul, the pure self".

Rituals and worship

Main article: Jain rituals

There are many rituals in Jainism's various sects. According to Dundas, the ritualistic lay path among Svetambara Jains is "heavily imbued with ascetic values", where the rituals either revere or celebrate the ascetic life of Tirthankaras, or mendicants, or progessively get closer to psychologically and physically living ever more like an ascetic. The ultimate ritual is sallekhana, a religious death through ascetic abandonment of food and drinks. The Digambara Jains follow the same theme, but the details differ from Svetambaras, and according to Dundas, the life cycle and religious rituals are closer to the liturgy found among Hindu traditions. The overlap in Jain and Hindu rituals is largely in the life cycle (rites-of-passage) rituals, states Padmanabh Jaini, and likely one that developed over time because Jains and Hindus societies overlapped, and rituals were viewed as necessary and secular ceremonies.

Jains do not believe in a creator god, but do ritually worship numerous deities. The Jinas are prominent and a large focus of this ritualism, but they are not the only deva in Jainism. A Jina as deva is not an avatar (incarnation) in Jainism, but the highest state of omniscience that an ascetic Tirthankara achieved. Some of Jaina rituals remember the five life events of the Tirthankaras called the Panch Kalyanaka are rituals such as the Panch Kalyanaka Pratishtha Mahotsava, Panch Kalyanaka Puja, and Snatrapuja.

The basic worship ritual practised by Jains is darsana ("seeing") of deva, which includes Jina,, or other yaksas, gods and goddesses such as Brahmadeva, 52 Viras, Padmavati and Ambika. The Terapanthi sub-tradition of Digambaras do not worship many of the deities popular among mainstream Digambaras, and they limit their ritual worship to Tirthankaras. The worship ritual is called the devapuja, is found in all Jaina subtraditions, which share common features. Typically, the Jaina layperson enters the temple inner sanctum in simple clothing and bare feet, with a plate filled with offerings, bows down, says the namaskara, completes his or her litany and prayers, sometimes is assisted by the temple priest, leaves the offerings and then departs.

Jain practices include performing abhisheka ("ceremonial bath") of the images. Some Jain sects employ a pujari (also called upadhye) for rituals, who may be a non-Jain (a Hindu), to perform special rituals and other priestly duties at the temple. More elaborate worship includes ritual offerings such as rice, fresh and dry fruits, flowers, sweets, and money. Some may light up a lamp with camphor and make auspicious marks with sandalwood paste. Devotees also recite Jain texts, particularly the life stories of the Tirthankaras.

The traditional Jains, like Buddhists and Hindus, believe in the efficacy of mantras and that certain sounds and words are inherently auspicious, powerful and spiritual. The most famous of the mantras, broadly accepted in various sects of Jainism, is the "five homage" (panca namaskara) mantra which is believed to be eternal and existent since the first ford-maker's time.

Festivals

Main article: Jain festivals| This section may contain citations that do not verify the text. Please check for citation inaccuracies. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Paryushana or Daslakshana is the most important annual event for Jains, and is usually celebrated in August or September. It lasts eight to ten days and is a time when lay people increase their level of spiritual intensity often using fasting and prayer/meditation to help. The five main vows are emphasized during this time. There are no set rules, and followers are encouraged to practise according to their ability and desires. The last day involves a focused prayer/meditation session known as Samvatsari Pratikramana. At the conclusion of the festival, followers ask for forgiveness from others for any offenses committed during the last year. Forgiveness is asked by saying Micchami Dukkadam or Khamat Khamna to others, which means, "If I have offended you in any way, knowingly or unknowingly, in thought, word or action, then I seek your forgiveness." The literal meaning of Paryushana is "abiding" or "coming together".

Mahavir Jayanti, the birth of Mahāvīra, the last tirthankara of this era, is usually celebrated in late March or early April based on the lunar calendar. Diwali is a festival that marks the anniversary of Mahāvīra's attainment of moksha. The Hindu festival of Diwali is also celebrated on the same date (Kartika Amavasya). Diwali is celebrated in an atmosphere of: austerity, simplicity, serenity, equity, calmness, charity, philanthropy, and environmental consciousness. Jain temples, homes, offices, and shops are decorated with lights and diyas ("small oil lamps"). The lights are symbolic of knowledge or removal of ignorance. Sweets are often distributed. On Diwali morning, Nirvan Ladoo is offered after praying to Mahāvīra in all Jain temples across the world. The Jain new year starts right after Diwali. Some other festivals celebrated by Jains are Akshaya Tritiya and Raksha Bandhan.

Pilgrimages

Main article: Tirtha (Jainism)

Jain Tirtha ("pilgrim") sites are divided into the following categories:

- Siddhakshetra – Site of the moksha of an arihant (kevalin) or Tirthankara, such as: Ashtapada, Shikharji, Girnar, Pawapuri, Palitana, Mangi-Tungi, and Champapuri (capital of Anga).

- Atishayakshetra – Locations where divine events have occurred, such as: Mahavirji, Rishabhdeo, Kundalpur, Tijara, and Aharji.

- Puranakshetra – Places associated with lives of great men, such as: Ayodhya, Vidisha, Hastinapur, and Rajgir.

- Gyanakshetra – Places associated with famous acharyas, or centers of learning, such as Shravanabelagola.

Monasticism

Main article: Jain monasticism| This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (May 2017) |

Acharya Gyansagar, a prominent Digambara Acharya (the head of a monastic order)

Acharya Gyansagar, a prominent Digambara Acharya (the head of a monastic order) Stanakvasi monk

Stanakvasi monk

Digambara monks and nuns carry a broom-like object, called a picchi (made from fallen peacock feathers) to sweep the ground ahead of them or before sitting down to avoid inadvertently crushing small insects. Svetambara monks carry a rajoharan (a broom-like object made from dense, thick thread strands). Jain monks have to follow six duties known as avashyakas.

Jainism has a four-fold order that consists of muni ("male ascetics'), aryika ("female ascetics"), śrāvaka ("laymen"), and śrāvikā ("laywoman").

Beliefs and philosophy

Main article: Jain philosophy| Part of a series on |

| Jain philosophy |

|---|

|

| Concepts |

|

| People |

|

| This section possibly contains original research. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Dravya ("Substance")

Main article: Dravya

According to Jainism, there are six simple substances in existence: Soul, Matter, Time, Space, Dharma and Adharma. Jain philosophers distinguish a substance from a body (or thing) by declaring the former to be a simple element or reality and the latter a compound of one or more substances or atoms. They claim that there can be a partial or total destruction of a body or thing, but no substance can ever be destroyed. According to Champat Rai Jain:

Substance is the sub-strate of qualities which cannot exist apart from it, for instance, the quality of fluidity, moisture, and the like only exist in water and cannot be conceived separately from it. It is neither possible to create nor to destroy a substance, which means that there never was a time when the existing substances were not, nor shall they ever cease to be.

Jīva ("Soul")

Main article: Jīva (Jainism)Jain philosophy is the oldest Indian philosophy that completely separates body (matter) from the soul (consciousness). Jains maintain that all living beings are really soul, intrinsically perfect and immortal. Souls in saṃsāra (that is, liability to repeated births and deaths) are said to be imprisoned in the body.

The soul-substance, called Jīva in Jainism, is distinguished from the remaining five substances (Matter, Time, Space, Dharma and Adharma), collectively called ajīva, by the intelligence with which the soul-substance is endowed, and which is not found in the other substances. The nature of the soul-substance is said to be freedom. In its modifications, it is said to be the subject of knowledge and enjoyment, or suffering, in varying degrees, according to its circumstances. Jain texts expound that all living beings are really soul, intrinsically perfect and immortal. Souls in transmigration are said to be embodied in the body as if in a prison.

Ajīva ("Non-Soul")

Main article: Ajiva- Matter (Pudgala) is considered a non-intelligent substance consisting of an infinity of particles or atoms which are eternal. These atoms are said to possess sensible qualities, namely, taste, smell, color and, in certain forms, touch and sound.

- Time is said to be the cause of continuity and succession. It is of two kinds: nishchaya and vyavhāra.

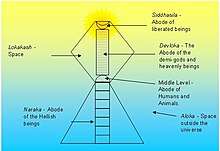

- Space (akāśa)- Space is divided by the Jainas into two parts, namely, the lokākāśa, that is the space occupied by the universe, and the alokākāśa, the portion beyond the universe. The lokākāśa is the portion in which are to be found the remaining five substances, i.e., Souls, Matter, Time, Dharma and Adharma; the alokākāśa is the region of pure space containing no other substance and lying stretched on all sides beyond bounds of the three worlds (the entire universe).

- Dharma and Adharma are substances said to be helpful in the motion and stationary states of things, respectively – the former enabling them to move from place to place and the latter to come to rest from the condition of motion.

Tattva ("Reality")

Main article: Tattva (Jainism)

Jain philosophy is based on seven fundamentals which are known as tattva, which attempt to explain the nature of karmas and provide solutions for the ultimate goal of liberation of the soul (moksha): These are:

- Jīva – the soul, which is characterized by consciousness

- Ajīva – non-living entities that consist of matter, space and time

- Āsrava ("influx") – the inflow of auspicious and evil karmic matter into the soul

- Bandha ("bondage") – mutual intermingling of the soul and karmas. The karma masks the jiva and restricts it from reaching its true potential of perfect knowledge and perception.

- Saṃvara ("stoppage") – obstruction of the inflow of karmic matter into the soul

- Nirjarā ("gradual dissociation") – the separation or falling off of part of karmic matter from the soul

- Moksha ("liberation") – complete annihilation of all karmic matter (bound with any particular soul)

Soul and Karma

Main article: Karma in JainismAccording to Jain belief, souls, intrinsically pure, possess the qualities of infinite knowledge, infinite perception, infinite bliss, and infinite energy in their ideal state. In reality, however, these qualities are found to be obstructed due to the soul's association with karmic matter. The ultimate goal in Jainism is the realisation of reality.

The relationship between the soul and karma is explained by the analogy of gold. Gold is always found mixed with impurities in its natural state. Similarly, the ideal pure state of the soul is always mixed with the impurities of karma. Just like gold, purification of the soul may be achieved if the proper methods of refining are applied. The Jain karmic theory is used to attach responsibility to individual action and is cited to explain inequalities, suffering, and pain. Tirthankara-nama-karma is a special type of karma, bondage of which raises a soul to the supreme status of a tirthankara.

Saṃsāra

Main article: Saṃsāra (Jainism)

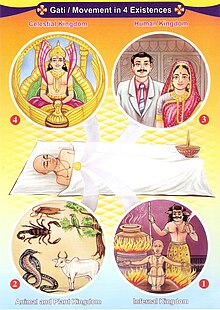

The conceptual framework of the Saṃsāra doctrine differs between the Jainism traditions and other Indian religions. For instance, in Jaina traditions, soul (jiva) is accepted as a truth, as is assumed in the Hindu traditions, but not assumed in the Buddhist traditions. However, Saṃsāra or the cycle of rebirths, has a definite beginning and end in Jainism. The Jaina theosophy, unlike Hindu and Buddhist theosophies, asserts that each soul passes through 8,400,000 birth-situations, as they circle through Saṃsāra. As the soul cycles, states Padmanabh Jaini, Jainism traditions believe that it goes through five types of bodies: earth bodies, water bodies, fire bodies, air bodies and vegetable lives. With all human and non-human activities, such as rainfall, agriculture, eating and even breathing, minuscule living beings are taking birth or dying, their souls are believed to be constantly changing bodies. Perturbing, harming or killing any life form, including any human being, is considered a sin in Jainism, with negative karmic effects.

Souls begin their journey in a primordial state, and exist in a state of consciousness continuum that is constantly evolving through Saṃsāra. Some evolve to a higher state, some regress asserts the Jaina theory, a movement that is driven by the karma. Further, Jaina traditions believe that there exist Abhavya (incapable), or a class of souls that can never attain moksha (liberation). The Abhavya state of soul is entered after an intentional and shockingly evil act. Jainism considers souls as pluralistic each in a karma-samsara cycle, and does not subscribe to Advaita style nondualism of Hinduism, or Advaya style nondualism of Buddhism.

A liberated soul in Jainism is one who has gone beyond Saṃsāra, is at the apex, is omniscient, remains there eternally, and is known as a Siddha.

Body and matter

Main article: Vitalism (Jainism)

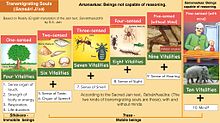

Jain texts state that there are ten vitalities or life-principles: the five senses, energy, respiration, life-duration, the organ of speech, and the mind. The table below summarizes the vitalities that living beings possess in accordance with their senses.

| Senses | Number of vitalities | Vitalities |

|---|---|---|

| One-sensed beings | Four | Sense organ of touch, strength of body or energy, respiration, and life-duration. |

| Two-sensed beings | Six | The sense of taste and the organ of speech in addition to the former four. |

| Three-sensed beings | Seven | The sense of smell in addition to the former six. |

| Four-sensed beings | Eight | The sense of sight in addition to the former seven. |

| Five-sensed beings |

Nine | The sense of hearing in addition to the former eight. |

| Ten | Mind in addition to the above-mentioned nine vitalities. |

Cosmology

Main article: Jain cosmology

Jain texts propound that the universe was never created, nor will it ever cease to exist. It is independent and self-sufficient, and does not require any superior power to govern it. Elaborate descriptions of the shape and function of the physical and metaphysical universe, and its constituents, are provided in the canonical Jain texts, in commentaries, and in the writings of the Jain philosopher-monks.

According to the Jain texts, the universe is divided into three parts, the upper, middle, and lower worlds, called respectively urdhva loka, madhya loka, and adho loka. It is made up of six constituents: Jīva, ("the living entity"); Pudgala, ("matter"); Dharma tattva, ("the substance responsible for motion"); Adharma tattva, ("the substance responsible for rest"); Akāśa, ("space"); and Kāla, ("time").

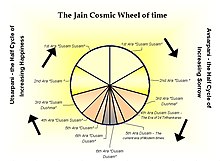

Kāla ("time") is without beginning and eternal; the cosmic wheel of time, called kālachakra, rotates ceaselessly. According to Jain texts, in this part of the universe, there is rise and fall during the six periods of the two aeons of regeneration and degeneration. Thus, the worldly cycle of time is divided into two parts or half-cycles, ascending utsarpiṇī ("ascending") and avasarpiṇī ("descending"). Utsarpiṇī is a period of progressive prosperity, where happiness increases, while avasarpiṇī is a period of increasing sorrow and immorality. According to Jain cosmology, it is currently the 5th ara of avasarpiṇī (half time cycle of degeneration). As of 2016, exactly 2,538 years have elapsed, and 18,460 years are still left. The present age is one of sorrow and misery. In this ara, though religion is practised in lax and diluted form, no liberation is possible. At the end of this ara, even the Jain religion will disappear, only to appear again with the advent of the first Tīrthankara after the 42,000 years of next utsarpiṇī are over.

The following table depicts the six aras of avasarpiṇī

| Name of the Ara | Degree of happiness | Duration of Ara | Average height of people | Average lifespan of people |

| Sukhama-sukhamā | Utmost happiness and no sorrow | 400 trillion sāgaropamas | Six miles tall | Three palyopama years |

| Sukhamā | Moderate happiness and no sorrow | 300 trillion sāgaropamas | Four miles tall | Two palyopama Years |

| Sukhama-dukhamā | Happiness with very little sorrow | 200 trillion sāgaropamas | Two miles tall | One palyopama years |

| Dukhama-sukhamā | Happiness with little sorrow | 100 trillion sāgaropamas | 1500 meters | 705.6 quintillion years |

| Dukhamā | Sorrow with very little Happiness | 21,000 years | 6 feet | 130 years maximum |

| Dukhama- dukhamā | Extreme sorrow and misery | 21,000 years | 2 feet | 16–20 years |

This trend will start reversing at the onset of utsarpinī kāl with the Dukhama-dukhamā ara being the first ara of utsarpinī (half-time cycle of regeneration).

According to Jain texts, sixty-three illustrious beings, called śalākāpuruṣas, are born on this earth in every Dukhama-sukhamā ara. The Jain universal history is a compilation of the deeds of these illustrious persons. They comprise twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras, twelve chakravartins, nine balabhadra, nine narayana, and nine pratinarayana.

A chakravartī is an emperor of the world and lord of the material realm. Though he possesses worldly power, he often finds his ambitions dwarfed by the vastness of the cosmos. Jain puranas give a list of twelve chakravartins ("universal monarchs"). They are golden in complexion. One of the greatest chakravartins mentioned in Jain scriptures is Bharata Chakravartin. Jain texts like Harivamsa Purana and Hindu Texts like Vishnu Purana mention that India came to be known as Bharatavarsha in his memory.

There are nine sets of balabhadra, narayana, and pratinarayana. The balabhadra and narayana are brothers. Balabhadra are nonviolent heroes, narayana are violent heroes, and pratinarayana can be described as villains. According to the legends, the narayana ultimately kill the pratinarayana. Of the nine balabhadra, eight attain liberation and the last goes to heaven. On death, the narayana go to hell because of their violent exploits, even if these were intended to uphold righteousness.

Epistemology

Main article: Jain epistemologyIn Jainism, jnāna ("knowledge") is said to be of five kinds—Kevala Jnana ("Omniscience"), Śrutu Jñāna ("Scriptural Knowledge"), Mati Jñāna ("Sensory Knowledge"), Avadhi Jñāna ("Clairvoyance"), and Manah prayāya Jñāna ("Telepathy"). According to the Jain text Tattvartha sutra, the first two are indirect knowledge and the remaining three are direct knowledge. Jains maintain that knowledge is the nature of the soul. According to Champat Rai Jain, "Knowledge is the nature of the soul. If it were not the nature of the soul, it would be either the nature of the not-soul, or of nothing whatsoever. But in the former case, the unconscious would become the conscious, and the soul would be unable to know itself or any one else, for it would then be devoid of consciousness; and, in the latter, there would be no knowledge, nor conscious beings in existence, which, happily, is not the case."

God

| This section may contain citations that do not verify the text. Please check for citation inaccuracies. (April 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Jain texts reject the idea of a creator or destroyer God and postulate an eternal universe. Jain cosmology divides the worldly cycle of time into two parts (avasarpiṇī and utsarpiṇī). According to Jain belief, in every half-cycle of time, twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras grace this part of the Universe to teach the unchanging doctrine of right faith, right knowledge and right conduct. The word tīrthankara signifies the founder of a tirtha, which means a fordable passage across a sea. The Tīrthaṅkaras show the 'fordable path' across the sea of interminable births and deaths. Rishabhanatha is said to be the first Tīrthankara of the present half-cycle (avasarpiṇī). Mahāvīra (6th century BC) is revered as the last tīrthankara of avasarpiṇī. Though Jain texts explain that Jainism has always existed and will always exist, modern historians place the earliest evidence of Jainism in the 9th century BC.

In Jainism, perfect souls with the body are called arihant ("victors") and perfect souls without the body are called Siddhas ("liberated souls"). Tirthankara is an arihant who helps others to achieve liberation. Tirthankaras become role models for those seeking liberation. They are also called human spiritual guides. Jainism has been described as a transtheistic religion, as it does not teach dependency on any supreme being for enlightenment.

Salvation, liberation

Main articles: Moksha (Jainism), Ratnatraya, and Gunasthana

According to Jainism, the following three jewels constitute the path to liberation:

- Samyak darśana ("Correct View")– Belief in substances like soul (Jīva) and non-soul without delusions.

- Samyak jnana ("Correct Knowledge" – Knowledge of the substances (tattvas) without any doubt or misapprehension.

- Samyak charitra (Correct Conduct) – Being free from attachment, a right believer does not commit hiṃsā (injury).

Jain texts often add samyak tap (Correct Asceticism) as the fourth jewel, thereby emphasizing their belief in ascetic practices as the means to liberation (moksha). The four jewels of orthodox Jain ideology are called moksha marg.

In Jain philosophy, the fourteen stages through which a soul must pass in order to attain liberation (moksha) are called Gunasthāna. These are:

| Gunasthāna | Explanation |

|---|---|

| 1. Mithyātva | Gross ignorance. The stage of wrong believer |

| 2. Sasādana | Vanishing faith, i.e., the condition of the mind while actually falling down from the fourth stage to the first stage. |

| 3. Mishradrshti | Mixed faith and false belief. |

| 4. Avirata samyagdrshti | Right Faith unaccompanied by Right Conduct. |

| 5. Deśavirata | The stage of partial self-control (Śrāvaka) |

| 6. Pramatta Sanyati | First step of life as a Jain muni (monk). The stage of complete self-discipline, although sometimes brought into wavering through negligence. |

| 7. Apramatta Sanyati | Complete observance of Mahavratas (Major Vows) |

| 8. Apūrvakaraņa | New channels of thought. |

| 9. Anivāttibādara-sāmparāya | Advanced thought-activity |

| 10. Sukshma sāmparāya | Slight greed left to be controlled or destroyed. |

| 11. Upaśānta-kasāya | The passions are still associated with the soul, but they are temporarily out of effect on the soul. |

| 12. Ksīna kasāya | Desirelessness, i.e., complete eradication of greed |

| 13. Sayoga kevali (Arihant) | Omniscience with vibrations. Sa means "with" and yoga refers to the three channels of activity, i.e., mind, speech and body. |

| 14. Ayoga kevali | The stage of omniscience without any activity. This stage is followed by the soul's destruction of the aghātiā karmas. |

At the second-to-last stage, a soul destroys all inimical karmas, including the knowledge-obscuring karma which results in the manifestation of infinite knowledge (Kevala Jnana), which is said to be the true nature of every soul.

Those who pass the last stage are called Siddha and become fully established in Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct. According to Jain texts, after the total destruction of karmas the released pure soul (Siddha) goes up to the summit of universe (Siddhashila) and dwells there in eternal bliss.

The soul removes its ignorance (mithyatva) at the 4th stage, vowlessness (avirati) at the 6th stage, passions (kashaya) at the 12th stage, and yoga (activities of body, mind and speech) at the 14th stage, and thus attains liberation.

Traditions and sects

Main article: Jain schools and branches Idol depiction in Digambar

Idol depiction in Digambar Idol depiction in Svetambara

Idol depiction in Svetambara

The Jain community is divided into two major denominations, Digambara and Śvētāmbara. Monks of the Digambara ("sky-clad") tradition do not wear clothes. Female monastics of the Digambara sect wear unstitched plain white sarees and are referred to as Aryikas. Śvētāmbara ("white-clad") monastics on the other hand, wear white seamless clothes.

During Chandragupta Maurya's reign, Acharya Bhadrabahu, the last śruta-kevali (all knowing by hearsay, i.e. indirectly) predicted a twelve-year-long famine and moved to Karnataka with his disciples. Sthulabhadra, a pupil of Acharya Bhadrabahu, stayed in Magadha. After the famine, when followers of Acharya Bhadrabahu returned, they found that those who had stayed at Magadha had started wearing white clothes, which was unacceptable to the others who remained naked. This is how the Digambara and Śvētāmbara schism began, with the former being naked while the latter wore white clothes. Digambara saw this as being opposed to the Jain tenets which, according to them, required complete nudity. Evidence of gymnosophists ("naked philosophers") in Greek records as early as the fourth century BCE supports the claim of the Digambaras that they have preserved the ancient Śramaṇa practice.

The earliest record of Digambara beliefs is contained in the Prakrit Suttapahuda of the Digambara Acharya, Kundakunda (c. 2nd century CE). Digambaras believe that Mahavira remained unmarried, whereas Śvētāmbara believe that Mahavira married a woman who bore him a daughter. The two sects also differ on the origin of Trishala, Mahavira's mother.

Excavations at Mathura revealed Jain statues from the time of the Kushan Empire (c. 1st century CE). Tirthankara represented without clothes, and monks with cloth wrapped around the left arm, are identified as the Ardhaphalaka ("half-clothed") mentioned in texts. The Yapaniyas, believed to have originated from the Ardhaphalaka, followed Digambara nudity along with several Śvētāmbara beliefs.

Digambar tradition is divided into two main monastic orders Mula Sangh and the Kashtha Sangh, both led by Bhattarakas. In opposition to Bhattarakas and some rituals, Digambara Terapanth emerged in the 17th century.

Svetambara tradition is divided into Murtipujaka and Sthanakvasi. Sthanakvasi opposes idol worship. The sect emerged in the 17th century and was led by Lonka Shaha. Murtipujaka builds temples and worships idols. The Svetambara Terapanth emerged from Sthanakvasi as a reformist movement led by Acharya Bhikshu in 1760. This sect is also non-idolatrous.

In 20th century, new religious movements around the teachings of Kanji Swami and Shrimad Rajchandra emerged.

Gender and spiritual liberation

A male human being is considered closest to the apex with the potential to achieve liberation, particularly through asceticism. In the Digambara traditional belief, women must gain karmic merit, to be reborn as man, and only then can they achieve spiritual liberation. However, this view has been historically debated within Jainism and different Jaina sects have expressed different views, particularly the Svetambara sect that believes that women too can achieve spritual liberation from rebirths in Saṃsāra. The Śvētāmbaras state the 19th Tirthankara Māllīnātha was female. However, Digambara reject this, and worship Mallinatha as a male.

Scriptures and texts

Main articles: Jain literature and Jain Agamas

After the attainment of omniscience, the tirthankara discourses in a divine preaching hall called samavasarana. The discourse delivered is called Śhrut Jnāna and comprises eleven angas and fourteen purvas. The discourse is recorded by Ganadharas (chief disciples), and is composed of twelve angas ("departments"). It is generally represented by a tree with twelve branches.

Historically, the Jain Agamas were based on the teachings of Mahāvīra, the last Tīrthankara of the present half cycle. The Agamas were memorised and passed on through the ages. They were lost because of famine that caused the death of several saints within a thousand years of Mahāvīra's death. These comprise thirty-two works: eleven angās, twelve upanga āgamas, four chedasūtras, four mūlasūtras, and the last, a pratikraman, or Avashyak sūtra.

-

Kalpasutra folio on Mahavira Nirvana. Note the crescent shaped Siddhashila, a place where all siddhas reside after Nirvana

Kalpasutra folio on Mahavira Nirvana. Note the crescent shaped Siddhashila, a place where all siddhas reside after Nirvana

-

A King and a Monk (recto); Text (verso); Folio from an Uttaradhyayana Sutra, LACMA

A King and a Monk (recto); Text (verso); Folio from an Uttaradhyayana Sutra, LACMA

-

Depiction of Pañca-Parameṣṭhi on Siddhaśilā from the Saṁgrahaṇīratna by Śrīcandra in Prakrit, 17th century British Library

Depiction of Pañca-Parameṣṭhi on Siddhaśilā from the Saṁgrahaṇīratna by Śrīcandra in Prakrit, 17th century British Library

-

The Suryaprajnaptisutra, an astronomical work dating to the 3rd or 4th century BC, written in Jain Prakrit language (in Devanagari book script), c. 1500 AD.

The Suryaprajnaptisutra, an astronomical work dating to the 3rd or 4th century BC, written in Jain Prakrit language (in Devanagari book script), c. 1500 AD.

The Digambara sect of Jainism maintains that the Agamas were lost during the same famine in which the purvas were lost. According to the Digambaras, Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. Later on, some learned Āchāryas started to restore, compile, and put into written words the teachings of Mahāvīra, that were the subject matter of Aagamas. In the first century CE, Āchārya Dharasen guided two Āchāryas, Āchārya Pushpadant and Āchārya Bhutabali, to put these teachings in written form. The two Āchāryas wrote Ṣaṭkhaṅḍāgama, among the oldest-known Digambara Jain texts, on palm leaves. Digambara texts are classified under four headings, namely: Pratham-anuyoga, Charn-anuyoga, Karan-anuyoga and Dravya-anuyoga (texts expounding reality, i.e. tattva).

Some of the most famous Jain texts include Samayasara, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, and Niyamasara.

Some scholars believe that the author of the oldest extant work of literature in Tamil (3rd century BCE), the Tolkāppiyam, was a Jain. The Tirukkuṛaḷ by Thiruvalluvar is considered to be the work of a Jain by scholars such as Ka. Naa. Subramanyam, V. Kalyanasundarnar, Vaiyapuri Pillai, and P. S. Sundaram. It emphatically supports vegetarianism in chapter 26 and states that giving up animal sacrifice is worth more than a thousand offerings in fire in verse 259.

The Nālaṭiyār (a famous Tamil poetic work) was composed by Jain monks from South India in 100–500.

The Silappatikaram, the earliest surviving epic in Tamil literature, was written by a Jain, Ilango Adigal. This epic is a major work in Tamil literature, describing the historical events of its time and of the then-prevailing religions, Jainism, Buddhism, and Shaivism.

According to George L. Hart, who holds the endowed Chair in Tamil Studies at the University of California, Berkeley, the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies" was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai: "There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 A.D. in Madurai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the Sangam legend."

Jain scholars and poets authored Tamil classics of the Sangam period, such as the Cīvaka Cintāmaṇi and Nālaṭiyār. In the beginning of the mediaeval period, between the 9th and 13th centuries, Kannada authors were predominantly Jains and Lingayatis. Jains were the earliest known cultivators of Kannada literature, which they dominated until the 12th century. Jains wrote about the Tīrthaṅkaras and other aspects of the faith. Adikavi Pampa is one of the greatest Kannada poets. Court poet to the Chalukya king Arikesari, a Rashtrakuta feudatory, he is best known for his Vikramarjuna Vijaya.

Jain manuscript libraries are the oldest in the country. Jain libraries, including those at Patan and Jaisalmer, have a large number of well-preserved manuscripts.

History

Main article: History of Jainism

Origins

See also: Timeline of Jainism and ŚramaṇaThe origins of Jainism are obscure. The Jains claim their religion to be eternal, and consider Rishabhanatha to be the founder and first Tirthankar in the present time-cycle. According to one hypothesis, such as by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, the first vice president of India, Jainism was in existence before the Vedas were composed. According to historians, of the 24 Tirthankaras, the first 22 were mythical figures who are believed in Jainism to have lived more than 85,000 years ago, each of whom were five to hundred times taller than average human beings and lived for thousands of years. The 23rd Tirthankara Parshvanatha is generally accepted to be based on an ancient historic human being.

Jainism, like Buddhism, is one of the Sramana traditions of ancient India, those that rejected the Vedas and developed their own scriptures.

There is inscriptional evidence for the presence of Jain monks in south India by the second or first centuries BC, and archaeological evidence of Jain monks in Saurashtra in Gujarat by the second century CE. Statues of Jain Tirthankara have been found dating back to second century BC.

Political history

Information regarding the political history of Jainism is uncertain and fragmentary. Jains consider the king Bimbisara (c. 558–491 BCE), Ajatashatru (c. 492–460 BCE), and Udayin (c. 460-440 BCE) of the Haryanka dynasty as a patron of Jainism.

Jain tradition states that Chandragupta Maurya (322–298 BCE), the founder of Mauryan Empire and grandfather of Ashoka, became a monk and disciple of Jain ascetic Bhadrabahu during later part of his life. According to historians, Chandragupta story appears in various versions in Buddhist, Jain and Hindu texts. Broadly, Chandragupta was born in a humble family, abandoned, raised as a son by another family, then with the training and counsel of Chanakya of Arthashastra fame ultimately built one of the largest empires in ancient India. According to Jain history, late in his life, Chandragupta renounced the empire he built and handed over his power to his son, became a Jaina monk, and headed to meditate and pursue spirituality in the Deccan region, under the Jaina teacher Bhadrabahu at Shravanabelagola. There state Jain texts, he died by fasting, a Jaina ascetic method of ending one's life by choice (Sallenkana vrata). The 3rd century BCE emperor Ashoka, in his pillar edicts, mentions several ancient Indian religious groups including the Niganthas (Jaina).

According to another Jain legend, king Salivahana of late 1st century CE was a patron of Jainism, as were many others in the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE. But, states von Glasenapp, the historicity of these stories are difficult to establish. Archeological evidence suggests that Mathura was an important Jain centre between 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE. Inscriptions from the 1st and 2nd century CE shows that the schism of Digambara and Svetambara had already happened.

King Harshavardhana of 7th century, grew up in Shaivism following family, but he championed Jainism, Buddhism and all traditions of Hinduism. King Ama of 8th-century converted to Jainism, and Jaina pilgrimage tradition was well established in his era. Mularaja, the founder of Chalukya dynasty constructed a Jain temple, even though he was not a Jain.

In the second half of the 1st century CE, Hindu kings sponsored and helped build major Jaina caves temples. For example, the Hindu Rashtrakuta dynasty started the early group of Jain temples, and Yadava dynasty built many of the middle and later Jain group of temples at the Ellora Caves between 700 and 1000 CE.

Interaction with other religions

Beyond the times of the Mahavira and the Buddha, the two ascetic sramana religions competed for followers, as well merchant trade networks that sustained them. Their mutual interaction, along with those of Hindu traditions have been significant, and in some cases the titles of the Buddhist and Jaina texts are same or similar but present different doctrines.

Royal patronage has been a key factor in the growth as well as decline of Jainism. The Pallava king Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) converted from Jainism to Shaivism under the influence of Appar. His work Mattavilasa Prahasana ridicules certain Shaiva sects and the Buddhists and also expresses contempt towards Jain ascetics. Sambandar converted the contemporary Pandya king to Shaivism. During the 11th century, Basava, a minister to the Jain king Bijjala, succeeded in converting numerous Jains to the Lingayat Shaivite sect. The Lingayats destroyed various temples belonging to Jains and adapted them to their use. The Hoysala king Vishnuvardhana (c. 1108–1152 CE) became a follower of the Vaishnava sect under the influence of Ramanuja, after which Vaishnavism grew rapidly in what is now Karnataka.

Jainism and Hinduism influenced each other. Jain texts declare some of the Hindu gods as blood relatives of legendary Tirthankaras. Neminatha, the 22nd Tirthankara for example is presented as a cousin of Krishna in Jain Puranas and other texts. However, Jain scholars such as Haribhadra also wrote satires against Hindu gods, mocking them with novel outrageous stories where the gods misbehave and act unethically. The Hindu gods are presented by some Jain writers as persecuting or tempting or afraid of or serving a legendary Jina before he gains omniscience. In other stories, one or more Jinas easily defeat the Hindu deities such as Vishnu, or Rama and Sita come to pay respect to a Jina at a major Jain pilgrimage site such as Mount Satrunjaya.

According to a Shaivite legend, an alleged massacre of 8,000 Jain monks happened in the 7th-century which is claimed for the first time in an 11th-century Tamil language text of Nambiyandar Nambi on Sampantar. This event is considered doubtful because it is not mentioned in texts of Campantar, nor any other Hindu or Jain texts for four centuries. K. A. Nilakanta Sastri states that the story is "little more than an unpleasant legend and cannot be treated as history". Lingayatism, a tradition championed by Basava, is attributed to have converted numerous Jains to their new movement and destroyed various Jain temples in north Karnataka.

The Jain and Hindu communities have often been very close and mutually accepting. Some Hindu temples have included a Jain Tirthankara within its premises in a place of honor. Similarly numerous temple complexes feature both Hindu and Jain monuments, with Badami cave temples and Khajuraho among some of the most well known.

Jainism faced persecution during and after the Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent. Muslims rulers, such as Mahmud Ghazni (1001), Mohammad Ghori (1175) and Ala-ud-din Muhammed Shah Khilji (1298) further oppressed the Jain community. They vandalised idols and destroyed temples or converted them into mosques. They also burned Jain books and killed Jains. There were significant exceptions, such as Emperor Akbar (1542–1605) whose legendary religious tolerance, out of respect for Jains, ordered release of caged birds and banned killing of animals on the Jain festival of Paryusan. After Akbar, Jains faced an intense period of Muslim persecution in the 17th-century.

The Jain community were the traditional bankers and financiers, and this significantly impacted the Muslim rulers. However, they rarely were a part of the political power during the Islamic rule period of the Indian subcontinent.

Colonial era

The British colonial government in India, as well as Indian princely states, passed laws that made monks roaming naked in streets a crime, one that led to arrest. This law particularly impacted the Digambara tradition monks. The Akhil Bharatiya Jaina Samaj opposed this law, and argued that it interfered with the religious rights of Jains. Acharya Shantisagar entered Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1927, but was forced to cover his body. He then led a India-wide tour as the naked monk with his followers, to various Digambara sacred sites, and he was welcomed by kings of the Maharashtra provinces. Shantisagar fasted to oppose the restrictions imposed on Digambara monks by British Raj and prompted their discontinuance. The colonial era laws that banned naked monks remained effective through the World War II, and they were abolished by independent India after it gained independence.

Jainism in the modern era

Main article: Jain communityFollowers of the path practised by the Jinas are known as Jains. The majority of Jains currently reside in India. With four to five million followers worldwide, Jainism is relatively small compared to major world religions. Jains form 0.37% of India's population. Most of them are concentrated in the states of Maharashtra (31.46% of Indian Jains), Rajasthan (13.97%), Gujarat (13.02%) and Madhya Pradesh (12.74%). Karnataka (9.89%), Uttar Pradesh (4.79%), Delhi (3.73%) and Tamil Nadu (2.01%) also have significant Jain populations. Outside India, large Jain communities can be found in Europe and the United States. Smaller Jain communities also exist in Canada and Kenya.

Jains developed a system of philosophy and ethics that had a great impact on Indian culture. They have contributed to the culture and language in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra.

Jains encourage their monastics to do research and obtain higher education. Monks and nuns, particularly in Rajasthan, have published numerous research monographs. According to the 2001 Indian census (the last time this information was gathered), Jains have the highest degree of literacy of any religious community in India (94.1 percent), above the national average of 64.8 percent. The gap between male and female literacy is the lowest among Jains at 6.8% compared to the national average of 21% and work participation among men is also the highest at 55.2%.

Major Jain Communities :

- Jain Bunt are a Jain community from Karnataka, India. It is believed that the Jain Bunts also have the highest per capita income in India. This community has erected many monolithic statue of Bahubali namely, Karkala, Dharmasthala and Venur and the famous Saavira Kambada Basadi was also built by this community.

- Saraks is a community in Jharkhand, Bihar, Bengal, and Orissa. They have been followers of Jainism since ancient time. The ancient temples of Purulia were built by this community.

- Porwal community that originated in southern Rajasthan, India. Ancient inscriptions written in Sanskrit refer to the community as Pragvata. They originated from a region east of ancient Shrimal. Porwal community built many famous temples like Ranakpur Jain temple, Luna Vasahi, Adinath temple at Shatrunjaya, Shankheshwar Jain Temple, Girnar Jain temples. Both Svetambara and Digambar are part of this community.

- Parwar is a major Jain community from the Bundelkhand region, which is largely in Madhya Pradesh and Lalitpur District, Jhansi. Tarana Swami, the founder of Taran Panth was also from Parwar community. Many famous tirtha Aharji, Chanderi, Deogarh were built by this community.

- Agrawal Jain originated from Hisar, Haryana, are among the most prominent Jain communities. Shah Jahan invited several Agrawal Jain merchants to delhi. The famous Lal Mandir was built by this community.

- Sarawagi or Khandelwali originated from Khandela, a historical town in northern Rajasthan. The famous temple Soniji Ki Nasiyan was built by this community.

- Bagherwal originated from Baghera (currently known as Ajmer district) a princely state in Rajasthan, a community of Digambar sect. The community has built Jain temples in Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra. The famous seven story Kirti Stambh in Chittor Fort by this community in twelfth century AD.

- Shrimal, originally from Rajasthan, Shrimal town in southern Rajasthan, were traditionally wealthy merchants. Shrimal claims to be descend from the Goddess Lakshmi. The Shrimal (Srimal) Jain are thought to be the highest gotra in the Oswal merchant and minister caste that is found primarily in the north of India.

- Oswal are a Jain community with origins in the Marwar region of Rajasthan and Tharparkar district in Sindh.

- Jaiswal are mainly located in the Gwalior and Agra region.

- Navnat emerged as a result of blending of several smaller Jain communities in East Africa as well as in Gujarat itself in early 20th century.

Art and architecture

Main article: Jain art-

Hathigumpha inscription of King Khāravela at Udayagiri Caves, 2nd Century BCE

Hathigumpha inscription of King Khāravela at Udayagiri Caves, 2nd Century BCE

-

Paintings at the Sittanavasal Cave, 7th century, Pudukottai, Tamil Nadu

Paintings at the Sittanavasal Cave, 7th century, Pudukottai, Tamil Nadu

-

Symbolic & Historical Artwork in Gori Temple of Nagarparkar, Pakistan

-

Ayagapatta, Jain Tablet of homage excavated from Kankali Tila, c. 1st Century CE

Ayagapatta, Jain Tablet of homage excavated from Kankali Tila, c. 1st Century CE

-

Painting of Tirth Pat

-

Depiction of Samavasarana

Depiction of Samavasarana

Jainism has contributed significantly to Indian art and architecture. Jains mainly depict tirthankara or other important people in a seated or standing meditative posture. Yakshas and yakshinis, attendant spirits who guard the tirthankara, are usually shown with them. Figures on various seals from the Indus Valley Civilisation bear similarity to Jain images, nude and in a meditative posture. The earliest known Jain image is in the Patna museum. It is dated approximately to the 3rd century BCE. Bronze images of Pārśva can be seen in the Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai, and in the Patna museum; these are dated to the 2nd century BCE.

Ayagapata is a type of votive slab associated with worship in Jainism. Numerous such stone tablets discovered during excavations at ancient Jain sites like Kankali Tila near Mathura in India. Some of them date back to 1st century C.E. These slabs are decorated with objects and designs central to Jain worship such as the stupa, dharmacakra and triratna. A large number of ayagapata (tablet of homage), votive tablets for offerings and the worship of tirthankara, were found at Mathura.

Samavasarana is an important theme of Jain art.

The Jain tower in Chittor, Rajasthan, is a good example of Jain architecture. Decorated manuscripts are preserved in Jain libraries, containing diagrams from Jain cosmology. Most of the paintings and illustrations depict historical events, known as Panch Kalyanaka, from the life of the tirthankara. Rishabha, the first tirthankara, is usually depicted in either the lotus position or kayotsarga, the standing position. He is distinguished from other tirthankara by the long locks of hair falling to his shoulders. Bull images also appear in his sculptures. In paintings, incidents from his life, like his marriage and Indra's marking his forehead, are depicted. Other paintings show him presenting a pottery bowl to his followers; he is also seen painting a house, weaving, and being visited by his mother Marudevi. Each of the twenty-four tirthankara is associated with distinctive emblems, which are listed in such texts as Tiloyapannati, Kahavaali and Pravacanasaarodhara.

There are 26 caves, 200 stone beds, 60 inscriptions, and over 100 sculptures in and around Madurai. This is also the site where Jain ascetics wrote great epics and books on grammar in Tamil.

Temples

Main article: Jain temple-

Palitana temples, Shatrunjaya

Palitana temples, Shatrunjaya

-

Ranakpur Jain Temple

Ranakpur Jain Temple

-

Saavira Kambada Basadi

-

Hutheesing Jain Temple

Hutheesing Jain Temple

-

Girnar Jain temples

Girnar Jain temples

-

Jal Mandir, Pawapuri

Jal Mandir, Pawapuri

-

Jain Narayana temple

Jain Narayana temple

-

Parshvanath Temple in Khajuraho

Parshvanath Temple in Khajuraho

-

Lodhruva Jain temple

Lodhruva Jain temple

-

Jain temple, Antwerp, Belgium

Jain temple, Antwerp, Belgium

-

Indra Sabha, Ellora Caves

Indra Sabha, Ellora Caves

-

Brahma Jinalaya, Lakkundi

Brahma Jinalaya, Lakkundi

A Jain temple, Derasar or Basadi is a place of worship for Jains. Jain temples are built with various architectural designs, but there are mainly two type of Jain temples: Shikar-bandhi Jain temple (one with a dome), and Ghar Jain temple (Jain house temple – one without a dome).

There is always a main deity also known as moolnayak in every Jain temple placed inside a sanctum called "Gambhara" (Garbha Graha). A manastambha (column of honor) is a pillar that is often constructed in front of Jain temples.

Remnants of ancient Jain temples and cave temples can be found around India and Pakistan. Notable among these are the Jain caves at the Udaigiri Hills near Bhelsa (Vidisha) in Madhya Pradesh, the Ellora in Maharashtra, the Palitana temples in Gujarat, and the Jain temples at Dilwara Temples near Mount Abu, Rajasthan. Chaumukha temple in Ranakpur is considered one of the most beautiful Jain temple and famous for detailed carvings. Shikharji is believed to be the place where twenty of the twenty-four Jain Tīrthaṅkaras along with many other monks attained moksha, according to Nirvana Kanda and other texts. The Palitana temples are the holiest shrine for the Svetambara Murtipujaka sect. Along with Shikharji the two sites are considered the holiest of all pilgrimage sites by the Jain community.

The Jain complex, Khajuraho and Jain Narayana temple are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Shravanabelagola, Saavira Kambada Basadi or 1000 pillars and Brahma Jinalaya are important Jain centers in Karnataka.

The Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves dating back to the 2nd–1st century BCE are dedicated to Jainism. They are rich with carvings of Jain tirthanakars and deities with inscriptions including the Hathigumpha inscription ("Elephant Cave" inscription). Jain cave temples at Badami, Mangi-Tungi and the Ellora Caves are considered important.

The Sittanavasal Cave temple is regarded as one of the finest examples of Jain art. It is the oldest and most famous Jain centre in the region. It possesses both an early Jain cave shelter, and a medieval rock-cut temple with excellent fresco paintings comparable to Ajantha paintings; the steep hill contains an isolated but spacious cavern. Locally, this cavern is known as "Eladipattam", a name that is derived from the seven holes cut into the rock that serve as steps leading to the shelter. Within the cave there are seventeen stone beds aligned in rows; each of these has a raised portion that could have served as a pillow-loft. The largest stone bed has a distinct Tamil-Brahmi inscription assignable to the 2nd century BCE, and some inscriptions belonging to the 8th century BCE are also found on the nearby beds. The Sittannavasal cavern continued to be the "Holy Sramana Abode" until the 7th and 8th centuries. Inscriptions over the remaining stone beds name mendicants such as Tol kunrattu Kadavulan, Tirunilan, Tiruppuranan, Tittaicharanan, Sri Purrnacandran, Thiruchatthan, Ilangowthaman, Sri Ulagathithan, and Nityakaran Pattakali as monks.

The 8th century Kazhugumalai temple marks the revival of Jainism in South India.

In Pakistan, the Cultural Landscape of Nagarparkar, located at the southern limit of the vast Thar desert was an important centre of Jain religion and culture for centuries. The Karunjhar hills were a place of pilgrimage called Sardhara where there is a Jain temple of Mahadeve and a ritual pool. The towns of Nagarparker, Gori, Viravah, Bodhesar, contain remains of numerous Jain temples dating from the 12th to 15th centuries which appear to be the high point of Jain culture. The Temple at Gori is an excellent example of classical Jain style, with one main temple surrounded by 52 smaller shrines, each housing one or more images of Jain tirthankar. Other significant Jain temples and remains of religious institutional buildings and water tanks are found in the villages of Nagarparkar, including the outstanding “bazaar” temple, Bodhesar, Viaravah, Kasbo and Gori.

Statues and sculptures

Main article: Jain sculptureJain sculptures are mainly images depicting Tīrthaṅkaras. A sculpture could depict any of the twenty-four Tīrthaṅkaras images depicting Parshvanatha, Rishabhanatha or Mahāvīra being more popular. These Tīrthaṅkaras usually depicted in the in the lotus position or kayotsarga. Sculptures of chaumukha ("quadruple") images are also popular Jainism. Sculptures of Arihant, Bahubali, and protector deities like Ambika are also found. Tirthanakar idols look similar and are differentiated on the basis of the symbol belonging to each tirthanakar except Parshvanatha. Statues of Parshvanath have a snake crown on head. There are a few differences between the Digambara and the Svetambara depictions of idols. Digambara images are naked without any beautification, whereas Svetambara depictions are clothed and decorated with temporary ornaments.

A monolithic, 18-metre (59-foot) statue of Bahubali, referred to as Gommateshvara, built in 981 AD by the Ganga minister and commander Chavundaraya, is situated on a hilltop in Shravanabelagola in the Hassan district of Karnataka state. This statue was voted as the first in the SMS poll Seven Wonders of India conducted by The Times of India. The Statue of Ahimsa (depicting Rishabhanatha) was erected in the Nashik district in 2015 which is 33 m (108 ft) tall. Idols made from Ashtadhatu (literally "eight metals"), Akota Bronze, brass, gold, silver, stone monoliths, rock cut, and precious stones are popular in Jainism.

A large number of ayagapata, votive tablets for offerings and the worship of tīrthankara, were excavated from Kankali Tila, Mathura. These sculptures date from the 2nd century BCE to the 12th century CE.

-

Tirthankara Parshvanatha, Victoria and Albert Museum, 6th-7th Century

-

Tirthankara Suparshvanatha, 14th century, marble

Tirthankara Suparshvanatha, 14th century, marble

-

'Digambara Yaksha Sarvahna', c. 900, Norton Simon Museum

-

Parshavanth idol made up of Akota Bronze, 7th-century

-

Ashtadhatu Mahaveer Bhagwan idol at Shantinath Jain Teerth

Ashtadhatu Mahaveer Bhagwan idol at Shantinath Jain Teerth

-

Idol of Rishabhanatha with 23 tirthankars made up of brass inlaid with silver

Idol of Rishabhanatha with 23 tirthankars made up of brass inlaid with silver

- Monoliths

-

Gommateshwara statue (10th century) at Shravanabelagola, created by Chavundaraya

Gommateshwara statue (10th century) at Shravanabelagola, created by Chavundaraya

- Statue of Ahimsa (completed in 2016), Mangi-Tungi, Maharashtra, created by Gyanmati Mataji Statue of Ahimsa (completed in 2016), Mangi-Tungi, Maharashtra, created by Gyanmati Mataji

- Megalithic statue of Rishabhanatha at Bawangaja, 12th century Megalithic statue of Rishabhanatha at Bawangaja, 12th century

-

Rishabhanatha statue at Gopachal Hill, Gwalior Fort, 15th century

Rishabhanatha statue at Gopachal Hill, Gwalior Fort, 15th century

-

Neminatha Statue, Tirumalai

Neminatha Statue, Tirumalai

Symbols

Main article: Jain symbols

Swastika

The swastika is an important Jain symbol. Its four arms symbolise the four states of existence according to Jainism:

Symbol of Ahimsa

The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes ahismā in Jainism with ahiṃsā written in the middle. The wheel represents the dharmachakra, which stands for the resolve to halt the saṃsāra through the relentless pursuit of ahimsā.

Jain emblem

In 1974, on the 2500th anniversary of the nirvana of Mahavira, the Jain community chose one image as an emblem to be the main identifying symbol for Jainism. It consists of three Loks (realms) of Jain cosmology i.e., heaven, material world and hell. The semi-circular topmost portion symbolizes Siddhashila, which is a zone beyond the three realms. The three dots on the top under the semi-circle symbolize the ratnatraya – right belief, right knowledge, and right conduct. The swastika is present in the top portion and the symbol of Ahimsa in the lower portion.

The meaning of the mantra at the bottom, Parasparopagraho Jivanam, is "All life is bound together by mutual support and interdependence."

Jain flag

The five colours of the Jain flag represent the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi and the five vows, small as well as great:

- White – represents the arihants, souls who have conquered all passions (anger, attachments, aversion) and have attained omniscience and eternal bliss through self-realization. It also denotes peace or ahimsa ("non-violence ").

- Red – represents the Siddha, souls that have attained salvation and truth. It also denotes satya ("truthfulness")

- Yellow – represents the acharya the Masters of Adepts. The colour also stands for achaurva ("non-stealing").

- Green – represents the upadhyaya ("adepts"), those who teach scriptures to monks. It also signifies brahmacharya ("chastity").

- Black – represents the Jain ascetics. It also signifies aparigraha ("non-possession").

Om

In Jainism, Om is considered a condensed form of reference to the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi, by their initials A+A+A+U+M (o3m). According to Dravyasamgraha by Acharya Nemicandra, AAAUM (or just Om) is one syllable short form of the initials of the five parameshthis: "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni". The Om symbol is also used in ancient Jain scriptures to represent the five lines of the Namokar Mantra.

Ashtamangala

The Ashtamangala are a set of eight auspicious symbols, which are different in the Digambara and Śvētāmbara traditions.

In the Digambara tradition, the eight symbols are:

In the Śvētāmbara tradition, the eight symbols are:

- Swastika

- Srivatsa

- Nandavarta

- Vardhmanaka ("food vessel")

- Bhadrasana ("seat")

- Kalasha ("pot")

- Darpan ("mirror")

- Pair of fish

Reception

Jainism is both criticised and praised for some of its practices and beliefs. Mahatma Gandhi was greatly influenced by Jainism. He said:

No religion in the World has explained the principle of Ahimsa so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of Ahimsa or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond. Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Mahāvīra is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on Ahimsa.

Swami Vivekananda appreciated the role of Jainism in the development of Indian religious philosophy. In his words, he asks: