| Revision as of 15:21, 18 July 2004 view sourceFormeruser-81 (talk | contribs)22,309 editsm →References and further reading← Previous edit | Revision as of 19:02, 18 July 2004 view source Sam Spade (talk | contribs)33,916 edits →Hitler's family: - and mistressNext edit → | ||

| Line 224: | Line 224: | ||

| *] sister | *] sister | ||

| *] nephew | *] nephew | ||

| *] niece |

*] niece | ||

| == Related articles == | == Related articles == | ||

Revision as of 19:02, 18 July 2004

| The neutrality of this article is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Adolf Hitler (April 20, 1889 - April 30, 1945) was the dictator of Nazi Germany and leader of the Nazi Party. He is regarded as one of the most significant leaders of world history. Hitler was instrumental in the outbreak of World War II, which resulted in untold destruction and the deaths of an estimated 50 million people. Along with a keen racial awareness, passionate anti-Semitism formed a foundation of his philosophy, enumerated in his chef d'oeuvre Mein Kampf, and ultimately led to the instigation of the Holocaust. At their peak, the German forces controlled the greater part of Europe, but ultimately Hitler was defeated, and committed suicide in the Berlin Führerbunker with the Red Army only a few blocks away.

Childhood and Youth

Adolf Hitler was born on April 20 1889 at Braunau-am-Inn, a small town near Linz in the province of Upper Austria, not far from the German border, in what was then Austria-Hungary.

His father, Alois Hitler (1837-1903), was a minor customs official who had been born illegitimate. Until he was 40, Hitler's father Alois used his mother's surname, Schicklgruber. In 1876, Alois took on his adoptive father's surname, originally spelt 'Hiedler', by having the church declare him the son of that man after his death. Adolf Hitler was accused of rightfully being not a Hitler, but a Schicklgruber by his political enemies.

Hitler's mother, Klara Hitler (maiden name Klara Pölzl), was also his father's second cousin. He brought her into his house to take care of his children while his second wife, who was sick and dying, was being taken care of elsewhere. After his wife's death, Alois married Klara after waiting months for special permission from the Catholic Church, and not a moment too soon as she was already visibly pregnant. Ultimately, she bore him a total of six children. However, only Adolf, who was her second child, and his younger sister Paula survived childhood.

Adolf was an intelligent but moody boy, and he twice failed to pass the high school admission examinations in Linz. There, he became captivated by the anti-Semitic, Pan-German lectures of Professor Leopold Poetsch, who greatly influenced the young man's views.

Hitler was devoted to his indulgent mother and presumably had a hatred for his father, who was a strict disciplinarian. In his book, Mein Kampf, written by Hitler partially as propaganda, Hitler is respectful of his father, though he does state that they had irreconcilable differences over Hitler's firm decision to become an artist. His father firmly opposed such a career path, wanting Adolf to become a civil servant instead.

Vienna and Munich

In January 1903 Alois Hitler died, and in December 1907 his widow Klara died of cancer. Eighteen-year-old Adolf was orphaned and he soon left home for Vienna, where he had vague hopes of becoming an artist. He was entitled to an orphan's pension, and eked this out by working as an illustrator. He had some artistic talent and often drew pictures of houses and grand buildings. He applied to the Vienna school of art twice, but was rejected each time. He lost his pension in 1910, but by then he had inherited some money from an aunt.

It was in Vienna that Hitler began developing into an active anti-Semite, a passion that was to rule his life and was the key to all his subsequent actions. Anti-Semitism was deeply ingrained in the south German Catholic culture in which Hitler was raised. Vienna had a large Jewish community, including many Orthodox Jews from eastern Europe. Hitler later recorded his disgust on encountering Viennese Jews.

In Vienna anti-Semitism had developed from its religious origins into a political doctrine, promoted by publicists such as Lanz von Liebenfels, whose pamphlets Hitler read, and politicians like Karl Lueger, the Mayor of Vienna, or Georg Ritter von Schönerer, who contributed to the racial aspect of anti-Semitism. From them Hitler acquired the belief in the superiority of the "Aryan race" which formed the basis of his political views. Hitler came to believe that the Jews were the natural enemies of the "Aryans," and were also responsible for Germany's economic problems.

After a while the money he had inherited from his aunt ran out, and for the next several years he lived in relative obscurity as a painter. He would paint scenes copied from postcards, then sell his paintings to merchants. He did this simply to make money, he did not consider his paintings as any kind of high art. Contrary to popular myth, he made a good living as a painter, making more money than if he had a regular job as a bank clerk or schoolteacher, and having to work far fewer hours. During his spare time he often attended operas in Vienna's concert halls, especially Norse mythological operas by Richard Wagner. He also spent much time reading.

In 1913 Hitler moved to Munich to avoid military service in the Austro-Hungarian army. His desire to get away from the multiethnic Austro-Hungarian Empire and make his home in the much more 'racially' homogeneous Germany was also a factor. The Austrian army later arrested him and gave him a physical examination. He was found unfit for service and allowed to return to Munich. But in August 1914 when the German Empire entered World War I, he at once enlisted in the Bavarian Army. He saw active service in France and Belgium as a messenger, a very dangerous assignment, as it involved exposing himself to enemy fire instead of staying protected in a trench. Hitler's service record was exemplary, but he was never promoted beyond corporal, for unknown reasons. He was cited for bravery in action, twice. The first honor was being awarded the Iron Cross, Second Class, in December 1914. Then in August, 1918, he was awarded the Iron Cross, First Class, an honor seldom given to corporals.

During the war Hitler acquired a passionate German patriotism, despite not being a German citizen (a detail he did not rectify until 1932). He was shocked at the German capitulation in November 1918, when the German army was (so he believed) undefeated. He, like many other German nationalists, blamed civilian politicians (the "November criminals") for the surrender.

The Nazi Party

After the war Hitler stayed in the army, which was now mainly engaged in suppressing the socialist uprisings which were breaking out across Germany—including in Munich, where Hitler returned in 1919. Hitler took part in "national thinking" courses organized by the Education and Propaganda Department (Dept Ib/P) of the Bavarian Reichswehr Group, Headquarters 4 under Captain Mayr. One key purpose of this group was to create a scapegoat for the outbreak of the World War and for Germany's defeat. This scapegoat was found in "international Jewry", in communists, and in politicians across the party spectrum.

For Hitler, who had experienced the horrors of war firsthand, the question of guilt was essential. Already influenced by anti-Semitic ideas, he eagerly believed in Jewish responsibility and soon became an efficient multiplicator for the propaganda conceived by Mayr and his superiors. In July 1919 Hitler, because of his intelligence and oratory skills, was appointed a V-Mann of an "Enlightenment Commando" for the purpose of influencing other soldiers with the same ideas.

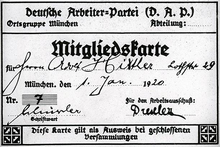

He was then assigned by Headquarters to infiltrate a small nationalist party, the German Workers' Party. Hitler joined the party as member number 555 (numbering began at 500 to make the party seem larger than it actually was) in September 1919. Here he also met Dietrich Eckart, an anti-Semite and one of the early key members of the party.

In the same month, Hitler wrote what is often deemed his first anti-Semitic text, a "report on anti-Semitism" requested by Mayr for one Adolf Gemlich, who participated in the same "educational courses" that Hitler had taken part in. In this report to his superior, Hitler argued for a "rational anti-Semitism" which would not resort to pogroms, but which would instead "legally fight and remove the privileges enjoyed by the Jews as opposed to other foreigners living among us. Its final goal, however, must be the irrevocable removal of the Jews themselves." Certainly everyone at the time understood this as a call for forced expulsion, whether Hitler himself understood it that way is less clear given the genocide which Hitler ordered 22 years later.

Hitler would not be discharged from the army until 1920; after this he began to take full part in the party's activities. He soon became its leader and changed its name to the National Socialist German Workers Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei - NSDAP), usually known as the Nazi party from National Sozialistische, in contrast to Sozi, a term used for the Social Democrats. The party adopted the swastika (supposedly a symbol of "Aryanism") and the Roman salute, also used by the Italian fascists.

The Nazi party was but one of a large number of small extremist groups in Munich at this time. But Hitler soon discovered that he had two remarkable talents—for public oratory and for inspiring personal loyalty. His street-corner oratory, attacking the Jews, the socialists and liberals, the capitalists and Communists, began to attract adherents. Early followers included Rudolf Hess, Hermann Göring, and Ernst Röhm, head of the Nazis' paramilitary organization, the SA. Another admirer was the wartime Field-Marshall Erich Ludendorff. Hitler decided to use Ludendorff as a front in an attempt to seize power in Munich, the capital of Bavaria, later known as the "Beer Hall Putsch" of November 8 1923, when the Nazis marched from a beerhall to the Bavarian War Ministry, intending to overthrow Bavaria's right-wing separatist government and then march on Berlin. They were quickly dispersed by the army and Hitler was arrested. Fearing some of the "left-wing" members of the Nazi party might try to sieze the leadership from him during incarceration, Hitler quickly appointed Alfred Rosenberg temporary leader.

Hitler was put on trial for high treason, and used his trial as an opportunity to spread his message throughout Germany. In April 1924 he was sentenced to five years' imprisonment in Landsberg Prison. Here he dictated a book called Mein Kampf (My Struggle) to his faithful deputy Hess. The book was written during 1923 and 1924 at Hitler's prison and later at an inn. Reading Mein Kampf is like listening to Hitler speak at length about his youth, early days in the Nazi Party, future plans for Germany, and ideas on politics and race. The original title Hitler chose was “Four and a Half Years of Struggle against Lies, Stupidity and Cowardice.” His Nazi publisher knew better and shortened it to Mein Kampf, simply My Struggle, or My Battle.

In his writing, Hitler announced his hatred toward what he believed to be the twin evils of the world: Communism and Judaism, and he stated that his aim was to eradicate both from the face of the earth. He announced that Germany needed to obtain new soil called lebensraum which would properly nurture the "historic destiny" of the German people; this goal explains why Hitler invaded Europe, both East and West, before he launched his attack against Russia. Hitler presented himself as the "Übermensch", or "Superman", that Friedrich Nietzsche had referred to in his writings, especially in his book, 'Thus Spoke Zarathustra'. Since Hitler blamed the current parliamentary government for much of the ills against which he raged, he announced that he would completely destroy that type of government. It is in Mein Kampf that the true nature of Hitler's character can be discovered. He divides humans up based on physical attributes. Hitler claims that German "Aryans" with blond hair and blue eyes were at the top of the hierarchy, and assigns the bottom of the order to Jews, Poles, Russians, Czechs and Gypsies. Hitler goes on to say that dominated peoples benefit by learning from the superior Aryans. Hitler further claims that the Jews are conspiring to keep this master race from rightfully ruling the world, by diluting its racial and cultural purity and by convincing the Aryan to believe in equality rather than superiority and inferiority. He describes the struggle for world domination as an ongoing racial, cultural, and political battle between Aryans and Jews. The supposed struggle for world domination between Aryans and Jews was accepted by the population when Hitler eventually came to power. He could not have succeeded for so long if the population of Germany had not had a tradition of anti-semitism.

Considered relatively harmless, Hitler was given an early amnesty. He was released in December 1924. By this time the Nazi party barely existed and Hitler would have a long effort in trying to rebuild it. During these years he established a group which later became one of his key instruments in carrying out his objectives. As Röhm's Sturmabteilung ("Stormtroopers" or SA), were unreliable and formed a separate base of power within the party, Hitler established a personal bodyguard, the Schutzstaffel ("Protection Unit" or SS). This elite black-uniformed corps was to be commanded by Heinrich Himmler, who was to become the principal executor of his plans with respect to the "Jewish Question" during the Second World War.

A key element of Hitler's appeal was the sense of offended national pride caused by the Treaty of Versailles imposed on the defeated German Empire by the Allies. The German Empire lost territory to France, Poland, Belgium and Denmark, and had to admit sole responsibility for the war, give up her colonies and her Navy, and pay a huge reparations bill, totaling $6,600,000 (32 billion marks). Since most Germans did not believe that the German Empire had started the war, and did not believe until later that they had been defeated, they bitterly resented these terms. Although the party's early attempts to garner votes by blaming all these humiliations on the machinations of "international Jewry" were not particularly successful with the electorate, the party's propaganda wing learned quickly, and soon a more subtle propaganda - which combined anti-semitism with a spirited attack on the failures of the "Weimar system" and the parties which had supported it - began to come to the fore.

The road to power

The turning point in Hitler's fortunes came with the Depression which hit Germany in 1930. The democratic regime established in Germany in 1919, the so-called Weimar Republic, had never been genuinely accepted by conservatives and was openly opposed by fascists.

The Social Democrats and the traditional parties of the center and right were unable to deal with the shock of the Depression, and were, moreover, all tainted with association with the Weimar system, and in the elections of September 1930 the Nazis suddenly rose from obscurity to win more than 18% of the vote and 107 seats in the Reichstag, becoming the second largest party. Their rise to power was aided by the influential right-wing media empire controlled by Alfred Hugenberg.

Hitler won over the bulk of the German middle-class, who had been hard hit by the inflation of the 1920s and the unemployment of the Depression. Farmers and war veterans were other groups who supported the Nazis. The urban working classes generally ignored Hitler's appeals, and Berlin and the Ruhr towns were particularly hostile.

The 1930 election was a disaster for Heinrich Brüning's center-right government, which was now deprived of any chance at a Reichstag majority, and had to rely on the toleration of the Social Democrats and the use of presidential emergency powers to remain in power. With Brüning's austerity measures in the face of the Depression having little success, the government was anxious to avoid a presidential election in 1932, and hoped to secure the Nazis' agreement to an extension of President Paul von Hindenburg's term, but Hitler refused to agree, and ultimately competed against Hindenburg in the presidential election, coming in second in both the first and second rounds of the election, and attaining more than 35% of the vote in the second round, in April, despite the attempts of both Interior Minister Wilhelm Gröner and the Social Democratic Prussian government to restrict the Nazis' public activities, notably including a ban on the SA.

The embarrassments of the election put an end to Hindenburg's tolerance for Brüning, and the old Field Marshal dismissed the government, appointing a new government under the reactionary non-entity Franz von Papen, which immediately repealed the ban on the SA and called for new Reichstag elections. In the July 1932 elections the Nazis had their best showing yet, winning 230 seats and becoming the largest party. Since now the Nazis and Communists together controlled a majority of the Reichstag, the formation of a stable government of mainstream parties was impossible, and, following a vote of no-confidence in the Papen government supported by 84% of the delegates, the new Reichstag was immediately dissolved and new elections called.

Papen and the Centre Party now both opened negotiations to secure Nazi participation in the government, but Hitler set high terms, demanding the Chancellorship and the President's agreement that he be able to use emergency powers under Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution. This failure to join the government, along with the Nazis' efforts to win working class support, alienated some of the Nazis' previous supporters, so that in the elections of November 1932, the Nazis actually lost votes, although they remained by far the largest party in the Reichstag.

As Papen had clearly failed in his attempts to secure a majority through negotiation to bring the Nazis into the government, Hindenburg dismissed him and appointed in his place General Kurt von Schleicher, long a power behind the scenes and more recently Defense Minister, who promised that he could secure a majority government by negotiations with both Social Democratic labour unions and with the dissident Nazi faction led by Gregor Strasser.

As Schleicher attempted this difficult mission, Papen and Alfred Hugenberg, who was also Chairman of the German National People's Party (DNVP), before the Nazis' rise Germany's principal right-wing party, now conspired to persuade Hindenburg to appoint Hitler Chancellor in a coalition with the DNVP, promising that they would be able to control him. When Schleicher was forced to admit failure in his efforts, and asked Hindenburg for yet another Reichstag dissolution, Hindenburg fired him and put Papen's plan into execution, appointing Hitler Chancellor with Papen as Vice-Chancellor and Hugenberg as Minister of Economics, in a cabinet which only included three Nazis—Hitler, Göring, and Wilhelm Frick. On January 30, 1933, Adolf Hitler was officially sworn in as Chancellor in the Reichstag chamber, with thousands of Nazi supporters looking on and cheering.

But Hitler did not yet hold the nation in thrall. Hitler's initial election into office and his use of constitutionally enshrined mechanisms to shore up power have led to the myth that his country elected him dictator and that a majority supported his ascent. He was made Chancellor in a legal appointment by President Hindenburg. This was a bit of historical irony, as the mainstream parties had supported Hindenburg as the only viable alternative to Hitler, not realizing that it would be Hindenburg who would bring about the end of the republic.

But neither Hitler himself nor the party he headed garnered a majority vote. In the last free elections, the Nazis polled 33% of the vote, winning 196 seats out of 584. Even in the elections of March 1933, which took place after terror and violence had suffused the state, the Nazis received only 44% of the vote. The party gained control of a majority of seats in the Reichstag through a formal coalition with the DNVP. Finally, the additional votes needed to pass the Enabling Act, which invested Hitler with dictatorial authority, were secured by the Nazis by expelling the Communist deputies and intimidating Centre Party ministers. In a series of decrees that followed soon afterwards, other parties were suppressed and all opposition was banned. In only a few months Hitler had achieved authoritarian control and buried the last vestiges of democracy.

The Nazi regime

Having secured supreme political power without winning support from the majority of Germans, Hitler in fact did go on to win it, and he remained overwhelmingly popular until the very end of his regime. He was a master orator, and with all of Germany's mass media under the control of his propaganda chief, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, he was able to persuade most Germans that he was their saviour—from the Depression, the Communists, the Versailles Treaty and the Jews. For those who were not persuaded, the SA, the SS and the Gestapo (Secret State Police) were given a free hand, and thousands disappeared into concentration camps. Many thousands more emigrated, including about half of Germany's Jews.

By this time, Ernst Röhm's SA have become unpopular with most of the other arms os political and military influence in Germany. Hitler unleashed his lieutenant Himmler to murder Röhm and dozens of other real and potential enemies during the night of June 29-June 30, 1934. The event is remembered as the Night of the Long Knives. When Hindenburg died on August 2 1934 Hitler merged the offices of President and Chancellor, appointing himself Leader (Führer) of Germany, and extracting an oath of personal loyalty from every member of the armed forces. This merger, which had been approved by the Weimar parliament only hours before the death of Hindenburg, was later validated by a majority of 89.9% of the electorate in a vote by plebiscite on August 19 1934.

Those Jews who had not emigrated in time soon regretted their hesitation. Under the 1935 Nuremberg Laws they lost their status as German citizens and were expelled from government employment, the professions and most forms of economic activity. They were subject to a barrage of hateful propaganda. Few non-Jewish Germans objected to these steps. The Christian Churches, steeped in centuries of anti-Semitism, remained silent. These restrictions were further tightened later, particularly after the 1938 anti-Jewish operation known as Kristallnacht. From 1941 Jews were required to wear a yellow star in public. Between November 1938 and September 1939, more than 180,000 Jews fled Germany; the Nazis seized whatever property they left behind.

The Nazi party oversaw one of the greatest expansions of industrial production and civil improvement that Germany had ever seen. The German economy under Hitler achieved near full employment and greatly expanded its economic and industrial base. Hitler also oversaw one of the largest infrastructure improvement campaigns in German history, with the construction of dozens of dams, highway, railroads, and other civil improvements. In striking contrast to the condition of Jews in Germany, Hitler's health initiatives for ethnic Germans were successful and progressive. For these and other reasons, Hitler was very popular among the German people during this time.

In March 1935 Hitler repudiated the Treaty of Versailles by reintroducing conscription in Germany. His set goal was building of a massive military machine, including a new Navy and an Air Force (the Luftwaffe). The latter was set under the command of Göring, a veteran commander of World War I. The enlistment of vast numbers of men and women in the new military seemed to solve unemployment problems, but seriously distorted its economy.

In March 1936 he again violated the Treaty of Versailles by reoccupying the demilitarised zone in the Rhineland. When Britain and France did nothing to stop him, he grew bolder. In July 1936 the Spanish Civil War began when the military, led by General Francisco Franco, rebelled against the elected Popular Front government of Spain. Hitler sent troops to help the rebels. Spain served as a testing ground for Germany's new armed forces and their methods, including the bombing of undefended towns such as Guernica, which was destroyed by the Luftwaffe in April 1937.

Hitler formed an alliance with the Italian fascist dictator Benito Mussolini on October 25, 1936. This alliance was later expanded to include Japan, Hungary, Romania and Bulgaria. They are collectively known as the Axis Powers. Then on November 5, 1937 at the Reich Chancellery, Adolf Hitler held a secret meeting and stated his plans for acquiring "living space" for the German people.

On March 12, 1938, Hitler pressured his native Austria into unification with Germany (the Anschluss) and made a triumphal entry into Vienna. Next he intensified a crisis over the German-speaking Sudetenland district of Czechoslovakia. This led to the Munich Agreement of September 1938 where Britain and France weakly gave way to his demands, averting war but failing to save Czechoslovakia.

As a result of the Munich summit, Hitler was Time Magazine's Man of the Year in 1938. It has also been alleged that Jewish author Gertrude Stein campaigned forcefully for Hitler to receive the Nobel Peace Prize that year.

Hitler ordered Germany's army to enter Prague on March 10 1939.

At this point Britain and France decided to make a stand, and they resisted Hitler's next demands, for the return of the territories ceded to Poland under the Versailles Treaty. But the western powers were unable to come to an agreement with the Soviet Union for an alliance against Germany, and Hitler outmaneuvered them. On August 23 1939 he concluded an alliance (the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact) with Stalin. On September 1 Germany invaded Poland. Hitler was surprised when Britain and France honoured their pledge to the Poles by declaring war on Germany.

World War II: victories

Over the next three years Hitler had an almost unbroken run of military success. Poland was quickly defeated and partitioned with the Soviets. In April 1940 Germany invaded Denmark and Norway. In May Germany initiated a lightning offensive, known as Blitzkrieg, that quickly overran The Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg and France, which collapsed within six weeks. In April 1941 Yugoslavia and Greece were invaded. Meanwhile German forces were advancing across North Africa towards Egypt. These invasions were accompanied by the bombing of undefended cities such as Warsaw, Rotterdam and Belgrade. Hitler's only setback was the failure of his attempt to bomb Britain into submission, which was thwarted during the Battle of Britain. The inability to achieve air superiority meant that Operation Sealion, the plan to invade Britain, was cancelled.

On June 22 1941 Operation Barbarossa began. Hitler's forces invaded the Soviet Union, rapidly seizing the western third of European Russia, besieging Leningrad and threatening Moscow. In the winter Hitler's army was repelled from the gates of Moscow, but the following summer the offensive was resumed. By July 1942 Hitler's armies were on the Volga. Here they were defeated at the Battle of Stalingrad, the first major defeat Germany suffered in the war. In North Africa, Britain defeated Germany at the battle of El Alamein, thwarting Hitler's plans of seizing the Suez Canal and the Middle East.

The Holocaust

Main article: Holocaust.

The Holocaust refers to the Nazis' systematic extermination of "undesirables" in concentration camps. Jews were primarily targeted, though many others were murdered in the camps, as well: communists, homosexuals, gypsies, the physically handicapped, the mentally retarded, Soviet prisoners of war, the Polish intelligentsia, Jehovah's Witnesses, anti-Nazi clergy and trade unionists, psychiatric patients, and even common criminals all perished alongside one another in the camps.

Adolf Hitler's fanatical anti-Semitism was laid out in his 1925 book Mein Kampf - largely ignored when it was first printed, it became popular after Hitler's rise to power. When Germany occupied Europe, in many places Jews were resettled into concentrated areas, ghettos. It is believed that mass murder of the Jews began with the Einsatzgruppen who followed the Wehrmacht into the Soviet Union, conducting mass shootings of Jews throughout the recently occupied territories which have been estimated to have killed approximately 2 million Jews. However there remained a question of millions of Jews in the European ghettoes, especially within the General Government of Poland.

While no specific order from Hitler authorizing the mass killing of the Jews has surfaced, the evidence suggests that sometime in the fall of 1941, Himmler and he agreed in principle on mass murder by gassing. To make for smoother intra-governmental cooperation in the implementation of this "Final Solution," to the "Jewish Question," the Wannsee conference was held near Berlin on January 20 1942 with the participation of fifteen senior officials, led by Reinhard Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann, the records of which provide the best evidence of the central planning of the Holocaust. Between 1942 and 1944 the SS, assisted by collaborationist governments and recruits from occupied countries, systematically killed approximately 3.5 million more Jews in six camps in Poland (Auschwitz-Birkenau, Belzec, Chelmno, Majdanek, Sobibor and Treblinka) and one in present-day Belarus (Maly Trostenets). Others were killed less systematically elsewhere, or died of starvation and disease while working as slave laborers. This attempt to exterminate the Jews of Europe is now generally called the Holocaust, although the Hebrew word Shoah is preferred by some Jewish writers.

Other ethnic groups and social categories were also subject to persecution and in some cases extermination. Thousands of German socialists, communists and other opponents of the regime died in concentration camps, as did a large but unknown number of homosexual men. The Gypsies were regarded as an inferior race and were also shot or sent to death camps. About three million Soviet prisoners of war also died in camps or as slave labourers. All the occupied countries suffered terrible privations and mass executions: up to three million (non-Jewish) Polish civilians died during the occupation.

There is no known document in which he explicitly ordered the Holocaust, although there is documentation that he approved of the Einsatzgrupen, where Jews throughout Russia were shot naked in front of ditches. Most historians believe he not only knew of the Holocaust and the gas chambers but ordered Himmler to carry it out—certainly it was entirely consistent with his lifelong beliefs.

World War II: defeat

Hitler's early military triumphs persuaded him (and many others) that he was a strategic genius, and he became increasingly unwilling to listen to advice or to hear bad news. After the battle of Stalingrad, widely regarded as the turning point of WW II, his military decisions became increasingly erratic, and Germany's military and economic position deteriorated. His declaration of war against the United States on December 11 1941 (which arguably was called for by treaty with Japan) set him against an awesome coalition of the world's largest empire (the British Empire), the world's greatest industrial and financial power (the USA), and the world's largest nation, the Soviet Union, which shouldered the largest burden of WW II in terms of human and other losses. Realists in the German army saw that defeat was inevitable, and some officers plotted to remove Hitler from power. In July 1944 one of them, Claus von Stauffenberg set up a bomb at Hitler's military headquarters (the so-called July 20 Plot), but Hitler narrowly escaped death. Savage reprisals followed and the resistance movement was crushed.

Hitler's ally Benito Mussolini was overthrown in 1943. Meanwhile the Soviet Union was steadily forcing Hitler's armies to retreat from their conquests in the East. But as long as western Europe was secure, Germany could hope to hold the line indefinitely, despite an increasingly heavy campaign of bombing of German cities. On June 6 1944 (D-Day), Allied armies landed in northern France, and by December they were on the Rhine. Hitler staged a last ditch offensive in the Ardennes (the Battle of the Bulge). But by the new year the western armies were advancing into Germany. At this time the Germans had lost the war from a military perspective but Hitler allowed no peace talks with the Allied forces and as a consequence the German military continued to fight till the bitter end.

In February the Soviets smashed their way through Poland and eastern Germany, and in April they arrived at the gates of Berlin. Hitler's closest lieutenants urged him to flee to Bavaria or Austria to make a last stand in the mountains, but he was determined to die in his capital. Convinced that if Germany couldn't win the war that it should not exist, Hitler, on March 19, 1945, ordered that all industries, military installations, shops, transportation facilities and communications facilities in Germany be destroyed (see Nero Decree). His armies crumbling, and with Soviet forces fighting their way into central Berlin, Hitler killed himself in his Berlin bunker on 30 April 1945. He shot himself in the head, and may have simultaneously bitten a tablet of prussic acid. He was 56. His longtime mistress, Eva Braun, also killed herself. As part of his last will, he ordered that his body be taken outside and burned along with Eva Braun's. In the testament he left, he dismissed the other Nazi leaders and appointed Admiral Karl Dönitz as the new Führer and Goebbels as the new Chancellor of Germany. However the latter committed suicide on May 1, 1945. On May 8 1945, Germany surrendered. Hitler's "Thousand Year Reich" had lasted a little over 12 years.

Hitler's personal life

The death of Geli Raubal could be seen to shed light on Hitler's personal life. In 1929, Hitler took in his half-sister Angela and her daughter Geli Raubal, to live in his Munich apartment. He is said by some to have fallen in romantic love with Geli despite the fact she was much younger than he was, and also his niece. In December 1931, Geli was found dead in her bedroom, shot by a bullet from one of his handguns. The police ruled her death a suicide. This tragedy disturbed Hitler immensely. Biographer Joachim C. Fest states that "...and unless all the indications are deceptive, no other event in his personal life affected him as strongly as did this one. For weeks he seemed close to a nervous breakdown and repeatedly swore to give up politics. In his fits of gloom he spoke of suicide...".

During his time in power, his partner was Eva Braun. They married just before both committed suicide.

In the 1940s his left hand started shaking which he found difficult to control. The biographer Ian Kershaw believes he suffered from Parkinson's disease.

Various claims have been speculated regarding Hitler's abnormal sexual practices. Kershaw dismisses theories about Hitler's alleged unusual sexual practices as untrue and writes that they are based on mere rumors and made-up "testimonies".

Some historians have written about Hitler's sexual orientation. For example, German historian Lothar Machtan argues in his book, The Hidden Hitler, published in 2001, that Hitler was secretly gay. The book claims to have material previously unconsidered by historians that supports the controversial thesis. Other historians have rejected this thesis as highly speculative and unsupported by hard evidence.

The consequences of Hitler and Nazi Germany

See: Consequences of German Nazism

Hitler in Popular Culture

Since the defeat of Germany in World War II, and as a result of his adamant and unforgiving racialism and anti-Semitism, Hitler has often been portrayed as being synonymous with evil, hatred and bigotry at their most destructive degree.

Elie Wiesel, a Jewish Holocaust survivor, called him in a Time Magazine column an "avatar of fascism", a "Satan", and an "exterminating angel" who "redefined the meaning of evil forever".

The display of the swastika and other symbols like the SS runes is currently banned in Germany and several other European nations, and the surname "Hitler" has fallen into disuse worldwide. The sale of the book Mein Kampf is, contrary to wide belief, not banned by law (at least not in Germany), but the copyright of the work is owned by the German state of Bavaria which doesn't grant the rights for publication.

Numerous works in popular music and literature feature him prominently. Before and during World War II, Hitler was often depicted outside of Germany as incompetent or foolish and treated as an object of derision. Later works continued the trend. Examples include Charlie Chaplin's 1940 film The Great Dictator and Donald Duck in Nutziland, a 1943 Disney wartime propaganda cartoon. The cartoon was retitled Der Fuehrer's Face after Spike Jones had a hit with the song of that name from the short. Other examples are painter Salvador Dali's painting Hitler Masturbating, the popular lyrics for the Colonel Bogey March (Hitler has only got one ball) or the well-known German satirical comic book series Adolf by Walter Moers. Mel Brooks' comedy The Producers featured a play-within-a-play called Springtime for Hitler.

Comparing political opponents to Hitler is also a very common tactic in many countries. During the United States presidential campaign of 2004, controversy arose over the use of images of Hitler in two (out of 1500) ads submitted to a contest run by the MoveOn.org Voter Fund, which disavowed the ads. More controversy arose when the George W. Bush website used clips from one of the ads to illustrate what the Bush campaign referred to as John Kerry's "Coalition of the Wild-eyed".

Mel Brooks' comedy, The Producers featured a play-within-a-play called Springtime for Hitler.

Hitler's Cabinet, January 1933 - April 1945

- Adolf Hitler (NSDAP) - Chancellor

- Franz von Papen - Vice Chancellor

- Konstantin Freiherr von Neurath - Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Wilhelm Frick (NSDAP) - Minister of the Interior

- Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk - Minister of Finance

- Alfred Hugenberg (DNVP) - Minister of Economics and Food

- Franz Seldte - Minister of Labour

- Franz Gürtner (DNVP) - Minister of Justice

- Werner von Blomberg - Minister of Defense

- Paul Freiherr Eltz von Rübenach - Minister of Posts and Transport

- Hermann Göring (NSDAP) - Minister without Portfolio

Changes

- March 1933: Joseph Goebbels enters the cabinet as Minister of Propaganda.

- April 1933: Göring takes a portfolio as Minister of Aviation.

- June 1933: Kurt Schmitt succeeds Hugenberg as Minister of Economics. Walter Darré succeeds Hugenberg as Minister of Food.

- December 1933: Ernst Röhm and Rudolf Hess enter the Cabinet as Ministers without Portfolio.

- May 1934: Bernhard Rust enters the Cabinet as Minister of Science and Education.

- June 1934: Hanns Kerrl enters the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio. Röhm, Minister without Portfolio, is murdered.

- July 1934: Göring takes another portfolio as Minister of Forestry.

- August 1934: Franz von Papen resigns as Vice-Chancellor. He is not replaced. Hjalmar Schacht succeeds Schmitt as Minister of Economics.

- December 1934: Hans Frank enters the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio.

- March 1935: Göring takes yet another portfolio as Commander-in-Chief of the Luftwaffe.

- May 1935: The title of Minister of Defense is replaced by that of Minister of War. Blomberg retains the office.

- July 1935: Hanns Kerrl takes a portfolio as Minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs.

- April 1936: Werner von Fritsch enters the Cabinet as Commander-in-Chief of the Army. Erich Raeder enters the cabinet as Commander in Chief of the Navy.

- February 1937: Wilhelm Ohnesorge succeeds Eltz as Minister of Posts. Julius Dorpmüller succeeds Eltz as Minister of Transport.

- November 1937: Hermann Göring succeeds Schacht as Minister of Economics. Schact becomes Minister without Portfolio

- December 1937: Otto Meissner enters the Cabinet as Minister of State and Head of the Chancellery.

- January 1938: Walter Funk succeeds Göring as Minister of Economics.

- February 1938: Joachim von Ribbentrop replaces Neurath as Minister of Foreign Affairs. Neurath becomes Minister without Portfolio. Blomberg resigns as Minister of War and his office is abolished. His role is taken by General Wilhelm Keitel as Director of the OKW. Walther von Brauchitsch succeeds Fritsch as Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

- May 1939: Arthur Seyss-Inquart enters the Cabinet as Minister without Portfolio.

- March 1940: Fritz Todt becomes Minister of armament and amunition.

- January 1941: Franz Schlegelberger succeeds Gürtner as Minister of Justice.

- May 1941: Rudolf Hess is suspended from the Cabinet.

- December 1941: Hanns Kerrl, the Minister of Ecclesiastical Affairs, dies. He is not replaced. Hitler himself takes up the position of Commander-in-Chief of the Army.

- February 1942: Albert Speer succeeds Todt as minister of armament and amunition.

- May 1942: Herbert Backe succeeds Darré as Minister of Food.

- August 1942: Otto Georg Thierack succeeds Schlegelberger as Minister of Justice.

- January 1943: Karl Dönitz succeeds Raeder as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.

- August 1943: Heinrich Himmler succeeds Frick as Minister of the Interior.

- July 1944: Schacht departs the Cabinet.

Hitler's family

- Eva Braun mistress and then wife

- Alois Hitler father

- Klara Hitler mother

- Paula Hitler sister

- William Patrick Hitler nephew

- Geli Raubal niece

Related articles

- Anti-semitism

- Cultural representations of Hitler

- Fascism

- History of Austria

- History of Germany

- Holocaust

- Homosexuals in Nazi Germany

- Jehovah's Witnesses and the Holocaust

- Nazi children

- Nazism

- Nazi Germany

- Nazi Party

- Report from Himmler to Hitler

- World War II

- Swastika

- Mein Kampf

- Rise of Hitler

References and further reading

- Doron Arazi, Adolf Hitler: A Bibliography, Greenwood, 1994, ISBN 0-877-36360-1

- Alan Bullock, Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives, HarperCollins, 1991, ISBN 0679729941

- Alan Bullock, Hitler: A Study in Tyranny, ISBN 0060920203

- Joachim Fest, Hitler, Harvest Books, 2002, ISBN 0156027542

- Ian Kershaw, Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, W W Norton, 1999, and Hitler 1937-1945: Nemesis, W W Norton, 2000, ISBN 0393320359

- Lothar Machtan, The Hidden Hitler (Basic Books, 2001, ISBN 0-465-04308-9; English translation by John Brownjohn)

External links

- Quotes by Hitler from Wikiquote

- Mondo Politico Library's presentation of Adolf Hitler's book, Mein Kampf (full text, formatted for easy on-screen reading)

- Extensive site on Adolf Hitler

- The Hitler Historical Museum

- Excerpt from book about Hitler's WWI military service

- All early images of Adolf Hitler up to 1925

| Preceded by: Paul von Hindenburg |

President of Germany 1934-1945 |

Succeeded by: Karl Dönitz |

| Preceded by: Kurt von Schleicher |

Chancellor of Germany 1933-1945 |

Succeeded by: Joseph Goebbels |

| Titles were combined 1934-1945 as Führer | ||