This is an old revision of this page, as edited by 80.67.172.1 (talk) at 07:02, 5 December 2004 (Revert aol anon ip evading block). The present address (URL) is a permanent link to this revision, which may differ significantly from the current revision.

Revision as of 07:02, 5 December 2004 by 80.67.172.1 (talk) (Revert aol anon ip evading block)(diff) ← Previous revision | Latest revision (diff) | Newer revision → (diff)This article deals with the mainstream modern usage of the word libertarianism. For the use of the term "libertarianism" in the philosophy of free will see libertarianism (philosophy). For a similar term that was used in Europe please see libertarian socalism

"Libertarian" and "libertarianism" are also used to refer to liberty in a general way. For example, someone arguing for civil liberties may be known as a "civil libertarian", regardless of their exact political allegiances.

Libertarianism is a political philosophy which advocates individual rights and a limited government. In common with many other modern political ideologies, Libertarians believe that individuals should be free to do anything they want, so long as they do not infringe upon the rights of others. Libertarians typically emphasise civil rights (such as the right to a fair trial or political participation, sometimes thought of as negative rights) over social rights (the right to a free education or employment, sometimes thought of as positive rights).

Terminology

The term "libertarianism" in the above sense has been in widespread use only since the 1950s. libertaire had previously been used most commonly by anarchists to describe themselves, avoiding the derogatory connotations of the word "anarchy". In the aftermath of the crushing of the Paris Commune in 1871, anarchism and anarchists were officially outlawed in many countries for decades, so anarchists often called their groups and publications by another name — hence the adoption of the libertaire as an alternative term in French.

The term became popular in the United States in the middle of the 20th century, with thinkers who saw themselves as continuing the classical liberal tradition of the Enlightenment. By that time the term liberalism had come to refer within the United States to belief in government regulation of the economy and government redistribution of wealth. These classical liberal thinkers therefore came to call themselves libertarians; and from the United States the term has spread to the rest of the world.

However, the traditional use of the term libertarie continues in Europe, where the French word libertaire, the Spanish word libertario, etc.

Libertarianism and classical liberalism

As noted in the previous section, libertarians see their origins in the earlier 17th to 20th century tradition of classical liberalism, and often use that term as a synonym for libertarianism, particularly outside of the USA.

Some, particularly in the USA, argue that while libertarianism has much in common with the earlier tradition of classical liberalism, the latter term should be reserved for historical thinkers for the sake of clarity and accuracy. Others make the distinction to distance themselves from the socialist and welfare state connotations of the word "liberal" in American English. Critics of the trend toward conflation assert that there is a patterned difference between many libertarian and classical liberal thinkers as far as their beliefs about the degree to which the state should be restricted. These critics argue that a more accurate term to describe libertarianism would be neo-classical liberalism.

Other critics argue that there are differences between classical liberal thinkers and libertarianism. Many modern libertarians view the very wealthy as having earned their place, while, according to these critics, the classical liberals were often skeptical of the rich, businessmen, and corporations seeing them as aristocrats with desires to tyrranize the people. Perhaps the most important classical liberal of this strain was Thomas Jefferson who was critical of the growth of corporations. Jefferson, along with some 19th and 20th century libertarians (and even some modern day Libertarians - see geolibertarian), also argued at times for a relatively loose concept of the right to property in land.

In any case, whether one equates them or not, libertarianism closely models opinions, methods, and approaches of earlier classical liberalism and many libertarians see themselves as the inheritors of that tradition. Advocacy of free trade, limited government, an isolationist, non-interventionist, foreign policy and individual liberty are common themes of both libertarianism and classical liberalism. Hayek and other libertarian scholars state that libertarianism today has few commonalities with modern "new" or "welfare" liberalism or socialism. Many economically-oriented libertarians use the word "socialist" nigh-interchangeably with "statist" in critiquing their opponents, even rightist opponents, out of the argument that socialism is the only consistent (family of) statist ideologies. This may perhaps be compared with Marxist use of terms such as "capitalist" and "bourgeois" in critique of other (self-proclaimed) leftists (see state capitalism).

Libertarianism in the political spectrum

In the US some libertarians feel conservative and some conservatives feel libertarian, because both groups claim as theirs the ideology of the founding fathers of the USA. Still, it is possible to distinguish quite neatly two different and often opposite traditions, and it is only a matter of terminology when confusion occurs. This opposition is clearly explained in Friedrich Hayek's article "Why I Am Not a Conservative" . Although it should be noted that Hayek was referring to European authoritarian Conservatism, which was suspicious of capitalism due to the belief that it undermined the power of the state.

There have been times when those with libertarian views were considered left-wing on the political spectrum (for instance, in the seventeenth century, the Whigs were revolutionaries, and in 1848, Frederic Bastiat was seating rather on the left side of the Assembly). It can be argued that while the balance of political opinions has shifted a lot, the anti-statist tradition of libertarianism has not moved, only evolved and grown.

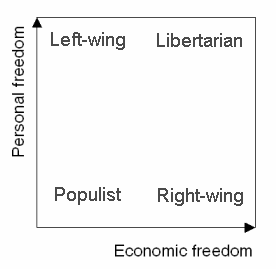

Libertarians do not identify themselves as either "right-wing" or "left-wing". Indeed, many reject the one-dimensional left/right political spectrum and instead propose a two-dimensional space with "personal freedom" on one Cartesian axis and "economic freedom" on the other. This space is shown by the Nolan Chart, proposed by David Nolan, the founder of the United States Libertarian Party. Though many libertarians may believe the separation of personal and economic freedom is actually a false dichotomy, the Nolan Chart is frequently utilized in order to differentiate their ideology from others (e.g., conservativism and modern liberalism) which generally advocate greater limitations on different modes of freedom according to their respective conceptions of rights. The libertarian conception of rights maximizes individual liberty and autonomy, which leads libertarians to advocate the fewest possible limitations on either mode of freedom.

The validity of the Nolan Chart is disputed by many non-libertarians. Socialists, modern liberals and conservatives often argue that the libertarian definition of "freedom" is flawed or incorrect.

For more information, see main article: Nolan chart

Individualism, liberty, responsibility and property

The fundamental values that libertarians claim to fight for are individual liberty, individual responsibility and individual property. Libertarians have an elaborate theory of these values that they defend, that does not always match prevailing views regarding liberty, and that strictly opposes collectivist views in this regard. As an example, many libertarians hold that personal liberties (such as privacy and freedom of speech) are inseparable from economic liberties (such as the freedom to trade, labor, or invest). They make this point to contrast themselves with collectivist socialists who believe that economic regulation is necessary for personal freedom and personal well-being, and with conservatives who tie free trade with a restrictive regulation of personal issues such as sexuality, drug use and speech.

Many criticisms of libertarianism revolve around the notion of "freedom" itself. For example, socialists would argue that the economic freedoms defended by libertarians result in privileges for the wealthy elite and violations of workers' rights.

Other criticisms revolve around the desirability and practical usefulness of certain freedoms. Conservatives, in particular, would argue that excessive personal freedoms encourage dangerous and irresponsible behaviour, or that they are too permissive on crime.

It is a chief point for many libertarians that rights vest originally in individuals and never in groups such as nations, races, religions, classes, or cultures. This conception holds it as nonsensical to say (for instance) that a wrong can be done to a class or a race in the absence of specific wrongs done to individual members of that group. It also undercuts rhetorical expressions such as, "The government has the right to ...", since under this formulation "the government" has no original rights but only those duties with which it has been lawfully entrusted under the citizens' rights. Libertarianism frequently dovetails neatly therefore with strict constructionism in the constitutional sense.

The classic problem in political philosophy of the legitimacy of property is essential to libertarians. Libertarians often justify individual property on the basis of self-ownership: one's right to own one's body; the results of one's own work; what one obtains from the voluntary concession of a former legitimate owner through trade, gift or inheritance, and so forth. Ownership of disputed natural resources is more problematic and solutions such as homesteading have been studied from John Locke to Murray Rothbard. This is particularly important since most criticisms of private property rest on the notion that no person can claim rightful ownership over natural resources, and that since the making of any object requires some amount of raw materials and natural resources, no person can claim rightful ownership over man-made objects either.

Anti-statist doctrine

Libertarians consider that there is an extended domain of individual freedom defined by every individual's person and private property, and that no one, whether private citizen or government, may under any circumstances violate this boundary. Indeed, libertarians consider that no organization, including government, can have any right except those that are voluntarily delegated to it by its members -- which implies that these members must have had these rights to delegate them to begin with.

Thus, according to libertarians, taxation and regulation are at best necessary evils, and where unnecessary are simply evil. Government spending and regulations should be reduced insofar as they replace voluntary private spending with involuntary public spending, and replace private morality with public coercion. To many libertarians, governments should not establish schools, run hospitals, regulate industry, commerce or agriculture, or run social welfare programs. Nor should government restrict sexual practices, gambling, drug usage, or any other 'victimless' crimes. Libertarians also believe in an extremely broad (and in some cases all-inclusive) interpretation of free speech which should not be restricted by government. For libertarians, government's main imperative should be Laissez-faire -- "Hands off!" -- except to protect the individual rights recognized by libertarianism.

Libertarians believe in minimizing the responsibilities of citizens towards the government, which directly results in minimizing the responsibilities of the government towards its citizens.

See Albert Jay Nock's Our Enemy the State for early modern anti-state thought and Lysander Spooner's The Constitution of No Authority for a critique of social contract theory.

Anarchists and minarchists

All libertarians agree that government should be limited to what is strictly necessary, no more, no less. But there is no consensus among them about how much government is necessary. Hence, libertarians are further divided between the minarchists and the anarcho-capitalists, which are discussed at length in specific articles. Both minarchists and anarcho-capitalists differ in their beliefs from the anarcho-syndicalists, anarcho-socialists and libertarian socialists, who are usually considered not to be libertarians at all (the feeling is mutual; anarcho-socialists and libertarian socialists claim that capitalism is incompatible with freedom, and thus libertarian/anarcho-capitalists cannot be considered libertarians at all).

The minarchists believe that a "minimal" or a "night-watchman" state is necessary to guarantee property rights and civil liberties, and is to be used for that purpose only. For them, the proper functions of government might include the maintenance of the courts, the police, the military, and perhaps a few other vital functions (e.g., roads). While they are technically statists since they support the existence of a government, they would resent the connotations usually attached to this term.

The anarcho-capitalists, believe that even in matters of justice and protection and particularly in such matters, action by competing private responsible individuals (freely organized in businesses, cooperatives, or organizations of their choice) is much better than action by governments. While they consider themselves to be anarchists, they insist in rejecting the connotations often attached to this term regarding support of a socialist ideal.

Minarchists consider that they are realists, while anarcho-capitalists are utopian to believe that governments can be wholly done without. Anarcho-capitalists consider that they are realists, and that minarchists are utopian to believe that a state monopoly of violence can be contained within any reasonable limits. Critics of both these positions generally point to the historical record of democratic governments as evidence that democracy and popular rule have succeeded not only in containing government abuse of freedom, but have in fact transformed the state from a violent master of the people into their loyal and peaceful servant.

The minarchist/anarcho-capitalist division is very friendly, and not the source of any deep enmity, despite the sometimes involved theoretic arguments. Libertarians feel much more strongly about their common defense of individual liberty, responsibility and property, than about their possible minarchist vs. anarchist differences. Since both minarchists and anarchists believe that existing governments are far, far too intrusive, the two factions seek change in almost exactly the same directions.

Many libertarians don't take a position with regard to this division, and don't care about it. Indeed, many libertarians consider that governments exist and will exist in the foreseeable future, up to the end of their lives, so that their efforts are better spent fighting, containing and avoiding the action of governments than trying to figure out what life could or couldn't be like without them. In recent years libertarianism has attracted many "fellow-travelers" (to borrow a phrase from the Communists) who care little about such theoretical issues and merely wish to reduce the size, corruption, and intrusiveness of government.

Some libertarian philosophers argue that, properly understood, minarchism and anarcho-capitalism are not in contradiction. See Revisiting Anarchism and Government by Tibor R. Machan.

Utilitarianism, natural law, and reason

Libertarians tend to take either one of an axiomatic natural law point of view, or a utilitarian point of view, in justifying their beliefs. Some of them (like Frederic Bastiat), claim a natural harmony between these two points of view (that would indeed be but different points of view on a same truth), and consider it irrelevant to try to establish one as truer.

An exposition of utilitarian libertarianism appears in David Friedman's book The Machinery of Freedom, which includes a chapter describing an allegedly highly libertarian culture that existed in Iceland around 800 AD.

For natural rights libertarianism, see for instance Robert Nozick, Murray Rothbard, and Hans-Hermann Hoppe.

See also relevant paragraphs about this difference in points of view in the article about Anarcho-capitalism.

An alternate justification for libertarian ideas (broadly speaking), predicated on the use of reason and the observance of a certain code of ethics (rather than pursuit of social ends) is contained within the philosophy of Objectivism established by Ayn Rand. It should be noted that although Objectivism and libertarianism overlap, Rand did not consider herself a libertarian.

Some libertarians do not attempt to justify their beliefs in any external sense; they support libertarianism because they desire the maximum degree of liberty possible within their own lives, and see libertarianism as the most effective political philosophy towards this end.

Controversies among libertarians

Libertarians do not agree on every topic. Although they share a common tradition of thinkers from centuries past to contemporary times, no thinker is considered a common authority whose opinions are to be blindly accepted. Rather, they are generally considered a reference to compare one's opinions and arguments with.

These controversies are addressed in separate articles:

- Libertarian perspectives on intellectual property

- Libertarian perspectives on immigration

- Libertarian perspectives on abortion

- Libertarian perspectives on the death penalty

- Libertarian perspectives on natural resources

- Libertarian perspectives on interventionism

A typographical convention

Note that some writers follow the convention of using libertarian (spelled in lowercase) to mean a general advocate of libertarianism, while Libertarian (capitalized) refers specifically to a member of a libertarian political party.

Quotations

"Libertarianism is a philosophy. The basic premise of libertarianism is that each individual should be free to do as he or she pleases so long as he or she does not harm others. In the libertarian view, societies and governments infringe on individual liberties whenever they tax wealth, create penalties for victimless crimes, or otherwise attempt to control or regulate individual conduct which harms or benefits no one except the individual who engages in it."

— Definition written by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service, during the process of granting the Advocates for Self-Government status as a non-profit educational organization.

Modern libertarians

Notable theorists and authors

- Randy Barnett

- Clint Bolick

- James Bovard

- Nathaniel Branden

- Gene Callahan

- David Friedman

- Milton Friedman

- Andrew Galambos

- Friedrich Hayek

- Robert A. Heinlein

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe

- Rose Wilder Lane

- Robert LeFevre

- Ludwig von Mises

- Robert Nozick

- Virginia Postrel

- Ayn Rand

- George Reisman

- Lew Rockwell

- Murray Rothbard

- Thomas Sowell

Politicians and media personalities

- Michael Badnarik

- Art Bell

- Neal Boortz

- Harry Browne

- Larry Elder

- John Hospers

- Russell Means

- Theodora B. Nathan

- David Nolan

- Gary Nolan (radio host)

- P. J. O'Rourke

- Ron Paul

- Justin Raimondo

- L. Neil Smith

- J. Neil Schulman

- John Stossel

- Jesse Ventura

- Eugene Volokh

- Walter Williams

Celebrities

- Dave Barry

- Richard Branson

- Drew Carey

- Clint Eastwood

- Bernhard Goetz

- Penn Jillette

- Denis Leary

- Melanie

- Trey Parker

- Eric S. Raymond

- Kurt Russell

- Tom Selleck

- Wil Wheaton

Libertarian magazines

See also

- See also: liberalism; minarchism; anarcho-capitalism; capitalism; Objectivism; individualist anarchism; libertarian communism; small-l libertarianism; The Free State Project; seasteading; Libertarian theories of law; deregulation; Republican Liberty Caucus, Mass surveillance

- Opposes: mercantilism; statism; conservatism; collectivism; socialism; fabianism; communism; nazism; fascism; Welfare state; planned economy; state interventionism; regulation.

- Related topics: Civil Society; open society; political models; ideology; Liberator Online

- Libertarian blogs:

- Spanish libertarian writer Juan Pina's blog in English

External links

Libertarian links

- Ideas For Liberty Wiki

- The Libertarian Learning Centre

- Australian Libertarian Party (The LDP)

- Australian Libertarian Web Site

- USA Libertarian Party

- Adam Smith Institute

- Cato Institute

- Spanish libertarian writer Juan Pina

- Libertarian.org

- Free-Market.Net

- Reason Foundation publishers of Reason Magazine

- Advocates for Self-Government

- the International Society for Individual Liberty - see their Introduction to the Philosophy of Liberty

- American Liberty Foundation

- Foundation for Economic Education

- Institute for Humane Studies

- Libertarian International

- Libertarian Alliance (UK)

- Laissez Faire Books

- Individual Self-Determination Manifesto (Spanish)

- Bureaucrash Activist Network

- Libertarianpunk.com

- Future of Freedom Foundation

- Mises Institute

- LewRockwell.com

- LibertyForums

- Open Directory links

- Liberté, j’écris ton nom

- Beloved Freedom

- Understanding The Libertarian Philosophy

- The Libertarian Society of Iceland

- Imagine Freedom - A polemic on applied Libertarianism

- Perfiles del siglo XXI (A Libertarian magazine in Spanish

Non-libertarian links

- Critiques Of Libertarianism (includes sub-sections presenting anti-libertarian arguments from different political standpoints, as well as more general arguments)

- Comparison of Libertarians and Anarchists (Humor)