| This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. Please improve the article by adding information on neglected viewpoints, or discuss the issue on the talk page. (February 2021) |

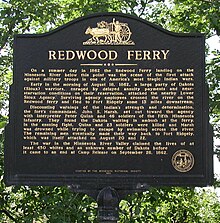

The Battle of Redwood Ferry took place on August 18, 1862, on the first day of the Dakota War of 1862. A United States Army company responding to the Dakota attack at the Lower Sioux Agency from Fort Ridgeley was ambushed and defeated at Redwood Ferry.

| Battle of Redwood Ferry | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of The Dakota War of 1862 | |||||||

Redwood Ferry near the Lower Sioux Agency | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Dakota (Santee Sioux) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

White Dog | Captain John S. Marsh† | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Unknown | Co B, 5th Minnesota Infantry, Fort Ridgely | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown (more than 47) | 47 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1 killed | 24 killed, 1 drowned, 5 wounded | ||||||

| |||||||

| Dakota War of 1862 | |

|---|---|

|

Prelude

Main article: Dakota War of 1862 Further information: Attack at the Lower Sioux AgencyAt 10 am on August 18, 1862, word of the attack at the Lower Sioux Agency reached Fort Ridgely. Captain John S. Marsh heard news of the killings from J.C. Dickinson, the agency boarding house manager, who had escaped with his family by ferry and had arrived at Fort Ridgely in a wagon. The news that Dakota warriors were attacking settlers and agency staff was soon confirmed by the arrival of more refugees bringing a wounded man.

Captain Marsh decided to go to the rescue at once. The long roll was sounded and the garrison was under arms. Marsh immediately sent Corporal James C. McLean with a message for Lieutenant Timothy Sheehan, who had left Fort Ridgely the day before with 50 men of Company C, 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment, en route to Fort Ripley. Captain Marsh's message urged Sheehan to return with his command immediately.

Within 30 minutes, Marsh left the agency with 46 enlisted men from Company B of the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment and interpreter Peter Quinn on a march toward the Lower Sioux Agency. Marsh and Quinn rode mules. The other men marched for three miles until they were overtaken by wagon teams that had departed Fort Ridgely after them, then boarded the wagons.

Meanwhile, 19-year-old Lieutenant Thomas P. Gere was left to hold the fort with only 22 soldiers available for active duty, as the rest were sick or on hospital detail. He was supported by Post Sutler Ben H. Randall, Ordnance Sergeant John Jones, and the surgeon, Dr. Alfred Müller, who helped Gere deal with the sudden influx of refugees at Fort Ridgely.

On the road, Captain Marsh and the soldiers encountered many settlers fleeing for their lives. One of the refugees was Reverend Samuel D. Hinman, who warned Marsh of the severity of the attacks and that he and his men would be outnumbered if they went all the way to Redwood Ferry.

Six miles from Fort Ridgely, Marsh and his men passed houses that were in flames, and saw numerous corpses of men, women and children "not yet cold" on the side of the road. Captain Marsh continued undeterred toward Redwood Ferry.

In Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, General Lucius Frederick Hubbard wrote: "Still in the hope that all this was the work of some desperate band of outlaws among the Sioux, and strangely confident that it was in his power to quell the disturbance, Capt. Marsh, again forming his command on foot, hurried on."

Battle

What exactly transpired in the vicinity of Redwood Ferry is unclear. The ensuing battle would leave Captain John S. Marsh drowned, 24 soldiers killed, including his interpreter, and five wounded.

About three miles from the Lower Sioux Agency, Marsh and his men reached Faribault Hill, and descended the road. About one mile from the ferry, they left their wagons behind and crossed a small stream. Halfway across, they paused to rest, then proceeded in single file toward the ferry house, which stood two hundred feet east of the ferry landing.

Near the landing, which was on the east bank of the Minnesota River, the grass was thick with heavy growth of hazel and willow brush on either side of the road. Dozens of Dakota warriors were hiding in the grass, waiting with guns ready.

Stopping at the ferry house shortly after 12 noon, they found the ferryboat conveniently moored there. Survivors of the ambush would later reflect that the Dakota were probably waiting for them to board the boat, where they would have been an easy target. The soldiers had found the corpse of the ferryman, headless and disemboweled, on the side of the road on their way to the landing.

Encounter with White Dog and ambush

Across the river, they saw White Dog (Śuŋkaska), who was known as a "cut hair" Dakota, standing on the bluff on the west bank. He had previously overseen the farmer Dakota at the Lower Sioux Agency, until he was replaced by Taopi. They also spotted a few Dakota women and children on the bluff. John Magner, a soldier in Marsh's command who knew White Dog well, later testified that White Dog had been holding a large tomahawk and was "all painted over red" on his face and head. The red paint generally signified a willingness to die in war.

Marsh began a conversation with White Dog through Quinn. Quinn asked White Dog why he seemed so "out of character," to which White Dog replied that he had brought the tomahawk "to smoke." He reassured Marsh and Quinn that he did not intend to fight and that there would be no trouble.

White Dog then invited Marsh to cross the river in the ferry for a council. White Dog himself would later confirm this much at his trial after the war.

Some sources later accused White Dog of deliberately prolonging his exchange with Marsh to allow the other Dakota to ford the river upstream, take cover in the thicket, and take control of the ferry house. Magner reported that Marsh had instructed him to look upriver for movements, when he saw in the river and in the weeds to the north that "the place was red with their heads." Marsh then ordered his men to retreat at roughly 1:30 PM.

White Dog then appeared to give the signal for the Dakota warriors to shoot, killing Quinn and twelve soldiers, and wounding many more.

Controversy over White Dog's role

After the war and prior to his execution, White Dog stated to Reverend Stephen Return Riggs that after inviting Marsh to cross the river, he spotted the warriors lying in wait for an ambush, and gestured to Marsh to stay back. White Dog also denied telling the Dakota warriors to fire. He complained bitterly that he did not have a chance to tell the whole story, and that he and others had not had fair trials. However, most sources seem to contradict White Dog's version of events.

Exchange of fire and escape

Captain Marsh was unhurt and ordered his men to fall back to the ferryhouse, only for the Dakota warriors who had taken over the ferryhouse unnoticed behind him to open fire in the right rear. The captain ordered an about face. His men closed ranks, advanced, and fired a volley, but it was mostly in vain, as more of them fell. On Marsh's command, the surviving men broke for cover in the thicket extending downstream for two miles. The Dakota warriors skirted the thicket from a distance, too far for their shots to reach Marsh and his men. Finally, as the timber and underbrush thinned, Marsh decided to cross the stream to avoid further fire, and attempt to find their way back to the fort on the south bank. A confident swimmer, Marsh entered the water first, but suffered a cramp and drowned, despite the efforts of two of his men to save him.

Nineteen-year-old Sergeant John F. Bishop then led fifteen survivors, including five wounded men, back to Fort Ridgely. They reached the fort after nightfall. Eight other infantrymen arrived at the fort separately, including the severely-wounded William Blodgett and William Sutherland, who would only reach the relative safety of the fort on August 20 after two days' travel alone through hostile wilderness.

Aftermath

The surviving members of Company B made their way back towards Fort Ridgely. As it was getting dark, Lt. Bishop sent Privates James Dunn and William B. Hutchinson to Ridgely to tell the post commander what happened. They arrived at Ridgely at 2200 hours. The remaining men returned to the fort on August 20.

The defeat of Marsh and B Company, combined with Sheehan's departure, had left Fort Ridgely exceedingly lightly defended, with only 30-odd soldiers to guard the 300 or more civilian refugees sheltering there. The fort possessed no stockade, trenches, or other fortifications. Little Crow held a war council outside Fort Ridgely but chose to attack New Ulm on August 19 instead, which gave time for reinforcements to reach Fort Ridgely. Oscar Wall ascribes this miscalculation to dissension among the Dakota and their mistaken belief that the fort held more than 100 trained soldiers, not the 30 that remained after the departures of Sheehan and the Renville Rangers and Marsh's defeat. Corporal McLean was able to relay Marsh's message to Lt. Sheehan to return to Fort Ridgely, who with C Company returned in time to reinforce the beleaguered outpost before the Battle of Fort Ridgely began on August 20.

Notes

- In 1898, George Quinn (Wakonkdayamanne) told historian Return Ira Holcombe that all the Indians he had spoken to said that White Dog had told Captain Marsh to stay back, but that he himself was unsure what to believe. (Quinn and Carley (ed.), "As Red Men Viewed It")

References

- ^ Carley, Kenneth (1976). The Dakota War of 1862: Minnesota's Other Civil War. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. pp. 15–16, 26. ISBN 978-0-87351-392-0.

- ^ "Narrative of the Fifth Regiment". Minnesota in the Civil and Indian Wars, 1861-1865. St. Paul: Printed for the state by the Pioneer Press Co. 1890–93.

- Clodfelter, Micheal (1998). The Dakota War: the United States Army versus the Sioux, 1862-1865. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 41. ISBN 0-7864-0419-1.

- "Redwood Ferry Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. p. 49

- ^ Anderson, Gary Clayton (2019). Massacre in Minnesota: The Dakota War of 1862, the Most Violent Ethnic Conflict in American History. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 98, 303. ISBN 978-0-8061-6434-2.

- Quinn, George (1898). Carley, Kenneth (ed.). "As Red Men Viewed It: Three Indian Accounts of the Uprising". Minnesota History. 38 (3) (published September 1962): 126–149. JSTOR 20176459.

- ^ Folwell, William Watts (1921). A History of Minnesota. Vol. 2. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press. p. 113.

- Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. p. 69

- Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. p. 50

- Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. p. 51

- "Surprise Attack at Redwood Ferry Historical Marker". www.hmdb.org. Retrieved 2023-05-10.

- ^ Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. pp. 55–63.

- ^ Wall, Oscar Garrett (1908). Recollections of the Sioux Massacre. Lake City, Minnesota: The Home Printery. p. 79